Abstract

We investigated whether an association exists between genetic variants of the hum an obesity (OB or leptin) gene and body mass index (BMI) or weight in subjects with Prader–Willi syndrome (PWS) and in age- and gender-matched lean and obese subjects without PWS. The study included 51 subjects with PWS (mean age = 17.7 ± 9.5 years, BMI = 29.7 ± 8.3 kg/m2); 50 non-PWS obese subjects (mean age = 18.2 ± 10.8 years, BMI = 33.3 ± 9.5 kg/m2); and 53 non-PWS lean subjects (mean age = 17.8 ± 9.5 years, BMI = 19.5 ± 2.9 kg/m2). Allele sizes were determined via standard polymerase chain reaction of the D7S1875 locus, a dinucleotide repeat polymorphism close to the OB gene and classified as trichotomous (homozygous < 208 bp, heterozygous < 208/≥ 208 bp, homozygous ≥ 208 bp) or dichotomous (homozygous < 208 bp or not). Non-PWS males showed a marked decrease in weight with larger alleles while females did not (interaction effect, p < 0.05). Comparable effects were not observed among the PWS subjects. Associations between BMI and genotype were statistically significant (r = 0.22, one-tailed p < 0.05) and comparable to previous research among the non-PWS subjects < 1 8 years, but not the adults (r = 0.05, one-tailed p = 0.38). Correlations were not statistically significant among either the adult or non-adult PWS subjects.

Keywords: BMI, D7S1875 alleles, genetic polymorphisms, obesity, OB gene, Prader–Willi syndrome

Prader–Willi syndrome (PWS), generally sporadic in occurrence, is characterized by infantile hypotonia, hypogonadism, feeding difficulties in infancy but early onset of childhood obesity secondary to hyperphagia, mental deficiency, short stature, small hands and feet, and minor facial anomalies (1–6). A bout 70% of Prader–Willi syndrome patients have a paternally derived de novo interstitial DNA deletion of approximately 3–4 megabases from the 15q11q13 chromosome region. In addition, about 25% have maternal disomy of chromosome 15 and the remaining percentage have biparental inheritance in norm al appearing chromosomes, submicroscopic deletions or genetic imprinting mutations (3, 7–10).

PWS is the most common genetic cause of morbid obesity and obesity is the most significant health problem in affected individuals (2, 3, 11). Several factors contribute to obesity in PWS including hyperphagia, decreased physical activity, decreased metabolic rate and inability to vomit (3, 12). In addition, PWS individuals may have 40–50% body fat which is two to three times more than normal, and the fatness pattern appears to be sex reversed with males having more fat than females have (11, 13, 14). The heaviest deposition of subcutaneous fat in Prader–Willi syndrome individuals is in the trunk and limb regions (11).

Candidate genes that are imprinted with paternal specific expression have been localized within the PWS chromosome region. One of these is the SNRPN gene located adjacent to a putative imprinting center hypothesized to control the imprint switching during gametogenesis. Candidate genes have also been identified for obesity. One such gene is the leptin or OB gene localized on chromo-some 7 in humans and it produces a secreted protein, leptin, in adipose tissue (15). It plays a role in feeding behavior and metabolism (15, 16) by binding to its receptor, OB-R, in the brain (17). The levels of OB messenger RNA and leptin are increased in humans with obesity (18) with higher levels of OB messenger RNA reported in obese women than in obese men (19). Human obesity may be due to a reduced sensitivity of leptin to its receptor, and a secondary increase of plasma leptin levels or leptin may simply be a marker of the size of the adipose mass (20). Recently, we reported a significant positive correlation between leptin levels and body mass index (BMI) in subjects with PWS and with obesity (21).

To identify whether a causal relationship exists between leptin and obesity, Comings et al. (22) examined the genetic variants of the hum an OB gene and BMI. They studied the dinucleotide repeat polymorphism, D7S1875, which is located close to the OB gene on chromosome 7, in a group of adult non-Hispanic Caucasians. They found a significant correlation of D7S1875 allele size and BMI for males and females combined and in females alone, particularly in young adults, with a higher BMI in subjects with D7S1875 allele size less than 208 base pairs for both males and females. Their findings suggested that genetic variants of the OB gene (measurable by the D7S1875 locus) are causally involved in hum an obesity and possibly in behavior disorders (e.g. anxiety, depression) sometimes found in obese subjects. They concluded that their results were consistent with a polygenic inheritance of obesity with greater involvement of genetic factors, particularly in women and younger individuals.

