Abstract

Despite clinical evidence that thyroid hormone is essential for brain development before birth, effects of thyroid hormone on the fetal brain have been largely unexplored. One mechanism of thyroid hormone action is regulation of gene expression, because thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) are ligand-activated transcription factors. We used differential display to identify genes affected by acute T4administration to the dam before the onset of fetal thyroid function. Eight of the 11 genes that we identified were selectively expressed in brain areas known to contain TRs, indicating that these genes were directly regulated by thyroid hormone. Using in situhybridization, we confirmed that the cortical expression of both neuroendocrine-specific protein (NSP) and Oct-1 was affected by changes in maternal thyroid status. Additionally, we demonstrated that both NSP and Oct-1 were expressed in the adult brain and that their responsiveness to thyroid hormone was retained. These data are the first to identify thyroid hormone-responsive genes in the fetal brain.

Keywords: thyroid hormone, neuroendocrine-specific protein, NSP, Oct-1, POU-domain, cerebral cortex, brain development, differential display, congenital hypothyroidism

It is well known that thyroid hormone is essential for normal mammalian brain development (Oppenheimer and Schwartz, 1997). However, until recently it was generally believed that the effects of thyroid hormone on brain development occur only after birth (Fisher, 1999). Several recent clinical observations provide evidence to the contrary. First, thyroid hormone of maternal origin crosses the placenta and reaches the fetus (Vulsma et al., 1989; Contempre et al., 1993). In addition, the receptors for thyroid hormone (TRs) are expressed in the fetal brain before the onset of fetal thyroid function, and receptor occupancy is within the range known to elicit physiological effects (Bernal and Pekonen, 1984; Ferreiro et al., 1988). Second, iodine therapy prevents neurological cretinism in regions of endemic goiter only if initiated before the beginning of the third trimester (Cao et al., 1994). Moreover, children born to pregnant women with untreated hypothyroidism during the second trimester exhibit measurable neurological deficits despite normal circulating thyroid hormone at birth (Haddow et al., 1999; Pop et al., 1999). These findings strongly suggest that thyroid hormone, perhaps of maternal origin, plays important roles in brain development before birth.

The present study was initiated to test the broad hypothesis that thyroid hormone of maternal origin can exert direct effects on brain development before birth. Our strategy for testing this hypothesis was based on the recognition that thyroid hormone of maternal origin can reach the rat fetus (Obregon et al., 1984; Porterfield and Hendrich, 1992) and that TRs are expressed in the fetal rat brain before the onset of fetal thyroid function (Perez-Castillo et al., 1985; Bradley et al., 1992; Falcone et al., 1994). Therefore, considering that TRs are ligand-activated transcription factors (Lazar, 1993, 1994;Mangelsdorf and Evans, 1995), we predicted that thyroid hormone of maternal origin can affect fetal brain development by regulating the expression of specific genes.

The classes of genes regulated by thyroid hormone in the fetal brain were difficult to predict because thyroid hormone is known to influence many cellular and developmental processes in the postnatal brain (Dussault and Ruel, 1987), and the classes of genes supporting these processes may be widely varied. Therefore, we used the nonbiased method of differential display (Liang and Pardee, 1992) to identify putative thyroid hormone-responsive genes in the fetal cortex. To ensure that we identified genes regulated by thyroid hormone of maternal origin, we focused on the period of fetal development before the onset of fetal thyroid function (Fisher et al., 1977).

We now report the identification of several putative thyroid hormone-responsive genes that are selectively expressed in areas of the fetal brain that also express TRs. In addition, we have further characterized the response to thyroid hormone of two of these genes, one encoding neuroendocrine-specific protein (NSP) and one encoding Oct-1, in both the fetal and adult cortex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for animal research and were approved by the University of Massachusetts-Amherst Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Experiment I: Identification of thyroid hormone-responsive genes in the fetal cortex using differential display. Nulliparous female Sprague Dawley rats (n = 10; Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were surgically thyroidectomized, provided with 0.1% calcium chloride in the drinking water (Zoeller et al., 1988), and maintained on normal rat chow. Two weeks after thyroidectomy, the females were paired with males overnight; the presence of sperm in a vaginal smear the following morning indicated mating, and this day was considered gestational day (GD) 1. Dams were given subcutaneous injections of either thyroxine [T4; 1.25 μg/100 gm body weight (BW); Sigma, St. Louis, MO] or saline at 9 A.M. and 4 P.M. on GD15. At 9 A.M. on GD16, dams were decapitated, and trunk blood was collected for measurement of serum T4. Half of the fetuses from each litter were frozen intact on pulverized dry ice and stored at −80°C. Parasagittal sections of these GD16 fetuses were later collected forin situ hybridization. The cortex was dissected from the remaining fetuses, frozen on pulverized dry ice, and stored at −80°C until extraction of RNA.

Total RNA was isolated from the cortex of one GD16 fetus obtained from a dam with undetectable circulating total T4 and from the cortex of one GD16 fetus from a dam with normal levels of total T4 (23.1 ng/ml). Total RNA was extracted using an acid-phenol extraction procedure (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 1987). This RNA was subjected to reverse transcription (RT) and amplified by RT-PCR according to the manufacturer's instructions (RNAimage, GenHunter, Nashville, TN). The PCR products amplified from each RNA pool using 16 primer pair combinations were electrophoresed in adjacent lanes on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The gel was dried and apposed overnight to BioMax autoradiographic film (Kodak, Rochester, NY). Gene fragments that on film appeared to be either upregulated or downregulated by T4injection were extracted from the gel, reamplified, and cloned into pCRII (InVitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or pBluescript KS (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) (Table 1). Sequencing was performed using ABI FS-Dye-Terminator chemistry (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Table 1.

Putative thyroid hormone-responsive genes identified by differential display (Experiment I)

| cDNA fragment1-a | Match in GenBank | DNA identity % | GenBank accession no. | Reference | mRNA localization in GD16 fetus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2A | Cl-13/ | 97.7 | X52817 | Wieczorek and Hughes, 1991 | Cortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus, |

| NSP/ | 85.6 | L10333 | Roebroek et al., 1993 | diencephalon, midbrain, medulla, spinal cord, | |

| s-rexb | 98.4 | U17604 | Baka et al., 1996 | trigeminal ganglion | |

| 18C | Oct-1 | 99.0 | U17013 | J. N. Buskin, unpublished data | Cortex, hippocampus, diencephalon, midbrain, retina, liver |

| 6C | None | N/A | AF1332731-b | Cortex, hippocampus, diencephalon, midbrain, spinal cord, liver | |

| 15A | None | N/A | AF1332741-b | Cortex, retina, liver | |

| 4C | None | N/A | AF1332751-b | Cortex, midbrain, liver | |

| 5C | None | N/A | AF1332761-b | Cortex, midbrain, liver | |

| 17C | BC1 | 98.0 | M16113 | DeChiara and Brosius, 1987 | All tissues |

| 17CB | Ribosomal protein L31 | 91.9 | X04809 | Tanaka et al., 1987 | Cortex, hippocampus, midbrain, liver |

| 18AL1-c | N/A | Global expression | |||

| 18AS1-c | N/A | Global expression | |||

| 14C1-c | N/A | Global expression |

RNAimage primers used to generate cDNA fragments: number indicates H-AP forward arbitrary primer (1–8), letter indicates H-T11M reverse primer (H-T11A, H-T11C, or H-T11G), and a prefix of 1 indicates upregulation by thyroid hormone. For example, fragment 18C is upregulated by thyroid hormone and was generated using H-AP8 and H-T11C primers.

Submitted to GenBank at the time of manuscript submission.

Fragments not sequenced. Global expression pattern revealed by in situ hybridization suggested that these fragments were falsely identified differential display products.

Experiment II: Verification of thyroid hormone-responsive genes in the fetal brain. Nulliparous female Sprague Dawley rats (n = 44; Zivic Miller, Pottersville, PA) were exposed to the goitrogen 2-mercapto-1-methylimidazole (MMI; Sigma;n = 23) to block the synthesis of thyroid hormone. MMI was dissolved to 0.02% in drinking water and provided fresh daily. Controls (n = 21) were provided with unaltered drinking water. After 2 weeks of MMI treatment, the females were mated as described above. Both hypothyroid (MMI-treated) dams and euthyroid controls (no MMI) were subdivided into five additional groups receiving either no injection or a single subcutaneous injection of T4 (1.25 μg/100 gm BW; Sigma) at either 9 A.M. or 9 P.M. on either GD14 or GD15. These injections were therefore timed to occur 48, 36, 24, or 12 hr before animals were killed at 9 A.M. on GD16. At 9 A.M. on GD16, all dams were decapitated, and trunk blood was collected for measurement of serum T4and thyrotropin (TSH). All fetuses were frozen intact as described above. Frontal sections through the cortex and thalamus of one fetus from each dam were collected (Altman and Bayer, 1995).

