Abstract

Patients with AIDS have increased risk of developing lymphomas, such as anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), which generally carry a poor prognosis. The DUSP-IRF4 genetic rearrangement in ALCL confers a favourable prognosis in HIV-negative patients; it is unknown how this interacts clinically with HIV/AIDS. A man aged 53 years presented with subcutaneous nodules on the scalp and axillae, and diffuse lymphadenopathy. Biopsy of subcutaneous nodule and lymph node showed large atypical anaplastic lymphocytes which were CD30+ and anaplastic lymphoma kinase-negative, consistent with primary systemic ALCL. In addition, he was found to be HIV-positive and diagnosed with AIDS. Genetic testing of the tissue revealed a DUSP22-IRF4 rearrangement. Complete remission was achieved with HyperCVAD and subsequent brentuximab vedotin monotherapy. We report a case of AIDS-associated primary systemic ALCL with a DUSP22-IRF4 rearrangement. AIDS-associated ALCL is an aggressive lymphoma, with a poor prognosis. However, the presence of the genetic rearrangement, previously unseen in this disease, drastically altered the disease course. This case highlights the value of genetic testing and identifies DUSP22-IRF4-associated ALCL in the setting of HIV-associated lymphoproliferative disorders.

Keywords: cancer intervention, dermatology, genetics, HIV/aids, haematology (incl blood transfusion)

Background

Aggressive AIDS-associated non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas are typically of B cell origin and include Burkitt lymphoma and primary effusion lymphoma. These have been recognised as AIDS-defining conditions. The frequency of T cell lymphomas in the setting of HIV is 12%–15% and, unlike B cell lymphomas, they are generally associated with an inferior outcome.1 2

We report a case of AIDS-related ALCL with the DUSP22-IRF4 genetic rearrangement, which presented with cutaneous involvement and was associated with an excellent response to targeted systemic chemotherapy.

Case presentation

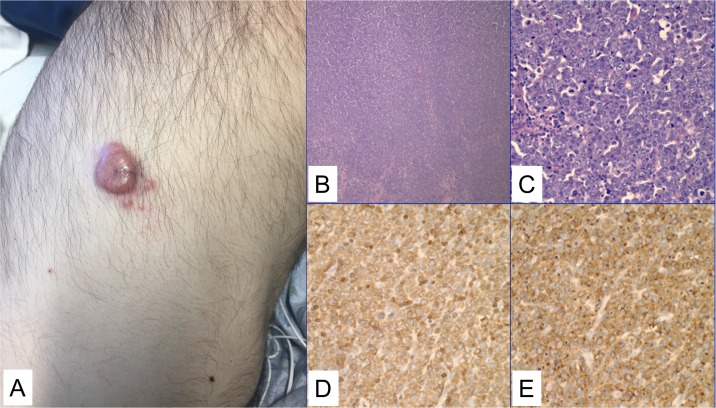

A man aged 53 years presented with subacute lower back pain, lymphadenopathy and multiple subcutaneous non-tender erythematous nodules, predominantly on the scalp and axillae. Two weeks prior, he had noticed tender red-purple nodules on his neck and abdomen (figure 1A). On physical examination, he was found to have bilateral lower extremity weakness and paraesthesia.

Figure 1.

Clinical and histological findings from subcutaneous nodules. (A) On the right flank, there was a 3 cm tender red-purple nodule. Similar lesions were present elsewhere on skin examination (not pictured). (B) A low power (4×) image of the lymph node with effaced architecture. (C) A high-power image (40×) showing sheets of large abnormal lymphoid cells with prominent nucleoli are seen, as well as scattered mitotic figures and apoptotic cells. (D) CD3 stain is positive in the neoplastic cells. (E) CD30 stain is strongly, diffusely expressed in a membranous and Golgi pattern.

Investigations

X-ray of the lumbar spine revealed an L5 compression fracture. He was anaemic with haemoglobin at 118 g/L, and he had elevated lactate dehydrogenase of 798 U/L, elevated alkaline phosphatase of 281 U/L, elevated C reactive protein of 122 mg/L and a low albumin of 2.6 g/dL. HIV testing was positive, and AIDS was diagnosed with an absolute CD4 T cell count of 191 per microlitre. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) was positive with a titre of 1160 IU/mL, while Epstein-Barr virus was negative.

