Abstract

There is conflicting evidence regarding the association between metformin use and cancer risk in diabetic patients. During 2002–2012, we followed a cohort of 315,890 persons aged 21–87 years with incident diabetes who were insured by the largest health maintenance organization in Israel. We used a discrete form of weighted cumulative metformin exposure to evaluate the association of metformin with cancer incidence. This was implemented in a time-dependent covariate Cox model, adjusting for treatment with other glucose-lowering medications, as well as age, sex, ethnic background, socioeconomic status, smoking (for bladder and lung cancer), and parity (for breast cancer). We excluded from the analysis metformin exposure during the year before cancer diagnosis in order to minimize reverse causation of cancer on changes in medication use. Estimated hazard ratios associated with exposure to 1 defined daily dose of metformin over the previous 2–7 years were 0.98 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.82, 1.18) for all-sites cancer (excluding prostate and pancreas), 1.05 (95% CI: 0.67, 1.63) for colon cancer, 0.98 (95% CI: 0.49, 1.97) for bladder cancer, 1.02 (95% CI: 0.59, 1.78) for lung cancer, and 0.88 (95% CI: 0.56, 1.39) for female breast cancer. Our results do not support an association between metformin treatment and the incidence of major cancers (excluding prostate and pancreas).

Keywords: bladder cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, diabetes mellitus, lung cancer, metformin, time-varying treatment, weighted cumulative exposure

The evaluation of associations between glucose-lowering medications (GLMs) and cancer risk has increased dramatically. Metformin is the predominant drug being investigated in this context. This biguanide has a well-established safety profile and has been used as a treatment for hyperglycemia for more than half a century (1). Metformin is the most commonly prescribed oral GLM worldwide and is recommended as first-line therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus (2). Several studies, starting in 2005, have suggested a possible protective effect of metformin on cancer risk (3). Wu et al. (4) concluded that there was such an effect in a meta-analysis of 265 studies on GLMs and cancer incidence, 66 of them on metformin; however, heterogeneity between them was high (I2 = 89%), and the association was not supported by a sub–meta-analysis that comprised the 23 randomized controlled trials from the full meta-analysis. Time-related biases and insufficient attention to the natural history of type 2 diabetes have been claimed to be the basis of the negative metformin association demonstrated in observational studies (5). Accordingly, in a systematic review of observational studies, Farmer et al. (6) showed that among studies with a low possibility of bias, a causal effect of metformin on risk of all-sites or specific types of cancer was not evident.

We investigated the association between metformin treatment as a time-dependent exposure and cancer incidence in a population-based cohort study of patients with incident type 2 diabetes, while accounting for major time-related biases and for various diabetes treatments as they changed over time. An important feature of our investigation was the use of Cox regression that included history of metformin treatment and history of other GLMs as time-dependent covariates. Sylvestre and Abrahamowicz (7) described the use of weighted cumulative exposure (WCE) functions for evaluating the effects of history of use of a medication on the incidence of a disease in continuous time. In this paper, we describe a simplified, discrete-time version of the WCE.

METHODS

Study population

Our study was based on electronic records from the largest health maintenance organization in Israel, Clalit Health Services, which insures 53% (4.3 million) of the nation’s population. All persons aged 21–87 years on January 1, 2002, who were free of diabetes and cancer at study entry were included in a closed cohort, which was followed until December 31, 2012, for incident diabetes. In the present analysis, only patients who developed diabetes during follow-up were included, and they were subsequently followed for incident cancer. The cohort data file, comprising abundant high-quality demographic, clinical, and pharmaceutical information, was linked to the Israel National Cancer Registry for ascertainment of cancer morbidity.

Incident diabetes was defined as fulfillment of at least one of the following 6 criteria during the period from January 1, 2002, to December 31, 2012: 1) a record of diabetes in the Clalit Chronic Disease Registry; 2) a physician’s diagnosis of diabetes in conjunction with a plasma glucose test result of ≥126 mg/dL within 12 months; 3) a hemoglobin A1c level of 6.5% or higher; 4) a 2-hour plasma glucose concentration of ≥200 mg/dL (during an oral glucose tolerance test); 5) 2 plasma glucose measurements of ≥126 mg/dL within 12 months; and 6) 3 or more purchases of glucose-lowering medication within 12 months.

