Abstract

Dormancy-associated MADS-box (DAM) genes play an important role in plant dormancy and release phases. Little is known about the dormancy characteristics of Jerusalem artichoke tubers. Using bioinformatics, we identified and annotated 23 MADS-box gene sequences from the genome of the Jerusalem artichoke and we analyzed the differential expression of these genes at different developmental stages of tuber dormancy. The results show that all 23 genes encode basic proteins and most of the genes of the same subgroup have similar pI values. MADS-box genes from the Jerusalem artichoke and from other closely related species were divided into ten categories using phylogenetic analysis software. Based on the amino acid sequence of the MADS-domain proteins, ten highly conserved motifs were identified. Gene ontology annotation, InterProScan protein function prediction, and RT-PCR analysis showed that ten MADS-box genes play important roles in the dormancy process of Jerusalem artichoke tubers. Our work lays a foundation for further study of the role of MADS-box genes in the dormancy of the Jerusalem artichoke and other tuber crops.

Keywords: Dormancy, MADS-box transcription factors, Gene expression, Helianthus tuberosus L.

Introduction

The MADS-box gene family is characterized by a highly conserved motif found most commonly associated with transcription factors. MADS-box genes were first discovered in animals and then found in yeast and plants (Ma 1994). With the development of high-throughput sequencing technologies, more and more plant MADS-box transcription factor gene families have been discovered and structural and expression characteristics have been analyzed, including 105 from Arabidopsis thaliana (Kofuji et al. 2003), 38 from Vitis vinifera (Díaz-Riquelme et al. 2009), 106 from Glycine maxs (Shu et al. 2013), 85 from Fragaria vesca, 80 from Prunus mumes (Xu et al. 2014), and 46 from Malian domesticas (Kofuji et al. 2003). To date, more than 28,881 MADS-box sequences can be found in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (Lalusin et al. 2006). It is a key gene family regulating many aspects of plant growth and development such as flower development, substance and energy metabolism, signal transmission and transduction, and dormancy processes for plants (Ubi et al. 2010; Ryuta et al. 2011). MADS-box genes also play an important role in the dormancy of flower buds of fruit tree. The expression of dormancy-associated MADS-box (DAM) genes plays an important role in regulating the growth cycle of bud dormancy, especially in the bud dormancy of deciduous fruit trees (Bielenberg et al. 2008). DAM genes differentially expressed during multiple dormancy inductions and release processes have been identified in different kinds of fruit trees such as peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] (Bielenberg et al. 2008; Jiménez et al. 2010; Leida et al. 2010, 2012; Yamane et al. 2011; Li et al. 2009), pear (P. pyrifolia Nakai, (Ubi et al. 2010), plum (Prunus mume Siebold Zucc.; (Saengkanuk et al. 2011; Yamane et al. 2008), and kiwi [Actinidia deliciosa (A. Chev.) CF Liang and AR Ferguson] (Wu et al. 2011). The MADS-box gene family not only plays a regulatory role in plant dormancy, but also greatly impacts flowering time, differentiation of dividing tissues (Weigel 1995), embryonic development (Perry et al. 1999), root formation (Alvarez-Buylla et al. 2000), and seed and fruit development (Gu et al. 1998; Liljegren et al. 1998). However, the relationship between MADS-box genes and bud dormancy of tuber crops has not been reported.

Helianthus tuberosus L. (Jerusalem artichoke) belongs to the composite family (Asteraceae) and the genus is native to North America (Filep et al. 2016). In Europe, it is used as a food source for both humans and livestock (Watson and Renney 1974). The Jerusalem artichoke is one of the most abundant plant sources of inulin and other oligosaccharides (Lachman 2008). Jerusalem artichoke tubers can safely overwinter in the − 30 °C environment of the Qinghai Plateau (China). Winter dormancy not only affects the seedling, but also affects plant growth and tuber differentiation, thereby affecting the yield and quality of the Jerusalem artichoke and directly influencing the production and development in the following year. Dormancy in the Jerusalem artichoke tubers is a very complex biological process. Numerous environmental (Saengthongpinit and Sajjaanantakul 2005), physiological (Li et al. 2017), and genetic factors (Danilcenko et al. 2013) have direct and indirect effects on dormancy and germination of the Jerusalem artichoke during storage. Moreover, the environmental conditions in which the tubers are formed affect the length of the dormant period. High temperatures and dry conditions can shorten dormancy, while low temperatures and humid conditions prolong dormancy (Krijthe 1962). As for the complexity of dormancy regulation, Borgmann et al. described small developing potato tubers in the library and source tubers in storage (Borgmann et al. 1994). They found specific trends in 1072 peptides, of which 296 (28%) were from tubers of the library, 185 (7%) were from tubers of the sources, and 591 (55%) were from proteins shared, among developmental stages. Some specific proteins in the library play a role as developmental proteins and are key enzymes involved in the metabolism of carbohydrates, while proteins in the source influence the plasma membrane (Can et al. 1998). When tubers are used as germplasm resources for cultivation, the dormancy degree affects the emergence time, emergence rate, uniformity, plant growth and yield in the field, and ultimately the overall crop value. The lack of understanding of the mechanism of tuber dormancy hinders the development of protocols for its artificial regulation, which seriously restricts the development of tuber production of the Jerusalem artichoke and the full utilization of tubers as raw materials for industrial processing. Therefore, tuber dormancy studies are of great importance for the cultivation, storage, and retention of freshness of Jerusalem artichokes.

Dormancy is of great biological significance for plant survival and reproduction. Plants propagated by tubers are especially susceptible to low-temperature damage in winter. In this study, based on a transcriptome library of Jerusalem artichoke tubers from ‘Qingyu No.1’, 23 MADS-box gene sequences were identified. Bioinformatics was used to analyze these sequences and their encoded proteins, as well as expression changes among tubers during different dormancy stages. Together, our results reveal the role of ten MADS-box genes in the regulation of dormancy in Jerusalem artichoke tubers and provide a theoretical foundation for the study of molecular regulation of the dormancy in the Jerusalem artichoke.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The tubers of ‘Qingyu No.1’, a plateau variety of Jerusalem artichoke planted in the Horticultural Institute of Qinghai Academy of Agricultural Sciences, were selected as the materials to be tested (E 101°45′08.15″, N 36°43′32.06″). Planting was in accordance with Chinese agricultural planting standards. Starting from October 2017, the Jerusalem artichoke tubers in this study were sampled once a month, with sampling dates of October 3, November 3, and December 3 in 2017 and January 3, February 3, and March 3 in 2018. After liquid nitrogen freezing, the collected tubers were stored in a − 80 °C freezer.

