Abstract

Risankizumab, a humanized immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody, selectively inhibits interleukin‐23, a key cytokine in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, by binding to its p19 subunit. In SustaIMM (ClinicalTrials.gov/NCT03000075), a phase 2/3, double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled study, Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (n = 171) were stratified by bodyweight and concomitant psoriatic arthritis and randomized 2:2:1:1 to 75 mg risankizumab, 150 mg risankizumab, placebo with cross‐over to 75 mg risankizumab and placebo with cross‐over to 150 mg risankizumab. Dosing was at weeks 0, 4, 16, 28 and 40, with placebo cross‐over to risankizumab at week 16. The primary end‐point was 90% or more improvement from baseline in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI‐90) at week 16 for risankizumab versus placebo. Missing data were imputed as non‐response. All primary and psoriasis‐related secondary end‐points were met for both risankizumab doses (P < 0.001). At week 16, PASI‐90 responses were significantly higher in patients receiving 75 mg (76%) or 150 mg (75%) risankizumab versus placebo (2%). Corresponding response rates were 86%, 93% and 10% for static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA) score of clear/almost clear; 90%, 95% and 9% for PASI‐75; and 22%, 33% and 0% for PASI‐100, with significantly higher responses for both risankizumab doses versus placebo. Through week 52, PASI and sPGA responses increased or were maintained and treatment‐emergent adverse events were comparable across treatment groups. Both doses of risankizumab were superior to placebo in treating patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. The safety profile was consistent with previous risankizumab trials, with no new or unexpected safety findings.

Keywords: interleukin‐23, Japanese patient, plaque psoriasis, psoriasis, risankizumab

Introduction

Psoriasis, an immune‐mediated skin disease typically characterized by chronic inflammatory skin lesions having well‐demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques, affects 0.3% of the Japanese population.1, 2 Psoriasis may also have systemic inflammatory involvement and is associated with a number of comorbid diseases, including psoriatic arthritis, gastrointestinal disease, cardiometabolic disease and infection.3 Several studies have demonstrated clinical benefits of treatment with biologics in Japanese patients with plaque psoriasis2, 4, 5, 6 and a number of biologics have been approved in Japan as treatments for patients with psoriasis and an inadequate response to conventional therapies,7 including inhibitors of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α, interleukin (IL)‐17, IL‐12/23 and IL‐23.8

Interleukin‐23 is a key cytokine in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.9 Produced by dendritic cells and macrophages, IL‐23 is a heterodimer composed of a unique p19 subunit and an associated p40 subunit shared with IL‐12.10, 11 IL‐23 regulates the activation and maintenance of T‐helper (Th)17 cells, which leads to an inflammatory cytokine cascade, causing keratinocyte hyperproliferation and recruitment of immune cells into skin lesions.12

Risankizumab is a novel humanized immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 monoclonal antibody that selectively inhibits IL‐23 by binding to its p19 subunit,13 thereby avoiding the IL‐12/Th1 axis, which is blocked by IL‐12/23 inhibitors (e.g. ustekinumab) that target the p40 subunit.14 Efficacy data from phase 3 clinical trials have demonstrated significantly higher proportions of patients with 90% or more and 100% improvement from baseline in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), skin clearance (static Physician Global Assessment [sPGA] scores of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear]), and better quality of life (Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI] of 0 or 1 [no effect on patient's life]) with risankizumab compared with placebo, adalimumab or ustekinumab in those with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.15, 16, 17

The SustaIMM study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT03000075) conducted in Japan evaluated the efficacy and safety of two different dose regimens of risankizumab in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. Here, we report results through 52 weeks of treatment.

Methods

Study design

In this double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled, two‐part study of risankizumab, patients were randomized 2:2:1:1 to receive risankizumab 75 mg, risankizumab 150 mg, placebo with cross‐over to risankizumab 75 mg or placebo with cross‐over to risankizumab 150 mg. Randomization was stratified according to concomitant psoriatic arthritis at baseline (yes vs no) and bodyweight (≤90 vs >90 kg). The study consisted of a 2–6‐week screening period followed by a 16‐week treatment period, with dosing at weeks 0 and 4 (part A), and then a 36‐week treatment period with dosing at weeks 16, 28 and 40 (part B; Fig. 1). All patients initially receiving placebo began receiving risankizumab 75 or 150 mg at 16 weeks. Patients completing part B were eligible to enroll in an open‐label extension study.

Figure 1.

Study design.

An independent ethics committee/institutional review board approved the study protocol and all subsequent amendments. The study was conducted in accordance with International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines, Japanese GCP regulations and the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent before study participation.

