Abstract

The aim of the present study was to investigate the mechanisms underlying the desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors in the dorsal raphe and hypothalamus of serotonin (5-HT) transporter knock-out mice (5-HTT −/−). The density of 5-HT1A receptors in the dorsal raphe was reduced in both male and female 5-HTT −/− mice. This reduction was more extensive in female than in male 5-HTT −/− mice. 8-OH-DPAT-induced hypothermia was absent in female 5-HTT −/− and markedly attenuated in 5-HTT +/− mice. The density of 5-HT1A receptors also was decreased significantly in several nuclei of the hypothalamus, amygdala, and septum of female 5-HTT −/− mice. 5-HT1A receptor mRNA was reduced significantly in the dorsal raphe region, but not in the hypothalamus or hippocampus, of female 5-HTT +/− and 5-HTT −/− mice. G-protein coupling to 5-HT1A receptors and G-protein levels in most brain regions were not reduced significantly, except that Go and Gi1 proteins were reduced modestly in the midbrain of 5-HTT −/− mice. These data suggest that the desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors in 5-HTT −/− mice may be attributable to a reduction in the density of 5-HT1A receptors. This reduction is brain region-specific and more extensive in the female mice. The reduction in the density of 5-HT1A receptors may be mediated partly by reduction in the gene expression of 5-HT1A receptors in the dorsal raphe, but also by other mechanisms in the hypothalamus of 5-HTT −/− female mice. Finally, alterations in G-protein coupling to 5-HT1Areceptors are unlikely to be involved in the desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors in 5-HTT −/− mice.

Keywords: 5-HT1A receptors, 5-HT1A mRNA, 5-HT transporter knock-out mice, G-protein coupling, hypothermia, gender difference, autoradiography, competitive RT-PCR, in situhybridization

Increasing evidence suggests that the function of serotonin (5-HT) transporter is important in the regulation of emotional states. For example, polymorphisms in the 5′ regulatory region and intron 2 of the 5-HT transporter (5-HTT) gene, which affects 5-HTT expression, may be related to neuroticism and some affective disorders (Lesch et al., 1996; Mazzanti et al., 1998;MacKenzie and Quinn, 1999; Greenberg et al., 2000; Stoltenberg and Burmeister, 2000). Also, the 5-HTT is the target of a widely used class of antidepressant drugs: the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine (Prozac). The 5-HTT removes released 5-HT from serotonergic nerve terminals and along axons (Zhou et al., 1998). In doing so, the 5-HTT terminates the activation of postsynaptic 5-HT receptors by extracellular 5-HT. It is believed that the effects of 5-HTT on the regulation of emotion are mediated by adaptive changes in the serotonergic system induced by alterations in extracellular 5-HT concentration. Therefore, studying the mechanisms underlying the effects of 5-HTT on emotion will have a significant impact on our understanding of the etiology of psychiatric disorders and should help to develop better therapeutic approaches for psychiatric disorders.

5-HT1A receptors play a role in anxiety and probably also in depression. Previous studies showed that disruption of 5-HTT function either by chronic SSRIs or by knock-out of the 5-HTT gene produces a desensitization (decrease in physiological responses to the stimulation of 5-HT1A receptors) of 5-HT1A receptors in the hypothalamus and dorsal raphe nucleus (Le Poul et al., 1995; Li et al., 1996, 1997a, 1999;Blier et al., 1998). Behaviorally, 5-HTT knock-out mice (5-HTT −/− mice) are more anxious relative to 5-HTT +/+ mice (as examined by the elevated zero maze and light/dark box) (Murphy et al., 1999; C. Wichems, unpublished data). Interestingly, these behavioral alterations also are observed in 5-HT1A receptor knock-out mice (Heisler et al., 1998; Parks et al., 1998; Ramboz et al., 1998;Zhuang et al., 1999). These results suggest that desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors may play an important role in the effects of 5-HTT on emotion. In fact, several clinical studies have reported that the combined administration of 5-HT1A antagonists with SSRIs produces an earlier therapeutic effect than SSRIs alone, suggesting that desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors may contribute to the therapeutic effects of SSRIs. Therefore, studying the mechanisms underlying the desensitization of 5-HT1Areceptors induced by disruption of the function of 5-HTT should help us to understand the effects of 5-HTT on the regulation of emotion.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the mechanisms underlying the desensitization of 5-HT1Areceptors in 5-HTT mutant mice. Because the desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors can be attributable to reduction in the density or the G-protein coupling to 5-HT1A receptors, we examined the density of 5-HT1A receptors, their mRNA, and G-protein coupling. To determine whether the desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors is mediated by a decrease in the concentration of G-proteins that are coupled with 5-HT1A receptors, we also examined several G-proteins in various brain regions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

5-HTT mutant mice from a CD-1x129sv/ev background were created by homologous recombination as previously reported (Bengel et al., 1998). The 5-HTT mutant mice were from the F5 generation of backcross mating with CD1 mice and were 3–5 months of age, with body weights of 30–40 gm. The mice were housed in groups of four to five per cage in a light- (12 hr light/dark, lights on at 6 A.M.), humidity-, and temperature-controlled room. Food and water were available ad libitum. In all of the experiments, five to eight male or female mice, as noted, were included in each group. All animal procedures were approved by the National Institute of Mental Health Animal Care and Use Committee.

Materials

(+)8-OH-DPAT and (±)8-OH-DPAT [8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino)tetraline] were purchased from Research Biochemicals International (RBI, Natick, MA).125I-MPPI [4-(2′-methoxyphenyl)-1-[2′-[N-(2"-pyridinyl-)-iodo-benzamido]ethyl]piperazine] and 35S-GTP-γ-S were purchased from NEN Life Science Products (Boston, MA). Antibodies for Go and Gz proteins were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-Gi1/2 serum, AS7, was purchased from NEN Life Science Products. Anti-Gi3 serum was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY).35S-UTP and RNA labeling kits were purchased from Amersham (Arlington Heights, IL).32P-γ-ATP was purchased from ICN Biochemicals (Costa Mesa, CA)

Autoradiographic studies

Preparation of brain sections

Male and female mice with intact (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and homozygous knock-out (−/−) 5-HTT genes were decapitated. The whole brains were removed and frozen immediately in dry, ice-cooled isopentyl alcohol for 10 sec. Then the brains were placed on dry ice for 10 min until they were frozen completely. Brains were stored at −80° C until they were studied.

The mouse brain was cut into 15-μm-thick coronal sections in a cryostat. The sections were thaw-mounted onto chromalum/gelatin-coated glass slides and stored at −80°C for studies within 1 month. Each slide contained brain sections from three mice (one genotype each) so that we could limit variation between slides. Five levels of sections were collected: frontal cortex (bregma 2.46–2.8 mm), striatum (bregma 0.98–0.50 mm), medial hypothalamus (bregma 0.7 to −1.06 mm), caudal hypothalamus (bregma −1.34 to −1.94 mm), and midbrain (bregma −4.36 to −4.84 mm) according to a mouse brain atlas (Franklin and Paxinos, 1997). Adjacent sections were used in125I-MPPI binding, in situhybridization, and 35S-GTP-γ-S binding studies.

