Abstract

Aim

To explore the added value of diabetes‐related genetic risk scores (GRSs) to readily available clinical variables in the prediction of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels after initiation of glucose‐regulating drugs.

Materials and methods

We conducted a cohort study in people with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) from the Groningen Initiative to Analyse Type 2 Diabetes Treatment (GIANTT) database who initiated metformin (MET) or sulphonylurea derivatives (SUs) and for whom blood samples were genotyped. The primary outcome was HbA1c level at 6 months, adjusted for baseline HbA1c. GRSs were based on single nucleotide polymorphisms linked to insulin sensitivity, β‐cell activity, and T2DM risk in general. Associations were analysed using multiple linear regression to assess whether adding the GRSs increased the explained variance in a prediction model that included age, gender, diabetes duration and cardio‐metabolic biomarkers.

Results

We included 282 patients initiating MET and 89 patients initiating SUs. In the MET prediction model, diabetes duration of >3 months when starting MET was associated with 2.7‐mmol/mol higher HbA1c level. For SUs, no significant clinical predictors were identified. Addition of the GRS linked to insulin sensitivity (for MET), β‐cell activity (for SUs) and T2DM risk (for both) to the models did not improve the explained variance significantly (22% without vs. 22% with GRS) for the MET and (14% without vs. 14% with GRS) for the SUs model, respectively.

Conclusion

This study did not indicate a significant effect of GRS related to T2DM in general or to the drugs' mechanism of action for prediction of inter‐individual HbA1c variability in the short term after initiation of MET or SU therapy.

Keywords: antidiabetic agents, diabetes risk genes, glucose‐lowering therapy, HbA1c, metformin, sulphonylurea derivatives, type 2 diabetes mellitus

1. INTRODUCTION

Metformin (MET) and sulphonylurea derivatives (SUs) are effective drugs for the treatment of hyperglycaemia in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Previous studies have shown that the inter‐individual variability in treatment response to these drugs is high.1, 2, 3 As the general aim of T2DM drug therapy is to prevent diabetes‐related complications, it is important to obtain more insight into potential predictors of treatment response in the disease's initial stages in order to tailor therapy optimally.

In a previous systematic review, we assessed whether clinical variables could predict the initial glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) response to these drugs. The review showed that diabetes duration was the only consistent predictor of response across studies, with early treatment initiation in people with short diabetes duration being associated with better treatment response.4 In addition to clinical variables, the influence of a person's genetic makeup on MET and SU treatment response has been explored and systematically reviewed with an emphasis on OCT genes, genes for encoding additional proteins associated with AMP‐activated protein kinase‐dependent inhibition of gluconeogenesis, SLC47A1 and A2, PMAT, ATM, IRS1, NOS1AP, KCNJ11, ABCC8, CYP2C9 and TCF7L2.5, 6, 7, 8 Unfortunately, to date, the clinical applicability of genotyping prior to drug treatment has been limited, because the effect of the genetic variants on treatment response has been determined for specific variants and not in an integrated way.9, 10

A previous clinical study assessed the impact of genetic constitution on diabetes progression. This resulted in the indentification of 65 risk genes for T2DM, with clusters associated with β‐cell activity and insulin sensitivity.11 Because these risk genes drive disease progression in the early stage of the disease, we hypothesized that, in addition to readily available clinical predictors, these genes might also play a role in predicting the initial treatment response. In contrast to investigating the impact of genetic makeup from the perspective of the drugs used, we approached the variability in response to MET and SUs from the perspective of the genetic makeup involved in progression of T2DM.

The aim of the present study, therefore, was to determine the added value of (a) clusters of T2DM‐related genetic risk scores (GRSs) related to β‐cell activity (specifically in the case of SUs) and insulin sensitivity (specifically in the case of MET), and (b) general GRSs for T2DM in predicting HbA1c levels after treatment initiation of MET and SUs.

2. PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design and population

We performed an observational inception cohort study predicting HbA1c levels after treatment initiation among people with T2DM included in the Groningen Initiative to Analyse Type 2 Diabetes Treatment (GIANTT) project. The GIANTT database consists of prescription data, comorbidity and clinical outcome data, routine laboratory test results, and physical examinations extracted anonymously from electronic medical records.12 The cohort is predominantly of European ancestry. The database includes people with a diagnosis of T2DM as confirmed by their general practitioner. Based on the research code of conduct in the Netherlands, ethics committee approval is not required for research using such anonymous medical record data.

