Abstract

Collagens are extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins that support the structural and biomechanical integrity of many tissues. Procollagen-lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 2 (PLOD2) encodes the only lysyl hydroxylase (LH) isoform that specifically hydroxylates lysine residues in collagen telopeptides, a post-translational modification required for the formation of stabilized cross-links. PLOD2 expression is induced by hypoxia and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), well-known stimuli for the formation of a fibrotic ECM, which can lead to pathological fibrosis underlying several diseases. Here, using human and murine fibroblasts, we studied the molecular determinants underlying hypoxia– and TGF-β1–induced PLOD2 expression and its impact on collagen biosynthesis. Deletion mapping and mutagenesis analysis identified specific binding sites for hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF) and TGF-β1–activated SMAD proteins on the human PLOD2 gene promoter that were required for these stimuli to induce PLOD2 expression. Interestingly, our experiments also revealed that HIF signaling plays a preponderant role in the SMAD pathway, as intact HIF sites were absolutely required for TGF-β1 to exert its effect on SMAD-binding sites. We also found that silencing PLOD2 expression did not alter soluble collagen accumulation in the extracellular medium, but it effectively abolished the deposition into the insoluble collagen matrix. Taken together, our findings reveal the existence of a hierarchical relationship between the HIF and SMAD signaling pathways for hypoxia– and TGF-β1–mediated regulation of PLOD2 expression, a key event in the deposition of collagen into the ECM.

Keywords: collagen, extracellular matrix (ECM), hypoxia, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta), fibrosis, lysyl hydroxylase, procollagen-lysine 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 2 (PLOD2), pulmonary fibroblast, telopeptide hydroxylation

Introduction

Collagens represent a large family of extracellular matrix (ECM)2 proteins that play an essential role in providing the structural and biomechanical integrity of different tissues. 28 types of collagens (I–XXVIII) have been described in vertebrates, which are divided into several families, the most important being fibrillar collagens (I–III, V, XI, XXIV, and XXVII) and basement membrane–forming collagen IV (1). Fibrillar collagens form homotrimeric (three identical α-chains) or heterotrimeric (two or three distinct polypeptide chains) molecules, each α-chain consisting of a major uninterrupted triple-helical or collagenous domain characterized by repeating sequences (GXY), flanked by noncollagenous domains at N and C termini (2).

One of the prevalent features of collagen is its extensive post-translational modifications, most of which are unique to collagen protein (3). Among the reactions occurring intracellularly, the hydroxylation of specific proline and lysine residues is critical for the structural integrity of the ECM (4). These reactions, which occur before the formation of the triple helix, are catalyzed by prolyl and lysyl hydroxylases, enzymes that reside in the endoplasmic reticulum and require Fe2+, 2-oxoglutarate, O2, and ascorbate for their activity. In contrast to proline hydroxylation, described to be invariable among several types of collagen in different tissues, the extent of lysyl hydroxylation can vary significantly, depending on the collagen form, the domain where it takes place, the tissue considered, and even the pathophysiological conditions (5). This variable behavior actually comes from the fact that different enzymatic systems contribute to this post-translational modification. Three isoforms of lysyl hydroxylases (LH; EC 1.14.11.4), also known as procollagen-lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase (PLOD), have been described in vertebrates: LH1, LH2, and LH3, encoded by PLOD1, PLOD2, and PLOD3 genes, respectively (6–9). Genetic diseases resulting from defects in these genes have provided valuable information about their biological role. Thus, human mutations in PLOD1 causes Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (EDS) type VIA, a connective tissue disease characterized by hypermobile joints, hyperextensible skin, and kyphoscoliosis (10). EDS-VIA patients show a decreased level of hydroxylation in the triple helix of collagen I and III, particularly in lysines involved in cross-linking, indicating that LH1 uses these residues as preferential substrates (11). LH3 also hydroxylates lysines in the helical region, but mostly of collagen types II, IV, and V (12). In fact, LH3 is a multifunctional enzyme possessing LH, galactosyltransferase, and glucosyltransferase activities, which are sequentially required for the formation of glucosylgalactosyl hydroxylysines in collagens (13). Here again, mutations in the LH3-coding gene, PLOD3, have been described that result in the development of severe malformations in multiple tissues and organs, showing many features in common with collagen disorders (14). LH2, for which two alternatively spliced forms were identified, seems to be the genuine LH form hydroxylating lysines in the nonhelical terminal peptides (telopeptides) (9, 15). Lysine and hydroxylysines in collagen telopeptides are substrates for lysyl oxidase, and the resulting aldehydes react with helical lysine or hydroxylysine residues to form covalent cross-links (16, 17). In fact, the biological significance of telopeptide hydroxylation is fundamental, as it impacts the mechanical properties of the collagen network (18). When the use of hydroxylysine over lysine is favored, instead of following the allysine pathway, cross-linking proceeds through the hydroxyallysine route, resulting in enhanced levels of pyridinoline cross-links and, thereby, in a stiffer collagen matrix (19). Strong evidence indicates that LH2 (PLOD2) is the only form determining the formation of stabilized cross-links, as exemplified by Bruck syndrome type 2, a heritable disorder in the osteogenesis imperfecta spectrum caused by mutations in the PLOD2 gene and characterized by severe reduction or elimination of the telopeptide hydroxylysine-derived cross-links, resulting in bone fragility (9). Therefore, it is important to delineate the signaling pathway(s) regulating the expression of PLOD2 as a way to understand the molecular mechanisms contributing to tissue stiffness.

PLOD2 expression has been described to be strongly regulated by transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) and hypoxia, known stimuli for the synthesis and deposition of a fibrotic ECM (20–22). In this study, we analyzed the molecular determinants for the induction of PLOD2 by hypoxia and TGF-β1 in fibroblasts as well as its impact on their capacity to promote collagen synthesis and deposition. Our experiments identified specific binding sites for hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF) and TGF-β–activated SMAD family members on the promoter sequence of the human PLOD2 gene. Mutation analyses and transcription factor overexpression assays further showed that HIF proteins play a preponderant role in the induction of PLOD2 expression, the action of these factors on their binding site being an essential requirement for TGF-β1 to exert its effect on the SMAD-dependent sites. Finally, we demonstrate that the expression of PLOD2 is fundamental for hypoxia and TGF-β1 to promote the deposition of collagen onto the insoluble collagen matrix, our findings providing novel knowledge to understand the mechanisms leading to pathological fibrosis.

Results

Hypoxia and TGF-β1 increase PLOD2 expression through a transcriptionally mediated mechanism

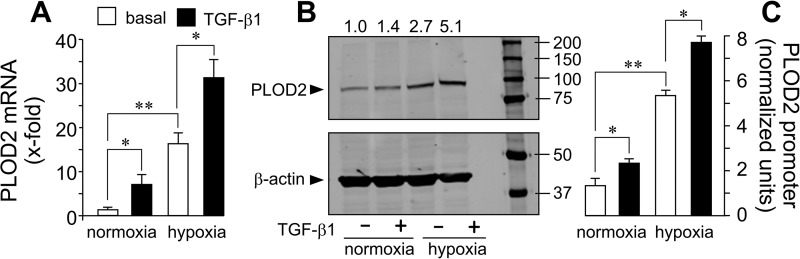

The effect of lowering oxygen levels (hypoxia) and the stimulation with TGF-β1 on PLOD2 expression was investigated in human lung fibroblast (CCD19-Lu) cells. As shown in Fig. 1 (A and B), hypoxia caused an up-regulation in PLOD2 mRNA and protein levels, and this action was further increased by incubation with TGF-β1. As these human fibroblasts are difficult to transfect, we analyzed the mechanism by which hypoxia and TGF-β1 induce PLOD2 expression in 3T3 mouse embryo fibroblasts. An upstream regulatory sequence (−1826/+174) of the human PLOD2 gene was cloned in front of a luciferase gene to study whether the effect of hypoxia and TGF-β1 occurs at the transcriptional level (Fig. S1). Transient transfection of fibroblasts showed that the activity of this promoter fragment recapitulated the behavior of the mRNA and protein (i.e. it was up-regulated by the individual stimuli and further increased when applied together) (Fig. 1C). These experiments indicate that their action occurs at the transcriptional level and that the promoter sequence contains the necessary information to mediate the activation of the gene.

Figure 1.

