Abstract

β-amyloid (Aβ) has been proposed to play a role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (AD). Deposits of insoluble Aβ are found in the brains of patients with AD and are one of the pathological hallmarks of the disease. It has been proposed that Aβ induces death by oxidative stress, possibly through the generation of peroxynitrite from superoxide and nitric oxide. In our current study, treatment with nitric oxide generators protected against Aβ-induced death, whereas inhibition of nitric oxide synthase afforded no protection, suggesting that formation of peroxynitrite is not critical for Aβ-mediated death. Previous studies have shown that aggregated Aβ can induce caspase-dependent apoptosis in cultured neurons. In all of the neuronal populations studied here (hippocampal neurons, sympathetic neurons, and PC12 cells), cell death was blocked by the broad spectrum caspase inhibitorN-benzyloxycarbonyl-val-ala-asp-fluoromethyl ketone and more specifically by the downregulation of caspase-2 with antisense oligonucleotides. In contrast, downregulation of caspase-1 or caspase-3 did not block Aβ1–42-induced death. Neurons from caspase-2 null mice were totally resistant to Aβ1–42 toxicity, confirming the importance of this caspase in Aβ-induced death. The results indicate that caspase-2 is necessary for Aβ1–42-induced apoptosis in vitro.

Keywords: β-amyloid, neuronal cell death, caspases, caspase-2, hippocampal neurons, PC12 cells, sympathetic neurons

The histopathological hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease (AD) include the formation of neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, and the loss of synapses (Masters et al., 1985; Selkoe, 1990, 1997). Although the temporal order in which these events occur and their relationship to one another is not clear, a large body of evidence points to a toxic effect of β-amyloid (Aβ), the major protein component of the senile plaque, on neurons (Yankner, 1996; Selkoe, 1997). In cell culture studies, a variety of effects of β-amyloid have been reported. These include induction of apoptotic neuronal death (Ii et al., 1996; Estus et al., 1997), as well as a partial apoptotic program resulting in neuritic changes (Ferreira et al., 1997; Mattson et al., 1998). Aβ1–42 has been proposed to cause death by regulation of components of the apoptotic pathway (Estus et al., 1997), to induce oxidative stress (Pike et al., 1997), and to cause death by free radical-mediated pathways (Keller et al., 1998; Guo et al., 1999). None of these studies has identified obligate mechanisms for Aβ-induced apoptosis. Because synaptic loss, neuritic changes, and cell loss are all features of Alzheimer's disease, activation of the apoptotic cascade, especially the activation of caspases, could explain many of the features of the disease and its progression. Knowledge of which of the 14 known mammalian caspases (for review, see Ahmad et al., 1998; Hu et al., 1998; Humke et al., 1998; Thornberry and Lazebnik, 1998) are activated in response to Aβ and which among these lead to neuritic alterations and apoptotic death will define specific pathways of cellular damage and suggest potential targets for therapeutic intervention. The work reported here examines which of the caspases is required for Aβ to induce apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

PC12 cells. PC12 cells were grown as described previously (Greene and Tischler, 1976; Troy et al., 1997) on rat tail collagen-coated dishes in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) containing 5% fetal calf serum and 10% heat-inactivated horse serum (complete medium). NGF-primed (neuronally differentiated) PC12 cells were grown for at least 7 d in RPMI 1640 medium plus 1% horse serum and NGF (100 ng/ml). For cell survival assays, cells (either naive or NGF-pretreated) were extensively washed in RPMI 1640 medium containing 1% fetal calf serum and replated on fresh collagen-coated 24-well dishes in RPMI 1640 medium 1% FCS, with NGF for primed cells. Various concentrations of Aβ1–42 were included in the medium as indicated. Numbers of viable cells per culture were determined by quantifying intact nuclei as described previously (Troy et al., 1997). Counts were performed on triplicate cultures and reported as mean ± SEM.

Sympathetic neurons. Sympathetic neuron cultures were prepared from 2-d-old rat pups as described previously (Troy et al., 1997) or from 2-d-old caspase-2 −/− and wild-type mouse pups (Bergeron et al., 1998) (generous gifts from L. Bergeron and J. Yuan, Harvard University, Boston, MA). Cultures were grown in 24-well collagen-coated dishes in RPMI 1640 medium plus 10% horse serum with mouse NGF (100 ng/ml). One day after plating, uridine and 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (10 μm each) were added to the cultures and left for 3 d to eliminate non-neuronal cells (<1% non-neuronal cells remain after 3 d). On the sixth day after plating, Aβ1–42 was added. Each culture was scored as described previously (Troy et al., 1997), as numbers of living, phase-bright neurons counted in the same field at various times. Three replicate cultures were assessed for each condition, and data are normalized to numbers of neurons present in each culture at the time of Aβ1–42 addition and reported as mean ± SEM.

Hippocampal neurons. Primary cultures of dissociated hippocampal neurons were prepared from embryonic day 18 (E18) rats (Farinelli et al., 1998). E18 hippocampi were dissected, dissociated, and maintained in a serum-free environment. Medium consists of a 1:1 mixture of Eagle's MEM and Ham's F12 supplemented with glucose (6 mg/ml), putrescine (60 μm), progesterone (20 nm), transferrin (100 μg/ml), selenium (30 nm), penicillin (0.5 U/ml), and streptomycin (0.5 μg/ml). Dissociates grown in this medium contain <2% glial cells after 1 week. Cells were treated with Aβ1–42after 3–5 d in culture. Survival was quantified as described above for PC12 cells.

Preparation of amyloid

Lyophilized, HPLC-purified β-amyloid1–42 was purchased from D. Teplow (Harvard University), and reverse Aβ42–1 was from Bachem (Torrance, CA). Peptides were reconstituted in sterile water at a concentration of 400 μm. Aliquots of stocks were incubated at 37°C for 3 d to form aggregated amyloid.

Bioassay of NGF

Aliquots of RPMI with NGF (100 ng/ml) with and without Aβ1–42 (10 μm) were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and then spun down. The supernatant was added to PC12 cells deprived of trophic factors as described previously (Greene et al., 1998). Cells were grown for 1 d, and survival was quantified as described above.

Superoxide dismutase-specific activity

Cells were extracted with 0.5% NP-40, and protein was measured by the Bradford method (Troy and Shelanski, 1994). Total and manganese-superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD) levels were determined with a modification of the xanthine–xanthine oxidase system, measuring the reduction of nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) at 560 nm in the absence and presence of potassium cyanide (KCN) (Troy and Shelanski, 1994). Briefly, cell extracts or SOD (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were incubated in 50 mm sodium carbonate buffer at pH 10.2 containing 0.1 mm EDTA, 1 × 10−4m xanthine, 1 mm KCN, 2.5 × 10−5m NBT, and 2.2 × 10−9m xanthine oxidase in a volume of 1 ml. Reduction of NBT was measured at 560 nm. Total SOD activity was determined from an SOD standard curve in the absence of KCN. Copper/zinc-SOD is inhibited by KCN. Thus, only Mn-SOD activity remains in the presence of KCN; Mn-SOD activity is reported as the KCN-insensitive activity.

