Abstract

A meta-analysis was conducted to examine gender differences in the effects of early childhood education programs on children's cognitive, academic, behavioral, and adult outcomes. Significant and roughly equal impacts for boys and girls on cognitive and achievement measures were found, although there were no significant effects for either gender on child behavior and adult outcomes such as employment and educational attainment. Boys benefited significantly more from these programs than girls on other school outcomes such as grade retention and special education classification. We also examined important indicators of program quality that could be associated with differential effects by gender.

Keywords: Early childhood education, meta-analysis, gender, school achievement

For decades, scholars, policymakers, and advocates have touted the potential of early childhood education (ECE) to remediate disadvantaged children's low levels of achievement at school entry, and have more recently argued that these programs benefit more affluent children as well (Barnett, 1995; Kirp, 2009). Over time, as public and private funding for these programs expanded, children's participation has risen, and now more than half of children experience ECE before entering kindergarten (Magnuson & Shager, 2010). With increased participation has come greater scrutiny of program effectiveness, and more attention to whether the benefits of ECE programs are broadly distributed or whether they are concentrated among some subgroups of children. Understanding whether program impacts differ by child characteristics is especially important for policymakers and educators who generally share the goal of designing programs and policies that improve the school success of all children.

Numerous studies and meta-analyses now suggest that ECE has meaningful short-term effects on children's early academic skills that vary from small to large across program evaluations, but fewer consistent positive impacts on children's behavior or self-regulation (Burchinal, Magnuson, Powell, & Hong, 2015; Cammilli, Vargas, Ryan, & Barnett, 2010 ). Although ECE evaluation studies have often considered heterogeneous effects by race, ethnicity and low-income status (Currie & Thomas, 1999; Duncan & Sojourner, 2013; Garces, Thomas, & Currie, 2002), little systematic attention has been given to whether program impacts differ by gender.

Gender differences in program effectiveness are sometimes are reported in some articles, but such differences have rarely been the primary focus of analysis. A notable exception is a reanalysis of three prominent experimental ECE studies (Perry Preschool, Abecedarian, and the Early Training Project) by Anderson (2008), which had a provocative conclusion. Although female participants gained substantially from the programs, “the overall patterns of male coefficients is consistent with the hypothesis of minimal effects at best--significant (unadjusted) effects go in both directions and appear at a frequency that would be expected due simply to chance” (Anderson, 2008, p. 1494). Several more recent ECE studies of Head Start and the Chicago Parent-Child Centers, however, arrive at the opposite conclusion and find that boys benefit more than girls (Deming, 2009; Ou & Reynolds, 2010).

Gender differences in educational outcomes have received considerably more attention in the later school years than the preschool years. Girls consistently outperform boys on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reading tests and have higher levels of educational attainment, including college completion, in the general population and among low income samples (Aud et al., 2010). The gender gaps in academic outcomes have multiple determinants, but it is important to better understand the role that early education may have in shaping such gender differences. If girls do have better outcomes from early educational investments than boys, then it might provide some insight as to why girls outperform boys in the later years. Moreover, this would suggest that efforts to improve the school readiness of vulnerable children should be carefully examined to better meet boys' needs.

This study uses meta-analytic methods to investigate whether there are differential program impacts of ECE for boys and girls across a broad set of ECE programs in four domains: cognitive skills and achievement, behavior and mental health, other school related outcomes, and adult outcomes. In addition, we explore whether program features may explain any differences in ECE impacts by gender.

Background

In order to understand why gender may affect the extent to which children benefit from ECE, it is important to consider what is known about how about typical development in early childhood differs by gender. Specifically, gender differences in early skills and behaviors are theoretically important for thinking about how ECE may affect boys and girls differently. We discuss these gender differences in development and their application to ECE contexts before reviewing the empirical studies of gender differences in ECE program impacts. Finally, we discuss the possibility that differences across ECE program designs (or evaluation study designs) may be important to understanding whether a program has different effects on boys or girls.

Normative Early Development and Gender

If boys and girls typically enter early childhood with different levels of cognitive and behavioral skills, then the learning supports provided by ECE experiences may have differing effects on their learning. Normative gender differences in skill levels and behavior may stem from both biological processes, such as the effects of prenatal exposure to testosterone, and social processes, such as differential patterns of peer and parental socialization by gender (Busey & Bandura, 1999; Maccoby, 1990; Rose & Rudolph, 2006; Zahn-Waxler, Shirtcliff, & Marceau, 2008). In early childhood, boys are described as being less developmentally advanced than girls in several domains (Crockenberg, 2003; Zaslow & Hayes, 1986). Getting a handle on the exact magnitude of these skill gaps is difficult, as often in the process of designing a performance test items are chosen that tend minimize group differences (Ackerman, 2006). This may be why greater differences are found in some school outcomes such as grades and high school completion compared with standardized achievement assessments.

In the cognitive and achievement domain, by the time of school entry, performance on standardized assessment show that girls have greater pre-reading skills, but not pre-math skills (Duncan & Magnuson, 2011). Recent summaries of the large literature on gender differences in language conclude that girls tend to have faster vocabulary growth and demonstrate better language outcomes relative to boys across a range of types of measures in early childhood (Bornstein, Hahn, & Haynes, 2004; Erikkson et al., 2012; Huttenlocher, Haight, Bryk, Seltzer, & Lyons,, 1991). Despite these potentially important differences, boys and girls are more similar than different with respect to their learning capacities and cognitive capabilities (Spelke, 2005). A review of 46 meta-analyses by Hyde (2005) concluded that 78% of gender differences across all ages on a wide range of domains have effect size differences smaller than 0.35, relatively small according to convention, with many of the larger gender differences found in the motor performance domain.

Young girls also have what is often described as an advantage relative to boys in terms of some aspects of temperament and socioemotional development. A meta-analysis by Else-Quest and colleagues (2006) showed that girls outperform boys on measures of effortful control (attention regulation, inhibitory control, and perceptual sensitivity), and boys have slightly higher levels of surgency (sociability, activity, and positive affect) across the early childhood years (Else-Quest, Hyde, Goldsmith, & Van Hulle, 2006). Boys also demonstrate higher levels of physical and direct aggression than girls (Card, Stucky, Sawalani, & Little, 2008; Matthews, Ponitz, & Morrison, 2009). The differences in behavior and self-regulation have implications for peer group interactions, with a lengthy research literature suggesting that gender segregation begins in early childhood and that boys' peer interactions are characterized by relatively more activity, competition, hierarchy, and aggression, whereas girls tend toward to be somewhat more concerned with social cohesion, although girls' advantage in peer and prosocial behavior is more pronounced in middle childhood than early childhood (Rose & Rudolph, 2006).

Gender and the ECE Classroom

Taken together, the developmental gender literature suggests that boys and girls enter the preschool years with largely similar levels of cognitive and pre-academic skills, but with some potentially larger differences in language, social, emotional and behavioral domains. In a preschool classroom setting, these differences are thought to lead to differences in child-teacher relationship quality as well as how children spend their time, especially during unstructured child play time. Specifically, girls are described as having closer and less conflicted relationships with their teachers than boys (Ewing & Taylor, 2009). In addition, girls are also described as being more involved in cognitively stimulating classroom activities and verbally mediated and prosocial imaginary play, than boys, especially during self-directed free play time (Early et al., 2010; Goble, Martin, Hanish, & Fabes, 2012). If teachers are the conduits of instructional content and serve an important scaffolding role in children's learning (Burchinal et al., 2015), then the closeness of girls with their teachers provides a basis for arguing that girls are likely to learn more early academic skills from ECE programs than boys. The same hypothesis might also hold for ECE's impacts on girls' behaviors. Again, girls' better self-regulatory skills and closer relationships with their teachers may mean that they are particularly likely to attend to their teachers' efforts to develop their social and behavioral skills, and they may be more able to meet their teachers' behavior expectations, thus creating positive interactions the fuel further prosocial behavior and self-regulation. Notably, this developmental explanation is consistent with Heckman's (2008) observation that “skills-beget-skills” during later childhood.

