Abstract

Malignant melanoma of soft parts, also termed clear cell sarcoma (CCS), is a rare malignancy of neural crest origin which is different from cutaneous malignant melanoma. Although a trans-location involving chromosomes 12 and 22 is characteristic of clear cell sarcoma and not malignant melanoma, there are a paucity of methods to differentiate the two. Therefore, a study of microsatellite instability (MIN) was undertaken to determine if mechanisms of DNA mismatch repair can differentiate these malignancies. MIN has been described in a variety of malignancies including 25% of malignant melanomas. Paraffin-embedded neoplastic and non-neoplastic cells were obtained from 11 individuals (five males; six females; age range from seven to 60 years) with CCS. Isolated DNA was PCR amplified at 17 separate microsatellite loci using radioactive-labeled primers. Tumor tissue was compared to normal tissue for each analysis. No MIN was detected. Loss of heterozygosity was detected in only one patient at a single locus (IFNA). The lack of MIN in clear cell sarcoma further defines the distinction between this tumor and malignant melanoma. Clinically, local recurrence and metastasis were indicators of poor outcome. The size of the tumor was not a significant prognostic indicator. Local recurrence, satellitosis, or nodal metastasis was not proven to be uniformly fatal. Utilization of chemotherapy and/or radiation demonstrated no obvious survival advantage. The histologic parameters of mitotic rate and the presence of necrosis were not prognostic. Limb-preserving surgical procedures were as effective as amputation for local disease control. The actuarial survival rate was calculated to be 48% at five years.

INTRODUCTION

Clear cell sarcoma (CCS) was defined as a distinct pathologic entity by Enzinger in 1965 [1]. Because this tumor is melanocytic in origin, Chung and Enzinger suggested the term “malignant melanoma of soft parts” in 1983 [2]. CCS is a rare, lethal disease with a calculated actuarial survival rate of only 10% at 20 years [3]. Its slow growth, rarity, and origin, typically in proximity to tendons and aponeuroses of young adults’ feet and ankles, belie its lethal course.

CCS has many overlapping clinical, biological, and structural characteristics with other soft tissue sarcomas and malignant melanoma (Table 1). Recent cytogenetic analyses have demonstrated similarities with melanoma but have distinguished CCS from melanoma by a unique translocation involving chromosomes 12 and 22 [4–10]. Modern molecular analyses have identified a chimeric protein resulting from the fusion gene at the translocation breakpoint including the N-terminal domain of the Ewing sarcoma gene [11]. The information gained to date in the study of CCS has yet to significantly impact the clinical arena.

Table 1.

Clear cell sarcoma: comparison to malignant melanoma

| Clear cell sarcoma | Malignant melanoma | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Histology | Uniform rests of fusiform cells | Less uniform | |

| Clear cytoplasm | |||

| Tendons or aponeuroses | Dermis | ||

| Basophilic nucleoli | Basophilic nucleoli | ||

| Glycogen | Glycogen | ||

| Melanin in 20% [19, 20] | Melanin | ||

| Immunohistochemistry | S-100 positive staining [2] | S-100 positive staining | |

| Electron microscopy | Melanosomes and premelanosomes of “neural crest” origin [21] | Melanosomes, premelanosomes of “neural crest” origin | |

| Cytogenetics | lq, 6q, multiple copies of 7 and 8, t(12;22)(ql3;ql2) ∽50% of cases, chromosome 22 [4–10] | lq, 6q, multiple copies of 7 and 8 [22] | |

| Molecular genetics | Chimeric fusion protein EWS-AFT-1 gene [11,17] (EWS 22qll.2–12 breakpoint; more proximal than in CCS) | Cutaneous malignant melanoma gene on 1p | |

| Microsatellite instability: negative | Microsatellite instability: 3–30% positive [12, 13, 14] | ||