Hypoxia and TGF-β1 induce PLOD2 expression and promoter activity in fibroblasts. A and B, quantitative PCR of PLOD2 mRNA and Western blotting of PLOD2 protein from human lung fibroblasts treated under hypoxia or normoxia in the absence (basal) or presence of TGF-β1 for 24 h. Housekeeping β-actin protein was also probed by Western blotting for normalization purposes. Numbers above the blot represent the signal ratio PLOD2/β-actin upon densitometric analysis. Data are mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 6): **, p < 0.01 versus normoxia; *, p < 0.05 versus basal. C, PLOD2 gene promoter (−1826/+174) activation as assessed by luciferase reporter in mouse 3T3 fibroblasts treated with TGF-β1 or basal under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Data are mean ± S.D. (n = 6): **, p < 0.05; *, p < 0.05. Statistical comparisons between groups were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-test.

Hypoxia– and TGF-β1–responsive elements in the human PLOD2 promoter are responsible for the induction of PLOD2 expression

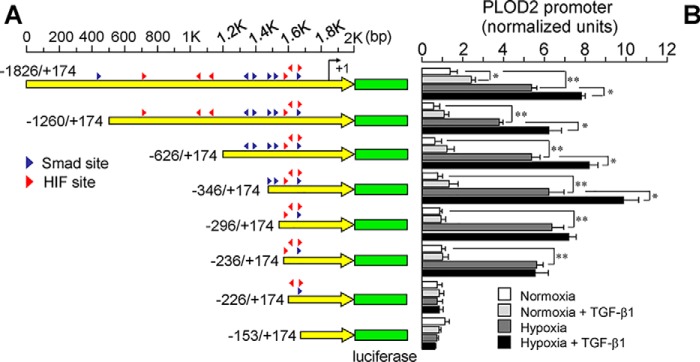

To identify hypoxia– and TGF-β1–responsive elements within the PLOD2 promoter fragment, we screened the −1826/+174 bp promoter region for putative binding sites for HIF and SMAD proteins, both of which have been described to be important for the effect of these stimuli on gene expression (23, 24) (Fig. S1). We then generated luciferase constructs under the control of 5′-deletional fragments based on the location of these potential sites. Looking at the effect of hypoxia, Fig. 2 shows that the activity of the −1826/+174 promoter fragment was kept roughly intact until a putative HIF site at −230/−226 was eliminated. For the effect of TGF-β1, a much more complex behavior was observed. Whereas a potentiation on basal and hypoxia-induced conditions was observed for the parental −1826 promoter fragment, the effect on basal activity lost significance in constructs of −1260, −626, and −346, whereas it was still evident under hypoxic conditions. Deletions up to −296 and further downstream were irresponsive to TGF-β1. Taken together, these results suggest the existence of a well-defined HIF site in the PLOD2 promoter, whereas they reveal a high complexity in the effect of TGF-β1, likely reflecting the action on multiple sites.

Figure 2.

Mapping of hypoxia– and TGF-β1–responsive elements within the PLOD2 promoter. A and B, hypoxia– and TGF-β1–dependent activity of luciferase constructs driven by 5′-deletional fragments of the PLOD2 promoter transfected into mouse 3T3 fibroblasts. A, schematic representation of the −1826 to +174 promoter sequence showing the position of putative HIF and SMAD sites (red and blue arrowheads, respectively). B, PLOD2 promoter activity as assessed by luminometry. Data are mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 6): **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05. Statistical comparisons between groups were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-test.

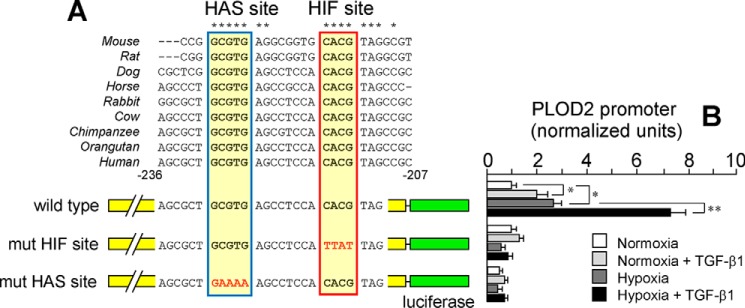

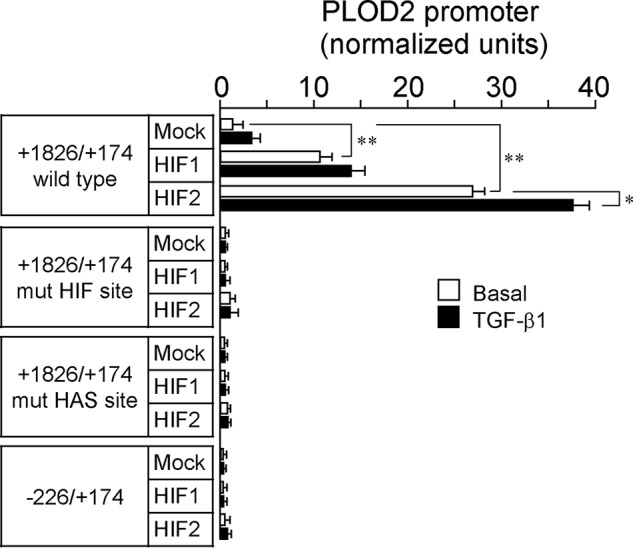

Careful inspection of the putative HIF site indicates a perfect match with the HIF-binding CGTG (complementary strand CACG in the PLOD2 gene) motif commonly found in a number of hypoxia-responsive genes (25) (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, a HIF ancillary sequence (HAS) of the form CACGC (GCGTG in the PLOD2 gene) was also identified. HAS motifs are often found between positions +13 and +15 with respect to the HIF sites and shown to regulate their response to hypoxia (26). Multiple-sequence alignment analysis of this region among several mammalian orthologs of PLOD2 revealed that both HAS and HIF sites were evolutionarily conserved, suggesting functionality in these genomes. In fact, mutation of these sites in the context of the full promoter construct (−1826/+174) abolished the effect of hypoxia and the potentiation by TGF-β1 (Fig. 3B). To demonstrate the absolute requirement of intact HAS and HIF sites for hypoxia to induce PLOD2 promoter activity, constitutively active forms of HIF1 and HIF2 were cotransfected with the promoter constructs, and luciferase activity was analyzed by luminometry. As shown in Fig. 4, HIF1 and HIF2 overexpression caused a strong potentiation of the effect of hypoxia in the WT form, but not in the mutant constructs that behaved similarly to the deletion −226/+174. Again, the effect of TGF-β1 was abolished in these mutant constructs. These results indicate that both HAS and HIF elements are essential for the hypoxia response and mediate the action of HIF factors. Additionally, intact HIF elements seem to be also required for TGF-β1 to induce PLOD2 transcription.

Figure 3.

Characterization of HIF site and HAS within the PLOD2 promoter. A and B, specific point mutations that alter HIF and HAS sites as indicated were introduced in the −1826/+174 promoter, and the effect of hypoxia and TGF-β1 was analyzed in mouse fibroblasts. A, schematic representation of the proximal promoter region showing the location of HIF and HAS sites and multiple-sequence alignment analysis of this region among several mammalian orthologs. Mutations introduced are shown in red. B, PLOD2 promoter activity as assessed by luminometry. Data are mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 6): **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05. Statistical comparisons between groups were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-test.

Figure 4.

Involvement of HIF factors in the effect of hypoxia and TGF-β1 on PLOD2 expression. Luciferase activity of −1826/+174 WT, HIF/HAS mutant, and −226/+174 PLOD2 promoter constructs cotransfected with constitutively active forms of HIF1 and HIF2 in hypoxia– and TGF-β1–treated mouse fibroblasts. Data are mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 6): **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05. Statistical comparisons between groups were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-test.

