Abstract

There is a gap in knowledge of women’s perceptions of e-health treatment. This review aims to investigate women’s expectations and experiences regarding e-health. A search was conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and PsycInfo in March 2016. We included articles published between 2000 and March 2016, reporting on e-health interventions. The initial search yielded 2987 articles. Eventually, 16 articles reporting on 16 studies were included. Barriers to e-health treatment were lower for women than barriers to face-to-face treatment, such as feelings of shame and time constraints. Women were able to develop an online therapeutic relationship. As reduced feelings of obligation and lack of motivation were women’s greatest challenges in completing e-health treatment, they expressed a wish for more support during e-health treatment, preferably blended care. e-Health lowers the threshold for women to seek healthcare. Combining e-health interventions with face-to-face sessions may enhance women’s motivation to complete treatment.

Keywords: e-Health, expectations, experiences, Internet-based treatment, women

Introduction

One of the main health challenges is to deliver the best achievable healthcare at the lowest possible cost1 and to keep healthcare accessible at the same time. In the current 24-h economy, there is a growing need for timely access to information and advice, and this trend continues into healthcare. Shortage of healthcare providers and long waiting times, meanwhile, are preventing patients from receiving the medical help they need.2 For these reasons, information and communication technologies are becoming an integral part of healthcare delivery.

Internet delivery of healthcare helps to overcome barriers in time, mobility and geography3 and provides timely access to information as well as the ability to communicate with both providers and peers.3,4 More and more healthcare interventions are delivered over the Internet and are referred to as “e-health interventions.” e-Health interventions have proven to be effective for a wide range of indications5–10 and are continually evolving.11 Components of e-health interventions are mainly delivered in the form of texts presented on web pages, with support provided via e-mail12 and interactive online features.12,13 Considerable interest has arisen in tailoring e-health interventions to specific individual needs, which appears to enhance user engagement and might make e-health interventions more effective.4,14

Our specific expertise as a center of women’s health has led us to focus particularly on e-health interventions for women. Women more actively seek for information about their health, which may be reflected in how they utilize information sources such as the Internet.15 Therefore, women might be an eligible target group for e-health interventions. Also, women more often have to cope with shameful conditions such as urogynecological diseases, which may raise the threshold for them to seek healthcare.16,17 Research suggests that e-health may reduce women’s feelings of shame while seeking healthcare.18–20 The Internet also allows women to multitask on a regular basis, balancing all the activities of work and home at all times.3,21 Previous findings suggest that e-health interventions may offer potential in delivering healthcare to women. However, there is a gap in knowledge of this topic. The objective of this review, therefore, is to investigate women’s expectations and experiences regarding e-health treatment.

Methods

We prospectively registered our systematic review in the Prospero international prospective register of systematic reviews, registration number CRD42016039297. Our review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines.22

Data sources

A search strategy was developed in MEDLINE and adapted to EMBASE, CINAHL and PsycInfo with the assistance of a skilled librarian (A.v.d.S.-S., C.V.). In order to maximize the sensitivity of the search, a combination of free-text and thesaurus terms was used (Appendix 1). The search was run in March 2016. It was extended by manually reviewing the retrieved papers’ reference lists, the previously listed databases, Google Scholar and the content pages of the online Journal of Medical Internet Research related to the theme “Web-based and Mobile Health Interventions,” published until 9 March 2016 (C.V.). We contacted 14 authors because no PDF version of their article was accessible and one author because information appeared to be missing in the article. Publication bias was not formally assessed.

Study selection

All found articles were independently screened on title and abstract by two authors for eligibility of full-paper evaluation (A.v.d.S.-S., C.V.). Table 1 shows our eligibility criteria. Full-paper evaluation was performed in duplicate using a standardized decision model based on our eligibility criteria (A.v.d.S.-S., C.V.). The decision model was developed by one of the authors (A.v.d.S.-S.) and offered three possibilities: definitely included, definitely excluded and possibly eligible for inclusion. In order to reach consensus, researchers discussed articles that were rated by at least one author as “possibly eligible for inclusion” as well as articles they did not agree upon. A third researcher was decisive in the case of persistent disagreement or doubt (D.T.). After consultation of this third reviewer, agreement was reached. An interrater reliability analysis using the Kappa statistic was performed to determine consistency among raters. Interrater reliability was found to be Kappa = 0.67 (p < 0.001), 95 percent confidence interval (CI: 0.55–0.79), which can be interpreted as “substantial agreement” according to Landis and Koch.23 Most disagreement arose over whether or not the study intervention met our definition of e-health interventions and on the applicability of the study outcomes to e-health in general. These were also the main reasons for exclusion of articles.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria.

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Populations | Adult female patients or adult patients and outcomes reducible to gender | No women or outcomes not reducible to gender |

| Interventions | e-Health interventions that are predominantly text-based, that is, online counseling via chat or e-mail, Internet-delivered self-help programs e-Health interventions with the aim to provide treatment |

Videoconferencing or audio-based treatments Online support groups, online diagnostic or monitoring tools |

| Outcomes | Expectations and/or experiences regarding e-health interventions | No expectations and/or experiences regarding e-health interventions |

| Study designs | Both qualitative and quantitative research | Case reports, systematic reviews, letters to the editor |

| Language | English or Dutch language | Non-English and non-Dutch languages |

| Study qualitya | “Moderate” or “strong” | “Weak” or “very weak” |

| Date of publishing | Between January 2000 and March 2016 | Before January 2000 or after March 2016 |

See “Methodological quality assessment.”

