Abstract

Objective

PCSK9 enhances the degradation of the LDLR in endosomes/lysosomes. This study aimed to determine the sites of PCSK9 phosphorylation at Ser-residues and the consequences of such post-translational modification on the secretion and activity of PCSK9 on the LDLR.

Approach and Results

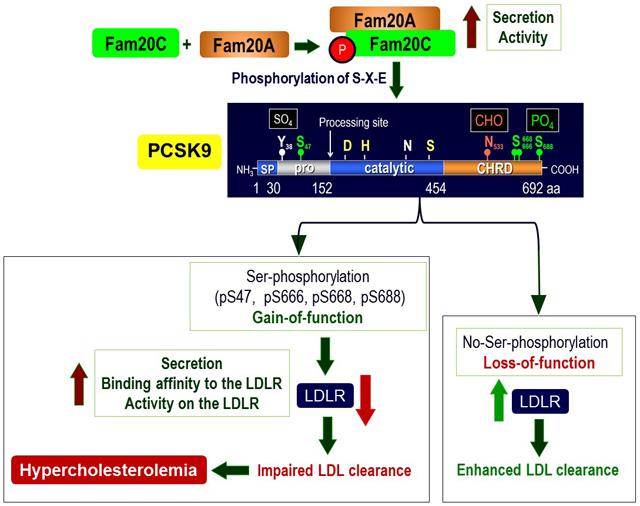

Fam20C phosphorylates serines in secretory proteins containing the motif S-X-E/phospho-Ser, including the cholesterol-regulating PCSK9. In situ hybridization of Fam20C mRNA during development and in adult mice revealed a wide tissue distribution including liver, but not small intestine. Herein, we show that Fam20C phosphorylates PCSK9 at Serines 47, 666, 668 and 688. In hepatocytes, phosphorylation enhances PCSK9 secretion and maximizes its induced degradation of the LDLR via the extracellular and intracellular pathways. Replacing any of the four Ser by the phosphomimetic Glu or Asp enhanced PCSK9 activity only when the other sites are phosphorylated, whereas Ala substitutions reduced it, as evidenced by Western blotting, Elisa and LDLR-immunolabeling. This newly uncovered PCSK9/LDLR regulation mechanism refines our understanding of the implication of global PCSK9-phosphorylation in the modulation of LDL-cholesterol, and rationalizes the consequence of natural mutations, e.g., S668R and E670G. Finally, the relationship of Ser-phosphorylation to the implication of PCSK9 in regulating LDL-cholesterol in the neurological Fragile X-syndrome disorder was investigated.

Conclusion

Ser-phosphorylation of PCSK9 maximizes both its secretion and activity on the LDLR. Mass spectrometric approaches to measure such modifications were developed and applied to quantify the levels of bioactive PCSK9 in human plasma under normal and pathological conditions.

Keywords: PCSK9, LDLR degradation, LDL-cholesterol, Fam20C kinase, pseudokinase Fam20A, Ser-phosphorylation, natural mutations, PCSK9 E670G, mass spectral analysis, Fragile X syndrome

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is a dominant genetic disease caused by excess circulating low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDLc).1 Natural mutations in three main genes affect the levels/activity of the LDL-receptor (LDLR), which in liver is responsible for the clearance of LDLc.2 Loss-of-function (LOF) mutations in the LDLR, or its ligand apolipoprotein B (ApoB, main protein of LDL) are associated with high levels of LDLc. Together, mutations in these two genes represent ~80% of all mutations that regulate LDLc. In 2003, a new gene, proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin-9 (PCSK9), was discovered,3 and its relation to LDLc regulation was deduced from specific gain-of-function (GOF) natural mutations.4 Following its autocatalytic processing in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) the secreted mature protein, composed of a prodomain non-covalently linked to the catalytic subunit,3, 5 was shown to increase the levels of LDLc, through its ability to bind to the EGF-A domain of the LDLR,6-8 and in a non-enzymatic fashion to enhance LDLR degradation in endosomes/lysosomes.9, 10 This occurs predominantly via an “extracellular” pathway involving secreted PCSK9 from hepatocytes,11 but also by an “intracellular” route.12 GOF and LOF mutations of PCSK9 are associated with hypercholesterolemia and hypocholesterolemia, respectively.13-15

Interestingly, while in cell lines both extracellular and intracellular activities of PCSK9 can be readily measured,12, 16 in hepatocytes it is predominantly the secreted PCSK9 that regulates LDLR levels.9, 13 In situ hybridization histochemistry (IHyH) of mRNA expression revealed that adult PCSK9 is highly expressed in liver hepatocytes, but also to a lesser extent in the small intestine, pancreas, kidney and brain cerebellum (Figure 1).3, 17 The role and regulation of PCSK9 in extrahepatic tissues is far from understood,13, 18 and it may be critical for the transintestinal cholesterol excretion.19 However, we showed that PCSK9 is not significantly secreted from intestinal cells based on the fact that no circulating PCSK9 was detected in liver-specific PCSK9 knockout (Pcsk9−/−) mice.17 This suggested that the function of PCSK9 in the small intestine, and possibly other extrahepatic tissues such as pancreatic β-cells,3, 20 is likely to be predominantly autocrine/paracrine and/or intracellular.

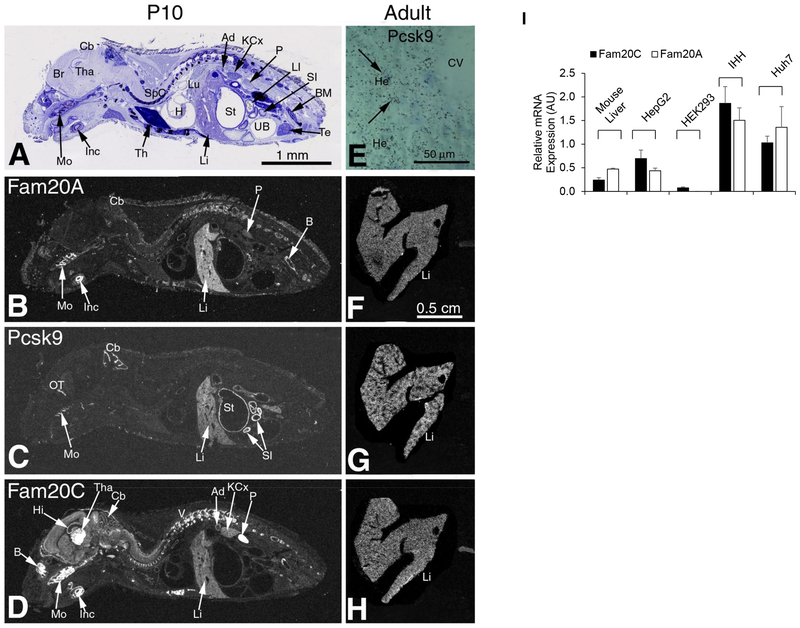

Figure 1.

Comparative mRNA distribution of mouse Fam20A, Pcsk9 and Fam20C.

Sections of whole body P10 WT mouse were subjected to IHyH using mFam20A, mPsck9, and mFam20C cRNA probes.

(A) Representative sagittal cryostat sections of P10 mouse with thionin staining. (B-D) X-ray film autoradiography showing:

(B) Fam20A mRNA distribution pattern restricted to few tissues including the molar, incisor, cerebellum, liver, kidney papilla and bone;

(C) Pcsk9 mRNA distribution pattern restricted to the olfactory tract, molar, cerebellum, liver, stomach wall and small intestine wall;

(D) Fam20C mRNA widespread distribution pattern with high levels in bone, molars, incisive, brain with thalamic structures, hippocampus and cerebellum, liver, adrenal gland, kidney cortex and papilla.

Abbreviations: Ad – adrenal gland; B – bone; BM – bone marrow; Br – brain; Cb – cerebellum; H – heart; Hi – hippocampus; KCx – kidney cortex; Inc – incisive; Li – liver; LI – large intestine; Lu – lung; Mo – molar; OT – olfactory tract; P – papilla; SI – small intestine; SpC – spinal cord; St – stomach; Te – testis; Th – thymus; Tha – thalamus; UB – urinary bladder; V - vertebrae.

(E-H) Adult mouse liver IHyH. (E) High resolution hepatocyte staining, dry film lower resolution IHyH Fam20A (F), mPcsk9 (G) and mFam20C (H).

(I) QPCR analysis of mRNA distribution in adult liver mouse extracts and in indicated cell line models. QPCR was achieved using specific Fam20A and Fam20C primers. Data shown represent means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments.

Since the mechanism behind this seemingly tissue-specific function of intracellular versus extracellular PCSK9 is not clear, we postulated that this may be related to some differential post-translational modification(s) of PCSK9, such as Asn533-glycosylation,3 Tyr38-sulfation21 and/or Ser-phosphorylation (pS), e.g., at Ser4722 or Ser688.23, 24 While N-glycosylation or Tyr-sulfation of PCSK9 could affect its function on the LDLR, herein, we turned our attention to the regulation of the PCSK9 secretion and activity on the LDLR by Ser-phosphorylation.

First, based on the seminal work of Tagliabracci et al, it was clear that cells secrete only a single Ser-kinase known as Fam20C as a homodimer or in complex with a non-enzymatically active pseudo-kinase partner Fam20A.25, 26 Interestingly, hetero-dimerization of Fam20C with Fam20A26 most effectively enhances the activity27 and secretion28 of Fam20C. The available data revealed that in cells Fam20C phosphorylates PCSK9,25 but only Ser47 and Ser688 were identified. It was therefore logical to test the effect of co-expression of Fam20C and Fam20A with PCSK9, their kinase activity on PCSK9, and their effect on its secretion and function. We also defined the importance of such modification at each of the five predicted Ser-phosphorylation sites of human PCSK9 that exhibit the Fam20C consensus motif S-X-E/pS, namely Ser47, Ser401, Ser666, Ser668 and Ser688.3

Fragile-X-syndrome (FXS) is a neurological disease in which patients have very low levels of circulating HDL and LDLc, which are critical for neuronal development.29 However, our group found no differences in total circulating PCSK9 levels, as measured by ELISA, between FXS patients and a control group and no correlation was found between LDLc levels and total plasma PCSK9 concentrations in FXS patients.30 In light of the GOF role of phosphorylation on PCSK9’s activity presented herein, we postulated that circulating PCSK9’s phosphorylation state would be decreased in FXS patients. In human subjects (without FXS), following a 1-year treatment with the cholesterol-lowering drug “Rosuvastatin” we observed a ~25% decreased phosphorylation of PCSK9 at Ser688.24 This may explain the paradoxical increase in PCSK9 and lack of correlation with LDLc observed after statin therapy.31, 32 In the present study, we obtained evidence by targeted quantitative mass spectrometry23, 24 that the phosphorylation state of PCSK9 at Ser688 is ~25% lower in FXS patients, and that the levels of phosphorylated PCSK9 (pPCSK9) at Ser688 and of its ratio to non-phosphorylated PCSK9 (npPCSK9) both significantly correlate with those of LDLc in FXS patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article [and its online supplementary files].

