Abstract

Countries have implemented a range of reforms in health financing and provision to advance towards universal health coverage (UHC). These reforms often change the role of a ministry of health (MOH) in traditionally unitary national health service systems. An exploratory comparative case study of four upper middle-income and high-income countries provides insights into how these reforms in pursuit of UHC are likely to affect health governance and the organisational functioning of an MOH accustomed to controlling the financing and delivery of healthcare. These reforms often do not result in simple transfers of responsibility from MOH to other actors in the health system. The resulting configuration of responsibilities and organisational changes within a health system is specific to the capacities within the health system and the sociopolitical context. Formal prescriptions that accompany reform proposals often do not fully represent what actually takes place. An MOH may retain considerable influence in financing and delivery even when reforms appear to formally shift those powers to other organisational units. MOHs have limited ability to independently achieve fundamental system restructuring in health systems that are strongly subject to public sector rules and policies. Our comparative study shows that within these constraints, MOHs can drive organisational change through four mechanisms: establishing a high-level interministerial team to provide political commitment and reduce institutional barriers; establishing an MOH ‘change team’ to lead implementation of organisational change; securing key components of systemic change through legislation; and leveraging emerging political change windows of opportunity for the introduction of health reforms.

Keywords: AUGE: Universal Access with Explicit Guarantees, DOH: Federal Department of Health (Australia), MOH: Ministry of Health, MOPH: Ministry of Public Health (Thailand), NFZ: National Health Fund (Poland), NHSO: National Health Security Office (Thailand), SOH: Superintendency of Health (Chile), UCS: Universal Coverage Scheme (Thailand), UHC: Universal Health Coverage

Summary box.

Many middle-income countries establish purchasing and provision agencies apart from ministries of health (MOH) in pursuit of universal health coverage, but little evidence exists about how MOHs actually exercise power and influence thereafter.

Historically, unitary national health service systems are increasingly part of more complex systems with a growing presence of private providers, but there is little evidence about how MOHs exercise influence in pluralistic healthcare delivery systems.

There is no single model of how responsibilities will be distributed in support of major reforms to service delivery and financing; MOHs can exercise considerable power even when some responsibilities are shifted to another organisation.

Although MOHs are limited in their ability to achieve structural health system reforms when relying only on internal capabilities, empirical observations of the de jure and de facto organisational changes to MOHs in four countries identified four mechanisms that MOHs can use to shape the impact of system-wide organisation reform.

Introduction

Most low and middle-income country governments established surprisingly similar national health services as the main domain of government action to improve health. Typically, these rely on direct managerial control by government over healthcare financing and delivery. With growing global attention to universal health coverage (UHC),1 more middle-income countries with rising incomes are emulating higher income country health systems by shifting away from traditional tax-financed, unitary government control of healthcare and separating the organisational structures for the financing and delivery of healthcare in order to introduce market-like mechanisms. International experience suggests there are diverse pathways to reform health financing and provision in support of UHC,2 but there is inadequate understanding of how such organisational reforms affect health system governance and the organisational functioning of a ministry of health (MOH) accustomed to controlling both the financing and delivery of healthcare.

This paper provides new insights into how health governance and the organisational structure of an MOH change in association with reforms in financing and service delivery, based on a review of experiences in four countries. Financing reforms studied include the introduction of a purchasing or payment agency employing strategic purchasing and new provider payment methods. Service provision reforms include the transformation from a centralised government-owned and operated healthcare delivery system into more decentralised and autonomous structures, or the development of a hybrid delivery system with public and private providers. The potential implications to MOHs of these reforms encompass changes to direct administrative control of healthcare funds, direct managerial control over providers, or designated responsibilities in other areas, such as regulation, policy, research, and monitoring and evaluation. Scholars have noted a duality in large health reforms, that an MOH may simultaneously be challenged to lead a transformation of the health sector while also transforming and even reducing its own internal functions and responsibilities.3

This study was carried out by the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health in the context of research for the Malaysia MOH exploring how reforms in finance and delivery of healthcare might affect that ministry. We explored comparative case studies of health reforms and accompanying organisational changes in four upper middle-income and high-income countries—Chile, Poland, Thailand and Australia—that underwent significant but not identical reforms in service delivery and financing.

