Abstract

Structural diversity of voltage-gated Ca channels underlies much of the functional diversity in Ca signaling in neurons. Alternative splicing is an important mechanism for generating structural variants within a single gene family. In this paper, we show the expression pattern of an alternatively spliced 21 amino acid encoding exon in the II–III cytoplasmic loop region of the N-type Ca channel α1B subunit and assess its functional impact. Exon-containing α1B mRNA dominated in sympathetic ganglia and was present in ∼50% of α1B mRNA in spinal cord and caudal regions of the brain and in the minority of α1B mRNA in neocortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum (<20%). The II–III loop exon affected voltage-dependent inactivation of the N-type Ca channel. Steady-state inactivation curves were shifted to more depolarized potentials without affects on either the rate or voltage dependence of channel opening. Differences in voltage-dependent inactivation between α1Bsplice variants were most clearly manifested in the presence of Ca channel β1b or β4, rather than β2a or β3, subunits. Our results suggest that exon-lacking α1B splice variants that associate with β1b and β4 subunits will be susceptible to voltage-dependent inactivation at voltages in the range of neuronal resting membrane potentials (−60 to −80 mV). In contrast, α1B splice variants that associate with either β2a or β3 subunits will be relatively resistant to inactivation at these voltages. The potential to mix and match multiple α1B splice variants and β subunits probably represents a mechanism for controlling the plasticity of excitation–secretion coupling at different synapses.

Keywords: N-type calcium channel, α1 subunit, regulated alternative splicing, intracellular loop II–III, genomic analysis, tissue distribution, β subunit

Structural diversity of voltage-gated Ca channels is at the heart of the rich functional diversity in Ca signaling in mammalian neurons. Neurons can select from several distinct Ca channel α1 genes that undergo extensive RNA processing, including alternative splicing (Perez-Reyes et al., 1990; Soldatov, 1994; Kollmar et al., 1997;Lin et al., 1997; Bourinet et al., 1999) and differential polyadenylation (Schorge et al., 1999). Each α1subunit may also interact with multiple functionally distinct auxiliary subunits (Scott et al., 1996; Walker and De Waard, 1998), expanding the capacity for diversity within each Ca channel family. The α1B subunit is the functional core of N-type Ca channels that localize to synapses and control calcium-dependent neurotransmitter release throughout the vertebrate nervous system (Hirning et al., 1988; Takahashi and Momiyama, 1993; Dunlap et al., 1995). Many neurotransmitters and neurohormones modulate excitation–secretion coupling by regulating the gating of N-type Ca channels via effects on the α1B subunit (Dunlap et al., 1995). The α1B gene is also subject to tissue-specific alternative splicing (Lin et al., 1997, 1999), which probably represents an important mechanism for optimizing neurotransmitter release in different regions of the nervous system. The extent of splicing in the α1B gene is not known, but its large size (>100 kb in human genome), together with mismatches in α1B cDNAs isolated from different tissues, supports the presence of multiple sites of alternative splicing.

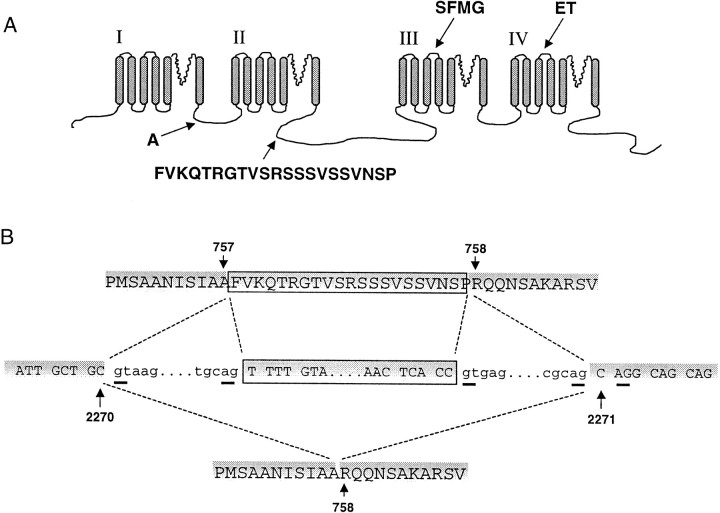

In a previous study, we identified two short cassette exons in S3–S4 linkers of domains III and IV of the Ca channel α1B subunit gene (see Fig.1A) (Lin et al., 1997, 1999). Alternative splicing of these exons was tissue-specific and influenced both the voltage-dependence and rate of Ca channel activation. A third variant site in loop I–II of the of α1B gene involving one amino acid (A415) originated from the random use of alternative 3′ acceptor–splice sites, but it is not associated with any obvious change in channel gating (Lin et al., 1997). In the present study, we characterize a larger alternatively spliced sequence encoding 21 amino acids in the cytoplasmic II–III loop of the α1B gene (see Fig.1A) first identified in mouse neuroblastoma cells (Coppola et al., 1994) and more recently shown by PCR analysis to be present in rat brain (Ghasemzadeh et al., 1999). We report the genomic structure of this site in the rat α1B gene, detail the differential expression of this exon in the rat nervous system, and assess its impact on channel function.

Fig. 1.