PCSK9 Site-directed mutagenesis

Point mutations or deletion mutants of human PCSK9 were generated from pIRES2-EGFP-hPCSK9-WT (hPCSK9-WT) and pIRES2-EGFP-hPCSK9-WT-V5 (hPCSK9-WT-V5) constructs through a two-step PCR technique as previously described.3 The PCR primers are listed in Table S1. The following constructs used were described elsewhere: hPCSK9- D374Y-V5,21 hPCSK9-R46L-V5, hPCSK9-S47A-V5 and hPCSK9-S688A-V5,22 hPCSK9-(Δ33–58)-V533 and Furin (pIRES2-EGFP-hFurin-WT-V5).34 pCCF-Fam20C-WT-Flag, pCCF-Fam20CD478A-Flag, pCCF-Fam20A-WT-Flag, were kindly provided by Vincent S. Tagliabracci (University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas). pIRES2-EGFP-hLDLR-WT-V5 was used as described.16 All newly generated or received constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. pIRES2-EGFP and pIRES2-EGFP-V5 empty vectors were used as controls in cell transfections.

CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing of PCSK9 in HepG2 cells (CRISPR/cas9-PCSK9)

HepG2 cells were plated in 100 mm dishes at a density of 5×106 cells and grown in EMEM with 10% FBS. Cells were co-transfected with 8 μg of pCas-Guide vector and 8 μg of pUC-turboGFP-puro donor vector (Origene genome-wide gene knockout kit) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer protocol. The gRNA sequence (5′GGTGCTAGCCTTGCGTTCCG3′) targeted PCSK9 exon 1 sequence and the turboGFP-puro donor vector was flanked with a left and right 600 bp homologous arms to PCSK9 genomic sequence as listed in Table S2. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were split and allowed to grow for an additional three days with addition of 2 μg/mL puromycin. Then, cells were diluted and plated in 100 mm dishes for single clone selection. Stable cells were maintained in puromycin and allowed to grow for several days. Emerging colonies were manually picked and seeded in a 96-well plate, and scaled up to 6-well plate for genomic DNA editing validation. HepG2 clones and unedited HepG2 cells were lysed in 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 0.2% SDS and 0.1 mg/mL of freshly added proteinase K for two hours at 55°C. Genomic DNA was pelleted by addition of cold isopropanol and PCR was carried out on extracted gDNA. The PCR primer sequences used to validate the knockout of PCSK9 exon 1 sequence and the knock-in of turboGFP-puro are shown in Table S3: hPCSK9 forward, 5′-AGTGGAAAGAATTCGGTGGG-3′, and hPCSK9 reverse, 5′-TAGCACCAGCTCCTCGTAGT-3′ and human PCSK9 forward, and turboGFP-puro, 5′-AAGCTGCCATCCAGATCGTT-3′ respectively. Finally, RNA isolation was performed using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and QRT-PCR was carried out, as previously described35 on HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells to confirm the absence of PCSK9 mRNA (data not shown).

Cell culture and transfection

All cells were maintained at 37°C under 5%CO2. Naive HepG2, HepG2-Fam20C−/− (CRISPR/cas9-FAM20C25) and HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells were grown in EMEM medium (Wisent bioproducts) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, FBS (GIBCO BRL). They are transfected at 60–80% confluency using Fugene HD reagent (Promega) following the manufacturer’s instructions. HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Wisent bioproducts) with 10% FBS and transfected using jetPRIME (Polyplus) reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Furin-deficient Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO-FD11 Furin−/−) cells34 were grown in DMEM-F12 media (Wisent bioproducts) and transfected by Fugene HD reagent at 60–70% confluency. 24h post-transfection, the cells (all cell lines) were incubated in serum-free medium between 1–4h, then for another 18h. At the end, the media and cells were collected for analysis.

Primary hepatocytes from Pcsk9−/− mice

We only used livers of Pcsk9−/− male mice as males show the maximal effect of the absence of PCSK9 on cell surface LDLR.20 Mice were fed a normal standard diet (2018 Teklad global 18% protein rodent diet; Envigo) and housed in a 12h light/dark cycle. All procedures were approved by the bioethics committee for animal care of the Montreal Clinical Research Institute.

Primary hepatocytes were prepared from 8–12 week-old male Pcsk9−/− livers using a two-step collagenase perfusion method.36 After anesthesia of mice by 2% isofluran inhalation, the peritoneal cavity was opened, and the liver was perfused in situ via the inferior vena cava for 6 min at 37°C with calcium-free HEPES buffer I (142 mM NaCl, 6.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.6), and for 8 min with calcium-supplemented HEPES buffer II (4.7 mM CaCl2, 66.7 mM NaCl, 6.7 mM KCl, 100 mM Hepes, pH 7.4) containing 0.5 mg/ml collagenase Type V (Sigma Aldrich). The perfusion rates were set to 8 and 6 ml/min, respectively. In 3.5 cm Petri dishes coated with fibronectin (0.5 mg/ml, Sigma Aldrich), 5×105 cells were seeded in Williams’ medium E supplemented with 10% FBS. After 2h, the medium was replaced with hepatozyme medium (GIBCO BRL) for 12h prior to media swap analyses.

Western blotting

The cell media were recovered, centrifuged for 5 min (12,000 rpm/ 4°C), the supernatants collected to which were added 50 mM sodium fluoride (NaF) (BioShop) and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science). The cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS then harvested and lysed in in RIPA buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitor cocktail. The lysates were then centrifuged for 15 min (12,000 rpm/ 4°C), supernatants recovered and protein concentrations determined using the DC Protein assay (Bio-Rad). The lysates and media were then heated to 95°C in SDS sample buffer and equal protein amounts resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and analyzed by immunoblotting using the corresponding primary antibodies and later, secondary antibodies conjugated to HRP. The enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; BIO-RAD) was used to image the antigen-antibody complexes. The densitometry quantification was achieved using the ChemiDoc MP imaging system (Bio-Rad).

Conditioned media (CM) production for PCSK9-LDLR binding assay, media swap and mass spectrometry (MS)

To produce CM in non-phosphorylating conditions, the cells were transfected as described above with the constructs of interest (e.g. EV, PCSK9, etc.) in the presence only of Fam20A construct. For phosphorylating conditions, the cells were transfected with the constructs of interest (e.g. EV, PCSK9, etc.) and with both Fam20C/Fam20A constructs (DNA ratio: 1: 0.5/0.5, PCSK9: Fam20C/Fam20A) to ensure a maximum phosphorylation. After 48h the media were collected, centrifuged 5 min (12,000 rpm/ 4°C) and the supernatant hPCSK9 media were recovered and quantified by ELISA as previously described.37 All CM concentrations were adjusted to 300–500 ng/ml. The media then aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

Media swap

The cells were first incubated in serum-free media for 1h. Next the media were swapped to CM containing equal quantities of hPCSK9 (300–500 ng/ml) and the cells were incubated for another 18h before collecting them for analysis.

In situ hybridization

Glass slides containing fixed whole body P10, or adult liver tissues 10 μm-thick cryosections were hybridized with mouse antisense and sense (negative control) cRNA riboprobes as previously described.3 The [35S]-labeled (PerkinElmer) cRNA probes were synthesized in vitro and corresponded to mouse coding regions for residues 352–648, 1–249 and 259–510 of mouse Pcsk9, Fam20C and Fam20A respectively.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Q-RT-PCR was performed as previously described.38 The following primers (5′-˃3′) were used to measure mRNA levels: hFam20A (Forward: GGCATCATTGACATGGCCGTCTTT; Reverse: TTCATCCTGGGAATGTCGTCCGAA) hFam20C (Forward: TGAAGATGATACTGGTGCGCAGGT; Reverse: CAACAGCAATGTGCAAAGCGCAAG), mFam20A (Forward: TGGACCGGCACCATTATGAGATGT; Reverse: TTCATCATGGGAGTGTCGTCCGAA), mFam20C (Forward: CTCAGCTTGTACTCCTCCTTG; Reverse: AAGAGGGTTTGGGAAGTATTCG).

PCSK9 media de-phosphorylation

Lambda Protein Phosphatase (λPPase) (Cat # P0753S, N.E. BioLabs) was used to dephosphorylate serine residues of PCSK9 in the media according to the manufacturer′s protocol. Briefly, PCSK9 media were collected, added with protease inhibitor cocktail and their concentration measured by ELISA. Equal protein amounts were incubated with λPPase in supplied 1X NEB Buffer, supplemented with 1 mM MnCl2 for 1h at 30°C. The samples were then boiled in SDS sample buffer and analysed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Fam20C Kinase assays with PCSK9 peptide substrates

Recombinant human Fam20C (63-C) was purified from insect cells as described in Xiao et. al.39 β-casein and PCSK9 peptides were synthesized by GenScript. Peptide stocks were prepared in 10 mM HEPES and the pH was adjusted to 7.5 with NaOH. 25% DMSO was added to PCSK9_pSe47 and PCSK9 (R/L) pSer47 stocks for solubility. Kinase assays were performed essentially as described.40 Reactions (25 μL) contained 50 mM Tris HCl pH 7, 0.5 mg/mL BSA, 5 mM MnCl2, 100 μM [γ−32P] ATP (SA = 200 cpm/pmol), 0.5 mM peptide and 1 μg/mL Fam20C. Reactions were incubated at 30°C and terminated after 15 min by spotting 17.5 μL onto p81 cellulose chromatography papers (Whatman). Papers were washed three times in 0.85% o-phosphoric acid (10 min, 1h, and 10 min washes) followed by a 5 min wash in acetone. Dried papers were transferred to scintillation vials with Budget-Solve scintillation cocktail (RPI, 111167). Incorporated radioactivity was quantified by scintillation counting. Statistical analysis was performed in Prism 8 (Graphpad).

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy Analysis of Cell Surface LDLR Expression in HepG2 Cells

HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells were plated on poly-L-lysine coated coverslips. 24 h post-plating, cells were switched to a serum-free EMEM medium for 24 h. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and fixed with PBS, 4% paraformaldehyde (10 min). After blocking with PBS, 2% BSA (1h), samples were incubated at 4°C overnight with goat anti-human LDLR polyclonal antibody (1:200), washed with PBS, and incubated with anti-goat Alexa 488 secondary antibody for 1h at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted on a glass slide with ProLong-DAPI (Life technologies). Samples were visualized with a Plan-Apochromat 63 1.4 oil objective of an LSM-710 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss), using sequential excitation and capture image acquisition with a digital camera. Images were processed with ZEN software. Image analysis to quantify the fluorescence intensities was accomplished using Volocity (x64).

