Abstract

Background

The 'off‐label' effect of alprazolam on depression has not been systematically evaluated.

Objectives

To determine the antidepressant effect, including tolerability and acceptability, of alprazolam as monotherapy for major depression, when compared to placebo and conventional antidepressants in outpatients and patients in primary care.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and the Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group Register, which includes relevant randomised controlled trials from the following bibliographic databases: The Cochrane Library (all years to February 2012); EMBASE (1970 to February 2012); MEDLINE (1950 to February 2012) and PsycINFO (1960 to February 2012). Two review authors identified relevant trials by assessing the abstracts of all possible studies. We applied no language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We selected randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of alprazolam versus placebo or conventional antidepressants for depression in adults, excluding studies with inpatients only.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors performed the data extraction and 'Risk of bias' assessment independently with disagreements resolved through discussion with a third review author. Primary outcomes included the mean difference (MD) in reduction of depression on a continuous measure of depression symptoms, and the risk ratio (RR) of the clinical response based on a dichotomous measure, with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

We identified 21 alprazolam studies (22 reports) with a total of 2693 participants. Seven studies used a placebo (n = 771) and 20 used cyclic antidepressants (n = 1765). The typical duration of the studies was four to six weeks. We considered six studies to have a high risk of bias.

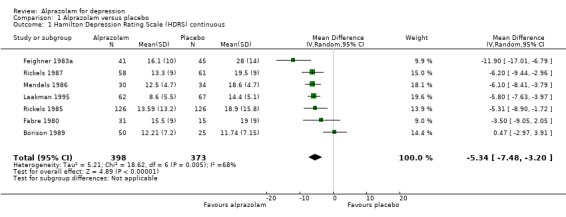

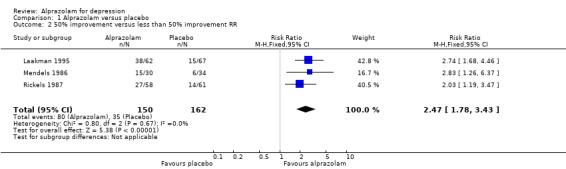

When alprazolam was compared with placebo for reduction in symptoms all estimates indicated a positive effect for alprazolam. Pooled estimates of efficacy data showed a moderately large continuous mean difference (MD) at the end of trial (‐5.34, 95% CI ‐7.48 to ‐3.20; I2 = 68%). The risk difference (RD) for the dichotomous measure of clinical response (50% improvement) was 0.32 in favour of alprazolam (95% CI 0.22 to 0.42; I2 = 0%), with a number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) of 3 (95% CI 2 to 5). The RD of all‐cause withdrawals did not differ between alprazolam and placebo.

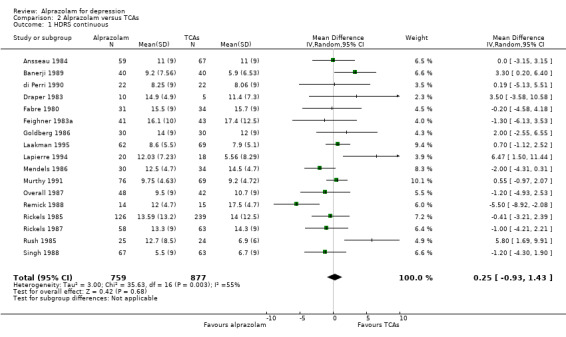

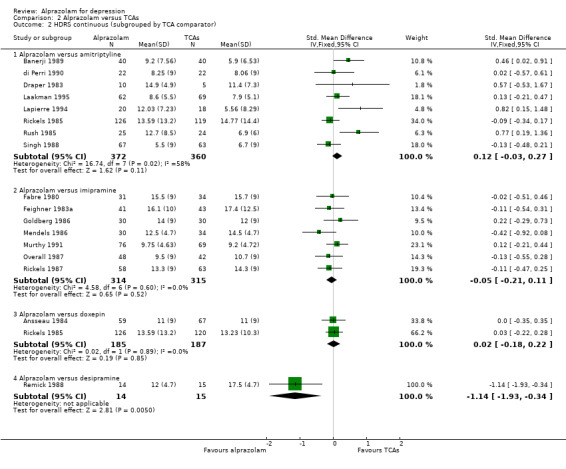

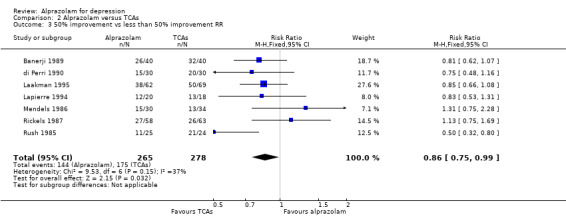

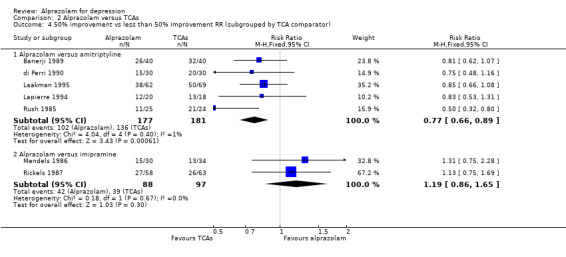

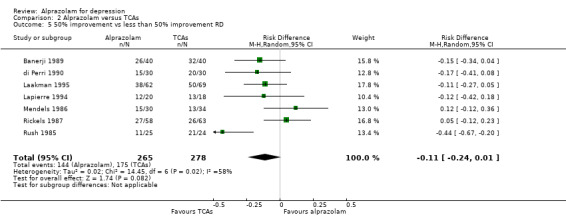

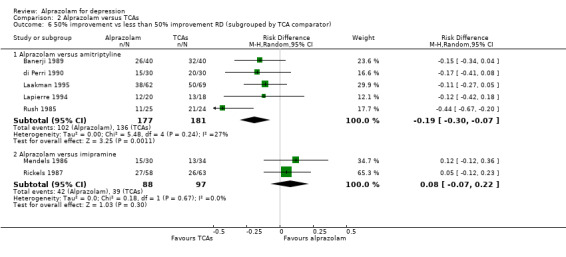

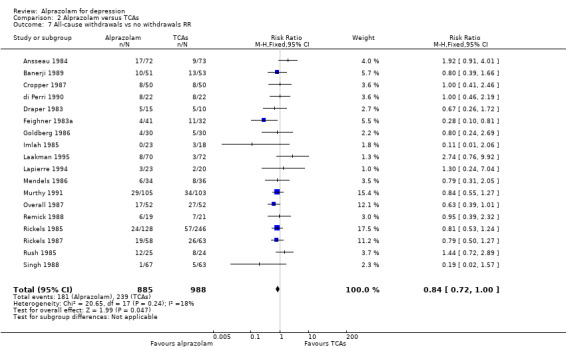

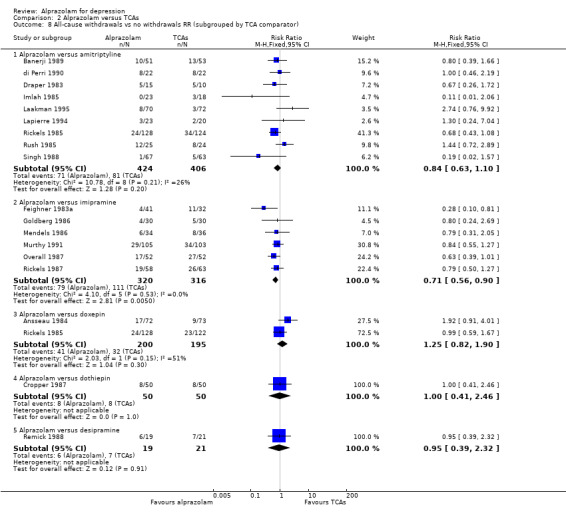

When depression severity was measured as a continuum the effect of alprazolam did not differ statistically or clinically from the effects of any of the conventional antidepressants combined (MD 0.25, 95% CI ‐0.93 to 1.43; I2 = 55%). However, for dichotomised depression severity, alprazolam had less effect than antidepressants (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.99; I2 = 37%; RD ‐0.11, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.01; I2 = 58%; NNTB 9, 95% CI 4 to 100). The RD of all‐cause withdrawals was ‐0.04 (95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.00; I2 = 35%), in favour of alprazolam.

Authors' conclusions

Alprazolam appears to reduce depressive symptoms more effectively than placebo and as effectively as tricyclic antidepressants. However, the studies included in the review were heterogeneous, of poor quality and only addressed short‐term effects, thus limiting our confidence in the findings. Whilst the rate of all‐cause withdrawals did not appear to differ between alprazolam and placebo, and withdrawals were less frequent in the alprazolam group than in any of the conventional antidepressants combined group, these findings should be interpreted with caution, given the dependency properties of benzodiazepines.

Keywords: Adult, Aged, Humans, Middle Aged, Alprazolam, Alprazolam/therapeutic use, Antidepressive Agents, Antidepressive Agents/therapeutic use, Depression, Depression/drug therapy, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Alprazolam for depression

Additional options to help those with depression control their mood, besides psychotherapy and antidepressants, can be important, especially when there is also anxiety involved. One of the drug options is alprazolam, a benzodiazepine. We evaluated the effect of alprazolam for depression. The best evidence currently available suggests that alprazolam may be moderately more effective than a placebo, and as effective as conventional antidepressants, in the treatment of major depression. We cannot conclude whether this is due to its specific antidepressant effect or to a non‐specific effect on sleep and anxiety. There were relatively few short‐term side effects. However, the multiple shortcomings of the currently available evidence, including probable sponsorship bias, publication bias, the age of the studies and the heterogeneity of the results, limit confidence in these findings.

Background

Description of the condition

Depression is a broad and heterogeneous diagnostic grouping, central to which is depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure in most activities. Depressive symptoms are frequently accompanied by symptoms of anxiety, but may also occur on their own. Sleeping problems, lack of energy, eating problems, abnormal feelings of guilt, concentration problems, psychomotor agitation or retardation, and suicidal ideation are other depressive symptoms. Symptoms should be present for at least two weeks or more and every symptom should be present for most of every day (APA 2000). It is doubtful whether the severity of the depressive illness can realistically be captured in a single symptom count. Clinicians will consider family and previous history, as well as the degree of associated disability, in making this assessment.

Description of the intervention

In most countries, the vast majority of patients with major depression are treated in primary care or as outpatients. Specific antidepressant drugs, such as the tricyclics (TCAs) and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), are generally recommended as the primary classes of drugs for these patients, if and when drug treatment is indicated. However, treatment with antidepressants may be difficult in primary care for several reasons: a) antidepressants have a low acceptance and compliance rate and more than 50% of patients who start antidepressant treatment may cease taking their medication (Hansen 2004; Lawrenson 2000); b) depressive symptoms frequently co‐occur with symptoms of stress and anxiety; c) antidepressants have a long latency time of several weeks; and d) depression in primary care or outpatient settings frequently starts with mild symptoms, which are not severe enough to warrant long‐term conventional antidepressant treatment.

