Abstract

Finely tuned mechanisms enable the gastrointestinal tract to break down dietary components into nutrients without mounting, in the majority of cases, a dysregulated immune or functional host response. However, adverse reactions to food have been steadily increasing, and evidence suggests that this process is environmental. Adverse food reactions can be divided according to their underlying pathophysiology into food intolerances, when, for instance, there is deficiency of a host enzyme required to digest the food component, and food sensitivities, when immune mechanisms are involved. In this Review, we discuss the clinical and experimental evidence for enteric infections and/or alterations in the gut microbiota in inciting food sensitivity. We focus on mechanisms by which microorganisms might provide direct pro-inflammatory signals to the host promoting breakdown of oral tolerance to food antigens or indirect pathways that involve the metabolism of protein antigens and other dietary components by gut microorganisms. Better understanding of these mechanisms will help in the development of preventive and therapeutic strategies for food sensitivities.

Adverse reactions to food, expressed as food sensitivity or food intolerance, are on the rise1–3. This increase in prevalence cannot be explained by genetic drift, suggesting a critical role of yet unknown environmental factors as modifiers of disease expression4. Studies have linked food sensitivities to a variety of microbial signals that could be induced by enteric infections or alterations in the commensal gut microbiota4,5. However, the specific mechanisms behind these associations remain unclear. In this Review, we examine two major pathways of food sensitivities, diet–microorganism and host–microorganism interactions, and discuss the mechanistic evidence through which they can favour specific adverse reactions to food. Protein antigens in particular can become substrates of gut microorganism metabolism, which can result in altered antigenicity6 or in the production of metabolites that directly affect tolerogenic responses7. We also discuss treatment strategies designed to target these pathways that could be developed to prevent or better treat food sensitivities8.

Adverse reactions to food

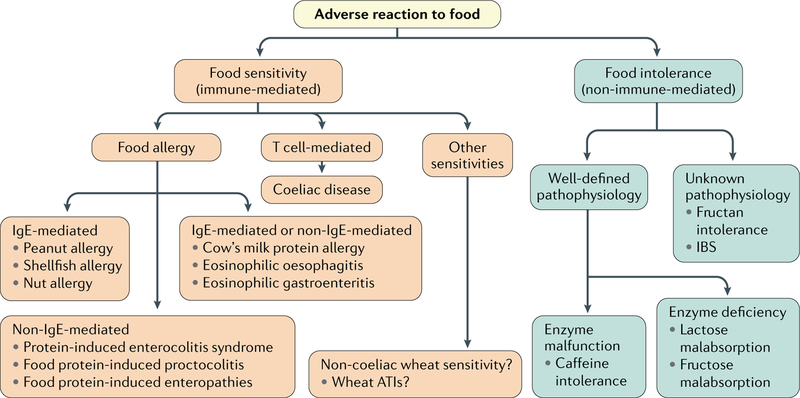

It is estimated that one-fifth of the population world-wide experiences adverse reactions to dietary components1. Manifestations are diverse depending on the underlying aetiology and pathophysiological processes involved1 (FIG. 1). Food intolerances involve non-immune mechanisms, such as lactose maldigestion, in which there is an inability to break down the disaccharide lactose owing to primary or secondary deficiency of β-galactosidase (lactase). As a consequence, undigested lactose reaches the colon, where it is fermented by the gut microbiota, leading to gas production (hydrogen, carbon dioxide and methane) and bloating9. In other clinical entities, such as functional gastrointestinal disorders for which food is often suspected to be a trigger, the specific food components and underlying mechanisms responsible for symptom generation remain unclear10–12. Some of these patients do not receive a conclusive diagnosis even following placebo-controlled food challenge. It remains uncertain whether this difficulty in reaching a conclusive diagnosis results from insufficient laboratory diagnostics or whether such patients have central nervous system-driven mechanisms (nocebo effect) that are not identifiable by diagnostic methods currently available13.

Fig. 1 |. Classification of adverse reaction to food according to underlying pathophysiology.

Adverse reactions to food can be divided into food intolerances (non-immune mediated) and food sensitivities (immune mediated) according to their underlying pathophysiology. Both types can be subclassified into specific diseases on the basis of their pathophysiology. ATI, α-amylase-trypsin inhibitor; IgE, immunoglobulin E.

Food sensitivities with allergic pathophysiology involve immunoglobulin E (IgE) mechanisms, non-IgE-mediated mechanisms or a combination of both (FIG. 1). IgE-mediated food allergy requires sensitization characterized by production of food allergen-specific IgE14. Upon re-exposure to the allergen, allergen-specific IgE, which is bound to FcεRI (also known as FCER1A) on mast cells and basophils, becomes crosslinked and releases mediators, such as histamine, that cause acute symptoms14. A strong response to the allergen could lead to anaphylaxis, which is defined as a severe allergic reaction of rapid onset affecting multiple tissues that can cause death14. Non-IgE-mediated food allergy includes different medical conditions such as protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome and food protein-induced proctocolitis. Although they are classified as non-IgE-mediated diseases, some studies suggest that there is mucosal IgE production but at insufficient circulating levels to be detected15. In contrast to well-defined IgE-mediated food allergy, the diagnostic approaches and immune mechanisms underlying these conditions are not well understood, although TNF has been implicated according to evidence15–17. Another group of chronic conditions with allergic pathophysiology and poorly understood mechanisms involving both IgE and non-IgE responses includes cow’s milk protein allergy, eosinophilic oesophagitis and gastroenteritis. In eosinophilic oesophagitis and gastroenteritis, the nature of the food allergen remains undetermined1,14. On the other hand, coeliac disease is a well-characterized CD4+ T cell-mediated food sensitivity with autoimmune-like features triggered by ingestion of gluten-containing cereals in genetically predisposed individuals harbouring HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 genes18. In addition to coeliac disease, non-allergy, non-coeliac wheat sensitivity (NCWS) has become a common condition19. The prevalence of NCWS has been reported to vary from 0.6–6.0% in Western populations and up to 13% if self-reported NCWS is considered20–23. However, the prevalence of NCWS cannot be estimated with confidence owing to the lack of biomarkers and specific diagnostics24. Gluten, and other components in wheat, including fructans and α-amylase-trypsin inhibitors (ATIs), have been identified as potential culprits for the induction of symptoms25–27. For instance, ATIs engage the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)–protein MD2 (also known as LY96)–CD14 complex, lead to upregulation of maturation markers and elicit release of pro-inflammatory cytokines that lead to inflammation27,28.

As with other food sensitivities and autoimmune diseases29–31, the prevalence of coeliac disease is increasing worldwide2,32. Because not all people with genetic risk develop coeliac disease, and because the increase in prevalence has been too quick to be explained by genetic drift, environmental factors, such as introduction of gluten to infant diets (timing, amount and frequency), breastfeeding patterns, alterations in the gut microbiota (dysbiosis) and infections, have been suspected4,33–35.

Microbial environmental factors

Several groups have reported the association of food sensitivity with practices that can affect intestinal microbiota composition such as early food behaviours, antibiotic intake or caesarean delivery36–38. In coeliac disease, results from prospective birth cohort studies have been published; however, the studies do not support a statistically significant effect of early feeding practices on coeliac disease development39,40. Although the conclusions do not apply to the general population, follow-up analyses are beginning to raise the hypothesis that a combination of factors might have a role. Indeed, genetic and epidemiological studies showed an association between viral and bacterial infections and the onset of coeliac disease and food allergies41–46, suggesting that repeated microbial infections early in life trigger food sensitivities, particularly in individuals with more moderate genetic predisposition34,47,48. A prospective study provided evidence that an increased frequency of rotavirus infections, which generally affects the small intestine and leads to a transient increased intestinal permeability, predicts increased risk of coeliac disease autoimmunity in genetically predisposed individuals carrying HLA risk alleles for coeliac disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM)41. Interestingly, intestinal rotavirus infection is also implicated in the autoimmunity leading to T1DM49. It remains to be determined whether rotavirus vaccination can prevent the onset of coeliac disease, as inconsistent findings have been reported50,51. Consistent with the hypothesis that infection might have a role in coeliac disease aetiology, studies identified the occurrence of small intestinal Campylobacter jejuni or adenoviral infection, as well as influenza diagnosis or hepatobiliary virus infections such as hepatitis C, to be substantive risk factors in the development of coeliac disease43,45,52,53. Shi et al.48 have also shown that enteric infections by helminths can act as an adjuvant for the response to dietary antigens, which has implications for allergic responses to food. It will be important to investigate the effect of microbial infections early in life, as even a transitory gastro-intestinal infection in the vulnerable neonatal or infant period is potentially able to disturb the local mucosal and systemic immature immune system.