Cancer incidence was ascertained by record linkage to the Israel National Cancer Registry, established in 1960. The registry has benefited since 1982 from a national law mandating registration of cancer. It has 97% coverage of solid tumors and approximately 88% coverage of hematological cancers (8). In this paper, we report associations, among patients with incident diabetes, between metformin treatment and cancer at all sites except the pancreas and prostate (“all-sites cancer”; see reasons for exclusion below), as well as colorectal, bladder, lung, and breast cancer (the cancers with the highest incidence in Israel).

We excluded pancreatic and prostate cancers from the present analysis because in previous analyses of our cohort of persons with diabetes, we found strong associations between glucose levels and these cancers (9), whereas we found no such associations with other cancers. In view of these associations, any assessment of the effect of GLMs on cancers of the pancreas and prostate requires more complex modeling that includes history of glucose levels as well as medication history (6). Therefore, the associations between metformin and these cancers are being analyzed separately.

Metformin exposure was defined as metformin use alone or in combination with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. The latter combination entered the market in the last quarter of 2009, comprising 1% of all metformin purchases, and gradually increased to 6% in subsequent years, but the predominant form of metformin use in this study was use of metformin exclusively. We adjusted for all other GLMs, including treatment with insulin, α-glucosidase inhibitors, rosiglitazone, sulfonylureas, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, and meglitinides. The doses considered for metformin and these other GLMs were those in the purchasing data. We recognize that some persons may not have consumed all of the medication that they purchased. However, in the absence of information on the amounts of missed medications, our analysis was based on the assumption that the amount purchased was the amount consumed.

Numbers of GLM doses were summarized according to the defined daily dose (DDD). The DDD is the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication in adults. The DDD is a unit of measurement and does not necessarily reflect the recommended or prescribed daily dose. Therapeutic doses for individual patients and patient groups often differ from the DDD, since they are based on individual characteristics (such as age, weight, ethnicity, and type and severity of disease) and pharmacokinetic considerations. DDDs provide a fixed unit of measurement independent of price, currency, package size, and strength, enabling the researcher to assess trends in drug consumption and to perform comparisons between population groups.

The review boards of Sheba Medical Center and Clalit Health Services approved the study proposal and exempted the study investigators from obtaining informed consent from each patient because of the historical nature of the data and the source of the data (electronic records on a large population).

Statistical analysis

We evaluated the association of metformin with the risks of all-sites (except prostate and pancreas) cancer and selected site-specific cancers among incident diabetes patients using Cox regression models with time-dependent covariates. The time origin for the Cox model was 2 years after the date of diabetes diagnosis. Thus, incident diabetes patients who died, developed cancer, or completed their follow-up within 2 years of diabetes diagnosis were excluded from the analysis. In addition, patients were censored from the study upon reaching age 90 years. The time axis was divided into quarterly (3-month) periods, and during each period the mean DDD metformin level was calculated for each individual.

A major challenge in this work was to find a flexible way of relating medication history to the risk of cancer. If t denotes the current quarter (t is labeled from 1, the quarter that starts from the date of diabetes diagnosis, to a possible maximum of 44), then a person’s risk of cancer in quarter t may be affected by the dose of medication taken in quarters t − 1, t − 2, t − 3, etc., going back to quarter 1. (Note that using this notation, follow-up for cancer starts at t = 9, the first quarter that is 2 years after diabetes diagnosis.) Let D(t) be the mean daily dose of the medication in quarter t. We express the overall medication history exposure as a weighted sum of the past doses,

| (1) |

going back to the first quarter after diagnosis. This sum is called the WCE at time t, denoted WCE(t). Sylvestre and Abrahamowicz (7) defined this term as an integral over continuous time, but equation 1 is a sum over the previous quarters. Because the “lag time” of the effect of the medication on cancer risk in quarter t is unknown, the relative weights for past doses are similarly unknown. In our analysis we can estimate the weights as part of the Cox model analysis, viewing each weight as a regression coefficient. However, this would require estimating 36 different weights, corresponding to the 44 quarters. In our application, we have simplified the estimation procedure by assuming that certain groups of weights are equal, namely for the quarters of the previous year (u = 1–4), for years 2–4 previously (u = 5–16), for years 5–7 previously (u = 17–28), and for years 7–10 previously (u = 29–40). In this way, equation 1 simplifies to

with only 4 unknown weights instead of 36. In the above expression, if t − u is less than 1, then D(t − u) is set to 0. We did not extend WCE back beyond 10 years, since the data were too sparse to adequately estimate the weights for these years.

