Abstract

Background:

There is a paucity of data on smokeless tobacco (SLT) use in Bhavnagar city of western India. This research attempts to find out the dependence and willingness to quit SLT use.

Materials and Methods:

This was a hospital-based cross-sectional study conducted in a tertiary care government hospital on a calculated sample size of 258 SLT users in the year 2017. The patients were recruited from ear-nose-throat (ENT) and dental outpatient department (OPD). The tobacco dependence was assessed using “Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence-SLT” and willingness to quit was assessed on a Likert scale of 1–10.

Results:

Among the 258 SLT users, 20% were highly dependent on SLT and 61% had low willingness to quit tobacco. “Mawa” was the most common (60%) chewed form of tobacco. Illiterate patients were three times more likely and patients whose occupation required traveling were 2.4 times more likely to develop high dependence for SLT than their counterparts. Patients living in the joint family were 2.7 times more likely to develop high dependence than patients living in a nuclear family.

Conclusion:

There is a need for the introduction of tobacco cessation interventions in ENT and dental OPD of tertiary care hospitals of western India.

Key words: Health facilities, India, public facilities, smokeless tobacco, smokeless tobacco cessation, smokeless tobacco dependence, tobacco use disorder

INTRODUCTION

According to WHO estimates, about 194 million men and 45 million women use tobacco in the smoked or smokeless form in India; several studies show a great deal of variation by region, social customs, gender, and form of tobacco consumption.[1] Tobacco use is a major preventable cause of premature death and disease, currently leading to over five million deaths each year worldwide which is expected to rise to over eight million deaths yearly by 2030.[1] The vast majority of these deaths are projected to occur in developing countries. Nearly 8–9 lakh people die every year in India due to diseases related to tobacco use.[2] Majority of the cardiovascular diseases, cancers, and chronic lung diseases are directly attributable to tobacco consumption. In a nationally representative study, it has been estimated that in 2010, smoking will cause about 930,000 adult deaths in India; and about 70% of them will be between the age 30 and 69 years.[3] Indians were by far the most likely to report chewing tobacco.[4] The term “smokeless tobacco” (SLT) is used to describe tobacco that is consumed in unburnt form, which can be used nasally or orally (by dipping or chewing).[4]

Previously, there were a number of reviews and studies conducted on various aspects of SLT. There are published studies available on the dependence of SLT from Andaman Nicobar islands, Bangalore, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Bihar.[5,6,7,8] A few districts of western India have a high prevalence of SLT chewing. There are few studies from western India exploring the dependence of SLT and the willingness to quit among tobacco chewers. The present study attempts to assess the level of dependence and willingness to quit SLT among patients in a tertiary care hospital in a district of western India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and setting

It was a hospital-based cross-sectional study conducted in Sir Takhtsinhji Hospital, the tertiary care hospital of Bhavnagar district of western India. This hospital is the district government hospital catering to a population of around one lakh. It is a 750-bedded hospital with a government medical college attached to it.

Study duration

The study was carried out for a period of 4 months from June to September 2017. Statistical analysis and manuscript preparation was done in October 2017.

Sample size

A sample size of 258 was calculated using Epi Info software version 7 (Centre for Disease Control and Prevention CDC, Atlanta, USA),[9] considering the prevalence of SLT consumption in Gujarat as 21.6%,[10] absolute precision as 5%, and confidence limits as 95%.

Inclusion criteria

Patients above 18 years of age, who are consuming tobacco currently or in past were included in the study. Current tobacco chewers were defined as those consuming SLT at least one packet per day for >0 days for past 6 months. Past tobacco chewers were defined as those who have stopped consuming SLT at least for the past 6 months. Patients attending ear-nose-throat (ENT) and dental outpatient department (OPD) of the hospital were assessed for tobacco dependence and their willingness to quit.

Sampling technique

As the total sample size was 258 and the data were to be collected over a period of 2 months, data from four patients were collected daily. Randomly selected two patients each from ENT and dental OPD were included in the study daily (a total of 129 patients from each OPD). Two patients were selected randomly by deciding two numbers from random number table from the list of patients registered in the daily OPD register.

