Abstract

Background

People presenting with agitated or violent behaviour thought to be due to severe mental illness may require urgent pharmacological tranquillisation. Several preparations of olanzapine, an antipsychotic drug, are now being used for management of such agitation.

Objectives

To estimate the effects of intramuscular, oral‐velotab, or standard oral olanzapine compared with other treatments for controlling aggressive behaviour or agitation thought to be due to severe mental illness.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (Issue 1, 2002), The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (November 2004) and reference lists. We contacted authors of trials and the manufacturers of olanzapine.

Selection criteria

Randomised clinical trials comparing oral‐velotab or intramuscular, or standard oral olanzapine to any treatment, for agitated or aggressive people with severe mental illnesses.

Data collection and analysis

We reliably selected, quality assessed and data extracted studies. For binary outcomes we calculated a fixed effects Risk Ratio (RR) and its 95% Confidence Interval (CI) with a weighted Number Needed to Treat/Harm statistic (NNT/H). For continuous outcomes, we preferred endpoint data to change data and synthesised non‐skewed data from valid scales using a weighted mean difference (WMD).

Main results

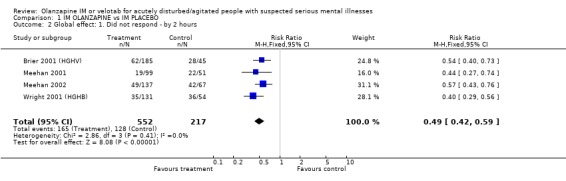

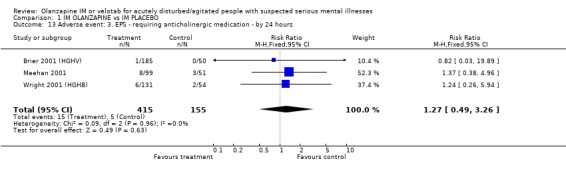

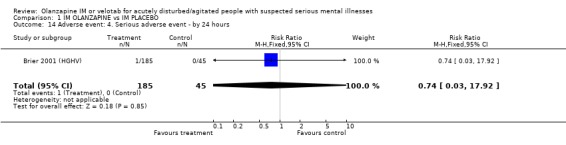

Four trials compared olanzapine IM with IM placebo (total n=769, 217 allocated to placebo). Fewer people given olanzapine IM had 'no important response' by 2 hours compared with placebo (4 RCTs, n=769, RR 0.49 CI 0.42 to 0.59, NNT 4 CI 3 to 5) and olanzapine IM was as acceptable as placebo (2 RCTs, n=354, RR leaving the study early 0.31 CI 0.06 to 1.55). When compared with placebo, people given olanzapine IM required substantially fewer additional injections following the initial dose (4 RCTs, n=774, RR 0.48 CI 0.40 to 0.58, NNT 4 CI 4 to 5). Olanzapine IM did not seem associated with extrapyramidal effects (4 RCT, n=570, RR experiencing any adverse event requiring anticholinergic medication in first 24 hours 1.27 CI 0.49 to 3.26).

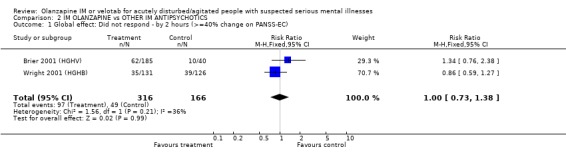

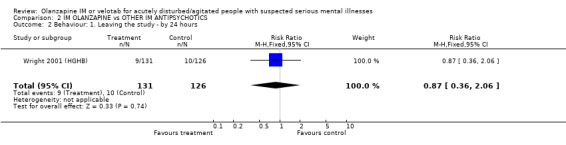

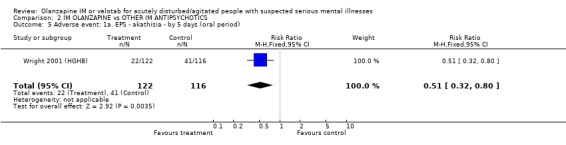

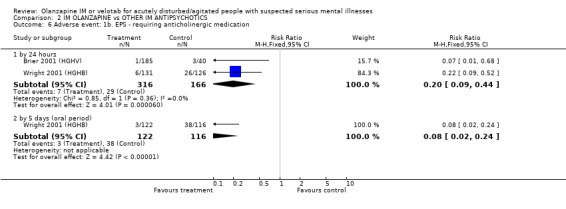

Two trials compared olanzapine IM with haloperidol IM (total n=482, 166 allocated to haloperidol). Studies found no differences between olanzapine IM and haloperidol by 2 hours for the outcome of 'no important clinical response' (2 RCTs, n= 482, RR 1.00 CI 0.73 to 1.38) neither was there a difference for needing repeat IM injections (2 RCTs, n=482, RR 0.99 CI 0.71 to 1.38). More people on haloperidol experienced akathisia over the five day oral period compared with olanzapine IM (1 RCT, n=257, RR 0.51 CI 0.32 to 0.80, NNT 6 CI 5 to 15) and fewer people allocated to olanzapine IM required anticholinergic medication by 24 hours compared with those given haloperidol IM (2 RCTs, n= 432, RR 0.20 CI 0.09 to 0.44, NNT 8 CI 7 to 11).

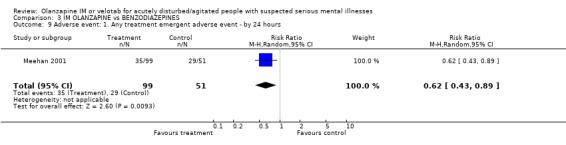

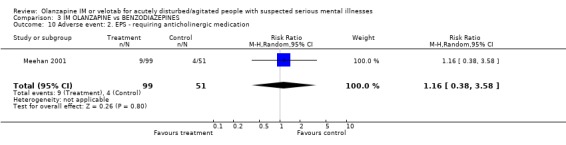

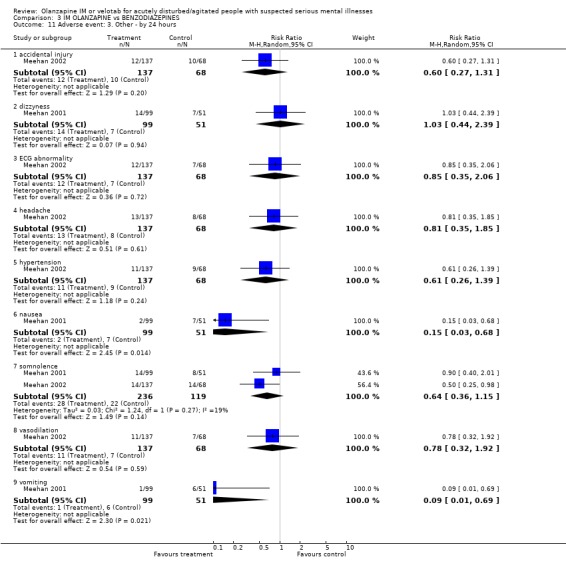

Two trials compared olanzapine IM with lorazepam IM (total n=355, 119 allocated to lorazepam). For the outcome of 'no important clinical response' , there was no difference between people given olanzapine IM and those allocated to lorazepam at 2 hours (2 RCTs, n=355, RR 92 CI 0.66 to 1.30) but fewer people allocated to olanzapine IM required additional injections by 24 hours compared with those on lorazepam IM (2 RCTs, n=355, RR 0.68 CI 0.49 to 0.95, NNT 10 CI 6 to 59). People receiving IM olanzapine were less likely to experience any treatment emergent adverse events, than those on lorazepam (1 RCT, n=150, RR at 24 hours 0.62 CI 0.43 to 0.89, NNT 5 CI 4 to 17) and over the same time period there were no clear differences in the use of anticholinergic medication between groups (1 RCT, n=150, RR 1.16 CI 0.38 to 3.58).

No studies reported outcomes related to hospital and service use. Nor did any report on issues of satisfaction with care or suicide, self‐harm or harm to others. No studies evaluated the oro‐dispersable form of olanzapine.

Authors' conclusions

Data relevant to the effects of olanzapine IM are taken from some studies that may not be considered ethical in many places, all are funded by a company with a pecuniary interest in the result. These studies often poorly report outcomes that are difficult to interpret for routine care. Other important outcomes are not recorded at all. Nevertheless, olanzapine IM probably has some value in helping manage acute aggression or agitation, especially where it is necessary to avoid some of the older, better, known treatments. Olanzapine causes fewer movement disorders than haloperidol and more than lorazepam. The value of the oro‐dipersable velotab preparation is untested in trials. There is a need for well designed, conducted and reported randomised studies in this area. Such studies are possible and, we argue, should be designed with the patient groups and clinicians in mind. They should report outcomes of relevance to the management of people at this difficult point in their illness.

Keywords: Humans; Aggression; Antipsychotic Agents; Antipsychotic Agents/administration & dosage; Benzodiazepines; Benzodiazepines/administration & dosage; Haloperidol; Haloperidol/administration & dosage; Injections, Intramuscular; Lorazepam; Lorazepam/administration & dosage; Olanzapine; Psychotic Disorders; Psychotic Disorders/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Olanzapine IM or velotab for acutely disturbed/agitated people with suspected serious mental illnesses

Sometimes it is necessary to use medication to help stop aggressive or agitated behaviour that is thought to be caused by serious mental illness. Two ways of doing this are to give olanzapine as an injection into the muscle (IM ) or as a swiftly dissolved oral preparation (orodispersable or velotab). In this review, we attempted to summarise the effects of these approaches as seen from within evaluative randomised studies. Data relevant to the effects of olanzapine IM are taken from some studies that may not be considered ethical in many places, all are funded by a company which has a pecuniary interest in the result. In addition, these studies often poorly report outcomes that are difficult to interpret for routine care. Other important outcomes are not recorded at all. Nevertheless, olanzapine IM probably has some value in helping manage acute aggression or agitation, especially where some of the older better known treatments cannot be given. Olanzapine causes fewer movement disorders than haloperidol and more than lorazepam. The value of the velotab preparation is untested in trials.