Methodological quality assessment

Two researchers independently performed a methodological quality assessment of the selected articles in an unblinded manner (C.V., A.v.d.S.-S.). For qualitative studies, we used a checklist including criteria adapted from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme.24 The following items were included: statement of research aims, appropriateness of qualitative research, research design, recruitment strategy, data collection, consideration of relationship between researcher and participants, ethical issues, data analysis, statement of findings and valuability. Maximum score was 20. Scores were classified as very weak (<12), weak (12–13), moderate (14–16) or strong (⩾17).

For quantitative studies, we used the version modified by Oram et al.,25 including the following items: research question, study design, sampling method, study sample, level of non-participation, assessment of exposure, assessment of outcomes, accounting for confounders, statistical analysis, reporting of confidence intervals, precision of results, ethical issues, conclusions, generalizability and fit with existing evidence. Maximum score was 30. Scores were categorized as very weak (<15), weak (15–19), moderate (20–24) or strong (⩾25).

Articles were excluded if study quality was rated as “weak” or “very weak.” In the case of disagreement between both researchers, the researchers met in order to reach consensus. A third reviewer was decisive when disagreement was persistent (D.T.). After consultation of this third reviewer, agreement was reached. An interrater reliability analysis using the Kappa statistic was performed to determine consistency among raters. Interrater reliability was found to be Kappa = 0.90 (p < 0.001), 95 percent CI (0.70–1.09), which can be interpreted as “almost perfect agreement” according to Landis and Koch.23

Synthesis methods

Data were extracted on population, exposure and outcomes using a standardized data extraction form, which provided the basis for Table 2 (C.V., A.v.d.S.-S.). Data were categorized, and categories were discussed by the research team (C.V., A.L.-J. and D.T.). Discussion was continued until agreement was reached on all themes.

Table 2.

Summary table of studies investigating expectations.

| Author, year of publication,a country | Method and sample size (% women) | Intervention, indication | Outcomes |

Mean CASP-scoreb (category) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive expectations | Negative expectations | ||||

| Beattie,33 2009, the United Kingdom | Interviews before and after treatment n = 24 (71) |

Online counseling, depression | Easier to be honest because of anonymity. Feeling more able to “express” themselves on the Internet | Impersonal relationship. Perceived inability to express themselves in written form, fear of not being understood by therapist. Concerns about therapeutic relationship in the absence of face-to-face contact. Intuitive preference for face-to-face therapy before treatment | 16/20 (moderate) |

| Cranen,45 2011, The Netherlands | Interviews n = 25 (52) |

(Hypothetical) web-based tailored exercise program, chronic pain patients in rehabilitation | Reduced travel time, flexibility of exercise times, no longer being in a hurry | Concerns about quality of feedback without therapist being physically present. Expecting the therapist to touch them. Impersonal approach. Reduced motivational stimulus. Training in groups seen as more motivating | 18.5/20 (strong) |

| Maloni,47 2013, the United States | Descriptive survey n = 53 (100) |

Hypothetical Internet intervention for postpartum depression (PPD) | Most reported barriers to face-to-face care: lack of time, stigma of PPD, not wanting to take medication, lack of childcare and cost. Ninety percent of women would use Internet to learn about ways to obtain help for PPD | – | 20/30 (moderate) |

| Köhle,46 2015, The Netherlands | Interviews n = 16 (38) |

Hypothetical web-based intervention, partners of cancer patients | Having a professional to check on them, ability to ask questions, ability to receive feedback, acknowledgement and support. There is a need for a form of peer support | Being already challenged with managing caregiver responsibilities and everyday tasks. Fear of losing valuable time with partner. Already experiencing enough support from usual healthcare | 18.5/20 (strong) |

CASP: Critical Appraisal Skills Programme.

Chronological order of year of publication.

Mean score of scores as awarded by both researchers.

Results

Search results

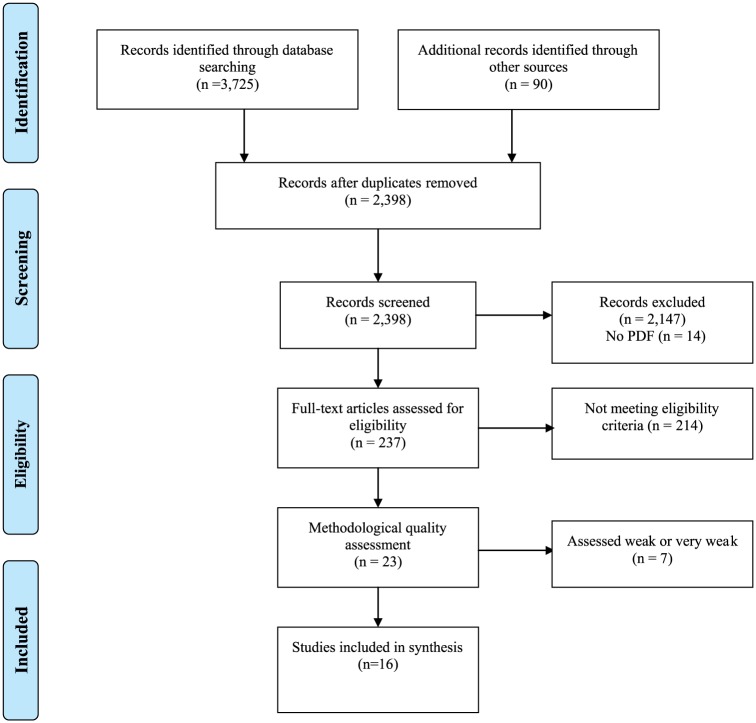

The initial search yielded 2398 articles (Figure 1). Based on title and abstract screening, 2161 articles were excluded, leaving 237 articles for full-paper evaluation. Of these, 23 articles met our eligibility criteria. Methodological quality assessment led to the exclusion of another seven articles.26–32 As a result, 16 articles were included, reporting on 1 quantitative study, 2 mixed-methods studies and 13 qualitative studies. The results of the methodological quality assessment and study characteristics of the included studies are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The results of the methodological quality assessment and study characteristics of the excluded studies are shown in Table 4.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.22

