ABSTRACT

Sunflower is a globally important oilseed, food, and ornamental crop. This study seeks to investigate the genotoxic effects of tissue culture parameters in sunflower calli tissues belongs to two genotypes obtained via anther culture. Anthers were pretreated with cold for 24 hours at 4°C and heat for 2 days at 35°C in the dark and plated onto media supplemented with different concentrations and combinations of 6-benzylaminopurine, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, α-naphthalene acetic acid and indole-3-acetic acid. Obtaining calli tissues were used to detect the DNA damage levels by Comet assay, evaluating changes on superoxide dismutase and guaiacol peroxidase activities derived from in vitro culture factors. 0.5 mg/L 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and 2 mg/L α-naphthalene acetic acid from plant growth regulators showed acute genotoxic effect while 0.5 mg/L indole-3-acetic acid and 0.5 mg/L α-naphthalene acetic acid showed no genotoxic effect. Total protein content analysis of antioxidant enzymes revealed that although superoxide dismutase activity did not increase, Guaiacol peroxidase (GPOX) activity decreased in comparison to control. The obtained results have indicated that in vitro culture factors apparently lead to genotoxicity and oxidative stress.

KEYWORDS: Sunflower, anther culture, genotoxicity, comet assay, superoxide dismutase, guaiacol peroxidase

Introduction

Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) is one of the species belonging to Helianthus genus found in the family Compositae (Asteraceae) of Asterales.1,2 Sunflower is the fourth most important oilseed crop in the world in terms of total yearly production, after soybean, rapeseed, and groundnut. It is the fourth important oilseed crop which contributes 12% of the edible oil produced globally. The total sunflower achene consumption was 14.14 million metric tons as opposed to the total oilseed consumption of 178.4 million metric tons during the year 2015–2016.3,4

Studies which include raising the vegetable oil production, increasing the efficiency of breeding area or unit area and reducing the deficit of foreign currency in Turkey are very important in respect of economy and strategy. Classical breeding techniques used in sunflower agriculture involve in population breeding and selection, hybridization, backcross breeding, inbreeding, mutation breeding, genus and species hybrids, polyploidy breeding.5 The varieties obtained using traditional breeding methods are about to reach their upper limits of capacity of genetic productivity because of the use of the same gene source. Basis of biotechnological applications oriented towards sunflower breeding call for tissue culture studies. Therefore, the establishment of tissue culture systems has a great importance for genetic manipulation of sunflower in order to obtain agronomically important varieties.6 Anther culture is the one of haploid plant production methods in tissue culture applications. Anther culture of sunflower still faces numerous challenges; one of which is off-type of in vitro-derived sunflower plants, especially, when somatic embryogenesis and calli production are employed. In this frame, significant group of researchers identified different growth abnormalities such as somaclonal variations.7

As in other species, anther culture response of sunflower (Helianthus sp.) is strongly affected by physical, nutritional, physiological and genetical factors. In vitro culture factors apparently lead to oxidative stress and genotoxicity. In recent years, in vitro techniques have been extensively used not only in vitro screening in plants against abiotic stress but also creating in vitro models for studying and observing morphological, physiological and biochemical changes of both unorganized tissue levels against abiotic stresses. Plant tissue culture techniques are performed under aseptic and controlled environment using artificial media for growing and multiplication of explants. Because of these characteristics in vitro techniques, these techniques are suitable for researching both specific and common response to stress factors in plants. As it is known, oxidative stress is secondary effect of these factors and several techniques have been used to induce oxidative stress under tissue culture conditions.8 There are many reasons for the increased antioxidant enzyme activities under abiotic stresses induced with in vitro plant tissue culture techniques.9–14

The role of oxidative stress in morphogenesis in vitro has been examined in common ice plant (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L.).15 Calli differing in regeneration potential (i.e., rhizogenic or embryogenic) also differed in H2O2 content as well as in

SODs and CAT activities, suggesting the possible involvement of ROS in induction of different morphogenic pathways.16

Oxygen constitutes molecules called Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) that can react with other molecules during living functions of living aerobic cells and change the structures of the molecules they enter into the reaction. These molecules cause functional disorders in damaged tissues and organs that cells form.17 Stress conditions usually increase ROS production exceeding the cell antioxidant capacity, oxidative stress is likely to occur while ROS levels are tightly controlled by antioxidant systems in unstressed plants.18 Oxidative stress is one of the main reasons for spontaneous mutations in genome because of hyperactive ROS. Oxidative stress is also induced to be indirect effects of physical or chemical mutagens. The main effects of these mutagen, however, directly trigger DNA-lesions, such as transposons activation, inducing chromosome breakage and/or rearrangement, polyploidy, epigenetic variations, point mutations. Genotypic and phenotypic variations are created in the progeny of plants regenerated from plant tissue culture. If these variations are created in somatic cells or tissues, they are called somaclonal variations which are useful in crop improvement.19

Productions of ROS are controlled by two antioxidant defense systems as enzymatic and non-enzymatic. Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) and Peroxidase (POX) are found in enzymatic antioxidant system, both of which catalyze H2O2.20,21 H2O2 is not a free radical, but participates as an antioxidant or a reductant in several cellular metabolic pathways. H2O2 increased with oxidative stress, which encouraged us to study activities of SOD and POX. Many researchers reported that excess POX activities were measured in wide range of plant varieties under abiotic stress conditions induced with in vitro techniques. POX also break up indole-3- acetic acid (IAA) while it has a role in the biosynthesis of lignin and defense against biotic stresses by consuming H2O2 in the cytosol, vacuole, and cell wall as well as in extracellular space. Advanced-antioxidant defense systems play an important role in plants and they improve plants against these stresses while tolerating environmental stress.8

Oxidative stress also has great a potential to create variability in plant genome by activating transposons, inducing chromosome breakage/rearrangement and point mutation and these situations are one of the main reasons for spontaneous mutations which are one of the key factors of plant breeding.8 Higher plants are recognized as excellent indicators of cytogenetic and genotoxic effects of tissue culture parameters. There are many studies related to genotoxic effects of in vitro culture parameters especially plant growth regulators onto different plant species by many researchers.22–24,7,25–26

The Comet assay is one of the most commonly used in vitro and in vivo mutagenesis tests that analyze cell reaction to genotoxic agent and additionally a few biotic and abiotic stresses that prompt oxidative DNA damage. This assay is based on the quantification of denatured DNA fragments migrating out of the cell nucleus during electrophoresis and highly useful tool for measuring DNA damage in cells which is widely used in fields ranging from molecular epidemiology to genetic toxicology.24,27 Comet assay is an important method that can be applied on fungi, algae, theoretically all higher plants, sea creatures, insects, vertebrates and humans, both in terms of following with environmental health and informing about the defense potentials of the target organisms and their future health status.28–31

In this study, it was evaluated that the changes on genotoxicity and antioxidant enzyme activities total protein content derived from androgenic calli tissues with the effect of plant growth regulators, genotypes and pretreatments in sunflower. Evaluating the genotoxicity and antioxidant defence system in sunflower could help determine whether this cultivars are adapted for growth under in vitro culture conditions.

