Abstract

Mutations in the Unc5h3 gene, a receptor for the netrin 1 ligand, result in abnormal migrations of both Purkinje and granule cells to regions outside the cerebellum and of granule cells to regions within the cerebellum. Because both Purkinje and granule cells express this molecule, we sought to determine whether one or both of these cell types are the primary target of the mutation.

Chimeric mice were made between wild-type ROSA26 transgenic mouse embryos (whose cells express β-galactosidase) andUnc5h3 mutant embryos. The resulting chimeric brains exhibited a range of phenotypes. Chimeras that had a limited expression of the extracerebellar phenotype (movement of cerebellar cells into the colliculus and midbrain tegmentum) and the intracerebellar phenotype (migration of granule cells into white matter) had a normal-appearing cerebellum, whereas chimeras that had more ectopic cells had attenuated anterior cerebellar lobules. Furthermore, the colonization of colliculus and midbrain tegmentum by cerebellar cells was not equivalent in all chimeras, suggesting different origins for extracerebellar ectopias in these regions.

The granule cells of the extracerebellar ectopias were almost entirely derived from Unc5h3/Unc5h3 mutant embryos, whereas the ectopic Purkinje cells were a mixture of both mutant and wild-type cells. Intracerebellar ectopias in the chimera were composed exclusively of mutant granule cells. These findings demonstrate that both inside and outside the cerebellum, the granule cell is the key cell type to demarcate the boundaries of the cerebellum.

Keywords: mouse, cerebellum, Purkinje cells, rostral cerebellar malformation, rcm, neuronal migration, neurological mutant mice

The molecular dissection of compartments in the CNS has made impressive strides of late (Rubenstein et al., 1994; Lee and Jessell, 1999); however, the mechanisms that control the delineation of regions within those compartments (i.e., subcompartments) remain unknown. For example, how are the cells of the hippocampal formation or cerebellar cortex constrained to form the structures that are later invariably identified as hippocampus or cerebellum?

Recent studies of the mouse mutation rostral cerebellar malformation [rcm (Lane et al., 1992), now renamed Unc5h3] have yielded important information on the control of the formation of subcompartment boundaries. Mice homozygous for the Unc5h3mutation have cerebellar granule and Purkinje cells within the inferior colliculus (IC) and midbrain tegmentum that are attributable to an apparent disruption of cerebellar boundaries (Ackerman et al., 1997;Przyborski et al., 1998). Ectopic granule cells are also present in the cerebellar white matter, below the internal granular layer (IGL) inUnc5h3 mutant mice. The mutation in these mice was shown to be in a family member of the vertebrate homologs of theCaenorhabditis elegans pathfinding gene Unc5(Ackerman et al., 1997). As predicted by genetic evidence from C. elegans, UNC5H3 binds netrin 1 in vitro (Leonardo et al., 1997). There is also evidence that a netrin signal is available to developing cells of the cerebellar anlage (Przyborski et al., 1998).

Both granule cell neuroblasts and Purkinje cells expressUnc5h3 during their egress from the primary germinal epithelium and subsequent development (Ackerman et al., 1997;Przyborski et al., 1998). Thus either the granule cell precursors or the Purkinje cells, or both, are the likely responders to the signal that formats the cytoarchitectural boundaries in the cerebellum. It has been suggested that the Unc5h3/Unc5h3 defect is caused by a failure of Purkinje cell migration and the subsequent effects of Purkinje cells on the migration of granule cell neuroblasts (Eisenman and Brothers, 1998). However, it has also been shown that the ectopic migration of Unc5h3/Unc5h3 granule cell neuroblasts appears to precede the ectopic migration of Purkinje cells, suggesting that the granule cell is the regulator of the mutant phenotype (Przyborski et al., 1998). Alternatively, both cell types may have an interdependent relationship in the readout of the mutant phenotype.

We have used experimental murine chimeras to determine the cellular target of the Unc5h3 mutation as well as to explore howUnc5h3 regulates cerebellar development. By examining the genotype of cells in phenotypically mutant locations, we find that Purkinje cells cross cerebellar boundaries regardless of their genotype, whereas ectopic granule cells are almost completely of the mutant genotype. Thus, the granule cell neuroblast is the pioneer cell in establishing cerebellar boundaries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and generation of experimental murine chimeras. Unc5h3 and ROSA26 mice were used from the colonies maintained at the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). TheUnc5h3 mutation (termedUnc5h3rcmTgN(Ucp)1.23Kz) arose at the Jackson Laboratory as an insertional event from a transgenic experiment (Ackerman et al., 1997). The described phenotypes of theUnc5h3 mutant are inherited in a recessive manner, with no effects observed in heterozygous littermates. Behaviorally,Unc5h3/Unc5h3 mice exhibit a mild form of ataxia (Ackerman et al., 1997; Eisenman and Brothers, 1998). HomozygousUnc5h3 females can conceive and bear young.Unc5h3/Unc5h3 males exhibit difficulties in breeding, although homozygous mutant males have sired litters in our colony. For the purposes of the present experiments, the mutant component of the chimeras was obtained by mating homozygous Unc5h3 females with +/Unc5h3 males to generate either heterozygous or homozygous embryos.

The Gtrosa26 (ROSA26) mouse was the wild-type component of the chimera, and the strain was used to mark cell genotype in chimeras. The ROSA26 mouse has a β-galactosidase (β-gal) construct (Friedrich and Soriano, 1991) expressed in all neuronal and glial cell types within the cerebellum (our unpublished observations). The +/+ component of the chimera was generated by homozygous matings of ROSA26 females with ROSA26 males. All mice were maintained at either the Jackson Laboratories or the University of Tennessee Animal Care Facility. The guidelines of the respective Animal Care and Use Committees were followed.

Chimeric mice were generated in a manner that has been described previously (Goldowitz and Mullen, 1982a; Goldowitz, 1989). Single, four- to eight-cell ROSA26 embryos were cultured with singleUnc5h3 embryos in mini-wells created by a Hungarian darning needle (Wood et al., 1993). The embryos that successfully fused were then implanted into the uterine horn of pseudo-pregnant host B6CBAF1 females.

Mice (>60 d of age) were intracardially perfused over a 20 min time period with room temperature saline and 4% paraformaldehyde fixative in 0.1 m phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The brains were dissected out of the skull and placed in 0.1 m phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Before sectioning, the brains were infiltrated with 30% sucrose in the same buffer to act as a cryoprotectant. The brains were sectioned in the sagittal plane on a cryostat at a thickness of 10–15 μm and mounted on Superfrost Plus slides.