Table 3.

Summary table of studies investigating experiences.

| Author, year of publication,a country | Method and sample size (% women) | Intervention, indication | Outcomes |

Mean CASP scoreb (category) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive experiences | Negative experiences | ||||

| Beattie et al.,33 2009, the United Kingdom | Interviews before and after treatment n = 24 (71) |

Online counseling, depression | The ability to develop an online relationship, experienced transformation to “face-to-face” therapy over time | Communication experienced as “disrupting.” Response delay led to skeptical thoughts and doubting of therapist’s commitment | 16/20 (moderate) |

| Cook and Doyle,34 2002, the United States | Working Alliance Inventory + typed comments n = 15 (93) |

Online counseling in general trough e-mail or chat | To be able to express themselves online without embarrassment or judgment, perceived disinhibition. Easier to express thoughts and feelings trough writing. Affordability, convenience and flexibility, lack of travel time and parking | – | 16/20 (strong) |

| Bendelin et al.,35 2011, Sweden | Interviews n = 12 (50) |

Internet-based self-help with minimal therapist contact, depression | Appreciation of the ability to work on their own, improvement of self-esteem. Not having to talk to someone face-to-face. Feeling able to consult someone if needed | The wish for more contact in form of conversation to help them overcome barriers in treatment | 19.5/20 (strong) |

| Sanchez-Ortiz et al.,36 2011, the United Kingdom | Interviews n = 9 (100) |

Online cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) “Overcoming bulimia” + workbooks, bulimia nervosa | Accessibility, flexibility. Perceived privacy and anonymity. Feeling less judged, stigmatized. Experiencing the program as more real because of therapist support | Requirement of self-discipline and motivation. Concerns regarding accessing online program in public space. Need for more e-mail support and follow-up. Wish for other methods of support such as face-to-face contact or telephone calls to improve motivation and make treatment more personal | 17.5/20 (strong) |

| Poole et al.,37 2012, the United Kingdom | Interviews n = 20 (?) |

Internet-based self-help programme “Beating Bipolar” with initial face-to-face sessions, bipolar disorder | The ability to access the program in their own time, at their own place. Perceived anonymity. The option to revisit modules or take a break. Feeling able to engage with the computer | Lack of sociability compared to group-based learning. No ability to learn from others, lack of people you can openly talk to. Lack of activities on the forum. Resistance to using a computer | 18/20 (strong) |

| Lillevoll et al.,38 2013, Norway | Interviews n = 14 (64) |

Online CBT “MoodGYM” with brief consultations with therapist, depression | Involvement of therapist as vital part of treatment to enhance women’s understanding about program content. Feeling supported when able to recognize something in the program content. Reduced costs | Frustration when program does not meet specific needs. Importance of a dialogue to be able to ask questions, discuss issues and receive feedback | 17.5/20 (strong) |

| Rodda et al.,39 2013, Australia | Short survey with open-ended questions n = 222 (unknown) n = 311 (unknown) |

Online counseling trough chat + e-mail “Gambling Help Online,” problem gambling | Easier to talk about feelings because of anonymity, less judged. Lower barriers for consulting a counselor. Immediate availability, 24 hours a day. Perceived easiness of chatting online. Feeling of increased control over sessions. More relaxed | – | 17/20 (strong) |

| Wilhelmsen et al.,40 2013, Norway | Interviews n = 14 (64) |

Online CBT “MoodGYM” supported by short face-to-face sessions, depression | Ability to take control over own treatment and do it in your own pace. More relaxed. Face-to-face consultations as absolutely necessary to participate in online CBT: facilitating women’s ability to apply program to their personal situation, having expert feedback from someone they can trust | Feeling that thoughts fell into place while meeting others. Struggling to find time to finish the modules. Feeling that program does not apply to their situation as a reason not to complete the program. Need for more time and for a more in-depth dialogue about their problems | 16.5/20 (moderate) |

| Björk et al.,41 2014, Sweden | Interviews by telephone n = 21 (100) |

Internet-based self-help program with e-mail support from therapist, stress urinary incontinence | Feeling less embarrassed for seeking medical help. Feeling supported and acknowledged without being exposed Development of patient–provider relationship online |