A subset of people with T2DM in the GIANTT database participated in PROVALID, an international cohort study on the incidence and prevalence of kidney disease in primary diabetes care.13 The PROVALID study was approved by the local Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Centre of Groningen, and informed consent was obtained from each participant for the use of genetic samples before any study‐specific procedures commenced (study approval reference number: NL35350.042.11, METC number 2011.297).

In the present study, we determined two sub‐cohorts: a MET and an SU cohort. For these cohorts, the index date was defined as the date of the first MET or SU prescription, respectively.

In the MET cohort, the inclusion criteria were: (a) receiving MET as first‐line glucose‐lowering drug; (b) registration in the GIANTT database and receiving no glucose‐lowering medication for at least 1 year before the index date; and (c) at least two prescriptions of MET and exposure to MET at least until 30 days after the start of the second prescription.

In the SU cohort, the inclusion criteria were receiving an SU as first glucose‐lowering drug (SU‐only) or receiving add‐on SU while on a stable MET dose in the previous 6 months (SU‐combi). Both SU‐only participants and SU‐combi participants had to be prescribed at least two prescriptions of an SU and exposed to an SU at least until 30 days after the second prescription. In addition, people receiving SU‐only had to be registered in the GIANTT database and have received no glucose‐lowering drug for at least a year before the index date. This implies that people who started on MET and reached a stable MET dose after which an SU was added could be included in the MET cohort for the first period and in the SU cohort for the second period.

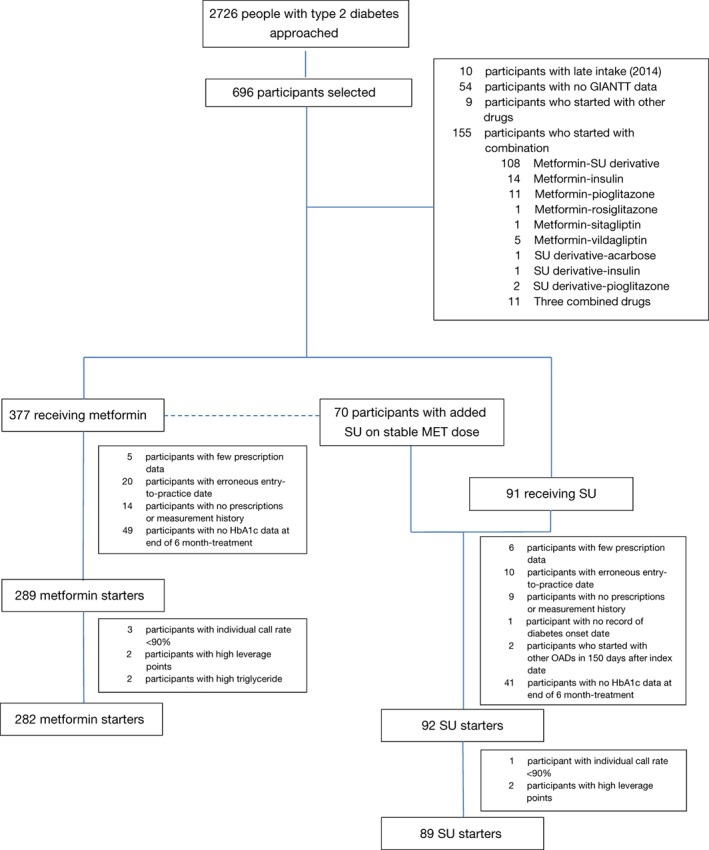

In both the MET and SU cohorts, we excluded people with: (a) erroneous dates of entering the practice; (b) no history of laboratory and practice measurements or prescriptions; (c) no recorded HbA1c at 6 months; (d) high serum triglyceride level (>9.0 mmol/mol); (e) an individual call rate of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) < 90%; and (e) a high leverage point in the multivariate models (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient selection. GIANTT, Groningen initiative to analyse type 2 diabetes treatment; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; MET, metformin; OAD, oral antidiabetic drug; SU, sulphonylurea derivative

2.2. Study outcome and covariates

For each of the cohorts, the outcome was HbA1c level at 6 months after MET or SU treatment. The HbA1c outcome selected was the closest HbA1c measurement to the 6 months after the index date. We adjusted this outcome by including the HbA1c level at baseline, which was the latest HbA1c measurement 1 year before or in the first 2 weeks after index date, as a covariate. This adjustment accounted for the effect on HbA1c of concurrent treatment at the time of initiation.