Materials and methods

Anther culture

After testing for genotypic response two different field grown interspecific hybrids have been selected as donor plants for anther culture. The flower buds were stored at +4°C for 24 hours to study the effect of cold pretreatment before culture. Likewise, for studying the effect of heat pretreatment flower buds were stored at + 35°C for 2 days after culture. The flower buds were surface sterilized by immersing in 3% Tween20 solution for 5 minutes followed by 1% bleach solution for 15 minutes and three rinses in sterile distilled water.32 The anthers which were at the mid- to late uniuncleate stage were excised under a stereo binocular microscope. All extraneous materials like papillae were removed. Anthers of two sunflower cultivars in the stage of uninucleate microspores were placed on four different culture MS33 media (pH 5.8) supplemented with basic MS macro and micro salts, 3% (w/v) sucrose, 0.2%(w/v) phytagel and varying concentration of plant growth regulators [0,5 mg/L NAA+0,5 mg/L BAP (A1); 0,5 mg/L 2,4D+ 0,5 mg/L BAP (A2); 0,5 mg/L IAA+0,5 mg/L BAP (A3) and 2 mg/L NAA+1 mg/L BAP (A4)]. Semi-solid MS medium supplemented with 0.5 mg/L Kinetin and 1 g/L PVP was used as regeneration medium. The cultures were incubated in the light a 16/8 photoperiod at 25 ± 1°C in plant growth cabinet. After one month in culture, calli tissues and regenerants were transferred to regeneration medium. Sub culturing was performed per month and all experiments were repeated three times.

Comet assay

Comet assay was performed following the method described by Çavaş and Könen,34with a few minor modifications. Leaf of sunflower grown in MS medium used as a negative control while leaf grown in MS medium supplemented with 150 µm AlCl3 for two weeks was used as a positive control and calli tissues obtained from anther culture studies were used as treatment group material. The nuclei were isolated from calli by careful slicing with a razor blade in 0.4 M Tris- HCl buffer (pH = 7.5) on ice in the dark. The mixture was passed through a filter with a pore diameter of 20 µm to remove the debris and large colonies and was waited on ice for 10 minutes. All steps were performed in dim light and ice to prevent induction of DNA damage. 100 µl of nuclei suspension was mixed with the 100 µl of 0.65% liquid low melting agarose (LMA) (1:1) by gently pipetting. As soon as 100 μl agarose/nuclei mixture were spread on the slide that are previously coated with 0.65% high melting agarose (HMA). The slides were covered with coverslip and coverslips were carefully removed from slides after 10 minutes at + 4°C to freeze the LMA. The slides were incubated in electrophoresis buffer (300 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA, pH>13) for 15 minutes to facilitate DNA unwinding. The slides were then placed on horizontal electrophoresis tank filled with freshly cold electrophoresis buffer, followed by performing electrophoresis for 30 minutes at 26 V, 300 mA at 4°C. Neutralization was carried out in cold Tris-HCl buffer changed for 3 times in every 5 minutes. Each slides was stained with 80 μl of ethidium bromide (1:4 EtBr: distilled water) and kept at 4°C until analysis. The slides were analyzed under a fluorescent microscope at 20X magnification. For each sample, 50 random cells were scored. Comet parameters were measured and analyzed using CAMERAM software. The % tail DNA and olive tail momentum parameters were calculated as a measure of DNA damage of 50 comets. % Tail DNA values were shown as the percentage of DNA in Comet tail. Olive tail moment values were shown as multiplication of % tail DNA and difference between center of gravity of DNA in the tail and center of gravity of the head DNA. Each independent experimental group were evaluated with each providing a median value of %DNA in tail and olive tail moment.

Determination of total protein content

The total protein content was measured according to Bradford.35 The calli tissue (0,1) g was homogenized in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH = 7.8) containing 0.1 mM EDTA, 1% (w/v) PVP, and 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 with a chilled mortar and pestle with a ratio of 1 g/3 mL buffer.36 The homogenates were centrifuged at 18,000 g for 20 minutes at 4◦C. The reaction mixture including Bradford reagent (5 mL) and supernatant (100 μL) were measured at 590 nm spectrophotometrically. A standard curve was constituted with a series of dilutions of bovine serum albumin (BSA). The obtained supernatant was collected for the determination of total protein content and antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD and POD).

Determination of guaiacol peroxidase activity

Guaiacol peroxidase (GPOX) activity activity was determined according to Birecka et al.37 The homogenates were centrifuged at 11,000 rpm for 25 min at 4◦C. The reaction mixture included 10 μL supernatant, phosphate-saline buffer (pH 5.8), 15 mM guaiacol and 5 mM H2O2. GPOX activity was measured for 2 min at 470 nm, spectrophotometrically. Enzyme specific activity is expressed as μmol of H2O2 reduced min−1(mg protein)−1. Each application was repeated at least 3 times.

Determination of superoxide dismutase activity

The superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was determined according to Giannopolitis and Ries,38 which is ment to analyse the inhibition of the photochemical reduction of nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT), 2 μl of the supernatant and 20 μl 0.2 mM riboflavin were mixed with 2 ml 100 mM phosphate buffer containing 50 mM sodium carbonate, 100 μM EDTA, 13 μM L-methionine and 75 μM NBT. The homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. The reaction mixtures were kept under white fluorescent lamps (15W) for 10 min and measured at 560 nm. One unit of SOD is defined as the amount required inhibiting the photo reduction of nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) by 50%.

Statistical analyses were performed by using Multivariate test of General Linear Model in SPSS Statistics 21 program taking P < .05 as significance.

Results

Anther culture

It was determined that calli tissues began to develop on anthers at the end of the first week. Some of these calli are in embryogenic form while others had a compact, flat calli structure. Embryogenic calli are globular embryoids with a dispersed, whitish structure, whereas non-embryogenic calli are compact or spongy. The number of callus, embryogenic calli, presence of regeneration, percentage callus and percentage embryogenic callus parameters were evaluated to determine the effect of individual genotypes on androgenesis with different pretreatments and media.