| Age | Young adults | Young adults | |

| Regional spread | Satellites and lymph nodes | Satellites and lymph nodes | |

| Distant metastases | Lung and skeleton | Lung, brain, liver, bone | |

| 10-Year survival | ∽33% overall 2–6 cm size ≥5 cm worse prognosis [3, 18, 23] | Depth of dermis infiltration: | |

| <0.76 mm (thin <1) | 90% | ||

| 0.76–1.49 | 83% | ||

| 1.50–2.49 (intermediate 1–4) | 67% | ||

| 2.50–3.99 | 56% | ||

| 4.00–7.99 (thick >4) | 40% | ||

| ≥8.00 [24] | 25% | ||

The purpose of this investigation is to examine for the presence of microsatellite instability in CCS and to correlate with clinical outcome. Microsatellite instability (MIN) is a harbinger of mismatch repair and is seen in sporadic carcinomas and, importantly, in soft tissue sarcomas and malignant melanoma [12–15]. Therefore, MIN analysis was undertaken in our study to determine its distinguishing role and/or prognostic utility for CCS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

A pathology and oncology tumor registry was used to identify CCS patients. Archival material was then obtained. Pathological confirmation was achieved in each subject and microscope slides were available for collection of neoplastic and non-neoplastic cells. Twelve specimens in 11 individuals collected from two orthopedic oncology groups were examined.

Microsatellite Instability

DNA was extracted from neoplastic and non-neoplastic cells scraped from microscope slides previously evaluated to determine the location of the tumor and normal tissue. Standard PCR amplification was performed on DNA at 17 separate loci: 18q11 (D18S34), 9p21 (IFNA), 5q11.2–13 (D5S107), 1p22 (D1S187), 17p13.1 (D17S786), 11p15.2 (D11S861), 15q11.2 (D15S63), 7q (D7S594), 15q11.2 (GABRB3), 12p13.3 (vWF), 19q13 (DM), 11p14 (D11S904), 13q31 (D13S170), 19q13.4 (D19S254), 17q (D17S579), 12q13 (D12S371), and 22q13 (IL2RB). Heterozygosity indices were greater than 70%. Oligonucleotide primers and sequence data for each locus were obtained from Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL). These loci were chosen because they were in areas of genetic instability seen in other tumors studied for microsatellite instability (e.g., 18q11, 5q11.2–13, vWF, DM); were abnormalities seen at sites in melanoma patients (e.g., 9p21, 1p22); common oncogene sites (e.g., H-RAS, 11p15.2 and TP53, 17p13.1); or contained loci that were unique to sarcomas (e.g., 7q, 11p15).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed on 40 ng of neoplastic and control DNA following established protocols [16]. The forward primer was end-labeled with gamma 32p-ATP (Amersham Corporation, Arlington Heights,IL) for each microsatellite. A single PCR machine, model PTC-150 (MJ Research, Inc., Watertown, MA) was used throughout the analysis. The 10 μl reaction mixture contained 1.25 mM dNTP-S, 12 mM MgCl2, 10 × Taq buffer, Taq DNA polymerase, nuclease-free water, and 2 μM forward and reverse oligonucleotide primers. End-labeling was carried out in a 0.6 ml eppendorf tube with nuclease-free water, 5× kinase buffer, 2 μM forward primer, gamma 32p-ATP, and T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega, Madison, WI). PCR conditions were optimized for each primer. The most common conditions were 27 step cycles for 30 seconds at 94°C, 75 seconds at 55°C, 15 seconds at 72°C, and 72°C for 6 minutes. At the conclusion of PCR, 1.5 μl of sample was added to an eppendorf tube containing 3 μl of stop solution (250 μl of bromophenol blue xylene cyanole dye and 1 ml of formamide). Samples were denatured for 7 minutes at 95°C. The samples were then immediately placed on ice and 3 μl of each sample was loaded onto a 6% acrylamide gel. Electrophoresis was performed at 90 watts for 90 minutes and, after cooling, the gel was transferred to gel blot paper and dried. X-ray film exposure occurred for 1 to 5 days at −70°C.