However, the comparison of program impacts requires a comparison of not only boys and girls in the same ECE settings, but also how they might experience the counterfactual settings of their home and other informal care environments. Conceptually, the largest gains in learning might be experienced by children for whom ECE provides the greatest increases in learning activities and enriching interactions relative to the comparison group conditions. That is, although girls may be more likely to be closer with teachers and engaged in cognitively stimulating activities in preschool settings than boys, it may also be the case that they are more likely to experience these types of interactions and experiences when cared for in other settings too, such as at home. Thus, in the same way that high-quality ECE is thought to be a compensatory form of education for children at risk of low achievement due to demographic characteristics such as poverty and low-parent education (Burchinal, Peisner-Feinberg, Bryant, & Clifford, 2000; Cote, Doyle, Petitclerc, & Timmins, 2013; Hubbs-Tait et al., 2002), it may also be compensatory for boys' cognitive skills and pre-academic learning, engaging them in more stimulating learning activities, especially during structured teacher-led activities, than they might otherwise experience in other settings. This might be especially true of high-quality programs with teachers who are adept at classroom management that engages children across a range of behavioral profiles.

Whether or not the compensatory framework is applicable to ECE gender differences is unclear, and likely dependent on how boys and girls experience non-ECE settings (as well as how they experience ECE settings). Although there is some evidence that boys may have slightly less stimulating experiences in their homes than girls (Bertrand & Pan, 2013), the differences are not extensive or of a as large magnitude as found in relation to poverty or other demographic risks. Time-use data suggest young boys spend more time watching cartoons on television and playing video games than girls (Huston, Wright, Marquis, & Green, 1999) as well as less time reading (Hoffereth & Sandberg, 2001). In addition, Bertrand and Pan's (2013) analysis of kindergarteners suggests that parents do invest more in girls than boys along some dimensions. For example, parents read to girls more frequently than boys, and girls also participate in more extra-curricular activities than boys. They also find that parents both report greater closeness with daughters and feel more love from their daughters than sons. A priori, given the relative small differences in home experiences that prior research has uncovered, it is hard to know whether such differences are really consequential for characterizing ECE impacts on boys as compensatory.

It is also important to consider the type of outcome being assessed. If ECE improve boys' cognitive skills and pre-academic learning in the short term, it is possible that this may lead to differential gender effects on other outcomes, specifically special education and grade retention. Boys are more likely to be placed in special education and be retained compared with girls (DiPrete & Jennings, 2012). If boys are more likely to be among the lowest-performing and worst-behaved students, then improving their skills may have a bigger pay off in preventing such remedial efforts, which are usually targeted to a small percent of children with academic and behavioral difficulties, than improving skills of girls, who on average are higher in the distributions (Winsler et al., 2012).

In sum, in seeking to understand the main effects of ECE on boys and girls learning and behavior, there are two conceptual arguments to be considered. First, girls' stronger language skills as well as closeness with teachers and more active engagement in cognitively stimulating activities compared with boys, may yield larger impact on their skills and behaviors. On the other hand, the difference in engagement between home or other informal care and ECE settings may be larger for boys compared with girls, as boys would otherwise experience fewer enriching activities and interactions than girls, thus contributing to a larger impact on their skills and behaviors. Given these two considerations, which are not mutually exclusive, it is unclear one explanation will dominate or if they will work simultaneously such that they produce offsetting advantages and thus, in general, few gender differences in ECE impacts.

Gender Differences in Program Evaluation Findings

Empirical evidence about whether gender moderates the effects of ECE program impacts is both scant and mixed. Though some ECE studies report gender differences, the findings are not consistent, and for the most part studies have not made gender differences an explicit focus of their work. As we review in detail in this section, several early model demonstration programs seem to have had larger effects on girls, but other studies have shown larger effects on boys or no gender differences at all. We review this pattern of findings from prior studies.

The influential evaluations of two model programs, Perry Preschool and Abecedarian, examined gender differences in program impacts, and identified some outcomes favoring girls. Specifically, Perry Preschool had somewhat larger and longer lasting program impacts on IQ, educational attainment and adult economic outcomes for girls than for boys (Schweinhart et al., 2005). However, program impacts on crime favored boys. In the Abecedarian program, there were larger impacts on measures of verbal IQ and educational attainment for girls than for boys. However, there were no significant gender differences in program impacts on academic skills and other young adult and adult economic outcomes (Campbell, Ramey, Pungello, Sparling, & Miller-Johnson, 2002; Campbell et al., 2012).

Anderson (2008) reanalyzed original data from Perry Preschool, Abecedarian, and the Early Training Project and broadly concluded that girls benefit more from ECE than boys. To remedy the problem of multiple statistical comparisons within these studies, he created composites of conceptually similar outcomes and adjusted p-values levels for multiple tests. He estimated gender-specific program impacts and conducted analyses that pooled outcome data across programs. Focusing on patterns and magnitudes of effect sizes in the pooled estimates, he found that programs benefited both girls and boys in middle childhood. However, for outcomes measured during teen and adult years, female ECE participants demonstrated significant positive program impacts of moderate effect sizes, whereas males experienced negligible program impacts. These findings led Anderson to conclude that ECE programs have larger, more meaningful, and longer-lasting impacts on girls compared with boys.

The gendered pattern of program impacts for some outcomes among three model demonstration programs has not been replicated in recent analyses of other ECE programs. Ou and Reynolds (2010) found that the Chicago Child-Parent Center (CPC) program had stronger long-term effects on the educational outcomes of boys compared with girls. Boys who attended CPC had 20-percentage-point higher levels of high school completion (high school graduation and GED attainment) as well as more years of completed schooling than boys in the comparison group. Such program impacts did not occur for girls. Further analyses revealed that the primary mechanism explaining these program impacts was the early cognitive advantage that CPC participation gave boys as they started school. Ou and Reynolds (2010) did not examine gender differences in behavioral or other adult outcomes.

Similarly, (Deming 2009) found that boys benefitted more from Head Start in the long run than girls, including higher achievement test scores and educational attainment, reduced rates of grade retention and crime, and better health. Deming also found that the effects of Head Start faded out significantly faster for girls compared to boys. Likewise, Hill, Gormley, and (Adelstein's 2012) analysis of the Tulsa, Oklahoma prekindergarten program found that program impacts on math persisted through third grade for boys and not girls. However, reading impacts did not last to third grade for either girls or boys.

Several other studies have not found any evidence of gender differences in ECE program effectiveness. Weiland and Yoshikawa (2013) found that the effects of Boston's public prekindergarten program did not differ by gender. Finally, in examining the more general experience of center-based child care, Burchinal et al. (2000) and Vandell, Belsky, Burchinal, Steinberg, and Vandergrift (2010) found that the effects of center-based child care experienced during early childhood on cognitive, achievement and behavior outcomes did not differ by gender, early in life or during adolescence.

Program Characteristics and Differential Effects by Gender

The inconsistency in findings across evaluations serves to underscore the importance of taking into account the variability in programs and how that may shape boys and girls differentially. Given that the empirical evidence regarding the effects of ECE by gender are mixed, the question of why girls might benefit more (or less) than boys in some programs or evaluations and not in others is important. One potential source of variability in gender impacts is the design of the programs being studied, including the quality of the ECE program in terms of the learning opportunities it provides as well program goals. Another explanation might be related to the features of the evaluation design itself. We speculate about both of these explanations in turn.

A key challenge in assessing whether variability in ECE program quality explains the gendered pattern of program impacts is the lack of information about the ECE programs provided in evaluation studies. Unfortunately, not all ECE program evaluations systematically report on indicators of either structural or process quality, the two most common ways to measure ECE quality (Burchinal et al., 2015). For example, studies rarely describe teachers' levels of education or provide scores on observational quality measures that report of quality of instruction, classroom management or teacher-child interactions. Other proxies of quality, such as use of a manualized curriculum or child-teacher ratios are more commonly reported in evaluations, but these may somewhat less clearly conceptually aligned with differential gender impacts. Nevertheless, indicators such as these may predict higher quality programs by facilitating better organized classrooms with greater presence of developmentally appropriate learning activities, and fostering more engaging and responsive interactions between teachers and children (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2002). To the extent that girls' greater engagement in learning activities and closer teacher relationships propels their learning, it may be these features are most beneficial for them. On the other hand, if girls tend to be engaged in stimulating activities even in lower-quality classrooms, whereas boys do not, this may suggest that classroom quality has a greater benefit for boys.

