Abstract

Many new decision aids are developed while aspects of existing decision aids could also be useful, leading to a sub-optimal use of resources. To support treatment decision-making in prostate cancer patients, a pre-existing evidence-based Canadian decision aid was adjusted to Dutch clinical setting. After analyses of the original decision aid and routines in Dutch prostate cancer care, adjustments to the decision aid structure and content were made. Subsequent usability testing (N = 11) resulted in 212 comments. Care providers mainly provided feedback on medical content, and patients commented most on usability and summary layout. All participants reported that the decision aid was comprehensible and well-structured and would recommend decision aid use. After usability testing, final adjustments to the decision aid were made. The presented methods could be useful for cultural adaptation of pre-existing tools into other languages and settings, ensuring optimal usage of previous scientific and practical efforts and allowing for a global, incremental decision aid development process.

Keywords: clinical decision-making, decision aids, information disclosure, prostate cancer, shared decision-making

Background

Decision aids (DAs) are tools designed to support the process of shared decision-making (SDM) between patients and their clinician.1,2 DAs can have multiple formats (e.g. leaflets, website), but should at least create choice awareness, offer balanced information and stimulate patients to consider their preferences.3 In general, DAs are associated with increased knowledge, more accurate risk perceptions and more conservative treatment preferences.4 The International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) provide DA developers consensus-based criteria to ensure DA quality.5 To help DA developers, a checklist is available that includes nine categories to which the DA should comply (e.g. Provide sufficient information about the decision and using high-quality evidence).6

A particularly fruitful area for the application of DAs is prostate cancer (Pca) care. Pca is the most common cancer in men in the Western world.7 Pca treatment guidelines do not indicate a single superior treatment option but recommend a shared treatment decision between clinician and patient.8 However, selecting the best suiting treatment from the available alternatives can be a burden for many patients. The process involves careful consideration of the risks and benefits of multiple treatments and weighing this against preferences and personal characteristics. Decision-making is further complicated by sub-optimal information provision and a possible misinterpretation of patient preferences by clinicians, which emphasizes the potential benefits from DAs in Pca care.9–11

Recent reviews of Pca DA trials concluded that current Pca DAs provide good quality information and help to increase patients’ knowledge.12,13 Despite improved information provision, current DAs do not guarantee that SDM takes place. Moreover, content, format and presentation of Pca information within DAs varied substantially, with many failing to comply to all components of the IPDAS criteria.12,13 The most identified shortcomings consisted of not including physicians and patients during DA development, a lack of balanced information on all options and the absence of explanation about the evidence used in the DA.13 Rather than resolving these issues with current tools, often new tools are developed elsewhere. This further increases the variety and number of available tools, though routine use in clinical practice of these tools remains limited.14

As many care providers articulated the need for a suitable Dutch DA, we built an interactive website based on an existing evidence-based online Canadian DA, developed by Feldman-Stewart and colleagues15–19 as a starting point for further development in the Dutch situation. This article describes the development process of the DA and usability evaluation in Dutch clinical setting.

Methods

The DA development process and usability testing among relevant user groups consisted of six stages and was based on the model described by Kushniruk.20 This model describes the typical system development starting from initial analysis, prototype development and evaluation, but allows for more input and changes in every development step compared to more traditional methodologies that have a fixed order of steps. Each stage was worked on by a multidisciplinary development team of urologists, psychologists and engineers (N = 6). This section will discuss the stages in the development process, and the final DA as outcome is described in the “Results” section.

Stage 1: translating the pre-existing DA

The background and validation of the existing Canadian DA has been described thoroughly, with particular focus on the information needs of Pca patients when making a treatment decision.15–19 The validity of all topics covered by the original DA for Dutch patients was also confirmed by an earlier cross-country comparison (including The Netherlands) of information needs in Pca patients.21 Therefore, all content from the original DA was translated from English to Dutch.

Stage 2: evaluating Dutch clinical routine

To investigate typical conversation flow in consultations about Pca treatment decision-making, all non-clinicians within the development team observed consultations between patients and urologist in the outpatient clinic of the initiating hospital. In addition to these observations of actual consultations, role playing was used to emphasize the steps clinicians usually take in treatment decision-making consultations with a patient. Role playing was performed by the two clinicians involved in the development team, with one of them simulating the patient role. Other members from the development team observed with special focus on the structure of the simulated consultations.