Because of our interest in the role of genetic factors and obesity, particularly in subjects with PWS, we sought to examine the association between genetic variants of the hum an OB gene (D7S1875) and obesity in subjects with PWS and to compare with lean and obese comparison subjects without PWS.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

This investigation was approved by the institutional review board of Vanderbilt University. We analyzed the D7S1875 locus, a dinucleotide repeat polymorphism close to the OB gene, in three groups of subjects (Table 1). The study included: a) 51 subjects with PWS (25 females and 26 males, mean age ± standard deviation (SD) = 17.7 ± 9.5 years, range = 2–44 years); b) 50 non-PWS obese subjects (27 females and 23 males, mean age = 18.2 ± 10.8 years, range = 3–47 years); and c) 53 non-PWS lean subjects (27 females and 26 males, mean age = 17.8 ± 9.5 years, range = 2–42 years). Obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 27 for subjects older than or equal to 15 years of age and ≥ 23 for ages 10–14 years. The threshold for obesity classification for children less than 10 years of age was calculated as BMI being equivalent to age in years plus 13 for males, and age in years plus 14 for females (23). The proportion of children (i.e. subjects < 18 years of age) was highly comparable in the three subject groups: a) 52% of females and 50% of males were < 18 years of age in the PWS group; b) 56 and 52% in the obese comparison group; and c) 59 and 58% in the lean comparison group.

Table 1.

Prader–Willi syndrome, lean and obese subject characteristics and genetic data

| Prader-Willi* | Lean control | Obese control*** | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | |

| Subjects | 26 | 25 | 51 | 26 | 27 | 53 | 23 | 27 | 50 |

| Age: average ± SD | 17.69 ± 9.01 | 17.72 ± 10.10 | 17.71 ± 9.46 | 17.30 ± 9.88 | 18.33 ± 9.32 | 17.83 ± 9.52 | 19.70 ± 12.69 | 16.96 ± 8.92 | 18.22 ± 10.79 |

| Range | 6.0–36.0 | 2.0–44.0 | 2.0–44.0 | 2.0–36.0 | 3.0–42.0 | 2.0–42.0 | 3.0–47.0 | 3.0–34.0 | 3.0–47.0 |

| BMI: average ± SD | 29.75 ± 7.92 | 29.59 ± 8.78 | 29.67 ± 8.27 | 19.60 ± 3.50 | 19.38 ± 2.29 | 19.50 ± 2.92 | 33.33 ± 11.21 | 33.29 ± 7.99 | 33.30 ± 9.50 |

| Range | 18.6–55.6 | 16.0–45.2 | 16.0–55.6 | 13.0–25.8 | 15.4–24.6 | 13.0–25.8 | 23.1–75.6 | 22.1–54.1 | 22.1–75.6 |

| D7S1875 alleles <208 | 28 | 28 | 56 | 28 | 32 | 60 | 29 | 34 | 63 |

| D7S1875 alleles >208 | 24 | 22 | 46 | 24 | 22 | 46 | 17 | 20 | 37 |

Deletion of 15q11q13 = 29/51 (56.9%); maternal disomy 15 = 14/51 (27.5%); non-deletion = 5/51 (9.8%); imprinting mutation = 2/51 (3.9%); translocation 13; 15 = 1/51 (2.0%); 13/51 (25.5%) PWS subjects defined as not obese.

BMI = body mass index = weight in kilogram divided by height in meters squared.

For < 10years of age, obesity is defined for males as BMI > age in years +13 and for females as BMI > age in years +14; for 10–14 years of age, obesity is defined for males and females as BMI >23; for > 15 years of age, obesity is defined for males and females as BMI >27.

Twenty-nine subjects with PWS had the 15q11q13 deletion identified by high resolution chromosome analysis and/or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) using 15q11ql3 probes (e.g. SNRPN). Fourteen PWS subjects had uniparental maternal disomy of chromosome 15 (both 15s from the mother) determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using DNA microsatellites from chromosome 15q following protocols described by Butler et al. (24). Two subjects with PWS were determined to have imprinting mutations by DNA methylation analysis but with no recognizable chromosome 15 deletion or uniparental disomy. One individual with PWS was found to have a translocation involving chromosome 15 [i.e. t(13; 15)] and 5 patients were classified only as non-deletion PWS subjects (parental DNA was not available). All subjects in our study were unrelated Caucasians without significant health problems. Height and weight were obtained on all subjects and BMI was calculated (weight in kilograms divided by the height in meters squared). PWS subjects judged to be non-obese were on diet restriction and engaged in exercise programs and were not treated with hormone therapy (e.g. growth, testosterone or estrogen), and/or were young individuals before the onset of childhood obesity.