Construction of a transcriptome library from Jerusalem artichoke tubers and Unigene screening

Total RNA of Helianthus tuberosus tubers was extracted with a TRNzol Total RNA Extraction Kit (TRNzol Reagent, DP405; Tiangen Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., China). The purity of the RNA (3 μl) was estimated with a TGem spectrophotometer (OSE-260; Tiangen Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., China). Based on the transcriptome library of Jerusalem artichoke tubers constructed in our laboratory, all MADS-box genes were identified by database alignment and 23 MADS-box genes involved in the dormancy of Jerusalem artichoke were screened.

Database searches and identification of MADS-box family members in Helianthus tuberosus L.

The 23 identified MADS-box genes were subjected to a series of bioinformatics analyses. First, Sequin (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Sequin/index.html) software was used to generate a local information file and to submit the serial number of the screening result to NCBI. Second, the ExPASy proteomics server (http://www.expasy.org/) was used to predict the isoelectric point and molecular weight (MW) of the protein. The number of amino acids in the protein was analyzed using the Sequence Processing Online Toolkit (SMA: bio-soft.net). The MEME Suite program was used to determine all motifs in the protein sequences (Ma 1994). Finally, simple modular architecture research tool (SMART) (Lesur et al. 2015) was used to identify and annotate the structural domains of the MADS-box protein sequences from the Jerusalem artichoke.

Sequence alignment and the construction of a phylogenetic tree

The cDNA sequences of MADS-box genes from Arabidopsis thaliana, potato, peach and other Prunus species were obtained from the NCBI database. These sequences were converted to FASTA format with BioEdit (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/page2.html) and multiple sequence alignment was performed with ClustalX 2.1 (McWilliam et al. 2007). Next, a phylogenetic tree was constructed from the obtained 23 Unigenes of the Jerusalem artichoke to screen for MADS-box genes associated with Jerusalem artichoke tuber dormancy. FASTA sequences were imported into MEGA6.0 (http://www.megasoftware.net/mega6/faq.html) software for phylogenetic tree construction. When sequence alignment was performed, the ClustalW aligned data were used in MEGA and 1000 bootstrap replicates were performed to estimate nodal support obtained from a neighbor-joining tree.

Gene ontology, functional classification, and InterProScan protein function prediction of Unigenes

Functional annotation of Unigene sequences was performed using the Blast2GO v5.2 software under default settings to retrieve the Unigenes related to gene ontology (GO) terms, enzyme code (EC) numbers, and biological pathways (Conesa and Götz 2008). GO annotations were generated through three basic steps: homologues BLAST, GO term mapping, and actual annotation. Annotated sequences were classified according to their GO (biological process, molecular function, and cellular component). Proteins domain annotations were performed with InterProScan web service kindly provided by the EBI. The EC numbers for novel sequences with an e-value less than 1e−5 were obtained.

To rectify the functional annotation of novel sequences eggNOG-mapper, an online service, was used to facilitate functional annotation of novel sequences based on fast orthology assignments using precomputed clusters and phylogenies from the eggNOG database (Huerta-Cepas et al. 2017). All functional annotations available for the retrieved orthologs currently include curated GO terms.

qRT-PCR analyses of MADS-box genes

To analyze the transcription levels of the MADS-box genes during dormancy, real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using Applied Biosystems QuantStudio® 5. A qPCR was performed using a three-step procedure. The melting curve after PCR was used to make primer analysis to confirm the specificity of amplification.

Each sample was analyzed in triplicate using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). qPCR was performed as follows: Pre-denaturation was at 95 °C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles consisting of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 60 °C for 20 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. Fluorescence signals were collected at the 60 °C extension stages to obtain cyclic Ct values of different genes. Reactions (20 μL) contained 10 μL of 2 × SYBRII, 7.8 μL of dd H2O, 0.6 μL of each of the upstream and downstream primers, and 1 μL of the cDNA template (approximately, 100 ng μL−1). The internal reference primers were selected from the 25S ribosomal RNA of Jerusalem artichoke. Forward primer: CTGTCTACTATCCAGCGAAACCA, Reverse primer: AGGGCTCCCACTTATCCTACAC.

Results

Identification and analysis of MADS-box sequences

A total of 23 MADS-box Unigene sequences, screened from the Qingyu No.1 Jerusalem artichoke transcriptome sequence that may be associated with dormancy were identified. These 23 genes were converted into their corresponding amino acid sequences whose length, isoelectric point, and relative molecular mass were calculated (Table 1). The lengths of these proteins vary between 70 and 706 amino acids. The corresponding molecular weights were between 8.06 and 78.97 kDa. Isoelectric analysis showed that all 23 genes encoded basic proteins. These 23 genes were divided into ten subclasses (I–X) according to the results of cluster analysis (Table 1). Most of the genes in the same subclass had similar pI values.

Table 1.

“QingYu No.1” MADS-box transcription factor amino acid basic information

| Gene name | Accession number | Length (bp) | Molecular weight (kDa) | pI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Unigene0035286 | GHBN01034338.1 | 360 | 40.76 | 7.69 |