Dil-LDL (1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethyl-indocarbocyanine perchlorate) uptake assay

HepG2-Fam20C−/− cells were seeded in a 96-well plate CellBind (Corning; # 3340) at a density of 22,000 cells/well, in complete medium. After 24h, the complete medium was removed and replaced with serum-free culture medium (200 μl/well) and the cells returned to the incubator for another 24h. At forty eight hours post-seeding, the medium was removed and replaced with 100 μl/well of serum-free conditioned medium containing 300 ng/ml of the specified human PCSK9-V5 proteins in non-phosphorylated or phosphorylated conditions, or their respective controls (no PCSK9), and incubated for 20h at 37°C. Each condition was prepared in 4 replicates. During the last 3h of incubation, Dil-LDL (Alfa Aesar) was added to the cell media (10 μl) at 6 μg/ml final concentration. After three washes with ice-cold PBS (Wisent) and aspiration of the final wash, cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde + 1 μg/ml Hoechst 33258 (100ul/well) for 20 min at room temperature. Following 3 washes with PBS and removal of the final wash, 100 μl of PBS was added to each well and the plate was scanned (bottom read) on a SpectraMax i3 plate reader (Molecular Devices). For each well, raw Dil-LDL uptake was measured as the average fluorescence intensity (excitation: 534 nm/ emission: 572 nm) of 21 points equally distributed in a fill pattern. Dil-LDL uptake in each well was corrected for total number of cells by measuring the total DNA in each well and reported as the fluorescence ratio of Dil-LDL/Hoechst 33258. In each well, the average fluorescence for Hoechst (DNA content) was measured at excitation/emission 346/460 nm of 12 points equally distributed in a fill pattern. Corrected Dil-LDL uptake is reported as % control and was averaged from four wells. Each experiment was performed three times.

PCSK9-LDLR binding affinity assay

The PCSK9-LDLR binding affinity was assessed by using a CircuLex human PCSK9 functional assay kit (MBL, Cat # CY8153) following the manufacturers’ instructions. Briefly, 8 serial dilutions of non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated PCSK9 CM (see Conditioned media production section) were first prepared in a pH 7.4 buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 1.5mM CaCl2), then added to microplates pre-coated with LDLR EGF-AB domain, containing the PCSK9 binding site, and subsequently incubated at 30ºC for 18h. The EC50 values were measured from the relative absorbance at 450 nm wavelength (SpectraMax i3) at each concentration.

FXS Study population

Human plasma samples were obtained from a case-control study designed to characterise the lipid profile of French-Canadian FXS individuals (PMC5363930). Briefly, 26 FXS individuals with a confirmed molecular diagnosis (Southern blot and polymerase chain reaction) and 25 healthy controls were recruited through the Fragile X Clinic (CIUSSS de l’Estrie-CHUS, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada). Participants treated with lipid lowering drugs or suffering from liver disease or malabsorption / malnutrition or other conditions that could influence the lipid profile were excluded. Fasting blood samples were obtained from all participants, centrifuged within one hour, separated and frozen immediately at - 80°C. Plasma were shipped on dry ice to IRCM for proteomics analyses. This study conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2000 and was approved by the IRCM and the CIUSSS de l’Estrie-CHUS Ethics Committees. All subjects gave written informed consent.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism using one-way or two-way ANOVA as appropriate, coupled to Tukey's multiple comparisons test to assess the significance of all data sets. The normality of distribution of the data was verified using the D’Agostino normality test. Data are presented as means +/− SEM and a p value of lower than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

For PCSK9 peptides MS quantitative analyses, raw mass spectrometric data was imported into and analyzed with Pinpoint 1.3.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptide abundances in each sample were calculated using the sum of the area of 4 most abundant precursor isotopes (MS1) per peptide and normalized against the sum of the area of 4 isotopes of the corresponding synthetic heavy isotope-labelled peptides (area ratio). Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism and the results are presented as mean ± SEM. The normality of distribution of the data was verified using the D’Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test. Statistical significance of continuous variables was determined by two-tailed unpaired T-Test for variables with normal data distribution and by two-tailed Mann-Whitney test for variables with non-normal data. Correlations were examined with Pearson r for variables with normal data distribution or Spearman r for non-normal data. Alpha was set at 0.05 and the resulting P values were adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure with a false discovery rate set at 0.05 41.

RESULTS

Comparative tissue mRNA expression of mouse PCSK9, Fam20C and Fam20A and co-localization in hepatocytes

Our first objective was to compare in developing and adult mice the expression of PCSK9 to that of the Fam20C kinase and its activating partner the pseudo-kinase Fam20A.25, 26 Accordingly, we used IHyH with specific 35S-cRNAs to probe the expression of the mRNAs coding for these proteins at postnatal day 10 (P10) and in adult mice, as we previously reported for many other transcripts.3, 13, 42 In Figures 1A-H, we show the results of IHyH on consecutive 10 μm thick sagittal cryostat sections of whole mouse body at P10, and in the adult. Based on thionin staining patterns (Figure 1A) and X-ray autoradiography, it became apparent that at P10 Fam20C is much more widely expressed than Fam20A. The expression of Fam20A seems to be restricted to a few tissues including the molar, incisor, cerebellum, liver, kidney papilla and bone (Figure 1B). In contrast, Fam20C exhibits a widespread distribution pattern with high levels in bone, molars, incisive, brain with thalamic structures, hippocampus and cerebellum, liver, adrenal gland, kidney cortex and papilla (Figure 1D). Thus, while some tissues express both Fam20C and Fam20A, e.g., liver and bone, many others only express Fam20C. These data are in agreement with the proposed hypothesis that the Fam20C homodimer (in tissues that do not express Fam20A; e.g., in brain thalamus and hippocampus) plays a “house-keeping” function, whereas Fam20A is needed when Fam20C activity is in high demand, e.g., in bone mineralization and liver metabolic functions.26

The PCSK9 mRNA distribution pattern is restricted to liver, olfactory tract, molar, cerebellum, stomach wall and small intestine (Figure 1C). At P10 (Figures 1B, D) and in adult mouse liver (Figures 1F, H) Fam20C and Fam20A are highly expressed and their expression pattern is very similar to that of PCSK9 in some tissues (Figures 1C, G) including hepatocytes (Figure 1E).3 This strongly suggests that in hepatocytes the secretory heterodimer Fam20C/Fam20A is well poised to phosphorylate PCSK9 into pPCSK9, as early as in the ER.25, 26 As is the case for Fam20C that is much better secreted in presence of its allosteric activator Fam20A,26, 28 it is also possible that pPCSK9 is more efficiently secreted from hepatocytes into the circulation compared to its npPCSK9 form. While liver is a privileged site of expression of PCSK9 and also of Fam20C/Fam20A, the adult small intestine only expresses PCSK9 (Figures 1B-D), and the PCSK9-positive duodenum, jejunum and ileum 3 are negative for Fam20C (not shown). This raises the question of the possible functional significance of this observation, especially in relation to the predominantly extracellular activity of liver PCSK9, as compared to the intracellular one in gut.13 We therefore turned our attention to a detailed analysis of the functional importance of the post-translational Ser-phosphorylation of PCSK9 afforded by the maximally active Fam20C/Fam20A heterodimer.26

Using QPCR analyses we analyzed the mRNA levels of Fam20C and Fam20A in mouse liver and in the human cell lines HepG2, HuH7, HEK293 and immortalized human hepatocytes (IHH; Figure 1I). The data show that both mouse liver and the hepatocytes-derived HepG2 cells express similar levels of Fam20C and Fam20A. In contrast, the hepatocyte derived HuH7 and IHH cells express ~1.5–3-fold more Fam20C and Fam20A, whereas kidney epithelial HEK293 cells express very low levels of only Fam20C and are Fam20A negative. This led us to choose HepG2 cells for our cell-based studies and HEK293 cells to prepare PCSK9 and its mutants for extracellular incubations using media swaps.16 We also used HepG2 cells lacking endogenous Fam20C following CRISPR/Cas9 deletion (HepG2-Fam20C−/−).25

Fam20C/Fam20A maximize the PCSK9 activity on the LDLR

To decipher the effect of Ser-phosphorylation on PCSK9, we analyzed its ability to enhance the degradation of the LDLR via the intracellular and extracellular pathways by cellular transfection (Figure 2A)12 and media swap (incubation with PCSK9; Figure 2C), respectively in HepG2-Fam20C−/− cells. We first observed that the presence of both Fam20C and Fam20A resulted in a ~2-fold increased PCSK9 secretion (lane 2 versus lane 11; Figure 2A). Similar to previous reports, the presence of both Fam20C and Fam20A results in (~3–4 fold) increased Fam20C secretion26, 28 and likely its kinase activity.27 The data also showed that an optimal ~3-fold enhanced PCSK9-induced LDLR-degradation is achieved in the presence of active Fam20C/Fam20A (lane 11) compared to inactive Fam20C-D478A/Fam20A (lane 12). Notice that co-expression of Fam20C alone with PCSK9 does not significantly improve its activity over that of its inactive D478A mutant (lanes 8 and 9). Interestingly, the secreted pPCSK9 in the presence of active Fam20C/Fam20A (lane 11) migrates slower on SDS/PAGE than in their absence or in the presence of inactive Fam20C-D478A/Fam20A (lanes 2, 11 and 12), reflecting a delayed migration of pPCSK9 compared to npPCSK9. To prove this, we incubated pPCSK9 with a lambda Protein Phosphatase (λPPase) that resulted in the loss of the delayed migration (Figure 2B).

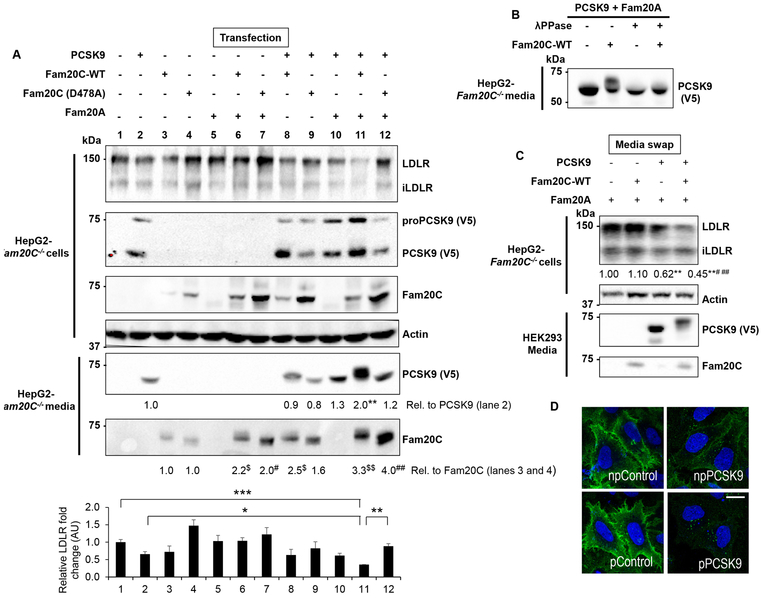

Figure 2:

Fam20C/Fam20A enhance PCSK9 secretion and activity on the LDLR.