Molecular analysis

We used the D7S1875, a polymorphic dinucleotide repeat, close to the OB gene on chromosome 7 in this study (22). The heterozygosity index for D7S1875 is 80%. The primers for this locus were purchased from Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL). The forward primer was end-labeled with gamma 32P-ATP (Amersham Cooperation, Arlington Heights, IL).

Briefly, genomic DNA was used with PCR for 25 cycles beginning for 1 minute at 94°C, 2 minutes at 57°C, and 10 minutes at 72°C following protocols described previously (24). The PCR products were run on a 6% polyacrylamide gel and then exposed to an X-ray film. The fragment size was determined by comparison with a DNA sequence of PUC18 of known size from Gibco BRL (Gaithersburg, MD) and allele size recorded for each subject. The PCR fragment sizes were classified according to Comings et al. (22) as: a) both alleles < 208 bp; b) one allele < 208 bp and one ≥ 208 bp; or c) both alleles ≥ 208 bp.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted on the basis of trichotomous and dichotomous, genotype-based classifications: a) homozygous < 208/< 208 bp, heterozygous ≥ 208/< 208 bp, homozygous ≥ 208/≥ 208 bp; and b) homozygous < 208/< 208 bp, ≥ 208/≥ 208 bp. These classification strategies address different perspectives on the potential effect of the smaller allele on obesity: a) whether an increasing presence of the smaller allele (i.e. 0, 1 or 2 alleles < 208 bp) exerts an effect; and b) whether the presence of the homozygous condition (< 208/< 208 bp) exerts an effect.

Summary statistics (e.g. frequencies, means, standard deviations) were calculated. Tests of between-group differences were conducted via one-way and factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA), via non-parametic methods and Pearson and point-biserial correlations were calculated as appropriate. Directional hypotheses were tested when warranted on the basis of previous research.

Results

General characteristics of the three subject groups are presented in Table 1. The average BMIs (± SD) were 19.5 ± 2.9, 33.3 ± 9.5, and 29.7 ± 8.3 for the lean, obese and Prader–Willi subjects, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in BMI between the PWS and obese comparison subjects; the expected difference was observed between the lean subjects and both the PWS and obese comparison subjects (p < 0.01).

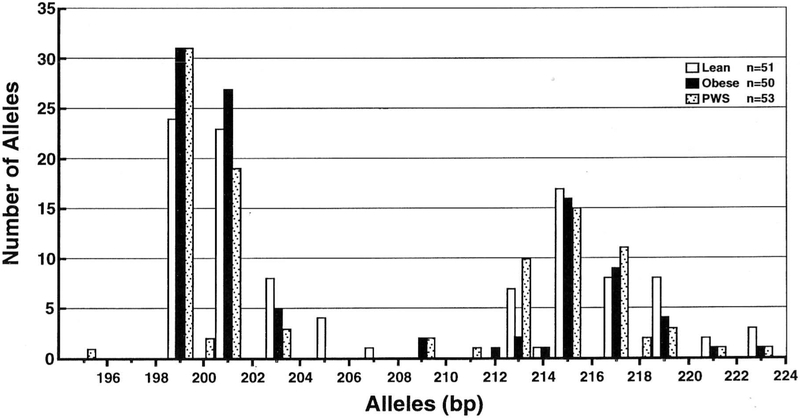

A histogram representing the distribution of the D7S1875 alleles in the three subject groups (PWS, non-PWS obese, and non-PWS lean) is shown in Fig. 1. The allele size ranged from 195 to 223 bp. The distribution of allele sizes in each of the three subject groups suggested a bimodal pattern. Non-parametric statistical analyses (the median test) of the distributions of alleles by size (i.e. numbers of base pairs) evaluated whether groups (PWS, obese comparison, lean comparison) differed in terms of distribution location and shape. The lean comparison group exhibited a significantly different distribution than did the obese comparison group (p = 0.05) with the preponderance of lean subjects’ alleles being greater than the median and a preponderance of obese subjects’ alleles being less than or equal to the median. The alleles of the 50 obese comparison subjects included 63 which were smaller than 208 bp and 37 which were larger than 208 bp. The alleles of the 53 lean comparison subjects included 60 which were smaller than 208 bp and 46 which were larger than 208 bp. No difference in allele size distribution was found among the obese versus lean PWS subjects (p = 0.85). These observations provide further evidence that the obesity associated with PWS was not influenced by the size of the D7S1875 allele. The allele distribution was similar to that reported by Comings et al. (22) in their 211 adult, non-Hispanic Caucasian subjects (98 males and 113 females) with an average of 54 years and an age range of 29–75 years. The most frequent allele size reported by Comings et al. (22) was 199 bp, which was also true for our three groups of subjects. There was no difference in the number of individual D7S1875 alleles (< 2 0 8 or > 208 bp) between the males and females within each of our three subject groups (Table 1). In addition, no significant differences were observed in the number of alleles in the PWS subgroups (i.e. deletion or maternal disomy).