Sites of alternative splicing in the N-type calcium channel α1B subunit. A, Putative membrane topology of the α1B subunit and location of four alternatively spliced sequences encoding Ala415 in intracellular loop I–II (A), 21 amino acids in intracellular loop II–III (FVKQTRGTVSRSSSVSSVNSP), four amino acids in IIIS3–IIIS4 (SFMG), and two amino acids in IVS3–IVS4 (ET). With the exception of Ala415 whose expression depends on the use of alternative 3′ splice–acceptors, expression of the other three sites is regulated by alternative splicing of isolated exon cassettes (Lin et al., 1997, 1999). B, Genomic sequence derived from analysis of the α1B gene in the region of the intracellular II–III loop (middle) together with the amino acid sequences of two cDNAs derived by RT-PCR from rat neurons(top, bottom). The location of exons (uppercase letters, shaded), introns (lowercase), the 63 base exon cassette (boxed), and splice junction consensusag-gt dinucleotide sequences (underlined) are indicated. Nucleotides 2270 and 2271and amino acids A757 (757) and R758 (758) denote the splice junction (numbering according to GenBank sequence M92905) (Dubel et al., 1992).Dashed lines indicate the two patterns of alternative splicing that give rise to +21α1B (top) and Δ21α1B (bottom). The genomic sequence of this region is available under GenBank accession number AF222338.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genomic analysis. A 6.3 kb region of the rat α1B gene was amplified from liver genomic DNA using primers directed to 5′ and 3′ exons flanking the splice junction of interest in the II–III loop region. Primer sequences were as follows: Bup2170, (5′-GAG GAG ATG GAA GAG GCA GCC AAT-3′); and Bdw2361, (5′-CTC CGG GTC CAT CTC ACT GTA CAG T-3′). The 50 μl PCR reaction mix contained 250 ng of rat liver genomic DNA, 350 μm each deoxynucleotide and 0.4 μm each primer. After a 15 min preincubation at 92°C, 0.75 μl of enzyme mix (Expand Long Template; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) was added to “hot start” the reaction. After 30 amplification cycles, a single 6.3 kb product was generated and subsequently gel-purified, subcloned, and sequenced by primer walking (Yale University Sequencing Facility, New Haven, CT). The sequence is available under GenBank accession number AF222338.

Reverse transcription-PCR. Total RNA was isolated from different regions of the adult rat nervous system using the guanidium–thiocyanate method and used for first strand cDNA synthesis; 4–6 μg of RNA from CNS tissue or 1–2 μg of RNA from sensory and sympathetic ganglia was used as template in each 20 μl reaction mix containing 0.5 mm each deoxynucleotide, 50 ng/μl random hexamers, 10 mm DTT, and 200 U Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), incubated for 1 hr at 37°C. One microliter of cDNA from each reverse transcription (RT) reaction (or 3 μl from pituitary RT reaction) was used for PCR amplification in a 50 μl standard reaction mix using the following protocol: 1 cycle at 94°C for 2 min, 30 cycles at 94°C for 10 sec, 59°C for 35 sec, 72°C for 50 sec, and 1 cycle at 72°C for 8 min. Primers Bup2104 (5′-TTG AAC GTT TTC TTG GCC ATT GCT GT) and Bdw2363 (5′- CTC CTC CGG GTC CAT CTC ACT GTA CA) were located in 5′ and 3′ exons flanking the splice junction. Negative controls that lacked template confirmed that reagents were not contaminated by α1B cDNA clones. The primers flanked a 6.1 kb intron so contamination by genomic DNA could be ruled out, and reverse transcriptase-lacking controls were also performed. Thirty rounds of amplification were used routinely in our analysis. To control for the possibility of saturation, the number of cycles was increased stepwise from 10, 15, 20, 25, to 30 in one experiment. Products were first observed after 25 cycles, and relative band intensities were identical to those observed after 30 cycles. Band intensities were quantified and normalized to the size of the DNA fragments using a gel documentation system (Alpha Inotech).

Functional assessment of the Ca channel α1B cDNA constructs. The N-type Ca channel α1B-b splice variant (Lin et al., 1997) (GenBank accession number AF055477) referred to here as Δ21α1B was used as template for constructing the +21α1B splice variant (GenBank accession number AF222337) by standard cloning methods. Δ21α1B and +21α1Bsplice variants were cloned into the Xenopus β-globin vector pBSTA to facilitate functional expression (Goldin and Sumikawa, 1992). Functional properties of Δ21α1B and +21α1B were assessed in the Xenopusoocyte expression system using methods and procedures essentially as described previously (Lin et al., 1997, 1999). Forty-six nanoliters of α1B (67–400 ng/μl) and β (22–133 ng/μl) cRNA mix (α1B/β is 3:1 μg/μg) were injected into defolliculated Xenopus oocytes, and currents were recorded 3–5 d later. Before recording, oocytes were injected with 46 nl of a 50 mm BAPTA solution to reduce activation of the endogenous Ca-activated Cl− current (Lin et al., 1997). N-type Ca2+ channel currents were recorded with the two microelectrode voltage-clamp technique using electrodes of 0.8–1.5 and 0.3–0.5 MΩ resistance (3 m KCl) for voltage and current electrodes, respectively. Recording solutions contained either 5 mm BaCl2 or 2 mmCaCl2, 85 mm tetraethylammonium, 5 mm KCl, and 5 mm HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.4 with methanesulfonic acid. The β1b subunit used in this study was provided by K. P. Campbell (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA) (Pragnell et al., 1992); β2a and β4 was provided by E. Perez-Reyes (Loyola University, Maywood, IL) (Perez-Reyes et al., 1992; Castellano et al., 1993b), and β3 was cloned in our lab from rat brain and is almost identical to the published rat brain sequence (Castellano et al., 1993a). Both Ca channel α1Bsplice variants expressed equally well in Xenopus oocytes [e.g., in the presence of β3, the average N channel current amplitude was 2.68 ± 0.26 μA (n= 8) compared with 2.46 ± 0.11 μA (n = 7) for +21α1B and Δ21α1B, respectively]. With the exception of β4, Ca currents were twofold to threefold larger in oocytes expressing α1B together with a β subunit. β4 did not increase current amplitude, but it did modulate N channel gating, confirming that it was expressed (see Results). Data were acquired on-line and leak subtracted using a P/4 protocol (pClamp V6.0; Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Voltage steps were applied every 10–30 sec depending on the duration of the step, from various holding potentials. Current-voltage and steady-state inactivation relationships and activation and inactivation rates were measured.