Autoradiography of 125I-MPPI binding

125I-MPPI binding sites in the brain sections were determined by autoradiographic assay as described (Kung et al., 1995) with slight modification. Briefly, the slides were thawed and dried in a desiccator at room temperature before assay. The brain sections were preincubated for 30 min at room temperature in assay buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 2 mm MgCl2). Then the slides were incubated with 125I-MPPI (0.14 nm in assay buffer) for 2 hr at room temperature. Nonspecific binding was defined in the presence of 10−5m 5-HT. Then the slides were washed twice with assay buffer at 4°C for 15 min and rinsed with cold ddH2O. After being air blow-dried, the slides were exposed to3H-Hyperfilm (Amersham) for 1 or 3 d. The 125I-MPPI binding sites in the hippocampus and dorsal raphe were measured by using films that were exposed for 1 d. The remainders of the brain regions were analyzed by using films exposed for 3 d. A set of125I microscales (Amersham) was exposed with the slides to calibrate the optic density into fmol/mg of tissue equivalent.

In situ hybridization for 5-HT1A mRNA

Preparation of riboprobes. A DNA fragment encoding the third intracellular loop of mouse 5-HT1Areceptor (695–1110 bp) was inserted into PCRscript vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). After linearizing the plasmid with SacI orKpnI for sense and antisense, respectively, we performed anin vitro transcription with an RNA labeling kit (Amersham) and 35S-UTP (1000 Ci/mmol, 20 mCi/ml; Amersham). The template DNA was removed by incubating the RNase-free DNase (10 U) at 37°C for 30 min. After the reaction was stopped by adding 25 μl of STE (TE contains 150 mm NaCl, pH 8.0), the 35S-labeled riboprobes were purified by a ProbQuant G-50 micro column (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ). Then the collected riboprobe (∼50 μl) was precipitated by ethanol (0.1 vol of 5 m ammonium acetate and 3 vol of 100% ethanol) and resuspended in 50 μl of DEPC-treated H2O after the pellets were washed with 75% ethanol. Another riboprobe encoding the 3′ noncoding region of 5-HT1A mRNA (1481–1860 bp) was prepared to evaluate the selectivity of the probes.

Hybridization. Brain slides were thawed and dried as described above. Then the brain sections were fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. After being washed twice with PBS, the sections were treated with 0.25% acetic anhydride in 1 mtriethanolamine for 10 min and dehydrated. After the sections were air-dried, 150 μl of hybridization solution (20 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 50% formamide, 0.3 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1× Denhardt's solution, 10% dextran sulfate, 150 mm DTT, 0.2% SDS, 50 μg/ml salmon sperm, 0.25 mg/ml tRNA, and 20,000–40,000 cpm/μl 35S-labeled probe) was added on each slide, and the sections were covered with a coverslip. The slides were incubated at 54°C overnight in humidified chambers (a plastic box with two layers of filter paper wetted by 50% formamide in 2× SSC).

Then the slides were washed four times with 4× SSC for 5 min at room temperature, followed by incubation of the slides with 40 μg/ml of RNase A solution (0.01 m Tris, pH 8.0, 0.5 mNaCl, and 1 mm EDTA) at 37°C for 30 min. After being washed with 1, 0.5, and 0.1× SSC at room temperature for 5 min with shaking, the slides were incubated four times in 0.1× SSC containing 2 mm DTT at 65°C for 15 min (DTT was added immediately before incubation). Then the slides were incubated in 0.1× SSC and 2 mm DTT at room temperature for 1 min, followed by dehydration with 50, 70, 90, and 95% ethanol containing 300 mm NH4Ac. After being rinsed with 100% ethanol, the slides were air-dried and exposed, along with a14C-microscale (Amersham), to3H-Hyper film for 7–14 d.

Autoradiography of 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated35S-GTP-γ-S binding

8-OH-DPAT-stimulated 35S-GTP-γ-S binding was performed as previously described (Sim et al., 1997; Waeber and Moskowitz, 1997) with slight modification. Briefly, the brain slides were thawed and dried in a desiccator for 1–2 hr (no more than 2 hr) at room temperature. After preincubation in the assay buffer [containing (in mm) 50 Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 3 MgCl2, 0.2 EGTA, 100 NaCl, and 0.2 DTT] for 15 min at room temperature, the slides were incubated in 2 mmGDP (in assay buffer) for 15 min at room temperature. Then the slides were incubated with 50 pm35S-GTP-γ-S (in assay buffer containing 2 mm GDP) in the absence or presence of 10−5m (+)8-OH-DPAT for 60 min at 30°C, defined as basal or stimulated 35S-GTP-γ-S binding, respectively. Nonspecific binding was defined in the presence of 10−5m GTP-γ-S. The slides were washed twice in 50 mm Tris buffer, pH 7.4, for 3 min at 4°C. After being rinsed with cold ddH2O, the slides were air-dried and exposed to 3H-Hyperfilm film for 3–7 d. A14C microscale set was exposed along with the slides to calibrate the density into fmol/mg of tissue equivalent.

Data analysis

Brain images were captured and analyzed with the National Institutes of Health Image program. The gray scale density readings were calibrated to fmol/mg of tissue equivalent by using the microscales (125I microscale for125I-MPPI binding and14C microscale for in situhybridization and 35S-GTP-γ-S binding). Brain regions were identified according to a mouse atlas (Franklin and Paxinos, 1997). The adjacent brain sections were used for all three autoradiographic studies. The data for a brain region of each mouse represent the mean of four adjacent brain sections.

Specific 125I-MPPI binding in each brain region was determined by subtracting the nonspecific binding sites from the total binding sites in each region. 5-HT1AmRNA levels in in situ hybridization were determined by subtracting the hybridization of sense probe from that of antisense probe. No difference was observed in the distribution and levels of 5-HT1A mRNA when in situ hybridization that used the probes encoding the third intracellular loop was compared with that using the probes encoding the 3′ noncodon region (data not shown).

8-OH-DPAT-stimulated 35S-GTP-γ-S binding sites were determined by subtracting the basal35S-GTP-γ-S binding (in the absence of 8-OH-DPAT) from the stimulated35S-GTP-γ-S binding (in the presence of 8-OH-DPAT). Because a decrease either in the density of 5-HT1A receptors or in the G-protein coupling of 5-HT1A receptors would reduce the 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated 35S-GTP-γ-S binding sites, the ratio of 125I-MPPI binding sites and 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated35S-GTP-γ-S binding sites was used to express the G-protein coupling of 5-HT1Areceptors.

Competitive RT-PCR for 5-HT1A receptors

Tissue preparation and total RNA isolation. Female 5-HTT +/+, +/−, and −/− mice (n = 8) were decapitated, and the whole brain was removed from each. The hypothalamus, hippocampus, and dorsal raphe regions were dissected. The tissues were placed immediately in 1 ml of TriReagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 4°C and homogenized with a Tissue Tearer homogenizer at high speed for 10 sec in ice. The homogenates were stored at −80°C until RNA isolation. Total RNA was isolated according to the protocol of TriReagent and dissolved in 100 μl of DEPC-treated H2O. The concentration of the RNA solution was determined by absorbance at 260 nm. After treatment with DNase (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), the RNA solutions then were diluted to 10 ng/μl for dorsal raphe and 20 ng/μl for hypothalamus and hippocampus before use. The mRNA concentrations of the samples were evaluated by RT-PCR of two housekeeping genes, cyclophilin and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPHAD). These genes were not significantly different among the three genotypes of 5-HTT mutant mice (data not shown).

Preparation of 5-HT1A standard. A plasmid containing a DNA fragment encoding the third intracellular loop of 5-HT1A receptor was digested byPflMI. The resulting cohesive ends were excised by the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase. After religation the plasmid was transfected into DH 10B Escherichia coli cells. A colony with site mutation (four base pairs shorter than the original plasmid) was selected and stored at −80°C.