Fig. 1.

The distribution of D7S1875 allele sizes among PWS, lean, and obese subjects.

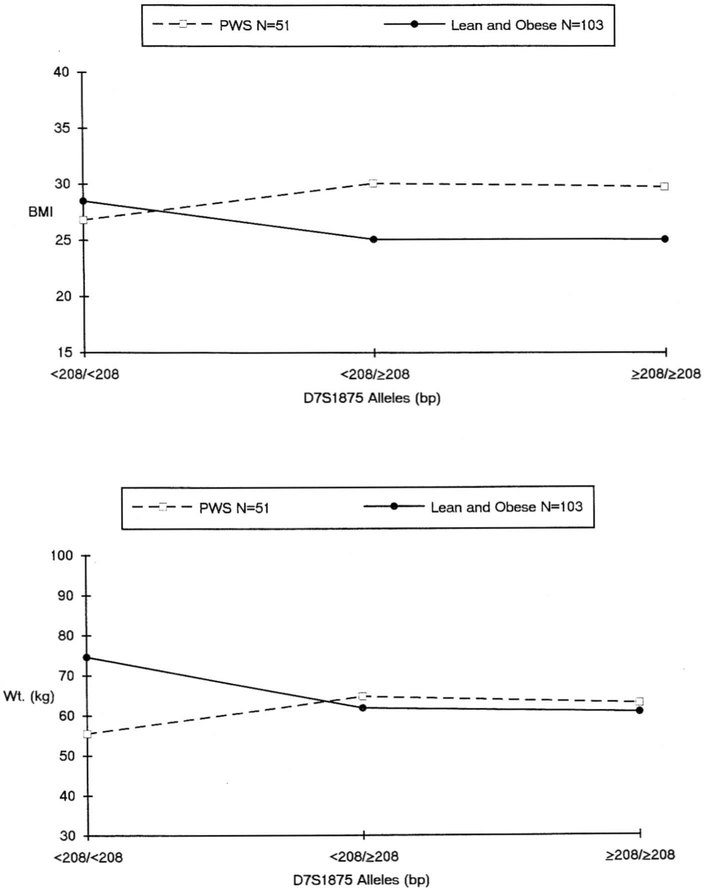

Fig. 2 depicts BMI and weight for the PWS and (combined) comparison subjects and the comparison with D7S1875 allele sizes. Body weights and BMIs (mean ± SD) of the (combined) lean and obese comparison subjects by allele size genotypes were: a) < 208/< 208 bp, n = 33, weight = 74.6 ± 36.0 kg, BMI = 28.5 ± 11.6 kg/m2; b) < 208/≥ 208 bp, n = 57, weight = 61.9 ± 31.1 kg, BMI = 25.1 ± 8.0 kg/m2; and c) ≥ 208/≥ 208, n = 13, weight = 60.9 ± 37.7 kg, BMI = 25.1 + 11.5 kg/m2. Comparable data for the PWS subjects were: a) < 208/< 208 bp, n = 17, weight = 55.5 ± 29.1 kg, BMI = 29.1 ± 7.0 kg/m2; (b) < 208/≥ 208 bp, n = 22, weight = 64.8 ± 26.4 kg, BMI = 30.1 ± 9.7 kg/m2; and c) ≥ 208/≥ 208, n = 12, weight = 63.1 ± 26.5 kg, BMI = 29.8 ± 7.7 kg/m2. When allele sizes were classified as a dichotomy (homozygous < 208/< 208 or not), an association between homozygosity for the smaller D7S1875 allele size and body size (BMI, one-tailed p = 0.05; weight, one-tailed p < 0.05) was demonstrated among the (combined) lean and obese comparison subjects. This association was not observed among the PWS subjects.