Patients

Patients aged 20 years or older with chronic plaque psoriasis diagnosed 6 months or more before first administration of the study drug were eligible for participation if they had stable moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis (with or without psoriatic arthritis) with involved body surface area of 10% or more, PASI of 12 or more and sPGA of 3 or more; were candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy for psoriasis treatment; had no known chronic or relevant acute infections, including active tuberculosis, HIV or viral hepatitis; and had no documented active or suspected malignancy or history of malignancy within 5 years before screening, with the exception of appropriately treated basal or squamous cell carcinoma of the skin or in situ carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Patients with drug‐induced psoriasis, guttate, erythrodermic or pustular psoriasis, or any other active inflammatory disease that could have interfered with study assessments were ineligible for enrollment, as were women who were pregnant, breast‐feeding or planning to become pregnant. Women of child‐bearing potential were required to use highly effective methods of birth control. Patients were ineligible for study participation if they had had prior exposure to the study drug; enrolled in or had completed another investigational study within 30 days of screening; undergone major surgery 12 weeks or less before randomization; or surgery was planned within 12 months after screening. Additional exclusion criteria included history of allergy or hypersensitivity to a systematically administrated biologic agent or its excipients and evidence of a current or previous disease or medical condition other than psoriasis that investigators believed would interfere with study participation.

End‐points

The primary end‐point was 90% or more improvement from baseline in PASI (PASI‐90) at week 16. Secondary and other pre‐specified end‐points included PASI‐90 at week 52, achievement of 75% or more improvement from baseline PASI (PASI‐75) at weeks 16 and 52, 100% improvement from baseline PASI (PASI‐100) at weeks 16 and 52, an sPGA score of 0 or 1 at weeks 16 and 52, a DLQI of 0 or 1 at weeks 16 and 52, absolute PASI of less than 3 at all visits, percentage change from baseline in PASI at all visits, and achievement of American College of Rheumatology (ACR)‐20 response at weeks 16 and 52 in the subset of patients with psoriatic arthritis.

Assessments

Efficacy assessments of skin severity were performed using PASI18 and sPGA scores. The sPGA is a 5‐point composite score, ranging from 0 (clear; no psoriasis) to 4 (severe scaling, discoloration and thickening of lesions) based on the physician's assessment of the average thickness, erythema and scaling of all psoriatic lesions. Quality of life assessment was performed using the DLQI, a self‐administrated 10‐item questionnaire, with the effect of skin problems rated from 0 (not relevant/not at all) to 3 (very much) for each item; the total DLQI may range from 0 (no effect) to 30 (significant impairment).19 All patients with a medical history of psoriatic arthritis were evaluated for psoriatic arthritis diagnosis based on ClASsification of Psoriatic ARthritis (CASPAR) criteria. Efficacy assessments of psoriatic arthritis were performed using ACR criteria.

Safety was assessed descriptively based on adverse events (AEs; coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 21.0), serious AEs and clinical laboratory values. Severity of AEs was graded based on the Rheumatology Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0. All AEs described were considered treatment‐emergent AEs, defined as any event with an onset that was after the first dose of study drug and within 105 days after the last dose of study drug in the analysis period. Potentially clinically important chemistry values were defined as having a National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events toxicity criteria grade of 3 or more, with a value on treatment greater than the baseline value.

Statistical analysis

For all non‐binary end‐points, last observation carried forward was used for missing data. For all binary end‐points, missing data were imputed as non‐response. For all primary and secondary end‐points, differences in proportion of patients responding in the risankizumab treatment arms versus the placebo arm were calculated using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test adjusted for randomization factors of baseline concomitant psoriatic arthritis and bodyweight (≤90 vs >90 kg). For any stratum containing zero count, 0.1 was added to each cell. Within each stratum, the P‐value was calculated based on χ2‐test (or Fisher's exact test if ≥25% of cells had an expected cell count of <5). The study was powered to show a benefit of risankizumab over placebo for the primary end‐point, PASI‐90 at week 16. With a two‐sided significance level of 5% and an assumed response rate of 65% for risankizumab versus 5% for placebo, it was determined that a sample size of 17 patients per treatment arm would provide 95% power for each comparison and an overall power of at least 90%.

Results

Patient disposition and characteristics

Between December 2016 and May 2017, 171 patients were enrolled in the study (risankizumab 75 mg, n = 58; risankizumab 150 mg, n = 55, placebo, n = 58; Fig. 1). All patients receiving risankizumab and 54 (93%) patients receiving placebo completed part A of the study (Fig. 2); four patients receiving placebo discontinued because of an AE of worsening of disease. Most patients receiving risankizumab 75 or 150 mg in part A continued on their respective doses in part B (risankizumab 75 mg, n = 56; risankizumab 150 mg, n = 54) and completed part B; two patients receiving risankizumab 75 mg and one patient receiving risankizumab 150 mg discontinued because of an AE of worsening of disease and were not treated in part B. All patients who completed part A in the placebo arm were switched to either risankizumab 75 mg (n = 27) or risankizumab 150 mg (n = 27) for part B of the study and completed part B, with the exception of one patient receiving risankizumab 150 mg who discontinued because of an AE (dermatitis).