In addition to the support provided by clinical and epidemiological studies for an association between intestinal bacterial and viral infections and food sensitivities54–62 (TABLE 1), the role of a dysbiotic gut microbiota has also been evoked. Indeed, several groups have reported intestinal dysbiosis in coeliac disease and food allergy56–59,62–65. For instance, it has been shown that changes in key bacterial groups in infancy were associated with the development of food allergy later in life. One study suggested that a specific intestinal microbial signature with a positive correlation between the genus Clostridium sensu stricto and serum-specific IgE was able to distinguish between infants with IgE-mediated food allergy and those without IgE mediation66. In addition, coeliac disease-associated dysbiosis seems to be characterized by Proteobacteria expansion and the presence of opportunistic pathogens in the proximal small intestine67. Animal studies have provided some mechanistic insight and support the notion that responses to different antigens or allergens can be modulated by the microbial milieu of the intestine68–73. The bulk of mechanistic evidence arises from basic studies that elucidate interactions of specific microorganisms with the antigen or allergen itself, as well as the imprinting of pro-inflammatory or tolerance induction in the host by microorganisms. The following sections expand on these concepts.

Table 1 |.

Summary of studies linking food sensitivity and microbial factors

| Food sensitivity |

Outcome | Study type | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coeliac disease | Intestinal dysbiosis in coeliac disease | Humans (children and adults) | 54–57,59,67 |

| Altered duodenal microbiota in treated coeliac disease non-responding to gluten-free diet | Humans (adults) | 58 | |

| Association with environmental practices altering intestinal microbiota (caesarean section and antibiotic and PPI intake) and coeliac disease | Humans (children and adults) | 36,37 | |

| Severity of gluten immunopathology in mice is dependent on gut microbiota background | Mouse models | 68 | |

| Implication of gut microbiota in gluten metabolism and gluten-peptide immunogenic modification | In vitro and mouse models | 6,85 | |

| Association of infections with coeliac disease and incitement of food sensitivity by virus | Humans (adults) and mouse models | 5,41–44,46,52 | |

| Inflammatory responses to microbial ligands in cells of carriers of the coeliac disease-associated risk allele SH2B3 | In vitro and humans (adults) | 177 | |

| Food allergy | Association of bacterial richness in early infancy and food allergy | Humans (children) | 60,61 |

| Association of specific bacterial profiles with food allergies | Humans (children and adults) | 62,65,66 | |

| Enteric infection can act as an adjuvant for the response to dietary antigens in food allergy | Mouse models | 48 | |

| Commensal bacteria regulate the production of IgE and increase susceptibility to food allergy in animal models | Mouse models | 69,70 | |

| Commensal bacteria protect against food allergy in animal models | Mouse models | 71–73 | |

| Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in microbial sensing receptors and atopy | Humans (children and adults) | 151–153 |

PPI, proton-pump inhibitors; IgE, immunoglobulin E.

Microorganism-diet interactions

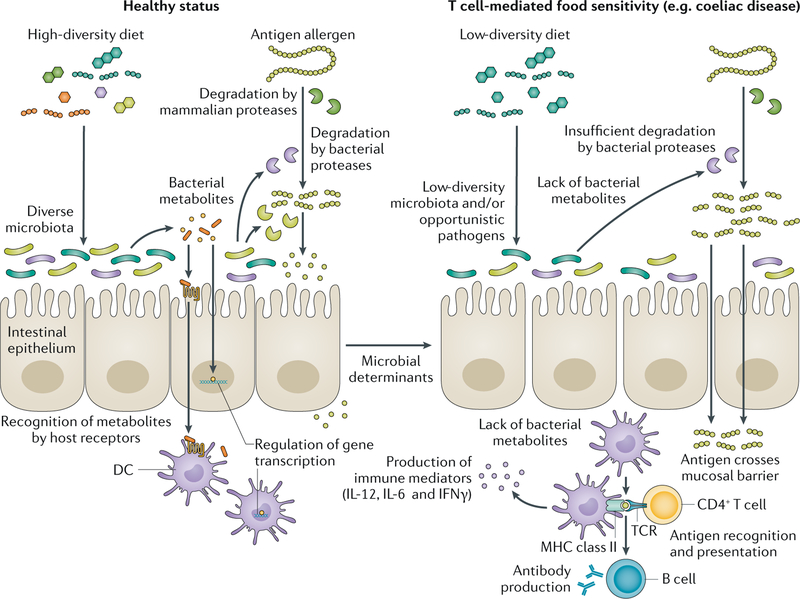

A study in humans demonstrated that long-term dietary patterns constitute an important determinant of gut microbiota enterotypes74. Others indicated that short-term diet alters microbial community structure75, gene expression75 and metabolite production76,77. Studies in animal models have linked the intake of omega-3 fatty acids, and of prebiotic (galactooligosaccharides or inulin) exposure during perinatal and post-weaning periods, with the induction of beneficial changes in gut microbiota-derived metabolites associated with tolerance mechanisms that decrease allergic sensitization78,79. However, the exact compositional characteristics of a beneficial gut microbiota, as well as the mechanisms by which those changes prevent disease, have not been completely elucidated. Dietary food components that are neither absorbed nor metabolized by the host become bacterial substrates, which subsequently leads to the production of bacterial metabolites, such as the short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) butyrate80 (FIG. 2). In addition, the gut microbiota has the capacity to modify the chemical structures of numerous dietary molecules, including allergens or antigens6.

Fig. 2 |. Microbial metabolism in the pathogenesis of food sensitivities.

Dietary patterns constitute an important determinant of gut microbiota diversity, altering microbial community structure and metabolite production. Dietary food components that are not metabolized by the host become bacterial substrates. Products of bacterial metabolic activity, such as the short-chain fatty acids, are recognized by host receptors in dendritic cells (DCs) and epithelial cells promoting homeostasis through immune modulatory pathways and barrier protection (left side). Microorganisms can also metabolize food protein antigens through specific enzymatic activity, increasing or reducing their immunogenicity. Alteration of bacterial composition and/or the functional and metabolic capabilities of resident bacteria, as well as intestinal infections (microbial determinants), could promote T cell-mediated food sensitivities in genetically susceptible people (right side). A non-balanced diet can promote a microbiota with a lower diversity and metabolic output. The lack of bacterial metabolites could impair gut homeostasis, predisposing the host to develop food sensitivities. Dysbiosis could also lead to partially degraded food antigens, producing immunogenic peptides that translocate the mucosal barrier better than non-partially digested antigens. Once in the lamina propria, food antigens (such as gluten peptides) will be recognized by antigen-presenting cells such as DCs harbouring major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II genes, which mediate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-12, IL-6 and IFNγ). In the case of coeliac disease, an adaptive immune response with gluten-specific T cells and B cells producing antibodies against gluten will be generated. TCR, T cell receptor.

Immunogenicity of food antigens.