One program feature that may disproportionately benefit boys is a focus on promoting positive behavior. Although all programs seek to improve children's academic skills, some adopt a more holistic approach and also explicitly aim to improve children's behavior. Given boys' early behavioral self-regulation deficits compared with girls, it is possible that programs that target behavior may have greater effects on boys' outcomes than girls. That is, if they are able better equipped to engage boys and improve their behavioral skills, they may also enable boys to learn more than girls. Any such differential may be more evident for academic outcomes that are closely linked with behavioral measures of school success, such as grade retention or disciplinary referrals. Studies suggest that achievement may not be as strongly linked with aggression or externalizing behavior as other learning related behaviors that are frequently used as markers of school success such as engagement (Dowsett, Claessens, Duncan, Pagani, & Sexton, 2010).

Finally, the “model” programs studied by Anderson (Abecedarian, Early Training Project, and Perry Preschool) may share other characteristics that differ from most other early childhood interventions in ways that may explain their pattern of program impacts by gender. While there may be no theoretical justification to expect differential effects by gender due to shared idiosyncratic program features, it is important to make sure that any differential effects are not driven by such characteristics. First, these programs took place during the 1960s and 1970s. Although the contexts of early childhood education have changed since its early inception, it is unclear why the early historical context would benefit girls more than boys (other than through historical changes in quality or program goals discussed above). It is also worth noting that only two of the three program evaluations in Anderson's study employed true random assignment. It is not clear why this might affect patterns of gender effects, but explanations related to research design should be considered.

The Current Study

This study seeks to better understand the extent to which the presumed benefits of ECE accrue to boys and girls across multiple outcome domains. Is the finding that boys do not demonstrate as large or as long-lasting educational gains from early childhood programs compared with girls particular to the three studies Anderson (2008) analyzed? Using data from a broader set of ECE evaluations than prior studies and employing rigorous meta-analytic methods, we investigate whether ECE programs have differential effects on boys and girls in four domains: cognitive and achievement outcomes, other school-related outcomes such as grade retention and special education placement, child behavior and mental health, and adult outcomes such as health, welfare receipt, crime, and earnings. We also consider whether any such effects differ by important program characteristics such as the quality of the program, the timing of the outcome measurement (at program completion or a later follow-up), the goals of the programs, when the program began, and other aspects of the study design such as random assignment.

Method

To understand whether the effects of ECE programs differ by gender, we conducted a meta-analysis, a method of quantitative research synthesis that uses prior study results as the unit of observation (Cooper & Hedges, 2009). To combine findings across reports, estimates were transformed into a common metric called an “effect size,” expressed as a fraction of a standard deviation. Outcomes from individual reports were used to estimate the average effect size across programs. Additionally, meta-analysis was used to test whether average effect sizes differed by characteristics of the programs, in this case the gender of participants. After defining the problem of interest, meta-analysis proceeds in the following steps, described below: 1) literature search, 2) data evaluation, and 3) data analysis.

Meta-analytic Data

The ECE studies analyzed in this paper compose a subset of studies from a large meta-analytic database being compiled by the National Forum on Early Childhood Policies and Programs. This database includes studies of child and family policies, interventions, and prevention programs provided to children from the prenatal period to age five, building on a previous meta-analytic database created by Abt Associates, Inc. (Jacob, Creps, & Boulay, 2004; Layzer, Goodson, Bernstein, & Price, 2001).

The starting point for our database was a list of studies conducted between 1960 and 2003 in the United States and its territories, compiled by Abt Associates. We used a number of search strategies to identify any additional published and unpublished program evaluations conducted between 1960 and 2007 (the year in which the project began). The research team conducted keyword searches in the ERIC, PsycINFO, and Dissertation Abstracts databases, as well as searched additional specialized databases, government databases, ECE policy group websites, and conference programs. Finally, the team also contacted researchers in the field and tracked down additional reports mentioned in all obtained references. Over 200 new ECE evaluations were identified, in addition to the approximately 73 originally coded by Abt that met our general ECE screening criteria.

The ECE screening criteria were designed to identify high-quality studies that evaluated programs serving a typically developing population of children. First, programs that explicitly targeted children with identified special needs or other diagnosed medical conditions were excluded. Second, we developed a set of inclusion criteria to identify studies that were methodogically strong (and to screen out those that were methodologically weak). To be included, programs had to have 1) a comparison or “control” group; 2) at least ten participants in the treatment and control condition; 3) attrition of less than 50 percent; and 4) a rigorous research design that would minimize omitted variable bias. Evaluations using the following research designs were included because of their ability to minimize omitted variable bias: regression discontinuity, fixed effects (individual or family), difference-in-difference, instrumental variables, propensity score matching, and interrupted time series. Two additional types of research designs were also included because of their likely rigor: 1) studies in which the comparability of the treatment and control group were demonstrated on baseline characteristics (determined by a statistical joint test of time-invariant characteristics); and 2) studies in which the treatment and comparison groups were not comparable on baseline characteristics, but for which baseline measures (pre-tests) of the outcomes were used to control for any baseline differences.

For the current study, we imposed some additional inclusion criteria. First, given our focus on gender differences, we excluded all programs (and outcomes within programs) that did not provide results separately by gender (92% of programs and 93% of effect sizes in the full database). Second, we included only evaluations that provided at least one measure of children's cognitive, achievement skills, behavior, other school-related outcomes, or adult follow-up outcomes. Third, we included only programs that measured differences between center-based ECE participants and control groups that were not assigned to receive a set of equivalent ECE services. For example, evaluations that compared the effects of Head Start to another type of early education program were excluded (although they are in the larger database). Finally, we limited our analysis to programs that served preschool-age children (ages 3-5). There were only two programs in our database that met all other inclusion criteria but served only infants and toddlers when treatment began; including these programs in our analysis did not affect our findings. We made an exception to our inclusion rules for the Abecedarian Project because treatment continued from birth until age five, it is viewed as a model early childhood program, and it was included in Anderson's analyses.Twenty-three programs met all of these criteria detailed above.

The research team developed a protocol to code information about the ECE evaluations in the database. Information about program design, sample characteristics, and statistical information needed to compute effect sizes were collected (see the online supplementary material for a list of references of reports that provided information for our study). A team of a dozen graduate research assistants were trained as coders during a 3- to 6-month process that included instruction in evaluation methods, using the coding protocol, and computing effect sizes. Before coding independently, research assistants worked with more experienced coders and passed a coding reliability test by calculating all effect sizes correctly and achieving 80% agreement with a master coder for the remaining codes. In instances when research assistants were just under the threshold for effect sizes, but were reliable on the remaining codes, they underwent additional training before coding independently and were subject to periodic checks during their transition to independent coding. Questions about coding were resolved in weekly research team conference calls.

The resulting database is organized in a three-level hierarchy (from highest to lowest): the program, the contrast, and the effect size. A “program” is defined as a collection of comparisons in which the treatment group received a particular model of center-based ECE and is compared to a sample of children drawn from the same population who were assigned to receive no equivalent ECE services (although some children might seek out alternative ECE services under different auspices if they chose). One ECE report included evaluations of four programs, and these are considered to be different programs in our analysis. Each program also produces a number of “contrasts,” defined as a comparison between one subsample of children who received center-based ECE and another subsample of children who received no equivalent services. Each program in our study has at least two contrasts—one for boys and one for girls. In turn, within each contrast there are multiple individual “effect sizes,” measured by the estimated standard deviation unit difference in an outcome between the children who experienced center-based ECE and those who did not, corresponding to the particular measures that are used.

The data for this study include 23 ECE programs and 72 contrasts, 36 each for boys and girls (some programs separate outcome analyses by other characteristics such as age, so some programs have multiple contrasts of one gender, such as 3-year-old boys and 4-year-old boys). The 72 contrasts in the database provide a total of 808 effect sizes (Table 1). (However, we were unable to calculate some of these effect sizes due to missing data; we discuss this in more detail below). The median posttest sample size for the treatment and control groups is 69 and 31 children, respectively. Seventeen of the 23 programs in our analysis primarily served children from low-income families.

