Abstract

Takifugu bimaculatus is a native teleost species of the southeast coast of China where it has been cultivated as an important edible fish in the last decade. Genetic breeding programs, which have been recently initiated for improving the aquaculture performance of T. bimaculatus, urgently require a high-quality reference genome to facilitate genome selection and related genetic studies. To address this need, we produced a chromosome-level reference genome of T. bimaculatus using the PacBio single molecule sequencing technique (SMRT) and High-through chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) technologies. The genome was assembled into 2,193 contigs with a total length of 404.21 Mb and a contig N50 length of 1.31 Mb. After chromosome-level scaffolding, 22 chromosomes with a total length of 371.68 Mb were constructed. Moreover, a total of 21,117 protein-coding genes and 3,471 ncRNAs were annotated in the reference genome. The highly accurate, chromosome-level reference genome of T. bimaculatus provides an essential genome resource for not only the genome-scale selective breeding of T. bimaculatus but also the exploration of the evolutionary basis of the speciation and local adaptation of the Takifugu genus.

Subject terms: Genome, Sequencing, DNA sequencing, Ichthyology

| Measurement(s) | whole genome sequencing assay • transcription profiling assay |

| Technology Type(s) | DNA sequencing • RNA sequencing |

| Factor Type(s) | organism part |

| Sample Characteristic - Organism | Takifugu bimaculatus |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: 10.6084/m9.figshare.9793001

Background & Summary

Takifugu, belongs to Tetraodontidae in Tetraodontiformes, is native to estuaries and the offshore area of the northwest Pacific1. Despite the lethal amounts of tetrodotoxin in their bodies, Takifugu are still considered a delicacy in East Asia. Takifugu is also an established teleost model species due to its compact genome. As the first sequenced teleost genome, the genome of Takifugu rubripes was completely sequenced in 20021. Another important Takifugu species, Takifugu bimaculatus (Fig. S1a), is a typically endemic species in the marginal sea from the south Yellow Sea to the South China Sea. T. bimaculatus inhabits lower latitudes and adapts to higher temperatures than T. rubripes2, providing an excellent model for exploring thermal adaptation and adaptive divergence in teleost fishes. In the past decade, T. bimaculatus has been widely cultured in southeast China, where the temperature is beyond the upper thermal tolerance of T. rubripes. Recently, genetic breeding programs of T. bimaculatus have been initiated, mainly aiming to improve growth rates and disease resistance under aquaculture conditions. Therefore, there is an urgent need to collect sufficient genetic materials and genome resources to facilitate genome-scale studies and selective breeding. However, a highly accurate, chromosome-level reference genome of subtropical Takifugu species is still lacking, which hinders the progress of genetic improvement and genetic studies of its thermal plasticity and adaptation at lower latitudes.

In this report, we provided a chromosome-level reference genome of T. bimaculatus using a combination of the PacBio single molecule sequencing technique (SMRT) and high-through chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) technologies. We assembled the genome sequences into 2,193 contigs with a total length of 404.21 Mb and a contig N50 length of 1.31 Mb. After chromosome-level scaffolding, 22 scaffolds were constructed corresponding to 22 chromosomes with a total length of 371.68 Mb (92% of the total length of all contigs). Furthermore, we identified 109.92 Mb (27.20% of the assembly) of repeat content, 21,117 protein-coding genes and 3,471 ncRNAs. In addition, we also assembled a chromosome-level reference genome of Larimichthys crocea3, which is one of the top commercial marine fishery species in China, via almost the same strategy. The wo high-quality assembled genomes confirmed the stability and suitability of this strategy for marine fishes. The availability of a chromosome-level, well-annotated reference genome is essential to support basic genetic studies and will contribute to genome-scale selective breeding programs for these important maricultural species.

Methods

Ethics statement

The T. bimaculatus used in this work were obtained from Zhangzhou, Fujian Province, China. This work was approved by the Animal Care and Use committee at the College of Ocean and Earth Sciences, Xiamen University. All the methods used in this study were carried out following approved guidelines.

Sample collection and nucleic acid preparation

Two healthy female T. bimaculatus was collected from an off-shore area by the Fujian Takifugu Breeding Station in Zhangzhou, Fujian Province, China (Fig. S1b); one of fish was used for SMRT and RNA sequencing, and the other fish was used for Hi-C. The muscle was collected for DNA extraction and nine different tissues (Table S1) were collected for RNA extraction. To protect the integrity of the DNA, all samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for 20 min and then stored at −80 °C. Sufficient frozen muscle tissues were lysed in SDS digestion buffer with proteinase K, and high-molecular-weight (HMW) genomic DNA (gDNA) for SMRT and Hi-C was extracted by AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, UK), washed with 70% alcohol and dissolved in nuclease-free water. In addition, normal-molecular-weight (NMW) gDNA for Illumina sequencing was also extracted from muscle tissues using the established method4. Total RNA was extracted using the TRIZOL Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) from different tissues following the manufacturer’s protocol5 and mixed equally for RNA-Seq. Nucleic acid concentrations were quantified using a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and then checked by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis stained for integrity.