RESULTS

We analyzed the α1B gene to determine whether alternative splicing could explain the presence of α1B cDNA variants containing an extra 21 amino acid encoding sequence in the II–III intracellular loop region. The salient features of this region of the α1B gene are presented in Figure1B. A single 6.3 kb product was amplified from rat genomic DNA using PCR primers directed to cDNA sequences flanking the putative alternatively spliced exon. We sequenced this product and showed that codon A757 is interrupted by a 6125 bp intronic sequence that contains consensus gt andag splice junctions (Sharp and Burge, 1997). A 63 base cassette exon was identified midway through the intronic sequence flanked by ag-gt splice junction motifs (Fig.1B) and a polypyrimidine track 5′ to the exon (data not shown). The sequence of the cassette exon corresponds to the 63 base insert, confirming that +21α1B and Δ21α1B variants that we (Fig.2) (Pan et al., 1999) and others have observed in the II–III loop region of α1B mRNA (Coppola et al., 1994; Ghasemzadeh et al., 1999) arise from alternative splicing. In their study, Coppola et al. (1994) showed that the alternatively expressed sequence contained 66, rather than 63, bases. This is because all α1B cDNAs isolated from mouse neuroblastoma cells that lacked the 63 base exon sequence also lacked three bases encoding R758. Figure 1B shows that the R758 codon is not part of the isolated 63 base exon but rather is contiguous with the 3′ flanking exon, and its expression depends on the use of alternative dinucleotide, ag, splice–acceptors at this distal 3′ intron–exon boundary (flanking nucleotide 2271) (Fig. 1B). Use of the first splice–acceptor site would result in α1B mRNA containing the R758 codon, whereas R758 would be skipped if the second splice–acceptor site is used. All α1B clones that we have so far isolated from rat contain R758, but the presence of R758-lacking α1B clones in mouse neuroblastoma cells (Coppola et al., 1994) and bovine chromaffin cells (Cahill et al., 2000) confirms that both splice–acceptor sites are used. We have not investigated the expression pattern or the functional consequences of R758 but rather focused on the 63 base cassette exon.

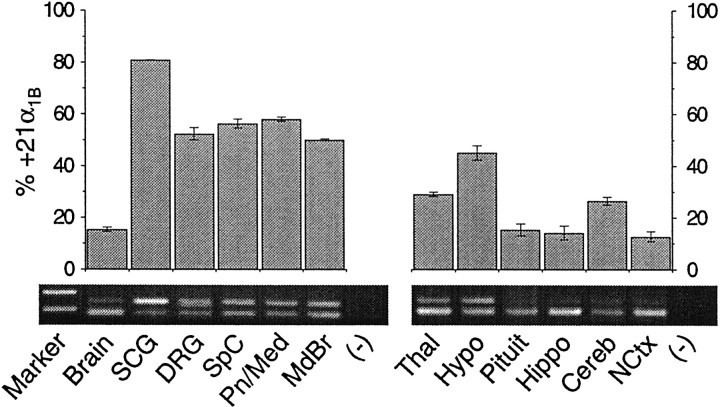

Fig. 2.

Expression pattern of +21α1B and Δ21α1B mRNAs in various regions of the nervous system of the adult rat. Top, Summary of RT-PCR analysis showing the relative abundance of the +21α1B mRNA variant expressed as a fraction of total α1B mRNA derived from brain (Brain), superior cervical ganglia (SCG), dorsal root ganglia (DRG), spinal cord (SpC), pons and medulla (Pn/Med), midbrain (MdBr), thalamus (Thal), hypothalamus (Hypo), pituitary (Pituit), hippocampus (Hippo), cerebellum (Cereb), neocortex (NCtx), and template negative PCR controls (−). Data were averaged from analysis of at least three different RNA samples for each tissue isolated from multiple rats (mean ± SE).Bottom, Example of PCR-derived cDNAs separated by electrophoresis in 2% agarose. Two cDNA products were amplified from each sample (285 and 348 bp) corresponding to Δ21α1Band +21α1B mRNA. The first lane shows 300 and 400 bp size markers. One microliter of RT reaction, except for pituitary (3 μl), was used as template for PCR amplification for all RNA samples. Relative band intensities were estimated using Alpha Inotech gel documentation software and normalized for size differences.

To determine the expression pattern of the 63 base cassette exon, we analyzed RNA isolated from different regions of the nervous system of the adult rat by RT-PCR (Fig. 2). PCR primers that flanked the splice junction were chosen to generate two readily separable size cDNA products (348 and 285 bp) corresponding to +21α1B and Δ21α1BmRNAs, respectively. Contamination by genomic DNA could be excluded because the primers flanked a 6.1 kb intron. By measuring relative band intensities, we show that exon expression is differentially regulated in different regions of the nervous system. +21α1B mRNA dominates in sympathetic ganglia (80.8 ± 0.2% of total α1B,n = 3), whereas exon expression is suppressed in α1B mRNA isolated from whole brain (15.3 ± 0.8% of total α1B, n = 3). Exon expression was not, however, suppressed uniformly throughout the CNS. Although relatively low levels of +21α1B mRNA (<20% total α1B) were present in neocortex, hippocampus, and pituitary, reflecting the pattern in whole brain, significant amounts of both splice variants (+21α1B and Δ21α1B) were detected in more caudal regions of the CNS, including spinal cord and brainstem.

Having established that alternative splicing in the II–III intracellular loop region of α1B is strongly region-specific, we next determined whether exon expression affected channel function. The kinetics and voltage dependence of N-type Ca channel activation and inactivation were studied in oocytes expressing Δ21α1B and +21α1Bsplice variants. At least three different β subunits copurify with α1B in native membranes (Scott et al., 1996), and heterologous expression studies have shown that multiple β subunits modulate N-type Ca channel function (Walker and De Waard, 1998). We therefore thought it pertinent to assess the functional impact of splicing in the presence of four different Ca channel β subunits known to be expressed in rat brain (β1b, β2a, β3, and β4) (Pragnell et al., 1991; Perez-Reyes et al., 1992; Castellano et al., 1993a,b).