Background

Psychiatric illnesses can present with acutely agitated behaviour or even violence, and in a psychiatric ward one of the common cause is schizophrenia or delusional syndromes (Grassi 2001). Violent or acutely disturbed people pose a risk to themselves and to others (Thomas 1992). Ideally, in order to ensure a safe and therapeutic environment, attempts should be made to calm the patient through either verbal de‐escalation or intensive nursing techniques. Behaviour, however, may be too disturbed for such 'verbal tranquillisation', and further action, in the form of rapid pharmacological tranquillisation, may be needed.

Various drug regimens are used in the emergency situation. A mix of benzodiazepine and haloperidol, or benzodiazepine alone are common (Hughes 1999), but haloperidol can be used alone (Chouinard 1993), as can flunitrazepam (Dorevitch 1999), or zuclopenthixol acetate (Chin 1998, Amdisen 1987). One survey from the USA (Binder 1999) questioned the medical directors of 20 emergency rooms and found their preferred drug management of aggressive people to be a haloperidol‐lorazepam mix. In 1993, a similar UK survey of clinicians' preferences found chlorpromazine to be the most common choice (Cunnane 1994). A survey of emergency prescribing in a general psychiatric hospital in South London showed that rapid medical tranquillisation had to be used 102 times over a period of 160 days (Pilowsky 1992). Eight different drugs were used, amongst which diazepam, haloperidol and droperidol were the most common. A recent survey of the emergency rooms in Rio de Janeiro, however, found that a haloperidol‐promethazine mixture was commonly used for emergency intramuscular (IM) sedation of severely agitated/aggressive people (70‐100 people with suspected psychotic illness/week/3.5m) (Huf 2000).

Ideally drug(s) used in urgent treatment of acute agitation or violence should have a swift onset of effect, good tranquillizing or sedative properties, safe and minimal or no adverse effects.

Olanzapine is currently used for the treatment of schizophrenia and psychosis. Limited data summarised in systematic reviews suggest the oral form of olanzapine to be equally as effective as haloperidol for the treatment of symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations. It causes less movement disorders but more weight gain (Duggan 2002). There have been case reports of olanzapine use being associated with neuroleptic malignant syndrome (Johnson 1998, Stanfield 2000).The pharmaceutical company producing olanzapine state that the intramuscular preparation is effective for rapid control of agitation and disturbed behaviour in people with schizophrenia, and that the advantage of using olanzapine in its intramuscular form is that its onset of action from injection is only 15‐45 minutes compared with 5‐8 hours following oral administration. Another new form of olanzapine is the velotab. Velotab is rapidly dispersible when placed in the mouth, so it can be easily swallowed, but removal of intact tablet from the mouth is difficult. A mean time for total disintegration of velotab is about one minute (Chue 2000), and uncontrolled studies report and suggest that velotab preparation may have some benefits over coated tablets for acutely ill and non‐compliant people with schizophrenia (Kinon 2001).

Technical background of olanzapine Olanzapine (Zyprexa), 2‐methyl‐4‐(4‐methyl‐1‐piperazinyl)‐10H‐thieno[2,3,‐b][1,5,] benzodiazepine, is a newer antipsychotic agent of thienobenzodiazepine class. It has some structural similarities to clozapine. Olanzapine has affinity for number of receptors, including dopaminergic, serotonergic, adrenergic, histaminergic and muscarinic receptors. Olanzapine binds to the dopamine D1, D2, D3 and D4, with relatively high affinity to D4 (Seeman 1993). Olanzapine is more potent in binding to 5‐HT 2A receptors as compared with D2 receptors (Bymaster 1996). It also has high affinity to 5‐HT 2A, 5‐HT 2C, 5‐HT 3 receptors and moderate affinity to 5‐HT 7. (Roth 1994, Bymaster 1996). Currently olanzapine is only available for oral and intramuscular use. IM olanzapine is available as powder for solution containing 10mgs of olanzapine. The maximum plasma concentration after IM olanzapine is 5 times higher than oral olanzapine and occurs in 15‐45 minutes. Velotab is an orodispersible tablet that also contains gelatin, aspartame, mannitol and parahydroxybenzoates. It is available as 5mg and 10mg tablets. The mean plasma concentration time curve for velotab is similar to that of conventional olanzapine.

Objectives

1. To estimate the effects of intramuscular olanzapine when compared with other treatments for people with aggressive behaviour/ agitation thought to be due to severe mental illness.

2. To estimate the effects of oral velotab or standard olanzapine when compared with other treatments for people with aggressive behaviour/ agitation thought to be due to severe mental illness.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised controlled trials. Where a trial was described as 'double‐blind' but it was implied that the study was randomised, these trials were included in a sensitivity analysis. If there was no substantive difference within primary outcomes (see 'Types of outcome measures') when these 'implied randomisation' studies were added, then they were included in the final analysis. If there was a substantive difference, only clearly randomised trials were utilised and the results of the sensitivity analysis described in the text. Quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week, were excluded.

Types of participants

We included studies if they involved people with suspected severe mental illness presenting with acute aggression or violent behaviour to any psychiatric setting (e.g. inpatient/outpatient clinics, community centres, day hospitals) or an emergency setting attended by psychiatric teams (e.g. Accident and Emergency). Studies were excluded if solely focusing on management of aggression at non‐psychiatric settings. We included any people with acute psychotic illnesses such as in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, affective disorders, manic phase of bipolar disorder or brief psychotic episode, irrespective of age or sex. Studies including people whose agitation was linked to drug or alcohol misuse as well as suspected severe mental illness were also included. Studies were excluded, however, if solely focusing on those with agitation or aggression due to substance misuse or personality disorder and not psychosis.

We used a broad definition of acutely ill. For the purposes of this review, 'acutely ill' was defined as where the majority of participants had been described as experiencing an 'acute illness/relapse/exacerbation' or had recently had new positive symptoms or an exacerbation of these symptoms. The so‐called positive symptoms are delusions, hallucinations, formal thought disorders and motor over activity.

Types of interventions

1. Olanzapine: any dose, given by intramuscular injection 2. Olanzapine velotab: any dose

Compared with: 1. Other antipsychotics (divided into atypical and typical): any dose, given by intramuscular injection 2. Other antipsychotics (divided into atypical and typical): any dose, given orally 3. Benzodiazepines: any dose, given by intramuscular injection 4. Benzodiazepines: any dose, given orally 5. Combination drug treatments: any dose, given by intramuscular injection 6. Combination drug treatments: any dose, given orally 7. Verbal tranquillisation techniques 8. Placebo, or 9. No treatment

Types of outcome measures

Outcomes were divided into immediate (within two hours), short term (>2 hours ‐ 24 hours) and medium term (>24 hours ‐ two weeks) and long term (beyond two weeks).

N.B. Trials that provided data for this review reported outcomes for intervals * Primary outcomes for immediate and short term.

Primary outcomes

1. Behaviour 1.1 Tranquillisation (feeling of calmness and/or calm, non‐sedated behaviour)

1.2 Aggression

1.3 Injury to others

1.4 Compulsory administrations of treatment

1.5 Changes in compliance (as measured in the studies)

2. Sedation (sleepiness and drowsiness)

3. Symptoms 3.1 Clinically important reduction of symptoms as defined by each study

4. Adverse effects 4.1 Measured acceptance of treatment

5. Hospital and service outcome 5.1 Duration of hospital stay

6. Satisfaction with care 6.1 Recipient of care 6.2 Informal care givers 6.3 Measured acceptance of treatment

Secondary outcomes

1. Behaviour 1.2 Self‐harm, including suicide 1.3 Use of further doses of medication 1.4 Clinically important improvement in self care, or degree of improvement in self care

2. Symptoms 2.1 Any reduction in severity of symptoms 2.2 Increase in symptoms 2.3 Degree of change in severity of symptoms 2.4 Severity of symptoms when discharged from hospital

4. Adverse effects 4.1 Incidence of side effects, general or specific 4.2 Leaving the study early 4.3 Use of antiparkinsonian treatment

5. Hospital and service outcome 5.1 Hospitalisation of people in the community 5.2 Severity of symptoms when dismissed from hospital (was readmission needed in the month after) 5.3 Changes in hospital status (for example, changes from informal care to formal detention in care, changes of level of observation by ward staff and use of secluded nursing environment)** 5.4 Changes in services provided by community teams

6. Satisfaction with care 6.1 Professional carers 6.2 Leaving the study early

7. Sudden and unexpected death

8. Economic outcomes

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

1.The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (CENTRAL, Issue 1, 2002)

We searched this using the phrase:

(Olanzapine* or "LY 170053" or Zyprexa or velotab)

2 The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Register (February 2002 and November 2004)

We searched the title, abstract and index terms fields in the Cochrane Schizophrenia Groups register using the terms:

{[(*olanzapine* or *LY 170053* or *Zyprexa* or *velotab*) in abstract or title or index terms of REFERENCE] or [olanzapine in interventions of STUDY]}

Searching other resources

1. Hand searching We searched reference lists of included and excluded studies for additional relevant trials.

2. Requests for additional data 2.1 We contacted the Medical Information Centre of Eli Lilly, the company which markets olanzapine, for published and unpublished data on the drug.

2.2 We also contacted authors of relevant studies to enquire about other sources of relevant information.

Data collection and analysis

1. Selection of trials Two reviewers (RB, MF) inspected the citations identified in the search outlined above, working independently. Potentially relevant studies were then ordered and reassessed for inclusion and methodological quality. Any disagreement was discussed and reported.

2. Assessment of quality Again working independently, the reviewers allocated trials to three quality categories, as described in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (Alexander 2004). When disputes arose as to which category a trial should be allocated to, we attempted resolution by discussion. When this was not possible, we allocated these studies to Category C until further details became available. Only trials in Category A or B are included in the review.

3. Data management 3.1 Data extraction We (RB, MF), extracted data, again working independently of each other. Where further clarification was needed we contacted authors of trials to provide missing data.

3.2 Intention to treat analysis We excluded data from studies where more than 50% of participants in any group were lost to follow up (this did not include the outcome of 'leaving the study early'). In studies with less than 50% dropout rate, we considered people leaving early to have had the negative outcome, except for adverse effects such as death. Regarding the outcomes of 'aggression', 'self harm' and 'harm to others', as they are major risks of non‐treated acute psychotic illness, we considered 5% of the people leaving the study early to have had a negative outcome in these three areas.