| Unigene0043019 | GHBN01042025.1 | 458 | 49.32 | 9.18 | |

| II | Unigene0008852 | GHBN01008837.1 | 439 | 48.11 | 9.37 |

| Unigene0040066 | GHBN01039089.1 | 250 | 26.19 | 8.89 | |

| III | Unigene0005624 | GHBN01005617.1 | 706 | 78.97 | 9.56 |

| IV | Unigene0006738 | GHBN01006728.1 | 71 | 8.06 | 11.33 |

| Unigene0021755 | GHBN01020916.1 | 151 | 15.31 | 10.83 | |

| Unigene0022658 | GHBN01021811.1 | 289 | 32.81 | 9.07 | |

| Unigene0002436 | GHBN01002432.1 | 94 | 10.57 | 9.76 | |

| V | Unigene0012855 | GHBN01012832.1 | 256 | 29.77 | 7.62 |

| VI | Unigene0012840 | GHBN01012817.1 | 330 | 35.07 | 8.76 |

| VII | Unigene0008708 | GHBN01008693.1 | 218 | 22.85 | 10.57 |

| Unigene0022391 | GHBN01021546.1 | 86 | 9.81 | 10.05 | |

| Unigene0043018 | GHBN01042024.1 | 328 | 34.58 | 9.91 | |

| Unigene0000980 | GHBN01000977.1 | 148 | 15.58 | 10.79 | |

| VIII | Unigene0054198 | GHBN01053153.1 | 243 | 26.41 | 10.50 |

| IX | Unigene0016921 | GHBN01016254.1 | 96 | 10.54 | 9.19 |

| Unigene0019862 | GHBN01019044.1 | 70 | 7.31 | 8.22 | |

| X | Unigene0016171 | GHBN01015574.1 | 83 | 9.07 | 11.54 |

| Unigene0020251 | GHBN01019428.1 | 216 | 21.77 | 10.83 | |

| Unigene0042318 | GHBN01041326.1 | 317 | 36.13 | 10.04 | |

| Unigene0039488 | GHBN01038513.1 | 136 | 15.56 | 11.93 | |

| Unigene0028834 | GHBN01027934.1 | 248 | 27.94 | 8.72 |

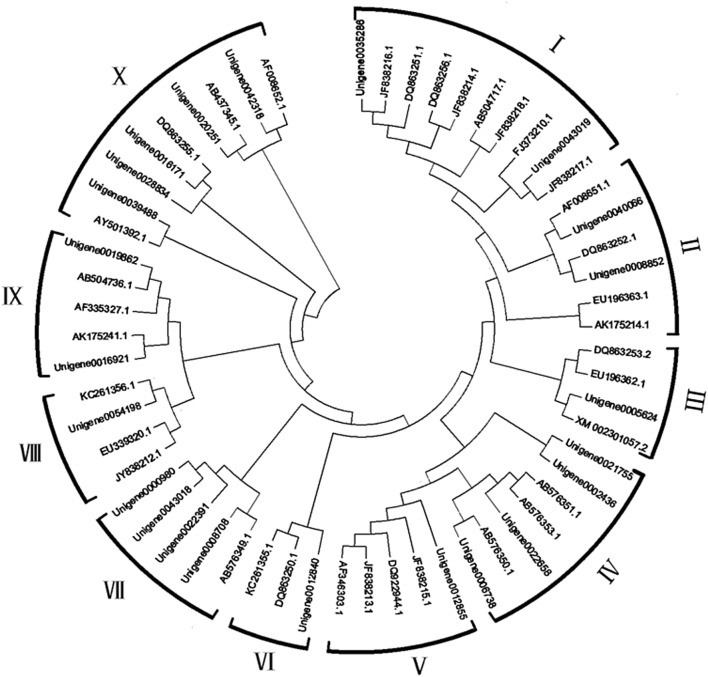

Phylogenetic analysis and classification of the MADS-box gene family

To study the molecular evolution of the MADS-box gene and predict its function, a phylogenetic analysis of some dormancy genes of Jerusalem artichoke, Arabidopsis thaliana, potato, peach, and pear was carried out. Clustal X 2.1 (McWilliam et al. 2007) was used to compare the screened 58 sequences, and neighbor-joining was used to construct a phylogenetic tree in Mega 6.0 (Fig. 1). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that these Unigene sequences clustered with DAM genes in Prunus species, including potato and peach, indicating a close genetic relationship. Based on this phylogenetic tree and on published reports, predicted MADS-box genes were classified into ten categories. Among them, class I was the largest, including ten members and accounting for 17.24% of the total number of genes; class X contained nine members, accounting for 15.52%; class VI was the smallest, including three members and accounting for 5.17%. In class VII, Unigene000980, Unigene0000318, Unigene0202391, and Unigene0008708 were clustered together, suggesting that these four Unigene sequences were less differentiated. Classes II and X contained potato dormant MADS-box genes. In addition, Unigene0040066 was clustered with potato AF008651.1 and Unigene0042318 was clustered with potato-dormant MADS-box gene AF008652.1.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of DAM genes from Jerusalem artichoke, potato, peach and other plums. Based on the phylogenetic tree, predicted MADS-box genes were classified into ten categories. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA 6.0 software by the neighbor-joining method using 1000 bootstrap replicates

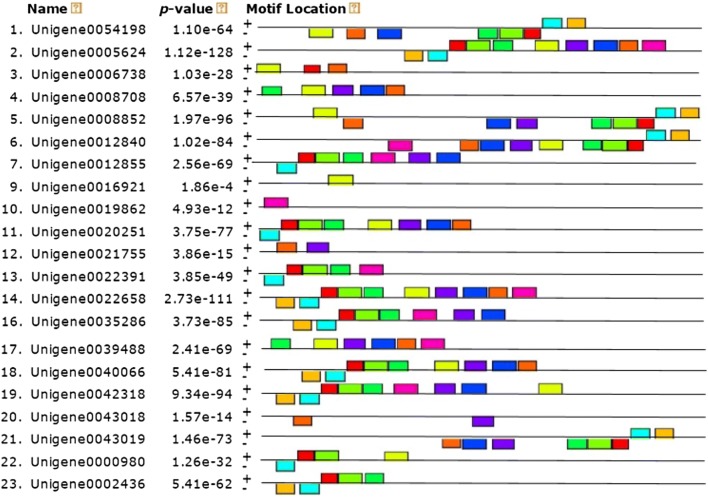

Motif location analysis of MADS-box gene products

Gene structure diversity, as a possible basis for evolution, can provide valuable information about the evolution of multi-gene families (Cao and Shi 2012). MADS-box amino acid sequences of the Jerusalem artichoke were analyzed for conserved motifs using the MEME software. Ten types of conserved motifs were found (Figs. 2, 3). Among them, motif 1 contained 34 amino acids and the highest proportion of identity among all sequences was 65.2%. The well-matched sequence was TNANGAGCTHTCTGTDCTTTGTGATGCTGATGTY. The number of motifs among all genes ranged from 0 to 10. Class IX contained only two Unigenes, each containing only one motif. Proteins encoded by genes that were closely related in the phylogenetic tree contained common amino acid motifs, implying that MADS-box genes in the same subclass have similar functions. Through the localization of motifs of Jerusalem artichoke MADS-box, it was determined that most Unigenes were relatively conserved in all major categories. Because dormancy genes of the Jerusalem artichoke have been under-reported, these ten motifs are mainly motifs of unknown function. Nevertheless, their conserved sequence structure may imply specific biological functions and the sequence and related information for each motif are listed in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

Common motifs of MADS family proteins in Jerusalem artichoke. Ten MADS-box motifs are represented by boxes of different colors. Eight and 15 are Unigene0016171 and Unigene0028834 and do not contain any of the ten common motifs

Fig. 3.

Common motifs in MADS-box. Ten motifs were found by the MEME program

Table 2.