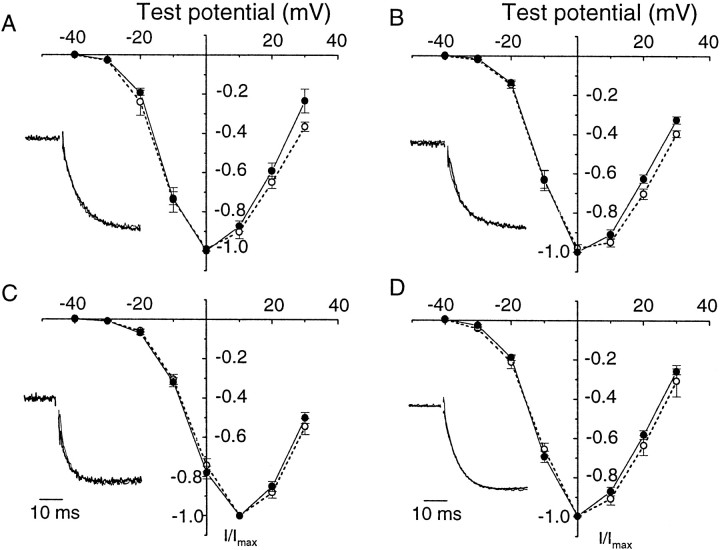

Figure 3 compares N-type currents induced by expressing Δ21α1B and +21α1B splice variants in Xenopusoocytes in the presence of each β subunit. Δ21α1B and +21α1Bsplice variants expressed equally well in oocytes, and their normalized, peak current–voltage curves and channel activation kinetics were indistinguishable. Peak current–voltage curves for Ca channels recorded from oocytes expressing β3were shifted by ∼10 mV in the depolarizing direction relative to β1b, β2a, and β4 similarly for both α1B splice variants (see also Fig.5A). We therefore conclude that the presence of an additional 21 amino acids in the cytoplasmic II–III loop of the α1B subunit does not affect the kinetics or voltage dependence of N-type Ca channel opening.

Fig. 3.

+21α1B and Δ21α1Bsplice variants have similar voltage- and time-dependent activation properties. Normalized, averaged peak current–voltage plots were calculated from Xenopus oocytes expressing Δ21α1B (●) and +21α1B (○) subunits together with Ca channel β1b (A), β2a (B), β3(C), and β4(D) subunits. Currents were activated by brief depolarizations to various test potentials from a holding potential of −80 mV. Barium (5 mm) was the charge carrier. Normalized, averaged current traces for Δ21α1B (thick line) and +21α1B (thin line) are shown superimposed as insets in A–D. Currents shown were activated by depolarization to −10 mV for β1b, β2a, and β4 and, to compensate for its different voltage-dependent activation, to 0 mV for β3. Activation midpoints for currents induced by the expression were as follows: +21α1B/β1b, −12.7 ± 0.8 mV (n = 5); +21α1B/β2a, −12.1 ± 0.7 mV (n = 6); +21α1B/β3, −5.5 ± 0.7 mV (n = 5); and +21α1B/β4, −13.2 ± 0.5 mV (n = 7). These values were not significantly different from Δ21α1B (see legend to Fig. 5 for Δ21α1B values).

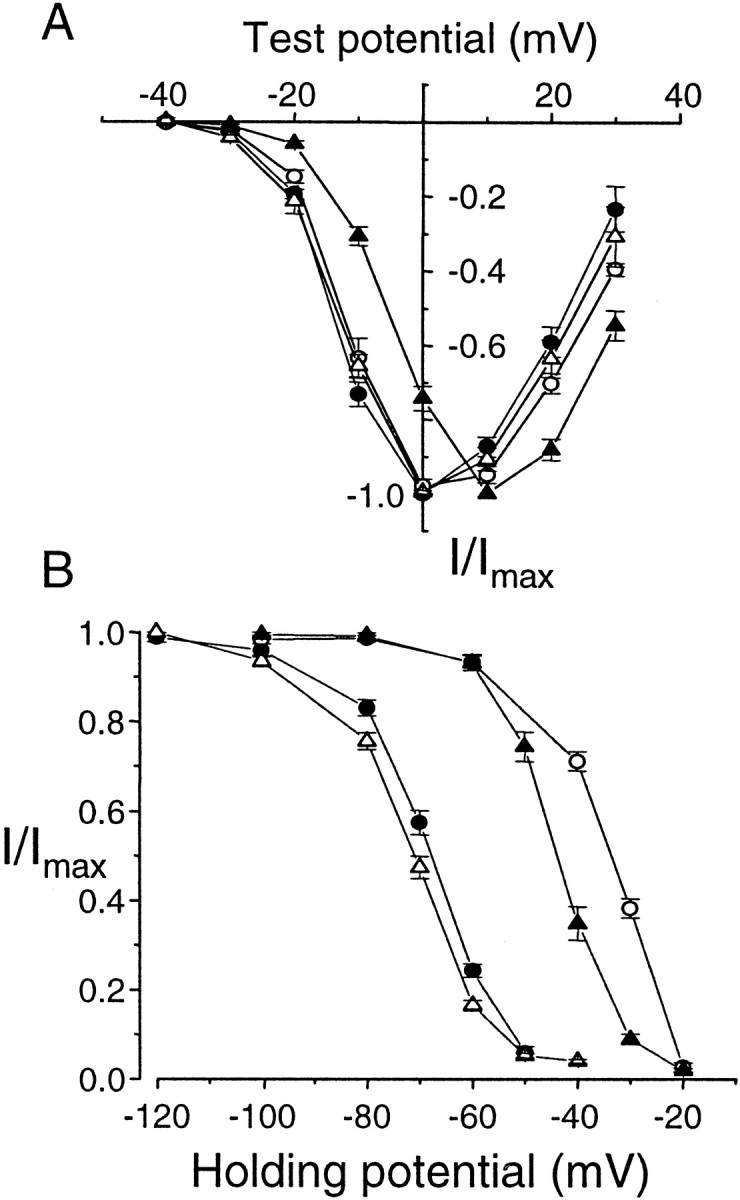

Fig. 5.

Functional differences in α1Bcoexpressed with different Ca channel β subunits. N-type Ca channel currents induced by coexpressing Δ21α1B with β1b(●), β2a (○), β3(▴), and β4 (▵) subunits in Xenopus oocytes. Barium (5 mm) was the charge carrier. A, Currents activated by step depolarizations to various test potentials from a holding potential of −80 mV. Normalized, averaged peak current–voltage plots for each β subunit are shown. Each point is mean ± SE. Activation midpoints were as follows: Δ21α1B/β1b, −13.6 ± 0.6 mV (n = 6); Δ21α1B/β2a, −11.7 ± 1.1 mV (n = 6); Δ21α1B/β3, −4.6 ± 1.0 mV (n = 4); and Δ21α1B/β4, −13.2 ± 0.5 mV (n = 5). In the presence of β3, currents activated at voltages ∼10 mV more depolarized compared with β1b, β2a, and β4. B, Average, steady-state inactivation curves of Δ21α1Bchannels expressed with different β subunits. Currents were activated by depolarizations to 0 mV from different holding potentials. Peak currents were measured and expressed relative to maximum current (holding potential, −120 to −100 mV). Inactivation midpoints were as follows: Δ21α1B/β1b, −68.5 ± 0.8 mV (n = 6); Δ21α1B/β2a, −34.1 ± 0.7 mV (n = 5); Δ21α1B/β3, −43.8 ± 1.0 mV (n = 5); and Δ21α1B/β4, −71.2 ± 0.7 mV (n = 6).