Caspase activity assay

Preparation of cell lysates. At 6 hr after Aβ1–42 treatment, cells were harvested for assays of aspartase activity or Western blotting. Cells were rinsed in cold PBS and then collected in a buffer of 25 mmHEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm DTT, 10 μg/ml each of pepstatin and leupeptin, and 1 mm PMSF. The cellular material was left for 20 min on ice and then sonicated on ice. The lysate was centrifuged for 20 min at 160,000 × g, and the supernatant was frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C (Stefanis et al., 1996).

Cleavage of fluorogenic substrates. Lysates (25 μg of protein) were incubated at 37°C in a buffer of 25 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 10% sucrose, 0.1% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate, and 10 mm DTT with the fluorogenic substratesN-acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-7-amino-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin (DEVD-AFC) (15 μm) or benzyloxycarbonyl-Tyr-Val-Ala-Asp-7-amino-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin (YVAD-AFC) (25 μm) (Enzyme Systems Products, Dublin, CA). Cleavage of the substrates emitted a fluorescent signal that was measured in a Perkin-Elmer (Emeryville, CA) LS-50B fluorometer (excitation of 400 nm, emission of 505 nm).

Synthesis of antisense oligonucleotides

Oligonucleotides bearing an SH group at their 5′ end and an NH group at their 3′ end were purchased from Operon (Alameda, CA). As described previously (Troy et al., 1996a), oligonucleotides were resuspended in deionized water, an equimolar ratio of Penetratin 1 (Oncor Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 hr. The yield of the reaction, estimated by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie blue staining, was routinely above 50%. As a control, a scrambled sequence of the antisense oligonucleotide (same base composition, different order) was used. Antisense sequences used were as follows: ACasp1, CCTCAGGACCTTGTCGGCCAT; ACasp2, GCTCGGCGCCGCCATTTCCCAG; and ACasp3, GTTGTTGTCCA TGGTCACTTT.

Western blotting

Neuronal cells were harvested in lysis buffer as described above or in SDS-containing sample buffer and immediately boiled. Equal amounts of protein were separated by 15% PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunostained as described previously (Stefanis et al., 1997). Anti-caspase-1 (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY) was used at a dilution of 1:500. Anti-caspase-2 (Troy et al., 1997) was used at a dilution of 1:250. Anti-caspase-3 was a generous gift from J. L. Goldstein (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX) (Wang et al., 1996) and was used at a dilution of 1:1000. Visualization was with ECL using goat-anti-rabbit peroxidase at 1:1000. The relative intensity of the protein bands was quantified using Scion NIH Image 1.55 software.

RESULTS

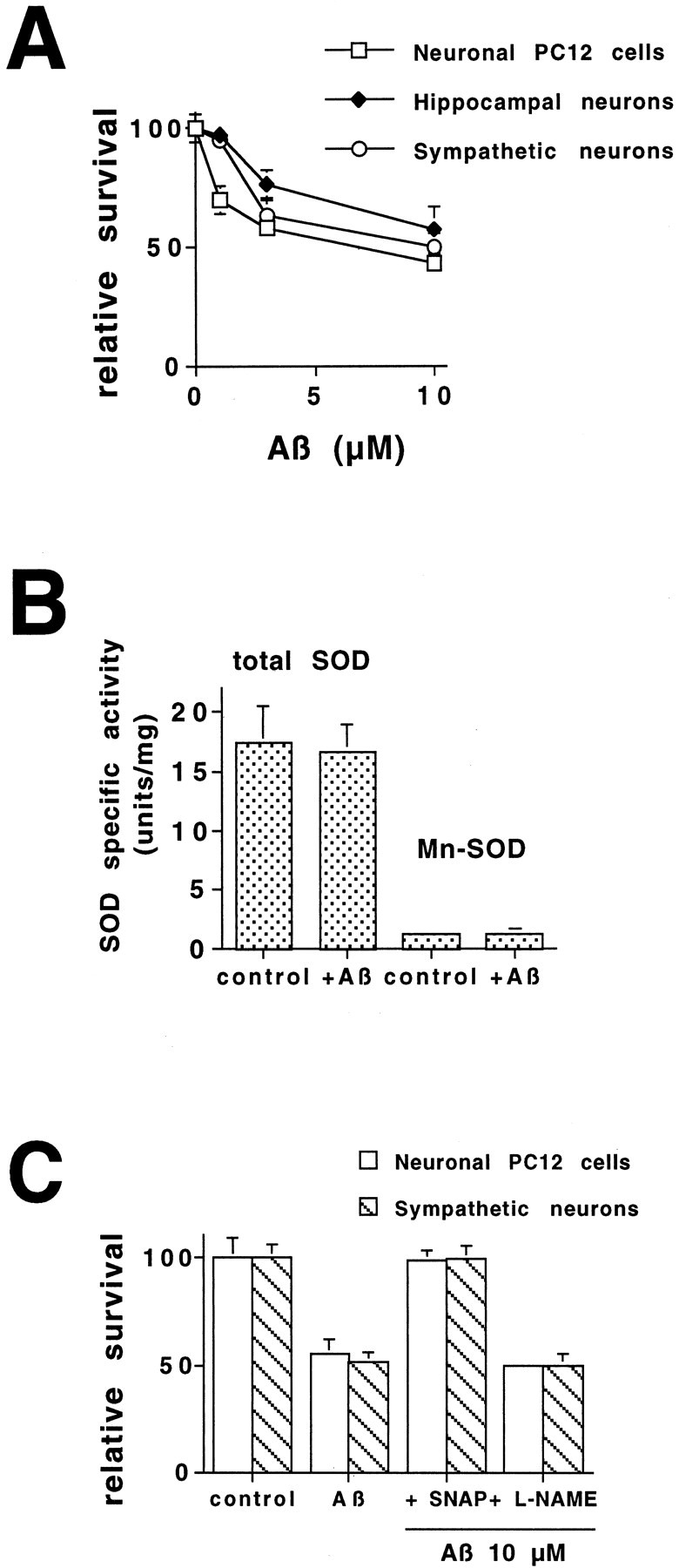

β-Amyloid-induced neuronal cell death is not mediated by peroxynitrite

We studied Aβ-induced death in three different neuronal cell types: PC12 cells, the most widely used neuronal cell line; sympathetic neurons, the neuron for which PC12 cells are a model; and hippocampal neurons, because the hippocampus is affected extensively in AD. Previous studies reporting neurotoxicity of Aβ have used a wide range of concentrations of different forms of Aβ (25–35, 1–40, and 1–42) in a variety of cell types, including cortical neurons, hippocampal neurons, and cultured cell lines (Pike et al., 1991a,b; Ii et al., 1996; Estus et al., 1997; Jordan et al., 1997; Kruman et al., 1997). We have performed dose–response studies with aggregated Aβ1–42 in PC12 cells, sympathetic neurons, and hippocampal neurons (Fig.1A) to determine whether these three neuronal cell types respond in a similar manner. At a concentration of 10 μm, there was equivalent survival (∼50%) of all three neuronal cell types after 1 d of exposure (Fig. 1A). No death was seen in PC12 cell cultures treated with the same concentrations of Aβ42–1, the inactive reverse sequence of Aβ (data not shown), supporting a specific effect of Aβ1–42. All subsequent experiments were done with 10 μm Aβ1–42.

