Abstract

Background

Palliative endoscopic stents or surgical by‐pass are often required for inoperable pancreatic carcinoma to relieve obstruction of the distal biliary tree. The optimal method of intervention remains unknown.

Objectives

To compare surgery, metal endoscopic stents and plastic endoscopic stents in the relief of distal biliary obstruction in patients with inoperable pancreatic carcinoma.

Search methods

We searched the databases of the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Group specialised register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CancerLit, Current Concepts Database and BIDS (September 2002 to September 2004). The searches were re‐run in December 2005 and November 2008.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing surgery to endoscopic stenting, endoscopic metal stents to plastic stents, and different types of endoscopic plastic and metal stents, used to relieve obstruction of the distal bile duct in patients with inoperable pancreatic carcinoma.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. Adverse effects information was collected from the trials.

Main results

Twenty‐nine trials, that enrolled over 1,700 participants with pancreatic carcinoma, were included. Three eligible studies compared plastic stents to surgery. Endoscopic stenting with plastic stents was associated with a reduced risk of complications (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.45 ‐ 0.81), but with higher risk of recurrent biliary obstruction prior to death (RR 18.59, 95% CI 5.33 ‐ 64.86) when compared with surgery. There was a trend towards lower risk of 30‐day mortality with plastic stents (p=0.07, RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.32, 1.04). One published study compared metal stents to surgery and reported lower costs and better quality‐of‐life with metal stents. Nine studies compared metal to plastic stents. Metal stents were associated with a lower risk of recurrent biliary obstruction than plastic stents (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.38 ‐ 0.62). There was no significant difference in risk of technical failure, therapeutic failure, complications or 30‐day mortality by meta‐analysis. When different types of plastic stents were compared to polyethylene stents, only perflouro alkoxy plastic stents had superior outcomes in one trial. The addition of an anti‐reflux valve improved the patency of Teflon stents.

Authors' conclusions

Endoscopic metal stents are the intervention of choice at present in patients with malignant distal obstructive jaundice due to pancreatic carcinoma. In patients with short predicted survival, their patency benefits over plastic stents may not be realised. Further RCTs are needed to determine the optimal stent type for these patients.

Plain language summary

Palliative biliary stents for obstructing pancreatic cancer

The majority of patients with cancer of the pancreas are diagnosed only after blockage of the bile ducts has occurred. Surgical by‐pass (SBP) or endoscopic stenting (ES) of the blockage are the treatment options available for these patients. This review compares 29 randomised controlled trials that used surgical by‐pass, endoscopic metal stents or endoscopic plastic stents in patients with malignant bile duct obstruction. All included studies contained groups where cancer of the pancreas was the most common cause of bile duct obstruction. This review shows that endoscopic stents are preferable to surgery in palliation of malignant distal bile duct obstruction due to pancreatic cancer. The choice of metal or plastic stents depends on the expected survival of the patient; metal stents only differ from plastic stents in the risk of recurrent bile duct obstruction. Polyethylene stents and stainless‐steel alloy stents (Wallstent) are the most studied stents.

Background

Description of the condition

Pancreatic cancer accounts for 3% of all new cancers in the UK, and is the 7th commonest cause of death from cancer in the EU (ONS 2007; Bray 2002 ). Despite technological advances, the five year survival remains less than 5% (ONS 2007). In the majority of patients, pancreatic carcinoma presents at a late stage making most of these tumours inoperable when diagnosed (Baxter 2007). Because of this dismal natural history, palliation remains the principal management in such patients, and relief of biliary tree obstruction is a prime concern.

Biliary tree obstruction and the consequent jaundice occur in 70 to 90% of patients with pancreatic neoplasms and has important consequences for a patient's quality of life (van den Bosch 1994). It can potentially exacerbate the patient's condition by causing cholangitis, malabsorption, pruritus and liver failure (van den Bosch 1994). Although initial results with surgical bypass demonstrated low rates of recurrent jaundice (2‐5%), the surgery itself carries an appreciable risk of post‐operative morbidity and mortality (Das 2000). Comparative studies have recorded complication rates up to 56% and 30‐day mortality up to 24% (Yermilov 2009; Andersen 1989). Furthermore, the operation is extensive and may have important quality of life consequences for these patients who often only have a short life expectancy. However, operative bypass could provide the opportunity during the procedure for gastrojejunostomy in patients with duodenal obstruction and celiac plexus neurolysis for those with severe pain (Van Heek NT 2003; Weaver 1987). Surgical decompression has been advocated in most patients who, at the time of laparotomy for planned tumour resection, are found to have unresectable disease, and in occasional patients with longer projected survival (Liliemoe 1999).

Description of the intervention

In response to these operative complications, advances in minimally‐invasive therapy have led to the development of luminal stents whose insertion aims to relieve jaundice and hence avoid the need for surgery. These can be inserted percutaneously under fluoroscopic guidance, or endoscopically, which is the focus of this review. Endoscopic placement is the primary mode of insertion in most centres for distal biliary obstruction due to pancreatic cancer. Once inserted via the endoscope, these endoprosthesis allow minimally invasive relief of biliary obstruction and shorter hospitalisations (Shepherd 1988). Unfortunately, obstructive jaundice recurs in up to 50% of patients treated endoscopically, necessitating recurrent intervention and stent replacement (Stern 2008). Less common potential complications related to their use include malposition, stent migration and breakage (Born 1996; Plotner 1991).

Early biliary stents came in the form of plastic prosthesis that was inserted across the obstructing pancreatic mass to provide drainage of the biliary tree. The high occlusion rates in these appeared to occur due to development of biofilm on the internal surface with bacterial colonisation (Sung 1993). The precipitation of calcium bilirubinate promoted by bacterial enzyme activity lines the luminal surface and narrows the functional stent diameter. The biliary sludge that accumulates as a result of delayed drainage facilitates stent blockage. Other studies have suggested a role for bilioduodenal reflux and food fibres in stent blockage (van Berkel 2005; Weickert 2001).As a result, a number of methods have been employed to enhance stent patency. For example, irregularities on the surface of the stent may enhance precipitation and so manufacturers have adapted this type of stent by producing them from, or coating them with, numerous different materials to impair bacterial colonisation (Sung 1993; Leung 1992). However, the clinical benefits from these specification changes are variable (Das 2000). Similarly, prophylactic use of antibiotics in addition to stents has not been shown to improve patency (Chan 2005; Galandi 2002).

Technological advances have also produced expandable endoscopic metal mesh stents to improve stent patency. With a wider bore than plastic stents, several studies have shown their patency lasts an average of 9 months (Davids 1992a). A number of uncontrolled and retrospective studies have shown advantages to these self expanding metal stents in comparison to plastic stents and these benefits have remained in randomised studies (Lammer 1996; Prat 1998a; Knyrim 1993). The most commonly studied types are constructed from stainless‐steel alloy (Wallstent) or nickel‐titanium alloy (Ultraflex Diamond). Stent occlusion may still occur, due to tumour growth through the mesh, and once placed they are mostly permanent (unlike plastic stents). The addition of a polyurethane cover to these stents has not been shown convincingly to improve patency, or has done so with a higher risk of complications (Hausegger 1998; Isayama 2004). Another strong limiting factor to their use is their cost, being between 15 and 40 times more expensive than plastic stents. Cost‐effectiveness analyses have found metal stents to be economical only when patients survive beyond six months (Arguedas 2002; Moss 2007).