Stage 3: DA re-design

Following the observations from stage 2, the original DA was re-designed to fit with typical conversation flow as observed in stage 2. Moreover, the translated textual content from stage 1 was further adjusted to comply with Dutch and European treatment guidelines. All content was re-written according to standards for creating web-based text to ensure readability and comprehensibility for all literacy groups (e.g. maximum of 10–15 words per sentence and 5–10 sentences per paragraph, clear headings and active phrasing).22,23 Readability and comprehensibility was later assessed by an expert in medical communication from the initiating hospital, who was not involved in the further development of the DA.

Stage 4: development of explicit value clarification exercises

For use in patient DAs, IPDAS defines that value clarification exercises (VCEs) should “help patients to clarify and communicate the personal value of options,” in order to ultimately increase congruence between personal preferences and the selected treatment option.24 However, without clear design guidelines for VCEs, a variety of exercises have been developed with little knowledge about which features actually work best.25–28 A recent review suggests that VCEs should at least include trade-offs between option attributes in order to encourage value congruent decision-making.29 Therefore, from all topics covered in the DA, those topics that differentiate between treatments were selected to create explicit VCEs. To present these topics as a trade-off, statements were presented in such way that an answer to each statement was related to a (type of) treatment. VCEs were developed within the development team and reviewed from the perspective of the disciplines present in the development team (urology, psychology, engineering design). After consensus by the development team, VCEs were added to the DA. The content and phrasing of the VCEs were further evaluated during usability testing.

Stage 5: usability testing

After completion of the first version of the adjusted DA, a usability test was conducted among patients and care providers (N = 11).

Setting and participants

Participants for usability testing were recruited in the initiating hospital in the southern region of The Netherlands, by the clinicians from the development team. Four urologists (not involved in the DA development), two oncology nurses, one radiation oncologist and four Pca patients with recent experience in Pca treatment decision-making agreed to participate in usability testing. All patients were between 55 and 65 years of age and within 6 months of Pca diagnosis. Patients with experience in the decision situation were selected because they were expected to be better able to imagine the situation of just having received a Pca diagnosis.30 IPDAS therefore also requires that DA testing is performed by experienced patients.6 Care providers were included in this usability test to ensure the DA content and usability would match their usual routines and their experiences with patients facing Pca treatment decisions. Also, care providers’ review during development is required by IPDAS.6 All care providers included in usability testing were affiliated to the initiating hospital, but not involved in any other stage of DA development. Care providers ages ranged from 35 to 60 years and all had a minimum of 5 years of experience in their current position. All participants were instructed to use the DA from the perspective of a patient diagnosed with low-risk Pca and eligible for all four treatments covered in the DA (active surveillance, surgery, brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy). No specific further usage instructions were given in order to let participants use the DA as naturalistically as possible.

Participants were asked to think aloud when navigating through the DA and to mention every remark or difficulty they encountered during DA usage. This procedure is commonly used to investigate human–computer interactions and has been applied before for DA usability testing as well.31 The usability test was run in two simultaneous sessions in the outpatient clinic of the initiating hospital, with two observers from the development team present in each session. The observers monitored whether the participants’ verbalization matched their DA usage (e.g. saying navigation was easily accompanied by clicking on the correct buttons). As the DA only consists of a limited number of steps, if any action was not verbalized by the participant, a clarifying question was asked to the participant. During DA usage, participants did not receive further feedback or other instructions from the observers. Each participant was given 30 min to use the DA followed by a 15-min semi-structured interview. The goal of the interview was to reflect on DA usage in addition to the comments made while using the DA. Interviews are commonly added to think-aloud procedures to ensure that the most important aspects have been covered during the usability test and to reduce the risk of bias in the interpretation of participants’ verbalizations.32 The interview covered five questions asked to all participants: (1) “What were your expectations upfront?” (2) “What is your first impression of the DA?” (3) “Was the information understandable and useful?” (4) “What were positive aspects?” and (5) “What can be improved?” Only patients were then asked the following: (1) “Would you recommend this to other patients?” and (2) “What feeling does the DA gave you?” Care providers were asked whether they would offer this DA to patients. Participants were then thanked for their participation and received a bottle of wine as token of appreciation for participating.