After in situ hybridization, the signal was measured over the cortex and thalamus of GD16 fetal brains using the thresholding function in which all pixels containing density values exceeding a minimum value were averaged over the specified brain area. The resulting values were averaged over four sections for each fetus, with one fetus per litter and four to five litters per treatment group. A two-way ANOVA, with main effects of MMI treatment and timing of acute T4 exposure, was followed by Bonferroni'st test.

To confirm the in situ hybridization results, we performed Northern analysis on RNA extracted from fetal cortex derived from dams treated with either MMI alone or MMI plus T4. The cortex was dissected from one GD16 fetus per litter, derived from uninjected MMI-treated dams (n = 4) and MMI-treated dams injected with T4 at 9 P.M. on GD14 (n = 5). RNA was extracted from these tissue pools as described above. Four replicates of total RNA from each pool (20 μg RNA per lane) were electrophoresed with RNA molecular weight standards (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) on a 1.2% agarose/6.5% formaldehyde gel. RNA was transferred to a nylon Zeta-Probe membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and cross-linked by baking. Cyclophilin and NSP probes were generated by both random primer labeling and nick translation in the presence of32P-dCTP according to the manufacturer's instructions (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). Both types of cyclophilin and NSP probes were mixed and hybridized simultaneously to ensure adequate detection of the target mRNA. Membranes were briefly prehybridized, hybridized at high stringency with 106 cpm probe/106 cpm probe/1 ml hybridization buffer, and washed according to manufacturer's instructions. The membranes were then apposed to a storage phosphor screen (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA), scanned into a Storm 840 Phosphorimager at 200 μm resolution, and evaluated with ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics). The density of each band was quantified and normalized with respect to cyclophilin to control for loading variations. Student's t test was used to compare normalized band densities between the two RNA pools. In a separate experiment, serial dilutions of total RNA demonstrated a linear relationship between the amount of total RNA loaded and intensity of the cyclophilin signal between 5 and 20 μg RNA (data not shown).

Experiment III: Developmental pattern of NSP and Oct-1 expression in the brain. We initiated this study to define changes in NSP and Oct-1 expression during development to ensure that the pattern of expression observed in adults represents continuous expression from embryonic life. Nulliparous female Sprague Dawley rats (n = 6; Zivic Miller) were maintained on rat chow and unaltered drinking water ad libitum and mated as described above. Five dams (n = 1 per GD) were decapitated at 12 P.M. on GD14, GD16, GD18, and GD21, and the fetuses were collected and sectioned as described in Experiment II. The remaining dam carried the pregnancy to term. The resulting pups [n = 1 per postnatal day (PND)] were decapitated at 12 P.M. on PND3, -6, -9, -11, -14, and -19, and the intact heads (PND11 or earlier) or brains (PND14–PND19) were frozen on pulverized dry ice and stored at −80°C. An adult male Sprague Dawley rat was used to determine the expression pattern in the adult brain. Coronal sections were collected through the brain at the level of the rostral dentate gyrus.

Experiment IV: Effect of thyroid hormone on NSP and Oct-1 expression in the adult brain. We tested whether NSP and Oct-1 expression is affected by thyroid status in adults because it allowed us to test the thyroid hormone responsiveness of these genes in the absence of the maternal system and provided information about the temporal window of sensitivity to thyroid hormone. We manipulated thyroid hormone status of adult male Sprague Dawley rats (n = 23, 155–190 gm; Zivic Miller), as described byKoller et al. (1987). Each animal received a single intraperitoneal injection of either saline or 6-(n-propyl)-2-thiouracil (PTU; 1 mg/100 gm BW; Sigma) (Dyess et al., 1988) to block both thyroid hormone synthesis and the conversion of T4 to triiodothyronine (T3) by type I 5′-deiodinase (Chopra, 1996; Leonard and Koehrle, 1996). PTU-treated animals (n = 12) were maintained for 12 d after PTU treatment on 0.05% MMI in the drinking water, provided fresh daily, and at 9 A.M. they received daily subcutaneous injections of either T3 (10 μg/100 gm BW; Sigma; n = 6) or 100 μl saline/100 gm BW (n = 6). The remaining rats (n = 11, no PTU) were maintained on unaltered drinking water and at 9 A.M. received daily subcutaneous injections of either 10 μg T3/100 gm BW (n = 6) or 100 μl saline/100 gm BW (n = 5).

After treatment, animals were decapitated at 1 P.M., and trunk blood was collected for measurement of serum total T3, total T4, and TSH. Additionally, the relative abundance of the mRNA encoding thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH) was measured in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN). Brains were collected and immediately frozen as described above. Coronal sections were collected through the brain at the level of the PVN (Paxinos and Watson, 1986, their Fig. 25) and through the cortex and hippocampus at the transition from the frontal cortex to the occipital cortex (Paxinos and Watson, 1986, their Figs. 31–33). Sagittal sections were collected through the cerebellum (Paxinos and Watson, 1986, their Fig. 79).

After in situ hybridization, the signal was measured over the PVN (only for TRH), cortex, dentate gyrus, CA1, CA2, CA3, and cerebellum. Signals in the cortex and hippocampus were measured without using thresholding, whereas measurements in the PVN and cerebellum were obtained using thresholding as described above. These values were averaged over four sections for each brain region, with five to six animals per treatment group. A two-way ANOVA, with main effects of MMI treatment and T3 injection, was followed by Bonferroni's t test.

Radioimmunoassay. Total T4 was measured according to the manufacturer's instructions using a T4 RIA kit (ICN, Costa Mesa, CA). This assay was performed at 40% binding with detection limits of 10–200 ng/ml and an intra-assay variation of 3.5%. Total T3 was measured according to the manufacturer's instructions using a T3 radioimmunoassay (RIA) kit (ICN). This assay was performed at 49% binding with detection limits of 0.25–8 ng/ml and an intra-assay variation of 4.4%. Serum levels of TSH were measured using 125I-rat TSH (Covance Laboratories, Vienna, VA) and the double antibody National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases RIA reagents including RP-3 standards. This assay was performed at 25% binding with detection limits of 1–50 ng/ml and an intra-assay variation of 8.0%.

In situ hybridization. In all experiments, frozen tissues were sectioned at 12 μm in a cryostat (Reichert-Jung Frigocut 2800N). Sections were thaw-mounted onto gelatin-coated microscope slides and stored at −80°C until hybridization. In situhybridization was performed as described previously (Scott et al., 1998), with two exceptions. First, the hybridization buffer also contained 0.1% sodium pyrophosphate. Second, the hybridization buffer contained 200 mm dithiothreitol rather than 50 mm.

Probes. cRNA probes were generated from cDNA constructs described in Table 2. Transcription reactions were performed in the presence of33P-αUTP (Andotek, Irvine, CA), as described previously (Scott et al., 1998). In each case, the total concentration of UTP was held to 12 μm, including 6 μm33P-αUTP.

Table 2.

Characteristics of plasmids used to prepare cRNA probes forin situ hybridization

| cDNA | Vector | Insert length (bp) | Antisense2-a | Sense2-b | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRα1 | pGEM3Z | 681 | EcoRI/Sp6 | HindIII/T7 | Bradley et al., 1989 |

| TRβ1 | pGEM3Z | 681 | EcoRI/Sp6 | HindIII/T7 | Bradley et al., 1989 |

| 2A | pCRII | 461 | EcoRV/Sp6 | BamHI/T7 | Table1 |

| 18C | pCRII | 146 | BamHI/T7 | EcoRV/Sp6 | Table1 |

| 6C | pCRII | 185 | EcoRV/Sp6 | BamHI/T7 | Table1 |

| 15A | pCRII | 423 | EcoRV/Sp6 | BamHI/T7 | Table1 |

| 4C | pCRII | 212 | EcoRV/Sp6 | BamHI/T7 | Table1 |

| 5C | pCRII | 212 | EcoRV/Sp6 | KpnI/T7 | Table1 |

| 17C | pCRII | 241 | BamHI/T7 | EcoRV/Sp6 | Table1 |

| 17CB | pBluescript | 172 | EcoR1/T3 | ClaI/T7 | Table1 |

| 18AL | pCRII | 100 | EcoRV/Sp6 | BamHI/T7 | Table1 |

| 18AS | pCRII | 100 | BamHI/T7 | EcoRV/Sp6 | Table1 |

| 14C | pBluescript | 220 | BamHI/T7 | XhoI/T3 | Table1 |

| TRH | pSp65 | 1200 | HindIII/Sp6 | Lechan et al., 1986 |

The enzyme used for linearizing the plasmid and the polymerase used to produce the complementary (antisense) RNA probe.