Why it is important to do this review

Obstructive jaundice due to invasive pancreatic carcinoma can thus be relieved by surgery or endoprosthesis insertion. What is not clear is which method is optimal. Surgery may offer high success rates in terms of relief of obstructive jaundice but carries high risks in terms of post‐operative morbidity and mortality. Many of the secondary advantages of surgery have been met by advances in endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and duodenal stents. Stents appear to offer a less invasive option, but replacement rates rise with patient survival and with numerous different types of stent there is no definitive evidence by which to judge their relative efficacy. As adjunctive treatment such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy may prolong patient survival, determining which stent type produces the longest patency time is important. This review aims to assess the evidence to determine whether surgery or endoscopic stents offer the best solution to obstructive jaundice due to pancreatic cancer and, likewise, if stents are to be used, which type offers the best outcomes.

Objectives

To undertake a systematic analysis of the published literature relating to the use of surgery or endoscopic stents for the relief of obstructive jaundice caused by pancreatic cancer.

The primary objective was to compare surgical by‐pass to endoscopic stents. The secondary objective was to compare the different types of endoscopic stents used in RCTs.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials comparing surgery to endoscopic stents, comparing metal to plastic endoscopic stents, or comparing types of endoscopic plastic stents and metal stents, when used to relieve biliary tree obstruction from inoperable pancreatic carcinoma.

Types of participants

Patients with pancreatic carcinoma diagnosed by radiological and clinical assessment or confirmed histologically. We only considered data on patients deemed unsuitable for curative resection on the basis of advanced stage of disease or poor operative risk.

Types of interventions

The following interventions in the relief of jaundice due to pancreatic cancer unsuitable for curative resection: Biliary by‐pass surgery (choledochoduodenostomy, choledochojejunostomy or hepaticojejunostomy) Endoscopic metal stents of different materials and construction Endoscopic plastic stents of different materials and construction

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measures were therapeutic success (defined as effect on degree of jaundice, serum bilirubin or pruritus).

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome measures were procedure‐free survival, overall survival, procedure‐related complications (early and late), technical success, stent patency, hospital stay, patient compliance, quality‐of‐life and cost‐effectiveness

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Trials were identified by searching MEDLINE 2002 to November 2008, EMBASE 2002 to November 2008 and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, The Cochrane Library (Issue 4, Year 2008). We did not confine our search to English language publications. Searches in all databases were updated in November 2008.

The Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLIBNE, Sensitivity maximising version, Ovid format (Higgins 2008), was combined with the search terms in Appendix 1 to identify randomised controlled trials in MEDLINE. The MEDLINE search strategy was adapted for use in the other databases searched.

The standard Cochrane search strategy filter for identifying randomised controlled trials was applied to all searches.

Searching other resources

Reference lists from trials selected by electronic searching were hand searched to identify further relevant trials. Published abstracts from conference proceedings from the United European Gastroenterology Week (published in Gut) were hand‐searched to 2006, and Digestive Disease Week (published in Gastroenterology) to 2008. In addition members of the Cochrane UGPD Group, and experts in the field were contacted and asked to provide details of outstanding clinical trials and any relevant unpublished materials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two independent reviewers scanned the abstract of every trial identified by the search to determine eligibility. Blinding to source was not performed. We selected full articles for further assessment if the abstract suggested the study included patients with pancreatic carcinoma and compared surgical or endoscopic relief of biliary obstruction. If these criteria were unclear from the abstract, we retrieved the full article for clarification. We excluded papers not meeting the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion, and if required, by consultation with the review group's editors.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data from published reports using standardised forms with disagreements resolved by discussion between the reviewers. The following data were extracted wherever possible:

method of randomisation

blinding for outcome assessor, patient and carer

criteria for patient inclusion and exclusion

patients characteristics including mean/median age, age range, sex ratio

number of patients assigned to each treatment group

number of co‐morbid conditions ‐ details of intervention

effect on survival

effect on quality of life

length of hospital stay

number and frequency of procedure related complications

duration of therapy and any co interventions

frequency of re‐interventions

number of patients withdrawn and reasons for these withdrawals

adverse reactions and outcomes

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias in each study, using methods described in the Cochrane Reviewer's Handbook. Briefly, a description was made of six separate components of each trial's methods; sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and "other issues". For each component, an assessment was made relating to the risk of bias for that entry. This was achieved by describing the adequacy of the study for that component as "Yes" , "No" or "Unclear".

Data synthesis

Statistical guidance was available from the editorial base and the reviewers' host institutions. Meta‐analysis was only be undertaken if the results were considered meaningful. Dichotomous data was summarised preferentially using relative risk, and continuous data using weighted mean difference. We performed a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity statistically and discussed clinical heterogeneity. If trials proved to be too heterogeneous we combined results in a narrative review.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses included testing meta‐analysis results using a validity threshold, altering the statistical approach of analysis, and including reasonable values for missing data.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

A total of 96 studies were reviewed for consideration of inclusion in this review; 29 were included and 67 were excluded based on inclusion / exclusion criteria.

Included studies

The 29 included studies (see Characteristics of included studies) involved 2,762 participants, over 1,700 with pancreatic cancer, and consisted of 1 trial comparing surgery to metals stents, 3 trials comparing surgery to endoscopic plastic stenting, 9 trials comparing endoscopic metal to plastic stents, 5 comparing Teflon to polyethylene stents, 3 comparing polyurethane to polyethylene, 4 comparing other types of plastic stents, and 4 comparing different types of metal stents. Twenty‐four of the included studies were in the form of published papers, and five were only published as abstracts from conference proceedings. We contacted authors of abstracts for additional data. All included trials contained a mixture of patients with "malignant obstructive jaundice". Only one of these studies (Artifon 2006) provided separate data for pancreatic causes of malignant obstruction alone, or subgroup analysis for this group. The percentage of patients with inoperable pancreatic cancer in the included studies ranged from 39 to 95% (mean 76%). Twenty‐five of the 29 studies specified that they included only enrolled patients with mid or distal malignant bile duct obstruction. Thus the analyses are based on all patients with malignant obstructive jaundice, the majority of whom had pancreatic cancer, and the analyses should be considered in this light. The total numbers of patients randomised were 336 in the surgery / stent studies, 871 in the metal / plastic stent studies, 1023 in the plastic stent studies, and 532 in the metal / metal studies Not all of the considered outcomes were reported in each study; the number of outcomes ranged from 1 to 10 (mean 6). In addition, the methods for measuring some of the outcomes differed between studies; many studies reported median values for time outcomes. Cost‐effectiveness measures also differed in the unit of currency, and the time point at which costs were estimated. There were major differences in the detail of reporting of results in the form of raw data; many studies only reported "no significant difference".

Excluded studies

Thirty‐five studies were excluded after reviewing the full text of the study. Twenty one studies were excluded as they were not randomised and 14 were excluded for other reasons (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

The results of the "risk of bias" assessment are described for each individual study in the Characteristics of included studies table. A graphical representation of the overall relative prevalence of each component across all the included studies is shown in Figure 1 .

1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

The method of allocation concealment was adequate in 19 studies, unclear in 9 studies, and not stated in one study.

Blinding

Only two trials reported blinding of patients to interventions. The majority of trials did not comment on whether participants, or those involved in follow‐up and outcome reporting, were blinded to interventions. In the stent studies it can be assumed that all endoscopists were not blinded to the stent type inserted. No study reported whether those determining outcomes were blinded to the intervention.