(A) HepG2-Fam20C−/− cells were transfected with PCSK9, Fam20A, Fam20C-WT or Fam20C (D478A), a catalytically inactive form. After 18h of serum starvation the media were collected, and cells lysed and subjected to Western blot (WB) analysis with antibodies against the indicated proteins. Representative blots and quantitative densitometry analyses of PCSK9 and Fam20C media are shown. Data represent means of at least three independent experiments. **p<0.01 vs. lane 2, $p<0.05 and $$p<0.01 vs. lane 3, #p<0.05 and ##p<0.01 vs. lane 4, obtained from one-way ANOVA coupled to Tukey's multiple comparisons tests.

(bottom panel) Densitometry analysis of total LDLR and the corresponding statistical analysis. Data represent means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, two-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparisons tests. iLDLR- ~110 kDa immature form of the LDLR that lacks O-glycosylation.

(B) Media of HepG2-Fam20C−/− cells, expressing the indicated constructs were subjected to dephosphorylation by λ-phosphatase then analysed for PCSK9 by WB using anti-V5 antibody.

(C) HepG2-Fam20C−/− cells were incubated for 18h with conditioned media (CM) from HEK293 cells expressing Fam20A along with PCSK9 and Fam20C-WT (media swap). The collected cell lysates and CM were analysed as in (A). Representative blots and corresponding densitometry analysis are shown. Data shown represent means of at least three independent experiments. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs. PCSK9-/Fam20C-, ##p<0.01 vs. PCSK9+/Fam20C-, one-way ANOVA coupled to Tukey's multiple comparisons tests.

(D) Confocal IF microscopy of cell surface LDLR in HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells incubated 18h with control or PCSK9 CM produced as in (C). np = non-phosphorylated, p = phosphorylated. Representative images are from at least three independent experiments. Scale bar, 15 μm.

Next, we compared the extracellular activity of npPCSK9 on the LDLR in HepG2-Fam20C−/− versus pPCSK9 obtained from the media of HEK293 cells expressing PCSK9 and Fam20A or Fam20C/Fam20A, respectively (Figure 2C). Here also, using similar levels of total PCSK9 (estimated by ELISA), pPCSK9 (notice the upward shifted migration) resulted in a significant ~55% reduction in total LDLR levels compared to ~38% achieved with npPCSK9. As controls, in absence of PCSK9, Fam20A or Fam20C/Fam20A did not significantly modify LDLR levels. Furthermore, immunofluorescence (IF) of HepG2 cells lacking endogenous PCSK9 (HepG2-PCSK9−/−) incubated with the above media revealed that pPCSK9 is more effective in reducing cell surface LDLR levels than npPCSK9 (Figure 2D).

The above data suggested that pPCSK9 is more active than npPCSK9 both intracellularly (Figure 2A) and extracellularly (Figure 2C and D), collectively demonstrating that Ser-phosphorylation enhances PCSK9 activity on the LDLR.

In vitro and cellular evidence that Fam20C phosphorylates Ser sites in human PCSK9

Scanning the sequence of human PCSK9 for the presence of potential Fam20C recognition motifs S-X-E/pS revealed five putative Ser-phosphorylation sites at Ser47 (RSEE49D), Ser401 (LSAE403P), Ser666 / Ser668 (STTGSTSEE670A) and Ser688 (ASQE690L) (Figure 3A). Although phosphorylation at Thr664 and Ser662 is possible, it is unlikely since Fam20C prefers by far Ser residues with Glu at the +2 position.25 Thus, we synthesized a reference model peptide representing residues 43–55 of bovine β-casein,25 as well as 4 peptides spanning the sequence of the PCSK9 sites and 3 others carrying the mutant S666A, and the natural single nucleotide polymorphic (SNP) variants R46L (rs11591147) and E670G (SNP rs505151) (Figure 3B).

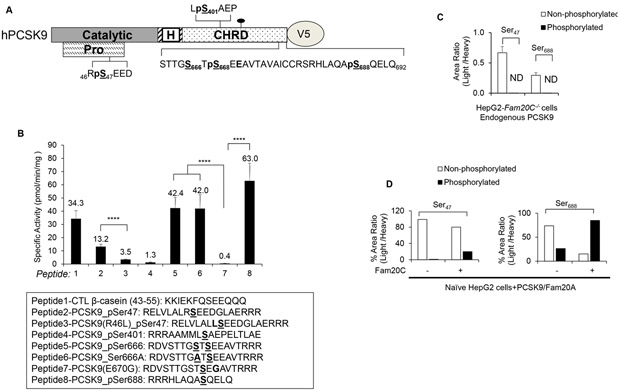

Figure 3:

In vitro and cellular validation of Fam20C-targets on PCSK9.

(A) Schematic representation of potential Fam20C-Ser substrates (S-X-E motif) on hPCSK9-V5. Pro- Pro domain; Catalytic- Catalytic Domain; H- hinge region; CHRD- C-terminal Cys-His–rich domain.

(B) In vitro Fam20C kinase assay measurements with the PCSK9 synthetic peptides as substrates and their specific activity values are indicated (top panel). The peptide sequences are presented and their predicted Ser-phosphosites are in bold and underlined, whereas natural mutations are in bold (bottom panel). The data were obtained from three independent experiments in duplicate. ****p<0.0001, obtained using one-way ANOVA coupled to Tukey's multiple comparisons tests.

(C and D) Levels of non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated PCSK9 peptides spanning (C) Ser47 (S47EEDGLAEAPEHGTTATFHR) and (D) Ser688 (HLAQAS688QELQ) as measured by PAC-qMS assay in the culture medium of HepG2-Fam20C−/− cells (C), naive HepG2 cells with PCSK9 overexpression, and naive HepG2 cells with PCSK9 and Fam20C overexpression (D).

Carriers (2–3% of various ethnicities) of the variant R46L4 have ~10–15% lower LDLc, ~47% decreased cardiovascular risk,43 and a ~28% lower risk of developing abdominal aortic aneurysm.44 The biochemical mechanism behind such a seemingly LOF of PCSK9 is not clear,45 except that the mutant R46L was shown in hepatic HuH7 cells to be ~34% less phosphorylated at Ser47.22

In contrast, the consequence of the E670G variant (frequency ~2–4%)4, 46, 47 has been controversial in terms of LDLc levels. It is sometimes referred to as a GOF because it was associated with higher LDLc levels in Chinese,48 but to have little effect on LDLc in Caucasians 47. In Europeans, the E670G SNP (rs505151) was reported to be associated with increased LDLc in men, but not in women.49 In U.K. men, no significant effect was found between the E670G variant and plasma lipid levels or cardiovascular risk.50 However, this variant was significantly associated with lower LDLc levels in ethnic Chinese in Taiwan.51 Finally, carriers of the E670G SNP are possibly more susceptible to severe malaria symptoms and mortality mostly in males.52 Interestingly, the E670G mutation likely results in a loss of potential phosphorylation at both Ser668 and Ser666, as the S-X-E/Sp motif would be absent.

In vitro phosphorylation of each peptide with a maximally active Fam20C/Fam20A kinase25 revealed that phosphorylation at Ser47 is ~4.8-fold less effective than that at Ser688 and that the R46L mutant is ~3.8-fold less phosphorylated than the WT sequence (peptides 2, 3, 8; Figure 3B). This suggests that within the context of the PCSK9 sequence, a Leu is less favorable than Arg at the −1 position. Surprisingly, virtually no phosphorylation was detected in the peptide mimicking Ser401 (peptide 4; Figure 3B). Even though peptide 4 presents Ser401 in an unstructured non-natural conformation, it is still not phosphorylated, potentially due to the presence of an unfavorable Pro residue at the +3 position.25 Furthermore, in the native PCSK9 protein, Ser401 is found within a structured α-helix that is capped by a neighboring loop (aa 170–178),5 which may partially shield Ser401 making it less likely to be a substrate for Fam20C.

The data also show that the total phosphorylation of the peptide containing Ser666 and Ser668 is similar to that of the S666A mutant peptide (peptides 5, 6; Figure 3B), providing evidence that Ser666 is not significantly phosphorylated as compared to Ser668, and that herein the motif S-X-pS is not favorable, as compared to one in which it is surrounded by acidic residues.25, 40 As expected, the E670G containing peptide that lost the S-X-E recognition motif of Fam20C is not phosphorylated (peptide 7; Figure 3B). Finally, the data clearly show that Ser688 is the most phosphorylated site (peptide 8; Figure 3B), as originally observed by mass spectrometry (MS) in the plasma of human subjects.23

Targeted quantitative MS analysis of the media of HepG2 cells, clearly showed that endogenous PCSK9 is not phosphorylated in cells lacking Fam20C (Fam20C−/− ; Figure 3C), and that in naïve HepG2 cells overexpressing PCSK9 the ratio of phosphorylated to its non-phosphorylated form is ~0.4 for Ser688, while it is ~0.01 for Ser47 (Figure 3D). In contrast, the above ratios greatly increase to ~5.6 and ~0.3, respectively, when PCSK9 and Fam20C/Fam20A are co-expressed, emphasizing the ~20 fold preference of Fam20C phosphorylation of Ser688 versus Ser47 (Figure 3D). Our MS analyses also allowed us to identify two novel PCSK9 phosphorylation sites at Ser666 and Ser668 in the media of HepG2 cells. Indeed, we detected the PCSK9 mono-phosphorylated peptide «DVSTTGS666TS668EEAVTAVAICCR» and identified Ser668 as the predominant site of phosphorylation of this peptide when WT PCSK9 is overexpressed concomitantly with Fam20C/Fam20A (Figure S1A). Surprisingly, while a synthetic peptide containing the E670G mutation was not significantly phosphorylated in vitro by Fam20C (peptide 7; Figure 3B), the mono-phosphorylated tryptic peptide «DVSTTGS666TS668EGAVTAVAICCR» derived from the mutant PCSK9-E670G was predominantly phosphorylated at Ser666 (Figure S1B), with some minor phosphorylation at Ser668 (not shown) in the media of HepG2 cells overexpressing Fam20C/Fam20A. This suggests that while the S-X-E motif is largely preferred by Fam20C,25 it is possible that within the context of S-X-S-X-G670 Fam20C could still phosphorylate either serines without the perfect consensus motif, as it is the case for ApoA5, BPIFB2, IGFBP1, SERPINA1, as well as many other proteins.25

Functional validation of Fam20C/Fam20A mediated Ser-phosphorylation of PCSK9

To dissect out the contributions of each of the Fam20C mediated Ser phospho-sites in PCSK9, we first evaluated the effect of natural PCSK9 mutations that would abrogate or reduce such Ser-phosphorylation using HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells under similar conditions as above. While overexpression of wild type (WT) PCSK9 in these cells resulted in a ~70% reduction in LDLR levels, expression of either its R46L, S668R and E670G natural mutants only reduced LDLR levels by ~40% (Figure 4A). These mutants, which are close to or at Ser-phosphorylation sites, are expected to lower phosphorylation at Ser47 or Ser668 (Figure 3B). Furthermore, incubation of these cells with the same amount of WT or PCSK9 mutants (obtained from HEK293 cells overexpressing Fam20C+Fam20A; media swap) significantly reduced PCSK9 activity compared to WT, with the E670G being virtually inactive (Figure 4B).