The enzyme used for linearizing the plasmid and the polymerase used to produce the control (sense) RNA probe.

Autoradiography and signal quantitation. Slides were arranged in x-ray cassettes and apposed to BioMax film (Kodak), where the duration of exposure was dependent on the specific activity of the probe and the abundance of the target message.14C standards (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) were simultaneously apposed to the film to verify that the film was not overexposed. Hybridization signal was analyzed as described previously (Scott et al., 1998) using a PowerCenter 150 Macintosh computer and the public domain NIH Image program (W. Rasband, National Institute of Mental Health). This system was interfaced with a Dage-MTI 72 series video camera equipped with a Nikon macro lens mounted onto a bellows system over a light box.

Statistical analysis. Outliers, defined as those values exceeding 1.5 interquartile ranges from the upper and lower quartiles, were eliminated using a box and whisker plot (Statistix, Analytical Software, Tallahassee, FL). A two-way ANOVA (Systat, Systat, Inc., Evanston, IL) was performed on the remaining values, with main effects described in the specific experiment. Post hoc tests of differences among individual means were performed using a Bonferroni'st test, in which the mean squared error term from the ANOVA table was used as a point estimate of the pooled variance.

RESULTS

Experiment I: Identification of thyroid hormone-responsive genes in the GD16 cortex

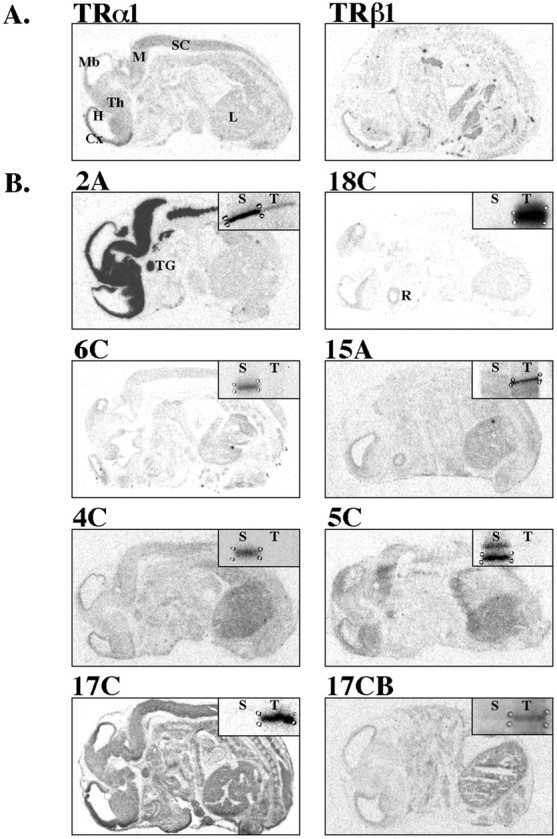

We manipulated maternal thyroid status before the onset of fetal thyroid function to ensure that maternal T4 was the sole source of thyroid hormone to the fetus. Using differential display, we identified 11 putative thyroid hormone-responsive genes in the fetal cortex generated from eight RNAimage primer combinations (Table 1). Seven of these genes appeared to be enhanced by T4, and four appeared to be suppressed by T4. Before sequencing these gene fragments, we performed in situ hybridization to determine whether their expression pattern overlapped with that of TRα1 or TRβ1. Among the original 11 genes, we found that eight exhibited anatomical patterns of expression overlapping with that of TRα1 or TRβ1 (Fig.1), indicating that they may be directly regulated by thyroid hormone. We chose to further evaluate three of these genes, two whose sequences matched entries in GenBank (Table 1). Fragment 2A was identical to NSP (Wieczorek and Hughes, 1991; van de Velde et al., 1994b; Baka et al., 1996) and was suppressed by T4; fragment 18C was identical to Oct-1 (J. N. Buskin, unpublished observations) and was enhanced by T4; and fragment 6C did not match the sequence of any GenBank entry and was suppressed by T4.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of putative thyroid hormone-responsive genes in the GD16 embryo. Images are derived from film autoradiograms after in situ hybridization to determine whether putative thyroid hormone-responsive mRNAs identified by differential display RT-PCR were expressed in areas known to contain TR mRNAs (Experiment I). RNA probes were applied to sagittal sections of GD16 rat embryos. Sense controls were applied to adjacent sections and produced negligible hybridization signal (data not shown), with the exception of fragment 17C, which we did not examine further.A, Distribution of TRα1 and TRβ1 mRNA.B, Distribution of putative thyroid hormone-responsive mRNAs as noted above panel. Film autoradiograms of gene fragments identified by differential display are shown in insets, illustrating direction of thyroid hormone effects. See Table 1 for RNAimage primers used to generate each fragment. Cx, Cortex; H, hippocampus; L, liver;M, medulla; Mb, midbrain;R, retina; S, saline-injected;SC, spinal cord; T, T4-injected; TG, trigeminal ganglion;Th, thalamus. Scale bar, 0.5 cm.

Experiment II: Verification of maternal thyroid hormone effects on the expression of NSP, Oct-1, and 6C

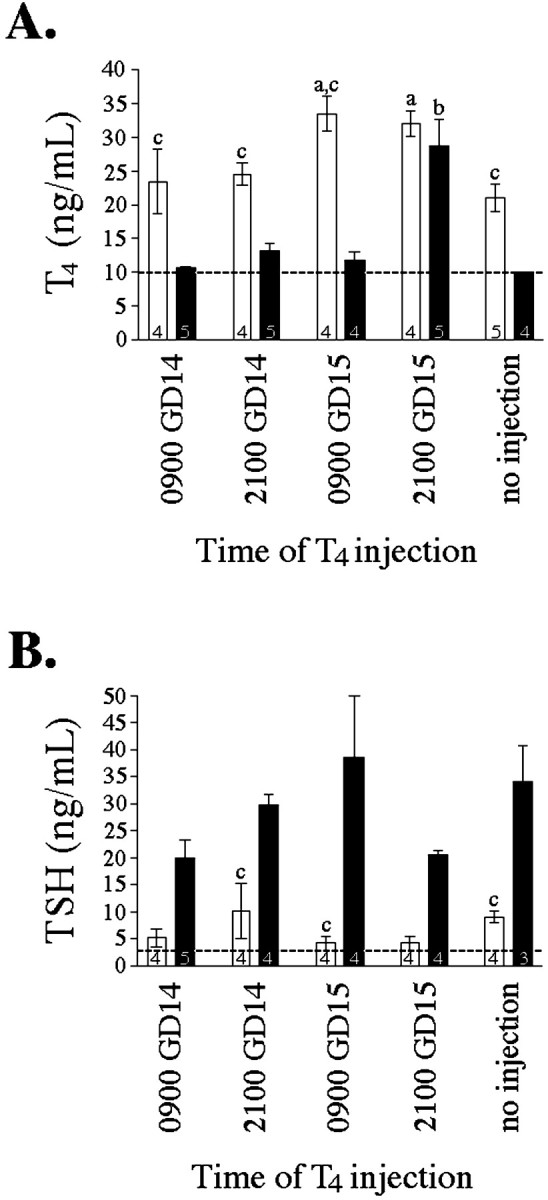

We confirmed the efficacy of our thyroid hormone manipulation of pregnant female rats by measuring maternal serum total T4 and TSH (Fig.2). Treatment with the goitrogen MMI significantly reduced circulating levels of maternal T4 (F(1,34) = 59.957; p < 0.001) and significantly elevated serum TSH (F(1,30) = 50.983;p < 0.001). Treatment with thyroid hormone significantly elevated maternal serum T4(F(4,34) = 11.776; p< 0.001) (Fig. 2). A single injection of 1.25 μg T4/100 gm BW transiently restored circulating T4 to physiological levels and transiently suppressed TSH levels in hypothyroid dams, as predicted. However, physiological levels of T4 were restored only 12 hr after T4 injection in hypothyroid dams, but remained elevated in euthyroid dams for at least 24 hr (Fig. 2). Likewise, TSH suppression was evident for a shorter duration in hypothyroid dams. These data are consistent with previous work showing that thyroid hormone is cleared from the serum of hypothyroid dams more rapidly than from that of euthyroid dams (Versloot et al., 1998).