Determination of Unc5h3 genotype in chimeric mice. Experimental murine chimeras were composed of either genetically +/Unc5h3 or Unc5h3/Unc5h3 cells. To determine the Unc5h3 genotype in each chimera, both phenotypic and expression analyses were performed. First, the brain phenotype was examined to determine whether ectopic cerebellar cells were present in the midbrain or brainstem. It was concluded that a genetically Unc5h3/Unc5h3 embryo contributed to the chimera if there were obvious populations of ectopic cells in these regions. Second, the expression of the Unc5h3 transcript was examined in Purkinje cells by in situ hybridization/autoradiography as described previously (Ackerman et al., 1997; Przyborski et al., 1998). Because theUnc5h3 transcript is expressed in adult wild-type Purkinje cells but is not expressed inUnc5h3/Unc5h3 Purkinje cells, the cerebellum of chimeras was determined to consist of Unc5h3/Unc5h3 cells if there were Purkinje cells that lacked overlying silver grains. Detailed analyses (see below) were restricted to chimeric brains that satisfied both genotyping criteria.

Identification of granule, Purkinje, and radial glia cells in chimeras. Three major cerebellar cell types were examined in the present analysis. The cerebellar granule cell was identified by its characteristic pattern of condensed chromatin on the inside of the nuclear envelope within a small round nucleus (Goldowitz and Mullen, 1982b). This was easily observed using a nuclear stain such as neutral red. Cerebellar Purkinje cells were specifically immunolabeled with an anti-calbindin antibody (from M. Celio, University of Fribourg) used at a dilution of 1:1000. Bergmann glial fibers and their Golgi epithelial cell bodies were immunolabeled with an anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody (Lipshaw/Immunon, Pittsburgh, PA) according to manufacturer's protocol.

Sections for immunohistochemistry were rinsed with PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBS/T), blocked with 2% nonfat dry milk, and incubated in the primary antibody overnight at room temperature. The following day, sections were rinsed, lightly fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde for 2 min, and processed for β-gal reactivity as described below. The third day, sections were rinsed and processed for standard avidin–biotin immunocytochemical reactions using the ABC kit from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Immunolabeling was visualized using 3.3′ diaminobenzidine hydrochloride (DAB) as the chromagen. In some experiments visualization of the immunolabeling was enhanced by adding nickel chloride to the chromagen (Soriano and Del Rio, 1991). Sections were counterstained with neutral red and dehydrated, and coverslips were applied with Permount. The brown immunoreactivity (marking Purkinje or radial glia cells), blue β-gal histochemistry (marking +/+ cells), and red nuclear staining (marking all cells) were mutually compatible, allowing us to analyze the phenotype and genotype of cells in each section.

Demonstration of cell genotype in chimeras using β-galactosidase histochemistry. Sections throughout the medial–lateral extent of the cerebellum were processed for the β-gal marker using the procedure of Oberdick et al. (1994) in which sections are incubated at 30–35°C overnight in 0.1% X-gal substrate (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). Select slides either were processed for immunocytochemistry (see above) or rinsed and counterstained with neutral red to identify and quantify labeled and unlabeled cells. Tissue was dehydrated and cleared in xylenes, and coverslips were applied with Permount.

To ensure that expression of the β-gal marker is not altered by theUnc5h3 phenotype, Unc5h3/Unc5h3 female mice were crossed with ROSA26 males, and the subsequent progeny were intercrossed to produce ROSA26/?;Unc5h3/Unc5h3 mice. These mice were processed as described above for the demonstration of β-gal activity in phenotypically mutant cells.

Determination of percentage chimerism. The allocation of wild-type and mutant Purkinje and granule cells was analyzed by determining the percentage chimerism within normally and abnormally positioned locations. Percentage chimerism was defined as the percentage of cells within an individual population that are genotypically Unc5h3. Purkinje and granule cells were quantified within the cerebellum proper and in ectopic populations in the colliculus. The cerebellum proper was subdivided into the anterior and posterior lobes using the primary fissure as the demarcation point, whereas the ectopic collicular populations were subdivided into regions that were adjacent or distant to the cerebellum. To estimate the percentage chimerism in the Purkinje cell population, all calbindin-immunopositive Purkinje cells within a given subdivision were counted. Purkinje cells were determined as genotypically +/+ if they possessed several blue puncta of β-gal reaction product and as genetically Unc5h3/Unc5h3 if they lacked β-gal reactivity. To estimate the percentage chimerism within the granule cell population, β-gal-positive and -negative cells were counted using a 40× objective within a field of granule cells. A field was defined as the entire population of granule cells within a boundary made by outlining the granule cell layer in a camera lucida drawing tube. In the cerebellum proper, the granule cells could either be situated within their normal location in the IGL proper or below the IGL in the white matter (see Figs. 1, 4). Outside the cerebellum, in the midbrain, granule and Purkinje cells were analyzed that contributed to the ectopic stream leading from the cerebellum proper into the inferior colliculus. The percentage chimerism was determined by dividing the number of labeled cells in an area by the total number of cells within the same area.

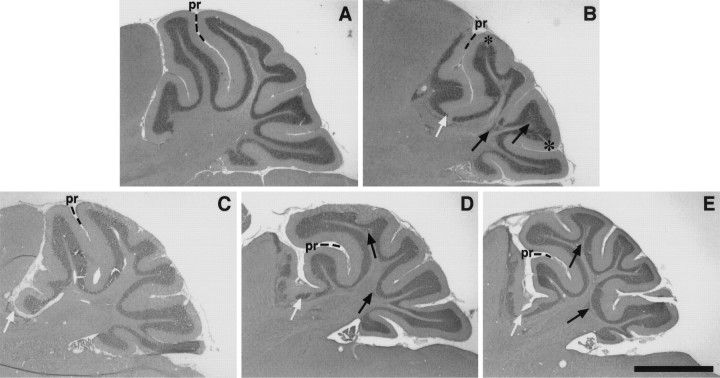

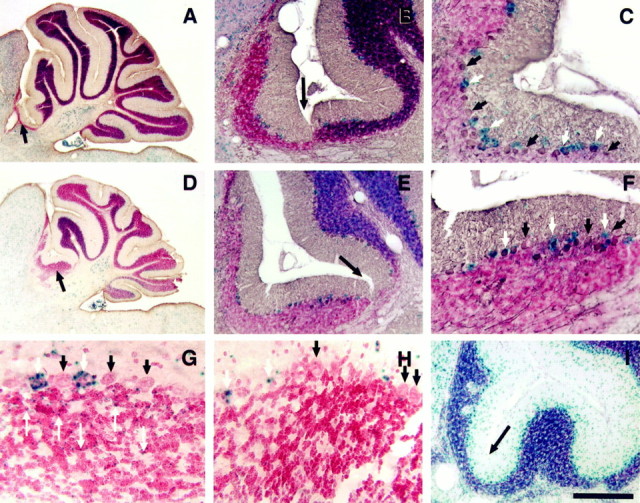

Fig. 1.

