Abstract

The single-channel properties of AMPA receptors can affect information processing in neurons by influencing the amplitude and kinetics of synaptic currents, yet little is known about the unitary properties of native AMPA receptors in situ. Using whole-cell and outside-out patch-clamp recordings from granule cells in acute cerebellar slices, we found that migrating granule cells begin to express AMPA receptors before they arrive in the internal granule cell layer and receive synaptic input. At saturating agonist concentrations, the open probability of channels in outside-out patches from migrating cells was very high, allowing us to identify patches that contained only one or two active channels. Analysis of the single-channel activity in these patches showed that individual AMPA receptors exhibit as many as four distinguishable conductance levels. The conductance levels observed varied substantially for different channels, although on average the values fell within the range of unitary conductances estimated previously for synaptic AMPA receptors. In contrast to patches from migrating granule cells, we rarely observed directly resolvable single-channel currents in patches excised from the somata of granule cells in the internal granular layer, even though these cells gave large AMPA receptor whole-cell currents. We did, however, detect AMPA receptors with apparent unitary conductances of <1 pS in patches from both migrating and mature granule cells. Our results suggest that granule cells express a heterogeneous population of AMPA receptors, a subset of which are segregated to postsynaptic sites after synaptogenesis.

Keywords: granule cell, cerebellum, AMPA receptor, glutamate, single channel, synaptic, extrasynaptic, development

Although AMPA receptors mediate EPSCs in most CNS neurons, the single-channel properties of these receptors have not been directly studied in neurons in situ. AMPA receptors are multimeric assemblies of the glutamate receptor (GluR) subunits GluR1–4, and their subunit composition and stoichiometry, as well as RNA editing and alternative splicing, influence several important channel properties (Hollmann and Heinemann, 1994; Bettler and Mulle, 1995; Dingledine et al., 1999). Because of the extensive array of potential AMPA receptor assemblies and neuron-to-neuron differences in subunit expression, it is not surprising that previous studies have found considerable variability in AMPA receptor phenotype (McBain and Dingledine, 1993; Yamada and Tang, 1993; Geiger et al., 1995; Fleck et al., 1996; Tóth and McBain, 1998).

Studies of recombinant AMPA receptors have shown that homomeric, as well as heteromeric, channels display multiple conductance levels whose amplitudes depend on subunit composition (Swanson et al., 1997;Rosenmund et al., 1998; Derkach et al., 1999). Multiple open levels in AMPA receptors were first observed in studies of cultured CNS neurons (Cull-Candy and Usowicz, 1987; Jahr and Stevens, 1987; Ascher and Nowak, 1988; Cull-Candy et al., 1988). However, previous single-channel studies of native AMPA receptors in cultured neurons have been performed at low agonist concentrations, and the consequently low open probability (popen) of the channels made the number of channels contributing to the record indeterminate. Therefore, it was uncertain to what extent the different open levels reflected conductance substates or the presence of different channel types.

Localization of synaptic AMPA receptors in situ at postsynaptic densities presents further barriers to studying channel properties directly. Thus information about the conductance of synaptic channels is limited to estimates obtained from nonstationary fluctuation analysis of synaptic currents. Recently, investigations of recombinant AMPA receptors demonstrated that the prevalence of sojourns in conductance substates varies with agonist concentration (Rosenmund et al., 1998). If native AMPA receptors show similar concentration-dependent behavior, this would further complicate comparisons of synaptic data with single-channel results obtained at low agonist concentrations in vitro, because the transient rise in glutamate concentration after transmitter release peaks at saturating levels (Clements et al., 1992; Clements, 1996; Diamond and Jahr, 1997).

In the present study, we have recorded currents through single AMPA receptors at saturating agonist concentrations, under conditions at which the high popen of the channels enabled us to identify patches containing at most two active channels. We have taken advantage of the postnatal development of the cerebellum to record AMPA receptor currents at two developmental stages: (1) during migration through the molecular layer (ML) before the neurons receive synaptic input and (2) after synaptogenesis in the internal granular layer (IGL). We found that AMPA receptors expressed by migrating cerebellar granule cells exhibit as many as four conductance levels, which showed extensive heterogeneity from channel to channel. On average, larger-conductance channels in outside-out patches had conductances similar to those estimated for synaptic AMPA receptors at the mossy fiber–granule cell synapse (Traynelis et al., 1993; Silver et al., 1996b).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Slice preparation and patch-clamp recordings. Mice of ages postnatal day 6 (P6)–P47 (C57-black-6; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were anesthetized with Metofane (Pitman-Moore) and decapitated, and the brains were removed in ice-cold oxygenated artificial CSF (ACSF). Parasagittal slices (150–200 μm thick) of cerebellum were cut with a vibratome. Slices were then incubated in ACSF at 37°C for 30–60 min and at room temperature (20–22°C) thereafter. ACSF contained (in mm): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 1.25 NaH2PO4H2O, 26 NaHCO3, 2 Na-pyruvate, 3 myo-inositol, and 0.5 ascorbic acid, pH 7.4, when oxygenated.

In the recording chamber, the slices were continuously perfused (∼1–2 ml min−1) with ACSF that contained the potassium channel blockers tetraethylammonium chloride (10 mm) and 4-aminopyridine (0.1 mm) and the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline methylchloride (20 μm). Currents through NMDA receptors were blocked by addition of either 100 μmd-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (d-APV) or 20 μmd-APV and 20 μm7-chlorokynurenic acid. All recordings were performed at room temperature. The pipette solution contained (in mm): 97.5 Cs-gluconate, 32.5 CsCl, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, and 2 lidocaine n-ethyl bromide (QX314; to block currents through sodium channels), pH 7.2. To replace the diffusional loss of intracellular polyamines, 100 μm spermine was included in the pipette solution. Patch pipettes (7–12 MΩ) were made from borosilicate glass, coated with Sylgard (Dow Corning), and fire-polished. Granule cells were identified by their location, appearance, and small capacitance (1–4 pF). The developmental stages of granule cells were determined visually on the basis of their positions within the slices.

In outside-out patch recordings, cyclothiazide (100 μm) was added to the external solutions from a dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) stock solution (final DMSO, 0.5%) to reduce AMPA receptor desensitization (Partin et al., 1993). In these experiments, patches were first equilibrated with ACSF containing cyclothiazide before switching to ACSF containing cyclothiazide and agonist. When activated in this manner, ensemble or single-channel currents typically reached steady-state levels within 3 sec of the start of the application. Cyclothiazide was not included when measuring whole-cell AMPA-type currents evoked by kainate.

Data acquisition and analysis. Whole-cell and single-channel currents were recorded using an EPC-9 patch-clamp amplifier. Data from whole-cell recordings were acquired and stored as described previously (Howe, 1996). To minimize distortion by resistance-capacitance (RC) filtering, whole-cell recordings were discontinued if the membrane time constant, τ = RC, exceeded 200 μsec. In most whole-cell recordings, τ was <100 μsec. For channels mediating whole-cell currents, estimates of maximalpopen were obtained from whole-cell currents by analyzing mean current versus variance plots as described in Smith et al. (1999).

Outside-out patch recordings were low-pass filtered at 10 kHz (−3 dB; four-pole Bessel type) and stored on videotape. The replayed signals were redigitized at 94 kHz and were additionally low-pass filtered with a digital Gaussian filter. For spectral density analysis of steady-state agonist-evoked ensemble currents in outside-out patches, the data were digitally low-pass filtered at 2 kHz (−3 dB) and compressed to a sampling rate of 9.4 kHz. Spectral density analysis was performed as described previously (Howe, 1996). Single-channel recordings were digitally low-pass filtered at 2 kHz (−3 dB) and compressed to final sampling rates of 31.3 or 47 kHz for inspection and display. All the digitized records were carefully inspected for artifacts and baseline drift before any quantitative analysis was performed. In most records, the baseline did not drift appreciably. In one patch, minor adjustments to the baseline were made as required. Single-channel analysis was only performed on outside-out patch recordings that were stable and quiet. The seal resistance of the patches (determined from the holding current at −100 mV) ranged from 70 to 770 GΩ (mean, 160 GΩ). The mean rms noise at −100 mV was 132 ± 3 fA (121–144 fA; 31.3 kHz sampling; 2 kHz low-pass filtering; eight patches).

As described below, two independent methods of single-channel analysis were used to measure the amplitudes of single-channel currents. Both methods also gave estimates of the proportion of time spent at the various open levels. We measured a mean reversal potential of 0.85 ± 2.0 mV (n = 9 cells) in whole-cell recordings of AMPA-type currents, so we used a reversal potential of 0 mV to calculate single-channel conductances.

Mean low-variance analysis. To measure the amplitudes of completely resolved single-channel openings, we used the mean low-variance method of Patlak (1988) using routines written with IgorPro software (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR) as described previously (Smith et al., 1999). The data were low-pass filtered at 2 kHz (−3 dB) and sampled at 31.3 kHz. The mean amplitude and variance of the closed-channel points (baseline) were calculated from a portion of record just before agonist application. The baseline was set to zero by subtracting the mean closed-channel current from all points, and the variance was calculated for a sliding window of 11 points corresponding to a duration of 350 μsec (2 filter rise times = 330 μsec at 2 kHz filtering). Open points were identified according to the criteria that the mean amplitude of the points in the window was >2 SDs of the baseline current and the variance of the points in the window was less than one-quarter of the baseline variance. These criteria reliably found events at least two filter rise times in duration. The low-variance open points were appended to the current trace, and the entire record was visually inspected. Open points that appeared to correspond to artifacts were deleted. The computer routine found low-variance points on either side of the baseline, and at −100 mV, outward low-variance points (which could not be AMPA receptor currents and were excluded from further analysis) always comprised <0.1% of the total low-variance open points found in the record.

Histograms of the low-variance open points were typically constructed using 75–100 bins, which were fitted with the sum of multiple Gaussian components using TAC software (Bruxton Corporation, Seattle, WA) to obtain mean currents for the multiple open levels in the records. Histograms of open points from longer portions of the record did not always show clear peaks; in such cases, we used the apparent open levels found during inspection of the data as initial values for the fit. All histograms were fitted with the minimum number of components required to give a good fit, with the restriction that the SD of each Gaussian component was no greater than twice the SD of the closed-channel current.