The intestinal microbiota is considered a metabolic organ that vastly complements the host’s metabolic activities81. One mechanism through which bacteria could affect immune responses to dietary components is through bacterial metabolism of antigens. This aspect is of particular relevance in coeliac disease, in which proteolytic-resistant gluten proteins are the undeniable trigger of T cell-mediated inflammation82. Gluten is a mix of proteins rich in proline and glutamine residues that confer unusual resistance to degradation by mammalian enzymes82. This incomplete digestion generates, in vitro, high-molecular-mass oligopeptides, which, when bound to antigen-presenting cells (APCs), are capable of activating a T cell response associated with coeliac disease83. These large peptides constitute attractive substrates for energy by bacteria colonizing the gastrointestinal tract. Several studies have shown that the human gastrointestinal tract, including the proximal small intestine, harbours gluten-degrading bacteria such as Rothia spp. or Lactobacillus spp. that are able to utilize non-digested gluten peptides84–88. Caminero et al.6 have demonstrated that, in addition to mammalian enzymes, duodenal bacteria participate in gluten metabolism in vivo. Indeed, depending on the type of bacteria present, the end result will be increased or reduced immunogenicity of the produced peptides6 (FIG. 2). For instance, specific opportunistic pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa further degrade digestive protease-modified gluten peptides, producing shorter peptides that retain immunogenic sequences. These bacterially modified peptides translocate through the intestinal epithelial barrier better than peptides produced by human digestive proteases, a mechanism that might facilitate the interaction of peptides with the immune system of the host. By contrast, core members of the human duodenal microbiota such as Lactobacillus spp. can degrade and detoxify gluten peptides produced by human or opportunistic pathogen proteases6. Thus, there exist complex and sequential metabolic events in which mammalian and bacterial proteases synergize with each other to produce a diverse peptide output with variable immunogenic capacity. Interestingly, Lactobacillus spp., which predominately reside in the small intestine89, have been reported to be more abundant and diverse in healthy individuals than in patients with coeliac disease57. Further studies are required to test whether this reduced abundance of lacto-bacilli in patients with coeliac disease is either caused by an ongoing (gluten-induced) inflammation and restored upon a gluten-free diet or whether restoring the presence of lactobacilli improves the gluten-induced pathophysiology. Interestingly, viral or bacterial intestinal infection in mice could supress the abundance of certain microbial groups involved in gluten metabolism such as Lactobacillus spp., thereby affecting coeliac disease onset90.

Modification of gluten by the intestinal microbiota is not limited to its degradation. Gluten deamidation — a chemical reaction that removes an amide functional group in the amino acids asparagine or glutamine — by human transglutaminase 2 (TGase2; also known as TGM2), the coeliac disease-associated autoantigen, is a key step in the disease process91. TGase2 converts glutamine residues to glutamate, which increases peptide binding affinity to HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 heterodimers expressed on APCs that initiate the CD4+ T cell-mediated inflammation characteristic of coeliac disease. In a study published in 2017, it was shown that transamidation of gluten by microbial transglutaminase from Streptomyces mobaraensis could reduce the immunogenicity of gluten92. Thus, the notion is beginning to emerge that microbial composition is a key factor in modulating the immunogenicity of dietary antigens. This aspect could apply to other food sensitivities, as many food allergens, such as egg and peanut proteins, are resistant to degradation by mammalian proteases93. However, further studies are required to determine whether all allergens or antigens within a specific food (for example, the greater than ten allergens in peanut protein or the multiple immunogenic peptides described in coeliac disease)94 could be fully degraded or metabolized by microbial ecosystems to a degree that effectively improves clinical symptoms. Thus, although questions based on colonization capacity and stability of the strains in the human gastrointestinal tract can be raised, microorganisms with the ability to degrade or modify immunogenic food antigens or allergens could be an attractive field for therapeutic development in the future.

Metabolites with immunomodulatory function.

Under steady state, the intestinal microbiota has an essential role in maintaining a tolerogenic gut environment that prevents an inflammatory response against foreign antigens, mainly by promoting epithelial integrity and tolerogenic regulatory T (Treg) cell function95. Many of these effects are mediated by immunomodulatory metabolites that result from the bacterial metabolism of dietary substrates (FIG. 2). Bacterial metabolic products such as SCFAs or tryptophan-derived metabolites have been shown to directly regulate mucosal immune function and the intestinal barrier, affecting the predisposition to food sensitivity96,97. Specifically, alterations of these metabolites have been described in patients with food sensitivities57,98.

Butyrate, which is derived from the bacterial metabolism of dietary fibre99, regulates both the proportions and the functional capabilities of forkhead box protein P3 (FOXP3)+ Treg cells7,100,101, which are central to the maintenance of tolerance to food antigens or allergens102,103. A study in mice showed that high-fibre feeding reshaped gut microbial ecology and increased the release of SCFAs, improving oral tolerance to food allergens by activating retinal dehydrogenase activity in CD103+ dendritic cells (DCs)104. This feeding regimen also boosted IgA production and enhanced T follicular helper and mucosal germinal centre responses, regulating numerous protective pathways in the gastrointestinal tract that are necessary for immune non-responsiveness to food antigens104. The importance of bacterial metabolites in maintaining epithelial barrier integrity under tissue distress was demonstrated in a study by Fukuda et al.105 who showed that the SCFA acetate was able to promote epithelial integrity during enteropathogenic infection in mice. In agreement with this finding, others showed that members of the Firmicutes phylum (such as Clostridia), through IL-22 induced by bacteria, protected against allergic sensitization to food allergens by regulating innate lymphoid cell function and intestinal epithelial permeability72. In addition, IL-15, a pro-inflammatory cytokine upregulated in the epithelium and the lamina propria in coeliac disease106, led to dysbiosis with an overall reduction of butyrate and a decreased abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria, which was associated with a higher susceptibility to intestinal inflammation107. Findings also indicate that butyrate quenches the inhibitory effects of IL-12 on FOXP3+ Treg cell expansion (B.J., unpublished observations), which was shown to be upregulated by mucosal DCs in the presence of high IL-15 together with retinoic acid (RA) and shown to lead to loss of tolerance (LOT) to gluten106. In food allergy, dietary intervention with a butyrate-producing Lactobacillus strain for 6 months alleviated cow’s milk allergy symptoms in infants and was associated with changes in the composition of the intestinal micro-biota108. Furthermore, it was shown that Bifidobacterium spp., via production of acetate, promoted intestinal epithelial integrity and protected against lethal infection, potentially alleviating food allergy in mice by inducing apoptosis in mast cells105.

Another emerging example relates to the production of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligands by microbial metabolism of dietary substrates rich in tryptophan109. The indole group in the amino acid tryptophan is metabolized by bacteria, such as Lactobacillus spp. or Streptococcus spp., releasing potent stimulators (3-indolepropionic acid, indole-3-carboxaldehyde or indole) of AhR65,97. This receptor is a cytosolic ligand-dependent transcription factor that is highly expressed in the intestinal epithelium and other immune cells that regulate important homeostatic functions in the gut, including maintenance of barrier function and maturation of the immune system109,110. Activation of AhR positively affects DC phenotype and function during allergic sensitization and could lead to protection in a mouse peanut allergy model111–113. Although using dietary interventions and their effects on the gut microbiota to avoid food sensitivities is still far from clinical application, deciphering beneficial bacterial molecules and their dietary precursors is of high interest, as it could lead to sensible dietary guidelines in the future.

Other microbial determinants.

Commensal intestinal bacteria protect the host from developing adverse food reactions. Specifically, direct modulation of peripherally derived FOXP3+ Treg (pTreg) cell responses by commensals has been described. For instance, Bacteroides fragilis was shown to promote IL-10 production114 and pTreg cell differentiation115,116. Accordingly, germ-free mice have been shown to develop more severe allergies117 and more severe immunopathology in mouse models of gluten sensitivity68. Live bacteria, but also dead bacteria or bacterial components such as lipopolysaccharides present in the diet of germ-free mice, can promote Treg cells118,119. The use of certain live bacteria as a probiotic treatment with either mouse-derived or human-derived strains attenuated food sensitivity71,72,120,121. For instance, prenatal and postnatal supplementation of Bifidobacterium spp., such as Bifidobacterium breve M-16V and Bifidobacterium longum BB536, has been suggested to prevent allergic diseases122, which is in line with evidence that signals from the commensal microbiota suppress IgE production and basophil development123. However, the mechanisms behind these findings are not always well described. Combinations of probiotic bacteria such as VSL#3 (Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus acidophilus, B. breve, B. longum, B. longum subsp. infantis and Streptococcus thermophilus) have been tested in both food allergy and coeliac disease on the basis of their immunomodulatory capacity and their ability to degrade wheat protein124–126. However, currently, these products cannot be recommended in clinical practice, as it is unknown whether such probiotic preparations are able to degrade the specific immunogenic regions of gluten. Moreover, their clinical efficacy has not been rigorously tested. Production of immunomodulatory molecules such as SCFAs by probiotic strains could confer protection to food components105. However, other bacterial compounds produced dependently or independently from dietary substrate metabolism could be of interest. Production of specific anti-inflammatory molecules such as immunomodulatory serpins produced by B. longum NCC2705 has been shown to prevent gluten-induced immunopathology in mice127. Interestingly, serpin expression has been identified to be specifically reduced in the small intestine of patients with coeliac disease128. Furthermore, extracellular vesicle-derived protein from B. longum KACC91563 was shown to alleviate food allergy through mast cell suppression129. On other hand, probiotics have been proposed in combination with oral immunotherapy for food allergy. For instance, oral immunotherapy with peanut proteins and Lactobacillus strains induced long-lasting tolerance in children with peanut allergy in a randomized pilot study of 62 children stratified by age130. The use of dead bacteria such as Escherichia coli for encapsulation of modified peanut protein has also been proposed131.