Framing our observations of four countries

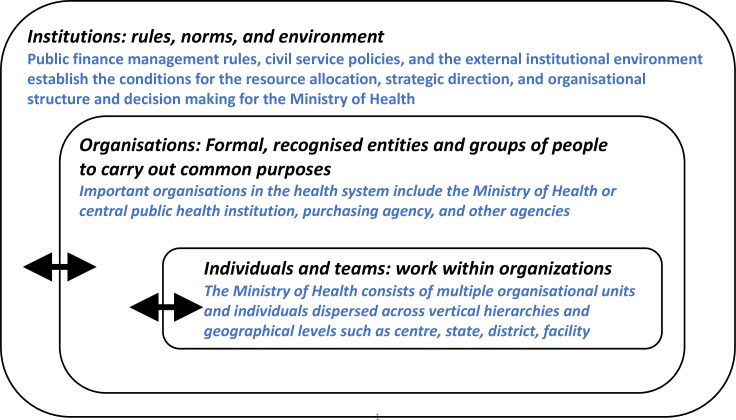

We conceptualise a health system composed of three distinct domains: institutions consisting of formal and informal rules, norms, customs, inspired by the institutional economics theory popularised by Douglass North4; organisations that are the formal structures through which individuals and groups work towards common objectives; and individuals and teams who work within organisations to carry out those objectives (figure 1). The dynamic relationships that exist between the domains underscore that MOHs both influence and are themselves influenced by reform initiatives.

Figure 1.

Governance Domains in a Health System

For our analysis, we drew on three commonly known health systems frameworks—the WHO’s ‘building blocks’,5 the 2000 World Health Report’s ‘functions’ of a health system6 and the ‘control knobs’ framework7—to develop a stylised rubric of selected core responsibilities for health finance and provision that are typically distributed across health organisations within a country (figure 2).

Figure 2.

The distribution of key health system roles and responsibilities in four case study countriesGP, general practitioner; MOH, ministry of health.

We reviewed literature on the health system of each country, focusing on service delivery and financing reforms for UHC and conducted semistructured interviews with three to four researchers and policymakers in each country in late 2017 and early 2018. We held webinar discussions between subject matter experts from each country and senior officials from the Malaysian MOH to validate our understanding of the organisational transformations and provide insights on the extent to which health sector transformations were affected by the sociopolitical context, the sequencing of organisational change, the building of capacity to meet these organisational changes and the subsequent changes in accountability structures. Our inquiry focused on understanding organisational transformations in the MOHs accompanying reforms in finance and delivery.

The countries we examined experienced major reforms to the financing and delivery of healthcare over one or more decades. Although each country established a health purchasing agency, the control the MOH exerts over the purchaser varied in formal structure and in practice. Independent purchasers in a nominal or de jure sense may function in close concert with the leadership of MOH because of structural linkages such as the location of rights to appoint directors or governing boards or rules regarding MOH oversight. But how this distribution actually functions, in terms of actual roles, responsibilities, authorities and accountabilities, may not be well reflected in the nominal or de jure structures and may be modulated by institutional factors. We found that the sequence of steps taken to put in place reforms varies even if two countries had the same programmatic goal—and in most cases goals vary considerably. The sociopolitical context of each country affects the trajectory of implementation and change significantly.

Figure 2 shows the variations found in our identified set of core responsibilities in service delivery and financing across health system organisations after reform implementation in the case study countries. The conceptual starting point is a government-funded, owned and operated health system in which all responsibilities were embedded within the MOH—the classic ‘national health service’ model. Three of the case countries implemented reforms to move away from a unitary system, while Australia never had a ‘national’ health service.

Chile

In the 1970s and early 1980s, the military government in Chile fundamentally altered how government health services were financed and delivered. The funding and purchasing of health services was given over to a new government organisation, FONASA. A legal framework was established to promote the participation of private health insurers, known as ISAPREs, and the market share and power of private providers subsequently increased. Over time, it became apparent that private insurers enrolled healthier citizens and thus the burden on the government-financed system did not decrease, also partially due to the epidemiological and demographic changes in the population. The two-tiered system exacerbated equity and financing gaps, which the democratically elected government of the 2000s addressed by standardising the quality and service criteria by which any provider or insurer would be reimbursed. This was done by mandating a national health benefits package through the Universal Access with Explicit Guarantees (AUGE) reforms of the mid-2000s. A Superintendency of Health (SOH) was established to oversee the AUGE benefits package purchased by FONASA, the government purchaser, and by private insurers.