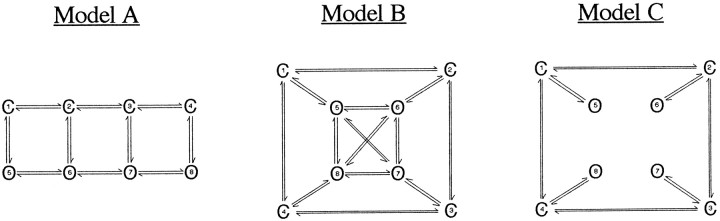

Hidden Markov analysis. To confirm our mean low-variance results, we also estimated open levels by hidden Markov analysis (Chung et al., 1990, 1991) using the Yale hidden Markov modeling (HMM) module of TAC software. Hidden Markov analysis models the behavior of ion channels by analyzing single-channel data with backward–forward and Baum–Welch algorithms to obtain a maximum likelihood estimate of the parameters of a discrete-time Markov model (Venkataramanan et al., 1999a,b, 2000). These parameters, whose initial values are set by the investigator, include the number of states, the current level of each state, the rate constants between states, and the initial state probabilities. We fitted 2–3 sec segments of steady-state highpopen channel activity with three classes of single-channel models: (1) models in which the open states were connected to each other in series (class A), (2) models in which each open state was connected to every other open state (class B), and (3) models in which direct transitions between open states were not allowed (class C). The models with four open states (indicated by O) are shown below. The corresponding versions of Model A with three and five open states were also tested. In some cases, versions of Model B with three and four open states were compared.

Models.

Model A is approximately based on the results of Rosenmund et al. (1998), who concluded that the different open levels observed in their single-channel recordings corresponded to differently liganded open states. These authors modeled the AMPA receptor as a tetramer that opened to increasingly larger conductance levels when two, three, or four agonist molecules were bound. Agonist-binding steps were not explicitly included in any of the models used here. However, within the context of the observations made by Rosenmund et al. (1998) and the high agonist concentrations used in this study (in which unliganded or singly-liganded species would be rare), the sequential open and closed states in Model A would correspond to differently liganded channel states, in which the binding and unbinding of agonist molecules could occur to and from both closed and open states. Within this same context, Model C only allows binding and unbinding to and from closed states, and Model B strictly implies that a channel can adopt different conductance levels with the same number of agonist molecules bound (which must be possible on thermodynamic grounds). Although these considerations guided our choice of models to evaluate, the results reported here are insufficient to decide whether the above interpretations are physically realistic.

The initial values for rate constants between connected states were set to 1000 sec−1. The initial values for the amplitudes of open levels were either those estimated from the fits to the mean low-variance open points (from the same data) or those estimated from inspection of the records. Open levels were assigned amplitudes in increasing order as indicated by the numbers in the models above. Hidden Markov analysis was performed at three different sampling rates (47, 23.5, and 11.75 kHz), and the data were low-pass filtered at 40% of the sampling rate (18.8, 9.4, and 4.7 kHz, respectively) by the sharp-cutoff inverse filter function of TAC (Venkataramanan et al., 2000). For our records, we found that different sampling and filtering rates did not appreciably affect the number or amplitude of the open levels. Different models were compared at the same sampling rate and low-pass filtering. When evaluating fits obtained with different models, the fit was deemed significantly improved if the log likelihood of the model with more parameters improved by 10 n log units, where n was the number of additional nonzero parameters. Rate constants initially set to zero could not be altered by the fitting procedure, but parameters assigned initial nonzero values were unconstrained. If the fit converged and any of the rate constants were very small (i.e., approaching zero), the states were considered disconnected; likewise, current levels were considered superfluous if they differed from the baseline, or another open level, by <2 SDs of the closed-channel current (at 2 kHz filtering). Similarly, states with mean open times close to the sampling interval were considered unnecessary.

Determining whether one or more channels were active in an outside-out patch. To test whether our presumed single-channel records indeed represented the activity of only one AMPA receptor, we compared the observed current levels in the record with those predicted from the binomial distribution if the observed channel activity were caused by several smaller channels instead of one channel with multiple open levels. An all-points histogram of the observed steady-state channel activity in an outside-out patch was plotted and fitted with one Gaussian component for the closed points and one Gaussian component for each of the open levels. From the multiple Gaussian fit to the results, the relative area of the Gaussian component corresponding to the closed points was used to calculate the open probability of an individual channel if the record arose from N identical channels (where N corresponds to the number of observed open levels). The popen was defined as:

This estimate of the popen of the hypothetical individual channels was used to calculate the probability P of finding j channels simultaneously open at a given time using the binomial relationship:

Results are given as the mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

We observed previously that cerebellar granule cells begin to express functional AMPA receptors at approximately the time they leave the external germinal layer (EGL) in approximately the first postnatal week (Smith et al., 1999). After proliferating in the EGL, granule cells migrate inward through the ML and Purkinje cell layer, toward their final destination in the IGL. After they reach the IGL, granule cells receive glutamatergic synaptic input from mossy fibers (Altman, 1972a,b). By the end of the second postnatal week, most granule cells have arrived in the IGL (Altman, 1972b). Although granule cells can receive synaptic input soon after entering the IGL, mossy fiber synapses do not mature until approximately P40–P60 (Hámori and Somogyi, 1983; Mason and Gregory, 1984; Wall and Usowicz, 1999). To investigate the expression and single-channel properties of native AMPA receptors, we used patch-clamp techniques to record agonist-evoked whole-cell and single-channel currents through AMPA receptors in granule cells in situ at different stages of postnatal development.

Granule cells express functional AMPA receptors before synaptogenesis

Whole-cell currents from granule cells in the EGL, ML, and IGL were evoked by bath application of kainate, an agonist that produces sustained currents through AMPA-type channels because of incomplete receptor desensitization [Patneau et al. (1993) and references therein]. The slow solution exchange ensured that the whole-cell currents were not contaminated by currents through kainate-type glutamate receptors, which quickly enter and slowly recover from desensitization when activated by kainate (Huettner, 1990; Herb et al., 1992; Lerma et al., 1993). Concentration–response data obtained under these conditions gave a mean EC50 value for kainate of 78 ± 10 μm (n = 5 cells, with at least 4 concentrations each). The mean EC50 value obtained here, similar to previous values obtained for kainate activation of AMPA receptors (Huettner, 1990; Patneau and Mayer, 1990; Traynelis and Cull-Candy, 1991), is ∼10-fold larger than the corresponding value obtained for kainate-type channels expressed by granule cells in situ[EC50 for kainate, 8 μm(Smith et al., 1999)]. Applications of 10 μmkainate, a concentration that elicits substantial kainate-type currents in granule cells if kainate receptor desensitization is reduced (Pemberton et al., 1998; Smith et al., 1999), did not evoke significant whole-cell currents in this study. Taken together, these results support the conclusion that the kainate-evoked currents recorded here are through AMPA-type channels.

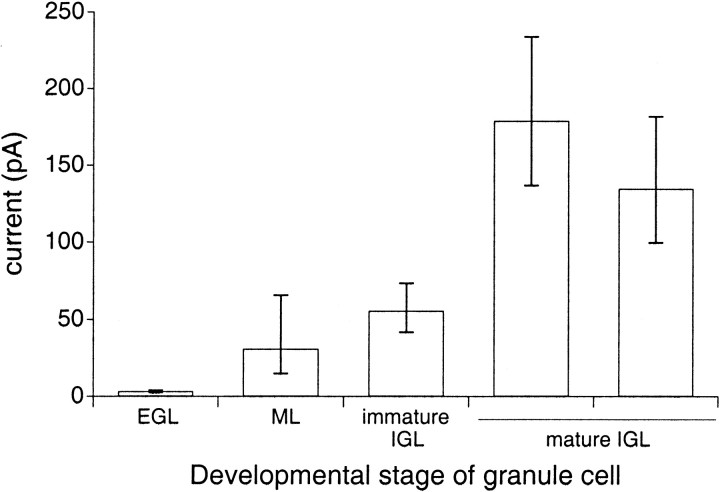

In agreement with our previous results (Smith et al., 1999), we found that proliferating granule cells in the outer layers of the EGL do not express significant AMPA-type whole-cell currents in response to saturating concentrations of kainate (Fig.1; 300–600 μm). However, kainate did elicit currents through AMPA receptors from granule cells in the ML and the IGL. As shown in Figure 1, the average amplitude of the steady-state whole-cell currents increased with the developmental stage of the neuron, indicating that the expression of functional AMPA receptors increases as granule cells migrate toward the IGL. In addition, the average amplitude of whole-cell AMPA-type currents continued to increase even after granule cells arrived in the IGL, as evidenced by the larger amplitudes of whole-cell currents evoked from mature IGL cells (>P40) compared with those evoked from immature IGL cells (P6–P22). In mature IGL cells, even currents evoked by a submaximal concentration of kainate (100 μm) were larger than those evoked by saturating concentrations of kainate in immature IGL cells.

Fig. 1.

Whole-cell currents through AMPA receptors increase as cerebellar granule cells mature. The first fourbars (left to right) denote mean currents evoked by saturating concentrations of kainate (300–600 μm) in EGL, ML, immature IGL, and mature IGL cells, respectively; the last bar on theright is the mean current evoked in mature IGL cells by 100 μm kainate. Inspection of all the data indicated that the steady-state current amplitudes were log-normally distributed. The logarithms of the individual current amplitudes were used to calculate the mean and SEM for each sample population. The figure shows the antilogs of the values (mean ± SEM) obtained from the log-normal distributions: EGL, 2.3 pA (n = 9 cells); ML, 27.5 pA (n = 5 cells); immature IGL (<P40), 57.5 pA (n = 9 cells); mature IGL (>P40), 178 pA (n = 3 cells); and mature IGL (100 μmkainate), 135 pA (n = 5 cells). There were no significant differences in whole-cell capacitance between the granule cells in the different groups.