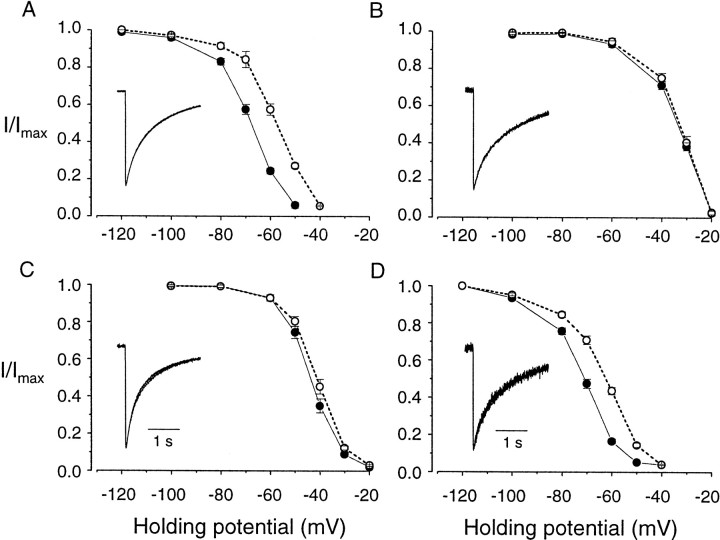

N-type Ca channels recorded from native cells vary considerably in their voltage dependence and kinetics of inactivation (Bean, 1989). We therefore compared both the time course of inactivation and steady-state inactivation curves of Δ21α1Band +21α1B splice variants in the presence of different β subunits. Normalized, averaged currents recorded from oocytes expressing each α1B/β combination are shown as insets in Figure4A–D. Inactivation kinetics of the splice variants are indistinguishable in the presence of a given β subunit, and superimposed averaged currents overlap almost perfectly. The kinetics of N-type Ca channel inactivation did, however, vary depending on the type of β subunit expressed. For example, N-type Ca channel currents recorded in β1b- and β3-expressing oocytes inactivate with relatively fast time courses compared with β2a similarly for both α1B splice variants (Fig. 4). These findings are consistent with other studies that associate the presence of β2a with relatively slowly inactivating Ca channels (Olcese et al., 1994; Walker and De Waard, 1998). Alternative splicing in the II–III loop of the α1B subunit does not, therefore, affect channel inactivation kinetics during step depolarizations to relatively positive voltages. However, a significant difference in the N-type Ca channel availability curve was observed between Δ21α1B and +21α1B when the holding potential was varied. N-type Ca channels induced by expressing +21α1Bsplice variant with β1b and β4 inactivated at membrane potentials that were ∼10 mV more depolarized relative to Δ21α1B(Fig. 4A,D; see also Fig.6B). These differences were only revealed in the presence of specific α1B/β subunit combinations because steady-state inactivation curves were similar between α1B splice variants when coexpressed with β2a and only slightly different in the presence of β3 (Fig.4B,C; see also Fig.6B).

Fig. 4.

+21α1B and Δ21α1Bsplice variants have different steady-state inactivation curves depending on which β subunit is coexpressed. Normalized, averaged steady-state inactivation curves were calculated from currents activated by brief depolarizations to 0 mV from various holding potentials in oocytes expressing Δ21α1B (●) and +21α1B (○) subunits together with Ca channel β1b (A), β2a(B), β3 (C), and β4 (D) subunits. Normalized, averaged currents activated by long depolarizations to +20 mV are also shown for Δ21α1B (thick line) and +21α1B (thin line) to compare inactivation kinetics (insets, A–D). Barium (5 mm) was the charge carrier. Midpoints of steady-state inactivation curves for currents induced by the expression were as follows: +21α1B/β1b, −58.1 ± 0.8 mV (n = 6); +21α1B/β2a, −33.0 ± 0.8 mV (n = 5); +21α1B/β3,=−41.5 ± 0.9 mV (n = 5); and +21α1B/β4, −63.3 ± 0.8 mV (n = 6). Values for Δ21α1Bcurrents are in the legend to Figure 5.

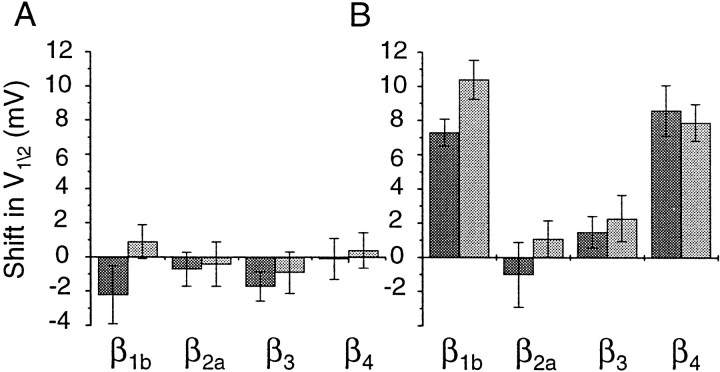

Fig. 6.

