Abstract

Notch proteins drive oncogenesis of many cancers, most prominently T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL). Because geranylgeranylated Rab proteins regulate Notch processing, we hypothesized that inhibition of geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (GGDPS) would impair Notch processing and reduce viability of T-ALL cells that express Notch. Here, we show that GGDPS inhibition reduces Notch1 expression and impairs the proliferation of T-ALL cells. GGDPS inhibition also reduces Rab7 membrane association and depletes Notch1 mRNA. GGDPS inhibition increases phosphorylation of histone H2A.X, and inhibitors of ataxia telangiectasia-mutated kinase (ATM) mitigate GGDPS inhibitor-induced apoptosis. GGDPS inhibition also influences c-abl activity downstream of caspases, and inhibitors of these enzymes prevent GGDPS inhibitor-induced apoptosis. Surprisingly, induction of apoptosis by GGDPS inhibition is reduced by co-treatment with γ-secretase inhibitors. While inhibitors of γ-secretase deplete one specific form of the Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD), they also increase Notch1 mRNA expression and increase alternate forms of Notch1 protein expression in cells treated with a GGDPS inhibitor. Furthermore, inhibitors of γ-secretase and ATM increase Notch1 mRNA stability independent of GGDPS inhibition. These results provide a model by which T-ALL cells use Notch1 to avoid DNA-damage-induced apoptosis, and can be overcome by inhibition of GGDPS through effects on Notch1 expression and its subsequent response.

Subject terms: Lipids, Leukaemia, Apoptosis, Target validation

Introduction

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) is a rare but aggressive T-cell malignancy. T-ALL comprises ~15% of childhood and 25% of adult ALL cases1. While the 5-year survival rate in children (80%) has improved significantly due to advances in chemotherapy, survival in primary resistant and relapsed cases is still low2, and many current therapies often cause toxicity in healthy cells.

One common mutation in T-ALL is NOTCH1, which is altered in over 60% of T-ALL cases3. Notch is also mutated in other types of cancer, such as breast, colon, lung, and prostate cancer4. However, its role in cancer is context dependent as Notch is oncogenic in some models but functions as a tumor suppressor in others5. Notch signaling is evolutionarily conserved and is required at multiple points in the developmental process, particularly in T-cell development6,7. Notch is first processed in the Golgi by furin convertases4. It is then transported to the plasma membrane where it encounters its ligand (delta/serrate/LAG-2)8. Ligand binding promotes two cleavage events, one by Adam10 and the other by γ-secretase9. It has been proposed that Notch activation cannot occur without γ-secretase processing. Hydrolysis by γ-secretase processing releases the active form of Notch, the Notch internal domain (NICD), which can translocate to the nucleus, bind to transcription factors, and promote proliferation and differentiation10.

Recent findings suggest a role for small GTPases in Notch1 processing. Court et al. showed a requirement of Rab7 and Rab8 in Notch1 signaling11, while Doi et al. found that Rap1 is essential in maturation of Adam1012. At the same time, we identified selective inhibitors of the enzyme geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (GGPS1, or GGDPS), which can be used to disrupt the function of geranylgeranylated small GTPases13–19. GGDPS is an enzyme in the isoprenoid biosynthesis pathway that produces geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) whose lipid moiety is post-translationally attached to small GTPases such as Rab and Rap to promote membrane association20,21. Thus, we hypothesized that disrupting small GTPase lipidation with a GGDPS inhibitor would affect Notch1 signaling and display beneficial growth inhibition in T-ALL.

Because drugs such as statins and nitrogenous bisphosphonates deplete GGPP and are implicated as cancer therapeutics, it is important to understand the signaling pathways affected by GGPP depletion. Throughout these studies, we use an inhibitor of GGDPS, digeranyl bisphosphonate (DGBP), to directly deplete levels of GGPP. DGBP has a GGDPS IC50 of 200 nM and is well characterized, making it useful to determine how GGPP depletion leads to apoptosis13,14. Better understanding of the mechanisms linking GGDPS inhibition to proliferation will be useful as further developments are made regarding the preclinical development of GGDPS inhibitors22–24 and geranylgeranyl transferase I25,26 and II27,28 inhibitors. Here, we describe the mechanism by which GGPP depletion alters Notch1 expression and function and induces apoptosis.

Materials and methods

Supplies and materials

The cell lines Jurkat, Daudi, and HL-60 were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). Molt-4 cells were obtained from ATCC. K562 cells were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO). RPMI-8226 cells were obtained from Coriell Institute (Camden, NJ). U2OS cells were obtained from ATCC. Cells were cultured in media containing RPMI-1640, 10% FBS, and Pen/Strep. Loucy cells were obtained from ATCC and cultured in T-cell media (RPMI-1640, 10% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin, nonessential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, 0.0004% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5). Cells were grown for at least 2 weeks after thawing before experimental use, and replaced with a fresh early-passage stock after no more than 3 months. GGPP, DAPT, and coelenterazine were obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Z-VAD-FMK was obtained from ApexBio (Houston, TX, USA). Imatinib, nilotinib, and Ku55933 were obtained from LC laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA). FITC-conjugated annexin V was obtained from Biolegend, and propidium iodide was obtained from Fisher.

Retinoblastoma protein (C-2) and c-myc (C-33) antibodies came from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Cleaved caspase 9 (Asp330) (D2D4), p-H2A.X (S139) (20E3), ATM (D2E2), cleaved Notch1 (V1744) (D3B8) (corresponding to human V1754), and Rab7 (D95F2) antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA). β-actin (Poly 6221) and c-abl (8E9) antibodies were obtained from Biolegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Vinculin (hVIN-1) was purchased from Sigma. The antibody for the Notch1 internal domain (bTAN20) was purchased from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (deposited by Artavanis-Tsakonas29). The antibody for actin (JLA20) was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (deposited by Lin J.J.30).

pCIneoRL-Notch1 3′UTR was purchased from Addgene (plasmid # 84595) (deposited by Yanan Yang31).

Apoptosis analysis

Cells were seeded at 100,000 cells/mL and incubated for 72 h. Cells were transferred to microcentrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 600g for 3 min. After the supernatant was aspirated, cells were resuspended in 200 µL of binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM KCl, and 1.8 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) and transferred to polystyrene test tubes. Two microliters of PI solution were used for each condition, while three microliters of annexin V were used for each condition. Cells were mixed by vortexing, and data were acquired by using a BD Fortessa and analyzed by FlowJo.

Cell viability

Jurkat, Molt-4, and Loucy cells in log growth were seeded at 100,000 cells/mL in 96-well plates in 100 μL and incubated for 72 h in the presence of compounds and fresh media. Ten microliters of CellQuantiBlue reagent was added per well for 2 h and scanned on a Victor5 Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA, USA) plate reader (ex550/em600).

Real-time RT polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Molt-4 cells were seeded at 100,000 cells/mL in 5 mL. Cells were incubated with appropriate compounds for 72 h. Total RNA was isolated with the TRIZOL (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The forward primer for NOTCH1 was 5′-AAT GCC TGC CTC ACC AA-3′. The reverse primer for NOTCH1 was 5′-CCA CAC TCG TTG ACA TCC T-3′. The forward primer for 18S was: 5′-TAA GTC CCT GCC CTT TGT AAC ACA-3′. The 18S reverse primer was 5′-GAT CCG AGG GCC TCA CTA AC-3′. RNA levels were determined with Nanodrop, and cDNA was made by using MMLV reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer’s protocol. SYBR green (Thermo Fisher) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol on a 7500 Applied Biosystems PCR machine. Relative mRNA levels were determined by 2–ΔΔCt values.