Figure 2.

Patient disposition. AE, adverse event.

Baseline characteristics were generally similar across treatment groups (Table 1). Mean (standard deviation) ages were 51.5 (12.3), 53.3 (11.9), and 50.9 years (11.2) among patients receiving risankizumab 75 mg, risankizumab 150 mg and placebo, respectively, and most patients were men. Fewer than 20% of patients in any treatment group had psoriatic arthritis or severe psoriasis as assessed by sPGA. The mean affected body surface area was greater in the risankizumab groups, with a significant difference noted for risankizumab 75‐mg group versus the placebo group (P < 0.05). A minority of patients had received prior biologic treatment (14–29%), including TNF inhibitors (5–11%).

Table 1.

Baseline patient demographics and disease characteristics

| Characteristic | Risankizumab | Placebo, n = 58 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 75 mg, n = 58 | 150 mg, n = 55 | ||

| Age, years | 51.5 (12.3) | 53.3 (11.9) | 50.9 (11.2) |

| Men, n (%) | 48 (83) | 50 (91) | 45 (78) |

| Bodyweight (kg) | 73.0 (17.2) | 74.1 (16.2) | 75.1 (17.7) |

| Weight ≤90 kg, n (%) | 50 (86) | 48 (87) | 49 (84) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.2 (5.1) | 26.4 (5.3) | 26.7 (5.4) |

| PASI | 26.9 (9.4) | 26.3 (11.7) | 24.0 (9.1) |

| BSA | 41.6 (20.9)* | 40.5 (22.7) | 33.2 (19.0) |

| PsA, n (%) | 11 (19) | 5 (9) | 7 (12) |

| DLQI | 11.2 (5.4) | 10.4 (5.4) | 9.7 (5.8) |

| sPGA 4 (severe), n (%) | 7 (12) | 9 (16) | 4 (7) |

| ACR components, n | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Pain VAS | 72.4 | 44.3 | 40.0 |

| Patient Global Assessment, VAS | 72.2 | 60.0 | 36.0 |

| Investigator's Global Assessment VAS | 87.8 | 44.3 | 61.3 |

| CRP, mg/L | 11.70 | 2.32 | 4.60 |

| TJC‐68 | 22.0 | 12.3 | 4.3 |

| SJC‐66 | 15.4 | 4.0 | 3.3 |

| Any prior biologic, n (%) | 8 (14) | 16 (29) | 14 (24) |

| Prior TNFi, n (%) | 3 (5) | 6 (11) | 5 (9) |

| Prior non‐TNFi, n (%) | 7 (12) | 13 (24) | 10 (17) |

Data are mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise noted. ACR, American College of Rheumatology, BMI, body mass index; BSA, percentage affected body surface area; CRP, C‐reactive protein; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; sPGA, static Physician Global Assessment; TJC‐68, 68‐joint tender joint count; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; SJC‐66, 66‐joint swollen joint count; VAS, visual analog scale, 0–100 mm. *P < 0.05 vs placebo.