We analysed the impact of including studies with high attrition rates (25‐50%) in a sensitivity analysis. If inclusion of data from this group did result in a substantive change in the estimate of effect, we did not add this data to trials with less attrition, but presented them separately.

4. Data analysis 4.1 Binary data For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the fixed effects risk ratio (RR) and its confidence interval (CI). Where possible, we also calculated the weighted number needed to treat/harm statistic (NNT/H), and its confidence interval (CI). If we found heterogeneity (see section 5) we used a random effects model.

4.1.1 Valid scales: We included binary data from rating scales only if the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000) and the instrument was either a self‐report or completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist).

4.2 Continuous data 4.2.1 Skewed data: continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, the following standards were applied to all data before inclusion: (a) standard deviations and means were reported in the paper or were obtainable from the authors, (b) when a scale started from the finite number zero, the standard deviation, when multiplied by two, was less than the mean (as otherwise the mean was unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution, (Altman 1996), (c) if a scale started from a positive value (such as PANSS which can have values from 30 to 210) the calculation described above was modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2SD>(S‐Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score. Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and end point and these rules can be applied to them. When continuous data are presented on a scale which includes a possibility of negative values (such as change on a scale), there is no way of telling whether data are non‐normally distributed (skewed) or not. It is thus preferable to use scale end point data, which typically cannot have negative values. If end point data were not available, the reviewers used change data, but they were not subject to a meta‐analysis, and were reported in the 'Additional data' tables.

4.2.2 Summary statistic: for continuous outcomes we estimated a fixed effects weighted mean difference (WMD) between groups. Again, if we found heterogeneity (see section 5) we used a random effects model.

4.2.3 Endpoint versus change data: where possible we presented endpoint data and if both endpoint and change data were available for the same outcomes then we reported only the former in this review.

4.3 Cluster trials Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby p values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997, Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we presented the data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra class correlation co‐efficients of their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will also present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intra‐class correlation co‐efficient (ICC) Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported it was assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

5. Investigation for heterogeneity Firstly, we considered all the included studies within any comparison to judge clinical heterogeneity. We then visually inspected the graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity and supplemented this using, primarily, the I‐squared statistic. This provides an estimate of the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance alone. Where the I‐squared estimate was greater than or equal to 75%, we interpreted this as indicating the presence of high levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). If inconsistency had been high, data would not have been summated, but we would have presented them separately and investigated reasons for heterogeneity.

6. Addressing publication bias Data from all included studies were entered into a funnel graph (trial effect against trial size) in an attempt to investigate the likelihood of overt publication bias (Egger 1997).

7. Sensitivity analyses The effect of including studies with high attrition rates was analysed in a sensitivity analysis. Where a trial was described as 'double‐blind' but implied that the study was randomised, these trials were also included in a sensitivity analysis.

8. General Where possible, reviewers entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for olanzapine.

Results

Description of studies

1. Excluded studies Most excluded studies were uncontrolled clinical trials where outcomes for the same people were compared before and after the use of olanzapine (Wright 1999a, Wright 1999b, Kinon 2001). Bergstrom 1999 included healthy people and not acutely disturbed participants, so we excluded this study.

2. Awaiting assessment No studies await assessment.

3. Included studies Four studies are included in this review (Brier 2001 (HGHV), Meehan 2001, Meehan 2002, Wright 2001 (HGHB)). All are sponsored by the drug company who make olanzapine IM (Eli Lilly & Co). All are described as randomised and double blind.

3.1 Duration All trials reported outcomes at 2 and 24 hours following first injection. Only Wright 2001 (HGHB) continued with oral olanzapine and reported at five days and so included some data on the follow on effects of olanzapine.

3.2 Size All included studies were multi‐centre and the number of people in the included studies ranged from 201 to 311. The total number of people randomised in the included studies was 1054.

3.3 Participants Wright 2001 (HGHB) and Brier 2001 (HGHV) included people with agitation and a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform or schizoaffective disorder. DSM IV criteria were used to confirm the diagnosis. Meehan 2002 only included people with the diagnosis of possible Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia or a combination. Meehan 2001 included participants suffering from either manic or mixed episode bipolar disorder, 52.3% of these participants had psychotic symptoms. Diagnosis was confirmed by using SCID III‐R in Meehan 2001, whilst DSM IV diagnostic criteria were used for the diagnosis of dementia.

Inclusion into the studies was also dependent on the initial agitation score. All four studies used PANSS‐Excited Component scale for the measurement of agitation and included participants with the minimal total score of 14 (maximum of 35) on the 5 item questionnaire with at least one individual score of 4 (1‐7 scale). All trials involved people of both sexes and ages ranged from 18 to 97 years.

3.4 Settings Three studies were set in hospital but Meehan 2002 used both inpatient as well as nursing home settings.

3.5 Interventions 3.5.1 Experimental drug Olanzapine was given by intramuscular injection (IM) and there were no studies on olanzapine velotab. Wright 2001 (HGHB) used fixed dose of IM olanzapine (10mgs) for all participants whilst all other included studies varied doses from 2.5mgs to 10 mgs per injection. In all studies a total of three doses of IM olanzapine were allowed.

3.5.2 Comparison drugs Brier 2001 (HGHV) and Wright 2001 (HGHB) used IM haloperidol intramuscularly (between 7.5mg and 22.5mg in 24 hours). Participants were given haloperidol 7.5mg injection and were allowed up to three injections in 24 hours. Lorazepam IM was used as the control in Meehan 2001 and Meehan 2002 with doses ranging from 1mg to 5mg in 24 hours.

3.6 Outcome measures For clinical outcomes, data were most frequently derived from continuous scales, presented as mean values with standard deviation. Trials used mostly published, validated rating scales. Eli Lilly designed one scale (Agitation Calmness Evaluation Scale). Clinical outcomes were measured using change from baseline in agitation/aggression, mental symptoms. Trialists tended to measure clinical improvement by means of categorical scales, measuring degrees of improvement defined a priori. Adverse events were monitored and other measures included the number of people needing antiparkinsonian drugs, extra intramuscular injection and additional benzodiazepines. None of the studies addressed hospital and service outcomes by presenting the number of people substantially improved and discharged before the end of the trial. No study addressed economic evaluation or satisfaction with care when using olanzapine as compared with other medications.

3.6.1 Scales used

3.6.1.1 Behaviour 3.6.1.1.1 PANSS‐Excited Component (Kay 1986) A sub‐scale of the PANSS. 5 items includes poor impulse control, tension, hostility, uncooperativeness and excitement. Each item scored on 1‐7 scale.

3.6.1.1.2 Agitated Behaviour Scale ‐ ABS (Corrigan 1989) This is a 14 item scale used for monitoring agitation levels. This scale has been used in emergency department settings. The means and standard deviations for the Total Score and sub scale scores are based on samples of persons with traumatic brain injury treated during the acute phases of recovery on an inpatient, rehabilitation unit. A prospective sample of all patients with brain injuries, regardless of whether they were demonstrating agitation, revealed an overall mean ABS score of 21.01 and standard deviation of 7.35 for day shift nursing observations (Corrigan 1989). For clinical purposes, we consider any scores (Total or converted sub scale) 21 or below to be within normal limits, from 22 through 28 to indicate mild occurrence, 29 through 35 to indicate moderate, and more than 35 to be severe.

3.6.1.1.3 Cohen‐Mansfield Agitation Inventory (Cohen‐Mansfield 1989) A 37 item rating scale that rates frequency of behaviour from 0=never occurring to 6=several times an hour. 3.6.1.2 Mental state 3.6.1.2.1 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‐ BPRS (Overall 1962) A BPRS is used to assess the severity of a range of psychiatric symptoms, including psychotic symptoms. The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18 item scale is commonly used. Each item is defined on a seven‐point scale varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', scoring from 0‐6 or 1‐7. Scores can range from 0‐126, with high scores indicating more severe symptoms.

3.6.1.2.2 Mini‐Mental State Examination (Folstein 1975) The scale was primarily developed to detect dementia and focuses on the examinations of the cognitive functions. The scale tests orientation, registration, attention and concentration, recall, language and design copy. It takes 5‐10 minutes to administer this test and the maximum score is 30. Scores less then 23 are considered to reflect cognitive impairment.

3.6.1.2.3 Clinical Global Improvement‐Severity (Guy 1976) The CGI‐S scale requires the clinician to rate the severity of the participants illness at the time of assessment relative to the clinicians past experience with participants who have similar illnesses. Severity is recorded from 1(Normal, not ill at all) to 7 (extremely ill).

3.6.1.2.4 Neuropsychiatric Inventory/ Nursing Home Version (NPI/NH) (Wood 2000) The NPI‐NH is used for identifying residents with significant neuropsychiatric disturbances, but may be limited for use as an instrument for tracking behavioural changes. The domains of the NPI‐NH include 10 behavioural and 2 neuro‐vegetative items (delusions, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, depression, apathy, disinhibition, euphoria, irritability/lability, and aberrant motor disturbances). The score represents the symptom frequency (1= occasionally to 4= very frequently) and severity (1=mild to 3 = severe).

3.6.1.2.5 Young Mania Rating Scale (Young 1978) YMRS includes 11 items that are rated on the basis of participants self‐report as well as clinician's observation. The test covers manic symptoms but does not include pure depressive symptoms. Seven items are scored on 0‐4 scale and 4 items on 0‐8 scale. High score indicates worse severity of the illness.

3.6.1.3 Adverse effects 3.6.1.3.1 Simpson‐Angus Scale ‐ SAS (Simpson 1970) This ten item scale, with a scoring system of 0‐4 for each item, measures drug‐induced parkinsonism, a short‐term drug‐induced movement disorder. A low score indicates low levels of parkinsonism.

3.6.1.3.2 Barnes Akathisia Global Score (Barnes 1989) The scale is used for the assessment of the akathisia. It includes subjective (1 item, scored 0‐3) and objective assessment (2 items scored 0‐3) and global clinical assessment (1 item scored 0‐5).