Luciferase assay

Cells were electroporated using established settings19 with 20 µg of pCIneoRL-Notch1 3′UTR DNA and 1 × 107 Jurkat cells. Jurkat cells were seeded at 1 × 105 in 24-well plates and treated with compounds. After 72 h, cells were centrifuged at 600 × g for 3 min and washed with PBS. Cells were lysed with Renilla lysis buffer (0.5× PBS, 0.025% NP-40, 1% EDTA (w/v), and freshly added 5 μM coelenterazine) and sonicated in a water bath, and immediately read on a Victor5 Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA, USA) plate reader for counts per second. A BCA assay was carried out to determine total protein concentration (Pierce, Waltham, MA, USA).

Western blotting analysis

Briefly, cells were resuspended in media at 250,000 cells/mL for 72 h with test compounds or solvent controls. Cells were then washed with PBS and lysed in either Whole Cell Lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 2% SDS, and 150 mM NaCl) followed by heating at 95 °C and passage through a 27½ gauge syringe or RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) containing freshly added protease and phosphatase inhibitors including aprotinin (1 μg/mL), leupeptin (1 μg/mL), pepstatin (1 μg/mL), PMSF (200 μM), sodium vanadate (200 μM), sodium diphosphate (10 μM), sodium fluoride (50 μM), and glycerophosphoric acid (10 μM) followed by incubation for 10 min on ice and centrifugation for 10 min at 4 °C at 14,000×g. Lysates were quantified by BCA assay. 1× SDS was added to the sample, and the sample was then heated for 4 min at 95 °C with vortexing. Equivalent masses were loaded onto 7.5 or 12% bis-acrylamide gels depending on protein size. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked with 5% BSA in TBS-T, and blotted with primary antibodies in blocking buffer. Alexa-Fluor 680 goat–anti-mouse IgG and IRDye 800CW goat–anti-rabbit IgG were used as secondary antibodies in TBS-T.

For the Triton X-114 separations of Rab7, membrane and cytosolic fractions were purified as described previously with some modifications19. Briefly, cells were resuspended in media at 250,000 cells/mL and treated with DGBP and/or test compounds for 72 h. After PBS wash, cells were lysed in Triton X-114 lysis buffer and processed for Western blots. Gels were loaded based on equivalent cell numbers/volumes.

Statistical analysis

One-way or two-way ANOVA was used to determine statistical significance as indicated in the figure legends. In either case, follow-up tests to compare individual treatments were done by using the Tukey method in GraphPad Prism. Control conditions were compared with treatment conditions or between pairs of conditions indicated in the graphs. An α of 0.05 was used to establish significance. Bar and line graphs represent mean ± SD. Experiments were replicated at least 3 times as indicated (n = 3).

Results

DGBP and lovastatin, but not zoledronate or DAPT, inhibit T-ALL proliferation

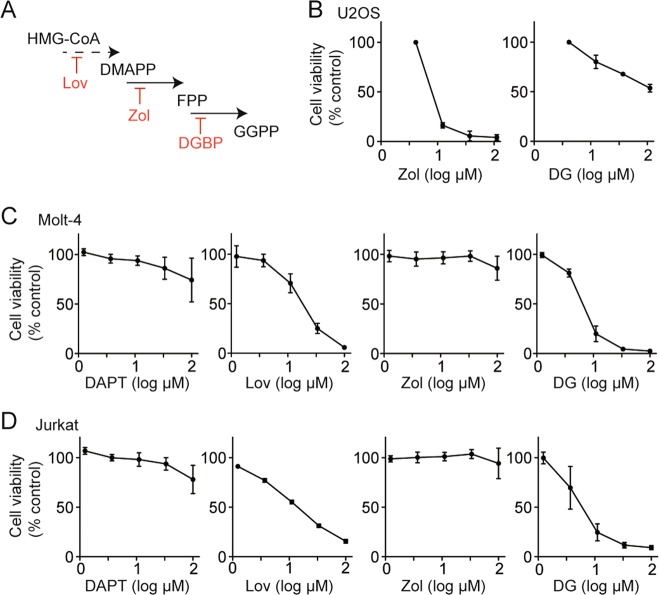

A recent report demonstrated that Rab GTPases regulate Notch1 processing11. Because Rab proteins are post-translationally geranylgeranylated, we asked whether geranylgeranylation inhibitors would affect Notch-dependent cells. We treated the T-ALL cell lines Molt-4 and Jurkat with the isoprenoid biosynthesis inhibitors lovastatin (inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase), zoledronate (inhibitor of farnesyl diphosphate synthase), and digeranyl bisphosphonate (DGBP) (inhibitor of geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase)13 (Fig. 1a) to investigate the effect on cell viability. Because zoledronate inhibits bone resorption and is active in cells of bone origin, as a control, we first assessed the impact of zoledronate and digeranyl bisphosphonate on U2OS osteosarcoma cells. Here, zoledronate was more potent than DGBP with strong activity at 10 µM, while DGBP only partially inhibited proliferation at 100 µM (Fig. 1b). In contrast, in the T-ALL cells, both DGBP and lovastatin decreased cell viability with DGBP demonstrating the stronger effect (Fig. 1c, d). Zoledronate did not impact Molt-4 and Jurkat cell viability at concentrations up to 100 µM. Thus, the pattern of zoledronate and DGBP activity is reversed in T-ALL cells in contrast to osteosarcoma. Although the active cellular concentrations are in the micromolar range, these concentrations are expected to be clinically achievable in the bone marrow environment due to the distribution kinetics driven by the bisphosphonate substructure. These values are also typical of charged bisphosphonates that require uptake by endocytic mechanisms32 and transporters33. We also evaluated the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT, which has been proposed as a route to disrupting Notch1 processing and function. Consistent with the literature34,35, DAPT did not strongly impact cell viability in this time frame (Fig. 1c, d).

