Abstract

Disclosing one’s sexual orientation to family members can be a difficult process for sexual minority youth (SMY). There are many decisions to make and factors to consider, such as whom to tell first and how family members may react. SMY are in need of resources to help them through this process, including programs that help them to make decisions about safe disclosure. Through interviews and open-ended surveys with 48 participants, the authors found that overall, SMY want a program that helps them connect with others. There were no strong preferences for facilitators’ gender, and participants differed in opinions on facilitators’ sexual orientation. However, most agreed that they would like a program that provides education and the opportunity to hear from and share stories with others.

Keywords: coming out, mental health treatment, parents, youth

The decision to disclose one’s sexual orientation, more commonly known as “coming out” is often a major one for sexual minority youth (SMY). There are many factors that must be considered, particularly when coming out to family members. Although some SMY are met with acceptance and support from family, others face extreme emotional reaction, rejection, or even physical abuse (Higa et al., 2014; Puckett, Woodward, Mereish, & Pantalone, 2015). SMY often decide to come out to friends first before coming out to family members (Shilo & Savaya, 2011). Because of the prejudice, discrimination, and stigma that SMY may face, they are often at risk of mental health issues and substance abuse in addition to negative reactions from family members (Padilla, Crisp, & Rew, 2010). While some SMY do seek community resources to connect them with others and help them deal with stress (Padilla et al., 2010), more assistance is needed in order to combat the negative experiences that SMY face. Programs that are geared toward helping SMY make decisions about disclosing sexual orientation could change the ways that families handle disclosure, making it a safer and less intimidating process.

Mental Health Problems and Substance Use

SMY are at risk of mental health issues, particularly depression, in part because of the stigma, prejudice, and discrimination that they face (Liu & Mustanski, 2012; Mustanski & Liu, 2013). Padilla et al. (2010) found that SMY engage in substance use more often than their heterosexual counterparts, which was related to their higher rates of suicidal ideation. However, mothers’ positive reactions to youths’ sexual identities was a protective factor against drug use. Participation in queer youth groups helped decrease the incidence of suicidal thoughts. The authors argue that a stronger protective factor against both suicidal ideation and substance use would be parent involvement in youths’ community groups.

Some sources report that SMY are at higher risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (Liu & Mustanski, 2012; Walls, Freedenthal, & Wisneski, 2008). Savin-Williams (2001) argues that these are not “true” attempts and that the incidence of true suicide attempts among SMY is only slightly higher than the rate of their heterosexual-identified peers. The author suggests that instead, SMYs’ suicidal ideation or “false” attempts speak to the stress that SMY may face because of their sexual identities, and highlights the fact that samples from other studies are often populated with SMY who are more willing to seek social support in the first place, a limitation that Walls et al. (2008) address as well. Nonetheless, the fact that this is a common area for research demonstrates that SMY, if nothing else, must face negative societal perceptions and stigma, including the notion that they are “at risk” in one form or another.

Family Influence

Although adolescents are historically more likely to come out than they were in the past, they are less likely to disclose to family members as compared to their adult counterparts and, in comparison, report less family acceptance of their sexual orientation and more mental distress (Shilo & Savaya, 2011). Children who come out at younger ages are more likely to experience negative parental reactions (Baiocco et al., 2015; D’augelli et al., 2005). Youth are more likely to attempt suicide and are more likely to experience other negative effects such as depression if they have experienced parental rejection in regards to their sexual or gender identity (D’augelli et al., 2005; Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009).

Parents who do not react well to youth’s sexual orientation may do so for a variety of reasons. Religious views and traditional values often have an impact on how parents handle youths’ disclosure (Baiocco et al., 2015). Parents’ concerns over how others might perceive them or their children may also have an impact (Cassar & Sultana, 2016).

In a study on parental influence on gay youth’s engagement in safe or risky sexual behavior, LaSala (2007) found that youth who feel more connected to family members are more likely to practice safe sex behaviors. Those with more conflictual family histories who reported that their parents had no influence on their sexual decision-making reported engaging in some of the highest-risk behaviors. The authors hypothesize that there may be a relationship between attachment and decisions about safe sex.

Through a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature on parental influences on LGB youths’ health, Bouris et al. (2010) found that most of the research focuses on the negative impact that parents may have on LGB youth. They highlight that the literature on LGB youth most often focuses on mental health and suicidality, with less attention given to other issues like sexual behavior and substance use. The authors argue for more research on ways to support parents of SMY. The current study addresses some possible ways of providing support to parents. Additionally, programs that assist with disclosure could help SMY determine whether or not their family environment is safe. These programs could help them decide whether they should disclose, to whom they might disclose, and how they will disclose.

Social Support

SMY who come out in their adolescent and young adult years tend to seek a great deal of social support both during the initial disclosure process and afterward (Doty, Willoughby, Lindahl, & Malik, 2010). Research has shown that sexual minority adolescents who have more social support report better mental well-being (Doty et al., 2010; Walls, Kane, & Wisneski, 2010). Gay-straight alliances in schools can have a positive impact on SMY’s perceptions of safety and awareness of safe adults, even if the youths were not members of the gay-straight alliance (Walls et al., 2010). In the same study, those who were members of gay-straight alliances were found to have higher grades as well.

