Abstract

Objective

Oligomeric forms of amyloid β protein (oAβ) are believed to be principally responsible for neurotoxicity in Alzheimer disease (AD), but it is not known whether anti‐Aβ antibodies are capable of lowering oAβ levels in humans.

Methods

We developed an ultrasensitive immunoassay and used it to measure oAβ in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from 104 AD subjects participating in the ABBY and BLAZE phase 2 trials of the anti‐Aβ antibody crenezumab. Patients received subcutaneous (SC) crenezumab (300mg) or placebo every 2 weeks, or intravenous (IV) crenezumab (15mg/kg) or placebo every 4 weeks for 68 weeks. Ninety‐eight of the 104 patients had measurable baseline oAβ levels, and these were compared to levels at week 69 in placebo (n = 28), SC (n = 35), and IV (n = 35) treated patients.

Results

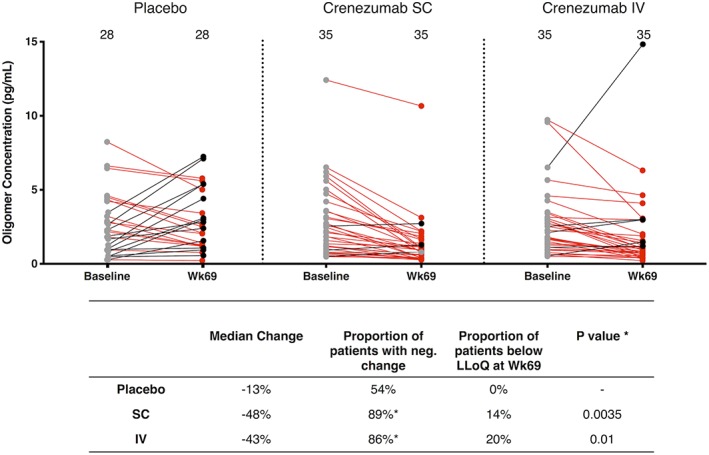

Among those receiving crenezumab, 89% of SC and 86% of IV patients had lower levels of oAβ at week 69 versus baseline. The difference in the proportion of patients with decreasing levels was significant for both treatment arms: p = 0.0035 for SC and p = 0.01 for IV crenezumab versus placebo. The median percentage change was −48% in the SC arm and −43% in the IV arm. No systematic change was observed in the placebo group, with a median change of −13% and equivalent portions with negative and positive change.

Interpretation

Crenezumab lowered CSF oAβ levels in the large majority of treated patients tested. These results support engagement of the principal pathobiological target in AD and identify CSF oAβ as a novel pharmacodynamic biomarker for use in trials of anti‐Aβ agents. ANN NEUROL 2019;86:215–224

Genetic, neuropathological, biochemical, and biomarker studies indicate that cerebral accumulation of amyloid β protein (Aβ) is an early and necessary event in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease (AD). The amyloid plaques that occur in all AD cases are in equilibrium with soluble oligomers of Aβ (oAβ), and these can activate microglia and injure neurons, including by inducing neurofibrillary tangles, the other hallmark lesion of AD.1, 2, 3 Among >50 active clinical trials, the most advanced efforts toward disease modification involve monthly or bimonthly infusions of anti‐Aβ monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). However, whether and to what extent such antibodies engage and alter oAβ levels in humans is unknown. This is because it has proven difficult to establish highly sensitive, oligomer‐selective assays capable of measuring the minute amounts of oAβ in human cerebrospinal fluid CSF; (reviewed in Yang et al4) and because of the paucity of longitudinal CSF specimens from patients treated with a relevant antibody.

Crenezumab is a humanized anti‐Aβ IgG4 in development for the treatment and prevention of AD. It binds monomeric and aggregated forms of Aβ, with the highest affinity for soluble oligomers, and it can block aggregation of monomers and induce disaggregation of existing Aβ aggregates in vitro.5, 6 Crenezumab is hypothesized to be neuroprotective by blocking the interaction of Aβ oligomers with neurons and promoting the removal of oligomers via microglial phagocytosis. Crenezumab has been evaluated for safety and efficacy in the ABBY7 and BLAZE8 phase 2 trials in patients with mild‐to‐moderate AD. In the ABBY trial, the primary and secondary endpoints (change in Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale [ADAS‐Cog12] and Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes, respectively) were not met, but prespecified exploratory analyses suggested a potential treatment effect in patients with mild AD treated with high‐dose crenezumab. Specifically, there was a reduction in decline on the ADAS‐Cog12, and the separation from placebo on this test was greatest in patients with the mildest clinical manifestations of AD.7 Based on these findings, the safety profile of this agent,7, 8 and the emerging recognition that anti‐Aβ therapy will likely work best through early intervention,9, 10 crenezumab is currently being evaluated presymptomatically as part of the Alzheimer's Prevention Initiative in autosomal dominant presenilin mutation carriers.11

In living humans, soluble Aβ monomers and oligomers can only be measured in CSF, not directly in the brain. However, changes in Aβ concentrations in CSF reflect changes in brain Aβ.12, 13 It was recently shown that CSF Aβ monomer concentrations increase under crenezumab treatment.7, 8 Given the pathogenic importance of oAβ in AD and the demonstrated preference of crenezumab for aggregated forms of Aβ, we asked whether crenezumab could target and alter oAβ levels in the CSF of subjects in the ABBY and BLAZE trials. We found that oAβ levels were significantly decreased in a high proportion of crenezumab‐treated patients, whereas no systematic change occurred in the placebo group. This first evidence of successful target engagement of Aβ oligomers in humans by a therapeutic agent suggests that quantifying CSF oAβ could be a useful pharmacodynamic and outcome biomarker in AD trials in general.

