Abstract

The Drosophila slowpoke gene encodes a BK-type calcium-activated potassium channel. Null mutations inslowpoke perturb the signaling properties of neurons and muscles and cause behavioral defects. The animals fly very poorly compared with wild-type strains and, after exposure to a bright but cool light or a heat pulse, exhibit a “sticky-feet” phenotype. Expression of slowpoke arises from five transcriptional promoters that express the gene in neural, muscle, and epithelial tissues. A chromosomal deletion (ash218) has been identified that removes the neuronal promoters but not the muscle–tracheal cell promoter. This deletion complements the flight defect ofslowpoke null mutants but not the sticky-feet phenotype. Electrophysiological assays confirm that theash218 chromosome restores normal electrical properties to the flight muscle. This suggests that the flight defect arises from a lack of slowpoke expression in muscle, whereas the sticky-feet phenotype arises from a lack of expression in nervous tissue.

Keywords: Drosophila, calcium-activated potassium channel, potassium channel, behavior, flight, tissue-specific transcription, regulation of transcription

Ion channel proteins generate the electrical impulses used by neurons and muscles to convey information and trigger movement. The range of electrical properties that a cell can manifest arises from the combined activity of the suite of channels expressed. Ion channels also participate in processes distinct from the transmission of electrical signals. In many epithelial cells, the same family of channels participate in transport of ions, water, and nutrients between the lumen of organs and their interior (Pacha et al., 1991; Stoner and Morley, 1995). The combination of channels expressed is expected to be substantially different in these functionally disparate cells.

The choice of which channels a cell is to express does not appear to be a simple decision. The superfamily of ion channels are represented by a large number of distinct genes, some of which can encode multiple products via alternative promoter use and alternative splicing (Brenner and Atkinson, 1996; Wei et al., 1996). In general, the number of biophysically distinct channels expressed by a cell is small compared with its potential.

The Drosophila slowpoke gene encodes a Ca-activated K channel expressed in neurons, muscles, midgut, and trachea (Becker et al., 1995). Elimination of the channel by mutation dramatically alters the electrical properties of both neurons and muscles (Elkins and Ganetzky, 1988; Saito and Wu, 1991; Warbington et al., 1996). In tracheal and midgut cells, the function of the channel has not been directly demonstrated, but it is believed to participate in the process of electrolyte transport and acid secretion, respectively (Becker et al., 1995; Brenner and Atkinson, 1997). It is unlikely that a single channel polypeptide satisfies the functional needs of such disparate tissue types. The slowpoke gene, however, is well suited for this role. Expression of slowpoke arises from an array of tissue-specific transcriptional promoters, some of which give rise to mRNAs that encode polypeptides differing in their N terminus. To date, five tissue-specific promoters have been mapped (Bohm et al., 2000). In addition, slowpoke transcripts are alternatively spliced at five sites that affect the coding region of the gene (Atkinson et al., 1991; Adelman et al., 1992). It is assumed that multiple promoters and alternative splicing enable tissues to express channels tailored to the needs of the cell.

In addition to their electrophysiological phenotypes,slowpoke mutants display behavioral abnormalities. The animals are semiflightless and, in response to a brief heat pulse, remain stationary for many minutes (Elkins et al., 1986). This unusual temperature-dependent phenotype is difficult to understand in terms of thermolabile proteins. Here, we demonstrate that the animals are not paralyzed but inappropriately adhere to the surface and that this behavior is not wrought by temperature per se but appears to be a consequence of overstimulation. Using a chromosomal deletion that removes the neuronal but not the muscle promoter, we demonstrate the origins of the “sticky-feet” and the flight phenotypes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Stocks. Drosophila stocks were maintained using standard Drosophila husbandry techniques. Four stocks were used: w1118; st hhbar3 slo1,slo4, y w; red e ash218/y+ TM3 Sb e Ser, and red, e,ash218/TM6 Tb. Theash218 allele stock was kindly provided by Allen Shearn (Department of Biology, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD).

Reverse transcription-PCR. For reverse-transcription (RT)-PCR, RNA was purified fromw1118 flies, fromslo4 flies, and from red e ash218/slo4transheterozygotes. Approximately 0.5 gm of adult animals were added to 2.5 ml (5 vol) of 3 m LiCl, 6m urea, and 0.2% SDS and ground in a glass homogenizer. To precipitate the RNA, the sample was incubated overnight on ice and centrifuged at 5000 rpm [Sorvall (Newtown, CT) RC5C with a SA-600 rotor] for 20 min at 4°C in a 15 ml Corex centrifuge tube. The liquid between the bottom pellet and the floating pellet was removed with a pipette and discarded. The pellet was dissolved in 2–4 vol of 10 mm Tris-base, 1 mm Na2EDTA, and 1% SDS on ice for 15 min. The solution was extracted twice with phenol:CCl3 (24:1), pH 8.0 with 0.1% hydroxyquinoline, and once with CCl3. The RNA was precipitated by adjusting the aqueous layer to 0.3m sodium acetate (stock is pH 5.2), followed by the addition of 3 vol of 100% ethanol and incubation at −70°C. The RNA was stored in ethanol until needed. To recover the RNA, the solution was centrifuged at 8500 rpm/30 min/4°C. The pellet was air-dried and resuspended in 300–600 μl of water. All solutions were made using DEPC-treated water.

One microgram of RNA was reverse-transcribed in a 25 μl volume with Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) and 0.5 pm of the primer slo26 (5′ TGCGATCCAGTATGCAGTCT 3′) for 45 min at 40°C. The solution was adjusted to 100 μl with water and heated at 65°C for 5 min. Five microliters of the RT product was used to seed the PCR reaction.