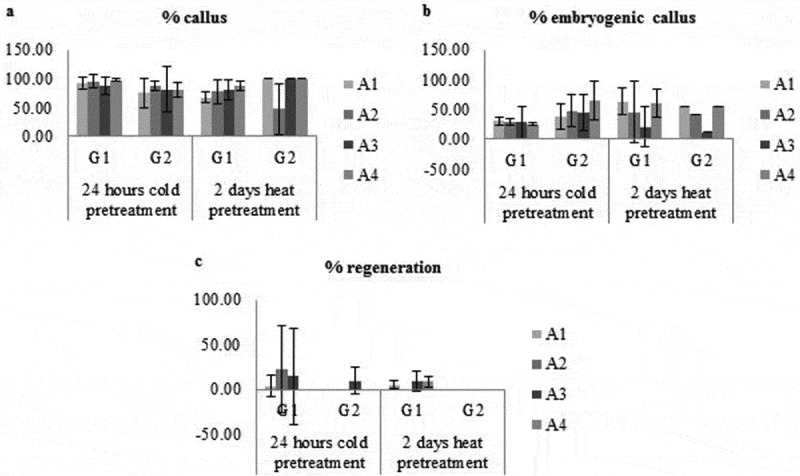

It was observed that the percentage of embryogenic calli ranged from 65% to 26%, while the percentage of callus-forming anthers varied between 95% and 75% given the effect of 24-hour cold treatment with different genotypes and media. The regeneration percentage was ranged from 10% to 6%. The percentage of embryogenic callus ranged from 66% to 42%, while the percentage of callus-forming anthers varied between 100% and 48%. The effect of 2-day heat treatment with different genotypes and media taking into account, the regeneration percentage ranged from 23% to 4%. The best callus induction result (100%) was obtained from G2 genotype with 2-day heat pretreatment in A1, A3 and A4 medium while the best embryogenic callus induction (65%) was obtained from G2 genotype with 24 – hours cold pretreatment inA4 medium. Best regeneration (23%) was obtained from G1 genotype with 24 – hours cold pretreatment in A2 medium (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of genotype, medium type and pretreatment on percentage of callus (a), embryogenic callus (b) and regeneration (c).

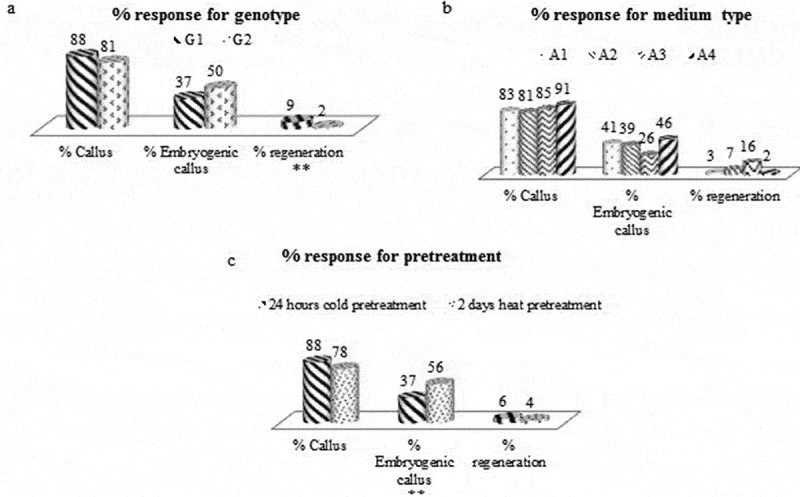

Effect of genotype

In total, 424 calli (88%) were produced from 480 anthers, 158 embryogenic calli (37%) produced from these calli and 14 regenerations (9%) were obtained from the embryogenic calli placed on nutrient media for G1 genotype. The percentage of anthers forming calli, embryogenic calli and regeneration were 81%, 50%, and 2% respectively for G2 genotype (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Obtained % callus, embryogenic callus and regeneration ratio for genotype (a), medium type (b) and pretreatment (c) (** = significant differences at p < 0.05).

Effect of medium type

In total, 166 calli (83%) were produced from 200 anthers, 68 embryogenic calli (41%) produced from these calli and 2 regenerations (3%) were obtained from these embryogenic calli placed on nutrient media for A1 medium. For A2 medium, 220 anthers were planted, 179 of which callus, 69 of which were embryogenic; 5 of these embryogenic calli were regenerated. In this case, the percentage of anthers forming calli, embryogenic calli and regeneration were 81%, 39%, and 7% respectively. For A3 medium, 220 anthers were planted, 188 of which were callus, 49 of which were embryogenic; 8 of these embryogenic callus were regenerated. In this case, the percentage of anthers forming callus is 85%, the percentage of embryogenic callus is 26%, and the percentage of regeneration is 16%. In total, 182 calli (91%) were produced from 200 anthers, 84 embryogenic calli (46%) produced from these calli and 2 regenerations (2%) were obtained from these embryogenic calli placed on nutrient media for A4 medium (Figure 2B).

Effect of pretreatment

The efficiency of pretreatment for 24 hours at +4°C were evaluated, using 580 anthers. 511 of these anthers produced callus, 188 of these calli were embryogenic and 12 of the embryogenic callus were regenerated. In this case, the percentage of anthers forming calli, embryogenic calli and regeneration were 88%, 37%, and 6% respectively. In total, 260 anthers were planted while 204 of these anthers were callus, 115 of these calli were embryogenic, 5 of the embryogenic callus were regenerated for 2 days at 35°C. In this case, the percentage of anthers forming callus is 78%, the percentage of embryogenic callus is 56%, and the percentage of regeneration is 4% (Figure 2C).

Comet assay

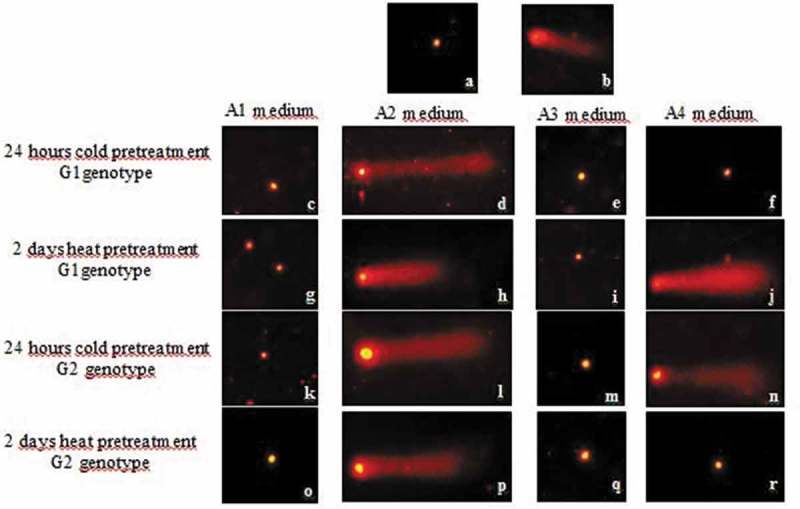

Comet formations that reflect DNA profiles migrating outside the nucleus and consisting of genotoxic damage were shown by fluorescence staining for sunflower anther cultures used as application groups and positive and negative controls. The obtained Comet images being examined, a distinct tail structure was observed in the positive control group, compared to the negative control (Figure 3). The visual Comet scores of all the results, which can be observed visually from the genotoxic damage that occurs in the different application groups with different contents, are given in Figure 3. In general, DNA damage was observed on A2 and A4 medium. The obtained images were analyzed with the aid of the Cameram software and the results were evaluated according to tail % DNA and olive tail moment parameters, which provided a good correlation in genotoxicity studies.