Information of the ten conserved motifs in Jerusalem artichoke MADS-box

| Motif | Length | Conserved amino acid sequences |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 34 | TNANGAGCTHTCTGTDCTTTGTGATGCTGATGTY |

| 2 | 41 | CTTCADCARYCCDYTTCTYCTYTTRGAGAARGTSACYTGYC |

| 3 | 50 | TYGCTBTKATYATCTTCTCHDCYAVWGGMAARCTGTWTGAGTWYKSYAGY |

| 4 | 45 | GRCAMTTDMKBGGKGARGABCTTSRDBSTYTDASTHTYRARGARC |

| 5 | 39 | TRTTMTCWATCCTCYTCAWYTBHAYCTTYCCTCTMCCCA |

| 6 | 41 | KCMAGCATGVWDRARATNCTTGADMGRTATVARMRWYRCWC |

| 7 | 50 | GARMAACAACTYGADRSDRSTCTHANNCRNRTTMGWNCMAVAAAGRMHSA |

| 8 | 50 | SAHGMTHAAMAYRACNHACTSYHBAAGRARDTTRAHGARAWHRRGAARRA |

| 9 | 40 | WBATGCWWGARDMVATBDMDSARCTNCAMVAAAAGGAVMR |

| 10 | 50 | RAKTTGGRMDSWKGARWNKKMHAADVTHAARRCWAVRATYGARGWDCTDS |

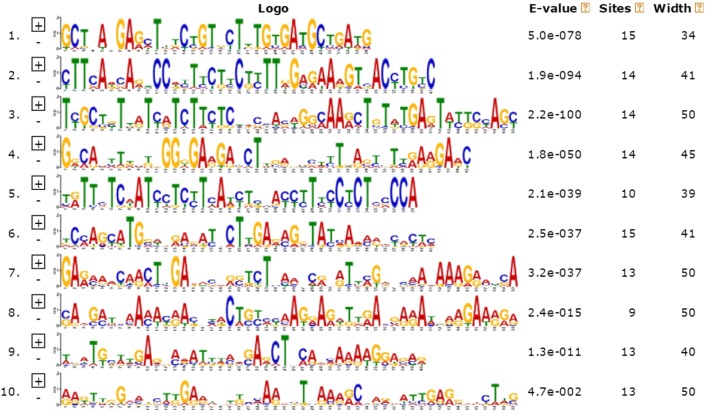

Prediction of protein function

Prediction of protein function was performed by InterProScan on the protein domain and functional locus database. It was found that all Unigene genes, with the exception of Unigene0019864, predicted corresponding functional proteins. Figure 4 shows that there were 16 Unigenes with transcription factor K-box domains. In addition, 14 Unigenes belong to transcription factor MADS-box superfamily, 12 Unigenes contained a transcription factor MADS-box, ten Unigenes contained a MEF2-like MADS domain, and two Unigenes contained a zinc finger motif. The transcription factor K-box domain is the characteristic sequence of the MIKC MADS-box gene and the MEF2-like MADS domain is the most conserved region that is composed of about 56 amino acids at the N terminal of plant type II MADS-box. The MADS-box domain is commonly found associated with the K-box region (Fischer et al. 1995).

Fig. 4.

The functional proteins predicted by MADS-box. Domain. GO annotation enables the function(s) of the family to be attributed to individual domains within the protein. Five functional proteins were predicted by the identified MADS-box

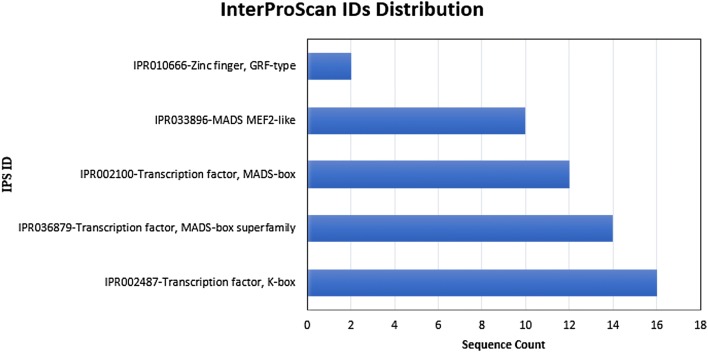

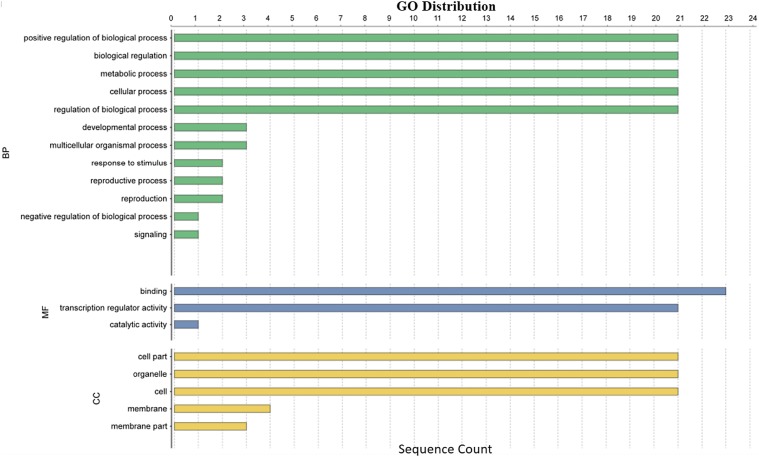

Gene ontology (GO) classification of Unigenes

The GO annotation information of Unigene was obtained by transcriptome sequencing. GO functional classification statistics were made for all Unigenes, of which 23 sequences were annotated (Fig. 5). The 23 Unigenes were annotated into biological processes, molecular functions, or cellular components. Of these, the category of biological process had the largest number of annotated types, up to 12. Twenty-one sequences were annotated into positive regulation of biological processes, biological regulation, metabolic process, and cellular process. In the category of molecular function, 23 sequences were annotated as protein binding, and 21 sequences were annotated into transcription regulator activity. In the category of cellular components, 21 Unigenes were annotated into cell part, organelle, and cell process. Through GO classification, we found that these 21 Unigenes were simultaneously annotated into the biological process, molecular function, and cellular components categories. Only Unigene0016921 and Unigene0028834 were not annotated into the biological process category, but they were both annotated as zinc finger or GRF-type.

Fig. 5.