Chimeric cerebella exhibit a range of phenotypes. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained parasagittal sections through the superior cerebellar peduncle are shown from (A) an Unc5h3/+ control, (B) anUnc5h3/Unc5h3 animal, and (C–E) threeUnc5h3/Unc5h3↔ROSA26 chimeric animals (chimeras 1, 4, and 5, respectively). The primary fissure (pr) separates the anterior lobe (to theleft) from the posterior lobe (to theright). Ectopic cerebellar cells that have colonized the colliculus are to the left of thewhite arrows; black arrows indicate intracerebellar ectopias, and asterisks denote divots in the granule cell layer. Note that the phenotypes of chimeric cerebella are intermediate to wild-type andUnc5h3/Unc5h3 cerebella. Also note that the larger the extracerebellar ectopia, the more attenuated the cerebellum, particularly the anterior lobe. Scale bar, 700 μm.

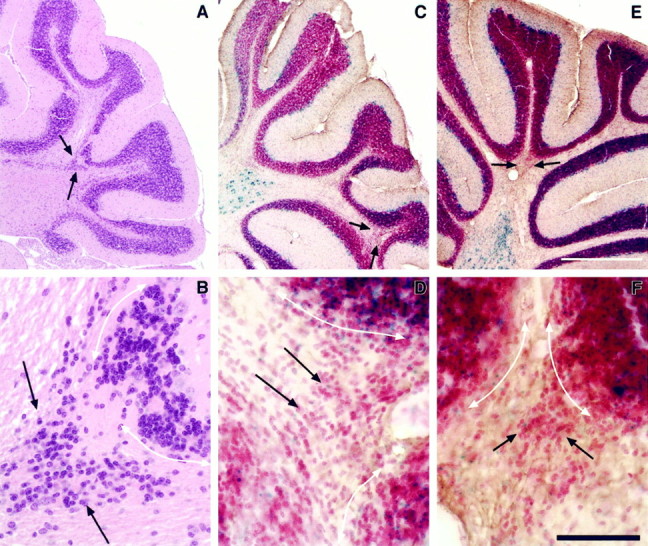

Fig. 4.

The Unc5h3 mutation acts intrinsic to intracerebellar granule cells for IGL boundary formation. Shown are parasagittal sections through lateral cerebella of anUnc5h3/Unc5h3 animal (A, B), chimera 5 (C, D), and chimera 2 (E, F). The posterior cerebellar region is shown. Thearrows in A, C, andE denote the region shown at higher magnification inB, D, and F, respectively. The white, double-sided arrows(B, D, and F) mark the boundary between the IGL and the white matter. Sections inA and B are stained with hematoxylin and eosin. In C–F, all cells are stained with neutral red, and wild-type (ROSA26) cells are labeled with the blue β-gal reaction product. As shown in D andF, the ectopic granule cells are virtually all ofUnc5h3/Unc5h3 origin. Scale bars:A, C, E, 400 μm;B, D, F, 50 μm.

The degree of ectopia within the midbrain (extracerebellar) and in the white matter (intracerebellar) was assessed and given a score between 1 and 5, where 1 was the phenotypically normal cerebellum and 5 was the phenotypically Unc5h3/Unc5h3 cerebellum. The scores were qualitatively estimated and based on the size of the ectopia (extracerebellar) and the number and size of ectopic clusters (intracerebellar).

Reconstruction of normal, mutant, and chimeric cerebella and determination of normal and ectopic cerebellar area. Quantitative measures of the normal and abnormal cerebellum were obtained by measuring the area occupied by normally positioned granule cells (in the internal granule layer), intracerebellar ectopic granule cells (granule cells in the white matter), and extracerebellar granule cells (in the midbrain tegmentum and inferior colliculus) inUnc5h3/Unc5h3 mutant chimeras, wild-type (+/Unc5h3↔ROSA26) chimeras, and Unc5h3/Unc5h3mutant mice. Sections from chimeric mutant, chimeric control, and mutant cerebella were assigned to bins (from 1 to 10) that were evenly spaced along the medial–lateral extent of the hemicerebellum. A representative section in each bin from each cerebellum was measured using a Neurolucida Imaging system attached to a Nikon microscope. Traces of whole cerebella were made using a 4× objective, and the granule cell territories were outlined using a 25× objective. The program calculated the area encompassed by the IGL, intracerebellar, and extracerebellar ectopic granule cells for each section.

RESULTS

Identification of Unc5h3/Unc5h3 chimeras

Mice homozygous for the Unc5h3 mutation are ataxic and have brain abnormalities, including ectopic granule and Purkinje cells in the midbrain and brainstem, and disruptions of the trilaminar structure of the cerebellar cortex (Lane et al., 1992; Ackerman et al., 1997). To determine the role of the Unc5h3 gene in cerebellar development and boundary formation,Unc5h3/Unc5h3↔ ROSA26 aggregation chimeras were produced and analyzed.

As detailed in Materials and Methods, the first criterion used to ascertain that chimeras were composed of Unc5h3/Unc5h3 cells was the presence of a mutant phenotype, similar to that found inUnc5h3 mutant mice. The principal mutant phenotype is the anterior invasion of the inferior colliculus and midbrain tegmentum by cerebellar cells (Figs.1B,2A). In addition to these extracerebellar ectopias, Unc5h3 mice have abnormalities in cell position within the cerebellum (Fig. 1B). Boundaries between the white matter and the IGL are often blurred by the presence of granule cells in the white matter. Additionally, small areas of the IGL are devoid of granule cells and overlying Purkinje cells. These granule cell “divots” are typically found in proximity to granule cell ectopias in the white matter (Figs. 1B,4A). The other obvious abnormality inUnc5h3 mutant mice is a reduction in the size of the cerebellum, primarily attributable to a loss of anterior cerebellar structures (Fig. 1A,B; Table 1). Thus, a chimeric brain that exhibited any or all of the above abnormalities met the first criterion for assigning the non-wild-type genotype asUnc5h3/Unc5h3.

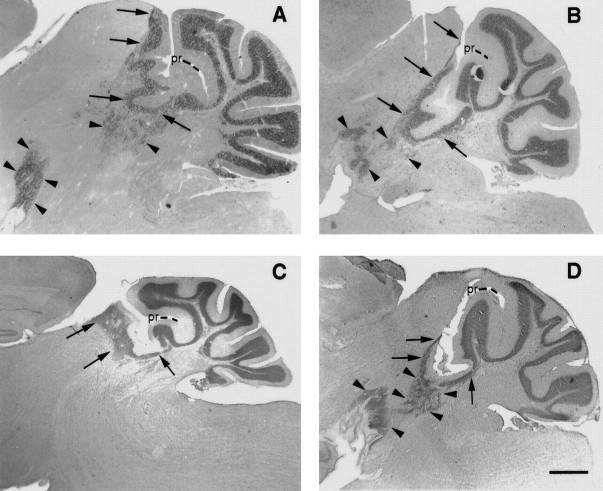

Fig. 2.