We incorporated the WCE into the Cox risk model as follows:

where is the individual’s hazard rate at time t for the cancer of interest, is the baseline hazard rate, is the coefficient of WCE(t), C are the baseline confounders, and are their coefficients. With our simplifying assumption, the model reduces to the following Cox model:

| (2) |

where D1(t), D2(t), D3(t), and D4(t) are the mean daily doses over the year previous to quarter t, years 2–4 previous to t, years 5–7 previous to t, and years 7–10 previous to t, respectively (see the Web Appendix, available at https://academic.oup.com/aje, for details). The doses referred to are those of metformin. The model shown in equation 2 may be expanded to include additive terms for other medications, each medication comprising 4 additive terms, as for metformin. In our main analyses, we also included the following GLMs, grouped into 4 main categories according to their mechanism of action: insulin (fast-acting, long-acting, intermediate-acting, and a combination of fast- and intermediate-acting); drugs affecting endogenic insulin levels, that is, insulin secretagogues (sulfonylureas, meglitinides) and incretin mimetics (dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists); α-glucosidase inhibitor; and roziglitazone (Avandia; GlaxoSmithKline (Israel) Ltd., Petach Tikva, Israel), the thiazolidinedione used in Israel during the study period.

The confounding variables, C, included in our model were: age in 5-year groups (according to age at entry, i.e., 2 years after diabetes diagnosis), sex (except for breast cancer), socioeconomic status (determined according to locality of the health maintenance organization clinic: low, medium, high, or missing (2.7% of participants had a missing value)), and race/ethnicity (country of birth or mother’s country of birth: Ashkenazi Jew (persons born in Russia, Eastern Europe, Europe, America, or South Africa); Sephardic Jew (persons born in northern Africa or the Middle East); Yemenite, Ethiopian, or central African Jew; Israeli Jew (also including Israel-born Jews whose mother’s birthplace was unknown); or Israeli Arab). In breast cancer analyses, adjustment was also made for parity, and in lung and bladder cancer analyses, adjustment was made for smoking status (ever smoking vs. never smoking/unknown).

As mentioned above, we allowed a gap of 2 years between diabetes diagnosis and the start of follow-up for incident cancer. This was done to minimize effects of ascertainment bias and reverse causation of cancer diagnosis on diabetes diagnosis. Similarly, when evaluating the association of metformin with cancer risk, we ignored the coefficient β1, representing the association for metformin use in the previous year, since the cancer may have led to a change in metformin dose immediately prior to diagnosis.

Accordingly, we report 2 estimated hazard ratios for cancer associated with metformin use: firstly, the ratio of the hazard rate of someone who used a mean dose of x + 1 DDDs in years 2–4 previous to the current quarter to the hazard rate of someone who was similar in terms of all other characteristics but used a mean dose of x DDDs during that period; and secondly, the ratio of the hazard rate of someone who used a mean dose of x + 1 DDDs in years 2–7 previous to the current quarter to the hazard rate of someone who was similar in all other characteristics but used a mean dose of x DDDs during that period. These hazard ratios are estimated by exp(b2) and exp(b2 + b3), respectively, where b2 and b3 are the estimates of the coefficients β2 and β3 in the extended model (2). A simpler interpretation of these hazard ratios is given by considering the case of x = 0 in the above definitions. In this case, the hazard ratios relate to using a mean metformin dose of 1 DDD over the period in question versus no use of metformin over that period. We aimed to also present hazard ratios for metformin use over the period 2–10 years previously, but the data for years 7–10 were insufficient to estimate those hazard ratios with reasonable accuracy.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the persons included in the cohort are presented in Table 1. Close to 1.33 million person-years of follow-up accrued during 2004–2012 among the 315,890 adults under the age of 88 years who developed diabetes. Of these, 304,582 were without a previous diagnosis of cancer.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 315,890 Israelis Aged 21–87 Years With Incident Diabetes Who Were Followed for Cancer Incidence (1,934,333 Person-Years) Between 2002 and 2012