Fig. 1.

Nitric oxide protects against β-amyloid-induced death in neuronal cells. A, Aβ1–42induces dose-dependent death in three different neuronal cell types. E18 hippocampal neurons were grown in culture for 3 d and then exposed to increasing concentrations of Aβ1–42. Survival was assessed after 1 d by counting nuclei in cell lysates (n = 3). Survival is reported relative to untreated cultures and is given as mean ± SEM. Sympathetic neurons were grown in culture for 5 d and then exposed to increasing concentrations of Aβ1–42. Survival was assessed after 1 d by counting cells in the living cultures. Survival is reported relative to that in the same cultures before Aβ1–42treatment and is given as mean ± SEM (n = 3). PC12 cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of Aβ1–42. Survival was assessed after 1 d by counting nuclei in cell lysates (n = 3). Survival is reported relative to untreated cultures and is given as mean ± SEM. These are representative experiments. Comparable results were obtained in six additional independent experiments with hippocampal neurons, in three additional experiments with sympathetic neurons, and in five additional experiments with PC12 cells. B, Mn-SOD is not induced by Aβ1–42 treatment. PC12 cells were treated with or without Aβ1–42 (10 μm) for 6 hr (n = 3). Cells were extracted with 0.5% NP-40, and protein was measured by the Bradford method. Total SOD and Mn-SOD levels were determined by the xanthine–xanthine oxidase system, with measurement of the reduction of nitroblue tetrazolium at 560 nm in the presence and absence of KCN. Mn-SOD activity was determined from an SOD standard curve and is reported as the KCN-insensitive activity ± SEM. C, Increasing NO protects from Aβ1–42-induced neuronal cell death. PC12 cells and sympathetic neurons were exposed to Aβ1–42 (10 μm) in the presence or absence of SNAP (100 μm) or l-NAME (10 μm). Survival was assessed after 1 d as described above (n = 3). This is a representative experiment; comparable results were obtained in three additional independent experiments. Survival is reported relative to untreated cultures and is given as mean ± SEM. Similar results were obtained with cultured sympathetic neurons.

It has been proposed that Aβ toxicity is caused by the induction of oxidative stress (Ii et al., 1996; Kruman et al., 1997;Pike et al., 1997; Keller et al., 1998; Guo et al., 1999). Specifically, Aβ-treated PC12 cells have been shown to produce peroxynitrite (ONOO−), a toxic product of the superoxide anion (O2−), and nitric oxide (NO), and to be protected from Aβ toxicity by the overexpression of Mn-SOD—the inducible, manganese-dependent form of superoxide dismutase normally expressed in the mitochondria (Keller et al., 1998). Mn-SOD has been shown to be increased in response to an increase in O2− (Troy and Shelanski, 1994). Thus, changes in the specific activity of Mn-SOD may afford an indication of O2− levels in the cells. Treatment with Aβ1–42 for 6 hr had no effect on total SOD or Mn-SOD activities in our cultures (Fig.1B). The other component of ONOO−, NO, has been shown to be both neurotoxic and neuroprotective depending on the type of insult to which the cell has been exposed. If peroxynitrite is a component of the Aβ death pathway, then inhibition of NO production should be protective. We have examined the role of NO in Aβ1–42-treated PC12 cells and sympathetic neurons by inhibiting the generation of endogenous NO withN-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) (10 μm), a general inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase, and by treating the cells with the NO generator S-nitroso penicillamine (SNAP) (100 μm) (Fig. 1C). The concentrations of l-NAME and SNAP were selected based on previous work by us and by our colleagues using PC12 cells and sympathetic neurons (Farinelli et al., 1996; Troy et al., 1996a). Inhibition of endogenous NO generation by l-NAME did not protect PC12 cells or sympathetic neurons in the presence of Aβ1–42. Conversely, concurrent treatment with the exogenous NO generator SNAP led to complete protection in these neurons. SNAP alone was toxic to hippocampal neurons. This protective effect of NO is also seen in PC12 cells and sympathetic neurons deprived of NGF (Farinelli et al., 1996), a death paradigm that has been shown to require cell cycle elements.

