Abstract

Background

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is one of the most troubling symptoms of cancer patients during chemotherapy, and no gold standard for the treatment of CRF has been established.

Objective

This study aimed to examine the effects of the Baduanjin qigong on patients with colorectal cancer and CRF, and to explore its intervention effects.

Methods

This was an open-label, randomized controlled clinical trial. Ninety patients with chemotherapy-treated colorectal cancer and CRF were randomized to a Baduanjin exercise group or a routine care group. The primary outcome was the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI) score at 24 weeks. The secondary outcomes were the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores at 24 weeks.

Results

There were no significant differences between the two groups in CRF level at baseline and 12 weeks. At 24 weeks, the proportion of patients with moderate-to-severe CRF was significantly smaller in the exercise group than in the control group (23.2 vs. 59.1%, p < 0.01). The KPS and PSQI scores were similar in the two groups at baseline and 12 weeks, but they were significantly higher and lower, respectively, at 24 weeks in the exercise group compared with the control group (KPS score: 89.3 ± 8.3 vs. 75.2 ± 11.5, p < 0.01; PSQI score: 4.1 ± 1.1 vs. 6.9 ± 2.0, p < 0.01). Significant time-group interactions were observed for all three scores (all p < 0.01).

Conclusions

Baduanjin qigong exercise can relieve CRF in patients with colorectal cancer undergoing chemotherapy and can improve their physical activity level and their quality of sleep.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Chemotherapy, Cancer-related fatigue, Baduanjin qigong, Traditional Chinese medicine

Introduction

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is a painful, persistent, subjective body, emotional, and/or cognitive fatigue disproportionate to recent activities, associated with cancer or cancer treatment, and often accompanied by dysfunction [1]. About 60–96% of patients who receive anticancer treatments complain of fatigue [2]. During chemotherapy, patients often display fatigue, pain, nausea, vomiting, and other symptoms. Fatigue is one of the most perplexing symptoms for patients [3]. Chemotherapy is an important factor in the occurrence or aggravation of CRF, and CRF is one of the main reasons for interruption of treatment or exacerbation of the disease [4]. More than 6 months after cancer treatment, approximately 30% of patients still report moderate-to-severe ongoing fatigue [5]. The factors contributing to CRF include the cancer itself, cancer treatment, and chronic diseases such as anemia, pain, depression, anxiety, mental fatigue, and lack of exercise [1]. The pathogenesis of CRF is still unknown, but might include proinflammatory cytokines, growth factors, circadian rhythm modulation, adrenal axis interruption, serotonin imbalance, afferent activation of the vagus nerve, and the production or use of abnormal adenosine triphosphate [6].

CRF belongs to the category of mental deficiency in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and represents various chronic asthenia syndromes characterized by insufficiency of visceral function and deficiency of Qi, blood, Yin, and Yang. Currently, there is no recognized standard for the treatment of CRF [7], but exercise might be the only effective CRF intervention proven by first-degree evidence [8]. A meta-analysis confirmed that aerobic exercise has a definite effect on CRF in patients with breast cancer [9].

TCM believes that Baduanjin qigong can help dredge meridians, Qi, and blood, regulate visceral function, strengthen the body and dispel evil, and strengthen physical fitness in order to improve sleep, relieve bad mood, and improve blood lipid metabolism [10, 11, 12]. The Baduanjin is a series of aerobic exercises believed to impart a silky quality to the body and its energy, and to improve general health. It can be broken down into eight exercises that focus on different physical areas and meridians [13, 14].

Nevertheless, the impact of the Baduanjin on the CRF of patients with colorectal cancer is unknown. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to examine the effects of the Baduanjin on patients with colorectal cancer and CRF and to explore its intervention effects. The results could provide a method for managing CRF in patients with colorectal cancer.

Subjects and Methods

Setting and Patients

This was an open-label, randomized controlled clinical trial. It was conducted at the Department of Oncological Surgery, Kunshan Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jiangsu Province, China, where more than 100 cases of colorectal cancer are treated every year. The participants were patients with colorectal cancer undergoing chemotherapy between May 2016 and March 2018.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) >18 years of age; (2) surgical resection of gastrointestinal tumors by laparotomy or laparoscopy under general anesthesia; (3) pathological diagnosis of colorectal cancer, TNM stage I–III; (4) no prior history of chemotherapy; (5) being able to read and answer questionnaires by oneself; (6) suffering from CRF as assessed by the simple fatigue scale; (7) being able to use smart phones and the WeChat app; and (8) being aware of one's disease diagnosis and providing informed consent.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) cardiopulmonary disease, nerve, muscle, or joint disease, or other malignant tumors affecting movement; (2) mental illness or serious cognitive impairment and defects in language; (3) postoperative heart, cerebral vessel, or other serious complications; and (4) history of having participated in Baduanjin exercise.