Table 1. Key Meta-Analysis Terms and Sample Sizes.

| Term | Description | Number in database |

|---|---|---|

| Report | Written evaluation of early childhood education (e.g., a journal article, government report, book chapter) containing separate effect sizes by gender and meeting inclusion criteria | 36 |

| Program | Collection of comparisons in which groups are assigned to distinct treatment and control groups | 23 |

| Contrast | Within-program comparison between one group of children who received center-based ECE and another group of children who received no equivalent ECE services, there are at least two contrasts for each program in our analysis (boys, girls), and some instances several more when results are presented separately by other characteristics such as location or age. | 72 |

| Effect Size | Measure of the difference in cognitive outcomes between the children who experienced center-based ECE and those who received different or no equivalent services, expressed in standard deviation units | 808 |

In Table 2, we present descriptive characteristics for the effect sizes that met our inclusion criteria and those that would have met all of our inclusion criteria, except that the program evaluations did not present separate gender contrasts. Effect sizes used in this study significantly differed from the effect sizes from other programs that did not have gender contrasts (but otherwise met our inclusion criteria) (Table 2). The effect sizes in this analysis come from programs that are older, less likely to be multi-site studies or indicate improving children's behavior as a goal, and are more likely to have come from researcher-designed studies with low teacher/child ratios or from long-term follow-ups of program participants. Although not presented in Table 2, we also found that the programs reporting impacts by gender had smaller average effect sizes across all domains than programs without gender contrasts (.19 vs .39, p < .05). Finally, the gender composition of the children in the evaluation studies does not differ between programs that are or are not included in the analysis (49.3% male for programs not included compared to 50.3% male for programs included).

Table 2. Summary Statistics of the Meta-Analytic Dataset by Effect Size.

| Characteristic | Value | Programs Not Used | Programs Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starting year of program | 1960-1975 | 51.1% | 85.6% |

| 1976-2007 | 41.4% | 13.9% | |

| Number of sites | One | 5.7% | 39.6% |

| Two or more | 72.3% | 45.0% | |

| Urbanicity | Urban or suburban | 33.3% | 51.7% |

| Rural | 2.0% | 37.6% | |

| Missing or mix | 64.7% | 10.6% | |

| Method of assignment | Random | 9.7% | 36.1% |

| Quasi-experimental | 72.9% | 55.4% | |

| Other | 17.4% | 8.4% | |

| Goal: improve child behavior | Yes | 79.7% | 48.5% |

| No/missing | 20.3% | 51.5% | |

| Parental education | Yes | 54.9% | 72.5% |

| component | No/missing | 45.1% | 27.5% |

| Researcher-designed intervention | Yes | 14.1% | 67.8% |

| No | 85.9% | 32.2% | |

| Yes | 28.7% | 66.1% | |

| Satisfactory teacher:child ratio | No/missing | 71.3% | 33.9% |

| Length of treatment | 0-12 months | 84.4% | 36.1% |

| 12-24 months | 3.1% | 34.9% | |

| 24+ months | 6.9% | 19.6% | |

| Other services received | None | 42.1% | 75.7% |

| by control group | Some | 52.1% | 24.3% |

| Missing | 5.7% | 0.0% | |

| Standardized curriculum | Yes | 47.7% | 66.3% |

| No/missing | 52.3% | 33.7% | |

| Outcome domain | Cognitive skill | 53.6% | 46.0% |

| Achievement | 22.8% | 22.8% | |

| Other school outcomes | 8.8% | 12.9% | |

| Child behavior and mental health | 5.4% | 5.4% | |

| Adult outcomes | 9.4% | 12.9% | |

| Months elapsed since | During treatment | 9.7% | 17.3% |

| end of treatment | 0-12 months | 62.3% | 27.5% |

| 12-24 months | 6.1% | 7.7% | |

| 24+ months | 11.9% | 38.1% | |

| Number of programs | 101 | 23 | |

| Number of effect sizes | 3120 | 808 |

Note. The percentages reported reflect the number of effect sizes that have the above characteristics. “Programs not used” meet all inclusion criteria except they did not include male vs. female contrasts, while “programs used” reflect only programs with contrasts that met all criteria. The two groups differ at p<.001 on each group of characteristics.

Because 124 programs met our ECE database inclusion criteria but did not contain gender contrasts, we might worry that the programs which reported results by gender did so because in “fishing” for results they detected variation in impacts by gender that were statistically significant by chance. This form of publication bias might affect the validity of our findings (Chan, Hrobjartsson, Haahr, Gotzsche, & Altman, 2004; Hopewell, Loudon, Clarke, Oxman, & Dickersin, 2009). To explore whether gender contrasts appear to be selectively reported, first we examined the extent to which 23 programs also reported findings for other subgroups. All seven of the programs with racial or ethnic diversity in their samples also reported separate results by race/ethnicity. In addition, four programs that did not report racial or ethnic group differences reported other subgroup results by parental education, site of the intervention, or family income. This pattern suggests that the presentation of program impacts by gender was often part of a broader examination of multiple subgroups; thus, it seems unlikely that these results were “cherry-picked” for statistical significance.

Next, we examined the extent to which programs that did not report gender contrasts presented results separately by race (a comparable background characteristic of interest to researchers). Only 11 of the 101 programs that did not report gender contrasts but met the broader inclusion criteria reported contrasts by race. Again, this pattern suggests that, in general, gender impacts are analyzed as one of several potential subgroups, rather than selectively chosen. Finally, it is worth noting that after our cut-off publication date of 2007, a handful of reports analyzing gender differences for programs in the ECE database were published or circulated (Deming, 2009; Joo, 2010; Ou & Reynolds, 2010; Vandell et al., 2010).

As a final check, we also attempted to contact by email authors of a random sample of half of the 30 evaluations of programs which began after 1990 but did not include separate outcomes by gender. We asked the authors whether they tested for differential effects by gender and whether their findings were statistically significant. Of the fifteen authors sampled, we were only able to find thirteen authors with current contact information. We received responses from ten of these thirteen authors to an email inquiry. Eight of the authors either did not estimate results separately by gender or did not recall doing so. One author reported finding no systemic differences by gender, and one author provided us with a conference poster from late 2007 with results by gender (Corrington, Gormley, & Phillips, 2007). This poster was then included in our analysis.

Measures

Effect sizes

The dependent variables in these analyses are the effect sizes measuring the impact of ECE on children's cognitive/achievement, behavior, and other school-related and adult outcomes. The cognitive outcomes are primarily measures of IQ and vocabulary, although this domain also includes a few measures of theory of mind, attention, task persistence, and syllabic segmentation (e.g., rhyming). The achievement outcomes include measures of early reading, math, letter recognition, and numeracy skills. We initially separated cognitive and achievement outcomes because skills in the achievement domain are considered to be more sensitive to instruction than cognitive skills (Christian, Morrison, Frazier, & Massetti, 2000). However, since the results were similar, we combined the two domains in the bivariate and multivariate models.

On average, the cognitive and achievement outcomes were measured just over four years after the beginning of treatment. Other school-related outcomes are primarily measures of school progress, including attendance, grades, retention, special education placement, high school completion, and in a few instances educational expectations and aspirations. On average, other school-related outcomes were measured nine and a half years after treatment began, and all were measured before children were approximately 18 years old. Child behavior and mental health outcomes, which were measured on average seven and a half years after treatment began, include in roughly equal proportions behavior problems (aggression, hyperactivity, and withdrawal), self-esteem, and locus of control. We separated the aggressive, externalizing behavior and hyperactivity outcomes from the other behavior outcomes as a robustness check, but the results did not substantially change. We combined all of the behavior measures in the final analysis due to a small number of effect sizes (36 for the entire domain).

Finally, the adult outcomes are diverse in scope, including outcomes related to health behavior such as alcohol and tobacco use, fertility (e.g., teen childbearing), educational attainment measured after age 18, crime, employment, wages, and the use of social and other economic support services. We also estimated gender effects separately on two broad categories of adult outcomes (behavior/health and attainment/utilization of services) and found similar patterns, so they were combined in the final analysis. These outcomes were measured on average over 22 years after treatment began.