Experience of a less close patient–provider relationship in absence of face-to-face contact, thereby lowering motivation. More difficult to explain themselves in written text. Wish for physical examination at start of treatment | 19/20 (strong) |

| Martorella et al.,42 2014, Canada | Mixed-methods n = 20 (50) |

Web-based self-management program “SOULAGE-TAVIE,” postoperative pain after cardiac surgery | The ability to use it at your convenience. Improved access to information, ability to go back anytime. More personal because of “virtual nurse” | – | 17/20 (strong) |

| Moin et al.,43 2015, the United States | Interviews n = 17 (100) |

Web-based program “Prevent,” women veterans with pre-diabetes | No need to leave the house, ability to do things in your own pace, not being tied to a schedule. Feeling accountable toward online group, monitoring own progress compared to others | Less interactive, less intimate. Being more open when sitting before people. Absence of body language. Need for computer literacy | 17.5/20 (strong) |

| Pugh et al.,44 2015, Canada | Online survey with open-ended questions n = 24 (100) |

Therapist-assisted online CBT “TAICBT,” postpartum depression | Convenience of working at home, around family obligations. Perceived privacy and anonymity, feeling less judged. Integral role of the therapist: providing support, being available outside of working hours, making program more personal | Lack of time and demanding childcare schedule. Lack of motivation due to flexibility of program. Missing face-to-face contact with a therapist | 19/20 (strong) |

CASP: Critical Appraisal Skills Programme.

Chronological order of year of publication.

Mean score of scores as awarded by both researchers.

Table 4.

Summary table of excluded studies.

| Author, year of publication,a country | Method and sample size (% women) | Intervention, indication | Mean CASP scoreb (category) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Murray et al.,28 2003, the United Kingdom | Questionnaire, qualitative and quantitative questions n = 81 (96.3) |

CD-ROM-based intervention, consisting of eight interactive modules, bulimia nervosa | 11/20 (very weak) |

| Finfgeld-Connett,27 2009, the United States | Questionnaires and qualitative analysis of messages sent by researcher and participants n = 67 (100) |

Web-based treatment with eight reference modules and 15 decision-making modules, rural women with alcohol problems | 19/30 (weak) |

| Daley et al.,32 2011, the United Kingdom | Questionnaire (anonymously and with reminder) n = 1693 (100) |

Internet-based treatment in general (amongst other delivery modes), postmenopausal women | 12/30 (very weak) |

| Andreasson et al.,30 2013, Sweden | Random, cross-sectional interview survey of Swedish general population n = 9005 (55.2) |

Treatment via Internet in general (among other delivery modes), alcohol problems | 8.5/20 (very weak) |

| Fergus et al.,26 2013, Canada | Online satisfaction questionnaire including open-ended questions and post-treatment phone semi-structured interview n = 32 (50) |

Web-based treatment “Couple links,” women with breast cancer and their male partners | 12/20 (weak) |

| Bouwsma et al.,31 2014, the Netherlands | Online questionnaire at baseline and during follow-up, information from web blogs n = 215 (100) |

e-Health intervention, web portal with communicative tools (among other interventions) women undergoing gynecological surgery | 12.5/20 (weak) |

| Mc Combie et al.,29 2014, New Zealand | Support willingness questionnaire (quantitative) n = 102 (48) |

Hypothetical computerized psychological intervention for IBD | 15/30 (weak) |

CASP: Critical Appraisal Skills Programme; IBD: Inflammatory Bowel Disease.

Chronological order of year of publication.

Mean CASP score of scores awarded by both researchers.

Outcomes

We divided the outcomes into two themes: expectations and experiences. The expectations and experiences were further subdivided into positive and negative expectations and experiences.

Expectations

Four studies investigated women’s expectations of e-health treatment.33,45–47 Outcomes regarding women’s expectations are shown in Table 2.

Positive expectations

Women with postpartum depression (PPD) reported lack of time, the stigma of PPD, not wanting to take medication, lack of childcare and costs involved as the most common barriers to face-to-face care. Of these women, 90 percent reported to be willing to use the Internet to obtain help for their PPD.47 Women in general expected that the anonymity provided by the Internet would make it easier for them to talk about their problems and to express themselves.33 Women in telerehabilitation for chronic pain considered their current group meetings as inhibiting and believed that they would be more capable of expressing their feelings in individual treatment.45 Most women were also attracted by the flexibility of the exercise times and reduced travel time of e-health compared to face-to-face therapy.45 Women who were partners of cancer patients were interested in e-health intervention because they were looking for acknowledgement, information, advice and support in addressing their specific needs.46 Women believed that an online counselor could check on them, improve their motivation to complete treatment and would enable them to ask questions.46

Negative expectations

Women mentioned some negative expectations of e-health as well. Women were afraid that the absence of face-to-face contact would make their treatment more impersonal.33,45 Some of them feared that this would impact negatively on their relationship with the therapist,33 their motivation33,45 and subsequently on their therapy results.45 These women stressed the importance of being able to talk to their therapist in person and talk about their feelings45 and were skeptical about communicating with their therapist in the absence of non-verbal cues.33 Women wished to be able to ask questions during their treatment46 and receive feedback from their therapist.45 In the study by Beattie et al.,33 women often expressed an intuitive preference for face-to-face therapy prior to therapy, with the exception of a small minority that reported previous negative experiences with face-to-face therapy.33

Women in telerehabilitation for chronic pain anticipated that working at home would be more distracting or considered training in groups as more motivating.45 Some women worried about the time investment required of an e-health intervention because they were already challenged balancing caregiver responsibilities and everyday tasks.46 Other women were concerned about their writing skills and were afraid that they would not be able to express themselves correctly, and, hence, would be misunderstood by the therapist.33 Women in telerehabilitation for chronic pain expected their therapist to be physically present during exercises because they doubted the quality of feedback without the therapist’s physical presence.45

Experiences

A total of 13 studies investigated women’s experiences with e-health treatment.33–44,48 Outcomes regarding women’s experiences are shown in Table 3.