Incomplete outcome data

Follow‐up

Within the 2,762 patients randomised in total, there were 21 patients reported as lost to follow‐up The largest number lost in one trial was six (Costamagna 2000).

Effects of interventions

Surgery versus Plastic Stents

There were three trials reported that compared surgery to endoscopic plastic stenting and met the inclusion criteria for this study (Andersen 1989; Shepherd 1988; Smith 1994). In all three trials the baseline characteristics of participants were similar, with 64 to 86% of participants having pancreatic carcinoma as the underlying diagnosis. One trial did not treat with antibiotics at the time of procedure, two used polyethylene stents, and the third used Teflon stents; the results were similar for all three stent groups, except for technical success. The majority of surgical interventions were cholecystojejunostomy or choledochoduodenostomy. The total number of randomised patients was 308, and none were lost to follow‐up.

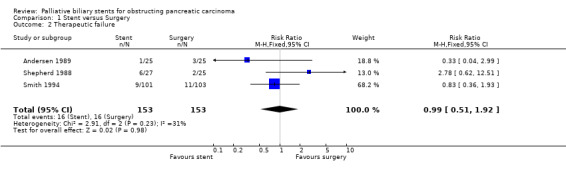

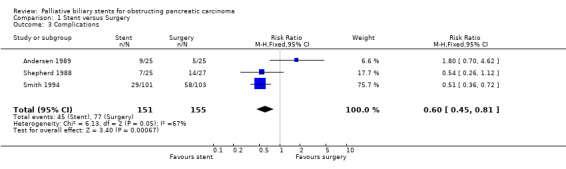

There was no difference in relative risk for technical failure (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.31, 1.44; Analysis 1.1) and therapeutic failure (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.51, 1.92; Analysis 1.2) between stenting and surgery in malignant obstructive jaundice. The relative risk of all complications was significantly reduced in those receiving stents compared to surgery (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.45 ‐ 0.81; Analysis 1.3) with a p value of 0.0007. One trial (Andersen 1989) only reported infectious complications; when this data was excluded from meta‐analysis the relative risk of complications for stenting fell to 0.52 (95% CI 0.38 ‐ 0.51). The 30‐day mortality showed a trend in favour of stenting (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.32 ‐ 1.04; Analysis 1.4), but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.07). The relative risk of recurrent biliary obstruction prior to death / end of study was 18.59 (95% CI 5.33 ‐ 64.86; Analysis 1.5) in favour of surgery, which was highly statistically significant (p < 0.00001). There were no significant differences in survival or quality of life between the two treatment groups in any of the studies. The median survival of participants in Andersen et al study (Andersen 1989) was 84 days (range 3 to 498) for particpants treated endoscopically versus 100 days (range 10 to 642) for those managed surgically. In Shepherd et al (Shepherd 1988) the figures were 152 (range 39 to 411) days and 124.5 (range 52 to 354) for endoscopically versus surgically treated patients and for Smith et al (Smith 1994) 26 weeks (no range given) and 21 weeks (no range given). Two of the trials demonstrated shorter total hospital stay for those in the stented group (Shepherd 1988; Smith 1994). These outcomes were not suitable for meta‐analysis due to the different methods of reporting results. Sensitivity analysis performed by altering the statistical test, and model (random or fixed) did not change the results.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stent versus Surgery, Outcome 1 Technical failure.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stent versus Surgery, Outcome 2 Therapeutic failure.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stent versus Surgery, Outcome 3 Complications.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stent versus Surgery, Outcome 4 30‐day mortality.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stent versus Surgery, Outcome 5 Recurrent biliary obstruction prior to death / end of study.

Metal Stent versus Plastic Stents

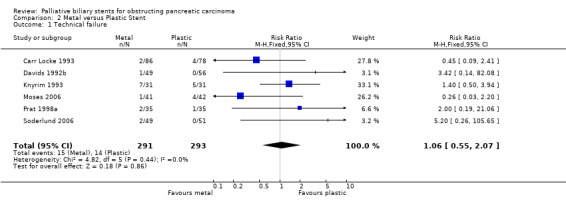

Nine studies were identified that met inclusion criteria and compared endoscopic metal to plastic stents (Carr Locke 1993; Davids 1992b; Kaassis 2003; Kastinelos 2006; Knyrim 1993; Moses 2006; Prat 1998a; Rosch 1997; Soderlund 2006). All compared uncovered metal Wallstents to polyethylene stents except 2 which used covered Wallstents (Moses 2006; Soderlund 2006), and another 2 which used teflon stents (Kaassis 2003; Kastinelos 2006). As three non‐RCT studies have shown no difference between covered and uncovered Wallstents (Park 2006; Shim 1998; Yoon 2006), meta‐analysis was performed with and without these studies; the included data did not alter the results. In one study unsuccessful endoscopic insertion was repeated using a combined percutaneous‐endoscopic approach (rendez‐vous); for meta‐analysis the technical success was based on the endoscopic success only, and complications were not included in meta‐analysis (Knyrim 1993). The percentage of patients in these trials with inoperable pancreatic cancer ranged from 52 to 74%, and all studies contained patients with similar baseline characteristics. In total, 871 participants were randomised and six were lost to follow‐up. All studies were considered at moderate risk of bias based on quality criteria. Seven studies reported data for risk of technical failure, with no difference between metal and plastic stents (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.55‐ 2.07; Analysis 2.1). There were no significant differences in any of the studies for risk of therapeutic failure (RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.39 ‐ 4.57; Analysis 2.2) or complications (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.45 ‐ 1.9; Analysis 2.3) between metal and plastic stents. The relative risk of death within 30 days after intervention was 1.43 (96% CI 0.79 ‐ 2.58; Analysis 2.4) in the metal stent group, which was not statistically significant. However, metal stents had a significantly reduced relative risk of recurrent biliary obstruction prior to death / end of study (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.38 ‐ 0.62; Analysis 2.5). There were no significant differences reported for survival, or quality of life in these studies. The results on survival and stent patency were not suitable for meta‐analysis (Table 1). Five studies reported significantly longer duration of patency for metal stents over plastic stents (p < 0.05), but there was no difference in patient survival between either stent type. For cost‐effectiveness, two studies found significant difference for metal stents, but two others did not. Three studies reported a higher number of ERCPs per patient in the plastic stent groups (mean 1.6 versus 1.0 per patient). These outcomes were not suitable for meta‐analysis due to the method of reporting results. Sensitivity analysis performed by altering the statistical test, and model (random or fixed) did not change the results. There was no statistical heterogeneity between studies.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Metal versus Plastic Stent, Outcome 1 Technical failure.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Metal versus Plastic Stent, Outcome 2 Therapeutic failure.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Metal versus Plastic Stent, Outcome 3 Complications.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Metal versus Plastic Stent, Outcome 4 30‐day mortality.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Metal versus Plastic Stent, Outcome 5 Recurrent biliary obstruction prior to death / end of study.

