Abstract

Objective

To describe our experience with office removal of nonpalpable contraceptive implants at our referral center.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study by reviewing the charts of patients referred to our Family Planning specialty center for nonpalpable or complex contraceptive implant removal from January 2015 through December 2018. We localized nonpalpable implants using high-frequency ultrasonography and skin mapping in radiology, followed by attempted removal in the office using local anesthesia and a modified vasectomy clamp. We abstracted information on demographics, implant location, and outcomes.

Results

Of 61 referrals, 55 patients attended their scheduled appointment. Seven patients had palpable implants; six elected removal. The other 48 patients had ultrasound localization, which identified 47 (98%) of the implants; the remaining patient had successful localization with computed tomography imaging. Nonpalpable implants were suprafascial (n=22), subfascial (n=25) and intrafascial (n=1); four of these patients opted to delay removal. Of 50 attempted office removals, all palpable (n=6), all non-palpable suprafascial (n=21 [100%, 95% CI 83–100%]), and 19/23 (83%, 95% CI 67–98%) subfascial implants were successful. Three of the four patients with failed subfascial implant office removal had successful operating room removal with a collaborative orthopedic surgeon; the other patient sought removal elsewhere. Transient postprocedure neuropathic complaints were noted in 7/23 (30%, 95% CI 12–49%) subfascial and 1/21 (5%, 95% CI 0–13%) suprafascial removals (P=.048). Nonpalpable implants were more likely to be subfascial in nonobese (24/34, 71%) as compared to obese (1/13, 8%) patients (P<.001). Seven (28%) of the 25 subfascially located implants had been inserted during a removal–reinsertion procedure through the same incision.

Conclusion

Most nonpalpable contraceptive implants can be removed in the office by an experienced subspecialty health care provider after ultrasound localization. Some patients may experience transient postprocedure neuropathic pain. Nonpalpable implants in thinner women are more likely to be in a subfascial location.

Précis

Most nonpalpable contraceptive implants can be removed in the office by an experienced subspecialty health care provider after ultrasound localization.

INTRODUCTION

Instructions for contraceptive subdermal implant insertion have changed over the past decade, primarily inspired by complications related to deep insertions, including intravascular placement and pulmonary artery migration.1–4 The most recent recommendation for optimal placement is between the dermis and the subcutaneous tissue in the area of the arm over the triceps muscle, with the intent to minimize neurovascular injury should deep insertion inadvertently occur.

Overall, major complications with insertion and removal are exceedingly rare.5 Deep implant insertions are estimated to occur approximately one out of every 1,000 insertions,5,6 similar to the perforation rate of intrauterine devices.7,8 Severe complications associated with deep placement, such as intravascular placement with pulmonary embolization, are estimated to occur in just over one patient per 1 million implants sold.4

Referral to a specialty center with physicians who have expertise localizing and removing nonpalpable implants is essential.9 Health care providers have described various advanced techniques to localize and remove nonpalpable implants;6,9–16 however, the reports typically only include descriptions with a few patients and often involve costly resources such as interventional radiology, fluoroscopy and removal in the operating room.6

In the United Kingdom, the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare established a formal network of expert removal centers more than a decade ago17; however, only in the past few years has a similar specialty removal network been developed in the United States. This network is not outwardly advertised by the etonogestrel implant manufacturer (Merck & Co., Kenilworth, NJ) and a comprehensive description of the experience of any such specialty removal center has never been presented. This report aims to describe the experience of our fellowship-trained Family Planning specialty division as a regional referral center for nonpalpable implant removals. We aim to describe our referral population, clinical outcomes and what we have learned from caring for these patients. This information is important for all contraceptive providers to understand the complexity of such a referral program as well as the advanced techniques and outcomes of nonpalpable implant removals.