Fig. 2.

Effect of MMI and T4 injections on serum levels of T4 (A) and TSH (B) in GD16 pregnant females at the time they were decapitated (Experiment II). See Materials and Methods for details of thyroid hormone manipulation. Bars represent mean ± SEM, with number of dams per group noted within each bar. All animals were killed at 9 A.M. (0900) on GD16. Groups differed in the timing of T4 injection as shown below the ordinate. Open bars, Euthyroid dams (no MMI); closed bars, hypothyroid dams (MMI). a Significantly different from euthyroid dams receiving no injection (p < 0.05). b Significantly different from hypothyroid dams receiving no injection (p < 0.05).c Significantly different from hypothyroid dams with identical timing of acute T4 treatment (p < 0.05). Note: Serum hormone levels below detection limit were assigned the value of the detection limit (indicated by dashed line) for statistical purposes.

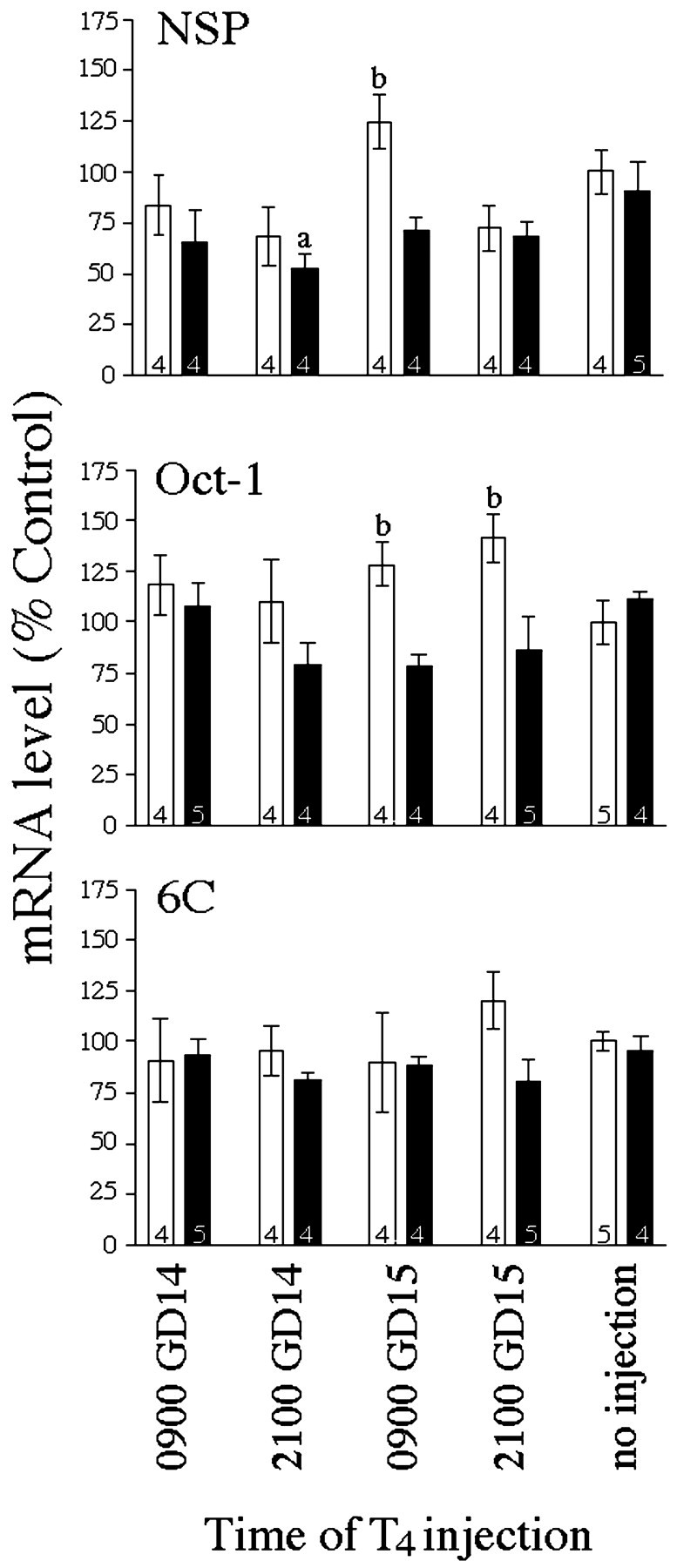

We measured the effects of maternal thyroid hormone manipulation on gene expression in the fetal brain using in situhybridization because this approach allowed us to evaluate the potential site-specific effects of thyroid hormone on NSP, Oct-1, and 6C expression. Quantitative analysis of film autoradiograms afterin situ hybridization revealed that both MMI (F(1,31) = 9.851; p < 0.004) and maternal thyroid hormone (F(4,31)=5.146; p < 0.003) significantly affected NSP expression in the GD16 cortex (Fig.3). Maternal thyroid hormone exposure significantly decreased NSP mRNA in the cortex of hypothyroid animals 36 hr after T4 injection (9 P.M. on GD14). In contrast, thyroid hormone exposure significantly increased Oct-1 mRNA in the cortex of euthyroid animals 12 and 24 hr after T4 injection (9 P.M. and 9 A.M., respectively, on GD15). These results are consistent with those of the original differential display where NSP expression was decreased by maternal thyroid hormone and Oct-1 expression was increased by maternal thyroid hormone. The expression of neither NSP nor Oct-1 was affected by thyroid hormone in the thalamus (data not shown). Additionally, 6C was not affected by thyroid hormone in either the cortex or the thalamus, suggesting that it was falsely identified as being thyroid hormone responsive in the differential display.

Fig. 3.

Effect of thyroid hormone manipulation on gene expression in the GD16 fetus (Experiment II). Quantitative analysis of film autoradiograms after in situ hybridization for NSP, Oct-1, and 6C are described in Materials and Methods. Bars represent mean ± SEM of the film density (converted to % controls ± CV) over the cortex, with number of dams per group noted within each bar. All animals were killed at 9 A.M. (0900) on GD16. Groups differed in the timing of T4 injection as shown below the ordinate. Open bars, Euthyroid dams (no MMI);closed bars, hypothyroid dams (MMI).a Significantly different from hypothyroid dams receiving no injection (p < 0.05).b Significantly different from hypothyroid dams with identical timing of acute T4 treatment (p < 0.05).

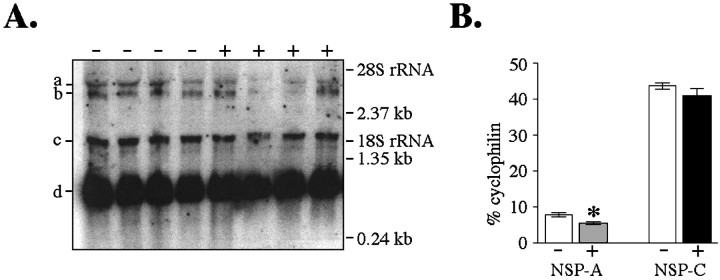

Previous work has shown that two mRNAs are transcribed from the NSP gene, a 1.5 kb transcript (NSP-C) and a 3.5 kb transcript (NSP-A) (Ninkina et al., 1997; Roebroek et al., 1998). Because these transcripts have a common 3′ end identical to the NSP fragment amplified in the original differential display, our in situhybridization probe hybridized to both transcripts. Therefore, we performed Northern analysis to determine whether both NSP transcripts are affected by maternal thyroid hormone. Northern analysis revealed that our probe hybridized to the predicted 1.5 and 3.5 kb transcripts (Fig. 4A). Expression of the 3.5 kb NSP-A transcript was significantly decreased (30.7 ± 13.0%) in fetuses derived from hypothyroid dams treated with T4 (Fig. 4B). In contrast, expression of the 1.5 kb NSP-C transcript was unaffected by acute maternal thyroid hormone manipulation.

