Abstract

Pregnant women are highly susceptible to Plasmodium falciparum malaria, leading to substantial maternal, perinatal, and infant mortality. While malaria vaccine development has made significant progress in recent years, no trials of malaria vaccines have ever been conducted in pregnant women. In December 2016, an expert meeting was convened at NIAID, NIH, in Rockville, Maryland to deliberate on the rationale and design of malaria vaccine trials in pregnant women. The discussions highlighted the progress made over recent years in the field of maternal immunization for other infectious diseases, and the evolving regulatory and ethical environment, all of which support a new emphasis on testing malaria vaccines that offer direct benefits to pregnant women. Initial safety and immunogenicity studies of malaria vaccines will be conducted in non-pregnant adult volunteers. Subsequently, efficacy trials involving pregnant women will likely be conducted in malaria-endemic and often resource-poor environments where sufficiently high malaria incidence will allow vaccine activity to be measured. Such trials will need to meet all international standards to ensure the safety of mother and offspring, under oversight of appropriate ethical and regulatory bodies. The convened experts drafted a clinical development plan to test a malaria vaccine product during pregnancy, using as a case study PfSPZ Vaccine being developed by Sanaria Inc. that is currently in phase 2 testing. Following the expert recommendations, a pregnancy registry has been initiated in Ouelessebougou, Mali, to provide baseline information on maternal and fetal outcomes as a context for evaluating PfSPZ Vaccine safety in the future, and new regimens are being assessed that will be suitable for evaluation in pregnant women.

Keywords: Malaria, Pregnant women, Plasmodium falciparum, PfSPZ vaccine

1. Clinical, regulatory and ethical issues

Dr. Patrick Duffy (Chief, Laboratory of Malaria Immunology and Vaccinology, NIAID/NIH, Rockville, MD, USA) opened the meeting by providing a rationale for testing malaria vaccines in pregnant women, and then reviewed the leading malaria vaccine candidates currently in clinical trials.

Pregnant women and children bear the greatest burden of malaria morbidity and mortality, and therefore are the greatest beneficiaries of improved malaria control. Malaria control has been substantially strengthened in many, but not all, areas in recent years, as a consequence of increased resources and scale-up of established tools. However, malaria resurges when control efforts are scaled back, and therefore new tools for malaria elimination have received growing attention. For example, the PfSPZ Vaccine product being developed by Sanaria blocks infection which can interrupt the parasite’s life cycle, and therefore licensure is being pursued with elimination as the indication.

Despite progress, malaria remains an enormous public health problem, with an estimated 445,000 malaria-related deaths in 2016 [1]. The primary tools for malaria control—existing antimalarial drugs and anti-vector agents—address the burden in part, but applying these is cumbersome, and resistance is increasing. Even in areas where the tools retain their efficacy and are applied reasonably well, the malaria burden in pregnant women remains stubbornly high.

No malaria vaccine has ever been tested in pregnant women. However, several candidate products currently in the clinic may be considered for testing in pregnant women in the near future (see Table 1). Two rationales for testing malaria vaccines in pregnant women are to demonstrate safety and efficacy of a vaccine that protects against pregnancy malaria, and to demonstrate safety and efficacy in pregnant women who might be immunized as part of mass vaccination programs (MVPs) aimed at malaria elimination.

Table 1.

Characteristics of malaria vaccines currently in clinical development that may be considered for testing in pregnant women.

| Vaccine (type) | Status | Target | Activity | Indication | Elimination tool | Developer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RTS,S/Mosquirix (subunit) | Phase 3 complete | Sporozoite/liver stage | Prevent disease | Reduce childhood disease | Possibly in a combination vaccine | GSK |

| PfSPZ Vaccine (whole organism) | Phase 2 | Sporozoite/liver stage | Prevent infection | Elimination; travelers | Yes | Sanaria |

| VAR2CSA (subunit) | Phase 1 | Infected red cell | Control infection | Prevent placental disease | No | Various (EVI) |

| Pfs25/Pfs230 (subunit) | Phase 1 | Mosquito stages | Block transmission | Elimination | Yes | NIAID |

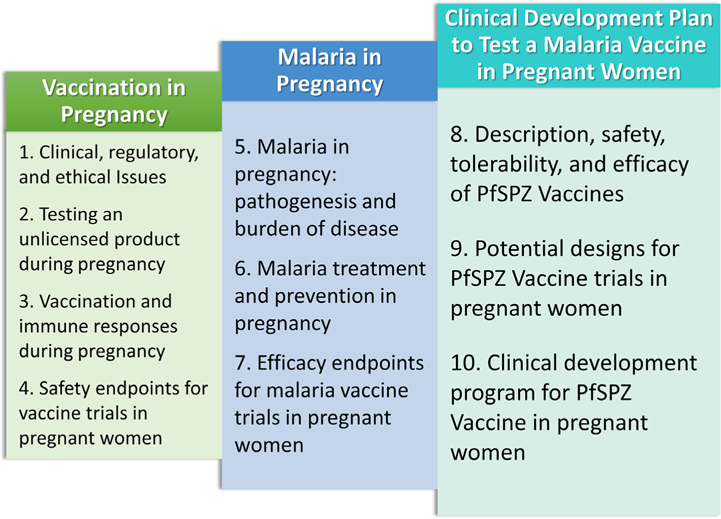

This meeting convened experts in the field to discuss malaria vaccine trials in pregnant women. Ten major subjects were discussed, encompassed under three distinct categories: (1) Vaccination in Pregnancy, (2) Malaria in Pregnancy, and (3) Clinical Development Plan to test a Malaria Vaccine in Pregnant Women (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Summary of talks included in this report.