Measures and analysis

As a first step, all notes from all sessions and observers were combined and labeled as either general comments about the DA or related to a specific section of the DA. All comments were then further categorized to Usability, Layout, Language, Content, Amount, Values Clarification or DA Summary. Next, the accuracy and urgency of all comments were discussed by the development team to determine the implications for DA adjustments. If consensus was reached on the need for changes, this led to final adjustments in the DA.

Stage 6: final adjustments

Usability testing resulted in final adjustments to the DA (described in “Results” section). Finally, the DA was evaluated for compliance with the IPDAS criteria.6

Results

DA

Stage 1 resulted in a plain text translation of the original Canadian DA on a prototype website. From the observations of conversation flow in clinical practice (stage 2), it was learned that following diagnosis clinicians often do not go into detail about all treatment options immediately. If eligible for active surveillance, treatment options are first presented as a consideration between active surveillance and curative treatment, before curative treatment options are discussed in more detail. In order to tailor the DA to this typical conversation flow during consultation, the DA was designed into four steps. Table 1 provides an overview of all topics covered in DA steps 1–3.

Table 1.

Content covered in Dutch DA.

| Step 1: Introduction |

| What is prostate cancer? |

| What do PSA and Gleason mean? |

| How does prostate cancer progresses? |

| What is the effect on my life expectancy? |

| Step 2: Curative treatment versus active surveillance |

| What is active surveillance? |

| What treatments are there? |

| What are the advantages? |

| What are the disadvantages? |

| What are the risks? |

| What is the chance of a rising PSA? |

| What is the risk of dying from prostate cancer? |

| Step 3: Surgery versus radiotherapy |

| What is the procedure for surgery? |

| What is the procedure for radiation therapy? |

| What are the advantages? |

| What are the disadvantages? |

| What is the risk for erectile dysfunction? |

| What is the risk for bladder dysfunction? |

| What is the risk for bowel problems? |

| How do I know if treatment was successful? |

| What if the cancer progresses or treatment is not successful? |

PSA: prostate-specific antigen; DA: decision aid.

DA step 1: general Pca information

This introducing step provides background information about Pca in general. The anatomy of the prostate and the commonly used terms prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and Gleason are explained.

DA step 2: active surveillance versus curative treatment

The pros and cons of not treating immediately are compared to (immediate) curative treatment (Table 1). Specific treatment characteristics are not yet discussed in detail. Step 2 ends with VCEs on topics that require trade-offs between curative treatment and AS (Table 2).

Table 2.

DA value clarification exercises (VCEs).

| Step 2: Curative treatment versus active surveillance | ||

|---|---|---|

| Topic | Reasons for active surveillance | Reasons for treatment |

| Acceptance of deferring treatment | I am confident enough that I will be treated on time | I do not want to postpone treatment because I do not want to be too late |

| Avoiding possible unnecessary treatment | If treatment might be unnecessary, I would rather wait | I prefer treatment even if it might be unnecessary |

| Acceptance of treatment side-effects | I find possible treatment side effects like erectile and urinary dysfunctions difficult to accept | I find the possible treatment side effects acceptable |

| Step 3: Surgery versus radiotherapy | ||

| Topic | Reasons for surgery | Reasons for radiotherapy |

| Treatment procedure | I find it important that all cancer cells are removed from my body | I find it important that the cancer cells die and not grow further |

| Treatment side-effects | I find bowel problems worse than incontinence | I find incontinence worse than bowel problems |

| Secondary treatment | I am comforted by the thought that I can have radiation if surgery is unsuccessful | I accept that surgery is difficult after radiation |

| Fear for surgery | I am not anxious about surgery | I am anxious about surgery |

DA: decision aid.