Randomization and Interventions

Among the four wards, two were selected to conduct this study. The patients in one ward received the Baduanjin intervention, while the patients in the other ward received the routine care intervention. The random allocation sequence was generated by an independent statistician. The patients who met the inclusion criteria were assigned to the Baduanjin or routine care intervention wards in the order of admission.

The routine care group received routine CRF care [1], face-to-face health education about CRF, explanations about the evaluation methods, related symptoms, influencing factors, and intervention measures of CRF. The contents were simple and easy to understand.

In the Baduanjin exercise group, the Baduanjin exercise intervention was carried out in addition to the routine care of CRF. The Baduanjin intervention team was composed of 1 head nurse, 1 oncologist, 1 rehabilitation specialist, 1 oncology nurse specialist, 2 TCM nurses, and 1 nursing postgraduate. The team members were trained in systematic colorectal cancer chemotherapy, Baduanjin exercise, and cancer-related knowledge communication. The oncology nurse specialist explained the possible effect of Baduanjin exercise on CRF. The TCM nurses explained the effect of the Baduanjin exercise on the meridians, viscera, and emotion, and explained the mechanism of Baduanjin exercise on CRF in common language.

Using the WeChat app, the patients were invited to watch videos explaining how to perform the exercises. The first course (40 min) explained and demonstrated the eight movements and natural breathing methods. During the second course (40 min), the patients performed the exercises and the study team observed and corrected the movements, if necessary.

During hospitalization, the patients practiced the Baduanjin from 16:00 to 17:00 every day, for at least 5 sessions/week and 20–40 min/session. The session was led by a TCM nurse. During the first session, the physician made an exercise prescription based on the patient's current health, cardiopulmonary function, chemotherapy symptoms, and physical fitness. A log was kept of all exercises.

During the chemotherapy period, the patients were asked to exercise at home, uploading pictures of them and of their log every day. Their families were also encouraged to exercise with their patients. In the WeChat group, videos were uploaded once a week.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI) score at 24 weeks. The secondary endpoints were the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores at 24 weeks.

The BFI was used to evaluate the CRF level of the patients [15]. The indicators include the degree of present fatigue, the degree of past-24-h fatigue, and the impact of the 24-h fatigue on emotion, action, work, relationships with others, and fun with life. The BFI is scored as follows: 0 = no fatigue, 1–3 = mild fatigue, 4–6 = moderate fatigue, and 7–10 = severe fatigue. The reliability coefficient of the scale was 0.97 and the validity coefficient was 0.92. The validated Chinese version is simple and easy to understand, with fewer entries and a better distinction for the degree of fatigue [16].

The KPS scale was first proposed in 1949 by Karnofsky to measure the body function of cancer patients, to assess the daily self-care ability and vitality of cancer patients, and to determine the degree of medical care [17]. It is now widely used to assess the functional status of cancer patients. The KPS is an objective evaluation index. It is scored 0–100 and higher scores indicate a better state.

The PSQI, proposed by Buysse et al. [18] in 1989, is currently the most commonly used scale for assessing sleep quality. The present study used a scale translated into Chinese and validated by Tsai et al. [19]. The scale assesses the quality of sleep in the last 1 month. There are 18 items, divided into 7 factors (sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep efficiency, sleep duration, sleep disturbances, daytime dysfunction, and hypnotics use). Each factor is divided into 4 grades scored 0–3. The total score is 0–21. A PSQI score ≥7 indicates sleep problems. After 2 weeks, the test-retest reliability was 0.83 and Cronbach's α coefficient was 0.84.

Data Collection

All patients completed all 3 questionnaires 3 times (at baseline, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks) at the hospital. The baseline BFI, KPS, and PSQI administrations were completed before the first chemotherapy course. A trained graduate student was available to provide explanations in a unified and standardized language.

Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

The sample size was estimated using the two-sample mean comparison formula n = 2[(uα+uβ)σ/δ]2, where α = 0.05, β = 0.1, uα = 1.96, and uβ = 1.28 for bilateral testing. The main test target of this study was the CRF scale, and the sample size was calculated based on this index. According to the formula, 41 patients were required in each group. Assuming a loss of 5%, 45 patients were recruited to each group.

SPSS 19 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all analyses. Categorical data are expressed as frequency and percentage. Continuous data are expressed as means ± standard deviation. The two groups were compared using the t test, χ2 test, or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to assess the differences in BFI, KPS, and PSQI scores during the intervention. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to measure the degree of CRF in the two groups of patients before and after the intervention. A two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the Patients

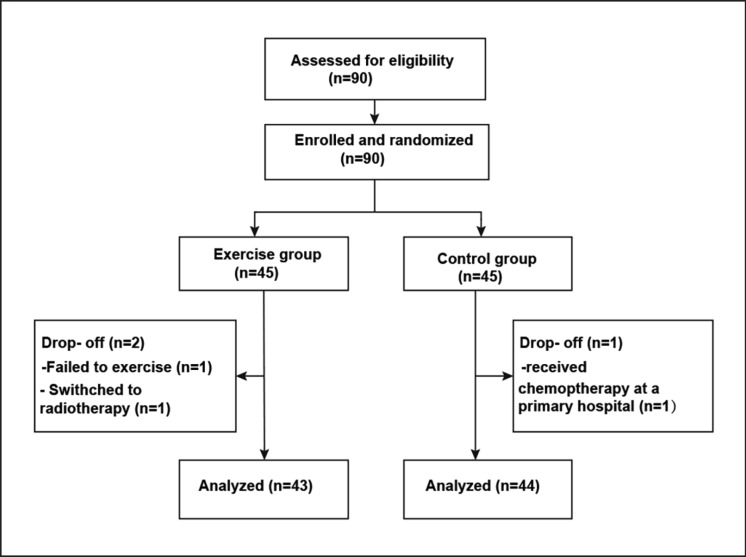

A total of 90 patients with colorectal cancer were enrolled. One patient in the routine care group (conversion to primary hospital chemotherapy) and 2 in the exercise group (1 failed to exercise and 1 was switched from chemotherapy to radiotherapy) dropped out. Finally, there were 43 patients in the exercise group and 44 in the routine care group (Fig. 1). Table 1 presents the characteristics of the patients. There were no differences between the two groups (all p > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients

| Baduanjin exercise group (n = 43) | Routine care group (n = 44) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n | |||

| Male | 26 | 30 | 0.507 |

| Female | 17 | 14 | |

| Age, years | 55.60±11.23 | 54.63±11.88 | 0.643 |

| Education, n | 0.638 | ||

| Junior high school | 10 | 8 | |

| Senior high school and middle special school | 23 | 22 | |

| Junior college, college graduate, and above | 10 | 14 | |

| Marital status, n | 0.866 | ||

| Life with spouse | 31 | 31 | |

| Unmarried, widowed, or divorced | 12 | 13 | |

| Stage, n | 0.721 | ||

| I | 10 | 13 | |

| II | 29 | 26 | |

| III | 4 | 5 | |

| Monthly family income, n | |||

| RMB <2,000 | 5 | 3 | 0.740 |

| RMB 2,000–5,000 | 11 | 12 | |

| RMB >5,000 | 27 | 29 | |

| Operation, n | |||

| Radical resection of rectal cancer | 25 | 28 | 0.663 |

| Radical operation of colon cancer | 18 | 16 | |

| Chemotherapy protocol, n | |||

| XELOX | 8 | 11 | 0.645 |

| FOLFOX | 22 | 23 | |

| FOLFIRI | 13 | 10 | |

| BFI score | 4.37±2.24 | 4.70±2.45 | 0.510 |

| KPS score | 76.51±11.31 | 74.77±14.06 | 0.527 |

| PSQI score | 10.51±1.45 | 10.45±2.13 | 0.884 |

XELOX, capecitabine and oxaliplatin; FOLFOX, folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin; FOLFIRI, folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil, and irinotecan; BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

CRF 12 and 24 Weeks after the Intervention

Table 2 presents the results of the BFI scale at baseline, as well as during and after the intervention. There were no significant differences between the two groups in the proportions of patients with mild, moderate, and severe CRF at baseline and at 12 weeks. At 24 weeks, the proportion of patients with moderate-to-severe CRF was significantly lower in the exercise group compared with the routine care group (23.2 vs. 59.1%, p < 0.01). Table 3 presents the BFI scores and shows that there was a significant time-group interaction (p < 0.01).