Fig. 4.

Effect of thyroid hormone manipulation on the expression of NSP variants using quantitative Northern analysis (Experiment II). A, Phosphor-image of Northern blot in which 20 μg total RNA was hybridized with 32P-labeled NSP cDNA. 32P-labeled cyclophilin cDNA was hybridized simultaneously to control for loading variations. RNA was isolated from GD16 fetuses derived from hypothyroid dams receiving either no injection (−) or a single T4 injection at 9 P.M. on GD14 (+). Each sample corresponds to RNA pooled from four or five animals. Positions of the molecular weight standards and the 18S and 28S ribosomal RNAs are indicated. B, Quantification of band density shown in A using ImageQuant software. NSP-A mRNA was decreased after acute maternal T4 exposure. Bars represent mean band density ± SEM (converted to % total cyclophilin). a Transcript of 3.5 kb hybridized to NSP probe, corresponding to NSP-A. b Transcript of 3.4 kb hybridized to cyclophilin probe. c Transcript of 1.5 kb hybridized to NSP probe, corresponding to NSP-C.d Transcript of 0.9 kb hybridized to cyclophilin probe. *Significantly different from hypothyroid dams receiving no injection (p < 0.05).

Experiment III: Developmental pattern of NSP and Oct-1 expression

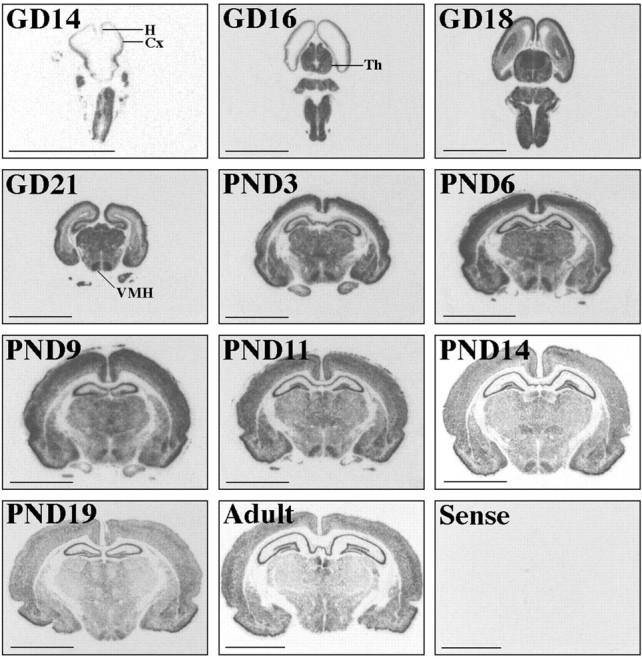

After the initial observation that both NSP and Oct-1 were regulated by thyroid hormone in the GD16 cortex, we characterized the distribution and relative abundance of these mRNAs during development. We found that NSP expression was restricted to the nervous system at all times (Fig. 5). NSP mRNA was clearly detectable at GD14, the earliest developmental time evaluated. NSP expression was more robust in the intermediate zone of the cortex than in the ventricular zone [nomenclature derived from Boulder Committee (1970)]. Additionally, NSP mRNA was more abundant during the fetal and neonatal period but became less abundant from approximately PND14 through adulthood. Regional differences in NSP expression were apparent throughout brain development. For example, NSP expression was predominant in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus beginning around the time of birth and persisting into adulthood. The hippocampus, medial habenular nucleus, and amygdala were also intensely labeled. The corpus callosum and other myelinated fiber bundles were never labeled.

Fig. 5.

Developmental profile of NSP expression in the rat. Images are derived from film autoradiograms after in situ hybridization using the NSP cRNA probe (Experiment III). Age is noted in the top left corner of each panel.Cx, Cortex; H, hippocampus;Th, thalamus; VMH, ventromedial hypothalamus. Scale bar, 0.5 cm.

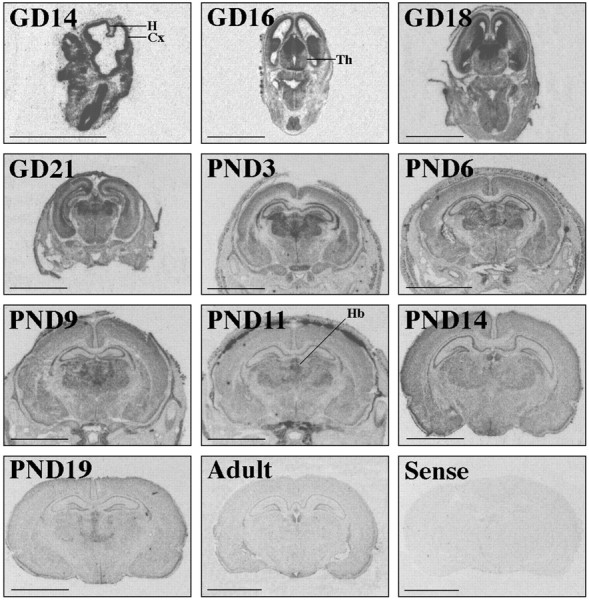

Oct-1 mRNA was expressed both within the brain and outside the nervous system (Fig. 6). Oct-1 expression was predominant in the ventricular zone of the cortex of fetal brains. Regional differences in Oct-1 expression levels were apparent throughout brain development. For example, Oct-1 expression was abundantly expressed in the thalamus from approximately GD16 until PND14. As development proceeded, Oct-1 expression became less robust and more spatially restricted, although expression was retained in the hippocampus.

Fig. 6.

Developmental profile of Oct-1 expression in the rat. Images are derived from film autoradiograms after in situ hybridization using the Oct-1 cRNA probe (Experiment III). Age is noted in the top left corner of each panel.Cx, Cortex; H, hippocampus;Th, thalamus; Hb, habenula. Scale bar, 0.5 cm.

Experiment IV: Effect of thyroid hormone on NSP and Oct-1 expression in the adult brain

The developmental study demonstrated that NSP and Oct-1 were continually expressed in the cortex from fetal life to adulthood. Therefore, we evaluated the effect of thyroid status on the expression of these genes in the adult brain to determine whether these genes retained their responsiveness to thyroid hormone. We confirmed the efficacy of our thyroid hormone manipulations of adult male rats by measuring serum T3, T4, and TSH and by measuring TRH mRNA in the PVN of the hypothalamus, which is known to be suppressed by thyroid hormone (Koller et al., 1987). Treatment with PTU and MMI significantly reduced circulating levels of T4 (F(1,18) = 2349.446; p < 0.001), elevated serum TSH (F(1,17) = 14.075; p< 0.002), and elevated TRH mRNA in the PVN (F(1,19) = 10.845; p< 0.004) (Table 3). Daily T3 injections significantly reduced circulating levels of T4(F(1,18) = 2349.446; p< 0.001), elevated T3(F(1,19) = 91.169; p< 0.001), and suppressed TRH mRNA in the PVN (F(1,19) = 125.763; p< 0.001), consistent with negative feedback of thyroid hormone on the pituitary and hypothalamus (Koller et al., 1987; Dyess et al., 1988;Zoeller et al., 1988).

Table 3.

Serum levels of total T3, total T4, and TSH, and expression levels of TRH mRNA in the PVN of adult thyroid hormone-manipulated animals (Experiment IV)

| Thyroid status | T3(ng/ml) | T4 (ng/ml) | TSH (ng/ml) | TRH (% control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.790 ± 0.055 (5) | 55.750 ± 1.335 (4) | 12.013 ± 2.742 (5) | 100.00 ± 2.171 (5) |

| T3 | 6.160 ± 0.517 (6)** | UD (6) | 5.110 ± 1.371 (5) | 85.50 ± 2.185 (6)** |

| MMI + PTU | 0.590 ± 0.042 (6) | UD (6) | 29.436 ± 6.903 (6)* | 111.37 ± 1.640 (6)** |

| MMI + PTU + T3 | 6.620 ± 1.009 (6)** | UD (6) | 4.161 ± 0.828 (5) | 85.87 ± 3.535 (6)** |

Serum T3, T4, and TSH values represent mean ± SEM (n). TRH values represent mean ± SEM (n) of film density (converted to % control ± CV) over the PVN.