1. Stent patency & patient survival (median days) ‐ metal versus plastic stents.

| Study | Metal ‐ patency | Plastic ‐ patency | p value | Metal ‐ survival | Plastic ‐ survival | p value |

| Carr‐Locke | 111 | 62 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Davids | 273 | 127 | NS | 175 | 147 | NS |

| Kaassis | N/A | 165 | 0.007 | 153 | 99 | NS |

| Kastinelos 2006 | 255 | 123 | 0.002 | 272 | 207 | NS |

| Knyrim | 186 | 138 | <0.05 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Moses | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Prat | 144 | 96 | <0.05 | 135 | 144 | NS |

| Rosch | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Soderlund | 108 | 54 | 0.002 | 159 | 117 | NS |

Teflon Stent versus Polyethylene Stent

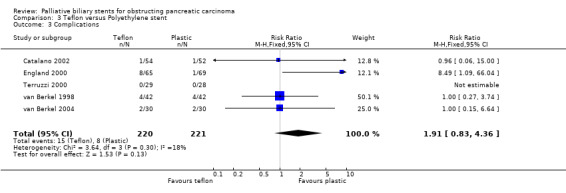

Within the 12 studies using plastic stents for obstructing biliary cancer, there were five studies comparing Teflon to polyethylene biliary stents (Catalano 2002; England 2000; Terruzzi 2000; van Berkel 1998; van Berkel 2004), three comparing polyurethane to polyethylene stents (Costamagna 2000; Landoni 2000; van Berkel 2003), two comparing teflon to polyurethane (Benz 1998; Schilling 2003), and two comparing other combinations (Prat 1998a; Tringali 2003). There were risk of bias for each study is described below (Characteristics of included studies). Within the Teflon / polyethylene studies four compared 10 Fr Tannenbaum‐type Teflon stents to 10 Fr Cotton‐Leung polyethylene stents, and one used a Teflon stent with side‐holes. The percentage of patients with pancreatic carcinoma ranged from 65 to 95% in these studies. The characteristics of participants in both intervention groups were comparable at baseline. In comparison of teflon and polyethylene stents, there was no statistical difference between the two stents with regard to risk of technical failure (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.34 ‐ 4.5; Analysis 3.1), 30‐day mortality (RR 1.27, 95% CI 0.77 ‐ 2.11; Analysis 3.4) or recurrent biliary obstruction prior to death (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.78 ‐ 1.24; Analysis 3.5). The relative risk of therapeutic failure with a Teflon stent was significantly higher (RR 2.84, 95% CI 1.31‐ 6.16; Analysis 3.2) than with polyethylene stents (p = 0.008). The relative risk of complications was higher in those who received a Teflon stent (RR 1.91, 95% CI 0.83 ‐ 4.36; Analysis 3.3), due to the results of one study (England 2000) but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.13). All five studies analysed reported median duration of stent patency and patient survival, but there were no differences between both stent types for either of these outcomes (Table 2). Sensitivity analysis performed by altering the statistical test, and model (random or fixed) did not change the results. There was no statistical heterogeneity between studies.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Teflon versus Polyethylene stent, Outcome 1 Technical failure.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Teflon versus Polyethylene stent, Outcome 4 30‐Day mortality.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Teflon versus Polyethylene stent, Outcome 5 Recurrent biliary obstruction prior to death / end of study.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Teflon versus Polyethylene stent, Outcome 2 Therapeutic failure.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Teflon versus Polyethylene stent, Outcome 3 Complications.

2. Stent patency & patient survival (median days) ‐ Teflon versus Polyethylene (PE).

| Study | Teflon ‐ patency | PE ‐ patency | p value | Teflon ‐ survival | PE ‐ survival | p value |

| Catalano | 91 | 94 | >0.05 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| England | 181 | 133 | >0.05 | 115 | 151 | >0.05 |

| Terruzzi | 96 | 75.5 | >0.05 | 88 | 76.5 | >0.05 |

| van Berkel '98 | 83 | 80 | >0.05 | 163 | 140 | >0.05 |

| van Berkel '04 | 102 | 142 | >0.05 | 121 | 105 | >0.05 |

Other Stent Comparisons ‐ plastic stents

Two trials comparing Tannenbaum‐type Teflon stents to both uncoated and hydrophilic‐coated polyurethane stents randomised 168 patients (Benz 1998; Schilling 2003). Neither reported a difference in outcomes (time to stent dysfunction, technical success, therapeutic success, complications) between groups. Two trials compared polyethylene stents to hydrophilic‐coated polyurethane stents, with 183 patients randomised. There was no difference between interventions with regard to therapeutic success, complications, 30‐day mortality or survival. One of the studies demonstrated a significantly longer patency for polyethylene stents (105 days versus 77 days) (van Berkel 2003). Omitting side‐holes, or using uncoated polyurethane, does not improve the results from standard polyethylene stents (Landoni 2000). However one RCT comparing polyethylene to perflouro alkoxy stent (Double Layer Stent) placed endoscopically found a shorter patency period and higher risk of stent occlusion prior to death (RR 3.05; 95 % CI, 1.57 ‐ 5.89) with polyethylene stents (Tringali 2003). Finally, a single study (Dua 2006) compared the addition of an anti‐reflux valve to a Tannenbaum stent to standard Tannenbaum stents. The addition of this valve did improve median stent patency from 101 to 145 days (p=0.02), without any difference in technical success or complications.

Other Stent Comparisons ‐ metal stents

There were four published RCTs comparing different types of endoscopic metal stents in malignant biliary obstruction, and one study that compared metal stents to surgery in metastatic pancreatic cancer. The first compared polyurethane covered to uncovered Ultraflex Diamond stents. This reported a higher cumulative patency rate in covered stents (304 days versus 161 days), but also a higher incidence of complications with this stent (8/57 versus 3/55) (Isayama 2004). The second compared ferrous stainless steel radial stent (Spiral Z‐Stent) to standard Wallstent in 145 patients (Shah 2003). The two stents were comparable results in terms of stent placement, stent occlusion, time to occlusion and median patency rates. One study that compared a nitinol non‐forshortening metal stent (Zilver) to a 10mm Wallstent found no difference between the stent in terms of technical success, complications, mortality or patency (Howell 2006). Kastinelos et al compared a Hanaro uncovered to a Luminex uncovered self‐expanding metal stent (Kastinelos 2008). There was no difference between these stent types in any measured outome. Finally, a single study compared a self‐expanding metal stent to surgery for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer (Artifon 2006). This small study (N=30) reported no differences in technical success, complications or survival betwen both interventions, but patients treated with the metal stent had lower costs and better quality of life scores at 30 days follow‐up.

Discussion

Summary of main results

In patients with malignant distal biliary tree obstruction due to advanced pancreatic carcinoma, endoscopic stenting with plastic stents is associated with fewer complications, shorter total hospital stay, but with a higher risk of recurrent biliary obstruction than surgery. There is no difference between the two interventions with regard to technical success, therapeutic success, survival, or quality of life in the studies reviewed. There was a trend towards higher 30‐day mortality with surgery in the meta‐analysis, but no individual trial reported a significant difference. These results may not be particular to endoscopic stents, as the one randomised trial published comparing percutaneous stents and surgery reported no significant difference in outcome between both groups (Bornman 1986). The results of these trials confirm the role of palliative endoscopic stenting as the preferred therapy over surgery in the management of inoperable biliary obstruction due to pancreatic carcinoma. However, it should be noted that only three randomised trials comparing surgery to stents were identified and these span a reasonably long time period (1988 to 1994). In recent years considerable advances have taken place in pancreatic surgery to attempt to improve its efficacy and safety. Endoscopic stents have also not been compared to laparoscopic biliary bypass, which may have advantages over open approaches (Tang 2005). The single small study that has compared surgery to metal stents (Artifon 2006) did report that metal stents had lower costs and improved short‐term quality of life compared to surgery. A longer‐term comparison of quality‐of‐life would be worthwhile in this group.