Patients and Methods

Trial Design and Demographic Details of Participants

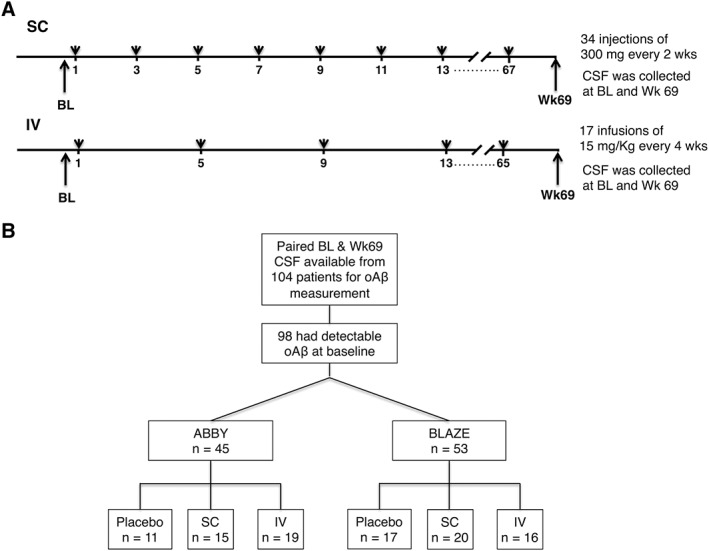

Specimens used in this analysis came from a representative subgroup of subjects participating in the ABBY (NCT01343966) and BLAZE (NCT01397578) phase II trials of crenezumab who had participated in longitudinal CSF sampling and had paired samples at baseline (BL) and week 69 available for oAβ measurement. The study design has been described,7, 8 and the administration regimens and patients contributing to this study are summarized in Figure 1, with demographic information in Tables 1 and 2, and a biomarker overview in Table 3. The main difference between ABBY and BLAZE was that patients in BLAZE needed to be amyloid positron emission tomography (PET)‐positive at screening, whereas ABBY did not require amyloid PET as an inclusion criterion. Patient ages (50–80 years), sex, and Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores were closely similar to those of the overall ABBY and BLAZE populations.7, 8 Both ABBY and BLAZE were sequentially enrolled, starting with the subcutaneous (SC) arm and then the intravenous (IV) arm in each trial. AD patients received 300mg crenezumab or placebo by SC injection every 2 weeks or 15mg/kg crenezumab or placebo by IV infusion every 4 weeks. Paired CSF samples taken at BL and week 69 were available from a total of 106 patients from these two highly similar studies. Of 104 patients in whom we measured CSF oAβ concentrations, 6 patients had undetectable oAβ levels at BL (see Fig 1B) and therefore were not considered further. Of the remaining 98 patients, 45 were from ABBY and 53 from BLAZE. CSF Aβ42 monomer levels were available from 105 of the 106 patients; 50 were from ABBY and 55 from BLAZE. Study protocols were approved by institutional review boards and complied with US Food and Drug Administration regulations, the International Council on Harmonization E6 Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, and state and federal laws (trial registration numbers: NCT01343966 and NCT01397578).

Figure 1.

Timeline of antibody injections and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) collections for Alzheimer disease patients in the ABBY and BLAZE trials. (A) Schematic of the identical dosing regimens in the ABBY and BLAZE studies. CSF samples were collected at baseline (BL; week 1) and week 69. (B) Schematic illustrating patient distribution by clinical trial and treatment. IV = intravenous; oAβ = oligomers of amyloid β; SC = subcutaneous.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics in Current Study

| Characteristic | 15mg/kg Crenezumab IV Every 4 Weeks, n = 37 | 300mg Crenezumab SC Every 2 Weeks, n = 37 | Placebo, n = 32 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr (SD) | 70.8 (6.9) | 68.1 (8) | 68.7 (7.7) |

| Sex, F (%) | 19 (51.4%) | 20 (54.1%) | 17 (53.1%) |

| MMSE mean score (SD) | 22.1 (2.9) | 22.2 (2.8) | 22.2 (2.4) |

| MMSE score 22–26, n (%) | 21 (56.8%) | 20 (54.1%) | 17 (53.1%) |

| APOE ε4 carriers, n (%) | 26 (70.3%) | 27 (73%) | 27 (84.4%) |

| ADAS‐Cog12 mean score (SD) | 27.6 (9.7) | 28.1 (9.7) | 27.1 (7.9) |

| CDR‐SB mean score (SD) | 4.1 (1.7) | 4.3 (2.0) | 4.2 (1.5) |

| ADCS‐ADL mean score (SD) | 68.2 (5.9) | 65.1 (11.1) | 67.4 (6.6) |

ADAS‐Cog12 = Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale; ADCS‐ADL = Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living Inventory; CDR‐SB = Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes; F = female; IV = intravenous; MMSE = Mini‐Mental State Examination; SC = subcutaneous; SD = standard deviation.