A hot-start PCR amplification was performed in a PCR machine (MJ Research Inc., Watertown, MA) with the enzyme mix provided in a 100 μl volume using the enzyme mix provided in the Expand High Fidelity PCR System (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) and 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.125 mm dNTPs, and 2 μm of each PCR primer. Annealing temperatures were determined using the OLIGO program (National Biosciences, Plymouth, MA).

To detect transcripts produced by slowpoke promoter C0, PCR was performed using the GAMMA5 primer (5′ ATTGTATACGCTGCTGACGAGA3′, anneals to exon C0) and slo45 primer (5′ CCGCCATTTTGATTCTGTGTG3′, anneals at approximately nucleotide 2520). The slo42 primer (5′ CTCGGTGGTTTAGCCAGTACTA 3′), which anneals to exon C1, and the slo45 PCR primer were used detect the presence of transcripts produced from both promoter C0 or promoter C1. Neither of these primers amplify a product derived from transcripts produced from promoter C2. Promoter C2 products were detected by using the PCR primer slo43b (5′TGGCACTCGACTGCACTTGA3′) and primer slo45. The slo43b primer specifically anneals to exon C2, and therefore this primer set can be used to detect transcripts produced by this promoter C2.

Action potential recording. The recording of action potentials from the dorsal longitudinal flight muscles (DLM) was performed essentially as described by Elkins et al. (1988). Lightly etherized adults were glued to a coverslip along their ventral midline using Superglue. Flies were allowed to recover for a minimum of 1 hr before recording. The mounted fly was placed under a microscope, and two uninsulated tungsten electrodes were inserted into the brain. Current flow [generated with a Grass Instruments (Quincy, MA) S88 stimulator] through these electrodes causes activation of the giant fiber pathway and the production of action potentials in the DLM. A glass electrode was inserted into the flight muscle (2–5 MΩ, filled with 1 m NaCL) and used to record the evoked action potential spikes using a World Precision Instruments (Sarasota, FL) Electrometer Intra 767. All recordings were made in DLM indirect flight muscles c through f (Engel and Wu, 1992). All potentials were measured with reference to an uninsulated tungsten electrode inserted into the abdomen. The stimulus threshold was determined by stimulating the brain at 2 V (0.1 msec) and gradually increasing the potential until DLM spikes were observed. After a threshold voltage was determined, 0.2 V above threshold was used for the remainder of the experiment. Data were collected using a MacADIOS 8ain analog-to-digital converter (69.4 μsec/point), filtered at 14 kHz with a single-pole low-pass filter, and recorded using the Macintosh program Superscope (GW Instruments, Somerville, MA).

Sticky-feet behavioral assay. The sticky-feet behavior is elicited by overstimulating the flies using a heat pulse or a bright light delivered by a fiber optic lamp. For heat treatment, 2- to 5-d-old adult flies are trapped at the bottom of an empty glass fly vial using a foam or cotton plug and incubated at 37.7–40°C for 2–8 min. The time and temperature required to elicit the behavior seems to vary with the season but not within a season. Exposure for a few seconds to a very bright but cool light can be substituted for the heat treatment (50 W fiber optic lamp, set on high). Positive (wild-type animals) and negative (slo4 mutant animals) internal controls are always performed. After the heat pulse, the animals are gently transferred to the tabletop and not disturbed for ∼15 sec. A pencil with a pink-pearl eraser was used to push on the sides of the animals. Flies homozygous for a slowpokemutant allele hang onto the surface and allow themselves to be pushed over. Flies heterozygous for a slowpoke mutant allele will walk or fly away from the stimulus. Wild-type flies will take flight and leave the area.

Flight test. The relative ability of the 3- to 6-d-old animals to fly was measured as described previously (Benzer, 1973;Elkins et al., 1986; Green et al., 1986) with minor modifications. The walls of a pipette jar (15 cm diameter, 62 cm tall) were coated with mineral oil. A funnel was fixed on a platform at the top of the jar, and flies were dropped through the opening. The falling animals fly toward the walls of the jar and are trapped in the mineral oil. The position of each animal on the jar is marked, and then the distance of each mark from the bottom of the jar is determined. Rulers taped to the side of the jar simplify this process. Although the mineral oil seeps to the bottom of the jar, the embedded flies do not move and are stable for hours. Animals that fly well tend to cluster near the top of the jar, whereas animals that fly poorly are most often found near the bottom. Dead flies and flies that do not fly fall into the bottom of the jar and are not counted. This test can be used to distinguish wild-type animals from animals carrying a mutant slowpokeallele (Elkins et al., 1986). For each genotype, 350–1000 flies were tested. For flight testing, animals were not heat-treated.

RESULTS

Fine mapping of ash218 deletion endpoint on the slowpoke promoter map

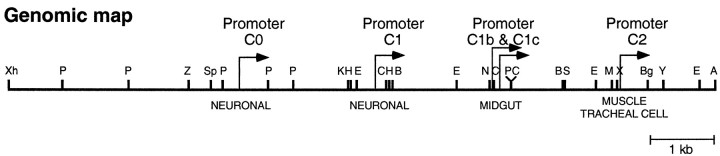

The slowpoke transcriptional control region has been well characterized using transgenes that drive the expression of a reporter gene. It has been shown that promoter C0 and C1 (Fig.1) generate slowpokeexpression in the nervous system in adult, larval, and embryonic stages, whereas promoter C2 alone is responsible for expression in muscle and tracheal cells (Bohm et al., 2000).

