Abstract

Rationale

There is an increasing societal demand for quality assurance and transparency of medical care. The American National Academy of Medicine has determined patient centredness as a quality domain for improvement of healthcare. While many of the current quality indicators are disease specific, most emergency department (ED) patients present with undifferentiated complaints. Therefore, there is a need for generic outcome measures. Our objective was to determine relevant patient reported outcomes (PROs) for quality measurement of acute care.

Methods

We conducted semistructured interviews in patients ≥18 years presenting at the ED for internal medicine. Patients with a cognitive impairment or language barrier were excluded. Interviews were analysed using qualitative content analysis.

Results

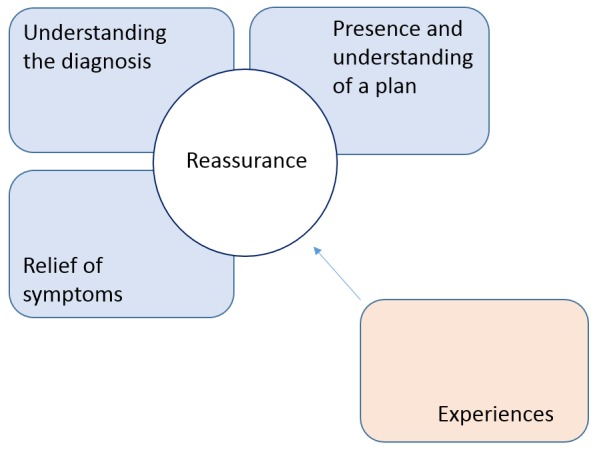

Thirty patients were interviewed. Patients reported outcomes as relevant in five domains: relief of symptoms, understanding the diagnosis, presence and understanding of the diagnostic and/or therapeutic plan, reassurance and patient experiences. Experiences were often mentioned as relevant to the perceived quality of care and appeared to influence the domain reassurance.

Conclusion

We determined five domains of relevant PROs in acute care. These domains will be used for developing generic patient reported measures for acute care. The patients’ perspective will be incorporated in these measures with the ultimate aim of organising truly patient-centred care at the ED.

Keywords: healthcare quality improvement, patient-centred care, patient reported outcome measures

Introduction

There is an increasing societal demand for transparency and quality assurance in medical care including emergency services such as the emergency department (ED). To ensure cost control, safety and transparency of care, many indicators have been developed with the aim of measuring the quality of healthcare.1 2

For example, from 2014 until 2016 the number of quality indicators in the Netherlands increased by 14% from 1360 to 1551 indicators. The majority of these indicators are process and structure indicators, whereas only 2% are outcome indicators.2 These process and structure indicators are less relevant and valid compared with outcome indicators for monitoring the effect of healthcare.3 However, commonly used outcome indicators are generally disease specific and therefore not usable at the ED4 because the patient population at the ED is heterogeneous and patients often lack a diagnosis at presentation. Patients presenting for internal medicine often suffer from multiple chronic conditions and often present with non-specific complaints. Therefore, the commonly used indicators may not reflect the quality of care for this specific group of patients.

On top of that, measuring outcome indicators in the ED is hampered by the severity of acute illness, the need for rapid triage and treatment, and time constraints.5–8

When assessing the quality of care according to the principles of value-based healthcare, achieving high value for patients must become the overarching goal of healthcare delivery. Value should always be defined around the customer and since value depends on results, value in healthcare should be measured by the outcomes achieved.9

Determining ‘patient reported outcomes (PROs)’ is one way to find out which outcomes are valued by the patient. PROs are defined as ‘any report from patients about their own health, quality of life, or functional status associated with the healthcare or treatment they have received’.10 Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) are developed on the basis of PROs and can be used for measurement of the quality of care.11 There is little experience in performing PROM-related research at the ED6 12; however, recent research shows that the measurement of PROMs in acute medical units is feasible.13

One of the six domains for improvement of healthcare determined by the American National Academy of Medicine (NAM) is patient centredness, defined as: ‘providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patients’ values guide all clinical decisions.14 By determining PROs in patients visiting the ED, patients’ needs and values concerning their health during their ED visit can be clarified. Thereafter, establishing PROMs will lead to systematic measurement of the patient perspectives,15 which improves patient outcomes in several ways: it provides information only the patient can assess and improves communication between professionals and patients.16 17 Consequently, these outcomes can be used in the conversation between patients and professionals during the decision-making process and therefore may improve shared decision-making. In this study, we aimed to determine PROs in internal medicine patients at the ED, as a first step in the development of PROMs for acute medical care.