Primary care physicians sometimes prescribe brief courses of benzodiazepines to patients with mild to moderate major depression, who represent the majority of their depression caseload (Rijswijk 2007). However, most depression treatment guidelines do not support this indication (Furukawa 2001; NICE 2009; Van Marwijk 2003). Evidence of a specific antidepressant effect of benzodiazepines as a single treatment is inconclusive, although benzodiazepines can have additional effects when combined with antidepressants (Furukawa 2001; NICE 2009). Caution with long‐term psychotropic drugs, as well as with high‐potency tranquillisers, such as alprazolam, may however be a good clinical policy (Committee 1980). Benzodiazepines may lose their efficacy with long‐term administration (Committee 1980).

How the intervention might work

Alprazolam, a triazolo 1,4‐benzodiazepine, is one of the high‐potency benzodiazepines. Early claims were that it combined an anxiolytic effect with a specific and fast‐onset antidepressant effect (Sethy 1982). Alprazolam differs from the classic benzodiazepines by the incorporation of a triazolo ring in the basic molecular structure. The addition of this ring is believed to have provided alprazolam with antidepressant properties. Benzodiazepines bind to a specific area of the GABA‐A benzodiazepine receptor and may modulate transmission of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA as agonists, by their allosteric actions facilitating the opening of the receptor's chloride channel.

No independent systematic evaluation of its antidepressant effect has ever been undertaken. In daily practice, a number of patients still use alprazolam. Although as a class benzodiazepines act rapidly and are well tolerated for anxiety, their use presents clinical issues such as dependence, rebound anxiety, memory impairment and discontinuation syndrome (Schweizer 1998). Accident‐proneness, including traffic accidents and falls, are other particularly important considerations (Barbone 1998). These side effects occur early in the course of treatment (Neutel 1996).

Why it is important to do this review

As doubts about the magnitude of the specific antidepressant effect of antidepressants remain, it may be worthwhile to evaluate alternatives (Moncrieff 2004). One non‐systematic review in 1995 showed that benzodiazepines were less effective than conventional antidepressants in treating major depression (Birkenhager 1995). Alprazolam is internationally registered for the treatment of anxiety, panic disorder and anxiety associated with depression (Jonas 1993). However, there is still debate about its efficacy for the treatment of depression alone (Petty 1995). Therefore, a systematic review to evaluate whether alprazolam is a suitable alternative for outpatients with major depression, requiring drug treatment but not wishing to take conventional antidepressants, may generate clinically useful information.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness, including tolerability and acceptability, of alprazolam as monotherapy for major depression in comparison with placebo and conventional antidepressants in outpatients and patients in primary care.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We selected double‐blind randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Double‐blind indicates that both provider and participant are unaware of the exact nature of the intervention or control. We did not apply any language restriction and we included both published and unpublished trials.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics and setting

Trial participants were adults (18 years of age and over), both male and female.

Diagnosis

The primary diagnosis for trial participants was major depression according to the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (Feighner 1972); Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM III (APA 1980) or DSM IV (APA 1994)); a depressive episode according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (WHO 2003); or if the clinician considered the patient to be depressed and eligible for antidepressant treatment.

Setting

Studies were included if they were conducted in an outpatient or primary care setting. However, studies conducted in mixed inpatient and outpatient settings were included in the review.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded patients with a primary diagnosis of another major psychiatric condition, such as anxiety disorder, or important medical problems.

We excluded studies limited to inpatient populations, as the severity of their depressive symptoms is likely to be considerably higher (Hubain 1990; Lenox 1984). Hubain 1990

Types of interventions

Intervention

At least one of the treatment arms had to include alprazolam as a monotherapy (variable dosages and exposure times). There were no restrictions on dose or duration of treatment. We excluded studies that combined alprazolam with other interventions, such as alprazolam plus forms of psychotherapy.

Control conditions

Alprazolam had to be compared with placebo, conventional antidepressants or both.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

1) Our primary continuous outcome was the last mean assessment score on a depression severity measure (end of trial): Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), or the equivalent Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) in an intention‐to‐treat analysis (Hamilton 1960; Montgomery 1979). The primary dichotomous outcome was 'improvement of depression' which was dichotomised as 50% reduction on the initial mean depression severity score (end of trial HDRS or MADRS). We used the HDRS‐based response as the primary outcome measure when multiple measures were reported.

Secondary outcomes

2) Our primary measure of harm was the number of reported drug adverse events and data on tolerability, which were abstracted by collecting 'all‐cause' withdrawals from each treatment group, including the reason attributed for withdrawal from therapy (lack of efficacy and adverse effects).

3) We assessed withdrawals, rebound symptoms and tolerance, which may not have been manifested as a loss of efficacy due to concomitant dose increase.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified relevant trials from systematic searches in the following electronic databases: CCDANCTR‐Studies and CCDANCTR‐References (Specialised Registers of the Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group. For a description see Appendix 1).

We also carried out complementary searches in: PubMed, EMBASE (Elsevier, EMBASE and MEDLINE combined) and PsycINFO.

We conducted searches using a controlled vocabulary of terms related to ALPRAZOLAM, DEPRESSIVE DISORDERS and DEPRESSION (using the APA Thesaurus of Psychological Index Terms in PsycINFO, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) in PubMed, and EMTREE in EMBASE.com). Search strategies are listed below:

CCDANCTR‐Studies

Diagnosis = Depress* or Dysthymi* or "Adjustment Disorder*" or "Mood Disorder*" or "Affective Disorder" or "Affective Symptoms" AND Intervention = Alprazolam

CCDANCTR‐References

Keyword = Depress* or Dysthymi* or "Adjustment Disorder*" or "Mood Disorder*" or "Affective Disorder" or "Affective Symptoms" AND Free‐text = Alprazolam

PubMed (MEDLINE)

("Depressive Disorder"[mh] OR Depression[mh]) AND "Alprazolam"[mh] AND humans[mh] NOT case reports[pt]

EMBASE.com

'major depression'/exp AND 'alprazolam'/de AND [humans]/lim NOT 'case report'/exp OR 'major depression'/exp AND 'alprazolam'/dd_ae,dd_ct

PsycINFO

DE=("depression emotion" OR "major depression") AND DE="alprazolam"

Searching other resources

Reference lists

We checked the reference lists of selected reviews and published studies. We also searched for additional trials in the reference lists of studies initially identified and by scrutinising other relevant review articles.

Personal communication

We consulted authors of studies included and experts in the field to find out if they know of any relevant published or unpublished RCTs, which had not been identified through the electronic searches. We mailed and emailed four traceable authors, however they were unable to provide any information.

Pharmaceutical companies

We also contacted the company that had developed alprazolam.

Unpublished studies

We searched the World Health Organization (WHO) trials portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/), Clinical Studies Results (http://www.clinicalstudyresults.org/) and Current Controlled Trials (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/) for ongoing trials on depression.

We searched the four open databases suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions as suitable for locating grey literature for alprazolam and Xanax. We searched Open Sigle (opensigle.inist.fr), the National Technical Information Service (NTIS), which provides access to the results of both US and non‐US government‐sponsored research (www.ntis.gov), PsycExtra (www.apa.ort/psycextra) and Healthcare Management Information Consortium (HMIC). The large literature databases we used cover conference reports and abstracts published in journals.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed the abstracts from all the studies potentially eligible for inclusion against relevant study inclusion criteria (FW, HvM). We made decisions about selection of studies through discussion and consensus. Any disagreement was resolved through consultation with an independent third party (GA).

Data extraction and management

Both review authors extracted data independently on the inclusion and exclusion criteria for each study, the dose and regimen of alprazolam and the medication or placebo compared, the number of patients randomised, dropouts, length of follow‐up, age, in or outpatient status, relevant clinical outcomes reported (such as HDRS score) and also noted side effects. Any disagreement about the data extraction process was resolved through discussion and consensus, or through consultation with GA. We used the results of the data extraction mainly to consider the generalisability of study findings (external validity) and to evaluate clinical heterogeneity across trials. We set no minimum quality score for inclusion.

Comparisons

Alprazolam versus placebo

Alprazolam versus tricyclic antidepressants

Alprazolam versus heterocyclic antidepressants

Alprazolam versus SSRIs

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias for each included study using the Cochrane Collaboration 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2009). We considered the following six domains:

Sequence generation: was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Allocation concealment: was allocation adequately concealed?

Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors for each main outcome or class of outcomes: was knowledge of the allocated treatment adequately prevented during the study?

Incomplete outcome data for each main outcome or class of outcomes: were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

Selective outcome reporting: are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

Other sources of bias: was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias? Additional items included here are therapist qualifications, treatment fidelity and researcher allegiance/conflict of interest.

We provided a description of what was reported to have happened in each study, and made a judgement on the risk of bias for each domain within and across studies, based on the following three categories: low risk of bias, unclear risk of bias and high risk of bias.

Two independent review authors assessed the risk of bias in the selected studies. Any disagreement was discussed with a third review author. Where necessary, we contacted the authors of the studies for further information. All 'Risk of bias' data are presented graphically and described in the text.

Two review authors (FW, (AB) and HvM) independently assessed the methodological quality or internal validity of each trial using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions criteria (Higgins 2009).

Measures of treatment effect

Standardised mean differences (SMD) are reported for continuous outcomes, together with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The SMD is the difference between the group means divided by the combined standard deviation. We used these to calculate a standard measure of effect for each trial. We calculated the mean difference (MD) where the same outcome scale was used. We defined change in mood at the end of treatment as the outcome of interest. We selected observer‐rated measures in preference to patient‐rated ones as we expected these to be employed most consistently at the time that most alprazolam studies were undertaken. Many different outcome measures are used in depression studies. It is assumed that these all measure an underlying construct which we called mood. We reported both risk ratios (RR) and risk differences (RD) for dichotomous data, as RRs are more precise and RDs allow calculation of numbers needed to treat to benefit (NNTb) and numbers needed to treat to harm (NNTh), with 95% CI for those studies which were statistically significant.

Unit of analysis issues

We expected few problems in this area, as most studies used participants as the unit of analysis. Some studies had multiple treatment groups. We used the relevant data separately in each comparison (alprazolam versus placebo, alprazolam versus other antidepressant). Where more than one active treatment group with the same drug was eligible for inclusion in a comparison, we pooled the groups for comparison against the control group, to avoid including the same group of participants twice in the same meta‐analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We either analysed missing continuous data on an endpoint basis, including only participants with a final assessment, or analysed them using last observation carried forward to the final assessment (LOCF) if LOCF data had been reported by the trial authors.

For dichotomous outcomes, we assigned the worst possible outcome to dropouts (intention‐to‐treat). As many of the studies on the antidepressant effects of alprazolam were published some years ago, it was difficult to recover missing data. To estimate standard deviations (SDs), we used the method described by Furukawa et al (Furukawa 2006). Where data were available in graphic format only, we made an approximation of the mean to assess the outcomes.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We explored inconsistency across studies visually. We also used a Chi2 test, the Q‐statistic, with a P value set at 0.1. Furthermore, we used the I2 statistic, a measure of effect size estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins 2009), with 30% to 50% representing moderate heterogeneity, 50% to 80% substantial, and 80% to 100% considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We addressed publication bias and other reporting biases by means of visual inspection for signs of asymmetry, and generated the funnel plots using Review Manager 5.1 software (RevMan 2011).