Dr. Karin Bok (National Vaccine Program Office (NVPO), Office of Assistant Secretary for Health, Washington, D.C., USA) presented an overview of maternal vaccination and specific challenges, with an emphasis on U.S. policy, research support, and liability challenges. Two vaccines are currently recommended by the CDC to be administered during pregnancy (influenza, pertussis [Tdap]), but no licensed vaccine has a specific indication by the FDA to be used in pregnant women. In the U.S., maternal immunization studies face many challenges. Some of these include: (1) enrolling susceptible populations in clinical trials; (2) case-control studies on vaccines currently recommended for pregnant women (Flu and Tdap); (3) large cohorts that will be needed to enable study of rare adverse events such as birth defects; (4) defining the endpoint of a vaccine safety clinical trial and creating consensus across trials nationally and globally on trial endpoint; (5) liability concerns when administering vaccines recommended for pregnant women only and/or intended to protect their baby; (6) linking health records of pregnant women and infants to enable long-term follow up of infants; and (7) the safety and regulatory requirements to obtain an indication specific for pregnancy.

The Assistant Secretary for Health charged the National Vaccine Advisory Committee’s Maternal Immunization Working Group (MIWG) with identifying barriers to and opportunities for developing vaccines for pregnant women and making recommendations to overcome these barriers. The MIWG produced a report which gave advice on four key areas of maternal immunization: (1) ethical issues, (2) policy issues, (3) pre-clinical and clinical research issues, and (4) provider education and support issues. Dr. Bok outlined various U.S. agencies that have robust programs that support maternal vaccination and research on its safety. In addition, NVPO supported pilot program cooperative agreements in 2015 and 2017 to focus on research, monitoring, and outcomes definitions for vaccine safety. Under this agreement, researchers may determine the safety profile of new vaccines during the early developmental stage, or evaluate the safety profile of existing vaccines. Research conducted under this agreement should fall under one of the following objectives: improving vaccine safety, have a direct impact on the current vaccine safety monitoring systems, or help to achieve consensus definitions of vaccine safety outcomes for research conducted globally.

Dr. Bok concluded with a discussion of the 21st Century Cures Act, which has expanded the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP) to include compensation following an adverse outcome to both the woman who received a vaccine recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for routine administration in pregnant women and any child who was in utero at the time of vaccination. She discussed the special status afforded to pregnant women, who have traditionally been described as a vulnerable group for the purpose of research. This classification is now being re-examined, because pregnant women are fully competent to provide informed consent for themselves and their offspring. Finally, while trials in pregnant women require high safety standards, she emphasized that there is still no convincing evidence of adverse events related to the administration of the currently recommended vaccines for pregnant women.

Dr. Maggie Little (Director, Kennedy Institute of Ethics, Georgetown University. Washington, D.C., USA) enumerated a number of practical and ethical reasons that justify, and often mandate, the responsible inclusion of pregnant women in clinical research. These include: (1) achieving effective dosing during pregnancy, (2) reducing fetal risk related to interventions, (3) combating reticence and prioritize pregnant women for research, and (4) ensuring fair access to trials involving prospect of benefit. Conducting responsible research with pregnant women has received endorsements from governments and major international bodies. In 2015, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) stated ‘‘Although there is concern that including pregnant women in the study of new drugs potentially could cause fetal harm, it is critical to recognize that excluding pregnant women from research also can lead to harm” [2]. In 2016, WHO stated that ‘‘research with pregnant women is ethically acceptable and should be actively promoted because it is critical to providing pregnant women with safe and effective medical treatment, which is imperative for their own health and the health of their offspring” [3]. In 2016, the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) stated that ‘‘research designed to obtain knowledge relevant to the health needs of the pregnant and breastfeeding woman must be promoted” [4]. Finally, in 2016, the 21st Century Cures Act established a task force known as the Task Force on Research Specific to Pregnant Women and Lactating Women.

From an ethical perspective, the decision to include pregnant women in clinical trials involves a regulatory disjunct. Vaccines with no prospect of direct benefit may have no more than minimal risk to the fetus to justify testing during pregnancy. Conversely, vaccines with a prospect of direct benefit should have a reasonable ratio of risk to benefit in order to justify inclusion of pregnant women. The assessment of benefit to risk ratio can vary according to several factors such as background data from animals and/or non-pregnant humans that allow the benefits and risks of the vaccine and its components to be estimated, existing alternatives to treatment or prevention, and the burden of disease.

2. Testing an unlicensed product during pregnancy

Dr. Allison August (Senior Director, Clinical Development, Moderna Therapeutics, Cambridge, MA) presented an overview of progress at Novavax on a respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine designed to protect infants via maternal immunization, together with results from phase 2 clinical studies. RSV is the leading cause of hospitalizations of full-term infants, and peaks in the first 6 months of life. Infants are susceptible to severe disease due to their small airways and immature immune systems. In addition, natural immunity, derived from the mother, is relatively ineffective. With no available therapy, infants would greatly benefit from a vaccine to protect them from RSV.