Induction of pro-inflammatory events

The default immune response to ingested dietary antigens is both local and systemic active unresponsiveness, an essential physiological process in the small intestine referred to as oral tolerance, which protects mammals from developing food sensitivities132,133. Environmental factors, such as enteric pathobionts, have the capacity to dictate the type of mucosal immune response and can shift the tolerogenic regulatory immune response towards dietary antigens into an inflammatory T helper cell response, which consequently results in LOT to that antigen. Thus, the question arises as to how microbial infections can affect molecular host signalling pathways that are involved in the development of LOT to dietary antigens such as gluten in coeliac disease or in the development of other food sensitivities or allergies.

Barrier dysfunction and innate immunity.

Intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) have an important role in mediating oral tolerance to dietary antigens or allergens by producing cytokines and/or signalling mediators that affect the cell types involved in oral tolerance, as well as in maintaining an intact epithelial barrier, which restricts access of larger, potentially immunogenic, macromolecules134–136. In addition, coeliac disease is characterized by a leaky intestinal barrier137,138, and an increased intestinal permeability is suspected to trigger the sensitization towards dietary antigens in food allergy139. Most importantly, it is suspected that frequent microbial infections involving the intestinal tract could increase intestinal permeability134. Many pathogens interact with the intestinal barrier, underlining the importance of bacterial–host interactions in both health and disease. These effects might result from direct modification of tight junction proteins, activation of receptors in epithelial cells such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) or different kinase-mediated effects140–143. Pathogens might alter the intestinal mucous layer by either improving mucus degradation or inhibiting the normal commensal cues for mucus production144. Moreover, the intestinal epithelium influences tolerance to microbial or food antigens and/or allergens by conditioning mucosal APCs towards either development of CD103+ tolero-genic DCs, by releasing transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) and RA145,146 under homeostatic conditions, or a pro-inflammatory T helper 1 (TH1) cell or TH2 cell response when barrier function is disrupted147.

Loss of epithelial barrier function and innate immunity is fundamental to the pathogenesis of food sensitivities. IECs and innate immune cells of the lamina propria express pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that endow them with the ability to recognize microbial products or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). The role of PRRs in food sensitivity is complex. Detection of PAMPs enables the intestinal epithelium to activate signalling pathways that could lead to food sensitivities148. Furthermore, it has been suggested that dietary antigens can also be recognized by PRRs149. In this context, the previously mentioned wheat proteins, ATIs, could have an important role, particularly for coeliac disease and NCWS27,28. On the other hand, TLRs, such as TLR4, are thought to be essential for the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis150. For instance, TLR4-dependent signals provided by the microbiota inhibit the development of allergic responses to food allergens according to experimental evidence38. There is also an association of food sensitivities with single nucleotide polymorphisms in microbial sensing receptors such as TLR6 or TLR9 (REFS151–153). Thus, depending on the context, PRRs could have a protective or pathogenic role in the response to food antigens.

Studies have linked the role of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) to food sensitivities154–158. ILCs are uniquely capable of responding to the gut microbiota owing to their tissue localization and rapid primary responses159. It has been described that commensal microorganisms promote a crosstalk between innate myeloid and lymphoid cells that leads to immune homeostasis in the intestine160. However, the implications of this crosstalk in food sensitivities have not been addressed. Chua et al. have shown that intestinal dysbiosis featuring abundance of Ruminococcus gnavus is associated with allergic diseases in infants through activation of group 2 ILCs (ILC2s)161. IL-25-producing intestinal epithelial tuft cells have been shown to initiate intestinal ILC2 responses to parasitic worm infection in animal models162. However, it is too early to make firm conclusions about the role of ILCs in food sensitivities.

T helper 1 cell-mediated immunity to food antigens.

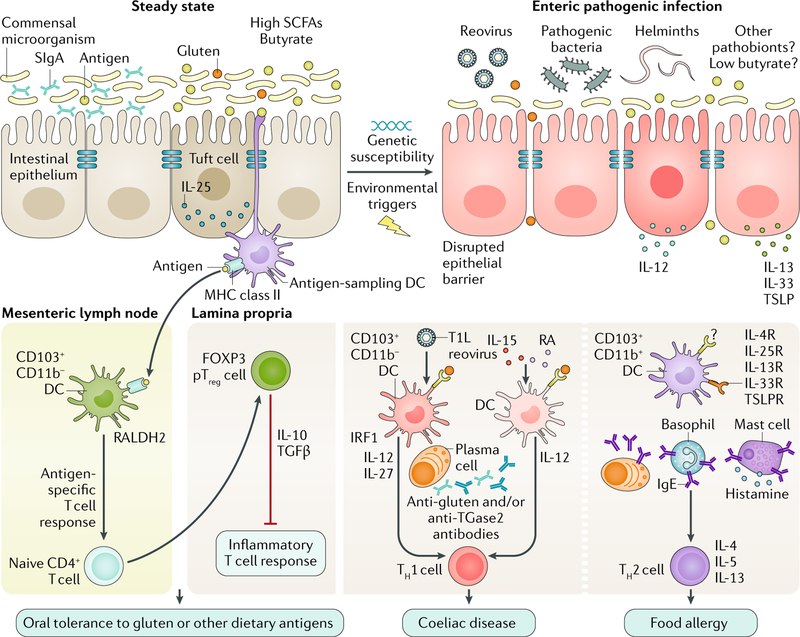

In the absence of tissue distress, mucosal CD103+ DCs, which are at high frequency in the small intestinal lamina propria and mesenteric lymph nodes, present luminal dietary antigen to naive CD4+ T helper cells and promote their differentiation into pTreg cells via a TGFβ-dependent and RA-dependent mechanism163,164. Esterházy et al.146 demonstrated that the mucosal interferon regulatory factor 8 (IRF8)-dependent CD103+CD11b− DC subset contains the most potent inducers of pTreg cells and oral tolerance under steady state conditions and that this subset displays the most potent tolerogenic gene expression pattern, including high expression of genes encoding TGFβ and the RA-catalysing enzyme retinal dehydrogenase 2 (RALDH2). The maturation and maintenance of this highly tolerogenic CD103+ DC subset are dependent on enteric environmental conditions132, and an alteration of RALDH2 activity is associated with impaired oral tolerance in animal models165. However, it is intriguing that the DC subset with the greatest tolerogenic potential also expresses pro-inflammatory IL-12 and IL-15 and drives TH1 cell responses to intestinal infections166,167. This DC subset also expresses Tlr9, which binds bacterial and viral DNA, and triggers signalling cascades that lead to a pro-inflammatory cytokine response146 (FIG. 3).

Fig. 3 |. Microorganisms can promote food sensitivities.