Detectable AMPA receptor single-channel activity in outside-out patches from migrating granule cells

To study the properties of the channels underlying the AMPA-type whole-cell currents, we pulled outside-out patches from granule cells migrating through the ML and bath-applied saturating concentrations of kainate (1 mm) or glutamate (2 mm). Both agonists were applied in the presence of 100 μmcyclothiazide to reduce AMPA receptor desensitization (Partin et al., 1993). We observed currents through AMPA receptors evoked by glutamate in 28 of 31 outside-out patches from granule cells in the ML. Some patches appeared to contain many channels, giving ensemble currents of up to 40 pA, but it was not uncommon for patches to show only one or two active channels.

Although our whole-cell recordings indicated that kainate-type currents were minimal or absent under these experimental conditions (see above), the whole-cell results do not exclude the possibility that kainate receptors could have contributed to the observed single-channel activity during occasional escapes from desensitization. We believe, however, that our single-channel records were not contaminated with kainate receptor activity. First, although single-channel currents through kainate-type channels can be observed in patches from EGL granule cells, the very small conductances of the kainate receptors expressed in granule cells make detection of discrete single-channel currents unlikely at the developmental stages studied here (Smith et al., 1999). Second, the characteristics of kainate receptor single-channel activity observed in patches from granule cells are quite different from the single-channel activity described here (T. C. Smith and J. R. Howe, unpublished observations) (Smith et al., 1999). For example, in the present study, saturating concentrations of both kainate and glutamate evoked single-channel activity with a very high popen, whereas kainate receptors expressed by EGL granule cells show a much lower popen, even when high agonist concentrations are applied after reducing desensitization with concanavalin A. Finally, the concentration dependence of the channel activity we observed in the present work was entirely consistent with our concentration–response data for AMPA-type whole-cell currents.

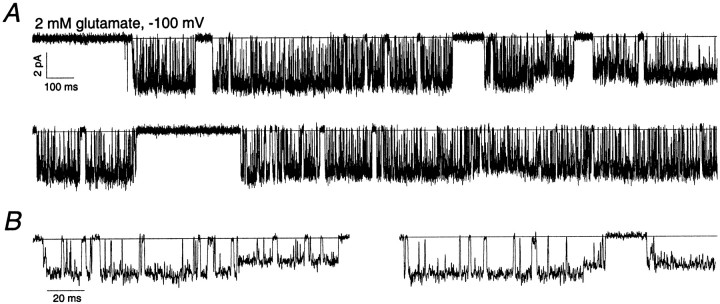

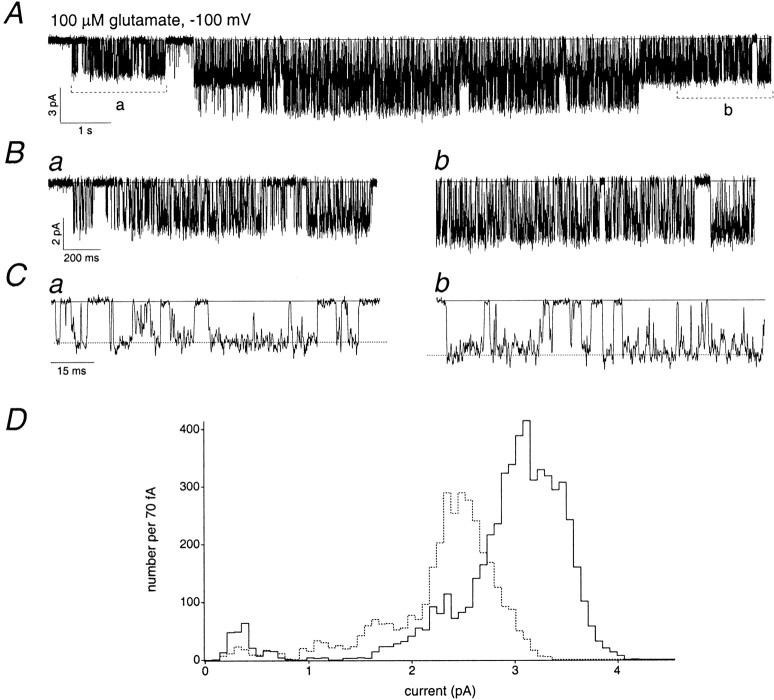

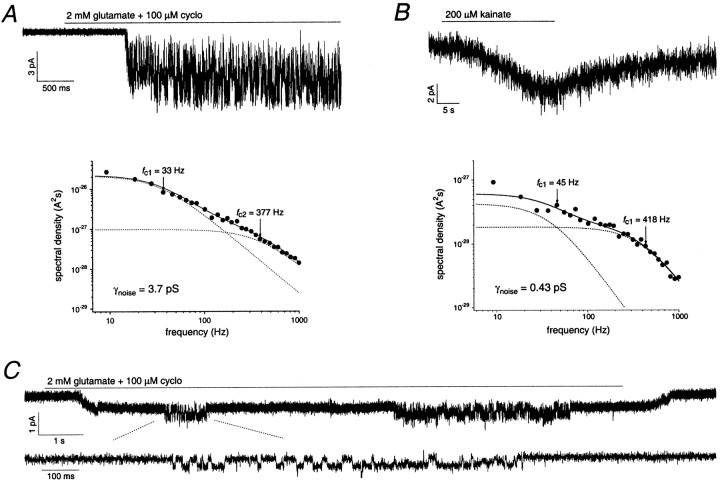

There were several characteristics common to the single-channel activity of the AMPA receptors that we studied in ML patches. At high agonist concentrations, all the channels displayed periods of highpopen activity that lasted hundreds of milliseconds or even seconds (Fig.2A). These highpopen periods are reminiscent of the high popen activity seen with NMDA-type glutamate receptors (Jahr and Stevens, 1987; Howe et al., 1988, 1991). For NMDA receptors, however, this highpopen activity is also observed at low agonist concentrations (Gibb and Colquhoun, 1992), whereas that was not the case for the AMPA-type channels studied here. In this regard, the high popen periods displayed by AMPA receptors are more similar to the activity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, which, at high agonist concentrations, display highpopen periods thought to reflect escapes from desensitized states (Sakmann et al., 1980; Colquhoun and Ogden, 1988). High popen AMPA receptor activity was interrupted by silent periods, which themselves could be hundreds of milliseconds long (Fig. 2A) and which likely resulted from entry into desensitized states. (Although 100 μm cyclothiazide was present, it slows, rather than removes, desensitization.) In support of this view, preliminary results suggest that the duration of the long closed periods increases in the absence of cyclothiazide, although highpopen periods evoked by kainate remain.

Fig. 2.

Single-channel activity of an AMPA receptor expressed by a migrating granule cell. Holding potential, −100 mV.A, Steady-state activity of an AMPA receptor in an outside-out patch from a granule cell in the ML. Glutamate (2 mm) and cyclothiazide (100 μm) were present throughout the recording. The zero current level is indicated by thesolidhorizontallines. Data were sampled at 31.3 kHz and low-pass filtered at 2 kHz (−3 dB). B, Portions of the single-channel recording shown in the toptrace of A on a faster time scale.

The high popen behavior of the channels allowed us to identify patches that appeared to contain only one or two active channels. Almost all the channels (11 of 13) in these patches visited more than one conductance level, the only exceptions being channels with very small single-channel currents. Examples of transitions to conductance sublevels are shown in Figure2B. Although almost all the data presented in this study were obtained at saturating agonist concentrations, we also recorded single-channel currents over a range of concentrations. Channels showing multiple open levels spent more of their open time in larger sublevels as the agonist concentration was increased, as reported previously for recombinant AMPA receptors (Rosenmund et al., 1998). Although this was an obvious feature of all our recordings, to quantify the results at low agonist concentrations in patches containing two channels is difficult because the lowpopen made the assignment of openings to a particular channel uncertain. However, we did obtain results in three one-channel patches over a wide range of glutamate concentrations. On average, the proportion of open time spent at the largest open level increased from 6 ± 3% at 20 μm glutamate to 28 ± 7% at 100–200 μm glutamate and 82 ± 7% at 2 mm glutamate.

Native AMPA receptors show up to four conductance sublevels

We limited our single-channel analysis to patches that appeared to contain only one or two active channels, as determined from analysis of the high popen behavior at 2 mm glutamate (with 100 μmcyclothiazide). In patches that appeared to contain two channels, there were often portions of the record in which only one channel was active, due to entry into long-lived closed or desensitized states. Several consistent characteristics of the records indicate that the multiple current levels that we observed are in fact conductance substates of single AMPA receptors, rather than currents through several smaller channels. First, there were apparently direct transitions between nonadjacent open levels. Second, for some channels, the open levels observed were clearly not multiples of each other, as would be expected if different open levels corresponded to the simultaneous opening of more than one channel. Third, the highpopen periods contained many brief closings that appeared to be direct transitions from and to the largest open level. Finally, as noted above, the highpopen periods were interrupted by shut periods that lasted up to hundreds of milliseconds. Given the long duration and relative infrequence of these shut periods, it is highly unlikely that two or more independently gating channels would give rise to these shut periods by opening and closing simultaneously. Therefore, if multiple channels contributed to the record, one would expect these long-lived closed periods to be bordered by periods in which only smaller current levels were observed. This was clearly not the case (see Fig. 2).