The inferior colliculus and midbrain tegmentum are differentially colonized by Unc5h3 mutant cells in the chimeric brain. Parasagittal sections through the lateral cerebellum of (A) an Unc5h3/Unc5h3mouse and (B–D) threeUnc5h3/Unc5h3↔ROSA26 chimeras (chimeras 5, 4, and 3, respectively). Ectopias in the inferior colliculus are indicated by arrows, and midbrain tegmentum ectopias are indicated by arrowheads. Note in the mutant (A) and chimera 5 (B) that there are extensive ectopias in both the inferior colliculus and midbrain tegmentum. In contrast, only the inferior colliculus ectopia is present in chimera 4 (C), whereas the midbrain tegmental ectopia predominates in chimera 3 (D). Sections are Nissl-stained. Scale bars: B–D, 250 μm; A, 400 μm.

Table 1.

Area (in μm2) occupied by granule cells in the cerebellum proper and ectopically in the midbrain tegmentum and colliculus (extracerebellar) and within the cerebellar white matter (intracerebellar) in mutant control (Unc5h3/Unc5h3;ROSA26), chimera control (+/+↔ROSA26) and experimental chimeric (Unc5h3/Unc5h3↔ROSA26) mice

| Animal | Area of IGL1-a | Area of extracerebellar ectopic granule cells1-b | Area of intracerebellar ectopic granule cells1-c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unc5h3 mutant; ROSA26 control1-d | 1.10 × 106 | 9.15 × 105 | 6.34 × 105 |

| Control chimeras | |||

| 6 | 2.20 × 106 | None | None |

| 7 | 1.92 × 106 | None | None |

| 8 | 1.98 × 106 | None | None |

| Experimental chimeras | |||

| 1 | 1.75 × 106 | 1.9 × 105 | None |

| 3 | 1.55 × 106 | 6.5 × 105 | 3.26 × 105 |

| 5 | 1.35 × 106 | 4.94 × 105 | 6.00 × 105 |

Mean area of the internal granule cell layer for each animal generated from two medial sections (bins 1 and 2) as described in Materials and Methods.

Mean area of cells in the extracerebellar ectopia for each animal generated from sampled sections in bins 5 and 6 as described in Materials and Methods.

Total area occupied by the granule cells in the intracerebellar ectopias for each animal generated from all 10 of the measured sections as described in Materials and Methods.

Mutant control generated in crosses betweenUnc5h3 and ROSA26 mice as described in Materials and Methods.

The second criterion used to confirm the presence ofUnc5h3/Unc5h3 cells was the presence of Purkinje cells that lacked Unc5h3 expression as detected by autoradiographicin situ hybridization. The number of silver grains over Purkinje cells was scored by an investigator (S.A.P.) naive to the results of the first criterion. In all cases in which theUnc5h3 component was genotyped as Unc5h3/Unc5h3according to criterion one, the Purkinje cell grain counts supported this assignment, i.e., there were numerous unlabeled Purkinje cells (data not shown).

Using these criteria, we identified 5 Unc5h3/Unc5h3↔ROSA26 chimeras. All five of these homozygous mutant chimeras had normal motor behavior and gave no overt clues as to their genetic status.

Chimeric Unc5h3/Unc5h3 cerebella exhibited a range of phenotypes

Although the Unc5h3/Unc5h3 cerebellum lacked the anterior lobules of the mediolateral cerebellum (Fig.1B), formation of these lobules in the fiveUnc5h3/Unc5h3 chimeras was variable (Fig.1C–E). For example, chimera 1 had a normal-appearing pattern of lobulation (Fig. 1C), whereas chimeras 4 and 5 had attenuated anterior cerebellar lobules (Fig.1D,E).

The size of the extracerebellar ectopia was also variable in chimeric mice. In larger ectopias, cerebellar cells were more organized and recapitulated typical cerebellar morphology with the appearance of granule cell, Purkinje cell, and molecular layers (Fig.1E). In lateral regions of the brain, large ectopias formed folia-like structures (Fig.2B,C). These ectopias were composed of numerous streams and pockets of cells that extended anteriorly as far as the border between the inferior and superior colliculi in the dorsal mesencephalon and to the interpeduncular fossa in the ventral mesencephalon. The middle cerebellar peduncle appeared to be a caudal boundary to these ventrally located, ectopic cerebellar neurons. In the larger ectopias, the ventralmost ectopic neurons formed a cell-dense cap over the interpeduncular fossa, with sparse streams of cells that connected to the other larger mass of ectopic cells that colonize the inferior colliculus (IC) (Fig. 2D, arrowheads). In other chimeric brains, the ectopic cells did not extend as far or colonize as much territory as these larger ectopias (Fig.2C).

The two masses of ectopic cerebellar neurons, one that formed in the colliculus and the other that formed in the midbrain tegmentum, appeared to have different origins. Two chimeras (4 and 3) exhibited reciprocal patterns of cerebellar ectopias. In chimera 4 there were large numbers of ectopic cells in the inferior colliculus, whereas a more limited set of ectopic cells existed in the midbrain tegmentum (Fig. 2C). Conversely, chimera 3 had fewer ectopic cells in the inferior colliculus but a large ectopia in the tegmentum (Fig.2D). A third, chimera 1, had only a small dorsal ectopia in the inferior colliculus, with no ectopic cells in the ventral midbrain tegmentum (Fig. 1C).

Intracerebellar ectopias, composed of granule cells within the white matter of the cerebellum proper, were also found in the chimeric cerebella although, they were less frequent than those found in nonchimeric Unc5h3/Unc5h3 mice (Fig. 1, compare black arrows in B with those in D andE; Tables 1, 2). The brain of chimera 1, which is composed of mainly wild-type cells, had a small but distinct extracerebellar ectopia, whereas it was difficult to distinguish any clear intracerebellar ectopias (Fig. 1C). This finding suggests that a much larger percentage of genotypically mutant cells is needed for the formation of these ectopias. Alternatively, the Unc5h3 gene may play more of a role in controlling the rostral–caudal boundaries of the cerebellum and be less important in the establishment of the deep boundary of the IGL.

Table 2.

Phenotype and percentage chimerismain Unc5h3/Unc5h3↔ROSA26 chimeras

| Chimera No. | Estimate of phenotype2-b | Within normal cerebellum (%) | In ectopias (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intracerebellar | Extracerebellar | GC-Ant2-c | GC-Post2-c | PC-Ant. | PC-Post. | PC | GC | |

| 1 | 1.52-d | 2.0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 70 (close) |

| 95 (far)2-e | ||||||||

| 2 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 20 | 35 | 30 | 50–60 | 90+ |

| 3 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 20 | 40 | 56 | 55 | 51 | 90+ |

| 4 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 30 | 40 | 37 | 45 | 33 | 90 |

| 5 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 45 | 65 | 33 | 42 | 34 | 90 |

GC-Ant., Granule cell-anterior; GC-Post., granule cell-posterior; PC-Ant., Purkinje cell-anterior; PC-Post., Purkinje cell-posterior.

The percentage of cells that areUnc5h3/Unc5h3.

Range: 1–5 with 1 = nonmutant phenotype while 5 = Unc5h3 mutant phenotype.

The percentage chimerism for the nonectopic granule cells is an estimate because of variations in distribution of granule cells across the cerebellum.