Functional differences between α1Bsplice variants are β subunit-specific. Average shifts in channel activation (A) and steady-state inactivation (B) midpoints between Δ21α1B and +21α1B splice variants in the presence of different Ca channel β subunits. Currents were measured using 2 mm Ca (dark shading) and 5 mm Ba (light shading) as the permeant ions. Midpoints of activation calculated from current–voltage plots using 2 mm Ca were as follows: Δ21α1B/β1b, −13.9 ± 1.2 mV (n = 7); Δ21α1B/β2a, −7.9 ± 0.8 mV (n = 6); Δ21α1B/β3, −5.3 ± 0.6 mV (n = 4); and Δ21α1B/β4, −14.9 ± 1.1 mV (n = 5); and compared with +21α1B/β1b, −16.1 ± 1.2 mV (n = 5); +21α1B/β2a, −8.6 ± 0.6 mV (n = 6); +21α1B/β3, −7.0 ± 0.6 mV (n = 5); and +21α1B/β4, −15.0 ± 0.5 mV (n = 5). Midpoints from steady-state inactivation curves using 2 mm Ca as charge carrier were as follows: Δ21α1B/β1b, −72.1 ± 0.6 mV (n = 6); Δ21α1B/β2a, −37.0 ± 1.6 mV (n = 5); Δ21α1B/β3, −41.9 ± 0.6 mV (n = 5); and Δ21α1B/β4, −72.7 ± 1.3 mV (n = 7); and compared with +21α1B/β1b, −64.4 ± 0.5 mV (n = 6); +21α1B/β2a, −38.0 ± 1.0 mV (n = 5); +21α1B/β3, −40.4 ± 0.7 mV (n = 5); and +21α1B/β4, −64.1 ± 0.7 mV (n = 5). Values are mean ± SE. See legends to Figures 3-5 for values with 5 mm Ba as charge carrier.

In Figure 5 we compare normalized current–voltage and steady-state inactivation curves of the four different β subunits expressed with one α1Bsplice variant (Δ21α1B). With the exception of β3, which is associated with Ca channel currents activating at more depolarized voltages (V1/2 of approximately −5 mV), current–voltage relationships were similar between β subunits (Fig.5A). However, a comparison of steady-state inactivation curves highlights how similar inactivation profiles of N-type Ca channels recorded from β1b- and β4-expressing oocytes are to each other on the one hand and different from β2a and β3 on the other. This correlation could be significant in light of the fact that differences between α1B splice variants are only significant when coexpressed with β1b and β4 but not β2a and β3. Figure 5B shows that N-type Ca channels in β1b- and β4-expressing oocytes inactivate at more hyperpolarized voltages (V1/2 of −60 to −80 mV) relative to N-type Ca channels associated with β2a and β3, which inactivate at significantly more depolarized membrane potentials (V1/2 of −35 to −45 mV) (Fig.5B). Similar results were also obtained using 2 mm extracellular calcium rather than 5 mm barium as the permeant ion (Fig.6).

DISCUSSION

Alternative splicing is region-specific

Alternative splicing in intracellular loop II–III of the Ca channel α1B subunit mRNA is differentially regulated in distinct regions of the nervous system. Sympathetic ganglia express the highest levels of exon-containing α1B mRNA (>80% of total), and in the CNS, +21α1B mRNA levels decrease in an approximately caudal to rostral pattern, from ∼50% in brainstem to <20% in neocortex. Overall, exon skipping at this splice site prevails in whole brain, consistent with the absence of the exon in α1B cDNAs isolated previously from rat brain-derived cDNA libraries (Dubel et al., 1992; Fujita et al., 1993). It has been suggested recently that the II–III intracellular loop exon of α1B is preferentially expressed in brain regions of the rat enriched in monoaminergic neurons, based on in situ hybridization and RT-PCR analysis (Ghasemzadeh et al., 1999). Our results do not test this hypothesis directly but nonetheless do favor more widespread distribution. For example, there is a relatively high representation of +21α1B mRNA in regions of the CNS not particularly rich in monoaminergic neurons, such as spinal cord and hypothalamus (Fig. 2). The expression pattern of the II–III intracellular loop exon differs from other splice sites that we have studied previously in the IIIS3–IIIS4 and IVS3–IVS4 extracellular linkers of the α1B subunit, suggesting that the α1B gene contains multiple, independently regulated sites of alternative splicing.

Functional consequences of alternative splicing

The functional effect of lengthening the II–III intracellular loop of the α1B subunit by 21 amino acids is summarized in Figure 6. Exon inclusion did not affect the voltage dependence of channel activation but did induce a shift in the channel availability curve to more depolarized membrane voltages similarly with calcium or barium as permeant ion. These results contrast nicely with our analysis of alternative splicing in the IVS3–IVS4 extracellular linker of the α1B subunit, a domain close to the putative voltage sensor (S4). Splicing in IVS3–IVS4 affected both the voltage dependence and kinetics of channel activation but not inactivation (Lin et al., 1997, 1999).

Functional differences between +21α1B and Δ21α1B splice variants were only observed in the presence of Ca channel β1b or β4 subunits that also shift channel steady-state inactivation curves into the physiologically interesting range of potentials between −60 and −90 mV. In contrast, small or no shifts were observed between the splice variants coexpressed with either β2a or β3 that form N channels that inactivate at significantly more depolarized voltages (−50 to −20 mV). Xenopus oocytes express an endogenous Ca channel β subunit that is highly homologous to mammalian β3 (β3XO) (Tareilus et al., 1997). If present at high enough levels, endogenous β3XO could partially mask the actions of exogenously expressed β subunits; consequently, hyperpolarizing shifts in N-type Ca channel steady-state inactivation curves associated with β1b and β4 might be slightly underestimated. Nonetheless, our results demonstrate that functional differences between α1B splice variants depend on their interactions with specific β subunits.

How does this β subunit specificity arise? One possibility is that β1b and β4 subunits, but not β2a or β3, specifically interact with the 21 amino acid insert in the II–III intracellular loop of α1B. Although the primary β subunit binding site on α1 is in the intracellular loop between domains I and II (Pragnell et al., 1993; De Waard et al., 1994), secondary β-interaction sites in the C-terminal region of α1 have been identified recently (Walker et al., 1998, 1999), leaving open the possibility that additional β-interaction sites in α1, such as in the II–III loop, might exist. Alternatively, β subunit specificity might not depend on direct interactions between β subunits and the II–III intracellular loop of α1B. For example, modification of N-type Ca channel inactivation might be most permissible at membrane potentials between −60 and −90 mV; consequently, differences between splice variants would surface in the presence of β1bor β4 but be less obvious with β2a or β3 subunits. In this case, functional differences between α1Bsplice variants in native cells might also depend on interactions with other Ca channel subunits (e.g., α2δ) and modulators (e.g., G-proteins) that, like β subunits, affect channel inactivation.