Table 2.

Patient Demographics of All Subjects Combined ABBY and BLAZE Studies

| Characteristic | 15mg/kg Crenezumab IV Every 4 Weeks, n = 198 | 300 mg Crenezumab SC Every 2 Weeks, n = 148 | Placebo, n = 176 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr (SD) | 71 (6.9) | 70.4 (7.1) | 70 (7.2) |

| Sex, F (%) | 106 (53.5%) | 80 (54.1%) | 92 (52.3%) |

| MMSE mean score (SD) | 21.7 (2.7) | 21.7 (2.7) | 21.5 (2.5) |

| MMSE score 22–26, n (%) | 101 (51%) | 70 (47.3%) | 82 (46.6%) |

| APOE ε4 carriers, n (%) | 139 (70.2%) | 100 (67.6%) | 124 (70.5%) |

| ADAS‐Cog12 mean score (SD) | 29.3 (9.3) | 28.4 (8.7) | 28.5 (8.8) |

| CDR‐SB mean score (SD) | 4.6 (2.1) | 4.6 (1.9) | 4.6 (2.1) |

| ADCS‐ADL mean score (SD) | 64.2 (10.4) | 64.6 (9.5) | 64.9 (10.1) |

ADAS‐Cog12 = Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale; ADCS‐ADL = Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living Inventory; CDR‐SB = Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes; F = female; IV = intravenous; MMSE = Mini‐Mental State Examination; SC = subcutaneous; SD = standard deviation.

Table 3.

Biomarker Overview

| 15mg/kg Crenezumab IV Every 4 Weeks | 300mg Crenezumab SC Every 2 Weeks | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Aβ oligomer level | |||

| n | 35 | 35 | 28 |

| Baseline, pg/ml (SD) | 2.7 (2.2) | 2.7 (2.5) | 2.6 (2.1) |

| Week 69, pg/ml (SD) | 1.9 (2.6) | 1.3 (1.8) | 2.9 (2.0) |

| Mean Aβ monomer level | |||

| n | 36 | 37 | 32 |

| Baseline, pg/ml (SD) | 615 (201) | 683 (234) | 647 (257) |

| Week 69, pg/ml (SD) | 694 (247) | 757 (249) | 589 (218) |

Aβ = amyloid β; IV = intravenous; SC = subcutaneous; SD = standard deviation.

Collection, Processing, Storage, and Handling of CSF

CSF was collected just prior to the first dose (BL) and again at week 69. Institutional review boards approved the collection protocols, and all donors provided informed consent for use of samples. CSF (10–12ml) was collected and stored as described.8 Samples (500μl) were thawed on the day of assay; 470μl of CSF was removed to a fresh tube, and 150μl of Standard Diluent (CAT# 02‐0485‐00; Millipore, Billerica, MA) was added to each.

oAβ Assay Antibodies, Aβ Peptide Standards, and Control CSF Specimens

Prior to labeling and use, antibodies were protein G purified. 1C22, used as the capture antibody, is a strongly Aβ aggregate‐preferring mouse mAb developed in the Walsh laboratory and described previously.14, 15 3D6, used as the detector antibody, is a mouse mAb specific for the Asp1‐containing N‐terminus of Aβ16, 17 and was from the hybridoma PTA5130 (ATCC, Manassas, VA). 1C22 was biotinylated using an SMC Capture Labeling Kit (Millipore), and the biotinylated 1C22 was allowed to bind to Dynabeads Myone Streptavidin C1 microparticles (MPs; Life Technologies, Eugene, OR) to yield 12.5μg of biotinylated 1C22 per milligram of MPs. This suspension was stored at 4°C pending use. 3D6 was labeled with fluorescein using an SMC Detection Labeling Kit (Millipore).

A preparation of synthetic human Aβ1‐42 peptide rich in prefibrillar aggregates and referred to as amyloid‐beta–derived diffusible ligands (ADDLs)18 was prepared exactly as described previously.4 Briefly, Aβ1–42 peptide (ERI Amyloid Laboratory, Oxford, CT) was treated with hexafluoroisopropanol and dried under a stream of nitrogen, and the film was dissolved in 20μl anhydrous dimethylsulfoxide before diluting 1:50 (vol/vol) in Hams F‐12 media. The resulting solution was incubated at 4°C for 48 hours and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes. The supernatant was chromatographed on a Superdex 75 10/300 GL gel filtration column eluted with 50mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.5. The void volume peak was collected, and the oAβ concentration was determined using the extinction coefficient ε275 = 1,361M−1cm−1.19 Thereafter, these ADDLs were aliquoted (5μl) into low‐binding tubes (Eppendorff, Hauppauge, NY), immediately frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C.