Fig. 1. Impact of mevalonate pathway inhibitors and a γ-secretase inhibitor on cell viability.

a Mevalonate pathway inhibitors used in this study. HMG-CoA reductase is inhibited by lovastatin (Lov), farnesyl diphosphate synthase is inhibited by zoledronate (Zol), and geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase is inhibited by DGBP. b Impact of prenyl synthase inhibitors on viability of U2OS osteosarcoma cells. Graphs display means and standard deviations of two independent experiments for each compound. c, d Cell viability of Molt-4 (c) and Jurkat (d) cells after 72 h of treatment with the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT or the mevalonate pathway inhibitors lovastatin, zoledronate, or DGBP. Graphs display means and standard deviations of three independent experiments for each compound and cell line

GGDPS inhibition decreases expression of the Notch1 NICD and alters Rab7 localization

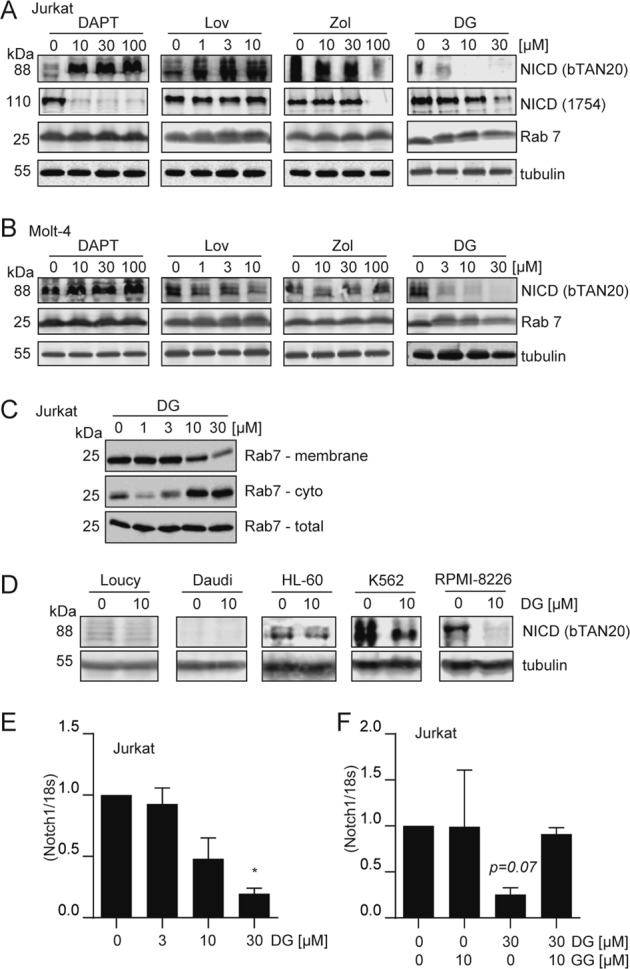

Because Notch1 is a critical oncogene that drives proliferation of T-ALL cells and it is required for proliferation of T-ALL cell lines including Jurkat cells36,37, we evaluated these compounds in Western blots to determine the effect on Notch1 expression. Of this panel, only DGBP completely and dose-dependently decreased Notch1 protein expression and levels of the Notch1 NICD in both Jurkat (Fig. 2a) and Molt-4 cells (Fig. 2b). The bands visualized are the predominant band on Notch1 Western blots by using the bTAN20 antibody (~88 kDa), corresponding to the predicted size of the human NICD (86 kDa)38. Both cell lines were resistant to γ-secretase inhibition (Fig. 1), and indeed no inhibitory effect was observed on the Notch1 NICD at concentrations up to 100 μM of DAPT in either cell line. However, use of a second Notch1 antibody specific to a cleaved form of Notch1 revealed an additional band at 110 kDa in Jurkat cells that was impacted by DAPT treatment. The 110-kDa band was not observed in the Molt-4 cells, and it was also not observed through probing with the bTAN20 antibody. Taken together, DAPT treatment increases the 88-kDa form of Notch1 and decreases the 110-kDa form of Notch1 with no impact on viability, while treatment with DGBP decreases both forms of Notch1 and impacts cell viability.

Fig. 2. Impact of mevalonate pathway inhibitors and a γ-secretase inhibitor on Notch1 and Rab7.

a, b Western blots for Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD) and Rab7 after 72 h of treatment with various concentrations of test compounds in Jurkat (a) and Molt-4 cells (b). Tubulin is shown as a loading control. Blots are representative of three independent experiments. c Membrane, cytosolic, and whole-cell fractions of Rab7 protein. Western blots are representative of three independent experiments. d Impact of DGBP on NICD expression in other hematopoietic cell lines. Western blots are representative of three independent experiments. e, f Notch1 mRNA expression relative to 18S rRNA. Cells were treated with DGBP alone or a combination with geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) for 72 h. In all graphs, the bars represent means and standard deviations of three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis. *p < 0.05 versus the corresponding control

As predicted, DGBP also increased the amount of the unprocessed non-geranylgeranylated Rab7 GTPase as indicated by a slight upward shift in the apparent molecular weight (Fig. 2a, b). Because the band shift is subtle and difficult to observe/interpret, we additionally performed cellular fractionation experiments to ensure that Rab7 localization was impacted by DGBP as desired (Fig. 2c). Here, DGBP dose-dependently decreased the fraction of Rab7 associated with the membrane while increasing the fraction of Rab7 in the cytoplasm. Thus, DGBP both depletes Notch1 NICD and impacts Rab7 processing and localization. The impact of DGBP on proliferation, Notch1 NICD expression, and Rab7 processing occurs within the 10–30 µM range.

GGDPS inhibition decreases expression of Notch1 in other hematological cell lines

In order to assess the prevalence of Notch1 regulation by GGDPS, we examined the impact of DGBP treatment on other non-T-ALL cell lines. Treatment with DGBP in various hematological cell lines revealed that DGBP reduces Notch1 NICD in cell lines expressing Notch1 (Fig. 2d). In Loucy cells, there is low Notch1 expression and no effect of DGBP on levels of NICD. However, RPMI-8226, K562, and to a lesser extent HL-60 cells expressed NICD that decreased with treatment of DGBP. Daudi cells had no expression of Notch1. Overall, in some non-T-ALL hematologic cell lines that express NICD, treatment with DGBP reduces Notch1 expression indicating that this is a conserved phenomenon, though it is most important in T-ALL cells given their dependence on Notch1.

GGDPS controls Notch1 mRNA expression

We were surprised that inhibition of GGDPS would have such a strong effect on Notch1 expression, and asked if additional gene expression mechanisms were involved. A prior study had shown that GGDPS inhibition can also impact mRNA expression through increased flux of the reactant FPP into sterol synthesis39. To examine whether GGDPS inhibition could also impact Notch1 expression at the mRNA level, we tested whether or not DGBP could impact the mRNA expression of Notch1 by using real-time PCR (Fig. 2e, f). Here, treatment with DGBP dose-dependently reduced Notch1 total mRNA expression (Fig. 2e). The effect of DGBP was prevented by co-incubation with GGPP (Fig. 2f). Therefore, DGBP reduces Notch1 expression at the mRNA level through specific engagement of GGDPS. Both Notch1 mRNA reduction and alteration of Rab7 localization happen at similar concentrations and may contribute to the impact of DGBP on Notch1.

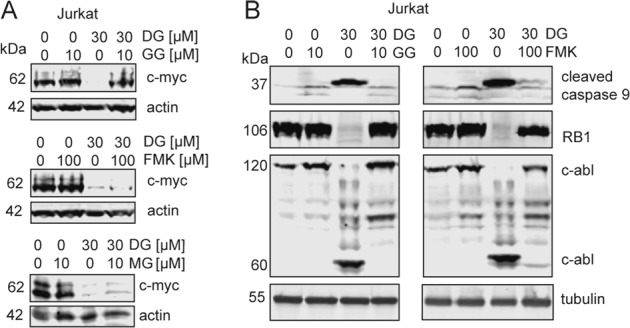

GGDPS inhibition decreases c-myc expression

We next sought to understand how reduced Notch1 expression caused by GGDPS inhibition would impact factors downstream of Notch1. Notch1 affects transcription of a variety of genes, notably including c-myc (MYC), which promotes oncogenesis in T-cell leukemia10,40. We treated Jurkat cells with DGBP and co-treated with GGPP or the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK. GGDPS inhibition decreased levels of c-myc protein expression, and co-treatment with GGPP restored the levels of c-myc (Fig. 3a). Co-treatment with Z-VAD-FMK did not rescue the effect of DGBP on c-myc (Fig. 3a), indicating that the impact on the Notch/myc axis is not downstream of caspase activation. Co-treatment of DGBP with the proteasome inhibitor, MG132, did not rescue the effect of DGBP on c-myc depletion, consistent with transcriptional regulation of c-myc downstream of Notch1 rather than increased c-myc protein degradation (Fig. 3a). Therefore, GGDPS inhibition reduces expression of Notch1 and transcription of the Notch1 effector c-myc in a way that is upstream or independent of cleaved caspases.