Efficacy

Primary end‐point

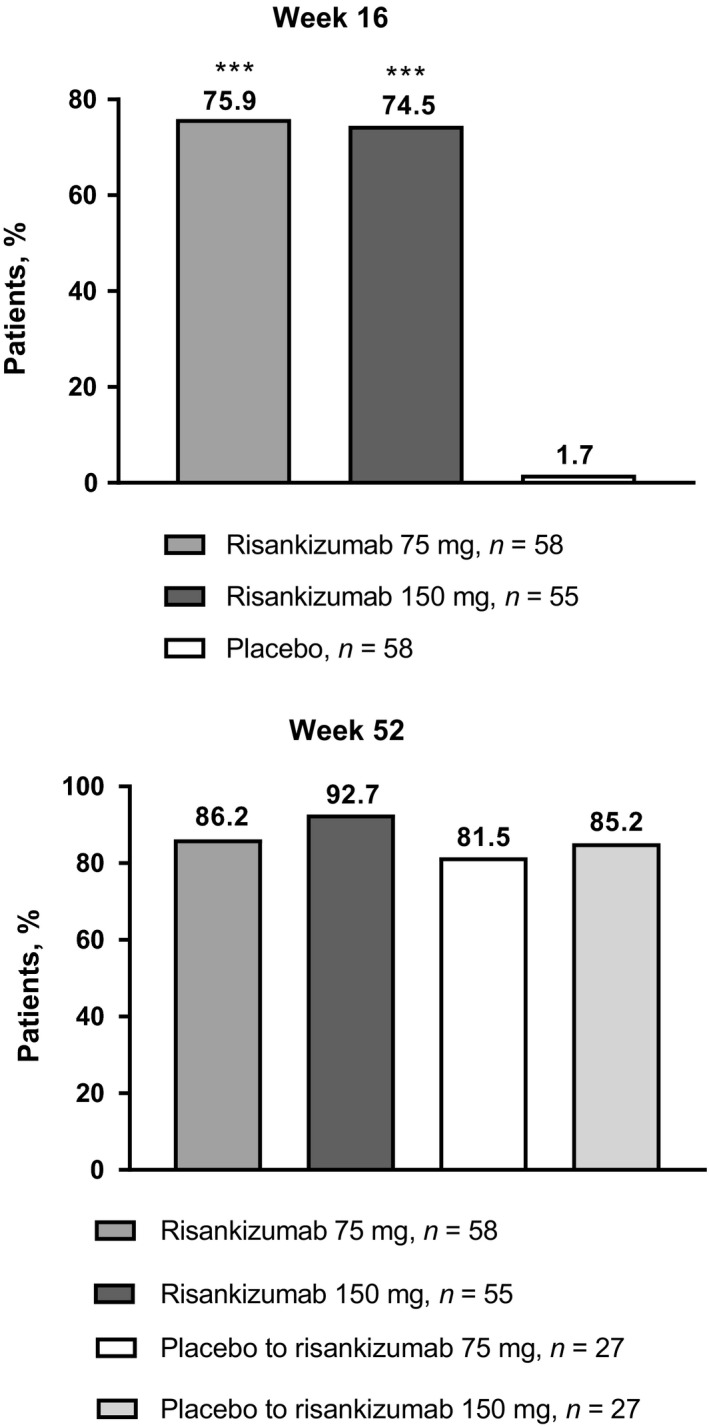

Risankizumab 75 and 150 mg were superior versus placebo for the primary end‐point of PASI‐90 at 16 weeks (75.9% and 74.5% vs 1.7%, respectively; P < 0.001; Fig. 3). Among patients with psoriatic arthritis (n = 23), PASI‐90 responses at 16 weeks were achieved by 8 of 11 (72.7%), 5 of 5 (100%) and 0 of 7 patients receiving risankizumab 75 mg, risankizumab 150 mg and placebo, respectively (P < 0.05; Fig. S1). In patients without psoriatic arthritis (n = 148), PASI‐90 responses at 16 weeks were achieved by 32 of 40 (80.0%), 30 of 43 (69.8%) and 1 of 43 (2.3%) patients receiving risankizumab 75 mg, risankizumab 150 mg and placebo with baseline weight of 90 kg or less, respectively (P < 0.001) and by 4 of 7 (57.1%), 6 of 7 (85.7%) and 0 of 8 patients receiving risankizumab 75 mg, risankizumab 150 mg and placebo with baseline weight of more than 90 kg, respectively (P < 0.05; Fig. S1).

Figure 3.

Percentage of patients with PASI‐90 responses at weeks 16 and 52. PASI‐90, 90% or more improvement from baseline in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index. ***P < 0.001 vs placebo.

Secondary end‐points

Response rates for patients receiving risankizumab 75 and 150 mg were significantly higher versus placebo for PASI‐75 (89.7% and 94.5% vs 8.6%, respectively; P < 0.001) and PASI‐100 (22.4% and 32.7% vs 0%; P < 0.001) at week 16 (Fig. 4), with higher PASI‐100 response rates among patients receiving risankizumab 150 mg versus 75 mg. An sPGA score of 0 or 1 was achieved by 86.2% and 92.7% versus 10.3% at 16 weeks (P < 0.001; Fig. 4). At week 52, 85% or more of patients in all risankizumab treatment groups achieved an sPGA score of 0 or 1.

Figure 4.

sPGA 0/1, PASI‐75, PASI‐100 and DLQI 0/1 responses at weeks 16 and 52. DLQI 0/1, Dermatology Life Quality Index showing no effect on patient's life; PASI‐75/PASI‐100, 75% or more/100% improvement from baseline in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; sPGA 0/1, static Physician Global Assessment of clear/almost clear. ***P < 0.001 vs placebo.

