Abstract

Angiotensin II (AngII) receptors couple to a multitude of different types of G-proteins resulting in activation of numerous signaling pathways. In this study we examined the consequences of this promiscuous G-protein coupling on secretion. Chromaffin cells were voltage-clamped at −80 mV in perforated-patch configuration, and Ca2+-dependent exocytosis was evoked with brief voltage steps to +20 mV. Vesicle fusion was monitored by changes in membrane capacitance (ΔCm), and released catecholamine was detected with single-cell amperometry. Ca2+ signaling was studied by recording voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents (ICa) and by measuring intracellular Ca2+([Ca2+]i) with fura-2 AM.

AngII inhibited ICa (IC50 = 0.3 nm) in a voltage-dependent, pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive manner consistent with Gi/o-protein coupling to Ca2+ channels. ΔCm was modulated bi-directionally; subnanomolar AngII inhibited depolarization-evoked exocytosis, whereas higher concentrations, in spite of ICainhibition, potentiated ΔCm fivefold (EC50 = 3.4 nm). Potentiation of exocytosis by AngII involved activation of phospholipase C (PLC) and Ca2+ mobilization from internal stores. PTX treatment did not affect AngII-dependent Ca2+mobilization or facilitation of exocytosis. However, protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitors decreased the facilitatory effects but not the inhibitory effects of AngII on stimulus-secretion coupling. The AngII type 1 receptor (AT1R) antagonist losartan blocked both inhibition and facilitation of secretion by AngII. The results of this study show that activation of multiple types of G-proteins and transduction pathways by a single neuromodulator acting through one receptor type can produce concentration-dependent, bi-directional regulation of exocytosis.

Keywords: angiotensin II, G-protein-coupled receptor, calcium channels, intracellular calcium stores, protein kinase C, phospholipase C, pertussis toxin, exocytosis, chromaffin cells

Modulation of neurotransmitter release and hormone secretion via activation of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) is a key element in information processing within an organism. To understand how secretion is modulated, it is important to characterize the mechanisms underlying GPCR regulation of ion channels, Ca2+ signaling, and the exocytotic machinery. Given the divergence and convergence of downstream signaling cascades modulated by G-protein subunits (Gudermann et al., 1996), the effects of a single neuromodulator on regulated exocytosis may be complex and variable depending on stimulus conditions.

GPCRs have been postulated to modulate neurotransmission either through an effect on membrane excitability and Ca2+ signaling or via second messenger-mediated changes in the activity of the proteins controlling exocytosis (Wu and Saggau, 1997; Miller, 1998). The inaccessibility of most mammalian nerve terminals makes direct investigation of stimulus-secretion coupling and its modulation difficult. However, such studies can be performed on neuroendocrine cells where the Ca2+ signals regulating exocytosis may be controlled and monitored and vesicle fusion assessed directly using membrane capacitance measurements and amperometry (Neher, 1998). With such an approach, previous studies have shown that activity-dependent changes in exocytosis are mediated by Ca2+and protein kinase C (PKC) (Smith et al., 1998). The aim of this study was to examine the mechanism(s) underlying GPCR modulation of exocytosis. We studied the effects of angiotensin II (AngII) on secretion because (1) it is well established that this peptide modulates catecholamine release from neurons and chromaffin cells (Feldberg and Lewis, 1964; Bottari et al., 1993), and (2) AngII type 1 receptors (AT1Rs) are coupled to a plethora of different types of G-protein (Richards et al., 1999). How AT1R signaling pathways modulate exocytosis is unknown.

We combined voltage-clamp, ΔCm, ratiometric fluorescence, and electrochemical techniques on single cells to examine directly the effects of AngII on stimulus-secretion coupling in adrenal chromaffin cells. We show that subnanomolar AngII inhibits Ca2+ influx and vesicle fusion via a Gi/o-dependent pathway. At higher concentrations, the inhibitory effects of AngII are surmounted, producing an increase in exocytosis. The facilitatory effects of AngII are pertussis toxin (PTX)-insensitive and are associated with activation of phospholipase C (PLC), store-dependent rise in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), and activation of PKC. The results of this study show that GPCR regulation of multiple signaling pathways may produce antagonistic modulation of neurotransmitter release.

Some preliminary data have been published previously in abstract form (Teschemacher et al., 1998).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chromaffin cell culture. Chromaffin cells were dissociated as described previously (Seward and Nowycky, 1996). Adrenal glands from 18- to 24-month-old cows were obtained from a local abattoir and were retrogradely perfused at 25 ml/min for 30 min at 37°C with the digestive enzymes 0.03% collagenase type 2 (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ) and 0.001% DNase I (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) added to a Locke's solution consisting of (in mm): 154.2 NaCl, 2.6 KCl, 2.2 K2HPO4, 0.85 KH2PO4, 10 glucose, 5 HEPES; 0.0005% Phenol Red (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK); pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH. After surgical removal of the cortex, the medulla was dissected and dissociated with fresh enzyme solution for 30 min at 37°C. After this incubation, cells were transferred to Earle's balanced salt solution (Life Technologies), centrifuged twice at 50 × g for 15 min, and resuspended in DMEM (Life Technologies) supplemented with 44 mmNaHCO3 and 15 mm HEPES, 10% fetal calf serum (Life Technologies), 0.5 mmglutamine, and 0.01% penicillin–streptomycin solution. Cells were plated on glass coverslips coated with matrigel (Becton Dickinson Labware, Bedford, MA) at an approximate density of 800 cells/mm2. The medium was replaced 24 hr after plating, and cells were maintained for up to 7 d in a humidified atmosphere of 95% O2/5% CO2 at 37°C. Some cultures were treated with 250 ng/ml PTX (Sigma, Poole, UK) at 37°C for 24 hr.

Electrophysiology. A coverslip carrying chromaffin cells was placed in a microperfusion chamber on the stage of an inverted phase-contrast Axiovert 100 microscope equipped with a 40× oil-immersion objective with a numerical aperture of 1.3 (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Cells were continuously superfused at 1.5 ml/min with an external solution consisting of (in mm): 140 NaCl, 2 KCl, 0.5 NaHCO3, 1 MgCl2, 2.5 CaCl2, 10 d-glucose, 10 HEPES; pH adjusted to 7.3 with NaOH. Ionic currents were recorded in perforated-patch-clamp configurations using borosilicate glass electrodes coated with Sylgard 184 (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) and fire-polished to a resistance of 1–2 MΩ. Electrodes were filled with a solution consisting of (in mm): 145 Cs-glutamate (Calbiochem, Nottingham, UK), 9.5 NaCl, 0.3 BAPTA (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and 10 HEPES; pH adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH (ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, OH). For perforated-patch recording experiments, gramicidin D (Sigma) at a final concentration of 65 μg/ml [with 0.9% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) as solvent] was added. Series resistance was <12 MΩ and compensated (typically >70%) electronically using a patch-clamp amplifier (Axopatch 200B; Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Voltage protocol generation and data acquisition were performed using custom data acquisition software (kindly provided by Dr. A. P. Fox, University of Chicago) running on a Pentium computer equipped with a Digidata 1200 acquisition board (Axon Instruments). Current traces were low-pass-filtered at 5 kHz using the four-pole Bessel filter supplied with the amplifier and digitized at 10 kHz. Current traces were corrected off-line for linear leakage current (typically <10 pA, at −80 mV) using the P4 method. Chromaffin cells were voltage-clamped at −80 mV, andCm was sampled with a resolution of 12 msec using a software-based phase-tracking method as described previously (Seward et al., 1995). Exocytosis was evoked every 25 sec with a voltage step to +20 mV of a fixed duration, which elicited a reproducible ΔCm of 50–100 fF (see below). Cm sampling was resumed 40 msec after the stimulus to exclude gating charge artifacts (Horrigan and Bookman, 1994). Data were stored on the computer hard drive and analyzed off-line (Axobasic; Excel, Microsoft; Origin, Microcal). Unless otherwise indicated, Ca2+ influx was quantified by integrating ICa, omitting the first 2 msec, which were contaminated by Na+ currents. ΔCm was measured relative to a 100 fF calibration signal that was routinely switched in and out of the circuit during the course of a recording. All experiments were performed at ambient temperature (21–25°C).

[Ca2+]i measurements. Cells were preloaded with Ca2+ indicator by incubating for 25 min at 37°C in DMEM medium containing 5 μm fura-2 AM (Molecular Probes) followed by washing with fresh DMEM and incubating for a further 15 min. Chromaffin cells were alternately illuminated at 340 and 380 nm using a monochromator (TILL Photonics, Martinsried, Germany) controlled by theCm data acquisition software. Emission >430 nm was collected with a photomultiplier tube (TILL Photonics) and sampled every 12 msec. Data were stored on PC and ratios of 340/380 nm were calculated off-line (Axobasic-written software; Excel, Microsoft). Calibration of fura-2 AM was performed by the method of Grynkiewicz et al. (1985). Rmin andRmax andSf2/Sb2were obtained by permeabilizing chromaffin cells with 10 μm ionomycin or 3 μmdigitonin in the presence of 10 mm EGTA or 20 mm Ca2+, respectively.