In addition to gay-straight alliances, SMY seek support from others for many issues, including but not limited to sexuality-related issues. While family and heterosexual friends may offer support in other areas, non-heterosexual friends have been found to be most supportive of SMY when dealing with sexuality-related issues (Doty et al., 2010). Friends’ support and acceptance has a strong impact on youth’s decision to disclose sexual orientation (Shilo & Savaya, 2011). Support is a key issue in SMY’s mental well-being and ideas about their sexual identity. This information is important to developing a program to assist with disclosure because support should be a vital aspect of such a program.

YouTube and Other Social Media

YouTube videos are popular among many youth these days, including SMY. People share videos like those from the “It Gets Better” campaign or other coming out videos and have the opportunity to hear about other SMYs’ and adults’ experiences. Videos like these may be intended to give and seek support from others (Green, Bobrowicz, & Ang, 2015) or to challenge prejudices (Muller, 2011). Lovelock (2016) criticizes the YouTube coming out video trend, stating that it ultimately furthers what Lovelock calls “proto-heteronormativity,” a transitional period and strategy between the period of youth and adolescence and a later, homonormative adult stage. Whatever the interpretation, YouTube remains a popular form of social media that draws the attention of SMY. It may be a useful medium for reaching SMY and helping them to share messages.

In a grounded theory study on SMYs’ use of information and communication technologies (ICTs), Craig, McInroy, McCready, Di Cesare, and Pettaway (2015) found that one of the main ways that SMY use these technologies is for support and connection as they develop their sexual and gender identities. They write that the “anonymity, safety and distance” (p. 165) that ICTs offer is essential for SMY because it is difficult to find them in real-world realms.

Similarly, Fox and Ralston (2016) found that SMY use social media as a means of education as well as to teach others. The ways that social media are used for education were traditional learning, in which SMY used social media to educate themselves about LGBTQ+ topics; social learning, in which SMY connected with each other as well as older sexual minority individuals from whom they could learn more; and experiential learning, in which they themselves participated in socialization processes like posting about themselves online to gain feedback or by using online dating sites. The authors note that using social media as a means for education is particularly common as SMY are first disclosing to others. Further, Ceglarek and Ward (2016) found that there is a relationship between SMYs’ use of social networking sites for sexual identity development and lower levels of paranoia, anxiety, and hostility. The ability to connect with others while developing one’s sexual identity may be a protective factor against some mental health issues.

Purpose

Pragmatic inquiry focuses on obtaining useful answers to practical questions, often using mixed methods and data triangulation to achieve its aims (Patton, 2014). Studies that utilize pragmatism as a methodological framework are often interested in actionable findings, thus making this approach a fitting one for the current research. The purpose of this study was to discover what SMY believe would be most useful in a program that assists with disclosure to family. Eventually, data from this study will be used for creating a program to assist with disclosure to family. Therefore, input from people who have direct knowledge about disclosing to family and who have insight into what would be helpful in that process is necessary.

Methods

Sample

Our sample of 48 participants comes from two larger projects on the process of disclosure to family, plus an additional web-based qualitative survey. Of the 37 participants from the interviews, 22 were LGBQ youth from the Midwestern region of the United States; 15 were from the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. Ages ranged from 14 to 22, with an average age of 19 (SD = 1.69). Seventeen participants identified as male, 19 as female, and two as transgender. Interview participants were recruited through advertising efforts with local LGBTQ+ organizations and the surrounding community. Participants under 18 years of age were also required to provide either (a) parental/guardian consent, or (b) assent with the presence of a third-party advocate if obtaining parental consent would have placed the youth at risk. Survey respondents were recruited through the primary LGBTQ+ organization at a Mid-Atlantic university as well as announcements from instructors of a general education curriculum human sexuality course. This study was approved for human subjects by the Institutional Review Board at the author’s university.

Data Collection and Analysis

Interview data come from larger semi-structured interviews that focused on the disclosure to family experience. Toward the end of these interviews, the interviewer would ask participants about what they would like to see in a program to assist with disclosing to family members. Questions were asked to assess whether participants would prefer individual or group format and what they believed were important facilitator characteristics, including sexual orientation, gender, and training. Interviewees were also asked about what activities, particularly videos and roleplays, they thought should be included in the program. The open-ended survey asked some questions that were like those in the interviews in addition to new questions to get more information. These questions included ones about what survey respondents think that SMY who want to disclose to their families should know as well as what parents should know.

We began the data analysis process while continuing to conduct interviews, finding preliminary themes that helped to inform data collection. From these preliminary themes, the first author designed the open-ended survey to get more information on what participants would like to see in a disclosure program. Interview and survey data were analyzed using thematic analysis and the constant comparative method (Boeije, 2002). Each survey and interview was initially coded on its own, and initial themes began to emerge. Codes were compared both within each individual survey and interview as well as across surveys and interviews. From there, themes across the data emerged. Eventually, the codes from the data were categorized into five main themes, each of which included several sub-themes.

Results

Overall, five main themes emerged from the data, with several sub-themes comprising them. These themes were Program Structure, Program Facilitator, Support, Education, and Sharing Stories. However, participants’ experiences, in addition to responses about the program, helped to inform the themes for study. These themes demonstrate what SMY believe would be helpful in a disclosure program as well as what they believe to be helpful in the disclosure process. Some participants discussed what was directly helpful to them when coming out. Others talked about what they wished they had had access to during the disclosure process. While participants’ answers about what they think should be included in a disclosure program are the central focus; these other areas of input help to inform the research as well.