Our review of the data comparing metal stents to plastic stents in this patient group confirms that there is no difference between the two interventions in technical failure, therapeutic failure, complications or 30‐day mortality. Metal Wallstents lead to significantly less episodes of recurrent biliary obstruction, and reduced re‐intervention rates than plastic stents. The median time to stent occlusion in these studies ranged from 62 to 165 days for plastic stents, and 111 to 273 days for metal stents. However, median length of survival ranged from 99 to 175 days, suggesting that many patients die before either stent occludes. The differences between stent patency rates appear at three months after insertion. None of the continuous outcome data was comparable between studies as all used medians of values to compare groups. Although metal stents have clear benefits in terms of patency, their higher initial cost raises issues of cost‐effectiveness. No conclusion could be made from the comparisons of cost‐effectiveness from these studies. One study in this review examined cost‐effectiveness over a number of time points from initial insertion; there was no difference in costs per patient in those surviving less than six months, but metal stents has a higher cost per patients when patients survived less than three months (Prat 1998a). A cost‐effective analysis based on Markov models has also made this conclusion (Arguedas 2002). A number of other factors have previously been suggested as a guide to when to select a plastic stent over a metal stent in patients with malignant obstructive jaundice. These include the presence of liver metastases (Kaassis 2003), tumour size (Prat 1998b), and predicted survival less than four months (Yeoh 1999). A prospective study of metal stents in malignant biliary obstruction reported the absence of metastases and coadjuvant chemotherapy as independent predictive factors of survival > 4 months in multi‐variate analysis (Gomez 2006). In the studies reviewed, only 40 to 50% of patients survived beyond four months.

The comparison of the role of Teflon and polyethylene stents demonstrated higher risk of therapeutic failure (RR 2.84) with 10Fr Tannenbaum‐type Teflon stent in the three studies that reported this outcome. This does not appear to be related to experience, as the studies date from 1998 to 2004, with similar results. There was no significant difference in any of the other outcomes measured. The addition of side‐holes to Tannenbaum stents, or a stainless steel mesh with polyamide outer layer, does not improve outcome compared to standard polyethylene stents (van Berkel 1998; van Berkel 2004). Similarly neither hydrophilic‐coated polyurethane, uncoated polyurethane, nor the omission of side‐holes improves outcomes compared to polyethylene or Tannenbaum Teflon stents (Landoni 2000; Sung 1994). The only improvement on polyethylene was with the perflouro alkoxy plastic stent in one RCT (Tringali 2003). The only improvement in Tannenbaum stents was a longer patency when an anti‐reflux valve was added (Dua 2006).

There is a paucity of RCTs comparing the different types of endoscopic metal stents in palliation of malignant biliary obstruction of any cause. Two retrospective studies comparing the Wallstent (stainless‐steel alloy) to the Ultraflex Diamond stent (nickel‐titanium alloy) reported no differences between the stents in one, and improved Wallstent patency in another (Ahmad 2002; Dumonceau 2000). A prospective RCT would be useful in this area. The three published RCTs comparing types of endoscopic metal stents have reported similar outcomes to the standard Wallstent (Howell 2006; Shah 2003). One trial that compared covered to uncovered Diamond stents reported less occlusion (14% versus 38%) at the expense of more complications with covered stents; 4.2% developed cholecystitis and 8.7% developed pancreatitis (Isayama 2004). The cumulative patency of the covered stents was significantly higher in patients with pancreatic cancer (p = 0.0363) and metastatic lymph nodes (p = 0.0354) in this trial. Given that these participants already have a terminal condition, this high complication rate would likely impact significantly on quality‐of‐life. Like the early studies of different types of endoscopic plastic stents, further RCTs would be required to assess the role of covered metal stents.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

A number of points need to be kept in mind when considering these results. Firstly, as discussed above (see 'Description of studies') the data includes a minority of participants with distal bile duct cholangiocarcinoma as no data for pancreatic carcinoma alone was available. These patients had cancers whose biological behaviour may be very different to pancreatic cancer, and thus influence outcomes. Likewise, not all patients had a pathological diagnosis of disease. This is a direct result of the difficulty of obtaining specimens and the extent of illness in these patients. Although unavoidable, this is a potential source of bias in the studies. An attempt was made to undertake sub‐group analyses of proven pancreatic cancer patients only but this was thwarted by poor reporting of disease‐specific results in the literature. We cannot, therefore, discount the fact that the presence of non‐pancreatic tumours within the study population is confounding the results. However, in each study the randomisation process should have led to an even distribution of non‐pancreatic cancer patients across the study arms. This should go some way to limiting the potential bias. In addition univariate analysis has not identified tumour type as an influence on either stent patency or patient survival in patients with malignant biliary tract obstruction (Davids 1992b; Kaassis 2003; Prat 1998b). In actual clinical practice, palliative management of malignant biliary obstruction is not influenced by the underlying histological diagnosis (Das 2000).

Secondly, the trials are spread over 20 years, and improvements in techniques over time may influence differences between studies. Finally the majority of the studies reviewed failed to report whether participants or outcome assessors were blinded to the intervention each participant was randomised to. It is possible that unblinded outcome assessors may allow detection bias to affect results. Blinding of intervention was not a practical option in the surgical trials. However in the endoscopic stent trials it would be possible to blind the patients and assessors (but not endoscopists) to the stent type without adversely affecting clinical outcome. There was little consistency in the methods of measuring outcomes, and a number did not report complete results. Although cross‐over was permitted between arms, most studies did not include comparisons of results as per randomisation as well as treatment.

Finally, this review's purpose was to compare endoscopic stents to surgery and other endoscopic stent types only. An alternative approach is to place the stents percutaneously via the trans‐hepatic route, in particular for proximal biliary obstruction. These two approaches have only been compared in two RCTs. The more recent reported an improved therapeutic success and overall median survival (3.7 versus 2.0 months) with percutaneous stents, but with more major complications (61% vs 35%) (Pinol 2002). The original RCT reported percutaneous insertion was associated with less success in relieving jaundice and a higher 30‐day mortality (Speer 1987). Endoscopic stenting remains the primary route of stent placement for these patients in most centres.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

All patients with biliary obstruction due to unresectable pancreatic carcinoma should receive palliative drainage via an endoscopic stent. The choice of stent depends on the expected survival of the individual patient; 10Fr polyethylene stents are the stent of choice in those with a short expected survival (three to six months). In those patients with longer expected survival, a metal expandable mesh stent should be used. The evidence, however, for choosing stent type according to life expectancy is weak. No conclusions on the choice of covered or uncovered stents, or metal alloy types can be made based on available literature.

Implications for research.

Further development on plastic stent composition to improve patency rates is needed to provide a more cost‐effective alternative to metal stents.