Electrochemical catecholamine detection. Catecholamine release was detected by single-cell amperometry according to the method described by Schulte and Chow (1998). Carbon fiber probes (5 μm diameter; ALA Scientific Instruments, New York, NY) were charged to +800 mV and brought into contact with the plasma membrane of chromaffin cells that were voltage-clamped in perforated-patch-clamp configuration. Currents were measured and low-pass-filtered at 3 kHz using a VA-10 amplifier (npi electronics, Hamm, Germany) and digitized at 5 kHz with commercial software (pCLAMP,Axon Instruments) running on a second Pentium computer equipped with a Digidata 1200 data acquisition board (Axon Instruments). At the end of each experiment, the quality of the carbon fiber electrode and the ability of a chromaffin cell to produce amperometric signals were verified by application of high concentrations of nicotine or by rupturing the cell membrane. Amperometric events were analyzed by software developed by S. Kasparov (University of Bristol). Individual events with a rapid rise-time (<0.5 pA/msec) and integrated charge >30 fC were automatically detected by the software and summed for the duration (25 sec) of the corresponding capacitance trace.

Drug application. All drugs were added to the superfusing external solution. Because of the prominent desensitization of responses at >1 nm AngII, unless stated otherwise, only one agonist application was made per coverslip. The specific nonpeptide AngII receptor antagonists losartan (kind donation from Merck, Sharp & Dohme, Hertfordshire, UK) and PD 123,319 (RBI, Natick, MA) were applied for 2 min before and during AngII treatment. All drugs were made up as stock solutions and stored in aliquots at −20°C. A fresh aliquot was used for each experiment and diluted at least 1000-fold. U-73122, U-73443 (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA), Calphostin C (Biomol), and bisindolylmaleimide (BIS; Calbiochem, Nottingham, UK) were solved in DMSO. Cyclopiazonic acid (CPA; Calbiochem) was dissolved in chloroform.

Because of the transient nature of responses to AngII, percentile changes of parameters under investigation were obtained by relating maximal deflections after drug application to the average of four measurements immediately preceding treatment. All results are presented as mean ± SEM. Unless stated otherwise in the text, changes were tested with Student's paired t test. Statistical significance was accepted at a level of p < 0.05. A total of 135 chromaffin cells from 35 cultures were used in this study. Of these, seven recordings from three cultures were excluded because they failed to show any response to AngII.

RESULTS

AngII inhibition of ICa in chromaffin cells

Ca2+ entry through voltage-operated Ca2+ channels (VOCCs) regulates depolarization-evoked exocytosis in neurons and chromaffin cells. GPCRs are known to modulate VOCCs either through a well characterized, ubiquitous membrane-delimited pathway or through an undefined second-messenger mediated pathway(s) (Hille, 1994; Dolphin, 1998). To gain insight into the mechanisms underlying modulation of exocytosis by AT1Rs, in our first series of experiments we investigated the effect of AngII on VOCCs in chromaffin cells. All of our studies were performed using the perforated-patch configuration to avoid dialysis of agonist-induced changes in diffusable second messengers and rundown ofICa and exocytosis (Seward and Nowycky, 1996). Furthermore, we used Ca2+as the divalent cation to retain normal Ca2+ homeostasis pathways and to maintain the function of Ca2+-dependent proteins important in cell signaling and exocytosis (Seward et al., 1996).

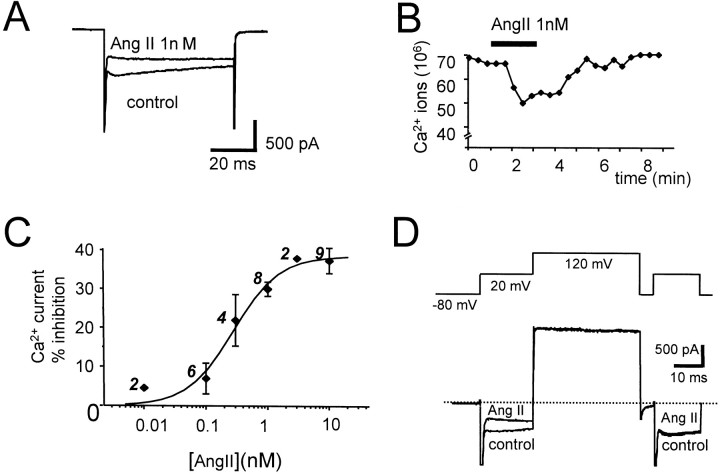

Superfusion of AngII for 2–3 min produced a reversible inhibition ofICa (Fig.1A,B). The concentration–response curve for AngII inhibition of Ca2+ entry (determined by integration ofICa; see Materials and Methods) had an IC50 of 0.28 nm, a maximum of 39 ± 3% at 10 nm, and a Hill slope of 1.18 (Fig. 1C). At 100 nm, the inhibition of ICa was reduced to 30 ± 3% (n = 16). In eight cells, a second application of 100 nm AngII after 10 min wash failed to inhibit ICa, suggesting that AT1Rs in chromaffin cells undergo rapid and profound desensitization similar to that reported previously (Wang et al., 1994; Oppermann et al., 1996). Characterization of this desensitization is beyond the scope of the present study and was not pursued further; in all subsequent experiments, responses to only the first application of AngII are reported.

Fig. 1.

AngII inhibition of ICain bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. A, Superimposed current traces evoked by 60 msec voltage steps to +20 mV in a cell clamped at −80 mV in perforated-patch configuration. Currents were recorded immediately before (control) and during superfusion of AngII (1 nm) as indicated. The transient current observed during the first 3 msec of the voltage step is attributable to activation of Na+ channels; this is followed by a more sustained inward current resulting from activation of VOCCs. AngII inhibition of ICa decreased during the voltage step. B, Time course of the inhibition of Ca2+ influx during superfusion with AngII (indicated by bar above the data). Data are from a single cell. Ca2+ influx was calculated by integration ofICa. C, Concentration–response curve for AngII inhibition of Ca2+ influx. Each point is the mean percentage inhibition of Ca2+ entry ± SEM for the number of cells indicated. Solid line through the data represents the best fit of pooled data (0.01–10 nm) with the Hill equation, giving an IC50 of 0.28 nmand Hill coefficient of 1.18. D, Large depolarizing prepulses reversed the inhibition of ICa by AngII. The top trace is a schematic representation of the voltage protocol used to evoke the superimposed currents shown below before (control) and during superfusion with 10 nm AngII.

Inhibition of neuronal VOCCs by Gβγ-subunits via a “membrane-delimited” pathway is voltage dependent and typified by a slowing of activation kinetics and time-dependent recovery during depolarization (Dolphin, 1998). The inhibition ofICa produced by 1 nm AngII in chromaffin cells was found to decrease from 36.0 ± 3.2% at the peak to 25.6 ± 2.3% during a 30 msec depolarization to +20 mV (n = 5). Application of a large depolarizing prepulse to +120 mV for 40 msec before the test pulse reduced the AngII inhibition ofICa from 40.8 ± 3.6 to 2.6 ± 4.7% (10 nm; n = 4) (Fig.1D). Treatment of cells with PTX abolished the effects of AngII on ICa (see Fig.8C). No evidence for a voltage-independent inhibition ofICa by AngII as described for sympathetic neurons (Shapiro et al., 1994) nor any facilitation ofICa as described for sensory neurons (Bacal and Kunze, 1994) was observed in chromaffin cells. The subtype of receptor mediating the effects of AngII on VOCCs was determined using specific antagonists (Hunyady et al., 1996). The AT1R antagonist losartan (10 μm) abolishedICa inhibition by AngII (100 nm, n = 8), whereas the specific AngII type 2 receptor antagonist PD123,319 (10 μm, n = 5) did not (see Fig.8C). Taken together, these results show that in chromaffin cells AngII acts via a Gi/o-protein coupled to AT1Rs to inhibit VOCCs through a voltage-dependent mechanism.

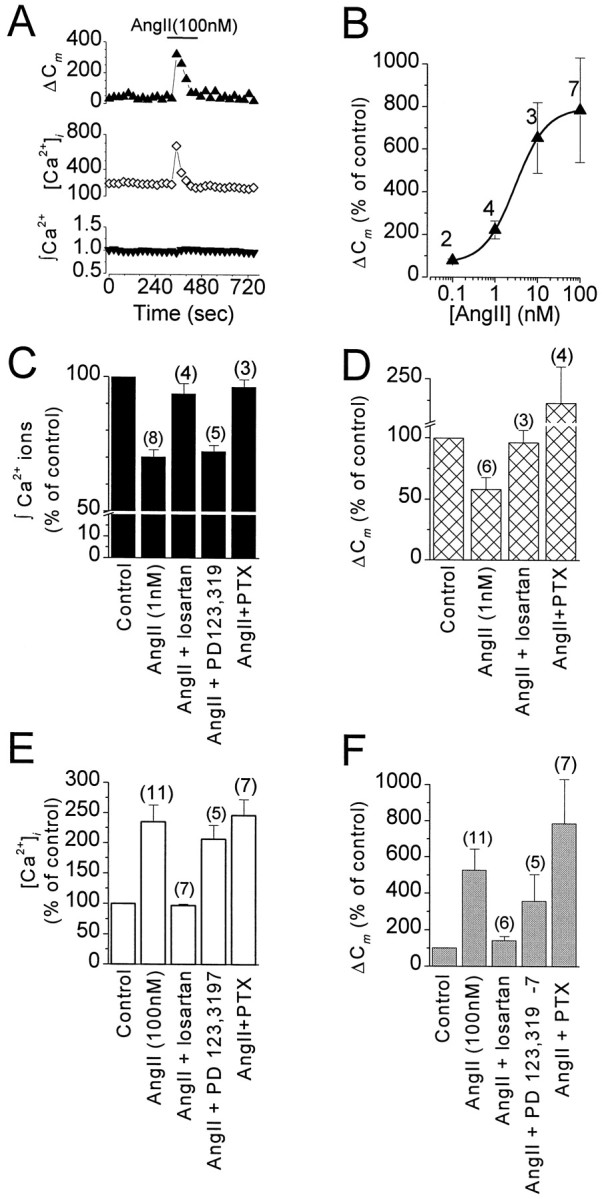

Fig. 8.