* Significantly different from control euthyroid rats receiving saline injections (p < 0.05).

** Significantly different from control euthyroid rats receiving saline injections (p < 0.01).

UD, Undetectable. Serum hormone levels were assigned the value of the lower assay detection limit for statistical purposes.

Combined PTU and MMI treatment significantly elevated NSP mRNA in the dentate gyrus (F(1,17) = 6.719;p < 0.02) and CA1 subfield of Ammon's horn (F(1,18) = 4.777; p < 0.05) (Table 4). Additionally, T3 treatment significantly decreased NSP mRNA in the dentate gyrus (F(1,17) = 6.682;p < 0.02). NSP mRNA levels in the cortex, CA2, and CA3 subfields, and cerebellum were unaffected by treatments. In contrast, T3 treatment significantly reduced Oct-1 mRNA in the cortex (F(1,19) = 19.362;p < 0.001), dentate gyrus (F(1,19) = 15.843; p< 0.001), CA2 (F(1,17) = 19.147;p < 0.001), and CA3 (F(1,19) = 23.189; p< 0.001) (Table 4). Oct-1 mRNA levels in the CA1 subfield and cerebellum were unaffected by treatments.

Table 4.

Effect of thyroid hormone on NSP and Oct-1 mRNA in the adult brain (Experiment IV)

| Thyroid status | Brain region | NSP mRNA | Oct-1 mRNA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Cortex | 100.00 ± 2.44 (5) | 100.00 ± 0.45 (5) |

| T3 | 99.12 ± 1.85 (6) | 92.70 ± 1.58 (6)** | |

| MMI + PTU | 104.00 ± 2.58 (6) | 99.45 ± 0.77 (6) | |

| MMI + PTU + T3 | 101.01 ± 1.22 (6) | 95.71 ± 1.40 (6)* | |

| Control | Dentate gyrus | 100.00 ± 1.73 (5) | 100.00 ± 1.66 (5) |

| T3 | 98.51 ± 0.71 (5) | 96.01 ± 1.48 (6)* | |

| MMI + PTU | 105.09 ± 1.08 (5)* | 101.09 ± 0.52 (6) | |

| MMI + PTU + T3 | 100.01 ± 1.27 (6) | 95.99 ± 0.81 (6)* | |

| Control | CA14-a | 100.00 ± 1.09 (4) | 100.00 ± 1.55 (4) |

| T3 | 105.27 ± 1.75 (6) | 97.94 ± 1.57 (6) | |

| MMI + PTU | 108.80 ± 2.08 (6)* | 101.97 ± 1.11 (6) | |

| MMI + PTU + T3 | 104.17 ± 1.27 (6) | 97.42 ± 1.13 (6) | |

| Control | CA24-a | 100.00 ± .67 (3) | 100.00 ± 1.10 (5) |

| T3 | 101.36 ± 1.65 (6) | 95.82 ± 0.98 (6)* | |

| MMI + PTU | 105.93 ± 1.54 (5) | 99.37 ± 0.20 (4) | |

| MMI + PTU + T3 | 100.20 ± 1.15 (6) | 95.11 ± 10.4 (6)** | |

| Control | CA34-a | 100.00 ± 0.85 (4) | 100.00 ± 0.26 (5) |

| T3 | 100.64 ± 0.68 (4) | 94.00 ± 1.86 (6)** | |

| MMI + PTU | 105.51 ± 1.81 (6) | 98.90 ± 0.92 (6) | |

| MMI + PTU + T3 | 101.30 ± 1.26 (6) | 93.32 ± 0.81 (6)** | |

| Control | Cerebellum | 100.00 ± 1.64 (4) | 100.00 ± 0.40 (4) |

| T3 | 97.58 ± 0.61 (6) | 100.14 ± 0.62 (6) | |

| MMI + PTU | 97.86 ± 0.31 (5) | 101.60 ± 1.01 (6) | |

| MMI + PTU + T3 | 95.2 ± 1.48 (6) | 100.29 ± 0.17 (6) |

Quantitive analysis of autoradiograms after in situhybridization for NSP and Oct-1 mRNA in the cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum of thyroid hormone-manipulated adult rats. Values shown represent mean + SEM (n) of film density (converted to % controls ± CV) over the cortex, hippocampus, or cerebellum.

* Significantly different from control euthyroid rats receiving saline injections (p < 0.05).

** Significantly different from control euthyroid rats receiving saline injections (p < 0.01).

Subfields of Ammon's horn.

DISCUSSION

The present studies are the first to demonstrate that thyroid hormone can affect gene expression in the fetal rat brain. Moreover, because we manipulated thyroid status of pregnant rats before the onset of fetal thyroid function, our data clearly demonstrate that thyroid hormone specifically of maternal origin affects the expression of these genes. Considering recent observations that maternal thyroid hormone reaches the fetus (Vulsma et al., 1989; Contempre et al., 1993) and that children born to pregnant women with untreated hypothyroidism exhibit measurable neurological deficits (Haddow et al., 1999; Pop et al., 1999), our data strongly indicate that thyroid hormone of maternal origin affects fetal brain development by regulating the expression of specific genes.

Using differential display, we identified 11 putative thyroid hormone-responsive genes in the fetal brain using only eight primer pairs. Thus, a large number of genes expressed in the fetal brain may be affected by maternal thyroid hormone. Differential display is known to generate false-positives, as do other “subtractive” hybridization methods designed to identify differentially expressed genes (Wan and Erlander, 1997; Ledakis et al., 1998). However, only one of three genes chosen for further analysis was a false-positive. This success rate may have been caused in part by the anatomical screen used to determine whether genes identified by differential display were expressed in brain areas containing TRs. Although nearly all of the gene fragments generated from the differential display were selectively expressed in brain areas and in organs that are responsive to thyroid hormone (Fig. 1), the genes chosen for further analysis were the most abundant and selectively expressed in TR-containing brain regions.

In principle, thyroid hormone of maternal origin could affect the expression of genes in the fetal brain by a direct action or by various indirect actions. However, several features of the present results suggest that maternal thyroid hormone affects gene expression by a direct action. First, the dose of thyroid hormone given to the dam did not produce supraphysiological levels of T4 in maternal blood. Therefore, the observed effects were not caused by thyrotoxic effects of thyroid hormone. Second, the single injection of T4 produced rapid, transient, and selective effects on gene expression in the fetal brain. The abundance of the NSP mRNA was suppressed within 36 hr, whereas that of Oct-1 mRNA was elevated within 12 hr. These effects were observed only in the cortex, not in the thalamus, and 6C was unaffected in both brain regions. In contrast, nonspecific or metabolic effects of thyroid hormone would more likely produce similar effects on the abundance of various genes and would not likely be limited to specific brain regions. Finally, we clearly demonstrated that NSP and Oct-1 expression can be regulated by T3 in the adult brain. Therefore, the effects of thyroid hormone on the expression of these two genes is not dependent on the maternal system or on injecting T4. Taken together, these data provide strong support for the concept that thyroid hormone of maternal origin can directly affect the expression of genes in the fetal brain.

Considering the evidence that thyroid hormone exerts a direct action on the expression of NSP and Oct-1, it was surprising that the administration of MMI did not affect their expression in the fetal brain, as measured by in situ hybridization. In the case of NSP, this may be related to the transcript-specific regulation by thyroid hormone. Specifically, the NSP fragment amplified in the differential display hybridized to two transcripts, a 1.5 kb transcript designated NSP-C and a 3.5 kb transcript designated NSP-A (van de Velde et al., 1994b; Ninkina et al., 1997). Northern analysis of RNA extracted from fetuses derived from MMI-treated dams showed that T4 suppressed only NSP-A mRNA. Because NSP-A expression is much lower than that of NSP-C but our probe hybridized to both transcripts, we may not have detected the selective effects of MMI on NSP-A expression. Evaluation of the same tissues with probes specific for NSP-A and NSP-C has confirmed this interpretation (A. L. S. Dowling, unpublished observations).