Library construction and sequencing

A genome survey was performed based on Illumina short reads for estimating genome size, heterozygosity and repeat content, which provides a basic evaluation before we started the large scale whole genome sequencing. A library with a 350 bp insert size was constructed from NMW gDNA following the standard protocol provided by Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA). The library was then sequenced with a paired-end sequencing strategy using the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform, and the read length was 2 × 150 bp. Finally, ~53.43 Gb raw data were generated. After removing the low-quality bases and paired reads with the Illumina adaptor sequence using SolexaQA++ 6 (version v.3.1.7.1), a total of ~53.28 Gb clean reads, were retained for the genome survey (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of genome sequencing data generated with multiple sequencing technologies.

| Library Type | Insert Size (bp) | Raw Data (Gb) | Clean Data (Gb) | Average Read Length (bp) | N50 Read Length (bp) | Sequencing Coverage (X) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | 350 | 53.43 | 53.28 | 150 | 150 | 135.52 |

| PacBio | 20,000 | 28.97 | — | 7,505 | 12,513 | 73.69 |

| Hi-C | — | 46.39 | 46.13 | 150 | 150 | 117.8 |

| RNA-Seq | — | 21.35 | 20.95 | 150 | 150 | 54.3 |

| Total | — | 149.99 | — | — | — | 381.5 |

Note: Genome size of T. bimaculatus used to calculate sequencing coverage were 393.15 Mbp, which is estimated by genome survey.

For the preparation of the single-molecule real-time (SMRT) DNA template, the HMW gDNA was sheared into large fragments (10 K bp on average) by ultrasonication and then end-repaired according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Pacific Biosciences). The blunt hairpins and sequencing adaptor were ligated to the DNA fragments, DNA sequencing polymerases were bound to the SMRTbell templates. Finally, the library was quantified using a Qubit 4 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, USA). After sequencing with the PacBio SEQUEL platform at Novogene (Tianjin), a total of 3.86 Million (~28.97 Gb) long reads were generated and used for the following genome assembly. The average and N50 length of the subreads sequences were 7,505 bp and 12,513 bp, respectively. According to the genome survey, the genome size of T. bimaculatus was estimated to be 393.15 Mb; therefore, the average sequencing coverage was 73.69× (Table 1).

For Hi-C sequencing, the Mbol restriction enzyme was used to digest the HMW gDNA after fixing the conformation of HMW gDNA by formaldehyde, after which the 5′ overhangs were repaired with biotinylated residues. The isolated DNA was reverse-crosslinked, purified and filtered for biotin-containing fragments after blunt-end ligation in situ. Thereafter, the DNA was sheared into fragments by ultrasonication and subsequently repaired by T4 DNA polymerase, T4 polynucleotide kinase and Klenow DNA polymerase. Then, dATP was attached to the 3′ ends of the end-repaired DNA, and 300–500 bp fragments were retrieved by Caliper LabChip Xte (PerkinElmer, USA). The DNA concentration was quantified by a Qubit 4 Fluorometer, and the Illumina Paired-End adapters were ligated to the DNA by T4 DNA Ligase. The 12-cycle PCR products were purified by AMPureXP beads. Finally, sequencing of the Hi-C library was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform and yielded a total of 128.64 Gb paired-end raw reads, with an average sequencing coverage of 117.80X (Table 1).

The cDNA library was prepared following the protocols of the Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and quantitated with KAPA Library Quantification Kits. Then, sequencing of RNA-seq was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform with a 150 bp paired-end strategy. Finally, we generated 21.35 Gb paired-end raw reads and 20.95 Gb paired-end clean reads for gene structure annotation (Table 1).

de novo assembly of the T. bimaculatus genome

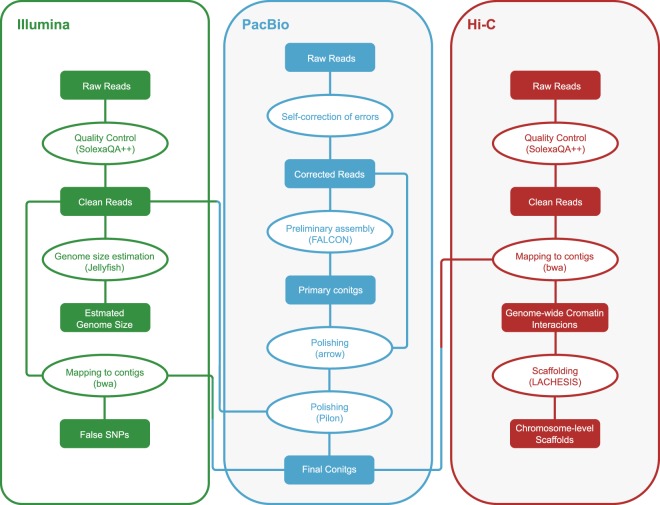

Reads from the three types of libraries were used in different assembly stages separately (Fig. 1). Illumina sequencing data, PacBio sequencing and Hi-C reads were used for the genome survey, contig assembly and chromosome-level scaffolding, respectively.

Fig. 1.

The genome assembly pipeline.