AT1Rs activate multiple G-proteins and divergent transduction pathways to inhibit and facilitate exocytosis.A, PTX treatment does not block the facilitatory effects of AngII (100 nm) on stimulus-secretion coupling. Data from a single cell showing ΔCm(top) evoked by voltage steps to +20 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV given every 25 sec, [Ca2+]i (middle) measured immediately before each voltage step, and integrated Ca2+ influx (bottom) in response to each stimulus plotted against time. AngII (indicated bybar) increased basal [Ca2+]i from 230 to 670 nmand potentiated ΔCm but did not inhibit Ca2+ influx. B, Concentration–response curve of ΔCmpotentiation by AngII in cells treated with PTX. Eachpoint represents the mean ± SEM for the number of experiments indicated. The solid line drawn through the data represents the best fit with the Hill equation of pooled data with an EC50 3.4 nm and Hill coefficient 1.30.C–F, Summary of the pharmacology of the inhibitory and facilitatory effects of AngII on stimulus-secretion coupling in chromaffin cells. Data values are the means ± SEM for the number of cells indicated above each bar. The AT1R antagonist losartan but not the AT2R antagonist PD123,319 abolished both the inhibitory and facilitatory effects of AngII; PTX treatment abolished only the inhibitory effects. C, Drug effects on voltage-stimulated integrated Ca2+ entry. PTX abolished ICa inhibition. D, Drug effects on the inhibitory effects of AngII (1 nm) on exocytosis. E, Drug effects on AngII-induced (100 nm) changes in [Ca2+]i.F, Drug effects on AngII (100 nm)-dependent facilitation of exocytosis.

Bidirectional, concentration-dependent modulation of exocytosis by AngII

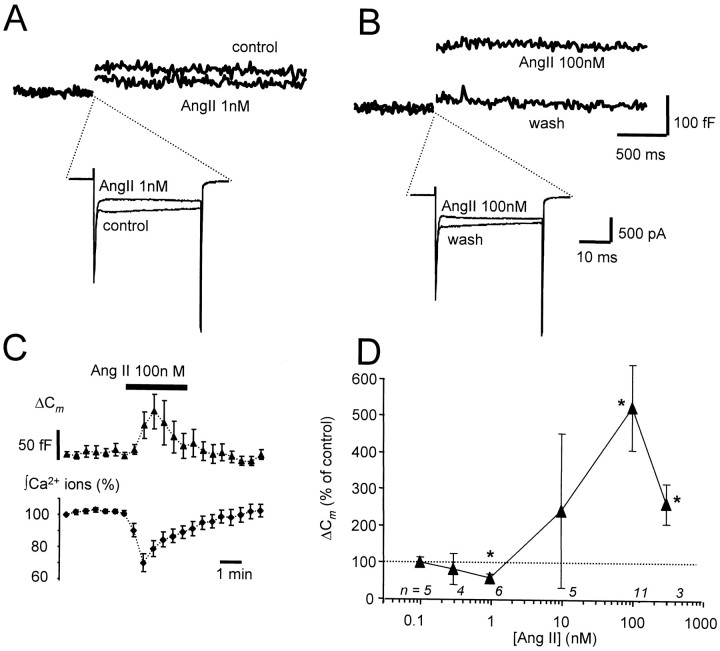

Cm is proportional to cell surface area and is increasingly used as a method for monitoring exocytosis with exquisite resolution. Fusion and endocytosis of vesicles are observed as increases and decreases inCm, respectively. To examine the effects of AngII on secretion, cells were stimulated every 25 sec with voltage steps to +20 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV. Before drug application, the step duration was adjusted to between 30 and 60 msec to achieve a reproducible ΔCmof 50–100 fF. This stimulus paradigm avoids depletion of the readily releasable pool (RRP) (Smith et al., 1998) and activity-dependent changes in exocytotic efficiency (Engisch et al., 1997). Application of 1 nm AngII produced concomitant inhibition of Ca2+ entry (30 ± 2%) and ΔCm (42 ± 9%;n = 6) (Fig.2A); however, the inhibition of exocytosis by AngII did not produce a significant change in exocytotic efficiency (ΔCm/∫ Ca2+ ions) (92 ± 6% of control,n = 6), suggesting that at this concentration AngII does not alter the Ca2+ dependence of exocytosis. At higher AngII concentrations (100 nm), Cmincreases were no longer inhibited but potentiated to 524 ± 118% of control (n = 11) despite inhibition of Ca2+ entry by 31 ± 3% (Fig.2B,C). The exocytotic efficiency was facilitated to 819 ± 291% of control (n = 11) (Table 1). The facilitatory effect of AngII on secretion was transient, and its onset either coincided with (n = 8) or was delayed by up to 1 min with respect to ICa inhibition (n = 3) (Fig.2C). At the intermediate concentration of 10 nm, the effect of AngII on ΔCm was highly variable from cell to cell, resulting in either inhibition (40% of cells) or potentiation (60% of cells) (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Bimodal concentration-dependent modulation of stimulus-evoked exocytosis by AngII. A, Inhibition of stimulus-evoked exocytosis by low concentrations of AngII. SuperimposedICa and corresponding ΔCm traces evoked by 30 msec voltage steps to +20 mV before (control) and during application of AngII (1 nm). B, In the same cell, subsequent application of AngII (100 nm) potentiated ΔCm (top right) while still depressing ICa. The traces markedwash were recorded 10 min after AngII (1 nm) treatment had terminated and serve as controls for the AngII (100 nm) measurements. C, Diary plots of the effect of 100 nm AngII on normalized ΔCm and Ca2+ entry as measured by integrating ICa (data plotted are mean ± SEM for 8 cells). Note that the potentiation of ΔCm and inhibition of Ca2+ influx are not maintained throughout the 3 min period of agonist application (indicated by bar).D, Concentration dependence of ΔCm modulation by AngII. Eachpoint represents the mean ± SEM for the number of experiments shown below each point; asterisks indicate significant difference from control (p < 0.05; Student's paired t test).

Table 1.

Role of store-released Ca2+ and PKC in modulation of stimulus-evoked exocytosis by AngII

| Exocytotic efficiency | ||

|---|---|---|

| (% of control) | n | |

| AngII (1 nm) | 92 ± 6 | 6 |

| AngII (100 nm) | 819 ± 291* | 11 |

| Caffeine (50 mm) | 288 ± 129 | 3 |

| PMA (50 nm) | 431 ± 73* | 5 |

| CPA (3 μm) + AngII (100 nm) | 171 ± 20 | 3 |

| U-73443 (1 μm) + AngII (100 nm) | 804 ± 351* | 3 |

| U-73122 (1 μm) + AngII (100 nm) | 138 ± 57 | 5 |

| Calphostin C (100 nm) + AngII (100 nm) | 116 ± 35 | 7 |

| BIS (500 nm) + AngII (100 nm) | 300 ± 125* | 5 |

| PTX + AngII (100 nm) | 810 ± 261* | 7 |

Exocytotic efficiency was determined from the ratio of ΔCm to integrated Ca2+ entry. To avoid problems with cell-to-cell variability, each cell was used as its own control. Values given represent the mean change in exocytotic efficiency ± SEM produced by a drug for the number of cells given by n. Shifts in exocytotic efficiency represent changes in the Ca2+ dependence of exocytosis caused either by a change in the affinity of the secretory machinery for Ca2+ or a change in the number of vesicles available for release in the RRP. Significant changes are indicated by

(p < 0.05). The potentiation of exocytosis produced by AngII (100 nm) was associated with a profound increase in exocytotic efficiency. Inhibition of exocytosis by lower concentrations of AngII, however, was not associated with a change in exocytotic efficiency.