METHODS

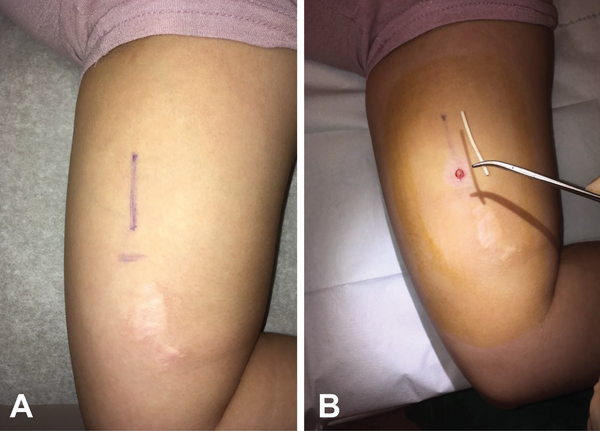

After obtaining institutional review board approval from the University of California, Davis, we performed a retrospective cohort study by reviewing our implant referral clinical log to identify patients referred to our Family Planning specialty clinic in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology for nonpalpable or complex implant removal between January 2015 and December 2018. The first three patients in this series have been previously reported.6 All patients were seen by a Family Planning fellow supervised by a Family Planning attending with fellowship training in nonpalpable implant removals. Patients referred to our program have an initial contact with our Family Planning coordinator who organizes receipt of outside medical records and obtains insurance authorization, often for out-of-network referral and radiologic examinations. If insurance approval is obtained, the patient has a concomitant appointment scheduled in our Family Planning clinic and radiology for an upper extremity ultrasound examination. For a typical appointment, the patient first meets with the specialists who assess reasons for removal, ongoing symptoms or problems related to any prior removal attempts, and if the implant is palpable. Patients with nonpalpable, partially palpable or questionably palpable implants have ultrasound localization in the radiology suite using a 15–18 MHz linear array transducer to evaluate implant relationship to fascia and neurovascular structures; during localization, the Family Planning specialists map the implant location on the skin with a surgical marker (Figure 1). Implant removal then occurs in the office using a technique we have previously described with a modified vasectomy clamp under local anesthesia through an incision that is typically about 5 mm or less.6 While removing the implant, sharp instruments are only used for skin and fascial incisions. Dissection is performed with blunt forceps or a modified vasectomy clamp. Patients with unsuccessful office removal attempts are scheduled for an operating room removal procedure with a collaborative orthopedic surgeon. One of the Family Planning specialists assists for implant identification, as the implant can appear similar to neurovascular structures in the upper arm.

Figure 1.

Skin mapping (A) and removal incision (B) of subfascial implant in patient with prior removal attempt by general surgeon at outside institution.

We reviewed the electronic medical records of all patients in our database during the study period to abstract demographic information, medical histories, implant specific data and clinical outcomes. Our primary goal was to assess successful in-office removal of the implant. We also evaluated the proportion of patients referred versus those seen in the clinic as well as evaluation of the impact of body mass index (BMI) and reinsertion of index implant through removal incision on subfascial location, and clinical outcomes including postprocedure complications. We arranged follow-up by phone or in the office for women that had postprocedure complaints until resolution or a diagnosis was made. We used Fisher’s exact tests for dichotomous variables and Student’s t test for continuous variables. We assessed normality of age, BMI and distance traveled by histograms and QQ plots; all data were normally distributed. All data were analyzed with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC, USA).

RESULTS

Of 61 referrals, 55 (90%) patients presented for their scheduled appointment; characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median distance traveled was 20.8 miles (range 1.5–179 miles). The number of referrals seen in clinic annually increased from five in 2015 to 26 in 2018. Primary reasons for referral included failed attempt at removal by the referring health care provider (n=29) for both palpable (n=6) and nonpalpable (n=23) implants, or concern for deeply placed, abnormally located or nonpalpable implant without a removal attempt (n=26). The number of patients experiencing at least one removal attempt prior to referral remained constant at about 50% over the four-year time period (2/5, 4/8, 10/16 and 13/26 in 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018, respectively).

Table 1.

Demographic and implant characteristics of patients evaluated for non-palpable or complex implant removal (N=55)

| Age (years) | 26.7 ± 5.8 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 21 (38%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.3 ± 9.1 |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 15 (27%) |