Table 2.

BFI scores before and after the intervention in the two groups

| Baduanjin exercise group (n = 43) | Routine care group (n = 44) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 0.850 | ||

| Mild | 17 (39.5) | 15 (34.1) | |

| Moderate | 16 (37.2) | 17 (38.6) | |

| Severe | 10 (23.3) | 12 (27.3) | |

| 12 weeks Mild | 18 (41.9) | 17 (38.6) | 0.750 |

| Moderate | 18 (41.8) | 17 (38.6) | |

| Severe | 7 (16.3) | 10 (22.8) | |

| 24 weeks | |||

| Missing | 2 (4.7) | 0 | <0.01 |

| Mild | 31 (72.1) | 18 (40.9) | |

| Moderate | 5 (11.6) | 20 (45.5) | |

| Severe | 5 (11.6) | 6 (13.6) |

All data are shown as n (%). Fisher's exact test. BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory.

Table 3.

BFI, KPS, and PSQI scores before and after the intervention

| Baduanjin exercise group (n = 43) |

Routine care group (n = 44) |

ptime | pgroup | pinteraction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| baseline | 12 weeks | 24 weeks | baseline | 12 weeks | 24 weeks | ||||

| BFI score | 4.4±2.2 | 4.3±2.1 | 2.7±2.1 | 4.7±2.5 | 4.4±2.4 | 4.1±1.9 | <0.01 | 0.202 | <0.01 |

| KPS score | 76.5±11.3 | 75.4±10.1 | 89.3±8.3 | 74.8±14.1 | 75.9±13.0 | 75.2±11.5 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Total PSQI score | 10.5±1.5 | 5.7±1.3 | 4.1±1.1 | 10.5±2.1 | 7.7±2.0 | 6.9±2.0 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Sleep quality | 1.6±0.7 | 1.3±0.7 | 0.8±0.7 | 1.6±0.9 | 1.5±0.9 | 1.4±0.7 | <0.01 | <0.001 | <0.05 |

| Onset time | 1.6±0.8 | 1.2±0.7 | 0.9±0.8 | 1.7±0.8 | 1.4±0.8 | 1.2±0.6 | <0.01 | <0.05 | 0.494 |

| Hours of sleep | 1.7±0.7 | 0.6±0.5 | 0.4±0.5 | 1.7±0.8 | 0.8±0.6 | 0.8±0.6 | <0.01 | <0.05 | 0.069 |

| Sleep efficiency | 1.8±0.8 | 0.9±0.6 | 0.6±0.5 | 1.9±0.7 | 1.3±0.9 | 1.0±0.7 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.225 |

| Dyssomnia | 1.7±0.8 | 0.3±0.5 | 0.2±0.4 | 1.5±0.8 | 1.9±0.7 | 0.8±0.6 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Hypnotics use | 0.2±0.4 | 0.1±0.3 | 0.1±0.2 | 0.2±0.4 | 0.1±0.3 | 0.1±0.3 | 0.064 | 0.685 | 0.660 |

BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Performance Status and Sleep Quality after the Intervention

Table 3 presents the KPS and PSQI scores. The KPS scores were similar in the two groups at baseline and 12 weeks, but the KPS scores were significantly higher at 24 weeks in the exercise group compared with the routine care group (89.3 ± 8.3 vs. 75.2 ± 11.5, p < 0.01). A significant time-group interaction was also observed (p < 0.01). The PSQI scores were similar in the two groups at baseline and 12 weeks, but the PSQI scores were significantly better at 24 weeks in the exercise group compared with the routine care group (4.1 ± 1.1 vs. 6.9 ± 2.0, p < 0.01). A significant time-group interaction was also observed (p < 0.01). Among the components of the PSQI, the exercise group showed improvements in sleep quality, onset time, hours of sleep, sleep efficiency, dyssomnia, and daytime dysfunction.

Discussion

The incidence of CRF with colorectal cancer and breast cancer is higher than with other cancer types [20]. Major stressful events such as cancer diagnosis, surgery, and chemotherapy have a great impact on the patients' psychological state, making them prone to CRF. CRF is one of the most troubling symptoms displayed by cancer patients during chemotherapy, but no gold standard for the treatment of CRF has been established [1, 21]. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the effects of the Baduanjin on patients with colorectal cancer and CRF and to explore its intervention effects. Baduanjin exercise can relieve CRF in patients with colorectal cancer under chemotherapy and can improve their physical activity level and quality of sleep.