To prepare 5-HT1A standard RNA, we linearized the plasmid with SacI and transcripted it with T7 RNA polymerase. After treatment with DNase the RNA was purified by phenol/chloroform extraction, followed by ethanol precipitation. The pellet was dissolved in DEPC-treated H2O. RNA concentrations were determined by absorbance at 260 nm. A series of the 5-HT1A standard solutions was prepared by sequential dilutions of the 5-HT1A standard RNA stock solution.

Competitive RT-PCR. The competitive RT-PCR was modified from the method described by Chun et al. (1996). First-strand cDNA was synthesized with the ThermoScript RT-PCR system (Life Technologies). Briefly, 5-HT1A standard RNA (1 μl) and total RNA (1 μl) were incubated with a final concentration of 10 nm 5-HT1A primer (5′-CAGTGTCTTCACTGTCTTCCT-3′, which encoded mouse 5-HT1A antisense DNA 1110–1090 bp) at 65°C for 5 min in a total volume of 5 μl. Then the denatured RNA was incubated with 5 μl of RT transcription master solution at 65°C for 45 min. The reaction was terminated by incubation of the samples at 85°C for 5 min. Two microliters of the cDNA solution were used for subsequent PCR. The PCR was performed in 10 μl of buffer solution containing 1× PCR buffer, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm dNTP, 0.8 U platinum Taq DNA polymerase, 0.5 μm sense and antisense primers (sense, encoding 695–715 bp: TGCTCATGCGGTCCTCTAT; antisense, encoding 874–857 bp: 5′-TCTCAGCACTGCGCCTGC-3′), and the 5-HT1A cDNA. After incubation at 94°C for 5 min, 28 cycles were performed at denaturation, annealing, and extension of 94°C for 30 sec, 57°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec, respectively. The reaction was terminated by incubation at 72°C for 10 min and by the addition of 2 μl of loading dye. To visualize PCR products, we end-labeled the antisense primer (2.5 μm) by incubating it with32P-[γ]-ATP (ICN Biochemicals) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (Epicenter Technologies, Madison, WI) for 30 min at 37°C, followed by termination of the reaction at 80°C for 5 min. The PCR products (2 μl) were resolved on 8% polyacrylamide DNA sequencing gel (Sequagel-8, National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA). The gel was dried and exposed to Kodak BioMax MR film. The films were analyzed densitometrically with the National Institutes of Health Image analysis program. The gray scale density was calibrated by a Control Scale T-14 (Kodak). The ratio between the density of 5-HT1A mRNA and of 5-HT1A standard RNA was calculated. The logarithm of the ratio was plotted with the logarithm of concentration of 5-HT1A standard RNA by using linear regression. The x-axis intercept of the plot was calculated by a computer program, Prism (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA), to determine the concentration of the 5-HT1AmRNA.

Immunoblots

The levels of Gi1, Gi2, Gi3, and Go proteins in the hypothalamus, midbrain, and frontal cortex were measured by using immunoblots as described in our previous paper with minor modification (Li et al., 1996). Briefly, the solubilized proteins (10–35 μg of protein) that were extracted from the membranes of the hypothalami, hippocampus, midbrains, and frontal cortices (Sternweis and Robinshaw, 1984; Okuhara et al., 1996) were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis [containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 12% acrylamide/bisacrylamide (30:0.2), 4m urea, and 375 mm Tris, pH 8.4 (Mullaney and Miligan, 1990)]. Then the proteins were transferred electrophoretically to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were incubated overnight with polyclonal antisera for Gz (anti-Gz, 1:2500), Gi1/2 (AS/7, 1:2500 dilution), Gi3(anti-Giα3, 1:2000 dilution), or Go (anti-Go, 1:500 dilution), followed by a secondary antibody for 1 hr (1:25,000 goat anti-rabbit IgG-alkaline phosphatase). After several washes the membranes were placed on a flat surface and incubated with a chemiluminescence substrate solution, CDP-Star subtract (Tropix, Bedford, MA), by pipetting a thin layer of the solution onto the membranes (∼3 ml/100 cm2)for 5 min. The membranes were wrapped with Saran wrap and then exposed to Kodak x-ray film for 5–30 sec. Films were analyzed densitometrically by the National Institutes of Health Image analysis program as detailed in our previous paper (Li et al., 1996).

Hypothermic response to a 5-HT1A agonist, 8-OH-DPAT in female 5-HTT mutant mice

5-HTT +/+, +/−, and −/− mice were injected with 8-OH-DPAT (0.1 mg/kg, s.c.). Body temperatures of the mice were measured every 10 min, from 20 min before to 60 min after the 8-OH-DPAT injections. The means of the temperatures from 20 and 10 min before 8-OH-DPAT injections were used for the zero time point temperature measures. The body temperatures of the mice were measured by a digital thermometer with a temperature probe (Physitemp BAT-12, Physitemp Instruments, Clifton, NJ) inserted 2–2.5 cm into the rectum, with the mice slightly restrained by the tail. The temperatures were measured in a room with an ambient temperature at 25°C.

Statistics

The data are presented as group means and the SEM of five to eight mice. The data were analyzed by one-way or two-way ANOVA, followed by Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc tests when ANOVA showed a significant difference. Statistics were performed with a computer program (SuperANOVA, Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA).

RESULTS

Autoradiography of 125I-MPPI binding: The density of 5-HT1A receptors in 5-HTT mutant mice

125I-MPPI binding sites were reduced significantly in the dorsal raphe of 5-HTT −/− mice (Fig. 1; Table 1). The reduction in the 5-HT1A receptors was ∼50% in the female and ∼30% in the male mice (Table 1). Although 5-HT1A receptors in the medial raphe were decreased significantly in the female 5-HTT mutant mice, a significant reduction was not observed in the male mice (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Autoradiography of 125I-MPPI binding in 5-HTT mutant mice. Left, Wild-type 5-HTT mice (5-HTT +/+). Middle, Heterozygous 5-HTT knock-out mice (5-HTT +/−). Right, Homozygous 5-HTT knock-out mice (5-HTT −/−). The brain sections from top to bottom are striatum (bregma 0.98–0.50 mm), medium hypothalamus (bregma 0.7 to −1.06 mm), caudal hypothalamus (bregma −1.34 to −1.94 mm), and midbrain (bregma −4.36 to −4.84 mm). ACo, Anterior cortical amygdaloid nucleus; AH, anterior hypothalamic nucleus;BLA, basolateral amygdaloid nucleus, anterior;BMA, basomedial amygdaloid, anterior;CA1–CA3, CA1–CA3 field of hippocampus;CeC, central amygdaloid nucleus, capsular division;CeMAD, central amygdaloid nucleus, medial anterodorsal;CeMAV, central amygdaloid nucleus, medial anteroventral;DEn, dorsal endopiriform nucleus; DG, dentate gyrus of hippocampus; DMN, dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus; DRN, dorsal raphe nucleus;La, lateral amygdaloid nucleus; Ld, lambdoid septal zone; LH, lateral hypothalamic nucleus;LSI, lateral septal nucleus, intermediate;MeA, medial amygdaloid nucleus, anterodorsal;MRN, medial raphe nucleus; MS, medial septal nucleus; PVN, paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus; VMN, ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus.

Table 1.