Fig. 1.

Map of the slowpoke transcriptional control region. The rightward-pointing arrows identify the position of five slowpoke transcriptional promoters. The labels immediately below theline identify the tissue specificity of the each promoter as determined by deletion mapping. A,ApaI; B, BamHI;Bg, BglII; C,ClaI; E, EcoRI;H, HindIII; K,KpnI; M, MunI;N, NcoI; P,PstI; S, SmaI;Sp, SpeI; X,XbaI; Xh, XhoI;Y, XmnI; Z,SphI.

The slowpoke gene is found on chromosome 3 at cytological position 96A17 (Atkinson et al., 1991). Adjacent to slowpokeis the ash2 gene in which mutations cause homeotic transformations of body parts during development. The function of theash2 gene and the phenotype of its mutant alleles are unrelated to that of the slowpoke gene. However, during the study of ash2 function, Adamson and Shearn (1996)characterized a chromosomal deletion that removed the entireash2 gene. This mutation is calledash218. Fortuitously, one endpoint of this encroached upon the slowpoke gene. Their data indicated that this deletion removed some of theslowpoke transcriptional promoters.

Our mapping data indicates that the endpoint of the deletion falls between promoter C1 and promoter C2 (data not shown) and as a consequence removes promoter C0 and promoter C1 (Fig. 1). Deletion analysis performed on a slowpoke transgene has shown that removal of these two promoters causes a loss of slowpokeexpression in the adult CNS. Muscle and tracheal cell expression, however, persists if promoter C2 and the following downstream intron are present (Brenner and Atkinson, 1996; Brenner et al., 1996). Thus, the ash218deletion has removed sequences absolutely required for adult neuronal expression but left the promoter driving muscle and tracheal expression intact.

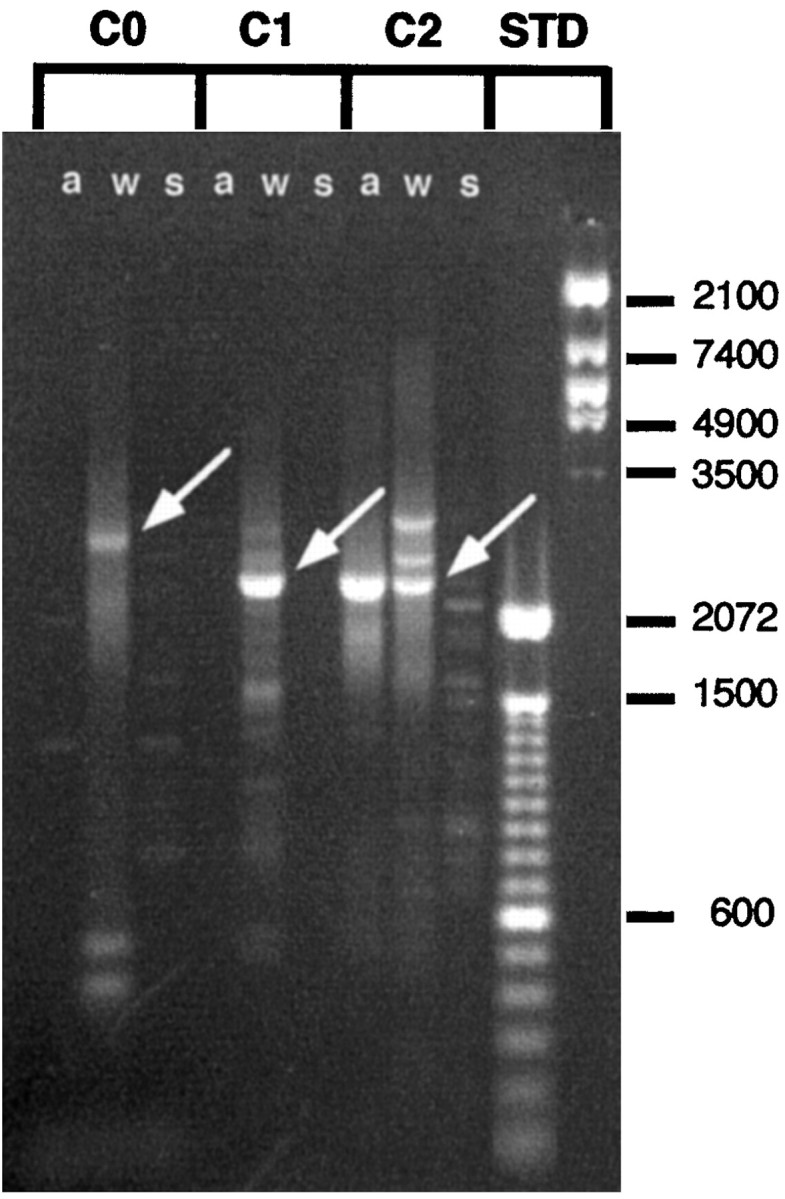

An RT-PCR assay was used to confirm that theash218 chromosome does not express the promoter C0 and C1 neuronal transcripts but does express transcripts originating from promoter C2. Each of these promoters produces a transcript that begins with a unique exon. RNA was isolated fromash218/slo4transheterozygotes. The use of the transheterozygote was necessary because the ash218 deletion is a recessive lethal mutation. Theslo4 mutant allele is a chromosome inversion with one breakpoint in the slowpoke gene. It has been shown to be a null mutation by genetic, electrophysiological, immunohistochemical, and RT-PCR criteria (Atkinson et al., 1991; Becker et al., 1995). RT-PCR was performed on wild-type,ash218/slo4, and slo4 RNA using primer sets specific for transcripts containing exon C0, C1, and C2 (Fig.2). Exon C0- and C1-containing transcripts were not detected in either theash218/slo4or the slo4 RNA. A primer set specific for exon C2-containing transcripts amplified a product fromash218/slo4RNA but not from slo4 RNA. All of the primer sets amplified a product from the wild-type RNA.

