Abstract

Tau, a microtubule-associated protein, is linked to many neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD). A recent study uncovered a new pathway for its secretion, leading to its transcellular uptake, while another study found that tau secreted from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) modeling trisomy-related AD caused synaptic impairment in rats. These findings could inform tau-directed therapies.

Neurodegenerative diseases are one of our biggest biomedical challenges. In the absence of effective medical therapies, over 130 million people worldwide will have AD and related dementias by 2050 [1]. Tau is a microtubule-associated protein with myriad functions [2] and has emerged as a critical player in several neurodegenerative diseases. In addition to its pathognomonic aggregation as neurofibrillary tangles in AD, tau is implicated in other degenerative brain conditions [3], including frontotemporal dementia, corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, all insidious, progressive, and devastating neurological diseases.

Increasing evidence indicates that tau spreads from cell to cell, highlighting an opportunity to understand mechanisms surrounding extracellular tau [4]. How does tau get into the extracellular space? Once it is there, where does it go? What does it do? These are important questions since neurodegenerative diseases preferentially manifest in one brain region and progressively extend to others, probably through a combination of regional tau vulnerability and physical tau spread. If we could stop tau ‘spread’, could we halt the development of clinical diseases?

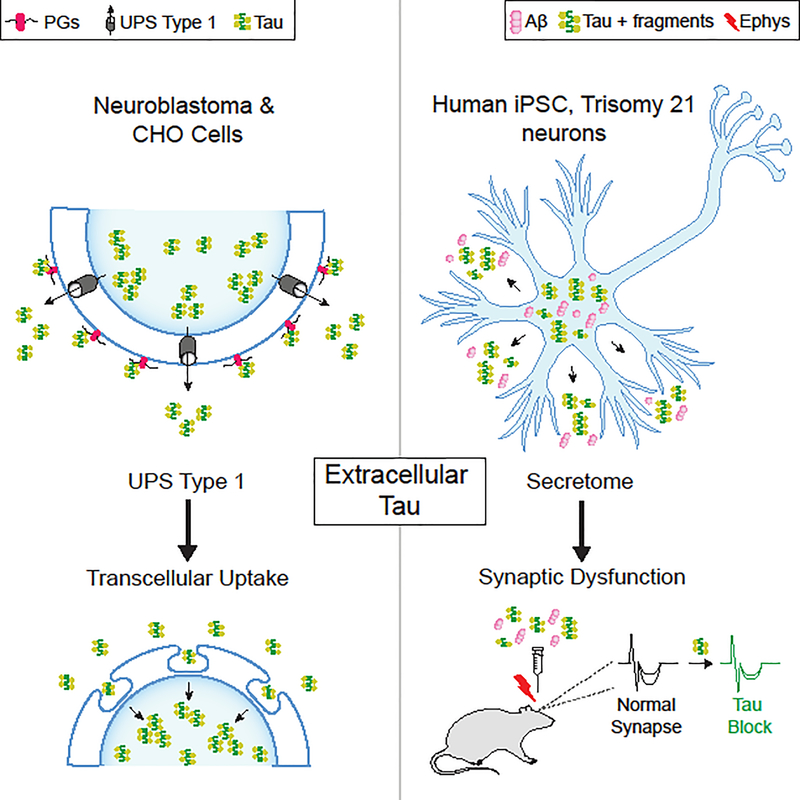

In a recent study using neuroblastoma and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, Katsinelos and colleagues [5] found that an unconventional secretion pathway translocated tau directly across the membrane and into the extracellular space. Tau secretion increased with its hyperphosphorylation. Furthermore, its export was facilitated by sulfated proteoglycans (PGs) at the cell surface, where a high density of tau clustered before its release into culture medium. Importantly, the extracellular tau was taken up by neighboring cells, where it appeared to aggregate. Thus, transcellular spread of tau followed its unconventional secretion (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Extracellular Tau Undergoes Unconventional Secretion in Cell Lines and Induces Synaptic Deficits when Derived from Trisomy, Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC) Neurons. (A) Work by Katsinelos et al. [5]: extracellular tau derived from its overexpression in neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y) and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell lines showed evidence of export via unconventional pathway secretion type 1 (UPS 1). The secretion of extracellular tau is facilitated by sulfated proteoglycans (PGs) at the cell surface, where tau clusters before its release into culture medium. Tau is then taken up by neighboring cells, where it appears to aggregate. Thus, the transcellular spread of tau follows UPS 1 secretion. (B) Work by Hu et al. [8]: extracellular tau and its fragments were found along with amyloid beta (Aβ) in secretomes of human-derived iPSCs differentiated into neurons with trisomy 21, modeling Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Secretomes injected into the rat brain caused synaptic dysfunction through extracellular tau. Immunodepletion of tau, but not Aβ, blocked secretome-induced synaptic deficits measured by in vivo electrophysiology. Of note, extracellular tau secreted from amyloid precursor protein gene (APP) duplication or PS1 mutation neurons did not induce acute synaptic deficits. Not shown in either panel are characteristics or mechanisms of tau not examined in the two studies, including vesicular tau secretion, mechanisms of tau uptake, aggregation and/or phosphorylation status of tau, or propagation of tau.