Dr. August highlighted key points on the concept of vaccinating pregnant women, drawn from experience with existing vaccines:

The human placenta transmits IgG antibodies.

The young infant does not produce a rapid enough antibody titer following active immunization to address the period of highest risk.

Active immunization of the mother in the last trimester of pregnancy would potentially confer passive immunity to the neonate at the period of highest risk.

Maternal immunization has precedent for efficacy, e.g. for tetanus, diphtheria and whooping cough which protects the young infant.

Immunization during pregnancy has precedent wherein there were no observed ill effects upon the babies or mothers.

Thus, a program of active maternal immunization could address immunologic deficiencies of the infant via augmentation of available antibodies in the mother for transplacental transfer to the neonate, thus providing an immunologic advantage for the offspring [5].

The Novavax clinical development plan features a RSV purified fusion protein vaccine (RSV F) and incorporates preclinical safety and toxicology studies in rabbits and cotton rats prior to testing in humans. RSV F-induced anti-F IgG and RSV neutralizing antibodies in cotton rats and protected these rats against RSV challenge. Furthermore, protection by RSV F-induced antibodies was transferred passively to naïve cotton rats. In guinea pigs, which have human-like placental architecture, antibodies induced in the mother transferred efficiently to guinea pig pups. In other studies, infants of pregnant baboons immunized with RSV F were protected from challenge in a manner similar to infants treated with palivizumab. These preclinical studies provided the rationale to test RSV F in women of child-bearing age.

In subsequent clinical testing, the RSV F vaccine was found to be safe for both the mother and infant in a randomized, observer-blinded, placebo-controlled study of 50 pregnant women conducted at eight sites in the United States during the 2014–15 RSV season. The vaccine induced robust and durable immune responses, and effective neutralizing transplacental antibody transfer was confirmed. RSV F is poised to enter Phase 3 trials to determine the efficacy of maternal immunization against RSV lower respiratory tract infection, as well as the durability of clinical protection through 180 days of life.

Several insights from the Novavax experience have been gained that are relevant to other maternal immunization efforts. Reproductive toxicology studies were performed in two animal species and this was reassuring to clinical sites invited to participate in the studies. For maternal vaccines that will passively protect infants, vaccines given more than 30 days before delivery may yield the greatest antibody transfer to fetus. Antibody responses to RSV have been similar in pregnant and non-pregnant women, allaying concerns that immunomodulation during pregnancy could impact vaccine response. The period for monitoring infant outcomes can vary between 6 and 12 months, depending on expected vaccine effects, ideally including neurologic assessment at 6 and/or 12 months. New interventions can be compared to an existing standard of care treatment, such as the standard prophylactic immunoglobulin against RSV recommended for specific infants at risk. The Data and Safety Monitoring Board should include specialists in pediatrics, obstetrics, neonatology, maternal-fetal medicine, as well as an independent statistician who is unblinded, and monthly meetings can evaluate unblinded data for any imbalances in adverse events. Effective assessment of adverse events requires background epidemiology of pregnancy outcomes at the study site, as well as reliable gestational age dating with ultrasound. Fetal anatomic screening has been invaluable in monitoring vaccine effects during the Novavax trials.

3. Vaccination and immune responses during pregnancy

Dr. Laura Riley (Vice Chair, Obstetrics, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA) described immunologic and physiologic changes in pregnancy that may influence perinatal infections and vaccine responses and reviewed fetal development and the timing of vulnerability for infectious teratogens, therapeutics, and vaccines. To ensure the survival of themselves and their offspring, pregnant women must remain ‘‘tolerant” to the semi-allogenic fetus while at the same time being able to mount immune responses to pathogens. While pregnant women are more highly susceptible to some infections such as malaria, listeriosis, HIV, and influenza (and the severity of infection varies at different stages of pregnancy), Dr. Riley made it clear that pregnant women are not immunocompromised. Of importance for vaccine developers, any differences in vaccine antibody responses between pregnant and non-pregnant populations observed to date have probably not been clinically significant.

However, pregnancy does modulate the immune system. During the first and third trimesters, Th1 responses play a role in inflammation in the uterine cavity that accompanies implantation in the first trimester and parturition in the third, while in the second trimester Th2 responses play a role in growth of the fetus. Different immune cells take on additional ‘‘pregnancy” roles. NK cells support remodeling of decidual spiral arteries formed from trophoblasts, macrophages are responsible for migration and survival of the trophoblast, regulatory T cells maintain tolerance to the fetal allograft, and dendritic cells are critical for implantation. Immunomodulation during pregnancy may enhance activity of innate immune responses while decreasing acquired responses such as CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, with an impact on specific infectious diseases such as delayed clearance of listeria. Further, placental infection with listeria leading to production of inflammatory cytokines can activate placental destruction and preterm labor.

Thus, the complex immune status of pregnancy changes over the course of pregnancy, and this is likely related to hormonal influences on the immune system. Further, physiologic changes of pregnancy also influence both susceptibility to infection and its severity, as well as the therapeutics and vaccines used to prevent these diseases. She emphasized that many knowledge gaps remain, and that animal modeling has the potential to improve our understanding of the maternal-fetal interface and the characteristics of the placenta.