There were no obvious intracerebellar ectopias in this chimera but only hints that the border with the white matter may be disrupted in a few locations.

Close refers to cells that are near the edge of the normal cerebellum, and far refers to the granule cells that are more distal to the normal cerebellum.

A second type of intracerebellar abnormality in theUnc5h3/Unc5h3 mouse was the presence of acellular regions or divots in the IGL of the lateral cerebellum (Fig. 1B,asterisks). These divots occurred much less frequently than white matter ectopias but were always associated with the abnormal presence of granule cells in the white matter. In chimeras, these divots were also found associated with white matter ectopias. The occurrence of this sort of abnormality was proportional to the extent of the other mutant phenotypes found in each chimera (data not shown).

To quantify these differences, we analyzed areas of normally and ectopically placed cerebellar granule cells (Table 1). The medial cerebellum provided the most marked contrast in normal cerebellar area when comparing the Unc5h3/Unc5h3 mutant and normal cerebellum. On the other hand, most of the cerebellar ectopias in theUnc5h3/Unc5h3 mutant mouse were in the lateral cerebellum. Thus, measures were obtained from the appropriate regions to examine these phenotypes in three chimeric cerebella (1, 3, and 5). As shown in Table 1, chimeric cerebella had a range of mutant phenotypes that were intermediate between the Unc5h3/Unc5h3 mutant and wild-type controls.

The ROSA26 marking system and chimeric cerebella

The validity of the ROSA26 marker for distinguishing genotypically mutant and nonmutant cells in chimeric brains was established in control tissue. Previous reports have indicated that cells from the ROSA26 lineage can be identified by the presence of β-gal activity in chimeric animals (Zambrowicz et al., 1997). To ensure that the genotype of all cerebellar cell types could be reliably identified by the presence or absence of β-gal activity, cerebella from nonchimeric ROSA26 mice were examined. Both neurons and glial cells could be reliably labeled with the β-gal marker. Furthermore, all types of cerebellar neurons, including Purkinje and granule cells, expressed the β-gal marker. Additionally, to ensure that β-gal expression remained robust in ectopically located cerebellar cells, ROSA26 mice were mated with Unc5h3/Unc5h3 mice as described in Materials and Methods. In the ROSA26;Unc5h3/Unc5h3 brain, all ectopic cerebellar cells were β-gal positive (Fig.3I). Thus, in the chimeric brain, β-gal-negative cerebellar cells within both the cerebellum and midbrain were verified as genotypicallyUnc5h3/Unc5h3.

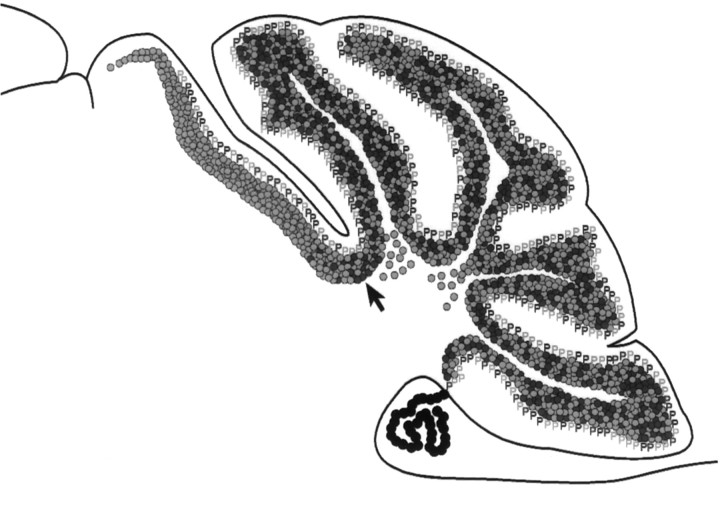

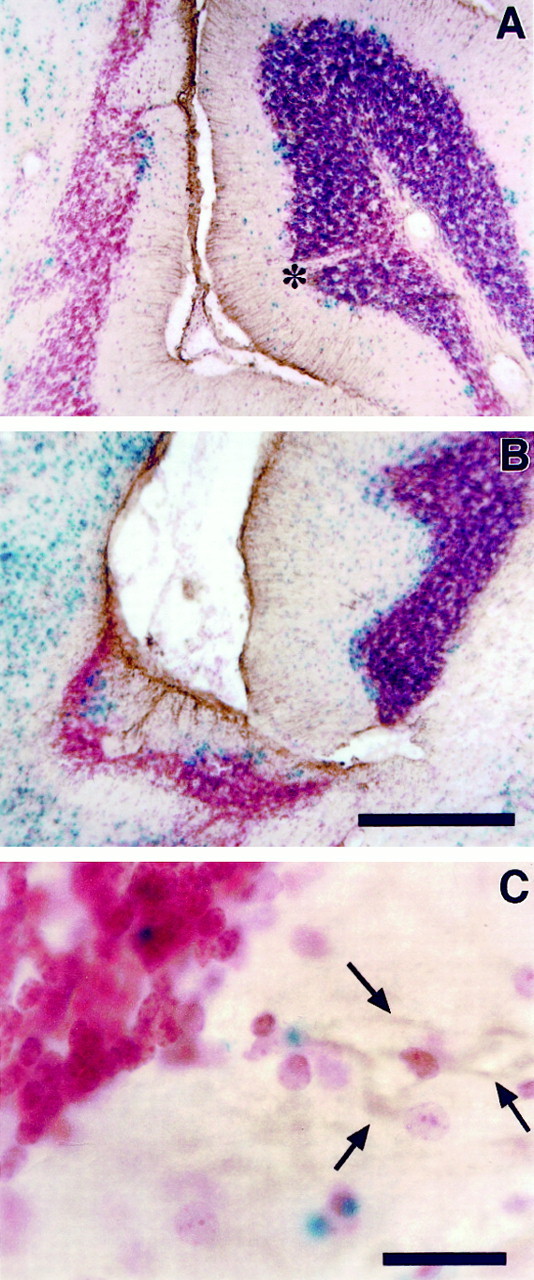

Fig. 3.

The Unc5h3 mutation acts in granule cells and not Purkinje cells. Parasagittal sections of the cerebellum and adjoining inferior colliculus are shown from chimera 2 (A–C) and chimera 5 (D–H). The boundary between normal cerebellum (to the right) and the extracerebellar ectopia (to theleft) is denoted by longer black arrowsin A, B, D,E, and I. Wild-type (ROSA26) cells are labeled with the blue β-gal reaction product (A–H). A section (I) from the mutant controlUnc5h3/Unc5h3;ROSA26 mouse demonstrates that all cerebellar cells (even those in ectopic positions) are β-gal positive. Purkinje cells are labeled with a brown reaction product denoting calbindin immunopositivity (A–F). White arrows designate wild-type Purkinje cells, whereas short black arrowsdesignate mutant Purkinje cells (C,F). G, H, High magnification images of extracerebellar ectopia in the colliculus from chimera 5 near (G) and distal (H) to the normal cerebellum. The Purkinje cells are denoted as above. Thin, long arrows point to the granule cells that are of wild-type origin (ROSA26 positive) in the ectopia. Note that although there are a limited numbers of wild-type granule cells in the ectopia proximal to the cerebellum, there are virtually no wild-type granule cells in the ectopia distal to the normal cerebellum. All sections were counterstained with neutral red allowing the visualization of unlabeled, mutant granule cells. Thus, although the ectopic Purkinje cells are a mixture of genotypically mutant and wild-type cells, the ectopic granule cells are mainly all of the mutant genotype. Scale bars: A, D, 600 μm;B, E, I, 150 μm;C, F, 75 μm; G, H, 24 μm.