Objective

The primary objective of this study was to collect patient perspectives on outcomes of acute care to determine relevant PROs.

Methods

Study design

We performed a qualitative study in three hospitals in the Netherlands (Máxima MC, Veldhoven; Amsterdam University Medical Centres, location VUmc and location AMC) using semistructured interviews with patients who were treated at the ED by an internal medicine physician. One focus group and 28 individual interviews were held; the focus group took place within 21 days after the ED visit, the interviews were performed within 14 days after the ED visit. Interviews were held by two female medical doctors and PhD students trained in qualitative research (MNTK/ESvdE) and the focus group was led by an experienced quality officer (MvB).

The procedure for determining relevant PROs in acute medical care was based on the guideline ‘PROs and PROMs’ from the Dutch National Federation of University Medical Centres.17

Written consent was obtained from all patients.

Patient involvement

Patients were not involved in the initial design of the study. However, based on comments of the first participating patients, we changed the design to diminish the burden on participants by performing interviews at patients’ homes or by telephone. Interviews were evaluated after finishing and the perceived relevance of our study was discussed with participants. Patients played the central role in this study in determining relevant outcomes of acute care.

Selection of participants

Participants were recruited between March and July 2018. All patients older than 18 years presenting for internal medicine at the ED at any time of the day were approached by their treating physician and introduced to one of the researchers. Patients who were unable to participate in an interview due to language barriers, altered mental status or inability to provide informed consent were excluded.

Initially, patients were called within 7 days after their ED visit to provide them with additional information about the study and to schedule the research interview. A maximum of eight attempts was made to reach each patient who agreed to be contacted. During the study, it appeared that the majority of patients was incapable or unwilling to join a focus group conducted in the hospital. Therefore, we decided to perform individual semistructured interviews instead. Patients were provided with written information about the study and if they were willing to participate, the interview took place during their admission following the ED visit, or when discharged from the ED at patients’ homes or by telephone. In some cases, a relative was present during the interview.

Data collection and processing

At the start of inclusion, we did not find an existing model about PROs for ED patients in the literature. However, patient reported experience measures for ED care have been used for determining relevant outcome domains.18–21 On top of that, information shared by patients about their experiences of emergency care at an online review site was used as well.22 We designed an interview guide and topic list for the focus group and semistructured interviews, making use of the expertise of the researchers, acute physicians and a quality officer. Questions aimed at obtaining the patients’ perspectives on outcomes relevant to their ED visit. Main themes were symptoms, concerns, physical and social functioning. We also included questions about expectations of ED care, reason for presentation at the ED and experiences of the care delivered. At an early stage of our study, the study of Vaillancourt et al was published.12 In this study, relevant PROs for patients treated and directly discharged from the ED in Canada were determined. We compared our interview guide with the questionnaire of Vaillancourt et al and made some minor adjustments.12 Input of the first four interviews was assessed, making sure all themes were covered, to determine the final interview guide (appendix 1).

bmjoq-2019-000736supp001.pdf (80.1KB, pdf)

The focus group with patients lasted 2 hours and individual interviews lasted 20–30 min, with the interviewing investigators making sure all themes were covered in the discussion. Audio recordings were made and field notes were taken. Additional patients were interviewed until saturation was reached, that is, no new themes came up during the interviews, which was evaluated by two investigators (MNTK/TZ) during preliminary analysis.

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed from the audio tapes without returning the transcripts to the participants for comments. Two investigators (MNTK/TZ) coded the transcripts based on open coding in which inductive coding techniques were used according to the qualitative content analysis process,23 leading to establishment of general themes reflecting the acquired data. First, the two investigators developed, independently, a concept coding framework. Codes in this framework were based on the research question and emerged from review of the data of the first three interviews. For coding of patient experiences, we used domains of the Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire as a guideline.24 For other emerging themes, the most suitable coding terms were defined by the investigators after close reading of the interviews and a line-by-line discussion. After coding five interviews with close reading and continuous comparison of the coding, the two investigators determined a final coding framework which was applied to all transcripts. Discrepancies in coding were handled through discussion. Participants did not provide feedback on the findings. Categories were composed by the same two investigators after coding.