Figure 3.

Fluorescence microscope images of DNA damage occurring in different applications and controls: negative control (a), positive control (b) and treatment groups (c-r).

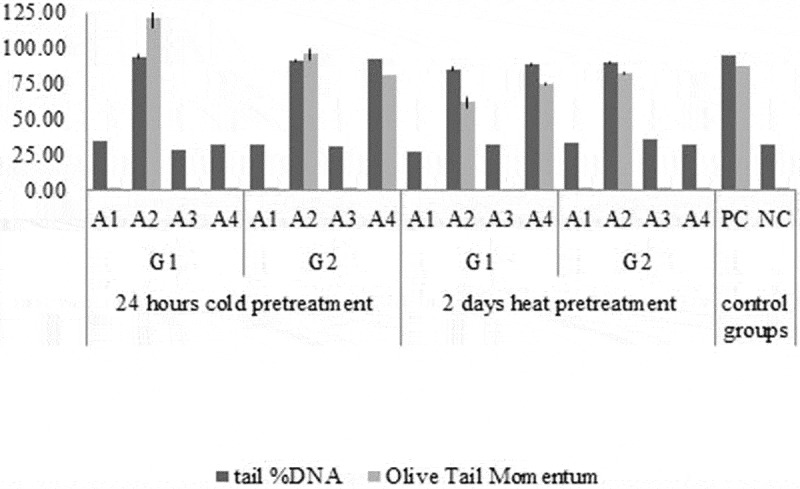

The highest tail % DNA result was obtained from G1 genotype with 24 -hour cold pretreatment in A2 medium. The highest olive tail momentum result was also obtained from G1 genotype with 24-hour cold pretreatment in A2 medium. The lowest tail % DNA result was obtained from G1 genotype with 2 -days heat pretreatment in A1 medium. Result of the lowest olive tail momentum was also obtained from G1 genotype with 2 -days heat pretreatment in A1 medium (Figure 4). The effect of genotype, medium composition and type of pretreatment on tail % DNA was discussed separately (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Tail % DNA and olive tail moment data results in analysis of Comet images obtained from sunflower callus.

Figure 5.

Tail % DNA and Olive tail momentum results in analysis of Comet images obtained from sunflower callus according to genotype, medium type and pretreatment (** = significant differences at p < 0.05).

Determination of total soluble protein and antioxidant enzyme activity

The total soluble protein levels and antioxidant enzyme activities parameters were evaluated to determine the effects of genotype, medium types and pretreatments on genotoxicity under in vitro tissue culture conditions. Our studies demonstrate that antioxidant enzyme activity and protein concentration is changed in various stress conditions using calli tissue as a material.

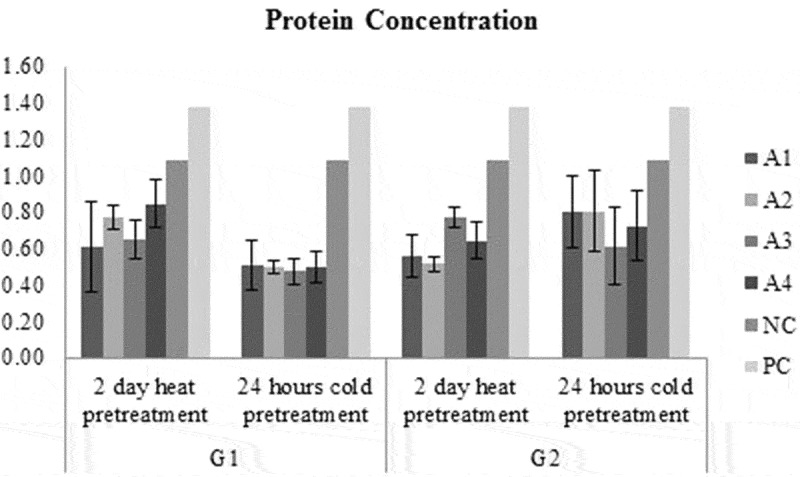

The highest protein concentration was obtained from G1 genotype 2 days heat pretreatment A4 medium while the lowest protein concentration was obtained from G1 genotype 24 hours cold pretreatment A3 medium (Figure 6). Protein concentration in G2 medium was higher than G1 genotype, regardless of medium and pretreatments. In A4 medium, protein concentration was the highest while in A1 medium was the lowest, regardless of genotype and pretreatments. The heat pretreatment was higher than 24- hours cold pretreatment in 2 days, regardless of medium and genotypes for total soluble protein concentration (Figure 9).

Figure 6.

Protein concentration of each treatment groups and control groups.

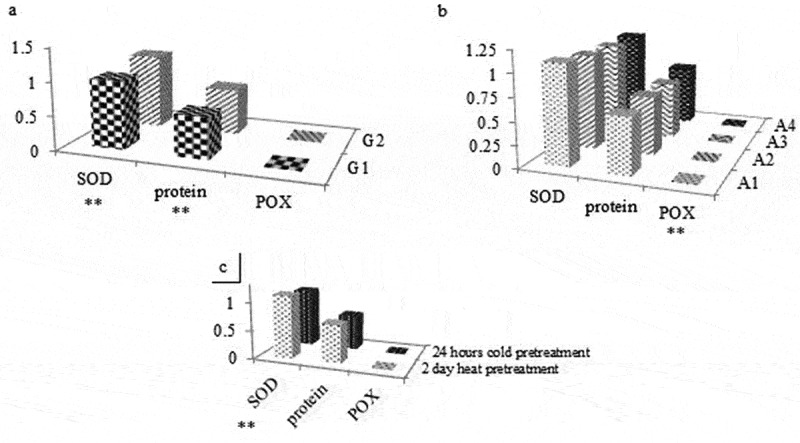

Figure 9.

Protein concentration, SOD and POX activity results according to genotype, medium type and pretreatment (** = significant differences at p < 0.05).

The antioxidant enzyme activities parameters were evaluated to determine the effects of genotype, medium types and pretreatments on genotoxicity under in vitro tissue culture conditions. Our studies demonstrate that antioxidant enzyme activity is changed in various stress conditions using calli tissues as material.