It must be noted, however, that hypothyroxinemia itself induces a number of compensatory mechanisms that ameliorate the consequences of low thyroid hormone levels in the fetal brain. These compensatory mechanisms may account for the unremarkable effects of MMI on the expression of NSP and Oct-1. For example, thyroid hormone uptake into tissues is enhanced in hypothyroid animals (Everts et al., 1994a,b,1995; Moreau et al., 1999), as is the conversion of T4 to T3 in fetal tissue (Ruiz de Ona et al., 1988; Calvo et al., 1990). We observed the effects of these compensatory mechanisms in that MMI-treated dams exhibited elevated T4 and suppressed TSH for a shorter duration after a single injection of T4. In the original differential display, we eliminated the potential confounding effects of compensatory mechanisms by comparing RNA pools extracted from fetuses derived from thyroidectomized dams only. Therefore, conditions under which genes were identified in the differential display represented only a subset of conditions tested in our follow-up studies.

The functional characteristics of NSP and Oct-1 may provide insight into thyroid hormone effects on the prenatal brain. NSP is a neuron-specific protein (Wieczorek and Hughes, 1991) integrated into the endoplasmic reticulum (van de Velde et al., 1994a,b), and its expression is correlated with neuronal differentiation (Hens et al., 1998). NSP mRNA is localized to the axonal pole of neuronal cell bodies (Baka et al., 1996; Ninkina et al., 1997) and may play a role in protein packaging and/or trafficking (Senden et al., 1996). As shown here, expression of NSP appears to be regionally and developmentally regulated. Overall, the abundance of NSP mRNA declines during development in all areas studied. However, NSP expression is robust in both the hippocampus and the cortex throughout development. In these areas, NSP expression is consistently high from GD14, the earliest time evaluated, to adulthood. At early developmental stages, NSP mRNA appears to be more abundant in the intermediate zone of the cortex and less abundant in the periventricular zone. As the brain matures and cortical layers develop, NSP expression in the cortex takes on a laminar appearance. The regulation of NSP-A by thyroid hormone during early cortical development and its differential expression in the intermediate zone of the GD16 cortex supports the concept that NSP is involved in neuronal differentiation and that this role is modulated by thyroid hormone.

Oct-1 is a POU-domain protein (He et al., 1989; Treacy and Rosenfeld, 1992), named for the initial genes identified within this family, Pit-1, Oct-1/2, and Unc-86. Downregulation of Oct-1 expression is associated with cell cycle arrest and differentiation (Lakin et al., 1995), suggesting a role for Oct-1 in proliferation. Like NSP, the expression of Oct-1 appeared to be regionally and developmentally regulated, and the abundance of Oct-1 mRNA declined during brain development. In contrast to NSP, Oct-1 mRNA was detected both within and outside the nervous system and in early development was selectively expressed in the periventricular zone of the cortex. This zone contains proliferating neurons (Caviness et al., 1995) that express only TRβ1 (Bradley et al., 1992). Because Oct-1 has been shown to stimulate TRβ1 expression (Nagasawa et al., 1997), thyroid hormone may act through TRβ1 to enhance Oct-1 expression and maintain TRβ1 expression in these proliferating neurons. Both TRβ1 (Bradley et al., 1992) and Oct-1 expression diminish once these neurons leave the ventricular zone and begin to differentiate.

It is interesting to note that both NSP and Oct-1 expression retained their responsiveness to thyroid hormone in the adult brain. However, NSP expression was affected by thyroid hormone only in the hippocampus where it was enhanced by hypothyroidism. In contrast, Oct-1 expression was suppressed by thyroid hormone in both the cortex and the hippocampus. Considering that the specific effect of thyroid hormone on gene expression may depend on the cofactor recruited to the hormone receptor complex (Koenig, 1998), the change in direction of regulation of Oct-1 by thyroid hormone during development may be related to developmental changes in coactivator and corepressor expression. In addition, the retention of thyroid hormone responsiveness in adulthood demonstrates that these genes do not exhibit a “critical period” of thyroid hormone sensitivity. Finally, the observation that chemical thyroidectomy does not fully abolish Oct-1 expression suggests that NSP and Oct-1 expression are not fully dependent on thyroid status, but their expression is modulated nonetheless.