Autoradiography of 125I-MPPI binding in 5-HTT mutant mice

| Density of125I-MPPI-labeled 5-HT1A receptors (fmol/mg tissue equivalent) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |||||

| 5-HTT +/+ | 5-HTT +/− | 5-HTT −/− | 5-HTT +/+ | 5-HTT +/− | 5-HTT −/− | |

| Frontal cortex | ||||||

| M2 I–IV | 43 ± 3 | 45 ± 3 | 39 ± 3 | 40 ± 4 | 45 ± 2 | 39 ± 2 |

| M2 V | 92 ± 6 | 100 ± 4 | 74 ± 10 | 101 ± 7 | 110 ± 3 | 105 ± 5 |

| M2 VI | 88 ± 6 | 94 ± 4 | 78 ± 14 | 89 ± 6 | 102 ± 4 | 100 ± 2 |

| LO I–IV | 66 ± 7 | 58 ± 5 | 67 ± 14 | 91 ± 11 | 93 ± 6 | 110 ± 7 |

| LO V | 142 ± 11 | 140 ± 6 | 128 ± 21 | 163 ± 11 | 159 ± 7 | 187 ± 4* |

| Septum | ||||||

| LSI | 110 ± 6 | 108 ± 6 | 77 ± 6* | 123 ± 13 | 126 ± 5 | 130 ± 16 |

| Ld | 230 ± 16 | 229 ± 13 | 165 ± 8* | 256 ± 16 | 260 ± 15 | 238 ± 19 |

| MS | 230 ± 19 | 241 ± 12 | 196 ± 24 | 278 ± 23 | 282 ± 25 | 302 ± 20 |

| Hypothalamus | ||||||

| PVN | 28 ± 3 | 29 ± 2 | 20 ± 1* | 40 ± 4 | 41 ± 4 | 38 ± 3 |

| AHN | 64 ± 2 | 70 ± 3 | 51 ± 2* | 73 ± 6 | 76 ± 5 | 65 ± 9 |

| LHN | 29 ± 2 | 32 ± 1 | 22 ± 3* | 31 ± 2 | 30 ± 2 | 26 ± 3 |

| VMN | 42 ± 3 | 39 ± 2 | 23 ± 5* | 69 ± 6 | 65 ± 3 | 60 ± 4 |

| DM | 45 ± 2 | 41 ± 1 | 27 ± 3* | 81 ± 4 | 75 ± 3 | 69 ± 6 |

| Amygdala | ||||||

| La | 29 ± 2 | 32 ± 3 | 24 ± 2 | 32 ± 2 | 30 ± 3 | 32 ± 2 |

| BLa | 30 ± 2 | 27 ± 2 | 23 ± 3 | 27 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 | 26 ± 2 |

| CeC | 41 ± 2 | 37 ± 2 | 28 ± 4* | 39 ± 2 | 41 ± 2 | 42 ± 5 |

| CeMAD | 130 ± 13 | 131 ± 10 | 98 ± 9 | 153 ± 21 | 144 ± 7 | 117 ± 3 |

| CeMAV | 90 ± 5 | 80 ± 5 | 58 ± 6* | 109 ± 14 | 105 ± 2 | 89 ± 7 |

| BMA | 150 ± 4 | 118 ± 11* | 89 ± 8* | 136 ± 14 | 141 ± 15 | 119 ± 14 |

| MeAD | 79 ± 3 | 79 ± 5 | 54 ± 2* | 87 ± 3 | 94 ± 5 | 73 ± 6 |

| Aco | 134 ± 5 | 128 ± 10 | 92 ± 2* | 136 ± 10 | 156 ± 16 | 120 ± 11 |

| Dorsal endopiriform | ||||||

| (DEn) | 327 ± 14 | 330 ± 19 | 261 ± 22* | 316 ± 18 | 317 ± 13 | 320 ± 16 |

| Hippocampus | ||||||

| CA1 | 300 ± 16 | 291 ± 21 | 322 ± 40 | 376 ± 21 | 362 ± 12 | 367 ± 19 |

| CA2 | 34 ± 2 | 30 ± 2 | 32 ± 3 | 81 ± 4 | 71 ± 4 | 70 ± 4 |

| CA3 | 41 ± 4 | 35 ± 2 | 43 ± 6 | 99 ± 6 | 83 ± 5 | 82 ± 4 |

| DG | 66 ± 15 | 46 ± 5 | 67 ± 19 | 170 ± 20 | 126 ± 10 | 107 ± 20 |

| Midbrain | ||||||

| DR | 677 ± 78 | 484 ± 63 | 257 ± 11* | 664 ± 57 | 573 ± 42 | 387 ± 43* |

| MR | 352 ± 30 | 353 ± 19 | 241 ± 26* | 374 ± 12 | 511 ± 34* | 315 ± 34 |

The data are represented as mean ± SEM of five to seven mice.

Significant difference from 5-HTT +/+ mice;p < 0.05.

The abbreviations are the same as listed in Figure 1. In addition,LO I–V, lateral orbital cortex layers I–V; M2 I–VI, secondary motor cortex layers I–VI.

In the female 5-HTT knock-out mice the125I-MPPI binding sites were reduced significantly in all of the nuclei of the hypothalamus and several nuclei in the amygdala and septum (Table 1). However, a similar significant reduction was not observed in the male mice, although there was a tendency toward reduction of the125I-MPPI binding sites in these brain regions, e.g., hypothalamus and amygdala (Table 1). In contrast, no significant reduction in 125I-MPPI binding sites was observed in the hippocampus and frontal cortex of either female or male 5-HTT −/− mice (Table 1).

In situ hybridization to determine 5-HT1A mRNA in 5-HTT mutant mice

5-HT1A mRNA levels in the nuclei of raphe and hypothalamus of 5-HTT mutant mice were examined by in situ hybridization (Fig. 2; Table2). The distribution of 5-HT1A mRNA was consistent with both riboprobes (encoding the third intracellular loop or the 3′ noncodon region), suggesting that the riboprobe used in the assay was selective for 5-HT1A mRNA. 5-HT1A mRNA levels were reduced significantly in the dorsal raphe of 5-HTT +/− and −/− male mice and 5-HTT −/− female mice (Table 2). No significant change was observed in the other brain regions.

Fig. 2.

Autoradiography of in situhybridization for 5-HT1A receptor mRNA in 5-HTT mutant mice. The brain sections were hybridized with 32P-riboprobe encoding the third intracellular loop, as described in Materials and Methods. The brain sections were adjacent to the medial hypothalamus and midbrain sections in the 125I-MPPI binding.

Table 2.

In situ hybridization of 5-HT1Areceptor mRNA in 5-HTT mutant mice

| 5-HT1A receptor mRNA (fmol/mg tissue) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |||||

| 5-HTT +/+ | 5-HTT +/− | 5-HTT −/− | 5-HTT +/+ | 5-HTT +/− | 5-HTT −/− | |

| Hypothalamus | ||||||

| AHN | 48 ± 4 | 39 ± 2 | 42 ± 4 | 36 ± 3 | 44 ± 7 | 44 ± 3 |

| LHN | 13 ± 2 | 10 ± 1 | 9 ± 1 | 6 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 | 5 ± 2 |

| VMN | 48 ± 6 | 54 ± 8 | 41 ± 9 | 23 ± 4 | 28 ± 3 | 34 ± 4 |

| DM | 31 ± 4 | 33 ± 2 | 29 ± 3 | 12 ± 2 | 16 ± 3 | 16 ± 3 |

| Midbrain | ||||||

| DR | 270 ± 25 | 231 ± 19 | 177 ± 9* | 371 ± 52 | 243 ± 26* | 221 ± 22* |

| MR | 252 ± 16 | 254 ± 15 | 257 ± 34 | 261 ± 32 | 278 ± 21 | 268 ± 31 |

The data are represented as mean ± SEM of five to seven mice.

Significant difference from 5-HTT +/+ mice;p < 0.05.

The abbreviations are as same as listed in Figure 1.