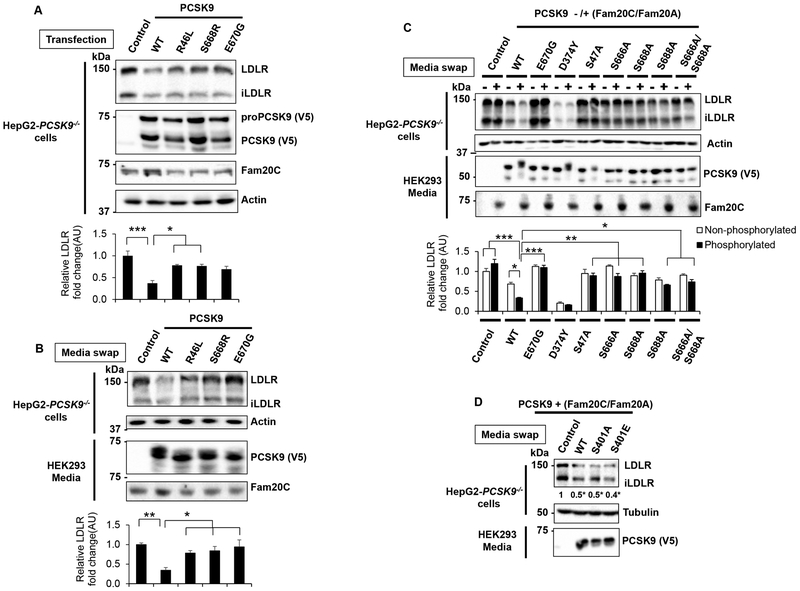

Figure 4:

Characterization of Fam20C-mediated Ser-phosphorylation on PCSK9 activity.

(A) HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells were transfected with V5-tagged control (empty vector) or PCSK9 constructs (WT, R46L, S668R and E670G) in the presence of Fam20C/Fam20A to maximise phosphorylation. After 18h, the cells were lysed and analysed by WB using antibodies against the indicated proteins. Representative blots (top panel) and densitometry quantification (bottom panel) are shown. Data represent means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, one-way ANOVA coupled to Tukey's multiple comparisons tests.

(B) HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells were incubated for 18h with the CM of HEK293 cells expressing V5-tagged empty vector or PCSK9 constructs (WT, R46L, S668R and E670G) in the presence of Fam20C/Fam20A (media swap). The cells were then lysed and analysed as in (A). Representative blots and densitometry analysis are shown (top and bottom panels, respectively). Data represent means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, one-way ANOVA coupled to Tukey's multiple comparisons tests.

(C and D) HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells were incubated for 18h with the CM of HEK293 cells expressing V5-tagged control or PCSK9-WT and mutated constructs (E670G, D374Y, S47A, S666A, S668A, S688A and S666A/S668A) in the absence (−) or presence (+) of Fam20C/Fam20A as indicated. The cells were then lysed and analysed as in (A). Representative blots (top panels in C, and D) and densitometry quantification (D and bottom panel in C) are shown.

(C) Data represent means ± SEM of five independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, obtained by two-way ANOVA coupled to Tukey's multiple comparisons tests.

(D) Data represent means ± SEM of three independent experiments. *p<0.05, obtained by one-way ANOVA coupled to Tukey's multiple comparisons tests.

We next wished to identify in HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells the relative contribution of the various Ser-phosphorylation sites on the activity of extracellular PCSK9 on endogenous LDLR (Figure 4C and D) and intracellular PCSK9 on overexpressed LDLR (Figure S2A and B). The data showed that the GOF PCSK9-D374Y is maximally active whether it is phosphorylated or not. However, WT PCSK9 is ~2-fold more active when phosphorylated by Fam20C/Fam20A in both pathways. Substitution of each putative Ser by Ala would abrogate its phosphorylation. In the extracellular pathway, except for PCSK9-S401A and -S401E that remain as active as WT (Figure 4D), the loss of any Ser phosphorylation resulted in virtually complete abrogation of PCSK9 activity compared to WT, and this effect is not significantly affected by the co-expression of PCSK9 Ala-mutants with Fam20C/Fam20A (Figure 4C). In the intracellular pathway, the data also show that the S401A mutation does not affect PCSK9 activity. Furthermore, in the intracellular pathway despite the loss-of-phosphorylation at serines 47, 666, 668, and 688, PCSK9 remains partially active on the LDLR, but co-expression with Fam20C/Fam20A no longer enhances its activity (Figure S2A and B). In contrast, the mutants E670G, S668A and the double S666A/668A that are not phosphorylated at Ser668 are not significantly active. In conclusion, the data suggested that Ser-phosphorylation is critical for PCSK9 activity and that Ser668,688 are likely the most sensitive sites affecting the activity of PCSK9 in the intracellular pathway. Collectively, while Ser401 is likely not phosphorylated (Figure 3B and 4D; Figure S2B), the identified four phosphorylation sites seem to act synergistically to ensure maximal PCSK9 activity. Finally, the upper phosphorylated band is clearly visible in the medium (Figures 4C), but seems conspicuously absent or low in the lysates (Figure S2A). This may be due to the localization of Fam20C in the Golgi,25 and the speed of subsequent secretion of phosphorylated proteins, reflected by higher secreted levels of pPCSK9 (Figure 2A).

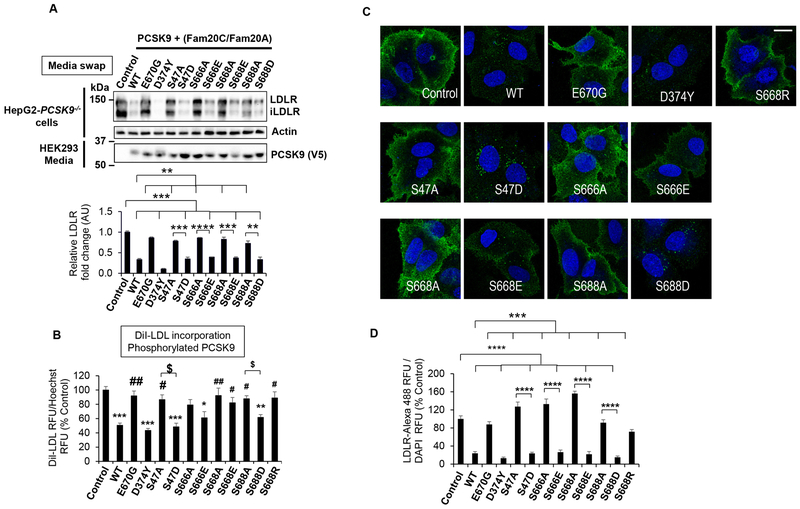

We next validated the importance of the four Ser-phosphorylation sites by first systematically replacing them by the phosphomimetic Glu or Asp, or silenced them by Ala mutations. We then assessed the extracellular phosphorylated PCSK9 activity on LDLR. This was done by Western blotting of total endogenous LDLR in HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells (Figure 5A) and mouse primary hepatocytes of Pcsk9−/− mice (Figure S2C), by DiI-LDL incorporation (Figure 5B), and IF of cell surface LDLR (Figure 5C, D) in HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells. In all cases mutation of each pSer site to Ala resulted in an almost complete LOF. Furthermore, replacement of pSer by Glu or Asp significantly enhanced the activity of PCSK9 on LDLR (Figure 5A), especially evident in enhanced diI-LDL uptake (Figure 5B), and immunocytochemical surface LDLR levels under non-permeable conditions (Figures 5C, D). However, the non-phosphorylated media of either WT, phosphomimetic Glu/Asp, or Ala PCSK9 mutants showed little extracellular activity on the LDLR as evidenced by Western blotting in HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells (Figure S2D) and by DiI-LDL incorporation (Figure S4). Thus, our data revealed that only the globally phosphorylated pPCSK9 exhibits a GOF, and that phosphorylation of individual sites, i.e., using phosphomimetic E/D mutants in absence of co-transfection with Fam20C/Fam20A, does not significantly affect the activity of PCSK9 on the LDLR (Figure 5A versus Figure S2D; and Figure 5B versus Figure S4). Overall, the data confirm the importance of the global Ser-phosphorylation in enhancing PCSK9-activity on the LDLR in all studied cells.

Figure 5:

Effects of PCSK9-phosphosphomimetics on LDLR degradation.

(A) HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells were incubated for 18h with CM from HEK293 cells expressing V5-tagged control, PCSK9-WT or mutated constructs (E670G, D374Y, S47A, S47D, S666A, S666E, S668A, S668E, S688A and S688D) in the presence of Fam20C/Fam20A. The cells were then lysed and analysed by WB using antibodies against the indicated proteins. Representative blots (top panels) and densitometry quantification (bottom panel) are shown. The data represent means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 and ****p<0.0001, obtained by one-way ANOVA coupled to Tukey's multiple comparisons tests.

(B) Dil-LDL uptake. HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells were incubated for 20h with phosphorylated PCSK9 CM from HEK293 cells expressing V5-tagged control or PCSK9 constructs (WT, E670G, D374Y, S47A, S47D, S666A, S666E, S668A, S668E, S688A, S688D and S668R), in the presence of Fam20C/Fam20A. During the last 3h of incubation, Dil-LDL was added to the CM. The cells were then fixed and the Dil-LDL fluorescence quantified. The data represent means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments in quadruplicates. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. Control, #p<0.05 and ##p<0.01 vs. WT, $p<0.05, one-way ANOVA coupled to Tukey's multiple comparisons tests.

(C) Confocal IF of cell surface LDLR in HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells incubated with phosphorylated PCSK9 CM from HEK293 cells expressing V5-tagged control or PCSK9-WT, and mutated constructs (E670G, D374Y, S47A, S47D, S666A, S666E, S668A, S668E, S688A, S688D and S668R), in the presence of Fam20C/Fam20A. After 18h of incubation the cells were fixed and processed for IF. Representative images are shown for each condition. Scale bar, 15 μm.