Data synthesis

We pooled discrete outcomes (recovered/not recovered) and, where possible, continuous outcomes, using both fixed and random‐effects approaches. Fixed‐effect models assume that the underlying true treatment effect in each trial is the same and that the observed differences are due to chance. Random‐effects models assume the true treatment effects in different trials are randomly placed around some central value and incorporates the within and between‐study variation into the calculation, generating a wider confidence interval if heterogeneity is present, and allowing for an appropriate degree of statistical caution (DerSimonian 1986). The fixed‐effect approach used was the Mantel‐Haenszel‐Peto method which allows the calculation of an estimate known as the 'typical' or pooled odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval (DerSimonian 1986). We chose random‐effects models when there was more than 50% heterogeneity.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform two subgroup analyses for:

speed of recovery; and

alprazolam dosage.

Given that these trial characteristics may have influenced the observed treatment effect, they were planned to identify potential sources of heterogeneity. The use of multiple statistical analyses leads to an increase in the probability of type I errors.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform two sensitivity analyses to determine whether certain methodological decisions made during the review process were robust. We planned to test these decisions by removing studies from the main analysis to investigate the effect of their inclusion. The following two analyses were planned:

to test the inclusion of studies with divergent diagnostic criteria for depression; and

to test the reliance on self reported measures of depression only.

We also conducted a post hoc sensitivity analysis:

to investigate the effects of bias on the results of the meta‐analysis by excluding studies classified as having a high risk of bias.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies.

Results of the search

Electronic searches

The search of the CCDAN registers yielded 391 references of potentially eligible studies. We excluded papers that were not relevant (mainly because they did not fulfil the inclusion criteria or were non‐randomised studies). We included 21 randomised controlled alprazolam trials. Seven studies used a placebo comparison (n = 771) and 18 used tricyclic or heterocyclic antidepressants (n = 1697). The studies typically lasted four to six weeks.

Reference lists

We found three reviews of alprazolam by checking the reference lists of selected reviews and published studies (Birkenhager 1995; Jonas 1993; Srisurapanont 1997). The findings of these other reviews are summarised below in the Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews section. No additional studies were found through checking reference lists.

Personal communication

Few authors of included studies were available for advice on relevant published or unpublished RCTs not identified through electronic searches. We contacted one author (Carl Rickels). No new studies were identified.

Pharmaceutical companies

We contacted the company that developed alprazolam: the Upjohn Company. In 1995, Upjohn merged with Pharmacia AB to form Pharmacia & Upjohn. Today, through a series of mergers, the remainder of Upjohn is owned by Pfizer. The Dutch branch of Pharmacia/Pfizer was unable to provide information as alprazolam is no longer a priority or a marketable drug for them. Alprazolam is generically available.

Unpublished studies

We found no unpublished studies in the World Health Organization (WHO) trials portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/), in Clinical Studies Results (http://www.clinicalstudyresults.org/) or in Current Controlled Trials (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/). The latter database is where we expected pharmaceutical companies to post their results (although alprazolam is mainly prescribed for anxiety and panic disorders).

We searched the three open databases advised in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions as suitable for locating grey literature for alprazolam and Xanax, but we found no relevant information for our research question. The fourth database mentioned, the Healthcare Management Information Consortium (HMIC), is only accessible through a license at OVID. Our two universities do not have such a license. The search results were: Open Sigle (opensigle.inist.fr) (two hits, none relevant); the National Technical Information Service (NTIS) which provides access to the results of both US and non‐US government‐sponsored research (www.ntis.gov) (five hits, none relevant); and PsycExtra (www.apa.org/psycextra) (one hit, but again not relevant).

Included studies

Design

Length of the studies

Five studies were four‐week trials (Banerji 1989; Bassi 1990; Cropper 1987; di Perri 1990; Imlah 1985). One study was a five‐week trial (Mendels 1986). Fifteen studies were six‐week trials (Ansseau 1984; Borison 1989; Draper 1983; Fabre 1980; Feighner 1983a; Goldberg 1986; Laakman 1995; Lapierre 1994; Murthy 1991; Overall 1987; Remick 1988; Rickels 1985; Rickels 1987; Rush 1985; Singh 1988).

Sample size

The mean number of participants who entered the studies was 129.2 (SD 111.5), with a minimum sample size of 43 (Lapierre 1994) and a maximum of 504 (Rickels 1985).

Setting

In 19 studies, the participants were outpatients (Ansseau 1984; Banerji 1989; Bassi 1990; Borison 1989; Cropper 1987; Draper 1983; Fabre 1980; Feighner 1983a; Goldberg 1986; Laakman 1995; Lapierre 1994; Mendels 1986; Murthy 1991; Overall 1987; Remick 1985; Remick 1988; Rickels 1985; Rickels 1987; Singh 1988). Two studies included both in‐ and outpatients, and one study failed to provide information about the setting (di Perri 1990; Imlah 1985; Rush 1985).

Participants

Age

Studies were limited to adults and excluded elderly patients (one used 55 years of age as the upper age limit, four used 60, five used 65, eight used 69/70 and one used 75). Two studies did not provide any details on age (Murthy 1991; Remick 1988).

Diagnosis

Most patients were diagnosed with depressive disorder according to explicit diagnostic criteria (16 studies), with added severity criteria. In 14 studies, a Raskin Depression Scale (RDS) score of at least six (Banerji 1989), eight (Ansseau 1984; Draper 1983; di Perri 1990; Fabre 1980; Feighner 1983a; Laakman 1995; Lapierre 1994; Murthy 1991; Rickels 1985; Rickels 1987; Singh 1988) or nine was added (Bassi 1990; Raskin 1970). In 16 studies, a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) score of at least 17 (Draper 1983), 18 (Bassi 1990; Borison 1989; di Perri 1990; Fabre 1980; Feighner 1983a; Goldberg 1986; Laakman 1995; Lapierre 1994; Murthy 1991; Rickels 1985; Rickels 1987; Rush 1985; Singh 1988), 20 (Mendels 1986) or 21 (Remick 1985; Remick 1988) was required. The Covi Anxiety Score (CAS) had to be less than or equal to the RDS score in many studies (Ansseau 1984; Banerji 1989; di Perri 1990; Draper 1983; Feighner 1983a; Goldberg 1986; Lapierre 1994; Mendels 1986; Murthy 1991; Rickels 1985; Rickels 1987; Singh 1988), while anxiety was not addressed in seven studies (Bassi 1990; Borison 1989; Covi 1976; Laakman 1995; Overall 1987; Remick 1988; Rush 1985).

Diagnostic criteria were:

DSM‐III or its predecessors (Bassi 1990; di Perri 1990; Goldberg 1986; Murthy 1991; Rickels 1987); the Feighner Diagnostic Criteria (di Perri 1990; Draper 1983; Feighner 1983a; Goldberg 1986; Mendels 1986; Murthy 1991; Overall 1987; Rickels 1985; Rickels 1987); or the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (Remick 1985; Remick 1988; Rush 1985);

ICD‐9 (di Perri 1990; Laakman 1995; Singh 1988); or

unspecified criteria (Ansseau 1984; Banerji 1989; Cropper 1987; Imlah 1985; Lapierre 1994).

Two studies included patients with anxiety: mixed symptoms of anxiety and depression, and neurotic depression with or without anxiety (Cropper 1987; Imlah 1985).

Interventions

Eight studies included a placebo arm (Borison 1989; Fabre 1980;Feighner 1983a; Imlah 1985; Laakman 1995; Mendels 1986; Rickels 1985; Rickels 1987). Three studies presented a comparison between four arms (alprazolam‐amitriptyline‐lorazepam‐placebo, alprazolam‐amitriptyline‐doxepin‐placebo and alprazolam‐imipramine‐diazepam‐placebo, respectively (Laakman 1995; Rickels 1985; Rickels 1987). One study presented a comparison between three arms (alprazolam‐imipramine‐placebo) (Mendels 1986). In seven studies, alprazolam was compared with amitriptyline (Banerji 1989; Imlah 1985; Laakman 1995; Lapierre 1994; di Perri 1990; Rickels 1985; Rush 1985; Singh 1988). In six studies it was compared with imipramine (Feighner 1983a; Goldberg 1986; Mendels 1986; Murthy 1991; Overall 1987; Rickels 1987). In five separate studies it was compared with other heterocyclic antidepressants ('other TCAs'): mianserin (Bassi 1990), dothiepin (Cropper 1987), desipramine (Remick 1985; Remick 1988) or doxepin (Rickels 1985).

Dosage of study drugs

The maximum alprazolam dose allowed was within the recommended therapeutic range for anxiety (1.5 to 8 mg; Bandelow 2008) in all studies. The mean alprazolam dose (2.9 mg; SD 0.7) was also within the recommended therapeutic range in all studies, although it was not reported in one study (Imlah 1985). Doses therefore did not seem to be extraordinarily high. Drugs in the control groups were within the recommended therapeutic range, although there was considerable variation in the mean dose between control groups. One further option is to classify mean dosages for the purposes of subgroup analyses in the first revision.

Outcomes

For the continuous outcomes, the HDRS was used in all but two studies (Cropper 1987; Imlah 1985). Dichotomous outcomes, a 50% reduction of the initial depression score, were reported in six studies (di Perri 1990; Laakman 1995; Lapierre 1994; Mendels 1986; Rickels 1987; Rush 1985). All studies reported all‐cause withdrawals, but withdrawals due to adverse effects and ineffectiveness were not specified in five studies (Feighner 1983a; Lapierre 1994; Murthy 1991; Rickels 1987; Rush 1985) and 10 studies respectively (Cropper 1987; di Perri 1990; Feighner 1983a; Goldberg 1986; Imlah 1985; Lapierre 1994; Mendels 1986; Murthy 1991; Rickels 1987; Rush 1985).

Sponsorship

Seven studies were clearly supported by the manufacturer of alprazolam (Cropper 1987; Goldberg 1986; Imlah 1985; Remick 1988; Rickels 1985; Rickels 1987; Rush 1985) and although the other studies did not offer any disclosures in the text, they were remarkably similar in methodology, suggesting sponsorship by the manufacturer of alprazolam in all studies.

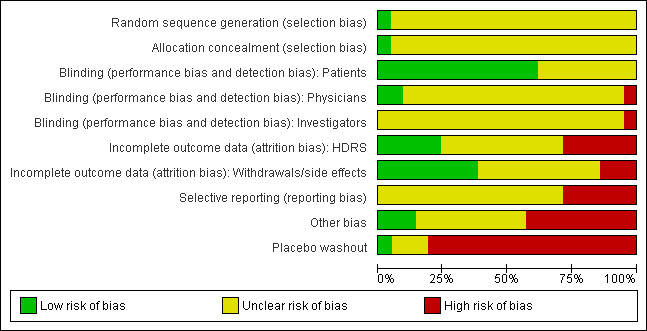

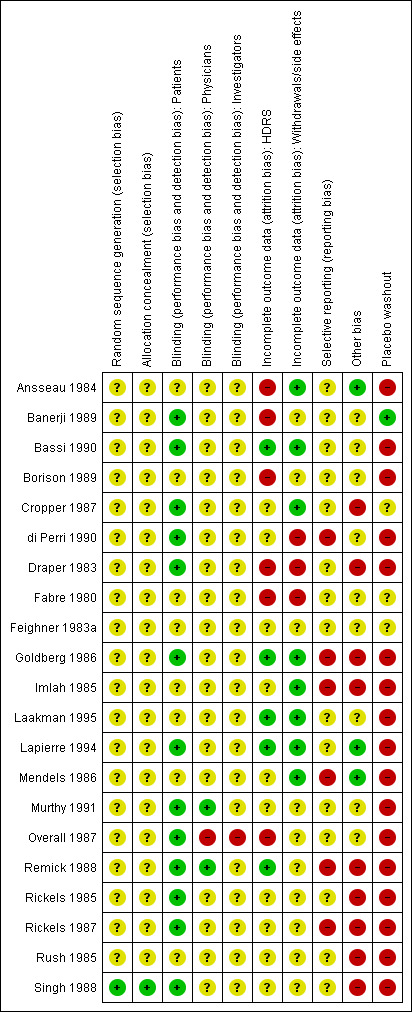

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 1 and Figure 2 for a graphical summary of the methodological quality for the 22 included studies. Most of the studies were older, and many of the recent developments to enhance the quality of reporting of clinical trials such as the requirement of a CONSORT statement did not apply at that time. On the basis of the assessments, we considered six studies to have a high risk of bias (Ansseau 1984; Banerji 1989; Borison 1989; Draper 1983; Fabre 1980; Overall 1987). One study we presumed to be a duplicate of another study by the same authors and so we considered it a secondary reference to that study (Remick 1985).