Competitive RT-PCR for examination of 5-HT1A mRNA in 5-HTT mutant mice

To confirm the results observed by in situhybridization, we conducted competitive RT-PCR to examine 5-HT1A mRNA in the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and dorsal raphe regions. The plots of the competitive RT-PCR showed a high linearity (Fig. 3). The mean of regression coefficient (r2) was 0.96. The internal variation was 12.4%.

Fig. 3.

An example of competitive RT-PCR for 5-HT1A receptor mRNA in the dorsal raphe of 5-HTT mutant mice. A, Autoradiography of DNA sequence gel that resolves RT-PCR products from 5-HT1A mRNA (5-HT1A) and 5-HT1A RNA standard (5-HT1A st). Four concentrations of 5-HT1A RNA standard were used to compete 5-HT1A mRNA (10 ng of total RNA). B, Linear regression curve for calculation of concentration of 5-HT1AmRNA. The intercept of the x-axis represents the concentration of 5-HT1A mRNA.

In competitive RT-PCR a significant reduction of 5-HT1A mRNA was observed in the dorsal raphe region of female 5-HTT +/− and −/− mice (one-way ANOVA,F(2, 18) = 5.1, p < 0.05; Table 3). This reduction was not found in the hypothalamus or hippocampus (Table 3).

Table 3.

Competitive RT-PCR for 5-HT1A mRNA levels in female 5-HTT mutant mice

| 5-HT1A mRNA (104molecules/ng total RNA) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HTT +/+ | 5-HTT +/− | 5-HTT −/− | |

| Dorsal raphe | 0.64 ± 0.1 | 0.28 ± 0.023-150 | 0.35 ± 0.13-150 |

| Hypothalamus | 12.3 ± 1.6 | 11.3 ± 1.6 | 12.6 ± 2.4 |

| Hippocampus | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 5.4 ± 0.7 |

Data are represented as mean ± SEM of seven to eight mice.

F3-150: Significant difference from 5-HTT +/+ mice;p < 0.05.

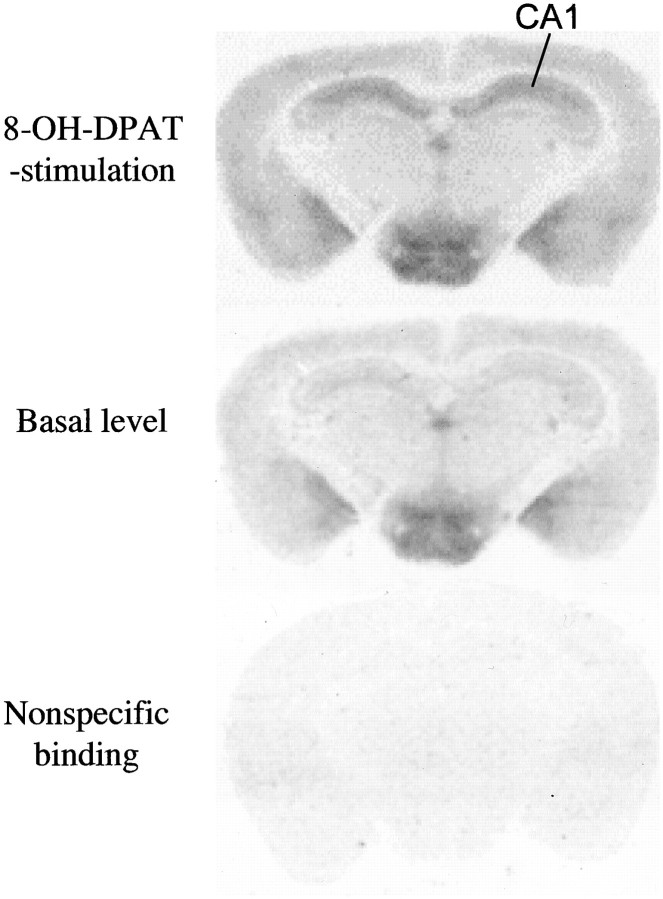

Autoradiography of 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated 35S-GTP-γ-S binding in 5-HTT mutant mice

8-OH-DPAT increased 35S-GTP-γ-S binding ∼100% in the CA1 region of hippocampus and 50% in the dorsal raphe (Figs. 4, 5). However, a high basal level of 35S-GTP-γ-S binding was observed in the hypothalamus and amygdala (Fig. 4), which caused a limited increase of 35S-GTP-γ-S binding in the presence of 8-OH-DPAT. Therefore, 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated35S-GTP-γ-S binding sites were examined only in the dorsal raphe and CA1 region of hippocampus.

Fig. 4.

8-OH-DPAT-stimulated 35S-GTP-γ-S binding in the hippocampus of normal mice. Top,35S-GTP-γ-S binding in the presence of 8-OH-DPAT.Middle, 35S-GTP-γ-S binding in the absence of 8-OH-DPAT. Bottom, Nonspecific binding defined by the presence of 10−5mGTP-γ-S.

Fig. 5.

Autoradiography of 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated35S-GTP-γ-S binding in the midbrain sections of 5-HTT mutant mice. Left, 35S-GTP-γ-S binding in the presence of 8-OH-DPAT. Right,35S-GTP-γ-S binding in the absence of 8-OH-DPAT.

8-OH-DPAT-stimulated 35S-GTP-γ-S binding was reduced significantly in the dorsal raphe of 5-HTT −/− mice (Table 4; Fig.5). However, the ratio of125I-MPPI binding sites and 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated 35S-GTP-γ-S binding sites was not altered significantly in 5-HTT mutant mice (Table 4). This suggested that the reduction of 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated35S-GTP-γ-S binding in the dorsal raphe is primarily attributable to the observed decreased density of 5-HT1A receptors and not to a reduction in the G-protein coupling of 5-HT1A receptors. On the other hand, 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated35S-GTP-γ-S binding was not changed in the CA1 region of hippocampus of 5-HTT mutant mice (Table 4). No difference in the basal level of35S-GTP-γ-S was observed among three genotypes of 5-HTT mutant mice.

Table 4.

8-OH-DPAT-stimulated 35S-GTP-γ-S binding in 5-HTT knock-out mice

| 35S-GTP-γ-S binding (fmol/mg tissue) | Ratio of125I-MPPI/35S-GTP-γ-S binding | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HTT +/+ | 5-HTT +/− | 5-HTT −/− | 5-HTT +/+ | 5-HTT +/− | 5-HTT −/− | |

| Female | ||||||

| DRN | 128 ± 15 | 104 ± 14 | 78 ± 144-150 | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 3.6 ± 0.5 |

| CA1 | 198 ± 15 | 180 ± 5 | 174 ± 11 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.3 |

| Male | ||||||

| DRN | 89 ± 16 | 124 ± 13 | 81 ± 22 | 8.3 ± 1 | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 6.9 ± 2.4 |

| CA1 | 228 ± 14 | 227 ± 11 | 214 ± 17 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 |

Data are represented as mean ± SEM of five to seven mice.

F4-150: Significant difference from 5-HTT +/+ mice;p < 0.05.

The abbreviations are as same as listed in Figure 1.

