Abstract

Congenital acinar dysplasia is a lethal, developmental lung malformation resulting in neonatal respiratory insufficiency. This entity is characterized by pulmonary hypoplasia and arrest in the pseudoglandular stage of development, resulting in the absence of functional gas exchange. The etiology is unknown, but a relationship with the disruption of the TBX4-FGF10 pathway has been described. There are no definitive antenatal diagnostic tests. It is a diagnosis of exclusion from other diffuse embryologic lung abnormalities with identical clinical presentations that are, however, histopathologically distinct.

Keywords: Embryology, Lung, Respiratory Insufficiency

INTRODUCTION

Congenital acinar dysplasia (AcDys) is a rare developmental abnormality of the lungs characterized by diffuse, bilateral defects of the pulmonary acini.1 AcDys belongs to a group of unusual neonatal lung disorders, along with congenital alveolar dysplasia and capillary alveolar dysplasia with misalignment of pulmonary veins. Histologically, the appearance of the lung at term is similar to the 16-week pseudoglandular phase with no or scarce alveolar spaces for gas exchange. The etiology of AcDys is unknown; however, a genetic component is proposed. AcDys is a diagnosis of exclusion in cases presenting with pulmonary hypoplasia. The prognosis is fatal with most babies dying within hours or days of birth from refractory respiratory insufficiency.2

CASE REPORT

The patient is a female newborn born at 39.5 weeks’ gestation to a 33-year-old healthy woman. The prenatal course was complicated with intrauterine growth restriction. The mother was admitted to the hospital due to late variable decelerations in the fetus’ heart rate. The newborn was delivered via induced vaginal delivery. Respiratory failure was immediately noted, and the newborn was placed on ventilation without success requiring intubation. A left-sided pneumothorax developed, and a chest tube was placed. Despite all efforts, the newborn died shortly after birth.

Autopsy findings

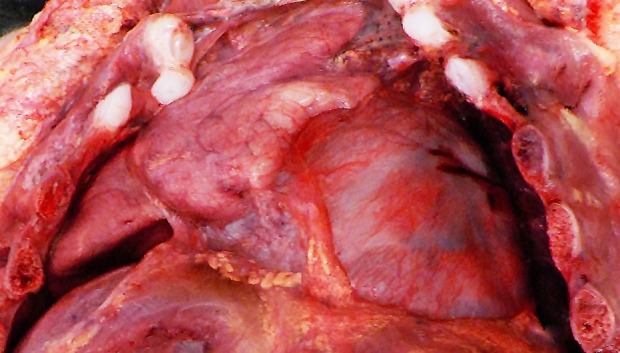

At autopsy, the right lung weighed 14 g, and the left lung weighed 12 g (normal for gestational age, right: 21 g; left: 18 g).3 The lungs appeared hypoplastic and firm (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Gross view of the hypoplastic right lung.

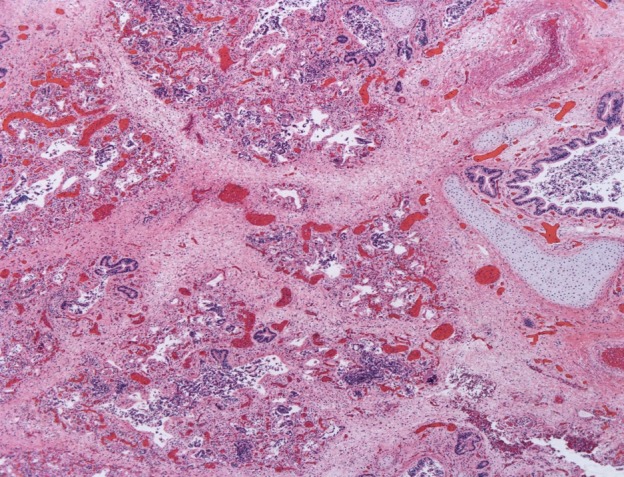

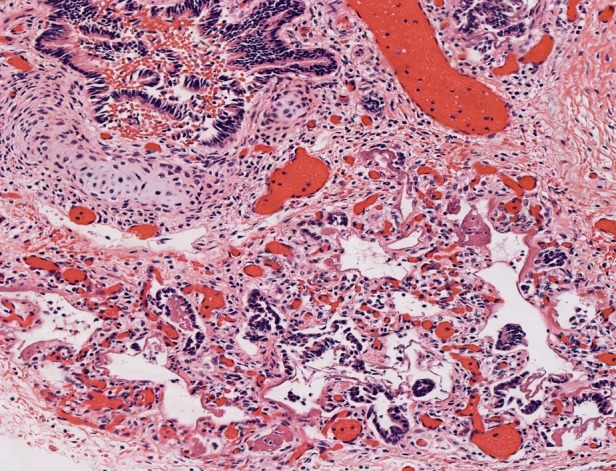

Lung hypoplasia is defined as the ratio of lung weight to body weight. The ratio is 0.012 for newborns at 28 weeks’ gestation or more and 0.015 for those of lower gestational age.4 In our case, taking into consideration the baby’s weight of 2670 g (normal for gestational age: 2501-2750 g)5 the ratio is 0.01. Microscopic examination of the lungs showed irregular tubules lined by pseudostratified to simple columnar epithelium with rare alveolar sacs consistent with the late pseudoglandular (pre-acinar) stage of development, hyaline membranes, and abundant septal fibrosis. The presence of immature cartilage formation around bronchial-like structures with appropriate accompanying vessels and normally-formed lymphatics were noted (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Photomicrograph of the lung parenchyma with striking septal fibrosis (H&E, 5X).