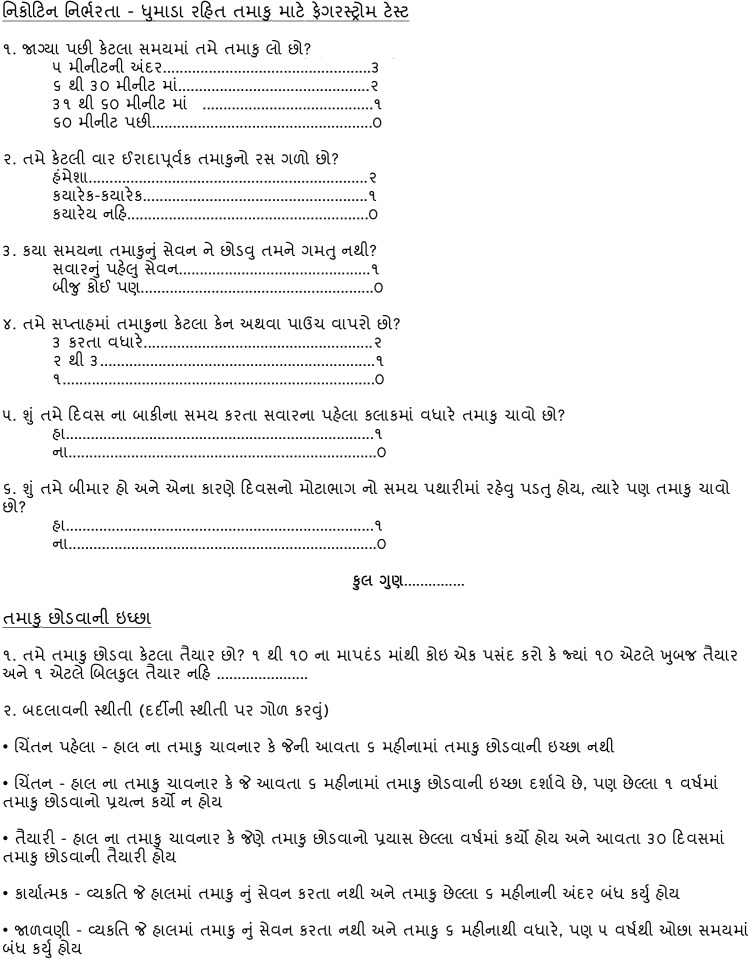

Data collection tool

Data were collected using a questionnaire prepared based on the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence-SLT (FTND-ST).[11] The FTND-ST is a 6-item questionnaire for assessing the dependence of oral tobacco use among the patients.[11] The scoring of FTND-ST was done by adding up the responses to all items. A score of 5 or more indicates a significant dependence, while a score of 4 or less shows a low to moderate dependence.[11] For the purpose of statistical analysis, the same scoring was followed with a score of ≥5 labeled as high dependence and a score of <5 as low dependence.

The questionnaire also included sociodemographic information and questions regarding the willingness to quit SLT consumption. The willingness to quit was assessed by asking their willingness to quit SLT on a Likert scale of 1–10, one signifying total unwillingness to quit and 10 signifying total willingness to quit. For the purpose of statistical analysis, a score of ≥5 was labeled as a high willingness to quit and a score of <5 was defined as a low willingness to quit.

The motivational phase of SLT cessation was assessed from the “stages of change” in which the patients were currently in.[12] These stages of change are based on the transtheoretical model describing cessation as an event occurring across motivational phases.[12] The stages of change included stage of precontemplation (current chewer not planning to quit within next 6 months), stage of contemplation (current chewer who has not made any quit attempts but planning to quit within next 6 months), stage of preparation (current chewer who had made quit attempts and planning to quit within next 30 days), stage of action (individual who has stopped chewing tobacco for the past 6 months), and stage of maintenance (individual who has stopped chewing tobacco for longer than 6 months). Such stages of change have been described in smoking cessation studies[13,14] as well as in SLT cessation studies.[5]

Pilot study

The final questionnaire was validated by two subject experts and was pretested on a small group of patients before applying to the study population (piloting). The piloting of the questionnaire revealed a few changes to be made to the questionnaire, and the second version of the questionnaire was then accepted for final data collection of the study. The data collected during the pilot study were not included in the final analysis or in the final sample size. The questionnaire was translated into the vernacular language [Gujarati - Annexure 1] and was backtranslated into English to check for fidelity. The backtranslation was found to be different than the original English version of the questionnaire, thereby three revisions were done on the translated questionnaire and the fourth version was finalized for the final data collection.