Microsatellite instability is identifiable at a chromo-some location when DNA sequences gained or lost during aberrant replication are unsuccessfully repaired. Microsatellite instability is a harbinger of defective mismatch repair of DNA. Replication errors (microsatellite instability) are demonstrated repeatedly on the autoradiographs as extra bands in the tumor tissue when compared to normal [12–16].

Histopathology

Histosections for all 11 primary tumors were re-examined by an independent pathologist tabulating mitotic figures and necrosis. Mitoses were counted per 10 high power microscope fields (×400). The presence or absence of tumor necrosis was recorded.

Clinical

Medical record chart reviews were retrospectively undertaken on all 11 patients. Documentation of chemotherapy or radiotherapy was recorded for each individual. Six patients were treated at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and three at University of Kansas Medical Center, and two received treatment at University of Nebraska Medical Center from 1986 to 1996. Standard patient demographics were collected. Outcome was determined from the most recent clinical evaluation for each patient. Actuarial survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Local recurrence, nodal metastasis, and extent and type of definitive primary surgical resection were recorded.

RESULTS

Molecular Genetics

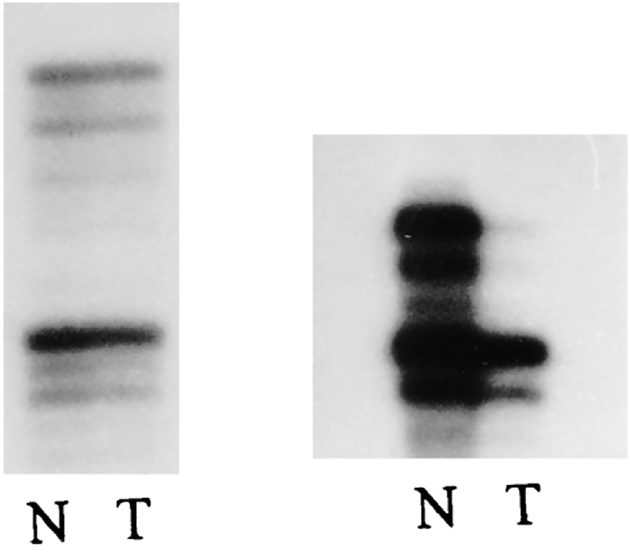

Autoradiographs from 12 specimens using 17 separate probes from different chromosome regions were examined for microsatellite instability. No replication errors were identified when comparing the individual’s tumor DNA with normal DNA. A single instance of loss of heterozygosity was observed in one locus from a tumor specimen (Fig. 1). This reduced hybridization signal at one of the two alleles was identified using the IFNA probe at chromosome band 9p21 in patient 1.

Figure 1.

Left: PCR amplification using D17S579 locus from a patient with clear cell sarcoma displaying no microsatellite instability in tumor (T) tissue compared with normal (N) from the same patient. Right: PCR amplification using IFNA locus from a patient with clear cell sarcoma showing loss of heterozygosity in tumor (T) tissue compared to normal (N).

Loss was confirmed by repeated PCR analysis and auto-radiographic study. Only patient 9 had both a primary and metastatic tumor specimen available for comparison with normal tissue. No microsatellite instability was identified in either of this patient’s tumor specimens compared with the normal tissue. These results are summarized in Table 2. Cytogenetic findings from five individuals are presented. Four of these five demonstrated chromosome 22 abnormalities.

Table 2.