Fig. 2.

The ash218deletion eliminates expression from neuronal promoters C0 and C1 but not from the muscle–tracheal cell-specific promoter C2. The products of each promoter begins with a unique exon and can be identified by RT-PCR using exon-specific primers. Total RNA fromash218/slo4transheterozygous, wild-type, andslo4 homozygous flies was reverse transcribed, and the resultant cDNA was subjected to the PCR using the exon-specific primers. PCR products were separated in a 2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. C0,C1, and C2 identify groups of threelanes displaying products amplified using primers specific for exon C0, C1, or C2, respectively. Amplifications performed onash218/slo4, wild-type, and slo4 RNA are identified by a, w, and s, respectively. From left to right, thearrows identify PCR products diagnostic for the presence of mRNAs that include exon C0, exon C1, and exon C2, respectively. Amplification with exon C0 primers produces the 2844 nucleotide band only from wild-type RNA (lanes 1–3). The exon C1-specific primers produce the diagnostic 2406 nucleotide PCR product only from the wild-type RNA (lanes 4–6). Finally, the exon C2-specific primers amplified the diagnostic 2373 nucleotide product derived from exon C2 from bothash218/slo4and wild-type RNA but not from theslo4 RNA. Other bands are nonspecific PCR artifacts. Conditions favoring maximal sensitivity often lead to the concomitant production of spurious bands.

Action potential recordings

In Drosophila muscle, the rising phase of the regenerative action potential is generated by the influx of Ca ions through voltage-gated Ca channels (Salkoff and Wyman, 1983). The repolarization phase of the action potential is driven by the activity of at least four different outward potassium currents. These are calledIA,ICF,IK, andICS. The Shaker,slowpoke, and shab genes encode the channels that conduct IA,ICF, andIK, respectively (Baumann et al., 1987; Kamb et al., 1987; Papazian et al., 1987; Tsunoda and Salkoff, 1995; Singh and Singh, 1999). The channel that conductsICS has not yet been identified.

The electrophysiological consequences of a mutant slowpokegene have been extensively studied. Mutant slowpoke alleles eliminate the Ca-activated K current calledICF in neurons and muscle fibers (Salkoff, 1983; Elkins et al., 1986; Gho and Mallart, 1986; Singh and Wu, 1989; Komatsu et al., 1990; Saito and Wu, 1991; Broadie and Bate, 1993). In the indirect flight muscles of the adult, the loss of this potassium current has a striking electrophysiological consequence: the production of extremely broad and Bactrian camel-shaped action potentials (Elkins and Ganetzky, 1988). All of the mutantslowpoke alleles, slo1,slo2,slo3,slo4,slo5, andslo8, have been shown to eliminateICF in indirect flight muscles and to cause the same action potential phenotype (Atkinson et al., 1991).