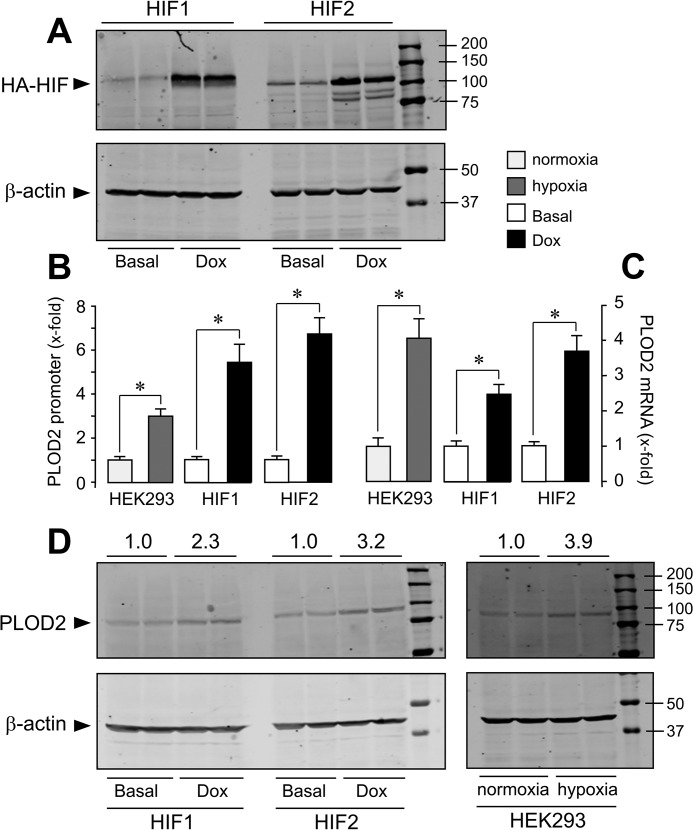

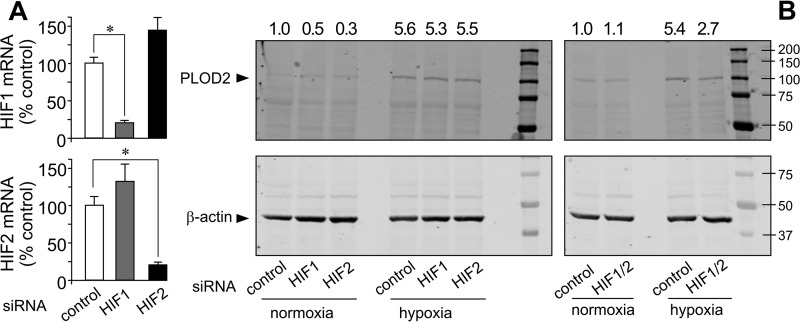

Despite structural and functional similarities, HIF1 and HIF2 exhibit remarkable differences in their transcriptional programs in response to hypoxia (27, 28). HIF1- and HIF2-dependent responses can be mounted in vitro with reporter gene assays that are not observed on endogenous target genes (29). To investigate the contribution of HIF1 and HIF2 on PLOD2 expression, we have generated stable transfectants of human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells overexpressing constitutively active forms of HIF1 and HIF2 (N-terminally HA-tagged) in a tetracycline-inducible manner. As shown in Fig. 5A, incubation of these cell clones with the tetracycline analog, doxycycline, induced the expression of these HIF forms, as assessed by Western blotting using an anti-HA antibody. Cell transfection with PLOD2 promoter-luciferase reporter and subsequent induction of HIF expression gave rise to significant increases in the luciferase activity, which were of a magnitude similar to those induced by hypoxia in untransfected HEK293 cells (Fig. 5B). Therefore, as observed in fibroblasts, HIF1- and HIF2-driven responses on PLOD2 expression can be recapitulated using reporter gene assays in these cells. Interestingly, HIF1 and HIF2 also induced the endogenous expression of PLOD2 mRNA and protein (Fig. 5, C and D). Again, these actions, which were found to be higher with HIF2 than with HIF1, were in the same range of those observed upon hypoxic incubation of untransfected HEK293 cells. Additionally, we have performed knockdown experiments to determine the contribution of HIF1 and HIF2 forms to the effect of hypoxia on PLOD2 expression in fibroblasts. As shown in Fig. 6A, cell transfection with human specific siRNA for HIF1 and HIF2 diminished the mRNA levels of its corresponding HIF form, without significantly affecting the other. Under these conditions, HIF1 or HIF2 siRNA did not modify hypoxic induction of PLOD2 (Fig. 6B, left). As functional redundancy may be operating for the effect of both isoforms, we set additional experiments with a combination of HIF1/HIF2 siRNA. Using this approach, we observed a clear reduction of the capacity of hypoxia to induce the expression of PLOD2 (Fig. 6B, right). Taken together, our results indicate that both HIF1 and HIF2 are fully competent in activating the endogenous expression of PLOD2 and that both HIF forms play redundant roles in the induction of this gene in response to hypoxia.

Figure 5.

Both HIF1 and HIF2 are capable of up-regulating PLOD2 expression. Stable transfectants of HEK293 cells were generated that overexpress constitutively active, HA-tagged forms of HIF1 and HIF2 in a tetracycline-inducible manner. A, HA-HIF1 and HIF2 expression in cell extracts was assessed by Western blotting under basal conditions and upon induction with the tetracycline analogue, Dox. B, PLOD2 promoter activity assessed by reporter gene assays; C, PLOD2 mRNA quantified by quantitative PCR; D, PLOD2 protein analyzed by Western blotting in cells left under basal conditions or overexpressing HIF1 or HIF2. For comparison, the effect of hypoxia on untransfected HEK293 cells is also shown. The expression of the housekeeping β-actin protein was also probed by Western blotting for even loading and normalization purposes. Numbers above the blots represent the signal ratio PLOD2/β-actin upon densitometric analysis. Data are mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 3): *, p < 0.05. Statistical comparisons between groups were calculated using unpaired t test.

Figure 6.

siRNA-mediated down-regulation of HIF1 and HIF2 reduces PLOD2 expression induced by hypoxia in lung fibroblasts. A, HIF1 and HIF2 mRNA assessed by quantitative PCR in cells transfected with HIF1, HIF2, and nontargeting (control) siRNA. Data are mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 6): *, p < 0.05. Statistical comparisons between groups were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-test. B, PLOD2 protein expression was analyzed by Western blotting in cells transfected with control (nontargeting) or HIF1 and HIF2 siRNA, either individually (left) or administered together (right) and treated for 48 h under normoxia or hypoxia. Housekeeping β-actin protein was also probed for normalization purposes. Numbers above the blot represent the signal ratio PLOD2/β-actin upon densitometric analysis.

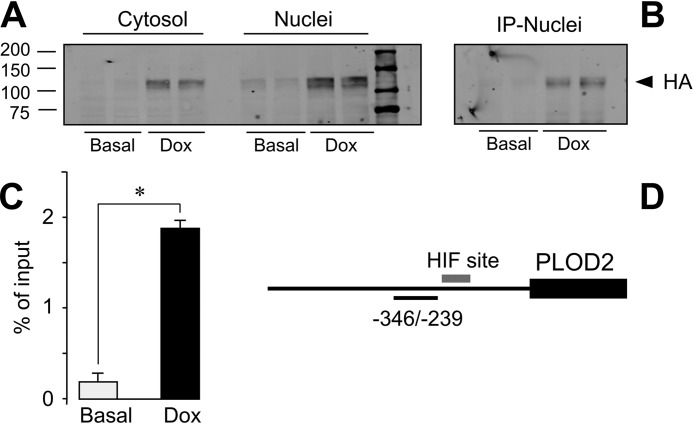

We have also investigated whether HIF factors bind to the PLOD2 promoter. For this purpose, we have taken advantage of the HEK293 clone overexpressing HA-tagged HIF1 in ChIP experiments. As shown in Fig. 7A, incubation of HIF1 cell clone with doxycycline promoted the accumulation in both cytosolic and nuclear compartments of HA-tagged HIF1 protein. Fig. 7B also shows that nuclear HIF1 can be efficiently immunoprecipitated with an anti-HA antibody, a requisite for its performance in ChIP assays. Using a primer pair targeting a PLOD2 genomic sequence adjacent to the HIF-binding site, a significant enrichment for HA-HIF1 was detected in cells treated with doxycycline as compared with those under basal conditions (Fig. 7, C and D). These results support our findings that induction of PLOD2 expression is mediated by transcriptionally active HIF factor. The binding of HIF2 could not be investigated, as the anti-HA antibody failed to immunoprecipitate this HIF form (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Binding of HIF1 to PLOD2 proximal promoter. ChIP experiments of binding of HA-tagged HIF1 to PLOD2 promoter. A, Western blot analysis of cytosolic and nuclear fractions of stable transfectants of HA-HIF1 HEK293 cells incubated in the absence (Basal) or presence of doxycycline (Dox). B, immunoprecipitation (IP) assays of nuclear extracts shown in A with anti-HA antibody coupled to Protein A/G-agarose beads. C, ChIP assay showing the binding of HA-HIF1 to PLOD2 promoter. Data are mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 3): *, p < 0.01. Statistical comparisons between groups were calculated using unpaired t test. D, schematic representation of the position of ChIP amplification quantitative PCR product within the PLOD2 genomic sequence.