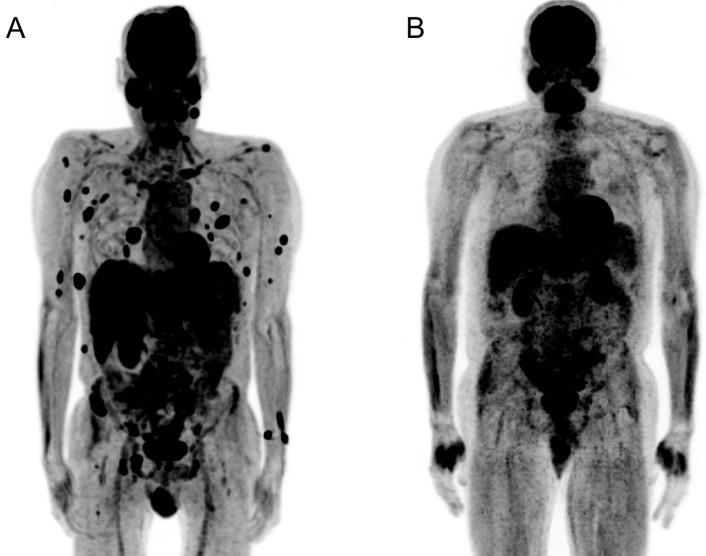

CT imaging of the chest, abdomen and pelvis showed multiple lytic lesions in the thoracic and lumbar spine with cord compression, as well as hypodense lesions in the lungs, liver and spleen and diffuse lymphadenopathy. MRI of the brain revealed a ring-enhancing frontal lobe lesion, causing mass effect. A neoplastic aetiology was suspected. Initial positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) scan confirmed fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in bone and the central nervous system, along with multisystem involvement of the lungs, liver, spleen, pancreas and kidneys (figure 2A). Based on these findings, the International Prognostic Index score for this patient was 3 given the following points: stage III–IV disease (1 point), elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (768 at time of presentation; 1 point) and more than one extranodal site (1 point). With a score of 3, he is at intermediate risk.

Figure 2.

Positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) before and after systemic chemotherapy. (A) PET-CT demonstrating widespread extranodal anaplastic large cell lymphoma disease with multisystem involvement. (B) Repeat PET-CT 7 months later demonstrating complete remission of disease.

An inguinal lymph node biopsy revealed sheets of large pleomorphic, CD3+ abnormal lymphocytes (figure 1B–D), with prominent nucleoli, eosinophilic cytoplasm and frequent mitoses. The lymphocytes exhibited with strong CD30 (membranous and Golgi) positivity (figure 1E). Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) immunohistochemistry was negative. The tissue was sent for fluorescence in situ hybridisation testing to assess for the DUSP22-IRF4 (6p25.3) rearrangement. The assay used a break-apart probe with two normal fusion signals representing a normal, non-rearranged result. This showed the DUSP22-IRF4 rearrangement in 100% of the tumour cells. The findings are diagnostic of anaplastic large cell lymphoma, ALK-negative with DUSP22-IRF4 rearrangement. A skin biopsy of a violaceous nodule on the patient’s right flank showed similar cells within the dermis. The skin biopsy confirmed the lymph node findings, showing that the abnormal T cells were positive for CD3, CD2, CD4, CD8, CD30 and cytotoxic markers, however had loss of CD5 and CD7. The Ki-67 proliferation index was 80%.

Differential diagnosis

The cutaneous lesions alone could have represented primary cutaneous ALCL or Kaposi sarcoma in a patient with HIV, however, given the diffuse systemic involvement, stage IV, ALK-negative, anaplastic large cell lymphoma was diagnosed.

Treatment

Given extensive involvement of the central nervous system, the patient was initially treated with HyperCVAD Part B (ara-c, methotrexate, dexamethasone), followed by Part A (intravenous cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and dexamethasone). The treatment course was complicated by CMV colitis and profound pancytopenia despite the use of growth factors. The patient was simultaneously started on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), that is, dolutegravir, emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide.

Given the patient’s overall poor performance status following one cycle of HyperCVAD, he was switched to monotherapy with brentuximab vedotin, a chimeric monoclonal anti-CD30 antibody conjugated with a small molecule microtubule-disrupting agent, which induces cell cycle arrest.