1.

2.

Allocation

All studies were reported to be randomised trials, however only one study reported sufficient details on allocation, and used a computer‐generated randomisation list (Singh 1988).

Blinding

All studies were reported to be double‐blind trials, however none of the studies reported sufficient details on blinding. The best study described that weekly assessments were completed by the research psychiatrist (Remick 1988), but did not further describe the blinding procedures. Independent outcome assessment was a rarity and was scored unclearly at best in most studies.

Incomplete outcome data

To have adequately addressed incomplete outcome data, studies had to demonstrate that an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis was performed based on all persons randomised, or that attrition was balanced in numbers with similar reasons for dropout across treatment groups, or that outcome data were complete. Incomplete outcome data were judged to have been adequately addressed in eight studies.

Selective reporting

We only included trials in which the primary outcome was severity of depressive symptoms. However, trial investigators may have used still other depression rating scales, and only reported data from the scale that showed a positive effect. Investigators may have also selectively reported outcomes at the time point(s) at which the largest effect was found. Selective reporting was difficult to assess as few trials had pre‐published study protocols.

Other potential sources of bias

Over half of the included studies were explicitly supported by the manufacturer of alprazolam. Another potential source of bias is the placebo washout phase that all studies bar two used before entry (Banerji 1989; Cropper 1987).

Effects of interventions

1. Alprazolam versus placebo

Primary outcome

1.1 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) end of trial

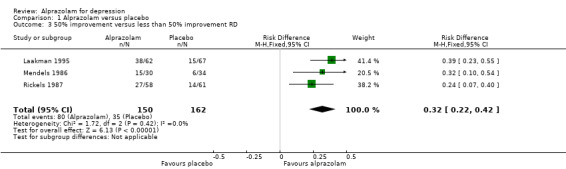

Alprazolam produced a moderately better effect than placebo, based on data from seven studies and 771 persons. For continuous depression severity, the mean difference (MD) was ‐5.34 (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐7.48 to ‐3.20; I2 = 68%), which was higher than the UK National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) cut‐off of three as being clinically meaningful. When applying a sensitivity analysis to exclude the two studies of low quality, with 131 participants, the MD changed slightly to ‐6.22 (95% CI ‐7.42 to ‐5.02; I2 = 23%; fixed‐effect model). For depression severity, dichotomised as a 50% reduction in the initial mean depression severity score, the risk ratio (RR) was 2.47 (95% CI 1.78 to 3.43; I2 = 0%; fixed‐effect model), but only three studies with 312 participants, none of them high‐risk, were available for this comparison. The risk difference (RD) was 0.32 (95% CI 0.22 to 0.42; I2 = 0%; fixed‐effect model) and the number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) was 3 (95% CI 2 to 5).

Secondary outcomes

1.2 Tolerability

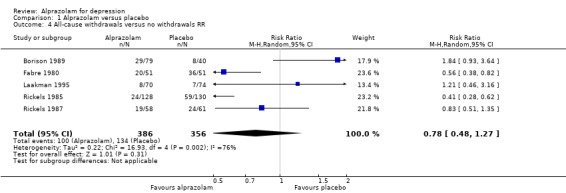

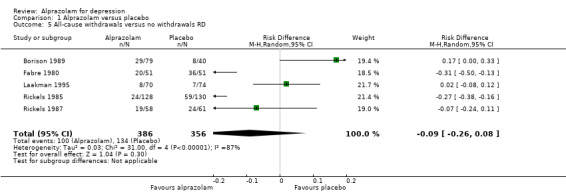

Tolerability was expressed as all‐cause withdrawals, based on data from four studies and 640 participants. The RR of all‐cause withdrawals was 0.78 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.27; I2 = 76 %; random‐effects model) for alprazolam versus placebo, indicating that alprazolam did not result in significantly more all‐cause withdrawals than placebo. Without two high‐risk studies , this was 0.68 (95% CI 0.37 to 1.26; I2 = 72%; random‐effects model). The RD was ‐0.09 (95% CI ‐0.26 to 0.08 ; I2 = 87 %; random‐effects model); without the high‐risk studies it was ‐0.11 (95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.09; I2 = 87%; random‐effects model). The number needed to treat to harm (NNTH) was 11 (95% CI 4 to 13 ). Drowsiness, dry mouth and dizziness were more common among alprazolam users than placebo users.

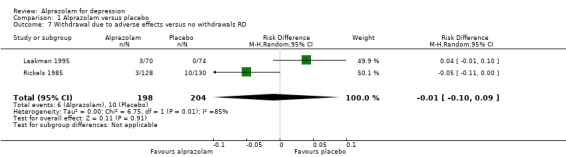

1.2 Adverse effects

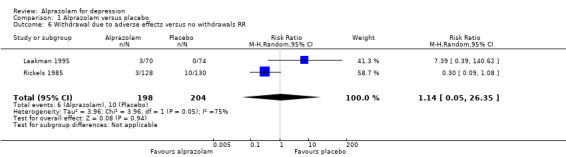

For alprazolam versus placebo, the RR of withdrawals due to adverse effects was 1.14 (95% CI 0.05 to 26.35; I2 = 75%; random‐effects model), based on data from two studies with 402 participants. The RD was ‐0.01 (95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.09; I2 = 85%; random‐effects model). The NNTH was 25 (95% CI ‐8 to 58).

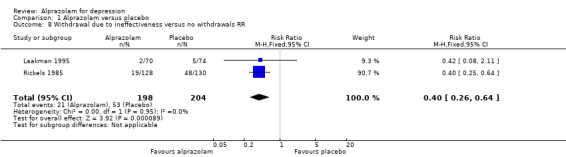

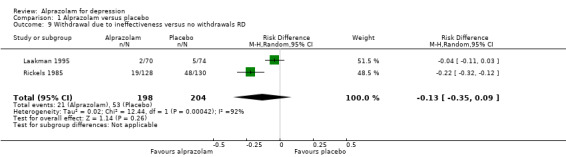

1.3 Lack of efficacy

For alprazolam versus placebo, the RR of withdrawals due to ineffectiveness was 0.40 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.64; I2 = 0%; fixed‐effect model) favouring alprazolam over placebo, with a RD of ‐0.13 (95% CI ‐0.35 to 0.09; I2 = 92%; random‐effects model) and a NNTH of 8 (95% CI 3 to 11), in two studies with 402 participants.

Subgroup analysis

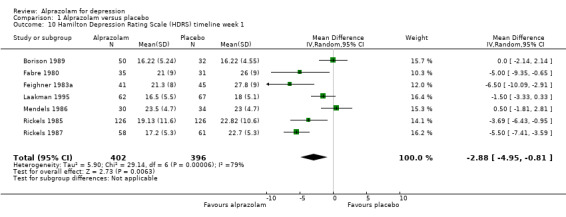

Speed of recovery

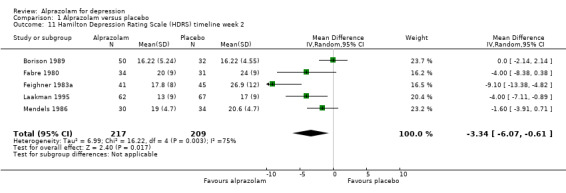

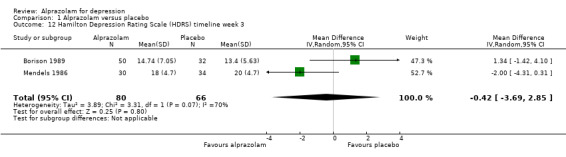

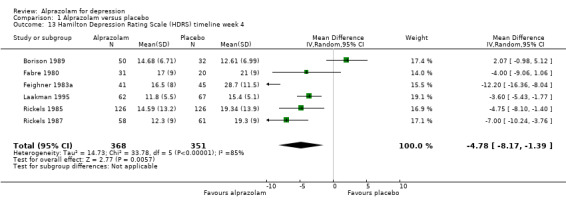

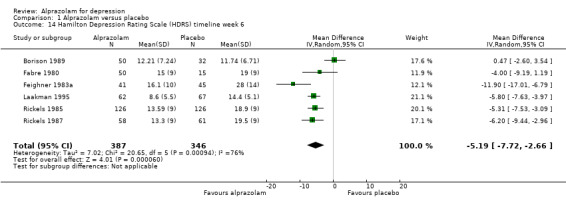

For alprazolam versus placebo, the following MD pattern for depression severity emerged, favouring alprazolam over placebo at all time points but three weeks: ‐2.88 (95% CI ‐4.95 to ‐0.81; I2 = 79%) at one week; ‐3.34 (95% CI ‐6.07 to ‐0.61; I2 = 75%) at two weeks; ‐0.42 (95% CI ‐3.69 to 2.85; I2 = 70%) at three weeks; ‐4.78 (95% CI ‐8.17 to ‐1.39; I2 = 85%) at four weeks; and ‐5.19 (95% CI ‐7.72 to ‐2.66; I2 = 76%) at six weeks. Without the high‐risk studies, these results were MD ‐3.20 (95% CI ‐5.66 to ‐0.74; I2 = 82%); ‐4.55 (95% CI ‐8.48 to ‐0.63; I2 = 78%); ‐2.00 (95% CI ‐4.31 to 0.31; single study: no I2 estimate possible); ‐6.58 (95% CI ‐9.96 to ‐3.20; I2 = 80%); and ‐6.07 (95% CI ‐7.33 to ‐4.82; I2 = 46%). All models but the last one were random‐effects.