Fig. 2.

Average BMI across D7S1875 allele groups among PWS and control (lean and obese) subjects (top panel). Average weight across D7S1875 allele groups among PWS and control (lean and obese) subjects (bottom panel).

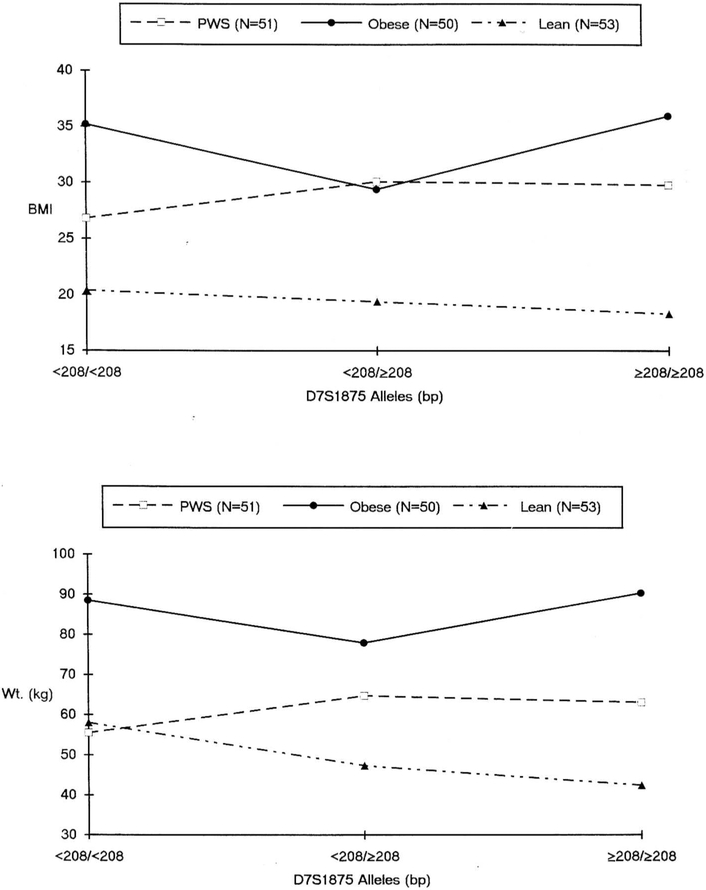

The lean and obese comparison subjects and PWS subjects are distinguished in Fig. 3. In comparison to the non-PWS obese subjects, a progressive but not statistically significant decrease in BMI and weight is suggested among the non-PWS lean subjects across the three genotypes. Among the lean comparison subjects BMI averaged 20.4 kg/m2 for the < 208/< 208 bp homozygotes, 19.4 kg/m2 for the heterozygotes, and 18.3 kg/m2 for the 208/208 bp homozygotes; among the obese comparison subjects BMI averaged 35.2, 29.4, and 36.0 kg/m2, respectively. Among lean subjects without PWS, weight averaged 58.0 kg for the < 208/< 208 bp homozygotes, 47.4 kg for the heterozygotes, and 42.4 kg for the ≥ 208/≥ 208 bp homozygotes; among the obese comparison subjects weight averaged 88.5, 78.0, and 90.4 kg, respectively. When the genotypes are classified as dichotomies (homozygous < 208/< 208 bp or not) and data are analyzed via directional t tests, the trend is further suggested for BMI (p = 0.08) and the effect is significant for weight (p < 0.01) among the non-PWS lean subjects. A comparable trend was not observed among the age- and gender-matched obese comparison subjects.

Fig. 3.

Average BMI across D7S1875 allele groups among PWS, lean, and obese control subjects (top panel). Average weight across D7S1875 allele groups among PWS, lean, and obese control subjects (bottom panel).