Through week 52, PASI‐90 and ‐100 responses continued to increase among patients continuously treated with risankizumab, with significant responses (vs placebo) observed earlier with risankizumab 150‐mg dosing compared with 75‐mg dosing (Fig. 5). PASI‐90 and ‐100 responses at week 52 were achieved by 86.2% and 43.1% of patients in the risankizumab 75‐mg group, respectively, and 92.7% and 41.8% of patients in the risankizumab 150‐mg group, respectively. Significant PASI‐90 and ‐100 responses were observed as early as week 4 and week 8 in the risankizumab 150‐mg group and week 8 and week 12 in risankizumab 75‐mg group, respectively. In the risankizumab 75‐mg and 150‐mg dose groups, PASI mean absolute percentage improvement from baseline was 58.8% and 57.4% (P < 0.001 vs placebo for each) at week 4 and 96.7% and 95.9% (P < 0.001 vs placebo for each) at week 16, respectively. PASI responses increased from week 16 to week 52 among patients receiving placebo who were reassigned to receive risankizumab from week 16 onward (Fig. S2). Additionally, approximately 90% of patients receiving risankizumab achieved PASI of less than 3 (Fig. S3).

Figure 5.

Changes in the rates of clinical response over time, measured as PASI‐90 and ‐100. PASI‐90/PASI‐100, 90% or more/100% improvement from baseline in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 vs placebo.

Among 23 patients diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis using the CASPAR criteria at baseline, ACR‐20 responses were measured for 11 patients who were treated at selected study sites. Although the number of patients was small and patients in the risankizumab 75‐mg group appeared to have more severe disease (as evidenced by baseline assessments and higher mean C‐reactive protein, Table 1), ACR‐20 was numerically higher in the risankizumab 75‐mg and 150‐mg groups versus the placebo group at week 16 (2 of 5 [40.0%] and 1 of 3 [33.3%] vs 0 of 3 [0%], respectively; P > 0.05) and sustained efficacy was confirmed until week 52 (six of 11 [55.0%] of all patients).

Patient‐reported outcomes

Significantly higher proportions of patients achieved a DLQI of 0 or 1 with risankizumab 75 and 150 mg versus placebo at week 16 (62.1% and 58.2% vs 5.2%, respectively; P < 0.001; Fig. 4). At week 52, DLQI 0/1 response rates among patients continuously receiving risankizumab 75 and 150 mg were 75.9% and 80.0%, respectively. DLQI 0/1 response rates among patients previously receiving placebo who were switched to risankizumab 75 and 150 mg increased from week 16 to 52, reaching 66.7% and 81.5%, respectively, at week 52.

Safety

Treatment‐emergent AE rates were comparable across treatment groups through week 52 (Tables 2,3). During the first 16 weeks of the study (part A), 30 (52%), 31 (56%), and 33 (57%) patients experienced an AE, and two (3%), two (4%) and one (2%) patient experienced a serious AE in the risankizumab 75‐mg, risankizumab 150‐mg and placebo groups, respectively. Three patients receiving risankizumab (75 mg, n = 2 [3%]; 150 mg, n = 1 [2%]) discontinued treatment because of an AE versus four patients (7%) in the placebo group. A single patient treated with risankizumab 150 mg experienced a major adverse cardiac event (acute myocardial infarction; the patient continued to receive risankizumab), and one patient from the placebo group had a serious infection. During part B, 35 (63%), 31 (57%), 18 (67%), and 23 (85%) patients in the risankizumab 75‐mg, risankizumab 150‐mg, placebo to risankizumab 75‐mg, and placebo to risankizumab 150‐mg groups experienced an AE, respectively, and four patients (risankizumab 75 and 150 mg, n = 1 [2%] each; placebo to risankizumab 75 mg, n = 2 [7%]) experienced a serious AE. One patient had a treatment‐emergent malignant tumor (rectal carcinoma) in the placebo to risankizumab 75‐mg group, and one patient in the placebo to risankizumab 150‐mg group discontinued treatment because of an AE (dermatitis). There were no reported serious hypersensitivity reactions, tuberculosis or deaths across all treatment groups during parts A and B of the study. Among patients receiving risankizumab across all treatments groups (n = 167), treatment‐emergent AEs reported by 5% or more of patients included nasopharyngitis (n = 49 [29%]) and back pain (n = 9 [5%]). Twenty patients met criteria for potentially clinically important chemistry values during risankizumab treatment, including increased γ‐glutamyltransferase (grade 3, n = 5 [3%]; grade 4, n = 1 [0.6%]), hyperglycemia (grade 3, n = 2 [1%]) and hypertriglyceridemia (grade 3, n = 9 [5%]; grade 4, n = 3 [2%]).

Table 2.