Erenna‐Based Aβ Oligomer Immunoassay

The Erenna Immunoassay System (Millipore) is based on single‐molecule counting technology and typically allows a 20‐ to 100‐fold increase in sensitivity over traditional enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays.20 To capture oligomers, a suspension of 1C22‐MP was diluted to 100μg/ml in Millipore assay buffer (50mM Tris‐HCl, pH 7.6, 150mM NaCl, 1% Triton X‐100, D‐desthiobiotin, 0.1% bovine serum albumin) and then 50μl was added to 150μl of either CSF, standard, or blank, each appropriately diluted in standard diluent, and incubated at 25°C for 2 hours. MPs were isolated with a magnet and washed in Erenna System Buffer (cat # 02‐0111‐03, Millipore). Fluorescein‐labeled 3D6 detector antibody (20μl, 100ng/ml) was then added to each well, and the complex was agitated for 1 hour at 25°C. Unbound 3D6 was removed by washing 4 times with Erenna System Buffer, and MPs were transferred to a new plate. Assay buffer was removed by aspiration, and fluorescein‐labeled 3D6 was released by shaking in Elution Buffer B (cat # 02‐0297‐00, Millipore; 10μl/well) for 10 minutes at 25°C. These eluates were transferred to 384‐well plates containing neutralization buffer (cat # 02‐0368‐00, Millipore; 10μl/well). Samples were drawn into an Erenna instrument and passed through a 100μm‐diameter capillary flow cell through which a laser was directed. When fluorophores pass through the interrogation space, they emit light that is measured. The output from the detector is a train of pulses, with each pulse representing 1 photon that was detected. In this way, 3 signal outputs can be obtained: detected events (low‐end signal), event photons (low‐ and medium‐end signal), and total photons (high‐end signal). We focused on detected events (DEs), generating standard curves from DE values using a 4‐parameter curve fit. All samples and standards were analyzed in quadruplicate.

The lower limit of reliable quantification (LLoQ) is defined as the lowest back‐interpolated standard that (1) provides a signal 2‐fold of background, (2) has a percentage coefficient of variance ≤20%, and (3) has a recovery of 100 ± 20%. ADDL standards we ran on 25 separate plates produced LLoQs ranging from 0.16 to 0.63pg/ml, with a median of 0.31pg/ml.

To avoid variance arising from plate‐to‐plate differences, BL and week 69 samples from the same patient were always measured in neighboring wells of the same plate. This allowed us to calculate robust estimates of change in oAβ for each pair (ie, week 0 vs week 69). CSF samples from placebo‐ and crenezumab‐treated patients from both BLAZE and ABBY were analyzed simultaneously. In all cases, the operator was blinded to sample identity, and the positioning of samples on each assay plate was determined by a separate investigator.

It should be noted that this Erenna oAβ ultrasensitive assay had been validated by us in detail, including by analyzing sample dilution linearity to reduce or eliminate matrix effects, spiking synthetic and natural (brain‐derived) Aβ oligomers into human CSF with good recovery, and documenting very low background signals after Aβ immunodepletion. The assay was also shown to have >26,000‐fold selectivity for synthetic oligomers (ADDLs) over monomers.4, 21 The intra‐assay variance ranges from 7 to 12% and the interassay variance is ~13%.

Measurement of Aβ(1–42) Monomers in CSF of ABBY and BLAZE Participants

Total (free and bound) CSF Aβ(1–42) monomers were measured using the Elecsys β‐Amyloid(1–42) immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany)22 as described.8

Statistical Analysis

Percentage changes were calculated by subtracting values at BL from values at week 69 and dividing it by the BL value. For oAβ, only patients with BL values above the LLoQ were included in the analysis. The proportion of patients with concentrations at week 69 falling below the LLoQ are also reported; for these patients, changes are calculated using the LLoQ but are therefore potentially underestimated. Given the larger proportion of samples below the LLoQs in the treated arms, our reported means and medians are therefore a conservative estimate of the oAβ‐lowering effect of crenezumab. To test for significant differences between the treatment arms, changes were classified into either positive or negative direction, which does not depend on the exact quantification of the change and allows for the inclusion of post‐BL LLoQs. Fisher exact test was used on these proportions. Analyses were conducted using the R statistical programming environment version 3.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Crenezumab Treatment Consistently Decreases CSF Aβ Oligomer Levels