| Characteristic | % |

|---|---|

| Age at baselinea, yearsb | 58.6 (14.9) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 47.0 |

| Female | 53.0 |

| Ethnic origin | |

| Ashkenazi Jew | 31.3 |

| Sephardic Jew | 27.2 |

| Yemenite, Ethiopian, or central African Jew | 5.3 |

| Israeli Jew | 18.0 |

| Israeli Arab | 18.1 |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| Low | 43.7 |

| Medium | 37.5 |

| High | 16.1 |

| Missing data | 2.7 |

| Smoking status | |

| Never smoked/missing data | 64.3 |

| Past or current smoker | 35.7 |

| No. of children | |

| 0 | 22.1 |

| 1 | 16.4 |

| 2 or 3 | 35.8 |

| ≥4 | 25.7 |

a At time of diabetes diagnosis.

b Values are expressed as mean (standard deviation).

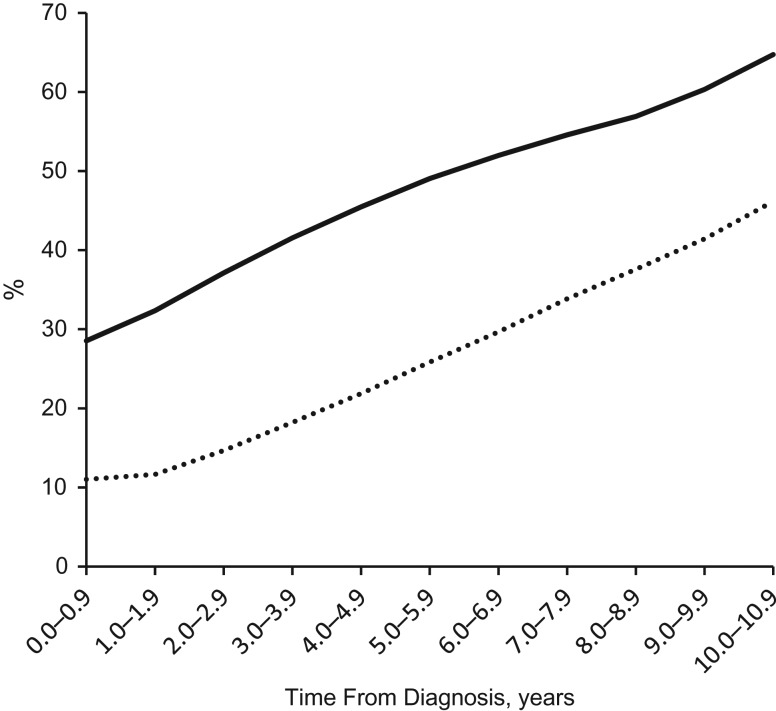

Table 2 presents the number of patients remaining at risk for cancer each year from the time of diabetes diagnosis and their use of metformin and other GLMs. Overall, 172,948 (54.7%) of the patients took metformin at some time during their follow-up. Of those remaining in follow-up, the percentage taking metformin rose steadily, from 29% in the first year following diagnosis of diabetes to 65% in the 11th year (see Figure 1). A total of 94,630 patients (30%) took other GLMs at some time during follow-up. Of those remaining in follow-up, the percentage taking other GLMs rose steadily, from 11% in the first year following diabetes diagnosis to 46% in the 11th year (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Number of Israelis With Diabetes Mellitus Who Were at Risk for Cancer, According to Time From Diabetes Diagnosis (Years) and Use of Metformin and Other Glucose-Lowering Medications, 2002–2012a