For coding and analysis of the interviews, the software program QDA miner Lite V.2.0.5 was used.

Results

Patient characteristics

We interviewed 30 patients who visited the ED and were treated by an internal medicine physician, 14 patients were recruited at the Máxima MC, 7 patients at the Academic Medical Centre and 9 patients at the VU University Medical Centre. Nine patients were interviewed by telephone, 2 patients participated in a focus group, 4 patients were interviewed at home and 14 patients were interviewed during admission. The mean age of participating patients was 68 years. Sixteen (53%) patients were female, 22 (73%) patients were married and 26 (87%) patients were born in the Netherlands. Twenty-eight (93%) patients were hospitalised after ED visit. Twenty-five (83%) patients were referred to the ED, which is a reliable reflection of the Dutch situation. The main reason for seeking help at the ED was experiencing symptoms and in a few cases the decision of the general practitioner or due to laboratory results. The most frequently reported primary complaints were fever and pain (table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Patient characteristics | Interviewed (n=30) |

| Age, mean (range), years | 68 (28–90) |

| Female, % | 16 (53) |

| Married, % | 22 (73.3) |

| Living alone, % | 5 (16.7) |

| Children, 1 or more, % | 23 (76.6) |

| Receiving homecare, % | 7 (23.3) |

| Admitted after ED visit, % | 28 (93.3) |

| Primary complaint | |

| Fever | 9 (30%) |

| Pain | 6 (20%) |

| Cardiopulmonal | 3 (10%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 (13%) |

| Urinary tract | 2 (7%) |

| Dermal | 1 (3%) |

| Non-specific | 2 (7%) |

| Laboratory findings | 3 (10%) |

| Level of education | |

| Unknown/not answered | 2 (7%) |

| Less than high school | 2 (7%) |

| High school | 2 (7%) |

| College | 13 (43%) |

| Postgraduate degree | 11 (37%) |

| Country of origin | |

| Netherlands | 26 (86.7%) |

| Other | 4 (13.3%) |

| Main reason for ED visit | |

| Symptoms | 27 (90%) |

| Laboratory results | 3 (10%) |

| Way of referral | |

| Self-referral | 3 (10%) |

| GP | 19 (63%) |

| Specialist | 6 (30%) |

| Ambulance | 2 (7%) |

ED, emergency department; GP, general practitioner.

Themes mentioned

We identified common themes mentioned by patients during the interviews. To establish a model of PROs for acute medical patients at the ED, we grouped the themes mentioned into five different domains: (1) relief of symptoms, (2) understanding the diagnosis and cause of symptoms, (3) presence and understanding of the diagnostic or therapeutic plan, (4) reassurance and (5) patient experiences. Table 2 represents coded subcategories and associated quotes for each domain.

Table 2.

Patient reported outcomes: domains, subcategories and quotes

| Domain | Subcategory | Representative quote |

| Relief of symptoms | Degree of relief of symptoms |

P4: It was very important for me that the vomiting and abdominal pain was relieved. P7: They gave me oxygen trying to relieve my shortness of breath, which I think is important. P24: I wanted to stop vomiting. P26: The pain and dyspnea were very bad. So I’m happy when they do something against it. |

| Duration until symptom relief |

P2: I wanted to get better, as soon as possible. P22: When someone arrives at the ED they directly have to give something against the pain. I just wanted to get rid of the pain. |

|

| Impact on function |

P16: They had to relieve the fever, so that I can function normally again. P25: I wanted to get better. The only thing I wanted was to stand on my legs again. |

|

| Understanding the diagnosis and cause of symptoms | Understanding the diagnosis and cause of symptoms |

P2: At the ED I want to know, as quickly as possible, what the diagnosis is. P7: I’m worried when I don’t know what is causing the shortness of breath. P11: I’m never ill. Therefore, I wanted to know what is making me ill? P21: The worst thing is not knowing what’s wrong. For me it’s important that they explain what they think the diagnosis is; what’s the reason for my complaints? P28: I want to know what is causing the problem. |

| Understanding the prognosis |

P5: I want to know if the cancer is spread through my body and what that means for the treatment. P19: I want to know how to deal with my shortness of breath. What can I do? I just want to be able to cycle again. |

|

| Presence and understanding the diagnostic or therapeutic plan | Understanding the diagnostic plan |