4. Missing outcomes Economic outcomes and satisfaction with care were not addressed in any of the trials.

5. Pharmaceutical industry support All the studies were sponsored by Eli Lilly, the company that manufactures intramuscular olanzapine

Risk of bias in included studies

1. Randomisation All included studies were randomised trials but no trial reported details of the procedure by which this was undertaken. We contacted authors for further details of methods used to randomise but still no details are available regarding allocation concealment for any of the included studies.

2. Blinding at outcome In all studies trialists stated that they undertook blind evaluation of outcome, but none tested the quality of blinding.

3. Description of losses to follow‐up All studies reported the number of people leaving early. Meehan 2002 also gave the details if dropouts were due to adverse events or lack of efficacy, while Wright 2001 (HGHB) only gave details of dropouts due to adverse events. Brier 2001 (HGHV) reported 99.3% completion rate and included two of the people who had dropped out in the analysis. Meehan 2001 reported more dropouts from the group treated with lorazepam and placebo but reasons for this were not given.

4. Data reporting Most results were continuous and presented as mean values with standard deviations making clinical interpretation difficult. Meehan 2002, however, helpfully reported the exact number of people experiencing each outcome for adverse events. Overall data reporting did not comply with high standards.

Effects of interventions

1. The search Using our search strategy, we found 625 citations, including those supplied directly by Eli Lilly. Most citations were not involving intramuscalar or velotab olanzapine or were open clinical trials. We found four randomised controlled trials comparing intramuscular olanzapine with placebo, haloperidol or lorazepam. Only Kinon 2001 focused on oral velotab olanzapine and its effects on compliance but this study was open label and had to be excluded.

2. COMPARISON 1. IM OLANZAPINE versus PLACEBO We were able to include data from four trials for this comparison. These involved a total of 769 disturbed and agitated people, 217 of whom were allocated to placebo.

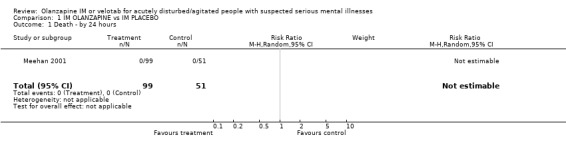

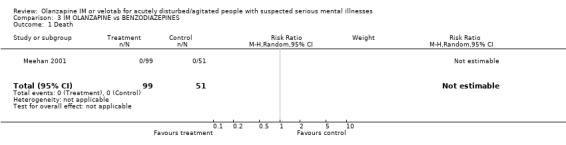

2.1 Death There were no reports of death in Meehan 2001.

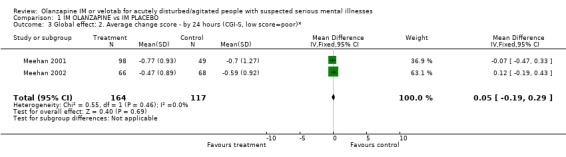

2.2 Global effect 2.2.1 Did not respond by two hours Trialists defined 'no important clinical response' as the number of people per treatment group who did not present at least a 40% reduction in symptoms measured by the PANSS‐EC score. Olanzapine IM was better than placebo for this outcome (4 RCTs, n=769, RR 0.49 CI 0.42 to 0.59, NNT 4 CI 3 to 5). 2.2.2 CGI severity at 24 hours The continuous scores of CGI‐S did not suggest any difference between groups (2 RCTs, n=281, WMD 0.05 CI ‐0.19 to 0.29).

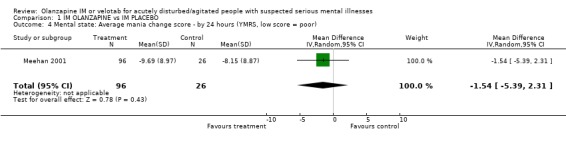

2.3 Mental state Meehan 2001 rates change in mania using the YMRS but found no clear difference between olanzapine IM and placebo (1 RCT, n=122, MD ‐1.54 CI ‐5.39 to 2.31).

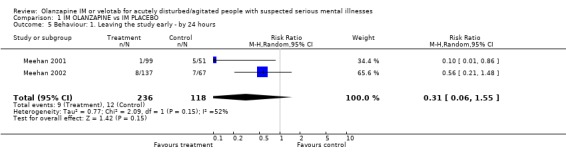

2.4. Behaviour 2.4.1 Leaving the study early There is no statistical difference between those on olanzapine and people allocated placebo for the outcome of leaving the study early (2 RCTs, n=354, RR 0.31 CI 0.06 to 1.55).

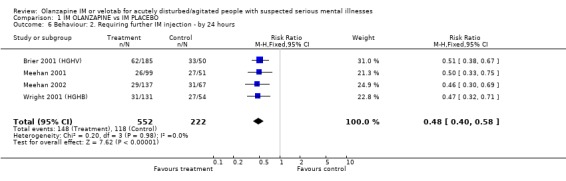

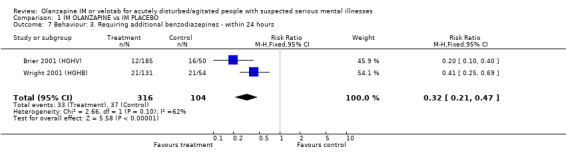

2.4.2 Requiring additional IM injections or benzodiazepines When compared with placebo, people given olanzapine IM required substantially fewer additional injections following the initial dose (4 RCTs, n=774, RR 0.48 CI 0.40 to 0.58, NNT 4 CI 4 to 5). In keeping with this, more people on placebo required additional injections of benzodiazepines as compared with those given olanzapine IM (2 RCTs, n=420, RR 0.32 CI 0.21 to 0.47, NNH 9 CI 8 to 12).

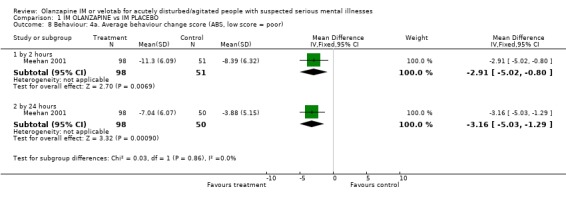

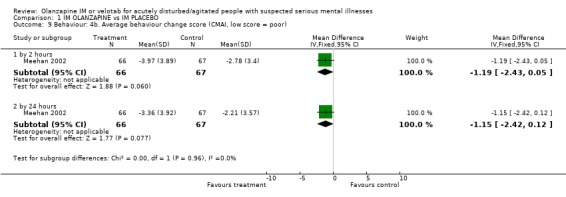

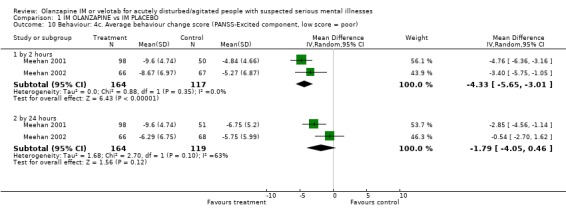

2.4.3 Average behaviour change scores At both the 2 and 24 hour time scale, people receiving olanzapine IM were less likely to be as agitated compared to baseline scores on the Agitated Behaviour Scale (2 hours, n=149, MD ‐2.91 CI ‐5.02 to ‐0.80; 24 hours n=50, MD ‐3.16 CI ‐5.03 to ‐1.29). Meehan 2002 used the Cohen‐Mansfield Agitation Inventory for rating behaviour but did not find results to be strikingly different between groups (2 hours, n=133, MD ‐1.19 CI ‐2.43 to 0.55; 24 hours, n=133, MD ‐1.15 CI ‐2.42 to 0.12). On the PANSS‐Excited component score at 2 hours people on olanazapine IM scored significantly less than those allocated to placebo (2 RCTs, n=281, WMD ‐4.33 CI ‐5.65 to ‐3.01). This significant difference disappeared at 24 hours.

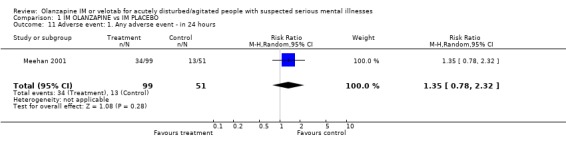

2.5 Adverse effects 2.5.1 Any adverse event in twenty four hours Meehan 2001 did not find any difference between people on placebo and those given olanzapine IM for the outcome of experiencing any adverse event in the first twenty four hours (n=150, RR 1.35 CI 0.78 to 2.32).

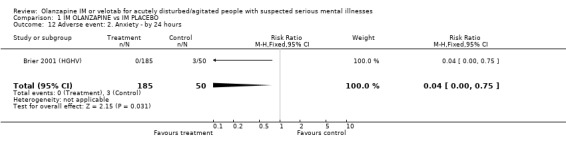

2.5.2 Anxiety More people taking placebo experienced anxiety than those on olanzapine IM (1 RCT, n=230, RR 0.04 CI 0.00 to 0.75, NNH 18 CI 17 to 67).

2.5.3 EPS ‐ requiring anticholinergic medication For the outcome of experiencing any adverse event requiring anticholinergic medication in the first twenty four hours, four trialists found no difference between people on placebo and those allocated and given olanzapine IM (n=570, RR 1.27 CI 0.49 to 3.26).

2.5.4 Serious adverse event Brier 2001 (HGHV) reported how one person in the olanzapine IM group experienced an ECG abnormality and anaemia. This was not statistically significant when compared with the placebo group (n=230, RR 0.74 CI 0.03 to 17.92).

2.6 Missing outcomes No studies reported outcomes related to hospital and service use. Nor did any report on issues of satisfaction with care or suicide, self‐harm or harm to others.

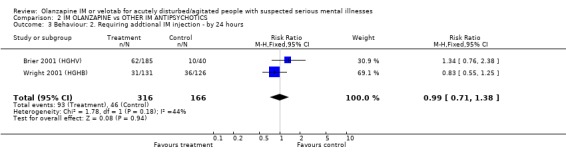

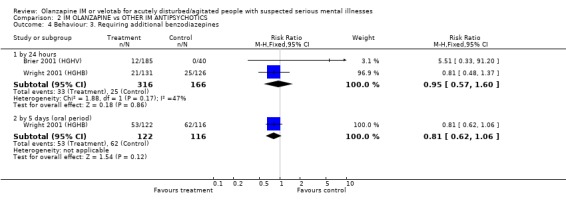

3. COMPARISON 2. IM OLANZAPINE versus OTHER IM ANTIPSYCHOTICS We were able to include data from two trials for this comparison. The trials involved 482 disturbed and agitated people, 166 of whom were allocated to haloperidol.