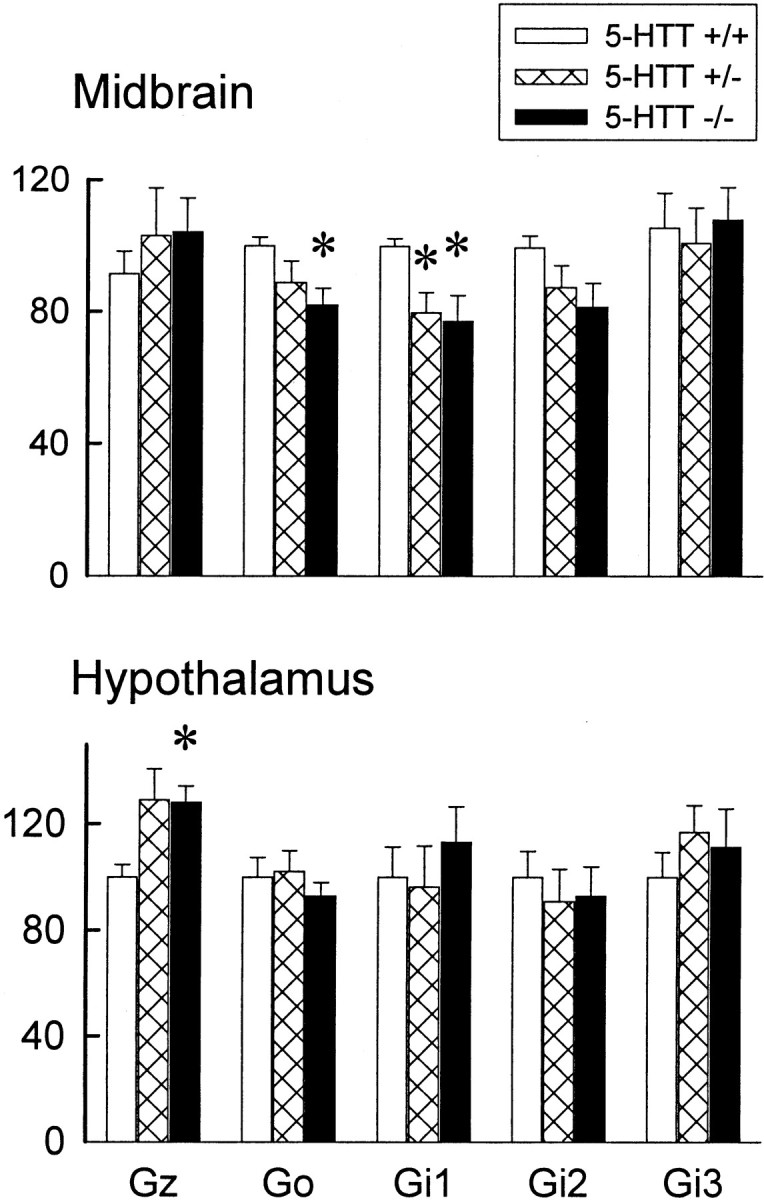

G-protein levels in brain of 5-HTT mutant mice

Several G-proteins that are coupled to 5-HT1A receptors were examined in the frontal cortex, hypothalamus, hippocampus, and midbrain of female mice with 5-HTT mutations by using immunoblots (Fig.6). Gi1 and Go proteins in the midbrain of 5-HTT mice were reduced significantly as compared with their normal littermates. On the other hand, Gz proteins in the hypothalamus were increased significantly in 5-HTT −/− mice. No significant changes of Gi2 and Gi3 proteins were observed in any of the brain regions that were examined. None of the G-proteins was altered in the hippocampus and frontal cortex (not shown by data).

Fig. 6.

G-protein concentrations in the midbrain (top) and hypothalamus (bottom) of female 5-HTT mutant mice. The data represent the mean ± SEM of eight mice per group. *Significant difference from 5-HTT +/+ mice;p < 0.05.

Hypothermic response to 8-OH-DPAT in female 5-HTT mutant mice

The body temperature of 5-HTT +/+ mice was attenuated significantly 10 min after injection with 8-OH-DPAT (Fig.7). The peak time of the hypothermia that was induced by 8-OH-DPAT was 20 min. The hypothermic response to 8-OH-DPAT was absent in 5-HTT −/− mice. Although there was a slight attenuation of the body temperature after the injection with 8-OH-DPAT in 5-HTT +/− mice, the difference did not reach statistical significance when compared with 5-HT +/+ mice (Fig. 7). Furthermore, there was no significant difference between the hypothermic response to 8-OH-DPAT in 5-HTT +/− and that in 5-HTT −/− mice.

Fig. 7.

Hypothermic response to 8-OH-DPAT in female 5-HTT knock-out mice. The data represent the mean ± SEM of 10 mice per group. Two-way ANOVA: main effect of genotype,F(2,147) = 31.07, p< 0.0001; main effect of time,F(6,147) = 8.77, p< 0.0001; interaction between genotype and time,F(12,147) = 1.49, p= 0.132. *Significant difference from those in the 0 time points of the same genotype of 5-HTT, p < 0.05 (Student–Newman–Keuls' multiple range test). #, Significant difference from the 5-HTT +/+ mice (at same time point),p < 0.05 (Student–Newman–Keuls' multiple range test).

DISCUSSION

The present studies demonstrated that the density of 5-HT1A receptors in 5-HTT −/− mice is reduced in a brain region-specific manner. These results confirm our previous observations that the desensitization of 5-HT1Areceptors in the hypothalamus and in the dorsal raphe nucleus of 5-HTT mutant mice is mediated by a reduction of the density of 5-HT1A receptors (Li et al., 1999). Furthermore, we have now shown that the reduction of 5-HT1Areceptors is more extensive in female than in male 5-HTT mutant mice. This is consistent with the functional examination that the hypothermic response to 8-OH-DPAT is attenuated much more extensively in female than in male 5-HTT +/− mice. In our previous report male 5-HTT +/− mice demonstrated essentially no change in the hypothermic response to 8-OH-DPAT as compared with 5-HTT +/+ littermates (Li et al., 1999). However, our present data indicated that this hypothermic response in female 5-HTT +/− mice is virtually identical to 5-HTT −/− mice. The reduction in the density of 5-HT1A receptors in the dorsal raphe of 5-HTT +/− and −/− mice may be, at least partly, attributable to a decrease in 5-HT1A gene expression. On the other hand, no decrease in 5-HT1A receptor mRNA was observed in the hypothalamus of 5-HTT −/− mice. These results suggest that more than one mechanism is involved in the regulation of the density of 5-HT1A receptors in different brain regions. In addition, our studies of G-protein coupling to 5-HT1A receptors and G-protein levels indicated that these elements in the 5-HT1A signal transduction pathway do not play a major role in the desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors in the 5-HTT mutant mice.

Among different brain regions the most marked reduction of 5-HT1A receptors was observed in the dorsal raphe nucleus of both male and female 5-HTT −/− mice. These data could account for eliminated electrophysiological and hypothermic responses to 8-OH-DPAT in 5-HTT −/− mice (Gobbi et al., 1999; Li et al., 1999), functional tests for 5-HT1A receptors in the dorsal raphe of mice (Bill et al., 1991). Also, these data are consistent with the observations from other investigators who also reported a reduction of 3H-WAY-100635 (a 5-HT1A antagonist) binding sites in the dorsal raphe nucleus, but not the CA1 region of hippocampus, in 5-HTT mutant mice (Fabre et al., 1998). Besides the dorsal raphe, a reduction in the density of 5-HT1A receptors also was demonstrated in the median raphe, most nuclei of hypothalamus, as well as some nuclei of the amygdala and septum of female 5-HTT −/− mice. Although the density of 5-HT1A receptors in the nuclei of hypothalamus of male 5-HTT −/− mice was not statistically different, a tendency toward a reduction was observed in all of the hypothalamic nuclei. In fact, a homogenate ligand-binding assay showed that the density of 5-HT1A receptors was reduced significantly in the hypothalamus of male 5-HTT knock-out mice (Li et al., 1999). It has been known that the hypothalamus and amygdala are related to the regulation of emotion. It is possible that the reduction in the 5-HT1A receptors in these regions contributes to the increase of anxiety and decrease in depression-like behaviors that recently were observed in the 5-HTT −/− mice (C. Wichems, unpublished data). On the other hand, no significant changes of 5-HT1A receptors have been found in the hippocampus and frontal cortex.