P8: The fact that you know what they are going to do with you, is very important for me. They would complete some more tests after my stay at the ED to evaluate the cause of my blood loss. P10: I had to stay in the hospital for one night to observe my heart rate. That was very clear to me. |

| Understanding the treatment plan |

P1: Doctors repeatedly have to tell what they are going to do and why, that reassures me. P3: They explicitly told me what they were going to do with me. At the ED they gave me intravenous fluid and antibiotic, because the oral antibiotic I used at home didn’t work well. It is important to know why they do that. P5: They told me I had too little red blood cells and that they had to give me a blood transfusion. P26: They provide me with updates on the treatment plan. That is important for me, because otherwise you might feel forgotten. |

|

| Understanding follow-up after discharge from the ED |

P2: They told me that I could go home with oral antibiotic pills. And they said it was important to drink enough water. That was clear to me, which gave me confidence going home. P18: When you arrive at the ED with fever, you know that they can’t resolve the problem within 5 min. But it’s important that they tell you something about the plan they have for you thereafter. |

|

| Reassurance |

P1: I was worried because a friend of mine died last summer and I was afraid of dying at the ED. I needed more reassurance, not from a nurse or a medical student, but a real doctor. P5: It gives reassurance, when you’re treated nicely and they give you enough attention. P8: The clear explanation about my symptoms and diagnosis reassured me. P14: The fact that they tell you what will happen and noticing they are doing everything possible for you, reassured me. P20: The expertise of the doctors and the fact they know my medical history gives me confidence. |

|

| Experiences | Coordination of care |

P4: The nurses and doctors asked me the same questions over and over again. It seemed they did not communicate. P29: I had to wait for the radiologist quite a long time. However, it helped that they told me that 2 critical patients at the ED needed help more urgently. |

| Continuity and transition | P16: I went home quite insecure. I didn’t know what would happen next and when I had to come back. | |

| Information and education | P26: They continuously updated me on what was going on and which diagnostics were planned. That’s good. | |

| Emotional support |

P6: They really listened to me and payed attention. They frequently asked if I needed anything. P24: The nurses did what they needed to do. They put you at ease. |

|

| Patient preferences |

P30: The doctor told me she thought it was better to be admitted, but she asked me wat I thought about that. That was really nice. P24: The doctor told me what condition I was suffering from and which treatment options were available. He explained the options really well so that I could choose which one suited me the most. |

|

| Family involvement |

P6(daughter): I think we were well informed at the ED. They explained what they were doing and answered all my questions. P12: I helped that my wife was with me, she supported me emotionally. She received all the information of the doctors and could explain it to me, while I was too ill. |

ED, emergency department.

Relief of symptoms

The majority of patients reported that relief of symptoms was an important outcome of ED care. Especially in patients suffering from shortness of breath, pain or vomiting, reducing symptoms was their primary expectation regarding outcomes of care, as voiced by patient 4: “I didn’t care what they were doing to me, I just wanted less abdominal pain and something to relieve the vomiting”. Within this category, the degree of symptom relief, the duration until relief and the impact on function were mentioned as relevant and appeared to influence feelings of safety and reassurance: a prompt and adequate relief of symptoms was associated with relief of anxiety and trust in healthcare professionals. Patient 22 mentioned: “I only wanted to get rid of the pain. The painkiller they gave me at the ED worked immediately, which made me feel safe.”

Understanding the diagnosis and cause of symptoms

Twenty-five patients mentioned that one of the most important outcomes was a clear explanation of their symptoms and diagnosis. The uncertainty patients experience suffering from symptoms while not knowing their diagnosis underlies this important outcome: “For me it is really important that doctors explain what they think is causing my complaints. The worst part is not knowing, feeling insecure.” (P21) A clear explanation about symptoms and diagnosis may even lead to relief of feeling insecure. In contrast, a vague explanation of diagnosis could lead to ongoing uncertainty by patients, as happened to patient 4: “They thought I had a urinary tract infection. That wasn’t clear for me because I had pain in the right upper part of my abdomen. I thought that a urinary tract infection causes pain in the lower abdomen”.

Only a few patients, most of them suffering from a chronic condition, desired information about the prognosis of their disease.