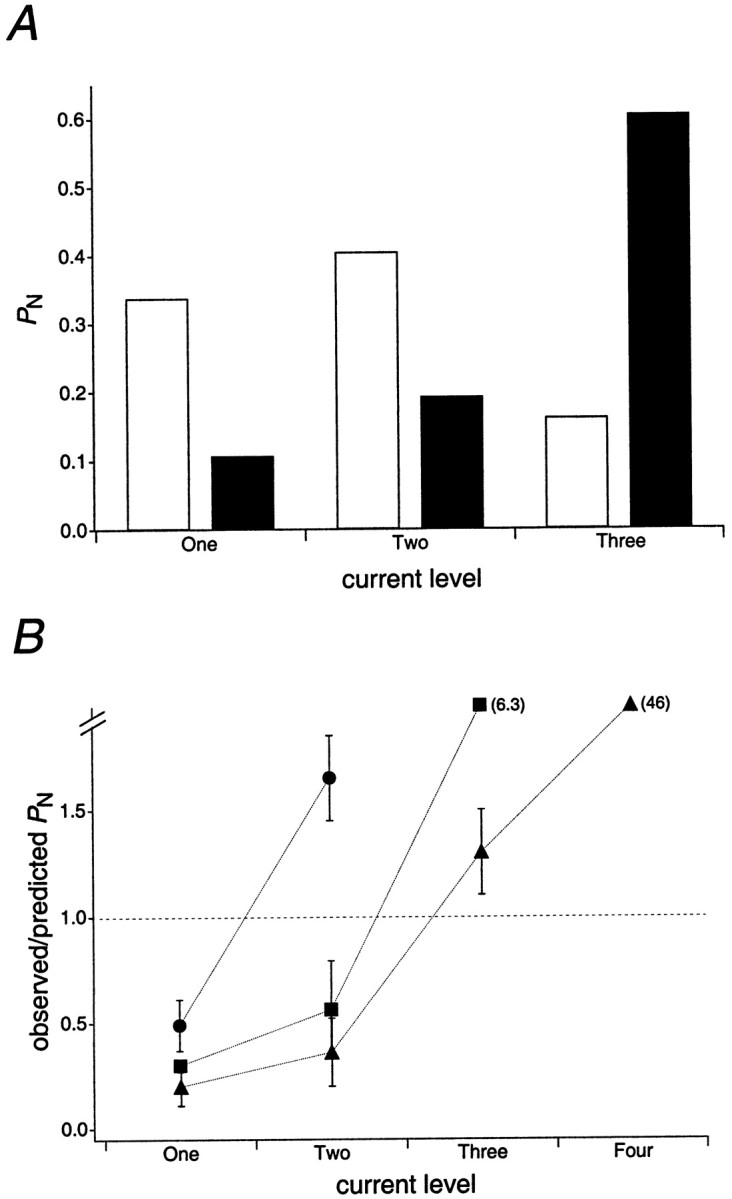

Although most of the larger-conductance channels that we studied displayed open levels that were not multiples of each other, the closely spaced open levels observed for smaller-conductance channels often appeared to be. To evaluate further the likelihood that the channel activity observed arose from multiple channels, we compared the observed proportion of time spent at each open level with the proportions predicted from the binomial distribution if the activity arose from multiple channels gating independently. For example, how likely was it that a patch appearing to contain only one active AMPA receptor with open levels of 3, 5, and 7 pS actually contained three identical channels of 2–3 pS? In Figure3A, the filled bars illustrate the relative time one such channel spent at each open level at 2 mm glutamate; theopen bars represent the predicted probabilities of observing one, two, or three independent channels open simultaneously (calculated as described in Materials and Methods). Clearly the results deviate from those predicted from the binomial distribution. A similar analysis was performed for eight different channels, and in each case the predicted proportion of time spent at each current level differed substantially from the proportions observed experimentally. We also calculated how much the area under the closed-points component (see Materials and Methods) would have to differ from its fitted area to give hypotheticalpopen values consistent with the observed results if the activity arose from multiple channels. In each case this difference exceeded 80% of the measured area of the closed-points component, which far exceeded the uncertainty of the measurements.

Fig. 3.

The observed current levels in outside-out patch recordings are inconsistent with the activity of multiple channels.A, Analysis of data from a putative one-channel recording. The filledbars indicate the proportion of time at each open level (PN) observed during steady-state activity evoked by 2 mm glutamate (with cyclothiazide). The openbars indicate the proportion of time at each current level predicted from the binomial distribution (described in Materials and Methods) if the currents in the record arose from the activity of three independently gating channels. B, Mean ratios (± SEM) of the observedPN to thePN predicted from the binomial distribution (if the activity arose from multiple independently gating channels). The results are from eight records in which two (circles), three (squares), or four (triangles) open levels were evident (n = 2, 3, and 3 individual channels, respectively). Note that the y-axis is discontinuous. For points off the scale, the mean ratios are given inparentheses.

The mean results from this analysis of eight individual AMPA receptors are summarized in Figure 3B, which shows the average ratio of the observed proportion of time the record spent at a particular current level to the proportion predicted if the current levels arose from multiple channels. Because the predictions differ quite strikingly from the observed data, we believe that our presumed single-channel records are indeed likely to contain only one active channel, even when the larger open levels appear to be multiples of the smallest.

Granule cells express AMPA receptors with heterogeneous conductance levels

Although almost all the AMPA receptors that we studied in patches showed multiple open levels at saturating concentrations of agonist, there was considerable channel-to-channel variability in the amplitudes of the conductance sublevels, as well as in the number of levels detected. The single-channel currents through 13 channels were measured during activity evoked by 2 mm glutamate. Single-channel currents evoked by 1 mm kainate were also measured for 3 channels. Interestingly, although agonist-dependent differences in the apparent unitary conductance of AMPA-type channels have been found using fluctuation analysis (for example, see Jonas and Sakmann, 1992;Wyllie et al., 1993; Swanson et al., 1997), the conductance levels observed with kainate and glutamate did not differ significantly for any of the channels studied here.

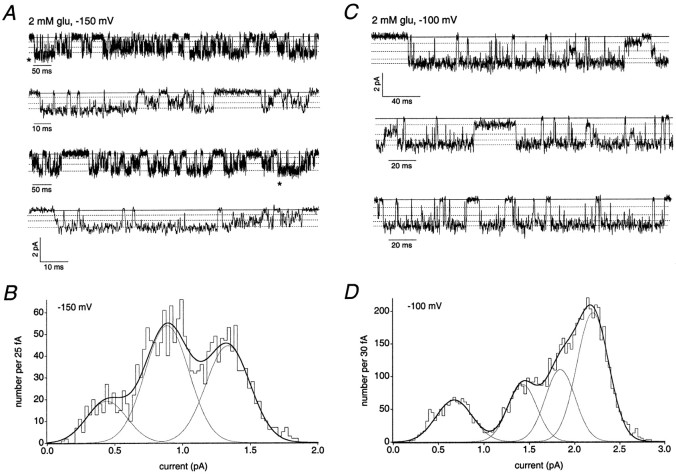

Figure 4 illustrates examples of data from a smaller AMPA receptor (Fig.4A,B) and a larger AMPA receptor (Fig. 4C, D) in outside-out patches from two different ML cells. Three small, closely spaced, open levels were detected for the AMPA receptor shown in Figure 4A. In Figure 4A the dotted lines show the currents for each open level superposed on examples of the activity of this channel. The three peaks in the histogram of low-variance open points (from a selected portion of the record) correspond to conductances of 3, 6, and 9 pS (Fig. 4B). The larger-conductance AMPA receptor in Figure 4C visited four detectable open levels. At 2 mm glutamate the channel spent most of its time at the largest conductance level (22 pS), but examples of long-lived sojourns at the two smallest levels (7 and 14 pS) were also evident. In addition, the record contained openings to a level with a mean conductance of 18 pS, most of which were short-lived. A histogram of low-variance open points obtained from this channel is shown in Figure 4D, with the four Gaussian fit to the results superposed.

Fig. 4.

AMPA receptors expressed by migrating granule cells show heterogeneity in the number and amplitudes of their conductance sublevels. The zero current levels are indicated bysolidlines. Open levels are indicated bydottedlines. Channel currents were activated by 2 mm glutamate in the presence of 100 μm cyclothiazide. A, Outside-out patch recording from a granule cell in the ML. Holding potential, −150 mV. The second and fourthtraces from the top are expanded portions of the first and thirdtraces, respectively, the beginning of which are indicated by asterisks. Data were sampled at 47 kHz and low-pass filtered at 2 kHz (−3 dB). B, Histogram of mean low-variance open points from the channel recording shown inA. The histogram was fitted with the sum of three Gaussian components, giving mean conductance levels of 3, 6, and 9 pS (thinlines, individual Gaussian components; thickline, sum of individual components). C, Outside-out patch recording from a granule cell in the ML. Holding potential, −100 mV. Data were sampled at 31.3 kHz and low-pass filtered at 2 kHz (−3 dB). D, Histogram of mean low-variance open points from the channel recording shown in C. The histogram was fitted with the sum of four Gaussian components, giving mean conductance levels of 7, 14, 18, and 22 pS (thinlines, individual Gaussian components; thickline, sum of individual components).

Some of the patch-to-patch variability in conductance levels may reflect differences in the repertoire of AMPA receptors expressed by different granule cells. It was clear, however, that individual cells expressed multiple types of AMPA receptors. In each patch that contained two active channels, the two channels showed distinguishably different conductance levels. An example of results from a patch that contained two channels is illustrated in Figure5. At the beginning of the trace, only the relatively smaller channel is active. In the middle of the trace, both channels are active. Near the end of the trace in Figure 5A, the smaller channel is silent, leaving only the activity of the larger channel. Figure 5, B and C (traces taken from the beginning and end of the trace in Fig. 5A), illustrates that the channel in Figure 5Ba has a smaller single-channel conductance than does the one in Figure 5Bb. This is also evident when histograms of low-variance open points are overlaid (Fig. 5D; histograms were constructed from portions of the trace where only one channel was active).

Fig. 5.

Two AMPA receptors with different single-channel conductances in the same outside-out patch. Holding potential, −100 mV. Data were sampled at 31.3 kHz and low-pass filtered at 2 kHz (−3 dB). A, Outside-out patch recording from a granule cell in the ML. Note that two channels are active simultaneously in the middle of the recording.Ba, Portion from the beginning of the recording inA on a faster time scale, where only the smaller channel is active. b, Portion near the end of the recording inA on a faster time scale, where only the larger channel is active. Ca,b, Portions of records inB on a faster time scale to show the difference in the largest conductance levels (dottedhorizontallines). D, Overlaid histograms of low-variance open points from each channel. Theshaded histogram is derived from the activity of the smaller channel in Ba. The unshadedhistogram is derived from the activity of the larger channel inBb.