Randomised controlled trials are needed comparing:

metal stents to plastic stents in patients with life expectancy less than six months e.g. hepatic metastases, large tumour size, ECOG > 2)

covered to uncovered metal stents

stainless‐steel alloy (Wallstent) to nickel‐titanium alloy (Diamond) endoscopic metal stents

perflouro alkoxy (Double Layer) plastic to metal stents

An analysis of quality of life and cost effectiveness in these studies would be essential. Universal outcome measures would also allow clinicians to better compare interventions in this area.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 October 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2003 Review first published: Issue 1, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 March 2009 | New search has been performed | Updated, new studies included, tables & figures updated |

| 30 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 10 January 2006 | Amended | Minor update |

| 21 December 2005 | Amended | New studies found and included or excluded (seven abstracts reviewed ‐ five excluded (see characteristics of excluded studies) and two awaiting further details (see studies awaiting assessment)) |

Acknowledgements

Health Research Board of Ireland

Janet Lilleyman, Cochrane UGPD Group

Iris Gordon, Cochrane UGPD Group

Gemma Sutherington, Cochrane UGPD Group

Dr Cathy Bennett, Cochrane UGPD Group

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

1. randomised controlled trial.pt. 2. controlled clinical trial.pt. 3. randomized.ab. 4. placebo.ab. 5. drug therapy.fs. 6. randomly.ab. 7. trial.ab. 8. groups.ab. 9. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 10. humans.sh. 11. 9 and 10 12. exp Pancreatic Neoplasms/ 13. (pancrea$ adj5 neoplas$).tw. 14. (pancrea$ adj5 cancer$).tw. 15. (pancrea$ adj5 carcin$).tw. 16. (pancrea$ adj5 tumo$).tw. 17. (pancrea$ adj5 metasta$).tw. 18. (pancrea$ adj5 malig$).tw. 19. exp common bile duct neoplasms/ 20. (bile adj5 duct adj5 neoplas$).tw. 21. exp bile duct neoplasms/ 22. exp cholestasis/ 23. (bile adj5 duct adj5 obstruct$).tw. 24. cholestas?s.tw. 25. exp common bile duct diseases/ 26. exp jaundice, obstructive/ 27. (obstruct$ adj5 jaundice$).tw. 28. (malig$ adj10 bil$ adj10 obstruct$).tw. 29. (bil$ adj10 strictur$).tw. 30. or/12‐29 31. exp biliary tract surgical procedures/ 32. (bypass adj10 surg$).tw. 33. (operat$ adj10 bypass).tw. 34. (bil$ adj10 anastomosis).tw. 35. (bil$ adj10 bypass).tw. 36. exp choledochostomy/ 37. choledochostom$.tw. 38. choledochoduoden$.tw. 39. choledochojejun$.tw. 40. choledojejunostom$.tw. 41. hepaticojejun$.tw. 42. exp stents/ 43. stent$.tw. 44. endoprosthesis.tw. 45. Wallstent$.tw. 46. or/31‐45 47. 30 and 46 48. 11 and 47 49. limit 48 to yr="2005 ‐ 2008"

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Stent versus Surgery.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Technical failure | 3 | 306 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.31, 1.44] |

| 2 Therapeutic failure | 3 | 306 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.51, 1.92] |

| 3 Complications | 3 | 306 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.45, 0.81] |

| 4 30‐day mortality | 3 | 306 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.32, 1.04] |

| 5 Recurrent biliary obstruction prior to death / end of study | 2 | 256 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 18.59 [5.33, 64.86] |

Comparison 2. Metal versus Plastic Stent.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Technical failure | 6 | 584 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.55, 2.07] |

| 2 Therapeutic failure | 5 | 396 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.39, 4.57] |

| 3 Complications | 5 | 433 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.45, 1.90] |

| 4 30‐day mortality | 5 | 498 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.43 [0.79, 2.58] |

| 5 Recurrent biliary obstruction prior to death / end of study | 7 | 663 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.38, 0.62] |

Comparison 3. Teflon versus Polyethylene stent.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Technical failure | 5 | 441 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.34, 4.50] |

| 2 Therapeutic failure | 3 | 278 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.84 [1.31, 6.16] |

| 3 Complications | 5 | 441 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.91 [0.83, 4.36] |

| 4 30‐Day mortality | 5 | 441 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.77, 2.11] |

| 5 Recurrent biliary obstruction prior to death / end of study | 4 | 335 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.78, 1.24] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Andersen 1989.

| Methods | RCT via sealed envelopes | |

| Participants | >60 years of age Distal CBD stricture Fit for surgery Not for curative resection 86% had pancreatic CA | |

| Interventions | 7 / 10 Fr endoprosthesis Bypass surgery | |

| Outcomes | Median Survival Complications Treatment Failures Range of functioning time of endoprosthesis Median length of hospitalisation Quality of Life | |

| Notes | N=50 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | "Randomised by means of sealed envelopes" |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Sealed envelopes |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Neither arm |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient reporting of exclusions |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | Outcomes of interest incompletely reported |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Artifon 2006.

| Methods | RCT by computer‐generated random numbers. | |

| Participants | Pancreatic cancer with liver metastases Biliary obstruction Excluded if resectable or duodenal obstruction 30 had pancreatic cancer | |

| Interventions | Covered self‐expandable

metal stent (Shim‐HanaroStentTM, model MItech, 60x10mm)

OR Roux end to side hepatojejunostomy and gastrojejunostomy |

|

| Outcomes | Technical success Procedure‐related mortality Procedure‐related morbidity Early complications Late complications Readmisssion rate Survival (days) Cost of care | |

| Notes | N=30 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Random numbers |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear risk | % rather than raw data reported for some outcomes |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Benz 1998.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Inoperable malignant distal CBD obstruction 58% had pancreatic CA | |

| Interventions | Polyurethane stent Teflon Tannenbaum stent Hydrophillic polyurethane stent | |

| Outcomes | Time to stent dysfunction | |

| Notes | N=48 Abstract |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | Only described "no significant difference" in time to stent occlusion |

Carr Locke 1993.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | CBD obstruction by tumour 52% had pancreatic CA | |

| Interventions | Wallstent endoprosthesis 10‐11.5 Fr plastic stents | |

| Outcomes | Technical success 30‐day mortality Stent obstruction Medican time to obstruction | |

| Notes | N=163 Abstract |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear risk | Not all outcomes described |

Catalano 2002.

| Methods | RCT by central data centre | |

| Participants | Malignant CBD strictures >1cm distal to hilum Excluded if age <18 life expectancy < 1 month encephalopathy unable to pass stricture 78% had pancreatic CA | |

| Interventions | Tennenbaum teflon stent Cotton‐Leung polyethylene Antibiotic pre & post op | |

| Outcomes | Early complications Reduction in mean serum bilirubin at 1 month 30‐day mortality Median patency Mean 90‐day stent patency Stent migration | |

| Notes | N=106 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Randomly assigned by a central data coordinating center |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Centrally assigned |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | All randomized patients accounted for |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | Not all outcomes reported, no a priori outcomes described |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Costamagna 2000.

| Methods | RCT by computer‐generated list | |

| Participants | Malignant mid or distal CBD stricture Inoperable / unresectable No previous drainage procedures Excluded if hilar lesions 72% had pancreatic CA | |

| Interventions | Hydrophillic hydromer coated polyurethane Polyethylene Dilatation in all | |

| Outcomes | Medican survival Stent occlusion Median patency Clinical jaundice | |

| Notes | N=83 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computer‐generated randomization list |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | All reported |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear risk | A priori outcomes not described |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Davids 1992b.