4. Safety endpoints for vaccine trials in pregnant women

Dr. Geeta Swamy (Senior Associate Dean, Regulatory Oversight & Research Initiatives in Clinical Research, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA) reviewed the approach to monitoring safety during trials in pregnant women. She first defined three key terms: an endpoint is a measurement determined by a trial objective that is evaluated in each study subject; immunogenicity is the ability to stimulate an immune response; safety is the condition of being protected from or unlikely to cause danger, risk, or injury. Vaccine development as an Investigational New Drug (IND) progresses from preclinical, to phase 1 (safety, immunogenicity, dose ranging, 20–80 subjects), phase 2 (safety, immunogenicity, hundreds of subjects), and phase 3 (safety, immunogenicity, efficacy, thousands of subjects). In vaccine trials, safety endpoints include reactogenicity such as systemic symptoms (fever, malaise, myalgia, etc), and local symptoms (pain, tenderness, induration at the injection site, etc.). Reactogenicity endpoints are usually followed for 7–30 days post-vaccination. Vaccine-related safety endpoints include Adverse Events (AEs) which are followed ~7–30 days post-vaccination, and Serious Adverse Events (SAEs) which are followed for the duration of the study.

Pregnancy-specific endpoints/events need clear definitions for pregnancy outcomes, and maternal and infant complications. Pregnancy outcomes include (1) live birth without or with congenital anomalies, (2) fetal death/still birth (loss at or after 20 weeks of gestation) without or with congenital anomalies, (3) non-induced abortion (loss before 20 weeks of gestation), or (4) elective/therapeutic termination without or with congenital anomalies. There are numerous pregnancy complications that can occur, such as gestational diabetes mellitus, gestational liver disease, gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, post-partum hemorrhage, puerperal infection, preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction or poor fetal growth, maternal death, among others. Neonatal complications include preterm birth, neonatal death, low birth weight, neonatal sepsis, and congenital anomalies, among others.

Pregnancy-specific protocol requirements will influence safety assessments. Baseline eligibility criteria, such as accurate gestational dating, and gestational timing of administration and duration of exposure to study agent, can influence the risk of adverse pregnancy events. Studies should assiduously collect ultrasound reports and results of other prenatal testing, records of maternal complications and medically-attended events, and pregnancy outcomes like gestational age at delivery, delivery complications, condition of the neonate, and complications in the neonatal period. In assessing AEs/SAEs, it is important to understand the background rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes, each participant’s baseline risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes (consider pregnancy history, as prior pregnancy events can increase risk), as well as the biologic plausibility and etiology of AEs/SAEs. It is imperative to involve experienced obstetric providers in the conduct of clinical trials in pregnancy and AE/SAE assessment. First trimester exposure is of particular concern for embryotoxicity and teratogenesis, but accessing women for enrollment during this window of gestation can be difficult.

Maternal or fetal death is a SAE and key for deciding whether safety concerns merit pausing or halting a study. Because the control group may be too small to define outcome rates, knowledge of pregnancy outcomes in the community prior to trial initiation is essential to assess whether an investigational product may be increasing the incidence of such events. Outcomes and AE/SAE data should be collected in a standardized fashion, and care taken to avoid misclassifications, particularly as outcomes may vary by gestational age. Over recent years, the GAIA collaboration (Global Alignment of Immunization Safety Assessments in Pregnant Women) has been developing consensus case definitions for trials during pregnancy. A key principle is to ensure the proper balance of research and attention to prenatal care to ensure a high standard of care is achieved for the trial participants.

Dr. Blair J. Wylie (Director Maternal-fetal Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA) Dr. lair Wylie briefly discussed the importance of investment in the measurement of obstetric outcomes (birth weight, gestational age) in vaccine trials involving pregnant women. For birth weight, standard platform scales are accurate only to ±100 g, whereas digital scales are more precise (±2 g). Thus, the type of scale used will impact the estimate of the low birth weight prevalence observed in a given population and the sample size required to discern differences between groups (vaccinated versus not vaccinated). In addition to scale precision, other considerations in field-based research for birthweight endpoints include scale calibration, breaking of electronic scales in field settings, and the timing of birth weight measurement, which can decrease as much as 10% by day 3.

Similarly, misclassification in gestational age, and consequently preterm birth rates, can occur depending on the accuracy of the gestational age assessment tool used (e.g., menstrual dating, early pregnancy ultrasound, late pregnancy ultrasound, postnatal measures). Dr. Wylie presented data from a modeling exercise that demonstrated a doubling of the measured preterm birth rate with less accurate gestational age assessment methods (±3 or 4 weeks) compared to methods accurate to ± two weeks such as early pregnancy ultrasound. For vaccine trials involving pregnant women, it is critical to apply the same methods for obstetric outcomes in both the vaccinated population as well as the comparison group.

5. Malaria in pregnancy: Pathogenesis and burden of disease

Dr. Michal Fried, Chief, Molecular Pathogenesis & Biomarkers Section, Laboratory of Malaria Immunology and Vaccinology, NIAID/NIH, Rockville, MD, USA described the epidemiology of Plasmodium falciparum malaria as it relates to pregnancy. In the general population, the incidence of malaria peaks in early childhood and declines thereafter, at a rate that varies with malaria transmission; in general, adults enjoy semi-immunity that limits parasitemia and controls symptoms. However, malaria susceptibility increases again during first pregnancies, and then declines with each subsequent pregnancy, unless the woman is immunosuppressed as in HIV infection.