We used two independent methods of single-channel analysis to estimate the open levels of 13 individual AMPA receptors in eight outside-out patches. Consideration of all the records indicated that 2–3 pS was the minimum separation from baseline, and between levels, that we could resolve (see Materials and Methods). At holding potentials of −100 to −150 mV, this corresponded to approximately twice the SD of the closed-channel current. We measured the open levels of most channels using mean low-variance analysis. For three channels, however, the rapid kinetics of the channel behavior made detection of open levels with mean low-variance analysis unreliable (for example, compare the kinetic characteristics of the channels shown in Figs. 4Cand 5). The three channels exhibiting rapid kinetics were those with the largest conductance levels; although it is possible that there is a correlation between channel conductance and gating kinetics, this apparent difference may reflect the better signal-to-noise ratio for the larger-conductance channels. To estimate the open levels of channels with rapid kinetics, we used HMM techniques as described in Materials and Methods.

We first used HMM to verify the amplitudes of open levels that we measured by mean low-variance analysis. The open levels estimated with HMM at three different filter settings (18.8, 9.4, and 4.7 kHz) were similar, and they agreed well with the values obtained from fits to the mean low-variance open points (data low-pass filtered at 2 kHz). The levels obtained with HMM and mean low-variance analysis were usually identical and, on average, agreed within 1 pS. The observation that the amplitudes of the open levels were relatively insensitive to low-pass filtering implies that the open levels detected are unlikely to reflect incompletely resolved transitions between different channel states. We then used HMM to estimate the open levels of channels not amenable to mean low-variance analysis because of their rapid kinetics. Although HMM is in principle able to detect very small signals, only levels above our resolution at 2 kHz filtering are depicted in Figure6.

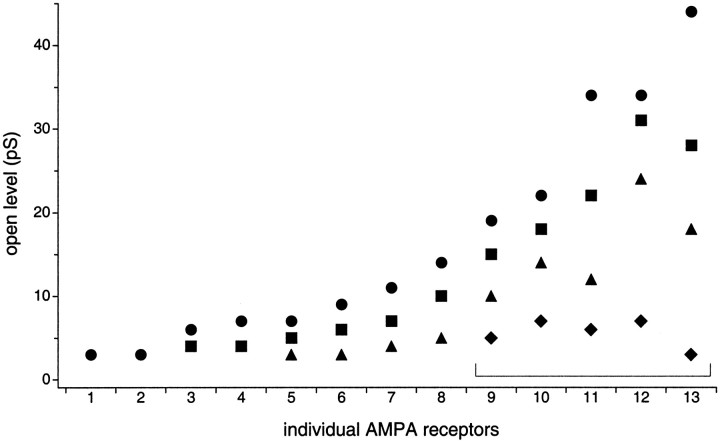

Fig. 6.

Heterogeneous open levels of AMPA receptors expressed by granule cells in situ. Amplitudes of the open levels (in picosiemens) of 13 individual AMPA receptors observed in outside-out patch recordings (circles,squares, triangles, anddiamonds show levels in order of decreasing amplitude). Current levels were measured at −100 mV (or −150 mV for channel 6) using mean low-variance analysis and/or hidden Markov analysis and converted to conductances using a reversal potential of 0 mV. Channels 11–13 showed rapid kinetics and were analyzed exclusively with hidden Markov modeling. Channels are plotted in order of increasing amplitude of the largest open level. For each channel where four open levels were detected (channels 9–13, brackets), HMM fits with four open states were significantly better than fits with three open states.

Figure 6 summarizes the number and amplitudes of open levels we observed from the single-channel activity of 13 individual AMPA receptors. These channels exhibited from one to four detectable open levels that ranged in conductance from 3 to 44 pS. Interestingly, there is a correlation between the number of open levels detected and their amplitudes. It is possible that the smaller-conductance channels have additional open levels that are too small or too brief to detect. Alternatively, AMPA receptors may truly differ in the number of their open states.

In addition to providing another method to measure channel open levels, HMM allowed a quantitative assessment of the number and connectivity of open levels that best described the data. For the five largest conductance channels (Fig. 6, bracketed channels 9–13), HMM analysis showed that Model A with four open states (in order of increasing conductance) gave significantly better fits to the single-channel records than did analogous models having three open states. In addition, versions with five open states did not significantly improve the fit to the data. For three of five channels, models that allowed direct transitions between all open levels (Model B) gave better fits to the data than did Model A. For each channel, the worst fits were obtained using Model C, which disallowed direct transitions between open states. The results of the above comparisons are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of hidden Markov comparisons for larger-conductance AMPA receptors

| Increase in parameters | Change in log likelihood | Change in log likelihood per additional parameter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparisons for Model A | |||

| 4 open > 3 open | 7 | 144 ± 63 | 21 ± 9 |

| Comparisons of 4 open-state models | |||

| Model B > Model A | 8 | 202 ± 59 | 25 ± 7 |

| Model B > Model C | 4 | 1502 ± 632 | 375 ± 158 |

| Model A > Model C | 4 | 1341 ± 567 | 335 ± 142 |

Results of comparing fits to the same data with different Markov models for five individual larger-conductance AMPA receptors (Fig. 6, channels 9–13). For each comparison, the table shows the increase in the number of parameters (additional rate constants and open levels) for the more complicated model, the total change in log likelihood units, and the change in log likelihood per additional parameter. An increase per additional parameter of >10 log likelihood units was considered significant. For Model A, inclusion of a fifth open state did not result in significantly better fits to the data.

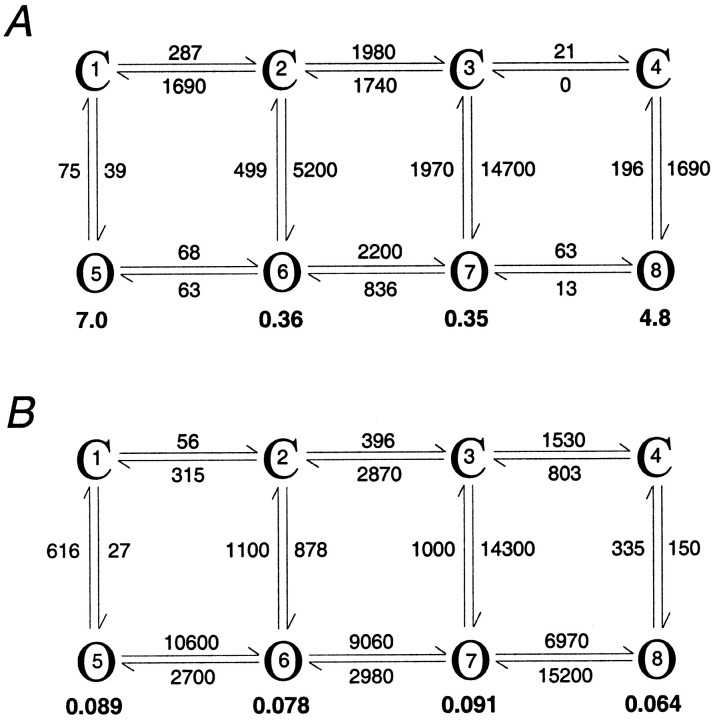

The HMM analysis also confirmed our impression that different channels showed different kinetic behavior. Figure7 shows the rate constants and mean open times obtained from fitting the four-open-state version of Model A to the activity of two different AMPA receptors (sampled at 23.5 kHz; filtered at 9.4 kHz). The mean open times for the channel with the relatively faster kinetics (Fig. 7B) are much briefer than the window duration used for mean low-variance analysis (330 μsec), and at 2 kHz low-pass filtering the record consisted primarily of incompletely resolved events. Although Model B usually gave better fits than Model A, the open times obtained with the two types of models were very similar for each channel analyzed. Thus although the connectivity of the states is somewhat unresolved, we believe that the mean open times estimated with HMM are good approximations of channel dwell times.

Fig. 7.

Rate constants obtained from hidden Markov modeling for two channels in different ML patches. The mean dwell times (in milliseconds) are shown for the four open states (states 5–8) in boldtype. Rate constants >1000 sec−1 were rounded to three significant figures. A, The channel that gave these results is the channel illustrated in Figure 4C. This channel displayed relatively long-lived sojourns in the various open levels. Both HMM and mean low-variance analysis gave conductance levels of 7, 14, 18, and 22 pS (states 5–8, respectively).B, The channel that gave these results is illustrated in Figure 5, Ba and Ca. The rapid kinetics of this channel made estimates of the open levels from mean low-variance analysis unreliable. The conductances obtained from HMM analysis were 6, 15, 22, and 34 pS (states 5–8, respectively). The mean open times estimated for this channel were all <100 μsec.

Rectification behavior of AMPA receptors in granule cellsin situ

One possible explanation for the heterogeneity we observed in single-channel conductances is that the channels in ML patches differ in subunit composition. Inclusion of the edited GluR2 subunit in coexpression experiments reduces the single-channel conductance of GluR4 channels (Swanson et al., 1997). In addition, the relative abundance of GluR2 has been demonstrated to affect sensitivity to block by internal polyamines (Washburn et al., 1997). Therefore, because of the observed variability in conductances, we asked whether native AMPA receptors in granule cells might also exhibit heterogeneity in their rectification properties.