2. Alprazolam versus tricyclic antidepressants

Primary outcome

2.1 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) end of trial

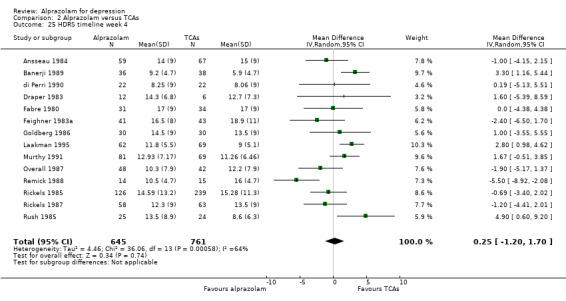

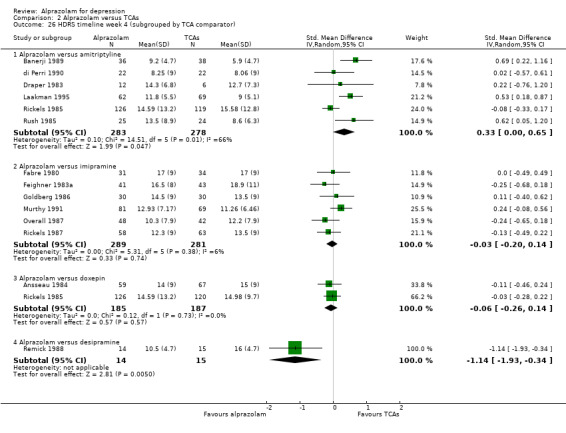

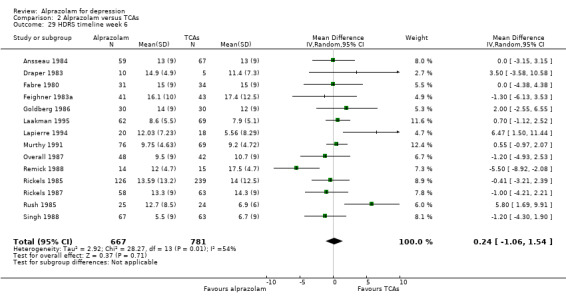

The effect of alprazolam did not differ from the effects of all tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) combined, based on 17 studies and 1636 participants. For continuous depression severity, the pooled mean difference (MD) was 0.25 (95% CI ‐0.93 to 1.43; I2 = 55%; random‐effects model), which was similar to the estimate without the five studies with a high risk of bias: MD 0.06 (95% CI ‐1.40 to 1.52 ; I2 = 63%; random‐effects model). For 50% reduction in the initial mean depression severity score, the RR was 0.86 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.99; I2 = 37%; fixed‐effect model), which was available for 543 participants in seven studies. Without the one high‐risk study, this was 0.87 (95% CI 0.74 to 1.02; I2 = 47%; fixed‐effect model). The RD was ‐0.11 (95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.01; I2 = 58%; random‐effects model); without the one high‐risk study it remained ‐0.11 (95% CI ‐0.26 to 0.04; I2 = 65%, random‐effects model). The NNTB on the basis of the RD was 9 (95% CI 4 to 100). All TCA subgroups gave similar HDRS estimates (amitriptyline, imipramine, doxepin) to alprazolam, except for one study with desipramine, which did worse (‐1.14, 95% CI ‐1.93 to ‐0.34). Amitriptyline produced a better dichotomous HDRS outcome than alprazolam with a RR of 0.77 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.89; I2 = 1%; fixed‐effect model) and a RD of ‐0.19 (95% CI ‐0.30 to ‐0.07; I2 = 27%; fixed‐effect model).

Secondary outcomes

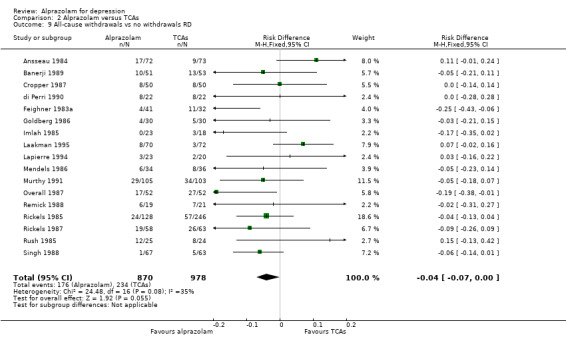

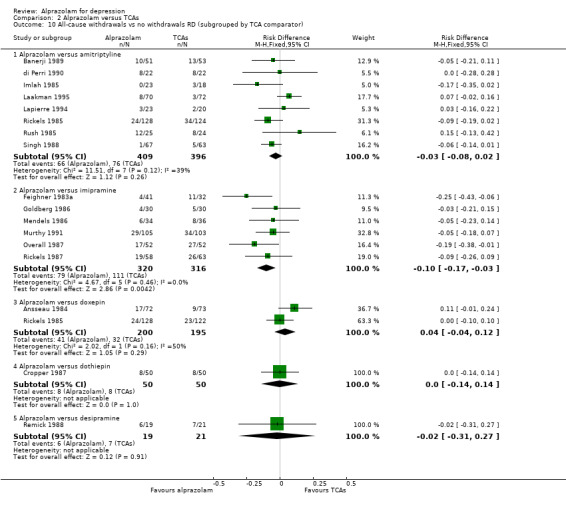

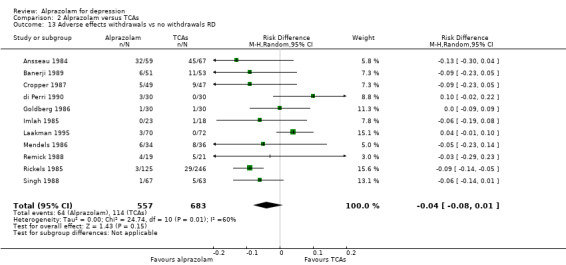

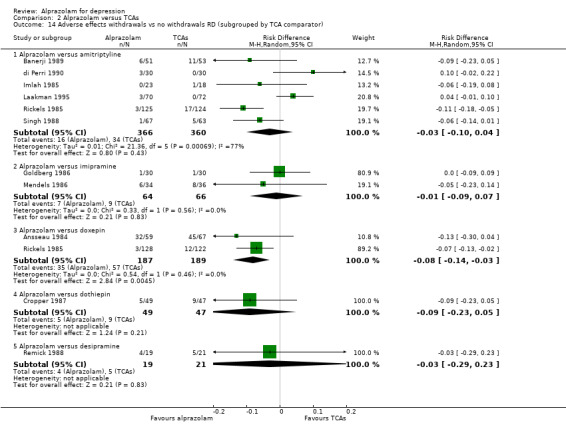

2.2 Tolerability

For alprazolam versus all TCAs, based on data from 18 studies and 1873 participants, the RR for all‐cause withdrawals was 0.84 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.00; I2 = 18%; fixed‐effect model), indicating that alprazolam was better tolerated than the group of TCAs as a whole. Without the four high‐risk studies with 378 participants, the RR was 0.83 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.01; I2 = 9%; fixed‐effect model). The RD was ‐0.04 (95% ‐0.07 to 0.00; I2 = 35%; fixed‐effect model), while without the three high‐risk studies it was still ‐0.04 (95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.00; I2 = 20%; fixed‐effect model). The NNTH was 25 (95% CI 14 to 100). The tolerability of alprazolam did not differ from that of most TCAs, but imipramine had more all‐cause withdrawals (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.90, I2 = 0%; RD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.17 to ‐0.03; I2 = 0%).

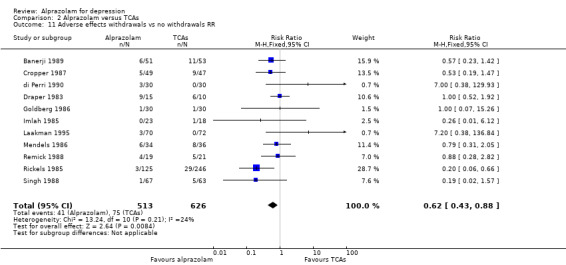

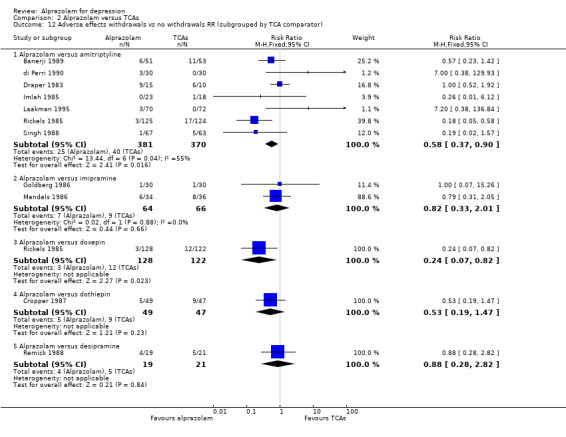

2.3 Adverse effects

For alprazolam versus all TCAs, the RR of withdrawals due to adverse effects was 0.62 (95% CI 0.43 to 0.88; I2 = 24%; fixed‐effect model), in favour of alprazolam, based on 11 studies with 1139 participants. Without the high‐risk studies, the RR was 0.57 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.90; I2 = 28%; fixed‐effect model). However, the RD was only ‐0.04 (95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.01; I2 =60%; random‐effects model) and without the high‐risk studies ‐0.03 (95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.03; I2 = 62%; random‐effects model). The NNTH was 25 (95% CI 11 to 100). Alprazolam had fewer withdrawals due to adverse effects than amitriptyline with a RR of 0.58 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.90, I2 = 55%) but with a RD of ‐0.03 (95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.04, I2 = 77%) and doxepin (RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.82; RD ‐0.08, 95% CI ‐0.14 to ‐0.03).

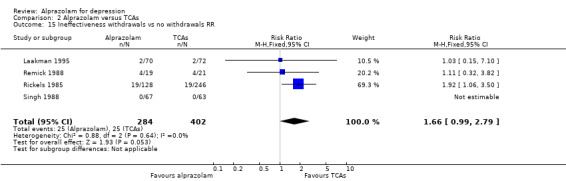

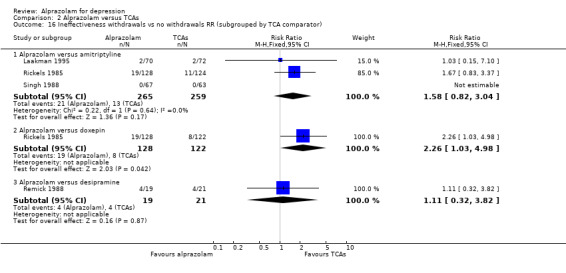

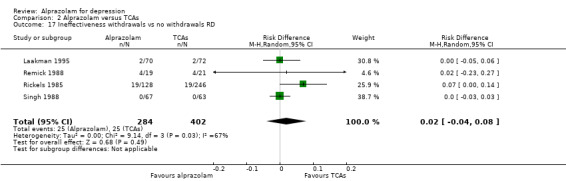

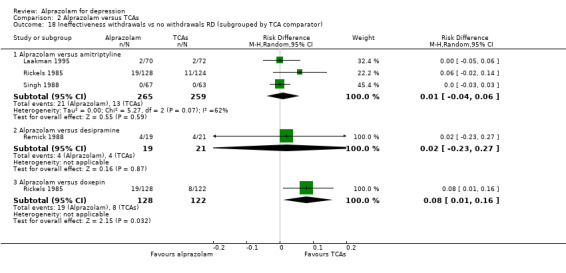

2.4 Lack of efficacy

For alprazolam versus all TCAs, the RR of withdrawals due to lack of efficacy was 1.66 (95% CI 0.99 to 2.79; I2 = 0%; fixed‐effect model), with a RD of 0.02 (95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.08; I2 = 67%; random‐effects model) and a NNTH of 50 (95% CI 25 to 13) in four studies with 686 participants. It had more ineffectiveness withdrawals than doxepin (RR 2.26, 95% CI 1.03 to 4.98; RD 0.08, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.16).