Positive experiences

Several women experienced barriers related to help-seeking in face-to-face treatment, which they did not experience or to a lesser extent in e-health treatment. Some women believed that their problem was not severe enough to justify seeking traditional healthcare or were afraid of not being taken seriously by their healthcare provider. This was sometimes caused by previous experiences.41 Women felt less embarrassed seeking help during e-health treatment and were less afraid of being judged.34,36,39,41,44 They were attracted by the perceived anonymity, privacy and confidentiality of e-health.34,36,37,39,41,44,48 This anonymity made it easier for them to disclose themselves.34,39 Meeting face-to-face made them feel exposed and pressured by the need to answer straightaway.41,48 e-Health treatment, therefore, was perceived as less confronting than face-to-face therapy.39

The greatest perceived practical barriers to traditional healthcare were lack of time, the need for transport and financial costs,34,38,43,44,48 as well as time restrictions and lack of continuity of healthcare providers.38,48 Due to the flexibility of exercise times and availability outside of working hours, women found it easier to integrate e-health interventions in their everyday life.34,36,37,40,42–45,48 Most women preferred the immediate access provided by e-health interventions to the appointment-based nature of traditional healthcare.39 They felt comfortable and relaxed doing things at home and at their own pace.37,39,40,43 Some women were enthusiastic about the ability to go backwards and forwards anytime and to skip parts of the program that they considered unsuitable.36,37,40,42,48 By being able to decide when to use treatment, women gained a feeling of being in control.39,40,48 They liked the ability to do something to help themselves and, hence, felt empowered.35,40,48 Women felt supported when the program met their individual needs.38

All women stressed the importance of the therapist during their treatment. Some even experienced their relationship with the therapist as a vital part of their treatment.36,38 They valued being able to consult someone if needed.35,36,39 The therapist made the program more personal and provided empathy and sympathy.33,44 The therapist’s support also helped them overcome barriers in treatment and increased the women’s motivation.35,38,41,44 Finally, the therapist enhanced women’s understanding of the program and their ability to apply the program to their personal situation.38,40

Women commented on the strength of their relationship with the therapist, noting the care and respect their therapist demonstrated.34 Women undergoing online counseling for various indications filled in a working alliance inventory and rated their relationship with an online counselor higher than their relationship with a face-to-face counselor and significantly higher for the “goal” subscale.34 A patient–therapist relationship developed despite the lack of face-to-face contact.33,41 Some women were surprised because they felt it was like face-to-face contact.33

Negative experiences

Although women benefited from the perceived privacy and anonymity, some mentioned that the absence of face-to-face contact made the treatment more impersonal.36,37,43,45,48 They missed receiving empathic response during their treatment48 and stressed the importance of non-verbal communication.33,41,43,48 These women anticipated that they would be more open when sitting in a room face-to-face with their therapist and preferred to talk to a professional in person and share feelings.38,40,43 Others mentioned that e-health treatment was less interactive than face-to-face therapy.43 They stressed the importance of a conversation, in which they would be able to ask questions and discuss problems with the therapist35,38 and were in need of a more in-depth dialogue about their problems.

The delayed typing time during the online sessions could be interpreted as disrupting communication, causing women to doubt the therapist’s involvement by speculating whether he or she was undertaking parallel activities.33 Some women found it more difficult to explain complex situations and feelings in written text than face-to-face and were afraid that the therapist would not understand them correctly.33,41 As a result, some women experienced the online patient–provider relationship as less close than face-to-face therapy.33,41

The flexibility and lack of obligations of the e-health interventions required more self-discipline and motivation than face-to-face treatment. The absence of face-to-face contact also led to reduced feelings of obligation,48 as it was more tempting to skip exercises.41,45 Therefore, some women found it difficult to complete the exercises and to adhere to the treatment schedule.36,44,48 They struggled to find time to finish the homework modules.35,40,44,45 Furthermore, women felt frustrated if the program did not meet their own specific needs, which lowered their motivation.38,48

Women with urinary incontinence undergoing e-health treatment expressed a wish to have a physical examination at the start of their treatment. They were looking for reassurance that everything looked normal and for confirmation that they were using the right muscles during pelvic floor muscle treatment.41 Likewise, women undergoing telerehabilitation for chronic pain anticipated that they would prefer to receive feedback from a therapist that is physically present.45 Some women viewed e-health treatment as complementary or as follow-up treatment to traditional healthcare rather than as standalone treatment.45 Generally speaking, women expressed a wish for more substantial monitoring and support.36,48

Discussion

This review provides an overview of women’s expectations and experiences regarding e-health. To our knowledge, no systematic review has been performed investigating e-health from women’s perspective in particular. The most important finding is that e-health lowers the threshold for women to seek healthcare, according to both women’s expectations and experiences. This supports the findings of Mohr et al.,49 which indicate that telephone and Internet treatments may help men and women to overcome barriers that would otherwise have prevented them from receiving healthcare.

In line with women’s expectations, the anonymity of the Internet makes it easier for women to talk about their problems. In the study by Van der Vaart et al.,50 on the other hand, most men and women observe that discussing thoughts, feelings and difficulties should still be done face-to-face. Although, prior to therapy, women are skeptical about developing a therapeutic relationship with their healthcare provider in the absence of face-to-face contact, they are able to develop an online therapeutic relationship. In the end, some women even consider this online relationship as if it were face-to-face contact. This finding matches that of Preschl et al.,51 indicating that a strong working alliance can be established in an online setting comparable to that established in face-to-face settings. However, some women experience this online relationship as less close and personal than a relationship established in face-to-face settings.