All together, these results suggest that 5-HT1Areceptors in 5-HTT mutant mice are regulated differently in the different brain regions. In the dorsal raphe of 5-HTT mutant mice the 5-HT1A receptors are reduced extensively, which might be attributable to a decrease in gene expression, i.e., regulation of gene transcription. On the other hand, the density, but not mRNA, of 5-HT1A receptors is reduced in the hypothalamus, amygdala, septum, and median raphe of 5-HTT mutant mice, suggesting that translational regulation and/or post-translational modifications may be involved. The mechanism underlying the regulation of 5-HT1A receptors in the different brain regions of 5-HTT mutant mice is still unknown. 5-HT1A receptors in the dorsal and median raphe nuclei are autoreceptors. The reduction in the density of 5-HT1A receptors could result from a feedback regulation induced by sustained high extracellular concentrations of 5-HT because of the lack of the 5-HTT (Mathews et al., 2000). The fact that the reduction of the 5-HT1A receptors in the dorsal raphe is more extensive than in other brain regions supports the hypothesis that the 5-HT1A autoreceptors are more sensitive to an increase of 5-HT than postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors (Artigas et al., 1996; Blier et al., 1998).

An important finding in the present studies is that the reduction of 5-HT1A receptors is substantially greater in the female than in the male 5-HTT mutant mice. Furthermore, in comparison to our previous results in male mice (Li et al., 1999), the hypothermic response to 8-OH-DPAT in female 5-HTT +/− mice is more marked than that in male 5-HTT mutant mice. This result is important because it may provide an insight into why women more frequently develop affective and some anxiety disorders. It has been known that female gonadal hormones, especially estrogen, can regulate 5-HT1Areceptors (Lakoski, 1989; Maswood et al., 1995; Trevino et al., 1999;Osterlund et al., 2000). For example, estrogen treatment attenuated 5-HT1A receptor functions (Lakoski, 1989; Maswood et al., 1995) and decreased 5-HT1A receptor mRNA levels in ovariectomized monkey and rats (Pecins-Thompson and Bethea, 1999; Osterlund et al., 2000). On the other hand, estrogen also reduces 5-HTT mRNA concentrations (Pecins-Thompson et al., 1998). Therefore, the remarkable decrease of the 5-HT1A receptors in female 5-HTT mutant mice could result from synergistic effects of estrogen and the 5-HTT mutation on 5-HT1Areceptors and/or interaction between estrogen and 5-HTT.

Another possible cause for the desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors is alteration of their G-protein coupling. Although 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated GTP-γ-S binding in the dorsal raphe was reduced significantly in the 5-HTT −/− mice, the ratio of125I MPPI and 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated GTP-γ-S binding was not altered significantly. This suggests that the reduction in the 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated GTP-γ-S binding is attributable to a decrease of the number of 5-HT1A receptors, but not any attenuation of G-protein coupling to 5-HT1A receptors. Furthermore, although Go and Gi1 proteins in the midbrain are reduced significantly, but modestly, in the female 5-HTT −/− mice, these and other G-proteins in the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and frontal cortex were not reduced significantly. It is interesting that Gz proteins in the hypothalamus are increased even modestly in the 5-HTT mutant mice. Gz proteins are coupled to 5-HT1A receptors in the hypothalamus that regulate oxytocin release (Serres et al., 2000). The elevation of the Gz proteins in the 5-HTT mutant mice could be a compensatory effect for reduction in the 5-HT1Areceptors in the hypothalamus. All together, these data suggest that alteration in the G-protein coupling to the 5-HT1A receptors is not a major mechanism for the desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors in 5-HTT mutant mice.

Similar to these findings in 5-HTT mutant mice, the desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors also has been observed after chronic administration of SSRIs in human and rodents (Li et al., 1997a;Lerer et al., 1999; Raap et al., 1999). In both situations the desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors occurs in the hypothalamus and dorsal raphe, but not in the hippocampus and cortex (Le Poul et al., 1995, 2000; Li et al., 1997a). However, the mechanisms underlying the desensitization may be different between 5-HTT mutant mice and that found after chronic treatment with SSRIs. In 5-HTT mutant mice the density of 5-HT1A receptors, but not their signal transduction, is reduced. On the other hand, chronic treatment with SSRIs does not reduce the density of 5-HT1A receptors in any brain regions (Li et al., 1997b; Le Poul et al., 2000). Instead, some decreases in several G-protein concentrations have been observed (Li et al., 1996, 1997a). These differences may be attributable to the much longer and more marked lack or reduction of 5-HTT function in the 5-HTT mutant mice than that in the SSRI-treated animals. An alternative explanation could be that the reduction of 5-HT1A receptors in 5-HTT mutant mice results from more complex changes during neuron development.

In conclusion, the present studies demonstrate that 5-HT1A receptors in the 5-HTT mutant mice are brain region-specifically reduced. This result could account for our previous results indicating that 5-HT1Areceptor-mediated temperature and neuroendocrine responses are desensitized in 5-HTT mutant mice ((Li et al., 1999). The reduction in the density of 5-HT1A receptors in the dorsal raphe, but not in hypothalamus, may be attributable to an attenuation of 5-HT1A gene expression. More interestingly, the reduction of 5-HT1A receptors is more extensive in the female than in the male 5-HTT mutant mice. This is consistent with our finding that female 5-HTT mutant mice have a more prominent and consistent increase in anxiety than males when compared with their normal littermates. The significance of these observations is that it may provide a greater insight for the frequently reported higher incidence of affective and some anxiety disorders in women and also the premenstrual syndrome symptomatology.

Footnotes

We thank Dr. Barry B. Kaplan and Dr. Jayaprakash D. Karkera for their excellent advice and Teresa Tolliver and Su-Jan Huang for their important technical assistance with these experiments.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Qian Li, Laboratory of Clinical Science, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, Room 3D41, 10 Center Drive, MSC 1264, Bethesda, MD 20892-1264. E-mail: qianli@codon.nih.gov.