CSF specimens collected at BL and week 69 were available from 104 trial subjects. Of these, 98 had BL oAβ values above the LLoQ (see Patients and Methods) of the oligomer assay (see Fig 1B). Among these 98 patients with measurable BL oAβ levels, 70 received crenezumab and 28 received placebo. Because the treatment protocols used in the BLAZE and ABBY studies were identical and samples were collected and archived in the same manner, we pooled data from each arm of the 2 trials. We found that 89% of the SC and 86% of the IV patients treated with crenezumab had lower levels of oAβ at week 69 than at BL (Fig 2). The median percentage change was −48% in the SC arm and −43% in the IV arm. Accordingly, in the crenezumab‐treated arms, a higher proportion of samples had values that had fallen below the LLoQ by week 69 (20% of IV and 14% of SC) than in placebo (0%); therefore, our reported means and medians represent a conservative estimate of the oAβ‐lowering effect of crenezumab. No systematic change occurred in the placebo group, with a median change of −13% and equivalent portions with negative and positive change (see Fig 2). The difference in the proportion of subjects with decreasing levels was significant for both treatment arms (p = 0.0035 for SC and p = 0.01 for IV crenezumab vs placebo).

Figure 2.

Pooled analysis of samples from the BLAZE and ABBY studies reveals that crenezumab treatment significantly lowers cerebrospinal fluid amyloid β oligomer (oAβ) levels. oAβ levels at baseline (BL) and week 69 are shown for the placebo, subcutaneous (SC), and intravenous (IV) groups. BL oAβ levels are shown as filled gray circles. Week 69 levels lower than their corresponding BL sample are in red, and those higher than their BL value are in black. Each symbol represents a single subject, and the BL and week 69 values for the same individual are connected by a straight line, the color of which indicates a negative (red) or positive (black) change. Values that did not change appreciably between baseline and week 69 are connected with a gray line. LLoQ = lower limit of reliable quantification.

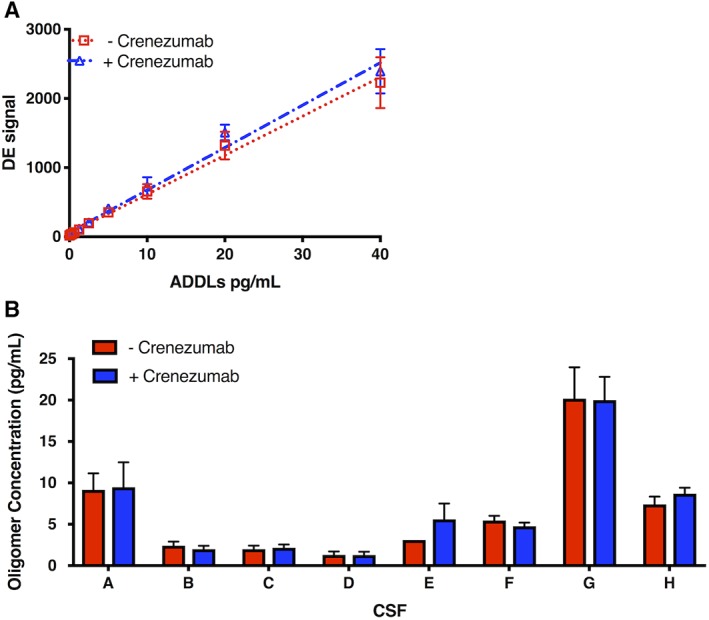

This treatment difference was not a consequence of crenezumab in the CSF interfering with the oAβ assay, as spiking crenezumab into multiple control human CSF samples did not alter the levels of endogenous oAβ (Fig 4B), nor did crenezumab alter the detection of the aggregated synthetic Aβ standard (ADDLs; see Fig 4A).

Figure 4.

Addition of crenezumab does not alter the detection of oligomers of amyloid β (oAβ). Crenezumab or a control IgG4 antibody was spiked into (A) the amyloid‐beta–derived diffusible ligand (ADDL) standard or (B) 7 different control cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples at final concentrations of 5μg/ml, and the oAβ levels were measured. Samples treated with crenezumab are in blue and those treated with control antibody are in red. Each symbol is the mean of technical quadruplicates. DE = detected event.