To obtain genetic information, DNA was extracted from blood samples and genotypes were obtained using the iPlex Gold platform (Agena Bioscience GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) at the Department of Genetics, University Medical Centre Groningen, the Netherlands. We then constructed GRSs by summing the number of risk alleles each participant had for every SNP and calculated its effect “per GRS unit” using the established diabetes risk variants representing an individual's genetic susceptibility risk, as described by Zhou et al.14 We did not apply a weighted GRS, because of the large heterogeneity among people with T2DM.

As the primary genetic determinant for the MET and SU cohorts, we constructed GRSs consisting of SNPs known to be associated with insulin sensitivity (IS‐GRS) and β‐cell activity (β‐GRS), respectively.14 Additionally, we built another GRS comprising SNPs associated with T2DM risk (total‐GRS), in which the SNPs in the IS‐GRS and the β‐GRS were also included.11 In the genotyping, two SNPs were not present (rs780094 and rs516946) and no proxy SNP data were available. We then applied the call rate threshold of 94% and excluded four SNPs.

In the present study, five SNPs from the IS‐GRS and 14 from the β‐GRS were present. Both the MET and SU cohorts had a total‐GRS of 59 SNPs, albeit with different compositions (Table S1). All SNPs included had a minor allele frequency of >0.01 and were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P > 10−5).

As clinical covariates, we included baseline age, gender, diabetes duration, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure and lipid levels (HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol and triglycerides). With the exception of BMI, baseline data collection was based on the latest measurement 24 months prior to the index date. To limit missing data, BMI was measured either as the latest measurement ever or manually calculated from the latest length measurement and the latest before or the first measurement of weight 90 days after index date. Age and diabetes duration were calculated from the index date.

2.3. Statistical analyses

We applied the following statistical analyses to both the MET and SU cohorts. First, we used a multiple imputation by chained equation procedure to overcome the missing data. We generated 30 imputed datasets, the detailed methods for which have been described previously.15

First, we assessed whether the outcome HbA1c, adjusted for baseline HbA1c as a covariate, was univariately associated with either the clinical covariates or GRSs. We then included age, gender and variables with P values <.20 from the univariate analyses into a multivariate linear model. Model specification tests (linktest and ovtest functions in stata 13; Statacorp, College Station, Texas) were used to assess whether the variables in the model were correctly defined. In the MET cohort model, dichotomization of diabetes duration with a 3‐month cut‐off point solved the non‐linear correlation in the model and resulted in a balanced number of participants in each category. We also included a binary HbA1c control status (control being <53 mmol/mol) at baseline in this model, because the univariate analysis with baseline HbA1c showed a discontinued slope at 53 mmol/mol. In the SU cohort model, we included patient status at index date (SU‐only or SU‐combi) to correctly specify the model based on linktest and ovtest.

The coefficient of determinant (R2) was used to explain the percentage of explained variance and overall performance of the model. The additional value of genetic covariates was determined by comparing the explained variance (R2) of models with and without the inclusion of GRSs.

We conducted complete case analyses for comparison. Furthermore, we determined whether effect modification by the last prescribed dose was present. The last MET dose was defined as the daily quantity of MET last prescribed in the 6 months after treatment. For SUs, defined daily dose (DDD) was used to standardize the dose of different drugs in the same drug class. The last dose for an SU was thus calculated as daily quantity of SU last prescribed in the 6 months after treatment, divided by DDD.16