To establish a baseline for the analysis of mutant chimera brains, we examined the general distribution of cells from the Unc5h3and ROSA26 lineages in +/Unc5h3↔ROSA26 chimeras. Genetically ROSA26 Purkinje cells were relatively evenly distributed throughout the rostral-to-caudal extent of the chimeric cerebellum. On the other hand, ROSA26 granule cells appeared to preferentially be localized to the anterior lobules of the chimeric cerebellum (Fig.3D). On average, there was a ∼2:1 ratio of the percentage of ROSA26 to +/Unc5h3 granule cells in the anterior lobules compared with the posterior lobules (data not shown). This skewed allocation of granule cells is reminiscent of the allocation of granule cells in intraspecies chimeras (Goldowitz, 1989).

Ectopic Purkinje cells were a mixture of mutant and wild-type genotypes

Like Unc5h3/Unc5h3 mice, Purkinje cells, as marked by calbindin immunopositivity, were present in the inferior colliculus and midbrain tegmentum of chimeric mice. In the inferior colliculus these cells were always present with neighboring granule cells. However, at the farthest extent of the ectopic expansion, ectopic granule cells were found without accompanying Purkinje cells. In fact there was the impression that a threshold number of granule cells needed to be present in the collicular ectopia before Purkinje cells colonized that area. In contrast, rare isolated sets of Purkinje cells could be found without accompanying granule cells in the midbrain tegmentum of chimeras. These Purkinje cells were never at the leading edge of the ectopia, suggesting that these cells did not pioneer the formation of the ectopia.

As shown in Figure 3, C and F, both genotypically ROSA26 Purkinje cells and genotypically Unc5h3/Unc5h3Purkinje cells were found within the inferior colliculus. There was no preferential localization of the two genotypes of Purkinje cells along the extent of the ectopia. Similar percentages ofUnc5h3/Unc5h3 Purkinje cells in the cerebellum proper and ectopic inferior colliculus were found, indicating that mutant and wild-type Purkinje cells had an equal ability to cross the boundary into extracerebellar territory (Table 2). A similar distribution of wild-type and mutant Purkinje cells was also found in the midbrain tegmentum ectopias of chimeras (data not shown).

The vast majority of ectopic granule cells were of theUnc5h3/Unc5h3 genotype

Granule cells were typically the only cerebellar cell type at the farthest reaches of extracerebellar ectopias in chimeric brains, which indicates, as previously suggested by studies of Unc5h3mutant embryos (Przyborski et al., 1998), that these cells comprised the leading edge of the migrating ectopic stream of neurons. Moreover, as seen in Figure 3, genotypically Unc5h3/Unc5h3 granule cells predominated in the extracerebellar ectopias, whereas almost all wild-type granule cells stopped at the rostral cerebellar boundary (Fig.3A,B,D,E). However, some wild-type cells were found in regions of the IC that were closest to the cerebellar boundary (Fig. 3G). At more distal reaches of the ectopias, wild-type granule cells were not found (Fig.3H). When the percentages of genotypicallyUnc5h3/Unc5h3 granule cells in both the cerebellum proper and the ectopic IC were estimated, these percentages differed dramatically (Table 2). In the ectopic location, ∼90% or more of the granule cells were genotypically Unc5h3/Unc5h3, even in chimeric brains in which the percentage within the cerebellum itself was <50% (Table 2). Similarly, ectopic granule cells in the midbrain tegmentum of chimeras were composed almost entirely of mutant cells (data not shown).

Intracerebellar granule cell ectopias were composed almost completely of genotypically Unc5h3/Unc5h3 cells (Fig.4C–F), and divots occurred in the midst of folia among predominantly wild-type granule cells (Fig. 5A). It is interesting to note that the wild-type cells do not migrate laterally to fill the divot that is presumably created by the migration ofUnc5h3/Unc5h3 granule cells into the white matter.

Fig. 5.

Both genotypically mutant and wild-type radial glial cells are found in extracerebellar ectopias. Parasagittal sections through chimera 5 (A) and chimera 1 (B) were immunostained with an anti-GFAP antibody to label glial cells and counterstained with neutral red. Wild-type cells have one or more blue dots after the β-gal reaction. In both the extracerebellar ectopia (to the left) and the normal cerebellum (to the right), GFAP-positive cells are observed that possess the morphology of radial glial cells typical of the cerebellum (A, B). InC, GFAP-positive fibers (arrows) can be traced back to a genotypically normal glial cell soma in the ectopia. Also note the presence of a cell-free divot (asterisk) in a largely wild-type folia. Scale bars: A, B, 150 μm; C, 22 μm.

Ectopic radial glia were a mixture of mutant and wild-type genotypes

An anti-GFAP antibody was used to identify glial cell bodies and their processes. In the normal cerebellum, radial glia processes span the distance between the Purkinje cell layer and the pial surface. In contrast, the subpial glial population of the native inferior colliculus is oriented parallel to the pial surface. The morphology of the glia in ectopic regions of chimeric brains was variable, depending on the degree of colonization by cerebellar cells. In chimeras with less organized and less granule cell-populated collicular ectopias, the glial fibers were thickened and lacked clear radial processes (Fig.5B). However, in the colliculus of chimeras with greater contributions of ectopic cells, the arrangement and morphology of glial processes were similar to that seen in the normal cerebellum (Fig.5A). The determination of whether the glial cells are genotypically mutant or wild type relies on the double-staining with both β-gal and GFAP. In this double-labeling method, glia do not stain particularly well for β-gal. However, in some preparations, ROSA26 (wild-type) radial glia cells were observed in the ectopia (Fig.5C), suggesting that the genotype of glia was irrelevant to the occurrence of ectopic cells.

DISCUSSION

The granule cell is the pioneer neuron in establishing cerebellar boundaries

The molecular mechanisms by which neurons commence and cease their migration are beginning to be understood through the analysis of naturally occurring and induced mutations of the mouse genome. TheUnc5h3 gene appears to be a key player in cerebellar neuronal migration, as demonstrated by the phenotype of mice with mutations in this gene.