What is unconventional tau secretion and why could it be important? Since tau lacks signal sequences that enable delivery to the plasma membrane via the classical endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-Golgi pathway, the authors tested whether it could follow an alternative route, unconventional protein secretion (UPS) Type 1, which is used by FGF2 and the HIV-Tat proteins [6]. In support of this, tau bound to inner leaflet proteins of the plasma membrane, physically disrupting the membrane and anchoring to outer leaflet PGs, and, as previously observed [7], then traversed the membrane despite inhibitors of ER-Golgi-dependent secretion. Each of these elegant findings is important because, collectively, they represent distinct targets for the development of therapeutics against tau aimed at halting its extracellular secretion to stop ‘spread’ of tau.

How tau physically exits the cell in UPS 1 secretion, and what comes next, remain unsolved. Does tau itself form a pore? Does it cross a pore assembled by other yet-identified proteins? Does the process require energy or other key substrates besides PGs? Can UPS 1-secreted forms of tau act like ‘seeds’ on normal tau to make propagating tau. Is tau secretion a strictly pathological process, or could it also be a physiological one used by endogenous tau to transduce signals across cells? A further understanding of tau secretion paves a way to counter its potential pathophysiological consequences.

Once secreted, what are the functional consequences of extracellular tau? In another recent study, Hu and colleagues [8] revealed one possible answer by examining the content of secreted media, or secretomes, of human-derived iPSCs differentiated into neurons carrying causal mutations of AD, including trisomy 21, amyloid precursor protein gene (APP) duplication, or a presenilin 1 (PS1) mutation. When secretomes of these neurons were injected into the rat brain, those derived from individuals with trisomy 21 caused synaptic dysfunction, surprisingly, through extracellular tau (Figure 1B); that is, immunodepletion of tau, but not of amyloid beta, blocked secretome-induced deficits in long-term potentiation (LTP) in vivo, a robust measure of synaptic plasticity that underlies memory [9]. Curiously, extracellular tau secreted from trisomy neurons, but not APP duplication or PS1 mutation neurons, induced acute synaptic deficits. It will be interesting to know whether APP-independent abnormalities resulting from chromosome 21 triplication contribute to extracellular tau toxicity.

Hu and colleagues’ approach of leveraging secretomes from iPSC neurons and probing their synaptotoxicity in rodent brains in vivo lends itself to increased human relevance for several reasons. In efforts to develop therapies, human neurons could be used to begin to address the lack of translation from mouse studies into human AD trials. Furthermore, secretomes from human cells with causal AD mutations could more closely recapitulate the extracellular milieu causing the pathophysiology. This is particularly important since the conformations, assemblies, and concentrations of extracellular tau species most linked to human diseases are currently unknown. Finally, testing in vivo LTP as a functional outcome of secreted extracellular tau represents a compelling and biologically meaningful measure, because this form of synaptic plasticity underlies learning and memory, a highly valued brain function eroded by neurodegenerative diseases.

Together, the two studies converge upon extracellular tau, revealing UPS 1 as a secretory path [5] and synaptic dysfunction as a functional outcome in vivo [8], thus further highlighting its importance as a therapeutic target. Reflecting on the studies together, one wonders whether UPS 1-mediated tau secretion characterized in neuroblastoma and CHO cell lines extends to human iPSCs, if transcellular tau uptake alters cellular functions such as synaptic plasticity, whether tau acts with co-pathogenic proteins, such as amyloid beta and others in the extracellular space, and whether either of the cellular models and their findings are truly relevant to the human condition. Ultimately, antibodies, small molecules, or other pharmacological agents that decrease the production, uptake, binding, spread, or function of extracellular tau could represent therapeutic approaches [10] that can be tested in vitro. Advancing promising treatments to human-relevant in vivo models, such as nonhuman primates, will increase our chance of success in clinical trials and, ultimately, of defeating disease.

In conclusion, these two studies shed light on mechanisms surrounding extracellular tau, raise new questions about its secretion and selective synaptic toxicity, and highlight additional therapeutic opportunities in countering the tau-linked onset and progression of neurodegenerative disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health NS092918 (D.B.D.) and the American Federation of Aging Research (D.B.D.). Arturo Moreno designed and composed the figure and John Bou crafted the title.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Prince M et al. (2015) World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Economic Impact of Dementia, An Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends, Alzheimer’s Disease International

- 2.Morris M et al. (2011) The many faces of tau. Neuron 70, 410–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee VM et al. (2001) Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu Rev Neurosci 24, 1121–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mudher A et al. (2017) What is the evidence that tau pathology spreads through prion-like propagation? Acta Neuropathol Commun 5, 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katsinelos et al. Unconventional secretion mediates the trans-cellular spreading of tau. Cell Reports (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabouille C (2017) Pathways of unconventional protein secretion. Trends Cell Biol 27, 230–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chai X et al. (2012) Constitutive secretion of tau protein by an unconventional mechanism. Neurobiol Dis 48 (3), 356–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu et al. Extracellular forms of Ab and tau from iPSC models of Alzheimer’s disease disrupt synaptic plasticity. Cell Reports (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nabavi S et al. (2014) Engineering a memory with LTD and LTP. Nature 511,348–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes BB and Diamond MI (2014) Prion-like properties of Tau protein: the importance of extracellular Tau as a therapeutic target. J Biol Chem 289, 19855–19861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]