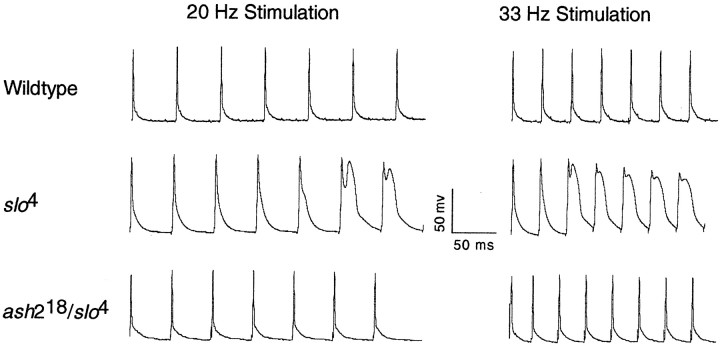

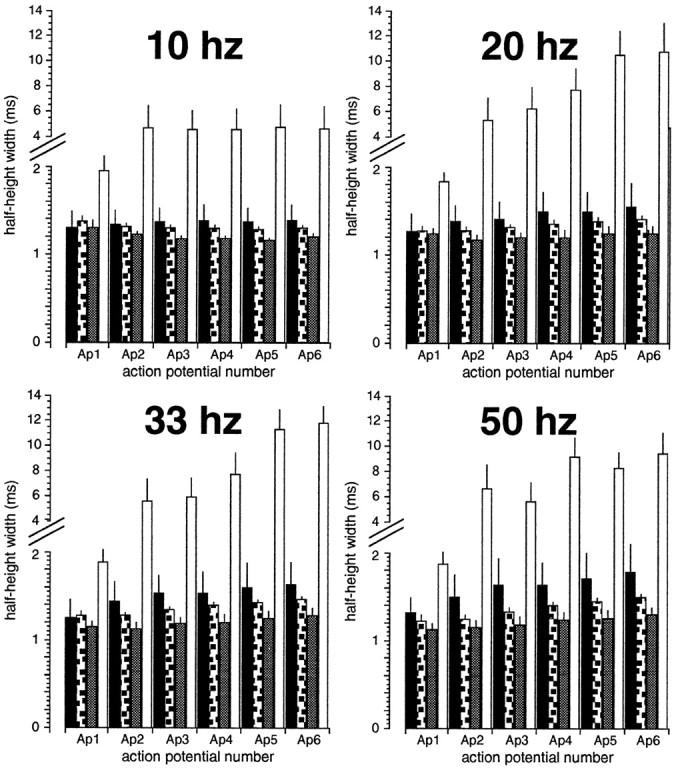

To demonstrate that the ash218chromosome produced functional slowpoke channels inDrosophila flight muscle, we examined the shape of action potentials produced by the indirect flight muscles ofash218/slo4transheterozygotes. It was not possible to assayash218 in the homozygous state because it is a recessive lethal mutation. Theslo4 mutation is a chromosomal inversion and has been shown to be a homozygous viableslowpoke null allele (Atkinson et al., 1991; Becker et al., 1995). Figure 3 shows action potentials produced from wild-type muscle, slo4homozygous muscle, andash218/slo4muscle stimulated at 20 and 33 Hz. In addition, we also examined action potentials evoked at 10 and 50 Hz (Fig.4). In all cases, wild-type andash218/slo4animals produced action potentials of normal shape and duration, whereas homozygous slo4 muscle produced broad and abnormally shaped action potentials. Therefore, in indirect flight muscle, theash218 chromosome produces functional slowpoke channels.

Fig. 3.

Action potentials produced by dorsal longitudinal flight muscles of wild-type, slo4homozygous, andash218/slo4transheterozygous animals at a stimulation frequency of 20 and 33 Hz. Wild-type muscle produces sharp action potentials at all simulation frequencies tested. Muscle homozygous for theslo4 mutation initially produces sharp action potentials, but later spikes are of abnormal shape and breadth. The ash218 deletion completely complements the slo4action potential phenotype. This indicates that theash218 deletion produces functionalslowpoke channels in Drosophilamuscle.

Fig. 4.

Broadening of dorsal longitudinal flight muscle action potentials stimulated at 10, 20, 33, and 50 Hz. The half-height width of six consecutive action potentials were measured. Width is expressed in milliseconds. Black,stippled, gray, and whitebars represent an average from wild-type animals (n= 3), slo4/+ heterozygote animals (n = 9),ash218/slo4transheterozygous animals (n = 6), andslo4 homozygous animals (n = 10), respectively. The thin line above the bar represents the SEM for each measurement. Ap1, Ap2,Ap3, Ap4, Ap5, andAp6 represents the width of the first, second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth action potentials, respectively.

Flight assay

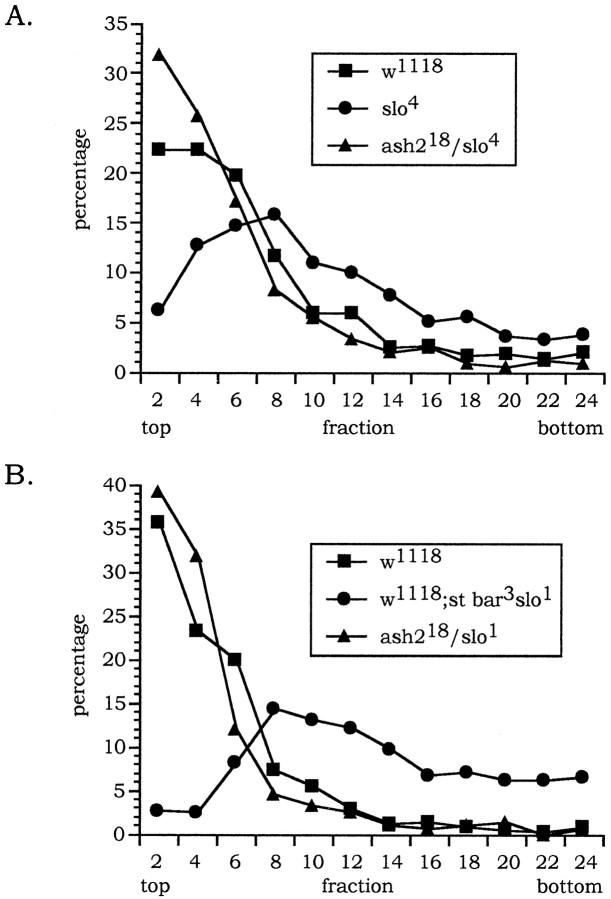

A second phenotype caused by a defect in the slowpokegene is a reduced ability of the mutant animals to fly (Elkins et al., 1986). Upon visual inspection, it is obvious that flies that carry a null mutation in the gene are very poor fliers. The slowpokemutant animals walk much of the time and fly for only very short distances. We tested the capacity of the animals for flight using a modified cylinder drop test assay (Benzer, 1973; Elkins et al., 1986;Green et al., 1986). In this assay, flies are dropped into the center of a cylinder whose walls have been coated with mineral oil. As they fall, the animals fly out from the center of the cylinder, strike the cylinder walls, and are trapped in the oil. In practice, the animals remain at the position where they first collide with the wall. Animals that fly well tend to accumulate near the top of the column, whereas animals that fly poorly are predominately found near the bottom of the column.

To determine whether the defective flight phenotype ofslowpoke mutants was associated with a muscle defect, we assayed the flight ability ofash218/slo4transheterozygotes. In this assay, these animals accumulated near the top of the column and at the same position as wild-type flies. As shown in Figure 5, theslo4 homozygotes were obviously impaired in their flying ability and accumulated in the bottom half of the column.