Subgroup analysis

Speed of recovery

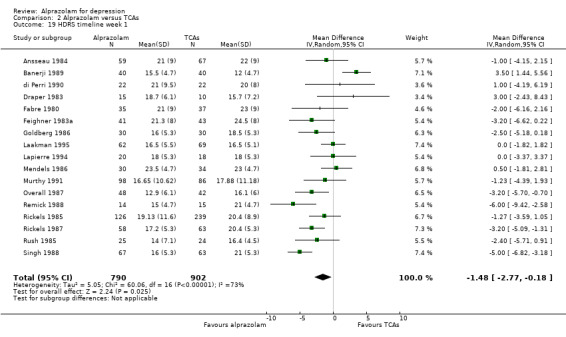

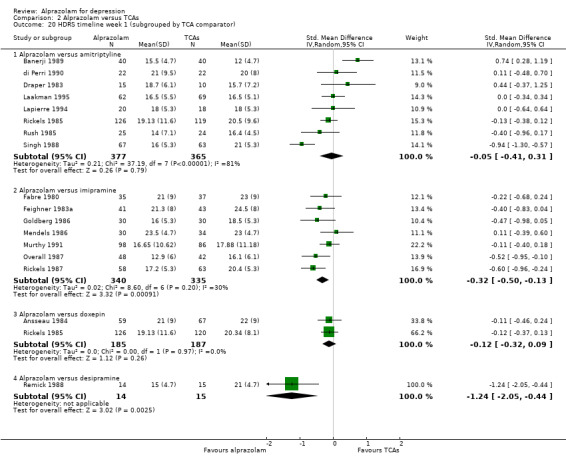

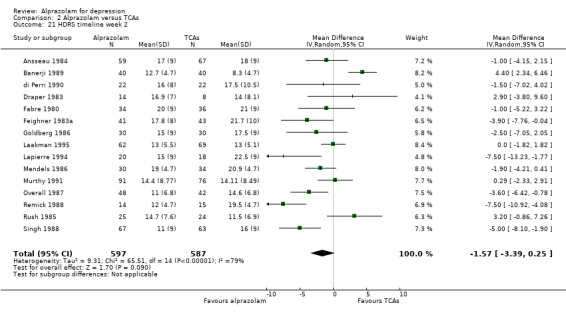

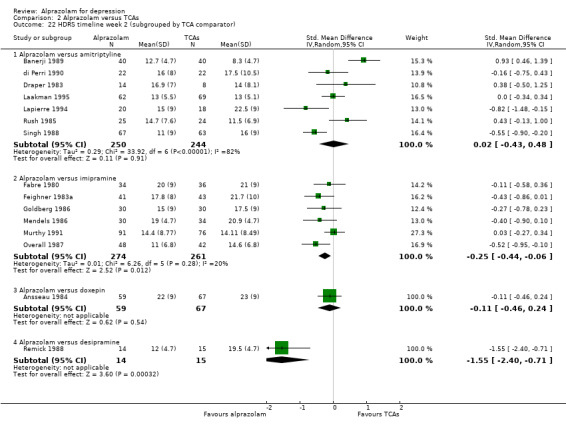

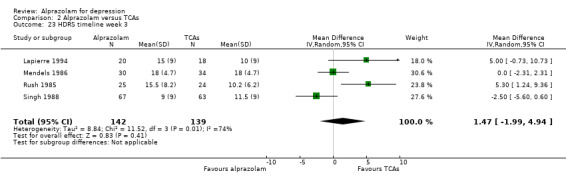

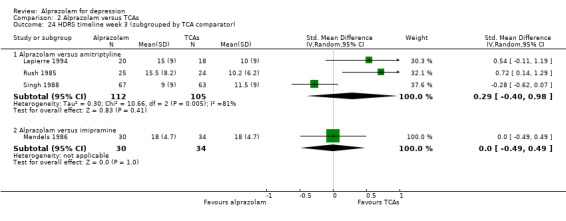

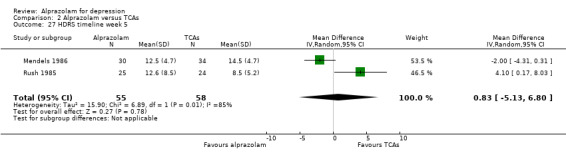

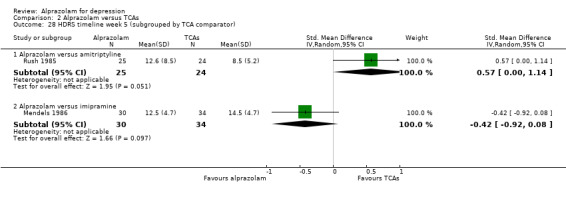

The MD for depression severity for alprazolam versus all TCAs was ‐1.48 (95% CI ‐2.77 to ‐0.18; I2 = 73%) at one week; ‐1.57 (95% CI ‐3.39 to 0.25; I2 = 79%) at two weeks; 1.47 (95% CI ‐1.99 to 4.94; I2 = 74%) at three weeks; 0.25 (95% CI ‐1.20 to 1.70; I2 = 64%) at four weeks; 0.83 (95% CI ‐5.13 to 6.80; I2 = 85%) at five weeks and 0.24 (95% CI ‐1.06 to 1.54; I2 = 54%) at six weeks. At two weeks, the difference lost significance. Without the high‐risk studies, the difference lost significance at three weeks: MD ‐2.04 (95% CI ‐3.30 to ‐0.77; I2 = 64%); ‐2.42 (95% CI ‐4.39 to ‐0.46; I2 = 72%); 1.47 (95% CI ‐1.99 to 4.94 ; I2 = 74%); ‐0.13 (95% CI ‐1.81 to 2.08; I2 = 70%); 0.83 (95% CI ‐5.13 to 6.08; I2 = 85%) and 0.33 (95% CI ‐1.32 to 1.99; I2 = 66%). All models were random‐effects.

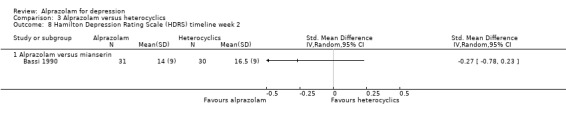

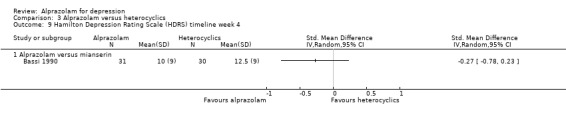

3. Alprazolam versus heterocyclic antidepressants

Primary outcome

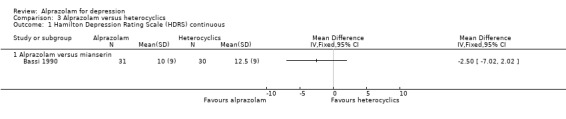

3.1 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) end of trial

The effect of alprazolam did not differ from the effects of mianserin, based on one study and 61 participants: the MD was ‐2.50 (95% CI ‐7.02 to 2.02).

Secondary outcomes

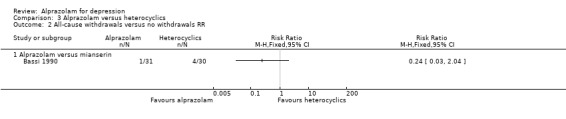

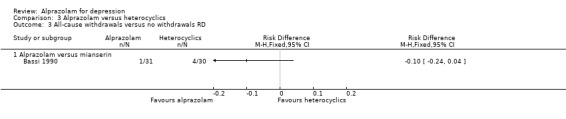

3.2 Tolerability

The RR of all‐cause withdrawals for alprazolam versus mianserin, based on data from one study and 61 participants, was 0.24 (95% CI 0.03 to 2.04), indicating that alprazolam did not result in significantly more all‐cause withdrawals than mianserin. The RD was ‐0.10 (95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.04).

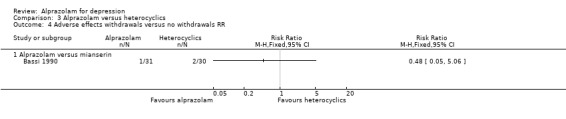

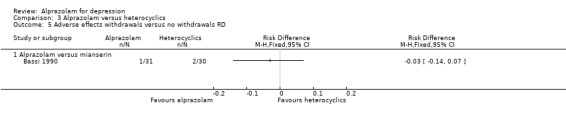

3.3 Adverse effects

For alprazolam versus mianserin, the RR of withdrawals due to adverse effects was 0.48 (95% CI 0.05 to 5.06), with a RD of ‐0.03 (95% CI ‐0.14 to 0.07).

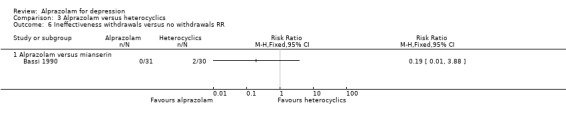

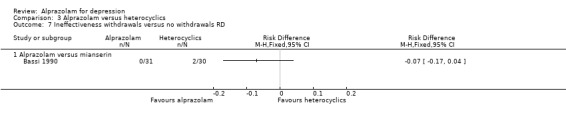

3.4 Lack of efficacy

For alprazolam versus mianserin, the RR of withdrawals due to ineffectiveness was 0.19 (95% CI 0.01 to 3.88), with a RD of ‐0.07 (95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.04).

4. Alprazolam versus SSRIs

We found no trials that assessed the effects of alprazolam versus SSRIs.

Sensitivity analysis

Two of the three planned sensitivity analyses were not considered useful post hoc as all but one study used formal diagnostic criteria (see 'Types of participants' 'Diagnosis'). We were also able to use a physician‐rated outcome for all studies and, therefore, no self reports were required. We added two other sensitivity analyses:

To test the effect of including trials with imputed SD values in three of the seven studies of alprazolam versus placebo, we excluded these, but this did not change the MD much (MD ‐5.35, 95% CI ‐9.29 to ‐1.40; I2 = 83%). Alprazolam did worse than all TCAs combined after we excluded eight studies with imputed SDs, as the MD point estimate became 1.44 (95% CI ‐0.05 to 2.93; I2 = 50%; random‐effects model).

To test for the effect of including sub‐samples of inpatients, we excluded a study on alprazolam versus all TCAs with 17 inpatients of 49 patients available at three weeks who perhaps had a more severe depression (Rush 1985). This did not alter the MD point estimate (‐0.06, 95% CI ‐1.16 to 1.05; I2 = 47%; fixed‐effect model). The other study with some inpatients did not report a usable primary outcome, therefore this study did not affect any of the effect estimates. We could not include it in a sensitivity analysis (Imlah 1985).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Alprazolam versus placebo

At the end of trial, alprazolam was more effective than placebo, based on the mean difference (MD) of ‐5.34 (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐7.48 to ‐3.20; I2 = 68%) of reduction in symptoms on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). The high heterogeneity found for this important comparison indicates that the positive effects of alprazolam in treating depression are to some extent provisional and should be weighed against the potential adverse effects of the medication. However, several studies were of low quality and when applying a sensitivity analysis the results changed to a slightly higher MD of ‐6.22 (95% CI ‐7.42 to ‐5.02), but with less heterogeneity (I2 = 23%).

Based on the dichotomous 50% reduction in the initial mean depression severity scores, alprazolam was also more effective than placebo, with a risk ratio (RR) of 2.47 (95% CI 1.78 to 3.43; I2 = 0%) and risk difference (RD) of 0.32 (95% CI 0.22 to 0.42; I2 = 0%). There was less heterogeneity in this comparison.

Tolerability was expressed as all‐cause withdrawals, with a RR of 0.78 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.27; I2 = 76 %), indicating that alprazolam did not have significantly fewer all‐cause withdrawals than placebo. Leaving the high‐risk studies out did not reduce heterogeneity substantially (I2 = 72%).