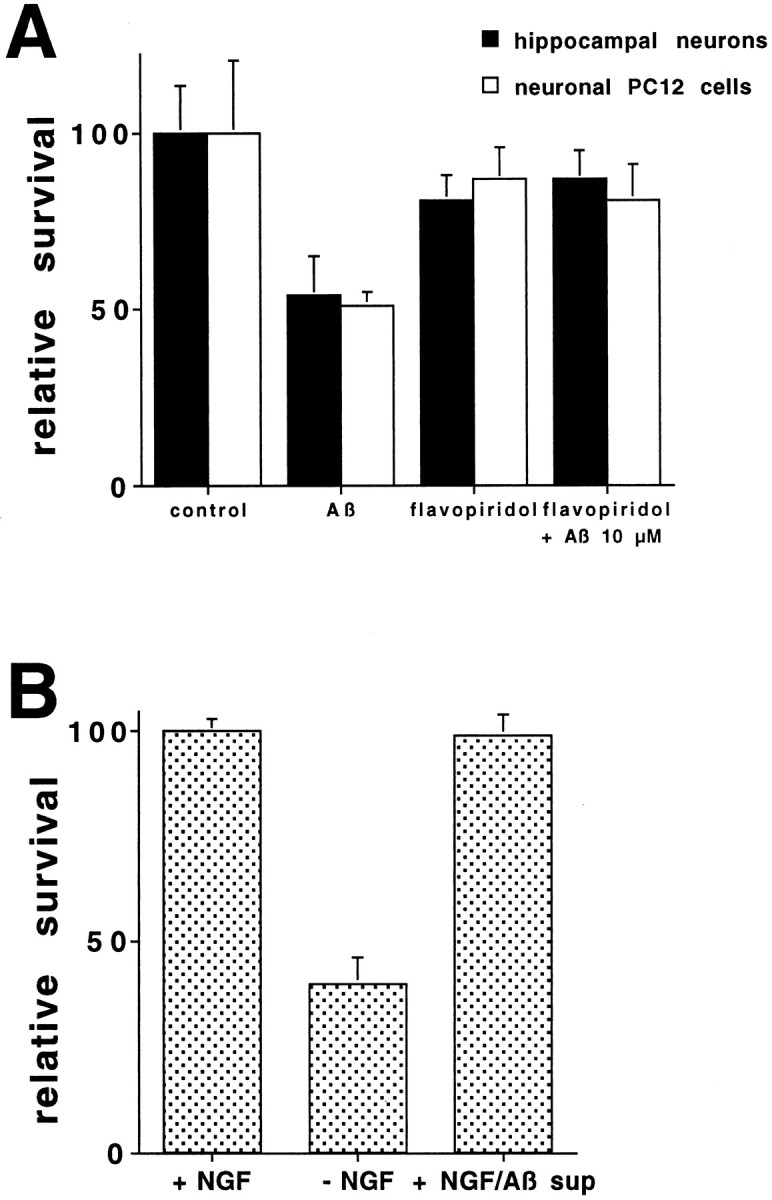

The similarity between the protection profiles in Aβ1–42 exposure and trophic factor deprivation led us to examine whether agents that block cell cycle progression also protect from Aβ1–42. Hippocampal neurons and PC12 cells were treated with Aβ1–42 in the presence or absence of the cell cycle inhibitor flavopiridol. Flavopiridol is a flavonoid derivative that inhibits cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (cdk1), cdk2, and cdk4 activities (Losiewicz et al., 1994; De Azevedo et al., 1996) and is reported to block progression from G1 to S and G2 to M phases of the cell cycle (Kaur et al., 1992;Vesely et al., 1994). Flavopiridol provided protection against Aβ1–42 for both hippocampal neurons and PC12 cells (Fig. 2A). This is in accord with the recent data that elements of the cell cycle are required for 30 μmAβ1–40 to induce death in cortical neurons (Giovanni et al., 1999).

Fig. 2.

A, The cell cycle inhibitor flavopiridol protects hippocampal neurons and neuronal PC12 cells from Aβ1–42 toxicity. Hippocampal cultures and neuronal PC12 cells were treated with Aβ1–42 in the presence or absence of flavopiridol (1 μm) (n = 3). Survival was assessed after 1 d as described in Figure 1, is reported relative to untreated cultures, and is given as mean ± SEM. This is a representative experiment; comparable results were obtained in six additional independent experiments for hippocampal cultures and three additional experiments for PC12 cells.B, Aβ1–42 does not inhibit NGF activity. RPMI with NGF was incubated with or without Aβ1–42 (10 μm) for 30 min at 37°C, and Aβ1–42 was removed by centrifugation. The various media were added to PC12 cells, which had been subjected to trophic factor deprivation. Survival was quantified at 1 d and is given as mean ± SEM (n = 3).

The above lines of evidence support a similar mechanism of death for Aβ and trophic factor deprivation. Because Aβ1–42 induces cell death in primed PC12 cells and sympathetic neurons in the presence of NGF, we considered the possibility that Aβ might bind to NGF in the media and effectively inactivate it, resulting in trophic factor withdrawal. Using an established bioassay for NGF (Greene et al., 1998), we determined that the neurotrophic activity of NGF was not diminished by preincubation with Aβ1–42 in the media (Fig.2B).

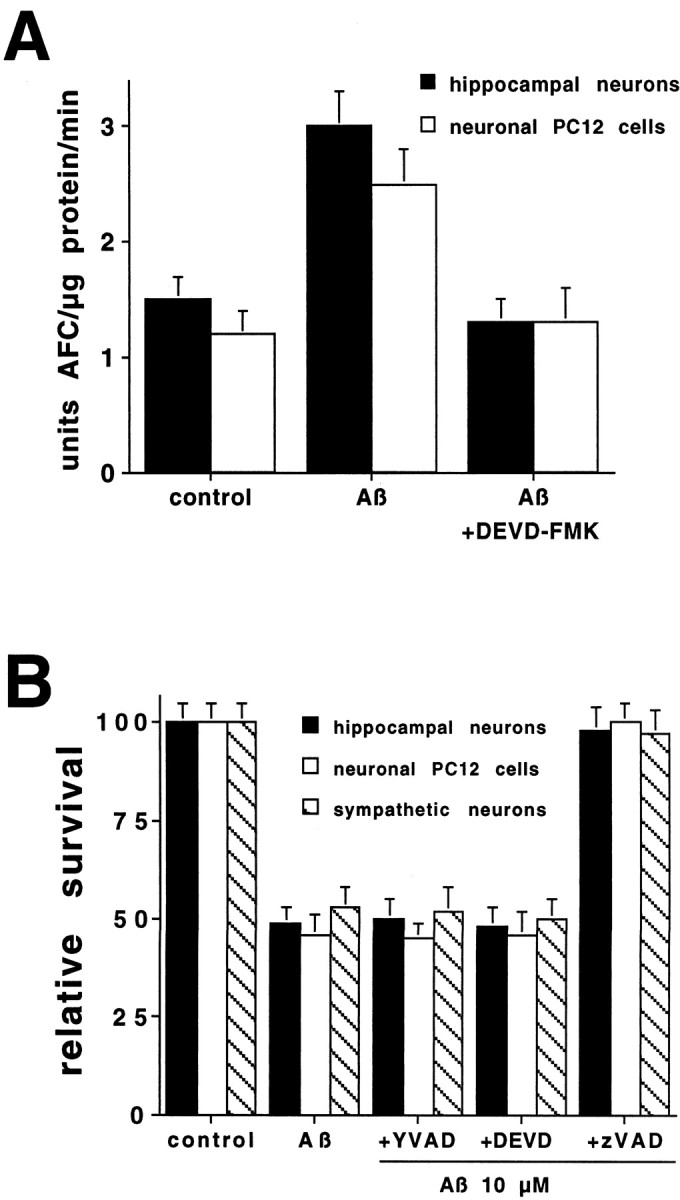

Aβ1–42-induced cell death requires caspase-2

Death induced by Aβ is inhibited by the broad spectrum caspase inhibitor N-benzyloxycarbonyl-val-ala-asp-fluoromethyl ketone (zVAD-FMK), demonstrating that caspase activity is essential for Aβ-induced apoptosis (Jordan et al., 1997; Guo et al., 1999). Treatment of hippocampal neurons or PC12 cells with Aβ1–42 induced caspase activity within 6 hr, as detected by cleavage of DEVD-AFC (Fig.3A), a substrate for caspases related to caspase-3. This peptide is not cleaved by caspase-2 and minimally cleaved by caspase-1 family members (Talanian et al., 1997;Thornberry et al., 1997). The DEVD-AFC cleavage activity was completely prevented by simultaneous treatment of the cultures with Aβ and 10 μm DEVD-FMK, the pseudosubstrate inhibitor (Fig. 3A). There was no cleavage of YVAD-AFC, a substrate for caspase-1 family members, by the same cell lysates (data not shown). No specific substrate is available for caspase-2. Differential use of caspase inhibitors can provide some information about caspase requirements for a particular mode of death. In the studies reported here, we have used several different competitive irreversible pseudosubstrate caspase inhibitors: YVAD-FMK, which inhibits caspase-1, -4, and -5; and DEVD-FMK, which is moderately specific for members of the caspase-3 family [including caspase-3 and -7 (Talanian et al., 1997; Thornberry et al., 1997)] when used at low concentrations (10 μm) and the broad spectrum inhibitor zVAD-FMK. Surprisingly, DEVD-FMK provided no protection against Aβ-induced neuronal cell death (Fig. 3B), despite the complete prevention of the DEVD cleaving activity by this concentration of the inhibitor (Fig. 3A). No rescue from Aβ-induced death was seen with YVAD-FMK (100 μm) (Fig.3B) in any of the three neuronal types. Thus, it is unlikely that caspase-1, -3, or -7 are required for the Aβ apoptotic pathway (caspase-4 and -5 have not been found in rodent cells; J. Angelastro, personal communication). On the other hand, zVAD-FMK gave complete protection (Fig. 3B), confirming that Aβ induces a caspase-mediated death.