Fig. 5.

Column-based flight assay used to measure the relative capacity of flies for flight. Flies are dropped from a vial into the center of an oil-coated cylinder. The falling flies fly from the center and are trapped in the oil. The distance that they fall is correlated with their capacity for flight (Benzer, 1973; Elkins et al., 1986; Green et al., 1986). The column was fractionated, top to bottom, into bins 5 cm in length. The abscissa represents the distance from the top of the column that the flies fell. The ordinate is the percentage of animals assayed. A, Theash218 chromosome was tested for its capacity to complement the flight defect associated with theslo4 mutant allele. Results from an assay performed using 952 w1118, 828slo4, and 733ash218/slo4transheterozygotes. B, Ability of theash218 chromosome to complement the flight defect associated with theslo1 mutant allele. Results from an assay performed using 1002 w1118, 903 w1118; st bar3slo1,and 369ash218/st bar3slo1 flies. Thew1118 stock carries a wild-type copy of the slowpoke gene and served at the positive control. Wild-type flies (squares) and theash218/slo4orash218/slo1transheterozygotes (triangles) accumulate near the top of the column. The slo4 orslo1 homozygotes (circles) accumulate deeper in the column. Flies that did not initiate flight are not counted and are trapped in a pool of oil at the bottom of the column.

Sticky-feet phenotype

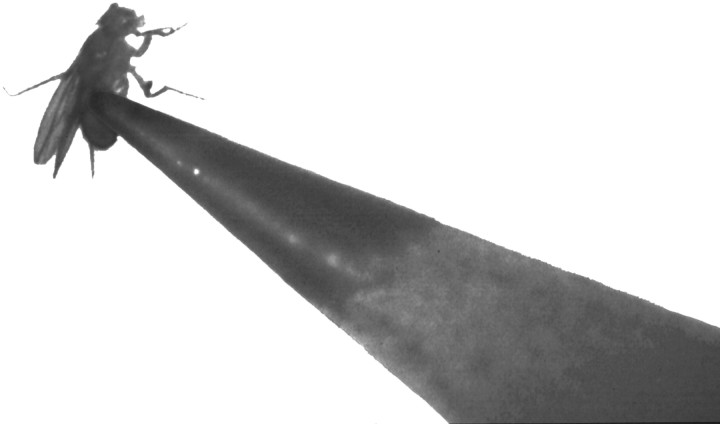

After a brief heat pulse from 22 to 37°C, flies that are homozygous for null mutations in the slowpoke gene have been described as standing motionless for several minutes (Elkins et al., 1986). This behavior is better described as a sticky-feet phenotype. Approximately 15 sec after a 2–8 min, 37–40°C heat pulse, the flies stand in place and can be pushed with a pencil. During this time, they behave as if their feet are stuck to the surface on which they stand (Fig. 6). Continuing to push the fly causes it to gradually lean over and eventually to fall onto its side or back. The flies are not paralyzed per se, because once knocked over they right themselves, after which, their feet frequently stick to the surface. If the fly is left undisturbed, this behavior can persist for many minutes. Recovery seems to be speeded by repeated touching of the fly. All of the known slowpoke null alleles (slo1,slo2,slo3,slo4,slo5, andslo8) exhibit this behavior as homozygotes and in all allelic combinations. Heterozygous and wild-type animals do not manifest this response.

Fig. 6.

An example of the sticky-feet phenotype exhibited by animals homozygous for null mutations in the slowpokegene. This particular homozygous slo4male has been exposed to a bright light (see Materials and Methods) for 15 sec and is being pushed with a number 2 pencil. Such animals do not attempt to escape or avoid the pencil and hang onto the surface on which they stand. The animal is shown leaning over in response to the pressure. With continued pressure, the animal will topple over and then in a very uncoordinated manner attempt to right himself. If successful, such an animal will usually once again exhibit the sticky-feet phenotype. Recovery from the behavior can take many minutes and seems to be speeded by repetitive stimulation.

We have also been able to elicit this behavior using a cool but very bright light. Stimulation with light evokes the behavior much more rapidly than exposure to an elevated temperature. Homozygousslo1 flies exposed to the maximal output from a 60 W fiber optic lamp elicit this behavior in 15 sec. During this time, no change in temperature of the platform was observed. Based on this result, we postulate that the sticky-feet behavior is induced not by temperature but by overstimulation of the animals.

The ash218 deletion removes promoters C0 and C1 (neural-specific) but leaves promoter C2 intact (muscle and tracheal cell-specific). This provides us with the opportunity to determine whether the sticky-feet behavior arises from a lack of expression in muscle or neural tissue. Flies carrying a single copy of the ash218 andslo4 mutant chromosomes were behaviorally tested. Animals that walked or flew away when pushed on with a pencil were scored as exhibiting wild-type behavior.

Flies carrying a single copy of theash218 andslo4 mutant chromosomes were produced by crossing yw;ash218, red,e/y + TM3 Sb Ser virgin females to slo4males. The genotypes of these animals were (1) yw;ash218/slo4male, (2) yw;slo4/y+,TM3Sb Ser male, (3) yw/+;ash218/slo4female, and (4) yw/+;slo4/y+TM3Sb Ser female. Although all of the progeny were behaviorally scored, the data reported here was collected only from females. The males were excluded because behavioral testing of the males could not be performed as a blind assay because theash218/slo4transheterozygote and slo4heterozygote males can be distinguished with the naked eye based on their body color. However, detection of the physical markers that distinguish the transheterozygote and heterozygote females require substantial magnification and therefore permit an unbiased behavioral assay to be performed.