Figure 3. Photomicrograph of the lung showing irregular tubules lined by simple columnar epithelium with rare alveolar sacs and hyaline membranes (H&E, 20X).

These findings are consistent with the diagnosis of congenital acinar dysplasia. Additional autopsy findings were recent intraventricular hemorrhage and a small chest circumference of 28.8 cm (normal for gestational age: 33 ± 2.3 cm).5 A pertinent negative finding was that of no cardiac malformations.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of congenital acinar dysplasia is unknown and underreported, as the only definitive method of diagnosing AcDys is by autopsy. There are no specific prenatal tests, including fetal karyotype and imaging studies, which can help with the diagnosis. It has a high prevalence among female newborns (9:1 ratio).6

The etiology of AcDys is incompletely understood, with recent studies advocating for a disruption of the TBX4-FGF10 pathway. This genetic interaction is crucial in lung organogenesis, allowing necessary epithelial-stromal signaling for airway branching.7 In AcDys, there is a bilateral arrest of lung development between 8 and 16 weeks’ gestation during the pseudoglandular phase. During this phase, the bronchial tree develops up to the terminal bronchioles. In normal embryogenesis, this sequential branching leads to the formation of surrounding stroma, which culminates in respiratory units. If development stops at this phase, the lungs will show irregular bronchiolar structures without alveolar spaces. This results clinically in the failure to sustain functional gas exchange.2

The other two lethal developmental lung disorders, congenital alveolar dysplasia and capillary alveolar dysplasia with misalignment of pulmonary veins, show arrest between 18- and 24-weeks’ gestation during the canalicular phase. Acini, which encompass the respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and terminal sacs, and the capillary network begin to develop during this phase. The lining epithelium becomes progressively simple cuboidal to, in areas, flattened, and the amount of septal stroma begins to decrease.8 In addition, congenital alveolar dysplasia shows thickened septi without mature collagen and very large capillaries; while capillary alveolar dysplasia with misalignment of pulmonary veins shows thickened septi without capillaries, thick-walled pulmonary veins accompanying pulmonary arteries and dilated lymphatics. Clinically, however, it is not possible to differentiate these disorders from AcDys.2

CONCLUSION

Congenital acinar dysplasia is a malformation of the lungs resulting in respiratory insufficiency incompatible with life. It should be suspected in neonates with severe respiratory distress who do not respond to supportive treatment with mechanical ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). There are no definitive diagnostic tests which can be done prenatally. The recurrence risk is unknown, and there are no evidence-based management protocols for following pregnancies.2

Footnotes

How to cite: Oneto S, Poppiti RJ. Congenital acinar dysplasia: a lethal entity. Autops Case Rep [Internet]. 2019 Oct-Dec;9(4):e2019119. https://doi.org/10.4322/acr.2019.119

The authors retain an informed consent signed by the mother.

Financial support: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Rutledge JC, Jensen P. Acinar dysplasia: a new form of pulmonary maldevelopment. Hum Pathol. 1986;17(12):1290-3. 10.1016/S0046-8177(86)80576-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langenstroer M, Fanaian N, Attia S, Carlan SJ. Congenital acinar dysplasia: report of a case and review of literature. AJP Rep. 2013;3(1):9-12. 10.1055/s-0032-1329126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coppolette JM, Wolbach SB. Body length and organ weights of infants and children. Am J Pathol. 1933;9:55-70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert-Barness E, Debich-Spicer DE. Handbook of pediatric autopsy pathology. Totowa: Human Press; 2005. p. 258-64. 10.1385/1592596738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansen K, Sung CJ, Huang C, Pinar H, Singer DB, Oyer CE. Reference values for second trimester fetal and neonatal organ weights and measurements. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2003;6(2):160-7. 10.1007/s10024-002-1117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeBoer EM, Keene S, Winkler AM, Shehata BM. Identical twins with lethal congenital pulmonary airway malformation type 0 (acinar dysplasia): further evidence of familial tendency. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2012;31(4):217-24. 10.3109/15513815.2011.650284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karolak JA, Vincent M, Deutsch G, et al. Complex compound inheritance of lethal lung developmental disorders due to disruption of the TBX-FGF pathway. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104(2):213-28. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ernst LM, Ruchelli ED, Huff DS. Color atlas of fetal and neonatal histology. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 29-30. 10.1007/978-1-4614-0019-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]