Fig. 3.

A, Aβ1–42 induces caspase activity in hippocampal neurons and PC12 cells. Hippocampal neurons and neuronal PC12 cells were treated with Aβ1–42(10 μm) with or without DEVD-FMK (10 μm) for 6 hr. Cells were lysed, and 25 μg of protein of each treatment was incubated with the fluorogenic substrate DEVD-AFC (15 μm). The release of AFC was quantified in an LS50B fluorometer. This is a representative experiment; comparable results were obtained in three additional independent experiments.B, Differential protection by caspase inhibitors from Aβ1–42-induced death. Cultures of hippocampal neurons, PC12 cells, and sympathetic neurons were exposed to Aβ1–42 (10 μm) in the presence or absence of the indicated inhibitors (n = 3): YVAD-FMK at 100 μm, DEVD-FMK at 10 μm, and zVAD-FMK at 50 μm. Cells were counted after 1 d as described in Figure 1. Survival is reported relative to untreated cultures and is given as mean ± SEM.

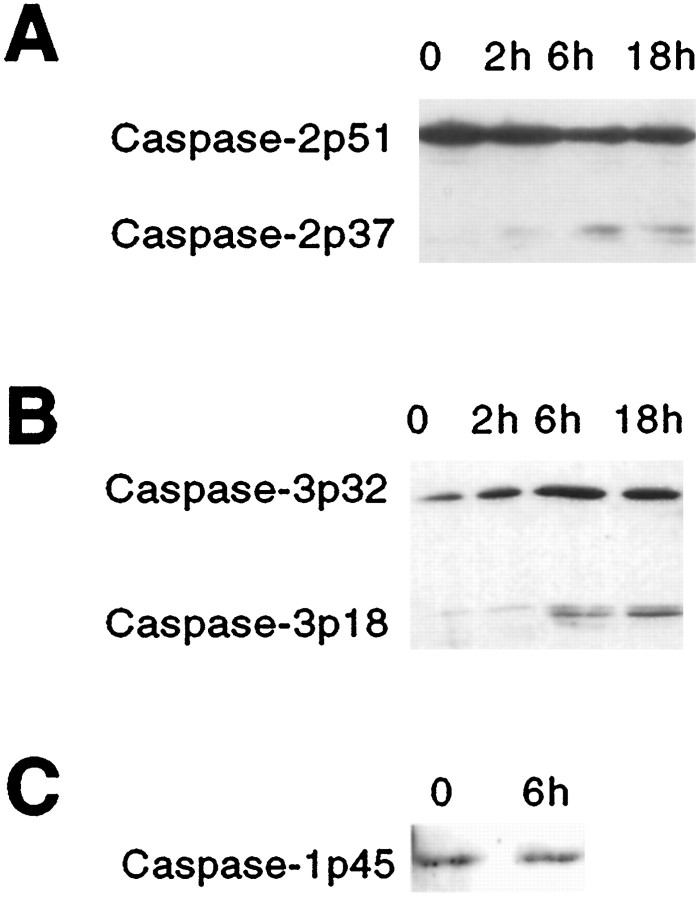

Because the inhibitors can only provide circumstantial evidence about specific caspase activation during death, we used Western blotting with antibodies specific for caspase-1, -2, and -3 to determine whether any of these caspases was activated by Aβ1–42treatment. All three of the caspases were detected in untreated hippocampal neurons (Fig. 4), as well as in PC12 cells and sympathetic neurons (Troy et al., 1997) (data not shown). Hippocampal neurons were treated with Aβ1–42 for 2, 6, and 18 hr, and cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. The antiserum to caspase-2 detects the proform and a p37 peptide, which is an intermediate cleavage product in the formation of the p20 active peptide (Stefanis et al., 1997, 1998). The p37 peptide was detected after 6 hr treatment, a time at which there was a concomitant decrease in the proform caspase-2p51 (Fig. 4A). Caspase-3 also showed an increase in appearance of the p18 active peptide (Fig. 4B), consistent with the changes in DEVD-AFC cleaving activity described above (Fig. 3A). However, the proform of caspase-3, caspase-3p32, also increased over the time course (Fig.4B). There was no activation of caspase-1 apparent at 6 hr (Fig. 4C), concurring with the lack of YVAD-AFC cleaving activity in the lysates prepared at this same time.

Fig. 4.

Caspase-2 and caspase-3 are activated in hippocampal neurons after Aβ1–42 treatment. Hippocampal cultures were incubated with or without Aβ1–42 for the indicated times. Cell lysates (equal amounts of protein, determined by the Bradford method) were subjected to Western blotting using the indicated antisera. Ponceau staining confirmed equal loading. These are representative blots; comparable results were obtained in three independent experiments. A, Caspase-2. B, Caspase-3. C, Caspase-1.