One of the key insights that the Unc5h3 mutant reveals is the role of cells and molecules in determining the regional boundaries that are specific to the cerebellum. What are the means by which the rostral and ventral boundaries of the cerebellum are established? Both Purkinje cells and granule cells express the Unc5h3 gene, and therefore either one or both cell types could be responsible for demarcating the cerebellar territory. Eisenman and Brothers (1998)proposed that like avian species, a subset of Purkinje cells in the mouse may be mesencephalic in origin. They hypothesized that the cellular deficit in Unc5h3 resides in the failure of this future mesencephalically derived Purkinje cell population to properly colonize the anteromedial cerebellum (an anterior to posterior migratory deficit). Alternatively, Przyborski et al. (1998) suggest that the Unc5h3 phenotype is the result of abnormal granule cell migration because they find ectopic cells in the brainstem at, but not before, embryonic day 13.5 (E13.5), concurrent with granule cell precursor migration from the rhombic lip.

Based on two findings from the analysis ofUnc5h3/Unc5h3↔ROSA26 chimeric brains, we identify theUnc5h3-expressing granule cell as the pioneer in establishing cerebellar boundaries (Fig.6). First, most of the granule cells that are found in extracerebellar regions are genotypicallyUnc5h3/Unc5h3. This indicates that wild-type granule cells successfully read the migratory stop signal and cease movement, whereasUnc5h3/Unc5h3 granule cells are unable to read this cue and continue migrating until they are stopped by another boundary. Second, in the chimeric environment, the equal representation of ectopically placed nonmutant and mutant Purkinje cells demonstrates that the abnormal migration of these cells does not depend on theUnc5h3 mutation and is a result of extrinsic factors. These extrinsic factors most likely arise directly or indirectly from the mutant granule cells. A direct interaction would be the granule cells actively attracting Purkinje cells. An indirect action would be simply the lack of a stop signal that the granule cells normally provide. Evidence for the latter possibility is found in theAtoh1−/−mouse, in which a total absence of EGL cells is accompanied by Purkinje cell movement into the inferior colliculus (Ben Arie et al., 1997) (T. Jensen and D. Goldowitz, unpublished observations).

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of the contribution of genotypically mutant (gray) and genotypically wild-type (black) granule cells (circles) and Purkinje cells (P) inUnc5h3/Unc5h3↔ROSA26 chimeric brains. Within the cerebellum itself (right of arrow), Purkinje cells and nonectopic granule cells are a mixture of both mutant and wild-type cells, whereas the granule cells within the intracerebellar ectopia are genotypically mutant. In extracerebellar ectopias (left of arrow), Purkinje cells remain a mixture of both mutant and wild-type cells, whereas granule cells are predominantly mutant.

We did find a small population of wild-type granule cells that participated in the formation of the extracerebellar ectopias. At least two possible explanations exist for this finding. First, ectopic Purkinje cells of either genotype may attract a small number of EGL cells (some of which are wild type in origin) into the ectopic stream. Second, these ectopic, wild-type EGL cells may be passively displaced within the stream of ectopic mutant cells. Whatever the mechanism underlying the presence of wild-type granule cells in these ectopias, it must be tempered with our results that these cells are only found a short distance past the normal cerebellar–collicular boundary and never extend into the more distal aspects of the ectopia.

Decision points in the migration of mitotically active EGL cells

Granule cell precursors are generated from a specialized portion of the ventricular epithelium, the germinal trigone. These precursors initially migrate in a dorsal direction and subsequently anteriorly and medially over the surface of the cerebellum to form the EGL (Miale and Sidman, 1961). In Unc5h3 chimeric mice there is evidence supporting the existence of two, independent decision points in the migration of cerebellar granule cells: (1) initially, when cells leave the germinal trigone to form the EGL, and (2) finally, at the anterior cerebellar boundary, when cells of the EGL have migrated to cover the surface of the cerebellum.

If the ectopic cells in Unc5h3 chimeras arose from misreading a signal at a single origin, then the degree of the ectopias in the chimeric brainstem and colliculus should be dependent solely on the degree of chimerism. In other words, the number of mutant granule cells present at that decision point would determine the extent of ectopias in both the midbrain tegmentum and the colliculus. However, we find that chimeras can exhibit opposite phenotypes with respect to the ectopic colonization of brainstem and colliculus (Fig. 2). Thus the opposing phenotypes seen in chimeras implicate the presence of two separable decision points in the migratory history of the granule cell.

It seems most likely that the granule cells responsible for reading the stop signals comprise the anterior cerebellar compartment. In the normal cerebellum, the first granule cell neuroblasts that leave the germinal trigone are those destined for the anterior–medial lobules (Goldowitz, 1989). In the early development of the Unc5h3mutant cerebellum (around E13), most cells go in the anteromedial direction, although a significant minority cannot read the posterior boundary signal and leave the cerebellar anlage, presumably giving rise to the ventral ectopias seen in midbrain tegmentum. At a much later date [postnatal day 0(P0)], another subpopulation of cells from the EGL fail to read the anterior stop signal and flow anteriorly into the inferior colliculus. Thus the primary extracerebellar defect involves cells from the anterior cerebellar compartment. This is in contrast to the intracerebellar defects (white matter ectopias and divots) that occur throughout the rostral–caudal extent of the lateral cerebellum, and therefore involves the inability of some granule cells, in all compartments of the lateral cerebellum, to read a stop signal.

A decision point in the migration of postmitotic granule cells

In restricted locations within the Unc5h3/Unc5h3 mutant cerebellum, the boundary between the white matter and the IGL is indistinct, with many granule cells found in the white matter directly below the IGL. This raises the interesting and as yet unanswered question: how are granule cells constrained within the IGL? The present study provides two interesting observations about these intracerebellar ectopias. First, in the Unc5h3/Unc5h3↔ROSA chimeric mice, the ectopic granule cells found within the white matter are only of theUnc5h3/Unc5h3 genotype. Second, the number of intracerebellar ectopias increases as the percentage ofUnc5h3/Unc5h3 cells increases. Both of these findings indicate that the intracerebellar granule cell ectopias are caused by the direct action of the mutant Unc5h3 gene on the cerebellar granule cell.

The mechanism by which these intracerebellar ectopias arise is unclear. White matter ectopias may be created by an exuberant migration of granule cells past the IGL/white matter border. However, within the disrupted Unc5h3/Unc5h3 cerebellum, a distinct IGL can be identified in many areas, demonstrating that only a small percentage of the granule cells are affected. Thus, although the presence of UNC5H3 is obviously one of the important factors that normally constrains granule cells within the IGL, clearly other factors also mediate this function.

Ligands for UNC5H3

UNC5H3 has been demonstrated to bind the secreted protein netrin 1 (Leonardo et al., 1997). Furthermore, netrin 1 (Ntn1) mRNA has been shown to be expressed in the median sulcus and basal plate of the fourth ventricle, juxtaposed to the developing cerebellum and the expression domains of Unc5h3 in the embryonic and early postnatal cerebellum (Przyborski et al., 1998). These data are consistent with netrin 1 providing a chemorepulsive cue forUnc5h3-expressing granule cells, thus determining the anterior and ventral boundary of the developing cerebellum. However, the examination ofNtn1−/−brains at P0 (the time when these animals die) does not reveal any obvious extracerebellar ectopias (J. Edgar and S. L. Ackerman, unpublished results).