Jerusalem artichoke Unigene gene GO functional classification histogram. The Unigenes corresponded to three main categories: cellular components, molecular functions, and biological process

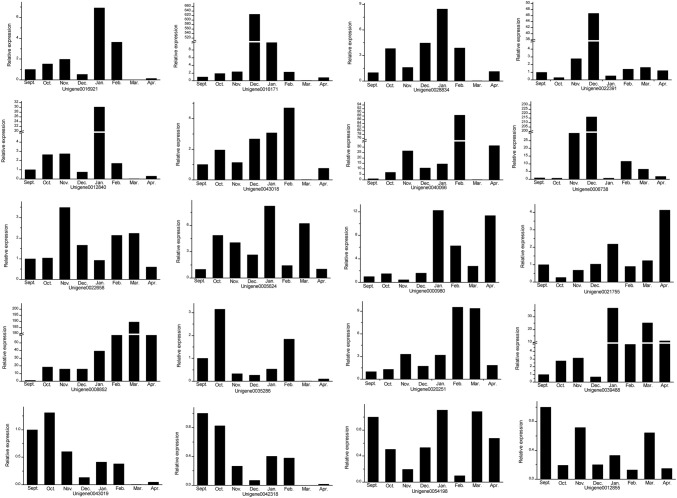

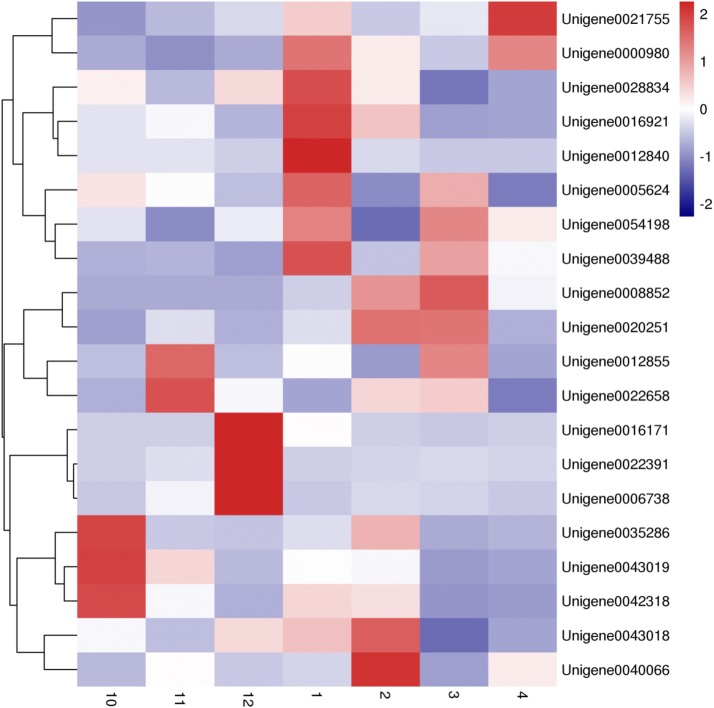

Stage-specific expression analysis of MDAS-box genes during dormancy

To detect the effects of 23 dormant genes associated with Jerusalem artichoke, real-time fluorescence quantification analyses of these genes were performed. We were unable to design primers for Unigene0008708, Unigene0019862, and Unigene0002436, due to their small sizes. The relative expression of each Unigene at different periods is shown in Fig. 6. The expression of each Unigene in September was taken as the control. The results showed that only the expressions of Unigene12855 and Unigene0042318 were lower than that of the control in all periods. Cluster analysis was used to reveal the expression patterns of these different Unigenes during different dormancy periods. According to the clustering results shown in Fig. 7, 20 genes were separated into two categories. The first category included Unigene0021755, Unigene0000980, Unigene0028834, Unigene0016921, Unigene0012840, Unigene0005624, Unigene0054198, and Unigene0039488. The remaining 12 genes were placed into the second largest category. The expression patterns of Unigene0021755 and Unigene0040066 differed the most. All genes, except the Unigene0021755 and Unigene0000980 in the first category, had the highest expression in January, while expression in the other months was relatively low. Expression levels of Unigene0021755 and Unigene0000980 gradually increased from October to February, and then gradually decreased. Unigene0012840 gene was highly expressed only in January, while the expression was suppressed in other months. According to the clustering results, the 12 genes of the second category were divided into three subcategories. Among them, Unigene0008852, Unigene0020251, Unigene0012855, and Unigene0022658 were included in the first subcategory. Unigene0016171, Unigene0022391, and Unigene0006738 were included in the second subcategory, and they had high expression only in December. The remaining five Unigenes were classified into the third category. In the third subcategory, Unigene0035286, Unigene0000319, and Unigene0043318 were most highly expressed in October of the Jerusalem artichoke tuber harvest and inhibited in the remaining months. Unigene0040066 was only expressed in February.

Fig. 6.

Expression patterns of 20 MADS-box genes show time-dependent changes during tuber dormancy in Jerusalem artichoke between September (taken as the control) and April of the following year. The name of the gene or transcript model is shown below each graph. Expression levels obtained by qPCR were calculated relative to the reference gene. Each experiment was performed with three biological replicates. Unigene0008708, Unigene0019862, and Unigene0002436 were too small to be analyzed in this way

Fig. 7.

The expression patterns of the MADS-box genes of the Jerusalem artichoke, showing significant changes over time (red: increased gene expression; blue: inhibited gene expression; numerals at the bottom indicate the months from October to April)

Discussion

Dormancy is a key feature of perennial plants. Meristematic activity ceases and a dormant state is established (Rohde and Bhalerao 2007). DAM genes have been extensively studied in woody crops, but among tuber crops have only been studied in Solanum tuberosum. Horvath et al. found that the StMADS16 gene of Solanum tuberosum has significant similarity with DAM genes of other species (Horvath et al. 2008) and that DAM genes showed differential expression in dormant potato buds (Campbell et al. 2008). The DAM genes of different families and different bud dormancy also display similarities. The differentially expressed StMADS16 gene during potato dormancy also plays a similar role in regulating dormancy in Compositae crops (Horvath 2015). The DAM gene cloned from the Cerasus avium (L.) was shown to play a regulatory role in the dormancy process of Arabidopsis thaliana (Jing et al. 2013). This indicates that some DAM genes have the same function among different species. At present, there is little information about transcription factors regulating the dormancy of the Jerusalem artichoke available. Therefore, this study lays a foundation for further development of the role of MADS-box genes in Jerusalem artichoke dormancy and has reference value for elucidating the function of DAM genes in other tuber crops.

Biological analysis of the 23 MADS-box Unigenes from the Jerusalem artichoke identified in this work revealed that they were all basic proteins, even though their molecular weights were quite different. Therefore, the alkalinity of the protein may be one property of MADS-box associated with dormancy (Leida et al. 2012). Since both the potato and the Jerusalem artichoke are plants that utilize tubers as seeds, biological information on the control of their tuber dormancy genes may be similar. In this way, it is assumed that the Unigene0040066 gene classified in category II with AF008651.1 and the Unigene0042318 gene classified in category X with AF008652.1 are likely to be Jerusalem artichoke-related dormancy genes. We hypothesize that the function of the Jerusalem artichoke MADS-box genes can be predicted by comparison with the function of the corresponding potato dormancy genes, with similar functions to the potato MADS-box genes in categories II and X, respectively. The qPCR results also showed that these two genes played a role during the dormancy of Jerusalem artichoke tubers. The analysis of the MADS-box sequence motif structure showed that Unigene0016171 and Unigene0028834 did not contain any of these ten motifs. Both belong to subclass X and are predicted to contain a zinc finger and GRF-type motif in InterProScan protein prediction, so the specificity of these two Unigene sequences was high. Several genes that are closely related in the phylogenetic tree share common motifs, which indicates that MADS-box genes in the same subclass share similar functions. Through the motif location analysis of the Jerusalem artichoke MADS-box, we determined that most Unigenes were conserved in all categories. Motif 1 contained 34 amino acids and had the highest presence (65.2%) in among all sequences. As there are no previous reports on the dormancy genes of the Jerusalem artichoke, the function of these ten motifs is unknown. Nevertheless, their conserved sequence structure implies that they play important biological roles.