Amperometric evidence for catecholamine secretion

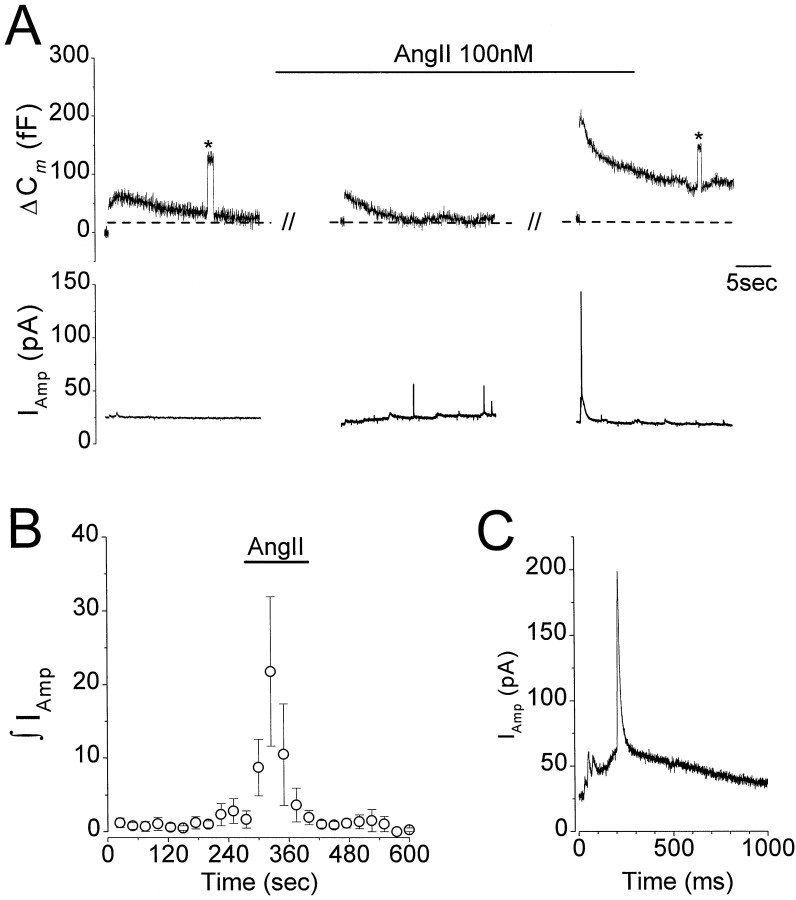

Previous studies have shown that AngII increases catecholamine release from populations of chromaffin cells (Bunn and Marley, 1989;O'Sullivan and Burgoyne, 1989), and it is likely that the ΔCm increases observed in this study result from fusion of catecholamine-containing vesicles. To confirm this and to obtain some indirect spatial information on the effects of AngII on stimulus-evoked exocytosis, we combinedCm measurements with single-cell amperometry. The carbon fiber electrodes that were used had tip diameters of ∼5 μm so that single vesicle release events of catecholamine were only detected when the fiber was in close proximity to a release site (Robinson et al., 1995). We had no means of determining where the release sites were and found empirically that the probability of obtaining synchronous amperometric spikes and depolarization-evoked ΔCm under control conditions was low. Thus for a 100 fFCm increase, the average integrated charge was 4.4 ± 3.2 pC (n = 3 cells, 10 depolarizations per cell). Increasing stimulus strength to evoke a ΔCm of 300–400 fF did not increase the number of events detected with amperometry, consistent with previous reports that secretion remains highly localized (Schroeder et al., 1994; Robinson et al., 1995). In the presence of AngII (100 nm), previously silent sites became active, with both asynchronous unitary events and synchronous release events being observed (Fig.3A,C). The mean amperometric charge recorded in the presence of AngII was 32 ± 17 pC, which represents a 1051 ± 565% increase over control (Fig. 3B). These results confirm that the potentiation of ΔCm observed after application of high concentrations of AngII are caused by increased exocytosis of catecholamine-containing vesicles and furthermore suggest that AngII increases the number of active release sites.

Fig. 3.

AngII increased catecholamine secretion detected by single-cell amperometry. A, Data shown are from a single cell showing simultaneous recording ofCm (top traces) and amperometric current (bottom traces) before and during superfusion of AngII (indicated by bar). Exocytosis was evoked at the start of each trace with a 60 msec voltage step to +20 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV (indicated by thegap in the Cm trace;asterisks indicate 100 fF calibration steps). In the absence of the agonist, the voltage stimulus elicited a ΔCm of 60 fF, but no amperometric spikes were detected. Thirty seconds into AngII application (middle trace), amperometric spikes that were not synchronized with stimulus-evoked ΔCm were observed. A subsequent voltage stimulus evoked a ΔCmpotentiated by 400% (top right) and corresponding large amperometric current response (below). B, Mean data from three experiments similar to those illustrated inA. Data plotted are mean ± SEM integrated amperometric charge recorded over 30 sec intervals for the duration of the experiment. AngII (100 nm) application is indicated by the bar. C, Amperometric response that was recorded in synchrony with the potentiated ΔCm during application of AngII. Note that several spikes can be distinguished. Data are from the same cell illustrated in A shown on an expanded time scale.

Ca2+ mobilization is required for AngII-dependent facilitation of exocytosis

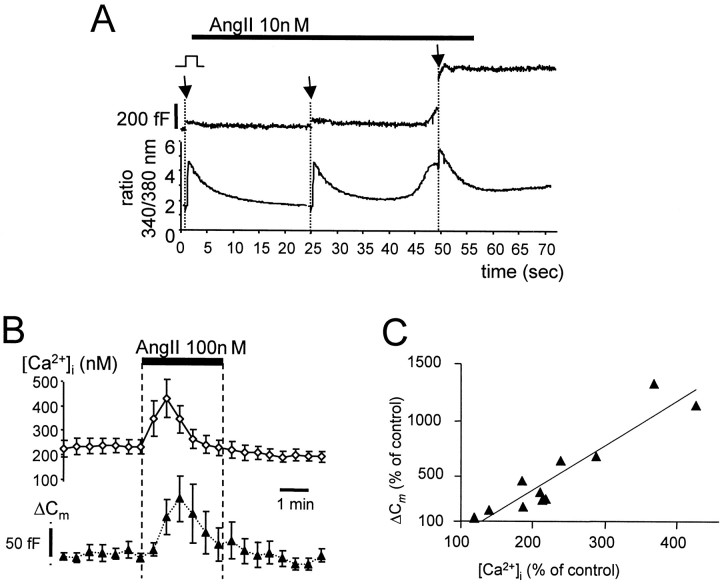

Previous studies have shown that AngII activates PLC, leading to formation of inositol phosphates and a rise in [Ca2+]i in bovine chromaffin cells (Plevin and Boarder, 1988; Bunn and Marley, 1989;O'Sullivan et al., 1989). To examine the relationship between AngII-induced Ca2+ signaling and stimulus-evoked exocytosis, we combined recording ofICa and ΔCm with fura-2 AM measurements of [Ca2+]i. Under control conditions, the mean basal [Ca2+]i in chromaffin cells held at −80 mV was 218 ± 22 nm (n = 11), which is comparable to that reported in other studies using constant, low-frequency voltage stimulation (Smith et al., 1998). AngII (100 nm) increased basal [Ca2+]i to 502 ± 66 nm (n = 11), corresponding to a mean increase of 235 ± 28%. The rise in [Ca2+]i peaked within 30–60 sec of AngII reaching the cell and subsequently declined despite the continued presence of agonist (Fig.4A,B). In all cells the rise in [Ca2+]i induced by 100 nm AngII was associated with a profound but transient facilitation of exocytosis (Fig.4A,B). We observed a strong correlation between the percentage increase in ΔCm and the percentage increase in [Ca2+]i relative to control (R2 = 0.87) (Fig.4C). In contrast, there was a poor correlation (R2 = 0.29) between the percentage increase in exocytosis and the peak [Ca2+]i recorded in the presence of AngII.

Fig. 4.

AngII potentiation of ΔCm was correlated to a rise in [Ca2+]i. A, Simultaneous recording of Cm(top) and [Ca2+]i(bottom) in a single chromaffin cell voltage-clamped to −80 mV. [Ca2+]i was measured with fura-2 AM. Values plotted are the ratios of emitted fluorescence at excitation wavelengths 340 and 380 nm. Cmand [Ca2+]i measurements were interrupted (indicated by arrows) to apply 40 msec voltage steps to +20 mV. Forty-five seconds into application of AngII (indicated by bar above the trace), a profound potentiation of ΔCm and corresponding rise in [Ca2+]i are observed. AngII increased basal [Ca2+]i from 219 to a maximum of 1060 nm. B, Time course of AngII potentiation of stimulus-evoked secretion. Cells were stimulated every 25 sec with voltage steps to +20 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV. Mean ± SEM changes in [Ca2+]i before and ΔCm after voltage steps are plotted against time (n = 8). Time of drug application is indicated by the horizontal bar and hatched lines. Note that the increase in [Ca2+]i preceded ΔCm potentiation. C, Pooled data from 11 cells showing the correlation between rise in [Ca2+]i (%of control) and potentiation of ΔCm (% of control) caused by AngII (100 nm). Solid line through the data was fit by linear regression (R2 = 0.87).

