Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Some low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) struggle to implement smoke-free policies. We sought to review the academic and gray literature, and propose a research agenda to improve implementation of smoke-free policies and make them more effective in LMICs.

METHODS

We reviewed 10 databases for variations of (‘implementation’ /‘enforcement’ /‘compliance’) and (‘smoke-free’ /‘ban’ /‘restriction’) and (‘tobacco’ /‘smoking’). We also reviewed cited sources and the gray literature including non-governmental organization reports.

We included articles that described problems that arose, attempted solutions, lessons learned, and research questions posed regarding smoke-free policy implementation in LMICs. We excluded studies of high-income countries, institution-level implementation, voluntary smoke-free policies, smoke-free homes, and outdoor smoke-free policies.

RESULTS

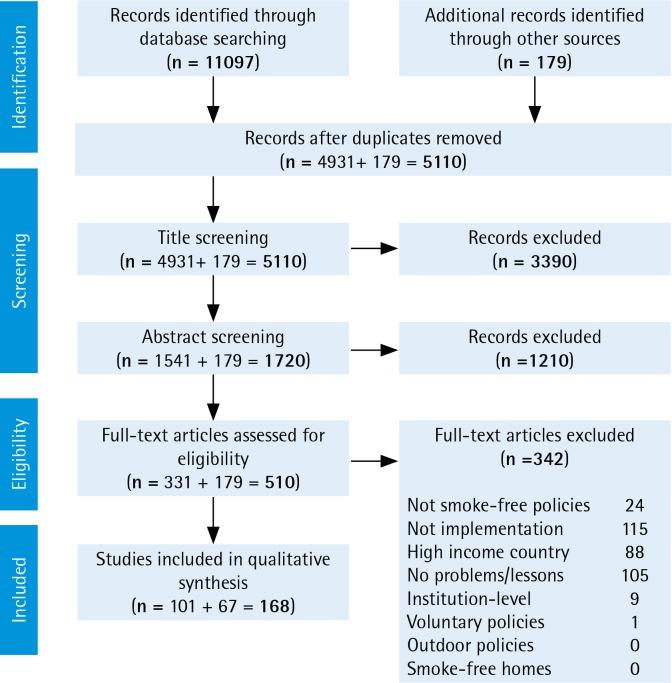

The academic literature review led to 4931 unique articles, reduced to 1541 after title screening, 331 after abstract screening, and 101 after full-text review. The citation and gray literature review led to an additional 179 publications of which 67 met the inclusion criteria. In total we retained 168 sources. We conducted a narrative review and synthesis of the literature, extracting key themes and noting research gaps.

CONCLUSIONS

We find that progress is urgently needed in five categories: identifying the critical lessons learned for effective implementation, evaluating different enforcement approaches, learning how to rejuvenate stalled smoke-free policies, learning how to increase ground-level will to enforce policies, and developing a conceptual framework that explains implementation. Investigation into these topics can improve implementation of smoke-free policies in LMICs.

Keywords: smoke-free policy, developing countries, review, tobacco smoke pollution, tobacco use

INTRODUCTION

Globally, secondhand smoke leads to 1.220 million deaths per year, of which 1.091 million are in low- and middle-income countries1. Among adults, secondhand smoke causes immediate cardiovascular effects, coronary heart disease, lung cancer, and potentially an array of other cancers2. In children, secondhand smoke causes sudden infant death syndrome, acute respiratory infections, and additional health problems2. The only way to fully protect non-smokers from the effects of smoke is to make spaces smoke-free2. Effective smoke-free policies banning tobacco smoking in public places and workplaces reduce exposure to smoke3,4, mitigate harmful health outcomes5,6, reduce smoking prevalence7,8, denormalize tobacco use9, and potentially discourage youth smoking initiation10,11. While smoke-free policies (laws, by-laws, ordinances, regulations etc.) are becoming more common, more than 80% of the world’s population is not yet protected by these policies12. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that all countries implement comprehensive smoke-free policies, defined as smoke-free policies with no exemptions for particular venue types or allowances for designated smoking areas2,13,14. There are now 181 countries that are parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), an international treaty of evidence-based public health measures responding to the tobacco epidemic15. The FCTC requires parties to implement smoke-free policies16 within 5 years of the FCTC taking force17, although accountability is limited18. Most of the first smoke-free policies were passed in high-income countries (HICs), where they have generally, but not always19, been popular with the public and achieved and maintained high compliance13. Starting with Uruguay in 2006, some low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are implementing comprehensive smoke-free policies. This is important, as the burden of the tobacco epidemic and resulting deaths have shifted to LMICs20, with 77% of all smoking-related deaths and 89% of secondhand smoke related-deaths occurring in LMICs1. As of 2016, 92 of the 138 LMICs have passed a smoke-free policy, but only 39 have comprehensive policies14. WHO has called for parties to the FCTC to conduct relevant research, share best practices, and assist LMICs with implementing effective tobacco control measures21. We sought to review the academic and gray literature and propose a research agenda to improve implementation of smoke-free policies and make them more effective in LMICs.