Authors reported outcome information using a number of different statistics, and because not all measures within a domain were of the same nature (continuous or dichotomous only) we calculated Hedges' g effect sizes for all types of data with the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2005). Hedges' g is an effect-size statistic that makes an adjustment to the standardized mean difference (Cohen's d) to account for bias in the d estimator when sample sizes are small. When sample sizes are small, using Hedges' g results in a very slight reduction in the magnitude of effect sizes compared with Cohen's d, and is interpreted in a similar way as other standard mean-difference effect-size metrics (Durlak, 2009; Hedges & Olkin, 1985). Sixty-two of the 72 contrasts provided more than one effect size to the analysis. Non-missing effect sizes across all outcomes range from -1.04 to 2.27, with an average weighted effect size of .18.

The numbers of effect sizes across programs and outcome domains are presented in Table 3. Table 4 provides average unweighted effect sizes by gender across programs and domains. Although 21 of the 23 programs contribute effect sizes to the cognitive or achievement domain, only nine programs report effect sizes for other school outcomes, nine programs report effect sizes for behavior outcomes, and three programs (the same three included in Anderson's analysis) include effect sizes for adult outcomes.

Table 3. Programs Contributing Effect Sizes by Domain.

| Year Began | Cognitive Outcomes | Achievement Outcomes | Other School Outcomes | Child Behavior | Adult Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Name | ||||||

| Abecedarian Project | 1972 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 0 | 8 |

| BYU Preschool Program | 1980 | 8 | 22 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| California Head Start Follow-Up | 2000 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Cambridge, MA Summer Head Start | 1965 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Charlotte Bright Beginnings Pre-K | 1997 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Early Training Project | 1962 | 14 | 14 | 22 | 4 | 14 |

| Fairfax Co. (VA) Disadvantaged Pre-K | 1965 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Guam Head Start Study | 1985 | 8 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Home Oriented Preschool Education | 1968 | 214 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Howard University Preschool Program | 1964 | 20 | 28 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| Lincoln, NE Summer Head Start | 1965 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Louisville Bereiter-Englemann Pre-K | 1968 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0 |

| Louisville DARCEE Pre-K | 1968 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Louisville Montessori Pre-K | 1968 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0 |

| Louisville Traditional Pre-K | 1968 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lubbock, TX Summer Head Start | 1965 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 4 | 0 |

| Montgomery County (MD) Head Start | 1966 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NY Disadvantaged Pre-K | 1965 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| National Early Reading First Evaluation | 2004 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| National Head Start Impact Study | 2002 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 |

| Perry Preschool Program | 1962 | 8 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 82 |

| Tulsa Pre-K Program | 2002 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| University City (MO) Personalized Pre-K | 1967 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Number of effect sizes | 372 | 178 | 104 | 44 | 104 |

Table 4. Average Effect Sizes by Program, Domain, and Gender.

| Cognitive/achievement | Other school outcomes | Behavior/mental health | Adult outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Name | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female |

| Abecedarian Project | .54 | .71 | .11 | .44 | - | - | .20 | .30 |

| BYU Preschool Program | .44 | .24 | - | - | .14 | -.20 | - | - |

| California Head Start Follow-Up | .60 | -.22 | .86 | -.21 | - | - | - | - |

| Cambridge, MA Summer Head Start | .03 | .25 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Charlotte Bright Beginnings Pre-K | .26 | .23 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Early Training Project | .01 | .00 | -.16 | .27 | .04 | -.16 | -.04 | -.01 |

| Fairfax Co. (VA) Disadvantaged Pre-K | .80 | 1.10 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Guam Head Start Study | -.01 | .04 | .00 | .00 | - | - | - | - |

| Home Oriented Preschool Education | .32 | .17 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Howard University Preschool Program | .45 | .63 | .28 | -.02 | -.57 | -.26 | - | - |

| Lincoln, NE Summer Head Start | -.02 | .04 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Louisville Bereiter-Englemann Pre-K | .25 | -.27 | .28 | .12 | .30 | .32 | - | - |

| Louisville DARCEE Pre-K | - | .00 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Louisville Montessori Pre-K | .43 | -.16 | .56 | .08 | .14 | .25 | - | - |

| Louisville Traditional Pre-K | .00 | .00 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lubbock, TX Summer Head Start | - | - | .23 | -.31 | - | - | - | - |

| Montgomery County (MD) Head Start | -.41 | -.13 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| National Early Reading First Evaluation | .05 | .10 | - | - | -.05 | -.04 | - | - |

| National Head Start Impact Study | - | - | - | - | .02 | .11 | - | - |

| NY Disadvantaged Pre-K | .24 | .25 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Perry Preschool Program | .45 | .52 | .14 | .67 | - | - | .29 | .42 |

| Tulsa Pre-K Program | .15 | .20 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| University City (MO) Personalized Pre-K | .35 | .33 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Program and effect size characteristics

The key independent measure is a dichotomous indicator of whether the effect size is estimated for boys or girls (boy = 1; girl = 0). In some analyses, we also use other program characteristics as additional predictors of effect sizes. The selected indicators of program quality included being a researcher-designed ECE program, having a satisfactory teacher:child ratio, and the use of a standardized curriculum. We chose to use whether a researcher had designed the intervention as a proxy for quality because this suggests both that the program had an articulated theory of change and typically was described in reports as a “model” program with high levels of implementation fidelity. This distinction also serves to separate programs which were designed as an efficacy study of developmental malleability from those (such as Head Start) which were not specifically designed for either scientific or evaluative purposes. Satisfactory teacher:child ratio was defined as meeting the commonly used ratio guidelines created by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. We coded a program as having a standardized curriculum if it was a part of a larger program with known curricular requirements (such as Head Start) or if the evaluation explicitly referred to a standardized curriculum. Finally, programs were coded as having a goal of improving child behavior if the reports clearly mentioned it as being one of the primary goals of the intervention.

In addition, we used dummy variables to capture other shared features of Anderson's studies. First, we created an indicator for whether the program began before 1976, as all of Anderson's studies did. 1 The cutoff of 1976 was used because this was a natural breakpoint in our programs (see Table 3). Second, we used a measure of whether the study used random assignment to place children in the treatment and comparison conditions, as was the case for two of the three Anderson studies. Third, we included a dummy variable for whether an effect size was measured more than 12 months after program completion, as all of Anderson's programs had long-term follow-ups.

The distribution of program characteristics across programs is provided in Table 5. Most programs (although not the majority of effect sizes) have the goal of improving children's behavior and many also follow up with children with outcomes measured more than one year after program completion. Few were conducted after 1976, used random assignment, or were researcher-designed interventions. It is also worth noting that 17 of the 23 programs in our analysis primarily served students from low-income families.

Table 5. Programs Contributing Effect Sizes by Services Offered and Program Characteristics.

| Study Name | Researcher- designed intervention |

Standard curriculum |

Satisfactory teacher:child ratio |

Goal: Improve behavior |

Random assignment |

Began after 1976 |

>12 months post- treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abecedarian Project | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| BYU Preschool Program | X | X | X | X | |||

| California Head Start Follow-Up | X | X | X | ||||

| Cambridge, MA Summer Head Start | X | X | |||||

| Charlotte Bright Beginnings Pre-K | X | X | X | X | |||

| Early Training Project | X | X | X | X | |||

| Fairfax Co. (VA) Disadvantaged Pre-K | X | ||||||

| Guam Head Start Study | X | X | |||||

| Home Oriented Preschool Education | X | X | X | X | |||

| Howard University Preschool Program | X | X | X | X | |||

| Lincoln, NE Summer Head Start | X | ||||||

| Louisville Bereiter-Englemann Pre-K | X | X | X | ||||

| Louisville DARCEE Pre-K | X | X | X | ||||

| Louisville Montessori Pre-K | X | X | X | ||||

| Louisville Traditional Pre-K | X | X | X | ||||

| Lubbock, TX Summer Head Start | X | ||||||

| Montgomery County (MD) Head Start | X | X | |||||

| NY Disadvantaged Pre-K | X | X | X | ||||

| National Early Reading First Evaluation | X | ||||||

| National Head Start Impact Study | X | X | X | ||||

| Perry Preschool Program | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Tulsa Pre-K Program | X | X | |||||

| University City (MO) Personalized Pre-K | X | X |

Missing data

In some studies, authors mentioned gender differences in program impacts, but did not provide enough statistical information to calculate effect sizes; for example, references were made to non-significant findings for outcomes for gender subgroups, but numerical estimates were not provided. There were also a few effect sizes for which we estimated the final sample size based on the initial sample size and the attrition level in other contrasts within the program. There are 132 effect sizes within 11 programs with sufficient missing information so that effect sizes could not be calculated. Indeed, one contrast (boys vs. girls within a program) was entirely missing. As a result, the non-missing sample for analysis consists of 676 effect sizes, in 71 contrasts, within 23 programs.