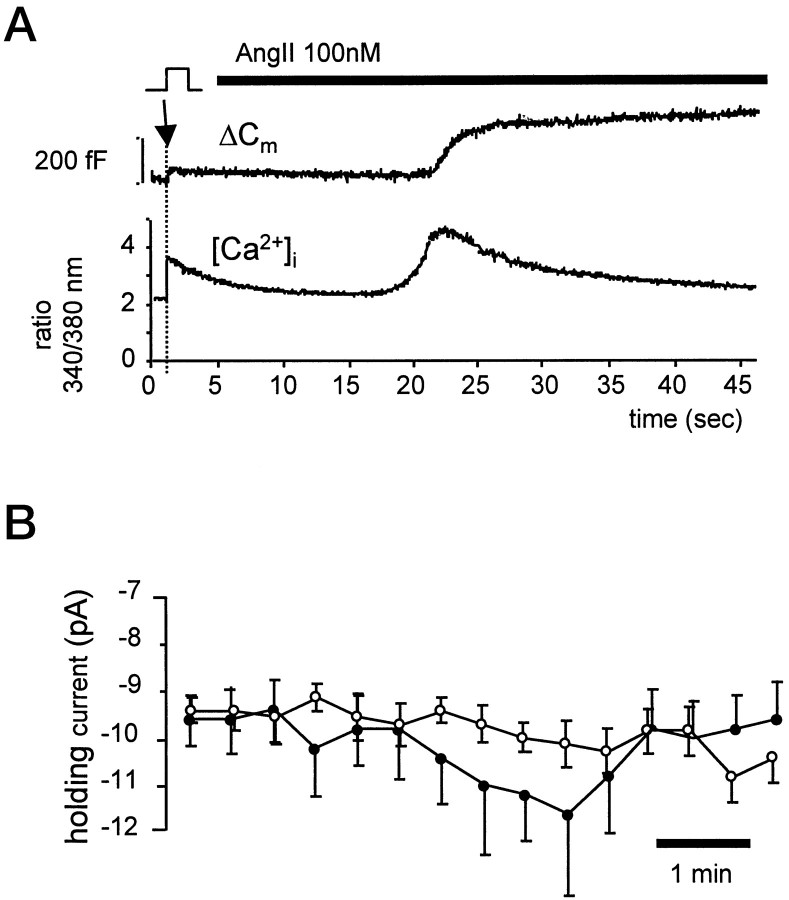

In addition to facilitation of stimulus-evoked exocytosis, in 52% of cells examined (n = 21), the rising phase of the [Ca2+]i increase produced by AngII was followed by a Cmincrease, in the absence of voltage stimulation (Fig.5A). Because this increase inCm occurred at the holding potential of −80 mV, we will refer to it as depolarization-independent exocytosis. In cells in which AngII induced depolarization-independent exocytosis, the potentiation of subsequent stimulus-evoked exocytosis was greatest (range 466–2681%; n = 7), indicating that depolarization-independent exocytosis does not deplete the cell of releasable vesicles. Depolarization-independent exocytosis was observed in cells in which (1) the [Ca2+]i rise reached significantly higher levels (608 ± 72 nm) than in other cells (398 ± 53 nm; unpaired t test), and (2) the average holding current increased in the presence of AngII from −8.5 to −10.5 pA (Fig. 5B). The small amplitude of this current is consistent with previously characterized store-operated Ca2+ entry currents that trigger voltage-independent exocytosis in chromaffin cells (Fomina and Nowycky, 1999). After removal of Ca2+ from the external solution for 1.5 min, the rise in [Ca2+]i produced by AngII (430 ± 119%, n = 6) or caffeine (50 mm; n = 9) at a concentration shown previously to deplete stores in chromaffin cells (Cheek et al., 1993b) failed to trigger depolarization-independent exocytosis. This is in agreement with previous studies that also found that external Ca2+ was necessary for AngII-induced catecholamine release (Bunn and Marley, 1989; O'Sullivan and Burgoyne, 1989; Cheek et al., 1993a). Collectively, the results suggest that agonist-stimulated Ca2+ entry across the plasma membrane in addition to Ca2+release from internal stores is required to trigger vesicle fusion in the absence of membrane depolarization.

Fig. 5.

AngII-induced voltage-independent exocytosis is associated with an increased leak current. A shows an example of a chromaffin cell clamped to −80 mV in which AngII (100 nm) produced a spontaneous increaseCm (top trace) 20 sec after agonist application. For comparison, ΔCmevoked by a voltage step is shown at the start of the trace (indicated by arrow). Changes in [Ca2+]i recorded in the same cell are shown below. AngII-induced voltage-independent exocytosis followed an increase in [Ca2+]i from 296 to 1064 nm. B, Diary plots of the mean ± SEM holding current recorded in the presence of AngII (100 nm).Filled circles show data from 11 cells in which voltage-independent exocytosis was observed. Open circles show data from 10 cells in which AngII failed to stimulate voltage-independent exocytosis. Comparison of the change in holding current of cells exhibiting voltage-independent exocytosis in the presence of AngII with those that did not is highly significant (unpaired Student's t test, p < 0.05).

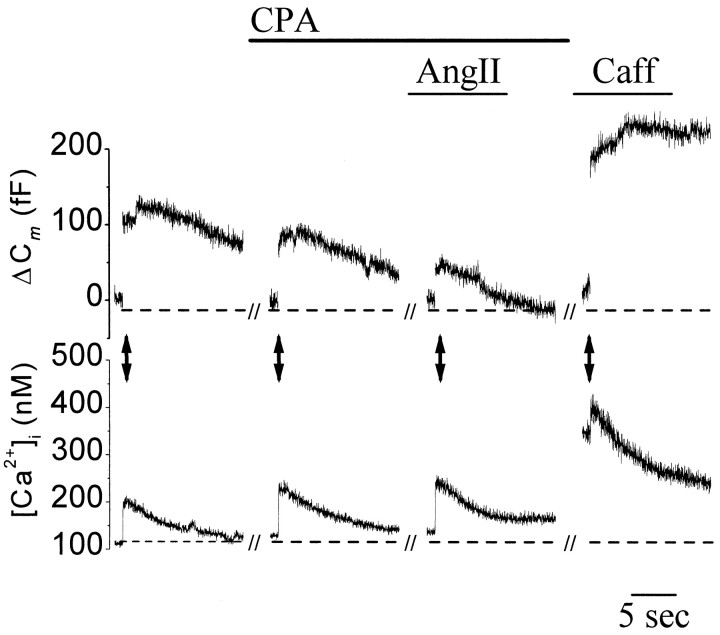

To determine the role of Ca2+ released from internal stores in facilitation of exocytosis, cells were treated with CPA (3 μm), a blocker of neuronal endoplasmic Ca2+-ATPases (Sandler and Barbara, 1999). Before application of AngII, depletion of the stores was ensured and tested with two to three applications of caffeine (50 mm, 1.5 min). Depletion of internal stores abolished the AngII-induced rise in basal [Ca2+]i(122 ± 3% control) and reduced the facilitation of stimulus-evoked exocytosis (174 ± 17% of control;n = 3) (Fig. 6, Table 1). After washout of CPA and store refilling, reapplication of caffeine increased basal [Ca2+]i to 232 ± 12% of control and potentiated stimulus-evoked ΔCm to 226 ± 93% of control (n = 3) (Fig. 6). An equivalent rise in basal [Ca2+]i induced by AngII facilitated ΔCm by ∼500% (Fig. 4C), suggesting that increased [Ca2+]i was not the only mechanism responsible for facilitation of exocytosis after activation of AngII receptors.

Fig. 6.

Ca2+ release from internal stores is required for AngII-dependent facilitation of exocytosis. Traces represent simultaneous measurements of Cm (top) and [Ca2+]i (bottom) recorded in a single cell voltage-clamped to −80 mV. Increases in [Ca2+]i and exocytosis were evoked every 25 sec with voltage steps to +20 mV (indicated bydouble-headed arrows). Data shown are on an expanded time scale and show the first 10 sec of recording after each voltage step. Drugs present during the voltage step are indicated above eachtrace. Continuous application of CPA for 18 min attenuated AngII (100 nm)-dependent increases in [Ca2+]i and stimulus-evoked ΔCm. Before AngII, store depletion was tested at 5 min intervals by application of caffeine (50 mm, 1.5 min; data not shown). On the far right can be seen that after washout of CPA for 3 min, stores refilled, and a subsequent application of caffeine (50 mm) elicited a rise in [Ca2+]i.

In addition to generating inositol phosphates, activation of PLC by AngII generates the second messenger sn-1,2-diacylglycerol (Tuominen et al., 1993). The role of PLC in mediating the effects of AngII (100 nm) on stimulus-secretion coupling was examined by treating cells for 7 min with either the PLC inhibitor U-73122 (1 μm) or its inactive isomer U-73443 (1 μm). In the presence of the active isomer, both the AngII-induced rise in basal [Ca2+]i and facilitation of stimulus-evoked exocytosis were significantly decreased to 154 ± 44 and 79 ± 18% of control (n = 5), respectively. By contrast, U-73443 had no significant effects on AngII-induced increases in basal [Ca2+]i (282 ± 92%) or on stimulus-evoked exocytosis (627 ± 263%;n = 3) (Table 1). These studies support the need for generation of a Ca2+-mobilizing second messenger and activation of PLC in agonist-induced facilitation of exocytosis.