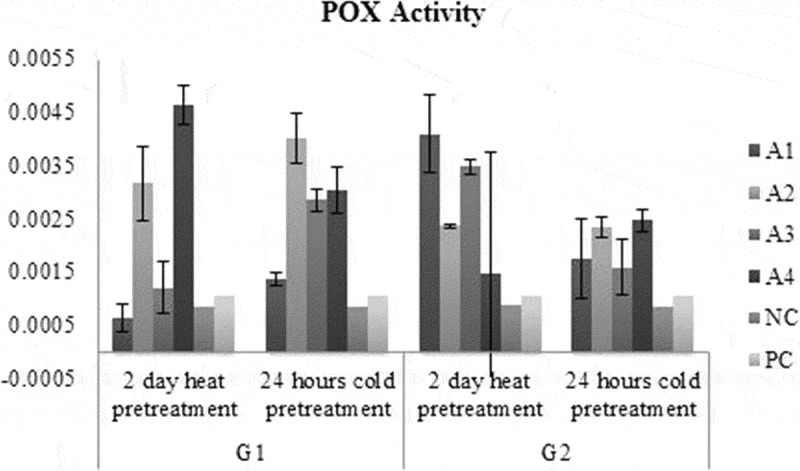

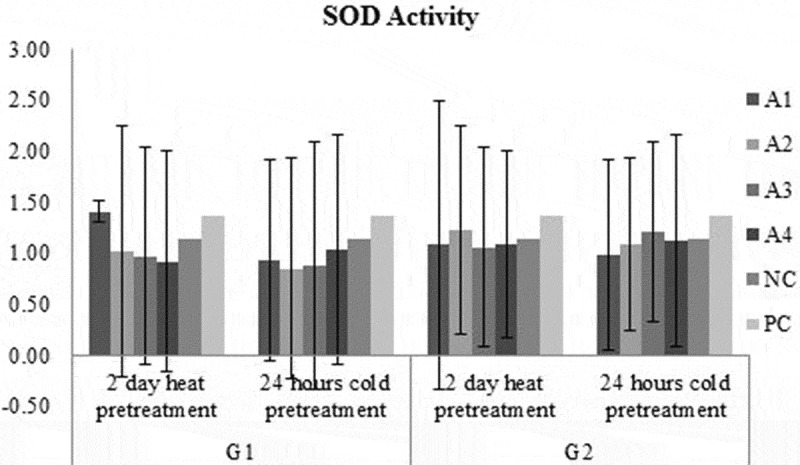

GPOX activity in A1 medium had the highest for G2 genotype in 2 days heat pretreatment while in A1 medium had the lowest activity for G1 genotype in 2 days heat pretreatment (Figure 8). GPOX activity in G1 medium was higher than G2 genotype regardless of medium and pretreatments (Figure 9). GPOX activity in A2 medium was the highest while in A1 medium was the lowest regardless of genotype and pretreatments (Figure 9). GPOX activity in 2 days heat pretreatment was higher than 2 days heat pretreatment regardless of medium and genotypes (Figure 9). Taking in the account the SOD activity in A1 medium had the highest activity for G1 genotype in 2 days heat pretreatment while in A1 medium has the lowest for G1 genotype with 24 hours cold pretreatment (Figure 7). SOD activity in G2 medium was higher than G1 genotype, regardless of medium and pretreatments. SOD activity in A1 medium was the highest while in A3 medium was the lowest, regardless of genotype and pretreatments. SOD activity in 2 days heat pretreatment was higher than 2 days heat pretreatment, regardless of medium and genotypes (Figure 9). Activity of SOD did not show an increase while activity of GPOX was increased by plant growth regulators compared to negative control.

Figure 8.

POX activity results of each treatment and control groups.

Figure 7.

SOD activity results of each treatment groups and control groups.

Statistical analysis

The genotype was an effective parameter on % regeneration (P: 0,045), SOD activity (P: 0,008), tail % DNA (P < .001) and olive tail momentum (P: 0,003) parameters. The medium type was an effective parameter on GPOX activity (P: 0,003), tail % DNA (P < .001) and olive tail momentum (P < 0,001) parameters. The pretreatment was an effective parameter on % embryogenic calli (P: 0,014), SOD activity (P: 0,033), tail % DNA (P < .001) and olive tail momentum (P < 0,001) parameters.

Discussion

There are many anther culture studies that have investigated to the effect of genotype, medium type and pretreatments. In these studies, carried out by many researchers, it is emphasized that the genotype is the controlling factor in many stages, such as anther calli formation,39,40 embryoid formation41 and plant regeneration.42,43 In a study by Thengane et al.,44 4 different sunflower genotypes were used and the highest calli and embryogenic calli ratios were obtained in the Russian variety. In anther culture study of, 20 different sunflower hybrids were used, but only three of which plant could be obtained Nenova et al.45 Based on the results of these studies, genotype has been determined to be effective in formation rate of callus. This may be explained by the amount of internal hormones contained in different genotypes as well as by the genetic predisposition to hybridization.32 But the effect of genotype could not be determined effectively because of only two genotypes were used in our study.

Many publications have focused on the use of auxin and cytokine on haploid calli and embryo development.46–48 A study by Nenova,49 using Helianthus hybrids (H. annuus x H. smithii, H. annuus x H. eggertii), the most effective plant regulator combination was found to be 0.5 mg/l NAA and 0.5 mg/l BAP. Likewise, Jonard and Mezarobba50 obtained the most effective result from the same growth regulator combination in 1990 with wild Helianthus hybrids. Similarly, it has been determined that 2 mg/L NAA and 1 mg/L BAP is the most effective combination in our study. In 1985, Bohorova et al.51 reported that in a study with 24 different combinations of growth regulator and IAA containing nutrient medium, 70–100% of the anthers were in the form of granular embryogenic calli. In our study, it has also been observed that the calli structure developed from the IAA plant growth regulator-containing A3 nutrient medium is compact.

It was reported by Jonard and Mezzarobba (1990)50 that 32–35°C hot pretreatment was suitable for anther culture. According to Sunderland et al.,52 cold pretreatment throw over tapetum and pollen porosity by promoting aging in the anther tissue. This prevents regeneration derived from vegetative origin. According to Tukey test; however, pretreatment type was not an effective parameter for % regeneration ratio (P:0.189). In another study, it was indicated that preliminary application at + 4°C was not very effective in calli formation but it was an effective factor in embryogenesis.32 In contrast, cold pretreatment was not an effective factor in embryogenesis in our study. We observed that heat pretreatment is more effective than cold pretreatment for embryogenesis.