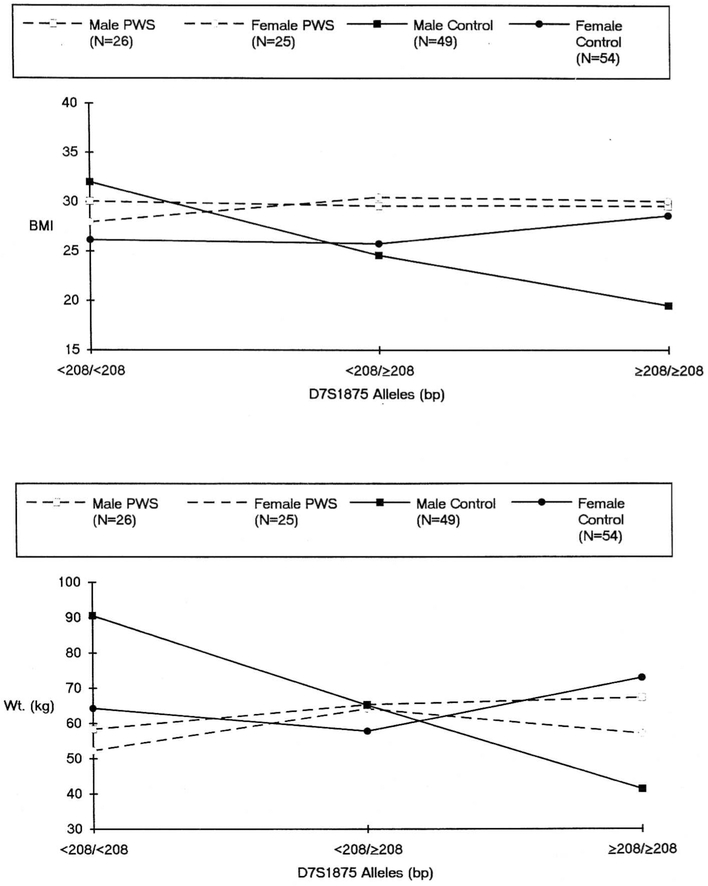

Fig. 4 depicts BMI and weight by gender and genotype among the (combined) lean and obese comparison subjects and the PWS subjects. When genotype is classified as a trichotomy and data analyzed via two-way ANOVA, an interaction effect between genotype and gender is suggested among the comparison subjects (F = 2.95, p = 0.06). The trend among males was that of a reduction in BMI with decreasing presence of the smaller allele. BMI averaged 32.0, 24.6, and 19.5 kg/m2 for the homozygous < 208/< 208 bp, heterozygous, and homozygous ≥ 208/≥ 208 bp conditions, respectively. Female comparison subjects exhibited stability across the three respective genotypes (average BMI = 26.2, 25.8, and 28.6 kg/m2, respectively). When the genotypes are classified as a dichotomy (homozygous < 208/< 208 bp or not) the interaction effect of gender and genotype on BMI is statistically significant (F = 4.17, p < 0.05). Comparable analyses for weight demonstrated a statistically significant gender by genotype interaction effect when the genotype is classified as a trichotomy (F = 3.5, p < 0.05) and a similar trend (F = 3.3, p = 0.07) when genotype is dichotomized. No such interaction effects of gender by genotype were observed for either BMI or weight among the PWS subjects under either genotypic classification.

Fig. 4.

Average BMI across D7S1875 allele groups among PWS and control subjects by gender (top panel). Average weight across D7S1875 allele groups among PWS and control subjects by gender (bottom panel).

In keeping with previous research (22), data were analyzed via a correlational model to examine the potential association between adiposity (BMI) and genotype as a function of age group (with our age groups being defined as < 1 8 years or ≥ 1 8 years). Separate age group-specific analyses were conducted among the (combined) lean and obese comparison subjects and those with PWS. When genotype is expressed as a trichotomy, correlation coefficients express the association between BMI and the number of small alleles possessed (i.e. 0, 1, or 2 alleles < 208 bp). When the approach of Comings et al. (22) is employed, the association between BMI and genotype is expressed as point-biserial coefficients (i.e. genotype is dichotomized as homozygous < 208/< 208 bp or not). While the correlation coefficients are low (r = 0.22) when statistically significant, they are comparable to those observed by Comings et al. (22) among their younger subjects. The data in Table 2 demonstrate an association between genotype and adiposity among subjects without PWS who are less than 18 years of age, but not among those who are greater than 18 years of age. No association between adiposity and genotype was evident among subjects with PWS in either age group. These data may be interpreted as evidence that among subjects less than 18 years of age who do not have PWS, approximately 5% of the variance in adiposity is associated with genetic variation in the hum an OB gene. Obesity among non-PWS adults and among PWS subjects of all ages is not similarly associated with OB gene variants.

Table 2.