Presence and understanding of the diagnostic or therapeutic plan

Presence and understanding of the diagnostic or therapeutic plan was evaluated as an important outcome of the ED visit by 24 patients. The treatment plan encompasses both the diagnostics and the treatment at the ED, and the treatment afterwards, such as instructions for home care, decision to admit and estimated duration of admission. Many patients think that having an estimation about the waiting time at the ED is very important, because feeling left alone at the ED occurs easily and causes distress: “I just wanted someone who updated me on a regular basis. It feels good to know they are busy for you. Without information you’re just lying there thinking: they probably have forgotten me.” (P23)

Patients also expressed the need for clear answers on their questions and felt frustrated if contradictive information was given. In addition, for many patients knowing and understanding the treatment plan contributed to feeling reassured by taking insecurity away. An important item mentioned is information about being admitted or not, as patient 13 said: “I was anxious, because I did not know if I had to be admitted or would be discharged home. It took hours waiting for this decision and all that time I did not know anything.”

Reassurance

The majority of patients reported reassurance as a relevant outcome of ED care. Reassurance seems to be a broad concept, as different explanations are given. Most patients explained reassurance as relief of the feelings of anxiety or insecurity. These feelings were mostly triggered by not knowing the cause of symptoms and whether symptoms could become even more severe. In these cases, in general, reassurance could be reached by a clear explanation about the cause of symptoms or a treatment plan. For example, patient 18: “Reassurance is important. If they tell you the diagnosis cancer, that isn’t really reassuring. However, knowing what you’re suffering from is always better than not knowing. Reassurance includes being well-informed.” Others just wanted to hear ‘everything will be okay’. In addition, experiencing symptom relief due to treatment also decreased feelings of anxiety.

For many patients, reassurance included also the feeling of being in good hands, which is explained as a combination of safety and professionalism. For some patients, this feeling is instantly being met by arriving at the ED, related to the diagnostic options and complex treatment possibilities. For others, the availability of their medical history and medication in an electronic patient record, a quick response to ringing alarms or prompt therapy leads to feeling safe as patient 11 mentioned: “The nurse immediately recognised the high fever and told me she had to follow a specific protocol and promptly administer antibiotics. She explained why this had to happen, which made me feel really safe.” Furthermore, a professional attitude of the staff, for example, a kind approach, personal attention and recognition of complaints, is for many patients related to confidence in healthcare and diminishes feelings of insecurity.

Finally, some patients mention that the consequences of not being reassured may influence daily life: “My wife and I still have concerns. Every evening before I go to bed I measure my temperature, just to be sure that’s fine. I needed more reassurance, not from a nurse or a medical student but from a real doctor.” (P1)

Of the patients not mentioning reassurance as a relevant outcome of acute care, the majority suffered from chronic diseases and are familiar with the ED and the cause of their recurrent symptoms. Some of them specifically mentioned that, if they would arrive at the ED with another complaint than usual, they probably would seek reassurance.

Experiences

Many patients reported experiences as important factors for satisfaction about their ED visit and perception of healthcare quality. These experiences reflect all themes mentioned in the Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire24: coordination of care, continuity and transition, information and education, emotional support, patient preferences and family involvement. Themes mentioned most often were waiting times, followed by a kind approach of healthcare providers. The majority of patients expected short waiting times because they were referred to the ED, which to them implied that something was seriously wrong and that they should therefore be helped quickly. Patient 2 explained this clearly: “I’m referred to the ED. Apparently there is a possibility that something is seriously wrong, so I expect they will help me quickly. That is why it is called Emergency Department.” If diagnostics or therapy are initiated without long waiting times, patients experience this as safe and this leads to confidence and the feeling to be in good hands. In contrast, patients who experienced long waiting times, often felt forgotten, which triggered anxiousness. However, most patients could accept longer waiting times if they were informed that higher priority patients required attention prior to them. In addition, a kind approach of healthcare professionals is highly valued by many patients and an empathic attitude may help patients coping with their illness or stay at the ED. It may even lead to feelings of reassurance: “I felt that I could relate to the doctor. I felt he took my problems seriously and that reassured me.” (P30)

Discussion

Defining PROs for acute medical patients provides a basis for increasing patient centredness at the ED and reveals themes valued by patients in acute care. Although patients treated by an internist reflect a heterogeneous population, mostly not having a diagnosis when they enter the ED, we found common themes in outcomes valued by patients. These themes can be classified in five domains: relief of symptoms; understanding the diagnosis and cause of symptoms; the presence and understanding of a diagnostic or therapeutic plan; reassurance; and patient experiences.