| Parity | |

| 0 | 25 (46%) |

| 1 | 13 (24%) |

| 2+ | 16 (29%) |

| Unknown/not recorded | 1 (2%) |

| Referral clinic | |

| Reproductive health clinic* | 24 (44%) |

| Private office | 26 (47%) |

| Academic/internal | 5 (9%) |

| Distance traveled (miles†) | |

| < 25 | 31 (56%) |

| 25 to 49 | 8 (15%) |

| 50 to 99 | 10 (18%) |

| ≥ 100 miles | 6 (11%) |

| Implant | |

| Nexplanon | 50 (91%) |

| Implanon | 5 (9%) |

| Left arm | 47 (86%) |

| Right arm | 8 (15%) |

| Time from placement (months) | 30.3 ± 19.4 |

| Prior contraceptive implant use | |

| Yes | 15 (27%) |

| No | 38 (69%) |

| Unknown | 2 (4%) |

| Current implant inserted through removal incision† | |

| Yes | 8 (53%) |

| No | 5 (33%) |

| Unknown | 2 (13%) |

| Imaging prior to referral | |

| None | 30 (55%) |

| One imaging study (US or XR only) | 17 (31%) |

| Multiple imaging modalities | 8 (15%) |

| Removal attempts prior to referral | |

| None | 26 (47%) |

| 1 | 20 (36%) |

| 2+ | 9 (16%) |

| Primary reason for removal | |

| Device expiration | 21 (38%) |

| Desires pregnancy | 8 (16%) |

| Bleeding complaints | 4 (7%) |

| Systemic side effects | 11 (20%) |

| Other‡ | 11 (18%) |

All data presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation

BMI = body mass index; US = ultrasound; XR = x-ray

Reproductive health clinic = Planned Parenthood or other community reproductive health clinic

Miles calculated from home zip code to clinic zip code using Google maps

Other includes pain/neuropathy, location/migration concerns, partially removed fragment, acute cellulitis, permanent contraception initiated

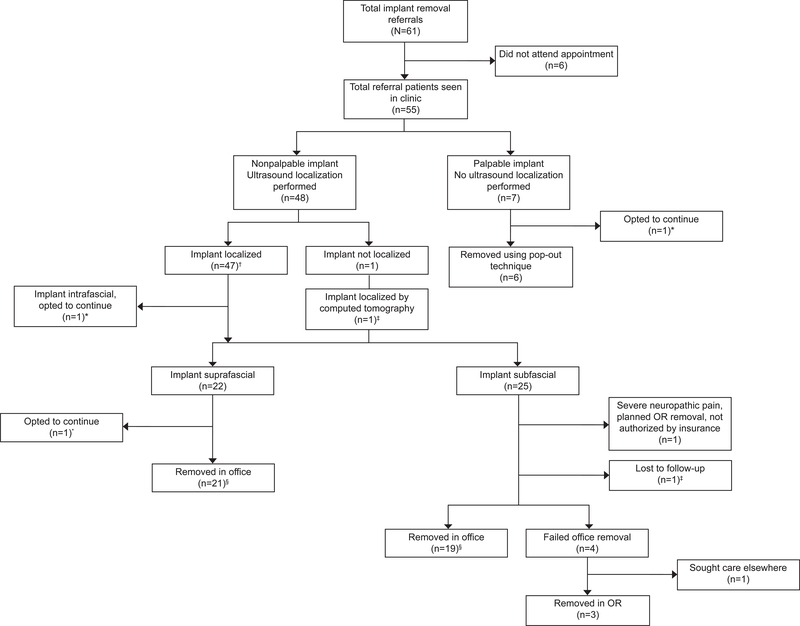

Figure 2 outlines the outcomes of our assessments and removal attempts. Overall, three patients with either a palpable, intrafascial or suprafascial implant opted to continue use after counseling, and two with subfascial implants did not have removal attempts by our team after initial evaluation. Of the 50 attempted office removals, 46 (92%) were successful including all six palpable implants and 40/44 (91%) implants that required ultrasound localization. Of the 44 nonpalpable implants, successful removal rates for suprafascial implants (21/21, [100%, 95% CI 83–100%]) did not differ compared to subfascial implants (19/23, [83%, 95% CI 67–98%]), p=0.11. Transient postprocedure neuropathic complaints were noted in 7/23 (30%, 95% CI 12–49%) of the subfascial implant removals and 1/21 (5%, 95% CI 0–13%) of the suprafascial implant removals (P=.048). Neuropathic complaints included mild tingling of fingers or numbness in ulnar distribution of arm. These complaints all spontaneously resolved within 6 months, with the majority (6/8, 75%) resolving within one month. Of the 49 patients with successful in-office or operating room removal, nine (18%) elected to have another implant placed.

Figure 2.