Correlations between obesity (BMI) and D7S1875 genotypes in children and adults with and without Prader–Willi syndrome

| Age group | Non-PWS | PWS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | r2 | p | r | r2 | p | |

| BMI versus trichotomized genotypea | ||||||

| < 18 years | 0.216 | 0.047 | 0.052 | 0.025 | 0.001 | 0.452 |

| ≥ 18 years | −0.009 | 0.000 | 0.476 | 0.068 | 0.005 | 0.373 |

| BMI versus dichotomized genotypeb | ||||||

| < 18 years | 0.221 | 0.049 | 0.047 | −0.166 | 0.028 | 0.209 |

| ≥ 18 years | 0.047 | 0.002 | 0.378 | 0.116 | 0.013 | 0.290 |

p values under a directional hypothesis (one-tailed).

Trichotomous genotype coding as number of alleles<208 bp: 0 = ≥208/≥208; 1 = < 208/≥208; 2 = <208/<208.

Dichotomous genotype coding as presence or absence of homozygosity for <208 bp: 0 = ≥ 208/≥ 208 or < 208/≥208; 1 = <208/<208.

Discussion

Our data compare favorably with the obesity and D7S1875 allele size data reported by Comings et al. (22). They reported a significant association with weight and allele size with a progressive decrease across the three D7S1875 genotype groups (< 208 homozygotes, heterozygotes and ≥ 208 homozygotes) for the whole group of male and female non-Hispanic Caucasian adults. However, we found a stronger association between both BMI and weight and allele size among males without PWS than among females without PWS. Males showed a statistically significant, progressive decrease in BMI and weight across the three genotypes. This finding was not observed among PWS males or females. As reported by Comings et al. (22), we also found that the younger non-PWS subjects showed more of an effect of D7S1875 allele size on adiposity than did the adults. The proportion of covariance (r2) between D7S1875 allele size and BMI observed among younger non-PWS subjects in our investigation (5%) is in keeping with the 3–6 % reported by Comings et al. (22) among subjects aged 16–20 years and 26–30 years. As they reported (in subjects ages 16–70 years) and from adoption studies, genetic factors are more likely to be involved in obesity in the young than in older subjects. The incidence of obesity increases for a larger percentage of the aging population where acquired factors such as a sedentary life style may become more important.

Although our data demonstrate and Comings et al. (22) reported an association with genetic variants (D7S1875) of the leptin or OB gene and obesity, previous studies have generally failed to identify any mutations of the hum an OB gene in obese subjects (25). However, evidence suggests that mutations involved in polygenic disorders may be outside of gene exons and that polymorphic nucleotide repeats could play a role in regulating expression of genes which are close by (22, 26–28). This assumption led Comings et al. (22) to test for associations between alleles of dinucleotide repeats in the vicinity of the human leptin or OB gene and variables relating to weight, eating and other behaviors. Our study followed up on this assumption. In addition, they reported that the OB gene had a primary effect on psychiatric symptoms and may play a direct causal role in depression and anxiety associated with obesity.

In summary, our data support an earlier observation of genetic variants of the leptin or OB gene detectable by the D7S1875 locus and an association with weight or BMI and allele size with a progressive decrease of BMI or weight with increasing allele size in subjects without PWS. This investigation demonstrates that no such association is present among subjects with PWS, the most common genetic form of morbid obesity in man. Although subjects with PWS have a recognized chromosome 15 abnormality which is associated with severe obesity, our study demonstrates that variation in D7S1875 allele size of the OB gene on chromosome 7 does not exert a detectable effect on obesity in these subjects.