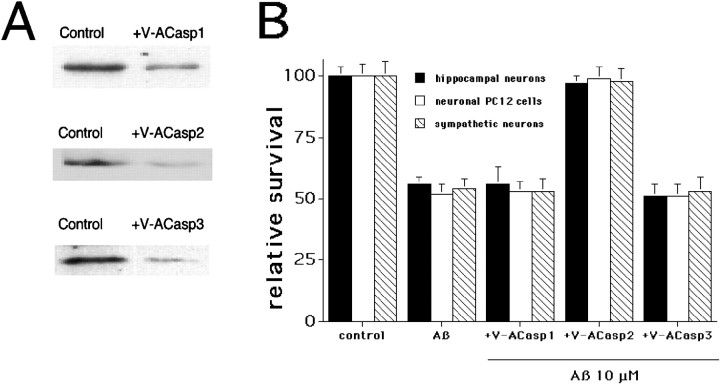

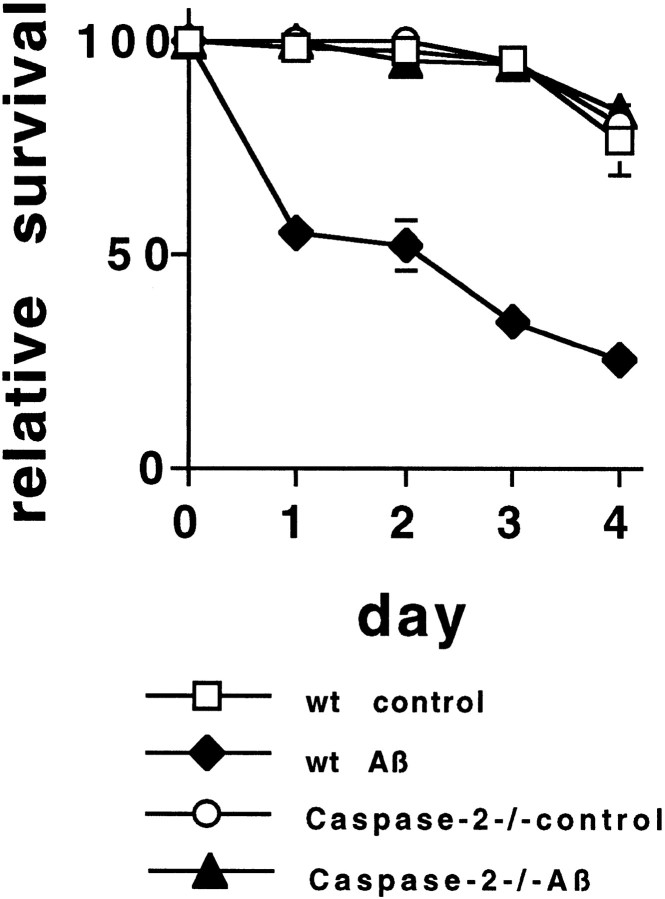

To assess the role of each of these caspases in mediating Aβ1–42-induced death Penetratin1-conjugated antisense oligonucleotides were used to downregulate caspase-1, caspase-2, and caspase-3 independently. Each oligonucleotide specifically downregulates the respective caspase by at least 70% in PC12 cells after 6 hr treatment (Fig.5A). There is no cross regulation of the other caspases; that is, V-ACasp2 does not affect caspase-1 or caspase-3 levels, etc. (Troy et al., 1997) (data not shown). Scrambled oligonucleotides (same base composition) had no effect on protein levels (Troy et al., 1997) (data not shown). When the three antisense oligonucleotides were tested, only the antisense caspase-2 (V-ACasp2) (Fig. 5B) protected from Aβ1–42 damage; cells were treated simultaneously with the antisense oligonucleotides and Aβ1–42. The requirement for caspase-2 in Aβ-induced death was confirmed using cultured sympathetic neurons from caspase-2 null mice (Fig. 6). Sympathetic neurons from postnatal day 1 wild-type and caspase-2 null mice (Bergeron et al., 1998) were grown in culture for 5 d and then treated with Aβ1–42 (10 μm), and survival was quantified daily. Neurons from wild-type mice had 55% survival after 1 d and only 25% survival after 4 d treatment. Neurons from caspase-2 null mice were completely resistant to Aβ1–42 treatment, even after 4 d of exposure (Fig. 6). The sympathetic neurons from caspase-2 null mice were also resistant to 30 μm Aβ1–42, a concentration that gave 20% survival of wild-type neurons after 1 d of treatment, and no survival after 4 d treatment (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Caspase-2 is necessary for Aβ1–42-induced neuronal cell death. A, Specific downregulation of caspase-1, -2, or -3. PC12 cells were treated with the indicated antisense oligonucleotides (240 nm) for 6 hr. Cells lysates were subjected to Western blotting using the appropriate antisera, i.e., anti-caspase-1 for V-ACasp1-treated cells. B, Only downregulation of caspase-2 protects against Aβ1–42-induced neuronal cell death. Cultures of hippocampal neurons, PC12 cells, and sympathetic neurons were treated with 10 μm Aβ1–42 in the presence or absence of the indicated antisense oligonucleotides, each at a concentration of 240 nm (n = 3). Survival was quantified after 1 d, is reported relative to untreated cultures, and is given as mean ± SEM. This is a representative experiment; comparable results were obtained in three additional independent experiments with hippocampal cultures, as well as three additional experiments each with PC12 cells and sympathetic neurons.

Fig. 6.

Sympathetic neurons from caspase-2 null mice are resistant to Aβ1–42 toxicity. Sympathetic neuron cultures from 1-d-old wild-type or caspase-2 null pups were treated with Aβ1–42 (n = 3). Survival was quantified daily, as described in Figure 1. Survival is reported relative to that in the same cultures before Aβ1–42treatment and is given as mean ± SEM (n = 3). This is a representative experiment; comparable results were obtained in four additional independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

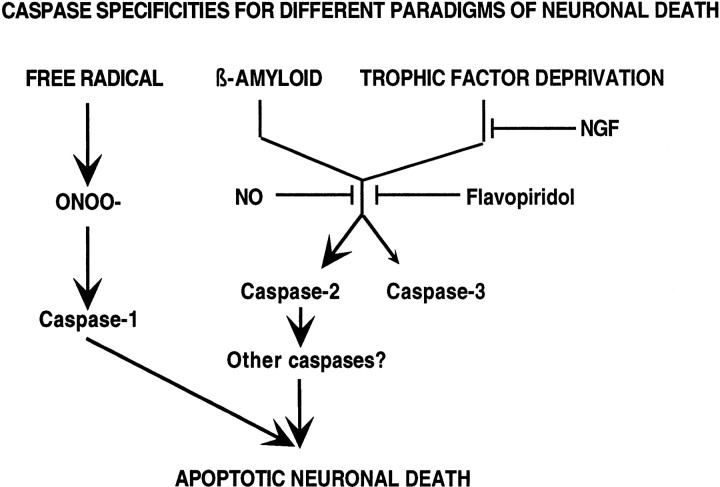

The role of Aβ in the pathogenesis and progression of Alzheimer's disease has not yet been fully determined. It is clear that deposits of insoluble Aβ are found in plaques in the brains, particularly the hippocampus, of patients with AD and that insoluble Aβ can induce apoptotic neuronal cell death in vitro(Selkoe, 1990; Pike et al., 1991b). If indeed Aβ plays an important role in AD, knowledge of the mechanisms used by Aβ to induce neuronal cell death will identify potential molecular targets for development of therapies for AD. Study of model systems of Aβ-induced neuronal cell death allows the delineation of the molecular pathways traversed by Aβ to induce neuronal cell death. A variety of laboratories have presented work showing Aβ induction of apoptosis in multiple cell types in culture (Pike et al., 1991a; Li et al., 1996; Estus et al., 1997; Jordan et al., 1997; Pike et al., 1997; Mattson et al., 1998), and apoptosis is seen in human AD brains as well (Cotman et al., 1994;Cotman and Su, 1996). Recent work from our laboratory has shown that differing insults to neurons result in activation of apoptotic pathways, which use different caspases (Troy et al., 1996b, 1997) (Fig.7). The studies presented here show that Aβ1–42 mediated death in three different neuronal cell types requires the presence of caspase-2 and is accompanied by caspase-2 activation. Although caspase-3 activation occurs, it does not mediate cell death in this paradigm. The activation of caspase-3 may be occurring in parallel with that of caspase-2, or caspase-2 may be activating caspase-3. However, it is clear that the activated caspase-3 is not executing death in our model. Caspases have been classified in several ways, based on both structure and function. Caspase-2 has been classified as either an effector, together with caspase-3 and caspase-7 (Thornberry et al., 1997), or as an initiator (Thornberry and Lazebnik, 1998). Our data would support a role for caspase-2 as an initiator, which then activates other effector caspases or autoactivates so that caspase-2 can act as both initiator and effector to lead to death (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Caspase specificities in different paradigms of cell death. Schematic illustration of the pathways to cell death for β-amyloid, trophic factor deprivation, and free radical-mediated oxidative stress.