Clear cell sarcoma: histologic and microsatellite instability data

| Patient no. | Mitoses per 10 high power fields (400X) | Necrosis | Microsatellite instability | Loss of heterozygosity | Survivor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | No | No | @9p21 | No |

| 2 | 2 | Yes | No | No | No |

| 3 | 2 | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 4 | <1 | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 5 | 3 | No | No | No | No |

| 6 | 2 | No | No | No | Yes |

| 7 | 8 | No | No | No | Yes |

| 8 | 25 | Yes | No | No | No |

| 9Aa | 2 | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 9Bb | NA | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 10 | 6 | No | No | No | Yes |

| 11 | 2 | No | No | No | No |

Karotype data (cytogenetic data from patients 7, 8, and 9 have been reported elsewhere [4]): patient 7: 66,XY,+X,+i(1)(q10),+2,+3,add(4)(p16),+del(6)(q12),+add(7)(q35),+8,+8,+13,+13,+14,+15,+15,del(16)(q12),+17,+add(19)(q13),add(20)(q13),+21,+22[18]/46,XY[1]; patient 8: 46,XY,+8,t(12;22)(p11.2;p11.2),t(15;15)(p13;q21),−22[13]/46,XY[4]; patient 9: 49,XX,add(2)(q11),+7,+8,+8,add(22)(q11)[4]/50,XX,add(2)(q35),+7,+8,+8,+18,add(22)(q11)[15]/46,XX[1]; patient 10: 46,XX,tas[1]/46,XX[20]; patient 11: 47~49,XY,del(1)(p22p36)×2,+7,+8,+11,t(12;22)(q13;q13),add(13)(p11),add(14)(p11),del(16)(q22),+i(17)(q10),+i(21)(q10)[cp9]/46,XY[11].

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

Primary tumor site.

Lymph node metastasis.

Histopathology

The histopathological review of 12 specimens in 11 individuals with CCS is summarized in Table 2. Low mitotic rates could yield a fatal outcome, while a high rate might result in survival. Necrosis was not predictive of outcome, either. Confirming the results of other authors, mitotic rate and necrosis were not prognostic for CCS.

Clinical

The clinical findings and results are summarized in Table 3. There were six females. The ankle and foot were the most common tumor sites, occurring in six of the 11 individuals. Ten of the 11 tumors were found on the extremities. The size of the primary lesion ranged from 2 to 9 cm with a mean of 4 cm. The tumor size in the patient group with a fatal outcome averaged 4.8 cm (3–9 cm) versus the survivor group with an average size of 4 cm (2–6.5 cm). Ages ranged from 7 to 60 with a 37-year mean.

Table 3.

Clear cell sarcoma: clinical data

| Patient no. | Age at diagnosis (years) |

Size (cm) |

Primary tumor site surgery (months after diagnosis) |

Radiation treatment | Chemotherapy | Lymph node involvement (months after diagnosis) |

Distant metastases | Status (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48 | 4 | Local/leg (0) | Yes | Yes | Yes (6) | Vertebrae, ribs mediastinum | DWD (16) |

| 2 | 38 | 9 | Incomplete/buttock (6)a | No | Yes | Yes (6) | Lungs, brain, colon | DWD (13) |

| 3 | 58 | 5 | Local/forearm (24) | No | No | Yes (72) | No | NED (87) |

| 4 | 58 | 6.5 | Local/wrist (2) | No | No | No nodes, local recurrence (11) | No | NED (50) |

| 5 | 46 | 3 | Local/heel (0) | Yes | Yes | Yes (5) | Lungs | DWD (12) |

| 6 | 15 | 5 | Local/thigh (0) | Yes | Yes | No (91) | No | NED (91) |

| 7 | 60 | 3 | Syme/foot (1) | No | Yes | No (2) | No | DWOD (2) |

| 8 | 29 | 5 | BKA/foot (1) | Yes | Yes | Yes (13), local recurrence | Lungs | DWD (17) |

| 9 | 16 | 2.5 | BKA/heel (0) | No | Yes | Yes (8) | No | NED (68) |

| 10 | 7 | 2 | BKA/ankle (1) | No | Yes | No (19) | No | NED (19) |

| 11 | 36 | 3 | BKA/heel (0) | Yes | Yes | Yes (30) | Lungs | DWD (31) |

Abbreviations: local, local resection of tumor; Syme, Syme amputation (disarticulation of ankle joint); BKA, below-knee amputation; DWD, dead with disease; NED, no evidence of disease; DWOD, dead without disease.