METHODS

We reviewed published academic and gray literature, and compiled lessons learned from experience working on smoke-free implementation in LMICs. We began with a comprehensive review using 10 health-related databases: PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Reviews, CINAHL, Global Health (OVID), PAIS International, PsycINFO, Scopus, Sociological Abstracts, and Web of Science, and searched for articles published through 18 January 2017. We searched for combinations and suffix variations of (‘implementation’ or ‘enforcement’ or ‘compliance’) and (‘smoke-free’ or ‘ban’ or ‘restriction’) and (‘tobacco’ or ‘smoking’). Full search strings are given in Supplementary File 1. To meet the inclusion criteria, articles needed to address at least one of the following: problems that have arisen, attempted solutions, lessons learned, or research questions posed regarding smoke-free policy implementation in LMICs. Articles were excluded if they only covered research in high-income countries, institution-level implementation, voluntary smoke-free policies, smoke-free homes, or outdoor smoke-free policies. We limited the search to the implementation of smoke-free policies at the city, regional, or national level. The search yielded 11097 total articles, of which 4931 were unique (Figure 1). The count reduced to 1541 after title screening, 331 after abstract screening, and 101 after full-text review. For 20 articles in which full text was not available in English, we reviewed the English abstracts. As a second major data source, we reviewed relevant citations from the found articles and extracted reports from WHO and tobacco control non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Of these additional 179 publications, 67 met the inclusion criteria used in the academic literature review, bringing the total number of search-based sources to 168. Most of the included articles were selected for meeting the criteria of discussing problems faced or lessons learned. Additionally, we incorporated relevant findings from our own work on smoke-free policies in South-East Asia22,23, Africa24,25, and globally26-30. We focus on post-legislation implementation — which we define as putting a smoke-free policy into practice and enforcing it to achieve the public’s compliance with the policy. After the articles were selected, we conducted a narrative review and synthesis of the literature31. First, we reviewed each source and catalogued key findings and indications of research needs. We then conducted a thematic content analysis in which we extracted recurrent themes from the data and noted research gaps32. Finally, the research team reviewed summary documents and discussed the data organization and presentation.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram of document review

RESULTS and DISCUSSION

The review revealed that many findings about smoke-free policies in HICs carry over to LMICs. As in HICs, successful smoke-free policies in LMICs reduce smoke exposure33-35 and resulting health harms34,36-39, increase quit intentions40,41, and potentially decrease youth smoking initiation42. Also as in HICs, policies that do not allow for designated smoking areas are easier to implement43-45 and more effective in reducing smoke exposure28,35,46,47. There is generally a high level of public support for smoke-free policies in LMICs34,48-60 and public support increases after implementation33,48,61-63. Research in LMICs also finds that there is no negative economic impact of smoke-free policies on the hospitality industry64,65. While these findings bode well for smoke-free policies that are successfully implemented, the actual implementation of smoke-free policies in LMICs has been mixed14,24,63,66.

The review found five priority gaps in knowledge. First, based on the experiences of cities, regions, and countries worldwide, there is now perhaps an unwieldy number of recommendations, guidelines, and lessons learned for implementing smoke-free policies13,27,37,64,67-86. Second, multiple approaches of enforcement have been used, but they have not been directly compared to see which is most effective13,17,67. Third, there was a common report of problems in enforcement, i.e. the ground-level implementers (inspectors, police, venue managers etc.) often do not enforce the policy14,63,66. Fourth, there are a number of countries where smoke-free policies exist on paper but not in practice, and they are in need of rejuvenation14,24,63,66. Fifth, the literature presented a notable gap in the conceptual framework with which to organize, troubleshoot, and advance smoke-free policies87-93. A table of the sources is provided in Supplementary File 2.

Here, we present the review findings and an agenda of the key areas where research can make a difference in advancing implementation of smoke-free policies. Each section begins with the current evidence, an estimation of weight of the evidence, and the research gaps for the topic. We then provide recommendations for the research needed. We present the five areas of findings and needed research in approximate order of potential impact.