Our studies suggest that all α1B/β combinations are permissible and form functional channels in theXenopus oocyte expression system, but which combinations occur in native cells? There is significant overlap in the distribution of α1B and β3 mRNA and protein in mammalian brain but the correlation is not perfect (Ludwig et al., 1997), and biochemical studies have demonstrated significant levels of α1B/β3 and α1B/β4 complexes in native N-type Ca channel proteins isolated from brain (Scott et al., 1996). The study by Scott et al. (1996) does not, however, distinguish between different α1B splice variants. Although α1B, β3, and β4 mRNAs are broadly distributed in brain, in brainstem β1b and β4mRNAs are present to the exclusion of β2a and β3 (Ludwig et al., 1997). Because significant levels of Δ21α1B and +21α1B mRNAs (Fig. 2) are also present in brainstem, we suggest that both α1B splice variants probably form native N-type Ca channels with β subunits other than β3 (i.e., β1b or β4). In light of our results, it will now be important to establish which β subunits associate with which specific α1B splice variant, Δ21α1B and +21α1B, in different regions of the nervous system.

The potential to mix and match multiple α1Bsplice variants and β subunits may represent a mechanism for fine-tuning excitation–secretion coupling at different synapses. We speculate that the availability of N-type Ca channels at synapses dominated by Δ21α1B/β1b or Δ21α1B/β4 complexes may be more sensitive to modulation by agents or stimuli that induce relatively prolonged changes in the resting membrane potential between −60 and −80 mV compared with β2a- or β3-dominant synapses containing either Δ21α1B or +21α1B. Heterogeneity in α1B/β complexes (Scott et al., 1996) probably account for native N-type Ca channel currents in neurons that differ in their sensitivity to inactivation as the membrane potential is depolarized (Bean, 1989; Kongsamut et al., 1989;Plummer et al., 1989). Our results also highlight the II–III intracellular loop of the Ca channel α1Bsubunit as a domain important for regulating N-type Ca channel availability at voltages close to the resting membrane potential. The demonstration that syntaxin, a SNARE [SNAP (solubleN-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein) receptor] that binds to a region in the II–III intracellular loop overlapping the splice junction, also affects the position of the steady-state inactivation curve is consistent with this hypothesis (Bezprozvanny et al., 1995).

Future directions

Our findings provide the framework to begin to address other questions related to the functional significance of splicing in the II–III intracellular loop of the Ca channel α1B subunit. For example, the alternatively spliced exon is unusually enriched in serine and threonine residues (9 of 21), suggesting that Δ21α1B and +21α1B splice variants might be differentially modulated by protein kinase. Furthermore, because the exon overlaps the synaptic protein interaction site on α1B(synprint) (Catterall, 1999), it would be interesting to determine how its presence influences SNARE binding (Sheng et al., 1994; Charvin et al., 1997; Catterall, 1999). Along these lines, there is evidence for isoform-specific interactions of SNAREs with II–III intracellular loop variants of the closely related α1A subunit (Rettig et al., 1996; Catterall, 1999), although the isoforms of α1A reported by Catterall and colleagues do not correspond to the Δ21α1B and +21α1B splice variants described here. Finally, we know very little about the mechanisms that regulate expression of this exon and other alternative spliced exons of α1B in different regions of the nervous system. The identification of regulatory elements presumably in introns upstream of the exon might provide clues as to the nature of the proteins that direct these functionally significant splicing events (Grabowski, 1998).