The relationships between MOH, SOH and FONASA illustrate the complexities of formal governance structures as well as informal relationships. On paper, MOH roles have narrowed greatly: government funding for healthcare now flows through FONASA, not through the MOH budget, and the direct management of healthcare delivery is the responsibility of subnational organisations. The MOH has less vertical authority but has a very strong role in overseeing the system and can exert a high degree of influence. For example, FONASA is structurally independent of the MOH, but the director of FONASA is appointed by the President in agreement with the Minister of Health. The SOH is an independent government organisation linked to the President through the MOH. It regulates the government purchaser, FONASA, and private insurers. The MOH has responsibility for overall system performance and health sector policy. Although the three organisations are operationally independent, decisions about their leadership, with consequences for their operations, reflect considerable influence from the MOH. One downside to this arrangement is lack of certainty about the policy direction agencies may take since their leaders could change quickly for political reasons. Effective health governance in Chile is therefore partially dependent on personal and political relationships in addition to the formal organisational governance structures.

Poland

Poland underwent multiple health system reforms over two decades, starting in the 1990s, in step with broader administrative reforms for increased local autonomy and liberal governance in the public sector as the country transitioned from communist party rule to a market economy. Poland’s centrally planned government healthcare system evolved to a social health insurance model with a mixed government-private delivery system. New payment methods such as capitation and diagnosis-related groups were introduced. Dissatisfaction with underfunding of public services which characterised the initial decentralisation led to the recentralisation of purchasing. Today, Poland is the only case study country that has a single national health insurance fund, the National Health Fund (NFZ), which is a hybrid of an internal government ‘purchaser’ and a more independent ‘social health insurance’ agency. Contributions are required for formally employed workers meeting certain requirements and the government subsidises care for other population groups through additional tax-based funding.

Under the centrally planned model, the MOH was the funder, organiser and regulator for healthcare. Resource allocation was input based rather than performance or outcomes based. The establishment of the independent NFZ eliminated the MOH’s role as funder of health services. Some functions previously implemented by the MOH were externalised into separate organisations reflecting capacity and financing issues or inadequate geographical reach of a centralised system. For example, an independent agency for health technology assessment was established to introduce evidence-based analysis in developing the benefits package for the NFZ because the MOH lacked the technical capacity for this function. Decision makers perceived that compensation levels above civil service levels would attract a workforce with the necessary competencies. However, the MOH remains legally responsible and most of these organisations remain formally accountable to the MOH. This allows the MOH to continue its strong role in system governance. Even as the MOH’s official functions were reduced during the reforms, over time the MOH has expanded the scope of its regulatory role. The MOH approves NFZ annual plans and determines key financing and purchasing aspects, including geographical distribution of funds, the benefits package, tariffs, broad purchasing guidelines and quality controls.

Thailand

In the early 2000s, Thailand introduced a new government health insurance, the Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS), for the 75% of the population that was previously uninsured or underinsured, including people not formally employed, or those covered by the Medical Welfare Scheme as well as voluntary community-based health insurance. The National Health Security Office (NHSO) was created as the new government purchaser for the UCS. Technocrats within the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) and political leaders in the Thai Rak Thai Party, which won the 2001 general election, believed that UHC was technically feasible and that the funding gap could be filled by the government. After reform, the MOPH exercised three types of power: official power as the steward of the overall health system of Thailand; managerial power as the owner and operator of the MOPH healthcare service delivery system itself; and power of influence as a strategic partner for the other government insurance schemes. The establishment of NHSO represented the largest change to traditional roles and responsibilities in the government health sector. The NHSO manages funds and purchase services on behalf of UCS beneficiaries through strategic purchasing instead of the internal management mechanisms used by the two other ministries overseeing existing government health insurance programmes covering civil servants and formal employees.

The Minister of Public Health chairs the independent board that oversees the NHSO, with authority over leadership functions such as determining the annual UCS budget and the benefits package. But there are measures that limit the previous direct management authority of the Minister of Public Health. To encourage external accountability and transparency of management, the NHSO board has 30 external members, including five members representing civil society organisations, seven experts, MOPH officials, and permanent secretaries from other line ministries. The Minister of Public Health cannot use traditional command authority with this blended group.

Australia

Unlike the other case study countries, Australia never had a national health service system under central government purview. Its complex system differs in financing and organisation for primary care and hospital service. Primary care is largely a unitary, universal and central government-funded system, although largely privately delivered. Most general practitioners are reimbursed according to fee schedules through the Medicare programme. For hospital services, a mixed government-private insurance approach results in a state-based system. States have authority to manage their hospital systems. Most hospitals are owned and operated by state governments and jointly funded by the federal and state governments. Alongside public insurance, robust policies and financial incentives from the federal government, such as tax penalties against the wealthy for non-participation, encourage enrolment in private health insurance for hospital care.