Alprazolam versus tricyclic antidepressants

Alprazolam was as effective as its tricyclic comparators. Based on 17 studies and 1636 participants, the pooled mean difference (MD) for depression severity was 0.25 (95% CI ‐0.93 to 1.43; I2 = 55%), which was similar to the estimate without studies with a high risk of bias: MD 0.06 (95% CI ‐1.40 to 1.52; I2 = 63%). However, based on the dichotomous 50% reduction on the initial mean depression severity scores, and considerably fewer studies, alprazolam was less effective than the tricyclics with a RR of 0.86 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.99; I2 = 37%). There was some evidence that alprazolam produces a response faster than placebo and than tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). The RR of all‐cause withdrawals was 0.84 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.00; I2 = 18%) for alprazolam versus the tricyclics, indicating that alprazolam had significantly fewer all‐cause withdrawals. Leaving the high‐risk studies out further reduced heterogeneity (I2 = 9%) in this comparison.

Alprazolam versus heterocyclic antidepressants

The effects of alprazolam did not differ from those of mianserin in any comparison.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Most of the included studies are older trials; comparisons with newer antidepressants would have been informative, but these were not found. We doubt whether there will be many new studies on the subject but in a future update, we will assess anxiety as a secondary outcome as alprazolam’s effect on depression may be due to underlying anxiety. Undiagnosed anxiety disorders or substantial sub‐threshold anxiety symptoms may have placed the benzodiazepine at an advantage. We will also add inpatient studies and a severity subgroup analysis as it may exert its effect on depression through non‐specific sedative effects on improved sleep and reduced agitation, particularly for mild to moderate depression. One of the key limitations of the review is that the crucial issue of dependence on benzodiazepines (and the allied problems of tolerance, dose escalation and difficult withdrawal) cannot be captured by the present methodology. Indeed, it is even possible when using the conventional methodology, including all‐cause withdrawals as the main measure of tolerability, that a drug which causes dependence and is difficult to withdraw from may inevitably be associated with fewer withdrawals than one that does not. After long‐term treatment with benzodiazepines (e.g. over two to eight months), dependency may occur in a substantial number of patients (Bandelow 2008; Rickels 1990; Schweizer 1990), especially in predisposed persons with, for instance, an alcohol problem.

Quality of the evidence

There is ample room for methodological improvement as Figure 1 and Figure 2 show: important quality criteria such as allocation concealment and adequate randomisation procedures were largely absent. Very few studies also used independent outcome assessments: doctors typically assessed subjects themselves. Another potentially worrying issue is publication bias as was demonstrated in other antidepressant studies (Kirsch 2008). The role of the sponsor in the presentation of results could have been large. Many studies, for instance, used exactly the same set of instruments, and it is not clear what results or studies have not been published. Psychotropic drug studies frequently have methodological problems that tend to weaken the contrast between the drug and placebo, and inflate claimed effects (Van Marwijk 2006). To give two examples: many studies used a placebo washout period. This design feature severely limits the ability to generate accurate estimates of the placebo response rate (Fournier 2010). Because early placebo responders are removed from the trial before they can contribute data, the true rate of placebo response may be underestimated in trials that use this feature. Another example is the difficulty of blinding: subjects quickly experience alprazolam's sedative effects. Most of the studies were performed before the publication and implementation of current quality criteria for conducting and reporting randomised controlled clinical trials (CONSORT).

Potential biases in the review process

Although this review has several strengths, such as a pre‐published protocol, an experienced librarian who performed thorough searches, two authors to select studies/data extract/assess risk of bias and a third to resolve disputes, there were also post hoc decisions. The management of antidepressant classes was one. We would have also liked to analyse the effects of alprazolam dosage and the loss of efficacy due to concomitant dose increase but this was not possible due to insufficient data. The review authors have the impression that all studies were in some way sponsored by the pharmaceutical company that manufactured alprazolam. Publication bias cannot be excluded.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There are no related non‐Cochrane systematic reviews, however we did identify three literature reviews (Birkenhager 1995; Jonas 1993; Srisurapanont 1997). In Birkenhager 1995 alprazolam was found to be effective in mild to moderate depression, but inferior to TCAs in patients with endogenous or melancholic depression. It may not cause amelioration of core symptoms. In Jonas 1993 alprazolam demonstrated efficacy for depression, equal in efficacy to comparison agents. Medical events were reported infrequently or not at all for alprazolam and the comparator drugs; there were no marked differences between drug classes. In Srisurapanont 1997, the antidepressant effect of alprazolam was comparable to that of low‐dose TCAs, but the lack of long‐term treatment studies makes the issue of alprazolam's benefits and disadvantages still undetermined. The results of these three reviews are therefore consistent with our findings here.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The best evidence currently available suggests that alprazolam may be moderately more effective than a placebo and as effective as conventional antidepressants in the treatment of major depression. We cannot conclude whether this is due to its specifically antidepressant effect or rather to its non‐specific effect on sleep and anxiety. There were relatively few short‐term side effects. However, the multiple shortcomings of the evidence, including probable sponsorship bias, publication bias, age of the studies and heterogeneity of the results, lessen our confidence in the estimates of its effectiveness based on the currently available evidence. The negative effects of benzodiazepine treatment, such as dependence and withdrawal reactions, cast further doubt on the risk‐benefit ratio of the use of alprazolam as an antidepressant. It is also likely that some participants had undiagnosed anxiety disorders or substantial sub‐threshold anxiety symptoms, which may have placed the benzodiazepine at an advantage.

Implications for research.

We found no studies that compared alprazolam to newer antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which would have been informative. SSRIs are as effective as other antidepressants but may have a more favourable risk–benefit ratio (NICE 2009; Van Marwijk 2003), however, the included studies compared alprazolam to antidepressants which may no longer be used as first‐line treatment for depression. In view of the remarkable similarity of the design of nearly all studies, we have the distinct impression that the manufacturer of alprazolam funded all of them. An independently funded study comparing the effects of alprazolam to placebo or to SSRIs would, therefore, be desirable. Claims of the clinical utility of benzodiazepines would best be tested using a cost‐benefit analysis. All studies looked at short‐term effects, but many of the potential side effects of benzodiazepines, except accident‐proneness, are to be expected in the longer term. Research into the effects of alprazolam in different patient subgroups (the elderly and severely depressed) should be conducted. Investigation of the contribution of possible methodological sources of heterogeneity observed in this study, such as different medication doses, is also warranted. An interesting possibility for future studies would be to evaluate core items on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) (for example, excluding sleep) to consider non‐specific effects.

Acknowledgements

We thank the reviewers of the protocol for their detailed feedback.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CCDANCTR

The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) maintain two clinical trials registers at their editorial base in Bristol, UK: a references register and a studies‐based register. The CCDANCTR‐References Register contains over 25,300 reports of trials in depression, anxiety and neurosis. Approximately 65% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the CCDANCTR‐Studies Register and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique Study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐Psi coding manual. Please contact the CCDAN Trials Search Co‐ordinator for further details.

Reports of trials for inclusion in the Group's registers are collated from routine (weekly), generic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO; quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trials registers c/o the World Health Organization’s trials portal (ICTRP) (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/), drug companies, the handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses.

Details of CCDAN’s generic search strategies can be found in the ‘Specialised Register’ section of the Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group’s module text.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Alprazolam versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) continuous | 7 | 771 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.34 [‐7.48, ‐3.20] |

| 2 50% improvement versus less than 50% improvement RR | 3 | 312 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.47 [1.78, 3.43] |

| 3 50% improvement versus less than 50% improvement RD | 3 | 312 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.22, 0.42] |

| 4 All‐cause withdrawals versus no withdrawals RR | 5 | 742 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.48, 1.27] |

| 5 All‐cause withdrawals versus no withdrawals RD | 5 | 742 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.09 [‐0.26, 0.08] |

| 6 Withdrawal due to adverse effects versus no withdrawals RR | 2 | 402 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.05, 26.35] |

| 7 Withdrawal due to adverse effects versus no withdrawals RD | 2 | 402 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.01 [‐0.10, 0.09] |

| 8 Withdrawal due to ineffectiveness versus no withdrawals RR | 2 | 402 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.26, 0.64] |

| 9 Withdrawal due to ineffectiveness versus no withdrawals RD | 2 | 402 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.13 [‐0.35, 0.09] |

| 10 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) timeline week 1 | 7 | 798 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.88 [‐4.95, ‐0.81] |

| 11 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) timeline week 2 | 5 | 426 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.34 [‐6.07, ‐0.61] |

| 12 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) timeline week 3 | 2 | 146 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.42 [‐3.69, 2.85] |

| 13 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) timeline week 4 | 6 | 719 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.78 [‐8.17, ‐1.39] |

| 14 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) timeline week 6 | 6 | 733 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.19 [‐7.72, ‐2.66] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Alprazolam versus placebo, Outcome 1 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) continuous.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Alprazolam versus placebo, Outcome 2 50% improvement versus less than 50% improvement RR.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Alprazolam versus placebo, Outcome 3 50% improvement versus less than 50% improvement RD.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Alprazolam versus placebo, Outcome 4 All‐cause withdrawals versus no withdrawals RR.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Alprazolam versus placebo, Outcome 5 All‐cause withdrawals versus no withdrawals RD.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Alprazolam versus placebo, Outcome 6 Withdrawal due to adverse effects versus no withdrawals RR.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Alprazolam versus placebo, Outcome 7 Withdrawal due to adverse effects versus no withdrawals RD.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Alprazolam versus placebo, Outcome 8 Withdrawal due to ineffectiveness versus no withdrawals RR.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Alprazolam versus placebo, Outcome 9 Withdrawal due to ineffectiveness versus no withdrawals RD.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Alprazolam versus placebo, Outcome 10 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) timeline week 1.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Alprazolam versus placebo, Outcome 11 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) timeline week 2.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Alprazolam versus placebo, Outcome 12 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) timeline week 3.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Alprazolam versus placebo, Outcome 13 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) timeline week 4.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Alprazolam versus placebo, Outcome 14 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) timeline week 6.