The major part of the themes mentioned as important outcomes of acute care was in fact patient experiences. However, while researchers and doctors try to distinguish patient reported outcomes from patient reported experiences, patients do not. In their perception of quality of care, both outcomes and experiences play an important role. Therefore, in this study, we include experiences and outcomes as relevant domains for evaluating the quality of acute care.

Healthcare leaders and many researchers have tried to improve the quality of care at the ED by incorporating the patient perspective and focusing on patient experiences and satisfaction.19–21 25 Staff-patient communication, ED waiting times, expectations and experience of care all contribute to patient satisfaction.26 In our study, patients reported all of these themes and even indicated an association between these experiences and feeling reassured, which is consistent with findings in the study of Body et al.27 In addition, a positive experience is associated with superior outcomes including mortality, morbidity and length of stay.28 This shows the importance of including patient experiences as a fifth domain in evaluating the quality of care, which is new in comparison to the study of Vaillancourt et al.12

We found that the domains of understanding the diagnosis and having a treatment plan are mentioned as relevant outcomes of acute care and influenced feeling reassured. We noticed that these domains influence feelings of anxiety or emotional distress and therefore could be considered as derivative outcomes of mental health. This hypothesis is supported by the findings of Body et al,27 who found that suffering in patients at the ED is partly due to physical symptoms, but often caused by emotional distress. Relief of mental suffering in this context can be achieved by providing information about the diagnosis and treatment plan.

In this study, patients indicated that an important outcome of their ED visit was symptom relief, in particular in patients experiencing symptoms such as pain, vomiting and dyspnoea. Pain relief is a common and well-known reported outcome of patients visiting the ED.29 30 In Dutch EDs, only pain is assessed on a structural basis using the Visual Analogue Scale or Numeric Rating Scale. It is useful therefore to pay more structural attention to other complaints such as dyspnoea and vomiting.

Understanding the diagnosis and cause of symptoms proved an important outcome for patients seeking help at the ED. A study focussing on patient needs at the ED already revealed that many patients seek emergency care to get a diagnosis.31 However, on closer examination, patients appear to not only desire an explanation for their symptoms, but also treatment and guidance for symptoms and clear communication about testing, treatment and diagnosis, which is in line with our findings.

Our study made clear that patients would like to be well informed about the diagnostic and treatment plan, including diagnostics or treatment at the ED and thereafter. Having a plan, for example, an estimation of waiting time and order of testing during the ED visit and instructions for discharge, is already part of the (Dutch) Consumer Quality Index – Emergency Department.26 This includes questions such as: “Were you informed by your healthcare professional about the next steps in your treatment?” or “Did your healthcare professional tell you at what moment you could restart your normal daily activities?” Although these questions are indicative of discussion of the treatment plan, it does not say much about the quality of the conversation. Attention for the quality of the conversation is important because an association between patient-centred communication and patient satisfaction has been demonstrated.32

Reassurance appeared to be another relevant outcome of ED care for many patients. However, patients reporting made clear that reassurance cannot be reached in one specific manner for all patients. Some patients were already reassured by arriving at the ED, while for other patients a clear understanding of the diagnosis and treatment plan was necessary. Themes associated with reassurance were professionalism, clear communication, confidence in the staff and service, understanding the treatment plan, understanding the diagnosis, relief of symptoms and a short waiting time. These themes are congruent with the conceptual model of Togher et al,33 who interviewed patients on relevant outcomes of ambulance services. Clearly, there is an association between understanding the treatment plan or diagnosis, symptom relief and patient experiences, and feeling reassured, which we incorporated in our conceptual model.

We propose a conceptual model of relevant PROs for acute medical care at the ED, which shows the potential association between the different outcome domains (figure 1). It shows that among other things, understanding the diagnosis and the presence of a plan are essential themes at the ED, highly valued by patients. In the perspective of shared decision-making, a first step to enable shared decision-making at the ED is to communicate the diagnosis and therapeutic or diagnostic plan in an understandable way. In addition, as patients are seeking reassurance, we believe that professionals should ask the patients what they can do to reassure them.

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual model of patient reported outcomes of acute care, showing the relevant domains and their mutual connection.