Identifying the critical lessons learned for effective implementation

In addition to the many case studies documenting experiences of LMIC jurisdictions implementing smoke-free policies27,37,64,71-84, WHO and various NGOs have compiled lessons learned from numerous countries13,67-69,85,86. These guides suggest the following attributes may be most important to successful implementation of smoke-free policies in HICs and LMICs:

Strong political leadership;

Legislation that is simple, clear, enforceable, and comprehensive;

Thoughtful planning and adequate resources for implementation and enforcement;

Preparing for and countering tobacco industry opposition;

Involvement of civil society in planning and implementation;

Public education and outreach;

Education and consultation with stakeholders;

Additionally, these documents describe in detail many potentially important practices that complement the above identified attributes. A sampling of these additional practices include engaging in early interagency planning, securing adequate financial resources, assigning enforcement responsibility to the most effective agency, requiring removal of ashtrays from smoke-free areas, framing education messages around the health benefits of the policy for workers, focusing enforcement on venue managers rather than individual violators, and providing the public with a way to report violations17,67-69,85,94. The weight of the evidence in terms of there being a large body of recommendations is strong; the gap remains in refining these lists, since most LMICs have limited resources with which to implement smoke-free policies25,95.

The resulting area of research needed is in identifying those recommendations most critical for success. With this information, officials in LMICs can create an implementation plan compatible with their resources that covers the most essential recommendations. Interviews and open-ended surveys with government officials and tobacco control NGOs in LMIC jurisdictions where smoke-free policies are working well would be good approaches for learning these essential best practices. Researchers could also contribute to creating and testing basic low-cost instruments to assess the social environment and logistical resources before a smoke-free policy is passed. Such evaluations can examine public awareness of the proposed policy, the public’s compliance with similar policies (e.g. littering and other public conduct policies), experience and realistic capabilities of potential enforcement staff (e.g. police, health inspectors), and other key data points. With this needs-assessment, strategies can be organized to best address the known weak points and allocate financial and human resources accordingly for the particular country.

Evaluating different enforcement approaches

Jurisdictions across LMICs have tried different approaches to enforce smoke-free policies. For example, the early stages of enforcement may be especially important in setting the tone for the policy17,67. There are differing opinions as to the effectiveness of ‘soft enforcement’, an approach of phasing-in enforcement starting with reminders rather than fines13,17,67. On one hand, a ‘grace period’ is a way of educating people unaware of the policy and reasonably addressing violations due to ignorance13. On the other hand, strict enforcement, providing fines from day one, shows that a government is serious about the policy, and will enforce it67. A compromise approach is to use strict enforcement but allow businesses one formal warning before fines are issued67. Another set of questions is around the types of enforcement strategies to use — proactive versus reactive, random versus focused, and overt versus covert67. Finally, an important component to smoke-free policy enforcement is determining the allocation of enforcement resources and the size of fines for violations96. The weight of the literature on the need for optimizing enforcement is moderate; the research gap is in rigorously comparing different approaches and determining the most effective methods.

There is a need for empirical evidence on how to most effectively enforce smoke-free policies. Research is needed on how long a grace period (if any) is optimal and whether there are contextual differences across LMICs that suggest different approaches for different jurisdictions. The different enforcement strategies should be studied and compared for effectiveness. There is also a need for research on the most cost-effective ways of enforcing smoke-free policies. Should equal effort be put into training city officers, educating venue managers, and communicating to the public about their role in enforcement? What size fines work best in getting attention while still being realistic and fair to people of all income levels? Answering these questions could make implementation more efficient and effective. Research approaches can include analysis of what has been done across various jurisdictions to date. Additionally, researchers can test new technologies, such as mobile phone apps, for reporting violations, that may support enforcement in relatively inexpensive ways97,98.

Learning how to rejuvenate stalled smoke-free policies

There are numerous cases where smoke-free policies have been enacted but are not achieving high compliance14,24,63,66. In some cases, no implementation plan was made after a policy was passed. In other cases, implementation was weak or compliance faded over time. Civil society and government organizations have used various tactics for reinvigorating smoke-free policies. In India, joint government–NGO communication campaigns, legal actions seeking information from enforcement officials, and youth-led education efforts aided better compliance72. In Mexico City, a clearer, comprehensive smoke-free policy was used to replace a more cumbersome policy that allowed venues to have designated smoking areas76. In the Philippines, advocates created a task force of people in government service that worked cooperatively with the business sector, medical groups, and city government to raise awareness and compliance68. The weight of the literature on the problem of stalled smoke-free policies is moderate; the research gap is learning approaches and tools to reinvigorate these policies.