DA step 3: surgery versus radiotherapy

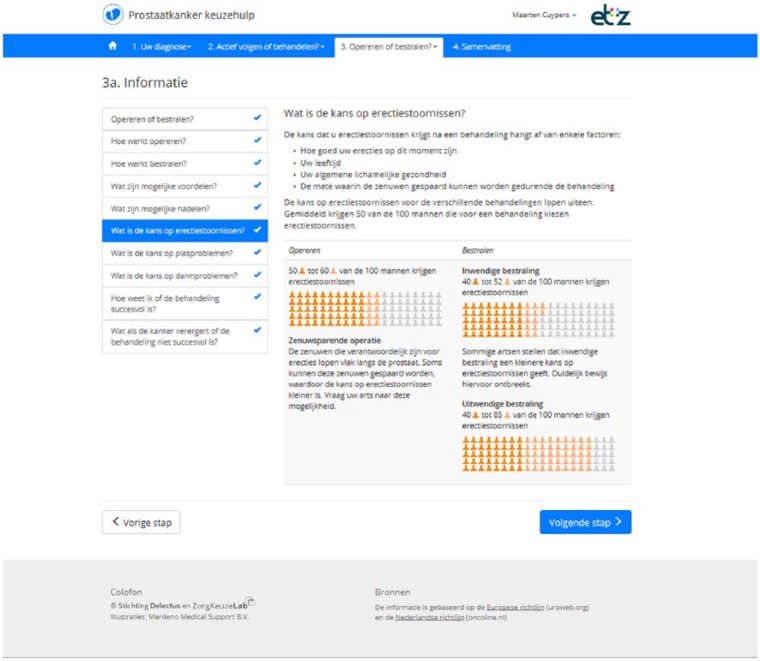

If patients are still undecided or have a preference for curative treatment following step 2, they continue to step 3. This step explains the difference between surgery and radiotherapy in more detail (Table 1). An example page from this step is provided in Figure 1. Patients who already prefer AS after step 2 are allowed to skip this step. Step 3 ends with VCEs on topics that differentiate between surgery and radiotherapy (Table 2). If patients already indicated a preference for AS in step 2, continuing with step 3 is optional.

Figure 1.

Screen from DA step 3: information about active treatments.

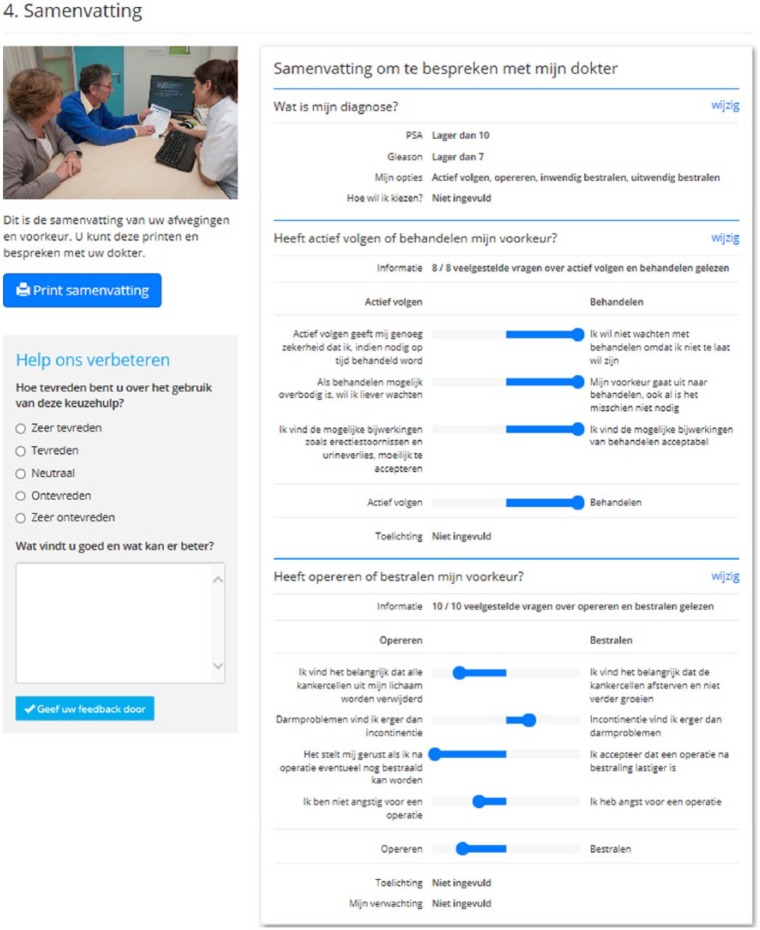

DA step 4: summary

An overview of how many topics have been read and the responses to VCEs are provided in a printable summary at the end of the DA (Figure 2). This summary can be taken by the patient to the next consultation with the clinician in order to further facilitate SDM. Alternatively, the summary can be accessed online during consultation.

Figure 2.

DA summary page.