Limitations

During the inclusion of participants, we did not register those patients who were unwilling or unable to participate in the study. We do not know if this group differs from the interviewed group, although considering the heterogeneity of the interviewed group, we do not expect major differences. Of note, our study population was relatively well educated, which may have caused selection bias. Therefore, validating the conceptual model in at least a lower educated patient group would have strengthened our findings.

Due to suboptimal enrolment in focus groups, we conducted individual interviews. Although individual interviews preclude interaction between participants, we are convinced that saturation of data has been reached. Theoretically, interviews held by telephone may prevent receiving signs via facial expression or body language. However, we conducted most interviews face-to-face and taking those experiences into account, we do not think that we missed important facial expressions or expressions through body language during the interviews held by telephone.

Hypothetically, relevant outcomes of acute care may differ between admitted and discharged patients. In our study, we have used a convenience sample, and as a result, we may have under-reported discharged patients. Yet, in the study of Vaillancourt et al,12 performed in Canada in patients treated by an ED physician, who were immediately discharged, the same relevant outcomes were found. In addition, a meta-synthesis of Graham et al shows that the reported relevant patient experiences in our study align with the experiences found in their study.34 This makes it plausible that admitted and discharged patients, irrespectively of their treating specialist, value the same outcomes while being treated at the ED.

Conclusion

There is an increasing demand for improvement of quality of care and achieving high value for patients, taking the patient’s perspectives into account. However, partly due to the acute setting and heterogeneous population, development of patient-centred quality indicators at the ED has received little attention in the past. We inventoried five core domains representing PROs of patients who visit the ED for internal medicine in the Netherlands, which are relief of symptoms, understanding the diagnosis, understanding treatment plan, reassurance and patient experiences. We believe that the patient’s perspective should be incorporated in daily practice. Doctors can use the found domains in conversations with patients to evaluate the delivered care. Furthermore, based on the findings of this study, we will develop patient reported measures for acute care, with the ultimate aim of organising high-quality patient-centred care at the ED. This will encourage the conversation between patients and professionals at the ED, as a first step to shared decision-making.

Footnotes

Contributors: FH conceived the idea for this research. MNTK, HRH and PWBN designed the project. TZ, MNTK and ESvdE were responsible for inclusion of participating patients. MNTK, ESvdE and MvB executed the interviews and focus groups. TZ and MNTK transcribed and coded all interviews and focus groups. MNTK and TZ drafted the manuscript. All authors (MNTK, TZ, ESvdE, MvB, FH, PWBN and HRH) critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The Dutch Society for internists (Nederlandse Internisten Vereniging) provided funding for this research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committees of the participating hospitals (Máxima Medical Centre, Amsterdam UMC location VUmc and AMC).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Moes FB, Houwaart ES, Delnoij DMJ, et al. Stranger in the ER; quality indicators and third Party interference in Dutch emergency care. J Eval Clin Pract 2018;6:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dijk W, van der Eijk J, Dekker M, et al. Het tekort AAN uitkomstindicatoren. Available: https://www.zorgvisie.nl/blog/het-tekort-aan-uitkomstindicatoren [Accessed Jan 2018].

- 3.Hung K-Y, Jerng J-S. Time to have a paradigm shift in health care quality measurement. J Formos Med Assoc 2014;113:673–9. 10.1016/j.jfma.2014.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg Basisset medisch specialistische zorg kwaliteitsindicatoren 2018; 2018.

- 5.Lindsay P, et al. The development of indicators to measure the quality of clinical care in emergency departments following a modified-delphi approach. Acad Emerg Med 2002;9:1131–9. 10.1197/aemj.9.11.1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samuels-Kalow ME, Rhodes KV, Henien M, et al. Development of a patient-centered outcome measure for emergency department asthma patients. Acad Emerg Med 2017;24:511–22. 10.1111/acem.13165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rising KL, Carr BG, Hess EP, et al. Patient-centered outcomes research in emergency care: opportunities, challenges, and future directions. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23:497–502. 10.1111/acem.12944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burstin HR, Conn A, Setnik G, et al. Benchmarking and quality improvement: the Harvard emergency department quality study. Am J Med 1999;107:437–49. 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00269-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med 2010;363:2477–81. 10.1056/NEJMp1011024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cella D, Hahn EA, Sally MA, et al. Methodological issues in the selection, administration and use of patient-reported outcomes in performance measurement in health care settings, 2012. Available: https://www.zorginzicht.nl/kennisbank/Paginas/prom-cyclus-stap-2-selecteren-pros.aspx