Program Structure

Program Structure, along with Program Facilitator, were the two themes that emerged that related most directly to the questions asked in the interviews and surveys. For example, specific survey items that addressed Program Structure included, When would individual or group formats be most beneficial? and Apart from reading information, what other ways do you think information about disclosure decisions can be conveyed? (e.g., videos, games, role plays, etc.). Most participants gave input about structure that related to activities or individual and group formats because of these questions. However, some of the sub-themes that emerged within the larger Program Structure themes were unique to the participants’ perspectives rather than specifically asked about. These included information about safety, inclusivity, and ways to include parents in the program.

Group and individual formats.

Participants were asked their opinions on whether the disclosure program should have a group format or individual format. Most participants who responded to this question preferred group format (n = 14). Reasons included wanting to feel less alone and being able to hear others’ experiences, which are also discussed in the Support and Sharing Stories sections below. As one participant explained, “I feel like group is a lot better… I feel that a lot [of us] throughout the gay community, feel isolated like we’re the only ones; or in my case, in high school, I was one of three.”

Several other participants (n = 10) replied that they thought a combination of group and individual formats would be most beneficial. Participants discussed ways the program could be structured, such as a group program that provides individual mentors. A few elaborated about why both formats are beneficial. For example, an interview participant stated:

I think it would be one of those things that it’d be good to start with a group. Like, ya know have everyone talk about it, make everyone comfortable. And then break off into individual or maybe a few people sort of format. I think it would, both would be useful there. Because I think ya know talking about in groups, ya know helps remind everyone, hey there are a s---load of people in my same situation. I’m not all alone, I’m not the only kid in the whole world, ya know trying to come out to my parents or anything…And then I think talking about it individually lets you talk more about the personal issues rather than just the, ya know, the basic general one. Having someone to talk to about it individually ya know you can hash out, ya know, your own, things specific to your situation.

Another survey participant wrote, “I feel like group formats would be more helpful overall, to show people that they aren’t the only ones who are struggling. However, individual formats would be helpful to assert that each person’s struggle is important.” Two interviewees and two survey respondents also mentioned the possibility of forums if the program were to be online. This appears to be a format that would combine both individual and group formats in a way that would give program participants options. The mix between group and individual seemed to be a desirable one because more needs can be met than with either format separately.

Although the majority of participants preferred a format that at least includes a group element, not all participants were fond of the group format. Of the respondents, five stated that they believe it should be in individual format. Those who preferred an individual format gave reasons such as, “I don’t think group things work as well, ‘cause we all want like our own time with someone, and to tell our own story, so I think that’s very important to be able to like sit down with somebody.” Others discussed the fact that it can be difficult to talk about personal issues with a group, and that they might not be as honest in that type of setting.

Activities.

Most participants were specifically asked about what activities they think would work best in a disclosure program. Answers to this question varied greatly, particularly in terms of opinions about videos and roleplays.

Videos and roleplays.

A few participants stated that they had found videos, such as ones on YouTube, very helpful during their own disclosure process. They stated that hearing others’ stories in this format had helped them make decisions about coming out. However, not all participants agreed; others said that they did not find videos very useful, or that videos could be corny or out-of-date.

Results were also mixed for participants’ views of roleplays. While some thought roleplays might be helpful for people to be able to practice disclosing, others thought that they would not. One participant described that because those participating in the roleplay would not know a youth’s parents, they would not be able to portray the parents well enough for the roleplay to be useful. Similar to opinions on videos, other participants indicated that roleplays felt a little too corny. Of the interview and survey participants, 18 thought that videos would be helpful, while three interviewees specifically stated they thought videos were not helpful. Four participants thought roleplays would be useful, and four thought they would not be.

Other activities.

However, in addition to videos and roleplays, participants had other suggestions for activities that could be included in a disclosure program. Some of these were vague, like “confidence building exercises.” Others were more specific, like a suggestion for letter writing activities so that youth could prepare what they would like to say to those to whom they want to disclose. Other suggestions included performance pieces and engaging with other media like podcasts.

Including parents.

Because participants were asked about the disclosure to family process, it is unsurprising that several mentioned the possibility of including family members in a disclosure program. One sub-theme that emerged was Educating Parents, which is discussed in the Education section. Other sub-themes, however, related more to the structure of the program. This included the sub-theme Including Parents. One participant suggested that if parents and children were to attend the program together, an activity they participate in could be a role play in which the parent comes out to the child. Similarly, another participant suggested a role play where the parent and child switch places, to help them try to see things from the others’ perspective. Seeing things from each other’s perspective came up a few times when participants discussed parents’ roles. It seems that participants who believe a disclosure program should include parents want the program to emphasize understanding SMYs’ perspectives.

Safety.

Several participants discussed the need for a disclosure program to be able to provide safety for participants. Often, this came in the form of confidentiality and privacy. Participants mentioned the need for a program to be confidential or to offer privacy in some form so that youth were not accidentally outed before they had made decisions about coming out. One participant suggested that the program provide information on how to erase search histories so that parents cannot see that their children have visited the site. Another participant stated that if there were to be a physical location for such a program to be held, in this particular instance, in school, then there would need to be a safe place provided for SMY to discuss their issues. Another mentioned the need for facilitators to be prepared for the possibility of violence when youths disclose to their parents. Overall, this sub-theme seemed to speak to the need for the program to be mindful of the prejudice and discrimination SMY face and to try to offer participants some level of protection.