Only patient with lymph node involvement at the time of primary tumor site surgery.

In five cases (patients 7 to 11), aggressive treatment with partial limb ablation was undertaken. Local recurrence occurred in one patient from each of the amputation and limb-salvage surgery groups. Nodal metastasis presented in four of six limb salvage cases compared with three of five amputations. Resection of recurrent proximal tumor satellites or lymphadenectomy for nodal metastasis could be curative. More than one surgery was often performed at the site of the primary tumor because of a delay in diagnosis or to establish clear margins following biopsy. Limb salvage surgery appeared as likely to be curative as amputation.

Nine patients received chemotherapy including the use of multiple cytotoxic agents. Chemotherapy was usually administered as an adjuvant therapy after primary site surgery. The aggressive behavior of CCS and the young age of the patients probably contributed to their clinical decision. Different protocols were used over the time period of 10 years. Patients with distant metastasis underwent chemotherapy. Chemotherapy induced no demonstrable remissions. Five patients received external beam radiation therapy. Four of the five patients with a fatal outcome received radiation therapy.

The length of follow-up from the time at original diagnosis to the most recent clinical examination ranged from two to 91 months with a mean of 37 months. The actuarial survival rate was 48% at five years. The patients with disseminated clear cell sarcoma survived an average 17.8 months (12–31 months) after diagnosis. The follow-up in the survivor group averaged 52.8 months (2–91 months). Patient 7, who was put in the survivor group, died two months after diagnosis of an unrelated stroke.

DISCUSSION

Although CCS and sporadic cutaneous malignant melanoma may behave and appear alike, cytogenetics, and now MIN, further their genetic distinction. Unfortunately, no correlation with outcome for either genetic parameter was demonstrable. CCS’s propensity for lymph node metastasis makes its behavior unlike that of soft tissue sarcomas. However, its deep growth characteristics in cm of size (rather than mm in the dermis) make its biologic behavior unlike melanoma.

Chromosome studies were also available in five of our 11 patients. In two instances (patients 8 and 11) a t(12;22) was found. In addition, trisomy 8 was seen in four of the five patients and trisomy 7 in two of the five patients. These trisomies have been reported previously in CCS patients [10, 17]. Chromosome 22 abnormalities have also been reported frequently [4]. In our study, four of the five cases showed chromosome 22 abnormalities.

Lucas et al. [3] and Sara et al. [18] have concluded that tumor size for CCS smaller or greater than 5 cm is the most important prognostic factor. Our data agree with their findings. The five-year survival rate was calculated at 48% compared with 67% reported by Lucas et al. [3]. Recurrence may occur late in clear cell sarcoma (after 5 to 10 years) compared with malignant melanoma. Interestingly, there is a reported case with metastasis occuring 29 years after the initial surgery for CCS [2]. Our average follow-up was 52 months in our patients. CCS can have a rapid fulminating course or manifest with distant metastatic disease following a long tumor-free hiatus.

Complete excision via limb salvage or ablative surgery is the mainstay of treatment. There is no information on the role of elective lymph node resection. Future studies may explore the role of sentinel lymph node biopsy. Further collaborative clinical and basic science research efforts are required to advance our understanding and help those afflicted with CCS.

Footnotes

Portions of this work were presented at the 4th World Conference on Melanoma in Sydney, Australia, June 10–14, 1997.