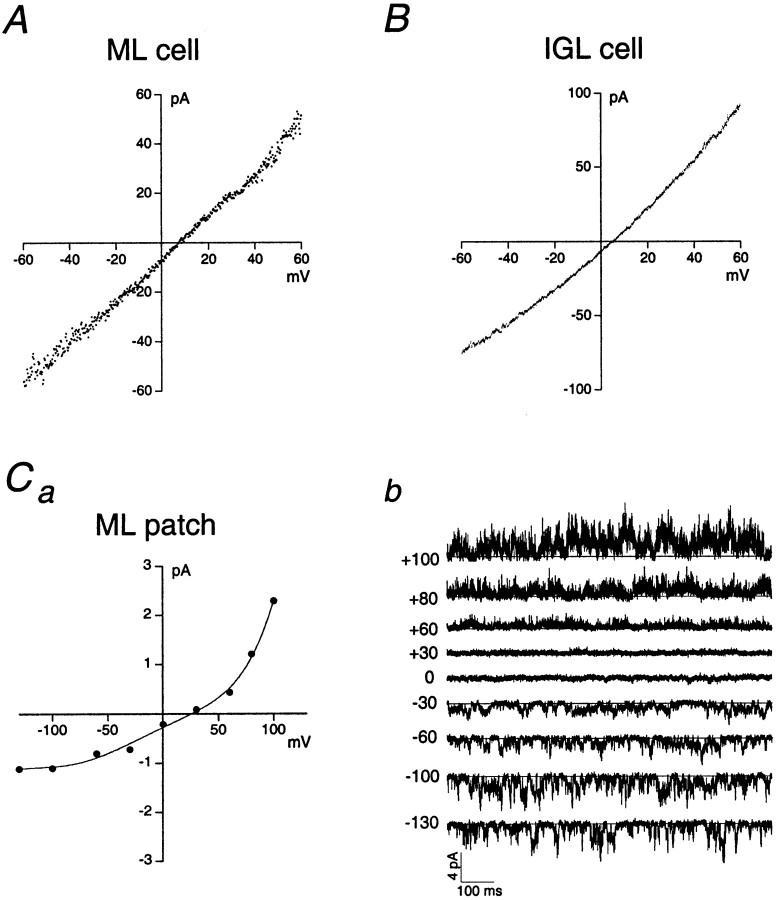

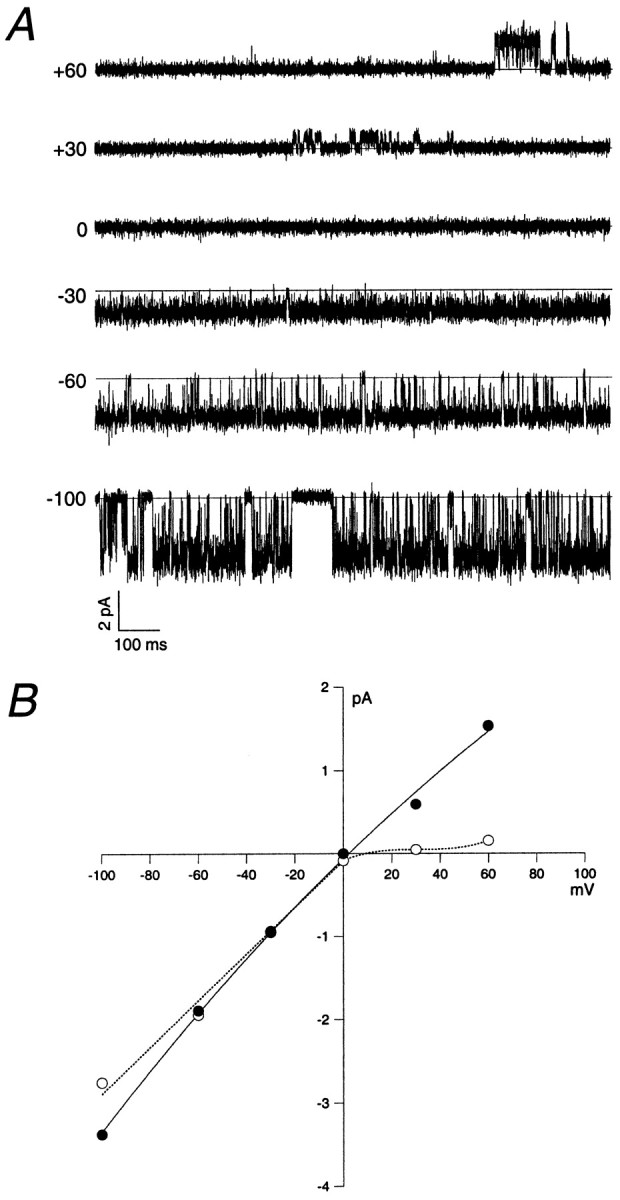

We first asked whether granule cells show significant cell-to-cell variability in the average rectification behavior of AMPA receptors, as has been shown for granule cells in culture (Kamboj et al., 1995). In contrast to previous in vitro results, we found that AMPA-type whole-cell currents evoked by glutamate or kainate consistently showed linear or outwardly rectifying I–Vrelations in both ML and IGL cells (Fig.8A,B; ML, n = 4 cells; IGL, n = 5 cells).

Fig. 8.

Whole-cell currents through AMPA receptors in granule cells show linear or outwardly rectifying current–voltage relations, as do some ensemble patch currents. A, B, Whole-cell I–V curves from a granule cell in the ML (A) and the IGL (B).C, I–V curve (a) and ensemble currents (b) from an outside-out patch excised from a granule cell in the ML. Several channels were active in this patch. Holding potentials (in millivolts) are indicated to the left of the traces inb. Data were sampled at 31.3 kHz and low-pass filtered at 2 kHz (−3 dB).

In contrast to the whole-cell results, agonist-evoked ensemble currents in outside-out patches from migrating granule cells showed both inward and outward rectification, suggesting that these patches contained different subsets of AMPA receptors. In four patches, we observed linear or outwardly rectifying I–V relations (Fig.8C), whereas three other patches showed inward rectification. These results suggest that the linearI–V relations of whole-cell currents may reflect the average behavior of a heterogeneous population of AMPA receptors, rather than reflecting the rectification behavior of a single type of AMPA receptor.

The heterogeneous rectification behavior of AMPA receptors was also evident in single-channel recordings. Some channels exhibited rectification behavior similar to that in the multichannel patch shown in Figure 8C, which passed outward currents at positive potentials, whereas others showed some flickery channel block, as if the channels might be weakly blocked by internal polyamines. Still other channels, such as the one illustrated in Figure9, appeared to be more strongly blocked by internal polyamines, exhibiting a marked decrease inpopen at positive potentials. This channel showed long silent periods at positive potentials that were occasionally interrupted by shorter periods of activity in which little or no flickery channel block was evident (Fig. 9A,top two traces). Interestingly, the single-channel I–V curve exhibited only slight inward rectification (Fig. 9B, filled circles), whereas the mean current measured for representative portions of the record at each potential showed strong inward rectification (open circles). Comparison of the two I–V curves in Figure 9B demonstrates that the rectification behavior of this channel is manifest primarily as a dramatic reduction in popen at positive potentials. Taken together, these data indicate that migrating granule cells express AMPA receptors that show substantial heterogeneity in both their single-channel conductances and rectification.

Fig. 9.

Inwardly rectifying AMPA receptor expressed by a migrating granule cell. A, Outside-out patch recording from a granule cell in the ML. Holding potentials (in millivolts) are indicated to the left of the traces. Glutamate (2 mm) and cyclothiazide (100 μm) were present throughout the recording. Data were sampled at 31.3 kHz and low-pass filtered at 2 kHz (−3 dB). B,I–V relations for the channel shown inA. The filledcirclesindicate the single-channel current (largest detectable open level) at each potential, whereas the opencirclesdenote the average current passing through the channel per unit time at each potential (from 4.5 sec of continuous data at each potential).

Granule cells express femtosiemens-conductance AMPA receptors

Consistent with the size of the single-channel currents described above, most multichannel patches from ML cells showed large increases in current noise after application of agonist (Fig.10A). In contrast, IGL patches that gave agonist-evoked currents had much smaller increases in current noise (Fig. 10B), and directly resolvable single-channel currents were noticeably absent in IGL patches with one exception. In addition, the frequency with which agonist-evoked currents were observed was lower in IGL patches (5 of 10) than in ML patches (28 of 31).

Fig. 10.

Granule cells express AMPA receptors with femtoseiman conductances. A, Top, Outside-out patch from a granule cell in the ML. Data were sampled at 9.4 kHz and low-pass filtered at 2 kHz (−3 dB). Bottom, Power spectrum of the steady-state ensemble patch current shown inA, top; γnoise = 3.7 pS (not corrected forpopen). B,Top, Outside-out patch from a mature IGL cell (P47). Note the much smaller agonist-induced current noise compared with the recording in A. Data were sampled at 9.4 kHz and low-pass filtered at 2 kHz (−3 dB). Bottom, Power spectrum of the steady-state ensemble patch current shown inA, top; γnoise = 0.43 pS (not corrected for popen).C, Outside-out patch recording from a granule cell in the ML. Note the small sustained inward current, in addition to the single-channel activity (shown on an expanded time scale in thebottomtrace). Data were sampled at 31.3 kHz and low-pass filtered at 1 kHz (−3 dB). The different kinetics of the ensemble patch currents in B and Creflect differences in the rates of solution exchange in the two experiments. cyclo, Cyclothiazide.

Our results suggest that large-conductance AMPA receptors are primarily absent from the cell bodies of IGL granule cells, although smaller-conductance channels are still somatically localized. In each of the five IGL patches that responded to agonist, we observed small inward currents that developed and recovered gradually (Fig.10B). Similar currents were observed in two ML patches. We believe that these low-noise responses are mediated by AMPA rather than by kainate receptors, because currents evoked by kainate (in the absence of concanavalin A) are blocked by the AMPA receptor antagonist GYKI 53655 (Smith et al., 1999). In the low-noise response from the ML patch shown in Figure 10C, small-conductance single-channel activity is superposed on a steady-state, low-noise current. The one IGL patch that showed detectable single-channel activity gave a very similar response. Repeated agonist application to each of the seven low-noise patches (two ML and five IGL patches) reproducibly evoked inward currents that appeared to result from the activity of numerous AMPA receptors with very small conductances. Four patches showed agonist-evoked noise increases that, although small, were sufficient to estimate the apparent unitary conductance of the channels underlying the small inward currents with spectral density analysis. The mean (± SEM) γnoise value from these four patches was 355 ± 139 fS.

Taken together, our results suggest that granule cells in situ express at least two populations of AMPA receptors on their cell bodies during development: larger-conductance AMPA receptors expressed by migrating cells that become relatively inaccessible to a patch pipette after reaching the IGL and femtosiemens-conductance AMPA receptors that are somatically expressed by granule cells in the ML and IGL.