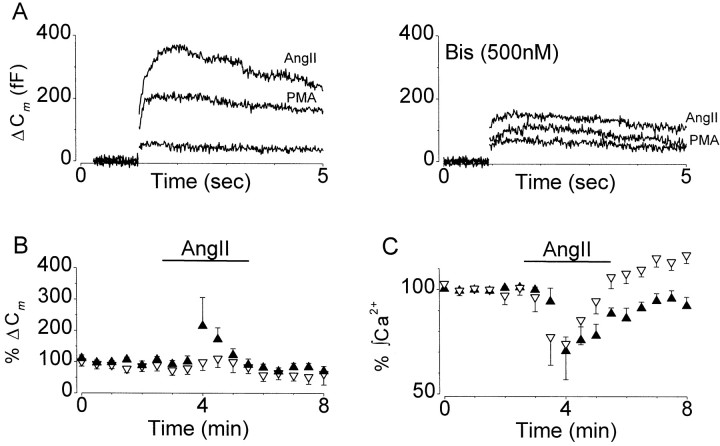

Role of PKC in AngII-dependent facilitation of stimulus-evoked exocytosis

AngII-stimulated sn-1,2-diacylglycerol production may facilitate exocytosis through activation of PKC and/or Doc2α–Munc13 interactions (Terbush et al., 1988; Hori et al., 1999). The role of PKC in mediating the effects of AngII on stimulus-evoked exocytosis was examined by treating cells with either Calphostin C (100 nm for 7 min) or BIS (500 nm >20 min) before application of AngII. These two inhibitors were selected because of their different modes of action. Calphostin C inhibits PKC and possibly other recently identified signaling molecules by competing with diacylglycerol for the regulatory C1 binding site (Mellor and Parker, 1998). BIS, on the other hand, at nanomolar concentrations acts as a highly selective competitive inhibitor for the ATP-binding site of PKC (Toullec et al., 1991). We observed that BIS reduced the potentiation of ΔCm by AngII from 524 ± 118% (n = 11) to 215 ± 90% (n = 7) (Fig.7A,B, Table 1), suggesting that PKC is involved in agonist-dependent facilitation of exocytosis. Consistent with this, Calphostin C was found to abolish the AngII-induced potentiation of stimulus-evoked exocytosis (104 ± 36% of control; n = 7) (Fig.7B, Table 1). In contrast to BIS, Calphostin C also attenuated the AngII-induced rise in [Ca2+]i (118 ± 17%). We do not believe that the effects of Calphostin C on [Ca2+]i were attributable simply to toxicity, because neither Calphostin C nor BIS blocked the AngII inhibition of ICa(Fig. 7C). Instead, Calphostin C may be depleting stores through an inhibitory effect on diacylglycerol-regulated Ca2+ entry pathways (Hofmann et al., 1999).

Fig. 7.

PKC is partially responsible for AngII-dependent facilitation of exocytosis. A, Left, Superimposed traces are from a single cell and show the effect of PMA (50 nm) and AngII (100 nm) on voltage-evoked ΔCm. Right, Data from another cell, in which the PKC inhibitor BIS was applied for 20 min before addition of PMA (50 nm) and AngII (100 nm). B, Diary plots showing the effect of AngII (100 nm) on voltage-evoked ΔCm recorded in cells treated with BIS for 20 min (filled triangles; n = 5) or Calphostin C (open triangles;n = 7). Data plotted are the mean ± SEM.C, Diary plots showing the effect of AngII on voltage-dependent Ca2+ entry in the same sets of cells as shown in B. Treatment with the PKC inhibitors did not affect AngII inhibition of VOCCs but significantly attenuated the facilitation of stimulus-evoked exocytosis.

For comparison, in some experiments we used PMA (50 nm) to directly activate diacylglycerol-regulated proteins. In agreement with previous reports, PMA facilitated exocytosis to 442 ± 100% of control (n = 5) but, in contrast to AngII, without significantly affecting ICa (94 ± 3% control) (Fig. 7A, Table 1). The facilitatory effects of PMA on ΔCm were abolished by Calphostin C (n = 5) and reduced by BIS to 228 ± 46% of control (n = 5) (Fig. 7A). Collectively, the results from these experiments suggest that AngII facilitates depolarization-evoked exocytosis through activation of PLC, raising [Ca2+]iand activation of PKC.

AT1Rs couple to multiple G-proteins to produce bimodal regulation of exocytosis

Results from both binding and cloning experiments suggest that bovine chromaffin cells express only a single type of AngII receptor with the pharmacological properties of an AT1R (Marley et al., 1989). In heterologous expression systems, AT1Rs have been found to couple to multiple G-proteins (Shibata et al., 1996). Thus in our final set of experiments we wished to determine whether AT1R activation of multiple G-proteins could produce bimodal regulation of exocytosis. Consistent with this hypothesis, we observed that all of the effects of AngII on stimulus-secretion coupling were blocked by the AT1R antagonist losartan (Fig.8C–F). Furthermore, uncoupling of receptors from Gi/o-proteins with PTX abolished the inhibitory effects of AngII on ICa and exocytosis but not the facilitatory effects (Fig. 8). In PTX-treated cells, the concentration–response curve for AngII modulation of exocytosis became unimodal, and thus the EC50 for facilitation could be determined and was found to be 3.4 nm(compare Figs. 2D and 8B). Moreover, the maximum facilitation of stimulus-evoked ΔCm observed with 100 nm AngII was increased to 785 ± 246% (n = 7) compared with the 524 ± 118% potentiation observed in untreated cells. These results suggest that AT1Rs in chromaffin cells are coupled via distinct G-proteins to multiple signal transduction cascades to produce opposing effects onICa, cytosolic [Ca2+], and exocytosis.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show that activation of multiple G-proteins and transduction pathways by a single neuromodulator acting through one receptor type can produce concentration-dependent, bidirectional regulation of exocytosis. Metabotropic glutamate receptors have also been shown to switch between facilitation and inhibition of synaptic transmission; however, in this case coupling of the receptor to Gi/o- and Gq-proteins is regulated by desensitization (Rodriguez-Moreno et al., 1998). This does not appear to be the mechanism underlying AngII bimodal regulation of secretion, because the inhibitory effects of the Gi/o-protein-coupled receptor on VOCCs and the facilitatory effects on exocytosis mediated by the Gq-protein-coupled receptor could be seen simultaneously with high concentrations of agonist. Thus it would appear that coupling of a single type of receptor to different signal transduction pathways not only serves to coordinate short-term and long-term changes in neuronal function, but may also allow neurons to adapt their secretory output in response to fluctuating levels of agonist.

Transduction pathway mediating AT1R inhibition of depolarization-dependent exocytosis

Inhibition of transmitter release by other G-protein-coupled receptors is generally thought to involve either changes in membrane excitability and Ca2+ signaling or a direct effect on some component of the release machinery (Hille, 1994;Wu and Saggau, 1997; Miller, 1998). In this study we showed that low concentrations of AngII induced a parallel inhibition ofICa and exocytosis. The inhibition ofICa displayed the characteristic voltage sensitivity commonly associated with GPCR inhibition of neuronal VOCCs by a membrane-delimited pathway involving Gβγ-subunits (Dolphin, 1998). PTX abolished the inhibition ofICa and exocytosis by AngII without affecting AT1R coupling to PLC, Ca2+mobilization, and facilitation of exocytosis. Inhibition of PKC, on the other hand, did not prevent AngII modulation ofICa. Taken together, the results suggest that Gβγ-subunits from Gi/o-coupled AT1Rs inhibit ICa in chromaffin cells, but Gβγ-subunits associated with Ca2+-mobilizing AT1Rs do not. Our results are consistent with the observation that βγ-subunits associated with non-PTX-sensitive G-proteins have a low affinity for VOCCs (Garcia et al., 1998). Further restraints on the transduction pathway involved in inhibition of stimulus-evoked exocytosis may result from compartmentalization of the Gi/o- and Gq/11-coupled AT1Rs to different poles of the cell, with only the former being in a position to regulate VOCCs through the membrane-delimited pathway. GPCRs and voltage-dependent evoked rises in [Ca2+]i have indeed been shown to occur in discreet areas of the cell (Robinson et al., 1996).

There are two Ca2+-sensitive processes that contribute to exocytosis and could therefore be affected by inhibition of ICa: a high-affinity step that regulates the number of vesicles in the RRP and a low-affinity step that controls vesicle fusion (Neher, 1998). The size of the RRP is directly correlated to [Ca2+]i (Heinemann et al., 1993), whereas depolarization-evoked vesicle fusion is determined by the integrated Ca2+ entry through VOCCs (Engisch and Nowycky, 1996; Seward and Nowycky, 1996). At low concentrations, AngII decreased Ca2+entry through VOCCs and exocytosis without significantly affecting the resting [Ca2+]i. Therefore, inhibition of vesicle fusion rather than the filling state of the RRP is the most likely mechanism underlying inhibition of secretion. The fusion machinery itself appeared unaffected by activated Gi/o-proteins because exocytotic efficiency was unaffected by low concentrations of AngII. This is consistent with our previous studies in chromaffin cells on another Gi/o-protein-coupled receptor and with studies on a central glutamatergic synapse and support the hypothesis that depression of exocytosis observed after activation of PTX-sensitive G-proteins is fully accounted for by inhibition of Ca2+ influx through VOCCs (Takahashi et al., 1996; Powell et al., 2000).

Mechanism of exocytotic facilitation by AngII

At concentrations of 10 nm or higher, the inhibitory effect of AngII on secretion was overcome, and exocytosis was facilitated. Potentiation of secretion involved activation of PLC, Ca2+ mobilization, and PKC and was independent of the inhibitory pathway. It is well known that GPCR-regulated PLC-β(1–4) isoenzymes may be activated by α-subunits of Gq-proteins or with less potency by Gβγ-subunits of numerous G-proteins, including Gi/o (Morris and Scarlata, 1997). The transduction pathway involved in facilitation of exocytosis did not involve the Gi/o-coupled AT1R because PTX had no significant effects on AngII-induced Ca2+mobilization, nor did it attenuate potentiation of exocytosis. Therefore, the AngII receptors mediating facilitation likely correspond to the Gq-protein-coupled AT1Rs described previously (Plevin and Boarder, 1988).