Different organisations govern different aspects of the health system, but all are linked through a network of policies set by the Federal Department of Health (DOH) for the services outside hospitals, and by the State Departments of Health for services within public hospitals. The DOH sets pricing and other policies for the universal care programme, including the amounts set in the Medicare Benefits Schedule; partially funds service delivery; and provides the policies and funding that maintain enrolment in private insurance through incentives and penalties. The Department of Human Services administers funding and claims in accordance with DOH policies. States fund and provide services within the limits of agreements and policies set by the DOH, directly operating most public hospitals and funding many public and community health services. Recent reforms around quality and integration of primary care have allowed Primary Care Networks to purchase services independently although in accordance with policies set by the federal government.

Learnings relevant to other countries

From this comparative study of organisational transformation within the health sector in four upper and middle-income countries, we identified four observations relevant to other countries. First, no single model emerges for how responsibilities are distributed in health systems after reforms. The changes that result from health system reforms are more complex than the simple reduction or shifting away of MOH authority and responsibilities. There are several explanations for why a country may choose different distributions of roles between organisations or between teams within a single organisation, such as the capacity of MOH or other entities to perform a given responsibility; the need to realign accountability and power with new incentive structures, organisational relationships and political preferences; or the perceived need for independence and transparency. As one example, as Chile decentralised much authority for healthcare delivery to municipal governments, its MOH did not simply reduce its responsibilities, but rather had to develop its capacity to guide, supervise and enforce rules within a system of devolved responsibilities.

Second, the exercise of responsibilities in practice in a health system may differ substantially from the de jure, nominal, or official distribution of those responsibilities. The configuration of responsibilities, power and risk arising from reforms is often not accurately discerned from the formal structures that are in place. Health system reforms often formally incorporate significant institutional and organisational changes such as the movement of financing to a third-party payer or decentralising authorities for healthcare delivery to local governments or individual facilities. However, our case studies suggest that an MOH can retain substantial power and influence in financing and delivery even when formal reforms remove these powers. For example, in Poland the MOH still holds primary legal responsibility for performance of organisations in the sector, even where those organisations are independent of the MOH.

Third, the ability of an MOH to act alone to achieve fundamental system restructuring is limited when such restructuring involves significant organisational transformation. Centrally funded and operated national health service bureaucracies reflect long-standing conditions which impede endogenously driven change. Without political impetus and external buy-in, it is likely that an MOH will rely on management-level reforms within its own authority to try to implement large system changes. The system-wide reforms we examined in this comparative study were not purely managerial or technical in nature and required stakeholder mobilisation from outside the MOH. For example, as seen in the Thailand case, an MOH is unlikely to be able to design or implement institutional change for financing reforms without the ministry of finance.

Fourth, the MOH may use a variety of strategies to shape organisational change that accompanies health systems reform. These include:

Establish a high-level interministerial team to create political commitment to UHC-related reforms as a countervailing force to bureaucratic resistance to change. Particularly in countries where an MOH may be perceived as a ministry with relatively lower power and influence,8 an interministerial platform, with technical guidance from the MOH, could envision the future health system and alleviate institutional barriers to organisational changes in MOH or other agencies.

Establish a ‘change team’9 in the MOH responsible for translating the strategic systems-level decisions into implementable steps for internal organisational change. A change team may enable change in the domain of individuals and teams, by accessing different parts of the organisation and developing a roadmap to navigate and sequence potentially disruptive changes within the bureaucratic structure. In strongly vertical organisations such as an MOH-led national health service, a change team can drive organisational change at the lower levels of the organisation.

Pursue legislation to modify the institutional environment to enable the changes needed in the domain of organisations. When Poland, Chile and Thailand set up third-party purchasers, legislation served to define the functions of new entities and the separation of powers from the MOH. Legislation can preserve key reform components through future political fluctuations.

Capitalise on political ‘windows of opportunity’10 when political change makes it more possible to successfully introduce health reforms and accompanying organisational change. Although this is a more difficult mechanism, it is arguably more successful because comprehensive government reform packages reflect political commitment. Ideally, a change team in MOH would prepare for and identify such political windows and pursue a legislation change to underpin the health system reforms.