In the genome survey, paired reads with “N” sites exceeding 8 or low-quality (Q < 5) bases exceeding 60 were filtered out from the Illumina library. The pair reads containing the Illumina adaptor sequence were also filtered. Using Jellyfish7, the frequency of 17-mers in the Illumina clean data was calculated with a 1 bp sliding window using the established method8 and obeyed the theoretical Poisson distribution (Fig. S2). Finally, the proportion of heterozygosity in the T. bimaculatus genome was evaluated as 0.55%, and the genome size was estimated as 393.15 Mb, with a repeat content of 25.29% (Table S2).

Long reads generated from the PacBio SEQUEL platform were subsequently processed by a self-correction of errors using FALCON9. Based on the Overlap-Layout-Consensus algorithm, we detected overlaps from input reads and assembled the final String Graph10. Subsequently, we used the FALCON-unzip pipeline to generate phased contig sequences for further calling highly accurate consensus sequences using variantCaller in the GenomicConsensus package, which was employed as an arrow algorithm, and contigs were polished using Illumina reads by Pilon11. Finally, we obtained the assembled genome of T. bimaculatus, which contained including 2,193 contigs with a total length and contig N50 length of 404.21 Mb and 1.31 Mb, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistics of the genome assembly of T. bimaculatus.

| length | Number | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contig (bp) | Scaffold (bp) | Contig | Scaffold | |

| Total | 404,208,938 | 404,312,138 | 2,193 | 1,161 |

| Max | 8,128,173 | 28,865,866 | — | — |

| Number >= 2000 | — | — | 2,143 | 1.111 |

| N50 | 1.312,995 | 16,785,490 | 82 | 11 |

| N60 | 951,152 | 16,217,719 | 117 | 13 |

| N70 | 563,057 | 15,683,578 | 173 | 16 |

| N80 | 220,884 | 13,896,868 | 292 | 19 |

| N90 | 68,784 | 10,376,233 | 627 | 22 |

For chromosome-level scaffolding, we first filtered Hi-C reads with the same protocol as Illumina reads. Subsequently, we mapped the Hi-C clean reads to the de novo assembled contigs by using BWA12 (version 0.7.17) with the default parameters. We removed the reads that did not map within 500 bp of a restriction enzyme site. Using LACHESIS13 (version 2e27abb), we assembled chromosome-level scaffolding based on the genomic proximity signal in the Hi-C data sets. In this stage, all parameters were default except for CLUSTER_N, ORDER_MIN_N_RES_IN_SHREDS and CLUSTER_MIN_RE_SITES, which set as 22, 10 and 80, respectively. As a result, we generated 22 chromosome-level scaffolds containing 1,242 contigs (56.63% of all contigs) with a total length of 371.68 Mb (91.95% of the total length of all contigs), and the lengths of chromosomes ranged from 10.38 Mb to 28.86 Mb (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of assembled 22 chromosomes of T. bimaculatus.