Excluding missing effect sizes could bias our treatment effects; therefore, we coded all available information for such measures, but coded actual effect sizes as missing. This enabled us to test the sensitivity of our findings to various assumptions about size and nature of the missing effect sizes. For most program characteristics, there were no missing data; only two characteristics had missing data (20 percent for satisfactory teacher:child ratios and two percent for improving behavior). In those cases, we assumed that the characteristic was not present in the program.

Statistical Analysis

Our key research question is whether the effect of ECE programs on the cognitive, achievement, school-related, behavior, and adult outcomes differs by gender. To test this hypothesis, we estimate a multi-level, multivariate model. The level-1 effect size model is:

| (1) |

In this equation, each effect size (ESij), representing effect size i and program j, is modeled as a function of the intercept (β0j), which represents the average effect size among all programs, the key parameter of interest--a dummy variable for whether the effect size is for boys or girls (β1ix1ij), a small number of other covariates (in some models) measuring program features or characteristics of the effect sizes (β2ix2ij), and a within-program error term (eij). The level-2 equation (program level) models the intercept as a function of the grand mean effect size for the program (β00) and a between-program random error term (u0j):

| (2) |

This “mixed effects” model assumes that there are two sources of variation in the effect size distribution, beyond subject-level sampling error: 1) the “fixed” effects of between-effect size variables measured by gender and other effect size covariates; and 2) remaining “random” unmeasured sources of variation between and within programs.

To account for differences in the precision of effect size estimates as well as the difference in the number of estimates provided by each program, regressions are weighted by the inverse variance of each effect size multiplied by the inverse of the number of effect sizes within a program (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). This approach ensures that effect sizes with greater precision are given more weight, but that program evaluations with a large number of effect sizes are not given undue weight compared with those with fewer outcomes.

As a robustness check, we also estimated our models with several different sets of weights. We used a method of moments, non-iterative, two-level model with identical variance within clusters and a within-cluster correlation of .8 (Hedges, Tipton, & Johnson, 2010) as well as a method of moments, iterative, two-level model with various variance within clusters (Stevens & Taylor, 2009). As the results were qualitatively similar, we present results from models that used the simpler weights.

We begin by estimating simple regressions by domain in which the only variable in the model is a dummy variable for whether the contrast included only boys. Due to the balanced nature of the dataset (boys and girls experienced the same programs and were assessed in the same way), there is little benefit to adding in other demographic covariates. The within-program comparison of effects by gender by design holds constant program features, and there are unlikely to be important differences in measured individual child characteristics such as age, race, or ethnicity.

To explore whether gender differences are moderated by program features, we estimated models with statistical interaction terms included as predictors. Finally, because program characteristics might be correlated, we estimated a model with all of the interaction terms in one model in order to isolate the unique variance associated with each feature.

Results

Gender Differences in ECE Program Impacts

Do ECE program impacts differ for boys and girls? The results from a simple multi-level regression model using outcome measures from all domains, in which the intercept term represents the average effect size for females and the coefficient on the dummy variable for “Male” measures the difference in effect sizes for males compared with females. Results reveal a small, but statistically significant effect size difference (.03 SD) favoring girls (Table 6).

Table 6. Summary of Meta-Analysis Results by Outcome Domain and Gender (Standard Errors in Parantheses).

| Domain | Female treatment effect | Male-female difference |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | .20** | -.03** |

| (.05) | (.01) | |

| Number of effect sizes (number of programs) | 676 (23) | |

| Cognitive and achievement outcomes | .23** | -.03* |

| (.06) | (.02) | |

| Number of effect sizes (number of programs) | 441 (21) | |

| Cognitive outcomes | .32** | -.03* |

| (.09) | (.02) | |

| Number of effect sizes (number of programs) | 328 (15) | |

| Achievement outcomes | .22** | -.04* |

| (.07) | (.02) | |

| Number of effect sizes (number of programs) | 113 (14) | |

| Child behavior and mental health outcomes | .07 | -.08* |

| (.04) | (.03) | |

| Number of effect sizes (number of programs) | 36 (7) | |

| Other school outcomes | -.04 | .40** |

| (.06) | (.05) | |

| Number of effect sizes (number of programs) | 98 (9) | |

| Other school outcomes: Special ed/retention only | -.04 | .56** |

| (.13) | (.18) | |

| Number of effect sizes (number of programs) | 20 (4) | |

| Other school outcomes: Anderson's studies | .45* | -.40** |

| (.07) | (.10) | |

| Number of effect sizes (number of programs) | 66 (3) | |

| Adult outcomes | .18 | -.06 |

| (.11) | (.06) | |

| Number of effect sizes (number of programs) | 101 (3) | |

Notes:

p < .05

p < .01.

Standard errors are provided in parentheses below the coefficients. “Male” is a dummy variable equal to 1 for all-boys contrasts and 0 for all-girls contrasts. The female treatment effect refers to the effect size for girls. In this table, effect sizes with missing data are excluded from the analyses. Positive coefficients represent desirable outcomes, such as lower rates of special education referral or grade retention. Each row of the table represents a separate regression using effect sizes from the given domain.

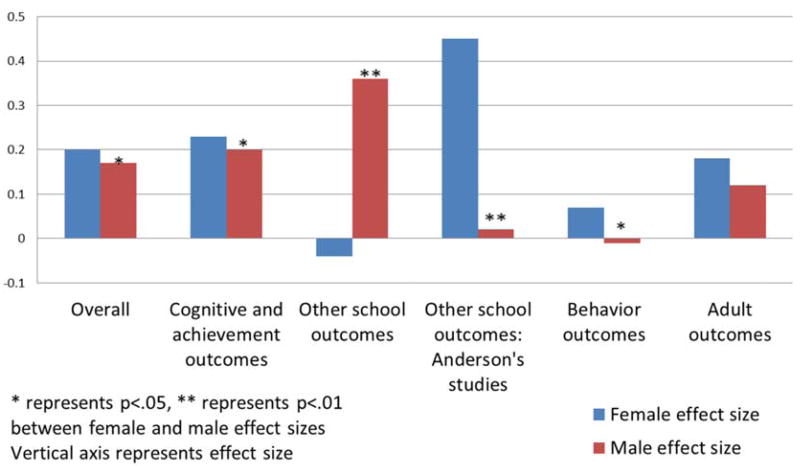

The magnitude of gender differences in program impacts, however, differs substantially across specific outcome domains (graphically shown in Figure 1). ECE programs appear to have a slightly larger benefit for girls' cognitive and achievement outcomes than for boys' outcomes. The average effect for girls is .32 SD for cognitive outcomes and .22 SD for achievement outcomes, compared to .29 SD and .18 SD for boys, respectively. Although the .03 to .04 SD gender difference in these outcomes is statistically significant, again it is small and we interpret it as not being substantively meaningful. Since we could not reject the hypothesis that program impacts on cognitive and achievement outcomes were similar, we combined these two sets of outcomes in subsequent analyses.

Figure 1. Summary of Results by Domain and Gender.

Analyzing children's behavior and mental health outcomes, we find that girls also benefit slightly more than boys (.08 SD), but the pattern of effects indicate that ECE program effects on both boys' and girls' behavior and mental health are essentially zero (the estimates are significantly different from each other, but neither is significantly different from zero). Thus, we conclude that program impacts on both boys' and girls' behaviors are, on average, negligible.

With respect to other school outcomes, results indicate a large and significant differential effect favoring boys. ECE programs had little effect on girls' other school outcomes, but boys' program impact outcomes were larger, .36 SD (-.04 intercept for females plus .40 coefficient for males). The largest category of effect sizes in this domain are measures of special education and grade retention; separate analyses of these outcomes showed larger program impacts on boys than girls (effect of -.04 SD for girls and .52 SD for boys).