Inclusivity.

A final major sub-theme that emerged when participants stated what they wanted for the structure of a disclosure program was inclusivity. Participants mentioned a variety of ways that the program should be inclusive. A few spoke about being sure to include people who are transgender, genderqueer, or otherwise gender non-conforming. Two survey respondents wrote that they would want the program to be culturally sensitive, particularly because decisions about coming out may vary greatly because of the influence of one’s culture. One interviewee spoke about the importance of having many different voices, even if they are not all LGBTQ+ identified:

Ally status is fine [for facilitators]. At that point, really…I care about supporting, like as a white person who cares about intersectionality, I’d much rather…encourage black voices or like voices of color…I guess that that’d be a really good way for allies to support.

A survey respondent echoed this, stating that the characteristics they would want in facilitators are “Representation from PoC [People of Color], trans, non-binary, disabled demographics.”

Program Facilitator

Participants were asked about what they believe are important qualities in a facilitator, particularly whether the gender and sexual orientation of the facilitator mattered. They were also asked about what would be important for a facilitator to know or to do. Although answers about gender and sexual orientation of the facilitator varied, many participants offered ideas about other characteristics, knowledge, and skills a facilitator should have. The sub-themes that emerged for this category were Facilitator Orientation, Facilitator Gender, Facilitator Knowledge & Skills, and Other Facilitator Characteristics.

Facilitator orientation.

Results were almost evenly split in terms of participants’ preferences for facilitator’s sexual orientation. While many did not specify what they thought would be best, of the participants who did, 14 stated that they would prefer for a facilitator to identify within the LGBTQ+ spectrum, while 12 stated that they did not have a preference or would be okay with heterosexual facilitators. One survey respondent wrote that a straight facilitator would be better for helping a child come out to other straight people. An interviewee who did not specify a preference stated something similar, that a straight facilitator might be helpful in talking to straight parents. Another survey respondent had a different, more specific notion as to facilitator orientation and gender:

For gay males, generally we tend to be more open and comfortable with straight women. The inverse (for lesbians) is also fairly true. As for those that possess polysexual identities or gender-nonconforming identities, the lines get a tad more blurry. I’d suggest trans/polysexual identified individuals as facilitators to promote the most genuine responses.

Facilitator gender.

Fewer participants in interviews stated preferences for facilitator gender than they did for facilitator orientation. The following figure illustrates the breakdown of responses by participant gender. Because surveys were anonymous and did not include identifying information, survey respondents’ genders were not specified. Most participants (n = 6) had no preference about facilitator gender. Almost as many (n = 5) thought it would be best if the facilitator shared the same gender as the program participant. Three male participants specified a preferred facilitator gender; one preferred a male facilitator and two preferred a female facilitator. Female participants either had no preference or thought that the facilitator and program participant gender should be the same. Only three survey respondents mentioned facilitator gender, one to indicate that they had no preference, one to state that they would like to have male and female facilitators, and the other whose response, quoted in the Facilitator Orientation section, was about the intersection of facilitator orientation and gender.

Facilitator knowledge and skills.

In addition to being asked about facilitator gender and orientation, participants were asked what they thought facilitators of a disclosure program should know or do. Responses to these questions varied, but several respondents indicated that they believe some kind of training as a counselor, therapist, or other mental health professional would be helpful. A couple of others expressed distrust in many mental health professionals, and stated that this might be a barrier to their participation in a disclosure program. Many stated that they would want facilitators, whether they were LGBQ+ or allies, to have some knowledge of sexual minority experiences and communities. As one participant, addressing the question about facilitator orientation, stated:

I feel that doesn’t matter with the facilitator, um, just as long as the facilitator identifies that they are very accepting of LGBT people and our culture…maybe show that they have sort of dabbled within it. Not like sexual experiences, but like, ‘I was part of this protest of this group in my university or in high school…I have been involved with LGBT people and I don’t only say that I care, but I have shown and I have done things to show that I care’.

Along these same lines, some participants expressed a desire for facilitators who have been through similar issues. A few participants also reported that they would want facilitators to be able to initiate and maintain meaningful and open discussions.

Other facilitator characteristics.

Some participants mentioned age as an important characteristic, although what was considered ideal varied. Two participants stated that they would prefer younger facilitators, or ones that were similar in age to themselves. Another participant stated that it would be best to have both older and younger facilitators. One survey respondent believed it would be better to have “older queer facilitators.” While age seemed to be important to these participants, most did not mention it. Other characteristics participants wanted in facilitators included “kind,” “patient,” “not judgmental,” and “calm.” One participant also expressed the desire facilitators recognize that SMY should not solely be viewed as “at-risk”. Their strengths should be recognized as well. As he put it, “We’re not rainbow porcelain.”

Support

Support was a theme that came up frequently in interviews and surveys, but that manifested in different ways. Most participants discussed ways that a disclosure program should both be supportive and connect participants with forms of support. The most common sub-theme within this larger theme was that of Acceptance and Community. Participants wanted the program to help people connect with others, offering them acceptance and community in ways that they have not had before. Participants also expressed the need for the program to provide mentors for SMY and their parents. Participants also offered words of encouragement and advice to other SMY.