Saji and Sujatha,32 reported in an anther culture study with sunflower that trunk development was only in the nutrient medium with 0.5 mg/l BAP content. In a study by Priya et al.,53 the effects of different concentrations of BAP and kinetin on regeneration were investigated and it was stated that BAP-containing nutrient media were more effective and that rooting occurred when concentration was lowered. Akgül,54 reported that the nutrient medium containing kinetin (0,1 mg/L) was more suitable because of the vitrification structure of the regenerations that developed in nutrient media containing BAP (0,5 mg/L). In this study, 0.1mg/L kinetin was used as regeneration medium and then the kinetin concentration was increased to 0.5 mg/L.

In vitro culture factors could apparently lead to oxidative stress and genotoxicity. In recent years, in vitro techniques have been extensively used not only in vitro screening in plants against abiotic stress but also to creative in vitro models for studying and observing morphological, physiological and biochemical changes of both unorganized tissue levels against abiotic stresses.8 There are many studies related to genotoxic effects and oxidative stress of in vitro culture parameters onto different plant species by many researchers.

In one study, for instance, Koppen and Cerda,55 performed irradiation with a 60Co gamma source onto dry soya beans, lentil, sunflower, sesame and linseed seeds. They used Comet assay to identify seeds irradiated with low doses of 60 Co gamma and they found that all the samples could be identified by either means, including the one irradiated with 25 Gy. Bibi et al.,26 employed V. dahliae (Vd) toxin as pathogen-free model system to induce stress on cotton calli growth, and its amelioration was investigated using 24-epibrassinolide (EBR). Vd toxin alone caused the degradation of DNA and tail moments of the Comet were more frequent. In a study by De Arcaute et al.,25 genotoxicity of the 54.8% 2,4-D-based commercial herbicide were assayed on Cnesterodon decemmaculatus by using Comet assay. Researchers found that exposure to 2,4-D with in the 252–756 mg/L range increased the genetic damage index in treatments lasting for either 48 and 96h. Many studies have shown that 2.4-D has genotoxic potential by using different test systems.56–58 Several researchers reported that 2,4-D has cytogenetic effects, including chromosome abnormalities in the meiosis of barley and Vicia faba and sister chromatid exchanges in cultured immature embryos of wheat species.59 Özkul et al.,24 investigated cytogenetic effects of different concentrations of 2,4-D (0.67, 1.34, 2.01, 2.68, 3.35 and 4.02 mg/L) on Allium cepa bulblet’s root tips treated for 24 and 48 h. In this study, they reported that 2,4-D treatment after 48-h, significantly decreased mitotic index at the highest concentrations as confirmed cytologically and by Comet test. Results determined that there is a negative cytogenetic effect of 4.02 mg/L 2,4-D for 48 h treatment in plant tissue culture studies. In our study, it was determined that there is acute genotoxic effects of 2.4 D (0.5mg/L) and NAA (2 mg/L) from plant growth regulators by Comet assay with calli from in vitro anther culture.

Plants produce oxine and cytokine in their own tissues. These hormones can reach high doses in plants by supplementing these plant growth regulators from outside in plant tissue culture studies. The production of auxin and cytokine may be distinct in plants for different gene sources. In our study, there was genotoxic effect in 24 hours cold pretreated G2 genotype in A4 medium while there is no genotoxic effect in 24 hours cold pretreated G1 genotype in A4 medium. In contrast to this, there was genotoxic effect in 2 days heat pretreatment G1 genotype in A4 medium while there is no genotoxic effect in 24 hours cold pretreated G1 genotype in A4 medium. There was genotoxic effect in 24 hours cold pretreat G2 genotype in A4 medium while there was no genotoxic effect in 2 days heat pretreated G2 genotype in A4 medium. All the results mentioned above shared the effects of genotype based on response, medium types and pretreatments.

There are studies demonstrating that antioxidant enzyme activity changed in various stress conditions using callus or other plant tissues as material, in a similar way to our study. Hassanpour et al.,13 researched the effect of high-frequency vibration on growth rate, membrane stability and activities of some antioxidant enzymes in callus tissues of Hyoscyamus kurdicus. Results showed that sinusoidal vibration significantly increased the protein and proline contents and activity of SOD, ascorbate peroxidase (APOX) and POX enzymes, and decreased total carbohydrate, H2O2

Level and CAT activity, compared to control. In a study by Helaly et al.,14 the effects of Polyethylene glycol (PEG) on embryo growth and development in date palm cell suspension culture and associated antioxidant enzyme activities were evaluated. Results showed that total soluble protein (TSP), proline, glycine betaine (GB), total soluble phenol (TSPh), total sugars (TS), and total soluble organic acids (TOA) also increased whereas SOD activity decreased in response to PEG supplementation. Alharby et al.,11 shows that tomato plant tissues (callus) upregulate antioxidant enzymes SOD and GPOX in an attempt to offset the metabolic effects of salt stress. In other study conducted by Nejadalimoradi et al.,10 the effect of salt stress on CAT, GPOX and APOX in leaves and roots of sunflower plant either with or without pretreatment was assayed. The results showed that in plants under salt stress, sodium nitroprusside (SNP) pretreatment could increase the activity of CAT, GPOX and APOX enzymes in root and leaves of plants while Arg pretreatment increased the activity of CAT and APOX in roots and leaves of plants and had no significant effects on GPOX activity when compared with non-pretreated plants. Alhasnawi et al.,12 researched the influence of exogenous ascorbic acid on the embryogenic callus of indica rice cultivated under saline conditions. They showed that activities of peroxidase, catalase, superoxide dismutase, as well as content of proline increased due to the NaCl treatment, and these parameters were mostly further increased by 0.5 mM AsA. Jabeen and Ahmad,9 studied the growth and the generation and scavenging of ROS under normal and salt stress conditions in relation to the priming of seeds of safflower and sunflower, with different concentrations of chitosan. Results demostrated that CAT and POX activity were increased by low concentrations of chitosan. With increasing salt stress, low concentrations of chitosan increased germination percentage but decreased malondialdehyde and proline contents and CAT and POX activity. In our study; results of POX activity were the highest for A4 medium, 2 days heat pretreatment G1 genotype according to other medium types. The result of SOD activity was the highest for 2 days heat pretreated G2 genotype in A2 medium. Results of POX activity were the highest for 2 days-heat pretreated G1 genotype in A4 medium, 24 hours cold pretreated G1 genotype in A2 medium and 24 hours cold pretreated G2 genotype in A4 medium compared to other medium types. The SOD and GPOX activity could be increased correspondingly with genotoxicity.