The Baduanjin is a TCM aerobic exercise. Its exercise intensity and action sequence are in accordance with kinematics and physiology. It plays an important role in enhancing immunity and eliminating fatigue [22]. A systematic review showed that the Baduanjin is beneficial for quality of life, sleep, general life balance, and physical parameters (hand grip strength, flexibility, blood pressure, and heart rate) among healthy individuals and patients with a variety of diseases [23]. A Chinese study showed that the Baduanjin could improve CRF and the quality of life of cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy [24]. The present study showed that the patients in the Baduanjin group had a reduced frequency of severe fatigue after 24 weeks of intervention. There were significant differences in CRF scores according to time and time-group interaction, but not for the inter-group comparison. This may be related to the side effects of chemotherapy at 12 weeks, which resulted in no obvious relief of mild and moderate fatigue after 12 weeks of intervention, which is in line with the findings of a study by Butt et al. [21]. The KPS and PSQI scores after the intervention were statistically significant in time, inter-group, and time-group interaction effects, indicating that Baduanjin exercise improved the patients' physical function and sleep quality.

TCM believes that CRF is a general term for chronic weakness, with a decline in function of the viscera and a deficiency in Qi and blood as the main pathogenesis, which is caused by a variety of factors including a deficiency in positive Qi and stagnation of Qi, blood, Yin, and Yang [25, 26]. Chemotherapy is harmful to the Yin and leads to the invasion of evil, leading to spleen and stomach disharmony and poor ventilation, aggravating the body's CRF. The fatigue pattern of cancer patients during chemotherapy is of the “mountain peak and valley” type [27]. Fatigue in patients with colorectal cancer increases at the beginning of each chemotherapy cycle (days 1–7) and slowly decreases on days 8–21 [28]. Therefore, according to the dynamic fluctuation of CRF, our rehabilitative therapist adjusted the Baduanjin exercise regimen accordingly during each cycle and allowed a maximum of 2 days of rest each week.

In a study on non-drug intervention for CRF, exercise therapy alleviated patient fatigue by improving muscle strength, aerobic fitness, and psychosocial function [29]. So far, studies have examined aerobic exercise, resistance training, or their combination under the guidance of professional personnel [30, 31, 32, 33]. The metabolic equivalent of the Baduanjin is <3.0 and the maximum heart rate is 54% [34]. Therefore, according to the American Sports Medicine Association (ACSM) and the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Baduanjin is a low-intensity exercise. It is believed that low-intensity exercise can expand the muscles, promote the operation of Qi and blood, and improve the state of the patient's body function. The Baduanjin can also regulate emotion and keep the body quiet and calm, reduce the production of serum-related anxiety markers, and relieve anxiety [10, 13, 14, 23]; it is also associated with improved sleep quality [11]. On the other hand, a study on patients with breast cancer showed no improvement in sleep quality [35]. Alleviating negative emotions effectively relieves physical and mental stress, improves the sleep condition, and reduces CRF. The Baduanjin is an aerobic exercise that integrates rehabilitation medicine, biomechanics, psychosomatic medicine, and meridian and collaterals. It is easy to learn, and the activity intensity is suitable for patients with chronic illnesses [10, 13, 14, 23]. There is no special material requirement. It can be carried out at home, outside, in the park, alone, or in a group, which helps adherence. This study also used the WeChat app to improve adherence. It could also be interesting to examine the effect of the Baduanjin in combination with other TCM modalities such as acupuncture [36].

This study showed positive effects in alleviating CRF and improving sleep quality, but there are still some shortcomings. First, the intervention lasted only 24 weeks, and the study of long-term effects and the effects of sustained exercise interventions need longer follow-up periods. Secondly, each component of the Baduanjin works on specific body parts, and it needs further research to study whether increasing the frequency or the intensity of a specific component could further improve CRF.

In our study, two groups of patients experienced nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy. Ear seed implantation – one method of TCM – was used to improve the symptoms of nausea and vomiting. Specifically, the treatment can be described as follows. First, select the corresponding Shenmen, stomach, cardiac, sympathetic, and subcortical ear acupoints. Second, use 0.5 × 0.5 cm special adhesive tape for the auricular acupoints to apply the disinfected vaccariae semen to the selected acupoints. Third, massage the above acupoints alternately to prevent emesis. According to TCM, the ear is the gathering place of confluence of channels; twelve meridians are connected to the ear, and all organs are connected to the ear. Stimulating ear acupoints can effectively act on the meridians of the whole body, adjust the function of the body, and alleviate adverse reactions.