Outcome variables

The primary outcome variable was a dichotomous variable with FTND-ST score of ≥5 as high dependence and score of <5 as low dependence on SLT. The secondary outcome variable was also a dichotomous variable with a score of ≥5 on a 10-point Likert scale depicting high willingness to quit and score of <5 indicating low willingness to quit SLT.

Statistical methods used

Data were entered and analyzed in Epi Info software version 7 (Centre for Disease Control and Prevention CDC, Atlanta, USA).[9] Simple proportions were calculated. Student's t-test and Chi-square test were applied for univariate quantitative and qualitative data, respectively. The difference was said to be significant when P < 0.05.

Socioeconomic and occupation classification

For socioeconomic status, Modified Prasad's classification was used taking All India Consumer Price Index for Industrial Workers value of 270 for August 2017.[15,16]

Ethical issue

Written informed consent was taken from the individuals. The name of the respondents (tobacco chewers) was kept confidential and was not disclosed to anyone. The data pertaining to the name of the respondents were kept in a separate Microsoft Excel sheet accessible only to the investigators. Ethical approval was taken from the institutional ethics committee of Government Medical College Bhavnagar.

RESULTS

The mean age of the respondents was 41 (±11) years. The sociodemographic profile and SLT consumption pattern of the respondents is illustrated in Table 1. Out of the 258 SLT users, 30% were in the age group of 30–39 years; 95% were male; 51% having education up to primary level with 19% having education up to secondary level; 88% were currently married; and 90% belonged to Hindu religion. Out of 258 respondents, about two-thirds had a nuclear family; one-fourth had an occupation requiring travel; and about half of them belonged to Class IV socioeconomic status as per Modified Prasad's classification. Among the 258 respondents, the mean age of starting to use SLT was 24 years; mean number of years since chewing was 16 years; mean time tobacco was kept in mouth per consumption was 9 min; and mean packets of tobacco consumed per day was three. Mawa, a preparation of tobacco flakes mixed with areca nut and lime, was the most common (60%) chewed form of tobacco; followed by Vimal pan masala and Zarda (tobacco with lime, spices, vegetable dyes, and areca nut).[4] Most of the SLT users (69%) kept tobacco in buccal mucosa after preparation.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and tobacco consumption profile of smokeless tobacco users in a tertiary care hospital of western India (n=258)

| Variables | Descriptives |

|---|---|

| Age groups (years) | Frequency (%) |

| 20-29 | 34 (13.2) |

| 30-39 | 78 (30.2) |

| 40-49 | 72 (27.9) |

| 50-59 | 55 (21.3) |

| ≥60 | 19 (7.4) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Gender | Frequency (%) |

| Male | 244 (94.6) |

| Female | 14 (5.4) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Literacy status | Frequency (%) |

| Illiterate | 36 (14.0) |

| Just literate | 20 (7.8) |

| Primary | 131 (50.8) |

| Secondary | 49 (19.0) |

| Higher secondary | 14 (5.4) |

| Graduate | 8 (3.1) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Occupation status | Frequency (%) |

| Laborer | 89 (34.5) |

| Farmer | 39 (15.1) |

| Service | 19 (7.4) |

| Shopkeeper | 45 (17.4) |

| Unemployed/retired | 39 (15.1) |

| Driver | 10 (3.9) |

| Diamond worker | 17 (6.6) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Occupation require travel | Frequency (%) |

| Yes | 48 (18.6) |

| No | 210 (81.4) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Marital status | Frequency (%) |

| Married | 228 (88.4) |

| Unmarried | 24 (9.3) |

| Widower | 4 (1.6) |

| Separated | 2 (0.8) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Religion | Frequency (%) |

| Hindu | 233 (90.3) |

| Muslim | 25 (9.7) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Type of family | Frequency (%) |

| Nuclear | 170 (65.9) |

| Joint | 49 (19.0) |

| 3rd generation | 39 (15.1) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Socioeconomic status by modified Prasad’s classification | Frequency (%) |

| I | 4 (1.6) |

| II | 39 (15.1) |

| III | 114 (44.2) |

| IV | 75 (29.1) |

| V | 26 (10.1) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Forms of tobacco consumed | Frequency (%) |