In conclusion; 2.4 D (0.5 mg/L) and NAA (2 mg/L) from plant growth regulators, an important factor in sunflower plant tissue culture, could be a chemical agent with acute genotoxic effect in plants by causing DNA damage while IAA (0.5 mg/L) and NAA (0.5 mg/L) has no genotoxic effects. These plant growth regulators can be used for in vitro plant tissue culture studies in future studies. Medium type can be cited as the most effective parameter in this study while the effects of genotype, medium type and pretreatment are observed in all the results. Overall results indicated that in vitro culture factors especially plant growth regulators could apparently lead to genotoxicity and oxidative stress. Sunflower callus tissue was also used for the first time in this study for Comet assay and antioxidant enzyme activity. Long-term genotoxicity studies can be an important approach to gaining insight into organism’s ability to repair DNA and other protective mechanisms.60 The findings further underscored that the appropriate dose ranges of media composition and pretreatment conditions were important for induction of genotoxic adaptation in plant cells. The findings have implications in inducible plant adaptation to hostile environments in the long run.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly acknowledge to Dr. Göksel Evci from Trakya Agricultural Research Institute (Edirne, Turkey) for providing plant material. This research has been supported by TUBITAK-TOVAG 1001 (Project No: 214O274) and Marmara University Research Foundation (Project No: FENC-YLP-200716-0382).

References

- 1.Berglund DR. Sunflower production. North Dakota State University Ext. Serv. Bulletin A-1331 (EB-25 Revised), 2007. (verified 31.12. 11) http://www.ag.ndsu.edu/pubs/plantsci/rowcrops/a1331intro.pdf.