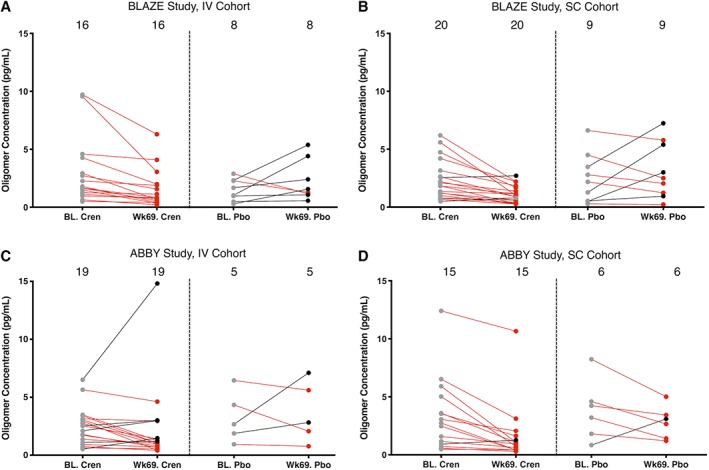

For the IV cohort of the BLAZE study, 16 received crenezumab and 8 received placebo (Fig 5A). Of the 16 patients receiving crenezumab, all had lower oAβ levels at week 69, whereas only 2 of the 8 placebo subjects had lower oAβ at week 69. A similar trend occurred in the BLAZE SC cohort; 17 of 20 crenezumab‐treated subjects had reduced oAβ levels, whereas only 5 of the 9 receiving placebo had lower oAβ levels at week 69. The IV and SC arms of the ABBY trial yielded results comparable to those of the BLAZE trial. Specifically, in the ABBY IV cohort 14 of 19 subjects treated with crenezumab had lower levels of oAβ, and 3 of 5 placebo subjects did. In the ABBY SC cohort, 14 of 15 crenezumab‐treated subjects had lower oAβ at week 69, as did 5 of 6 placebo subjects, although in the latter, the degree of reduction was generally modest.

Figure 5.

Crenezumab (Cren) treatment reduces levels of oligomers of amyloid β (oAβ) in cerebrospinal fluid. Results are presented by trial (A, B: BLAZE; C, D: ABBY) and by treatment arm (A, C: intravenous [IV]; B, D: subcutaneous [SC]). oAβ levels measured at baseline (BL) and week 69 are shown for each subject. Baseline oAβ levels are shown as filled gray circles; week 69 levels lower than their corresponding baseline sample are in red, and those with oAβ levels higher than their baseline are in black. Baseline and week 69 levels for the same individual are joined by a straight line, the color of which indicates a negative (red) or positive (black) change. Values that did not change appreciably between baseline and week 69 are connected with a gray line. Pbo = placebo.

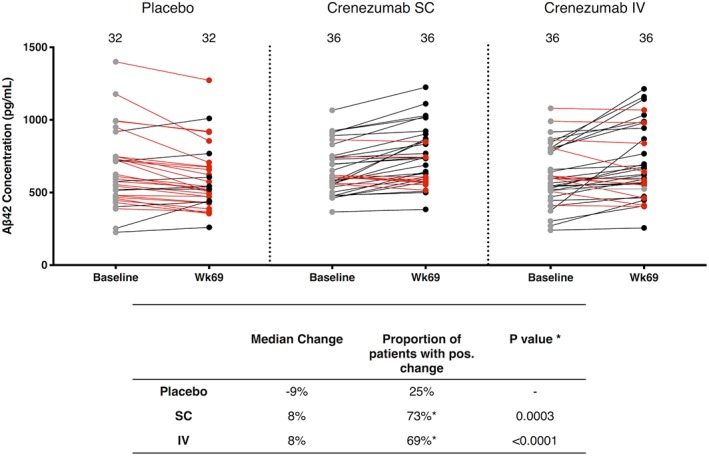

Crenezumab Treatment Increases CSF Aβ Monomer Levels

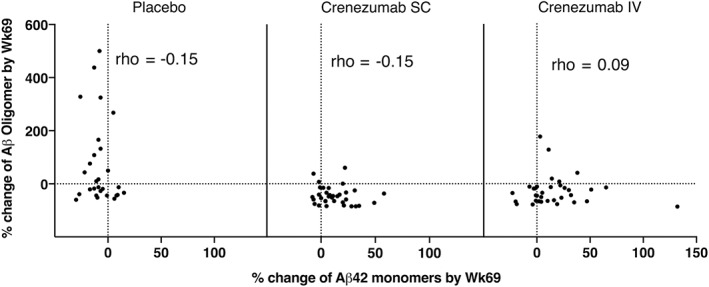

We also quantified CSF Aβ42 monomers using the Elecsys assay system.22 Aβ42 levels increased from BL to week 69 in 73% of patients treated with crenezumab SC and 69% of patients treated with crenezumab IV, whereas only 25% of patients on placebo showed an increase (SC vs placebo p < 0.0001; IV vs placebo p = 0.0003; Fig 3). The median percentage change between BL and week 69 on crenezumab was 8% in both the SC and IV groups. The opposite direction of change occurred in the placebo group, with a median change of −9%. These results are in striking contrast to the effect of crenezumab treatment on oligomers (see Fig 2); on average, crenezumab significantly decreased oAβ levels but significantly increased Aβ42 monomer levels. These opposing directional changes in the levels of monomers and oligomers suggest the possibility that crenezumab may induce some disaggregation of existing Aβ oligomers and/or may decrease the de novo generation of Aβ oligomers. However, there was no statistically significant correlation between the decrease in oligomers and increase in monomers among the crenezumab‐treated subjects (Fig 6). That crenezumab increased Aβ monomers but decreased Aβ oligomer levels further validates the oligomer specificity of our 1C22‐3D6 Erenna assay for oAβ.

Figure 3.