3. RESULTS

Out of 2726 people with T2DM who were approached, 903 participated in PROVALID and 696 consented to participate in the genetic study. Of these 696 participants, 282 initiated MET and 89 initiated SU and met the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study (Figure 1). In both the MET and SU cohorts, the average age of the participants was almost 60 years and ~60% were men. Except for a longer diabetes duration in the SU cohort, the cohorts had similar clinical characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics, presented as mean ± SD or count (percentage)

| Characteristics | MET | SU |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 282 | 89 |

| Age at onset, y | 59 ± 9 | 55 ± 9 |

| Age at initiation, y | 59 ± 9 | 58 ± 9 |

| Male gender | 167 (59) | 56 (62) |

| Diabetes duration | 110 ± 101 | |

| 0–3 mo | 142 (50) | ‐ |

| >3 mo | 140 (50) | ‐ |

| Baseline HbA1c, mmol/mol | 58.9 ± 14.9 | 58.7 ± 13.3 |

| HbA1c at 6 mo, mmol/mol | 49.2 ± 6.2 | 49.6 ± 6.7 |

| HbA1c control status, n (%) | ||

| <53 mmol/mol | 85 (37) | ‐ |

| ≥53 mmol/mol | 142 (63) | ‐ |

| SU status, n (%) | ||

| SU‐only | ‐ | 37 (42) |

| SU‐combi | ‐ | 52 (58) |

| Baseline BMI, kg/m2 | 30.6 ± 5.1 | 29.5 ± 5.4 |

| Baseline blood pressure, mmHg | ||

| Systolic | 140.6 ± 18.5 | 140.5 ± 18.9 |

| Diastolic | 83.0 ± 11.8 | 83.4 ± 11.4 |

| Baseline lipid levels, mmol/L | ||

| HDL cholesterol | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.4 |

| Total cholesterol | 5.1 ± 1.1 | 4.7 ± 1.2 |

| Triglycerides | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 2.2 ± 1.3 |

| GRSs | ||

| β‐cell secretion‐related (β‐GRS) | ‐ | 15.2 ± 2.4 |

| Insulin sensitivity‐related (IS‐GRS) | 6.0 ± 1.4 | ‐ |

| Total | 71.1 ± 5.6 | 70.0 ± 5.1 |

| MET dose at 6 mo, n (%) | ||

| ≤500 mg | 117 (41) | ‐ |

| 750‐1000 mg | 95 (34) | ‐ |

| >1000 mg | 70 (25) | ‐ |

| SU group, n (%) | ||

| Glibenclamide | ‐ | 1 (1) |

| Tolbutamide | ‐ | 27 (30) |

| Gliclazide | ‐ | 53 (60) |

| Glimepiride | ‐ | 8 (9) |

| SU dose at 6 mo (DDDs), n (%) | ||

| ≤0.5 | ‐ | 50 (56) |

| >0.5 | ‐ | 39 (44) |

Abbreviations: DDD, defined daily dose; MET, metformin; SU, sulphonylurea derivatives.

Based on the univariate analyses (Table S2), diabetes duration and HbA1c control status at baseline were included in the multivariate model for the MET cohort. In this model, diabetes duration of >3 months when initiating MET was associated with a 2.7‐mmol/mol higher HbA1c level after 6 months (Table 2). Not having HbA1c control at baseline was associated with an increase of 3.1 mmol/mol in HbA1c level after 6 months, despite adjustment of the model for baseline level of HbA1c. This multivariate model had an explained variance of 22%. The addition of GRSs, either the IS‐GRS or total GRS, showed no improvements in the explained variance or changes in the β coefficients of the model. The complete case analysis showed similar results (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate linear regression models for glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) at 6 mo of metformin treatment, before and after addition of genetic risk scores (adjusted for HbA1c at baseline)

| Variable | Imputed (N = 282) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without GRS | IS‐GRS | Total GRS | ||||

| β (95% CI) | P | β (95% CI) | P | β (95% CI) | P | |

| Female gender | 0.47 (−0.90; 1.85) | .500 | 0.48 (−0.90; 1.85) | .497 | 0.46 (−0.92; 1.84) | .512 |

| Age (y) | −0.04 (−0.12; 0.04) | .288 | −0.04 (−0.12; 0.04) | .306 | −0.04 (−0.12; 0.04) | .333 |

| Diabetes duration | ||||||

| 0‐3 mo | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| >3 mo | 2.69 (1.31; 4.07) | <.001 | 2.69 (1.30; 4.06) | <.001 | 2.70 (1.32; 4.08) | <.001 |

| HbA1c control status | ||||||

| <53 mmol/mol | 0.00 | |||||

| ≥53 mmol/mol | 3.08 (1.18; 4.98) | .002 | 3.09 (1.18; 4.99) | .002 | 3.09 (1.19; 4.99) | .002 |