| Chromosomes | Length (Mbp) | Number of Contigs |

|---|---|---|

| Chr1 | 28,856,866 | 68 |

| Chr2 | 20,901,650 | 55 |

| Chr3 | 20,839,560 | 60 |

| Chr4 | 19,082,936 | 61 |

| Chr5 | 18,556,983 | 59 |

| Chr6 | 17,762,956 | 51 |

| Chr7 | 17,385,507 | 47 |

| Chr8 | 17,095,808 | 54 |

| Chr9 | 17,068,765 | 55 |

| Chr10 | 16,786,025 | 53 |

| Chr11 | 16,785,490 | 54 |

| Chr12 | 16,284,555 | 50 |

| Chr13 | 16,217,719 | 54 |

| Chr14 | 16,120,980 | 47 |

| Chr15 | 16,059,269 | 50 |

| Chr16 | 15,683,578 | 65 |

| Chr17 | 14,840,516 | 62 |

| Chr18 | 14,847,795 | 52 |

| Chr19 | 13,896,868 | 51 |

| Chr20 | 13,487,414 | 56 |

| Chr21 | 12,729,218 | 46 |

| Chr22 | 10,376,233 | 40 |

| Linked Total | 371,675,691 | 1,242 |

| Unlinked Total | 32,532,707 | 951 |

| Linked Percent | 91.95% | 56.63% |

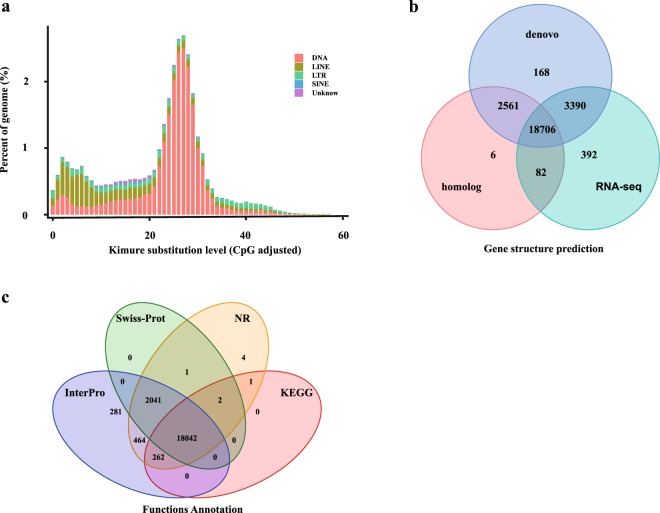

Repeat sequences and gene annotation

We identified repeat sequences in the T. bimaculatus genome with a combination of homology-based and de novo approaches using previously established protocol14. For the homology-based approach, we used Tandem Repeats Finder15 (version 4.04) to detect tandem repeats and used RepeatModeler16 (version 3.2.9), LTR_FINDER17 (version 1.0.2) and RepeatScout18 (version 1.0.2) synchronously to detect repeat sequences in the T. bimaculatus genome. Combined with Repbase19 (Release 19.06), a repeat sequence library was constructed with these results using USEARCH20 (version 10.0.240). Then, we used RepeatMasker16 (version 3.2.9) to annotate repeat elements based on this library. In another approach, we utilized Repbase19 and a Perl script included in the RepeatProteinMasker (submodule in Repeatmasker) program with default parameters to detect TE proteins in the T. bimaculatus genome. Finally, after removing redundancies, we combined all the results generated by these methods, and a total of 109.92 Mb (27.2% in the T. bimaculatus genome) sequences were identified as repeat elements (Table 4). Among these repeat elements, long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) were the main type, accounting for 12.31% (49.76 Mb). In addition, regarding other repeat elements, there were 24.46 Mb (6.05%) of DNA transposons, 1.19 Mb (0.29%) of short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs) and 31.55 Mb (7.8%) of long terminal repeats (LTRs) (Figs 2a and 3a Table 4).

Table 4.

Classification of repeat elements and ncRNAs in T. bimaculatus genome.

| Repeat type | Denove + Repbase Length (bp) | TE protein Length (bp) | Combined TEs length (bp) | Proportion in Genome (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | 21,029,049 | 3,437,660 | 24,459,756 | 6.05 | |

| LINE | 37,262,756 | 12,547,875 | 49,755,614 | 12.31 | |

| SINE | 1,189,529 | 0 | 1,189,529 | 0.29 | |

| LTR | 25,586,059 | 5,992,977 | 31,547,035 | 7.80 | |

| Simple Repeat | 8,473,364 | 0 | 8,473,364 | 2.10 | |

| Unknow | 4,719,800 | 0 | 4,719,800 | 1.17 | |

| Total | 88,122,922 | 21,916,443 | 109,924,780 | 27.20 | |

| ncRNA type | Copy | Average Length (bp) | Total Length (bp) | Propration in Genome (%) | |

| miRNA | 1666 | 91.11 | 151786 | 0.037551 | |

| tRNA | 753 | 75.20 | 56629 | 0.01401 | |

| rRNA | 18S | 464 | 113.37 | 52604 | 0.013014 |

| 28S | 1 | 121 | 121 | 0.00003 | |

| 5.8S | 9 | 142.78 | 1,285 | 0.000318 | |

| 5S | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 454 | 112.77 | 51,198 | 0.012666 | |

| sRNA | CD-box | 588 | 141.15 | 82,996 | 0.020533 |

| HACA-box | 84 | 92.52 | 7,772 | 0.001923 | |

| Splicing | 77 | 162.88 | 12,542 | 0.003103 | |

| Subtotal | 413 | 144.85 | 59,821 | 0.0148 | |

Note: “Denovo” represented the de novo identified transposable elements using RepeatMasker, RepeatModeler, RepeatScout, and LTR_FINDER. “TE protein” meant the homologous of transposable elements in Repbase identified with RepeatProteinMask. While “Combined TEs” referred to the combined result of transposable elements identified in the two ways. “Unknown” represented transposable elements could not be classified by RepeatMasker.

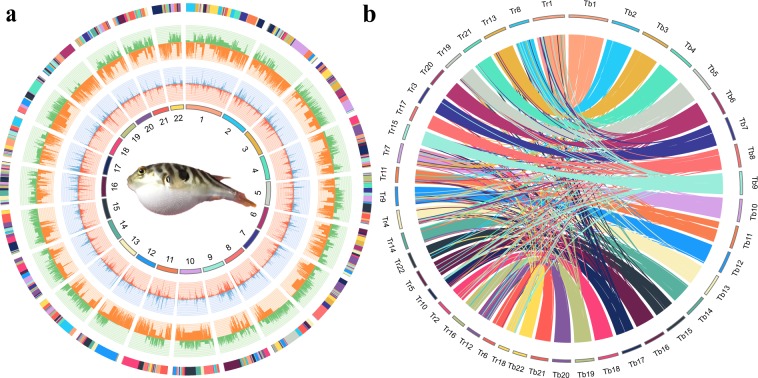

Fig. 2.

Circos plot of the reference genome of T. bimaculatus and syntenic relationship with the T. rubripes genome. (a) Circos plot of 22 chromosomes and the annotated genes, ncRNAs and transposable elements of T. bimaculatus. The tracks from inside to outside are 22 chromosome-level scaffolds, the positive-strand gene abundance (red), negative-strand gene abundance (blue), positive-strand TE abundance (orange), negative-strand TE abundance (green), ncRNA abundance of both strands, and contigs that comprised the scaffolds (adjacent contigs on a scaffold are shown in different colours). (b) Circos diagram between T. bimaculatus and T. rubripes. Each coloured arc represents a 1 Kb fragment match between two species. We re-ordered the chromosome numbers of T. rubripes for better illustration.