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS29967 and NS01927 (D.L.). We are grateful to Kevin Campbell for β1b cDNA and Edward Perez-Reyes for β2a and β4 cDNAs. Julie Nam assisted in some of the PCR experiments. We thank members of the Lipscombe laboratory and Dr. Yael Amitai for comments on this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Diane Lipscombe, Department of Neuroscience, 192 Thayer Street, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912. E-mail: diane_lipscombe@brown.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bean BP. Neurotransmitter inhibition of neuronal calcium currents by changes in channel voltage dependence. Nature. 1989;340:153–156. doi: 10.1038/340153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bezprozvanny I, Scheller RH, Tsien RW. Functional impact of syntaxin on gating of N-type and Q-type calcium channels. Nature. 1995;378:623–626. doi: 10.1038/378623a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourinet E, Soong TW, Sutton K, Slaymaker S, Mathews E, Monteil A, Zamponi GW, Nargeot J, Snutch TP. Splicing of alpha 1A subunit gene generates phenotypic variants of P- and Q-type calcium channels. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:407–415. doi: 10.1038/8070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cahill AL, Hurley JH, Fox AP. Coexpression of cloned α(1B), β(2a), and α(2)/Δ subunits produces non-inactivating calcium currents similar to those found in bovine chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1685–1693. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01685.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castellano A, Wei X, Birnbaumer L, Perez-Reys E. Cloning and expression of a third calcium channel beta subunit. J Biol Chem. 1993a;268:3450–3455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castellano A, Wei X, Birnbaumer L, Perez-Reys E. Cloning and expression of a neuronal calcium channel beta subunit. J Biol Chem. 1993b;268:12359–12366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catterall WA. Interactions of presynaptic Ca2+ channels and snare proteins in neurotransmitter release. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;868:144–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charvin N, L'Eveque C, Walker D, Berton F, Raymond C, Kataoka M, Shoji-Kasai Y, Takahashi M, De Waard M, Seagar MJ. Direct interaction of the calcium sensor protein synaptotagmin I with a cytoplasmic domain of the alpha1A subunit of the P/Q-type calcium channel. EMBO J. 1997;16:4591–4596. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coppola T, Waldmann R, Borsotto M, Heurteaux C, Romey G, Mattei M-G, Lazdunski M. Molecular cloning of a murine N-type calcium channel α1 subunit. Evidence for isoforms, brain distribution, and chromosomal localization. FEBS Lett. 1994;338:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Waard M, Scott VE, Pragnell M, Campbell KP. Ca channel beta-subunit binds to a conserved motif in I-II cytoplasmic linker of the alpha-1 subunit. Nature. 1994;368:67–70. doi: 10.1038/368067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubel SJ, Starr TV, Hell JW, Ahlijanian MK, Enyeart JJ, Catterall WA, Snutch TP. Molecular cloning of the α1 subunit of an ω-conotoxin-sensitive calcium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5058–5062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunlap K, Luebke JI, Turner TJ. Exocytotic Ca2+ channels in mammalian central neurons. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujita Y, Mynlieff M, Dirksen RT, Kim MS, Niidome T, Nakai J, Friedrich T, Iwabe N, Miyata T, Furuichi T, Furuichi T, Funutama D, Mikoshiba K, Mori Y, Bean KG. Primary structure and functional expression of the ω-conotoxin-sensitive N-type channel from rabbit brain. Neuron. 1993;10:585–589. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90162-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghasemzadeh MB, Pierce RC, Kalivas PW. The monoamine neurons of the rat brain preferentially express a splice variant of alpha1B subunit of the N-type calcium channel. J Neurochem. 1999;73:1718–1723. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.731718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldin AL, Sumikawa K. Preparation of RNA for injection into Xenopus oocytes. Methods Enzymol. 1992;207:279–297. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07018-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grabowski PJ. Splicing regulation in neurons: tinkering with cell-specific control. Cell. 1998;92:709–712. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81399-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirning LD, Fox AP, McCleskey EW, Olivera BM, Thayer SA, Miller RJ, Tsien RW. Dominant role of N-type Ca2+ channels in evoked release of norepinephrine from sympathetic neurons. Science. 1988;239:57–61. doi: 10.1126/science.2447647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kollmar R, Fak J, Montgomery LG, Hudspeth AJ. Hair cell-specific splicing of mRNA for the alpha1D subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in the chicken's cochlea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14889–14893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kongsamut S, Lipscombe D, Tsien RW. The N-type Ca channel in frog sympathetic neurons and its role in alpha-adrenergic modulation of transmitter release. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1989;560:312–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb24112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin Z, Haus S, Edgerton J, Lipscombe D. Identification of functionally distinct isoforms of the N-type Ca2+ channel in rat sympathetic ganglia and brain. Neuron. 1997;18:153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin Z, Lin Y, Schorge S, Pan JQ, Beierlein M, Lipscombe D. Alternative Splicing of a short cassette exon in α1B generates functionally distinct N-type calcium channels in central and peripheral neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5322–5331. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05322.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludwig A, Flockerzi V, Hofmann F. Regional expression and cellular localization of the α1 and β subunit of high voltage-activated calcium channels in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1339–1349. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01339.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olcese R, Qin N, Schneider T, Neely A, Wei X, Stefani E, Birbaumer L. The amino terminus of a calcium channel beta subunit sets rates of channel inactivation independently of the subunit's effect on activation. Neuron. 1994;13:1433–1438. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan J, Nam J, Lipscombe D. Alternative splicing in the putative II-III loop of the N-type Ca channel α1B subunit. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1999;25:196. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perez-Reyes E, Wei XY, Castellano A, Birnbaumer L. Molecular diversity of L-type calcium channels. Evidence for alternative splicing of the transcripts of three non-allelic genes. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20430–20436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez-Reyes E, Castellano A, Kim HS, Baggstrom E, Lacerda AE, Wei X, Birmaumer L. Cloning and expression of a cardiac/brain beta subunit of the L-type calcium channel. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1792–1797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plummer MR, Logothetis DE, Hess P. Elementary properties and pharmacological sensitivities of calcium channels in mammalian peripheral neurons. Neuron. 1989;2:1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pragnell M, Sakamoto J, Jay SD, Campbell KP. Cloning and tissue-specific expression of the brain calcium channel beta-subunit. FEBS Lett. 1991;291:253–258. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81296-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pragnell M, Sakamoto J, Jay SD, Campbell KP. Cloning and tissue-specific expression of the brain calcium channel beta-subunit. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1792–1797. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81296-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pragnell M, De Waard M, Mori Y, Tanabe T, Snutch TP, Campbell KP. Calcium channel beta-subunit binds to a conserved motif the I-II cytoplasmic linker of the alpha1-subunit. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12359–12366. doi: 10.1038/368067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rettig J, Sheng ZH, Kim DK, Hodson CD, Snutch TP, Catterall WA. Isoform-specific interaction of the alpha1A subunits of brain Ca2+ Channel with the presynaptic proteins syntaxin and SNAP-25. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7363–7368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schorge S, Gupta S, Lin Z, McEnery MW, Lipscombe D. Calcium channel activation stabilizes a neuronal calcium channel mRNA. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:785–790. doi: 10.1038/12153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott VE, De Waard M, Liu H, Gurnett CA, Venzke DP, Lennon VA, Campbell KP. Beta subunit heterogeneity in N-type Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3207–3212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharp PA, Burge CB. Classification of introns: U2-type or U12-type. Cell. 1997;91:875–879. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80479-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheng ZH, Rettig J, Takahashi M, Catterall WA. Identification of a syntaxin-binding site on N-type calcium channels. Neuron. 1994;13:1303–1313. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90417-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soldatov NM. Genomic structure of human L-type Ca2+ channel. Genomics. 1994;22:77–87. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi T, Momiyama A. Different types of calcium channels mediate central synaptic transmission. Nature. 1993;366:156–158. doi: 10.1038/366156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tareilus E, Roux M, Qin N, Olcese R, Zhou J, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. A Xenopus oocyte beta subunit: evidence for a role in the assembly/expression of voltage-gated calcium channels that is separate from its role as a regulatory subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1703–1708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walker D, De Waard M. Subunit interaction sites in voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels: role in channel function. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:148–154. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker D, Bichet D, Campbell KP, De Waard M. A beta 4 isoform-specific interaction site in the carboxyl-terminal region of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel alpha 1A subunit. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2361–2367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker D, Bichet D, Geib S, Mori E, Cornet V, Snutch TP, Mori Y, De Waard M. A new beta subtype-specific interaction in alpha1A subunit controls P/Q-type Ca2+ channel activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12383–12390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]