Usability testing

Usability testing resulted in 212 usability and content comments. Care providers mainly reported feedback on the specific radiotherapy-related content, a need for more descriptive notes to accompany the illustrations and risk representations. Patients mainly reported usability remarks and comments about the DA summary section. All participants reported that the writing style was comprehensible and that the DA structure and navigation were clear. A summary of the results from the think-aloud procedure and interview results are presented in Table 3. In addition to the usability items, all care providers (100%) indicated that they would offer the DA to patients, and all patients (100%) indicated that they would recommend the DA to other patients. After discussion of the results in the development team, three main adjustments to the final DA were made: (1) accompanying legends were added, (2) radiotherapy content was adjusted and (3) the DA summary section was simplified. The final version of the DA complied to all IPDAS criteria6 (Table 4).

Table 3.

DA usability test summary.

| Category | Number of comments | Key findings | Representative quotes | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usability | 41 | Usage of the DA was intuitive and easy | Hardly needed any instructions Navigated smoothly, without extra instructions User-friendly |

No need for changes to improve usability |

| Layout | 26 | The layout was clear and supportive of making comparisons and trade-offs | Layout is clear Structured The differences are presented next to each other that helps in the trade-off |

No need to change the DA layout |

| Language | 17 | Used language is suitable for target group | Clear language Comprehensive language |

No need to change the writing style |

| Content | 35 | Content is complete and balanced | All pros and cons per option are named clearly Good explanations |

The general content was approved, but some aspects need adjustments |

| 12 | Some risk information is difficult to understand | Are these numbers correct? What does this figure mean? What does the difference in color mean in the figures? |

Descriptive notes and legends should be added to illustrations and risk figures | |

| 30 | Some details of the radiotherapy procedure needs adjustment or further elaboration | Brachytherapy also involves a surgical aspect External beam radiotherapy affects the entire prostate, not solely the tumor |

Radiation therapy content should be refined | |

| Amount | 16 | Presented information is complete but can be redundant if all sections are read | Very complete Still very information dense Repetition in some texts |

Patients should be allowed to skip parts that are not relevant to them, the message indicating this should be more prominent. The amount of information is needed to enable an informed decision. |

| Values clarification | 15 | Exercises are understood and used correctly | Statements help to weigh options | |

| Summary | 20 | The summary is not clearly recognized as a summary and natural ending of the DA | Is this the end of the DA? What does it mean that I have read 4 out of 4 themes? Some representation of personal situation would be nice |

Summary was not recognized as being the end of the DA. Headings should more clearly indicate that a summary is presented. The clinical information entered at DA start (PSA, Gleason, eligible treatments) should also be displayed in the summary |

| Total | 212 |

DA: decision aid; PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

Table 4.

IPDASi v3 checklist.

| Dimension | Item | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Information | 1. The decision support technology (DST) describes the health condition or problem (intervention, procedure or investigation) for which the index decision is required | ✓ |

| 2. The DST describes the decision that needs to be considered (the index decision) | ✓ | |

| 3. The DST describes the options available for the index decision | ✓ | |

| 4. The DST describes the natural course of the health condition or problem, if no action is taken. | ✓ | |

| 5. The DST describes the positive features (benefits or advantages) of each option | ✓ | |

| 6. The decision aid describes negative features (harms, side effects or disadvantages) of each option. | ✓ | |

| 7. The DST makes it possible to compare the positive and negative features of the available options. | ✓ | |

| 8. The DST shows the negative and positive features of options with equal detail (for example, using similar fonts, order and display of statistical information). | ✓ | |

| Probabilities | 1. The DST provides information about outcome probabilities associated with the options (i.e. the likely consequences of decisions) | ✓ |

| 2. The DST specifies the defined group (reference class) of patients for which the outcome probabilities apply. | ✓ | |

| 3. The DST specifies the event rates for the outcome probabilities (in natural frequencies). | ✓ | |

| 4. The DST specifies the time period over which the outcome probabilities apply. | ✓ | |

| 5. The DST allows the user to compare outcome probabilities across options using the same denominator and time period. | ✓ | |

| 6. The DST provides information about the levels of uncertainty around event or outcome probabilities (e.g. by giving a range or by using phrases such as “our best estimate is …”). | ✓ | |

| 7. The DST provides more than one way of viewing the probabilities (e.g. words, numbers and diagrams). | ✓ | |

| 8. The DST provides balanced information about event or outcome probabilities to limit framing biases. | ✓ | |

| Values | 1. The DST describes the features of options to help patients imagine what it is like to experience the physical effects. | ✓ |

| 2. The DST describes the features of options to help patients imagine what it is like to experience the psychological effects. | ✓ | |