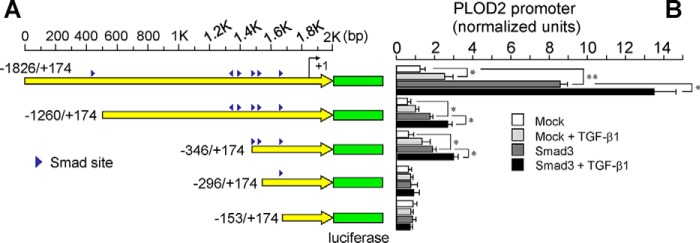

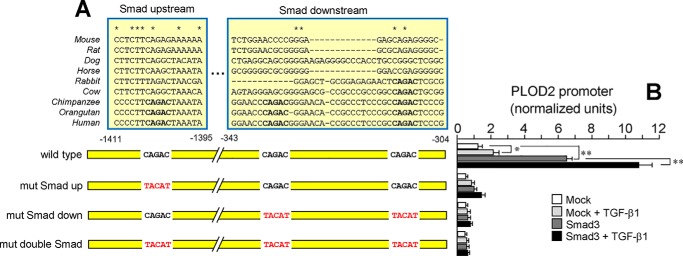

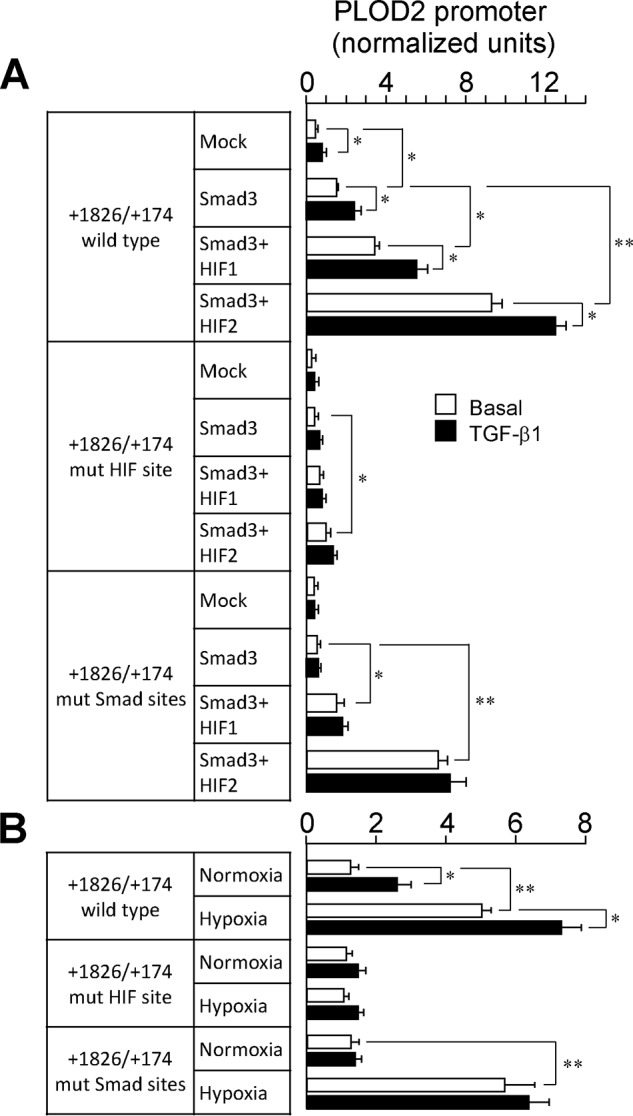

Our experiments showed an absolute requirement of a functional HIF site for TGF-β1 to exert its action on PLOD2 expression. To analyze the molecular basis of this behavior, we cotransfected a vector for the overexpression of SMAD3 together with a series of deletion constructs of PLOD2 promoter based on the location of potential TGF-β1–responsive SMAD elements. As shown in Fig. 8, basal and TGF-β1–stimulated activities were strongly amplified by overexpression of SMAD3 in the parental −1826 promoter fragment. A similar effect, but much more attenuated, was observed for constructs −1260 and −346, whereas downstream fragments remained unmodified. Therefore, the use of this approach revealed the existence of two distinct TGF-β1–responsive elements within the PLOD2 promoter, a distal SMAD site of the form CAGAC at position −1405/−1401 and a proximal region with two closely located CAGAC motifs at −337/−333 and −313/−309 (Fig. 9A). Mutant constructs altering these SMAD sites were tested under overexpression of SMAD3 or mock. Fig. 9B shows that the potentiation observed in the WT promoter was strongly diminished in the vectors harboring these mutations either individually or combined, these results indicating the absolute requirement of both DNA regions for a full response to TGF-β1. Remarkably, multiple-sequence alignment showed that, except for one proximal CAGAC site present in the rabbit and bovine genomes, full conservation of these SMAD sites was only found in hominidae, an observation that predicts that the PLOD2 gene may not respond to TGF-β1 in mammalian species other than this family.

Figure 8.

SMAD3 overexpression reveals the existence of two distinct TGF-β1–responsive elements within the PLOD2 promoter. A and B, luciferase activity of 5′-deletional fragments of the PLOD2 promoter cotransfected with SMAD3 in mouse fibroblasts treated with TGF-β1 or vehicle. A, schematic representation of the −1826 to +174 promoter sequence showing the position of putative SMAD sites (blue arrowheads). B, PLOD2 promoter activity as assessed by luminometry. Data are mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 6): **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05. Statistical comparisons between groups were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-test.

Figure 9.

Characterization of TGF-β1–activated SMAD sites within the PLOD2 promoter. A and B, specific point mutations that alter SMAD sites as indicated were introduced in the −1826/+174 promoter, and the effect of SMAD3 overexpression and TGF-β1 was analyzed in mouse fibroblasts. A, schematic representation of the promoter region showing the location of SMAD sites and multiple-sequence alignment analysis of these regions among several mammalian orthologs. Mutations introduced are shown in red. B, PLOD2 promoter activity as assessed by luminometry. Data are mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 6): **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05. Statistical comparisons between groups were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-test.

Hypoxia-inducible factors play a preeminent role in the functional cooperation between HIF and SMAD proteins that controls PLOD2 expression

Our results so far have revealed the existence of hypoxia– and TGF-β1–responsive elements within the PLOD2 promoter and suggested a coordinated regulation for the induction of the gene by these stimuli. To get deep into this potential mechanism, we performed overexpression experiments with HIF1, HIF2, and SMAD3 using constructs with mutations in HIF and SMAD sites. As shown in Fig. 10A, combination of SMAD3 with HIF1 or HIF2 gave rise to a potentiation of the reporter activity in the WT promoter fragment, which was further increased by incubation with TGF-β1. However, a construct mutated in the HIF site, displaying a drastic reduction in the capacity of HIF1/HIF2 to activate transcription, proved incapable of responding to SMAD3 in the absence or presence of TGF-β1. On the contrary, the promoter fragment with mutations in the SMAD sites, irresponsive to SMAD3 overexpression or TGF-β1 incubation, displayed strong increases by HIF1 and HIF2. In a similar behavior, the mutant in the SMAD sites was still up-regulated by hypoxia, whereas the HIF mutant, as shown above, did not respond to TGF-β1 (Fig. 10B). These results indicate a functional hierarchy in the action of both transcription factors on PLOD2 promoter, with HIF factors dominating the effect of TGF-β1–stimulated SMAD proteins.

Figure 10.

HIF signaling dominates over SMAD pathway in regulating PLOD2 expression. A and B, luciferase activity of −1826/+174 WT, HIF, and SMAD mutant PLOD2 promoter constructs cotransfected with HIF1, HIF2, and SMAD3 overexpression plasmids in mouse fibroblasts. PLOD2 promoter activity upon cotransfection of SMAD3 with HIF1/2 plasmids (A) or under normoxia/hypoxia (B) in cells treated with TGF-β1 or basal. Data are mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 6): **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05. Statistical comparisons between groups were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-test.