Outcome and follow-up

Following initiation of brentuximab monotherapy, serial repeat PET-CT showed complete remission in both nodal and extranodal sites (figure 2B). The patient recovered his cell counts and continues to do well with no evidence of recurrent disease on PET-CT 1 year later.

Discussion

AIDS-associated ALCL is typically an aggressive lymphoma, with a 2-year overall survival of 21% in the largest case series to date.2 Over 75% of patients present with stage III or IV disease, and 89% of cases are ALK-negative, a poor prognostic factor.3 The patient was ALK-negative by immunohistochemistry, and further genetic testing revealed the DUSP22-IRF4 rearrangement. DUSP22 is associated with an excellent prognosis, with 5-year survival of 90% in patients without HIV with systemic ALK-negative ALCL, a level comparable to ALK-positive ALCL.4–7 The mechanisms for improved prognosis in DUSP22 rearranged ALCL are unclear but since DUSP22 is likely a tumour suppressor, mutations may lead to increased immunogenic cues, in particular increased antigenicity, higher costimulatory molecule expression and inactivity of the programmed cell death-1/programmed cell death ligand 1 immune checkpoint.8 9 To our knowledge, this is the first case of AIDS-associated systemic ALCL presenting with DUSP22 rearrangement, but a previous case described an indolent ALK-negative ALCL with a DUSP22 rearrangement.10

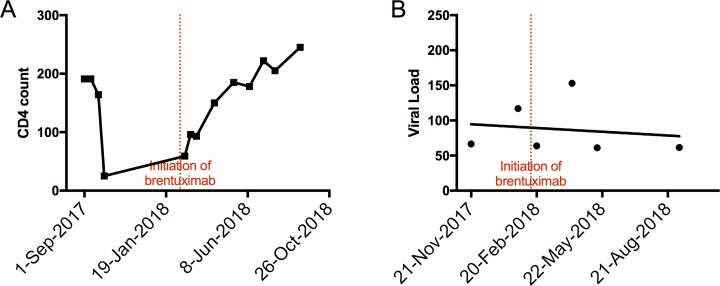

Aggressive cytotoxic chemotherapy was used initially due to the patient’s extensive extranodal disease. However, the subsequent pancytopenia and drastically decreased CD4 T cell counts (figure 3A), despite continuation of HAART, led to multiple complications such as neutropenic fevers, CMV colitis and oral candidiasis. One multicentre study showed that in HIV-associated peripheral T cell lymphoma (PTCL), CD4 T cell counts of <200 cells per microlitre were associated with worse overall survival.11

Figure 3.

Following initiation of brentuximab, CD4 T cell count (A) improved markedly while HIV viral load (B) remained stable and low.

Excellent clinical response to chemotherapy, as well as overall poor performance status prompted a change in management to monotherapy with brentuximab. Brentuximab has been a significant step forward in recent years for targeted therapy against ALCL, and has mainly been investigated as monotherapy in relapsed and/or refractory ALCL.12–14 More recently, brentuximab has also been combined with frontline chemotherapy for initial management of ALCL with promising results that has led to a phase III randomised controlled trial.15 There is a paucity of data for brentuximab use in HIV-associated lymphomas, and all trials, either completed or ongoing (NCT02298257, NCT01771107) have evaluated brentuximab in the setting of HIV-associated Hodgkin’s lymphoma.16 In our case, brentuximab was active to maintain remission in AIDS-associated ALCL and while on brentuximab, the patient’s CD4 T cell count was on a upward trend and his HIV viral load remained stable (figure 3A, B).

Patient’s perspective.

It started with having back pain, which I could have explained away from just my work, scaffolding things and plastering. So, I gave it bed rest for a month and it didn’t get any better. I had a couple of lumps and there was one in particular on my head that I couldn’t deny that I had an issue. I went down to the VA. They did some tests and then I went in to get my results a couple weeks later.

“How do you feel about getting admitted”?

“I don’t understand why”.

“Because you’re very sick person”.

“What do you mean”?

“Well, you have very advanced cancer”.

I lived in San Francisco in the 80s and I lost a lover before I left San Francisco. I left San Francisco because I went to way too many funerals my last year there. It was like everybody was dying and I was just like, “that’s it, I got to go” but I loved the city. I loved everything about it and but at that point it was just death; it was just everybody dying in that awful place.