Acceptance and community.

Several participants stated that it would be helpful for youths to know that they are not alone. One interviewee stated, “You know for the longest time, I think everybody has that ‘[I’m the] only one’ kind of feeling and you know it’s a horrible feeling. … Sometimes people don’t have opportunities to [meet other SMY] in real life.” Others echoed this sentiment, expressing how they believed a disclosure program could help SMY by connecting them with others so that they have support throughout the process of disclosure. They discussed how important it was to be able to connect with others, particularly if they did not feel accepted by their larger communities. Another participant, in describing what has been beneficial in the disclosure process, said:

I’ll say that my friends have been and are really important in making me feel like I’m supported and that I have a community who not only accepts my sexuality, but understands well the repercussions and effects of it. And also are involved in, you know, do research and think a lot about social justice issues. So, it feels nice to me that they are actively accepting in that way. Like, they do work to educate themselves about social justice issues.

This theme connects to other themes from the data, including reasons for having a group format, planning for different situations, and the larger theme of Sharing Stories. Participants believed that helping SMY connect with other people would be an instrumental aspect of a disclosure program.

Mentors.

Participants also discussed ways that mentorship might be a helpful way to support program participants. Some discussed this theme more abstractly, highlighting the ways that close relationships with older sexual minority friends and family members had been vital to them in their own coming out processes. Others stated more directly that it would be useful for the program to provide mentors for SMY so that they have connections in the sexual minority community and have someone to talk to. One participant described how parents could also get support through other parent mentors:

Maybe…a group program where parents of gays- who like know their kids are gay and accept it- talk to other parents who are maybe going through that their kid. …I think there definitely needs to be mentoring from other people who’ve already gone through it. ‘Cause I think a lot of parents feel like it’s their fault that their kid is gay. Like they raised them so, ‘I did something wrong’. And well, no, it’s not necessarily true.

Encouragement and advice.

In addition to suggestions on how the program could support SMY, participants offered their own support in the form of encouragement or advice. “Be yourself” was advice commonly given in surveys and interviews. Participants also wanted SMY to know that just because they might face rejection from their family does not mean they are not accepted elsewhere. A couple of participants also expressed that it is not always necessary for a person to come out, and that it should be up to the individual to decide to. Other encouragement and advice offered included the fact that parents’ reactions are not the child’s fault, that every situation is different, and that “the consequences often aren’t as bad as you would think.”

Education

Participants thought that a disclosure program, particularly an online one, should assist SMY in making decisions about whether to disclose. This included providing information on how to disclose, assistance in planning for different scenarios, and other, more general information on sexual minority issues. Participants thought it was particularly important to be able to provide education for parents. One participant described why it would be important for the program to provide information, even just through discussion with others:

The group element seems like it would work well, because I feel like a lot of the issues I’ve had with my parents is that they have… if they’ve looked into anything it’s just generated more questions with them. And then, they don’t really have anyone to turn to with those questions. And I have a lot of questions as well, but I would just go on the internet and try to find the best stuff I could find; which, a lot of the time, was just people posting to some blog or forum, which wasn’t necessarily the best information.

Rather than participants and their parents seeking information elsewhere, the program could assist them in getting accurate information in addition to support from others.

Strategies and how-to’s.

Many interviewees and survey respondents wanted a disclosure program to be able to help SMY decide whether it was safe enough to disclose, and to help them decide more specifically how to disclose. One participant suggested that even before coming out to family, a program could help people figure out more about themselves first so that they are more certain of their identities. For example, exploring current definitions of different identities to see which best fits for them. One survey respondent described how a disclosure program should provide specific strategies throughout the disclosure process:

An effective program would likely provide an interactive means by which a youth could learn both how to better explain their own identity (including potential resources to explain said identity to family). A plan of each step of the ongoing coming-out process should be developed; including both positive and negative outcomes, without implying to the youth that the latter are likely to occur.

A few participants suggested providing quizzes. SMY could take these quizzes to help them determine whether their family environment was safe enough for them to be able to disclose. Other suggestions were about how to disclose once a person has decided that they want to. An interviewee suggested “teaching people communication skills and good ways to, you know, communicate about that in a way that’s gonna be positive instead of creating a situation that might be threatening.” Others shared this perspective, stating that they believe it would be important for a program to provide “tips on how to disclose”.

Planning for reactions.

Similarly, youth also wanted assistance in preparing for possible reactions from family members, especially parents. Although some participants had offered encouragement about disclosure, others also mentioned worst case scenarios, including risks of violence, getting kicked out of one’s house, and possible suicidal ideation. As one participant stated,

You should also include the worst. I mean, it happens. There are times where you get kicked out of your family. But what’s more comfortable, being you, or having that support? And sometimes you have to make that hard decision to not tell your parents until after you get out of college and everything is funded.

While most participants did not suggest necessarily delaying disclosure, they did express the need for SMY to be prepared for these scenarios. Some suggestions they had for the program to assist with these circumstances were to provide resources, which are discussed further on in this section, and to help youth come up with a plan for where they would go if they were to be kicked out of their home. Participants also wanted facilitators to be aware of the chance that parents might react angrily or violently.