| IS‐GRS/total GRS | ‐ | ‐ | 0.05 (−0.45; 0.55) | .849 | 0.04 (−0.09; 0.15) | .586 |

| R2 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.22 | |||

| Variable | Complete case (N = 227) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without GRS | IS‐GRS | Total GRS | ||||

| β (95% CI) | P | β (95% CI) | P | β (95% CI) | P | |

| Female gender | 0.49 (−0.87; 1.85) | .475 | 0.49 (−0.87; 1.86) | .476 | 0.49 (−0.87; 1.85) | .481 |

| Age (y) | −0.03 (−0.10; 0.05) | .496 | −0.03 (−0.11; 0.05) | .490 | −0.02 (−0.10; 0.05) | .556 |

| Diabetes duration | ||||||

| 0‐3 mo | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| >3 mo | 2.59 (1.21; 3.97) | <.001 | 2.59 (1.20; 3.97) | <.001 | 2.60 (1.21; 3.98) | <.001 |

| HbA1c control status | ||||||

| <53 mmol/mol | 0.00 | |||||

| ≥53 mmol/mol | 3.57 (1.85; 5.28) | <.001 | 3.56 (1.84; 5.28) | <.001 | 3.58 (1.86; 5.30) | <.001 |

| IS‐GRS/total GRS | ‐ | ‐ | −0.03 (−0.54; 0.48) | .903 | 0.04 (−0.08; 0.16) | .542 |

| R2 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.24 | |||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GRS, genetic risk score; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; IS‐GRS, insulin sensitivity GRS.

When stratified by last dose of MET at the end of 6‐month treatment (Table S3), the results showed slightly higher explained variance of the models (R2 = 27%‐28%). The effect of diabetes duration was more prominent when the participants were prescribed <1000 mg MET daily, while female gender appeared to increase the HbA1c level in participants prescribed >1000 mg MET daily, with an increase of 4.6 mmol/mol in HbA1c level after 6 months (Table S3). Again, no significant effect of adding the IS‐GRS was seen in the stratified analysis.

For the SU cohort, no associations were seen in univariate analyses between the outcome HbA1c and the study covariates (Table S2); thus, the multivariate model consisted of age, gender and adjustment of SU patient status (SU‐only or SU‐combi), showing insignificant associations. The model had an explained variance of 14%. Similarly to the MET cohort, the inclusion of either the β‐GRS or total GRS in the models had no effect on the explained variances or β coefficients (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate linear regression models for glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) at 6 mo of sulphonylurea treatment, before and after addition of genetic risk scores (adjusted for HbA1c at baseline)

| Variable | Imputed (N = 89) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without GRS | β‐GRS | Total GRS | ||||

| β (95% CI) | P | β (95% CI) | P | β (95% CI) | P | |

| Female gender | 2.45 (−0.40; 5.29) | .091 | 2.35 (−0.58; 5.29) | .115 | 2.47 (−0.38; 5.33) | .088 |

| Age (y) | −0.01 (−0.17; 0.15) | .921 | −0.01 (−0.17; 0.16) | .925 | −0.01 (−0.17; 0.15) | .894 |

| SU‐combi | 2.17 (−0.78; 5.11) | .147 | 2.19 (−0.78; 5.17) | .146 | 2.24 (−0.72; 5.21) | .136 |

| β‐GRS/GRS | ‐ | ‐ | −0.09 (−0.70; 0.52) | .759 | −0.10 (−0.37; 0.17) | .465 |

| R2 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 | |||

| Variable | Complete case (N = 82) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without GRS | β‐GRS | Total GRS | ||||

| β (95% CI) | P | β (95% CI) | P | β (95% CI) | P | |

| Female gender | 2.42 (−0.07; 4.90) | .056 | 1.85 (−0.87; 4.58) | .180 | 2.40 (−0.21; 5.01) | .071 |

| Age (y) | 0.001 (−0.14; 0.14) | .988 | −0.01 (−0.15; 0.14) | .903 | −0.02 (−0.16; 0.13) | .805 |

| SU‐combi | 2.85 (0.20; 5.51) | .036 | 3.05 (0.39; 5.71) | .025 | 3.00 (−0.33; 5.66) | .028 |

| β‐GRS/GRS | ‐ | ‐ | −0.37 (−0.92; 0.18) | .181 | −0.13 (−0.37; 0.10) | .266 |

| R2 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.15 | |||

Abbreviations: β‐GRS, β‐cell activity genetic risk score; CI, confidence interval; GRS, genetic risk score; SU‐combi, sulphonylurea derivative and metformin treatment combined.