Referral flowsheet of our clinical assessments and outcomes. OR, operating room. *Three patients opted to continue use of implant; one palpable implant had one additional year of extended use; intrafascial implant continued use due to time constraints after evaluation and counseling, aware she must return to specialty center at time of desired removal; suprafascial implant referred with acute cellulitis immediately after insertion, at consultation, cellulitis was resolved and implant partially palpable (ultrasound localization confirmed implant location). †Two implants initially not localized by ultrasound, identified using X-ray, repeat ultrasound located implants with minimal shadowing. ‡Subfascial implant identified with X-ray then localized with computed tomography; patient ultimately lost to follow-up due to insurance authorization issues. §One subfascial and one suprafascial implant required removal in ultrasound suite for direct ultrasound guidance, while all others successfully removed with skin mapping technique in office.

Table 2 compares the impact of BMI as a predictor of subfascial location. Non-palpable implants were more likely to be subfascial in non-obese (24/34, 71%) as compared to obese (1/13, 8%) patients (P<.001). Fifteen patients referred to our specialty referral center had used a contraceptive implant in the past, eight of whom were known to have reinsertion of the index implant through the removal incision. One of these implants was palpable on our initial examination, while the other seven (88%) were nonpalpable and subfascial. Six (86%) of the seven nonpalpable subfascial implants were in patients with a BMI of less than 30 kg/m2.

Table 2.

Comparison of BMI, reinsertion and removal event and reasons for removal between suprafascial non-palpable and subfascial non-palpable implants

| Non-palpable suprafascial (n = 22) | Non-palpable subfascial (n = 25) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 34.0 ± 9.4 | 23.1 ± 3.8 | <.001* |

| Body Mass Index Categories | <.001* | ||

| Underweight to Normal (< 25 kg/m2) | 4 (18%) | 17 (68%) | |

| Overweight (25 kg/m2 to < 30 kg/m2) | 6 (27%) | 7 (28%) | |

| Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) | 12 (55%) | 1 (4%) |

All data presented as n (%) and mean ± standard deviation

Student t test used for means and Fisher’s exact test used for categorical comparisons

DISCUSSION

At our Family Planning specialty referral center, 92% of nonpalpable or complicated implants were successfully removed in the office. Importantly, we averted a large incision in the operating room in 83% of those with subfascial implants. However, nearly one-third of these patients reported transient postprocedure neuropathic complaints, albeit limited in duration; this information should be incorporated into pre-procedure counseling.

Our findings suggest that a nonpalpable implant in non-obese patients is highly likely to be subfascial. In these cases, health care providers without advanced removal training should probably avoid attempting removal and refer to a specialty center. Although our data also suggest a potential association between reinsertion through a removal incision and subfascial placement, the analysis is limited due to the small numbers. To test this hypothesis the appropriate comparison group would have to be a group of women who had a second implant placed through a separate incision. However, the link is plausible and until additional data are available, health care providers should maintain caution when performing a removal and reinsertion procedure.

More than 50% of our patients had prior removal attempts before referral with 16% having two or more failed attempts. We expected this proportion to decrease over time as the community grew more aware of our specialty center; however, the rates remained stable. Clearly, more targeted education for clinic staff, health care providers and patients is warranted. The FDA-mandated implant insertion and removal training would provide an excellent opportunity for education about early referral for nonpalpable or deep implants and we encourage that specific information about the U.S. specialty removal network be added to the program.

We use ultrasonography for primary implant localization which provides the ability to mark the position of the implant and identify nearby vascular structures. Transducers with a frequency of 5 or 7.5 MHz, which are commonly available in an Obstetrician-Gynecologist’s office, can be used to identify correctly placed implants.18Frequencies of 10 MHz or greater are more useful with nonpalpable implants, since these frequencies can identify an implant in both suprafascial and subfascial locations.19 We have found newer 15 and 18 MHz transducers, which are developed primarily for extremity visualization, are an important tool, especially for subfascial implants.

Our outcomes confirm the utility of high-frequency ultrasound localization of nonpalpable implants and demonstrate the importance of a specialty referral center for removal. Our experience with subfascial implant removal in the office is unique. We were obligated to develop this process due to scheduling limitations for implant removals under direct ultrasound guidance in the radiology suite. Because deep implant placement is rare, this report represents a relatively large series. Still, the numbers are too small to support any predictive multivariable analyses.