We checked to see whether the findings are likely to be substantially influenced by the missing effect sizes. Table 7 includes a sensitivity check of the main results from Table 5 for different missing value specifications. We make four different assumptions about missing data: i) all missing effect sizes are set equal to zero; ii) largest possible absolute value (if the treatment group is favored, p = .11; if the comparison group is favored, p = .11); iii) maximum effect size (if the treatment group is favored, p = .11; if the comparison group is favored, p = .99), and iv) minimum effect size (if the treatment group is favored, p = .99; if the comparison group is favored, p = .11). Results are generally robust to each of the assumptions, suggesting that our results are unlikely to be sensitive to the missing effect size information.

Table 7. Robustness Checks Using Imputed Effect Sizes (Standard Errors Reported in Parentheses).

| Non-missing effect sizes |

Missing set to zero | Largest absolute value |

Maximum effect size |

Minimum effect size |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Female treat. effect |

Male - female difference |

Female treat. effect |

Male - female difference |

Female treat. effect |

Male - female difference |

Female treat. effect |

Male - female difference |

Female treat. effect |

Male - female difference |

| Overall | .20** | -.03** | .17** | -.04** | .18** | -.03** | .23** | -.04** | .12* | -.03** |

| (.05) | (.01) | (.05) | (.01) | (.05) | (.01) | (.05) | (.01) | (.05) | (.01) | |

| Number of effect sizes | 676 | 808 | 808 | 808 | 808 | |||||

| Cognitive/achievement | .23** | -.03* | .19** | -.04** | .20** | -.02 | .26** | -.03** | .13 | -.03 |

| (.06) | (.02) | (.05) | (.01) | (.05) | (.01) | (.05) | (.01) | (.06) | (.01) | |

| Number of effect sizes | 441 | 556 | 556 | 556 | 556 | |||||

| Other school outcomes | -.04 | .40** | .05 | .22** | -.00 | .32** | .03 | .27** | .02 | .27** |

| (.06) | (.05) | (.06) | (.05) | (.06) | (.05) | (.06) | (.05) | (.07) | (.05) | |

| Number of effect sizes | 98 | 104 | 104 | 104 | 104 | |||||

| Child behavior/mental health | .07 | -.08* | .06 | -.07** | .07 | -.07** | .09 | -.07** | .03 | -.07** |

| (.04) | (.03) | (.04) | (.02) | (.04) | (.03) | (.04) | (.03) | (.05) | (.03) | |

| Number of effect sizes | 36 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | |||||

| Adult outcomes | .18 | -.06 | .18 | -.05 | .20 | -.08 | .22 | -.07 | .17 | -.07 |

| (.10) | (.06) | (.10) | (.06) | (.10) | (.06) | (.09) | (.06) | (.12) | (.06) | |

| Number of effect sizes | 101 | 104 | 104 | 104 | 104 | |||||

Note.

represents p < .05

represents p < .01.

“Male” is a dummy variable equal to 1 for all-boys contrasts and 0 for all-girls contrasts. The female treatment effect refers to the effect size for girls. In this table, effect sizes with missing data are excluded from the analyses. Positive coefficients represent desirable outcomes, such as lower rates of special education referral or grade retention. Each cell of the table represents a separate regression using effect sizes from the given domain. Only non-significant effect sizes are imputed; significant effect sizes are set to p = .05. The four columns of imputed data mean the following: (1) Missing set to zero: All missing effect sizes were set to zero; (2) Largest absolute value: If the treatment group is favored, p = .11, if the comparison group is favored, p = .11; (3) Maximum effect size: If the treatment group if favored, p = .11, if the comparison group is favored, p = .99; (4) Minimum effect size: If the treatment group if favored, p = .99, if the comparison group is favored, p = .11.

Exploring Variation in Gender Differences in ECE Program Impacts

This pattern of program impacts favoring boys in the school outcomes clearly differs from those reported by Anderson (2008), despite the fact that our analysis included the three programs he analyzed. To better understand this discrepancy, we limited our analysis to only the programs included in his analysis and replicated his findings. In Anderson's three programs (Abecedarian, Early Training Project, and Perry Preschool), we find that girls benefit more from ECE programs than boys on other school outcomes (.45 SD for girls and just .05 SD for boys). When limiting to those three programs, Anderson's findings were also replicated for adult outcomes. Although the gender difference is not significant, the magnitude and direction of point estimates point to girls having a slight advantage over boys (a difference of .06 SD) for these outcomes. We found that this pattern was evident both for measures related to adults' health and behavior as well as measures related to economic outcomes (results not shown). A strong conclusion is that the pattern of findings for the studies included in Anderson's study do not hold in other studies. This argues for more careful attention to what program-level factors may lead to differing gender impacts.

To explore the variation in findings, we included descriptive characteristics about the ECE programs as predictors in a series of regressions. All the variables reported in Table 4 were used as covariates. The descriptors were also interacted with gender to test whether the characteristic is associated with differential effects by gender. The results of the bivariate regressions for the cognitive/achievement, other school outcomes, and child behavior/mental health domains are presented in Table 8.

Table 8. Bivariate Meta-Analysis Results by Domain and Gender Interactions.

| Cognitive and achievement | Other school outcomes | Child behavior and mental health | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | (SE) | Coefficient | (SE) | Coefficient | (SE) | |

| No interactions | ||||||

| Intercept (female treatment effect) | .23** | (.06) | -.04 | (.06) | .07 | (.05) |

| Male | -.04** | (.02) | .40** | (.05) | -.08* | (.03) |

| Researcher-designed intervention | ||||||

| Male | -.04** | (.02) | .52** | (.04) | -.08* | (.03) |

| Variable | .36** | (.11) | .49** | (.13) | -.26 | (.51) |

| Male*variable interaction | .01 | (.05) | -.86** | (.12) | .08 | (.71) |

| Standardized curriculum | ||||||

| Male | -.05** | (.01) | .55** | (.05) | -.08* | (.03) |

| Variable | -.10 | (.12) | .45** | (.11) | .13 | (.27) |

| Male*variable interaction | .10** | (.04) | -.62** | (.10) | .07 | (.40) |

| Satisfactory teacher:child ratio | ||||||

| Male | -.04* | (.02) | .52** | (.04) | -.08* | (.03) |

| Variable | .18 | (.10) | .49** | (.13) | -.25 | (.51) |

| Male*variable interaction | -.00 | (.02) | -.86** | (.12) | .08 | (.71) |

| Goal: Improve behavior | ||||||

| Male | -.04** | (.01) | -.23 | (.23) | -.01 | (.10) |

| Variable | -.21 | (.12) | -.30 | (.19) | .14 | (.07) |

| Male*variable interaction | .01 | (.03) | .67** | (.23) | -.07 | (.11) |

| Random assignment | ||||||

| Male | -.04** | (.01) | .49** | (.05) | -.01 | (.10) |

| Variable | .30* | (.13) | .49* | (.14) | .12 | (.07) |

| Male*variable interaction | .00 | (.04) | -.78** | (.14) | -.07 | (.10) |

| After 1976 | ||||||

| Male | -.05* | (.02) | .37** | (.05) | -.07 | (.38) |

| Variable | -.04 | (.13) | -.15 | (.17) | -.10 | (.27) |

| Male*variable interaction | .02 | (.03) | .40* | (.18) | -.01 | (.38) |

| >12 months elapsed | ||||||

| Male | -.05** | (.01) | .52** | (.06) | -.08* | (.03) |

| Variable | -.13** | (.04) | .46** | (.07) | .10 | (.27) |

| Male*variable interaction | .08* | (.04) | -.36** | (.10) | .01 | (.38) |

| Number of effect sizes | 441 | 98 | 36 | |||

Note.

represents p < .05

represents p < .01.

“Male” is a dummy variable equal to 1 for all-boys contrasts and 0 for all-girls contrasts. In this table, effect sizes with missing data are excluded from the analyses. Positive coefficients represent desirable outcomes, such as lower rates of special education or grade retention. Each cell of the table represents a separate regression using effect sizes from the given domain.

In addition, we also tested for interaction effects using the following variables: whether a program operated at multiple sites, whether a program targeted its services toward low-income families, whether the control group received at least some additional services, and whether teachers received training particular to the intervention. The main variable and interaction effects were not significant and are not reported in tables for the sake of brevity.