Fig. 3. DGBP impacts c-myc expression independent of caspases and impacts RB and c-abl expression dependent upon caspases.

a Western blots showing c-myc with DGBP treatment and co-treatment of GGPP, Z-VAD-FMK, or MG132 in Jurkat cells. Actin is shown as a loading control. All Western blots are representative of three independent experiments. b Western blot analysis of cleaved caspase 9, retinoblastoma (RB1), and c-abl. Tubulin is shown as a loading control. Jurkat cells were treated for 72 h with DGBP in the presence or absence of GGPP or Z-VAD-FMK. Western blots are representative of three independent experiments

GGDPS inhibition impacts signaling to caspases and apoptosis

To determine how GGDPS inhibition affects caspases, we treated Jurkat cells with DGBP and either GGPP or Z-VAD-FMK (Fig. 3b). As expected, DGBP treatment increased the expression of cleaved caspase 9. The effect of DGBP on cleaved caspase 9 was fully rescued by GGPP and Z-VAD-FMK. The pattern was also observed with retinoblastoma protein (RB1) expression. Furthermore, DGBP treatment decreased the 120-kDa fraction of c-abl and increased expression of the 60-kDa cleavage product of c-abl. The effect on c-abl was rescued by co-treatment with GGPP and by co-treatment with Z-VAD-FMK. Therefore, the effects of DGBP on caspase 9, RB1, and c-abl were all rescued by Z-VAD-FMK and are downstream of caspase activation. While c-abl activation is thought to be upstream of cleaved caspases in some circumstances, cleaved caspases have been previously shown at times to cleave c-abl41. Thus, DGBP allows for Jurkat cells to enter apoptosis through activation of caspases, depletion of retinoblastoma, and stimulation of caspase-mediated c-abl cleavage.

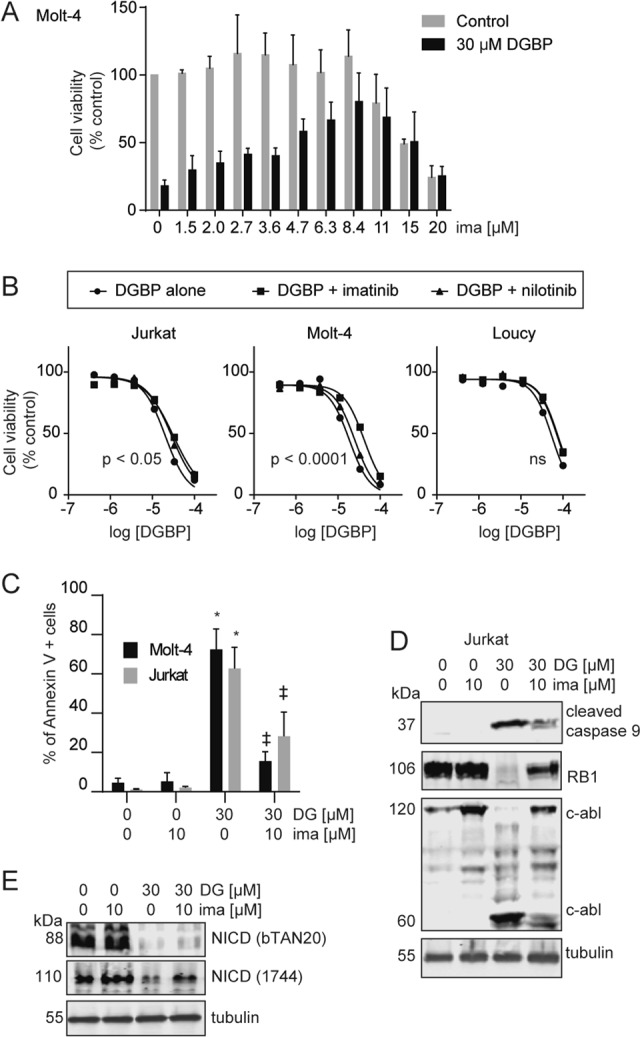

c-abl mediates apoptosis induced by GGDPS inhibition downstream of caspases in T-ALL

Surprised that c-abl was acting downstream of caspases in this system, we wanted to further assess the role of c-abl in apoptosis induced by GGDPS inhibition. We co-treated cells with DGBP and the c-abl inhibitors imatinib or nilotinib and determined their impact on viability, apoptosis, and protein expression. Imatinib dose-dependently reduced the impact of DGBP on Molt-4 viability with a peak impact of around 10 µM and EC50 of 3.5 µM (Fig. 4a). Both imatinib and nilotinib reduced the severity of DGBP on proliferation in Jurkat and Molt-4 cells but not in Loucy cells (Fig. 4b), which do not express Notch1 (Fig. 2c). We assessed the degree of apoptosis by Annexin V staining. Here, DGBP-induced apoptosis was blocked by imatinib in both Jurkat and Molt-4 cells (Fig. 4c). Co-treatment with imatinib also restored expression of the 120-kDa form of c-abl and partially reduced expression of the 60-kDa form (Fig. 4d). The effect of DGBP on cleaved caspase 9 was also partially rescued by imatinib co-treatment. Co-treatment with imatinib did not affect the ability of GGDPS inhibition to reduce expression of the 88-kDa Notch1 band (Fig. 4e). Together, c-abl acts downstream or independently of Notch1 to mediate DGBP-induced apoptosis; however, it may have functions both upstream and downstream of caspases.

Fig. 4. Inhibitors of c-abl are protective against apoptosis induced by DGBP, downstream of Notch1 and caspases.

a Dose response of Molt-4 cell viability after treatment with or without 30 µM DGBP and the indicated concentrations of imatinib for 72 h. b Dose response of Molt-4, Jurkat, and Loucy cell viability with DGBP in combination with either 10 µM imatinib or 10 µM nilotinib for 72 h. The X axis represents the log of the molar concentration. Curves were generated by nonlinear regression by using a variable slope four-parameter model. The indicated p values represent confidence in whether the IC50 values differed between conditions. c Molt-4 or Jurkat cells were treated with DGBP with or without imatinib for 72 h and assessed by Annexin V staining. Flow plots shown are representative of three independent experiments. The bars represent means and standard deviations of three independent experiments (n = 3). The results were analyzed by using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis. *p < 0.05 versus untreated controls. ‡p < 0.05 versus DGBP-treated condition. d Western blotting analysis of cleaved caspase 9, retinoblastoma, and c-abl. Tubulin is shown as a loading control. Jurkat cells were treated for 72 h with DGBP in the presence or absence of imatinib. Western blots are representative of three independent experiments. e Western blot analysis of NICD. Tubulin is shown as a loading control. Jurkat cells were treated for 72 h with DGBP in the presence or absence of imatinib. Western blots are representative of three independent experiments