Also in line with their own expectations is that women are attracted by the flexibility of e-health, which enables them to do things at their own time, place and pace. Women thus gain a sense of self-control, leading to feelings of empowerment, a process through which people gain greater control over decisions and actions affecting their health.52 Nonetheless, some women perceive this flexibility as a barrier to completing their treatment, due to reduced feelings of obligation and motivation. Women’s intrinsic motivation increases if the program meets their individual needs. This suggests the importance of tailoring interventions to individual needs, which appears to improve user engagement in both men and women according to findings by Schubart et al.4 The therapist plays an important role in overcoming barriers in treatment, as he or she makes the program more personal and enhances women’s motivation.

In addition to previous research, indicating better adherence to supported e-health interventions than to unsupported e-health interventions independent of gender,4,8,11,53 our results now show that women express a wish for more support during e-health treatment to help them overcome barriers in treatment. In agreement with findings of Waller and Gilbody54 and Schneider et al.,11 who investigated experiences of both men and women, some women view e-health treatment as complementary rather than as standalone treatment.

Two studies investigated an e-health intervention based on the principles of at-home physical exercise. In the study of Cranen et al., patients with chronic pain were asked about their expectations of home telerehabilitation. In the study of Björk et al., women with stress urinary incontinence received an e-mail-guided Internet-based treatment or a non-guided postal treatment. The results of these studies similarly show that women performing physical exercises at home in the absence of a therapist worry whether they perform the exercises correctly. In the study of Cranen et al., women expected the therapist to touch them during the exercises and were concerned about the quality of the feedback without the therapist being physically present. In the study of Björk et al., women expressed a wish for physical examination at start of their treatment, to reassure that everything looked normal, and for a confirmation that they were using the right muscles. Thus, women undergoing at-home physical exercise seem to be in need of guidance from a therapist that is physically present.

Although women may gain a feeling of self-control and empowerment during e-health treatment on one hand, their insecurities about their own performances in the absence of a personal confirmation may negatively enforce them on the other hand. This balance might be of great importance for a successful treatment. Face-to-face guidance from a therapist is needed to strengthen women’s power during e-health treatment, especially during at-home exercise.

Limitations

Our systematic review has some limitations. First of all, limitations that apply to systematic reviews in general, such as the risk of publication bias and the risk of incomplete retrieval of literature, also apply to our study. As we only included publications in the English or Dutch language, language bias could not be ruled out. A disadvantage of using one tool for quality assessment is the possibility of missing articles that would have been included if we had used another tool. Nevertheless, we believe that the tool we used is one of the most accurate ones. Because we aimed to learn more about women’s perceptions of e-health, we included all studies involving female patients. We also included studies involving predominantly male patients, because we believe that every opinion might be of value, as qualitative research aims to provide insights into individual’s thoughts and feelings rather than to measure the incidence of various views and opinions. We included one study involving 14 women and 1 man, in which outcomes were not reducible to gender, but decided to accept this detail because we expected its effects on our results to be minimal. As with any other overview, another limitation is that patient populations, interventions and outcomes differ between studies, which may affect comparison and interpretation of results.

As the results of this review predominantly relied on women’s self-reporting, they may be at risk of social desirability or reporting bias, which should be taken into account while interpreting the results. Because women that are more familiar with the Internet are more likely to engage in e-health interventions, there is a risk of selection bias in all included studies. This risk is further enhanced as some studies recruited their participants by online advertisements. Due to the limited number of studies for each condition, it was impossible to make subgroup analyses, and no conclusions can be drawn, therefore, regarding individual conditions. Finally, some of the statements may not be related to e-health treatment in particular but to undergoing treatment in general. We do believe, however, that we conducted a review based on the best available evidence as we used extensive search strategies and only included articles with sufficient methodological quality.

Conclusion

The findings of this study support the hypothesis that e-health lowers barriers to healthcare in women who might otherwise not seek help. The anonymity of the Internet also helps women to disclose their feelings. Findings show that an online therapeutic relationship can develop, although some women experience this online relationship as less close than a relationship established in a face-to-face setting. Reduced feelings of obligation and lack of motivation are women’s greatest challenges in completing e-health treatment. Therefore, women often express a wish for more substantial monitoring and some form of face-to-face contact. More research needs to be conducted to determine what women might benefit from e-health interventions.

Practice implications

The outcomes of this review provide insight into women’s expectations and experiences regarding e-health. This information may help healthcare providers and policymakers to develop e-health interventions that are tailored to women’s wishes. Generally speaking, e-health appears to be well accepted by women. Due to its perceived anonymity, e-health may be particularly attractive to women with disorders that are perceived to be embarrassing or stigmatizing, such as urogenital and intimate problems. Its flexibility may enable women with competing priorities, such as working women and women with caregiver responsibilities, to integrate e-health into their everyday lives. As e-health appears to be helping women to overcome barriers to treatment, a subset of women who would otherwise not receive healthcare may be reached. In order to increase women’s motivation to complete their treatment and thus improve their treatment’s chances of success, we recommend that e-health interventions are combined with face-to-face sessions, which is also referred to as “blended care.”