Fig. 3.

Gene and repetitive element annotations of the T. bimaculatus genome. (a) Divergence distribution of TEs in the T. bimaculatus genome (b) Venn diagram of the number of genes with structure prediction based on different strategies. (c) Venn diagram of the number of functionally annotated genes based on different public databases.

For gene structure prediction, we used both homology-based and de novo strategies to predict genes in the T. bimaculatus genome. For homology-based prediction, we mapped the protein sequences of Oryzias latipes21, Gasterosteus aculeatus22, Tetraodon nigroviridis23, Takifugu rubripes24 and Oreochromis niloticus25 onto the generated assembly using BLAT26 (version 35) with an e-value ≤ 1e-5. Then, we used GeneWise27 (version 2.2.0) to align the homologous in the T. bimaculatus genome against the other five teleosts for gene structure prediction. In the de novo approach, we used several software packages, including Augustus28 (version 2.5.5), GlimmerHMM29 (version 3.0.1), SNAP30 (version 1.0), Geneid31 (version 1.4.4) and GenScan32 (version 1.0). In addition, we also used RNA-seq data (NCBI accession number: SRX5099972) to predict the structure of transcribed genes using TopHat33 (version 1.2) and Cufflinks34 (version 2.2.1). Using EvidenceModeler35 (version 1.1.0), we combined the set of predicted genes generated from the three approaches into a non-redundant gene set and then used PASA36(version 2.0.2) to annotate the gene structures. Finally, a total of 21,117 protein-coding genes were predicted and annotated, with an average exon number of 9.71 and an average CDS length of 1573.89 bp in each gene(Fig. 3b and Table 5). For the annotation of candidate non-coding RNA (ncRNA), we used BLASTN37 to align the T. bimaculatus genome against the Rfam database38 (version 12.0). As a result, we annotated 1,666 miRNA, 753 tRNA, 928 rRNA and 1162 snRNA genes (Fig. 2a and Table 4).

Table 5.

Gene structure and function annotation in T. bimaculatus genome.

| Gene structure Annotation | |

| Number of protein-coding gene | 21,117 |

| Number of unannotated gene | 19 |

| Average transcript length (bp) | 7,914.81 |

| Average exons per gene | 9.71 |

| Average exon length (bp) | 162.13 |

| Average CDS length (bp) | 1,573.89 |

| Average intron length (bp) | 728.2 |

| Gene function Annotation | |

| Number (Percent) | |

| Swissprot | 20,086 (95.10%) |

| Nr | 20,817 (98.60%) |

| KEGG | 18,307 (86.70%) |

| InterPro | 21,090 (99.90%) |

| GO | 19,934 (94.40%) |

| Pfam | 18,050 (85.50%) |

| Annotated | 21,098 (99.90%) |

| Unannotated | 19 (0.10%) |

For gene function annotation, we used BLASTP to align the candidate sequences to the NCBI and Swissport protein databases with E values < 1 × 10−5. Then, we performed the functional classification of GO categories with the InterProScan program39 (version 5.26) and used KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS)40 to conduct the KEGG pathway annotation analysis. A total of 21,098 genes were successfully annotated, accounting for 99.9% of all predicted genes (Figs 2a, 3c and Table 5).

Data Records

The raw sequencing reads of all libraries are available from NCBI via the accession numbers SRR8285219- SRR828522741. The assembled genome and sequence annotations are available in NCBI with the accession number SWLE00000000 via the project PRJNA50853742.

Technical Validation

Evaluating the completeness of the genome assembly and annotation

The final assembly contains 404.41 Mb with a scaffold N50 size of 16.79 Mb (Table 2). Assembly completeness and accuracy were evaluated by multiple methods. First, reads from the short-insert library were re-mapped onto the assembled genome using BWA12 (version 0.7.17). A total of 96.97% of the reads mapped to a reference sequence in the genome (98.71% coverage), demonstrating a high assembly accuracy (Table S3). We used Genome Analysis Toolkit43 (GATK) (version 4.0.2.1) to identify a total of 1,115.45 SNPs throughout the whole genome, including 1,110.69 K heterozygous SNPs and 4,765 homozygous SNPs (Table S4). In addition, the accuracy of the assembly was verified by the extremely low proportion of homozygous SNPs (1.22 × 10−5%) (Table S4).

Assembly completeness was evaluated using Core Eukaryotic Genes Mapping Approach (CEGMA) software44 (version 2.3), and a total of 235 core Eukaryotic Genes (CEGs) from the complete set of 248 CEGs (94.67%) were identified in the assembled genome, suggesting the draft genome of T. bimaculatus was high complete (Table S4). Finally, Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologues (BUSCO) software45 (version 1.22) was used to evaluate the completeness of the assembly with the actinopterygii_odb9 database. A total of 4,254 out of the 4,584 searched BUSCO groups (92.8%) had been completely assembled in our draft genome, suggesting a high level of completeness of the de novo assembly (Table S3).

To verify the accuracy of the contig arrangement in 22 chromosomes, we aligned 7,443 (count) 1 K bp small fragments with 50 K bp spacing as anchors of the assembled genome against the published T. rubripes genome (FUGU5)24,46 to compare consistency between these two genomes. The 22 chromosomes we identified in the T. bimaculatus genome aligned exactly against the chromosomes of the T. rubripes, suggesting high continuity with the T. rubripes genome (Fig. 2b).