3.1 Global effect The trialists defined 'no important clinical response' as a less than 40% reduction in symptoms measured by the PANSS‐EC. They found no differences between olanzapine IM and haloperidol by 2 hours (2 RCTs, n= 482, RR 1.00 CI 0.73 to 1.38).

3.2. Behaviour 3.2.1 Leaving the study early Wright 2001 (HGHB) found no difference between those given olanzapine IM and people allocated to haloperidol for the outcome of leaving the study early (n=257, RR 0.87 CI 0.36 to 2.06)

3.2.2 Requiring additional IM injections or benzodiazepines Two trials found no significant between olanzapine IM and haloperidol for needing repeat IM injections (2 RCTs, n=482, RR 0.99 CI 0.71 to 1.38). By 24 hours the same studies also did not find any difference between the two groups for needing additional benzodiazepines (2 RCTs, n=482, RR 0.95 CI 0.57 to 1.60). This null finding held to the five day extension with oral drugs (1 RCT, n=238, RR 0.81 CI 0.62 to 1.06).

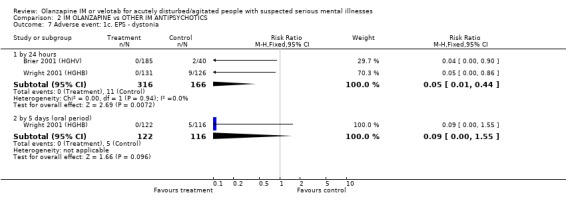

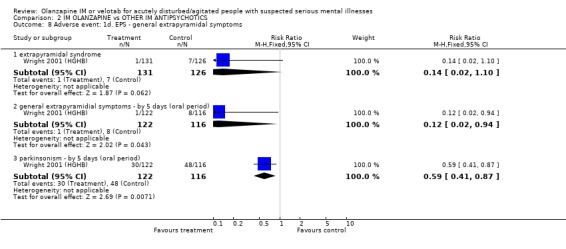

3.3 Adverse events 3.3.1 Extrapyramidal adverse effects More people on haloperidol experienced akathisia over the five day oral period compared with olanzapine IM (1 RCT, n=257, RR 0.51 CI 0.32 to 0.80, NNT 6 CI 5 to 15). Fewer people allocated to olanzapine IM required anticholinergic medication by 24 hours compared with those given haloperidol IM (2 RCTs, n= 432, RR 0.20 CI 0.09 to 0.44, NNT 8 CI 7 to 11). This finding was also true for the five day period (1 RCT, n=238, RR 0.08 CI 0.02 to 0.24, NNT 4 CI 4 to 5). None of the people who had received olanzapine IM reported episodes of dystonia in the first 24 hours, whilst 11 of those given haloperidol IM reported this distressing effect (2 RCTs, n=482, RR 0.05 CI 0.01 to 0.44, NNT 18 CI 17 to 30). During the first 24 hours, more people on haloperidol IM experienced extrapyramidal adverse effects than those who were on olanzapine IM. This difference did not reach the conventional level of statistical significance (1 RCT, n= 257, RR 0.14 CI 0.02 to 1.10). By the fifth day of oral treatment, this finding in favour of olanzapine IM was statistically significant (1 RCT, n=238, RR 0.12 CI 0.02 to 0.94, NNT 18 CI 17 to 278). Finally, less people experienced parkinsonian symptoms when they were taking olanzapine IM compared with those who were on haloperidol IM (1 RCT, n=238, RR 0.59 CI 0.41 to 0.87, NNT 6 CI 5 to 19).

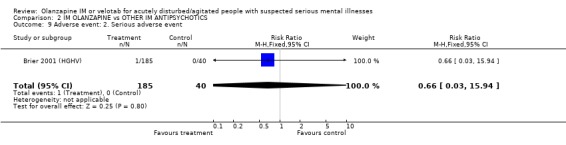

3.3.2 Serious adverse event One study reported one serious adverse event of anaemia and ECG abnormality experienced by a person taking olanzapine IM (n=225, RR 0.66 CI 0.03 to 15.94).

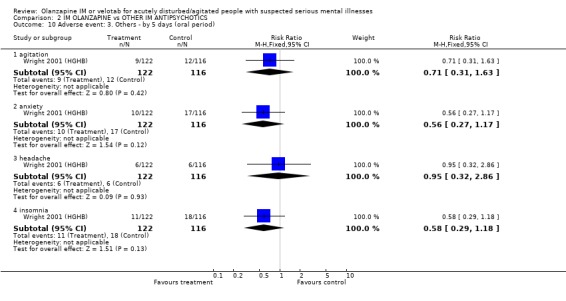

3.3.3 Others During the 5 day oral period there was no significant difference between haloperidol IM and olanzapine IM for the adverse effects of anxiety (1 RCT, n=238, RR 0.56 CI 0.27 to 1.17), agitation (1 RCT, n=238, RR 0.71 CI 0.31 to 1.63), headache (1 RCT, n=238, RR 0.95 CI 0.32 to 2.86) and insomnia (1 RCT, n=238, RR 0.58 CI 0.29 to 1.18).

3.4 Missing outcomes Outcomes such as duration of hospital stay, severity of symptoms when discharged from hospital, changes in hospital status (for example, changes from informal care to formal detention, changes to the level of observation by ward staff and use of secluded nursing environment) and changes in services provided by community teams were not reported in the studies. No studies reported any outcomes related to satisfaction with care and no studies reported suicide, self‐harm or harm to others.

3.5 Measured acceptance of treatment All studies included participants who gave informed consent but none reported the number of patients who refused to consent. For these short studies, the completion rate was above 90%. This does mean, however, that these short studies lost nearly 10% of the included participants within a matter of hours.

4. COMPARISON 3. IM OLANZAPINE versus BENZODIAZEPINES Meehan 2001 and Meehan 2002 compared olanzapine IM with lorazepam (total n=355, 119 of whom were allocated to lorazepam).

4.1 Death There were no reports of death within 24 hours in Meehan 2001.

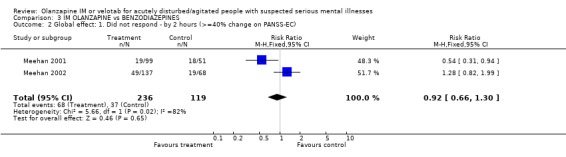

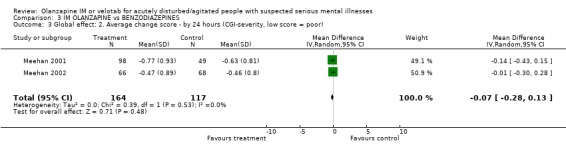

4.2 Global effect Using a >=40% change on PANSS‐EC, trialists found no difference between people given olanzapine IM and those allocated to lorazepam at 2 hours (2 RCTs, n=355, RR 92 CI 0.66 to 1.30). Results are also equivocal between groups for the outcome of change using the CGI‐severity score at 24 hours (2 RCTs, n=281, WMD ‐0.07 CI ‐0.28 to 0.13).

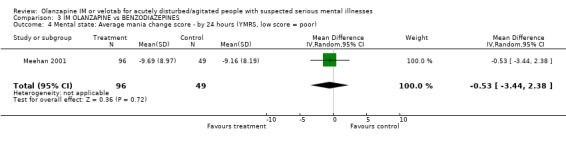

4.3 Mental state At 24 hours Meehan 2001 reports equivocal results for the outcome of mania as recorded on the Young Mania Rating Scale (n=145, WMD ‐0.53 CI ‐3.44 to 2.38).

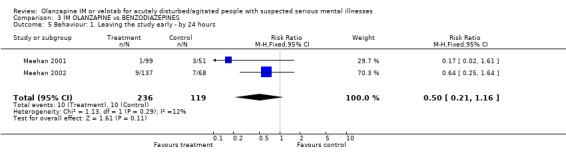

4.4 Behaviour For the outcome of leaving the study early, studies detected no difference between people given olanzapine IM and those allocated to lorazepam, with 4% of those on olanzapine IM and 8% of those on lorazepam IM being unavailable to follow up by 24 hours (2 RCTs, n=355, RR 0.50 CI 0.21 to 1.16).

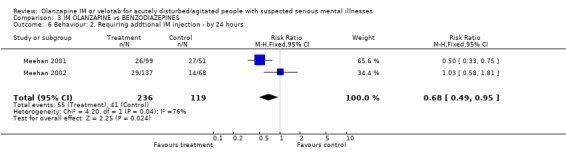

Fewer people allocated to olanzapine IM required additional injections by 24 hours compared with those on lorazepam IM (2 RCTs, n=355, RR 0.68 CI 0.49 to 0.95, NNT 10 CI 6 to 59).

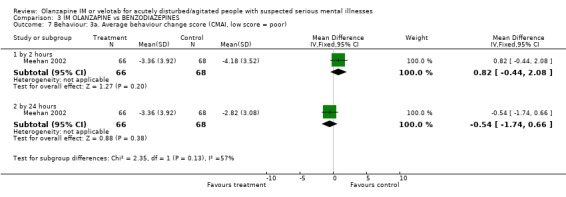

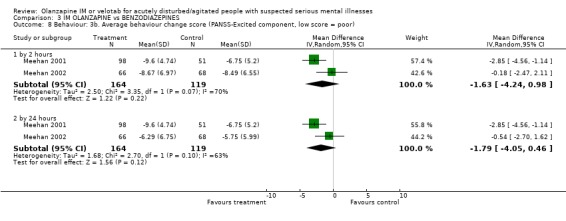

Studies used two different scales to rate change in behaviour. Using the Cohen‐Mansfield Agitation inventory, Meehan 2002 reports no clear difference between groups for outcomes at 2 hours (1 RCT, n=134, MD 0.82 CI ‐0.44 to 2.08) and at 24 hours (1 RCT, n=134, MD ‐0.54 CI ‐1.74 to 0.66). Rating on the PANSS‐Excited component did not show significant differences at 2 hours (2 RCTs, n=283, MD ‐1.63 CI ‐4.24 to 0.98) or by 24 hours (2 RCTs, n=283, MD ‐1.79 CI ‐4.05 to 0.46).