| 3. The decision support technology describes the features of options to help patients imagine what it is like to experience the social effects. | ✓ | |

| 4. The decision support technology asks patients to think about which positive and negative features of the options matter most to them. | ✓ | |

| Decision Guidance | 1. The decision support technology provides a step-by-step way to make a decision. | ✓ |

| 2. The decision support technology includes tools like worksheets or lists of questions to use when discussing options with a practitioner. | ✓ | |

| Development | 1. The development process included finding out what clients or patients need to prepare them to discuss a specific decision. | ✓ |

| 2. The development process included finding out what health professionals need to prepare them to discuss a specific decision with patients. | ✓ | |

| 3. The development process included expert review by clients/patients not involved in producing the decision support technology. | ✓ | |

| 4. The development process included expert review by health professionals not involved in producing the decision aid. | ✓ | |

| 5. The decision support technology was field tested with patients who were facing the decision. | ✓ | |

| 6. The decision support technology was field tested with practitioners who counsel patients who face the decision. | ✓ | |

| Evidence | 1. The decision support technology (or associated documentation) provides citations to the studies selected. | ✓ |

| 2. The decision support technology (or associated documentation) describes how research evidence was selected or synthesized. | ✓ | |

| 3. The decision support technology (or associated documentation) provides a production or publication date. | ✓ | |

| 4. The decision support technology (or associated documentation) provides information about the proposed update policy. | ✓ | |

| 5. The decision support technology (or associated documentation) describes the quality of the research evidence used. | ✓ | |

| Disclosure and Transparency | 1. The decision support technology (or associated technical documentation) provides information about the funding used for development. | ✓ |

| 2. The decision support technology includes author/developer credentials or qualifications. | ✓ | |

| Plain Language | 1. The decision support technology (or associated documentation) reports readability levels (using one or more of the available scales). | ✓ |

| DST Evaluation | 1. There is evidence that the DST improves the match between the features that matter most to the informed patient and the option that is chosen. | ✓ |

| 2. There is evidence that the patient decision support technology helps patients improve their knowledge about options’ features. | ✓ |

DST: decision support technology.

Discussion

This article describes the development of a Dutch Pca treatment DA, based on an evidence-based Canadian Pca treatment DA and the subsequent usability testing among relevant user groups. Results of usability testing show that the DA was evaluated positively by patients and care providers and both groups would recommend use of the DA in clinical practice. The described development method could be useful for adaptation of other pre-existing and validated tools to different cultural or local circumstances.

Development of DAs is an effortful process and usually involves multiple rounds of assessing needs, required content and preferred structure among patients and care providers.33 An important benefit of the proposed model of adapting a pre-existing tool is that these steps are already taken. For the current DA, the content was previously validated,15–19 and a cross-cultural comparison also confirmed importance of the included topics to Dutch patients.21

The availability of validated content made it possible to focus more on the fit between DA structure and typical conversation flow in routine clinical practice. Many DAs have been developed for use independent from the consultation,34 which may have led to a suboptimal fit between conversation flow during consultation and DA structure. A known barrier related to limited DA uptake in clinical practice is that clinicians often find DAs impractical to use or that other consultation-specific factors limit structural DA implementation.35 Therefore, additional observations of clinical consultations and role playing took place and identified a two-step approach in discussing Pca treatment alternatives with patients. Instead of offering four alternative treatments simultaneously, a first step contains choosing between active surveillance and curative treatment and a second step discusses curative treatments in more detail. By also transferring this two-step approach from consultation into the DA, it is expected that patients experience a more natural fit between consultation and DA usage. Moreover, the DA provides direct support to the clinician’s explanation.

To further improve facilitation of SDM, we added two features to the DA. First, VCEs were developed and added to the DA. Second, the DA ends with a printable summary of preferences and responses to the VCEs that the patient can bring to his clinician for discussion. The summary provides the clinician with insight on what matters most to the patient and to what extent the patient has formed a preference or is still undecided. The following consultation and additional decisional support (e.g. consultations with nurses, radiotherapists) can then be adjusted accordingly. A cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) is in progress to evaluate the efficacy of this DA and to test whether decision outcomes align with patients’ preferences and values.36

Literature reports mixed findings from using VCEs in DAs and provide no clear guidelines for VCE design.25,26,28,37,38 However, there are indications to assume that the benefit of VCEs emerge after the decision is made and that VCE design should at least incorporate trade-offs between treatment attributes.19,29 In the absence of design guidelines, further development of the VCE within the current DA was based on consensus within the development team. However, future research should look into the effectiveness of the VCE features used in this DA.