PLOD2 expression is required for the effect of hypoxia/TGF-β1 on collagen deposition from fibroblast cultures

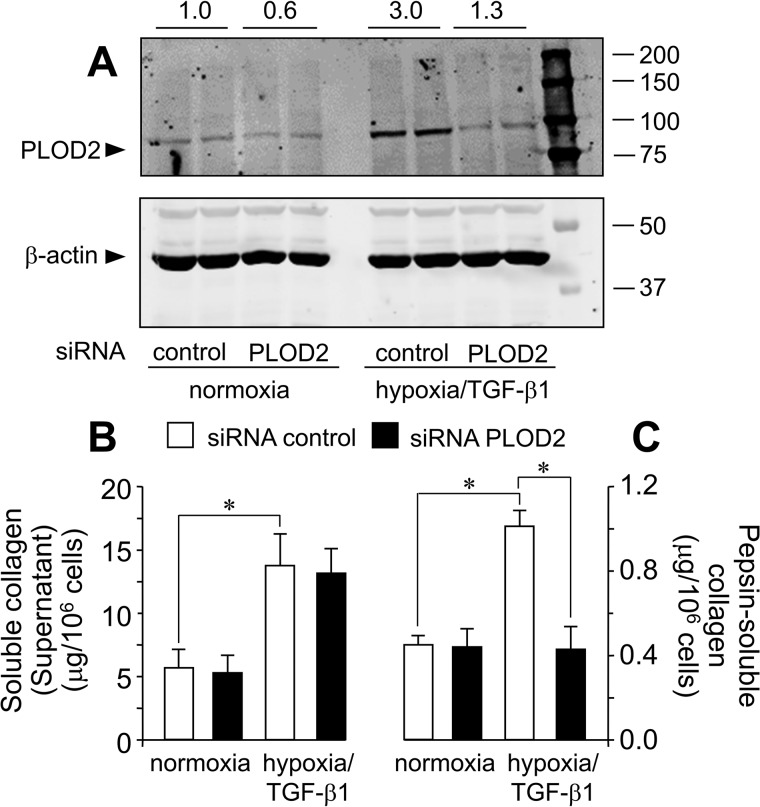

TGF-β1 and hypoxia have been widely reported to contribute to collagen synthesis and deposition in different cell and tissue models (24, 30–32). Nevertheless, the involvement of PLOD2 in this action is poorly understood. To determine whether this profibrotic effect requires PLOD2, we have silenced the expression of this gene by siRNA technology in CCD-19Lu fibroblasts. As opposed to siRNA control, Fig. 11A shows that siRNA PLOD2 abolished hypoxia– and TGF-β1–induced up-regulation of the gene. Having proved the performance of these siRNA molecules, we have then studied the effect of hypoxia and TGF-β1 on collagen expression in siRNA-transfected cells. First, we performed immunofluorescence analyses with an anti-collagen type I, α1 chain (col1α1) antibody (Fig. S2). As shown in Fig. S2, faint col1α1-immunoreactive aggregates were observed in control siRNA-transfected fibroblasts under normoxic conditions that became enlarged and more intense upon incubation with hypoxia/TGF-β1. In contrast, PLOD2-silenced fibroblasts displayed a more diffuse staining that was not significantly modified in cells incubated under hypoxia/TGF-β1. Biochemical studies were also done to analyze the various collagen fractions representing the sequential steps in the biosynthetic process. As shown in Fig. 11B, cells exposed to hypoxia and TGF-β1 for 4 days accumulated in the supernatants higher levels of the soluble form of secreted collagen than those incubated under basal conditions, and no differences were observed in control versus PLOD2 siRNA. In contrast, compared with control, PLOD2 siRNA significantly reduced TGF-β1/hypoxia–induced increase in the levels of pepsin-soluble collagen extracted from cell layers, a fraction that reflects recently cross-linked collagen (Fig. 11C). Under our experimental conditions, cells accumulated very small amounts of pepsin-insoluble collagen, and these were not modified by PLOD2 siRNA (data not shown). Taken together, these results demonstrate an important role for PLOD2 in the effect of hypoxia and TGF-β1 on collagen biosynthesis, specifically affecting the process of its deposition on the extracellular matrix.

Figure 11.

siRNA-mediated down-regulation of PLOD2 reduces collagen deposition in human lung fibroblasts treated with hypoxia and TGF-β1. A, PLOD2 protein expression assessed by Western blotting in cells transfected with PLOD2 or nontargeting (control) siRNA and treated for 48 h with hypoxia/TGF-β1 or basal. Housekeeping β-actin protein was also probed by Western blotting for normalization purposes. Numbers above the blot represent the signal ratio PLOD2/β-actin upon densitometric analysis. Collagen fractions were analyzed in fibroblasts transfected with PLOD2 or control siRNA and incubated under basal conditions or with hypoxia/TGF-β1 for 4 days: soluble collagen in the supernatant (B) or pepsin-solubilized collagen fraction associated with cell monolayer (C). Data are mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 6): **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05. Statistical comparisons between groups were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-test.

Discussion

The ECM constitutes a collection of macromolecules produced and secreted by cells into the surrounding medium that not only provides structural support but also influences a number of cellular processes, including cell proliferation, adhesion, migration, and differentiation (33). Proper synthesis and assembly of the components of the ECM is essential for cell and tissue homeostasis, and therefore, defects or alterations in these processes are associated with the development of several human disorders. Fibrosis, the aberrant accumulation of ECM components, mainly collagens, is the hallmark of a number of chronic diseases, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis or liver cirrhosis, among others (34). TGF-β1 and hypoxic conditions have been widely reported as drivers of fibrosis due to their capacity to increase the expression of matrix components and matrix-remodeling enzymes, including procollagen prolyl and lysyl hydroxylases (20–22, 30–32, 35). Confirming previous observations reporting the capacity of TGF-β1 and hypoxia to individually induce the expression of PLOD2, here we show that both stimuli functionally interact to promote the expression of this gene (20, 21). Our experiments identified specific binding sites for HIF and SMAD transcription factors on the promoter of human PLOD2, implying the activation of HIF- and SMAD-dependent signaling pathways in the induction of the gene. As to the HIF site, whereas genome-wide studies have previously detected the binding of this transcription factor in the vicinity of the PLOD2 proximal promoter, our analysis provided the specific location of this site as well as of its cognate HIF ancillary sequence, demonstrating their functionality (25, 27, 36, 37). We also report here that both HIF1 and HIF2 are fully competent and functionally redundant in activating the expression of PLOD2, a result that is in agreement with previous studies showing that both HIF forms exert a strong influence on the expression of ECM remodeling enzymes in endothelial cells (27). In fact, HIF2, which has been traditionally considered to be expressed exclusively in this cell type, is also found in fibroblasts and other cells of mesenchymal phenotype, as can be visualized in a recent single-cell transcriptomic analysis of mouse organs (38). Therefore, HIF2, together with the ubiquitously expressed HIF1, can significantly contribute to the fibrotic response to hypoxia. With respect to the effect of TGF-β1, previous studies have identified SMAD2/3-binding regions in the PLOD2 locus in HepG2 hepatoblastoma cells and HaCaT epidermal keratinocytes (39). Similarly, the work by Gjaltema et al. (21) demonstrated binding of SMAD3 to PLOD2 promoter, in this case restricted to the transcriptional start site, rather than at upstream regions. Our studies add to this evidences by unequivocally locating the binding sites for SMAD factors along the PLOD2 promoter. In fact, a remarkable complexity in the manner in which these factors interact with DNA is suggested, as their action requires cooperativity between two independent upstream and downstream locations. Interestingly, our studies also revealed a functional hierarchy in the induction of PLOD2 promoter by activation of HIF and SMAD signaling pathways, with HIF proteins dominating the effect of TGF-β1–stimulated SMAD factors. In this respect, a direct interaction between HIF and SMAD factors has been described previously as being established at genes activated by TGF-β1 and hypoxia, such as endoglin or vascular endothelial growth factor (40, 41). Interestingly, here we observed that the disruption of the HIF site abolished the capacity of TGF-β1 or overexpressed SMAD3 to activate the PLOD2 promoter even in normoxic conditions, suggesting site occupancy by HIF or another hitherto unidentified transcription factor utilizing this site under normoxia. In this line, a certain extent of occupancy of HIF sites by HIF factors in normoxia has been revealed previously by ChIP methodology for several HIF-regulated genes, including PLOD2 (37, 42, 43) (ArrayExpress accession number E-GEOD-81635). It is at present unknown which molecular determinants facilitate the normoxic stabilization of HIF factors on certain promoter-binding sites.

Our data also show that the induction of the expression of PLOD2 is fundamental for TGF-β1 and hypoxia to promote the deposition of collagen into the insoluble ECM. Specifically, the abrogation of PLOD2 expression impaired the accumulation of pepsin-soluble collagen extracted from cell layers, a fraction representing recently cross-linked collagen, whereas it did not modify the accumulation of the soluble form in the conditioned medium. This observation is consistent with the role of PLOD2 as an important determinant of the formation of stabilized cross-links, as demonstrated in models of tumor stroma and fibrosis (18, 19). These pieces of knowledge support the development of inhibitors of LH2/PLOD2 as a therapeutic approach to treat these diseases, together with inhibitors of lysyl oxidases, the enzymatic systems genuinely devoted to collagen cross-linking (44, 45). Interestingly, the expression of the whole set of procollagen prolyl and lysyl hydroxylases, as well as of the most members of the lysyl oxidase family, has been described to be induced by hypoxia, and this action has been shown to coordinately mediate ECM remodeling (22, 35, 46, 47). All of these enzymatic systems require molecular oxygen for the catalysis, and, perhaps not surprisingly, their expression is exquisitely regulated by hypoxic conditions. This observation, which is consistent with the preponderant role of the axis hypoxia/HIF in regulating PLOD2 expression, as evidenced in our work, opposes the general underappreciation of hypoxia, when compared with TGF-β1, as a master regulator of collagen synthesis and deposition.