An important line of research is the development of a set of proven approaches or tools for improving compliance in places where implementation has stalled. Some areas to consider are: where the weak points of the particular implementation effort are, how to assess the appropriateness of the enforcement agency, how to re-establish political will to enforce policies if they fade, when to launch a new communication campaign (and what the focus and target audience of the campaign should be)84, and how to involve new organizations or constituencies in the enforcement effort. Approaches that have successfully been used in the past67,68,76 would benefit from replication, refinement, and consolidation into a resource for LMICs.

Learning how to increase ground-level will to enforce policies

In some LMICs, there is a lack of motivation to enforce smoke-free policies at the ground level24,25,66,82,99-101. Enforcement of smoke-free policies typically involves both enforcement officers and venue managers. Enforcement officers may not feel they have time or may think that public smoking is not a problem that warrants their attention. Some enforcement officers have said they have more important crimes to address101. Others may lack the will to enforce a policy because of lack of confidence that the government will back them if they are challenged25. In other cases, it is the regional health departments that are not sufficiently supportive66. In restaurants and retail locations, venue managers report having conflicts about enforcing a policy among their customers, on whom their livelihood depends27,99. Some managers have said they would prefer if a government agency did the enforcement rather than asking them to do it99. The weight of the evidence on the problem of ground-level enforcement is moderate; the research gap is in learning how to address this problem.

Research is needed on what actions can be taken to increase the will to enforce a smoke-free policy. Possible solutions may involve actions by civil society to show public support for smoke-free venues or using public shaming or praise to motivate action. Researchers can also examine how various jurisdictions have successfully addressed this problem and then replicating these approaches. Existing reports, of lessons learned, detail some successful creative efforts by members of civil society to hold governments accountable and increase ground-level enforcement24,68, but there has been little systematic work to identify if the necessary tactics vary by cultural context or legal structures.

Developing a conceptual framework that explains implementation

The review found little discussion of the behavioral science or policy theory involved in implementing smoke-free policies. In 1991, Pederson et al.87 created a preliminary model hypothesizing that compliance with smoke-free policies is a factor of environmental support, personality, and attitudes. More recently, a qualitative study in Israel used the behavioral ecological model to explore contingencies of reinforcement around non-compliance with a smoke-free policy in pubs and bars88. Work has also been conducted in Albania, Bulgaria and Greece to look into predictors of compliance, as well as non-smokers’ assertiveness to confront smokers89-92. The literature shows a lack of a general conceptual framework that explains how implementation of smoke-free laws works. The weight of evidence for the need for a conceptual framework is moderate to low; the gap that remains is in integrating and updating existing work into a cohesive framework.

An accurate conceptual framework for how smoke-free policies work would help guide efficient implementation of new smoke-free policies and troubleshoot existing implementation efforts. This framework could be designed to explain the social and psychological processes involved in changing a smoking social norm to a non-smoking one. Such a framework could inform communications messaging, enforcement, and advocacy approaches. Sources for framework development could come from a variety of relevant fields including behavioral science, communications, and criminal justice. Existing theoretical work can be incorporated into a new conceptual framework that considers:

How do social norms change and legal enforcement intersect in creating a successful smoke-free policy, and what factors matter most? What is the process by which a policy becomes ‘self-enforcing’?

Do differences such as whether a society is collectivist/individualist or the type of governance matter in how a smoke-free policy is best implemented? For example, poor compliance with a smoke-free policy in China was explained by a strong cultural desire to keep harmony and avoid disputes with others, leaving people unwilling to confront smokers36.

Are different enforcement approaches needed in different venue types? Schools, public transportation, government offices, restaurants, private workplaces, worship venues etc. have different social and power dynamics that may influence enforcement. For example, business managers can punish subordinates who smoke, but restaurant managers may not want to offend customers. Understanding these dynamics could lead to more effective enforcement methods.

How do changes in the environment (e.g. advertising bans, counter-marketing campaigns) affect public compliance with smoke-free policies?102-104

A conceptual framework would be a valuable way to frame, organize, and improve implementation of smoke-free policies.

CONCLUSIONS

We believe the research in the avenues presented can assist in strengthening and streamlining implementation of smoke-free policies in LMICs and thus improve public health. We propose research in five major categories: identifying the critical lessons learned for effective implementation, evaluating different enforcement approaches, learning how to rejuvenate stalled smoke-free policies, learning how to increase ground-level will to enforce policies, and developing a conceptual framework that explains implementation. Research in these topics is both feasible and potentially powerful in advancing successful implementation of smoke-free policies in LMICs to protect public health.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none was reported.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING

There was no source of funding for this research.