In the MADS-box family, the plant type II MIKC gene contains four domains: the MEF2-like transcription factor (M) domain, the intervening (I) domain, the K-box (K) domain and the carboxyl-terminal (C terminal) domain. The K domain is the characteristic sequence of MIKC MADS-box gene (Kaufmann et al. 2005). InterProScan sequence analysis revealed that 22 out of the 23 Unigenes were annotated, of which 16 Unigenes had the K domain, and that ten Unigenes contained the M domain, including the MIKC gene. The MIKC gene is strongly associated with plant dormancy. It has been extensively studied in perennial woody crops. Absence of the MIKC gene will lead to the failure of plants to enter normal dormancy (Bielenberg et al. 2008). Two genes were annotated to contain growth hormone releasing factor (GRF)-type zinc finger. The GRF transcription factor is an important regulator of plant hormone production, including abscisic acid (ABA) and gibberellins (GA). The important role of these hormones in the dormancy pathway has been supported by transcriptomics and metabolomics. ABA induces plant dormancy, while GA controls plant germination. The balance between these two hormones determines whether plants can germinate normally (Graeber et al. 2012; Bielenberg et al. 2008). We speculate that Unigene0016171 and Unigene0028834 have very important effects on plant hormone regulation and dormancy. Analysis of our GO classification results showed that nine biological processes annotated the same 21 Unigenes, indicating the functional diversity and similarity of MADS-box genes. The three GO classifications of negative regulation of biological process, signaling and catalytic activity only annotated one Unigene, which also indicates the functional differences of a small number of MADS-box Unigene sequences. It may also be related to the small sizes of some Unigene fragments, to the lack of gene annotation information of related databases, and to the existence of unique genes in the Jerusalem artichoke (Xiaoxia et al. 2012).

Relative quantitative results showed that, during the period from September to April of the following year, the expression of Unigene0000980 was relatively high in January and April. The reason for this phenomenon may be that this Unigene plays a certain role during the dormancy period of Jerusalem artichoke in January, and again in April during the period when the temperature rose and the Jerusalem artichoke might break dormancy. This expression pattern is consistent with the results of Chen’s study on genes related to dormancy of peach flower buds (Min et al. 2017). Unigene0012840, Unigene0028834 and Unigene0016921 expressed highest in January, Unigene0016171, Unigene0022391 and Unigene0006738 expressed highest in December, while Unigene0040066 expressed highest in February. Because of the low temperature in the Qinghai Plateau in December, January, and February, most of the Jerusalem artichoke tubers are dormant. It is speculated that these Unigenes play a certain role in the dormancy period of Jerusalem artichoke during storage. Chen et al. found that Prupe.1G276000 and Prupe.7G142500 had higher expression levels only on November 22 (Min et al. 2017), December 5, and December 20. The expression of Pp MADS 1 and Pp MADS2 in ‘Crispy Pear’ (Liu et al. 2012) was similar to that of Pp MADS13-1 and Pp MADS13-2 in ‘Kosui’ (Ubi et al. 2010) except that the latter only had one expression peak on November 15 and December 15, respectively. Unigene0035286 and Unigene0043019 both had the highest expression in October when Jerusalem artichoke tubers were just harvested, while the expression was relatively low in other months. Jerusalem artichoke planted in Qinghai–Tibet Plateau is usually stored at low temperature after harvesting in October. It is speculated that these genes may play a role in the dormancy process of Jerusalem artichoke, which is consistent with the results of Rutherford and Flood, who showed that some invertase activities in Jerusalem artichoke increased at the early stage of tuber dormancy and then decreased later on (Rutherford and Flood 1971).

Therefore, in view of their time-dependent expression levels, ten genes, including Unigene0000980, Unigene0012840, Unigene0016171, Unigene0022391, Unigene0006738, Unigene0040066, Unigene0035286, Unigene0043019, Unigene0028834, and Unigene0016921, may play a role in the dormancy process of Jerusalem artichoke. So far, there are relatively few studies on the genes related to the dormancy of Jerusalem artichoke tubers, and there is still a lack of theoretical basis for deducing the dormancy genes of Jerusalem artichoke based on the results of specific expression. InterproScan analysis revealed that five of the ten genes were not K-box transcription factors, while the other five were annotated as K-box, belonging to the MIKC gene family and regulating the process of plant tuber dormancy (Niu et al. 2016). Unigene0000980 and Unigene0022391 were annotated as MADS-box superfamily. Studies have shown that the MADS-box superfamily plays many key regulatory roles in plants, including embryonic development, fruit maturation, vegetative organ development and flowering time control (Pařenicová et al. 2003). Unigene0028834 and Unigene16921 were annotated as GRF-type zinc fingers. As the GRF-type zinc fingers affects plant dormancy by influencing the dynamic balance between ABA and GA, these two genes also play a certain role in Jerusalem artichoke tuber dormancy.

The Jerusalem artichoke is widely planted in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Its dormancy characteristics and stress resistance lead to its overwintering in the natural environment of − 20 °C to − 30 °C. However, for other tuber and root crops, it is difficult to overwinter naturally. Based on this, we sequenced the transcriptome of Jerusalem artichoke tubers to explore its molecular mechanism of dormancy. Tuber dormancy is a very complex process. At present, it is considered that reaching sufficiently low temperatures is one of the key factors to induce dormancy-release of Jerusalem artichoke tubers (Kays 2007). However, the molecular mechanism of Jerusalem artichoke tuber dormancy remains elusive. This study carried out a detailed bioinformatics analysis of MADS-box genes related to dormancy, which lays a foundation for elucidating the molecular mechanism of Jerusalem artichoke tuber dormancy and developing the regulatory measures of Jerusalem artichoke tuber dormancy. Due to lack of understanding of tuber dormancy mechanism and slow development of artificial regulation technology, the development of Jerusalem artichoke tuber production and the full processing of tubers as industrial raw material are seriously restricted. Therefore, studying the mechanism of tuber dormancy is of great significance to Jerusalem artichoke cultivation, storage, and preservation. The functional analysis of family members of Jerusalem artichoke MADS-box needs further study.