AD hippocampus has been shown to have both an increase in caspase-3 immunoreactivity (Masliah et al., 1998; Gervais et al., 1999), as well as appearance of activated caspase-3 reactivity (Chan et al., 1999). The work of Gervais (1999) showed that caspase-3 can cleave the amyloid precursor protein and cause an increase in secretion of Aβ, measured as picomolar quantities in cell media; cell death was not measured in that study. In our system, exogenous aggregated Aβ1–42 is added at a concentration of 10 μm, many fold higher than that produced by caspase-3 activation. Additionally, the Aβ produced by caspase-3 would most likely be in the less toxic soluble form over the time course of our experiments. Thus, blockade of caspase-3 activity would be expected to have little effect on cell survival in our model. In more chronic paradigms, caspase-3 may play a larger role in potentiating death by enhancing production of Aβ. Additionally, caspase-3 activation could play a role in proteolytic remodeling of the cytoskeleton and neuritic breakdown seen in these cells.

We found little evidence in our studies that free radicals play a key role in Aβ1–42-induced apoptosis in culture. The lack of protection by the nitric oxide synthase inhibitorl-NAME and the protection from death by SNAP argue against peroxynitrite mediation of apoptosis. The protection by SNAP supports the possibility that there is inhibition of caspase activity by nitrosylation, as has been seen in other models of cell death (Mannick et al., 1999). These findings do not preclude a contributory role for oxidative damage in Alzheimer's disease but argue against their role in these acute apoptotic models.

The protection by SNAP, the NO generator, from Aβ1–42 toxicity and the requirement for caspase-2 activity in this death pathway are elements shared with the death pathway for trophic factor deprivation, a pathway that also uses elements of the cell cycle. We have found that both hippocampal neurons and neuronal PC12 cells were protected by flavopiridol, a cell cycle inhibitor. This extends the recently published work showing protection of cortical neurons from Aβ1–40 death by inhibition of the cell cycle (Giovanni et al., 1999).

The caspase specificities for different cell death paradigms are presented schematically in Figure 7. By studying three paradigms in different neuronal cells, we can conclude that caspase specificity is determined by the death stimulus as opposed to the neuronal cell type. Although there are similarities between death induced by Aβ1–42 and by trophic factor deprivation, including protection by nitric oxide and by the cell cycle inhibitor flavopiridol and use of caspase-2 as a mediator of cell death, there are also differences. Most notable is the lack of protection against Aβ-induced death by NGF in PC12 cells and sympathetic neurons, as well as the susceptibility of sympathetic neurons from caspase-2 null mice to trophic factor deprivation (Bergeron et al., 1998). Therefore, the death pathways for these two stimuli are not identical.