(D) Quantifications were derived from analyses of 8 fields/condition/experiment. Data are averages ± SEM of two independent experiments. ***p<0.001 and ****p<0.0001, obtained by one-way ANOVA coupled to Tukey's multiple comparisons tests.

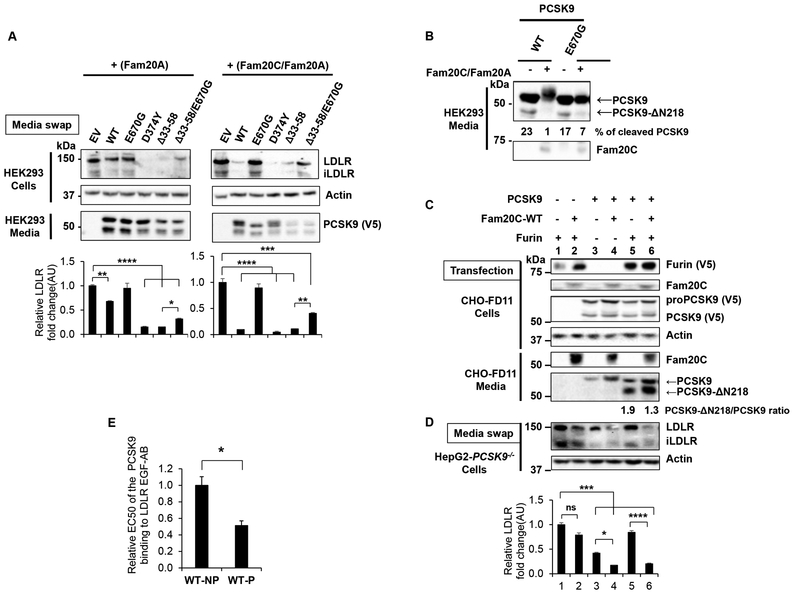

Dual regulation of PCSK9 activity by pSer668 and its N-terminal auto-inhibitory domain

We also used a pro-domain deletant (PCSK9-Δ33–58) that is ~4-fold more active on LDLR than WT PCSK9 (Figure 6A).33 Here, the lack of Ser47 was compensated for by the absence of the auto-inhibitory function of the acidic N-terminal domain comprised in aa 33–58.45 Accordingly, for the constructs containing Δ33–58, the loss of activity due to the E670G mutation is more evident in the presence of Fam20C/Fam20A (~4-fold; Figure 6A, last two lanes right panel) than in its absence (~2-fold; Figure 6A, last two lanes left panel). In conclusion, a balance exists between the enhanced activity of PCSK9 due to the C-terminal pSer668 and the auto-inhibitory effect of the N-terminal aa 33–58.

Figure 6:

Effect of PCSK9 pro-domain and Furin in PCSK9-mediated LDLR degradation.

(A) Effect of PCSK9 Δ33-58 deletion. HEK293 cells were incubated for 18h with CM from HEK293 cells expressing V5-tagged control, PCSK9-WT or mutated constructs, D374Y, E670G, Δ33-58 and Δ33-58-E670G in the presence of Fam20A (non-phosphorylated, left panel) or Fam20C/Fam20A (phosphorylated, right panel). Cell lysates were analysed by WB using the indicated antibodies. Representative blots (top panels) and densitometry quantification (bottom panels) are shown. Data represent means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, obtained by one-way ANOVA coupled to Tukey's multiple comparisons tests.

(B-C) Fam20C affects Furin-mediated PCSK9 cleavage. (B) HEK293 cells were transfected with V5-tagged PCSK9-WT or Fam20C/Fam20A. After 18h of serum starvation, PCSK9 media were collected and analyzed by WB. Representative blots of at least three independent experiments are shown. The migration position of the Furin-cleaved PCSK9 (PCSK9-Δ218) as well as the % cleavage by endogenous Furin are emphasized.

(C) CM from CHO-FD11 Furin−/− cells transfected with the indicated constructs (i.e., PCSK9-V5, Furin-V5 and Fam20C-WT/Fam20A). Cell lysates and media were analysed by WB and representative blots of at least three independent experiments are shown.

(D) HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells were incubated for 18h with the media produced in (C) and LDLR levels analysed by WB. Representative blots (top panels) and densitometry quantification (bottom panels) are shown. Data represent means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, obtained by two-way ANOVA coupled to Tukey's multiple comparisons tests; ns- non-significant.

(E) Relative PCSK9-LDLR binding assay. Microplates pre-coated with recombinant LDLR EGF-AB domain, which contains the PCSK9 binding site, were incubated for 18h with non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated PCSK9 CM obtained from HEK293 cells expressing V5-tagged PCSK9-WT in the absence or presence of Fam20C/Fam20A, respectively. The binding affinity of PCSK9 to LDLR was determined following analyses with 8 different concentrations per sample and the calculated relative EC50 values of WT phosphorylated PCSK9 (WT-P) were normalized to WT non-phosphorylated PCSK9 (WT-NP) as shown in (B). Data are averages ± SEM of two independent experiments. *p<0.05, obtained by unpaired two-tailed student t-test.

Phosphorylation affects PCSK9 cleavage by Furin

Previous studies showed that PCSK9 is cleaved by Furin at the RFHR218↓ site within the catalytic subunit.53 Such Furin-processing results in PCSK9 inactivation both in cells and in vivo as a result of the separation of the prodomain from the protein.36, 53, 54 However, it was reported that cleavage of PCSK9 by purified Furin in vitro does not completely inactivate its function.55 This may be due to the artificially remaining C-terminal Arg218 and Gln219 in the segments comprising aa 153–218, and aa 219–692, which remain non-covalently attached. In cells and in vivo, Arg218 is removed by cellular carboxypeptidases and Gln219 cyclizes to pyro-glutamic acid, resulting in the separation of the two fragments, as well as the prosegment and hence inactivation of the remaining PCSK9.54

Our results revealed a virtually complete loss of the Furin processing of pPCSK9-WT (+Fam20C) compared to npPCSK9-WT (1% vs 23%), whereas, the natural mutant E670G which is not-phosphorylated at Ser668, displays a partial (~7%) cleavage by endogenous Furin (Figure 6B). Our data suggest that Fam20C reduces by ~23-fold the Furin cleavage of WT PCSK9 and by ~2.4-fold that of its E670G mutant. Accordingly, we investigated the effect of both Furin and Fam20C/Fam20A on PCSK9 cleavage and activity using CHO-FD11 cells, which lack endogenous Furin expression,56 to generate PCSK9 in the media used to assess its activity on LDLR in HepG2-PCSK9−/− cells (Figure 6C). As expected, in absence of Furin, both npPCSK9 and pPCSK9 are not processed into PCSK9-ΔN218 (Figure 6C; lanes 3, 4), and enhance the degradation of the LDLR, with pPCSK9 being ~2.4-fold more active (Figure 6D; lanes 3, 4). On the other hand, overexpression of Furin led to a ~50% higher cleavage of npPCSK9 vs pPCSK9 (Figure 6C, lanes 5, 6). Also, in agreement with our previous work, Furin expression reduced by ~80% the activity of npPCSK9 on LDLR, while co-expression of Fam20C along with Furin restored the full-pPCSK9 activity (Figure 6D; lanes 5, 6). Thus, serine phosphorylation leads to a higher PCSK9 activity that exceeds the LOF induced by the partial Furin cleavage.

Phosphorylation enhances the global PCSK9 binding to the LDLR

In an attempt to understand the underlying mechanism of the phosphorylation-induced GOF of PCSK9 we assessed the binding affinity of npPCSK9 compared to pPCSK9, both produced in HEK293 cells. As shown in Figure 6E, analysis of the in vitro binding affinities of these two forms of PCSK9 to the LDLR-EGF AB fragment57 revealed that pPCSK9 has a 2-fold lower EC50 compared to npPCSK9 (Figure 6E). This suggests that PCSK9 Ser-phosphorylation enhances its binding affinity to the LDLR by a global conformational effect, since the catalytic domain of PCSK9 that binds LDLR is far removed from the Ser-phosphorylation sites.

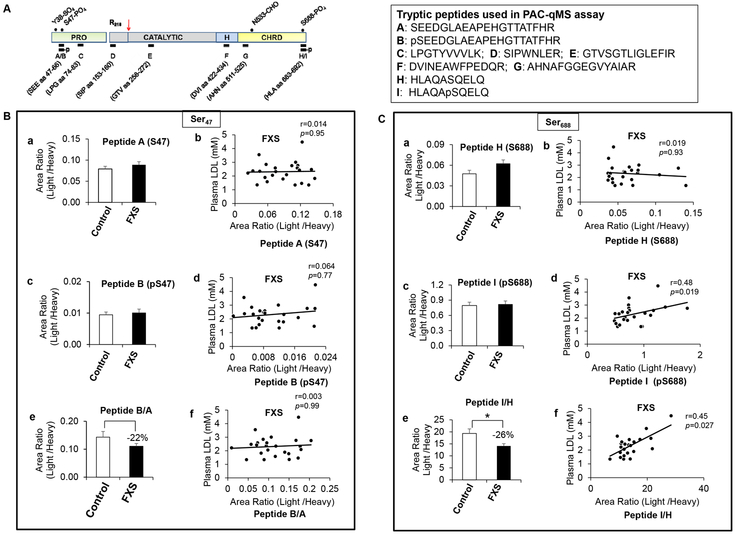

Clinical relevance of pPCSK9: application to FXS

The enhanced ability of phosphorylated PCSK9 to degrade the LDLR described above prompted us to investigate the phosphorylation status of PCSK9 in FXS patients. We previously reported that, although FXS patients show reduced levels of peripheral cholesterol accompanied by a concomitant reduction in HDL and LDL, no difference was found in their plasma PCSK9, estimated by ELISA,30 when compared to healthy individuals. We reasoned that the Ser-phosphorylation of PCSK9 in FXS patients might offer an explanation for this discrepancy.