GGDPS inhibition increases the DNA-damage response

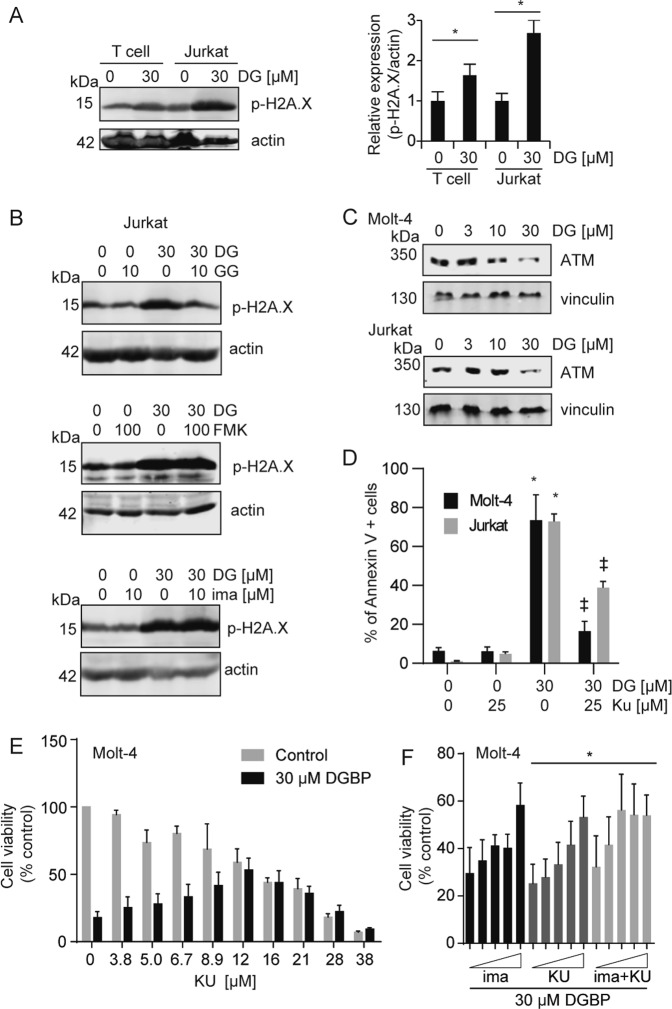

A recent report demonstrated that Notch1 can directly negatively regulate the DNA-damage response42. The DNA-damage response in Jurkat cells treated with DGBP is higher than that of primary T cells treated with DGBP as demonstrated by phosphorylated histone H2A.X (Fig. 5a). The effect of DGBP on p-H2A.X was rescued by GGPP, but not by Z-VAD-FMK or imatinib (Fig. 5b). Because a study by Vermezovic et al. found that Notch1 binds to the kinase regulatory domain of ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), and prevents ATM activation42, we set out to determine if GGPP depletion regulates Notch1 to induce ATM activation and the DNA-damage response. By using an ATM inhibitor (Ku55933), we tested whether ATM was required for the apoptotic effects of GGDPS inhibition. DGBP treatment dose-dependently decreased ATM expression (Fig. 5c). Treatment of Molt-4 and Jurkat cells with Ku55933 in combination with DGBP reduced the apoptosis induced by DGBP (Fig. 5d). Ku55933 also dose-dependently reduced the impact of DGBP on Molt-4 viability with a peak impact of around 12 µM and EC50 of 6.8 µM (Fig. 5e). At concentrations below the EC50, the combination of imatinib and Ku55933 was additive (Fig. 5f).

Fig. 5. DGBP-induced apoptosis is mediated by ATM.

a Western blot analysis of phosphorylated H2A.X in either expanded primary T cells or Jurkat cells after 72 h of treatment with DGBP, with actin shown as a loading control. b Western blotting analysis of p-H2A.X. Actin is shown as a loading control. Jurkat cells were treated for 72 h with DGBP in the presence or absence of GGPP, Z-VAD-FMK, or imatinib. Western blots are representative of three independent experiments. c Western blot analysis of ATM expression in Molt-4 or Jurkat cells treated with DGBP for 72 h, with vinculin as a loading control. d Annexin V staining showing 72 h of DGBP treatment along with co-treatment with or without the ATM inhibitor Ku55933 in Molt-4 and Jurkat cells. The bars represent means and standard deviations of three independent experiments (n = 3). e Dose response of Molt-4 cell viability after treatment with or without 30 µM DGBP and the indicated concentrations of Ku55933 for 72 h. The bars represent means and standard deviations of three independent experiments (n = 3). f Dose response of imatinib, Ku55933, or the combination of both inhibitors. The bars represent means and standard deviations of three independent experiments (n = 3). Panel (a) was analyzed by using a T test, while panels (d, e) were analyzed by using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis. *p < 0.05 versus controls. ‡p < 0.05 versus DGBP-treated condition

Notch1 depletion and cellular apoptosis induced by GGDPS inhibition are restored by γ-secretase inhibition

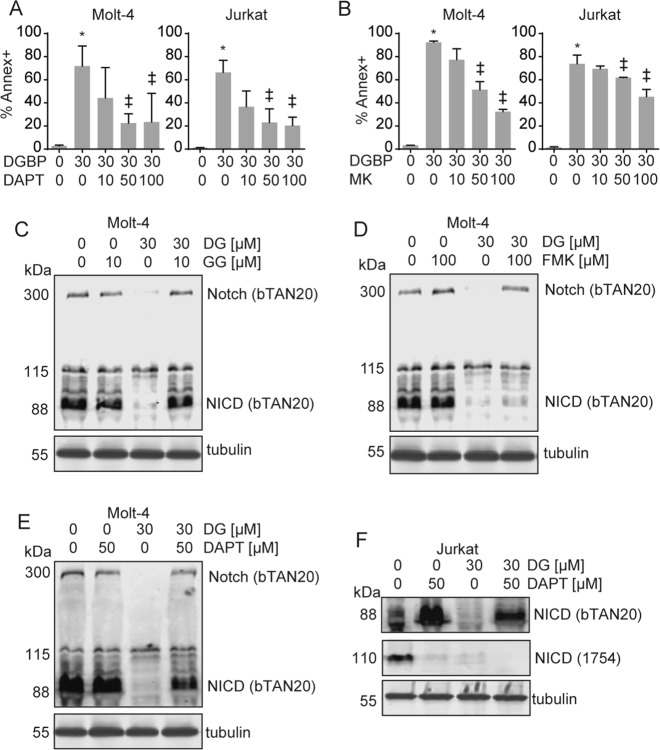

To further assess the relationship between GGDPS and Notch1 in T-ALL cells, we hypothesized that co-treatment with DGBP and DAPT would more strongly impact proliferation and viability than either agent alone. On the contrary, co-incubation with DGBP and DAPT actually improved cell viability relative to treatment with DGBP alone. In this regard, both DAPT and a second γ-secretase inhibitor MK-0752 dose-dependently reduced the effect of DGBP on apoptosis (Fig. 6a, b). Thus, in these T-ALL cell lines, γ-secretase works against viability and secretase inhibitors improve viability.