4.5 Adverse events People receiving IM olanzapine were less likely to experience any treatment emergent adverse events than those on lorazepam (1 RCT, n=150, RR at 24 hours 0.62 CI 0.43 to 0.89, NNT 5 CI 4 to 17). Over the same time period there were no clear differences in the use of anticholinergic medication between groups (1 RCT, n=150, RR 1.16 CI 0.38 to 3.58). Meehan 2001 and Meehan 2002 report a series of adverse effects including accidental injury in elderly participants, dizziness, ECG abnormality, headache, somnolence and vasodilation. For all these there was no clear advantage to using either drug. However, people given olanzapine IM experienced nausea less often (1 RCT, n=150, RR 0.15 CI 0.03 to 0.68, NNT 10 CI 8 to 25) and less vomiting (1 RCT, n=150, RR 0.09 CI 0.01 to 0.69, NNT 10 CI 10 to 30).

4.6 Missing outcomes Outcomes such as duration of hospital stay, severity of symptoms when discharged from hospital, changes in hospital status (for example, changes from informal care to formal detention, changes to the level of observation by ward staff and use of secluded nursing environment) and changes in services provided by community teams were not reported in the studies. No studies reported suicide, self‐harm or harm to others and no studies reported any outcomes related to satisfaction with care.

4.7 Measured acceptance of treatment All studies included participants who gave informed consent but did not report the number of patient who refused to consent or did not agree to participate. For those who participated, the completion rate was above 90%.

Discussion

1. Limited data 1.1 No data Velotab, as far as we can find, has never been evaluated in a randomised trial. It is not enough to assume that the difficulty in spitting out results in enhanced effects and justifies the increased cost. We attest that this preparation could be doing far more good than we can realise outside of an objective study. Conversely, velotab could be no more effective or even harmful than other treatments and this has not been investigated within randomised studies.

Even within the studies that do exist, there are no data on outcomes such as discharged or time in restraints, or needing a visit of the attending doctor. It could be expected that aggressive incidents did occur but no reports of self‐harm or harm to others are recorded. There are no economic data at all. It has to be assumed that some of these may not be favourable to the new compound.

1.2 Quality of existing data Selection bias can be minimised through good quality blinding at allocation. Improper allocation concealment can affect estimation of treatment effects (Chalmers 1983). All studies stated that random allocation was used but only Wright 2001 (HGHB) reported adequate methods of random sequence generation. Allocation concealment was not mentioned in any study. This has to suggest that there is an over estimate of effect of the experimental treatment in these studies. Rigorous blinding procedures are important to minimise performance and attrition bias in controlled trials (Jadad 1996) and in the included studies blinding is emphasised. Wright 2001 (HGHB) described an adequate blinding mechanism (identical, colour blinded, translucent standard syringe and rater and study personnel were blind to treatment assignment) but Meehan 2001, Meehan 2002 and Brier 2001 (HGHV) did not include this type of description. Moreover, no trial tested the blindness (by asking participants and research personnel which drug they thought was being administered). This can affect estimated efficacy of the tested drugs and is likely to favour the olanzapine IM in these company sponsored trials.

Attrition rates seem low in all included studies when compared with the standard losses of 30‐50% in trials of antipsychotics lasting into weeks (Thornley 1998). However, compared with recent studies of similar populations (TREC 2003, Alexander 2004) 8‐10% attrition for only a few hours is very large indeed and more than would be expected in routine care.

1.3 Applicability of existing data Three trials were set in hospital, whilst Meehan 2002 recruited participants from hospitals as well as nursing homes. People suffering from severe mental illness or suspected serious mental illness when presenting with agitation or aggression often need hospital admission, so results could be relevant to everyday practice. However, most participants were able to give informed consent to participate in these trials, which leaves a very considerable question regarding the levels of disturbance and whether these people are really like those who present as aggressive in routine clinical practice. This seems unlikely.

Groups of participants differed among the various included trials. Wright 2001 (HGHB) and Brier 2001 (HGHV) included people with schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder and schizoaffective disorder. Meehan 2001 included participants suffering from bipolar disorder, mania or a mixture of the two. Meehan 2002 included participants suffering from Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia or a combination of both dementias. This mixed set of diagnoses would be the one for which clinicians would be expected to use olanzapine IM. We trust that the PANNS‐EC score used to decide acute agitation (>14 on 4 items) in all studies is relevant to everyday care, but have to take it on trust as we are unsure if this scale is ever used in routine care.

We have some difficulty with the use of placebo in this group of people. Data from four trials involving 769 disturbed and agitated people, 217 of whom were allocated to placebo are used in this review. We are unsure if these are studies can be considered to be ethical in many situations where good effective treatments are available. Employing haloperidol and lorazepam as comparisons is understandable, however, when it is hoped to introduce olanzapine IM to countries already using these interventions (Allen 2001, NICE 2004).

2 COMPARISON 1. IM OLANZAPINE versus PLACEBO 2.1 Death In these relatively small trials, there were no reports of death (Meehan 2001) but we note how, because of deaths attributed to the use of olanzapine IM in the UK, clinicians have advised on not using olanzapine IM with patients who have cardiovascular problems or in the elderly.

2.2 Global effect It is clear that olanzapine is better at reducing PANSS‐EC scores by =/> 40% at two hours, but the clinical utility of a 0.42 to 0.59 reduction in these scores is not clear, especially in a 2 or 24 hour period. The number of people who need to be treated with olanzapine in order for one person to achieve this outcome is four (CI 3 to 5) and it may be that those using a treatment in such an emergency situation would want a NNT even smaller than this. We regret being unable to use the pragmatic Agitation Calmness Evaluation Scale (ACES) developed by Eli Lilly, but we have no information on whether this scale has been fully published and, as shown by Marshall 2000, the potential for biased results from unpublished rating scales is high.

2.3 Mental state In keeping with the global measure, the scores on the CGI‐S, which provide the only mental state rating (mania score), were equivocal. Perhaps this is to be expected over such a short period (2 and 24 hours).

2.4 Behaviour Three percent of people taking olanzapine and 10% of those on placebo left the study early or were unavailable for follow up at 24 hours. This seems low, certainly compared with longer studies from similar stables (Thornley 1998). However, other recent rapid tranquillisation studies managed 99% follow up, although these were comparisons of two active comparators, rather than with an inert placebo (Huf 2000, TREC 2003, Alexander 2004). Whilst the authors understand the need for regulatory approval, they still wonder about the ethics of inert, placebo controlled trials in such circumstances.

The number of additional injections required is a useful pragmatic outcome as a proxy measure of improvement in behaviour and global state. It is clear that giving olanzapine IM is more effective than giving an inert placebo in circumstances where rapid traquillisation/sedation is required, with between 4 and 5 people being treated with olanzapine to prevent the need for further injections. This figure is quite high as this treatment may involve repeated assaults on the patient. In keeping with this finding, more people on placebo required additional injections of benzodiazepines compared with those on olanzapine, with between 8 to 12 people being treated with olanzapine to prevent the need for additional injections of benzodiazepines again, quite a high number needed to treat.

Olanzapine IM is also effective at reducing those behaviours that are measured using the ABS. However, the behaviours measured by the CMAI do not seem as changeable at either 2 or 24 hours. Those behaviours measured by the PANSS‐EC are significantly improved at 2 hours, but this is not maintained to 24 hours, with each group being equally calmed. This might suggest that agitation and aggression are events that will reduce equally over a 24 hour period, but we find it difficult to make clinical sense of these data.

2.5 Adverse effects In the short term of 2 to 24 hours, olanzapine IM seems no worse or better at either inducing or avoiding any adverse events compared with placebo. Also, in the very short term, there is no greater need for people given olanzapine IM to require additional anticholinergic medication compared with people allocated placebo. This could be a function of the very short follow up of the studies or the combination of this and the fact that extrapyramidial adverse effects are not a major feature of taking olanzapine. One person in the olanzapine group experienced an ECG abnormality and anaemia.

3. COMPARISON 2. IM OLANZAPINE versus OTHER IM ANTIPSYCHOTICS 3.1 Global effect There was no benefit in giving or taking olanzapine IM over haloperidol IM at 2 hours to reduce the PANSS‐EC score by =/>40%. Both are effective for this outcome.

3.2 Behaviour Seven percent of people given olanzapine IM and 8% allocated to haloperidol left the study at 24 hours. These do seem to be high figures and routine clinical practice would not expect to lose as many people as this within that short period. It may be expected that within the tight constraints of a trial, that attrition would be even less. However, neither intervention is worse than the other, each being as likely to lose participants.

As a proxy measure of effectiveness, the outcome of requiring additional IM injections does not find any difference between the two comparators, with about 28% of each group requiring additional injections within 24 hours. Ten to 15% required benzodiazepines in this same time period with no difference between groups, and at five days 43‐53% required benzodiazepines. At no time was this statistically significant.

3.3 Adverse events Olanzapine IM only has clear advantages over haloperidol IM for the adverse effects of movement disorders. In the first 24 hours, fewer people receiving olanzapine IM will require anticholinergic medication than those on haloperidol. This significance was not sustained at 5 days follow‐up with 43% on olanzapine and 53% of those on haloperidol requiring anticholinergic medication. People taking olanzapine will experience less adverse events that require medication and less akathisia than those on haloperidol at five days, with between 5 to 15 people taking olanzapine to avoid one person having akathisia. Dystonia will also be more prevalent amongst those taking haloperidol at 24 hours. Oddly, for the outcome of any extrapyramidial symptoms, little can be said between the 2 groups at 24 hours. However, at 5 days, olanzapine causes less extrapyramidal symptoms then haloperidol, with between 17 to 278 people needing to take olanzapine to prevent one additional episode of these problematic symptoms. In keeping with these findings, fewer people taking olanzapine experienced parkinsonian symptoms at five days (NNT 6 CI 5 to 19).

4. COMPARISON 3. IM OLANZAPINE versus BENZODIAZEPINES 4.1 Death No reports of death were made in Meehan 2001.

4.2 Global effect There are no benefits to giving olanzapine over lorazepam in reducing PANSS‐EC score by >/=40% at 2 hours. This is also true of achieving a statistically significant change on the CGI‐severity scale at 24 hours.