Conclusions

A total of 23 MADS-box genes were identified from the recently obtained Jerusalem artichoke genome. These genes were divided into ten categories after cluster analysis with known dormancy genes with highly conserved motif structures. GO classification results show that most of these candidate genes have similar biological functions. Stage-dependent expression of MADS-box genes during the process of tuber dormancy and release of the Jerusalem artichoke were analyzed by qPCR. The results show that ten MADS-box genes may play an important role in the process of dormancy of Jerusalem artichoke tubers. This lays a foundation for further study of the role of the MADS-box gene family in the dormancy of Jerusalem artichoke and provides a valuable reference for elucidating the function of the MADS-box gene family in other tuber crops.

Funding

Funding was provided by Qinghai Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences Innovation Fund (Grant number: 2017-NKY-04), Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 31660588; 31660569; 31760600), The Fundamental Research Program of Qinghai (Grant number: 2017-ZJ-Y18), The Project of Qinghai Science & Technology Department (Grant number: 2016-ZJ-Y01), The Open Project of State Key Laboratory of Plateau Ecology and Agriculture of Qinghai University (Grant number: 2016-ZZ-06).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all the authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Liwen Zhang, Email: zhanglw@sari.ac.cn.

Qiwen Zhong, Email: 13997135755@163.com.

References

- Alvarez-Buylla ER, Liljegren SJ, Pelaz S, Gold SE, Burgeff C, Ditta GS, Vergara-Silva F, Yanofsky MF. MADS-box gene evolution beyond flowers: expression in pollen, endosperm, guard cells, roots and trichomes. Plant J. 2000;24(4):457–466. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielenberg DG, Wang YE, Li Z, Zhebentyayeva T, Fan S, Reighard GL, Scorza R, Abbott AG. Sequencing and annotation of the evergrowing locus in peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] reveals a cluster of six MADS-box transcription factors as candidate genes for regulation of terminal bud formation. Tree Genet Genomes. 2008;4(3):495–507. [Google Scholar]

- Borgmann K, Sinha P, Frommer WB. Changes in the two-dimensional protein pattern and in gene expression during the sink-to-source transition of potato tubers. Plant Sci. 1994;99(1):97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M, Segear E, Beers L, Knauber D, Suttle J. Dormancy in potato tuber meristems: chemically induced cessation in dormancy matches the natural process based on transcript profiles. Funct Integr Genomics. 2008;8(4):317–328. doi: 10.1007/s10142-008-0079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Can Q, Ferrándiz C, Yanofsky MF, Martienssen R. The FRUITFULL MADS-box gene mediates cell differentiation during Arabidopsis fruit development. Development. 1998;125(8):1509–1517. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.8.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Shi F. Dynamics of arginase gene evolution in metazoans. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2012;30(4):407–418. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2012.682207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A, Götz S. Blast2GO: a comprehensive suite for functional analysis in plant genomics. Int J Plant Genomics. 2008;2008:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2008/619832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilcenko H, Jariene E, Gajewski M, Sawicka B, Kulaitiene J, Cerniauskiene J. Changes in amino acids content in tubers of Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus L.) cultivars during storage. Acta Sci Pol Hortoru. 2013;12(2):97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Riquelme J, Lijavetzky D, Martínez-Zapater JM, Carmona MJ. Genome-wide analysis of MIKCC-type MADS box genes in grapevine. Plant Physiol. 2009;149(1):354–369. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.131052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filep R, Pal RW, Balázs VL, Mayer M, Nagy DU, Cook BJ, Farkas Á. Can seasonal dynamics of allelochemicals play a role in plant invasions? A case study with Helianthus tuberosus L. Plant Ecol. 2016;217(12):1489–1501. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A, Baum N, Saedler H, Theiβen G. Chromosomal mapping of the MADS-box multigene family in Zea mays reveals dispersed distribution of allelic genes as well as transposed copies. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23(11):1901–1911. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.11.1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeber K, Nakabayashi K, Miatton E, Leubner-Metzger G, Soppe WJ. Molecular mechanisms of seed dormancy. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35(10):1769–1786. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q, Ferrándiz C, Yanofsky MF, Martienssen R. The FRUITFULL MADS-box gene mediates cell differentiation during Arabidopsis fruit development. Development. 1998;125(8):1509–1517. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.8.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath DP. Dormancy-associated MADS-BOX genes: a review. In: Anderson J, editor. Advances in plant dormancy. Cham: Springer; 2015. pp. 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath DP, Chao WS, Suttle JC, Thimmapuram J, Anderson JV. Transcriptome analysis identifies novel responses and potential regulatory genes involved in seasonal dormancy transitions of leafy spurge (Euphorbia esula L.) BMC Genomics. 2008;9(1):536. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Cepas J, Forslund K, Coelho LP, Szklarczyk D, Jensen LJ, von Mering C, Bork P. Fast genome-wide functional annotation through orthology assignment by eggNOG-mapper. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34(8):2115–2122. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez S, Reighard G, Bielenberg D. Gene expression of DAM5 and DAM6 is suppressed by chilling temperatures and inversely correlated with bud break rate. Plant Mol Biol. 2010;73(1–2):157–167. doi: 10.1007/s11103-010-9608-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing W, Xiaoming Z, Guohua Y, Yu Z, Kaichun Z. Over-expression of the PaAP1 gene from sweet cherry (Prunus avium L ) causes early flowering in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Plant Physiol. 2013;170(3):315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann K, Melzer R, Theißen G. MIKC-type MADS-domain proteins: structural modularity, protein interactions and network evolution in land plants. Gene. 2005;347(2):183–198. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kays SJ. Biology and chemistry of Jerusalem artichoke: Helianthus Tuberosus L. J Agric Food Inf. 2007;10(4):352–353. [Google Scholar]