Our data using caspase inhibitors, specific antisense oligonucleotides, and caspase-2 null mice implicate caspase-2 as a mediator of Aβ1–42-induced death. AD is both a devastating disease and an increasing health problem. The development of specific therapies that target caspase-2 may allow more effective treatment for AD.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (C.M.T., W.J.F., M.L.S.) and the Muscular Dystrophy Association (C.M.T.). We thank Christine Le for technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Carol M. Troy, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, Department of Pathology, 630 West 168th Street, New York, NY 10032. E-mail:cmt2@columbia.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad M, Srinivasula SM, Hegde R, Mukattash R, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Alnemri ES. Identification and characterization of murine caspase-14, a new member of the caspase family. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5201–5205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergeron L, Perez GI, Macdonald G, Shi L, Sun Y, Jurisicova A, Varmuza S, Latham KE, Flaws JA, Salter JC, Hara H, Moskowitz MA, Li E, Greenberg A, Tilly JL, Yuan J. Defects in regulation of apoptosis in caspase-2-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1304–1314. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan SL, Griffin WS, Mattson MP. Evidence for caspase-mediated cleavage of AMPA receptor subunits in neuronal apoptosis and Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci Res. 1999;57:315–323. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990801)57:3<315::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cotman CW, Su JH. Mechanisms of neuronal death in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol. 1996;6:493–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotman CW, Whittemore ER, Watt JA, Anderson AJ, Loo DT. Possible role of apoptosis in Alzheimer's disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994;747:36–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Azevedo WF, Jr, Mueller-Dieckmann HJ, Schulze-Gahmen U, Worland PJ, Sausville E, Kim SH. Structural basis for specificity and potency of a flavonoid inhibitor of human CDK2, a cell cycle kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2735–2740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estus S, Tucker HM, van Rooyen C, Wright S, Brigham EF, Wogulis M, Rydel RE. Aggregated amyloid-beta protein induces cortical neuronal apoptosis and concomitant “apoptotic” pattern of gene induction. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7736–7745. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07736.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farinelli SE, Park DS, Greene LA. Nitric oxide delays the death of trophic factor-deprived PC12 cells and sympathetic neurons by a cGMP-mediated mechanism. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2325–2334. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-07-02325.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farinelli SE, Greene LA, Friedman WJ. Neuroprotective actions of dipyridamole on cultured CNS neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5112–5123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05112.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreira A, Lu Q, Orecchio L, Kosik KS. Selective phosphorylation of adult tau isoforms in mature hippocampal neurons exposed to fibrillar A beta. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1997;9:220–234. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gervais FG, Xu D, Robertson GS, Vaillancourt JP, Zhu Y, Huang J, LeBlanc A, Smith D, Rigby M, Shearman MS, Clarke EE, Zheng H, Van Der Ploeg LH, Ruffolo SC, Thornberry NA, Xanthoudakis S, Zamboni RJ, Roy S, Nicholson DW. Involvement of caspases in proteolytic cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid-beta precursor protein and amyloidogenic A beta peptide formation. Cell. 1999;97:395–406. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80748-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giovanni A, Wirtz-Brugger F, Keramaris E, Slack R, Park DS. Involvement of cell cycle elements, cyclin-dependent kinases, pRb, and E2F.DP, in B-amyloid-induced neuronal death. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19011–19016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greene LA, Tischler AS. Establishment of a noradrenergic clonal line of rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cells which respond to nerve growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:2424–2428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.7.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greene LA, Cunningham ME, Farinelli SE, Park DS. Methodologies for the culture and experimental use of the PC12 rat pheochromocytoma line. In: Banker G, Goslin K, editors. Culturing nerve cells. MIT; Cambridge, MA: 1998. pp. 161–188. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo Q, Sebastian L, Sopher BL, Miller MW, Ware CB, Martin GM, Mattson MP. Increased vulnerability of hippocampal neurons from presenilin-1 mutant knock-in mice to amyloid beta-peptide toxicity: central roles of superoxide production and caspase activation. J Neurochem. 1999;72:1019–1029. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0721019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu S, Snipas SJ, Vincenz C, Salvesen G, Dixit VM. Caspase-14 is a novel developmentally regulated protease. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29648–29653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Humke EW, Ni J, Dixit VM. ERICE, a novel FLICE-activatable caspase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15702–15707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ii M, Sunamoto M, Ohnishi K, Ichimori Y. beta-Amyloid protein-dependent nitric oxide production from microglial cells and neurotoxicity. Brain Res. 1996;720:93–100. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jordan J, Galindo MF, Miller RJ. Role of calpain- and interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme-like proteases in the beta-amyloid-induced death of rat hippocampal neurons in culture. J Neurochem. 1997;68:1612–1621. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68041612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaur G, Stetler-Stevenson M, Sebers S, Worland P, Sedlacek H, Myers C, Czech J, Naik R, Sausville E. Growth inhibition with reversible cell cycle arrest of carcinoma cells by flavone L86–8275. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84:1736–1740. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.22.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keller JN, Kindy MS, Holtsberg FW, St. Clair DK, Yen HC, Germeyer A, Steiner SM, Bruce-Keller AJ, Hutchins JB, Mattson MP. Mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase prevents neural apoptosis and reduces ischemic brain injury: suppression of peroxynitrite production, lipid peroxidation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. J Neurosci. 1998;18:687–697. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00687.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruman I, Bruce-Keller AJ, Bredesen D, Waeg G, Mattson MP. Evidence that 4-hydroxynonenal mediates oxidative stress-induced neuronal apoptosis. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5089–5100. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05089.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li YP, Bushnell AF, Lee CM, Perlmutter LS, Wong SK. Beta-amyloid induces apoptosis in human-derived neurotypic SH-SY5Y cells. Brain Res. 1996;738:196–204. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00733-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Losiewicz MD, Carlson BA, Kaur G, Sausville EA, Worland PJ. Potent inhibition of CDC2 kinase activity by the flavonoid L86–8275. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;201:589–595. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mannick JB, Hausladen A, Liu L, Hess DT, Zeng M, Miao QX, Kane LS, Gow AJ, Stamler JS. Fas-induced caspase denitrosylation. Science. 1999;284:651–654. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5414.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masliah E, Mallory M, Alford M, Tanaka S, Hansen LA. Caspase dependent DNA fragmentation might be associated with excitotoxicity in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:1041–1052. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199811000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masters CL, Multhaup G, Simms G, Pottgiesser J, Martins RN, Beyreuther K. Neuronal origin of a cerebral amyloid: neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's disease contain the same protein as the amyloid of plaque cores and blood vessels. EMBO J. 1985;4:2757–2763. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04000.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mattson MP, Partin J, Begley JG. Amyloid beta-peptide induces apoptosis-related events in synapses and dendrites. Brain Res. 1998;807:167–176. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00763-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pike CJ, Walencewicz AJ, Glabe CG, Cotman CW. Aggregation-related toxicity of synthetic beta-amyloid protein in hippocampal cultures. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991a;207:367–368. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(91)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pike CJ, Walencewicz AJ, Glabe CG, Cotman CW. In vitro aging of beta-amyloid protein causes peptide aggregation and neurotoxicity. Brain Res. 1991b;563:311–314. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91553-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pike CJ, Ramezan-Arab N, Cotman CW. Beta-amyloid neurotoxicity in vitro: evidence of oxidative stress but not protection by antioxidants. J Neurochem. 1997;69:1601–1611. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69041601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selkoe DJ. Deciphering Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid precursor protein yields new clues. Science. 1990;248:1058–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.2111582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease: genotypes, phenotypes, and treatments. Science. 1997;275:630–631. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stefanis L, Park DS, Yan CY, Farinelli SE, Troy CM, Shelanski ML, Greene LA. Induction of CPP32-like activity in PC12 cells by withdrawal of trophic support. Dissociation from apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30663–30671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stefanis L, Troy CM, Qi H, Greene LA. Inhibitors of trypsin-like serine proteases inhibit processing of the caspase Nedd-2 and protect PC12 cells and sympathetic neurons from death evoked by withdrawal of trophic support. J Neurochem. 1997;69:1425–1437. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69041425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stefanis L, Troy CM, Qi H, Shelanski ML, Greene LA. Caspase-2 (Nedd-2) processing and death of trophic factor-deprived PC12 cells and sympathetic neurons occur independently of caspase-3 (CPP32)- like activity. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9204–9215. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-22-09204.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Talanian RV, Quinlan C, Trautz S, Hackett MC, Mankovich JA, Banach D, Ghayur T, Brady KD, Wong WW. Substrate specificities of caspase family proteases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9677–9682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thornberry NA, Lazebnik Y. Caspases: enemies within. Science. 1998;281:1312–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thornberry NA, Rano TA, Peterson EP, Rasper DM, Timkey T, Garcia-Calvo M, Houtzager VM, Nordstrom PA, Roy S, Vaillancourt JP, Chapman KT, Nicholson DW. A combinatorial approach defines specificities of members of the caspase family and granzyme B. Functional relationships established for key mediators of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17907–17911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Troy CM, Shelanski ML. Down-regulation of copper/zinc superoxide dismutase causes apoptotic death in PC12 neuronal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6384–6387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Troy CM, Derossi D, Prochiantz A, Greene LA, Shelanski ML. Downregulation of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase leads to cell death via the nitric oxide-peroxynitrite pathway. J Neurosci. 1996a;16:253–261. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00253.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Troy CM, Stefanis L, Prochiantz A, Greene LA, Shelanski ML. The contrasting roles of ICE family proteases and interleukin-1beta in apoptosis induced by trophic factor withdrawal and by copper/zinc superoxide dismutase down-regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996b;93:5635–5640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Troy CM, Stefanis L, Greene LA, Shelanski ML. Nedd2 is required for apoptosis after trophic factor withdrawal, but not superoxide dismutase (SOD1) downregulation, in sympathetic neurons and PC12 cells. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1911–1918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-06-01911.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vesely J, Havlicek L, Strnad M, Blow JJ, Donella-Deana A, Pinna L, Letham DS, Kato J, Detivaud L, Leclerc S, Mieijer L. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases by purine analogues. Eur J Biochem. 1994;224:771–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X, Zelenski NG, Yang J, Sakai J, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Cleavage of sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs) by CPP32 during apoptosis. EMBO J. 1996;15:1012–1020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yankner BA. Mechanisms of neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 1996;16:921–932. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]