4.3 Mental state It would have been a surprise to see major changes in rating of mania at 24 hours and, indeed, there were no significant advantages of one drug versus another.

4.4 Behaviour There does not seem to be an advantage to giving olanzapine IM over lorazepam IM in terms of keeping people in the study. We are not sure if this translates into losing contact with people in clinical life but this could be one interpretation. Fewer people on olanzapine required additional IM injections by 24 hours than those on lorazepam with between 6 to 59 people needing to be given olanzapine IM to prevent one additional intramuscular injection.

4.5 Adverse events People allocated to olanzapine IM were less likely to experience any treatment emergent adverse events than those on lorazepam, with 4 to 17 needing to receive olanzapine IM to prevent another treatment emergent event. People on olanzapine were as likely to receive anticholinergic medication as those on lorazepam at 24 hours. However, people on olanzapine experienced less nausea (NNT 10 CI 8 to 25) or vomiting (NNT 10 CI 10 to 30) than those on lorazepam.

5. Missing outcomes All key service outcomes that are not difficult to record, even in the short period of these studies, are missing. There are no data on hospital discharge, transfer, use of restraints or seclusion or compulsory detention. There are no economic data at all. These omissions in these relatively recent studies are difficult to justify and to understand outside of a context where the sponsor of the study failed to design in outcomes that could have jeopardised a desired result.

6. Missing comparisons The velotab preparation of olanzapine almost instantly dissolves in the mouth to make spitting out very difficult. This is an attractive option in the urgent situation. The velotab is even more expensive than standard oral olanzapine. We have no data from trials to suggest that this option is effective as well as attractive. We cannot be sure that the additional expense is justified and it is possible that it is harmful to a greater extent than the more slowly acquired oral treatment.

Authors' conclusions

1. For people with agitation in acute psychotic illness Data relevant to the effects of olanzapine IM are taken from some studies that may not be considered ethical in many places. All are funded by a company with a pecuniary interest in the result, and the outcomes of the studies are often both poorly reported and difficult to interpret for routine care. Other important outcomes are not recorded at all. Nevertheless, olanzapine IM probably has some value in helping manage acute aggression or agitation, especially where it is necessary to avoid some of the older better known treatments. Olanzapine causes fewer movement disorders than haloperidol and more than lorazepam. The value of the velotab preparation is untested in trials.

2. For clinicians The company marketing olanzapine IM (Eli Lilly) and Department of Health, UK recommends that IM olanzapine should not be used in the elderly where there is a history of cardiovascular events. In this group the use of olanzapine IM has been linked with deaths.

There are real difficulties generalising the findings of the included studies to everyday care. The people in these studies gave informed consent before being included. In addition, recommendations on the use of IM olanzapine for agitated or aggressive people in severely mentally ill patients rather than other 'standard' or 'non‐standard' treatments is to be viewed on the basis of adverse effects rather than positive effects. With those provisos, olanzapine IM seems superior to placebo and equivalent to the use of lorazepam or haloperidol in terms of levels of sedation or requiring additional sedative medication. Olanzapine results in less need for anticholinergic medication for extrapyramidal side effects than haloperidol. However, not one trial addressed the major clinical issue of 'rapid tranquillisation'. Studies are hypothesis‐generating rather than hypothesis‐testing, and guidance overstating the value of these preparations on the basis of the evidence included in this review should be viewed with caution.

3. For managers/policy makers Including olanzapine IM or velotabs in protocols for the management of acute agitation or aggression as a first line choice is not supported by this evidence. Including these preparations as second line is also problematic as there are other better evaluated, safe, treatments (Huf 2004). Including these preparations in protocols for the management of acute agitation or aggression as third line may be justified as there has, at least, been some effort to evaluate IM olanzapine.

4. For funders Olanzapine IM and velotabs are expensive when compared with other preparations used for helping manage people who are aggressive. For those making cost‐effectiveness and cost‐utility decisions, there is currently no useful trial‐derived data to help decision making.

1. General These recent studies did not comply with CONSORT guidelines for reporting of trials (Moher 2001). This reflects poorly on authors, the drug company and the editors of the journals in which these papers were published.

2. Specific There is a need for well designed, conducted and reported randomised studies in this area. Such studies are possible (TREC 2003, Alexander 2004) and should be designed with patient groups and clinicians in mind. They should report outcomes of clear value to the management of people at this difficult point in their illness. As there are currently no well designed randomised studies of the orodispersable (velotab) formulation of olanzapine, this should be seen as a priority.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement for the help and assistance from Clive Adams and Judy Wright, Gillian Rizzello and Tessa Grant of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group. With thanks to Eli Lilly Pharma, Berne, Switzerland, who readily provided information for this review.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

IM OLANZAPINE vs IM PLACEBO

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death ‐ by 24 hours | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Global effect: 1. Did not respond ‐ by 2 hours | 4 | 769 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.42, 0.59] |

| 3 Global effect: 2. Average change score ‐ by 24 hours (CGI‐S, low score=poor)* | 2 | 281 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.05 [‐0.19, 0.29] |

| 4 Mental state: Average mania change score ‐ by 24 hours (YMRS, low score = poor) | 1 | 122 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.54 [‐5.39, 2.31] |

| 5 Behaviour: 1. Leaving the study early ‐ by 24 hours | 2 | 354 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.06, 1.55] |

| 6 Behaviour: 2. Requiring further IM injection ‐ by 24 hours | 4 | 774 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.40, 0.58] |

| 7 Behaviour: 3. Requiring additional benzodiazepines ‐ within 24 hours | 2 | 420 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.21, 0.47] |

| 8 Behaviour: 4a. Average behaviour change score (ABS, low score = poor) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 by 2 hours | 1 | 149 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.91 [‐5.02, ‐0.80] |

| 8.2 by 24 hours | 1 | 148 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.16 [‐5.03, ‐1.29] |

| 9 Behaviour: 4b. Average behaviour change score (CMAI, low score = poor) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 by 2 hours | 1 | 133 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.19 [‐2.43, 0.05] |

| 9.2 by 24 hours | 1 | 133 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.15 [‐2.42, 0.12] |

| 10 Behaviour: 4c. Average behaviour change score (PANSS‐Excited component, low score = poor) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10.1 by 2 hours | 2 | 281 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.33 [‐5.65, ‐3.01] |

| 10.2 by 24 hours | 2 | 283 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.79 [‐4.05, 0.46] |

| 11 Adverse event: 1. Any adverse event ‐ in 24 hours | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.78, 2.32] |

| 12 Adverse event: 2. Anxiety ‐ by 24 hours | 1 | 235 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.04 [0.00, 0.75] |

| 13 Adverse event: 3. EPS ‐ requiring anticholinergic medication ‐ by 24 hours | 3 | 570 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.49, 3.26] |

| 14 Adverse event: 4. Serious adverse event ‐ by 24 hours | 1 | 230 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.03, 17.92] |

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 IM OLANZAPINE vs IM PLACEBO, Outcome 1 Death ‐ by 24 hours.

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 IM OLANZAPINE vs IM PLACEBO, Outcome 2 Global effect: 1. Did not respond ‐ by 2 hours.

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 IM OLANZAPINE vs IM PLACEBO, Outcome 3 Global effect: 2. Average change score ‐ by 24 hours (CGI‐S, low score=poor)*.

Analysis 1.4.

Comparison 1 IM OLANZAPINE vs IM PLACEBO, Outcome 4 Mental state: Average mania change score ‐ by 24 hours (YMRS, low score = poor).

Analysis 1.5.

Comparison 1 IM OLANZAPINE vs IM PLACEBO, Outcome 5 Behaviour: 1. Leaving the study early ‐ by 24 hours.

Analysis 1.6.

Comparison 1 IM OLANZAPINE vs IM PLACEBO, Outcome 6 Behaviour: 2. Requiring further IM injection ‐ by 24 hours.

Analysis 1.7.

Comparison 1 IM OLANZAPINE vs IM PLACEBO, Outcome 7 Behaviour: 3. Requiring additional benzodiazepines ‐ within 24 hours.

Analysis 1.8.

Comparison 1 IM OLANZAPINE vs IM PLACEBO, Outcome 8 Behaviour: 4a. Average behaviour change score (ABS, low score = poor).

Analysis 1.9.

Comparison 1 IM OLANZAPINE vs IM PLACEBO, Outcome 9 Behaviour: 4b. Average behaviour change score (CMAI, low score = poor).

Analysis 1.10.

Comparison 1 IM OLANZAPINE vs IM PLACEBO, Outcome 10 Behaviour: 4c. Average behaviour change score (PANSS‐Excited component, low score = poor).

Analysis 1.11.

Comparison 1 IM OLANZAPINE vs IM PLACEBO, Outcome 11 Adverse event: 1. Any adverse event ‐ in 24 hours.

Analysis 1.12.

Comparison 1 IM OLANZAPINE vs IM PLACEBO, Outcome 12 Adverse event: 2. Anxiety ‐ by 24 hours.

Analysis 1.13.

Comparison 1 IM OLANZAPINE vs IM PLACEBO, Outcome 13 Adverse event: 3. EPS ‐ requiring anticholinergic medication ‐ by 24 hours.

Analysis 1.14.

Comparison 1 IM OLANZAPINE vs IM PLACEBO, Outcome 14 Adverse event: 4. Serious adverse event ‐ by 24 hours.

Comparison 2.