Conclusion

This papers adapts an organisational theory approach to understanding the governance and organisational changes within health systems which are an important but overlooked factor to achieving effective UHC. In the highlighted countries, institution-based norms of government power and authority continue to influence de facto governance relationships in the health sector even when de jure organisation restructuring occurs to the MOH and/or a health financing agency. In practice, the governance of health systems relies on power at the levels of both ‘institutions’ and ‘organizations’, to use North’s nomenclature.4 The institution level conveys formal and informal rules, norms, and customs of government bureaucracy and the professional norms of the health cadre regardless of the structures in place; the organisation level reflects the formal organisational responsibilities for the health system that may be restructured during reform. MOHs’ roles and functions both influence and are themselves influenced by these different levels in reform initiatives. MOHs have limited ability on their own to achieve fundamental system restructuring in health systems that are strongly subject to public sector rules and policies.

Within these constraints, our comparative study identifies four mechanisms an MOH can use to drive organisational change: establish a high-level interministerial team to influence the institution level; establish an MOH ‘change team’ within the MOH to lead the implementation of organisational change at the organisation level; secure key components of systemic change through legislation; and leverage emerging political change windows of opportunity for the introduction of health reforms.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Kees van Gool, Mr Ankit Kumar, Mr Robert Wells, Dr Jeanette Vega, Dr Cristian A Herrera, Dr Thomas Bossert, Dr Somsak Chunharas, Dr Walaiporn Patcharanarumol, Dr Jadej Thammatach-Aree, Mr Adam Kozieriewicz, Mr Dariusz Dzielak, Ms Anna Koziel, Professor Rifat Atun, Professor William Hsiao, Professor Winnie Yip and our colleagues in the Ministry of Health of Malaysia who participated in online seminars and review meetings for their insights and feedback that assisted the research.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: All authors contributed to the planning, conduct and reporting of the work described in the article. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This study was funded by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Global Health and Population. This research was conducted under the Malaysia Health Systems Research study, sponsored by the Ministry of Health of Malaysia under agreement 'KKM.400-5/2/14 Jld 2' on 15 December 2016. This research was developed in consultation with the Ministry of Health of Malaysia, which has access to research data. All decisions on technical aspects of the study and reporting belong to the authors.

Competing interests: All authors had financial support from the Ministry of Health of Malaysia for the submitted work.

Patient and public involvement statement: This research was done without patient and public involvement. Patients and the public were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient-relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients and the public were not invited to contribute to the writing and editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This research received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health under protocol number IRB15-1581, on 10 August 2017.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

- 1. World Health Organization Tracking universal health coverage: 2017 Global Monitoring Report [Internet], 2017. Available: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/universal_health_coverage/report/2017/en/ [Accessed 10 Aug 2018].

- 2. Cotlear D, Nagpal S, Smith O, et al. . Going universal: how 24 countries are implementing universal health coverage reforms from the bottom up. Washington, DC: World Bank Group, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bossert T, Hsiao W, Barrera M, et al. . Transformation of ministries of health in the era of health reform: the case of Colombia. Health Policy Plan 1998;13:59–77. 10.1093/heapol/13.1.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. North DC. Institutions. J Econ Perspect 1991;5:97–112. 10.1257/jep.5.1.97 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a Handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010: 92. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization World Health Report 2000: Health systems: improving performance [Internet], 2000. Available: http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/ [Accessed 10 Aug 2018].

- 7. Roberts MJ, Hsiao W, Berman P, et al. . Getting health reform right: a guide to improving performance and equity [Internet. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:OSOPUB_011808231 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Omaswa F, Boufford JI, African Centre for Global Health and Social Transformation, New York Academy of Medicine . Strong ministries for strong health systems: handbook for ministers of health [Internet]. Kampala, Uganda; New York: African Centre for Global Health and Social Transformation; New York Academy of Medicine, 2014. Available: http://www.nyam.org/news/docs/pdf/SM-Handbook-070114.pdf [Accessed 10 Aug 2019].

- 9. Gonzalez-Rosetti A, Bossert T. Enhancing the political feasibility of health reform: a comparative analysis of Chile, Colombia, Mexico, 2000. Available: https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=4fc8178a-816f-4030-9ca5-65c99f96cb4b [Accessed 22 Oct 2018].

- 10. Kingdon JW. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. 2nd ed New York: Longman, 1995: 253 14–253. [Google Scholar]