| Time From Diabetes Diagnosis, years | No. Alive Without Any Cancer at the Beginning of the Periodb | No. Who Began Metformin Treatmentc | No. Who Continued Metformin Treatmentd | DDDe of Metforminf | No. Who Began Other GLM Treatmentg | No. Who Continued Other GLM Treatmenth | No. Not Treated With Any GLM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0–0.9 | 304,582 | 86,913 | 0 | 0.27 | 33,551 | 0 | 203,493 |

| 1.0–1.9 | 298,984 | 26,363 | 70,357 | 0.36 | 12,590 | 22,217 | 171,699 |

| 2.0–2.9 | 276,902 | 19,211 | 83,588 | 0.40 | 11,461 | 29,131 | 139,794 |

| 3.0–3.9 | 242,254 | 13,810 | 86,850 | 0.45 | 10,084 | 34,052 | 108,380 |

| 4.0–4.9 | 208,035 | 9,748 | 84,844 | 0.49 | 8,240 | 37,239 | 83,093 |

| 5.0–5.9 | 171,243 | 6,753 | 77,260 | 0.52 | 6,548 | 37,698 | 60,898 |

| 6.0–6.9 | 138,695 | 4,546 | 67,553 | 0.56 | 4,947 | 36,195 | 44,538 |

| 7.0–7.9 | 107,186 | 2,932 | 55,571 | 0.59 | 3,625 | 32,658 | 31,161 |

| 8.0–8.9 | 77,333 | 1,650 | 42,362 | 0.62 | 2,163 | 26,090 | 20,176 |

| 9.0–9.9 | 48,788 | 836 | 28,599 | 0.65 | 1,148 | 19,065 | 10,709 |

| 10.0–10.9 | 13,487 | 186 | 8,544 | 0.68 | 273 | 5,953 | 2,263 |

Abbreviations: DDD, defined daily dose; GLM, glucose-lowering medication.

a Other GLMs included insulin, α-glucosidase inhibitors, rosiglitazone, sulfonylureas, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, and meglitinides.

b Numbers in the succeeding columns may not sum to those in this total column because some patients took both metformin and other GLMs.

c If a patient had not taken metformin before this period and started to take metformin during this period, s/he was entered in this cell.

d If a patient took metformin before this period and also during this period, s/he was entered in this cell.

e The DDD is the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication in adults.

f The sum of the total DDDs of metformin over these patients divided by 365.25 and then by the total number of patients in the 2 preceding columns. The DDD is a unit of measurement and does not necessarily reflect the recommended or prescribed daily dose.

g If a patient started use of any GLM other than metformin and had not taken any such medication before, s/he was entered in this cell.

h If a patient took any GLM other than metformin before this period and also took any GLM other than metformin during this period, s/he was entered in this cell.

Figure 1.

Percentages of diabetic Israelis at risk of cancer who were using metformin (solid curve) and other glucose-lowering medications (dotted curve), by years since diabetes diagnosis, 2002–2012. For calculation of trajectories, see Table 2 (third plus fourth columns divided by second column for metformin trajectory; sixth plus seventh columns divided by second column for other glucose-lowering medication trajectory).

Results of the Cox regression analysis for each cancer site are presented in Web Tables 1–5, and the results for metformin exposure are shown in Table 3. The number of persons included in each analysis differed, because we excluded only those patients who had developed the specific cancer of interest within 2 years of their diabetes diagnosis. The main confounders were found to be age, ethnic group, and, for lung and bladder cancers, smoking. Overall, the use of nonmetformin GLMs was not found to be associated with the cancers investigated. From the regression coefficients for metformin shown in Web Tables 1–5, hazard ratios for 1 DDD of metformin taken over the periods 2–4 years previously and 2–7 years previously (Table 3) were calculated as described in the Methods section. The 95% confidence intervals for these hazard ratios included the null value of 1 (Table 3), indicating that there was no clear evidence of an association between the use of metformin and the incidence of these cancers.

Table 3.