A total of 516 females were examined. None of the 238 yw/+;slo4/y+TM3 Sb Ser animals showed the sticky-feet phenotype and were behaviorally scored as wild type. Of the remaining yw/+;ash218/slo4animals, 254 were scored as exhibiting the sticky-feet phenotype, and 24 were scored as exhibiting wild-type behavior. As a control, we performed the behavioral assay on 258slo4 animals. Of these, 230 were scored as having the sticky-feet phenotype and 28 were scored as wild type. It is common for us to have a 10% mis-scoring rate for theslo4 homozygous parental stock. Therefore, we conclude that theash218 mutation fails to complement this slowpoke behavioral phenotype.

DISCUSSION

Mutations in the slowpoke gene have pleiotropic effects on animal physiology and behavior. In both muscles and neurons,slowpoke mutations have been shown to eliminate the BK-type Ca-activated K current called ICF(Salkoff, 1983; Elkins et al., 1986; Gho and Mallart, 1986; Singh and Wu, 1989; Komatsu et al., 1990; Saito and Wu, 1991; Broadie and Bate, 1993). In muscles, a slowpoke null allele alters the shape and duration of the flight muscle action potentials (Elkins et al., 1986; Elkins and Ganetzky, 1988). In neurons, the same mutation affects not only the action potentials shape (Saito and Wu, 1991) but also the release of neurotransmitter from motoneurons (Gho and Ganetzky, 1992;Warbington et al., 1996) and the habituation of a neuronal circuit in the adult CNS (Engel and Wu, 1998). This indicates thatslowpoke channels are of central importance for the normal function of both neurons and muscle fibers.

During repetitive stimulation of the flight muscle, wild-type animals produce trains of well formed action potentials. Animals homozygous for a slowpoke null mutation produce extremely broad action potential spikes. In a train of action potentials, the first spike is typically of normal breadth. Subsequent spikes, however, are typically extremely broad and often have two peaks. In slowpokemutants, it is believed that a current calledIA, conducted by theShaker-encoded voltage-gated K channel, is responsible for repolarization of the first spike (Elkins and Ganetzky, 1988). The voltage-dependent inactivation of this current reduces its contribution to the repolarization of subsequent spikes. In wild-type muscle, theslowpoke-encoded channels ensure the rapid repolarization of subsequent spikes. However, in muscle lacking a functionalslowpoke gene, the subsequent spikes cannot be properly repolarized.

Animals carrying null mutations in the slowpoke gene also present behavioral phenotypes. Although the animals are very healthy and fecund, they are relatively lethargic and have a limited capacity for flight. They also manifest a temperature- or light-induced sticky-feet phenotype. A priori, one cannot predict whether these behavioral traits have a neuronal or muscular origin. Previous studies of the slowpoke transcriptional control region indicates that neuronal and muscle expression arise from different promoters, which are separated by >3.7 kb of genomic DNA (Brenner and Atkinson, 1996; Brenner et al., 1996). An ideal tool for identifying the origin of the sticky-feet and flight phenotypes would be a mutant lesion that affected either the neuronal or muscle promoters but not both. The ash218 deletion provides just such a tool. This deletion removes the neighboring ash2 gene and the neuronal promoters of the slowpoke gene. The portion that remains intact includes promoter C2 and other sequences required for muscle expression (Brenner and Atkinson, 1996; Brenner et al., 1996). Therefore, theash218 deletion should also be viewed as a slowpoke mutation that eliminates neuronalslowpoke expression. In addition, because theash218 deletion does not involve the slowpoke coding region, the BK channels expressed by the chromosome should be fully functional.

As an aside, the ash218deletion also allows us to determine the orientation of theslowpoke gene on Drosophila chromosome 3. Genetic mapping indicates that slowpoke (genetic position 3–86) is distal to ash2 (genetic map position 3–78.6). That is, theslowpoke locus is farther from the centromere that theash2 locus. Theash218 deletion removes bothash2 and a portion of the slowpoke transcription control region but not the slowpoke coding region. Therefore, the 5′ end of slowpoke transcription unit must be closer to ash2 than the 3′ end of the transcription unit, which means that slowpoke is positioned on chromosome 3 such that transcription proceeds away from the centromere.

As predicted, the ash218chromosome complements the slo4mutant muscle phenotype with regard to its electrophysiological abnormality. Furthermore, the restoration of electrical properties is correlated with a restoration of normal flight. This strongly suggests that the flight defect in animals carrying slowpoke null mutations is caused solely by an absence of BK-type channels in muscle and the resultant abnormalities in the electrical character of the muscle fiber. Satisfyingly, a phenotype suspected to be neuronal in origin is not complemented by theash218 chromosome; that is, theash218/slo4transheterozygotes exhibit a robust sticky-feet phenotype.

The sticky-feet phenotype is an extremely unusual behavior. It is triggered by both heat and bright light, suggesting that it is a direct response to overstimulation of the animal. The persistence of the behavior for many minutes after the stimulus ends suggests that the affected cells enter a prolonged state of inappropriate activity. Such a response might be caused by seizure-like activity within a circuit involved in evoking a reflex behavior.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant IBN-9724088 to N.S.A.