Fig. 6. Secretase inhibitors rescue the effect of DGBP on apoptosis.

a, b Annexin V staining of Molt-4 or Jurkat cells treated with DGBP and co-treated with or without (a) DAPT or (b) MK-0752 for 72 h. Graphs represent means and standard deviations of three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis. *p < 0.05 versus untreated controls. ‡p < 0.05 versus DGBP-treated condition. c, d Western blot of full-length Notch1 and NICD in Molt-4 cells following 72 h of treatment with DGBP and co-treatment with or without either the GGDPS product GGPP (c) or the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK (d). Tubulin is shown as a loading control. e, f Western blots of Notch1 and NICD after 72 h of treatment with DGBP and co-treatment with or without DAPT in Molt-4 (e) and Jurkat (f) cells. All Western blots are representative of three independent experiments

We next examined how this combination would affect expression of Notch1. First, as controls, we found that as expected, GGPP antagonized the reduction in Notch1 expression caused by DGBP (Fig. 6c), while co-incubation with Z-VAD-FMK did not impact the ability of DGBP to decrease NICD expression (Fig. 6d). This is further evidence that the impact of GGDPS inhibition on Notch1 expression is not a generalized nonspecific phenomenon downstream of caspase activation. To determine whether or not GGDPS reduces Notch1 expression upstream or downstream of γ-secretase cleavage, we co-treated cells with the γ-secretase inhibitor (DAPT) in combination with DGBP. DAPT restored protein levels of the 88-kDa band of Notch1 with DGBP co-incubation in both Molt-4 (Fig. 6e) and Jurkat cells (Fig. 6f). The 110-kDa Notch1 band was decreased in Jurkat cells by both DAPT and DGBP (Fig. 6f). Therefore, DGBP reduces expression of both the 88- and the 110-kDa Notch1 band and decreases cell viability, while DAPT changes the relative amounts of the 88- and the 110-kDa Notch1 band and improves cell viability.

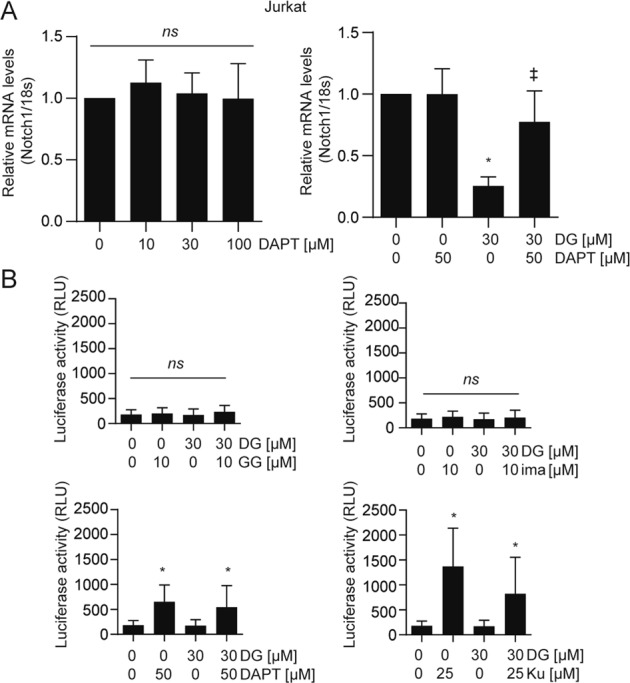

GGDPS controls Notch1 mRNA expression, while secretase and ATM, but not GGDPS or c-abl, control Notch1 mRNA degradation

Because GGDPS inhibition had affected Notch1 expression through impacts on both its processing and its mRNA expression (Fig. 2), we investigated whether γ-secretase inhibition would also impact Notch1 mRNA expression. In this regard, treatment with DAPT alone had no impact on Notch1 total mRNA expression (Fig. 7a). Surprisingly, the effect of DGBP on Notch1 mRNA expression was prevented by co-incubation with DAPT (Fig. 7a). This indicates a role for γ-secretase in regulating not only the processing of Notch1 but also its gene expression.

Fig. 7. DAPT and Ku55933 restore the DGBP-induced depletion of Notch1 mRNA via decreased mRNA degradation.

a Notch1 mRNA expression relative to 18S rRNA. Jurkat cells were treated with inhibitor alone or combinations for 72 h. b Luciferase activity in Jurkat cells transfected with Notch1 3′UTR. Cells were treated with inhibitor alone or co-treated with DGBP for 72 h. In all graphs, the bars represent means and standard deviations of three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis. *p < 0.05 versus the corresponding control. ‡p < 0.05 versus DGBP-treated condition

Notch1 mRNA expression is regulated by miR-200 interaction with the Notch1 3′UTR, which can be analyzed with a luciferase reporter construct that contains the luciferase gene flanked by the Notch1 3′UTR31. We assessed the ability of DGBP and the rescue agents to affect the miR-200-mediated regulation of Notch1 mRNA degradation. Treatment with DGBP did not significantly alter Notch1 mRNA stability in this system (Fig. 7b), meaning that the DGBP-induced reduction of Notch1 mRNA expression is not due to increased degradation. Treatment with imatinib also did not impact Notch1 mRNA degradation. However, treatment with DAPT and Ku55933 decreased degradation of luciferase mRNA fused to the Notch1 3′UTR leading to elevated luciferase activity. These data suggest that miR-200 not only regulates Notch, but also that miR-200 is itself regulated by secretase and ATM.

Discussion

Notch proteins are critical to development and progression of cancers including T-ALL. In this study, we demonstrate that inhibition of the enzyme GGDPS reduces Notch1 expression and impacts factors known to be downstream of Notch1. These experiments provide evidence for regulation of Notch1 by lipid synthesis, and disruption of this mechanism can impact Notch1 expression and viability of Notch1-dependent cells.

DGBP is more effective than the secretase inhibitor DAPT and the other isoprenoid biosynthesis inhibitors at decreasing cell viability (Fig. 1) and levels of NICD (Fig. 2). The decrease in NICD is likely a result of at least two underlying mechanisms—(1) inhibition of post-translational processing of Rab proteins that are required for Notch1 trafficking, and (2) altered transcription of Notch1 itself. Immediately downstream effects include reduced c-myc expression, increased p-H2A.X, and decreased ATM expression, resulting in caspase-dependent apoptosis that is associated with decreased retinoblastoma expression and cleaved c-abl (Fig. 3). Using GGDPS inhibitors to target Notch1 signaling may be a promising therapeutic strategy because Rab GTPases are required for Notch1 processing11. While direct inhibitors of γ-secretase may prevent Notch1 signaling in some cases, certain mutations to Notch1 may confer insensitivity to secretase processing. Because Rab GTPases are expected to be involved in both normal and mutant Notch1 processing, disrupting GTPase function via inhibition of GGDPS allows for Notch1 disruption even in the event of mutations to Notch1.