In conclusion, this study strongly suggests that the Baduanjin relieves CRF in patients with colorectal cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Baduanjin exercise also improves the level of physical activity and sleep quality. This could be a convenient and simple method of alleviating CRF in patients with colorectal cancer undergoing chemotherapy.

Statement of Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kunshan Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (approval No. 201618). The study is registered with Chictr.org (#ChiCTR1800017736).

Disclosure Statement

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Y. Lu and H.-Q. Qu carried out the study, participated in data collection, and drafted the manuscript; F.-Y. Chen and X.-T. Li performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design; L. Cai, S. Chen, and Y.-Y. Sun helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the help of Hao Jiang regarding guidance on the Baduanjin for patients as a Chinese rehabilitation physiotherapist, as well as Dr. Haijun Chen for disease assessment.

References

- 1.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Cancer-Related Fatigue. Version 2. 2018 Fort Washington, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2018, pp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weis J. Cancer-related fatigue: prevalence, assessment and treatment strategies. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011 Aug;11((4)):441–6. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, Shen J, Xu Y. Symptoms and quality of life of advanced cancer patients at home: a cross-sectional study in Shanghai, China. Support Care Cancer. 2011 Jun;19((6)):789–97. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0884-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bower JE. Cancer-related fatigue—mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014 Oct;11((10)):597–609. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson LE, Waller A, Groff SL, Giese-Davis J, Bultz BD. What goes up does not always come down: patterns of distress, physical and psychosocial morbidity in people with cancer over a one year period. Psychooncology. 2013 Jan;22((1)):168–76. doi: 10.1002/pon.2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Aziz N. Altered cortisol response to psychologic stress in breast cancer survivors with persistent fatigue. Psychosom Med. 2005 Mar-Apr;67((2)):277–80. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000155666.55034.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meneses-Echávez JF, González-Jiménez E, Ramírez-Vélez R. Effects of Supervised Multimodal Exercise Interventions on Cancer-Related Fatigue: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:328636. doi: 10.1155/2015/328636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell SA, Beck SL, Hood LE, Moore K, Tanner ER. Putting evidence into practice: evidence-based interventions for fatigue during and following cancer and its treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2007 Feb;11((1)):99–113. doi: 10.1188/07.CJON.99-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zou LY, Yang L, He XL, Sun M, Xu JJ. Effects of aerobic exercise on cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2014 Jun;35((6)):5659–67. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1749-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan HS, Feng YC. Clinical observation of rehabilitation therapy with health Qigong Ba Duan Jin on grade 1 hypertension of old patients. J Nanjing Inst Phys Educ. 2010;9:4–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen MC, Liu HE, Huang HY, Chiou AF. The effect of a simple traditional exercise programme (Baduanjin exercise) on sleep quality of older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012 Mar;49((3)):265–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mei L, Chen Q, Ge L, Zheng G, Chen J. Systematic review of chinese traditional exercise baduanjin modulating the blood lipid metabolism. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:282131. doi: 10.1155/2012/282131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuei S. Beginning Qigong: Chinese Secrets for Health and Longevity. Tuttle Publishing, 1993 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang JM. Eight Simple Qigong Exercises for Health: The Eight Pieces of Brocade. Mass, Jamaica Plain, 2000 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendoza TR, Laudico AV, Wang XS, Guo H, Matsuda ML, Yosuico VD, et al. Assessment of fatigue in cancer patients and community dwellers: validation study of the Filipino version of the brief fatigue inventory. Oncology. 2010;79((1-2)):112–7. doi: 10.1159/000320607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang XS, Janjan NA, Guo H, Johnson BA, Engstrom MC, Crane CH, et al. Fatigue during preoperative chemoradiation for resectable rectal cancer. Cancer. 2001 Sep;92((6 Suppl)):1725–32. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6+<1725::aid-cncr1504>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang SS, Scott CB, Chang VT, Cogswell J, Srinivas S, Kasimis B. Prediction of survival for advanced cancer patients by recursive partitioning analysis: role of Karnofsky performance status, quality of life, and symptom distress. Cancer Invest. 