In conclusion, these studies show that thyroid hormone of maternal origin can selectively regulate the expression of genes in the fetal brain. Furthermore, these genes may retain their sensitivity to thyroid hormone in the adult brain. One can reasonably speculate that maternal thyroid hormone could influence gene expression in the fetal brain by a direct mechanism and various indirect mechanisms. Our data support the concept that thyroid hormone regulates the expression of NSP and Oct-1 by a direct action. Our use of differential display in combination with an acute administration of a physiological dose of thyroid hormone may have enhanced our ability to identify genes directly regulated by thyroid hormone.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants ES8333 and AA10418 and a Healey Endowment grant to R.T.Z. We are grateful to Drs. Lawrence Schwartz, Michaela Heeb, Sandra Petersen, Geert De Vries, and Christine Wagner for comments on early versions of this manuscript, as well as to anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. R. Thomas Zoeller, Biology Department, Morrill Science Center, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003. E-mail:tzoeller@bio.umass.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altman J, Bayer SA. Atlas of prenatal rat brain development. CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baka I, Ninkina N, Pinon L, Adu J, Davies A, Georgiev G, Buchman V. Intracellular compartmentalization of s-rex/NSP mRNAs in neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1996;7:289–303. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1996.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernal J, Pekonen F. Ontogenesis of the nuclear 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine receptor in the human fetal brain. Endocrinology. 1984;114:677–679. doi: 10.1210/endo-114-2-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boulder Committee. Embryonic vertebrate central nervous system: revised terminology. Anat Rec. 1970;166:257–262. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091660214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley DJ, Young WS, Weinberger C. Differential expression of alpha and beta thyroid hormone receptor genes in rat brain and pituitary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7250–7254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley DJ, Towle HC, Young WS. Spatial and temporal expression of alpha- and beta-thyroid hormone receptor mRNAs, including the beta-2 subtype, in the developing mammalian nervous system. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2288–2302. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-06-02288.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calvo R, Obregon MJ, Ruiz de Ona C, Escobar del Rey F, Morreale de Escobar G. Congenital hypothyroidism, as studied in rats. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:889–899. doi: 10.1172/JCI114790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao XY, Jiang XM, Dou ZH, Murdon AR, Zhang ML, O'Donnell K, Ma T, Kareem A, DeLong N, Delong GR. Timing of vulnerability of the brain to iodine deficiency in endemic cretinism. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412293312603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caviness VS, Takahashi T, Nowakowski RS. Numbers, time and neocortical neuronogenesis: a general developmental and evolutionary model. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:379–383. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93933-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chopra IJ. Nature, source, and relative significance of circulating thyroid hormones. In: Braverman LE, Utiger RD, editors. Werner and Ingbar's the thyroid, Ed 7. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 1996. pp. 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Contempre B, Jauniaux E, Calvo R, Jurkovic D, Campbell S, Morreale de Escobar G. Detection of thyroid hormones in human embryonic cavities during the first trimester of pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:1719–1722. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.6.8263162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeChiara TM, Brosius J. Neural BC1 RNA: cDNA clones reveal nonrepetitive sequence content. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2624–2628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dussault JH, Ruel J. Thyroid hormones and brain development. Annu Rev Physiol. 1987;49:321–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.49.030187.001541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyess EM, Segerson TP, Liposits Z, Paull WK, Kaplan MM, Wu P, Jackson IMD, Lechan RM. Triiodothyronine exerts direct cell-specific regulation of thyrotropin-releasing hormone gene expression in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Endocrinology. 1988;123:2291–2297. doi: 10.1210/endo-123-5-2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Everts ME, Docter R, Moerings EPCM, van Koetsveld PM, Visser TJ, de Jong M, Krenning EP, Hennemann G. Uptake of thyroxine in cultured anterior pituitary cells of euthyroid rats. Endocrinology. 1994a;134:2490–2497. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.6.8194475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Everts ME, Visser TJ, Moerings EP, Docter R, van Toor H, Tempelaars AM, de Jong M, Krenning EP, Hennemann G. Uptake of triiodothyroacetic acid and its effect on thyrotropin secretion in cultured anterior pituitary cells. Endocrinology. 1994b;135:2700–2707. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.6.7988460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Everts ME, Visser TJ, Moerings EPCM, Tempelaars AMP, van Toor H, Docter R, de Jong M, Krenning EP, Hennemann G. Uptake of 3,5′,5,5′-tetraiodothyroacetic acid and 3,3′,5′-triiodothyronine in cultured rat anterior pituitary cells and their effects on thyrotropin secretion. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4454–4461. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.10.7664665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falcone M, Miyamoto T, Fierro-Renoy F, Macchia E, DeGroot LJ. Evaluation of the ontogeny of thyroid hormone receptor isotypes in rat brain and liver using an immunohistochemical technique. Eur J Endocrinol. 1994;130:97–106. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1300097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferreiro B, Bernal J, Goodyer CG, Branchard CL. Estimation of nuclear thyroid hormone receptor saturation in human fetal brain and lung during early gestation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;67:853–856. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-4-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher D, Dussault J, Sack J, Chopra I. Ontogenesis of hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid function and metabolism in man, sheep, rat. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1977;33:59–107. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571133-3.50010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher DA. Hypothyroxinemia in premature infants: is thyroxine treatment necessary? Thyroid. 1999;9:715–720. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, Allan WC, Williams JR, Knight GJ, Gagnon J, O'Heir CE, Mitchell ML, Hermos RJ, Waisbren SE, Fais JD, Klein RZ. Maternal thyroid deficiency during pregnancy and subsequent neuropsychological development of the child. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:549–555. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908193410801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He X, Treacy MN, Simmons DM, Ingraham HA, Swanson LW, Rosenfeld MG. Expression of a large family of POU-domain regulatory genes in mammalian brain development. Nature. 1989;340:35–42. doi: 10.1038/340035a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hens J, Nuydens R, Geerts H, Senden NHM, Van de Ven WJM, Roebroek AMJ, van de Velde HJK, Ramaekers RCS, Broers JLV. Neuronal differentiation is accompanied by NSP-C expression. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;292:229–237. doi: 10.1007/s004410051054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koenig RJ. Thyroid hormone receptor coactivators and corepressors. Thyroid. 1998;8:703–713. doi: 10.1089/thy.1998.8.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koller KJ, Wolff RS, Warden MK, Zoeller RT. Thyroid hormones regulate levels of thyrotropin-releasing hormone mRNA in the paraventricular nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7329–7333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lakin ND, Palmer R, Lillycrop KA, Howard MK, Burke LC, Thomas NSB, Latchman DS. Down regulation of the octamer binding protein Oct-1 during growth arrest and differentiation of a neuronal cell line. Mol Brain Res. 1995;28:47–54. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)00183-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lazar MA. Thyroid hormone receptors: multiple forms, multiple possibilities. Endocr Rev. 1993;14:184–193. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-2-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lazar MA. Thyroid hormone receptors: update 1994. Endocr Rev Monogr. 1994;3:280–283. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lechan RM, Wu P, Jackson IMD, Wolfe H, Cooperman S, Mandel G, Goodman RH. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone precursor: characterization in rat brain. Science. 1986;231:159–161. doi: 10.1126/science.3079917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ledakis P, Tanimura H, Fojo T. Limitations of differential display. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;251:653–656. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leonard JL, Koehrle J. Intracellular pathways of iodothyronine metabolism. In: Braverman LE, Utiger RD, editors. Werner and Ingbar's the thyroid, Ed 7. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 1996. pp. 125–161. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang P, Pardee AB. Differential display of eukaryotic messenger RNA by means of the polymerase chain reaction. Science. 1992;257:967–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1354393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM. The RXR heterodimers and orphan receptors. Cell. 1995;83:841–850. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moreau X, Lejeune PJ, Jeanningros R. Kinetics of red blood cell T3 uptake in hypothyroidism with or without hormonal replacement, in the rat. J Endocrinol Invest. 1999;22:257–261. doi: 10.1007/BF03343553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagasawa T, Takeda T, Minemura K, DeGroot LJ. Oct-1, silencer sequence, and GC box regulate thyroid hormone receptor beta-1 promoter. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1997;130:153–165. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(97)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ninkina NN, Baka ID, Buchman VL. Rat and chicken s-rex/NSP mRNA: nucleotide sequence of main transcripts and expression of splice variants in rat tissues. Gene. 1997;184:205–210. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obregon MJ, Mallol J, Pastor R, Morreale de Escobar G, Escobar del Rey F. l-thyroxine and 3,5,3′-triiodo-l-thyronine in rat embryos before onset of fetal thyroid function. Endocrinology. 1984;114:305–307. doi: 10.1210/endo-114-1-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oppenheimer JH, Schwartz HL. Molecular basis of thyroid hormone-dependent brain development. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:462–475. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.4.0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic; San Diego: 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perez-Castillo A, Bernal J, Ferreiro B, Pans T. The early ontogenesis of thyroid hormone receptor in the rat fetus. Endocrinology. 1985;117:2457–2461. doi: 10.1210/endo-117-6-2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pop VJ, Kuijpens JL, van Baar AL, Verkerk G, van Son MM, de Vijlder JJ, Vulsma T, Wiersinga WM, Drexhage HA, Vader HL. Low maternal free thyroxine concentrations during early pregnancy are associated with impaired psychomotor development in infancy. Clin Endocrinol. 1999;50:149–155. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Porterfield SP, Hendrich CE. Tissue iodothyronine levels in fetuses of control and hypothyroid rats at 13 and 16 days gestation. Endocrinology. 1992;131:195–200. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.1.1611997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roebroek AJM, van de Velde HJK, Van Bokhoven A, Broers JLV, Ramaekers FCS, Van de Ven WJM. Cloning and expression of alternative transcripts of a novel neuroendocrine-specific gene and identification of its 135-kDa translational product. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13439–13447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roebroek AJM, Contreras B, Pauli IGL, Van de Ven WJM. cDNA cloning, genome organization, and expression of the human TRN2 gene, a member of a gene family encoding reticulons. Genomics. 1998;51:98–106. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruiz de Ona C, Obregon MJ, Escobar del Rey F, Morreale de Escobar G. Developmental changes in rat brain 5′-deiodinase and thyroid hormones during the fetal period: the effects of fetal hypothyroidism and maternal thyroid hormones. Pediatr Res. 1988;24:588–594. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198811000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scott HC, Sun GY, Zoeller RT. Prenatal ethanol exposure selectively reduces the mRNA encoding alpha-1 thyroid hormone receptor in fetal rat brain. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:2111–2117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Senden NH, Timmer ED, Broers JE, van de Velde HJ, Roebroek AJ. Neuroendocrine-specific protein C (NSP-C): subcellular localization and differential expression in relation to NSP-A. Eur J Cell Biol. 1996;69:197–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanaka T, Kuwano Y, Kuzumaki T, Ishidawa K, Ogata K. Nucleotide sequence of cloned cDNA specific for rat ribosomal protein L31. Eur J Biochem. 1987;162:45–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb10539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Treacy MN, Rosenfeld MG. Expression of a family of POU-domain protein regulatory genes during development of the central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1992;15:139–165. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.001035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van de Velde HJK, Roebroek AJM, Senden NHM, Ramaekers FCS, Van de Ven WJM. NSP-encoded reticulons, neuroendocrine proteins of a novel gene family associated with membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci. 1994a;107:2403–2416. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.9.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van de Velde HJK, Roebroek AJM, van Leeuwen FW, Van de Ven WJM. Molecular analysis of expression in rat brain of NSP-A, a novel neuroendocrine-specific protein of the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Brain Res. 1994b;23:81–92. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Versloot PM, van der Heide D, Schroder-van der Elst JP, Boogerd L. Maternal thyroxine and 3,5,3′-tri-iodothyronine kinetics in near-term pregnant rats at two different levels of hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 1998;138:113–119. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1380113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vulsma T, Gons MH, deVijlder J. Maternal-fetal transfer of thyroxine in congenital hypothyroidism due to a total organification defect of thyroid agenesis. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:13–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907063210103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wan JS, Erlander MG. Cloning differentially expressed genes by using differential display and subtractive hybridization. Methods Mol Biol. 1997;85:45–68. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-489-5:45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wieczorek DF, Hughes SR. Developmentally regulated cDNA expressed exclusively in neural tissue. Mol Brain Res. 1991;10:33–41. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(91)90053-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zoeller RT, Wolff RS, Koller KJ. Thyroid hormone regulation of messenger ribonucleic acid encoding thyrotropin (TSH)-releasing hormone is independent of the pituitary gland and TSH. Mol Endocrinol. 1988;2:248–252. doi: 10.1210/mend-2-3-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]