REFERENCES

- 1.Enzinger FM (1965): Clear cell sarcoma of tendon and aponeurosis. An analysis of 21 cases. Cancer 18:1163–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung EB, Enzinger FM (1983): Malignant melanoma of the soft parts: a reassessment of clear cell sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 7:405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucas DR, Nascimento AG, Sim FH (1992): Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues—Mayo clinic experience with 35 cases. Am J Surg Path 16:1197–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridge JA, Sreekantaiah C, Neff JR, Sandberg AA (1991): Cytogenetic findings in clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeurosis—malignant melanoma of soft parts. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 52:101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridge JA, Borek DA, Neff JR, Huntrakoon M (1990): Chromosomal abnormalities in clear cell sarcoma. Implications for histogenesis. Am J Clin Pathol 93:26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peulve P, Michot CH, Vannier JP, Tron P, Hemet J (1991): Clear cell sarcoma with t(12;22)(q13–14;q12). Genes Chromosom Cancer 3:400–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reeves BR, Fletcher CDM, Gusterson BA (1992): The translocation t(12;22)(q13;q13) is a nonrandom rearrangement in clear cell sarcoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 64:101–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez E, Sreekantaiah C, Reuter VE, Motzer RJ, Chaganti RSK (1992): t(12;22)(q13;q13) and trisomy 8 are nonrandom aberrations in clear cell sarcoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 64:107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mrozek K, Karakousis CP, Perez-Mesa C, Bloomfield CD (1993): Translocation (12;22)(q13;q12.2–12.3) in clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses. Gene Chromosom Cancer 6:249–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nedoszytko B, Mrozek K, Roszkiewicz A, Kopacz A, Swierblewski M, Limon J (1996): Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses with t(12;22)(q13;q12) diagnosed initially as malignant melanoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 91:37–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zucman J, Delattre O, Desmaze C, Epstein AL, Stenman G, Speleman F, Fletchers CDM, Aurias A, Thomas G (1993): EWS and ATF-1 gene fusion induced by t(12;22) translocation in malignant melanoma of soft parts. Nature Genetics 4:341–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quinn AG, Healy E, Rehman I, Sikkink S, Rees JL (1995): Microsatellite instability in human non-melanoma and melanoma skin cancer. J Inv Derm 104:309–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peris K, Keller G, Chimenti S, Amantea A, Kerl H, Hofler H (1995): Microsatellite instability and loss of heterozygosity in melanoma. J Inv Derm 105:625–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Talwalkar VR, Scheiner M, Hedges LK, Butler MG, Schwartz HS (1998): Microsatellite instability in malignant melanoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 104:111–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin SS, Hurt WG, Hedges LK, Butler MG, Schwartz HS (in press): Microsatellite instability in sarcomas. Ann Surgical Oncol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheiner M, Hedges L, Schwartz HS, Butler MG (1996): Lack of microsatellite instability in giant cell tumor of bone. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 88:35–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Limon J, Debiec-Rychter M, Nedoszytko B, Liberski PP, Babinska M, Szadowska A (1994): Abberration of chromosome 22 and polysomy of chromosome 8 as non-random changes in clear cell sarcoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 72:141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sara AS, Evans HL, Benjamin RS (1990): Malignant melanoma of soft parts (clear cell sarcoma). A study of 17 cases with emphasis on prognostic factors. Cancer 65:367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bearman RM, Noe J, Kempson RL (1975): Clear cell sarcoma with melanin pigment. Cancer 36:977–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackenzie DH (1974): Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses with melanin production. J Pathol 114:231–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukai M, Torikata C, Iri H, Mikata A, Kawai T, Hanaoka H, Yakumaru K, Kaglyama K (1984): Histogenesis of clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses. An electron-microscopic, biochemical, enzyme histochemical, and immunohistochemical study. Am J Pathol 114:264–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muir PD, Gunz FW (1979): A cytogenetic study of eight human melanoma cell lines. Pathology 11:597–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eckhardt JJ, Pritchard DJ, Soule EH (1983): Clear cell sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 27 cases. Cancer 52:1482–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balch CM, Soong SJ, Shaw HM, Urist MM, McCarthy WH (1992): An analysis of prognostic factors in 8500 patients with cutaneous melanoma. In: Cutaneous Melanoma, 2nd ed Balch CM, Houghton AN, Milton GW, Sober AJ, Soong SJ, eds. JB Lippincott Company, Philadelphia, p. 183. [Google Scholar]