DISCUSSION

One of our main findings is that granule cells in situexpress AMPA receptors with markedly different conductances. The femtosiemens-conductance channels we detected in some patches are similar to channels in cultured granule cells (Cull-Candy et al., 1988;Wyllie et al., 1993). Patches from migrating granule cells contained larger-conductance channels, most of which exhibited multiple open levels.

AMPA receptors expressed in cerebellar granule cellsin situ

Our results suggest that different populations of AMPA receptors may have different subcellular distributions in mature granule cells. The observation that the larger-conductance AMPA receptors (largest open level > 2 pS) became inaccessible to a patch pipette soon after granule cells arrive in the IGL suggests that these channels cluster at synapses. In contrast, the presence of femtosiemens-conductance channels in patches excised from IGL cell bodies indicates that they are located extrasynaptically, although we cannot exclude the possibility that they are also expressed at synapses. Our finding that the density of larger-conductance AMPA receptors is low on IGL cell bodies is consistent with the results ofSilver et al. (1996a), who did not detect single-channel currents in patches excised from IGL cell bodies. Our use of cyclothiazide to slow desensitization probably explains why we detected femtosiemens-conductance channels in somatic patches from IGL cells whereas Silver et al. (1996a) did not. The femtosiemens-conductance channels were observed more frequently in patches from mature IGL, rather than migrating, granule cells. Analysis of whole-cell current noise also gave smaller γnoise values for IGL than ML cells (ML, 4.21 ± 1.29 pS and n = 5 cells; IGL, 2.22 ± 0.30 pS and n = 11 cells; values corrected for popen), although the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.06, Student's t test). Together the results suggest that the relative expression of femtosiemens-conductance channels increases as granule cells mature.

The conductance of the femtosiemens channels agrees well with the estimated conductance of GluR2 homomers and is smaller than that of receptors comprised of significant amounts of GluR1, GluR3, or GluR4 (Swanson et al., 1997; Rosenmund et al., 1998; Derkach et al., 1999). Thus, although recent work has demonstrated that interactions between GluR2 and proteins such as GRIP (Dong et al., 1997) and NSF (Nishimune et al., 1998; Osten et al., 1998; Song et al., 1998) are involved in synaptic targeting of AMPA receptors, our results suggest that the extrasynaptic receptors we have detected in innervated granule cells contain substantial amounts of GluR2.

Although we do not know whether expression of the larger-conductance channels present in ML cells continues in IGL cells, synaptic clustering seems plausible, because the apparent lack of somatic expression in IGL cells coincides with synaptogenesis. The whole-cell γnoise values for ML and IGL cells suggest coexpression of the larger-conductance and femtosiemens-conductance AMPA receptors at both developmental stages. Furthermore, on average the larger-conductance channels in ML patches have conductances similar to the average conductances estimated for synaptic AMPA receptors at mossy fiber synapses (12–20 pS) (Traynelis et al., 1993; Silver et al., 1996b). Previous work has shown that AMPA (Craig et al., 1993; Mammen et al., 1997; O'Brien et al., 1997), acetylcholine (Anderson and Cohen, 1977; Frank and Fischbach, 1979), GABAA (Killisch et al., 1991), and glycine (Kirsch et al., 1993; Bechade et al., 1996) receptors cluster at synapses during synaptogenesis in cultured cells. It is possible that granule cell AMPA receptors cluster at synaptic sites in response to a signal resulting from mossy fiber activity. In support of this, recent findings indicate that the immediate-early gene product Narp, a protein expressed by presynaptic and postsynaptic terminals, clusters AMPA receptors at synapses in an activity-dependent manner (Tsui et al., 1996; O'Brien et al., 1999).

Heterogeneity of AMPA receptor single-channel properties

Another main finding of this work is that the larger-conductance AMPA receptors expressed by migrating granule cells exhibit considerable heterogeneity in their conductances, probably reflecting differences in subunit composition and perhaps differences in the relative contribution of alternative splice variants. Granule cells express mainly GluR2, GluR4, GluR4c, and to a lesser extent GluR1 (Monyer et al., 1991; Pellegrini-Giampetro et al., 1991; Gallo et al., 1992; Sato et al., 1993; Day et al., 1995; Hack et al., 1995; Ripellino et al., 1998). Swanson et al. (1997) found that recombinant GluR4 homomers activated by glutamate showed three open levels (8, 15, and 24 pS), whereas heteromeric GluR2/4 channels had only two smaller open levels (4 and 10 pS), and GluR2 homomers gave an estimated γnoise of <1 pS. Although the relationship between GluR2 abundance and single-channel conductance has not been rigorously examined, the relative abundance of GluR2 has been demonstrated to affect other channel properties. Previous work suggests that AMPA receptors are not assembled with the fixed, or severely limited, stoichiometry of other ligand-gated ion channels (Cooper et al., 1991; Gu et al., 1991; Kuhse et al., 1993; Geiger et al., 1995;Kellenberger et al., 1997; Tretter et al., 1997; Washburn et al., 1997). Although our results do not exclude the possibility that certain subunit assemblies may be preferred or that post-translational modifications contribute to channel-to-channel variability, the heterogeneity that we observe in conductances supports the hypothesis that AMPA receptor assembly is, at least in part, combinatorial. Thus differences in subunit composition are likely to be a source of heterogeneity in the number and amplitudes of open levels.

Several channels that we studied showed four distinguishable open levels. Invariably, channels showing fewer conductance levels were those where the detection of conductance sublevels would have been limited by the small size of the single-channel currents. Thus the smaller channels may have had additional sublevels that were below our resolution. Rosenmund et al. (1998) recently proposed a tetrameric model for recombinant AMPA receptors that included a singly-liganded nonconducting state. In agreement with the results of Rosenmund et al. (1998), we observed that the prevalence of sojourns in the different open levels depended on agonist concentration, with openings to the largest level becoming increasingly frequent as agonist concentration increased. If the different open levels that we observed correspond to differently liganded channel states, then the presence of four conductance levels admits two explanations. Either all AMPA receptors are tetramers, with some channels able to conduct in the singly-liganded state; or the singly-liganded state is always nonconducting, and some AMPA receptors are pentamers. The latter explanation might reconcile previous work supporting both tetrameric and pentameric assemblies (Mano and Teichberg, 1998; Rosenmund et al., 1998; Rubio et al., 1998).

Functional implications of heterogeneous AMPA receptor properties

Whether the AMPA receptors expressed by migrating granule cells serve a developmental function is unknown. A direct role in migration seems unlikely because of the observation that the AMPA receptor antagonist CNQX had no effect on granule cell migration (Komuro and Rakic, 1993). However, in vitro results have suggested a role for AMPA receptors in neuritic development (Cox et al., 1990;Mount et al., 1993; Pizzi et al., 1994).

It is also possible that the appearance of AMPA receptors in noninnervated granule cells simply reflects the preparation for impending synaptogenesis. If the channels in migrating cells are destined for synapses, this raises the possibility that the synaptic population of AMPA receptors is heterogeneous. Synaptic currents at the mossy fiber–granule cell synapse show approximately linearI–V relations (Silver et al., 1996b). One explanation for this result is that all synaptic channels in granule cells contain substantial amounts of GluR2. However, we consistently found linear or outwardly rectifying I–V relations for whole-cell currents in both ML and IGL cells, although single-channel and ensemble currents in ML patches indicate that the rectification behavior of individual AMPA receptors varied substantially. Thus it is possible that individual synaptic channels exhibit marked variation in permeation properties, yet together give an approximately linearI–V relationship. Indeed, nonstationary noise analysis of mossy fiber-evoked EPSCs has yielded average unitary conductance estimates that appear too large to arise from a homogenous population of GluR2-containing channels (Traynelis et al., 1993; Silver et al., 1996b; Swanson et al., 1997).

Although individual neurons can selectively target subsets of AMPA receptors to different synapses (Rubio and Wenthold, 1997;Tóth and McBain, 1998), there are also indications that subsets of AMPA receptors present at a given synapse can vary. Estimates of the mean conductance of receptors at the mossy fiber–granule cell synapse range from 12 to 20 pS (Traynelis et al., 1993; Silver et al., 1996b), and estimates for Schaffer collateral–commissural fiber synapses onto hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells range from 1.5 to 22.3 pS (Benke et al., 1998).

In summary, although granule cells in situ express AMPA receptors with common properties, such as multiple open levels and highpopen activity at saturating agonist concentrations, these channels also show marked differences in conductance, rectification, and kinetics. A heterogeneous population of synaptic AMPA receptors might allow a neuron to fine tune synaptic transmission by altering the incorporation of receptors with different single-channel properties.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM 58926 to J.R.H. We thank Fred Sigworth for his assistance with the hidden Markov modeling and for helpful comments on this manuscript. We also thank David Colquhoun for helpful comments and suggestions.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. James R. Howe, Department of Pharmacology, Yale University School of Medicine, 333 Cedar Street, New Haven, CT 06520-8066. E-mail: james.howe@yale.edu.