Comparison 2. Alprazolam versus TCAs.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 HDRS continuous | 17 | 1636 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.25 [‐0.93, 1.43] |

| 2 HDRS continuous (subgrouped by TCA comparator) | 17 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Alprazolam versus amitriptyline | 8 | 732 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.12 [‐0.03, 0.27] |

| 2.2 Alprazolam versus imipramine | 7 | 629 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.05 [‐0.21, 0.11] |

| 2.3 Alprazolam versus doxepin | 2 | 372 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.18, 0.22] |

| 2.4 Alprazolam versus desipramine | 1 | 29 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.14 [‐1.93, ‐0.34] |

| 3 50% improvement vs less than 50% improvement RR | 7 | 543 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.75, 0.99] |

| 4 50% improvement vs less than 50% improvement RR (subgrouped by TCA comparator) | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Alprazolam versus amitriptyline | 5 | 358 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.66, 0.89] |

| 4.2 Alprazolam versus imipramine | 2 | 185 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.86, 1.65] |

| 5 50% improvement vs less than 50% improvement RD | 7 | 543 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.11 [‐0.24, 0.01] |

| 6 50% improvement vs less than 50% improvement RD (subgrouped by TCA comparator) | 7 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Alprazolam versus amitriptyline | 5 | 358 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.19 [‐0.30, ‐0.07] |

| 6.2 Alprazolam versus imipramine | 2 | 185 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.08 [‐0.07, 0.22] |

| 7 All‐cause withdrawals vs no withdrawals RR | 18 | 1873 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.72, 1.00] |

| 8 All‐cause withdrawals vs no withdrawals RR (subgrouped by TCA comparator) | 18 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 Alprazolam versus amitriptyline | 9 | 830 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.63, 1.10] |

| 8.2 Alprazolam versus imipramine | 6 | 636 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.56, 0.90] |

| 8.3 Alprazolam versus doxepin | 2 | 395 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.82, 1.90] |

| 8.4 Alprazolam versus dothiepin | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.41, 2.46] |

| 8.5 Alprazolam versus desipramine | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.39, 2.32] |

| 9 All‐cause withdrawals vs no withdrawals RD | 17 | 1848 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.04 [‐0.07, 0.00] |

| 10 All‐cause withdrawals vs no withdrawals RD (subgrouped by TCA comparator) | 17 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10.1 Alprazolam versus amitriptyline | 8 | 805 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐0.08, 0.02] |

| 10.2 Alprazolam versus imipramine | 6 | 636 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.10 [‐0.17, ‐0.03] |

| 10.3 Alprazolam versus doxepin | 2 | 395 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.04 [‐0.04, 0.12] |

| 10.4 Alprazolam versus dothiepin | 1 | 100 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [‐0.14, 0.14] |

| 10.5 Alprazolam versus desipramine | 1 | 40 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.02 [‐0.31, 0.27] |

| 11 Adverse effects withdrawals vs no withdrawals RR | 11 | 1139 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.43, 0.88] |

| 12 Adverse effects withdrawals vs no withdrawals RR (subgrouped by TCA comparator) | 11 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 12.1 Alprazolam versus amitriptyline | 7 | 751 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.37, 0.90] |

| 12.2 Alprazolam versus imipramine | 2 | 130 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.33, 2.01] |

| 12.3 Alprazolam versus doxepin | 1 | 250 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.07, 0.82] |

| 12.4 Alprazolam versus dothiepin | 1 | 96 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.19, 1.47] |

| 12.5 Alprazolam versus desipramine | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.28, 2.82] |

| 13 Adverse effects withdrawals vs no withdrawals RD | 11 | 1240 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.04 [‐0.08, 0.01] |

| 14 Adverse effects withdrawals vs no withdrawals RD (subgrouped by TCA comparator) | 11 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 14.1 Alprazolam versus amitriptyline | 6 | 726 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐0.10, 0.04] |

| 14.2 Alprazolam versus imipramine | 2 | 130 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.01 [‐0.09, 0.07] |

| 14.3 Alprazolam versus doxepin | 2 | 376 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.08 [‐0.14, ‐0.03] |

| 14.4 Alprazolam versus dothiepin | 1 | 96 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.09 [‐0.23, 0.05] |

| 14.5 Alprazolam versus desipramine | 1 | 40 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐0.29, 0.23] |

| 15 Ineffectiveness withdrawals vs no withdrawals RR | 4 | 686 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.66 [0.99, 2.79] |

| 16 Ineffectiveness withdrawals vs no withdrawals RR (subgrouped by TCA comparator) | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 16.1 Alprazolam versus amitriptyline | 3 | 524 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.58 [0.82, 3.04] |

| 16.2 Alprazolam versus doxepin | 1 | 250 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.26 [1.03, 4.98] |

| 16.3 Alprazolam versus desipramine | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.32, 3.82] |

| 17 Ineffectiveness withdrawals vs no withdrawals RD | 4 | 686 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.04, 0.08] |

| 18 Ineffectiveness withdrawals vs no withdrawals RD (subgrouped by TCA comparator) | 4 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 18.1 Alprazolam versus amitriptyline | 3 | 524 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.04, 0.06] |

| 18.2 Alprazolam versus desipramine | 1 | 40 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.23, 0.27] |

| 18.3 Alprazolam versus doxepin | 1 | 250 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.08 [0.01, 0.16] |

| 19 HDRS timeline week 1 | 17 | 1692 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.48 [‐2.77, ‐0.18] |

| 20 HDRS timeline week 1 (subgrouped by TCA comparator) | 17 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 20.1 Alprazolam versus amitriptyline | 8 | 742 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.05 [‐0.41, 0.31] |

| 20.2 Alprazolam versus imipramine | 7 | 675 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.32 [‐0.50, ‐0.13] |

| 20.3 Alprazolam versus doxepin | 2 | 372 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.12 [‐0.32, 0.09] |

| 20.4 Alprazolam versus desipramine | 1 | 29 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.24 [‐2.05, ‐0.44] |

| 21 HDRS timeline week 2 | 15 | 1184 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.57 [‐3.39, 0.25] |

| 22 HDRS timeline week 2 (subgrouped by TCA comparator) | 15 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 22.1 Alprazolam versus amitriptyline | 7 | 494 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.43, 0.48] |

| 22.2 Alprazolam versus imipramine | 6 | 535 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.25 [‐0.44, ‐0.06] |

| 22.3 Alprazolam versus doxepin | 1 | 126 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.11 [‐0.46, 0.24] |

| 22.4 Alprazolam versus desipramine | 1 | 29 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.55 [‐2.40, ‐0.71] |

| 23 HDRS timeline week 3 | 4 | 281 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.47 [‐1.99, 4.94] |

| 24 HDRS timeline week 3 (subgrouped by TCA comparator) | 4 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 24.1 Alprazolam versus amitriptyline | 3 | 217 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.29 [‐0.40, 0.98] |

| 24.2 Alprazolam versus imipramine | 1 | 64 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [‐0.49, 0.49] |

| 25 HDRS timeline week 4 | 14 | 1406 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.25 [‐1.20, 1.70] |

| 26 HDRS timeline week 4 (subgrouped by TCA comparator) | 14 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 26.1 Alprazolam versus amitriptyline | 6 | 561 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.00, 0.65] |

| 26.2 Alprazolam versus imipramine | 6 | 570 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐0.20, 0.14] |

| 26.3 Alprazolam versus doxepin | 2 | 372 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.06 [‐0.26, 0.14] |

| 26.4 Alprazolam versus desipramine | 1 | 29 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.14 [‐1.93, ‐0.34] |

| 27 HDRS timeline week 5 | 2 | 113 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.83 [‐5.13, 6.80] |

| 28 HDRS timeline week 5 (subgrouped by TCA comparator) | 2 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 28.1 Alprazolam versus amitriptyline | 1 | 49 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [‐0.00, 1.14] |

| 28.2 Alprazolam versus imipramine | 1 | 64 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.42 [‐0.92, 0.08] |

| 29 HDRS timeline week 6 | 14 | 1448 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.24 [‐1.06, 1.54] |

| 30 HDRS timeline week 6 (subgrouped by TCA comparator) | 14 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 30.1 Alprazolam versus amitriptyline | 6 | 608 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.08 [‐0.08, 0.24] |

| 30.2 Alprazolam versus imipramine | 6 | 565 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.01 [‐0.17, 0.16] |

| 30.3 Alprazolam versus doxepin | 2 | 372 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.18, 0.22] |

| 30.4 Alprazolam versus desipramine | 1 | 29 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.14 [‐1.93, ‐0.34] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 1 HDRS continuous.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 2 HDRS continuous (subgrouped by TCA comparator).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 3 50% improvement vs less than 50% improvement RR.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 4 50% improvement vs less than 50% improvement RR (subgrouped by TCA comparator).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 5 50% improvement vs less than 50% improvement RD.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 6 50% improvement vs less than 50% improvement RD (subgrouped by TCA comparator).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 7 All‐cause withdrawals vs no withdrawals RR.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 8 All‐cause withdrawals vs no withdrawals RR (subgrouped by TCA comparator).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 9 All‐cause withdrawals vs no withdrawals RD.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 10 All‐cause withdrawals vs no withdrawals RD (subgrouped by TCA comparator).

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 11 Adverse effects withdrawals vs no withdrawals RR.

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 12 Adverse effects withdrawals vs no withdrawals RR (subgrouped by TCA comparator).

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 13 Adverse effects withdrawals vs no withdrawals RD.

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 14 Adverse effects withdrawals vs no withdrawals RD (subgrouped by TCA comparator).

2.15. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 15 Ineffectiveness withdrawals vs no withdrawals RR.

2.16. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 16 Ineffectiveness withdrawals vs no withdrawals RR (subgrouped by TCA comparator).

2.17. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 17 Ineffectiveness withdrawals vs no withdrawals RD.

2.18. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 18 Ineffectiveness withdrawals vs no withdrawals RD (subgrouped by TCA comparator).

2.19. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 19 HDRS timeline week 1.

2.20. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 20 HDRS timeline week 1 (subgrouped by TCA comparator).

2.21. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 21 HDRS timeline week 2.

2.22. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 22 HDRS timeline week 2 (subgrouped by TCA comparator).

2.23. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 23 HDRS timeline week 3.

2.24. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 24 HDRS timeline week 3 (subgrouped by TCA comparator).

2.25. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 25 HDRS timeline week 4.

2.26. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 26 HDRS timeline week 4 (subgrouped by TCA comparator).

2.27. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 27 HDRS timeline week 5.

2.28. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 28 HDRS timeline week 5 (subgrouped by TCA comparator).

2.29. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 29 HDRS timeline week 6.

2.30. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Alprazolam versus TCAs, Outcome 30 HDRS timeline week 6 (subgrouped by TCA comparator).

Comparison 3. Alprazolam versus heterocyclics.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) continuous | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Alprazolam versus mianserin | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 All‐cause withdrawals versus no withdrawals RR | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Alprazolam versus mianserin | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 All‐cause withdrawals versus no withdrawals RD | 1 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Alprazolam versus mianserin | 1 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Adverse effects withdrawals versus no withdrawals RR | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 Alprazolam versus mianserin | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 Adverse effects withdrawals versus no withdrawals RD | 1 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5.1 Alprazolam versus mianserin | 1 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 Ineffectiveness withdrawals versus no withdrawals RR | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6.1 Alprazolam versus mianserin | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7 Ineffectiveness withdrawals versus no withdrawals RD | 1 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 7.1 Alprazolam versus mianserin | 1 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) timeline week 2 | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8.1 Alprazolam versus mianserin | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 9 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) timeline week 4 | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 9.1 Alprazolam versus mianserin | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Alprazolam versus heterocyclics, Outcome 1 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) continuous.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Alprazolam versus heterocyclics, Outcome 2 All‐cause withdrawals versus no withdrawals RR.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Alprazolam versus heterocyclics, Outcome 3 All‐cause withdrawals versus no withdrawals RD.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Alprazolam versus heterocyclics, Outcome 4 Adverse effects withdrawals versus no withdrawals RR.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Alprazolam versus heterocyclics, Outcome 5 Adverse effects withdrawals versus no withdrawals RD.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Alprazolam versus heterocyclics, Outcome 6 Ineffectiveness withdrawals versus no withdrawals RR.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Alprazolam versus heterocyclics, Outcome 7 Ineffectiveness withdrawals versus no withdrawals RD.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Alprazolam versus heterocyclics, Outcome 8 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) timeline week 2.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Alprazolam versus heterocyclics, Outcome 9 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) timeline week 4.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ansseau 1984.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial, 6 weeks | |