Placental sequestration of infected erythrocytes is a histologic hallmark of P. falciparum malaria. Parasites that infect pregnant women with malaria have a distinct binding phenotype; infected erythrocytes bind primarily to chondroitin sulfate A (CSA) in pregnant women, whereas parasites from non-pregnant infections bind to other receptors such as CD36. In addition, there is a higher parasite burden in the placenta of primigravidae compared to multigravidae. This can be explained by the acquisition of specific anti-adhesion antibodies that occurs with each subsequent pregnancy. The presence of these anti-adhesion antibodies has been associated with a 400 g increase in birthweight among secundigravid pregnancies in an area of high malaria transmission [6]. Thus, pregnant women experience gravidity-dependent susceptibility to pregnancy malaria.

Pregnancy malaria is often a silent, sub-patent disease that is difficult to diagnose, and as a consequence can be carried as a chronic infection throughout pregnancy. Pregnancy malaria is associated with many adverse outcomes, including low birthweight, fetal growth restriction, preeclampsia, preterm delivery, miscarriage, stillbirth, neonatal death, maternal anemia and maternal death. Even in the presence of preventative measures such as intermittent presumptive treatment (IPTp), pregnancy malaria still occurs at a high rate as many women develop malaria before their first IPTp dose, which is only administered from the second trimester. Thus, a vaccine to reduce pregnancy malaria is urgently needed to improve pregnancy outcomes, and to have maximum benefit it should be delivered before first pregnancies.

6. Malaria treatment and prevention in pregnancy

Dr. Clara Menendez, Director, Maternal, Child, and Reproductive Health Initiative, Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), Barcelona, Spain reviewed current treatment practices and priorities for research. Approximately 125 million women become pregnant in malaria-endemic areas worldwide each year. These infections are often symptomatic and may be severe. Current control measures against pregnancy malaria are centered around drugs (for prophylaxis and treatment) and vector control (e.g. insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), insect repellents). In stable transmission areas, the WHO recommends IPTp with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) along with case management and the use of ITNs. IPTp involves the administration of treatment doses of an antimalarial at predefined intervals, irrespective of the presence of parasites. SP is useful for IPTp due to its good safety profile, long-acting half-life (4–7 weeks), and high cost-effectiveness. The use of IPTp-SP has led to significant reductions in peripheral parasitemia at delivery, active placental infection, fetal anemia, clinical malaria episodes during pregnancy, and most notably, neonatal mortality. However, IPTp use could be improved as an estimated 44% of pregnant women in Sub-Saharan Africa did not receive a single dose of IPTp in 2016, according to the World Malaria Report of 2017 [1]. Up to 200,000 neonatal deaths could have been prevented between 2009 and 2012 if the use of IPTp and ITNs reached the target of 80% coverage. It is also concerning that there is no clear successor to SP for IPTp, especially as parasite resistance is increasing; no alternative drugs in the current pipeline match SP in terms of safety, durability, and single-dose use.

Prevention and treatment of malaria in HIV+ pregnant women is even more complicated as these women are more susceptible to malaria, with a higher risk of infection and severe disease. To achieve the same impact in reduction of malaria-related poor pregnancy outcomes, HIV-infected women need more SP doses [7,8]. Currently, daily cotrimoxazole prophylaxis (CTXp) is used in HIV-infected pregnant women, but SP is not recommended in women receiving CTXp due to potential serious adverse effects with their concomitant administration. In contexts of low/unstable malaria transmission, such as in Latin America and in some regions in Asia, approaches to prevention of malaria in pregnancy are centered around screening and treatment of infection. However, a high proportion of infections go undetected with current diagnostic tests (e.g. rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) and microscopy).

Mass drug administration (MDA) is being considered for malaria elimination, with the objective to treat as large a proportion of the population as possible to cure any asymptomatic infections and to prevent reinfection during the period of post-treatment prophylaxis. MDA has been attempted in the past, using quinine in Italy in the early 1900s, or chloroquine in Sub-Saharan Africa in the 1960s and 70s. Several ethical principles apply to MDA: (1) MDA must not harm any subjects; there may not be direct benefit for the individual but it cannot harm the individual, (2) MDA must ensure that vulnerable subjects are protected, and (3) individual autonomy must be respected and subjects need to be fully informed in their decision to receive MDA, especially in the case of adolescents.

The main issues regarding pregnant women and women of child-bearing potential in a malaria elimination context are (1) safety and (2) reduced effectiveness of intervention, since infection may not be identified in pregnant women harboring parasites in the placenta with current diagnostic tests, and radical cure might not be possible because they cannot take primaquine. Regarding safety, pregnant women are the most susceptible and vulnerable group among malaria patients, with risks posed to themselves and the unborn child. Furthermore, there is a low benefit-risk ratio if drugs with safety concerns are given to asymptomatic or uninfected pregnant women. Regarding the reduced effectiveness of intervention, pregnant women can serve as parasite reservoirs for transmission, and asymptomatic placental infections continue to go undetected by current RDTs. Of the many challenges of malaria treatment of pregnant women, the most urgent is to increase the coverage of existing life-saving interventions.