- 11.Weldring T, Smith SMS. Patient-reported outcomes (pros) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Health Serv Insights 2013;6:HSI.S11093–8. 10.4137/HSI.S11093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaillancourt S, Seaton MB, Schull MJ, et al. Patients' Perspectives on Outcomes of Care After Discharge From the Emergency Department: A Qualitative Study. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70:648–58. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Galen LS, Van Der Schors W, Damen NL, et al. Measurement of generic patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in an acute admission unit; a feasibility study. Acute medicine 2016;15:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Institute of Medicine Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21ste century. Washington: National Academy Press, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawson J, Doll H, Fitzpatrick R, et al. The routine use of patient reported outcome measures in healthcare settings. BMJ 2010;340 10.1136/bmj.c186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenhalgh J, Long AF, Flynn R. The use of patient reported outcome measures in routine clinical practice: lack of impact or lack of theory? Soc Sci Med 2005;60:833–43. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terwee C, Van Der Wees PJ, Beurskens S, et al. Handreiking voor de selectie van PROs en PROMs, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bos N, van Stel HF. Consumer quality index seh. Bepalen van Het discriminerend vermogen, 2013. Available: https://www.zorginzicht.nl/./Spoedeisende%20hulp%20(SEH)/./CQI%20SEH%20O

- 19.Bos N, Seccombe IJ, Sturms LM, et al. A comparison of the quality of care in accident and emergency departments in England and the Netherlands as experienced by patients. Health Expectations 2016;19:773–84. 10.1111/hex.12282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Male L, Noble A, Atkinson J, et al. Measuring patient experience: a systematic review to evaluate psychometric properties of patient reported experience measures (PREMs) for emergency care service provision. Int J for Quality in Health Care 2017;29:314–26. 10.1093/intqhc/mzx027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCusker J, Cetin-Sahin D, Cossette S, et al. How Older Adults Experience an Emergency Department Visit: Development and Validation of Measures. Ann Emerg Med 2018;71:755–66. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Redactie ZorgkaartNederland. Veel onvoldoendes voor spoedzorg., 2018. Available: https://www.zorgkaartnederland.nl/feiten-en-cijfers/veel-onvoldoendes-voor-spoedeisende-hulp-op-zorgkaartnederland

- 23.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S, et al. The Picker patient experience questionnaire: development and validation using data from in-patient surveys in five countries. Int J Qual Health Care 2002;14:353–8. 10.1093/intqhc/14.5.353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sonis JD, Aaronson EL, Lee RY, et al. Emergency department patient experience: a systematic review of the literature. J Patient Exp 2018;5:101–6. 10.1177/2374373517731359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bos N, Sturms L, Schrijvers AJP, et al. The development and first use of the Consumer Quality Index for the accident and emergency department. BMC Health serv res 2012;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Body R, Kaide E, Kendal S, et al. Not all suffering is pain: sources of patients’ suffering in the emergency department call for improvements in communication from practitioners. Emerg Med J 2015;32:15–20. 10.1136/emermed-2013-202860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open 2013;3:e001570 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motov SM, Khan AN. Problems and barriers of pain management in the emergency department: are we ever going to get better? J Pain Res 2009;2:5–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaakeer MI, van Lieshout JM, Bierens JJLM. Pain management in emergency departments: a review of present protocols in the Netherlands. Eur J Emerg Med 2010;17:286–9. 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328332114a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerolamo AM, Jutel A, Kovalsky D, et al. Patient-identified needs related to seeking a diagnosis in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2018;72:282–8. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finefrock D, Patel S, Zodda D, et al. Patient-centered communication behaviors that correlate with higher patient satisfaction scores. J Patient Exp 2018;5:231–5. 10.1177/2374373517750414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Togher FJ, O'Cathain A, Phung V-H, et al. Reassurance as a key outcome valued by emergency ambulance service users: a qualitative interview study. Health Expectations 2015;18:2951–61. 10.1111/hex.12279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graham B, Endacott R, Smith E, et al. ‘They do not care how much you know until they know how much you care’: a qualitative meta-synthesis of patient experience in the emergency department. Emerg Med J 2019;0:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjoq-2019-000736supp001.pdf (80.1KB, pdf)