- 2.Hu J. Genetics, genomics and breeding of sunflower In: Hu J, Seiler G, Kole C, editors. Genetics. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaya Y, Balalic I, Miklic V. Eastern Europe perspectives on sunflower production and processing, in sunflower: chemistry, production, processing, and utilization In: Dunford N, Force EM, editors. Urbana: American Oil Chemists Society; 2016. p. 575–638. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rauf S, Jamil N, Ali Tariq S, Khan M, Kausar M, Kaya Y. Progress in modification of sunflower oil to expand its industrial value. J Sci Food Agric. 2017;97:1997–2006. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dayan S. History of in vitro culture studies on Helianthus Annuus L. in Turkey. Trakya Uni J Natural Sci. 2016;17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nestares G, Zorzoli R, Mroginski L, Picardi L. Heritability of in vitro plant regeneration capacity in sunflower. Plant Breed. 2002;121(4):366–368. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0523.2002.727109.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abass MH, Al-Utbi SD, Al-Samir EA. Genotoxicity assessment of high concentrations of 2, 4-D, NAA and Dicamba on date palm callus (Phoenix dactylifera L.) using protein profile and RAPD markers. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jgeb.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Şen A. Oxidative stress studies in plant tissue culture. Antioxidant Enzyme. 2012;3:59–88. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jabeen N, Ahmad R. The activity of antioxidant enzymes in response to salt stress in safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) and sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) seedlings raised from seed treated with chitosan. J Sci Food Agric. 2013;93(7):1699–1705. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nejadalimoradi HAVVA, Nasibi FATEMEH, Kalantari KM, Zanganeh ROYA. Effect of seed priming with L-arginine and sodium nitroprusside on some physiological parameters and antioxidant enzymes of sunflower plants exposed to salt stress. Agric Commun. 2014;2:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alharby HF, Metwali EM, Fuller MP, Aldhebiani AY. Impact of application of zinc oxide nanoparticles on callus induction, plant regeneration, element content and antioxidant enzyme activity in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum Mill.) under salt stress. Arch Biol Sci. 2016;68(4):723–735. doi: 10.2298/ABS151105017A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alhasnawi AN, Radziah CC, Kadhimi AA, Isahak A, Mohamad A, Yusoff WMW. Enhancement of antioxidant enzyme activities in rice callus by ascorbic acid under salinity stress. Biologia Plantarum. 2016;60(4):783–787. doi: 10.1007/s10535-016-0603-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassanpour H, Niknam V, Haddadi BS. High-frequency vibration improve callus growth via antioxidant enzymes induction in Hyoscyamus kurdicus. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2017;128(1):231–241. doi: 10.1007/s11240-016-1103-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helaly MN, El-Hosieny HA, El-Sarkassy NM, Fuller MP. Growth, lipid peroxidation, organic solutes, and anti-oxidative enzyme content in drought-stressed date palm embryogenic callus suspension induced by polyethylene glycol. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2017;53(2):133–141. doi: 10.1007/s11627-017-9815-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Libik-Konieczny M, Konieczny R, Suro´wka E, S´ Lesak I, Michalec Z, Rozpa˛dek P, Miszalski Z. Pathways of ROS homeostasis regulation in Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L. calli exhibiting differences in rhizogenesis. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2012;110:123–131. doi: 10.1007/s11240-012-0136-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Libik M, Konieczny R, Pater B, S´ Lesak I, Miszalski Z. Differences in the activities of some antioxidant enzymes and H2O2 content during rhizogenesis and somatic embryogenesis in callus cultures of the ice plant. Plant Cell Rep. 2005;23:834–841. doi: 10.1007/s00299-004-0886-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kehourer J, Lund L. Cellular reducing equivalents and oxidative stress. Free Radical Biol Med. 1994;17:65–75. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarwat M, Ahmad A, Abdin MZ, Ibrahim MM Eds.. Stress signaling in plants: genomics and proteomics perspective (Vol. 2). Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joyce SM, Cassells AC, Jain SM. Stress and aberrant phenotypes in vitro culture. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2003;74(2):103–121. doi: 10.1023/A:1023911927116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill SS, Tuteja N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48:909–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karuppanapandian T, Moon JH, Kim C, Manoharan K, Kim W. Reactive oxygen species in plants: their generation, signal transduction, and scavenging mechanisms. Australian J Crop Sci. 2011;5:709–725. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aksakal O, Erturk FA, Sunar S, Bozari S, Agar G. Assessment of genotoxic effects of 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid on maize by using RAPD analysis. Ind Crops Prod. 2013;42:552–557. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.06.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwasniewska J, Grabowska M, Kwasniewski M, Kolano B. Comet‐FISH with rDNA probes for the analysis of mutagen‐induced DNA damage in plant cells. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2012;53(5):369–375. doi: 10.1002/em.21699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Özkul M, Özel ÇA, Yüzbaşıoğlu D, Ünal F. Does 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2, 4-D) induce genotoxic effects in tissue cultured Allium roots? Cytotechnology. 2016;68(6):2395–2405. doi: 10.1007/s10616-016-9956-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Arcaute CR, Soloneski S, Larramendy ML. Toxic and genotoxic effects of the 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2, 4-D)-based herbicide on the Neotropical fish Cnesterodon decemmaculatus. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2016;128:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bibi N, Ahmed IM, Fan K, Dawood M, Li F, Yuan S, Wang X. Role of brassinosteroids in alleviating toxin-induced stress of Verticillium dahliae on cotton callus growth. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;24(13):12281–12292. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-8738-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang F, Zhang Q, Guo H, Zhang S. Evaluation of cytotoxicity, genotoxicity and teratogenicity of marine sediments from Qingdao coastal areas using in vitro fish cell assay, Comet assay and zebrafish embryo test. Toxicol in Vitro. 2010;24(7):2003–2011. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gichner T, Plewa MJ. Induction of somatic DNA damage as measured by single cell gel electrophoresis and point mutation in leaves of tobacco plants. Mutat Res/Fund Mol Mech Mutagen. 1998;401(1):143–152. doi: 10.1016/S0027-5107(98)00003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angelis KJ, McGuffie M, Menke M, Schubert I. Adaptation to alkylation damage in DNA measured by the Comet assay. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2000;36:146–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menke M, Meister A, Schubert I. N-Methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced DNA damage detected by the Comet assay in Vicia faba nuclei during all interphase stages is not restricted to chouromatid aberration hot spots. Mutagenesis. 2000;15(6):503–506. doi: 10.1093/mutage/15.6.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhawan A, Bajpayee M, Parmar D. Comet assay: a reliable tool for the assessment of DNA damage in different models. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2009;25(1):5–32. doi: 10.1007/s10565-008-9072-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saji KV, Sujatha M. Embryogenesis and plant regeneration in anther culture of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Euphytica. 1998;103:1–7. doi: 10.1023/A:1018318625718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plantarum. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Çavaş T, Könen S. Detection of cytogenetic and DNA damage in peripheral erythourocytes of goldfish (Carassius auratus) exposed to a glyphosate formulation using the micronucleus test and the Comet assay. Mutagenesis. 2007;22(4):263–268. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gem012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee DH, Lee CB. Chilling stress-induced changes of antioxidant enzymes in the leaves of cucumber: in gel enzyme activity assays. Plant Sci. 2000;159:75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birecka H, Briber KA, Catalfamo JL. Comparative studies on tobacco pith and sweet potato root isoperoxidases in relation to injury, indoleacetic acid, and ethylene effects. Plant Physiol. 1973;52(1):43–49. doi: 10.1104/pp.52.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giannopolitis CN, Ries SK. Superoxide Dismutase, I. Occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 1977;59:309–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rines HW. Oat anther culture: genotype effects on callus initiation and the production of a haploid plant. Crop Sci. 1983;23(2):268–272. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1983.0011183X002300020022x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miah MAA, Earle ED, Khush GS. Inheritance of callus formation ability in anther cultures of rice, Oryza sativa L. Theor Appl Genet. 1985;70(2):113–116. doi: 10.1007/BF00275308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown DC, Atanassov A. Role of genetic background in somatic embryogenesis in Medicago. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1985;4(2):111–122. doi: 10.1007/BF00042269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma G, Bello L, Sapru T. Genotypic differences in organogenesis from callus of ten triticale lines. Euphytica. 1980;29:751–754. doi: 10.1007/BF00023222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurtz S, Linberger R. Genotypic differences in morphogenic capacity of cultured leaf explants of tomato. J Am Soe Hort Sci. 1983;108:710–714. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thengane SR, Joshi MS, Khuspe SS, Mascarenhas AF. Anther culture in Helianthus annuus L., influence of genotype and culture conditions on embryo induction and plant regeneration. Plant Cell Rep. 1994;13:222–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00239897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nenova N, Cristov M, Ivanov P. Anther culture regeneration from some wild Helianthus species. Helia. 2000;23:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maheshwari S, Rashid A, Tyage A. Haploid from polen grains-retrospect and prospect. Am J Bot. 1982;69:865–879. doi: 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1982.tb13330.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chien YC, Kao KN. Effects of osmolality, cytokinin, and organic acids on pollen callus formation in Triticale anthers. Can J Bot. 1983;61(3):639–641. doi: 10.1139/b83-072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chu C, Hill R, Brule-Babel A. High frequency of pollen embryoid formation and plant regeneration in Triticum aestivum L. on monosaccharide containing media. Plant Sci. 1990;66:255–262. doi: 10.1016/0168-9452(90)90211-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nenova N, Ivanov P, Chouristov M. Anther culture regeneration of Fl hybrids of Helianthus annuus X Helianthus smithii and HelianthusaAnnuus X Helianthus eggertii. Proc. 13th International Sunflower Conference; 1992, p. 1509–1514; Pisa. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jonard R, Mezzarobba A. Sunflower (Helianthus spp.): anther culture and field studies on haploids In: Legumes and oilseed crops I. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 1990. p. 485–501. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bohorova NE, Atanassov A, Georgieva-Todorova J. In vitro organogenesis, androgenesis and embryo-culture in the genus Helianthus L. Z. Pflanzenztichtg. 1985;95:34–44. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sunderland N, Huang B, Hills GJ. Disposition of pollen in situ and its relevance to anther/pollen culture. J Exp Bot. 1984;35(4):521–530. doi: 10.1093/jxb/35.4.521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Priya Vijaya K, Sassikumar D, Sudhagar R, Gopalan A. Androgenetıc response of sunflower in dıfferent culture environments. Helıa. 2003;38:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Akgül N. Ayçiçeğinde (Helianthus annuus L.) in vitro koşullarda androgenik embriyo ve organ rejenerasyonu. Marmara Universitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü. 2016;7–21. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koppen G, Cerda H. Identification of low-dose irradiated seeds using the neutral Comet assay. LWT Food Sci Technol. 1997;30(5):452–457. doi: 10.1006/fstl.1996.0205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arias E. Sister chromatid exchange induction by the herbicide 2,4- dichlorophenoxyacetic acid in chick embryos. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2003;55:338–343. doi: 10.1016/S0147-6513(02)00131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gonzalez M, Soloneski S, Reigosa MA, Larramendy ML. Genotoxicity of the herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and a commercial formulation, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid dimethylamine salt I. Evaluation of DNA damage and cytogenic endpoints in Chinese Hamster ovary (CHO) cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 2005;19:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soloneski S, González NV, Reigosa MA, Larramendy ML. Herbicide 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2, 4-D)-induced cytogenetic damage in human lymphocytes in vitro in presence of erythourocytes. Cell Biol Int. 2007;31(11):1316–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Amer SM, Ali FAE. Genotoxic effects of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and its metabolite 2,4-dichlorophenol in mouse. Mutat Res. 2001;494:1–12. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5718(01)00146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ali D, Kumar S. Long-term genotoxic effect of monocrotophos in different tissues of freshwater fish Channa punctatus (Bloch) using alkaline single cell gel electrophoresis. Sci Total Environ. 2008;405(1):345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Berglund DR. Sunflower production. North Dakota State University Ext. Serv. Bulletin A-1331 (EB-25 Revised), 2007. (verified 31.12. 11) http://www.ag.ndsu.edu/pubs/plantsci/rowcrops/a1331intro.pdf.