2004;22((5)):678–87. doi: 10.1081/cnv-200032911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989 May;28((2)):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai PS, Wang SY, Wang MY, Su CT, Yang TT, Huang CJ, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (CPSQI) in primary insomnia and control subjects. Qual Life Res. 2005 Oct;14((8)):1943–52. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-4346-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones JM, Olson K, Catton P, Catton CN, Fleshner NE, Krzyzanowska MK, et al. Cancer-related fatigue and associated disability in post-treatment cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2016 Feb;10((1)):51–61. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0450-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butt Z, Rosenbloom SK, Abernethy AP, Beaumont JL, Paul D, Hampton D, et al. Fatigue is the most important symptom for advanced cancer patients who have had chemotherapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008 May;6((5)):448–55. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2008.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang JY, Guo H, Tang L, Meng J, Hu L. Case-control study on regular Ba Duan Jin practice for patients with chronic neck pain. Int J Nurs Sci. 2014;1((4)):360–6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zou L, SasaKi JE, Wang H, Xiao Z, Fang Q, Zhang M. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Baduanjin Qigong for Health Benefits: Randomized Controlled Trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:4548706. doi: 10.1155/2017/4548706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiu M. [Study on influence of Baduanjin exercise on cancer chemotherapy patients with cancer-related fatigue] Chin Gen Pract Nursing. 2015:2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chien TJ, Song YL, Lin CP, Hsu CH. The correlation of traditional chinese medicine deficiency syndromes, cancer related fatigue, and quality of life in breast cancer patients. J Tradit Complement Med. 2012 Jul;2((3)):204–10. doi: 10.1016/s2225-4110(16)30101-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu CH, Lee CJ, Chien TJ, Lin CP, Chen CH, Yuen MJ, et al. The Relationship between Qi Deficiency, Cancer-related Fatigue and Quality of Life in Cancer Patients. J Tradit Complement Med. 2012 Apr;2((2)):129–35. doi: 10.1016/s2225-4110(16)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vardy JL, Dhillon HM, Pond GR, Renton C, Dodd A, Zhang H, et al. Fatigue in people with localized colorectal cancer who do and do not receive chemotherapy: a longitudinal prospective study. Ann Oncol. 2016 Sep;27((9)):1761–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berger AM, Grem JL, Visovsky C, Marunda HA, Yurkovich JM. Fatigue and other variables during adjuvant chemotherapy for colon and rectal cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010 Nov;37((6)):E359–69. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.E359-E369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banzer W, Bernhörster M, Schmidt K, Niederer D, Lungwitz A, Thiel C, et al. Changes in exercise capacity, quality of life and fatigue in cancer patients during an intervention. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2014 Sep;23((5)):624–9. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou W, Wan YH, Chen Q, Qiu YR, Luo XM. Effects of Tai Chi Exercise on Cancer-Related Fatigue in Patients With Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Undergoing Chemoradiotherapy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018 Mar;55((3)):737–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pyszora A, Budzyński J, Wójcik A, Prokop A, Krajnik M. Physiotherapy programme reduces fatigue in patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care: randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2017 Sep;25((9)):2899–908. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3742-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Raaf PJ, de Klerk C, Timman R, Busschbach JJ, Oldenmenger WH, van der Rijt CC. Systematic monitoring and treatment of physical symptoms to alleviate fatigue in patients with advanced cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Feb;31((6)):716–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.4216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andersen C, Rørth M, Ejlertsen B, Stage M, Møller T, Midtgaard J, et al. The effects of a six-week supervised multimodal exercise intervention during chemotherapy on cancer-related fatigue. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013 Jun;17((3)):331–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li M, Fang Q, Li J, Zheng X, Tao J, Yan X, et al. The Effect of Chinese Traditional Exercise-Baduanjin on Physical and Psychological Well-Being of College Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS One. 2015 Jul;10((7)):e0130544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larkey LK, Roe DJ, Weihs KL, Jahnke R, Lopez AM, Rogers CE, et al. Randomized controlled trial of Qigong/Tai Chi Easy on cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Ann Behav Med. 2015 Apr;49((2)):165–76. doi: 10.1007/s12160-014-9645-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molassiotis A, Bardy J, Finnegan-John J, Mackereth P, Ryder DW, Filshie J, et al. Acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue in patients with breast cancer: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Dec;30((36)):4470–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]