7. Efficacy endpoints for malaria vaccine trials in pregnant women

Dr. Atis Muehlenbachs, Pathologist, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA and Michal Fried focused on defining the efficacy endpoints to consider when designing a pregnancy malaria vaccine trial. When the goal is to prevent infection, the primary endpoints are placental and peripheral parasitemia. The secondary endpoints are low birthweight, preterm delivery, miscarriage, stillbirth, neonatal death, and severe maternal anemia. Several platforms exist to detect pregnancy parasites, including microscopy, rapid diagnostic tests (RDT), molecular tools (PCR), and Loop Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP). Maternal blood can be tested antenatally or at delivery, placental blood can be tested by impression, mechanical extraction, and incision, and placental histopathology can also be used to detect parasites. Malaria pigment detected in placentas in the absence of parasites indicates past infections that have resolved.

Diagnostics for malaria that utilize a peripheral blood sample have lower performance in pregnant women, due to sequestered parasite biomass in the placenta (which limits total body parasite burden sampled in peripheral blood), and increased plasma volume resulting in a physiological 20% hemodilution. Thus, parasite diagnostics are more sensitive when used on placental blood compared to peripheral blood. While recent trials suggest that current RDTs are not sensitive enough to detect clinically significant placental parasites, new RDTs have increased sensitivity and specificity, but need to be demonstrated as a better test for pregnancy malaria. PCR diagnosis requires infrastructure, reagents, trained staff, and careful controls, but detects more positives than peripheral blood microscopy. In a formal evaluation of microscopy, RDT, and PCR, it was found that test performance varies by transmission intensity.

Placental histology has high utility for clinical trials, as pathologic findings are closely associated with clinical birth outcomes, and can document past infections, up to 6 months prior to delivery. However, a major concern for histology is the detection of false positives, especially of malaria pigment; these errors can reduce the power of clinical, epidemiological, and pathogenesis studies, but can be limited by formal external quality assurance.

8. Description, safety, tolerability, and efficacy of PfSPZ Vaccine

Dr. Stephen L. Hoffman (Chief Executive and Scientific Officer, Sanaria, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) presented a brief introduction to PfSPZ Vaccine developed by Sanaria, Inc. PfSPZ Vaccine prevents parasites from leaving the liver, thus preventing blood stage infection, and hence malaria disease and transmission. PfSPZ Vaccine is comprised of aseptic, metabolically active, nonreplicating, purified, cryopreserved P. falciparum sporozoites that meet regulatory requirements and are suitable for parenteral inoculation. Direct venous inoculation (DVI) of PfSPZ Vaccine has been shown to induce sterile immunity, and PfSPZ Vaccine efficacy has been shown to increase with increasing doses. In multiple double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, there have been no differences in adverse events between vaccinees and controls who received normal saline.

Dr. Thomas Richie (Chief Medical Officer, Sanaria, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) outlined a four-stage clinical developmental plan for PfSPZ Vaccine starting with safety and efficacy studies demonstrating proof-of-concept performed in 2013–2015 as stage 1, continuing with safety and efficacy studies to optimize dosing regimens and expansion to pediatric populations performed in 2016–18 as stage 2, followed by pivotal phase 3 clinical trials to support licensure scheduled for 2019–20 as stage 3, and finally large scale elimination campaigns post-licensure as stage 4. Stage 1 clinical trials conducted so far have featured 371 total volunteers from the USA, Mali, Tanzania, and Equatorial Guinea. These studies demonstrated that PfSPZ Vaccine is extremely well-tolerated, with no differences between vaccinees and controls in the frequency of AEs. Importantly, when efficacy was measured by controlled human malaria infection (CHMI), the vaccine achieved short-term homologous protection (87–100%) and short-term heterologous protection (80%), with lower levels of long-term protection against CHMI and natural exposure in Mali for up to 14 and 6 months respectively.

Stage 2 studies are ongoing and feature age de-escalation experiments, optimization, and bridging studies involving approximately 1200 volunteers in several countries. By the end of 2018, Sanaria plans to have a finalized 3-dose regimen that meets requirements for non-immune adults and infants in Africa. This will be followed by pivotal phase 3 trials in approximately 1100 non-immune adult subjects for efficacy against CHMI and safety, with continued assessment in the developing world for all age groups. Stage 4 studies of PfSPZ Vaccine will test mass vaccination programs (MVPs) to achieve elimination of P. falciparum; toward this end, Bioko Island of Equatorial Guinea is being assessed as a possible site.

Preclinical studies have not suggested any safety concerns. Toxicology studies performed in rabbits were unremarkable. Distribution studies of PfSPZ administered IV to mice found no PfSPZ in locations other than liver. No breakthrough of PfSPZ Vaccine has been documented in humans to date.

No ReproTox studies have been performed yet to assess preclinical safety and immunogenicity in pregnant animals. The consensus of experts in attendance recommended ReproTox studies, which might include guinea pigs which have placental physiology similar to humans. These studies should include inoculation at different stages of pregnancy and investigate whether PfSPZ can cross the placenta. After mosquito bite, sporozoites circulate in blood no longer than 30–60 min; any interaction with the placenta would need to occur during this period. The possibility of liver damage may increase with pregnancy related conditions (e.g., preeclampsia) and therefore should be considered.