To do so, we developed a Protein Affinity Capture coupled to quantitative Mass Spectrometry (PAC-qMS) assay23 that allows the multiplexed quantification of 9 different PCSK9 peptides spanning the various protein domains and the Ser47 and Ser688 phosphorylation sites (Figure 7A). We have selected these peptides because of ease of MS quantification, as compared to those spanning the Ser668 site, which is more difficult to quantitate by MS (Figure S1). Our assay is reproducible and linear over PCSK9’s clinical range.23, 24 The assay was used to quantify the plasma levels of these peptides in 25 controls versus 26 patients with FXS, and the results were then plotted against circulating LDLc levels. Similar to what was found previously,30 there were no differences in the plasma levels of most of the measured PCSK9 peptides between the controls and FXS patients (Figure 7, Figure S3). However, the phosphorylation state of PCSK9 at Ser688, as measured by the ratio of pPCSK9/npPCSK9 at Ser688 (peptides I/H), shows a significant ~26% decrease (p<0.05) in FXS patients versus controls (Figure 7Ce). In addition, while there were no correlation between most of the measured plasma PCSK9 peptides and LDLc levels in FXS patients (Figure 7 Bb, Bd, Bf, Cb; Figure S3), we found a significant correlation between LDLc levels and pPCSK9 at Ser688 (peptide I; r = 0.48; p =0.019) and the ratio of I/H (r = 0.45; p =0.027) (Figures 7Cd, Cf), but not in healthy control individuals (data not shown). Notice that similar to our observations in our model HepG2 cells (Figures 3D), in human plasma we also observed that the ratio of pSer47/Ser47 is ~0.1, revealing a low phosphorylation state at Ser47 (Figure 7Ba,c), whereas the ratio of pSer688/Ser688 is ~17 in favor of pSer688 (Figure 7Ca,c). Altogether, our results suggest that compared to controls, in FXS patients circulating PCSK9 is less phosphorylated at its most favorable site Ser688, and hence is likely less active on the LDLR. This may provide some rationale to the observed lower levels of LDLc in FXS patients.30

Figure 7:

PSCK9 Ser-phosphorylation likely modulates its activity in FXS patients.

(A) Schematic representation of PCSK9 and the peptide used for PAC-qMS assay. Positions (left panel) and sequences (right panel) of the 9 monitored tryptic peptides on the mature PCSK9-protein sequence are shown. R218 is the Furin cleavage site.

(B and C) Plasma from control and FXS groups were subjected to PCSK9 peptide quantification by PAC-qMS. The results were reported as area ratios which represent the area under the curve of the endogenous (light) relative to the heavy isotope-labelled peptide reference (Panels: Ba, Bc, Be, Ca, Cc and Ce). After that, the peptides’ area ratios of FXS subjects were plotted against their circulating LDL levels (Panels: Bb, Bd, Bf, Cb, Cd and Cf). Correlations show the Spearman's rho coefficients (r) and its p-value (p).. The peptides spanning Ser47, pSer47 (B), Ser688 and pSer688 (C) are shown. Results are means ± SEM (Control: n = 25; FXS: n= 26). *p<0.05 after adjustment for multiple hypothesis testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure.

DISCUSSION

PCSK9 undergoes several post-translational modifications (PTM) including N-glycosylation,3 Tyr-sulfation21 and Ser-phosphorylation.22 Herein, we hypothesized that Ser-phosphorylation could affect PCSK9’s ability to effectively enhance the degradation of the LDLR or other targets. Accordingly, in the current study we documented for the first time the regulation of PCSK9 activity by Ser-phosphorylation and identified the complex Fam20C/Fam20A25, 26 as the major secretory kinase of PCSK9. Our data revealed that phosphorylation of PCSK9 enhances by ~2-fold its binding affinity to the LDLR EGF-AB (Figure 6E), as well as its secretion and activity on the LDLR. Since PCSK9 can bind the LDLR as early as the ER and in the Golgi,25 upon its phosphorylation the complex pPCSK9-LDLR may be more stable and result in enhanced trafficking of PCSK9 to the cell surface and its secretion. In parallel, we observed an increased Fam20C phosphorylation and secretion in the presence of Fam20A (Figure 2A) and likely an enhanced kinase activity, as previously reported.28

In support of these data we now document the comparative tissue mRNA distribution of PCSK9, Fam20C and Fam20A by IHyH during embryonic development and in adult mice (Figure 1). Our results show that at P10 and in adult mice the mRNAs coding for these proteins are highly expressed and co-localize in liver hepatocytes. In contrast, while PCSK9 expression is rich in the small intestine, both Fam20C and Fam20A are not expressed in this tissue (Figure 1). Since liver is the principal synthesis3 and secretion site of circulating PCSK9,17 its phosphorylation by Fam20C/Fam20A likely upregulate the levels of circulating PCSK9 and significantly enhance its extracellular activity. In contrast, the absence of Fam20C/Fam20A in the small intestine might also rationalize the restricted activity of PCSK9 on the LDLR to the intracellular pathway in this tissue.12, 18, 20 Analysis of PCSK9 plasma levels and/or function in the liver versus small intestine of Fam20C KO mice,58 or in human patients lacking Fam20C such as those suffering from Raine syndrome59 might shed some light on the observed tissue-specific segregation of the extracellular and intracellular activity of PCSK9.

We next identified the 4 phosphoserine residues in PCSK9 that are targeted by Fam20C, namely pSer47, pSer666, pSer668 and pSer688 (Figure 3). We provided evidence that point mutation to Ala of any of the above serines significantly reduced pPCSK9’s ability to enhance the degradation of the LDLR, an activity that was restored by the phosphomimetic Glu or Asp mutations (Figures 4, 5). It was surprising that loss of any one of the Ser-phosphorylation sites would significantly reduce the whole pPCSK9 activity (Figure 4C). The root cause of this “synergism” may result from the reduced global phosphorylation status caused by a single mutation. This suggests that Ser-phosphorylation may modify the conformation of PCSK9 to favor its ability to bind to and/or efficiently escort the LDLR towards degradation compartments. Indeed, pPCSK9 binds ~2-fold better the LDLR EGF-AB domain compared to npPCSK9 (Figure 6E). Furthermore, since pSer666, pSer668 and pSer688 occur in the C-terminal M3 domain of the CHRD,5 they may enhance the binding of this domain to a putative partner protein implicated in the efficient escort of the PCSK9-LDLR complex to lysosomes, as proposed.9, 60 Our conclusions were supported by the LOF phenotype displayed by the natural point mutants R46L,4, 50 S668R61 and E670G51 laying within the Fam20C preferred phosphorylation S-X-E motif, that indeed should result in lower PCSK9 phosphorylation, as observed for R46L,22 as well as its activity on the LDLR (Figures 3, 4).

The observation that the lack of the negatively charged N-terminal domain of PCSK9 (Δ33–58) is associated with a GOF due to a stronger binding of PCSK9 to the EGF-AB domain of the LDLR7, 45, 62 was confirmed in our study (Figure 6A). However, this auto-inhibitory activity of the acidic N-terminal domain of PCSK9 seems to be regulated by the presence of a charged Arg46 just following a predicted α-helical segment comprising aa 37–45.62 Indeed, the natural mutation R46L, which eliminates the positive charge, results in a further LOF accompanied by a lower phosphorylation at Ser47 (Figures 3B, 4B).22 The fact that the S47D is a GOF (Figure 5), rather than a LOF should the negative charges be the sole regulators of the PCSK9 activity, suggests that pSer47 enhanced activity of PCSK9 likely implicates a more global effect involving synergistic phosphorylation-induced conformational changes in PCSK9.

We previously showed that PCSK9 cleavage by Furin at Arg218↓53 within an exposed unstructured loop5 eliminates the PCSK9 activity on LDLR.53 Herein, we report that Fam20C/Fam20A significantly eliminate the Furin-cleavage of PCSK9 (Figure 6D; lanes 5, 6), thereby enhancing the pPCSK9 activity even further. This may be related to a global conformational change of pPCSK9, as we also observed a similarly reduced Furin cleavage of the GOF mutant D374Y (Figure 4C).53 The artificially produced PCSK9-Δ33–58 is also a GOF that enhances the binding to the EGF-AB by ~4–7 fold7, 33 via a global conformational effect and can partially compensate for the LOF caused by the loss of phosphorylation at Ser668, as evidenced by the relative activity of the double mutant PCSK9-Δ33–58/E670G in the absence versus presence of Fam20C/Fam20A (Figure 6A). Thus, we believe that the GOF achieved by Ser-phosphorylation is due to a combinatorial effect of higher secretion and binding to the LDLR and lower extent of inactivation by Furin.

Since Fam20C has many substrates,25 and human Furin exhibits 3 potential pS-X-E phosphorylation sites at its C-terminal non-catalytic domain, it is possible that phosphorylation at these sites may affect the overall activity of Furin. This may occur in part via the modulation of the trafficking of Furin to the cell-surface where it cleaves PCSK9.36 In addition, human LDLR exhibits 11 potential pS-X-E phosphorylation sites, 10 of which occur in the N-terminal 7 repeat domains, and one in the highly structured β-propeller domain at Ser648 within the sequence NLLSPED651 of the LDLR. Since, our data showed that the PCSK9 S401-X-E-P site is not phosphorylated by Fam20C (Figure 3B), it could be speculated that subjects harboring the natural mutation LDLR-P649L63 may have a more favorable pSer648 site. Interestingly, the pSer648 just follows the LDLR-Leu647 that interacts with PCSK9-Leu108 in the prodomain and stabilizes it.8, 16 In that context, we reported that the natural mutant PCSK9-L108R is associated with FH and results in a GOF of PCSK9.64 It is likely that the positively charged PCSK9-L108R could bind with higher affinity the negatively charged pSer648 of the LDLR resulting in a GOF.

In conclusion, aside from the multiple substrates of Fam20C,25 our data strongly suggest that this secretory kinase phosphorylates PCSK9 and likely LDLR and Furin, thereby regulating LDLc. Since cholesterol is a key component in the neurodevelopment and abnormally low levels could modulate the phenotype of certain pathologies, defects in this regulation may be important in normal and pathological conditions, such as FXS. Therefore, measurements of pPCSK9 would be a better biomarker and more indicative of disease states than npPCSK9. ELISA assays measure total PCSK9 regardless of its phosphorylation state, and may miss correlations of maximally active forms of pPCSK9 to disease and/or response to drug treatments. Future studies should unravel the consequences of PCSK9 phosphorylation state on other PCSK9 modulated conditions such as sepsis and inflammation.13, 65, 66

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

PCSK9 is phosphorylated at serines 47, 666, 668, and 688 by Fam20C

Ser-phosphorylation enhances the secretion and activity of PCSK9 on the LDLR

Plasma quantification of phospho-PCSK9 defines its maximally active protein levels

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Denis Faubert (IRCM Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics core facility, Montreal, QC, Canada) for helpful assistance in phosphosite identification, the IRCM Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics core facility team for analyzing our samples by mass spectrometry, and Vanessa Gaspar for her technical help. The authors acknowledge the expert secretarial assistance of Mrs Brigitte Mary.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research grants Foundation Scheme 148363 and MOP 102741, a Canada Research Chair 231335, and a Fondation Leducq grant #13CVD03 (to N.G.S.) as well as a Welch Foundation Grant I-1911 (to V.S.T.). A.B.D.O. is a recipient of the IRCM Foundation-Jean Coutu fellowship.