Crenezumab treatment increases cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 monomer levels. Baseline Aβ42 monomer levels are shown as filled gray circles. Week 69 levels lower than their corresponding baseline sample are in red, and those higher than their baseline value are in black. Each symbol represents a single subject, and the baseline and week 69 values for the same individual are joined by a straight line, the color of which indicates a negative (red) or positive (black) change. Values that did not change appreciably between baseline and week 69 are connected with a gray line. For Aβ42 monomers, only 1 patient showed levels above the upper limit of quantification and was omitted in this calculation of median change. IV = intravenous; SC = subcutaneous.

Figure 6.

No correlation between changes from baseline in cerebrospinal fluid amyloid β oligomer (oAβ) and Aβ42 monomer levels. Results are presented by treatment arm (placebo, crenezumab subcutaneous [SC], crenezumab intravenous [IV]). Changes from baseline in oAβ and Abeta monomer levels are not significantly correlated.

Discussion

Converging lines of evidence suggest that soluble, diffusible Aβ oligomers are a key pathogenic factor in AD and that reducing cerebral oAβ levels could have disease‐modifying benefit in patients with early stage disease.1, 2 However, measurement of Aβ oligomers is challenging due to their hydrophobicity and very low levels in CSF, in contrast to the abundant monomers that are readily quantifiable.4, 23 To our knowledge, the current work provides the first report that any anti‐Aβ therapy can reduce CSF oAβ levels in humans. We applied a highly sensitive and specific immunoassay that we developed to measure oAβ in the CSF of patients who had received crenezumab in rigorously controlled clinical trials. Our oAβ assay is robust and yields reproducible results when the same samples are analyzed on different days. Moreover, spiking CSF with crenezumab did not interfere with the detection of endogenous oAβ. The observed reduction is therefore due to increased clearance of oAβ and/or inhibition of de novo oligomer formation. The latter possibility is consistent with the finding that in most cases studied, crenezumab treatment was associated with increased Aβ42 monomer levels.

Levels of crenezumab in CSF at trough revealed broad overlap between the low‐dose (SC) and high‐dose (IV) subjects,7, 8 and this might explain why the decreases in oAβ and increases in Aβ42 levels were of roughly similar magnitude in both routes of administration, at least as regards this cohort of available CSF. The current study used a representative subgroup of the ABBY and BLAZE cohorts and had insufficient participants to determine whether reduction of oAβ is related to attenuation of cognitive decline. In a post hoc subgroup analysis of the full ABBY and BLAZE cohorts, one had seen a potential benefit of less cognitive decline in crenezumab‐treated mild (MMSE = 22–26 at entry) AD patients in the high‐dose IV treatment group,7, 8 but our study could obtain CSF from only 14 of these 70 mild subjects, and 13 of these 14 had oAb levels greater than the LLoQ of the assay. Due to the small sample size of only 13, this cohort did not provide sufficient power to reveal whether there was a greater decrease in this subgroup compared to placebo. It should be noted that 2 phase 3 clinical trials of crenezumab in early AD patients were recently halted after a futility analysis (https://www.roche.com/media/releases/med-cor-2019-01-30.htm). Although we document here a significant lowering of Aβ oligomer levels in the large majority of available CSF from the phase 2 trials, this has not yet been associated with an observed clinical benefit. There could be several reasons for the lack of clinical efficacy in the trials to date, including that amyloid‐lowering agents need to be administered presymptomatically to exert a significant benefit.

Recent evidence suggests that only a fraction of Aβ oligomers in AD brain tissue are neurotoxic21, 24 and that these toxic oAβ species are not equally targeted by different anti‐oAβ monoclonal antibodies.15 The consistent and significant decreases in rigorously measured oAβ we describe here indicate that crenezumab at doses of up to 15mg/kg IV is engaging in vivo with its planned target, cerebral oAβ; ongoing studies of crenezumab, testing a 4‐fold higher dose (60mg/kg IV) in presymptomatic familial AD subjects, could determine whether the degree of decrease in oAβ corresponds to the attenuation of cognitive decline. Similarly, it will be important to further assess how CSF oAβ levels change over the course of the disease, and whether the sensitive measurement of oAβ as performed here could aid in the diagnosis of early stage AD. Future studies with more frequent CSF sampling will be necessary to address these issues. Finally, in light of the apparent partial clinical benefits seen in some Aβ antibody trials,7, 8, 25, 26 the current findings recommend the use of high‐sensitivity oligomer‐selective immunoassays in other clinical trials of anti‐Aβ agents, several of which are underway or being planned.

Author Contributions

D.M.W., T.B., and D.J.S. conceived, designed, and supervised the research. T.Y., Y.D., B.O., and D.M. conducted the experiments and acquired the data. All authors analyzed the data and helped prepare figures. V.S. and C.R. performed statistical analyses. D.M.W., T.B., and D.J.S. wrote the manuscript.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

V.S., C.R., and T.B. are employees of Genentech, a member of the Roche Group. Crenezumab is under development by Roche. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging grants AG006173 and AG015379 (D.J.S.) and AG046275 (D.M.W.), by the Marr Family Foundation Fund at Brigham and Women's Hospital, and by the Harvard NeuroDiscovery Center through a major gift from Richard and Nancy Moskovitz.