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mrs R. Deurenberg-Vos and Mrs E. Pieters, advisor information specialists at the Radboud University Medical Centre Nijmegen, the Netherlands, for their contribution in developing the search strategy and Mr R. Stuve for his language assistance.

Appendix 1

Medline search strategy

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R)

E?HEALTH.tw. (1020)

E?HEALTH.kf. (271)

E?CBT.tw. (12)

E?CBT.kf. (0)

tele?health.tw. (1996)

tele?health.kf. (320)

exp Telemedicine/(17909)

th.fs. (1564074)

(therap* or treat* or intervent* or support*).tw. (6328477)

(therap* or treat* or intervent* or support*).kf. (251551)

7 and (or/8-10) (7369)

or/1-6 (3329)

or/8-10 (7011864)

12 and 13 (1775)

((internet or web* or tele* or remot* or online or distance or comput*) adj3 (therap* or treat* or intervent* or support*)).tw. (21887)

((internet or web* or tele* or remot* or online or distance or comput*) adj3 (therap* or treat* or intervent* or support*)).kf. (378)

or/11,14-16 (28191)

exp Patient Satisfaction/(68794)

exp Patient Preference/(4157)

(patient adj3 (prefer* or satisf* or opinion* or motivat* or argument*)).tw. (37618)

(patient adj3 (prefer* or satisf* or opinion* or motivat* or argument*)).kf. (964)

reas*.tw. (362817)

reas*.kf. (978)

or/18-23 (448784)

17 and 24 (2369)

(wom?n or female).tw. (1327900)

(wom?n or female).kf. (28739)

Female/(7176111)

or/26-28 (7363177)

25 and 29 (1255)

(dutch or english).la. (21186236)

30 and 31 (1206)

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

Articles that are included in the systematic review are marked by an asterisk.

- 1. Van der Wall EE. E-Health: a novel way to redesigning healthcare. Neth Heart J 2016; 24: 439–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaltenthaler E, Sutcliffe P, Parry G, et al. The acceptability to patients of computerized cognitive behaviour therapy for depression: a systematic review. Psychol Med 2008; 38(11): 1521–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Griffiths F, Lindenmeyer A, Powell J, et al. Why are health care interventions delivered over the internet? A systematic review of the published literature. J Med Internet Res 2006; 8(2): e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schubart JR, Stuckey HL, Ganeshamoorthy A, et al. Chronic health conditions and internet behavioral interventions: a review of factors to enhance user engagement. Comput Inform Nurs 2011; 29(2): 81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sjostrom M, Umefjord G, Stenlund H, et al. Internet-based treatment of stress urinary incontinence: 1- and 2-year results of a randomized controlled trial with a focus on pelvic floor muscle training. BJU Int 2015; 116(6): 955–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carlbring P, Ekselius L, Andersson G. Treatment of panic disorder via the Internet: a randomized trial of CBT vs. applied relaxation. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2003; 34(2): 129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pugh NE, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Dirkse D. A randomised controlled trial of therapist-assisted, internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for women with maternal depression. PLoS ONE 2016; 11(3): e0149186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Richards D, Richardson T. Computer-based psychological treatments for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2012; 32(4): 329–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Van den Berg MH, Schoones JW, Vliet Vlieland TP. Internet-based physical activity interventions: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res 2007; 9(3): e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weinert C, Cudney S, Comstock B, et al. Computer intervention impact on psychosocial adaptation of rural women with chronic conditions. Nurs Res 2011; 60(2): 82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schneider J, Sarrami Foroushani P, Grime P, et al. Acceptability of online self-help to people with depression: users’ views of MoodGYM versus informational websites. J Med Internet Res 2014; 16(3): e90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Andersson G, Carlbring P, Berger T, et al. What makes Internet therapy work? Cogn Behav Ther 2009; 38(Suppl. 1): 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Andersson G, Ljotsson B, Weise C. Internet-delivered treatment to promote health. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2011; 24(2): 168–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johansson R, Sjöberg E, Sjögren M, et al. Tailored vs. standardized internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for depression and comorbid symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2012; 7(5): e36905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tong V, Raynor DK, Aslani P. Gender differences in health and medicine information seeking behavior—a review. J Malta Coll Pharm Pract 2014; 20: 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koch LH. Help-seeking behaviors of women with urinary incontinence: an integrative literature review. J Midwifery Womens Health 2006; 51(6): e39–e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buurman MBR, Lagro-Janssen ALM. Women’s perception of postpartum pelvic floor dysfunction and their help-seeking behaviour: a qualitative interview study. Scand J Caring Sci 2013; 27(2): 406–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lipman EL, Kenny M, Marziali E. Providing web-based mental health services to at-risk women. BMC Womens Health 2011; 11(1): 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dunn K. A qualitative investigation into the online counselling relationship: to meet or not to meet, that is the question. Counsell Psychother Res J 2012; 12(4): 316–326. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Choo EK, Ranney ML, Wetle TF, et al. Attitudes toward computer interventions for partner abuse and drug use among women in the emergency department. Addict Disord Their Treat 2015; 14(2): 95–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Steffan Dickerson S. Gender differences in stories of everyday internet use. Health Care Women Int 2003; 24(5): 434–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009; 6(7): e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33(1): 159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. CASPC. CASP checklists (URL used). Oxford: CASP, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oram S, Stöckl H, Busza J, et al. Prevalence and risk of violence and the physical, mental, and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking: systematic review. PLoS Med 2012; 9(5): e1001224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fergus KD, McLeod D, Carter W, et al. Development and pilot testing of an online intervention to support young couples’ coping and adjustment to breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Care 2014; 23(4): 481–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Finfgeld-Connett D. Web-based treatment for rural women with alcohol problems: preliminary findings. Comput Inform Nurs 2009; 27(6): 345–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murray K, Pombo-Carril MG, Bara-Carril N, et al. Factors determining uptake of a CD-ROM-based CBT self-help treatment for bulimia: patient characteristics and subjective appraisals of self-help treatment. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2003; 11(3): 243–260. [Google Scholar]