A specific aspect that needs to be investigated further is the labeling of VCE outcomes. For the current DA, the development team decided to label VCE outcomes with corresponding treatments. With a strong initial treatment preference (pre-DA), it could be that labeling may lead to patients seeking confirmation of their initial preference rather than achieving actual preference elicitation or misinterpreting information.39 However, for clarity reasons, we believed that the VCEs should have labeled outcomes to make patients aware of the consequence of their preference (e.g. when valuing incontinence worse than bowel problems, a patient should place radiation therapy over surgery on this topic). With this insight, the responses to the VCE contribute to the construction of an informed treatment preference. We expect that labeled VCEs support this process better compared to unlabeled items. To gain more understanding on the development and usage of VCEs, more studies are needed to investigate VCE effectiveness and optimal presentation formats.

A potential limitation of the current development and usability test was the relatively small sample used in usability testing (N = 11). However, our sample included all relevant user groups: patients, urologists, nurses and a radiotherapist. All participants in usability testing consented on the usability and acceptability of the DA to a point where it seemed saturation was reached, and it was not expected additional participants would have resulted in new insights. The point of saturation in qualitative research is often reached within 6–12 participants.40

Conclusion

The newly developed Dutch Pca treatment DA was evaluated positively by patients and care providers, both groups would recommend DA usage to others. Patients consented on easy usability and care providers confirmed the accuracy of the provided information. Adapting an existing tool to a (culturally) different setting and adjusting it to local circumstances seems a useful alternative to an entirely new development process. This could free resources to focus on other important aspects like DA implementation.

Practice implications

The process of developing and testing the DA as described in this article could be applied to the (cultural) adaptation of other pre-existing tools to different languages and clinical settings. As it enhances focus on usability and fit with clinical practice, it could be a fruitful step to improve implementation of DAs in routine clinical care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Feldman-Stewart and her team at Queen’s Cancer Research Institute in Ontario, Canada, for sharing their original decision aid for further development in The Netherlands. The development of the DA in The Netherlands was funded by the Delectus Foundation. The authors thank all patients and care providers for participating in the usability test. Finally, the authors thank the Communications Department of the Elisabeth-TweeSteden Hospital for revising all textual content of the decision aid.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Maarten Cuypers, Tilburg University, The Netherlands.

Lonneke V van de Poll-Franse, Tilburg University, The Netherlands; Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation, The Netherlands.

Marieke de Vries, Radboud University, The Netherlands.

References

- 1. Stiggelbout AM, Van der Weijden T, De Wit M, et al. Shared decision making: really putting patients at the centre of healthcare. BMJ 2012; 344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hoffmann TC, Légaré F, Simmons MB, et al. Shared decision making: what do clinicians need to know and why should they bother? Med J Aust 2014; 201(1): 35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aid: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ 2006; 333(7565): 417–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 1(1): 1–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Joseph-Williams N, Newcombe R, Politi M, et al. Toward minimum standards for certifying patient decision aids: a modified Delphi consensus process. Med Decis Making 2014; 34(6): 699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Elwyn G, O’Connor AM, Bennett C, et al. Assessing the quality of decision support technologies using the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Instrument (IPDASi). PLoS ONE 2009; 4(3): e4705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015; 136(5): E359–E386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent—update 2013. Eur Urol 2014; 65(1): 124–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carlson LE, Waller A, Mitchell AJ. Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: review and recommendations. J Clin Oncol 2012; 39: 5509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sonn GA, Sadetsky N, Presti JC, et al. Differing perceptions of quality of life in patients with prostate cancer and their doctors. J Urol 2013; 189(1): S59–S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lamers RED, Cuypers M, Husson O, et al. Patients are dissatisfied with information provision: perceived information provision and quality of life in prostate cancer patients. Psychooncology 2016; 25: 633–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Violette PD, Agoritsas T, Alexander P, et al. Decision aids for localized prostate cancer treatment choice: systematic review and meta-analysis. CA 2015; 65(3): 239–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Adsul P, Wray R, Spradling K, et al. Systematic review of decision aids for newly diagnosed patients with prostate cancer making treatment decisions. J Urol 2015; 194(5): 1247–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elwyn G, Scholl I, Tietbohl C, et al. “Many miles to go …”: a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013; 13(Suppl. 2): S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feldman-Stewart D, Brundage MD, Nickel JC, et al. The information required by patients with early-stage prostate cancer in choosing their treatment. BJU Int 2001; 87(3): 218–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feldman-Stewart D, Brundage MD, Manen LV, et al. Patient-focussed decision-making in early-stage prostate cancer: insights from a cognitively based decision aid. Health Expect 2004; 7(2): 126–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feldman-Stewart D, Brennenstuhl S, Brundage MD, et al. An explicit values clarification task: development and validation. Patient Educ Couns 2006; 63(3): 350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Feldman-Stewart D, Brundage MD, Zotov V. Further insight into the perception of quantitative information: judgments of gist in treatment decisions. Med Decis Making 2007; 27(1): 34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feldman-Stewart D, Tong C, Siemens R, et al. The impact of explicit values clarification exercises in a patient decision aid emerges after the decision is actually made: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Med Decis Making 2012; 32(4): 616–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kushniruk A. Evaluation in the design of health information systems: application of approaches emerging from usability engineering. Comput Biol Med 2002; 32(3): 141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Feldman-Stewart D, Capirci C, Brennenstuhl S, et al. Information for decision making by patients with early-stage prostate cancer: a comparison across 9 countries. Med Decis Making 2011; 31(5): 754–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. DuBay WH. The principles of readability, 2004, http://www.impact-information.com/impactinfo/readability02.pdf