- Kofuji R, Sumikawa N, Yamasaki M, Kondo K, Ueda K, Ito M, Hasebe M. Evolution and divergence of the MADS-box gene family based on genome-wide expression analyses. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20(12):1963–1977. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krijthe N. Observations on the sprouting of seed potatoes. Eur Potato J. 1962;5(4):316–333. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman J, Kays SJ, Nottingham SF. Biology and chemistry of Jerusalem artichoke Helianthus tuberosus L. Biol Plant. 2008;52(3):15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lalusin AG, Nishita K, Kim S-H, Ohta M, Fujimura T. A new MADS-box gene (IbMADS10) from sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam) is involved in the accumulation of anthocyanin. Mol Genet Genomics. 2006;275(1):44–54. doi: 10.1007/s00438-005-0080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leake JR. Tansley Review No. 69. The biology of mycoheterotrophic (saprotrophic) plants. New Phytol. 1994;127(171):216. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb04272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leida C, Terol J, Martí G, Agustí M, Llácer G, Badenes ML, Ríos G. Identification of genes associated with bud dormancy release in Prunus persica by suppression subtractive hybridization. Tree Physiol. 2010;30(5):655–666. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpq008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leida C, Conesa A, Llácer G, Badenes ML, Ríos G. Histone modifications and expression of DAM6 gene in peach are modulated during bud dormancy release in a cultivar-dependent manner. New Phytol. 2012;193(1):67–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesur I, Bechade A, Lalanne C, Klopp C, Noirot C, Leplé JC, Kremer A, Plomion C, Le Provost G. A unigene set for European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) and its use to decipher the molecular mechanisms involved in dormancy regulation. Mol Ecol Res. 2015;15(5):1192–1204. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Reighard GL, Abbott AG, Bielenberg DG. Dormancy-associated MADS genes from the EVG locus of peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] have distinct seasonal and photoperiodic expression patterns. J Exp Bot. 2009;60(12):3521–3530. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Shao T, Yang H, Chen M, Gao X, Long X, Shao H, Liu Z, Rengel Z. The endogenous plant hormones and ratios regulate sugar and dry matter accumulation in Jerusalem artichoke in salt-soil. Sci Total Environ. 2017;578:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljegren SJ, Ferrándiz C, Alvarez-Buylla ER, Pelaz S, Yanofsky MF. Arabidopsis MADS-box genes involved in fruit dehiscence. Flower Newslett. 1998;25:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Li W, Zheng P, Xu T, Chen L, Liu D, Hussain S, Teng Y. Transcriptomic analysis of ‘Suli’ pear (Pyrus pyrifolia white pear group) buds during the dormancy by RNA-Seq. BMC Genomics. 2012;13(1):700. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 − ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H. The unfolding drama of flower development: recent results from genetic and molecular analyses. Genes Dev. 1994;8(7):745–756. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.7.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace I, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson J, Gibson T, Higgins D. Clustal W and clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min C, Xiao L, Lei H, Sun M, Li L, Chen X, Gao D, Ling L. Genome-wide analysis of Dof family genes and their expression during bud dormancy in peach (Prunus persica) Sci Hortic. 2017;214:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Niu Q, Li J, Cai D, Qian M, Jia H, Bai S, Hussain S, Liu G, Teng Y, Zheng X. Dormancy-associated MADS-box genes and microRNAs jointly control dormancy transition in pear (Pyrus pyrifolia white pear group) flower bud. J Exp Bot. 2016;67(1):239–257. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Par̆enicová L, de Folter S, Kieffer M, Horner DS, Favalli C, Busscher J, Cook HE, Ingram RM, Kater MM, Davies B. Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of the complete MADS-box transcription factor family in Arabidopsis: new openings to the MADS world. Plant Cell. 2003;15(7):1538–1551. doi: 10.1105/tpc.011544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry SE, Lehti MD, Fernandez DE. The MADS-domain protein AGAMOUS-like 15 accumulates in embryonic tissues with diverse origins. Plant Physiol. 1999;120(1):121–130. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde A, Bhalerao RP. Plant dormancy in the perennial context. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12(5):217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford PP, Flood AE. Seasonal changes in the invertase and hydrolase activities of Jerusalem artichoke tubers. Phytochemistry. 1971;10(5):953–956. [Google Scholar]

- Ryuta S, Hisayo Y, Tomomi O, Hiroaki J, Yuto K, Takashi A, Ryutaro T. Functional and expressional analyses of PmDAM genes associated with endodormancy in Japanese apricot. Plant Physiol. 2011;157(1):485–497. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.181982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saengkanuk A, Nuchadomrong S, Jogloy S, Patanothai A, Srijaranai S. A simplified spectrophotometric method for the determination of inulin in Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus L.) tubers. Eur Food Res Technol. 2011;233(4):609. doi: 10.1007/s00217-011-1552-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saengthongpinit W, Sajjaanantakul T. Influence of harvest time and storage temperature on characteristics of inulin from Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus L.) tubers. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2005;37(1):93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Shu Y, Yu D, Wang D, Guo D, Guo C. Genome-wide survey and expression analysis of the MADS-box gene family in soybean. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(6):3901–3911. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubi BE, Sakamoto D, Ban Y, Shimada T, Ito A, Nakajima I, Takemura Y, Tamura F, Saito T, Moriguchi T. Molecular cloning of dormancy-associated MADS-box gene homologs and their characterization during seasonal endodormancy transitional phases of Japanese pear. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2010;135(2):174–182. [Google Scholar]

- Watson A, Renney A. The biology of Canadian weeds.: 6. Centaurea diffusa and C. maculosa. Can J Plant Sci. 1974;54(4):687–701. [Google Scholar]

- Weigel D. The genetics of flower development: from floral induction to ovule morphogenesis. Annu Rev Genet. 1995;29(1):19–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.000315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu R-M, Walton EF, Richardson AC, Wood M, Hellens RP, Varkonyi-Gasic E. Conservation and divergence of four kiwifruit SVP-like MADS-box genes suggest distinct roles in kiwifruit bud dormancy and flowering. J Exp Bot. 2011;63(2):797–807. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiaoxia Z, Qingheng W, Yu J, Ronglian H, Yuewen D, Huan W, Xiaodong D. Identification of genes potentially related to biomineralization and immunity by transcriptome analysis of pearl sac in pearl oyster Pinctada martensii. Mar Biotechnol. 2012;14(6):730–739. doi: 10.1007/s10126-012-9438-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Zhang Q, Sun L, Du D, Cheng T, Pan H, Yang W, Wang J. Genome-wide identification, characterisation and expression analysis of the MADS-box gene family in Prunus mume. Mol Genet Genomics. 2014;289(5):903–920. doi: 10.1007/s00438-014-0863-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamane H, Kashiwa Y, Ooka T, Tao R, Yonemori K. Suppression subtractive hybridization and differential screening reveals endodormancy-associated expression of an SVP/AGL24-type MADS-box gene in lateral vegetative buds of Japanese apricot. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2008;133(5):708–716. [Google Scholar]

- Yamane H, Ooka T, Jotatsu H, Hosaka Y, Sasaki R, Tao R. Expressional regulation of PpDAM5 and PpDAM6, peach (Prunus persica) dormancy-associated MADS-box genes, by low temperature and dormancy-breaking reagent treatment. J Exp Bot. 2011;62(10):3481–3488. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]