Our outcomes provide essential information for all clinicians who see patients using contraceptive implants to ensure appropriate counseling and decision-making when removal is desired and the implant is not easily palpable. Health care providers who cannot easily palpate the implant at the time of requested removal should consider early referral to a specialty center. When the location of such a center is unknown, pharmaceutical company representatives should be contacted for more information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Audrey Hirstein, Juliana R. Melo, MD, MSCS and Robert H. Allen, MD for their assistance with the center program.

Funding:

Supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grant number UL1 TR001860. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Financial Disclosures: Mitchell D. Creinin has received personal support for work on an Advisory Board for Lupin and Merck & Co. and he is a consultant for Danco, Estetra, Exeltis, and Medicines360. He receives research funding paid to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of California, Davis, and receives research funding for contraceptive research from Fidelity Charitable, HRA Pharma, Medicines360, Merck & Co., Sebela, NIH/NICHD, and the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. In addition to the above entities, he has received personal support for work as a speaker for Allergan, Merck & Co., Gedeon Richter, and Women’s Health Japan. He has received personal support for work on an Advisory Board for Allergan and consulting for Dare and Femasys. The Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of California, Davis, receives research funding for contraceptive research from Dare, HRA Pharma, Medicines360 and Sebela. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Diego D, Tappy E, Carugno J. Axillary migration of Nexplanon®: Case report. Contraception 2017;95(2):218–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallon A, Fontarensky M, Chauffour C, Boyer L, Chabrot P. Looking for a lost subdermal contraceptive implant? Think about the pulmonary artery. Contraception 2017;95(2)215–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi JH, Kim HY, Lee SS, Cho S. Migration of a contraceptive subdermal device into the lung. Obstet Gynecol 2017;60(3):314–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowlands S, Mansour D, Walling M. Intravascular migration of contraceptive implants: two more cases. Contraception 2017;95(2):211–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creinin MD, Kaunitz AM, Darney PD, Schwartz L, Hampton T, Gordon K, et al. The US etonogestrel implant mandatory clinical training and active monitoring programs: 6-year experience. Contraception 2017;95(2):205–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen MJ, Creinin MD. Removal of a nonpalpable etonogestrel implant with preprocedure ultrasonography and modified vasectomy clamp. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126(5):935–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, Minh TD. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception 2015;91:274–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenberg DL, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, Teal SB, Westoff CL, Creinin MD. Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception 2015;92:10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odom EB, Eisenberg DL, Fox IK. Difficult removal of subdermal contraceptive implants: a multidisciplinary approach involving a peripheral nerve expert. Contraception 2017;96:89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guiahi M, Tocce K, Teal S, Green T, Rochon P. Removal of a Nexplanon® implant located in the biceps muscle using a combination of ultrasound and fluoroscopy guidance. Contraception 2014;90:606–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurel K, Gideroglu K, Topcuoglu A, Gurel S, Saglam I, Yazar S. Detection and localization of a nonpalpable subdermal contraceptive implant using ultrasonography: A case report. J Med Ultrasound 2012;20:47–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mansour D, Walling M, Glenn D, Starter C, Graesslin O, Herbst J, et al. Removal of non-palpable etonogestrel implants. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2008;34(2):89–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park JU, Bae HS, Lee SM, Bae J, Park JW. Removal of a subdermal contraceptive implant (Implanon NXT) that migrated to the axilla by C-arm guidance: A case report and review of the literature. Medicine 2017;96(48):e8627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salsamendi JT, Morffi D, Gortes FJ. Removal of an intramuscular contraceptive implant. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2017;28:465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh M, Mansour D, Richardson D. Location and removal of non-palpable Implanon® implants with the aid of ultrasound guidance. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2006:32(3):153–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vollans SR, Grainger A, O’Connor P, Limb D. Hormone-releasing contraceptive implants: our experience of complex removals using preoperative ultrasound. Contraception 2015;92(1):81–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mansour D UK provision for removal of non-palpable contraceptive implants. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2009;35(1):3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lantz A, Nosher JL, Pasquale S, Siegel RL. Ultrasound characteristics of subdermally implanted Implanon contraceptive rods. Contraception 1997;56:323–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shulman LP, Gabriel H. Management and localization strategies for the nonpalpable Implanon rod. Contraception 2006;73:325–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.