There are several possible explanations for the lack of anUnc5h3-like phenotype inNtn1−/−mice. First, there is a residual expression of Ntn1transcripts in Ntn1-deficient animals (Serafini et al., 1996), and this limited expression may be sufficient for demarcation of the cerebellar boundaries. Second, the loss of netrin 1 in these animals may be compensated by an undiscovered netrin family member that also binds the UNC5H3 receptor. Finally, a molecule other than netrin 1 may serve as the in vivo ligand for UNC5H3.

The presence of genotypically Unc5h3/Unc5h3 granule cells in the cerebellar white matter of Unc5h3/Unc5h3↔ROSA26 chimeras implies the presence of a chemorepulsive molecule at the base of the IGL defining this cell layer. However, Ntn1 is detected only in the proliferative zone of the EGL of lateral regions of the postnatal cerebellum (Livesey and Hunt, 1997) (S. Przyborski and S. L. Ackerman, unpublished results), suggesting that an additional UNC5H3 ligand(s) is necessary for the establishment of IGL boundaries. Thus, these results suggest that, like other signaling molecules [e.g., a septal-derived factor and Slit (Hu and Rutishauser, 1996; Wu et al., 1999)], UNC5H3 may have a general role in the establishment of boundaries in the developing CNS.

Concluding remarks

Our chimeric analysis of the Unc5h3 mutation indicates that single cerebellar cells (members of the granule cell population) read a stop signal to format the ventral and anterior boundaries of the developing cerebellum. Furthermore, the formation of the internal granular layer also relies on the ability of granule cells to read a molecular stop signal, although this molecule may be different from the one that sets the anterior and ventral cerebellar boundaries. More generally, the Unc5h3 mutant mouse presents a fascinating mutation that highlights the possibility that a host of as yet undiscovered molecules (receptors and their ligands) serve as stop signals for migration throughout the CNS.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (NS35900) to S.L.A. and a CORE grant (CA34196) from the National Cancer Institute and The University of Tennessee College of Medicine and Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology. We thank Richard Cushing for technical assistance, Greg Martin and Justin Boyd for assistance in imaging, and Drs. Tom Gridley and Timothy O'Brien for their comments on this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Dan Goldowitz, Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, University of Tennessee, Memphis, 875 Monroe Avenue, Memphis, TN 38163. E-mail: dgold@nb.utmem.edu.

Dr. Przyborski's current address: Department of Biomedical Science, University of Sheffield, Western Bank, Sheffield, United Kingdom S10 2TN.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackerman SL, Kozak LP, Przyborski SA, Rund LA, Boyer BB, Knowles BB. The mouse rostral cerebellar malformation gene encodes an UNC-5-like protein. Nature. 1997;386:838–842. doi: 10.1038/386838a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben Arie N, Bellen HJ, Armstrong DL, McCall AE, Gordadze PR, Guo Q, Matzuk MM, Zoghbi HY. Math1 is essential for genesis of cerebellar granule neurons. Nature. 1997;390:169–172. doi: 10.1038/36579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenman LM, Brothers R. Rostral cerebellar malformation (rcm/rcm): a murine mutant to study regionalization of the cerebellum. J Comp Neurol. 1998;394:106–117. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980427)394:1<106::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedrich G, Soriano P. Promoter traps in embryonic stem cells: a genetic screen to identify and mutate developmental genes in mice. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1513–1523. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldowitz D. Cell allocation in mammalian CNS formation: evidence from murine interspecies aggregation chimeras. Neuron. 1989;3:705–713. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90239-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldowitz D, Mullen RJ. Granule cell as a site of gene action in the weaver mouse cerebellum: evidence from heterozygous mutant chimeras. J Neurosci. 1982a;2:1474–1485. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-10-01474.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldowitz D, Mullen RJ. Nuclear morphology of ichthyosis mutant mice as a cell marker in chimeric brain. Dev Biol. 1982b;89:261–267. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu H, Rutishauser U. A septum-derived chemorepulsive factor for migrating olfactory interneuron precursors. Neuron. 1996;16:933–940. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane PW, Bronson RT, Spencer CA. Rostral cerebellar malformation (rcm): a new recessive mutation on chromosome 3 of the mouse. J Hered. 1992;83:315–318. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KJ, Jessell TM. The specification of dorsal cell fates in the vertebrate central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:261–294. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leonardo ED, Hinck L, Masu M, Keino Masu K, Ackerman SL, Tessier Lavigne M. Vertebrate homologues of C. elegans UNC-5 are candidate netrin receptors. Nature. 1997;386:833–838. doi: 10.1038/386833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livesey FJ, Hunt SP. Netrin and netrin receptor expression in the embryonic mammalian nervous system suggests roles in retinal, striatal, nigral, and cerebellar development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1997;8:417–429. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miale IL, Sidman RL. An autoradiographic analysis of histogenesis in the mouse cerebellum. Exp Neurol. 1961;4:277–296. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(61)90055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oberdick J, Wallace JD, Lewin A, Smeyne RJ. Transgenic expression to monitor dynamic organization of neuronal development: use of the E. coli lacZ gene product, β-galactosidase. Neuroprotocols. 1994;5:54–62. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Przyborski SA, Knowles BB, Ackerman SL. Embryonic phenotype of Unc5h3 mutant mice suggests chemorepulsion during the formation of the rostral cerebellar boundary. Development. 1998;125:41–50. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubenstein JL, Martinez S, Shimamura K, Puelles L. The embryonic vertebrate forebrain: the prosomeric model. Science. 1994;266:578–580. doi: 10.1126/science.7939711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serafini T, Colamarino SA, Leonardo ED, Wang H, Beddington R, Skarnes WC, Tessier-Lavigne M. Netrin-1 is required for commissural axon guidance in the developing vertebrate nervous system. Cell. 1996;87:1001–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soriano E, Del Rio JA. Simultaneous immunocytochemical visualization of bromodeoxyuridine and neural tissue antigens. J Histochem Cytochem. 1991;39:255–263. doi: 10.1177/39.3.1671576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood SA, Allen ND, Rossant J, Auerbach A, Nagy A. Non-injection methods for the production of embryonic stem cell-embryo chimaeras. Nature. 1993;365:87–89. doi: 10.1038/365087a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu W, Wong K, Chen J, Jiang Z, Dupuis S, Wu JY, Rao Y. Directional guidance of neuronal migration in the olfactory system by the protein Slit. Nature. 1999;400:331–336. doi: 10.1038/22477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zambrowicz BP, Imamoto A, Fiering S, Herzenberg LA, Kerr WG, Soriano P. Disruption of overlapping transcripts in the ROSA beta geo 26 gene trap strain leads to widespread expression of beta-galactosidase in mouse embryos and hematopoietic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3789–3794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]