- 23. Writing for the web. Leiden University website editorial board, 2014, http://www.communicatie.leidenuniv.nl/website/webredactie-richtlijnen/webschrijven/5-tips.html

- 24. O’Connor A, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Dolan J, et al. Section D: clarifying and expressing values. Original IPDAS collaboration background document, 2005, http://ipdas.ohri.ca/IPDAS_Background.pdf

- 25. Witteman HO, Scherer LD, Gavaruzzi T, et al. Design features of explicit values clarification methods: a systematic review. Med Decis Making 2016; 36: 453–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fagerlin A, Pignone M, Abhyankar P, et al. Clarifying values: an updated review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013; 13(Suppl. 2): S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Crump RT. Decision support for patients: values clarification and preference elicitation. Med Care Res Rev 2013; 70(Suppl. 1): 50S–79S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Vries M, Fagerlin A, Witteman HO, et al. Combining deliberation and intuition in patient decision support. Patient Educ Couns 2013; 91(2): 154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Munro S, Stacey D, Lewis KB, et al. Choosing treatment and screening options congruent with values: do decision aids help? Sub-analysis of a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2016; 99: 491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Feldman-Stewart D, Brundage MD, Van Manen L. A decision aid for men with early stage prostate cancer: theoretical basis and a test by surrogate patients. Health Expect 2001; 4(4): 221–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Durand M-A, Wegwarth O, Boivin J, et al. Design and usability of heuristic-based deliberation tools for women facing amniocentesis. Health Expect 2012; 15(1): 32–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cotton D, Gresty K. Reflecting on the think-aloud method for evaluating e-learning. Brit J Educ Technol 2006; 37(1): 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Coulter A, Stilwell D, Kryworuchko J, et al. A systematic development process for patient decision aids. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013; 13(2): 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Volandes AE, et al. Investing in deliberation: a definition and classification of decision support interventions for people facing difficult health decisions. Med Decis Making 2010; 30(6): 701–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wyatt KD, Branda ME, Anderson RT, et al. Peering into the black box: a meta-analysis of how clinicians use decision aids during clinical encounters. Implement Sci 2014; 9(1): 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cuypers M, Lamers R, Kil P, et al. Impact of a web-based treatment decision aid for early-stage prostate cancer on shared decision-making and health outcomes: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2015; 16(1): 231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Garvelink MM, Ter Kuile MM, Stiggelbout AM, et al. Values clarification in a decision aid about fertility preservation: does it add to information provision? BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2014; 14(1): 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scherer LD, De Vries M, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, et al. Trust in deliberation: the consequences of deliberative decision strategies for medical decisions. Health Psychol 2015; 34(11): 1090–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dolan JG, Cherkasky OA, Chin N, et al. Decision aids: the effect of labeling options on patient choices and decision making. Med Decis Making 2015; 35(8): 979–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006; 18(1): 59–82. [Google Scholar]