Treatment‐emergent adverse events during part A of the study

| TEAE,† n (%) | Risankizumab 75 mg, n = 58 | Risankizumab 150 mg, n = 55 | Placebo, n = 58 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any AE | 30 (52) | 31 (56) | 33 (57) |

| Drug‐related AE | 10 (17) | 7 (13) | 4 (7) |

| Serious AE | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Drug‐related serious AE‡ | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| AE leading to discontinuation§ | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 4 (7) |

| Adjudicated major adverse cardiac event | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Serious infection | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

†Defined as any AE with an onset date on or after the first dose of study drug in part A and before the first dose of part B or up to 105 days after last dose of study drug if the patient discontinued prematurely from part A. ‡Drug‐related serious AE included hypotension (risankizumab 75 mg, n = 1), acute myocardial infarction (risankizumab 150 mg, n = 1) and bacterial pneumonia (placebo, n = 1). §Adverse events leading to discontinuation included worsening psoriasis (risankizumab 75 mg, n = 2; placebo, n = 4) and erythrodermic psoriasis (risankizumab 150 mg, n = 1). AE, adverse event; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

Table 3.

Treatment‐emergent adverse events during part B of the study

| TEAE,† n (%) | Risankizumab 75 mg, n = 56 | Risankizumab 150 mg, n = 54 | Placebo to risankizumab 75 mg, n = 27 | Placebo to risankizumab 150 mg, n = 27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any AE | 35 (63) | 31 (57) | 18 (67) | 23 (85) |

| Drug‐related AE | 6 (11) | 7 (13) | 7 (26) | 6 (22) |

| Serious AE | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (7) | 0 |

| Drug‐related serious AE | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 |

| AE leading to discontinuation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4)‡ |

| Adjudicated major adverse cardiac event | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Serious infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malignant tumors | 0 | 0 | 1 (4)§ | 0 |

†Defined as any AE with an onset date on or after the first dose of study drug in part B and up to 105 days after the last dose of study drug. ‡Dermatitis. §Rectal cancer. AE, adverse event; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

Immunogenicity

Antidrug antibodies (ADAs) were detected in 39 of the 171 (23%) patients over the entire 52‐week study period. Fourteen patients had transient ADAs (i.e. present at only one assessment), whereas 25 had persistent ADAs. Neutralizing antibodies, assessed when ADAs were present, were found in 27 of the 171 (16%) patients. There was no notable difference in PASI‐90 responses based on the presence of ADAs and neutralizing antibodies (PASI‐90 responses at 16 weeks were achieved by 19 of 25 [76.0%] and 66 of 88 [75.0%] patients who were ADA positive and ADA negative, respectively).

Discussion

In this study, risankizumab demonstrated superior efficacy over placebo for both the 75‐ and 150‐mg dosing regimens in Japanese patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. Compared with the 75‐mg risankizumab dose, the risankizumab 150‐mg dose was associated with a faster onset of PASI‐90 and ‐100 responses and numerically higher PASI‐100 responses at week 16, while maintaining a similar safety profile. Overall, 76% and 75% of patients receiving risankizumab 75 and 150 mg, respectively, versus 2% of patients receiving placebo reached the primary end‐point of PASI‐90 at 16 weeks. PASI‐90 responses were similar in patients with or without psoriatic arthritis and were unaffected by immunogenicity. At 16 weeks, significantly more patients receiving either dose of risankizumab compared with placebo reached complete clearance (PASI‐100, higher response for 150 mg [33%] vs 75 mg [22%]) and clear or almost clear skin (sPGA 0 or 1). These response rates were consistent with findings from the global phase 3 ultIMMa‐1, ultIMMa‐2 and IMMhance risankizumab trials.15, 16 Among patients in these phase 3 trials, the PASI‐90 responses were achieved by 73–75% of patients receiving risankizumab 150 mg at week 16 (vs 2–5% of patients receiving placebo) and 73–82% at week 52. The patient‐reported outcome of achieving a DLQI of 0/1 was also generally consistent with findings from the ultIMMa‐1 and ultIMMa‐2 trials comparing risankizumab 150 mg versus ustekinumab and placebo.15 At 16 weeks, 66% (ultIMMa‐1) and 67% (ultIMMa‐2) of patients receiving risankizumab 150 mg in these trials achieved a DLQI 0/1 versus 62% (risankizumab 75 mg) and 58% (risankizumab 150 mg) in our trial. PASI absolute improvement was also similar between this study and the ultIMMa‐1 and ultIMMa‐2 studies, demonstrating rapid onset of action and sustained efficacy until week 52.