I just assumed I was HIV-positive and lived my life knowing that my time was short. I moved to Connecticut thinking I had two years of life, so I set myself up, I did what I wanted to do for a career and just got close to my family. I just didn’t think about it. I never saw a doctor, never got sick. It was massive denial, but it got me through 28 years when I thought I only had two. I’m not a religious person, but I’m definitely spiritual. I definitely had survivor’s guilt, and I wondered why I was chosen to ‘make it’.

I didn’t know in the beginning that it was stage 4. It wasn’t until my mom asked me “what stage cancer do you have?” and I told her “I don’t know, like 9 or 10” that I asked someone exactly what stage I am.

HyperCVAD was my first chemo, and I never got nauseous, but I was incontinent for the longest time and that was hard for me. I just had to have someone take care of me, sometimes seven, eight times a day. The PCAs (patient care associate) were amazing people. It’s a calling, I don’t know how they do it. Thank whoever is up there for the PCAs who were here because they kept my dignity intact when there was none to be found.

I was 210 pounds when I came in and when I left at my first discharge I was 137. I wasn’t walking, and I wasn’t sure if I was ever going to walk again. After I went home, I was back here in 24 hours because I fell and hit my head. I didn’t have any strength. I didn’t realize how weak I was and it was probably another couple of weeks at the hospital and then I got discharged again to a rehab centre. I was in a stretcher into an ambulance into a rehab bed and I stayed between that bed and wheelchair for a few months. Then, I had to relearn the art of toileting. The first day I successfully made it by myself was huge and I’ll never forget it. It was kind of awesome.

So that was all on HyperCVAD. It was rough because I would get to the point where I was just starting to feel better, and I knew when I felt good enough it was time to get knocked back down. I knew every time I was feeling better that my labs would be at a point where my oncologist would say let’s do another round. So, I was never really looking forward to feeling better. The switch to brentuximab was great as far as the symptoms go, except for neuropathy. I had issues with my feet which I thought were because of my compression fractures, but along with the tingling in my fingers I now realize it was neuropathy.

There was this ‘lightbulb tumor’ on the top of my head. Nobody was really talking about it and it was like the elephant in the room. They had all this stuff to treat that they had seen before and this was kind of new. I remember walking out to the Healing Gardens and there were some kids from down the hall, from the children’s wing, there. I scared some of the kids, and I was like, “okay I’m frightening to children”. So, I stayed in my room the rest of my stay; the kids were having enough of a struggle without having scared by me.

Then it just started melting. It was kind of miraculous. I remember, when I was trying to figure out if I was going to live or die, talking to my mom, and she wanted to come see me immediately, which she did. I told her after that “I wished you would have waited a week” because when she came in I had all these lumps on my body and this ‘lightbulb’ on my head which she got all freaked out by and a week later they were all gone.

The staff was absolutely amazing. There was an enormous amount of people involved in getting me to here, and I had an overwhelming amount of doctors who came in and saw me on a daily basis. I hadn’t seen the doctor since boot camp in 1982, so I had no reference for healthcare. I didn’t know if it was normal to get seven doctors at a time coming to your room in the morning. There was one doctor who came in and he said something like “you got a mountain of issues that we need to take apart piece by piece, but if you keep a positive attitude we will take care of the rest” and that gave me hope. And I said, “okay I could do this”. So, I kept my part of the bargain and it seems like you guys did your part too.

I was always living very short-term. I never had long-term plans because I never thought I had a long term. So, with this whole experience all of a sudden, I’ve got appointments two years out. I never thought I had ‘two years out’ before cancer and now I’ve gotten a much longer life expectancy than I ever thought I had for the past few decades. It’s bizarre, having to establish certain goals because I’m going to have the time to see them through.

I’m an interior designer—painter, artist, plasterer, gilder. My last clients before I got sick was a couple. He’s a radiation oncologist and she was a nephrologist, and they’ve been with me every step of the way… amazing people. After I started to recover, I told them that I felt like what I was doing was so insignificant, to spend days trying to find the perfect tassel and I didn’t know if I could do it anymore. And they said, “well, let me tell you how important it is to us because we are in hospitals every day and we come home and this place is where we recharge and your work is so needed because it changes how we feel. It recharges us to go back into the field and do the work we do”.