Because γ-secretase has been proposed as an anti-Notch1 target, we evaluated combinations of secretase inhibitors and DGBP to look for potential synergies. We surprisingly found that DAPT reduces the ability of DGBP to promote apoptosis (Fig. 6), and Notch1 mRNA degradation is regulated by DAPT. The impact of DGBP and DAPT on NICD expression is more nuanced. In agreement with a prior study43, treatment with DAPT not only decreases expression of the NICD detected by the cleaved Notch1 antibody as expected, but also increases expression of NICD detected by a total Notch1 antibody. DGBP clearly reduces the NICD detected by both antibodies. In combination, the effect of DAPT on NICD expression can overcome the effect of DGBP, which correlates with the ability of DAPT to reduce DGBP-induced apoptosis. Therefore, GGDPS inhibition depletes NICD, while a γ-secretase inhibitor, DAPT, alters NICD expression. We speculate that this may occur because DAPT is a non-transition-state inhibitor of the γ-secretase complex that does not bind to the active site of the γ-secretase complex protease presenilin-1, but rather to an allosteric site within presenilin-18. Because there are mutations along the transmembrane region of Notch144, the binding conformation of the mutated α-helix may be different from the wild type. Binding of DAPT in these cases may allow for allosteric modulation rather than inhibition of the catalytic domain. Interestingly, there is overlap between the reported binding site of DAPT on presenilin-1 (aa372–467)45 and the binding site of Rab11 on presenilin-1 (aa374–400)46. Perhaps, binding of DAPT mimics binding of Rab to enable secretase processing of Notch1—though further experiments would be needed to confirm this hypothesis.

There is evidence in favor of repurposing isoprenoid biosynthesis inhibitors such as lovastatin and zoledronate for anticancer applications because zoledronate is currently used in the clinic for metastatic bone disease, and these inhibitors can lead to apoptosis47,48. Originally developed for non-cancer applications, these drugs have generated much interest for their potential anticancer properties. For example, a recent article showed that statins could sensitize leukemia cells to venetoclax, a BCL-2 inhibitor, in a way that is dependent upon GGPP depletion49. Interestingly, we observed GGDPS inhibition to affect Notch1 more strongly than HMG-CoA reductase and farnesyl diphosphate synthase inhibition18,50. One potential explanation for this phenomenon is that, unlike GGDPS, both HMG-CoA reductase and farnesyl diphosphate synthase are under transcriptional control through sterols51, which can mitigate the effects of these agents39,52,53. Alternatively, they may differ in rates of uptake depending on the cell line. As zoledronate has a higher charge:mass ratio than DGBP, its cellular entry is more likely to rely on endocytosis32.

We show that once DGBP reduces Notch1 expression, there is a twofold effect on downstream signaling: (1) decreased transcription of c-myc, and (2) induction of p-H2AX, a marker of the DNA-damage response. C-myc is a well-known downstream target of Notch1 in T-ALL10,40,54, while Notch1 has been reportedly involved in the DNA-damage response42. A potential mechanism is that DGBP-induced depletion of the NICD may free ATM to become activated and phosphorylate H2A.X, a marker for DNA damage55. While our studies did show rescue of DGBP-induced apoptosis by an ATM inhibitor, it remains possible that the inhibitor could disrupt function of other kinases affecting H2A.X, and further studies would be needed to conclusively determine whether ATM is mediating phosphorylation of H2A.X in this system. We propose that GGPP depletion does not directly increase DNA damage, but rather allows for cells to recognize the level of DNA damage. In this scenario, ATM would then activate cleaved caspases and initiate apoptosis56, while caspases would cleave retinoblastoma protein, which sits on the catalytic domain of c-abl and prevents its activation57. There is some precedence for Notch1 involvement in retinoblastoma protein degradation as a γ-secretase inhibitor regulates retinoblastoma to exit the cell cycle34. Furthermore, lovastatin and nitrogenous bisphosphonates regulate retinoblastoma protein via hypophosphorylation58. This reduction in retinoblastoma levels allows for caspases to cleave c-abl41,59. Alternatively, c-abl has been previously shown to be part of an ATM complex that activates in response to ionizing radiation60. However, in our studies, imatinib was not able to rescue the effect of DGBP on p-H2A.X, while the caspase inhibitor did rescue the effect of DGBP on c-abl cleavage, suggesting that the major effect of abl is downstream of caspases in this system. Together, these data indicate the connection between disruption of geranylgeranylation and induction of apoptosis in T-ALL.

Finally, we found that GGPP depletion decreases Notch1 mRNA levels but does not affect Notch1 mRNA degradation. miR-200 interacts with Notch1 signaling in cancer stem cells in breast cancer61 and pancreatic cancer62. Interestingly, only DAPT and Ku55933 impact Notch1 mRNA degradation. We predict that both of these inhibitors act on miR-200 through ATM inhibition with Ku55933 directly inhibiting ATM and DAPT acting indirectly. Further studies aimed at understanding the impact of secretase and ATM inhibitors on Notch1 expression in the context of anti-proliferative agents such as DGBP would certainly be of interest.

Acknowledgements

Assistance with flow cytometry from Dr. Wu He is appreciated. Assistance with Western blots from Megan Schladetsch is appreciated. DGBP was a generous gift from Dr. David Wiemer at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA. Financial support from the University of Connecticut Vice President for Research (Research Excellence Program) is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflict of interest

DGBP is covered by a patent that is owned by the University of Iowa. A.J.W. owns shares in Terpenoid Therapeutics, Inc., which has licensed the patent.