Under healthy conditions, short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria help maintain oral tolerance to dietary antigens by reinforcing the intestinal epithelial cell (IEC) barrier to prevent uncontrolled pro-inflammatory host-responses. Normal barrier functions include immune and physical factors such as secretory immunoglobulin A (SIgA) and the expression of tight junction proteins (blue bars) that restrict mucosal access of both dietary and microbial antigens. The main antigen-sampling dendritic cells (DCs) are CD103+CD11b− DCs that express retinal dehydrogenase 2 (RALDH2) and produce retinoic acid (RA) and that migrate to the mesenteric lymph nodes to promote the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into peripherally derived forkhead box protein P3 (FOXP3)+ regulator T (Treg) cells (pTreg cells) via a transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ)-dependent and RA-dependent mechanism. In the lamina propria, tolerogenic pTreg cells suppress the inflammatory T cell response and mediate oral tolerance. Enteric pathogenic infections and dysbiosis can alter IEC barrier disruption, leading to uncontrolled translocation of dietary antigens, certain pathogens and pathogen-associated molecular patterns into the intestinal mucosa. Coeliac disease is characterized by a T helper 1 (TH1) cell response to gluten that leads to IEC destruction and villous atrophy. TH1 cell responses in coeliac disease are linked to the differentiation of IL-12-producing and possibly IL-27-producing DCs. Most patients with coeliac disease display upregulation of pro-inflammatory IL-15, which can synergize with RA to induce DCs and promote TH1 cell responses that then instruct plasma cells to produce anti-gluten and anti-transglutaminase 2 (TGase2) antibodies. Type 1 strain Lang (T1L) reovirus infection induces pro-inflammatory CD103+CD11b− DCs that produce IL-12 via interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) and block the differentiation of pTreg cells. Food allergy is mediated by TH2 cell responses to dietary antigens. IECs that produce thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and IL-33, and tuft cells that produce IL-25, could contribute to food allergy by promoting differentiation of small intestinal CD103+CD11b+ DCs. Together with IgE-producing plasma cells, IL-4-producing basophils and the IgE-mediated degranulation of mast cells, these processes drive TH2 cell immunity and consequently food allergy to dietary antigens. Microbial infections inducing IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 could also contribute to promoting TH2 cell responses to dietary antigens; however, the mechanisms remain to be defined. IL-13R, IL-13 receptor; IL-25R, IL-25 receptor (also known as IL-17RB); IL-33R, IL-33 receptor (also known as IL-1RL1); IL-4R, IL-4 receptor; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; TSLPR, TSLP protein receptor (also known as CRLF2).

Intestinal inflammation abrogates the ability of CD103+ DCs to promote pTreg cell differentiation168, and under tissue distress, such as dermal parasitic Leishmania major infection, the CD103+CD11b− DC subset was shown to produce IL-12 and to drive TH1 cell immunity in mice166. Similarly, fungal infection with Encephalitozoon cuniculi induced a pro-inflammatory programme in lamina propria-residing, IL-12-producing CD103+CD11b−CD8+ DCs in mice169. This finding is in accordance with a study showing that enteric type 1 strain Lang (T1L) reovirus infection5 induced pro-inflammatory IL-12 production by mucosal CD103+CD11b− DCs, which drove TH1 cell responses to the dietary antigen gluten in an IRF1-dependent manner in animal models. Interestingly, this study also suggests that whereas IRF1 is required to induce TH1 cell responses to dietary antigens, it is not required for blocking the pTreg cell induction that requires type I interferon.

Reovirus-mediated inflammatory T helper 1 cell response to dietary antigens.

Some of the hypotheses of an infectious aetiology of coeliac disease include a reovirus-triggered induction of pro-inflammatory type I interferon83,170 or virus-mediated upregulation and release of the enzyme tissue transglutaminase171. In a 2017 study5, these associations were moved towards causality, and as a consequence of virus–host interactions, the pTreg cell response was abrogated, and a pathogenic TH1 cell response to gluten was induced instead. Importantly, two reovirus strains belonging to the same family of Reoviridae had different capacities to induce LOT, suggesting that particular viral genes interacting with the host can induce signalling pathways that lead to LOT. Intriguingly, other findings (B.J., unpublished observations) suggest that certain viruses, other than reovirus, can also induce LOT through manipulation of tolerogenic DCs presenting dietary antigens. These findings suggest that studying the viral genes that correlate with LOT by generating viral reassortants or mutants will help to understand the underlying mechanisms and to target specific pathways. Mechanistically, T1L reovirus induced LOT by blocking pTreg cell induction through type I interferon-mediated pathways. By contrast, TH1 cell induction in response to oral antigen was independent of type I interferon but required the transcription factor IRF1 in the CD103+CD11b− DCs that present oral antigen and produce IL-12 upon T1L reovirus infection. Furthermore, patients with coeliac disease had substantially higher anti-reovirus antibody titres than patients without coeliac disease, and intestinal mucosal IRF1 expression levels of patients with coeliac disease were associated with anti-reovirus antibody titres5, suggesting that antecedent virus–host interactions can initiate long-lasting changes in immune homeostasis associated with high mucosal IRF1 expression.

Future studies need to elucidate whether other enteropathogens, besides T1L reovirus, can induce a pro-inflammatory programme in CD103+CD11b− DCs, thereby suppressing a tolerogenic pTreg cell response and instead driving a TH1 cell response that leads to LOT to food antigens5 and whether this process could have important implications in other food sensitivities172.

The role of IL-15 in T helper 1 cell induction.

Another pathway that can be induced by microbial triggers and lead to LOT involves IL-15 upregulation. This cytokine was shown to induce LOT106,173 and to be upregulated upon stimulation with lipopolysaccharide or double-stranded RNA174. Interestingly, IL-15 is not implicated in reovirus-mediated LOT5, suggesting that it can constitute an independent inflammatory pathway leading to LOT. More specifically, IL-15 was shown in mice to endow RA with adjuvant properties and induce the differentiation of intestinal CD103+ DCs with a pro-inflammatory phenotype that produce high levels of IL-12 (REF.106). Consequently, upregulation of IL-15 in the lamina propria blocks pTreg cell differentiation and induces TH1 cell responses to dietary antigens106,173. These findings are relevant to coeliac disease173, in which polymorphisms in the gene encoding IL-12 are suggested to be a genetic risk factor175–177 and in which IL-15 upregulation in the lamina propria178–180 is associated with an upregulation of IL-12 (REF.106) according to experimental evidence.

In summary, multiple factors have to be considered to define the exact underlying mechanisms of how enteric virus or bacterial infections affect CD103+CD11b− DCs, other DC subsets and mucosal myeloid cells, such as by altering the RALDH2 activity of CD103+CD11b− DCs, suppressing the tolerogenic programme or inducing a transcription factor that regulates the pro-inflammatory programme in these cells.

Mechanisms in T helper 2 cell-mediated food allergy.

The stimulation of IECs by pathogens (such as helminths) and PAMPs (such as bacterial TLR2 ligands) results in the production of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), IL-25 and IL-33, which consequently disrupts barrier integrity and leads to TH2 cell immunity181,182 (FIG. 3). A population of small intestinal CD103+CD11b+ DCs were shown to mediate mucosal TH2 cell responses against parasites in mice, and it was also shown that IRF4 is involved and dependent on the type of microbial trigger183. Indications exist that certain helminth infections such as those with Heligmosomoides polygyrus can suppress food allergy via a mechanism requiring IL-10 that in a dominant manner can suppress TH2 cell responses184,185; however, precise mechanisms are lacking. In general, the helminth-elicited TH2 cell response is characterized by high levels of systemic helminth-induced IgE and IgG1 (REF.186) and by the production of a series of inflammatory mediators, such as histamine and cytokines (including IL-4, IL-13, IL-6 and TNF), which are released from degranulating mast cells and can further impair intestinal barrier function139. Accordingly, Candida albicans colonization was shown to promote gastrointestinal permeation of oral antigens, which was in part mediated by mucosal infiltration and degranulation of mast cells in mice187. Future studies are required to clearly define the microbial-triggered TH2 cell immune response that leads to food allergy.

Conclusions

Development of immune tolerance to dietary antigens is key for homeostatic intestinal and systemic immune responses. Investigations on the role of microbial determinants in preventing or leading to hypersensitivity reactions to innocuous dietary antigens have been intensively performed during the past two decades. Depletion of protective bacterial strains from the gut microbiota with beneficial metabolic function or the presence of viral infections or bacterial opportunistic pathogens could affect the risk of developing food sensitivities through a variety of mechanisms. Genetic predisposition will probably influence the manner in which the host responds to these environmental pressures. The best understood mechanisms involve indirect effects by bacterial metabolites and modification of antigenicity of dietary substrates and direct host effects that impair Treg cell responses or imprint a pro-inflammatory programme in the host. Although there is currently great emphasis on dietary modulation of the gut microbiota to improve health, this area requires more mechanistic evidence (BOX 1). Deep knowledge of specific micro-organism–diet interactions and their underlying molecular pathways will be necessary to develop prevention and novel therapies to treat food sensitivities.