In conclusion, our studies provide novel insights about the molecular mechanisms by which hypoxia and TGF-β1 regulate the expression of PLOD2 as well as demonstrate an important role of this gene in the deposition of collagen into the ECM, both pieces of knowledge helping us to obtain a better molecular understanding of this pathway in cancer and fibrotic pathologies.

Experimental procedures

Cell culture

Fibroblast cell lines CCD-19Lu (human lung, CCL-210) and NIH/3T3 (mouse embryonic, CRL-1658) were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and maintained in culture using standard methods (48, 49). Tetracycline-inducible HEK293 cells stably expressing constitutively active forms of human hypoxia inducible factors HIF-1α and HIF-2α were generated and maintained in culture according to protocols published previously (50).

RNA expression by quantitative PCR

For RNA experiments, CCD-19Lu fibroblasts were cultured in 60-mm cell culture dishes and incubated at confluence in the absence or presence of 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) under normoxic or hypoxic conditions (1% oxygen, H35 Hypoxystation, Don Whitley Scientific, West Yorkshire, UK). Total RNA was extracted using the RNAeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilde, Germany), the cDNA was synthesized (High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and specific primers for human PLOD2, HIF1, and HIF2 (see Table S1) in a CFX96 thermocycler (Bio-Rad). The mRNA expression of the housekeeping gene hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT) was determined using a TaqMan probe (Hs01003267_m1) and TaqMan Fast Advance Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer's instructions, and data normalization was performed with the ΔΔCt method (51).

Western blotting analyses

For protein studies, CCD-19Lu fibroblasts were cultured in 100-mm cell culture dishes and processed essentially as described previously (52). Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and lysed with Tris-SDS buffer (60 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS) to obtain total cell lysate. Protein concentration was determined by the BCATM protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Even amounts of protein (30 μg) were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and fractioned proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes at 25 V for 20 min in a semi-dry Trans-Blot Turbo system (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked by incubation for 30 min with 1% BSA in PBS containing 0.5% Tween 20, and antigens were detected using specific primary antibodies (PLOD2: mouse polyclonal, Abcam, Cambridge, UK; β-actin: mouse monoclonal, Sigma; hemagglutinin (HA) tag: Biolegend, San Diego, CA). Blots were then incubated with the corresponding IRDye secondary antibodies and detected using the Odyssey IR imaging system (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE).

Construction of PLOD2 gene promoter reporter constructs and cell transfection

Analysis of PLOD2 gene transcriptional activity was performed by luciferase reporter gene studies using genomic fragments of the PLOD2 gene. A human PLOD2 promoter fragment (chr3: 146,160,994–146,162,989, reverse strand, containing partial exon 1 and 5′-flanking sequences up to position −1826 with respect to the transcription start site; Fig. S1) was obtained as a clone in the vector pCpG-PLOD2-2000 (a gift from Rutger A. F. Gjaltema and Ruud A. Bank, University of Groningen, The Netherlands) (21). A pGL3-luciferase cassette under the control of the PLOD2 promoter (pGL3-PLOD2−1826/+174) was generated by insertion of this fragment into pGL3-vector (Promega, Madison, WI) by standard cloning procedures. Preliminary attempts to generate 5′-deletional fragments of the PLOD2 promoter based on Pfu-based PCR using this construct were unsuccessful, likely due to the presence of a high GC sequence in the proximal promoter. Therefore, a shorter promoter construct was generated by restriction cutting at a 5′-end SacI site in the vector and a 3′-end ApaI site in the promoter, right upstream of the GC-rich sequence, and further religation to yield pGL3-PLOD2−153/+174. The upstream promoter fragment (−1826/−154) was subcloned into pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen), and deletion fragments thereof starting at positions ranging from −1826 to −154 were generated by Pfu-based PCR. They were then excised by restriction cutting and cloned into pGL3-PLOD2−153/+174 (upstream of the proximal promoter) to yield the series of pGL3-PLOD2 constructs used in this study (primers used shown in Table S2). Reporter luciferase constructs under the control of promoter fragments with specific mutations in HIF and HAS sites, as well as in the SMAD-binding elements, were generated by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis within pCR2.1-PLOD2−1826/−154 and then assembled into the luciferase reporter-proximal promoter plasmid as described above (primers in Table S2). All constructs were verified by sequencing.

The vectors expressing constitutively active forms of human hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1α (P402A/P564A-pcDNA3, N-terminally HA-tagged) and HIF-2α (P405A/P531A-pcDNA3, N-terminally HA-tagged) were a gift from William Kaelin (Addgene plasmids 18955 and 18956) (53). The vector expressing SMAD3 transcription factors was kindly provided by Liliana Attisano (Toronto, Canada).

DNA constructs were transiently transfected into 3T3 fibroblasts seeded on 24-well plates (60–70% confluence), and promoter activity was estimated by luminometry as described previously using pRL-CMV plasmid (a Renilla luciferase under the control of the cytomegalovirus promoter) for normalization purposes (52).

Sequence alignments for the identification of potential conserved transcription factor–binding sites were performed with Clustal Omega at the European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI). PLOD2 orthologous sequences from Mus musculus, Rattus norvegicus, Canis familiaris, Equus caballus, Oryctolagus cuniculus, Bos taurus, Pan troglodytes, and Pongo pygmaeus were obtained from the ENSEMBL genome database.

ChIP

ChIP experiments were performed using a commercially available kit (Abcam) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, stable transfectants of HEK293 cells were treated with doxycycline to induce the expression of HA-tagged HIF1 or left under vehicle. Afterward, they were trypsinized and washed with PBS buffer and then resuspended for fixation in 1% formaldehyde (Calbiochem). Glycine was added to quench the excess of formaldehyde, and cells were washed with PBS, resuspended in lysis buffer, and sonicated using a Bioruptor system (Diagenode, Liège, Belgium). After removal of a control aliquot (input), sheared chromatin was incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody (clone 12CA5) or negative control IgG. Protein A/G Plus-agarose beads were then added, incubated for 2 h and extensively washed before chromatin was released by proteinase K digestion and DNA was recovered using a DNA-purifying slurry. DNA was used for amplification of a region of 108 bp in a location adjacent to the HIF site by real-time quantitative PCR (see Table S3). ChIP data were calculated as percentage of input after IgG background subtraction.

siRNA-mediated inhibition of HIF1, HIF2, and PLOD2 expression

Specific siRNA for the inhibition of the expression of human PLOD2, HIF1, HIF2, and nontargeting control was purchased from Ambion (Silencer® Select siRNA, negative control 1 siRNA, catalog no. 4390843; for PLOD2, see Table S4, Life Technologies, Inc.). siRNA transfection in CCD-19Lu fibroblasts was performed with INTERFERin® reagent (Polyplus, Strasbourg, France), following the manufacturer's instructions, in 6-well plates and 100-mm cell culture dishes for immunoblotting and collagen analyses, respectively.

Collagen analysis

Collagen fractions were extracted from CCD-19Lu fibroblast cultures that represent the sequential steps in the biosynthetic process using a protocol described previously (54). Briefly, after 4 days of incubation under basal or hypoxia/TGF-β1–stimulated conditions, cell supernatants were collected, and soluble collagen was measured upon concentration with a Sircol soluble collagen assay (Biocolor, Carrickfergus, UK) following the manufacturer's instructions. On the other hand, cell layers were scraped and extracted overnight with acid-based buffer (0.5 m acetic acid), and resulting pellets were digested with 0.5 mg/ml pepsin (Sigma-Aldrich) in 10 mm HCl. Corresponding solubilized fractions were analyzed for collagen with Sircol. Insoluble collagen after pepsin digestion was hydrolyzed at 100 °C for 16 h with 12 m HCl, neutralized with NaOH, and analyzed by a hydroxyproline assay using hydrolyzed type I collagen as a standard (55).