| Mawa (areca nut+tobacco flakes + slaked lime) | 155 (60) |

| Vimal pan masala | 55 (21) |

| Zarda (tobacco + lime + spices + vegetable dyes+areca nut) | 25 (10) |

| Khaini (Miraj) | 19 (7) |

| Mishri (tobacco applied to teeth) | 4 (2) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Part of mouth where tobacco kept after preparation | Frequency (%) |

| Buccal mucosa (inside lining of cheeks) | 178 (69) |

| Labial mucosa (inside lining of lips) | 65 (25.2) |

| Below the tongue | 11 (4.3) |

| On the teeth | 4 (1.6) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Tobacco chewers | Frequency (%) |

| Current | 247 (95.7) |

| Past | 11 (4.3) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Descriptive statistics | Mean±SD |

| Age of starting to chew tobacco, years | 24±7 |

| Number of years since chewing, years | 16±9.5 |

| Time tobacco kept in mouth per consumption, minutes | 9±5 |

| Tobacco consumed in a day, packets | 3±1.5 |

SD - Standard deviation

The frequencies of the 6-item FTND-ST tool have been described in Table 2. More than three-fourths of the tobacco chewers place their first dip of tobacco after 60 min of waking up; one-fifth of the chewers always swallow the tobacco juice intentionally; and 88% of the tobacco chewers consume >3 packets of tobacco per week.

Table 2.

Frequency and percentage of 6-items of Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence-Smokeless Tobacco among patients in a tertiary care hospital of western India (n=258)

| FTND-ST items | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| How soon after you wake up do you place your first dip? | |

| After 60 min | 200 (77.5) |

| 31-60 min | 43 (16.7) |

| 6-30 min | 13 (5.0) |

| Within 5 min | 2 (0.8) |

| Total | 258 (100.0) |

| How often do you intentionally swallow tobacco juice? | |

| Never | 150 (58.1) |

| Sometimes | 58 (22.5) |

| Always | 50 (19.4) |

| Total | 258 (100.0) |

| Which chew would you hate most to give up? | |

| Any other | 209 (81.0) |

| The first one in the morning | 49 (19.0) |

| Total | 258 (100.0) |

| How many cans/pouches per week do you use? | |

| 1 | 11 (4.3) |

| 2-3 | 21 (8.1) |

| >3 | 226 (87.6) |

| Total | 258 (100.0) |

| Do you chew more frequently during the first hours after waking than during the rest of the day? | |

| No | 224 (86.8) |

| Yes | 34 (13.2) |

| Total | 258 (100.0) |

| Do you chew if you are so ill that you are in bed most of the day? | |

| No | 156 (60.5) |

| Yes | 102 (39.5) |

| Total | 258 (100.0) |

The dependence on SLT and willingness to quit has been detailed in Table 3. Among the 258 SLT users, 20% had a high dependence on SLT and 61% had low willingness to quit tobacco. Out of 258 SLT users, 56% were in precontemplation stage (who are not planning to quit within the next 6 months) and 31% were in contemplation stage (who are planning to quit within the next 6 months).

Table 3.

Frequency and percentage of dependence on smokeless tobacco; willingness to quit scale and stage of change of willingness to quit (n=258)

| Outcome variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Level of dependence | |

| High dependence (≥5 score in FTND-ST) | 52 (20.2) |

| Low dependence (<5 score in FTND-ST) | 206 (79.8) |

| Total | 258 (100.0) |

| Willingness to quit scale | |

| Low willingness to quit (<5 score) | 158 (61.2) |

| High willingness to quit (≥5 score) | 100 (38.8) |

| Total | 258 (100) |

| Stage of change | |

| Precontemplation | 144 (55.8) |

| Contemplation | 79 (30.6) |

| Preparation | 23 (8.9) |

| Action | 7 (2.7) |

| Maintenance | 5 (1.9) |

| Total | 258 (100.0) |

FTND-ST - Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence-Smokeless Tobacco

The association of categorical variables with tobacco dependence has been described using Chi-square test in Table 4. There was no significant association between dependence and age by 40 years cutoff, gender, marital status, occupation, religion, SES group, willingness to quit, and stage of change of tobacco dependence. There was a statistically significant association between dependence and literacy status, occupation requiring travel, and family type. Illiterate patients were three times (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.45–6.56) more likely to develop high dependence for SLT than literate patients. Those patients whose occupation required traveling were 2.4 times (95% CI: 1.20–4.86) more likely to develop high dependence for SLT than patients whose occupation did not require travel. Patients living in the joint family were 2.7 times (95% CI: 1.3–5.5) more likely to develop high dependence than patients living in a nuclear family.