Box 1 |. Outstanding questions in food sensitivities

The identity of specific food triggers and the underlying mechanisms and biomarkers involved in the context of self-reported adverse food reactions in patients with functional gut disorders remain unclear.

It is unknown whether intestinal dysbiosis in patients with food sensitivity is the consequence of ongoing (food-induced) inflammation or a post-infectious adverse effect that has a causal role in the breakdown of tolerance to antigen or allergen.

It remains to be determined whether infections and increased gluten intake synergize to promote breakdown of tolerance to gluten in genetically susceptible people and whether there is a window of opportunity for this effect.

The mechanisms underlying the paradoxically protective effect of certain helminths in food allergy remain unclear.

Key points

The mechanisms underlying the expression of food sensitivities remain unclear; however, several studies demonstrate that gut microorganisms, along with other host predisposing factors, dictate the development of these conditions.

Gut microorganisms can degrade or modify immunogenic food antigens or allergens, increasing or reducing their immunogenicity.

Dietary food components that are insufficiently digested by host enzymes become bacterial substrates, leading to the production of metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids, which are involved in gut homeostasis.

One key factor in the development of food sensitivities is intestinal barrier dysfunction, which can be influenced by gut microorganisms and pathogens through different pathways.

Mucosal dendritic cells present dietary antigens to naive T helper cells, promoting their differentiation into peripheral T regulatory cells; virus-host interactions abrogate this response, inducing a pathogenic response to antigens.

Enteric parasites induce T helper 2 cell immunity and protect against food allergy; this contradiction is explained by the observation that parasites induce IL-10, which blocks type 2 immunity.

Acknowledgements

E.F.V. is funded by Canadian Institute of Health Research grant MOP#142773 and holds a Canada Research Chair in Microbiota, Inflammation and Nutrition. A.C. holds a fellowship award from the Farncombe Family. M.M. was awarded a Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America Research fellowship award (ID: 480735). B.J. is funded by grants R01DK098435, R01DK100619 and R01DK067180 and by Digestive Diseases Research Core Center grant P30 DK42086. The authors thank R. Hinterleitner for critically editing the Review.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Reviewer information

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology thanks M. D. Kulis, H. Sampson and H. Tlaskalova-Hogenova for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