IM OLANZAPINE vs OTHER IM ANTIPSYCHOTICS

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Global effect: Did not respond ‐ by 2 hours (>=40% change on PANSS‐EC) | 2 | 482 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.73, 1.38] |

| 2 Behaviour: 1. Leaving the study ‐ by 24 hours | 1 | 257 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.36, 2.06] |

| 3 Behaviour: 2. Requiring addtional IM injection ‐ by 24 hours | 2 | 482 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.71, 1.38] |

| 4 Behaviour: 3. Requiring additional benzodiazepines | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 by 24 hours | 2 | 482 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.57, 1.60] |

| 4.2 by 5 days (oral period) | 1 | 238 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.62, 1.06] |

| 5 Adverse event: 1a. EPS ‐ akathisia ‐ by 5 days (oral period) | 1 | 238 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.32, 0.80] |

| 6 Adverse event: 1b. EPS ‐ requiring anticholinergic medication | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 by 24 hours | 2 | 482 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.20 [0.09, 0.44] |

| 6.2 by 5 days (oral period) | 1 | 238 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.08 [0.02, 0.24] |

| 7 Adverse event: 1c. EPS ‐ dystonia | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 by 24 hours | 2 | 482 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.05 [0.01, 0.44] |

| 7.2 by 5 days (oral period) | 1 | 238 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.09 [0.00, 1.55] |

| 8 Adverse event: 1d. EPS ‐ general extrapyramidal symptoms | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 extrapyramidal syndrome | 1 | 257 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.14 [0.02, 1.10] |

| 8.2 general extrapyramidial symptoms ‐ by 5 days (oral period) | 1 | 238 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.12 [0.02, 0.94] |

| 8.3 parkinsonism ‐ by 5 days (oral period) | 1 | 238 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.41, 0.87] |

| 9 Adverse event: 2. Serious adverse event | 1 | 225 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.03, 15.94] |

| 10 Adverse event: 3. Others ‐ by 5 days (oral period) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10.1 agitation | 1 | 238 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.31, 1.63] |

| 10.2 anxiety | 1 | 238 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.27, 1.17] |

| 10.3 headache | 1 | 238 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.32, 2.86] |

| 10.4 insomnia | 1 | 238 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.29, 1.18] |

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 IM OLANZAPINE vs OTHER IM ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 1 Global effect: Did not respond ‐ by 2 hours (>=40% change on PANSS‐EC).

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 IM OLANZAPINE vs OTHER IM ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 2 Behaviour: 1. Leaving the study ‐ by 24 hours.

Analysis 2.3.

Comparison 2 IM OLANZAPINE vs OTHER IM ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 3 Behaviour: 2. Requiring addtional IM injection ‐ by 24 hours.

Analysis 2.4.

Comparison 2 IM OLANZAPINE vs OTHER IM ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 4 Behaviour: 3. Requiring additional benzodiazepines.

Analysis 2.5.

Comparison 2 IM OLANZAPINE vs OTHER IM ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 5 Adverse event: 1a. EPS ‐ akathisia ‐ by 5 days (oral period).

Analysis 2.6.

Comparison 2 IM OLANZAPINE vs OTHER IM ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 6 Adverse event: 1b. EPS ‐ requiring anticholinergic medication.

Analysis 2.7.

Comparison 2 IM OLANZAPINE vs OTHER IM ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 7 Adverse event: 1c. EPS ‐ dystonia.

Analysis 2.8.

Comparison 2 IM OLANZAPINE vs OTHER IM ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 8 Adverse event: 1d. EPS ‐ general extrapyramidal symptoms.

Analysis 2.9.

Comparison 2 IM OLANZAPINE vs OTHER IM ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 9 Adverse event: 2. Serious adverse event.

Analysis 2.10.

Comparison 2 IM OLANZAPINE vs OTHER IM ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 10 Adverse event: 3. Others ‐ by 5 days (oral period).

Comparison 3.

IM OLANZAPINE vs BENZODIAZEPINES

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Global effect: 1. Did not respond ‐ by 2 hours (>=40% change on PANSS‐EC) | 2 | 355 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.66, 1.30] |

| 3 Global effect: 2. Average change score ‐ by 24 hours (CGI‐severity, low score = poor) | 2 | 281 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.07 [‐0.28, 0.13] |

| 4 Mental state: Average mania change score ‐ by 24 hours (YMRS, low score = poor) | 1 | 145 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.53 [‐3.44, 2.38] |

| 5 Behaviour: 1. Leaving the study early ‐ by 24 hours | 2 | 355 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.21, 1.16] |

| 6 Behaviour: 2. Requiring addtional IM injection ‐ by 24 hours | 2 | 355 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.49, 0.95] |

| 7 Behaviour: 3a. Average behaviour change score (CMAI, low score = poor) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 by 2 hours | 1 | 134 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [‐0.44, 2.08] |

| 7.2 by 24 hours | 1 | 134 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.54 [‐1.74, 0.66] |

| 8 Behaviour: 3b. Average behaviour change score (PANSS‐Excited component, low score = poor) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 by 2 hours | 2 | 283 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.63 [‐4.24, 0.98] |

| 8.2 by 24 hours | 2 | 283 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.79 [‐4.05, 0.46] |

| 9 Adverse event: 1. Any treatment emergent adverse event ‐ by 24 hours | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.43, 0.89] |

| 10 Adverse event: 2. EPS ‐ requiring anticholinergic medication | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.38, 3.58] |

| 11 Adverse event: 3. Other ‐ by 24 hours | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 11.1 accidental injury | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.27, 1.31] |

| 11.2 dizzyness | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.44, 2.39] |

| 11.3 ECG abnormality | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.35, 2.06] |

| 11.4 headache | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.35, 1.85] |

| 11.5 hypertension | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.26, 1.39] |

| 11.6 nausea | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.15 [0.03, 0.68] |

| 11.7 somnolence | 2 | 355 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.36, 1.15] |

| 11.8 vasodilation | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.32, 1.92] |

| 11.9 vomiting | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.09 [0.01, 0.69] |

Analysis 3.1.

Comparison 3 IM OLANZAPINE vs BENZODIAZEPINES, Outcome 1 Death.

Analysis 3.2.

Comparison 3 IM OLANZAPINE vs BENZODIAZEPINES, Outcome 2 Global effect: 1. Did not respond ‐ by 2 hours (>=40% change on PANSS‐EC).

Analysis 3.3.

Comparison 3 IM OLANZAPINE vs BENZODIAZEPINES, Outcome 3 Global effect: 2. Average change score ‐ by 24 hours (CGI‐severity, low score = poor).

Analysis 3.4.

Comparison 3 IM OLANZAPINE vs BENZODIAZEPINES, Outcome 4 Mental state: Average mania change score ‐ by 24 hours (YMRS, low score = poor).

Analysis 3.5.

Comparison 3 IM OLANZAPINE vs BENZODIAZEPINES, Outcome 5 Behaviour: 1. Leaving the study early ‐ by 24 hours.

Analysis 3.6.

Comparison 3 IM OLANZAPINE vs BENZODIAZEPINES, Outcome 6 Behaviour: 2. Requiring addtional IM injection ‐ by 24 hours.

Analysis 3.7.

Comparison 3 IM OLANZAPINE vs BENZODIAZEPINES, Outcome 7 Behaviour: 3a. Average behaviour change score (CMAI, low score = poor).

Analysis 3.8.

Comparison 3 IM OLANZAPINE vs BENZODIAZEPINES, Outcome 8 Behaviour: 3b. Average behaviour change score (PANSS‐Excited component, low score = poor).

Analysis 3.9.

Comparison 3 IM OLANZAPINE vs BENZODIAZEPINES, Outcome 9 Adverse event: 1. Any treatment emergent adverse event ‐ by 24 hours.

Analysis 3.10.

Comparison 3 IM OLANZAPINE vs BENZODIAZEPINES, Outcome 10 Adverse event: 2. EPS ‐ requiring anticholinergic medication.

Analysis 3.11.

Comparison 3 IM OLANZAPINE vs BENZODIAZEPINES, Outcome 11 Adverse event: 3. Other ‐ by 24 hours.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 August 2009 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2002 Review first published: Issue 2, 2005

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 31 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, placebo controlled. Blinding: double. Duration: 24 hours. Setting: multicentre, inpatients. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia, schizophreniform or schizoaffective disorder. N=270. Age: 18‐73 years, mean ˜ 36 years. Sex: 57.4% male. State: inpatient, current acute agitation. Exclusions: agitation due substance abuse, use of benzodiazepine within 4 hours/ use of depot antipsychotics or use of antipsychotics within 2 hours of study drug administration. | |

| Interventions | 1. Olanzapine IM: dose 2.5mg. N=48. 2. Olanzapine IM: dose 5mg. N=45. 3. Olanzapine IM: dose 7.5 mg. N=46. 4. Olanzapine IM: dose 10 mg. N=46. 5. Haloperidol IM: dose 7.5 mg. N=40. 6. Placebo IM. N=50. Participants allowed to receive 1 to 3 injections in 24 hours. Use of antiparkinsonian drugs and benzodiazepines permitted. |

|

| Outcomes | Response: 40% reduction in PANSS‐EC score at 2 hours. Behaviour: number of doses, additional benzodiazepines. Adverse events: use of anticholinergics, treatment emergent events >/+5% incidence, serious adverse events. Unable to use ‐ Adverse events: SAS, Barnes, QTc intervals at 2 hours (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | Trial sponsored by manufactures of olanzapine IM. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, placebo controlled. Blindness: double. Duration: 24 hours. Setting: inpatient, multicentre 26 investigators USA, 3 Romania. Screening period. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: DSM‐IV diagnosis of bipolar disorder, manic or mixed. N=201. Age: mean 40 (SD 11.3). Sex: 53.3% male. State: deemed to have agitation severe enough to be appropriate candidates for receiving injections, have a minimum total score of 14 on 5 items comprising the PANSS ‐ excited component, and 1 individual item score of at least 4. Exclusions: none reported. | |

| Interventions | 1. Olanzapine IM: 3 injections, dose 10mg, 10mg, 5mg. N=99. 2. Lorazepam IM: 3 injections, dose 2mg, 2mg, 1mg. N=51. 3. Placebo IM: 2 injections and if necessary, 3rd injection IM olanzapine.* N=51. * those requiring 3rd injection were excluded from analysis. Allowed concomitant lithium or velotab. Benztropine, biperiden or procyclidine allowed for the control of EPS. |

|

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early. Response: >/= 40%improvement on PANSS‐EC score by 2 hours. Behaviour: requiring additional dose of antipsychotic medication. Adverse events: treatment emergent, requiring anticholinergic medication. Unable to use ‐ Behaviour: Agitation‐Calmness evaluation scale (not published 2 years prior to use, created by company). Mental state: MMSE, BPRS (derived from PANSS). Adverse events: SAS (no usable data), QTc intervals (no usable data), lab tests and physical changes (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | Trial sponsored by manufactures of olanzapine IM. | |

| Risk of bias | ||