Educating parents.

Although some participants wanted a disclosure program to educate SMY about sexual minority experiences and issues, more of them expressed a need for parents to receive some education. This could be in the form of mentorship, as discussed previously, but it could also come in the form of pamphlets, support groups and counseling, or some sort of programming. One participant suggested “[h]aving written material that the parents could read to educate themselves about many different aspects of sexual minority life, including things as simple as definitions and as complicated as legislative issues.” Education through the disclosure program would help take the burden of educating parents off SMY themselves.

Participants thought that education might help parents to be more accepting of their children’s disclosure. For example, one participant explained how parents may benefit from hearing from an expert during their child’s disclosure process:

A lot of time culture fills those holes in for [parents] and they have the wrong ideas. And a lot of time they won’t listen to their kids, but they will listen to things they can perceive as ya know, expert. Like, my mom won’t take me seriously; but she is used to reading papers and journals and stuff.

Several survey respondents also offered advice to parents as a way of educating them about the disclosure process and experience. Statements of advice included, “Understand that your child will be going through a lot of rough and harsh things, so please be there for them!” Several survey respondents offered similar statements of how to handle children’s disclosure in a way that is accepting and affirming. One participant shared the following advice as useful for parents,

Your kid hasn’t changed. They’ve always been this way. Now they’ve figured out who they are and how they identify. Don’t say ‘we love you anyhow.’ If you loved them beforehand then you don’t love them in spite of their being queer. You just love them. Don’t be an asshole about it.

Resources.

Finally, participants also wanted the program to provide information about resources that might be helpful to SMY and their parents. These resources included local mental health professionals and agencies, affirming churches, and useful websites and videos. They also included places where a person can find support- if they cannot find it within their family- and information about how to handle emergencies, such as the experience of violence or homelessness.

Sharing Stories

The major and most consistent theme in the data was Sharing Stories. Almost all participants mentioned that being able to hear stories from others or share stories themselves was, is, or would be useful. This topic came up so frequently that it appeared to be an overarching theme rather than a sub-theme. Overall, almost every participant mentioned how other’s stories had been meaningful to them when they were deciding to come out. One participant described the usefulness of this process:

I know I love talking about it, I know all the other people, gay people, I know love telling coming out stories. And, I think it’s really useful to hear ‘em actually. And I go to HRC meetings sometimes, and like I know a couple times we just had discussions of everybody’s coming out stories. That was always really interesting and fun. And also, it’s like a good bonding experience.

Many participants held this opinion about sharing stories being a helpful bonding experience. However, many also found these stories helpful for making decisions about coming out. Another interviewee stated:

One of the reasons that I was able to come out was meeting other people and hearing their stories…It helps a lot, ‘cause, I mean, if I feel like the community I came from was not accepting of gay people, but I know that there are others that have a much harsher attitude towards gay people…and those are the people who probably were never exposed to anyone else’s story, [then] I think definitely having that influence and inspiration from someone else- it’s priceless.

Not only did participants like to hear and share coming out stories and other personal experiences so that they could connect with other sexual minority people, they also used these stories to help inform them when making decisions about disclosure.

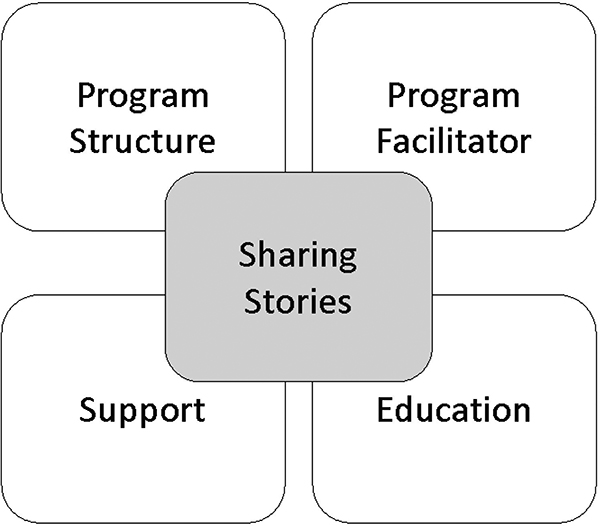

Initial analysis of the data revealed that this theme spanned the two other themes of Support and Education. However, upon further review of the data, we found that this theme intersected with all four other emerging themes. The notion that a program should connect participants to others to be able to share stories fits with the Program Structure theme because it calls for some form of interaction, often in a group format. Participants frequently mentioned that they wanted facilitators to have had similar experiences, such as the experience of coming out, or to at least have a strong understanding of these experiences. They also wanted program facilitators to be skilled in fostering discussion among participants. This draws in the Program Facilitator theme. The facilitator or facilitators would need to be able to help participants share their stories. Participants discussed how people could give and receive support through these stories, and also how the stories could be used to educate people who are making decisions about whether and how to disclose. Therefore, all four other themes connect through the Sharing Stories theme. Figure 1 illustrates how these themes intersect.

Figure 1.

Main themes. This figure shows the five main themes from the data, and how they overlap through the Sharing Stories theme.