The mechanism underlying agonist-dependent facilitation of exocytosis was found to be dependent on a rise in [Ca2+]i. Results from this and other studies showed that the rise in [Ca2+]i was attributable to release from intracellular stores and influx across the plasma membrane (Cheek et al., 1993a). Elevated [Ca2+]i has been shown to enhance ΔCm by increasing the RRP (von Ruden and Neher, 1993; Smith et al., 1998). Interestingly, in this study we found that caffeine-induced rises in [Ca2+]i were not as effective as AngII in potentiating stimulus-evoked exocytosis. The discrepancy may arise from differences in the location of the two Ca2+ signals with regard to the secretory apparatus because the agonist would preferentially activate IP3-sensitive stores whereas caffeine activates ryanodine-sensitive stores (Berridge, 1998). Chromaffin cells, like neurons, are known to possess independent IP3-sensitive and caffeine-sensitive stores that are localized to different compartments of the cell (Cheek et al., 1991, 1993a,b; Koizumi et al., 1999).

Activation of PLC by AT1R will also lead to production of diacylglycerol, which regulates at least two families of proteins known to modulate exocytosis directly, namely PKC and Munc-13 (Hori et al., 1999), as well as noncapacitative Ca2+entry pathways (Hofmann et al., 1999). Evidence in support of a role for PKC in AngII facilitation of stimulus-evoked exocytosis was shown by the use of two different inhibitors. The PKC-dependent facilitation of exocytosis appeared to require a rise in Ca2+ because it was not observed in CPA-treated cells. This is consistent with the known properties of conventional PKC isoforms, which require both diacylglycerol and Ca2+ for activation (Newton and Johnson, 1998). Note, however, that at concentrations of BIS that are reported to be selective for PKC, AngII-induced facilitation was not abolished, indicating that Ca2+-dependent proteins other than PKC are also involved. Activity-dependent potentiation of secretion is also reported to be mediated by Ca2+ and PKC and to be quantitatively comparable to the potentiation observed with PMA (Smith et al., 1998). We found that PMA was less effective than AngII in facilitating exocytosis, suggesting that different or additional effectors are involved in agonist- versus activity-dependent facilitation.

We can conclude from these studies that activation of Ca2+-mobilizing AT1Rs will facilitate exocytosis through both Ca2+- and PKC-dependent mechanisms. At present the molecular targets in the secretory pathway that are subject to modulation are unknown. However, considering what is known about compartmentalization of signaling molecules and the processes underlying stimulus-evoked exocytosis, several possibilities arise. Ca2+ released from IP3-sensitive stores may act locally to produce actin disassembly through activation of Ca2+-sensitive actin-severing proteins and thereby promote vesicle recruitment from the reserve pool to the RRP (Zhang et al., 1995). Additionally, store-released Ca2+ may diffuse toward the plasma membrane and sum with incoming Ca2+ to promote exocytosis. Activation of Ca2+entry at the plasma membrane may trigger fusion of vesicles docked close to the receptor-operated calcium channels or promote vesicle priming through effects on Ca2+-binding proteins such as DOC2, Rabphilin, or CAPS (Benfenati et al., 1999;Elhamdani et al., 1999). Additionally, generation of diacylglycerol at the plasma membrane may increase vesicle docking and priming by activation of PKC and (1) phosphorylation of cytoskeletal proteins controlling vesicle recruitment to the RRP (Vitale et al., 1995) and/or (2) phosphorylation of proteins that regulate SNARE complex formation (Turner et al., 1999). Diacylglycerol may also activate Munc-13 directly to regulate SNARE complex formation (Hori et al., 1999). Interestingly, a pathway facilitating exocytosis composed of Gq, PLC-β, and UNC-13 has recently been described in Caenorhabditis elegans (Lackner et al., 1999). Molecular studies coupled with high-resolution imaging will be needed to discern which of these mechanisms is involved in AngII-dependent facilitation and whether the same signaling cascades are activated by other Ca2+-mobilizing GPCRs.

Physiological significance and implications of bimodal regulation of secretion

AngII is produced both in the blood and, independently, in the adrenal (Bottari et al., 1993). Subnanomolar levels of circulating AngII are reached in certain physiological states such as dehydration (Belles et al., 1988). Our results suggest that they could act to inhibit catecholamine secretion as part of a regulatory feedback loop. The concentrations of AngII required to increase catecholamine release (EC50 3.4 nm) are less likely to be reached in plasma under steady-state physiological conditions but would be generated locally in the adrenal and contribute to clinical conditions such as hypertension (Francis, 1988) or responses to severe hemorrhage (Gupta et al., 1995; Ponchon and Elghozi, 1997).