Dr. Wang's present address: Division of Neurology and The Program in Brain and Behavior, The Hospital for Sick Children, and Department of Physiology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5G 1X8.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altman J. Postnatal development of the cerebellar cortex in the rat. I. The external germinal layer and the transitional molecular layer. J Comp Neurol. 1972a;145:353–398. doi: 10.1002/cne.901450305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman J. Postnatal development of the cerebellar cortex in the rat. II. Maturation of the components of the granular layer. J Comp Neurol. 1972b;145:465–514. doi: 10.1002/cne.901450403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson MJ, Cohen MW. Nerve-induced spontaneous redistribution of acetylcholine receptors on cultured muscle cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1977;268:757–773. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ascher P, Nowak L. Quisqualate- and kainate-activated channels in mouse central neurones in culture. J Physiol (Lond) 1988;399:227–245. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bechade C, Colin I, Kirsch J, Betz H, Triller A. Expression of glycine receptor subunits and gephyrin in cultured spinal neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:429–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benke TA, Lüthi A, Isaac JTR, Collingridge GL. Modulation of AMPA receptor unitary conductance by synaptic activity. Nature. 1998;393:793–797. doi: 10.1038/31709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bettler B, Mulle C. Review: neurotransmitter receptors. II. AMPA and kainate receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:123–139. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00141-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung SH, Moore J, Xia L, Premkumar LS, Gage PW. Characterization of single-channel currents using digital signal processing techniques based on hidden Markov models. Philos Trans R Soc Lond [Biol] 1990;329:265–285. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1990.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung SH, Krishnamurthy V, Moore JB. Adaptive processing techniques based on hidden Markov models for characterizing very small channel currents buried in noise and deterministic interferences. Philos Trans R Soc Lond [Biol] 1991;334:357–384. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1991.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clements JD. Transmitter timecourse in the synaptic cleft: its role in central synaptic function. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clements JD, Lester RA, Tong G, Jahr CE, Westbrook GL. The time course of glutamate in the synaptic cleft. Science. 1992;258:1498–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1359647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colquhoun D, Ogden DC. Activation of ion channels in the frog end-plate by high concentrations of acetylcholine. J Physiol (Lond) 1988;395:131–159. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper E, Couturier S, Ballivet M. Pentameric structure and stoichiometry of a neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Nature. 1991;350:235–238. doi: 10.1038/350235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox JA, Felder CC, Henneberry RC. Differential expression of excitatory amino acid receptor subtypes in cultured cerebellar neurons. Neuron. 1990;4:941–947. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craig AM, Blackstone CD, Huganir RL, Banker G. The distribution of glutamate receptors in cultured rat hippocampal neurons: postsynaptic clustering of AMPA-selective subunits. Neuron. 1993;10:1055–1068. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90054-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cull-Candy SG, Usowicz MM. Multiple-conductance channels activated by excitatory amino acids in cerebellar neurons. Nature. 1987;325:525–528. doi: 10.1038/325525a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cull-Candy SG, Howe JR, Ogden DC. Noise and single channels activated by excitatory amino acids in rat cerebellar granule neurones. J Physiol (Lond) 1988;400:189–222. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Day NC, Williams TL, Ince PG, Kamboj RK, Lodge D, Shaw PJ. Distribution of AMPA-selective glutamate receptor subunits in the human hippocampus and cerebellum. Mol Brain Res. 1995;31:17–32. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00021-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derkach V, Barria A, Soderling TR. Ca2+/calmodulin-kinase II enhances channel conductance of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate type glutamate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3269–3274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diamond JS, Jahr CE. Transporters buffer synaptically released glutamate on a submillisecond time scale. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4672–4687. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04672.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong H, O'Brien RJ, Fung ET, Lanahan AA, Worley PF, Huganir RL. GRIP: a synaptic PDZ domain-containing protein that interacts with AMPA receptors. Nature. 1997;386:279–284. doi: 10.1038/386279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleck MW, Bähring R, Patneau DK, Mayer ML. AMPA receptor heterogeneity in rat hippocampal neurons revealed by differential sensitivity to cyclothiazide. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:2322–2333. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.6.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank E, Fischbach GD. Early events in neuromuscular junction formation in vitro. Induction of acetylcholine receptors in the postsynaptic membrane and morphology of newly formed nerve-muscle synapses. J Cell Biol. 1979;83:143–158. doi: 10.1083/jcb.83.1.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallo V, Upson LM, Hayes WP, Vyklicky L, Winters CA, Buonanno A. Molecular cloning and developmental analysis of a new glutamate receptor subunit isoform in cerebellum. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1010–1023. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-01010.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geiger JRP, Melcher T, Koh D-S, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH, Jonas P, Monyer H. Relative abundance of subunit mRNAs determines gating and Ca2+ permeability of AMPA receptors in principal neurons and interneurons in rat CNS. Neuron. 1995;15:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibb AJ, Colquhoun D. Activation of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors by l-glutamate in cells dissociated from adult rat hippocampus. J Physiol (Lond) 1992;456:143–179. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gu Y, Forsayeth JR, Verrall S, Yu XM, Hall ZW. Assembly of the mammalian muscle acetylcholine receptor in transfected COS cells. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:799–807. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.4.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hack NJ, Sluiter AA, Balazs R. AMPA receptors in cerebellar granule cells during development in culture. Dev Brain Res. 1995;87:55–61. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00054-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hámori J, Somogyi J. Differentiation of cerebellar mossy fiber synapses in the rat: a quantitative electron microscope study. J Comp Neurol. 1983;220:365–377. doi: 10.1002/cne.902200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herb A, Burnashev N, Werner P, Sakmann B, Wisden W, Seeburg PH. The KA-2 subunit of excitatory amino acid receptors shows widespread expression in brain and forms ion channels with distantly related subunits. Neuron. 1992;8:775–785. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hollmann M, Heinemann S. Cloned glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:31–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howe JR. Homomeric and heteromeric ion channels formed from the kainate-type subunits GluR6 and KA2 have very small, but different, unitary conductances. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:510–519. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.1.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howe JR, Colquhoun D, Cull-Candy SG. On the kinetics of large-conductance glutamate-receptor ion channels in rat cerebellar granule neurons. Proc R Soc Lond [Biol] 1988;233:407–422. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1988.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howe JR, Cull-Candy SG, Colquhoun D. Currents through single glutamate receptor channels in outside-out patches from rat cerebellar granule cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1991;432:143–202. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huettner JE. Glutamate receptor channels in rat DRG neurons: activation by kainate and quisqualate and blockade of desensitization by Con A. Neuron. 1990;5:255–266. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90163-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jahr CE, Stevens CF. Glutamate activates multiple single channel conductances in hippocampal neurons. Nature. 1987;325:522–525. doi: 10.1038/325522a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jonas P, Sakmann B. Glutamate receptor channels in isolated patches from CA1 and CA3 pyramidal cells of rat hippocampal slices. J Physiol (Lond) 1992;455:143–171. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamboj SK, Swanson GT, Cull-Candy SG. Intracellular spermine confers rectification on rat calcium-permeable AMPA and kainate receptors. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;486:297–303. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kellenberger S, Eckenstein S, Baur R, Malherbe P, Buhr A, Sigel E. Subunit stoichiometry of oligomeric membrane proteins: GABAA receptors isolated by selective immunoprecipitation from the cell surface. Neuropharmacology. 1997;35:1403–1411. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Killisch I, Dotti CG, Laurie DJ, Luddens H, Seeburg PH. Expression patterns of GABAA receptor subtypes in developing hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1991;7:927–936. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90338-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirsch J, Wolters I, Triller A, Betz H. Gephyrin antisense oligonucleotides prevent glycine receptor clustering in spinal neurons. Nature. 1993;366:745–748. doi: 10.1038/366745a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Komuro H, Rakic P. Modulation of neuronal migration by NMDA receptors. Science. 1993;260:95–97. doi: 10.1126/science.8096653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuhse J, Laube B, Magelei D, Betz H. Assembly of the inhibitory glycine receptor: identification of amino acid motifs governing subunit stoichiometry. Neuron. 1993;11:1049–1056. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90218-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lerma J, Paternain AV, Naranjo JR, Mellström B. Functional kainate-selective glutamate receptors in cultured hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11688–11692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mammen AL, Huganir RL, O'Brien RJ. Redistribution and stabilization of cell surface glutamate receptors during synapse formation. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7351–7358. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07351.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mano I, Teichberg VI. A tetrameric subunit stoichiometry for a glutamate receptor-channel complex. NeuroReport. 1998;9:327–331. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199801260-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mason CM, Gregory E. Postnatal maturation of cerebellar mossy and climbing fibers: transient expression of dual features on single axons. J Neurosci. 1984;4:1715–1735. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-07-01715.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McBain CJ, Dingledine R. Heterogeneity of synaptic glutamate receptors on CA3 stratum radiatum interneurones of rat hippocampus. J Physiol (Lond) 1993;462:373–392. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monyer H, Seeburg PH, Wisden W. Glutamate-operated channels: developmentally early and mature forms arise by alternative splicing. Neuron. 1991;6:799–810. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90176-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mount HTJ, Dreyfus CF, Black IB. Purkinje cell survival is differentially regulated by metabotropic and ionotropic excitatory amino acid receptors. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3173–3179. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-07-03173.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nishimune A, Isaac JTR, Molnar E, Noel J, Nash R, Tagaya M, Collingridge GL, Nakanishi S, Henley JM. NSF binding to GluR2 regulates synaptic transmission. Neuron. 1998;21:87–97. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80517-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O'Brien RJ, Mammen AL, Blackshaw S, Ehlers MD, Rothstein JD, Huganir RL. The development of excitatory synapses in cultured spinal neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7339–7350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07339.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O'Brien RJ, Xu D, Petralia RS, Steward O, Huganir RL, Worley P. Synaptic clustering of AMPA receptors by the extracellular immediate-early gene product Narp. Neuron. 1999;23:309–323. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80782-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Osten P, Srivastava S, Inman GJ, Vilim FS, Khatri L, Lee LM, States BA, Einheber S, Milner TA, Hanson PI, Ziff EB. The AMPA receptor GluR2 C-terminus can mediate a reversible, ATP-dependent interaction with NSF and α- and β-SNAPs. Neuron. 1998;21:99–110. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80518-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Partin KM, Patneau DK, Winters CA, Mayer ML, Buonanno A. Selective modulation of desensitization at AMPA versus kainate receptors by cyclothiazide and concanavalin A. Neuron. 1993;11:1069–1082. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90220-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Patlak JB. Sodium channel subconductance levels measured with a new variance-mean analysis. J Gen Physiol. 1988;92:413–430. doi: 10.1085/jgp.92.4.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patneau DK, Mayer ML. Structure–activity relationships for amino acid transmitter candidates acting at N-methyl-d-aspartate and quisqualate receptors. J Neurosci. 1990;10:2385–2399. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-07-02385.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Patneau DK, Vyklicky L, Jr, Mayer ML. Hippocampal neurons exhibit cyclothiazide-sensitive rapidly desensitizing responses to kainate. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3496–3509. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03496.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]