Discussion

The findings from this study provide insight into what elements sexual minority youth would want in a program to assist in making disclosure decisions to family. Analysis of the interview and survey data revealed five primary themes that overlap. For instance, while information about participants watching YouTube videos of coming out stories falls into the theme of Program Structure, it also relates to Sharing Stories. Wanting a program to connect participants to resources falls under the category of education because it lets them know about what options they have, but it also a form of support because of the assistance it would provide them. Ultimately, while it is helpful to be able to understand the unique properties of each theme, it is also important to recognize how they intersect in order to utilize this information in designing effective programming and interventions that reflect the needs of sexual minority youth.

Many of the findings are consistent with existing literature. Similar to what Craig et al. (2015) found about SMYs’ use of information and communication technologies, participants from this study reported wanting to be able to connect with others, possibly through formats like online forums and videos. The ability to share stories through multiple platforms is essential. This also related to Fox and Ralston’s (2016) findings about SMYs’ use of social media. Participants from the current study would like for a disclosure program to offer means for both traditional and social learning by providing educational resources as well as a way to connect to others.

The emphasis on group formats, or a combination of group and individual formats, fits with previous research on the topic. While some participants might feel more comfortable with a program that offers an individual format, offering a group format could lend the social support that many sexual minority youth need during the disclosure process. Previous research has shown that organizations like gay-straight alliances may be beneficial in empowering SMY and helping prevent and reduce rates of teen depression and suicidal ideation (Russell, Muraco, Subramaniam, & Laub, 2009; Walls et al., 2008). Moreover, previous research has shown that having sexual minority friends, in particular, is beneficial to SMY who need sexuality support (Doty et al., 2010). SMY could benefit from a program that offers a sense of community to them as they navigate the disclosure process.

Participants’ desire for parents to be included in the program may provide more benefits than those explained in this research as well. Research has shown that parental acceptance helps prevent against youth stress, suicidal ideation, and substance use (Padilla et al., 2010). By providing SMY with opportunities to connect with one another, as well as opportunities to improve relationships with parents throughout the disclosure process, a program that focuses on safe disclosure decisions may help youth maintain or develop better mental well-being.

Implications

The implications of this study are related first and foremost to program development. The aim of this study was to gather formative information from SMY themselves about what they think is important to include in a program to help youth make safe and successful disclosure decisions to family. The findings provide insight into what would be helpful for structuring and staffing such a program and the general types of resources and services to provide. Participants’ input about including and educating parents through such a program demonstrate possible ways to provide more support to parents of SMY, as called for by Bouris et al. (2010).

These findings may also be useful to clinicians and other professionals working with SMY. Lucassen et al. (2013) found that SMY responded positively to computerized fantasy game designed to help combat depression using Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Clinicians could connect clients to that or similar resources in order to help clients get comfortable with online programs designed to assist SMY.

Clinicians can provide support groups for SMYs and their families. Parents’ influence, both positive and negative, has been a focus within the research on SMY and disclosure (Baiocco et al., 2015; Padilla et al., 2010; Puckett et al., 2014). Baiocco et al. (2015) found that parents in families who are less flexible and more enmeshed have more negative reactions to SMYs’ disclosure than parents in more flexible families. This is important information for clinicians to consider as they work with SMY and their families. The suggestions from participants in the current study may be useful, particularly suggestions about providing education and resources for parents. However, suggestions such as those about role playing with parents may not be well received if parents are not accepting of their SMY child’s sexual orientation or identity. Clinicians should consider each family’s situation individually to determine what will likely work for the family and what will be safest for SMY as their families process their disclosure.

Clinicians could also encourage SMY to reach out to others and find resources either in their area to connect them with others. Many of the suggestions provided by this study could be applied to SMY support networks more broadly, such as local youth centers or organizations. Above all, SMY find it necessary to be able to connect with others in order to feel supported before and during the disclosure process.

Finally, and importantly, these findings may be useful to SMY who are making decisions about disclosure. Many youths who participated in this study discussed what they found helpful to them when they were making decisions about disclosure, or what would have been helpful to them if they had adequate access. From this information, similar to the theme of sharing stories, others may be able to read what has been shared and use it to inform their own decisions.

Limitations

One participant discussed the fact that the disclosure process is ongoing; he must come out on a regular basis. Although the purpose of this research was to discover what SMY believe would be helpful to other SMY when disclosing to family, it is unlikely that these findings are fully comprehensive of everything that would be useful to SMY when coming out. Just as Sharing Stories is an important part of understanding what disclosure is like for others, every coming out story is unique and peoples’ experiences will vary. A program might not be able to deliver everything that every person wants, but it is important to get a better understanding of some of the needs that a disclosure program could meet. Informed by the formative findings of this study, including the voices of more SMY in a larger project would provide data that could be further generalized.

Future Research

There is a need for much more research on disclosure decisions if we are to develop effective programming and interventions. As mentioned above, disclosure is ongoing- to family, but also to others, such as friends, coworkers or colleagues, medical professionals, clergy, etc. Because SMY and adults may feel differently about disclosure depending on their own context, research should focus on how these decisions are made. Once more programs to assist in the disclosure process have been developed, research could focus on the success of these programs. A particular area of research could be on helping youth disclose to family and then best practices in working with families in therapeutic settings as they process disclosure. This kind of research could inform practitioners and program developers so that there is a solid foundation for evidence-based practices.