PROVENANCE AND PEER REVIEW

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation GBD Results Tool. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2006. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44324/. Accessed February 11, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callinan JE, Clarke A, Doherty K, Kelleher C. Legislative smoking bans for reducing secondhand smoke exposure, smoking prevalence and tobacco consumption. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2010;(4):CD005992. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005992.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akhtar PC, Currie DB, Currie CE, Haw SJ. Changes in child exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (CHETS) study after implementation of smoke-free legislation in Scotland: National cross sectional survey. BMJ. 2007;335(7619):545. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39311.550197.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juster HR, Loomis BR, Hinman TM, et al. Declines in hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction in New York state after implementation of a comprehensive smoking ban. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(11):2035–2039. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackay D, Haw S, Ayres JG, Fischbacher C, Pell JP. Smoke-free legislation and hospitalizations for childhood asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(12):1139–1145. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopkins DP, Razi S, Leeks KD, Priya Kalra G, Chattopadhyay SK, Soler RE. Smokefree policies to reduce tobacco use: A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(2):S275–S289. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffman SJ, Tan C. Overview of systematic reviews on the health-related effects of government tobacco control policies. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:744. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2041-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton WL, Biener L, Brennan RT. Do local tobacco regulations influence perceived smoking norms? Evidence from adult and youth surveys in Massachusetts. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(4):709–722. doi: 10.1093/her/cym054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegel M, Albers AB, Cheng DM, Hamilton WL, Biener L. Local restaurant smoking regulations and the adolescent smoking initiation process: Results of a multilevel contextual analysis among Massachusetts youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(5):477–483. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.5.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agaku IT, Obadan EM, Odukoya OO, Olufajo O. Tobacco-free schools as a core component of youth tobacco prevention programs: A secondary analysis of data from 43 countries. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(2):210–215. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drope J, Schluger N, Cahn Z, et al. The Tobacco Atlas. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Vital Strategies; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization . Protection from exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke: Policy recommendations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. https://www.who.int/tobacco/resources/publications/wntd/2007/PR_on_SHS.pdf. Accessed 11 February, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization . WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic 2017: Monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. https://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2017/en/. February 11, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42811/9241591013.pdf;jsessionid=91381E5AC183B3FF4CEDC181640BE853?sequence=1. Updated 2005. Accessed February 11, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. http://www.who.int/fctc/signatories_parties/en/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- 17.World Health Organization . Guidelines for implementation of Article 8 of the WHO FCTC. Geneva: World Health Organization, FCTC Conference of Parties; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thrasher JF, Reynales-Shigematsu LM, BaezcondeGarbanati L, et al. Promoting the effective translation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: a case study of challenges and opportunities for strategic communications in Mexico. Eval Health Prof. 2008;31(2):145–166. doi: 10.1177/0163278708315921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donahoe JT, Titus AR, Fleischer NL. Key Factors Inhibiting Legislative Progress Toward Smoke-Free Coverage in Appalachia. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(3):372–378. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eriksen MP, Mackay J, Schluger NW, Islami F, Drope J. The Tobacco Atlas. 5th. Atlanta, Georgia: American Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Implementation and assistance. http://www.who.int/fctc/implementation/en/. Accessed June 20, 2014.