Table 4.

Association of different variables with tobacco dependence (n=258)

| Variables | High dependence (%) | Low dependence (%) | Total (%) | χ2 | P | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of patient by 40 years cutoff (years) | ||||||

| Age <40 | 18 (34.6) | 94 (45.6) | 112 (43.4) | 2.051 | 1.5 | 0.63 (0.34-1.19) |

| Age >40 | 34 (65.4) | 112 (54.4) | 146 (56.6) | |||

| Total | 52 (100) | 206 (100) | 258 (100) | |||

| Gender of patients | ||||||

| Male | 51 (98.1) | 193 (93.7) | 244 (94.6) | 1.557 | 0.21 | 3.44 (0.44-26.88) |

| Female | 1 (1.9) | 13 (6.3) | 14 (5.4) | |||

| Total | 52 (100) | 206 (100) | 258 (100) | |||

| Literacy status | ||||||

| Illiterate | 14 (26.9) | 22 (10.7) | 36 (14.0) | 9.124 | 0.003 | 3.08 (1.45-6.56) |

| Literate | 38 (73.1) | 184 (89.3) | 222 (86) | |||

| Total | 52 (100) | 206 (100) | 258 (100) | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 8 (15.4) | 22 (10.7) | 30 (11.6) | 0.894 | 0.34 | 1.52 (0.64-3.64) |

| Single | 44 (84.6) | 184 (89.3) | 228 (88.4) | |||

| Total | 52 (100) | 206 (100) | 258 (100) | |||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Laborer | 17 (32.7) | 72 (35) | 89 (34.5) | 7.210 | 0.30 | - |

| Farmer | 7 (13.5) | 32 (15.5) | 39 (15.1) | |||

| Service | 7 (13.5) | 12 (5.8) | 19 (7.4) | |||

| Shopkeeper | 9 (17.3) | 36 (17.5) | 45 (17.4) | |||

| Unemployed/retired | 6 (11.5) | 33 (16) | 39 (15.1) | |||

| Driver | 4 (7.7) | 6 (2.9) | 10 (3.9) | |||

| Diamond worker | 2 (3.8) | 15 (7.3) | 17 (6.8) | |||

| Total | 52 (100) | 206 (100) | 258 (100) | |||

| Occupation required travel | ||||||

| Yes | 16 (30.8) | 32 (15.5) | 48 (18.6) | 6.364 | 0.01 | 2.42 (1.20-4.86) |

| No | 36 (69.2) | 174 (84.5) | 210 (81.4) | |||

| Total | 52 (100) | 206 (100) | 258 (100) | |||

| Religion | ||||||

| Hindu | 46 (88.5) | 187 (90.8) | 233 (90.3) | 0.254 | 0.61 | 0.78 (0.3-2.1) |

| Muslim | 6 (11.5) | 19 (9.2) | 25 (9.7) | |||

| Total | 52 (100) | 206 (100) | 258 (100) | |||

| Family type | ||||||

| Nuclear | 28 (53.8) | 142 (68.9) | 170 (65.9) | 12.770 | 0.005 | 1 |

| Joint | 17 (32.7) | 32 (15.5) | 49 (19.0) | 2.7 (1.3-5.5) | ||

| 3rd generation | 7 (13.5) | 32 (15.5) | 39 (15.1) | 1.1 (0.4-2.8) | ||

| Total | 52 (100) | 206 (100) | 258 (100) | - | ||

| SES group | ||||||

| Lower socioeconomic group | 18 (34.6) | 83 (40.3) | 101 (39.1) | 0.561 | 0.45 | 0.79 (0.42-1.48) |