4. DISCUSSION

In the present observational study, we explored the added value of diabetes‐related GRSs in the prediction of HbA1c response after MET and SU initiation. Diabetes duration was shown to be significantly associated with HbA1c response in a multivariate model of clinical predictors, which is consistent with previous findings.4, 14 No significant associations between T2DM‐related risk scores and HbA1c response were observed in univariate and multivariate analyses, either with mechanism‐specific risk genes (IS‐GRS and β‐GRS) or with risk genes in general (total‐GRS). Moreover, the inclusion of GRSs in the models did not improve the explained variance.

The genetics of MET or SU treatment response have been studied previously, and several genetic variants have been identified as being associated with response to treatment, for instance, in the case of MET for OCT genes, SLC47A1 and A2 (MATE1 and MATE2), PMAT and ATM, and in the case of SUs for ABCC8, CYP2C9, KCNJ11, TCF7L2, genes encoding additional proteins associated with AMP‐activated protein kinase‐dependent inhibition of gluconeogenesis, IRS1, NOS1AP.5, 6, 7, 8 However, translation into clinical practice of pharmacogenetics is still lacking. We therefore approached the inter‐individual differences in response to MET and SUs not from the perspective of the genetics in the context of the drugs, but from the perspective of the genetic variation in T2DM. We investigated whether part of the inter‐individual variability in treatment response to MET and SUs seen in practice could be explained by possible inter‐individual differences, as reflected by the diabetes risk genes.11 Previously, Hivert et al17 could not detect an interaction effect of MET on the association of a GRS with T2DM prediction and regression to normal glucose regulation in patients with impaired glucose tolerance. We investigated a possible effect on HbA1c in people already diagnosed with T2DM initiating MET or SU treatment and did not observe any significant associations of the diabetes‐related GRSs in the early stages of the disease. Furthermore, apart from the total risk genes, we looked at gene clusters specifically associated with insulin sensitivity and β‐cell activity for MET and SUs, respectively, as related to their mechanism of action, and did not find any significant effects.

In our observational cohort study we developed a prediction model for HbA1c levels at 6‐month follow‐up, adjusted for baseline HbA1c. In the MET prediction model, a longer diabetes duration and absence of HbA1c control at the time of treatment initiation resulted in higher HbA1c levels after 6 months. Neither the total GRS nor the IS‐GRS improved the explained variance of the model. In the SU cohort no significant clinical predictors were identified and neither the total GRS nor the β‐GRS improved the explained variance of the model; therefore, in contrast to the findings of at least some associations between the genetic makeup and drug response from the perspective of the drug itself, the T2DM‐related GRSs do not seem to be associated with the variability in HbA1c response in people with T2DM. Risk prediction for T2DM seems not to coincide with treatment response prediction for MET and SUs. A more profound analysis of both the pathways of the drug action and the activity of the molecular pathways within the individual patient may lead to better response prediction models.

To our knowledge, this is the first study determining the association between diabetes‐related GRSs and HbA1c response in people with T2DM initiating oral glucose‐lowering treatment. This observational study involved a primary care T2DM population, whose medication data and HbA1c test results were automatically extracted from medical records through validated procedures. We looked at HbA1c response after 6 months, which was sufficient to differentiate glucose‐regulating responses.15 For this study, 59 SNPs for the total GRS, of which five were included in the IS‐GRS and 14 included in the β‐GRS were studied. We used multiple imputation to overcome missing data for the covariates. We consider this the optimal approach, but also conducted complete case analyses, the results of which did not differ significantly. We were able to include 282 participants in the MET cohort but only 89 in the SU cohort; therefore, the power to detect small effects, in particular those related to the SUs, was low. This may have limited our ability to detect a real effect, particularly if the effect was small, which is often the case for a disease with a complex underlying pathophysiology such as T2DM. We note, however, that we did not observe a large variance around the GRS which may be the result of using a GRS instead of individual SNPs.