9. Potential designs for PfSPZ Vaccine trials in pregnant women

Dr. Ogobara Doumbo, Director, Malaria Research and Training Center, Universite de Bamako, Mali, Bamako, Mali began his presentation by stating that current malaria prevention strategies, such as chemoprevention or insecticide-treated nets, are insufficient for elimination; vaccines will be needed to fully eliminate malaria. Regarding the use of PfSPZ Vaccine in elimination campaigns, this will only be possible if pregnant women can also be vaccinated. Toward this end, clinical and regulatory pathways to demonstrate safety in women of childbearing age and pregnant women are needed, and success will hinge on more education and dialogue amongst researchers, regulators, health ministers, and populations.

Dr. Doumbo proposed three approaches to vaccination: (1) immunize women of child-bearing age before pregnancy and follow through pregnancy, (2) immunize women of child-bearing age before pregnancy and boost during 1st or 2nd trimester, or (3) immunize women during pregnancy starting at 1st antenatal visit. In each of these approaches, data collection can be linked to antenatal visits. When designing trials for pregnant women, some special issues to consider include: (1) national policy on the age of consent for adolescents, (2) background rates of pregnancy outcomes, as the community may attribute pregnancy outcomes to the vaccine, and (3) one adverse outcome in a small community may have a substantial impact. Flu vaccine has already been tested on Malian pregnant women, and can provide a model for future malaria vaccine trials in resource-poor settings.

Dr. Sara Healy, Clinical Trials Director, Laboratory of Malaria Immunology and Vaccinology, NIAID/NIH, Rockville, MD, USA introduced her discussion on protocol considerations for PfSPZ Vaccine trials by highlighting the question of the indication of the vaccine. This includes (1) prevention of infection during pregnancy, (2) elimination of malaria in the community through interruption of transmission, and (3) prevention + elimination. For the indication of prevention, the goal is to prevent poor pregnancy and neonatal outcomes, and thus safety and protective efficacy are needed. A preventive vaccine may be licensed for a particular timeframe before or during pregnancy, and additional studies may be needed to explore the duration of protection, impact on subsequent pregnancies, potential need for boosters with subsequent pregnancies, impact on malaria infection in the infant, impact on overall health of the infant, and impact of maternal vaccination on infant vaccine responses.

For the indication of elimination, the goal is to license PfSPZ Vaccine for all individuals including pregnant women. For this indication, safety is the primary determinant, as the vaccine must be safe enough to give in mass immunization campaigns. Safety data would be needed for all trimesters of pregnancy, and data should be generated to demonstrate that pregnant women are a reservoir for the malaria parasite. In addition, towards the goal of elimination, the case should made that a certain percentage of herd immunity must be achieved. The target indication of the vaccine and determined endpoints will inform the study design and sample size; for example, 1000 pregnant women may be required to demonstrate that the vaccine is safe. Defining the study site and site capabilities is crucial; only malaria-endemic sites should be considered, and gestational age dating and obstetric expertise are needed. Various enrollment criteria must be considered and determined: what age range will the study include? Will the vaccine be tested in nulligravida, secundigravida, or multigravida? What trimester will be enrolled? There must also be exclusion criteria and screening procedures to ensure that Phase 1 and 2 study participants are as healthy as possible.

Before the study begins, background pregnancy outcome rates should be characterized; background rates of miscarriages, stillbirths, pregnancy complications, fevers, and acute illnesses will inform halting rules when the clinical trial is in progress. Dr. Healy proposed a stepwise approach to studies in pregnant women over a 5-year period, including an initial background study of the population, safety and immunogenicity studies in nulligravid women, randomized (based on pregnancy status) studies to explore vaccination during pregnancy in all trimesters, and studies to evaluate the effects of boosting. Study designs are staggered with initial studies dedicated to generating safety data, then efficacy the following year(s) with appropriate sample sizes.

10. Clinical development program for PfSPZ Vaccine in pregnant women

Dr. Thomas Richie outlined three objectives relating to vaccination of pregnant women with PfSPZ: (1) protecting pregnant women resident in endemic areas from malaria, (2) immunizing pregnant women as part of mass campaigns to eliminate malaria, and (3) protecting pregnant travelers and expatriates. To protect pregnant women, Sanaria will immunize girls prior to reproductive age and boost during future pregnancies, and will also immunize newly pregnant women with a complete regimen if not previously done. For mass vaccination programs, Sanaria will immunize all individuals aged 5 months to 65 years, striving for the highest possible population coverage.

In immunizing pregnant women, the primary objective is to achieve safety for the mother and the infant in all three trimesters, while the secondary objective is to achieve efficacy while administering the vaccine to women during antenatal visits. Sanaria has already achieved vaccine efficacy against homologous parasites greater than 85% following three doses of PfSPZ Vaccine in several studies (both in malaria-naïve and malaria-exposed adults) and is exploring accelerated regimens. Accelerated regimens could induce protection earlier in pregnancy, and this longer window of protection would likely result in improved pregnancy outcomes over the control group.

Sanaria proposes to initiate testing in pregnant women using a dosing regimen shown to be efficacious in studies of non-pregnant adults rather than adopting a dose escalation design; this is because of the ethical requirement for an expected benefit, while measuring as many safety outcomes as possible. Such a trial would be conducted at the site of an existing pregnancy registry that provides baseline rates for poor pregnancy outcomes. Placental and cord blood samples will be studied with sensitive tools to detect sporozoites.