Association of Metformin Treatment (1 Defined-Daily-Dose Increment) With Incidence of All-Sites Cancer and Specific Cancers Among Israelis With Diabetes, Controlling for Use of All Other Glucose-Lowering Medicationsa and Adjusting for Confounding Variablesb, 2004–2012

| Cancer Site | No. at Riskc | No. of Cancer Events | Period of Metformin Treatment Previous to the Current Quarterd | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years 2–4 | Years 2–7 | |||||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |||

| All sitese | 294,770 | 11,898 | 0.96 | 0.82, 1.12 | 0.98 | 0.82, 1.18 |

| Colon | 310,698 | 2,131 | 1.13 | 0.79, 1.63 | 1.05 | 0.67, 1.63 |

| Bladder | 313,133 | 764 | 0.91 | 0.50, 1.68 | 0.98 | 0.49, 1.97 |

| Lung | 313,460 | 1,265 | 0.85 | 0.53, 1.38 | 1.02 | 0.59, 1.78 |

| Breast (women only) | 163,461 | 1,835 | 0.95 | 0.64, 1.40 | 0.88 | 0.56, 1.39 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

a Adjusted for use of insulin, α-glucosidase inhibitor, rosiglitazone, sulfonylureas, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, and meglitinides.

b Confounding variables included age, sex, socioeconomic status, ethnic origin, smoking (for bladder and lung cancers), and parity (for breast cancer).

c Numbers reflect numbers of patients at risk for the particular cancer at the time they were diagnosed with diabetes (and were without any previous cancer diagnosis), excluding those who completed follow-up within 2 years of their diabetes diagnosis.

d The first year prior to the current period was excluded, because an undiagnosed cancer could cause perturbations in glucose levels, particularly in the year prior to diagnosis.

e Without prostate and pancreatic cancers.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found no clear association between the use of metformin and all-sites cancer (excluding prostate and pancreas), nor did we find an association with cancers of the colon, breast, lung, and bladder.

Several laboratory studies have suggested that metformin may reduce the incidence of cancer. Pleiotropic anticancer effects of metformin have been demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo, on a number of main molecular pathways, and in cellular and metabolic processes (10). Metformin has been shown to specifically target cancer stem cells, as well as to augment the benefit of anticancer drugs (11). In a rat model of postmenopausal breast cancer, metformin was shown to inhibit the formation of new tumors, as well as to decrease the size of mammary tumors (12). However, to date, the published results from ongoing clinical trials that have addressed the hypothesis that metformin has antineoplastic activity have related only to surrogate markers or have been negative (13, 14).

The findings of several observational studies have suggested a protective effect of metformin on cancer development and progression. Metformin has been reported to be associated with significant reductions in the risk of cancer overall (15–17), as well as cancers of the breast (18), liver (19), colorectum (18–20), pancreas (19), stomach (19), prostate (21), and esophagus (19). Other studies did not find reduced risks for at least some of the cancer types investigated (19, 22, 23). However, it has been claimed that the negative metformin association reported in many observational studies resulted from time-related biases, occurring when allotting time at risk to different exposure categories or when overlooking the effect of the natural history of type 2 diabetes (5, 24). These biases have been described as 1) time-window bias, a bias introduced because of differential exposure opportunity time windows between subjects; 2) immortal time bias, a bias introduced with time-fixed cohort analyses that misclassify unexposed time as exposed; and 3) time-lag bias, a bias introduced by comparing treatments given at different stages of the disease (i.e., when a longer duration of diabetes in the comparator group confounds the association). Time-related biases have been shown to exaggerate the association of a drug with disease downward, thus making a drug appear protective when it really has no effect (5).

Like the study described in this paper, a number of more recently published studies that accounted for time-related biases did not find negative associations of metformin use with the incidence of lung, colorectal, breast, or bladder cancers (25–28). On the other hand, the use of metformin during a period of at least 5 years was found to be associated with reduced incidence of colorectal cancer in men (29).

The strengths of the current study are the use of a large population-based database that has high-quality data on medication purchases, linkage to data from a national cancer registry with 95% coverage of cancer diagnoses, the use of time-dependent Cox models that overcome the problem of time-related biases, and the use of a flexible WCE approach that enables examination of different time periods and doses of exposure, particularly the exclusion of exposure periods shortly before cancer diagnosis. Using the WCE concept in continuous time requires special programming. Our adaptation of the method to discrete time periods (i.e., quarters) enabled implementation of the WCE approach naturally, within the usual Cox regression framework, with a considerable reduction in programming burden. Additionally, the adjustment for use of other GLMs as time-dependent variables enabled us to capture more fully the complexity of diabetes treatment and to account for these potentially confounding exposures.