Coupling of AT1Rs to multiple G-proteins has been reported previously (Richards et al., 1999) and is relatively common among GPCRs (Gudermann et al., 1996). Earlier studies have identified and characterized the selectivity of receptor G-protein–effector coupling or the diversity of effectors regulated by a single receptor subtype (Hille, 1994;Delmas et al., 1998). AT1R activation of multiple transduction pathways is known to be necessary for coordination of short-term and long-term changes in neuronal function (Richards et al., 1999). In this study we have shown that one function of AT1R coupling to diverse G-proteins is to produce bimodal regulation of exocytosis, thereby allowing a chromaffin cell to adapt rapidly its secretory output to fluctuating levels of AngII. A similarly complex regulation of hormone release by AngII has been reported in anterior pituitary cells (Enjalbert et al., 1986; Crawford et al., 1992) and adrenal glomerulosa cells (Kojima et al., 1986). Thus the potential for bimodal regulation of secretion may be a general feature of AT1Rs and possibly other members of the GPCR superfamily.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the Wellcome Trust. We gratefully acknowledge the help of Prof. R. H. Chow and Dr. A. Schulte in setting up the amperometry experiments and Dr. S. Kasparov for analysis software, as well as Drs. M. Nowycky, G. Henderson, A. D. Powell, and J. M. Trifaro for helpful discussion of this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Elizabeth P. Seward, Department of Pharmacology, University Walk, Bristol BS3 1TD, U.K. E-mail:Liz.Seward@bristol.ac.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bacal K, Kunze DL. Dual effects of angiotensin II on calcium currents in neonatal rat nodose neurons. J Neurosci. 1994;14:7159–7167. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-07159.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belles B, Hescheler J, Trautwein W. A possible physiological role of the Ca-dependent protease calpain and its inhibitor calpastatin on the Ca current in guinea pig myocytes. Pflügers Arch. 1988;412:554–556. doi: 10.1007/BF00582548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benfenati F, Onofri F, Giovedi S. Protein-protein interactions and protein modules in the control of neurotransmitter release. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999;354:243–257. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berridge MJ. Neuronal calcium signaling. Neuron. 1998;21:13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80510-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bottari SP, De Gasparo M, Steckelings UM, Levens NR. Angiotensin II receptor subtypes: characterization, signalling mechanisms, and possible physiological implications. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1993;14:123–171. doi: 10.1006/frne.1993.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bunn SJ, Marley PD. Effects of angiotensin II on cultured, bovine adrenal medullary cells. Neuropeptides. 1989;13:121–132. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(89)90009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheek TR, Barry VA, Berridge MJ, Missiaen L. Bovine adrenal chromaffin cells contain an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-insensitive but caffeine-sensitive Ca2+ store that can be regulated by intraluminal free Ca2+. Biochem J. 1991;275:697–701. doi: 10.1042/bj2750697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheek TR, Morgan A, O'Sullivan AJ, Moreton RB, Berridge MJ, Burgoyne RD. Spatial localization of agonist-induced Ca2+ entry in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells: different patterns induced by histamine and angiotensin II, and relationship to catecholamine release. J Cell Sci. 1993a;105:913–921. doi: 10.1242/jcs.105.4.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheek TR, Moreton RB, Berridge MJ, Stauderman KA, Murawsky MM, Bootman MD. Quantal Ca2+ release from caffeine-sensitive stores in adrenal chromaffin cells. J Biol Chem. 1993b;268:27076–27083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawford KW, Frey EA, Cote TE. Angiotensin II receptor recognized by DuP753 regulates two distinct guanine nucleotide-binding protein signaling pathways. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:154–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delmas P, Abogadie FC, Dayrell M, Haley JE, Milligan G, Caulfield MP, Brown DA, Buckley NJ. G-proteins and G-protein subunits mediating cholinergic inhibition of N-type calcium currents in sympathetic neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:1654–1666. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dolphin AC. Mechanisms of modulation of voltage-dependent calcium channels by G proteins. J Physiol (Lond) 1998;506:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.003bx.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elhamdani A, Martin TF, Kowalchyk JA, Artalejo CR. Ca2+-dependent activator protein for secretion is critical for the fusion of dense-core vesicles with the membrane in calf adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7375–7383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07375.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engisch KL, Nowycky MC. Calcium dependence of large dense-cored vesicle exocytosis evoked by calcium influx in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1359–1369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01359.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engisch KL, Chernevskaya NI, Nowycky MC. Short-term changes in the Ca2+-exocytosis relationship during repetitive pulse protocols in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9010–9025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09010.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enjalbert A, Sladeczek F, Guillon G, Bertrand P, Shu C, Epelbaum J, Garcia-Sainz A, Jard S, Lombard C, Kordon C. Angiotensin II and dopamine modulate both cAMP and inositol phosphate productions in anterior pituitary cells. Involvement in prolactin secretion. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:4071–4075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldberg W, Lewis GP. The action of peptides on the adrenal medulla. Release of adrenaline by bradykinin and angiotensin. J Physiol (Lond) 1964;171:98–108. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fomina AF, Nowycky MC. A current activated on depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores can regulate exocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3711–3722. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03711.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Francis GS. Modulation of peripheral sympathetic nerve transmission. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;12:250–254. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia DE, Li B, Garcia-Ferreiro RE, Hernandez-Ochoa EO, Yan K, Gautam N, Catterall WA, Mackie K, Hille B. G-protein beta-subunit specificity in the fast membrane-delimited inhibition of Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9163–9170. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-22-09163.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gudermann T, Kalkbrenner F, Schultz G. Diversity and selectivity of receptor-G protein interaction. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;36:429–459. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.002241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta P, Franco-Saenz R, Mulrow PJ. Locally generated angiotensin II in the adrenal gland regulates basal, corticotropin-, and potassium-stimulated aldosterone secretion. Hypertension. 1995;25:443–448. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.3.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heinemann C, von Ruden L, Chow RH, Neher E. A two-step model of secretion control in neuroendocrine cells. Pflügers Arch. 1993;424:105–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00374600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hille B. Modulation of ion-channel by G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:531–536. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofmann T, Obukhov AG, Schaefer M, Harteneck C, Gudermann T, Schultz G. Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature. 1999;397:259–263. doi: 10.1038/16711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hori T, Takai Y, Takahashi T. Presynaptic mechanism for phorbol ester-induced synaptic potentiation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7262–7267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07262.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horrigan FT, Bookman RJ. Releasable pools and the kinetics of exocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells. Neuron. 1994;13:1119–1129. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunyady L, Balla T, Catt KJ. The ligand binding site of the angiotensin AT1 receptor. Trends Pharmacol. 1996;17:135–140. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(96)81588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koizumi S, Bootman MD, Bobanovic LK, Schell MJ, Berridge MJ, Lipp P. Characterization of elementary Ca2+ release signals in NGF-differentiated PC12 cells and hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1999;22:125–137. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80684-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kojima I, Shibata H, Ogata E. Pertussis toxin blocks angiotensin II-induced calcium influx but not inositol trisphosphate production in adrenal glomerulosa cell. FEBS Lett. 1986;204:347–351. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lackner MR, Nurrish SJ, Kaplan JM. Facilitation of synaptic transmission by EGL-30 Gqalpha and EGL-8 PLCbeta: DAG binding to UNC-13 is required to stimulate acetylcholine release. Neuron. 1999;24:335–346. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80848-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marley PD, Bunn SJ, Wan DCC, Allen AM, Mendelsohn FAO. Localization of angiotensin II binding sites in the bovine adrenal medulla using a labelled specific antagonist. Neuroscience. 1989;28:777–787. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mellor H, Parker PJ. The extended protein kinase C superfamily. Biochem J. 1998;332:281–292. doi: 10.1042/bj3320281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller RJ. Presynaptic receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1998;38:201–227. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris AJ, Scarlata S. Regulation of effectors by G-protein alpha- and betagamma-subunits: recent insights from studies of the phospholipase C-beta isoenzymes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;54:429–435. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neher E. Vesicle pools and Ca2+ microdomains: new tools for understanding their roles in neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;20:389–399. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80983-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newton AC, Johnson JE. Protein kinase C: a paradigm for regulation of protein function by two membrane-targeting modules. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1376:155–172. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(98)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Sullivan AJ, Burgoyne RD. A comparison of bradykinin, Angiotensin II and muscarinic stimulation of cultured bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Biosci Rep. 1989;9:243–252. doi: 10.1007/BF01116001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Sullivan AJ, Cheek TR, Moreton RB, Berridge MJ, Burgoyne RD. Localization and heterogeneity of agonist-induced changes in cytosolic calcium concentration in single bovine adrenal chromaffin cells from video imaging of fura-2. EMBO J. 1989;8:401–411. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oppermann M, Freedman NJ, Alexander RW, Lefkowitz RJ. Phosphorylation of the type 1A angiotensin II receptor by G protein-coupled receptor kinases and protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13266–13272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.13266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plevin R, Boarder MR. Stimulation of formation of inositol phosphates in primary cultures of bovine adrenal chromaffin cells by angiotensin II, histamine, bradykinin, and carbachol. J Neurochem. 1988;51:634–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ponchon P, Elghozi JL. Contribution of humoral systems to the recovery of blood pressure following severe haemorrhage. J Auton Pharmacol. 1997;17:319–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2680.1997.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Powell AD, Teschemacher AG, Seward EP. P2Y purinoceptors inhibit exocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells via modulation of voltage-operated calcium channels. J Neurosci. 2000;20:606–616. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00606.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richards EM, Raizada MK, Gelband CH, Sumners C. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor-modulated signaling pathways in neurons. Mol Neurobiol. 1999;19:25–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02741376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson IM, Finnegan JM, Monck JR, Wightman RM, Fernandez JM. Colocalization of calcium entry and exocytotic release sites in adrenal chromaffin cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2474–2478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robinson IM, Yamada M, Carrion-Vazquez M, Lennon VA, Fernandez JM. Specialized release zones in chromaffin cells examined with pulsed-laser imaging. Cell Calcium. 1996;20:181–201. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(96)90106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodriguez-Moreno A, Sistiaga A, Lerma J, Sanchez-Prieto J. Switch from facilitation to inhibition of excitatory synaptic transmission by group 1 mGluR desensitisation. Neuron. 1998;21:1477–1486. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80665-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sandler VM, Barbara JG. Calcium-induced calcium release contributes to action potential-evoked calcium transients in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4325–4336. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04325.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schroeder TJ, Jankowski JA, Senyshyn J, Holz RW, Wightman RM. Zones of exocytotic release on bovine adrenal medullary cells in culture. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17215–17220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schulte A, Chow RH. Cylindrically etched carbon-fiber microelectrodes for low-noise amperometric recording of cellular secretion. Anal Chem. 1998;70:985–990. doi: 10.1021/ac970934e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seward EP, Nowycky MC. Kinetics of stimulus-coupled secretion in dialyzed bovine chromaffin cells in response to trains of depolarizing pulses. J Neurosci. 1996;16:553–562. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00553.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seward EP, Chernevskaya NI, Nowycky MC. Exocytosis in peptidergic nerve terminals exhibits two calcium-sensitive phases during pulsatile calcium entry. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3390–3399. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03390.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seward EP, Chernevskaya NI, Nowycky MC. Ba2+ ions evoke two kinetically distinct patterns of exocytosis in chromaffin cells, but not neurohypophysial nerve terminals. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1370–1379. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01370.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shapiro MS, Wollmuth LP, Hille B. Angiotensin II inhibits calcium and M current channels in rat sympathetic neurons via G proteins. Neuron. 1994;12:1319–1329. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shibata T, Suzuki C, Ohnishi J, Murakami K, Miyazaki H. Identification of regions in the human angiotensin II receptor type 1 responsible for Gi and Gq coupling by mutagenesis study. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;218:383–389. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith C, Moser T, Xu T, Neher E. Cytosolic Ca2+ acts by two separate pathways to modulate the supply of release-competent vesicles in chromaffin cells. Neuron. 1998;20:1243–1253. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80504-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takahashi T, Forsythe ID, Tsujimoto T, Barnes-Davies M, Onodera K. Presynaptic calcium current modulation by a metabotropic glutamate receptor. Science. 1996;274:594–597. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Terbush DR, Bittner MA, Holz RW. Ca2+ influx causes rapid translocation of protein kinase C to membranes: studies of the effects of secretagogues in adrenal chromaffin cells. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:18873–18879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Teschemacher AG, Henderson G, Seward EP. Angiotensin II modulates exocytosis in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells via multiple types of G-proteins. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1998;24:327.15. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toullec D, Pianetti P, Coste H, Bellevergue P, Grand-Perret T, Ajakane M, Baudet V, Boissin P, Boursier E, Loriolle F. The bisindolylmaleimide GF 109203X is a potent and selective inhibitor of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15771–15781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tuominen RK, Werner MH, Ye H, McMillian MK, Hudson PM, Hannun YA, Hong JS. Biphasic generation of diacylglycerol by angiotensin and phorbol ester in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;190:181–185. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Turner KM, Burgoyne RD, Morgan A. Protein phosphorylation and the regulation of synaptic membrane traffic. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:459–464. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01436-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vitale ML, Seward EP, Trifaro JM. Chromaffin cell cortical actin network dynamics control the size of the release-ready vesicle pool and the initial rate of exocytosis. Neuron. 1995;14:353–363. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.von Ruden L, Neher E. A Ca-dependent early step in the release of catecholamines from adrenal chromaffin cells. Science. 1993;262:1061–1065. doi: 10.1126/science.8235626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang JM, Llona I, De Potter WP. Receptor-mediated internalization of angiotensin II in bovine adrenal medullary chromaffin cells in primary culture. Regul Pept. 1994;53:77–86. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(94)90161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu LG, Saggau P. Presynaptic inhibition of elicited neurotransmitter release. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:204–212. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang L, Del Castillo AR, Trifaro JM. Histamine-evoked chromaffin cell scinderin redistribution, F-actin disassembly, and secretion: in the absence of cortical F- actin disassembly, an increase in intracellular Ca2+ fails to trigger exocytosis. J Neurochem. 1995;65:1297–1308. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65031297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]