Conclusion

The disclosure-to-family process is different for every individual, but many of the feelings around the process are the same. For many SMY, there is at least some fear around disclosure because they are unsure of how their parents or other family members will react. While a program to assist in disclosing to family cannot cover all the nuances between different disclosure experiences, it is useful to know what SMY think would be most beneficial in this type of program. SMY want a program that provides both support and education to participants. They strongly believe that a program that provides interaction with others, particularly in the form of being able to hear and share stories about personal experiences, would be most beneficial.

Acknowledgments

The data for this study was partially supported by Award Number R36DA026958 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank the participants of this study for sharing their perspectives.

References

- Baiocco R, Fontanesi L, Santamaria F, Ioverno S, Marasco B, Baumgartner E, Willoughby BLB, & Laghi F (2015). Negative parental responses to coming out and family functioning in a sample of lesbian and gay young adults. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1490–1500. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-9954-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boeije H (2002). A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Quality and Quantity, 36, 391–409. doi: http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/10.1023/A:1020909529486 [Google Scholar]

- Bouris A, Guilamo-Ramos V, Pickard A, Shiu C, Loosier PS, Dittus P, Gloppen K, & Waldmiller JM (2010). A systematic review of parental influences on the health and well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Time for a new public health research and practice. Journal of Primary Prevention, 31, 273–309. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0229-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassar J, & Sultana MG (2016). Sex is a minor thing: Parents of gay sons negotiating the social influences of coming out. Sexuality & Culture, 20, 987–1002. doi: 10.1007/s12119-016-9368-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ceglarek JDP, & Ward ML (2016). A tool for help or harm? How associations between social networking use, social support, and mental health differ for sexual minority and heterosexual youth. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.07.051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craig SL, McInroy LB, McCready LT, Di Cesare DM, & Pettaway LD (2015). Connecting without fear: Clinical implications of the consumption of information and communication technologies by sexual minority youth and young adults. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43, 159–168. doi: 10.1007/s10615-014-0505-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Salter NP, Vasey JJ, Starks MT, & Sinclair KO (2005). Predicting the suicide attempts of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 35, 646–660. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.6.646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty ND, Willoughby BLB, Lindahl KM, & Malik NM (2010). Sexuality related social support among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 1134–1147. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9566-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J, & Ralston R (2016). Queer identity online: Informal learning and teaching experiences of LGBTQ individuals on social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 635–642. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green M, Bobrowicz A, & Ang CS (2015). The lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community online: Discussions of bullying and self-disclosure in YouTube videos. Behaviour & Information Technology, 34, 704–712. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2015.1012649 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higa D, Hoppe MJ, Lindhorst T, Mincer S, Beadnell B, Morrison DM, Wells EA, Todd A, & Mountz S (2014). Negative and positive factors associated with the well- being of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth. Youth & Society, 46, 663–687. doi: 10.1177/0044118X12449630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaSala MC (2007). Parental influence, gay youths, and safer sex. Health & Social Work, 32(1), 49–55. doi: 10.1093/hsw/32.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RT, & Mustanski B (2012). Suicidal ideation and self-harm in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42, 221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovelock M (2016). Is every YouTuber going to make a coming out video eventually?: YouTube celebrity video bloggers and lesbian and gay identity. Celebrity Studies, 8(1), 87–103. doi: 10.1080/19392397.2016.1214608 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucassen MFG, Hatcher S, Stasiak K, Fleming T, Shepherd M, & Merry SN (2013). The views of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth regarding computerized self-help for depression: an exploratory study. Advances in Mental Health, 12(1), 22–33. doi: 10.5172/jamh.2013.12.1.22 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muller A (2011). Virtual communities and translation into physical reality in the “It Gets Better” project. Journal of Media Practice, 12, 269–277. doi: 10.1386/jmpr.12.3.269_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, & Liu RT (2013). A longitudinal study of predictors of suicide attempts among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 437–448. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0013-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla YC, Crisp C, & Rew DL (2010). Parental acceptance and illegal drug use among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents: Results from a national survey. Social Work, 55, 265–275. doi: 10.1093/sw/55.3.265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin-Wallqvist R, & Lindblom J (2015). Coming out as gay: A phenomenological study about adolescents disclosing their homosexuality to their parents. Social Behavior and Personality, 43, 467–480. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2015.43.3.467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puckett JA, Woodward EN, Mereish EH, & Pantalone DW (2015). Parental rejection following sexual orientation disclosure: Impact on internalized homophobia, social support, and mental health. LGBT Health, 2, 265–269. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Muraco A, Subramaniam A, & Laub C (2009). Youth empowerment and high school gay-straight alliances. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 891–903. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9382-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J (2009). Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics, 123, 346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC (2001). Suicide attempts among sexual-minority youths: Population and measurement issues. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 983–991. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.69.6.983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilo G, & Savaya R (2011) Effects of family and friend support on LGB youth’s mental health and sexual orientation milestones. Family Relations, 60, 318–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walls NE, Freedenthal S, & Wisneski H (2008). Suicidal ideation and attempts among sexual minority youths receiving social services. Social Work, 53(1), 21–29. doi: 10.1093/sw/53.1.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls NE, Kane SB, & Wisneski H (2010). Gay-straight alliances and social experiences of sexual minority youth. Youth & Society, 3, 307–332. doi: 10.1177/0044118X09334957 [DOI] [Google Scholar]