| Methods | RCT by computer‐generated random numbers | |

| Participants | Irresectable malignancy at CBD Performance status > 3 ECOG No previous drainage procedures 70% had pancreatic CA | |

| Interventions | Self‐expanding metal Wallstent 10 Fr Polyethylene stent with side‐holes | |

| Outcomes | Therapeutic success Early complications 30‐day mortality Overall patient survival Median survival Median period of patency Stent occlusion Incremental costs Mean number of ERCPs | |

| Notes | N=105 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computer‐generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | No patients were lost to follow‐up |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcomes reported |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Dua 2006.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Nonhilar, extrahepatic, malignant bile‐duct stricture Excluded if resectable lesions, prior stents/surgery, and duodenal obstruction. 17 had pancreatic cancer | |

| Interventions | 10F Tannenbaum OR 10F Tannenbaum stent with antireflux valve | |

| Outcomes | Technical success Mortality Median patency (days) Mean bilirubin Complications | |

| Notes | N=60 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Reports of all drop‐outs, lost cases |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcomes reported |

England 2000.

| Methods | RCT by computer‐generated random numbers in sealed envelopes | |

| Participants | Malignant CBD stricture suitable for stenting Excluded if previous intervention / lesion at hilum / metastatic disease / unlikely to survive procedure 70% pancreatic CA | |

| Interventions | 10Fr Cotton‐Leung 10Fr Tannenbaum prosthesis (6 had combined procedure) | |

| Outcomes | Technical success Therapeutic success Early complications 30‐day mortality Median patency Median survival Stent exchange | |

| Notes | N=134 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computer generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Sealed envelopes |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Full description of drop‐outs |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All a priori outcomes described |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Howell 2006.

| Methods | RCT by remote telephone system | |

| Participants | Biliary strictures due to unresectable malignancy occurring at least 2cm below the bifurcation | |

| Interventions | 6mm nitinol SEMS, OR 10mm nitinol SEMS, OR 10mm uncoated Wallstent | |

| Outcomes | Placement success, Malpositioning, Post‐placement complication, Stent patency, Number of ERCPs, Mortality | |

| Notes | N=183 Abstract |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Remote telephone |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | All follow‐up not reported |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | Not all outcomes reported in abstract |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Abstract only |

Isayama 2004.

| Methods | RCT by random numbers | |

| Participants | Unresectable malignant biliary obstruction Excluded if hilar disease, ECOG < 3 | |

| Interventions | Polyurethane‐covered Ultraflex Diamond wallstent vs Uncovered | |

| Outcomes | Stent obstruction Patient death Technical success Complications Survival Late complications Cost‐effectiveness | |

| Notes | N=112 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computer‐generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Computer generated |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | All follow‐up data described |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcomes described |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Kaassis 2003.

| Methods | RCT by sealed envelopes | |

| Participants | Jaundice due to malignant distal CBD stricture Contraindication to surgery Exclusion: ASA >4, Hilar lesion, duodenal obstruction, prior procedures 74% pancreatic CA | |

| Interventions | Metal Wallstent 10Fr Tannenbaum stent | |

| Outcomes | Complications Obstruction Median stent patency Actuarial occlusion rate Episodes of stent occlusion Days of hospitalisation Medican overall survival Cost of treatment | |

| Notes | N=118 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Sealed envelopes |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Missing outcomes not described per group of randomisation |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | % only described, outcomes incomplete |

Kastinelos 2006.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Unresectable malignant distant biliary stricture No prior stent insertion, and no previous surgical or radiologic procedures performed on the biliary tree. 25 had pancreatic cancer | |

| Interventions | Tannenbaum stent OR Self‐expanding metal stent | |

| Outcomes | Technical success Complications Median stent patency Medican survival Number of ERCPs required | |

| Notes | N=47 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computer‐generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Sealed envelopes |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | All described |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcomes reported |

Kastinelos 2008.

| Methods | RCT by computer generated numbers | |

| Participants | Malignant biliary obstruction Inoperable Life‐expectancy at least 3 months 41 had pancreatic cancer | |

| Interventions | Hanaro uncovered SEMS OR Luminex uncovered SEMS | |

| Outcomes | Technical success Complications Stent occlusion Mortality Median survival Median patency | |

| Notes | N=89 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computer‐generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Sealed envelopes |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | All patients described |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcomes reported |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Knyrim 1993.

| Methods | RCT by computer‐generated random number chart | |

| Participants | Distal inoperable malignant CBD obstruction 69% pancreatic CA | |

| Interventions | 11.5 Fr Polyethylene stent Metal Wallstent (11 treated with combined approach) | |

| Outcomes | Technical success Early stent failure Bilirubin 30‐day mortality Stent failure > 30 days Cholangitis No of re‐interventions Time in Hospital Mean costs of complications Mean overall costs | |

| Notes | Quality moderate N=62 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computer‐generated random number chart |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Inadequate description of lost patients |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcomes reported |

Landoni 2000.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Malignant obstruction of the biliary tree (irresectable / inoperable) 39% pancreatic cancer | |

| Interventions | 10Fr standard plastic 10Fr polyurethane | |

| Outcomes | Therapeutic success Duration of patency | |

| Notes | Quality poor N=38 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Not described |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear risk | Outcomes not described in advance |

Moses 2006.

| Methods | RCT by sealed envelopes | |

| Participants | Extrahepatic biliary obstruction by any malignant process, extending to no more proximal than 1cm below the common hepatic ductal bifurcation | |

| Interventions | Wallstent covered biliary prosthesis, OR 10F Amsterdam‐style plastic stent | |

| Outcomes | Technical success, Mean procedure & recovery times, Median time to obstruction, Rates of obstruction at 3 months, Rates of obstruction at 6 months, Reintervention rate, Cholestatic symptoms at 1 & 3 & 6 months, Mean lab results at 1,3,6 months, Adverse events | |

| Notes | N=85 Abstract |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Sealed envelopes |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Missing data, reasons not reported |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcomes reported |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Industry‐funding declared, abstract only |

Prat 1998a.

| Methods | RCT by technical coordinator in blocks of six | |

| Participants | Jaundice 2nd to distal malignant CBD stricture No previous attempts ar drainage ECOG <2 / ASA <3 Inoperable based on age / tumor extension 65% had pancreatic CA | |

| Interventions | 11.5Fr Polyethylene stent changed PRN Plastic stent changed every 3 months Self‐expanding metal stent | |

| Outcomes | Therapeutic success % Decrease in serum bilirubin Procedure‐related mortality / morbidity Median survival Time to first eposide of stent dysfunction % of patients dying with jaundice / sepsis Cumulative days in hospital per patient Number of ERCPs per patient Overall costs per patient | |

| Notes | N=101 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Remote technical coordinator |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Not described |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcomes described |

Rosch 1997.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Malignant distal biliary obstruction Inoperable / Iresectable | |

| Interventions | Metal Wallstent Plastic stent with side‐holes Plastic stent without side‐holes | |

| Outcomes | Stent failure rates at 4 months | |

| Notes | N=75 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Not described |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | Outcoems not described completely |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Abstract only |

Schilling 2003.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | malignant mid or distal bile duct strictures 70% had pancreatic cancer | |

| Interventions | 10F polyurethane stent Teflon Tannenbaum stent Hydrophilic hydromer‐coated polyurethane stent. | |

| Outcomes | Technical success Therapeutic success Complications Stent patency Survival | |

| Notes | N=120 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computer‐generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Sealed envelopes |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Not stratified by randomization group |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcomes reported |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Shah 2003.