Our findings add to the growing evidence supporting the use of selective IL‐23 inhibition via binding to its p19 subunit to treat psoriasis. Results of phase 3 clinical trials of guselkumab, an IL‐23 inhibitor that targets the IL‐23 p19 subunit and is approved in Japan for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, have been reported previously.20, 21, 22 In the VOYAGE 1 and 2 trials, which included a placebo comparator arm, PASI‐90 response rates were similar to those reported in our study, with significantly higher proportions of patients receiving guselkumab compared with placebo reaching PASI‐90 at week 16 (70.0–73.3% vs 2.4–2.9%).20, 22 Moreover, our results were consistent with a recent study in Japanese patients treated with guselkumab 50 and 100 mg, which demonstrated superior efficacy versus placebo in PASI‐90 at 16 weeks (69.8–70.8% vs 0%, P < 0.001) and continued improvements in PASI‐90 through week 52 (75.4–90.5%).23

Possible advantages of selective inhibition of IL‐23 at the p19 subunit are also supported by findings from trials assessing risankizumab versus ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits IL‐12/23 by binding to the shared p40 subunit. Ustekinumab has demonstrated improved clinical outcomes in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis;24, 25 however, risankizumab has demonstrated superior efficacy to ustekinumab, with significantly more patients reaching PASI‐90 and ‐100 at 16 and 52 weeks.15 Increased expression of p19 and p40 subunit mRNA, but not IL‐12 p35 subunit mRNA, in lesional skin of patients with psoriatic disease has been demonstrated, further favoring a key role for IL‐23, but not IL‐12, in psoriasis pathogenesis.26

Overall, risankizumab was well tolerated among all patients receiving treatment and no dose‐dependent AEs were observed. Rates of AEs and serious AEs were similar for risankizumab and placebo and remained consistent through 52 weeks of treatment. In patients receiving risankizumab, there were no reported serious infections, and one report each of an acute myocardial infarction and rectal carcinoma. There were no reported serious hypersensitivity reactions, tuberculosis or deaths across all treatment groups during the study. Safety findings were consistent with data for risankizumab reported in four pivotal phase 3 studies15, 16, 17 and similar to other biologics assessed in Japanese patients.2, 5, 6, 27, 28

In conclusion, both the 75‐mg and 150‐mg doses of risankizumab were superior to placebo in meeting the primary end‐point of PASI‐90 at 16 weeks in the treatment of Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. PASI‐90 and ‐100 responses were reached more quickly in patients receiving risankizumab 150 mg than risankizumab 75 mg. Treatment responses were maintained or improved with continued treatment to 52 weeks. Response rates and safety were consistent with previously reported larger global phase 3 risankizumab trials, with no new or unexpected safety findings. Risankizumab showed promising clinical activity and improved quality of life, which supports its use in Japanese patients with psoriatic disease.

Conflict of Interest

The authors and AbbVie scientists designed the study and analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors contributed to the development of the content, all authors and AbbVie reviewed and approved the manuscript, and the authors maintained control over the final content. M. O. has received honoraria or fees for serving on advisory boards, as a speaker and as a consultant, and grants as an investigator from AbbVie, Celgene, Eisai, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Maruho, Mitsubishi‐Tanabe, Novartis and Torii. H. F. has received honoraria or fees for serving on advisory boards and as a speaker and grants as an investigator from AbbVie, Celgene, Eisai, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, LEO Pharma, Maruho, Mitsubishi‐Tanabe, Novartis, Taiho and Torii. M. W., K. S. and M. F. are full‐time employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. X. H., S. K. and J. V. are full‐time employees of AbbVie and may own stock/options. A. I. has received honoraria or fees for serving on advisory boards, as a speaker and as a consultant, and grants as an investigator from AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Maruho and Novartis.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Percentage of patients with PASI‐90 responses at week 16 by bodyweight and concomitant psoriatic arthritis. PASI‐90, 90% or more improvement from baseline in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001 vs placebo.

Figure S2. Mean percentage improvement from baseline in PASI over time. PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index. *** P < 0.001 vs placebo.

Figure S3. Percentage of patients achieving PASI of less than 3 over time. PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index. **P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001 vs placebo.

Acknowledgments

AbbVie and Boehringer Ingelheim funded the SustaIMM (NCT03000075) study; Boehringer Ingelheim contributed to its design and participated in data collection; AbbVie performed the data analysis and participated in interpretation of the data; and both participated in writing, review and approval of the manuscript. AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim and the authors thank all study investigators for their contributions and the patients who participated in this study. Medical writing support was provided by Mayur Kapadia, M.D., and Janet E. Matsuura, Ph.D., of Complete Publication Solutions, LLC (North Wales, PA, USA), a CHC Group Company, and was funded by AbbVie. Data sharing: AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual and trial‐level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g. protocols and Clinical Study Reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. This clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html

References

- 1. Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64: ii18–ii23; discussion ii24‐25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saeki H, Nakagawa H, Nakajo K et al Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab treatment for Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis and generalized pustular psoriasis: results from a 52‐week, open‐label, phase 3 study (UNCOVER‐J). J Dermatol 2017; 44: 355–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM et al Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 76: 377–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Asahina A, Torii H, Ohtsuki M et al Safety and efficacy of adalimumab treatment in Japanese patients with psoriasis: results of SALSA study. J Dermatol 2016; 43: 1257–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Torii H, Nakano M, Yano T, Kondo K, Nakagawa H, SPREAD Study Group . Efficacy and safety of dose escalation of infliximab therapy in Japanese patients with psoriasis: results of the SPREAD study. J Dermatol 2017; 44: 552–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nemoto O, Hirose K, Shibata S, Li K, Kubo H. Safety and efficacy of guselkumab in Japanese patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, placebo‐controlled, ascending‐dose study. Br J Dermatol 2018; 178: 689–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ohtsuki M, Terui T, Ozawa A et al Japanese guidance for use of biologics for psoriasis (the 2013 version). J Dermatol 2013; 40: 683–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency . List of Approved Products[Cited 2018 September 11]. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/english/review-services/reviews/approved-information/drugs/0002.html.