| Upper socioeconomic group | 34 (65.4) | 123 (59.7) | 157 (60.9) | |||

| Total | 52 (100) | 206 (100) | 258 (100) | |||

| Stage of change for quitting SLT | ||||||

| Precontemplation | 27 (51.9) | 117 (56.8) | 144 (55.8) | 6.921 | 0.14 | - |

| Contemplation | 14 (26.4) | 65 (31.6) | 79 (30.6) | |||

| Preparation | 6 (11.5) | 17 (8.3) | 23 (8.9) | |||

| Action | 4 (7.7) | 3 (1.5) | 7 (2.7) | |||

| Maintenance | 1 (1.9) | 4 (1.9) | 5 (1.9) | |||

| Total | 52 (100) | 206 (100) | 258 (100) | |||

| Willingness to quit | ||||||

| Low willingness to quit | 31 (59.6) | 127 (61.7) | 158 (61.2) | 0.072 | 0.788 | 0.92 (0.5-1.7) |

| High willingness to quit | 21 (40.4) | 79 (38.3) | 100 (38.8) | |||

| Total | 52 (100) | 206 (100) | 258 (100) |

OR - Odds ratio; CI - Confidence interval; SES - Socioeconomic status; SLT - Smokeless tobacco

As demonstrated in Table 5, mean number of years since chewing tobacco in high dependence group was 18.92 (±9.7). By comparison, mean number of years since chewing tobacco in low dependence group was 15.77 (±9.39). To test the hypothesis that a number of years since chewing tobacco in high dependence group were associated with statistically significantly higher mean, an independent samples t-test was performed. The independent samples t-test was associated with a statistically significant effect (P = 0.032). Thus, mean number of years since chewing tobacco was statistically significantly higher among high dependence group than low dependence group. Similarly, mean number of packets of tobacco consumed daily (<0.001) was statistically significantly higher among high dependence group than low dependence group. There was no statistically significant difference between the means of age (years), total monthly income, total member consuming tobacco, the age of starting tobacco chewing, amount of tobacco consumed daily (no of packets), duration of chewing tobacco (minutes), among the two groups of high and low dependence.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of continuous variables and results of unpaired t-test for difference of means among the dependence groups (n=258)

| Continuous variables | Groups | n | Mean±SD | P value from t-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | High dependence | 52 | 43.52±12.15 | 0.112 |

| Low dependence | 206 | 40.75±10.92 | ||

| Total monthly income in Indian rupees | High dependence | 52 | 12240.38±7275.05 | 0.114 |

| Low dependence | 206 | 10519.42±5270.92 | ||

| Total members of family consuming tobacco | High dependence | 52 | 1.54±0.78 | 0.387 |

| Low dependence | 206 | 1.44±0.64 | ||

| Age of starting tobacco chewing | High dependence | 52 | 23.31±6.45 | 0.246 |

| Low dependence | 206 | 24.56±7.08 | ||

| Number of years since chewing tobacco | High dependence | 52 | 18.92±9.7 | 0.032 |

| Low dependence | 206 | 15.77±9.39 | ||

| Number of packets of tobacco consumed daily | High dependence | 52 | 3.77±1.99 | <0.001 |

| Low dependence | 206 | 2.56±1.22 | ||

| Number of minutes tobacco is chewed at one time | High dependence | 52 | 8.56±3.88 | 0.271 |

| Low dependence | 206 | 9.43±5.34 |

SD - Standard deviation

DISCUSSION

Dependence on various addictive substances is rampant in this fast-paced world to cope with the day-to-day pressures of life and SLT is one of the most prevalent addictions in India due to its easy availability. The present study attempted to highlight this dependence on SLT among patients attending a tertiary care hospital of western India. The present study found that 20% of the SLT chewers have a high dependence on SLT. A study which used the same FTND-ST tool among patients attending their hospital found two-thirds of their patients having high nicotine dependence.[5] A similar study by Manimunda et al. in Andaman and Nicobar Islands reported a prevalence of 13% high dependency on nicotine.[6] They also reported three-fourths of tobacco users initiated tobacco chewing before 21 years of age,[6] while the current study found that 13% of chewers were <30 years of age. A study in West Bengal reported that 57% of tobacco users started it <15 years of age.[17] This signifies the early initiation of tobacco consumption in India due to various factors such as educational stress and occupational stress among the youth.

The present study reported that 95.7% of the patients were currently chewing tobacco, while the study in Andaman reported almost half of their sample as tobacco users.[6] This high percentage reported in our study might be due to the fact that ours was a hospital-based study. The current study reported that “Mawa” was the most often (60%) consumed SLT form, while the study in Andaman found that “Zarda” was the most common (23%) form being consumed.[6] Their study also highlighted that low educational status was significantly associated with nicotine dependence;[6] the finding was supported by the present study too.