- 29. McCombie A, Gearry R, Mulder R. Preferences of inflammatory bowel disease patients for computerised versus face-to-face psychological interventions. J Crohns Colitis 2014; 8(6): 536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Andreasson S, Danielsson AK, Wallhed-Finn S. Preferences regarding treatment for alcohol problems. Alcohol Alcohol 2013; 48(6): 694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bouwsma EV, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Szlavik Z, et al. Process evaluation of a multidisciplinary care program for patients undergoing gynaecological surgery. J Occup Rehabil 2014; 24(3): 425–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Daley A, Stokes-Lampard H, Wilson S, et al. What women want? Exercise preferences of menopausal women. Maturitas 2011; 68(2): 174–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *33. Beattie A, Shaw A, Kaur S, et al. Primary-care patients’ expectations and experiences of online cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: a qualitative study. Health Expect 2009; 12(1): 45–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *34. Cook JE, Doyle C. Working alliance in online therapy as compared to face-to-face therapy: preliminary results. Cyberpsychol Behav 2002; 5(2): 95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *35. Bendelin N, Hesser H, Dahl J, et al. Experiences of guided Internet-based cognitive-behavioural treatment for depression: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 2011; 11: 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *36. Sanchez-Ortiz VC, House J, Munro C, et al. “A computer isn’t gonna judge you”: a qualitative study of users’ views of an internet-based cognitive behavioural guided self-care treatment package for bulimia nervosa and related disorders. Eat Weight Disord 2011; 16(2): e93–e101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *37. Poole R, Simpson SA, Smith DJ. Internet-based psychoeducation for bipolar disorder: a qualitative analysis of feasibility, acceptability and impact. BMC Psychiatry 2012; 12: 139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *38. Lillevoll KR, Wilhelmsen M, Kolstrup N, et al. Patients’ experiences of helpfulness in guided internet-based treatment for depression: qualitative study of integrated therapeutic dimensions. J Med Internet Res 2013; 15(6): e126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *39. Rodda S, Lubman DI, Dowling NA, et al. Web-based counseling for problem gambling: exploring motivations and recommendations. J Med Internet Res 2013; 15(5): e99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *40. Wilhelmsen M, Lillevoll K, Risor MB, et al. Motivation to persist with internet-based cognitive behavioural treatment using blended care: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 2013; 13: 296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *41. Björk A-B, Sjöström M, Johansson EE, et al. Women’s experiences of internet-based or postal treatment for stress urinary incontinence. Qual Health Res 2014; 24(4): 484–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *42. Martorella G, Gelinas C, Purden M. Acceptability of a web-based and tailored intervention for the self-management of pain after cardiac surgery: the perception of women and men. JMIR Res Protoc 2014; 3(4): e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *43. Moin T, Ertl K, Schneider J, et al. Women veterans’ experience with a web-based diabetes prevention program: a qualitative study to inform future practice. J Med Internet Res 2015; 17(5): e127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *44. Pugh NE, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Hampton AJ, et al. Client experiences of guided internet cognitive behavior therapy for postpartum depression: a qualitative study. Arch Womens Ment Health 2015; 18(2): 209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *45. Cranen K, Drossaert CH, Brinkman ES, et al. An exploration of chronic pain patients’ perceptions of home telerehabilitation services. Health Expect 2012; 15(4): 339–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *46. Köhle N. Needs and preferences of partners of cancer patients regarding a web-based psychological intervention: a qualitative study. JMIR Cancer 2015; 1(2): e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *47. Maloni JA, Przeworski A, Damato EG. Web recruitment and internet use and preferences reported by women with postpartum depression after pregnancy complications. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2013; 27(2): 90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *48. Knowles SE, Lovell K, Bower P, et al. Patient experience of computerised therapy for depression in primary care. BMJ Open 2015; 5(11): e008581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mohr DC, Siddique J, Ho J, et al. Interest in behavioral and psychological treatments delivered face-to-face, by telephone, and by internet. Ann Behav Med 2010; 40(1): 89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Van der Vaart R, Witting M, Riper H, et al. Blending online therapy into regular face-to-face therapy for depression: content, ratio and preconditions according to patients and therapists using a Delphi study. BMC Psychiatry 2014; 14: 355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Preschl B, Maercker A, Wagner B. The working alliance in a randomized controlled trial comparing online with face-to-face cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. BMC Psychiatry 2011; 11(1): 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nutbeam D. Health promotion glossary. Health Promot 1986; 1: 113–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gerhards SA, Abma TA, Arntz A, et al. Improving adherence and effectiveness of computerised cognitive behavioural therapy without support for depression: a qualitative study on patient experiences. J Affect Disord 2011; 129(1–3): 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Waller R, Gilbody S. Barriers to the uptake of computerized cognitive behavioural therapy: a systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative evidence. Psychol Med 2009; 39(5): 705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]