Adult outcomes are not included because the only three programs contributing effect sizes are the three programs examined by Anderson. They share the same characteristics, and as such variation in impacts by program characteristics cannot be identified.

Only two program characteristics interacted with gender to predict program effect sizes in the cognitive and achievement domain. As would be expected, program impacts are smaller if the assessments are administered more than 12 months after the program ended. However, program impacts for boys' achievement and cognition decline less over time than those for girls, suggesting that although there is a slightly lower ECE program impact at program completion for boys compared with girls (.05 SD difference), there is slightly less fadeout in program effects for boys over time (.08 SD difference) than girls. Additionally, boys benefited more from programs that provided a standardized curriculum.

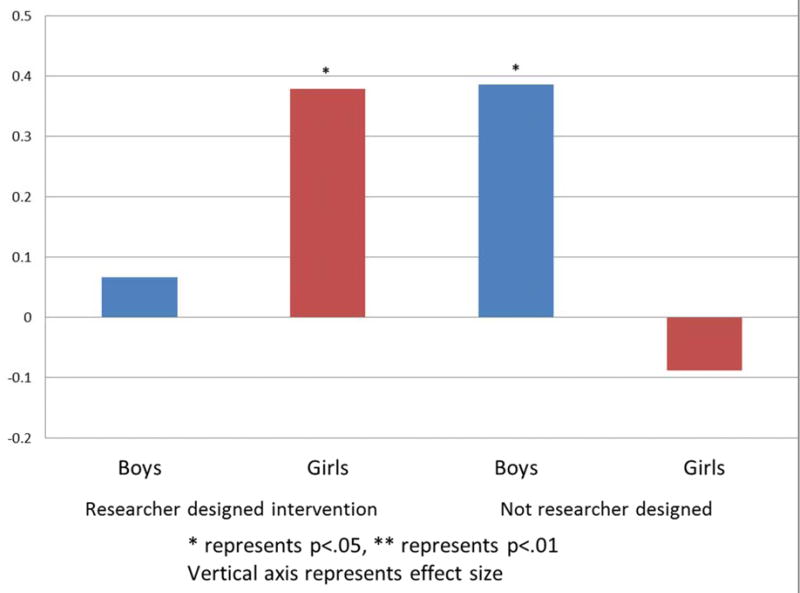

The most interesting interaction results come from the other school outcomes domain. Although only the nine studies contribute effect sizes, potentially reducing our ability to detect meaningful interactions, many of the interaction term coefficients are both large and significant. The pattern of effects for our three proxies of program quality (researcher designed program, use of a standardized curriculum, and satisfactory teacher:child ratio) are similar. In fact, they are identical for the program characteristics of being researcher designed and having a satisfactory teacher:child ratio, as these features are perfectly aligned in programs that assessed other school outcomes (the correlation between standardized curriculum and either researcher-designed program or satisfactory teacher: child ratio is .35).

Table 8 illustrates the pattern of effects for the researcher-designed (or satisfactory teacher:child ratio) by gender interaction terms. Each proxy for program quality had a sizable, significant and positive association with other school outcomes (ranging from .50 to .55,) indicating that these characteristics are associated with larger positive effect sizes for at least some important outcomes (even in the absence of positive main effects on achievement and cognition). In each case, boys in programs with these features had smaller ECE program impacts than girls in these programs, and less than boys in programs without these features. Conversely, when programs did not have these features that proxy for high quality programs, boys experienced larger program impacts than girls in terms of other school outcomes. Figure 2 shows an example of the interaction effects for one of the program quality characteristics—whether the intervention was designed by the researcher. Girls in researcher-designed programs experience a larger impact than boys in these programs, but boys show a larger impact than girls in programs that were not researcher designed.

Figure 2. Interaction Estimates by Program Characteristics for Other School Outcomes.

In programs where it was specified that improving behavior was a goal or if the program was conducted after 1976, boys had better other school outcomes than they did in programs in which this was not a goal or studies were conducted earlier, and better outcomes than girls in these programs. We also estimated a model in which the year the study began was measured as a continuous measure, and this model confirmed that studies conducted more recently produced larger gender differentials favoring boys on other school outcomes (results not shown). Finally, program impacts on other school outcomes favored girls for effect sizes that were administered more than 12 months after program completion.

There were far fewer interaction effects of program characteristics with gender for behavior impacts. Even having an explicit goal of improving children's behavior did not significantly predict whether children behavior and mental health improved in these data. None of the interactions for child behavior were statistically significant, and in most cases the coefficients were also quite small. Finally, with only three programs contributing outcomes to the adult outcome domain, we did not think an exploration of moderation by program characteristics was warranted, and in several instances there were insufficient numbers of programs or effect sizes to estimate such associations.

This bivariate look at how program characteristics affect gender differentials offers some insight into how program characteristics may affect gender differences in program impacts; however, as is evident from Table 2, these characteristics are often confounded. For this reason, we include all of the variables and interaction terms from Table 8 into one multivariate regression (Table 9). With only a small number of programs contributing effect sizes (21 for achievement and cognitive outcomes, and nine for other school outcomes), this endeavor is limited by low statistical power; we therefore approach it as an exploratory effort. In the case of achievement and cognitive outcomes, results suggest two main effects (researcher-designed studies produce larger effect sizes and effect sizes derived from measures administered twelve months or more after the end of the program produce are smaller), but none of the interaction terms are significant. This suggests that program features do not uniquely interact with gender to predict program impacts on achievement and cognitive outcomes.

Table 9. Multivariate Meta-Analysis Results by Domain and Gender Interactions.

| Cognitive and achievement | Other school outcomes | Child behavior and mental health | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | (SE) | Coefficient | (SE) | Coefficient | (SE) |

| Intercept | .07 | (.15) | -.20 | (.31) | .05 | (1.30) |

| Male | -.08 | (.06) | -.05 | (.44) | -.51 | (1.75) |

| Researcher designed | .44* | (.17) | .17 | (.36) | -.31 | (.69) |

| Male*Researcher designed | .00 | (.08) | -.20 | (.52) | .20 | (1.03) |

| Standardized curriculum | -.07 | (.10) | .61 | (.22) | .10 | (1.26) |

| Male*Standardized curr. | .09 | (.06) | -1.29** | (.31) | .51 | (1.68) |

| Satisfactory teacher:child ratio | -.06 | (.10) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Male*Satisfactory ratio | .01 | (.03) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Improve behavior | .04 | (.15) | -.11 | (.31) | .14 | (.08) |

| Male*Improve behavior | -.00 | (.06) | .58 | (.45) | -.07 | (.12) |

| Random assignment | .18 | (.12) | .22 | (.33) | -- | -- |

| Male*Random assignment | .03 | (.05) | -.50 | (.48) | -- | -- |

| After 1976 | .13 | (.12) | .31 | (.18) | -.09 | (1.30) |

| Male*After 1976 | .04 | (.06) | -.53* | (.25) | .50 | (1.74) |

| >12 months elapsed | -.11** | (.04) | -.21 | (.20) | -- | -- |

| Male*>12 months elapsed | .04 | (.05) | 1.06** | (.29) | -- | -- |

| Number of effect sizes | 441 | 98 | 36 | |||

Note.

represents p < .05

represents p < .01.

“Male” is a dummy variable equal to 1 for all-boys contrasts and 0 for all-girls contrasts. Each column represents one separate regression. Effect sizes with missing data are excluded from the analyses. Positive coefficients represent desirable outcomes, such as lower rates of special education referral or grade retention.

In the case of other school outcomes, we could not include both researcher-designed program and satisfactory teacher:child ratio because of their perfect correlation, so we omitted satisfactory teacher:child ratio from the regressions (but recognize that researcher-designed study represents both of these characteristics). Three of the interaction terms are large and statistically significant – standardized curriculum, after 1976, and whether the outcome was measured more than 12 months post-program. However, only the interaction between standardized curriculum and male is in the same direction as found in the bivariate models. These results suggest that girls fare better than boys in terms of impacts on other school outcomes when a standardized curriculum is part of the ECE program. Although in bivariate models, program impacts favored boys in programs with goals to improve behavior and favored girls in programs with random assignment, we do not find a statistically significant relationship in the multivariate models.

Discussion