| Methods | RCT by sealed envelopes | |

| Participants | Malignant extrahepatic biliary obstruction 2cm distal to the hepatic bifurcation who were poor candidates for curative resection 108 had pancreatic cancer |

|

| Interventions | 10mm Wallstent, OR 10mm Gianturco‐Rosch Spiral Z‐stent | |

| Outcomes | Technical success, Stent occlusion, Median days to occlusion, Median overall stent patency, Median survival days, Mechnisms of stent occlusion | |

| Notes | N=145 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Opaque mixed envelopes |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | All patients described |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcomes reported |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Industry‐funded |

Shepherd 1988.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Malignant obstruction of distal bile duct Not suitable for curative surgery Technically suitable for surgical bypass 78% had pancreatic cancer | |

| Interventions | Surgical bypass 10Fr polyethylene stent Cephalosporins | |

| Outcomes | Technical success Median duration of hospital stay for those alive > 30 days Number of patients alive > 30 days 30‐day mortality Procedural complications Overall survival in days Relief of jaundice Number of re‐admissions Total hospital stay | |

| Notes | N =52 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | All described |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcomes described |

Smith 1994.

| Methods | RCT by computer minimisation at central control | |

| Participants | Distal CBD malignant obstruction Serum bilirubin > 100mmol/L Not appropriate for curative resection 64% had pancreatic cancer | |

| Interventions | 10Fr Teflon stent Surgical bypass All received antibiotics pre post op | |

| Outcomes | Procedural success Therapeutic success Complications 30‐day mortality Length of hospital stay Recurrent obstruction Survival | |

| Notes | N=204 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Compouter‐generated |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Central control |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | No |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | All described |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcomes described |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Soderlund 2006.

| Methods | RCT via opaque, sealed envelope and random table technique | |

| Participants | Inoperable malignant bile duct obstruction Jaundice 78 had pancreatic cancer | |

| Interventions | 10Fr polyethylene OR Self‐expandable metal covered Wallstent | |

| Outcomes | Technical success Theraputic success Complications Median survival Medican stent patency | |

| Notes | N=100 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Random table technique |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Opaque, sealed envelopes |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | All described |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcomes reported |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Industry‐sponsored |

Terruzzi 2000.

| Methods | RCT by computer blinding scheduling | |

| Participants | Jaundice 2nd to untreated malignancy of distal bile duct Not suitable for surgery 38 had pancreatic CA | |

| Interventions | Tannenbaum Teflon stent (no side‐holes) Polyethylene stent with side‐holes All got Cefuroxime pre‐op | |

| Outcomes | Complications Median duration of stent patency Stent occlusion Median survival | |

| Notes | N=57 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Blinding by computer |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | All described |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcomes described |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Industry‐supported |

Tringali 2003.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Jaundice 2nd to malignant middle / distal CBD obstruction No hilar strictures 80% had pancreatic cancer Inoperable | |

| Interventions | Perflourooloxy without side‐holes Polyethylene with side‐holes | |

| Outcomes | Stent patent to end‐point Mean survival Mean time to stent clogging Number of patients with stent dysfunction | |

| Notes | N=120 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | |

van Berkel 1998.

| Methods | RCT by computer generated random numbers in sealed envelopes | |

| Participants | Distal biliary obstruction due to unresectable malignancy without previous drainage procedure 65% pancreatic mass | |

| Interventions | 10Fr polyethylene with side‐holes 10Fr Teflon with side‐holes | |

| Outcomes | Technical success Biliary drainage Procedure‐related complications 30‐day mortality Median survival Stent dysfunction Median stent patency Mean number of ERCPs per patient Cumulative patency of stents | |

| Notes | N=84 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | computer generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Sealed envelopes |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | All described |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | All outcomes reported |

van Berkel 2003.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | unresectable distal malignant bile duct stricture without a previous drainage procedure 86% had pancreatic cancer | |

| Interventions | Hydrophilic polymer‐coated polyurethane (HPCP) stents Amsterdam‐type polyethylene (PE) | |

| Outcomes | Technical success Stent dysfunction Median stent patency Early complications | |

| Notes | N=100 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | All reported |

van Berkel 2004.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | distal malignant bile duct obstruction. 95% pancreatic CA Irresectable | |

| Interventions | Tannenbaum design stent with a stainless steel mesh and an inner Teflon coating, Amsterdam‐type PE stent | |

| Outcomes | Early complications Stent dysfunction Median stent patency Median survival | |

| Notes | Quality moderate N=60 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computer‐genrated |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | All addressed |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

CA: cancer CBD: common bile duct ECOG: European Clinical Oncology Group ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram PRN: "pro re nata" (Latin ‐ when necessary) RCT: randomised controlled trial

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Arguedas 2002 | Non‐RCT |

| Bottger 1992 | Non‐RCT |

| Byung 1997 | Non‐RCT |

| Davids 1992a | Duplicate Davids 1992b |

| Dowsett 1989 | Mostly hilar lesions |

| Dowsett 1989b | Duplicate Shepherd 1994 |

| Dumonceau 2000 | Metal stents only |

| Foco 1996 | Non‐RCT |

| Groen 1987 | Non‐RCT |

| Hatfield 1982 | Intervention any biliary drainage |

| Hyoty 1990 | Non‐RCT |

| Isayama 2000 | Duplicate Isayama 2004 |

| Knyrim 1992 | Duplicate Knyrim 1993 |

| Lawrie 1996 | Delivery methods only of stent |

| Leung 1992 | Non‐RCT , benign disease |

| Liliemoe 1999 | Non‐RCT, surgery only |

| Linder 2005 | Non‐RCT |

| Maosheng 2001 | Non‐RCT |

| Martin 1997 | Duplicate of England 2000 |

| Matasuda 1991 | Non‐RCT |

| Pedersen 1993 | Non‐RCT |

| Pedersen 1998 | Non‐RCT |

| Prat 2004 | Non‐RCT |

| Raikar 1996 | Non‐RCT |

| Rosch 1998 | Non‐RCT |

| Scholf 1994 | Non‐RCT |

| Sciume 2004 | Contains patients with benign disease |

| Siegel 1986 | Non‐RCT |

| Sonnenfeld 1986 | Non‐RCT |

| Suih 2000 | Metal only |

| Sung 1993 | Benign disease |

| Sung 1994 | Non‐RCT |

| van Berkel 2005 | Non‐RCT |

| Wagner 1993 | Hilar lesions only |

| Wasan 2004 | Surgically resectable |

Differences between protocol and review

None

Contributions of authors

Moss A: protocol development, eligibility and quality assessment, data extraction and analysis, drafting of final review, updating the review. Morris E: protocol development, eligibility and quality assessment, data extraction and analysis, drafting of first published version of review. MacMathuna P: clinical background & advice, assessment of eligibility and quality, drafting of first published version of review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Ireland.

Academic Unit of Epidemiology, University of Leeds, UK.

External sources

Health Research Board of Ireland Cochrane Fellowship, Ireland.

Declarations of interest

None known

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Andersen 1989 {published data only}

- Andersen JR, Sorensen SM, Kruse A, Rokkjaer M, Matzen P. Randomised trial of endoscopic endoprosthesis versus operative bypass in malignant obstructive jaundice. Gut 1989;30(8):1132‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Artifon 2006 {published data only}