The present study highlighted that only 39% of the SLT chewers had high willingness to quit this habit. A study in West Bengal reported that 63.3% of tobacco users had an intention to quit.[17] Their research also showed that tobacco users who did not intend to quit were highly dependent on tobacco.[17] The present research also highlighted that 60% of those highly dependent on tobacco were unwilling to quit it. A study from Maharashtra and Bihar highlighted that only 38% of SLT users had intentions to quit and only 11% had intentions to quit within the next 6 months.[7] Another study conducted in two states including Gujarat reported that 12% of tobacco users intended to quit within the next 30 days.[18] The study in a hospital-based setting in Bangalore reported 43% of patients had attempted quitting tobacco in the past.[5] The present study reported that 56% and 31% of the SLT users were in precontemplation and contemplation stage of quitting, respectively, while the study in Bangalore reported only 14% and 48%, respectively, in these stages.[5] Further, the current study reported 5% of users in action/maintenance stage while their study found 38% in these stages.[5] However, the present study did not find a significant association between high dependence and willingness to quit or between high dependence and stages of motivational change for cessation. The lack of association suggests the need for efficacious cessation interventions for highly dependent SLT users. The interventions can be tailored to the motivational stage of change in which they are currently in.[5] Increasing the prices of tobacco products has been found to provide greater motivation to quit; but at the same time, an inverse relationship between motivation to quit and dependence has been documented.[19]

The present study reported a significant association between high dependence and occupation requiring travel suggesting that occupational stress might play an important role in tobacco consumption. Patients with occupations such as auto rickshaw driver and cab driver consistently keep tobacco quid (“Mawa”) in their mouths to suppress their appetite and to have better concentration on the road while driving. Long-distance travel is accompanied by boredom and stress which also makes them prone to high consumption of SLT. The present study also highlighted that those patients living in the joint family were more likely to get dependent on SLT than those living in a nuclear family. This might be due to the fact that peer pressure/influence is an important factor in initiation and consumption of tobacco. The study by D'Souza et al. highlighted that about four-fifths of tobacco users report a family member using tobacco.[5]

An analysis of Global Adult Tobacco Survey by Thakur et al. found that risk of tobacco consumption was 3.1 times higher among the poorest compared to richest quintile for SLT forms.[20] There was no significant association found in the present study between socioeconomic status and dependence, the possible reason being that this was a hospital-based study without much comprehensible difference in the socioeconomic status of the patients. The current study also found that patients who were illiterate were more likely to develop a dependence on SLT. Further, a study in Gujarat reported that the likelihood of making a quit attempt is lesser among the less educated people.[8] This highlights the importance of education in halting the tobacco epidemic in the country.

The study has a few limitations. The assessment of SLT consumption was self-reported, so there was a possibility of a recall bias. However, literature suggests that self-report is a valid measure of SLT use.[21] There was a possibility of response bias on asking about their willingness to quit, which was addressed by asking carefully constructed questions in local language. This being a cross-sectional study, causal associations between tobacco dependence and its risk factors could not be made. This was a cross-sectional study, but an attempt was made to highlight the risk factors by calculation of odds ratio (analysis was done as is done in a case–control study). A few confounders (risk factors) such as alcohol consumption, concomitant tobacco smoking, and comorbidities have been missed in the study. Multivariate analysis was not done in the study. The findings are at a single center and may not be generalizable to the general population (this being a hospital-based study).

CONCLUSION

It is concluded from the study that among SLT users attending ENT and dental OPD, 60% had low willingness to quit it and one-fifth were highly dependent. Illiteracy, an occupation requiring travel, living in joint family, number of years of chewing, and number of packets of tobacco chewed daily are significantly associated with high dependence on SLT among the patients. There is a need for the introduction of tobacco cessation interventions in ENT and dental OPD of tertiary care hospitals of western India. A few interventions such as covering tobacco cessation programs under health insurance can be implemented in such OPD.[22] Evidence suggests that dental professionals are effective counselors for tobacco cessation, and this opportunity can be utilized when they attend their OPD.[23,24] Future research can test the effectiveness of such interventions in this OPD.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

ANNEXURE

Annexure 1: Gujarati version of Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence-Smokeless Tobacco and stages of change