- 22.Byron MJ, Cohen JE, Gittelsohn J, Frattaroli S, Nuryunawati R, Jernigan DH. Influence of religious organisations’ statements on compliance with a smoke-free law in Bogor, Indonesia: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e008111. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byron MJ, Cohen JE, Frattaroli S, Gittelsohn J, Jernigan DH. Using the theory of normative social behavior to understand compliance with a smoke-free law in a middle-income country. Health Educ Res. 2016;31(6):738–748. doi: 10.1093/her/cyw043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drope J. Tobacco Control in Africa: People, Politics, and Policies. London, New York: Anthem Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drope JM. The politics of smoke-free policies in developing countries: Lessons from Africa. CVD Prevention and Control. 2010;5:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cvdpc.2010.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aherrera A, Carkoglu A, Hayran M, et al. Factors that influence attitude and enforcement of the smoke-free law in Turkey: a survey of hospitality venue owners and employees. Tob Control. 2016:26. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner MM, Rimal RN, Lumby E, et al. Compliance with tobacco control policies in India: an examination of facilitators and barriers. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2016;20(3):411–416. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang J, Modi BV, Tamplin SA, Aghi MB, Dave PV, Cohen JE. Air nicotine levels in public places in ahmedabad, India: before and after implementation of the smoking ban. Indian J Community Med. 2015;40(1):27–32. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.149266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rutkow L, Vernick JS, Tung GJ, Cohen JE. Creating smoke-free places through the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):1748–1753. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navas-Acien A, Carkoglu A, Ergor G, et al. Compliance with smoke-free legislation within public buildings: a cross-sectional study in Turkey. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(2):92–102. doi: 10.2471/blt.15.158238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hill MJ, Hupe PL. Implementing public policy: an introduction to the study of operational governance. 2nd. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riessman CK. Narrative methods for the human sciences. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thrasher JF, Perez-Hernandez R, Swayampakala K, Arillo-Santillan E, Bottai M. Policy support, norms, and secondhand smoke exposure before and after implementation of a comprehensive smoke-free law in Mexico city. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(9):1789–1798. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoj V, Alderete M, Ruiz E, Hasdeu S, Linetzky B, Ferrante D. The impact of a 100% smoke-free law on the health of hospitality workers from the city of Neuquen, Argentina. Tob Control. 2010;19(2):134–137. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.032862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schoj V, Sebrie EM, Pizarro ME, Hyland A, Travers MJ. Informing effective smokefree policies in Argentina: air quality monitoring study in 15 cities (2007-2009) Salud Publica Mex. 2010;52(Suppl 2):S157–S167. doi: 10.1590/S0036-36342010000800011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X, Gao J, Zhang Z, et al. Lessons from an evaluation of a provincial-level smoking control policy in Shanghai, China. PloS ONE. 2013;8(9):e74306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campelo DG. WHO smoke-free city case study: Recife breathing better: case study of smoke-free policy implementation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abe TM, Scholz J, de Masi E, Nobre MR, Filho RK. Decrease in mortality rate and hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction after the enactment of the smoking ban law in Sao Paulo city, Brazil. Tob Control. 2016 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalkhoran S, Sebrie EM, Sandoya E, Glantz SA. Effect of Uruguay’s National 100% Smokefree Law on Emergency Visits for Bronchospasm. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(1):85–88. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo B, Wan L, Liang L, Li T. The Effects of Educational Campaigns and Smoking Bans in Public Places on Smokers’ Intention to Quit Smoking: Findings from 17 Cities in China. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:853418. doi: 10.1155/2015/853418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turan PA, Ergor G, Turan O, Doganay S, Kilinc O. [The changes in smoking related behaviours and second hand smoke after the smoking ban in Izmir] Tuberk Toraks. 2014;62(1):27–38. doi: 10.5578/tt.6133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abidin NZ, Zulkifli A, Abidin EZ, et al. Knowledge, attitude and perception of second-hand smoke and factors promoting smoking in Malaysian adolescents. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(7):856–861. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gvinianidze K, Bakhturidze G, Magradze G. Study of implementation level of tobacco restriction policy in cafes and restaurants of Georgia. Georgian Med News. 2012;(206):57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crosbie E, Sebrie EM, Glantz SA. Strong advocacy led to successful implementation of smokefree Mexico City. Tob Control. 2011;20(1):64–72. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nemakhavhani TR, Akinsola HA. Survey of bar-lounges and restaurants regarding compliance with the current smoke-free regulation in Thulamela Municipality, South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2016;8(2):1–6. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v8i2.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thrasher JF, Nayeli Abad-Vivero E, Sebrie EM, et al. Tobacco smoke exposure in public places and workplaces after smoke-free policy implementation: a longitudinal analysis of smoker cohorts in Mexico and Uruguay. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28(8):789–798. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ye X, Chen S, Yao Z, et al. Smoking behaviors before and after implementation of a smoke-free legislation in Guangzhou, China. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:982. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2353-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jovicevic A, Krstev S, Lazarevic N, Dzeletovic A, Pesic I, Ristic S. 3519 POSTER Impact of the new smoke-free law in Serbia. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47 doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(11)71175-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yong HH, Foong K, Borland R, et al. Support for and reported compliance among smokers with smoke-free policies in air-conditioned hospitality venues in Malaysia and Thailand: findings from the International Tobacco Control Southeast Asia Survey. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2010;22(1):98–109. doi: 10.1177/1010539509351303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chang SH, Delgermaa V, Mungun-Ulzii K, Erdenekhuu N, Odkhuu E, Huang SL. Support for smoke-free policy among restaurant owners and managers in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. Tob Control. 2009;18(6):479–484. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.030486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Janghorbani M, Taghdisi MH, Vingard E. Public opinion on tobacco control policies in restaurants in Isfahan, Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2004;7(4):260–266. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Owusu-Dabo E, Lewis S, McNeill A, Gilmore A, Britton J. Support for smoke-free policy, and awareness of tobacco health effects and use of smoking cessation therapy in a developing country. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:572. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Radwan GN, Emam AH, Maher KM, Mehrez M, ElSayed N, El-Nahas GM. Public opinion on smoke-free policies among Egyptians. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(10):1412–1417. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khan JA, Amir Humza Sohail AM, Arif Maan MA. Tobacco control laws in Pakistan and their implementation: A pilot study in Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66(7):875–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bhat N, Oza S, Reddy JJ, Mitra R, Patel R, Singh S. Effect of anti-smoking legislation in public places. Addict Health. 2015;7(1-2):87–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Onigbogi OO, Odukoya O, Onigbogi M, Sekoni O. Knowledge and attitude toward smoke-free legislation and second-hand smoking exposure among workers in indoor bars, beer parlors and discotheques in Osun State of Nigeria. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(4):229–234. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kegler MC, Hua X, Solomon M, Wu Y, Zheng PP, Eriksen M. Factors associated with support for smoke-free policies among government workers in Six Chinese cities: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goel S, Singh RJ, S D, S A. Public opinion about smoking and smoke free legislation in a district of North India. Indian J Cancer. 2014;51(3):330–334. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.146788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rashid A, Manan AA, Yahya N, Ibrahim L. The support for smoke free policy and how it is influenced by tolerance to smoking - experience of a developing country. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e109429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ministry of Health People’s Republic of China . 2007 China Tobacco Control Report: Create a smoke-free environment, enjoy a happy life. Beijing: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barnoya J, Arvizu M, Jones MR, Hernandez JC, Breysse PN, Navas-Acien A. Secondhand smoke exposure in bars and restaurants in Guatemala City: before and after smoking ban evaluation. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22(1):151–156. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9673-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.ITC Project and Office of Tobacco Control China CDC . ITC China project report: Findings from the Wave 1 to 3 Surveys (2006-2009) Beijing: China Modern Economic Publishing House; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fong GT, Sansone G, Yan M, Craig L, Quah AC, Jiang Y. Evaluation of smoke-free policies in seven cities in China, 2007-2012. Tob Control. 2015;24:iv14–iv20. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goswami H. WHO smoke-free city case study: Experience of Chandigarh as a smoke-free city. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lopez CM, Ruiz JA, Shigematsu LM, Waters HR. The economic impact of Mexico City’s smoke-free law. Tob Control. 2011;20(4):273–278. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.036467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jhanjee S. Tobacco control in India - Where are we now? Delhi Psychiatry Journal. 2011;14(1) [Google Scholar]