The predicted gene models we used were integrated by EvidenceModeler, and a total of 18,706 genes were predicted by all three gene structure prediction strategies, which representing 88.58% of the 21,117 predicted genes (Fig. 3b). Notably, this validation procedure is limited by the gene expression in the mixture of tissues used for RNA-Seq. Therefore, considering that transcriptomic data derived from different tissues will cover distinct sets of expressed genes, it is conceivable that more genes could be validated.

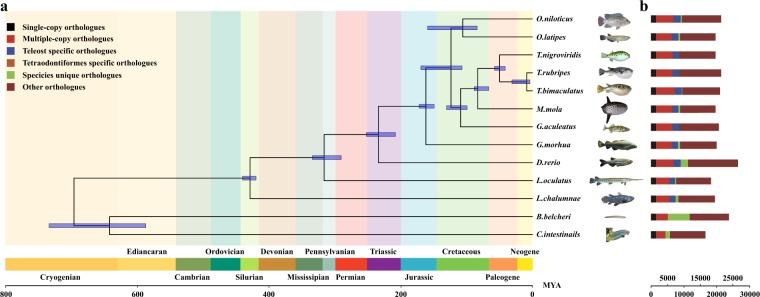

Gene family identification and phylogenetic analysis of T. bimaculatus

To identify gene families among T. bimaculatus and other species, we download the protein sequence of Branchiostoma belcheri47(outgroup), Ciona intestinalis48 (outgroup), Danio rerio49, Gadus morhua50, Gasterosteus aculeatus22, Latimeria chalumnae51, Lepisoteus oculatus52, Mola mola53, Oryzias latipes21, Oreochromis niloticus25, Takifugu rubripes24 and Tetraodon nigroviridis23. We removed those protein sequences shorter than 30 amino acids in the proteome set of the above thirteen species and used OrthoMCL54 to construct gene families. A total of 20,741 OrthoMCL families were built using the previously all-to-all BLASTP strategy55.

To reveal the phylogenetic relationships among T. bimaculatus and other species, we identified 1,479 single copy ortholog families from the 13 species (as described above) (Table S5) and aligned the protein sequences of these 1,497 orthologues using MUSCLE (version 3.8.31)56. Then we used Gblocks57 to extract the well-aligned regions of each gene family alignment and converted protein alignments to the corresponding coding DNA sequence alignments using an in-house script. For each species, we combined all translated coding DNA sequences to a “supergene”. Finally, we used RAxML (version 8.2.12)58 with 500 bootstrap replicates to generate trees. Using molecular clock data from the TimeTree database59, MCMCTREE (PAML package)60 were employed to estimate the divergence time based on the approximate likelihood calculation method. The phylogenetic relationships among the other fish species were consistent with several previous studies8,14,61. Based on the phylogenetic analysis, we inferred that T. bimaculatus speciated approximately 9.1 million years ago from the common ancestor of Takifugu (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Divergence times and distribution of different types of orthologues in representative species. (a)Estimated divergence times of representative species based on the phylogenomic analysis. The blue bars in the ancestral nodes indicate the 95% confidence intervals of the estimated divergence time (MYA, million years). Different background colours represent the corresponding geological age. (b) Distribution of different types of orthologues in the selected representative species.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the Innovation and Industrialization Project of Takifugu breeding Industry (No. 2017FJSCZY03), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Nos 20720180123 & 20720160110), the State Key Laboratory of Large Yellow Croaker Breeding (Fujian Fuding Seagull Fishing Food Co., Ltd) (Nos LYC2017ZY01 & LYC2017RS05).

Author Contributions

P.X. conceived and supervised the study. B.L., L.L. and H.B. collected the sample. Z.Z. and B.C. extracted the genomic DNA and performed the bioinformatics analysis. Z.Z. and Y.S. drafted the manuscript. F.P. helped with the manuscript preparation. P.X. revised the manuscript.

Code Availability

The versions, settings and parameters of the software used in this work are as follows:

Genome assembly:

(1) Falcon: version 1.8.2; all parameters were set as default; (2) Quiver: version: 2.1.0; parameters: all parameters were set as default; (3) pilon: version:1.22; all parameters were set as default; (4) LACHESIS: parameters: RE_SITE_SEQ = AAGCTT, USE_REFERENCE = 0, DO_CLUSTERING = 1, DO_ORDERING = 1, DO_REPORTING = 1, CLUSTER_N = 24, CLUSTER_MIN_RE_SITES = 300, CLUSTER_MAX_LINK_DENSITY = 4, CLUSTER_NONINFORMATIVE_RATIO = 10, REPORT_EXCLUDED_GROUPS = −1;

Genome annotation:

(1) RepeatProteinMask: parameters: -noLowSimple -pvalue 0.0001 -engine wublast. (2) RepeatMasker: version: open-4.0.7; parameters: -a -nolow -no_is -norna -parallel 1. (3) LTR_FINDER: version:1.05; parameters: -C -w 2. (4) RepeatModeler: version: open-1.0.10; parameters:-database genome -engine ncbi -pa 15. (5) RepeatScout: version: 1.0.5; parameters: all parameters were set as default. (6) TRF: matching weight = 2, mismatching penalty = 7, INDEL penalty = 7, match probability = 80, INDEL probability = 10, minimum alignment score to report = 50, maximum period size to report = 2000, -d –h. (7) Augustus: version:3.1.2; parameters:–extrinsicCfgFile–uniqueGeneId = true–noInFrameStop = true–gff3 = on–genemodel = complete–strand = both. (8) GlimmerHMM: version:3.0.3; parameters: -f –g. (9) Genscan: -cds. (10) Geneid: version: 1.2; parameters: -P -v -G -p geneid. (11) Genewise: version: 2.4.0; parameters: -trev -genesf -gff –sum. (12) BLAST: version 2.7.1; parameters: -p tblastn -e 1e-05 -F T -m 8 -d. (13) EVidenceModeler: version: 1.1.1; parameters: G genome.fa -g denovo.gff3 –w weight_file -e transcript.gff3 -p protein.gff3–min_intron_length 20. (14) PASA: version: 2.3.3; parameters: all parameters were set as default.

Gene family identification and phylogenetic analysis:

(1) Blastp: parameters: -e 1e-7 -outfmt 6. (2) Orthomcl: parameters: all parameters were set as default. (3) MUSCLE: version 3.8.31; parameters: all parameters were set as default. (4) Gblocks: version: 0.91b; parameters: all parameters were set as default. (5) RAxML: version: 8.2.12; parameters: -n sp -m PROTGAMMAAUTO -T 20 -f a. (6) MCMCTREE: parameters: all parameters were set as default.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41597-019-0195-2.

References

- 1.Aparicio S, et al. Whole-genome shotgun assembly and analysis of the genome of Fugu rubripes. Science. 2002;297:1301–1310. doi: 10.1126/science.1072104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Q-L, Zhang H-T, Ren Y-Q, Zhou Q. Comparison of growth parameters of tiger puffer Takifugu rubripes from two culture systems in China. Aquaculture. 2016;453:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.11.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baohua Chen, Z. Z. et al. The sequence and de novo assembly of the Larimichthys crocea genome using PacBio and Hi-C technologies. Scientific Data, 10.1038/s41597-019-0194-3 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Peng W, et al. An ultra-high density linkage map and QTL mapping for sex and growth-related traits of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) Scientific reports. 2016;6:26693. doi: 10.1038/srep26693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Baohua, Xu Jian, Cui Jun, Pu Fei, Peng Wenzhu, Chen Lin, Xu Peng. Transcriptional differences provide insight into environmental acclimatization in wild amur ide (Leuciscus waleckii) during spawning migration from alkalized lake to freshwater river. Genomics. 2019;111(3):267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox, M. P., Peterson, D. A. & Biggs, P. J. SolexaQA: At-a-glance quality assessment of Illumina second-generation sequencing data. Bmc Bioinformatics11, 10.1186/1471-2105-11-485 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Marcais G, Kingsford C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:764–770. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu P, et al. Genome sequence and genetic diversity of the common carp, Cyprinus carpio. Nature genetics. 2014;46:1212–1219. doi: 10.1038/ng.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pendleton M, et al. Assembly and diploid architecture of an individual human genome via single-molecule technologies. Nature methods. 2015;12:780–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myers EW. The fragment assembly string graph. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl 2):ii79–85. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker BJ, et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PloS one. 2014;9:e112963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korbel JO, Lee C. Genome assembly and haplotyping with Hi-C. Nature biotechnology. 2013;31:1099–1101. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu J, et al. Genomic Basis of Adaptive Evolution: The Survival of Amur Ide (Leuciscus waleckii) in an Extremely Alkaline Environment. Molecular biology and evolution. 2017;34:145–159. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic acids research. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Current protocols in bioinformatics Chapter 4(Unit 4), 10, 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Xu Z, Wang H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic acids research. 2007;35:W265–268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price AL, Jones NC, Pevzner PA. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl 1):i351–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bao W, Kojima KK, Kohany O. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mobile. DNA. 2015;6:11. doi: 10.1186/s13100-015-0041-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.2018. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA401159

- 22.2006. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA13579

- 23.2010. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA12350

- 24.2018. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA1434

- 25.2016. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA59571

- 26.Kent WJ. BLAT–the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome research. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birney E, Clamp M, Durbin R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome research. 2004;14:988–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.1865504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanke M, Morgenstern B. AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene prediction in eukaryotes that allows user-defined constraints. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33:W465–W467. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majoros WH, Pertea M, Salzberg SL. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2878–2879. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korf I. Gene finding in novel genomes. Bmc Bioinformatics. 2004;5:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parra G, Blanco E, Guigo R. GeneID in Drosophila. Genome research. 2000;10:511–515. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.4.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burge C, Karlin S. Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. Journal of molecular biology. 1997;268:78–94. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trapnell C, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature biotechnology. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haas Brian J, Salzberg Steven L, Zhu Wei, Pertea Mihaela, Allen Jonathan E, Orvis Joshua, White Owen, Buell C Robin, Wortman Jennifer R. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biology. 2008;9(1):R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haas BJ, et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic acids research. 2003;31:5654–5666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Camacho C, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. Bmc Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nawrocki EP, et al. Rfam 12.0: updates to the RNA families database. Nucleic acids research. 2015;43:D130–137. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones P, et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic acids research. 2007;35:W182–185. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP172717