In conclusion, T2DM‐related GRSs in general or specific to the mechanism of action of MET and SUs appear not to be predictive for inter‐individual HbA1c variability after initiation of MET and SUs. This study can be seen as initial indication that the genes implicated in the risk to T2DM are different from genes associated with response to T2DM treatment with MET and SUs. Larger studies including more genes are needed to explain treatment response variability in people with T2DM.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in the design, analyses and critical reading of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1. Type II diabetes associated SNPs and loci for GRS – categorized for insulin sensitivity and β‐cells

Table S2. Univariate associations with HbA1c at 6 months of treatment

Table S3. Multivariate linear regression models for HbA1c at 6 months of metformin treatment, stratified by last metformin dose (adjusted for baseline HbA1c)

Martono DP, Heerspink HJL, Hak E, Denig P, Wilffert B. No significant association of type 2 diabetes‐related genetic risk scores with glycated haemoglobin levels after initiating metformin or sulphonylurea derivatives. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:2267–2273. 10.1111/dom.13803

Funding information Indonesian Directorate General of Higher Education

Peer Review The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/dom.13803.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cook MN, Girman CJ, Stein PP, Alexander CM. Initial monotherapy with either metformin or sulphonylureas often fails to achieve or maintain current glycaemic goals in patients with type 2 diabetes in UK primary care. Diabet Med. 2007;24(4):350‐358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Donnelly LA, Doney ASF, Hattersley AT, Morris AD, Pearson ER. The effect of obesity on glycaemic response to metformin or sulphonylureas in type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006;23(2):128‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nichols GA, Conner C, Brown JB. Initial nonadherence, primary failure and therapeutic success of metformin monotherapy in clinical practice. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(9):2127‐2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martono DP, Lub R, Lambers Heerspink HJ, Hak E, Wilffert B, Denig P. Predictors of response in initial users of metformin and sulphonylurea derivatives: a systematic review. Diabet Med. 2015;32(7):853‐864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Engelbrechtsen L, Andersson E, Roepstorff S, Hansen T, Vestergaard H. Pharmacogenetics and individual responses to treatment of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2015;25(10):475‐484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maruthur NM, Gribble MO, Bennett WL, et al. The pharmacogenetics of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(3):876‐886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhou K, Pedersen HK, Dawed AY, Pearson ER. Pharmacogenomics in diabetes mellitus: insights into drug action and drug discovery. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(6):335‐344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Leeuwen N, Swen JJ, Guchelaar H‐J, ’t Hart LM. The role of pharmacogenetics in drug disposition and response of oral glucose‐lowering drugs. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2013;52(10):833‐854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kovacs P, Pearson E. Pharmacogenetics of sulfonylureas In: Florez JC, ed. Pharmacogenetics of Sulfonylureas. The Genetics of Type 2 Diabetes and Related Traits: Biology, Physiology and Translation. New York, NY: Springer; 2016:483‐497. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhou K, Donnelly L, Yang J, et al. Heritability of variation in glycaemic response to metformin: a genome‐wide complex trait analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(6):481‐487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morris A, Voight B, Teslovich T. Large‐scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2012;44(9):981‐990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Voorham J, Denig P. Computerized extraction of information on the quality of diabetes care from free text in electronic patient records of general practitioners. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14(3):349‐354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eder S, Leierer J, Kerschbaum J, et al. A prospective cohort study in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus for validation of biomarkers (PROVALID) ‐ study design and baseline characteristics. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2018;43(1):181‐119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhou K, Donnelly LA, Morris AD, et al. Clinical and genetic determinants of progression of type 2 diabetes: a DIRECT study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(3):718‐724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martono DP, Hak E, Lambers Heerspink H, Wilffert B, Denig P. Predictors of HbA1c levels in patients initiating metformin. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(12):2021‐2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. WHOCC . Definition and general considerations. https://www.whocc.no/ddd/definition_and_general_considera/. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- 17. Hivert MF, Jablonski KA, Perreault L, et al. Updated genetic score based on 34 confirmed type 2 diabetes loci is associated with diabetes incidence and regression to normoglycemia in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes. 2011;60(4):1340‐1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Type II diabetes associated SNPs and loci for GRS – categorized for insulin sensitivity and β‐cells

Table S2. Univariate associations with HbA1c at 6 months of treatment

Table S3. Multivariate linear regression models for HbA1c at 6 months of metformin treatment, stratified by last metformin dose (adjusted for baseline HbA1c)