Fluorescence microscopy was performed as described previously (54). Briefly, cells were seeded onto 10-mm glass diameter coverslips (no. 1.5) in 35-mm culture dishes (Mattek, Ashland, MA). After the corresponding treatment, cells were fixed with cold methanol for 5 min, blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 h, and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-collagen α1 type I antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), followed by the corresponding fluorescent secondary antibody. Nuclear staining was performed with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Fluorescence was visualized by microscopy with a Nikon Eclipse T2000U (Nikon, Amstelveen, The Netherlands).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. of n independent measurements as indicated in the corresponding figure legends. Statistical comparisons between groups were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-test for multiple-group comparisons or with an unpaired t test in the case of two samples using GraphPad Prism version 6. The p values obtained are indicated in the figure legends when statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Author contributions

T. R.-G. and F. R.-P. conceptualization; T. R.-G. and F. R.-P. data curation; T. R.-G., O. P.-Á., and F. R.-P. investigation; T. R.-G., O. P.-Á., and F. R.-P. methodology; T. R.-G. and F. R.-P. writing-original draft; T. R.-G. and F. R.-P. writing-review and editing; F. R.-P. resources; F. R.-P. formal analysis; F. R.-P. supervision; F. R.-P. funding acquisition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rutger A. F. Gjaltema and Ruud A. Bank (University of Groningen, The Netherlands) for providing the plasmid pCpG-PLOD2-2000.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (Plan Nacional de I+D+I: SAF2015-65679-R) (to F. R.-P.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Tables S1–S4 and Figs. S1 and S2.

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- LH

- lysyl hydroxylase(s)

- PLOD

- procollagen-lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase

- EDS

- Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

- TGF

- transforming growth factor

- HIF

- hypoxia-inducible factor(s)

- HAS

- HIF ancillary sequence

- HEK293

- human embryonic kidney 293.

References

- 1. Kadler K. E., Baldock C., Bella J., and Boot-Handford R. P. (2007) Collagens at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 120, 1955–1958 10.1242/jcs.03453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fratzl P. (2008) Collagen: Structure and mechanics, an introduction. in Collagen (Fratzl P., ed) pp. 1–13, Springer, New York [Google Scholar]