Footnotes

Edited by H.-U. Simon

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pui CH, Relling MV, Downing JR. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:1535–1548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanchez-Martin M, et al. Synergistic antileukemic therapies in NOTCH1-induced T-ALL. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:2006–2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611831114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weng AP, et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306:269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brzozowa-Zasada M, et al. Notch and its oncogenic activity in human malignancies. Eur. Surg. 2017;49:199–209. doi: 10.1007/s10353-017-0491-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radtke F, Raj K. The role of Notch in tumorigenesis: oncogene or tumour suppressor? Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:756–767. doi: 10.1038/nrc1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson ER, Sandberg R, Lendahl U. Notch signaling: simplicity in design, versatility in function. Development. 2011;138:3593–3612. doi: 10.1242/dev.063610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Passaro D, Quang CT, Ghysdael J. Microenvironmental cues for T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia development. Immunol. Rev. 2016;271:156–172. doi: 10.1111/imr.12402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsauskas-Kuprys R, Zlobin A, Osipo C. Gamma secretase inhibitors of Notch signaling. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:943–955. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S33766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon WR, et al. Structural basis for autoinhibition of Notch. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez-Martin M, Ferrando A. The NOTCH1-MYC highway toward T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2017;129:1124–1133. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-692582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Court H, Ahearn IM, Amoyel M, Bach EA, Philips MR. Regulation of NOTCH signaling by RAB7 and RAB8 requires carboxyl methylation by ICMT. J. Cell Biol. 2017;216:4165–4182. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201701053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doi K, et al. Crucial role of the Rap G protein signal in Notch activation and leukemogenicity of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:7978. doi: 10.1038/srep07978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shull LW, Wiemer AJ, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. Synthesis and biological activity of isoprenoid bisphosphonates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:4130–4136. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiemer AJ, Tong H, Swanson KM, Hohl RJ. Digeranyl bisphosphonate inhibits geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;353:921–925. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maalouf MA, Wiemer AJ, Kuder CH, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. Synthesis of fluorescently tagged isoprenoid bisphosphonates that inhibit protein geranylgeranylation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:1959–1966. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiemer AJ, Yu JS, Lamb KM, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. Mono- and dialkyl isoprenoid bisphosphonates as geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:390–399. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiemer AJ, et al. Pivaloyloxymethyl-modified isoprenoid bisphosphonates display enhanced inhibition of cellular geranylgeranylation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:3652–3660. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiemer AJ, Wiemer DF, Hohl RJ. Geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase: an emerging therapeutic target. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011;90:804–812. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agabiti SS, Li J, Wiemer AJ. Geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase inhibition induces apoptosis that is dependent upon GGPP depletion, ERK phosphorylation and caspase activation. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2678. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiemer AJ, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. The intermediate enzymes of isoprenoid metabolism as anticancer targets. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2009;9:526–542. doi: 10.2174/187152009788451860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agabiti SS, Liang Y, Wiemer AJ. Molecular mechanisms linking geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase to cell survival and proliferation. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2016;33:1–11. doi: 10.1080/09687688.2016.1213432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haney SL, et al. Preclinical investigation of a potent geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase inhibitor. Invest. New Drugs. 2018;36:810–818. doi: 10.1007/s10637-018-0571-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lacbay CM, et al. Unraveling the prenylation-cancer paradox in multiple myeloma with novel geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase (GGPPS) inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:6904–6917. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matthiesen RA, et al. Alpha-Methylation enhances the potency of isoprenoid triazole bisphosphonates as geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018;26:376–385. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, et al. Simultaneous site-specific dual protein labeling using protein prenyltransferases. Bioconjug. Chem. 2015;26:2542–2553. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeong A, Suazo KF, Wood WG, Distefano MD, Li L. Isoprenoids and protein prenylation: implications in the pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention of Alzheimer’s disease. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018;53:279–310. doi: 10.1080/10409238.2018.1458070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coxon FP, et al. Synthesis and characterization of novel phosphonocarboxylate inhibitors of RGGT. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;84:77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.06.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou X, et al. Triazole-based inhibitors of geranylgeranyltransferase II. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:764–766. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.11.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zagouras P, Stifani S, Blaumueller CM, Carcangiu ML, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Alterations in Notch signaling in neoplastic lesions of the human cervix. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:6414–6418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin JJ. Monoclonal antibodies against myofibrillar components of rat skeletal muscle decorate the intermediate filaments of cultured cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:2335–2339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.4.2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang T, et al. A genetic cell context-dependent role for ZEB1 in lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12231. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson K, Rogers MJ, Coxon FP, Crockett JC. Cytosolic entry of bisphosphonate drugs requires acidification of vesicles after fluid-phase endocytosis. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;69:1624–1632. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.020776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu Z, et al. Identification of a transporter complex responsible for the cytosolic entry of nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates. eLife. 2018;7:e36620. doi: 10.7554/eLife.36620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rao SS, et al. Inhibition of NOTCH signaling by gamma secretase inhibitor engages the RB pathway and elicits cell cycle exit in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3060–3068. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Neil J, et al. FBW7 mutations in leukemic cells mediate NOTCH pathway activation and resistance to gamma-secretase inhibitors. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1813–1824. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huo L, et al. Effect of dihydroarteminin combined with siRNA targeting Notch1 on Notch1/c-Myc signaling in T-cell lymphoma cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018;15:3059–3065. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.5784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zou J, et al. Notch1 is required for hypoxia-induced proliferation, invasion and chemoresistance of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2013;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fox V, et al. Cell-cell signaling through NOTCH regulates human embryonic stem cell proliferation. Stem Cells. 2008;26:715–723. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dudakovic A, et al. Inhibition of geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase induces apoptosis through multiple mechanisms and displays synergy with inhibition of other isoprenoid biosynthetic enzymes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;324:1028–1036. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.132217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weng AP, et al. c-Myc is an important direct target of Notch1 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2096–2109. doi: 10.1101/gad.1450406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barila D, et al. Caspase-dependent cleavage of c-Abl contributes to apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:2790–2799. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.8.2790-2799.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vermezovic J, et al. Notch is a direct negative regulator of the DNA-damage response. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:417–424. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Keersmaecker K, et al. In vitro validation of gamma-secretase inhibitors alone or in combination with other anti-cancer drugs for the treatment of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2008;93:533–542. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Forbes SA, et al. COSMIC: somatic cancer genetics at high-resolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D777–D783. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dumanchin C, et al. Presenilins interact with Rab11, a small GTPase involved in the regulation of vesicular transport. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:1263–1269. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.7.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morohashi Y, et al. C-terminal fragment of presenilin is the molecular target of a dipeptidic gamma-secretase-specific inhibitor DAPT (N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-L-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:14670–14676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carter JA, Botteman MF. Health-economic review of zoledronic acid for the management of skeletal-related events in bone-metastatic prostate cancer. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2012;12:425–437. doi: 10.1586/erp.12.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fournier PG, et al. Lowering bone mineral affinity of bisphosphonates as a therapeutic strategy to optimize skeletal tumor growth inhibition in vivo. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8945–8953. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee JS, et al. Statins enhance efficacy of venetoclax in blood cancers. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018;10:eaaq1240. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaq1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pandyra A, et al. Immediate utility of two approved agents to target both the metabolic mevalonate pathway and its restorative feedback loop. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4772–4782. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pandyra AA, et al. Genome-wide RNAi analysis reveals that simultaneous inhibition of specific mevalonate pathway genes potentiates tumor cell death. Oncotarget. 2015;6:26909–26921. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor. Cell. 1997;89:331–340. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dudakovic A, Tong H, Hohl RJ. Geranylgeranyl diphosphate depletion inhibits breast cancer cell migration. Invest. New Drugs. 2011;29:912–920. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9446-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharma VM, et al. Notch1 contributes to mouse T-cell leukemia by directly inducing the expression of c-myc. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:8022–8031. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01091-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matt S, Hofmann TG. The DNA damage-induced cell death response: a roadmap to kill cancer cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016;73:2829–2850. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2130-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Korwek Z, et al. Inhibition of ATM blocks the etoposide-induced DNA damage response and apoptosis of resting human T cells. DNA Repair. 2012;11:864–873. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang JY, Naderi S, Chen TT. Role of retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein in DNA damage response. Acta Oncol. 2001;40:689–695. doi: 10.1080/02841860152619098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reszka AA, Halasy-Nagy J, Rodan GA. Nitrogen-bisphosphonates block retinoblastoma phosphorylation and cell growth by inhibiting the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway in a keratinocyte model for esophageal irritation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;59:193–202. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Machuy N, Rajalingam K, Rudel T. Requirement of caspase-mediated cleavage of c-Abl during stress-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:290–300. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baskaran R, et al. Ataxia telangiectasia mutant protein activates c-Abl tyrosine kinase in response to ionizing radiation. Nature. 1997;387:516–519. doi: 10.1038/387516a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shimono, Y., Mukohyama, J., Nakamura, S. & Minami, H. MicroRNA regulation of human breast cancer stem cells. J. Clin. Med. 5, 1–24 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Xu YF, Hannafon BN, Ding WQ. microRNA regulation of human pancreatic cancer stem cells. Stem Cell Investig. 2017;4:5. doi: 10.21037/sci.2017.01.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]