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by NICHD (P01HD30329). We thank Lee Beth Kilgore for the expert preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cassidy SB. Prader–Willi syndrome. Curr Prob Pediatr 1984: 14: 1–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler MG, Meaney FJ, Palmer CG. Clinical and cytogenetic survey of 39 individuals with Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1986: 23: 793–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler MG. Prader–Willi syndrome: current understanding of cause and diagnosis. Am J Med Genet 1990: 35: 319–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holm VA, Cassidy SB, Butler MG, Hanchett JM, Greenswag LR, Whitman BY, Greenberg F. Prader–Willi syndrome: consensus diagnostic criteria. Pediatrics 1993: 91: 398–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler MG, Levine GJ, Le JY, Hall BD, Cassidy SB. Photoanthropometric study of craniofacial traits of individuals with Prader–Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1995: 58: 38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler MG. Prader–Willi syndrome: a guide for parents and professionals. Roslyn Heights, TN: Visible Ink, 1995: vol. 4, 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mascari MJ, Gottlieb W, Rogan PK, Butler MG, Waller DA, Armour JAL, Jeffreys AJ, Ladda RL, Nicholls RD. The frequency of uniparental disomy in Prader–Willi syndrome: implications for molecular diagnosis. New Eng J Med 1992: 326: 1599–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholls RD. Genomic imprinting and candidate genes in the Prader–Willi and Angelman syndromes. Curr Opin Genet Dev 1993: 3: 445–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buiting K, Saitoh S, Gross S, Dittrich B, Schwartz S, Nicholls RD, Horsthemke B. Inherited microdeletions in the Angelman and Prader–Willi syndromes define an imprinting centre on human chromosome 15. Nat Genet 1995: 9: 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christian SL, Robinson WP, Huang B, Mutirangura A, Lino MR, Nakao M, Surti U, Chakravarti A, Ledbetter DH. Molecular characterization of two proximal deletion breakpoint regions in both Prader–Willi and Angelman syndrome patients. Am J Hum Genet 1995: 57: 40–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meaney FJ, Butler MG. Characterization of obesity in the Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome: fatness patterning. Med Anthropol Quart 1989: 3: 294–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill JO, Kaler M, Spetalnick B, Reed G, Butler MG. Resting metabolic rate in Prader–Willi syndrome. Dysmorph Clin Genet 1990: 4: 27–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butler MG, Meaney FJ. An anthropometric study of 38 individuals with Prader−Labhart−Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1987: 26: 445–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meaney FJ, Butler MG. The developing role of anthropologists in medical genetics: anthropometric assessment of the Prader−Labhart−Willi syndrome as an illustration. Med Anthropol 1989: 10: 247–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature 1994: 372: 425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pelleymounter MA, Cullen MJ, Baker MB, Hecht R, Winters D, Boone T, Collins F. Effects of the obese gene product on body weight regulation in ob/ob mice. Science 1995: 269: 540–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tartaglia L, Dembski M, Weng X, Deng N, Culpepper J, Devos R, Richards G, Campfield LA, Clark F, Deeds J, Muir C, Sanker S, Moriatry A, Moore K, Smutko J, Mays G, Woolf E, Monroe C, Tepper R. Identification and expression cloning of a leptin receptor, OB-R. Cell 1996: 83: 1263–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton BS, Paglia D, Kwan AY, Deitel M. Increased obese mRNA expression in omental fat cells from massively obese humans. Nature Med 1995: 1: 953–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lonnqvist F, Arner P, Nordfors L, Schalling M. Overexpression of the obese gene (ob) in adipose tissue of human obese subjects [see comments]. Nature Med 1995: 1: 950–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maffei M, Stoffel M, Barone M, Moon B, Dammerman M, Ravussin E, Bogardus C, Ludwig DS, Flier JS, Talley M. Absence of mutations in the human ob gene in obese/diabetic subjects. Diabetes 1996: 45: 679–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butler MG, Moore J, Morawiecki A, Nicolson M. Comparison of leptin protein levels in Prader–Willi syndrome and control individuals. Am J Med Genet 1998: 75: 7–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Comings DE, Gade R, MacMurray JP, Muhleman D, Peters WR. Genetic variants of the human obesity (ob) gene: Association with body mass index in young women, psychiatric symptoms, and interaction with the dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) gene. Mol Psychiatry 1996: 1: 325–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Himes JH, Dietz WH. Guidelines for overweight in adolescent preventive services: recommendations from an expert committee. Am J Clin Nutr 1994: 59: 307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butler MG, Christian SL, Kubota T, Ledbetter DH. Brief clinical report: a 5-year-old white female with Prader–Willi syndrome and a submicroscopic deletion of chromosome 15q11q13. Am J Med Genet 1996: 65: 137–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montague CT, Farooqi IS, Whitehead JP, Soos MA, Rau H, Wareham NJ, Sewter CP, Digby JE, Mohammed SN, Hurst JA, Cheetham CH, Earley AR, Barnett AH, Prins JB, O’Rahilly S. Congenital leptin deficiency is associated with severe early-onset obesity in humans. Nature 1997: 387: 903–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krontiris TG, Devlin B, Karp DD, Robert NJ, Risch N. An association between the risk of cancer and mutations in the HRAS1 minisatellite locus. New Eng J Med 1993: 329: 517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green M, Krontiris TG. Allelic variations of reporter gene activation by the HRAS1 minisatellite. Genomics 1993: 17: 429–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kennedy GC, German MS, Rutter WJ. The minisatellite in the diabetes susceptibility locus IDDM2 regulates insulin transcription. Nature Genet 1995: 9: 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]