- 42.Xu PEA. 2019. Takifugu bimaculatus isolate TB-2018, whole genome shotgun sequencing project, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. GenBank. SWLE00000000

- 43.McKenna A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome research. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1061–1067. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simao FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kai W, et al. Integration of the Genetic Map and Genome Assembly of Fugu Facilitates Insights into Distinct Features of Genome Evolution in Teleosts and Mammals. Genome Biol Evol. 2011;3:424–442. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang SEA. 2016. Branchiostoma belcheri breed outbred isolate BF01, whole genome shotgun sequencing project, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. Genbank. AYSR01000000

- 48.2014. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJDA65419

- 49.2018. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA11776

- 50.2011. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA41391

- 51.2012. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA56111

- 52.2016. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA68247

- 53.2018. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA305960

- 54.Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Jr., Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome research. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu J, et al. Draft genome of the Northern snakehead, Channa argus. GigaScience. 2017;6:1–5. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic acids research. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Talavera G, Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Systematic biology. 2007;56:564–577. doi: 10.1080/10635150701472164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hedges SB, Dudley J, Kumar S. TimeTree: a public knowledge-base of divergence times among organisms. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2971–2972. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang Z. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Computer applications in the biosciences: CABIOS. 1997;13:555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pan H, et al. The genome of the largest bony fish, ocean sunfish (Mola mola), provides insights into its fast growth rate. GigaScience. 2016;5:36. doi: 10.1186/s13742-016-0144-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- 2018. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA401159

- 2006. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA13579

- 2010. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA12350

- 2018. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA1434

- 2016. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA59571

- 2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP172717

- Xu PEA. 2019. Takifugu bimaculatus isolate TB-2018, whole genome shotgun sequencing project, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. GenBank. SWLE00000000

- Huang SEA. 2016. Branchiostoma belcheri breed outbred isolate BF01, whole genome shotgun sequencing project, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. Genbank. AYSR01000000

- 2014. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJDA65419

- 2018. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA11776

- 2011. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA41391

- 2012. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA56111

- 2016. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA68247

- 2018. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA305960

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The versions, settings and parameters of the software used in this work are as follows:

Genome assembly:

(1) Falcon: version 1.8.2; all parameters were set as default; (2) Quiver: version: 2.1.0; parameters: all parameters were set as default; (3) pilon: version:1.22; all parameters were set as default; (4) LACHESIS: parameters: RE_SITE_SEQ = AAGCTT, USE_REFERENCE = 0, DO_CLUSTERING = 1, DO_ORDERING = 1, DO_REPORTING = 1, CLUSTER_N = 24, CLUSTER_MIN_RE_SITES = 300, CLUSTER_MAX_LINK_DENSITY = 4, CLUSTER_NONINFORMATIVE_RATIO = 10, REPORT_EXCLUDED_GROUPS = −1;

Genome annotation:

(1) RepeatProteinMask: parameters: -noLowSimple -pvalue 0.0001 -engine wublast. (2) RepeatMasker: version: open-4.0.7; parameters: -a -nolow -no_is -norna -parallel 1. (3) LTR_FINDER: version:1.05; parameters: -C -w 2. (4) RepeatModeler: version: open-1.0.10; parameters:-database genome -engine ncbi -pa 15. (5) RepeatScout: version: 1.0.5; parameters: all parameters were set as default. (6) TRF: matching weight = 2, mismatching penalty = 7, INDEL penalty = 7, match probability = 80, INDEL probability = 10, minimum alignment score to report = 50, maximum period size to report = 2000, -d –h. (7) Augustus: version:3.1.2; parameters:–extrinsicCfgFile–uniqueGeneId = true–noInFrameStop = true–gff3 = on–genemodel = complete–strand = both. (8) GlimmerHMM: version:3.0.3; parameters: -f –g. (9) Genscan: -cds. (10) Geneid: version: 1.2; parameters: -P -v -G -p geneid. (11) Genewise: version: 2.4.0; parameters: -trev -genesf -gff –sum. (12) BLAST: version 2.7.1; parameters: -p tblastn -e 1e-05 -F T -m 8 -d. (13) EVidenceModeler: version: 1.1.1; parameters: G genome.fa -g denovo.gff3 –w weight_file -e transcript.gff3 -p protein.gff3–min_intron_length 20. (14) PASA: version: 2.3.3; parameters: all parameters were set as default.

Gene family identification and phylogenetic analysis:

(1) Blastp: parameters: -e 1e-7 -outfmt 6. (2) Orthomcl: parameters: all parameters were set as default. (3) MUSCLE: version 3.8.31; parameters: all parameters were set as default. (4) Gblocks: version: 0.91b; parameters: all parameters were set as default. (5) RAxML: version: 8.2.12; parameters: -n sp -m PROTGAMMAAUTO -T 20 -f a. (6) MCMCTREE: parameters: all parameters were set as default.