Dr. Brian Greenwood, Professor of Clinical Tropical Medicine, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK offered additional points for consideration at the conclusion of the meeting. For clinical trials taking place in countries without a national compensation scheme, the issue of adverse events possibly related to the vaccine may require special insurance arrangements. A vaccine that prevents malaria will have less stringent safety requirements than one solely used for elimination. A large number of women may need to be vaccinated before it could be reasonably assumed that the product was safe. A combined poor outcome of the pregnancy, for example inclusion of premature delivery, low birth weight and stillbirth, as the primary trial endpoint has the advantage of reducing sample size but may result in some loss of important information.

11. Post-meeting actions

Prior to initiating vaccine trials in pregnant women, baseline data on maternal and fetal outcomes at the testing site are needed. These data provide a context to understand vaccine safety, for example whether pregnancy losses or congenital abnormalities are occurring at the expected rate in the community or whether such events represent a deviation from baseline in their frequency or presentation. Following the expert meeting, scientists at the Malaria Research and Training Centre (MRTC), Mali, and at the Laboratory of Malaria Immunology and Vaccinology (LMIV), NIAID, launched a pregnancy registry at a study site in Ouelessebougou, Mali that will host future vaccine trials in pregnant women. The registry incorporates a demographic surveillance system that monitors women in their reproductive years to identify new pregnancies as they arise. Women whose verbal report suggests that they may be pregnant are offered a pregnancy test, and when positive, a sonogram by trained staff to determine a gestational age. The registry was started in February 2017, and as of March 2018 had enrolled over 1600 pregnant women, and captured information on nearly 1000 pregnancy outcomes.

Vaccine regimens must be suitable for the target population. In Africa, which disproportionately accounts for the global burden of P. falciparum malaria, women often do not present for their first antenatal visit before 20 weeks of gestation. Therefore, the existing proven regimen which administers PfSPZ Vaccine at 0, 2, and 4 months [9] would not offer protection for women until the end of a 9-month pregnancy. Alternative regimens should be assessed, for example accelerated schedules (a 0, 7, and 28 day regimen has shown 100% short term homologous protection in recent studies), pre-conception primary vaccine series with boosting during pregnancy, or seasonal vaccination in areas where malaria transmission occurs within a limited and predictable time window annually. In anticipation of assessing PfSPZ Vaccine efficacy in pregnant women, MRTC and LMIV launched a trial in men and non-pregnant women in 2018 to assess the efficacy of accelerated vaccine schedules and of repeated annual booster doses.

12. Concluding points

Overall, attendees at the expert meeting strongly advocated for trials of malaria vaccines in pregnant women when a benefit was likely. Malaria takes a heavy maternal and perinatal toll, and existing tools provide only partial protection. Women and their babies might derive substantial health benefits from an effective, safe malaria vaccine. Malaria vaccines are advancing in development, and the risk to pregnant women is minimized when safety can be demonstrated in carefully controlled and observed trials, rather than in the course of incidental exposures after a product is licensed. Trials in pregnant women have special requirements, such as preclinical toxicology studies in pregnant animals to assess preclinical safety and immunogenicity, knowledge of background rates of pregnancy complications at the trial site, gestational dating by ultrasonography, appropriate vaccine schedules, and pregnancy-specific endpoints for safety and efficacy. The outstanding safety profile and evidence for protective efficacy of PfSPZ Vaccine warrant further consideration for trials in pregnant women, and therefore preparations for such trials should be prioritized.

Acknowledgments

The Expert Meeting received support for participant travel from Noble Energy, Inc. as part of its Corporate and Social Responsibility Program. J. Patrick Gorres contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. Sara A. Healy, Michal Fried, and Patrick E. Duffy are supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that Sanaria is a for profit company that holds relevant IP and is developing PfSPZ Vaccine as a potential product.

References

- [1].WHO. World Malaria Report In: Organizaiton WH, editor. Geneva; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [2].ACOG. Ethical considerations for including women as research participants www.acog.org: American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [3].WHO. Zika ethics consultation: ethics guidance on key issues raised by the outbreak irs.paho.org: WHO; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [4].CIOMS. New CIOMS guidelines on research with pregnant and breastfeeding women UMC Utrect Julius Center; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cohen P, Scadron SJ. The effects of active immunization of the mother upon the offspring. J Pediatr 1946;29:609–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Duffy PE, Fried M. Antibodies that inhibit Plasmodium falciparum adhesion to chondroitin sulfate A are associated with increased birth weight and the gestational age of newborns. Infect Immun 2003;71:6620–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Filler SJ, Kazembe P, Thigpen M, Macheso A, Parise ME, Newman RD, et al. Randomized trial of 2-dose versus monthly sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in HIV-positive and HIV-negative pregnant women in Malawi. J Infect Dis 2006;194:286–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Parise ME, Ayisi JG, Nahlen BL, Schultz LJ, Roberts JM, Misore A, et al. Efficacy of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for prevention of placental malaria in an area of Kenya with a high prevalence of malaria and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998;59:813–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sissoko MS, Healy SA, Katile A, Omaswa F, Zaidi I, Gabriel EE, et al. Safety and efficacy of PfSPZ Vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum via direct venous inoculation in healthy malaria-exposed adults in Mali: a randomised, double-blind phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17:498–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]