ABBREVIATIONS

- LDLc

low density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- LDLR

LDL-receptor

- LOF

loss-of-function

- PCSK9

proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin-9

- GOF

gain-of-function

- IHyH

In situ hybridization histochemistry

- FXS

fragile-X-syndrome

- pS

Ser-phosphorylation

- CM

conditioned media

- MS

mass spectrometry

- Dil-LDL

1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethyl-indocarbocyanine perchlorate

- pPCSK9

phosphorylated PCSK9

- npPCSK9

non-phosphorylated PCSK9

- IHH

immortalized human hepatocytes

- λPPase

lambda Protein Phosphatase

- IF

immunofluorescence

- PAC-qMS

Protein Affinity Capture coupled to quantitative Mass Spectrometry.

Footnotes

Disclosure

None

REFERENCES

- 1.Hobbs HH, Russell DW, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. The LDL receptor locus in familial hypercholesterolemia: Mutational analysis of a membrane protein. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1990;24:133–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brautbar A, Leary E, Rasmussen K, Wilson DP, Steiner RD, Virani S. Genetics of familial hypercholesterolemia. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. . 2015;17:491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seidah NG, Benjannet S, Wickham L, Marcinkiewicz J, Jasmin SB, Stifani S, Basak A, Prat A, Chretien M. The secretory proprotein convertase neural apoptosis-regulated convertase 1 (NARC-1): Liver regeneration and neuronal differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:928–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abifadel M, Varret M, Rabes JP, et al. Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:154–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham D, Danley DE, Geoghegan KF, et al. Structural and biophysical studies of PCSK9 and its mutants linked to familial hypercholesterolemia. Nat Struct Mol Biol. . 2007;14:413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park SW, Moon YA, Horton JD. Post-transcriptional regulation of low density lipoprotein receptor protein by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9a in mouse liver. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:50630–50638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwon HJ, Lagace TA, McNutt MC, Horton JD, Deisenhofer J. Molecular basis for LDL receptor recognition by PCSK9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:1820–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surdo PL, Bottomley MJ, Calzetta A, Settembre EC, Cirillo A, Pandit S, Ni YG, Hubbard B, Sitlani A, Carfi A. Mechanistic implications for LDL receptor degradation from the PCSK9/LDLR structure at neutral pH. EMBO Rep. . 2011;12:1300–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seidah NG, Awan Z, Chretien M, Mbikay M. PCSK9: A key modulator of cardiovascular health. Circ. Res. 2014;114:1022–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nassoury N, Blasiole DA, Tebon OA, Benjannet S, Hamelin J, Poupon V, McPherson PS, Attie AD, Prat A, Seidah NG. The cellular trafficking of the secretory proprotein convertase PCSK9 and its dependence on the LDLR. Traffic. . 2007;8:718–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameron J, Holla OL, Ranheim T, Kulseth MA, Berge KE, Leren TP. Effect of mutations in the PCSK9 gene on the cell surface LDL receptors. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:1551–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poirier S, Mayer G, Poupon V, McPherson PS, Desjardins R, Ly K, Asselin MC, Day R, Duclos FJ, Witmer M, Parker R, Prat A, Seidah NG. Dissection of the endogenous cellular pathways of PCSK9-induced LDLR degradation: Evidence for an intracellular route. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:28856–28864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seidah NG, Abifadel M, Prost S, Boileau C, Prat A. The proprotein convertases in hypercholesterolemia and cardiovascular diseases: Emphasis on proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9. Pharmacol. Rev. 2017;69:33–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen J, Pertsemlidis A, Kotowski IK, Graham R, Garcia CK, Hobbs HH. Low LDL cholesterol in individuals of african descent resulting from frequent nonsense mutations in PCSK9. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:161–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elbitar S, Khoury PE, Ghaleb Y, Rabes JP, Varret M, Seidah NG, Boileau C, Abifadel M. Proprotein convertase subtilisin / kexin 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors and the future of dyslipidemia therapy: An updated patent review (2011–2015). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2016;26:1377–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Susan-Resiga D, Girard E, Kiss RS, Essalmani R, Hamelin J, Asselin MC, Awan Z, Butkinaree C, Fleury A, Soldera A, Dory YL, Baass A, Seidah NG. The proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9-resistant r410s low density lipoprotein receptor mutation: A novel mechanism causing familial hypercholesterolemia. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:1573–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaid A, Roubtsova A, Essalmani R, Marcinkiewicz J, Chamberland A, Hamelin J, Tremblay M, Jacques H, Jin W, Davignon J, Seidah NG, Prat A. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9): Hepatocyte-specific low-density lipoprotein receptor degradation and critical role in mouse liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2008;48:646–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cariou B, Si-Tayeb K, Le MC. Role of PCSK9 beyond liver involvement. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2015;26:155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le May C, Berger JM, Lespine A, Pillot B, Prieur X, Letessier E, Hussain MM, Collet X, Cariou B, Costet P. Transintestinal cholesterol excretion is an active metabolic process modulated by PCSK9 and statin involving abcb1. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013;33:1484–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roubtsova A, Chamberland A, Marcinkiewicz J, Essalmani R, Fazel A, Bergeron JJ, Seidah NG, Prat A. PCSK9 deficiency unmasks a sex/tissue-specific subcellular distribution of the ldl and vldl receptors in mice. J. Lipid Res. 2015;56:2133–2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benjannet S, Rhainds D, Essalmani R, et al. NARC-1/PCSK9 and its natural mutants: Zymogen cleavage and effects on the low density lipoprotein (ldl) receptor and ldl cholesterol. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:48865–48875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dewpura T, Raymond A, Hamelin J, Seidah NG, Mbikay M, Chretien M, Mayne J. PCSK9 is phosphorylated by a golgi casein kinase-like kinase ex vivo and circulates as a phosphoprotein in humans. FEBS J. 2008;275:3480–3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gauthier MS, Perusse JR, Awan Z, et al. A semi-automated mass spectrometric immunoassay coupled to selected reaction monitoring (msia-srm) reveals novel relationships between circulating PCSK9 and metabolic phenotypes in patient cohorts. Methods. 2015;81:66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gauthier MS, Awan Z, Bouchard A, Champagne J, Tessier S, Faubert D, Chabot K, Garneau PY, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Seidah NG, Ridker PM, Genest J, Coulombe B. Posttranslational modification of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 is differentially regulated in response to distinct cardiometabolic treatments as revealed by targeted proteomics. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2018;12:1027–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tagliabracci VS, Wiley SE, Guo X, et al. A single kinase generates the majority of the secreted phosphoproteome. Cell. 2015;161:1619–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang H, Zhu Q, Cui J, Wang Y, Chen MJ, Guo X, Tagliabracci VS, Dixon JE, Xiao J. Structure and evolution of the fam20 kinases. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cui J, Xiao J, Tagliabracci VS, Wen J, Rahdar M, Dixon JE. A secretory kinase complex regulates extracellular protein phosphorylation. Elife. 2015;4:e06120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohyama Y, Lin JH, Govitvattana N, Lin IP, Venkitapathi S, Alamoudi A, Husein D, An C, Hotta H, Kaku M, Mochida Y. Fam20a binds to and regulates Fam20c localization. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:27784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berry-Kravis E, Levin R, Shah H, Mathur S, Darnell JC, Ouyang B. Cholesterol levels in fragile X syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2015;167A:379–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caku A, Seidah NG, Lortie A, Gagne N, Perron P, Dube J, Corbin F. New insights of altered lipid profile in fragile × syndrome. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Attie AD, Seidah NG. Dual regulation of the LDL receptor--some clarity and new questions. Cell Metab. 2005;1:290–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Awan Z, Seidah NG, MacFadyen JG, Benjannet S, Chasman DI, Ridker PM, Genest J. Rosuvastatin, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 concentrations, and ldl cholesterol response: The jupiter trial. Clin. Chem. 2012;58:183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjannet S, Saavedra YG, Hamelin J, Asselin MC, Essalmani R, Pasquato A, Lemaire P, Duke G, Miao B, Duclos F, Parker R, Mayer G, Seidah NG. Effects of the prosegment and pH on the activity of PCSK9: Evidence for additional processing events. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:40965–40978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Susan-Resiga D, Essalmani R, Hamelin J, Asselin MC, Benjannet S, Chamberland A, Day R, Szumska D, Constam D, Bhattacharya S, Prat A, Seidah NG. Furin is the major processing enzyme of the cardiac-specific growth factor bone morphogenetic protein 10. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22785–22794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ly K, Saavedra YG, Canuel M, Routhier S, Desjardins R, Hamelin J, Mayne J, Lazure C, Seidah NG, Day R. Annexin A2 reduces PCSK9 protein levels via a translational mechanism and interacts with the m1 and m2 domains of PCSK9. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:17732–17746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Essalmani R, Susan-Resiga D, Chamberland A, Abifadel M, Creemers JW, Boileau C, Seidah NG, Prat A. In vivo evidence that furin from hepatocytes inactivates PCSK9. J Biol. Chem. . 2011;286:4257–4263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dubuc G, Tremblay M, Pare G, Jacques H, Hamelin J, Benjannet S, Boulet L, Genest J, Bernier L, Seidah NG, Davignon J. A new method for measurement of total plasma PCSK9: Clinical applications. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:140–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dubuc G, Chamberland A, Wassef H, Davignon J, Seidah NG, Bernier L, Prat A. Statins upregulate PCSK9, the gene encoding the proprotein convertase neural apoptosis-regulated convertase-1 implicated in familial hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1454–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao J, Tagliabracci VS, Wen J, Kim SA, Dixon JE. Crystal structure of the golgi casein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:10574–10579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tagliabracci VS, Engel JL, Wen J, Wiley SE, Worby CA, Kinch LN, Xiao J, Grishin NV, Dixon JE. Secreted kinase phosphorylates extracellular proteins that regulate biomineralization. Science. 2012;336:1150–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological). 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Essalmani R, Weider E, Marcinkiewicz J, Chamberland A, Susan-Resiga D, Roubtsova A, Seidah NG, Prat A. A single domain antibody against the cys- and his-rich domain of PCSK9 and evolocumab exhibit different inhibition mechanisms in humanized PCSK9 mice. Biol. Chem. 2018;399:1363–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH Jr, Hobbs HH. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low ldl, and protection against coronary heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:1264–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klarin D, Damrauer SM, Cho K, et al. Genetics of blood lipids among ~300,000 multi-ethnic participants of the million veteran program. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:1514–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seidah NG. The elusive inhibitory function of the acidic n-terminal segment of the prodomain of PCSK9: The plot thickens. J. Mol. Biol. 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leren TP. Mutations in the PCSK9 gene in norwegian subjects with autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Clin. Genet. 2004;65:419–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]