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2008: The MPOWER Package. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddy KS, Gupta PC. Report on Tobacco Control in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jha P, Jacob B, Gajalakshmi V, Gupta PC, Dhingra N, Kumar R, et al. A nationally representative case-control study of smoking and death in India. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1137–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Report on Oral Tobacco use and Its Implications in South-East Asia. New Delhi: World Health Organization; 2004. World Health Organization – South-East Asia Regional Office. [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Souza G, Rekha DP, Sreedaran P, Srinivasan K, Mony PK. Clinico-epidemiological profile of tobacco users attending a tobacco cessation clinic in a teaching hospital in Bangalore city. Lung India. 2012;29:137–42. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.95314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manimunda SP, Benegal V, Sugunan AP, Jeemon P, Balakrishna N, Thennarusu K, et al. Tobacco use and nicotine dependency in a cross-sectional representative sample of 18,018 individuals in Andaman and Nicobar Islands, india. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:515. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raute LJ, Sansone G, Pednekar MS, Fong GT, Gupta PC, Quah AC, et al. Knowledge of health effects and intentions to quit among smokeless tobacco users in India: Findings from the international tobacco control policy evaluation (ITC) India Pilot Survey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1233–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarkar BK, Arora M, Gupta VK, Reddy KS. Determinants of tobacco cessation behaviour among smokers and smokeless tobacco users in the states of Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh, India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:1931–5. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.3.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dean AG, Arner T, Sunki G, Friedman R, Lantinga M, Sangam S, et al. Epi Info: A database and statistics program for public health professionals. Atlanta: Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gujarat (India) Factsheet: Global Adult Tobacco Survey 2009-2010. New Delhi: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2010. International Institute for Population Sciences; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; Government of India. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebbert JO, Patten CA, Schroeder DR. The fagerström test for nicotine dependence-smokeless tobacco (FTND-ST) Addict Behav. 2006;31:1716–21. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:390–5. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prugger C, Wellmann J, Heidrich J, De Bacquer D, De Backer G, Périer MC, et al. Readiness for smoking cessation in coronary heart disease patients across Europe: Results from the EUROASPIRE III Survey. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:1212–9. doi: 10.1177/2047487314564728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daoud N, Hayek S, Biderman A, Mashal A, Bar-Zeev Y, Kalter-Leibovici O, et al. Receiving family physician's advice and the 'stages of change' in smoking cessation among arab minority men in Israel. Fam Pract. 2016;33:626–32. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmw090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pradeep K. Social classification – Need for constant updating. Indian J Community Med. 1993;18:2–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.All-India Average Consumer Price Index Numbers for Industrial Workers. New Delhi: Labour Bureau, Government of India; 2017. Labour Bureau, Government of India. Statistical data for labour. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Islam K, Saha I, Saha R, Samim Khan SA, Thakur R, Shivam S, et al. Predictors of quitting behaviour with special reference to nicotine dependence among adult tobacco-users in a slum of Burdwan district, West Bengal, India. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:638–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panda R, Venkatesan S, Persai D, Trivedi M, Mathur MR. Factors determining intention to quit tobacco: Exploring patient responses visiting public health facilities in India. Tob Induc Dis. 2014;12:1. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-12-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross H, Blecher E, Yan L, Hyland A. Do cigarette prices motivate smokers to quit? New evidence from the ITC survey. Addiction. 2011;106:609–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thakur JS, Prinja S, Bhatnagar N, Rana S, Sinha DN. Socioeconomic inequality in the prevalence of smoking and smokeless tobacco use in India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:6965–9. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.11.6965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Post A, Gilljam H, Rosendahl I, Meurling L, Bremberg S, Galanti MR, et al. Validity of self reports in a cohort of swedish adolescent smokers and smokeless tobacco (snus) users. Tob Control. 2005;14:114–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sudeep C, Chaitra T. Tobacco cessation counseling – The roles and responsibilities of a dentist. Int J Adv Res. 2017;5:326–31. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vinod VC, Taneja L, Mehta P, Koduri S. Dental professionals as a counsellor for tobacco cessation: A survey. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2017;29:209–12. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oberoi SS, Sharma G, Nagpal A, Oberoi A. Tobacco cessation in India: How can oral health professionals contribute? Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:2383–91. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.5.2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]