- 3. Trackman P. C. (2005) Diverse biological functions of extracellular collagen processing enzymes. J. Cell. Biochem. 96, 927–937 10.1002/jcb.20605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gjaltema R. A. F., and Bank R. A. (2017) Molecular insights into prolyl and lysyl hydroxylation of fibrillar collagens in health and disease. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 52, 74–95 10.1080/10409238.2016.1269716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yamauchi M., and Sricholpech M. (2012) Lysine post-translational modifications of collagen. Essays Biochem. 52, 113–133 10.1042/bse0520113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Valtavaara M., Papponen H., Pirttilä A.-M., Hiltunen K., Helander H., and Myllylä R. (1997) Cloning and characterization of a novel human lysyl hydroxylase isoform highly expressed in pancreas and muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 6831–6834 10.1074/jbc.272.11.6831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Valtavaara M., Szpirer C., Szpirer J., and Myllylä R. (1998) Primary structure, tissue distribution, and chromosomal localization of a novel isoform of lysyl hydroxylase (lysyl hydroxylase 3). J. Biol. Chem. 273, 12881–12886 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mercer D. K., Nicol P. F., Kimbembe C., and Robins S. P. (2003) Identification, expression, and tissue distribution of the three rat lysyl hydroxylase isoforms. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 307, 803–809 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01262-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van der Slot A. J., Zuurmond A.-M., Bardoel A. F. J., Wijmenga C., Pruijs H. E. H., Sillence D. O., Brinckmann J., Abraham D. J., Black C. M., Verzijl N., DeGroot J., Hanemaaijer R., TeKoppele J. M., Huizinga T. W. J., and Bank R. A. (2003) Identification of PLOD2 as telopeptide lysyl hydroxylase, an important enzyme in fibrosis. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 40967–40972 10.1074/jbc.M307380200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yeowell H. N., and Walker L. C. (2000) Mutations in the lysyl hydroxylase 1 gene that result in enzyme deficiency and the clinical phenotype of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome type VI. Mol. Genet. Metab. 71, 212–224 10.1006/mgme.2000.3076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ihme A., Krieg T., Nerlich A., Feldmann U., Rauterberg J., Glanville R. W., Edel G., and Müller P. K. (1984) Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VI: collagen type specificity of defective lysyl hydroxylation in various tissues. J. Invest. Dermatol. 83, 161–165 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12263502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ruotsalainen H., Sipilä L., Vapola M., Sormunen R., Salo A. M., Uitto L., Mercer D. K., Robins S. P., Risteli M., Aszodi A., Fässler R., and Myllylä R. (2006) Glycosylation catalyzed by lysyl hydroxylase 3 is essential for basement membranes. J. Cell Sci. 119, 625–635 10.1242/jcs.02780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Myllylä R., Wang C., Heikkinen J., Juffer A., Lampela O., Risteli M., Ruotsalainen H., Salo A., and Sipilä L. (2007) Expanding the lysyl hydroxylase toolbox: new insights into the localization and activities of lysyl hydroxylase 3 (LH3). J. Cell. Physiol. 212, 323–329 10.1002/jcp.21036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Salo A. M., Cox H., Farndon P., Moss C., Grindulis H., Risteli M., Robins S. P., and Myllylä R. (2008) A connective tissue disorder caused by mutations of the lysyl hydroxylase 3 gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 83, 495–503 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Uzawa K., Grzesik W. J., Nishiura T., Kuznetsov S. A., Robey P. G., Brenner D. A., and Yamauchi M. (1999) Differential expression of human lysyl hydroxylase genes, lysine hydroxylation, and cross-linking of type I collagen during osteoblastic differentiation in vitro. J. Bone Miner. Res. 14, 1272–1280 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.8.1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pornprasertsuk S., Duarte W. R., Mochida Y., and Yamauchi M. (2004) Lysyl hydroxylase-2b directs collagen cross-linking pathways in MC3T3-E1 cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 19, 1349–1355 10.1359/JBMR.040323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yamauchi M., and Shiiba M. (2008) Lysine hydroxylation and cross-linking of collagen. Methods Mol. Biol. 446, 95–108 10.1007/978-1-60327-084-7_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen Y., Terajima M., Yang Y., Sun L., Ahn Y.-H., Pankova D., Puperi D. S., Watanabe T., Kim M. P., Blackmon S. H., Rodriguez J., Liu H., Behrens C., Wistuba I. I., Minelli R., et al. (2015) Lysyl hydroxylase 2 induces a collagen cross-link switch in tumor stroma. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 1147–1162 10.1172/JCI74725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van der Slot A. J., Zuurmond A. M., van den Bogaerdt A. J., Ulrich M. M., Middelkoop E., Boers W., Karel Ronday H., DeGroot J., Huizinga T. W., and Bank R. A. (2004) Increased formation of pyridinoline cross-links due to higher telopeptide lysyl hydroxylase levels is a general fibrotic phenomenon. Matrix Biol. 23, 251–257 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gilkes D. M., Bajpai S., Chaturvedi P., Wirtz D., and Semenza G. L. (2013) Hypoxia-inducible Factor 1 (HIF-1) promotes extracellular matrix remodeling under hypoxic conditions by inducing P4HA1, P4HA2, and PLOD2 expression in fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 10819–10829 10.1074/jbc.M112.442939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 21. Gjaltema R. A. F., de Rond S., Rots M. G., and Bank R. A. (2015) Procollagen lysyl hydroxylase 2 expression is regulated by an alternative downstream transforming growth factor β-1 activation mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 28465–28476 10.1074/jbc.M114.634311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hofbauer K.-H., Gess B., Lohaus C., Meyer H. E., Katschinski D., and Kurtz A. (2003) Oxygen tension regulates the expression of a group of procollagen hydroxylases. Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 4515–4522 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03846.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dunn L. K., Mohammad K. S., Fournier P. G., McKenna C. R., Davis H. W., Niewolna M., Peng X. H., Chirgwin J. M., and Guise T. A. (2009) Hypoxia and TGF-β drive breast cancer bone metastases through parallel signaling pathways in tumor cells and the bone microenvironment. PLoS One 4, e6896 10.1371/journal.pone.0006896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Basu R. K., Hubchak S., Hayashida T., Runyan C. E., Schumacker P. T., and Schnaper H. W. (2011) Interdependence of HIF-1α and TGF-β/Smad3 signaling in normoxic and hypoxic renal epithelial cell collagen expression. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 300, F898–F905 10.1152/ajprenal.00335.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schödel J., Oikonomopoulos S., Ragoussis J., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J., and Mole D. R. (2011) High-resolution genome-wide mapping of HIF-binding sites by ChIP-seq. Blood 117, e207–e217 10.1182/blood-2010-10-314427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kimura H., Weisz A., Ogura T., Hitomi Y., Kurashima Y., Hashimoto K., D'Acquisto F., Makuuchi M., and Esumi H. (2001) Identification of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 ancillary sequence and its function in vascular endothelial growth factor gene induction by hypoxia and nitric oxide. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 2292–2298 10.1074/jbc.M008398200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Downes N. L., Laham-Karam N., Kaikkonen M. U., and Ylä-Herttuala S. (2018) Differential but complementary HIF1α and HIF2α transcriptional regulation. Mol. Ther. 26, 1735–1745 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koh M. Y., and Powis G. (2012) Passing the baton: the HIF switch. Trends Biochem. Sci. 37, 364–372 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hu C.-J., Sataur A., Wang L., Chen H., and Simon M. C. (2007) The N-terminal transactivation domain confers target gene specificity of hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1α and HIF-2α. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 4528–4542 10.1091/mbc.e06-05-0419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hanna C., Hubchak S. C., Liang X., Rozen-Zvi B., Schumacker P. T., Hayashida T., and Schnaper H. W. (2013) Hypoxia-inducible factor-2α and TGF-β signaling interact to promote normoxic glomerular fibrogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 305, F1323–F1331 10.1152/ajprenal.00155.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen C. P., Yang Y. C., Su T. H., Chen C. Y., and Aplin J. D. (2005) Hypoxia and transforming growth factor-β1 act independently to increase extracellular matrix production by placental fibroblasts. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 1083–1090 10.1210/jc.2004-0803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. González-Santamaría J., Villalba M., Busnadiego O., López-Olañeta M. M., Sandoval P., Snabel J., López-Cabrera M., Erler J. T., Hanemaaijer R., Lara-Pezzi E., and Rodríguez-Pascual F. (2016) Matrix cross-linking lysyl oxidases are induced in response to myocardial infarction and promote cardiac dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Res. 109, 67–78 10.1093/cvr/cvv214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Engel J., and Chiquet M. (2011) An overview of extracellular matrix structure and function. in The Extracellular Matrix: An Overview (Mecham R. P., ed) pp. 1–39, Springer-Verlag, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wynn T. A. (2007) Common and unique mechanisms regulate fibrosis in various fibroproliferative diseases. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 524–529 10.1172/JCI31487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gilkes D. M., Chaturvedi P., Bajpai S., Wong C. C., Wei H., Pitcairn S., Hubbi M. E., Wirtz D., and Semenza G. L. (2013) Collagen prolyl hydroxylases are essential for breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 73, 3285–3296 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 36. Mimura I., Nangaku M., Kanki Y., Tsutsumi S., Inoue T., Kohro T., Yamamoto S., Fujita T., Shimamura T., Suehiro J., Taguchi A., Kobayashi M., Tanimura K., Inagaki T., Tanaka T., et al. (2012) Dynamic change of chromatin conformation in response to hypoxia enhances the expression of GLUT3 (SLC2A3) by cooperative interaction of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and KDM3A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 3018–3032 10.1128/MCB.06643-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Xia X., Lemieux M. E., Li W., Carroll J. S., Brown M., Liu X. S., and Kung A. L. (2009) Integrative analysis of HIF binding and transactivation reveals its role in maintaining histone methylation homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 4260–4265 10.1073/pnas.0810067106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tabula Muris Consortium, Overall coordination, Logistical coordination, Organ collection and processing, Library preparation and sequencing, Computational data analysis, Cell type annotation, Writing group, Supplemental text writing group, and Principal investigators (2018) Single-cell transcriptomics of 20 mouse organs creates a Tabula Muris. Nature 562, 367–372 10.1038/s41586-018-0590-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mizutani A., Koinuma D., Tsutsumi S., Kamimura N., Morikawa M., Suzuki H. I., Imamura T., Miyazono K., and Aburatani H. (2011) Cell type-specific target selection by combinatorial binding of Smad2/3 proteins and hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α in HepG2 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 29848–29860 10.1074/jbc.M110.217745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sánchez-Elsner T., Botella L. M., Velasco B., Langa C., and Bernabéu C. (2002) Endoglin expression is regulated by transcriptional cooperation between the hypoxia and transforming growth factor-β pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43799–43808 10.1074/jbc.M207160200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sánchez-Elsner T., Botella L. M., Velasco B., Corbí A., Attisano L., and Bernabéu C. (2001) Synergistic cooperation between hypoxia and transforming growth factor-β pathways on human vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 38527–38535 10.1074/jbc.M104536200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Han Z.-B., Ren H., Zhao H., Chi Y., Chen K., Zhou B., Liu Y.-J., Zhang L., Xu B., Liu B., Yang R., and Han Z.-C. (2008) Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α directly enhances the transcriptional activity of stem cell factor (SCF) in response to hypoxia and epidermal growth factor (EGF). Carcinogenesis 29, 1853–1861 10.1093/carcin/bgn066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee M. C., Huang H. J., Chang T. H., Huang H. C., Hsieh S. Y., Chen Y. S., Chou W. Y., Chiang C. H., Lai C. H., and Shiau C. Y. (2016) Genome-wide analysis of HIF-2α chromatin binding sites under normoxia in human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) suggests its diverse functions. Sci. Rep. 6, 29311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schilter H., Findlay A. D., Perryman L., Yow T. T., Moses J., Zahoor A., Turner C. I., Deodhar M., Foot J. S., Zhou W., Greco A., Joshi A., Rayner B., Townsend S., Buson A., and Jarolimek W. (2019) The lysyl oxidase like 2/3 enzymatic inhibitor, PXS-5153A, reduces crosslinks and ameliorates fibrosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 23, 1759–1770 10.1111/jcmm.14074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Devkota A. K., Veloria J. R., Guo H. F., Kurie J. M., Cho E. J., and Dalby K. N. (2019) Development of a high-throughput lysyl hydroxylase (LH) assay and identification of small-molecule inhibitors against LH2. SLAS Discov. 24, 484–491 10.1177/2472555218817057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wong C. C., Gilkes D. M., Zhang H., Chen J., Wei H., Chaturvedi P., Fraley S. I., Wong C. M., Khoo U. S., Ng I. O., Wirtz D., and Semenza G. L. (2011) Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a master regulator of breast cancer metastatic niche formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 16369–16374 10.1073/pnas.1113483108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bentovim L., Amarilio R., and Zelzer E. (2012) HIF1α is a central regulator of collagen hydroxylation and secretion under hypoxia during bone development. Development 139, 4473–4483 10.1242/dev.083881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jainchill J. L., Aaronson S. A., and Todaro G. J. (1969) Murine sarcoma and leukemia viruses: assay using clonal lines of contact-inhibited mouse cells. J. Virol. 4, 549–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Puig M., Lugo R., Gabasa M., Giménez A., Velásquez A., Galgoczy R., Ramírez J., Gómez-Caro A., Busnadiego Ó., Rodríguez-Pascual F., Gascón P., Reguart N., and Alcaraz J. (2015) Matrix stiffening and β1 integrin drive subtype-specific fibroblast accumulation in lung cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 13, 161–173 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rosell-García T., Paradela A., Bravo G., Dupont L., Bekhouche M., Colige A., and Rodriguez-Pascual F. (2019) Differential cleavage of lysyl oxidase by the metalloproteinases BMP1 and ADAMTS2/14 regulates collagen binding through a tyrosine sulfate domain. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 11087–11100 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Livak K. J., and Schmittgen T. D. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Busnadiego O., González-Santamaría J., Lagares D., Guinea-Viniegra J., Pichol-Thievend C., Muller L., and Rodríguez-Pascual F. (2013) LOXL4 is induced by transforming growth factor β1 through Smad and JunB/Fra2 and contributes to vascular matrix remodeling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 2388–2401 10.1128/MCB.00036-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yan Q., Bartz S., Mao M., Li L., and Kaelin W. G. (2007) The hypoxia-inducible factor 2α N-terminal and C-terminal transactivation domains cooperate to promote renal tumorigenesis in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 2092–2102 10.1128/MCB.01514-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rosell-Garcia T., and Rodriguez-Pascual F. (2018) Enhancement of collagen deposition and cross-linking by coupling lysyl oxidase with bone morphogenetic protein-1 and its application in tissue engineering. Sci. Rep. 8, 10780 10.1038/s41598-018-29236-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Reddy G. K., and Enwemeka C. S. (1996) A simplified method for the analysis of hydroxyproline in biological tissues. Clin. Biochem. 29, 225–229 10.1016/0009-9120(96)00003-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.