We thank Dr R. Sperling for providing control CSF.

Contributor Information

Dominic M. Walsh, Email: dwalsh3@bwh.harvard.edu.

Dennis J. Selkoe, Email: dselkoe@bwh.harvard.edu.

References

- 1. Cline EN, Bicca MA, Viola KL, Klein WL. The amyloid‐beta oligomer hypothesis: beginning of the third decade. J Alzheimers Dis 2018;64:S567–S610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, et al. Amyloid‐beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med 2008;14:837–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jin M, Shepardson N, Yang T, et al. Soluble amyloid beta‐protein dimers isolated from Alzheimer cortex directly induce Tau hyperphosphorylation and neuritic degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108:5819–5824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang T, O'Malley TT, Kanmert D, et al. A highly sensitive novel immunoassay specifically detects low levels of soluble Abeta oligomers in human cerebrospinal fluid. Alzheimers Res Ther 2015;7:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adolfsson O, Pihlgren M, Toni N, et al. An effector‐reduced anti‐beta‐amyloid (Abeta) antibody with unique abeta binding properties promotes neuroprotection and glial engulfment of Abeta. J Neurosci 2012;32:9677–9689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ultsch M, Li B, Maurer T, et al. Structure of crenezumab complex with Abeta shows loss of beta‐hairpin. Sci Rep 2016;6:39374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cummings JL, Cohen S, van Dyck CH, et al. ABBY: a phase 2 randomized trial of crenezumab in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2018;90:e1889–e1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salloway S, Honigberg LA, Cho W, et al. Amyloid PET and CSF results from a crenezumab anti‐amyloid‐beta antibody double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, randomized phase II study in mild‐to‐moderate Alzheimer's disease (BLAZE). Alzheimers Res Ther 2018;10:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sperling RA, Jack CR Jr, Aisen PS. Testing the right target and right drug at the right stage. Sci Transl Med 2011;3:111cm33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sperling RA, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, et al. The A4 study: stopping AD before symptoms begin? Sci Transl Med 2014;6:228fs13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Doody R. Developing disease‐modifying treatments in Alzheimer's disease—a perspective from Roche and Genentech. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2017;4:264–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lu Y, Riddell D, Hajos‐Korcsok E, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid amyloid‐beta (Abeta) as an effect biomarker for brain Abeta lowering verified by quantitative preclinical analyses. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2012;342:366–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med 2012;367:795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mably AJ, Liu W, Mc Donald JM, et al. Anti‐Abeta antibodies incapable of reducing cerebral Abeta oligomers fail to attenuate spatial reference memory deficits in J20 mice. Neurobiol Dis 2015;82:372–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jin M, O'Nualllain B, Hong W, et al. An in vitro paradigm to assess potential anti‐Aß antibodies for Alzheimer's disease. Nat Commun 2018;9:2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johnson‐Wood K, Lee M, Motter R, et al. Amyloid precursor protein processing and Aß42 deposition in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997;94:1550–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feinberg H, Saldanha JW, Diep L, et al. Crystal structure reveals conservation of amyloid‐beta conformation recognized by 3D6 following humanization to bapineuzumab. Alzheimers Res Ther 2014;6:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, et al. Diffusible, nonfribrillar ligands derived from Aß1‐42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95:6448–6453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O'Malley TT, Oktaviani NA, Zhang D, et al. Abeta dimers differ from monomers in structural propensity, aggregation paths and population of synaptotoxic assemblies. Biochem J 2014;461:413–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Todd J, Freese B, Lu A, et al. Ultrasensitive flow‐based immunoassays using single‐molecule counting. Clin Chem 2007;53:1990–1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang T, Li S, Xu H, et al. Large soluble oligomers of amyloid beta‐protein from Alzheimer brain are far less neuroactive than the smaller oligomers to which they dissociate. J Neurosci 2017;37:152–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bittner T, Zetterberg H, Teunissen CE, et al. Technical performance of a novel, fully automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay for the quantitation of beta‐amyloid (1‐42) in human cerebrospinal fluid. Alzheimers Dement 2016;12:517–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Savage MJ, Kalinina J, Wolfe A, et al. A sensitive abeta oligomer assay discriminates Alzheimer's and aged control cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurosci 2014;34:2884–2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hong W, Wang Z, Liu W, et al. Diffusible, highly bioactive oligomers represent a critical minority of soluble Abeta in Alzheimer's disease brain. Acta Neuropathol 2018;136:19–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sevigny J, Chiao P, Bussiere T, et al. The antibody aducanumab reduces Abeta plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Nature 2016;537:50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Swanson CJ, Zhang Y, Dhadda S, et al. Treatment of early AD subjects with BAN2401, an antiti‐Aß protofibril monoclonnal antibody, significantly clears amyloid plaque and reduces clinical decline. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer's Association International Conference; July 22–26, 2018; Chicago, IL.