The characteristics of the study cohort reflect those of persons with diabetes in the Israeli population, assuring high external validity (30).

Limitations of the study include reliance on medication purchase data as a surrogate for medication use, a relatively short study duration, and limited data on confounding risk factors for cancer. The relatively short duration of the study, apart from limiting our ability to examine the association between longer-term metformin use and cancer, also reduced the statistical power to detect shorter-term associations. Thus, while the estimated hazard ratios are generally small and near the null value of 1, the confidence intervals are relatively wide.

Information on a number of potentially important confounders was not available in our database. We were not able to include body mass index, physical activity, or use of aspirin or statin medication as adjusting covariates in our models. The cancer most likely to be affected by this lack of adjustment is colorectal cancer. Confounding by body mass index and physical activity would tend to cause overestimation of the hazard ratio for metformin use for this cancer. On the other hand, if persons with more metformin use also took more aspirin or statins, this would cause an underestimate. It is therefore possible that these potential biases would partially cancel each other out.

Data with which to distinguish between the types of diabetes were not available; thus, persons with type 1 diabetes were included in the diabetes groups. However, the proportion of such cases is expected to have been small, and therefore their inclusion is not expected to have had a considerable impact on the results. Only 3.5% of adults with diabetes in Western countries are estimated to have type 1 diabetes. In addition, patients with type 1 diabetes are usually treated with insulin, and since we adjusted for insulin medication in our model, we also partially controlled for the inclusion of these patients.

We expect the database to become even more valuable as follow-up is extended and the quality of data on risk factors is improved.

In conclusion, our analysis, accounting for major time-related biases and for variations in diabetes treatment over time, did not support an association between metformin treatment and the incidence of cancers (excluding prostate and pancreas) in diabetic patients. Long-term controlled trials following diabetic patients from the time of diabetes diagnosis and randomizing them to use of metformin or other GLMs, with rerandomization to an added GLM in the case of failure to control plasma glucose level, would be the most reliable method of answering this question; but such studies are probably not feasible.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Unit for Cardiovascular Epidemiology, Gertner Institute for Epidemiology and Health Policy Research, Sheba Medical Center, Ramat Gan, Israel (Rachel Dankner, Nirit Agay); Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, School of Public Health, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel (Rachel Dankner, Laurence S. Freedman); Center for Patient-Oriented Research, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, New York (Rachel Dankner); Unit of Biostatistics and Biomathematics, Gertner Institute for Epidemiology and Health Policy Research, Sheba Medical Center, Ramat Gan, Israel (Liraz Olmer, Havi Murad, Laurence S. Freedman); Israel Center for Disease Control, Israel Ministry of Health, Ramat Gan, Israel (Lital Keinan Boker); School of Public Health, Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences, Haifa University, Haifa, Israel (Lital Keinan Boker); Clalit Health Services, Clalit Research Institute, Tel Aviv, Israel (Ran D. Balicer); and Public Health Department, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Be’er Sheva, Israel (Ran D. Balicer).

This work was partially funded by a Diabetes and Cancer grant from the European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes.

We thank Drs. Moshe Hoshen and Alla Berlin for their contributions to this study.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Abbreviations