REFERENCES

- 1.Artigas F, Romero L, De Montigny C, Blier P. Acceleration of the effect of selected antidepressant drugs in major depression by 5-HT1A antagonists. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:378–383. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bengel D, Murphy DL, Andrews AM, Wichems CH, Feltner D, Heils A, Mossner R, Westphal H, Lesch KP. Altered brain serotonin homeostasis and locomotor insensitivity to 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”) in serotonin transporter-deficient mice. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:649–655. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.4.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bill DJ, Knight M, Forster EA, Fletcher A. Direct evidence for an important species-difference in the mechanism of 8-OH-DPAT-induced hypothermia. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:1857–1864. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blier P, Pineyro G, El Mansari M, Bergeron R, De Montigny C. Role of somatodendritic 5-HT autoreceptors in modulating 5-HT neurotransmission. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;861:204–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chun JT, Gioio AE, Crispino M, Giuditta A, Kaplan BB. Differential compartmentalization of mRNAs in squid giant axon. J Neurochem. 1996;67:1806–1812. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67051806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabre V, Rioux A, Lanfumey L, Lesch K-P, Hamon M. Adaptive changes in central 5-HT receptors in knock-out mice lacking the 5-HT transporter. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1998;24:1113. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic; San Diego: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gobbi G, Lesch KP, Murphy DL, Blier P. The serotonin transporter knock-out mice: new perspectives on the comprehension of serotonin system. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1999;25:714. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg BD, Li Q, Lucas FR, Hu S, Sirota LA, Benjamin J, Lesch KP, Hamer D, Murphy DL. Association between the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism and personality traits in a primarily female population sample. Am J Med Genet. 2000;96:202–216. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000403)96:2<202::aid-ajmg16>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heisler LK, Chu HM, Brennan TJ, Danao JA, Bajwa P, Parsons LH, Tecott LH. Elevated anxiety and antidepressant-like responses in serotonin 5-HT1A receptor mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15049–15054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kung M-P, Frederick D, Mu M, Zhuang Z-P, Kung HF. 4-(2′-Methoxy-phenyl)-1-[2′-(n-2"-pyridinyl)-p-iodobenzamido]-ethyl-piperazine ([125I]p-MPPI) as a new selective radioligand of serotonin-1A sites in rat brain: in vitro binding and autoradiographic studies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;272:429–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakoski JM. Cellular electrophysiological approaches to the central regulation of female reproductive aging. In: Lakoski JM, Perez-Polo JR, Rassin DK, editors. Neurology and neurobiology, Vol 50, Neural control of reproductive function. Liss; New York: 1989. pp. 209–220. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Poul E, Laaris N, Doucet E, Laporte AM, Hamon M, Lanfumey L. Early desensitization of somato-dendritic 5-HT1A autoreceptors in rats treated with fluoxetine or paroxetine. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1995;352:141–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00176767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Poul E, Boni C, Hanoun N, Laporte AM, Laaris N, Chauveau J, Hamon M, Lanfumey L. Differential adaptation of brain 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors and 5-HT transporter in rats treated chronically with fluoxetine. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:110–122. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lerer B, Gelfin Y, Gorfine M, Allolio B, Lesch KP, Newman ME. 5-HT1A receptor function in normal subjects on clinical doses of fluoxetine: blunted temperature and hormone responses to ipsapirone challenge. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:628–639. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, Benjamin J, Muller CR, Hamer DH, Murphy DL. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science. 1996;274:1527–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Q, Muma NA, Van de Kar LD. Chronic fluoxetine induces a gradual desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors: reductions in hypothalamic and midbrain Gi and Go proteins and in neuroendocrine responses to a 5-HT1A agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;279:1035–1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q, Muma NA, Battaglia G, Van de Kar LD. A desensitization of hypothalamic 5-HT1A receptors by repeated injections of paroxetine: reduction in the levels of Gi and Go proteins and neuroendocrine responses, but not in the density of 5-HT1A receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997a;282:1581–1590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Q, Battaglia G, Van de Kar LD. Autoradiographic evidence for differential G-protein coupling of 5-HT1A receptors in rat brain: lack of effect of repeated injections of fluoxetine. Brain Res. 1997b;769:141–151. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00693-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q, Wichems C, Heils A, Van de Kar LD, Lesch KP, Murphy DL. Reduction of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT1A)-mediated temperature and neuroendocrine responses and 5-HT1A binding sites in 5-HT transporter knock-out mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:999–1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacKenzie A, Quinn J. A serotonin transporter gene intron 2 polymorphic region, correlated with affective disorders, has allele-dependent differential enhancer-like properties in the mouse embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15251–15255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maswood S, Stewart G, Uphouse L. Gender and estrous cycle effects of the 5-HT1A agonist, 8-OH-DPAT, on hypothalamic serotonin. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1995;51:807–813. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathews TA, Fedele DE, Unger EL, Lesch K-P, Murphy DL, Andrews AM. Effects of serotonin transporter inactivation on extracellular 5-HT levels, in vivo microdialysis recovery, and MDMA-induced release of serotonin and dopamine in mouse striatum. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2000;26:11599. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazzanti CM, Lappalainen J, Long JC, Bengel D, Naukkarinen H, Eggert M, Virkkunen M, Linnoila M, Goldman D. Role of the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism in anxiety-related traits. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:936–940. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.10.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mullaney I, Miligan G. Identification of two distinct isoforms of the guanine nucleotide binding protein Go in neuroblastoma X glioma hybrid cells: independent regulation during cyclic AMP-induced differentiation. J Neurochem. 1990;55:1890–1898. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb05773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy DL, Wichems C, Li Q, Heils A. Molecular manipulations as tools for enhancing our understanding of 5-HT neurotransmission. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:246–252. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01325-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okuhara DY, Lee JM, Beck SG, Muma NA. Differential immunohistochemical labeling of Gs, Gi1 and 2, and Go α-subunits in rat forebrain. Synapse. 1996;23:246–257. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199608)23:4<246::AID-SYN2>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osterlund MK, Halldin C, Hurd YL. Effects of chronic 17β-estradiol treatment on the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor mRNA and binding levels in the rat brain. Synapse. 2000;35:39–44. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(200001)35:1<39::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parks CL, Robinson PS, Sibille E, Shenk T, Toth M. Increased anxiety of mice lacking the serotonin-1A receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10734–10739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pecins-Thompson M, Bethea CL. Ovarian steroid regulation of serotonin-1A autoreceptor messenger RNA expression in the dorsal raphe of rhesus macaques. Neuroscience. 1999;89:267–277. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00326-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pecins-Thompson M, Brown NA, Bethea CL. Regulation of serotonin re-uptake transporter mRNA expression by ovarian steroids in rhesus macaques. Mol Brain Res. 1998;53:120–129. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raap DK, Evans S, Garcia F, Li Q, Muma NA, Wolf WA, Battaglia G, Van de Kar LD. Daily injections of fluoxetine induce dose-dependent desensitization of hypothalamic 5-HT1A receptors: reductions in neuroendocrine responses to 8-OH-DPAT and in levels of Gz and Gi proteins. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:98–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramboz S, Oosting R, Amara DA, Kung HF, Blier P, Mendelsohn M, Mann JJ, Brunner D, Hen R. Serotonin receptor 1A knock-out: an animal model of anxiety-related disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14476–14481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serres F, Li Q, Garcia F, Raap DK, Battaglia G, Muma NA, Van de Kar LD. Evidence that Gz proteins couple to hypothalamic 5-HT1A receptors in vivo. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3095–3103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-09-03095.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sim LJ, Xiao RY, Childers SR. In vitro autoradiographic localization of 5-HT1A receptor-activated G-proteins in the rat brain. Brain Res Bull. 1997;44:39–45. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(97)00061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sternweis PC, Robinshaw JD. Isolation of two proteins with high affinity for guanine nucleotides from membranes of bovine brain. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:13806–13813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stoltenberg SF, Burmeister M. Recent progress in psychiatric genetics—some hope but no hype. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:927–935. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.6.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trevino A, Wolf A, Jackson A, Price T, Uphouse L. Reduced efficacy of 8-OH-DPAT's inhibition of lordosis behavior by prior estrogen treatment. Horm Behav. 1999;35:215–223. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1999.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waeber C, Moskowitz MA. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (1A) and 5-hydroxytryptamine (1B) receptors stimulate [35S]guanosine-5′-O-(3-thio)triphosphate binding to rodent brain sections as visualized by in vitro autoradiography. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52:623–631. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.4.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou FC, Tao-Cheng JH, Segu L, Patel T, Wang Y. Serotonin transporters are located on the axons beyond the synaptic junctions: anatomical and functional evidence. Brain Res. 1998;805:241–254. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00691-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhuang XX, Gross C, Santarelli L, Compan V, Trillat AC, Hen R. Altered emotional states in knock-out mice lacking 5-HT1A or 5-HT1B receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:S52–S60. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]