- 67.Global Smokefree Partnership Smokefree air law enforcement: Lessons from the field. http://www.tobaccoindustrywatchbd.org/contents/uploaded/smokefreeairLawEnforcementlessonsfromthefield.pdf. Published 2009. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- 68.American Cancer Society, International Union Against Cancer (UICC) Enforcing strong smoke-free laws: The advocate’s guide to enforcement strategies. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 69.World Health Organization, International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease . Building capacity for tobacco control: training package. 2011. 1. Protect people from tobacco smoke: Smoke-free environments. [Google Scholar]

- 70.World Health Organization . Making your city smoke-free: workshop package. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arul R, Angelis S, Ansari SAT, Kavitha G. WHO smoke-free city case study: Towards breathing clean air in Chennai - A smoke-free city case study. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dawson J, Singh RJ. Smokefree City: Chandigarh. Edinburgh: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sadykova J. WHO smoke-free city case study: Almaty -the first smoke-free city in the post Soviet region. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Odhiambo F, Mutai J, Endau W, Anaya L, Matete V, Nato J. WHO smoke-free city case study: Smoke-free Nakuru – the first east African city implementing subnational smoke-free policy. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Casaubón ME, Ahued-Ortega A, Robles-García R, et al. WHO smoke-free city case study: Towards 100% smoke-free environment: the case study of Mexico City, Mexico. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dawson J, Romo J, Molinari M, Garrido L. Smokefree city: Mexico DF. Edinburgh: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Villarreiz D. WHO smoke-free city case study: Advancing the enforcement of the smoking ban in public places – Davao City, Philippines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 78.World Health Organization . WHO smoke-free city case study: Tobacco-free cities for smoke-free air: A case study in Mecca and Medina. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lambert P, Donley K. Best practices in implementation of Article 8 of the WHO FCTC case study: Seychelles. Geneva: WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lambert P, Donley K. Best practices in implementation of Article 8 of the WHO FCTC case study: South Africa. Geneva: WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ha-Iaconis T, Morton R, Bauer JE, Westmaas JL, Glynn TJ. Clearing the air: Communicating a smoke-free Viet Nam. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jain D, Jadav A, Rhoten K, Bassi A. The Enforcement of India’s tobacco control legislation in the state of Haryana: A case study. World Med Health Policy. 2014;6(4):331–346. doi: 10.1002/wmh3.116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Persai D, Panda R, Gupta A. Examining Implementation of Tobacco Control Policy at the District Level: A Case Study Analysis from a High Burden State in India. Adv Prev Med. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/4018023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Obeidat NA, Ayub HS, Bader RK, et al. Public support for smoke-free policies in Jordan, a high tobacco burden country with weak implementation of policies: Status, opportunities, and challenges. Glob Public Health. 2016;11(10):1246–1258. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1065896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.World Health Organization . Making cities smoke-free. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Efroymson D, Alam SM. Enforcement of tobacco control law: A guide to the basics. Ottawa, ON: HealthBridge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pederson LL, Wanklin JM, Bull SB, Ashley MJ. A conceptual framework for the roles of legislation and education in reducing exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Am J Health Promot. 1991;6(2):105–111. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-6.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Baron-Epel O, Satran C, Cohen V, Drach-Zehavi A, Hovell MF. Challenges for the smoking ban in Israeli pubs and bars: analysis guided by the behavioral ecological model. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2012;1(1):28. doi: 10.1186/2045-4015-1-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Aspropoulos E, Lazuras L, Rodafinos A, Eiser JR. Can you please put it out? Predicting non-smokers’ assertiveness intentions at work. Tob Control. 2010;19(2):148–152. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lazuras L, Eiser JR, Rodafinos A. Predicting smokers’ non-compliance with smoking restrictions in public places. Tob Control. 2009;18(2):127–131. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.025841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lazuras L, Zlatev M, Rodafinos A, Eiser JR. Smokers’ compliance with smoke-free policies, and non-smokers’ assertiveness for smoke-free air in the workplace: a study from the Balkans. Int J Public Health. 2012;57(5):769–775. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Melonashi E. Understanding non-compliance with smoke-free policies in public places in Albania [dissertation] Sheffield, England: University of Sheffield; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Leischow SJ, Ayo-Yusuf O, Backinger CL. Converging research needs across framework convention on tobacco control articles: making research relevant to global tobacco control practice and policy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(4):761–766. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.World Health Organization . WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2009: Implementing smoke-free environments. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gruer L, Tursan d’Espaignet E, Haw S, Fernandez E, Mackay J. Smoke-free legislation: global reach, impact and remaining challenges. Public Health. 2012;126(3):227–229. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ay P, Evrengil E, Guner M, Dagli E. Noncompliance to smoke-free law: which hospitality premises are more prone? Public Health. 2016;141:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.World Health Organization Projects on mobile health (mHealth) for tobacco control. http://www.who.int/tobacco/mhealth/projects/en/. Accessed June 21, 2014.

- 98.Arizona Department of Health Services Online complaint submittal form. https://azdhs.gov/preparedness/epidemiology-disease-control/smoke-free-arizona/index.php#report. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- 99.Karimi KJ, Ayah R, Olewe T. Adherence to the Tobacco Control Act, 2007: presence of a workplace policy on tobacco use in bars and restaurants in Nairobi, Kenya. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e012526. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Barnoya J, Monzon JC, Briz P, Navas-Acien A. Compliance to the smoke-free law in Guatemala 5-years after implementation. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:318. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2960-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Travers MJ, Nayak NS, Annigeri VB, Billava NN. Indoor air quality due to secondhand smoke: Signals from selected hospitality locations in rural and urban areas of Bangalore and Dharwad districts in Karnataka, India. Indian J Cancer. 2015;52(4):708–713. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.178447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Burns DM, Axelrad R, Bal D, et al. Report of the Tobacco Policy Research Study Group on smoke-free indoor air policies. Tob Control. 1992;1:S14–S18. doi: 10.1136/tc.1.suppl1.s14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kaushik U, Gupta VK, Arora M. O201 Youth advocacy to strengthen smoke free policy: Lessons from India. Glob Heart. 2014;9(1):e56. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.03.1406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.World Health Organization . WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic 2008: The MPOWER package. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.