- DDD

defined daily dose

- GLM

glucose-lowering medication

- WCE

weighted cumulative exposure

REFERENCES

- 1. Romero R, Erez O, Hüttemann M, et al. . Metformin, the aspirin of the 21st century: its role in gestational diabetes mellitus, prevention of preeclampsia and cancer, and the promotion of longevity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(3):282–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Diabetes Association 8. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(suppl 1):S73–S85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Evans JM, Donnelly LA, Emslie-Smith AM, et al. . Metformin and reduced risk of cancer in diabetic patients. BMJ. 2005;330(7503):1304–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu L, Zhu J, Prokop LJ, et al. . Pharmacologic therapy of diabetes and overall cancer risk and mortality: a meta-analysis of 265 studies. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Suissa S, Azoulay L. Metformin and the risk of cancer: time-related biases in observational studies. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2665–2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Farmer RE, Ford D, Forbes HJ, et al. . Metformin and cancer in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and comprehensive bias evaluation. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(2):728–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sylvestre MP, Abrahamowicz M. Flexible modeling of the cumulative effects of time-dependent exposures on the hazard. Stat Med. 2009;28(27):3437–3453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fishler Y, Keinan-Boker L, Ifrah A, eds. The Israel National Cancer Registry—Completeness and Timeliness of the Data [in Hebrew]. (Publication no. 365). Ramat Gan, Israel: Israel Center for Disease Control, Israel Ministry of Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dankner R, Boker LK, Boffetta P, et al. . A historical cohort study on glycemic-control and cancer-risk among patients with diabetes. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;57:104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schulten H-J. Pleiotropic effects of metformin on cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(10):2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hirsch HA, Iliopoulos D, Tsichlis PN, et al. . Metformin selectively targets cancer stem cells, and acts together with chemotherapy to block tumor growth and prolong remission. Cancer Res. 2009;69(19):7507–7511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giles ED, Jindal S, Wellberg EA, et al. . Metformin inhibits stromal aromatase expression and tumor progression in a rodent model of postmenopausal breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2018; 20:Article 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kordes S, Pollak MN, Zwinderman AH, et al. . Metformin in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):839–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goodwin PJ, Parulekar WR, Gelmon KA, et al. . Effect of metformin vs placebo on and metabolic factors in NCIC CTG MA.32. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(3):djv006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thakkar B, Aronis KN, Vamvini MT, et al. . Metformin and sulfonylureas in relation to cancer risk in type II diabetes patients: a meta-analysis using primary data of published studies. Metabolism. 2013;62(7):922–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lin HC, Kachingwe BH, Lin HL, et al. . Effects of metformin dose on cancer risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 6-year follow-up study. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(1):36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gandini S, Puntoni M, Heckman-Stoddard BM, et al. . Metformin and cancer risk and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis taking into account biases and confounders. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2014;7(9):867–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang P, Li H, Tan X, et al. . Association of metformin use with cancer incidence and mortality: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37(3):207–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Franciosi M, Lucisano G, Lapice E, et al. . Metformin therapy and risk of cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes: systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Singh S, Singh H, Singh PP, et al. . Antidiabetic medications and the risk of colorectal cancer in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(12):2258–2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Margel D, Urbach DR, Lipscombe LL, et al. . Metformin use and all-cause and prostate cancer-specific mortality among men with diabetes. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(25):3069–3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Becker C, Meier CR, Jick SS, et al. . Case-control analysis on metformin and cancer of the esophagus. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(10):1763–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Becker C, Jick SS, Meier CR, et al. . Metformin and the risk of endometrial cancer: a case-control analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129(3):565–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Klil-Drori AJ, Azoulay L, Pollak MN. Cancer, obesity, diabetes, and antidiabetic drugs: is the fog clearing? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(2):85–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kowall B, Rathmann W, Kostev K. Are sulfonylurea and insulin therapies associated with a larger risk of cancer than metformin therapy? A retrospective database analysis. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(1):59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kowall B, Stang A, Rathmann W, et al. . No reduced risk of overall, colorectal, lung, breast, and prostate cancer with metformin therapy in diabetic patients: database analyses from Germany and the UK. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(8):865–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mamtani R, Pfanzelter N, Haynes K, et al. . Incidence of bladder cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin or sulfonylureas. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(7):1910–1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hong JL, Jonsson Funk M, Buse JB, et al. . Comparative effect of initiating metformin versus sulfonylureas on breast cancer risk in older women. Epidemiology. 2017;28(3):446–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bradley MC, Ferrara A, Achacoso N, et al. . A cohort study of metformin and colorectal cancer risk among patients with diabetes mellitus. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(5):525–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zucker I, ed. National Diabetes Registry Report, 2012–2013 [in Hebrew]. Ramat Gan, Israel: Israel Center for Disease Control, Israel Ministry of Health; 2016. https://www.health.gov.il/PublicationsFiles/diabetes_registry_report_2012-2013.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.