- 9. Girolomoni G, Strohal R, Puig L et al The role of IL‐23 and the IL‐23/TH 17 immune axis in the pathogenesis and treatment of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31: 1616–1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Campa M, Mansouri B, Warren R, Menter A. A review of biologic therapies targeting IL‐23 and IL‐17 for use in moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2016; 6: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen Z, Gong Y, Shi Y. Novel biologic agents targeting interleukin‐23 and interleukin‐17 for moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis. Clin Drug Investig 2017; 37: 891–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chan TC, Hawkes JE, Krueger JG. Interleukin 23 in the skin: role in psoriasis pathogenesis and selective interleukin 23 blockade as treatment. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2018; 9: 111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Krueger JG, Ferris LK, Menter A et al Anti‐IL‐23A mAb BI 655066 for treatment of moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis: safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and biomarker results of a single‐rising‐dose, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 136: 116–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Papp KA, Blauvelt A, Bukhalo M et al Risankizumab versus ustekinumab for moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 1551–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gordon KB, Strober B, Lebwohl M et al Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis (UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2): results from two double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled and ustekinumab‐controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet 2018; 392: 650–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Gooderham M et al Risankizumab efficacy/safety in moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: 16‐week results from IMMhance. Acta Derm Venereol 2018; 98: 30. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reich K, Gooderham M, Thaci D et al Efficacy and safety of risankizumab compared with adalimumab in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: results from the phase 3 IMMvent trial. Presented at: 27th European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Congress, September 12‐16, 2018; Paris, France.

- 18. Weisman S, Pollack CR, Gottschalk RW. Psoriasis disease severity measures: comparing efficacy of treatments for severe psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat 2003; 14: 158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994; 19: 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Griffiths CE et al Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti‐interleukin‐23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: results from the phase III, double‐blinded, placebo‐ and active comparator‐controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 76: 405–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Langley RG, Tsai TF, Flavin S et al Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis who have an inadequate response to ustekinumab: results of the randomized, double‐blind, phase III NAVIGATE trial. Br J Dermatol 2018; 178: 114–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reich K, Armstrong AW, Foley P et al Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti‐interleukin‐23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: results from the phase III, double‐blind, placebo‐ and active comparator‐controlled VOYAGE 2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 76: 418–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ohtsuki M, Kubo H, Morishima H, Goto R, Zheng R, Nakagawa H. Guselkumab, an anti‐interleukin‐23 monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque‐type psoriasis in Japanese patients: efficacy and safety results from a phase 3, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. J Dermatol 2018; 45: 1053–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tsai TF, Ho JC, Song M et al Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab for the treatment of moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis: a phase III, randomized, placebo‐controlled trial in Taiwanese and Korean patients (PEARL). J Dermatol Sci 2011; 63: 154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Papp KA, Langley RG, Lebwohl M et al Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin‐12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 52‐week results from a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial (PHOENIX 2). Lancet 2008; 371: 1675–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee E, Trepicchio WL, Oestreicher JL et al Increased expression of interleukin 23 p19 and p40 in lesional skin of patients with psoriasis vulgaris. J Exp Med 2004; 199: 125–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sano S, Kubo H, Morishima H, Goto R, Zheng R, Nakagawa H. Guselkumab, a human interleukin‐23 monoclonal antibody in Japanese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis and erythrodermic psoriasis: efficacy and safety analyses of a 52‐week, phase 3, multicenter, open‐label study. J Dermatol 2018; 45: 529–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Imafuku S, Honma M, Okubo Y et al Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: a 52‐week analysis from phase III open‐label multicenter Japanese study. J Dermatol 2016; 43: 1011–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Percentage of patients with PASI‐90 responses at week 16 by bodyweight and concomitant psoriatic arthritis. PASI‐90, 90% or more improvement from baseline in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001 vs placebo.

Figure S2. Mean percentage improvement from baseline in PASI over time. PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index. *** P < 0.001 vs placebo.

Figure S3. Percentage of patients achieving PASI of less than 3 over time. PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index. **P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001 vs placebo.