Correspondence should be addressed to Nigel S. Atkinson, Section of Neurobiology, Patterson Building, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712-1064. E-mail: nigela@mail.utexas.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamson AL, Shearn A. Molecular genetic analysis of Drosophila ash2, a member of the trithorax group required for imaginal disc pattern formation. Genetics. 1996;144:621–633. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.2.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adelman JP, Shen KZ, Kavanaugh MP, Warren RA, Wu YN, Lagrutta A, Bond CT, North RA. Calcium-activated potassium channels expressed from cloned complementary DNAs. Neuron. 1992;9:209–216. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90160-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson NS, Robertson GA, Ganetzky B. A component of calcium-activated potassium channels encoded by the Drosophila slo locus. Science. 1991;253:551–555. doi: 10.1126/science.1857984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumann A, Krah-Jentgens I, Müller R, Müller-Holtkamp F, Seidel R, Kecskemethy N, Casal J, Ferrus A, Pongs O. Molecular organization of the maternal effect region of the Shaker complex of Drosophila: characterization of an IA channel transcript with homology to vertebrate Na+ channel. EMBO J. 1987;6:3419–3429. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker MN, Brenner R, Atkinson NS. Tissue-specific expression of a Drosophila calcium-activated potassium channel. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6250–6259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-06250.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benzer S. Genetic dissection of behavior. Sci Am. 1973;229:24–37. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1273-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohm RA, Brenner R, Wang B, Atkinson N. Transcriptional control of Ca-activated K channel expression: identification of a second, evolutionarily-conserved, neuronal promoter. J Exp Biol. 2000;203:693–704. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.4.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner R, Atkinson N. Developmental and eye-specific transcriptional control elements in an intronic region of a Ca2+-activated K+ channel gene. Dev Biol. 1996;177:536–543. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner R, Atkinson NS. Calcium-activated potassium channel gene expression in the midgut of Drosophila. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;118:411–420. doi: 10.1016/s0305-0491(97)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenner R, Thomas TO, Becker MN, Atkinson NS. Tissue-specific expression of a Ca2+-activated K+ channel is controlled by multiple upstream regulatory elements. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1827–1835. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01827.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broadie KS, Bate M. Development of larval muscle properties in the embryonic myotubes of Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurosci. 1993;13:167–180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-01-00167.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elkins T, Ganetzky B. The roles of potassium currents in Drosophila flight muscles. J Neurosci. 1988;8:428–434. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-02-00428.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elkins T, Ganetzky B, Wu C-F. A Drosophila mutation that eliminates a calcium-dependent potassium current. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8415–8419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engel JE, Wu C-F. Interactions of membrane excitability mutations affecting potassium and sodium currents in the flight and giant fiber escape systems of Drosophila. J Comp Physiol [A] 1992;171:93–104. doi: 10.1007/BF00195964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engel JE, Wu C-F. Genetic dissection of functional contributions of specific potassium channel subunits in habituation of an escape circuit in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2254–2267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-02254.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gho M, Ganetzky B. Analysis of repolarization of presynaptic motor terminals in Drosophila larvae using potassium-channel-blocking drugs and mutations. J Exp Biol. 1992;170:93–111. doi: 10.1242/jeb.170.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gho M, Mallart A. Two distinct calcium-activated potassium currents in larval muscle fibres of Drosophila melanogaster. Pflügers Arch. 1986;407:526–533. doi: 10.1007/BF00657511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green CC, Sparrow JC, Ball E. Flight testing columns. Drosophila Information Service. 1986;63:141. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamb A, Iverson LE, Tanouye MA. Molecular characterization of Shaker, a Drosophila gene that encodes a potassium channel. Cell. 1987;50:405–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90494-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komatsu A, Singh S, Rathe P, Wu C-F. Mutational and gene dosage analysis of calcium-activated potassium channels in Drosophila: correlation of micro- and macroscopic currents. Neuron. 1990;4:313–321. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90105-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pacha J, Frindt G, Sackin H, Palmer LG. Apical maxi K channels in intercalated cells of CCT. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:F696–F705. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.261.4.F696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papazian DM, Schwarz TL, Tempel BL, Jan YN, Jan LY. Cloning of genomic and complementary DNA from Shaker a putative potassium channel gene from Drosophila. Science. 1987;238:749–753. doi: 10.1126/science.2441470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saito M, Wu C-F. Expression of ion channels and mutational effects in giant Drosophila neurons differentiated from cell division-arrested embryonic neuroblasts. J Neurosci. 1991;11:2135–2150. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-07-02135.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salkoff L. Drosophila mutants reveal two components of fast outward current. Nature. 1983;302:249–251. doi: 10.1038/302249a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salkoff LB, Wyman RJ. Ion currents in Drosophila flight muscles. J Physiol (Lond) 1983;337:687–709. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh A, Singh S. Unmasking of a novel potassium current in Drosophila by a mutation and drugs. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6838–6843. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-16-06838.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh S, Wu C-F. Complete separation of four potassium currents in Drosophila. Neuron. 1989;2:1325–1329. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stoner LC, Morley GE. Effect of basolateral or apical hyposmolarity on apical maxi K channels of everted rat collecting tubule. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:F569–F580. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.268.4.F569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsunoda S, Salkoff L. The major delayed rectifier in both Drosophila neurons and muscle is encoded by Shab. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5209–5221. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-05209.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warbington L, Hillman T, Adams C, Stern M. Reduced transmitter release conferred by mutations in the slowpoke-encoded Ca2(+)-activated K+ channel gene of Drosophila. Invert Neurosci. 1996;2:51–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02336660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei A, Jegla T, Salkoff L. Eight potassium channel families revealed by the C. elegans genome project. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:805–829. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(96)00126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]