References

- 1.Turnbull JL, Adams HN & Gorard DA Review article: the diagnosis and management of food allergy and food intolerances. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 41, 3–25 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubio-Tapia A. et al. Increased prevalence and mortality in undiagnosed celiac disease. Gastroenterology 137, 88–93 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang ML & Mullins RJ Food allergy: is prevalence increasing? Internal Med. J. 47, 256–261 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verdu EF, Galipeau HJ & Jabri B. Novel players in coeliac disease pathogenesis: role of the gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 497–506 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouziat R. et al. Reovirus infection triggers inflammatory responses to dietary antigens and development of celiac disease. Science 356, 44–50 (2017). This study provides support for the concept that viruses can disrupt intestinal immune homeostasis and initiate loss of oral tolerance and T helper 1 cell immunity to dietary antigen. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caminero A. et al. Duodenal bacteria from patients with celiac disease and healthy subjects distinctly affect gluten breakdown and immunogenicity. Gastroenterology 151, 670–683 (2016). This study shows that the intestinal microbiota has a dual effect in gluten metabolism in vivo, increasing or reducing gluten immunogenicity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith PM et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science 341, 569–573 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarville JL, Caminero A. & Verdu EF Novel perspectives on therapeutic modulation of the gut microbiota. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 9, 580–593 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lomer MC, Parkes GC & Sanderson JD Review article: lactose intolerance in clinical practice — myths and realities. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 27, 93–103 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saito YA, Locke GR 3rd, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR & Talley NJ Diet and functional gastrointestinal disorders: a population-based case-control study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100, 2743–2748 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moayyedi P. et al. The effect of dietary intervention on irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Clin. Transl Gastroenterol. 6, e107 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shepherd SJ, Parker FC, Muir JG & Gibson PR Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6, 765–771 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teufel M. et al. Psychological burden of food allergy. World J. Gastroenterol. 13, 3456–3465 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sicherer SH Food allergy. Lancet 360, 701–710 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morita H, Nomura I, Matsuda A, Saito H. & Matsumoto K. Gastrointestinal food allergy in infants. Allergol Int. 62, 297–307 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sicherer SH & Sampson HA Food allergy: recent advances in pathophysiology and treatment. Annu. Rev. Med. 60, 261–277 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sampson HA & Anderson JA Summary and recommendations: classification of gastrointestinal manifestations due to immunologic reactions to foods in infants and young children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 30, S87–S94 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ludvigsson JF et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut 62, 43–52 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuppan D, Pickert G, Ashfaq-Khan M. & Zevallos V. Non-celiac wheat sensitivity: differential diagnosis, triggers and implications. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 29, 469–476 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DiGiacomo DV, Tennyson CA, Green PH & Demmer RT Prevalence of gluten-free diet adherence among individuals without celiac disease in the USA: results from the Continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2010. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 48, 921–925 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aziz I. et al. A UK study assessing the population prevalence of self-reported gluten sensitivity and referral characteristics to secondary care. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 26, 33–39 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaukinen K. et al. Intolerance to cereals is not specific for coeliac disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 35, 942–946 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanpowpong P. et al. Coeliac disease and gluten avoidance in New Zealand children. Arch. Dis. Childhood 97, 12–16 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lebwohl B, Ludvigsson JF & Green PH Celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. BMJ 351, h4347 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verbeke K. Nonceliac gluten sensitivity: what is the culprit? Gastroenterology 154, 471–473 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skodje GI et al. Fructan, rather than gluten, induces symptoms in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Gastroenterology 154, 529–539 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Junker Y. et al. Wheat amylase trypsin inhibitors drive intestinal inflammation via activation of toll-like receptor 4. J. Exp. Med. 209, 2395–2408 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zevallos VF et al. Nutritional wheat amylase-trypsin inhibitors promote intestinal inflammation via activation of myeloid cells. Gastroenterology 152, 1100–1113 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prescott SL et al. A global survey of changing patterns of food allergy burden in children. World Allergy Organiz. J. 6, 21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osborne NJ et al. Prevalence of challenge-proven IgE-mediated food allergy using population-based sampling and predetermined challenge criteria in infants. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 127, 668–676 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J. & Sampson HA Food allergy. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 827–835 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh P. et al. Global prevalence of celiac disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 823–836.e2 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pozo-Rubio T. et al. Influence of breastfeeding versus formula feeding on lymphocyte subsets in infants at risk of coeliac disease: the PROFICEL study. Eur. J. Nutr. 52, 637–646 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kemppainen KM et al. Factors that increase risk of celiac disease autoimmunity after a gastrointestinal infection in early life. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 694–702 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szajewska H. et al. Gluten introduction and the risk of coeliac disease: a position paper by the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 62, 507–513 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Decker E. et al. Cesarean delivery is associated with celiac disease but not inflammatory bowel disease in children. Pediatrics 125, e1433–1440 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marild K. et al. Antibiotic exposure and the development of coeliac disease: a nationwide case-control study. BMC Gastroenterol. 13, 109 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bashir ME, Louie S, Shi HN & Nagler-Anderson C. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling by intestinal microbes influences susceptibility to food allergy. J. Immunol. 172, 6978–6987 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crespo-Escobar P. et al. The role of gluten consumption at an early age in celiac disease development: a further analysis of the prospective PreventCD cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 105, 890–896 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uusitalo U. et al. Gluten consumption during late pregnancy and risk of celiac disease in the offspring: the TEDDY birth cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 102, 1216–1221 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stene LC et al. Rotavirus infection frequency and risk of celiac disease autoimmunity in early childhood: a longitudinal study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 101, 2333–2340 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marild K, Kahrs CR, Tapia G, Stene LC & Stordal K. Infections and risk of celiac disease in childhood: a prospective nationwide cohort study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 110, 1475–1484 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plot L. & Amital H. Infectious associations of Celiac disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 8, 316–319 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheung DS & Grayson MH Role of viruses in the development of atopic disease in pediatric patients. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 12, 613–620 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verdu EF, Mauro M, Bourgeois J. & Armstrong D. Clinical onset of celiac disease after an episode of Campylobacter jejuni enteritis. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 21, 453–455 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kagnoff MF, Austin RK, Hubert JJ, Bernardin JE & Kasarda DD Possible role for a human adenovirus in the pathogenesis of celiac disease. J. Exp. Med. 160, 1544–1557 (1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abadie V, Sollid LM, Barreiro LB & Jabri B. Integration of genetic and immunological insights into a model of celiac disease pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 29, 493–525 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi HN, Liu HY & Nagler-Anderson C. Enteric infection acts as an adjuvant for the response to a model food antigen. J. Immunol. 165, 6174–6182 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Honeyman MC et al. Association between rotavirus infection and pancreatic islet autoimmunity in children at risk of developing type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 49, 1319–1324 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silvester JA & Leffler DA Is autoimmunity infectious? The effect of gastrointestinal viral infections and vaccination on risk of celiac disease autoimmunity. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 703–705 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vaarala O, Jokinen J, Lahdenkari M. & Leino T. Rotavirus vaccination and the risk of celiac disease or type 1 diabetes in Finnish children at early life. Pediatr. Infecti. Dis. J. 36, 674–675 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karhus LL et al. Influenza and risk of later celiac disease: a cohort study of 2.6 million people. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 53, 15–23 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garg A, Reddy C, Duseja A, Chawla Y. & Dhiman RK Association between celiac disease and chronic hepatitis c virus infection. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 1, 41–44 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nadal I, Donat E, Ribes-Koninckx C, Calabuig M. & Sanz Y. Imbalance in the composition of the duodenal microbiota of children with coeliac disease. J. Med. Microbiol. 56, 1669–1674 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Collado MC, Donat E, Ribes-Koninckx C, Calabuig M. & Sanz Y. Imbalances in faecal and duodenal Bifidobacterium species composition in active and non-active coeliac disease. BMC Microbiol. 8, 232 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nistal E. et al. Differences of small intestinal bacteria populations in adults and children with/without celiac disease: effect of age, gluten diet, and disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 18, 649–656 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nistal E. et al. Differences in faecal bacteria populations and faecal bacteria metabolism in healthy adults and celiac disease patients. Biochimie 94, 1724–1729 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wacklin P. et al. Altered duodenal microbiota composition in celiac disease patients suffering from persistent symptoms on a long-term gluten-free diet. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 109, 1933–1941 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.D’Argenio V. et al. Metagenomics reveals dysbiosis and a potentially pathogenic N. flavescens strain in duodenum of adult celiac patients. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 111, 879–890 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Azad MB et al. Infant gut microbiota and food sensitization: associations in the first year of life. Clin. Exp. Allergy 45, 632–643 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abrahamsson TR et al. Low diversity of the gut microbiota in infants with atopic eczema. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 129, 434–440 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hua X, Goedert JJ, Pu A, Yu G. & Shi J. Allergy associations with the adult fecal microbiota: analysis of the American Gut Project. EBioMedicine 3, 172–179 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sanz Y, De Pama G. & Laparra M. Unraveling the ties between celiac disease and intestinal microbiota. Int. Rev. Immunol. 30, 207–218 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Palma GD et al. Influence of milk-feeding type and genetic risk of developing coeliac disease on intestinal microbiota of infants: the PROFICEL study. PLoS ONE 7, e30791 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bunyavanich S. et al. Early-life gut microbiome composition and milk allergy resolution. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 138, 1122–1130 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ling Z. et al. Altered fecal microbiota composition associated with food allergy in infants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 2546–2554 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Collado MC, Donat E, Ribes-Koninckx C, Calabuig M. & Sanz Y. Specific duodenal and faecal bacterial groups associated with paediatric coeliac disease. J. Clin. Pathol. 62, 264–269 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Galipeau HJ et al. Intestinal microbiota modulates gluten-induced immunopathology in humanized mice. Am. J. Pathol. 185, 2969–2982 (2015). This study shows that the intestinal microbiota can both positively and negatively modulate gluten-induced immunopathology in mice. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cahenzli J, Koller Y, Wyss M, Geuking MB & McCoy KD Intestinal microbial diversity during early-life colonization shapes long-term IgE levels. Cell Host Microbe 14, 559–570 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Noval Rivas M. et al. A microbiota signature associated with experimental food allergy promotes allergic sensitization and anaphylaxis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 131, 201–212 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Atarashi K. et al. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature 500, 232–236 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stefka AT et al. Commensal bacteria protect against food allergen sensitization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 13145–13150 (2014). In this study, selective colonization of gnotobiotic mice is used to demonstrate that the allergy-protective capacity is contained within the Clostridia class. Clostridia members induce IL-22 production, reducing uptake of orally administered dietary antigen into the systemic circulation and contributing to protection against food sensitization. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Atarashi K. et al. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science 331, 337–341 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu GD et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 334, 105–108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.David LA et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505, 559–563 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee D. et al. Diet in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 148, 1087–1106 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sonnenburg JL & Backhed F. Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature 535, 56–64 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gourbeyre P. et al. Perinatal and postweaning exposure to galactooligosaccharides/inulin prebiotics induced biomarkers linked to tolerance mechanism in a mouse model of strong allergic sensitization. J. Agric. Food Chem. 61, 6311–6320 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kunisawa J. et al. Dietary omega3 fatty acid exerts anti-allergic effect through the conversion to 17,18-epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid in the gut. Sci. Rep. 5, 9750 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hamer HM et al. Review article: the role of butyrate on colonic function. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 27, 104–119 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Koppel N, Maini Rekdal V. & Balskus EP Chemical transformation of xenobiotics by the human gut microbiota. Science 356, eaag2770 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shan L. et al. Structural basis for gluten intolerance in celiac sprue. Science 297, 2275–2279 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sollid LM & Jabri B. Triggers and drivers of autoimmunity: lessons from coeliac disease. Nat. Rev. Immunology 13, 294–302 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Caminero A. et al. Diversity of the cultivable human gut microbiome involved in gluten metabolism: isolation of microorganisms with potential interest for coeliac disease. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 88, 309–319 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Caminero A. et al. Differences in gluten metabolism among healthy volunteers, coeliac disease patients and first-degree relatives. Br. J. Nutr. 114, 1157–1167 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Herran AR et al. Gluten-degrading bacteria are present in the human small intestine of healthy volunteers and celiac patients. Res. Microbiol. 168, 673–684 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Helmerhorst EJ, Zamakhchari M, Schuppan D. & Oppenheim FG Discovery of a novel and rich source of gluten-degrading microbial enzymes in the oral cavity. PLoS ONE 5, e13264 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fernandez-Feo M. et al. The cultivable human oral gluten-degrading microbiome and its potential implications in coeliac disease and gluten sensitivity. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 19, E386–E394 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nistal E. et al. Study of duodenal bacterial communities by 16s rrna gene analysis in adults with active celiac disease versus non celiac disease controls. J. Appl. Microbiol. 120, 1691–1700 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Borton MA et al. Chemical and pathogen-induced inflammation disrupt the murine intestinal microbiome. Microbiome 5, 47 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dieterich W. et al. Identification of tissue transglutaminase as the autoantigen of celiac disease. Nat. Med. 3, 797–801 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhou L. et al. Abrogation of immunogenic properties of gliadin peptides through transamidation by microbial transglutaminase is acyl-acceptor dependent. J. Agric. Food Chem. 65, 7542–7552 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Toomer OT, Do A, Pereira M. & Williams K. Effect of simulated gastric and intestinal digestion on temporal stability and immunoreactivity of peanut, almond, and pine nut protein allergens. J. Agric. Food Chem. 61, 5903–5913 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tye-Din JA et al. Comprehensive, quantitative mapping of T cell epitopes in gluten in celiac disease. Sci. Transl Med. 2, 41ra51 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Maynard CL, Elson CO, Hatton RD & Weaver CT Reciprocal interactions of the intestinal microbiota and immune system. Nature 489, 231–241 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Morrison DJ & Preston T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes 7, 189–200 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lamas B. et al. CARD9 impacts colitis by altering gut microbiota metabolism of tryptophan into aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands. Nat. Med. 22, 598–605 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tjellstrom B. et al. Gut microflora associated characteristics in children with celiac disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100, 2784–2788 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Brestoff JR & Artis D. Commensal bacteria at the interface of host metabolism and the immune system. Nature Immunol. 14, 676–684 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Arpaia N. et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T cell generation. Nature 504, 451–455 (2013). This study shows that bacterial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids mediate communication between the commensal microbiota and the immune system, affecting the balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mechanisms. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Furusawa Y. et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 504, 446–450 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hadis U. et al. Intestinal tolerance requires gut homing and expansion of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in the lamina propria. Immunity 34, 237–246 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bilate AM & Lafaille JJ Induced CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in immune tolerance. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 30, 733–758 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tan J. et al. Dietary fiber and bacterial SCFA enhance oral tolerance and protect against food allergy through diverse cellular pathways. Cell Rep. 15, 2809–2824 (2016). This study finds that dietary elements, including fibre and vitamin A, are essential for the tolerogenic function of CD103+ dendritic cells and the maintenance of mucosal homeostasis, including proper IgA responses and epithelial barrier function. The practical outcome of this study is the promotion of oral tolerance and protection from food allergy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fukuda S. et al. Bifidobacteria can protect from enteropathogenic infection through production of acetate. Nature 469, 543–547 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.DePaolo RW et al. Co-adjuvant effects of retinoic acid and IL-15 induce inflammatory immunity to dietary antigens. Nature 471, 220–224 (2011). This study finds that, in conjunction with IL-15, retinoic acid rapidly activates dendritic cells to release pro-inflammatory cytokines, and as a result, in a stressed intestinal environment, retinoic acid acts as an adjuvant that promotes rather than prevents inflammatory cellular and humoral responses to fed antigens. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Meisel M. et al. Interleukin-15 promotes intestinal dysbiosis with butyrate deficiency associated with increased susceptibility to colitis. ISME J. 11, 15–30 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Berni Canani R. et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG-supplemented formula expands butyrate-producing bacterial strains in food allergic infants. ISME J. 10, 742–750 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zelante T. et al. Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity 39, 372–385 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nguyen NT et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor negatively regulates dendritic cell immunogenicity via a kynurenine-dependent mechanism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 19961–19966 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Schulz VJ et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation affects the dendritic cell phenotype and function during allergic sensitization. Immunobiology 218, 1055–1062 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hammerschmidt-Kamper C. et al. Indole-3-carbinol, a plant nutrient and AhR-Ligand precursor, supports oral tolerance against OVA and improves peanut allergy symptoms in mice. PLoS ONE 12, e0180321 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schulz VJ, Smit JJ & Pieters RH The aryl hydrocarbon receptor and food allergy. Vet. Q. 33, 94–107 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mazmanian SK, Round JL & Kasper DL A microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestinal inflammatory disease. Nature 453, 620–625 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Atarashi K. & Honda K. Microbiota in autoimmunity and tolerance. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 23, 761–768 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Round JL & Mazmanian SK Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 12204–12209 (2010). Here, the immunomodulatory molecule polysaccharide A of Bacteroides fragilis is shown to mediate the conversion of CD4+ T cells into FOXP3+ regulatory T cells that produce IL-10 during commensal colonization. B. fragilis co-opts the regulatory T cell lineage differentiation pathway in the gut to actively induce mucosal tolerance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cerf-Bensussan N. & Gaboriau-Routhiau V. The immune system and the gut microbiota: friends or foes? Nat. Rev Immunology 10, 735–744 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hrncir T, Stepankova R, Kozakova H, Hudcovic T. & Tlaskalova-Hogenova H. Gut microbiota and lipopolysaccharide content of the diet influence development of regulatory T cells: studies in germ-free mice. BMC Immunol. 9, 65 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schwarzer M. et al. Diet matters: endotoxin in the diet impacts the level of allergic sensitization in germ-free mice. PLoS ONE 12, e0167786 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Olivares M, Castillejo G, Varea V. & Sanz Y. Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled intervention trial to evaluate the effects of Bifidobacterium longum CECT 7347 in children with newly diagnosed coeliac disease. Br. J. Nutr. 112, 30–40 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Pinto-Sanchez MI et al. Bifidobacterium infantis NLS super strain reduces the expression of α-defensin-5, a marker of innate immunity, in the mucosa of active celiac disease patients. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 51, 814–817 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Enomoto T. et al. Effects of bifidobacterial supplementation to pregnant women and infants in the prevention of allergy development in infants and on fecal microbiota. Allergol. Int. 63, 575–585 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hill DA et al. Commensal bacteria-derived signals regulate basophil hematopoiesis and allergic inflammation. Nat. Med. 18, 538–546 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.De Angelis M. et al. VSL#3 probiotic preparation has the capacity to hydrolyze gliadin polypeptides responsible for celiac sprue. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1762, 80–93 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Schiavi E. et al. Oral therapeutic administration of a probiotic mixture suppresses established Th2 responses and systemic anaphylaxis in a murine model of food allergy. Allergy 66, 499–508 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Barletta B. et al. Probiotic VSL#3-induced TGF-β ameliorates food allergy inflammation in a mouse model of peanut sensitization through the induction of regulatory T cells in the gut mucosa. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 57, 2233–2244 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.McCarville JL et al. A commensal Bifidobacterium longum strain improves gluten-related immunopathology in mice through expression of a serine protease inhibitor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 10.1128/AEM.01323-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Galipeau HJ et al. Novel role of the serine protease inhibitor elafin in gluten-related disorders. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 109, 748–756 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kim JH et al. Extracellular vesicle-derived protein from Bifidobacterium longum alleviates food allergy through mast cell suppression. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 137, 507–516 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Tang ML et al. Administration of a probiotic with peanut oral immunotherapy: a randomized trial. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 135, 737–744 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wood RA et al. A phase 1 study of heat/phenol-killed, E. coli-encapsulated, recombinant modified peanut proteins Ara h 1, Ara h 2, and Ara h 3 (EMP-123) for the treatment of peanut allergy. Allergy 68, 803–808 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Pabst O. & Mowat AM Oral tolerance to food protein. Mucosal Immunol. 5, 232–239 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Faria AM & Weiner HL Oral tolerance. Immunol. Rev. 206, 232–259 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Fasano A. & Shea-Donohue T. Mechanisms of disease: the role of intestinal barrier function in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal autoimmune diseases. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2, 416–422 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Menard S, Cerf-Bensussan N. & Heyman M. Multiple facets of intestinal permeability and epithelial handling of dietary antigens. Mucosal Immunol. 3, 247–259 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Berin MC & Sampson HA Mucosal immunology of food allergy. Curr. Biol. 23, R389–R400 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Koning F, Schuppan D, Cerf-Bensussan N. & Sollid LM Pathomechanisms in celiac disease. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 19, 373–387 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Vogelsang H, Schwarzenhofer M. & Oberhuber G. Changes in gastrointestinal permeability in celiac disease. Dig. Dis. 16, 333–336 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Perrier C. & Corthesy B. Gut permeability and food allergies. Clin. Exp. Allergy 41, 20–28 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Amieva MR et al. Disruption of the epithelial apical-junctional complex by Helicobacter pylori CagA. Science 300, 1430–1434 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Wu Z, Nybom P. & Magnusson KE Distinct effects of Vibrio cholerae haemagglutinin/protease on the structure and localization of the tight junction-associated proteins occludin and ZO-1. Cell. Microbiol. 2, 11–17 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Maharshak N. et al. Enterococcus faecalis gelatinase mediates intestinal permeability via protease-activated receptor 2. Infection Immun. 83, 2762–2770 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]