Learning points.

In non-AIDS-associated systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), genetic testing has been used in identifying chromosomal rearrangements, for example, DUSP22-IRF4 that may portend a good prognosis

This case demonstrates the prognostic significance of molecular testing for DUSP22-IRF4 rearrangements in patients with AIDS-associated anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-negative ALCL, as the prognosis of systemic ALK-negative ALCL is typically poor in the AIDS population.

A larger scale investigation of the activity and toxicities of brentuximab vedotin in AIDS-associated ALCL and other CD30 expressing T cell lymphomas is warranted.

Physicians, especially dermatologists and primary care physicians working with high-risk populations should be aware that cutaneous manifestations of ALCL or other aggressive lymphomas can be a presenting manifestation of AIDS.

Footnotes

Contributors: MW, NK, NR, MT and FF conceived of the case report. MW interviewed the patient for the patient’s perspective and obtained consent. NK, NR, MT and FF provided clinical data of the patient. AS provided the pathology photos and descriptions. MW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to critically revising and approval of the manuscript prior to submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Castillo J, Perez K, Milani C, et al. Pantanowitz L: Peripheral T-cell lymphomas in HIV-infected individuals: a comprehensive review. J HIV Ther 2009;14:34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Perez K, Castillo J, Dezube BJ, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2010;51:430–8. 10.3109/10428190903572201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Savage KJ, Harris NL, Vose JM, et al. ALK- anaplastic large-cell lymphoma is clinically and immunophenotypically different from both ALK+ ALCL and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified: report from the International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project. Blood 2008;111:5496–504. 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feldman AL, Law M, Remstein ED, et al. Recurrent translocations involving the IRF4 oncogene locus in peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Leukemia 2009;23:574–80. 10.1038/leu.2008.320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wada DA, Law ME, Hsi ED, et al. Specificity of IRF4 translocations for primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a multicenter study of 204 skin biopsies. Mod Pathol 2011;24:596–605. 10.1038/modpathol.2010.225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parrilla Castellar ER, Jaffe ES, Said JW, et al. ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma is a genetically heterogeneous disease with widely disparate clinical outcomes. Blood 2014;124:1473–80. 10.1182/blood-2014-04-571091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pedersen MB, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Bendix K, et al. DUSP22 and TP63 rearrangements predict outcome of ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a Danish cohort study. Blood 2017;130:554–7. 10.1182/blood-2016-12-755496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mélard P, Idrissi Y, Andrique L, et al. Molecular alterations and tumor suppressive function of the DUSP22 (Dual Specificity Phosphatase 22) gene in peripheral T-cell lymphoma subtypes. Oncotarget 2016;7:68734–48. 10.18632/oncotarget.11930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Luchtel RA, Dasari S, Oishi N, et al. Molecular profiling reveals immunogenic cues in anaplastic large cell lymphomas with DUSP22 rearrangements. Blood 2018;132:1386–98. 10.1182/blood-2018-03-838524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chapman J, Vega F. Indolent ALK-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, DUSP22 rearranged, with an unusual immunophenotype in a human immunodeficiency virus patient. Histopathology 2017;70:1173–5. 10.1111/his.13163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Castillo JJ, Beltran BE, Bibas M, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with HIV-associated peripheral T-cell lymphoma: A multicenter study. Am J Hematol 2011;86:256–61. 10.1002/ajh.21947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Younes A, Bartlett NL, Leonard JP, et al. Brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) for relapsed CD30-positive lymphomas. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1812–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1002965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pro B, Advani R, Brice P, et al. Brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) in patients with relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2190–6. 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pro B, Advani R, Brice P, et al. Five-year results of brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Blood 2017;130:2709–17. 10.1182/blood-2017-05-780049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fanale MA, Horwitz SM, Forero-Torres A, et al. Five-year outcomes for frontline brentuximab vedotin with CHP for CD30-expressing peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Blood 2018;131:2120–4. 10.1182/blood-2017-12-821009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rubinstein PG, Moore PC, Rudek MA, et al. Brentuximab vedotin with AVD shows safety, in the absence of strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, in newly diagnosed HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma. AIDS 2018;32:605–11. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]