Abstract

UNC-6/netrins compose a small phylogenetically conserved family of proteins that act as axon guidance cues. With a signal sequence trap method, we isolated a cDNA encoding a novel member of the UNC-6/netrin family, which we named netrin-G1. Unlike classical netrins, netrin-G1 consists of at least six isoforms of which five were predominantly anchored to the plasma membrane via glycosyl phosphatidyl-inositol linkages. Netrin-G1 transcripts were first detected in midbrain and hindbrain regions by embryonic day 12 and reached highest levels at perinatal stages in various brain regions, including olfactory bulb mitral cells, thalamus, and deep cerebellar nuclei. Its expression was primarily restricted to the CNS. Interestingly, netrin-G1 proteins did not show appreciable affinity to any netrin receptor examined. Unlike netrin-1, a secreted form of netrin-G1 consistently failed to attract circumferentially growing axons from the cerebellar plate. Our findings suggest that netrin-G1 and its putative receptors have coevolved independently from the classical netrins. The expression pattern of netrin-G1 and its predicted neuronal membrane localization suggest it may also have novel signaling functions in nervous system development.

Keywords: netrin, GPI-linkage, glycosyl phosphatidylinositol, axon guidance, receptor, signal sequence trap, UNC-6, mouse, isoform, alternative splicing, CNS

During development of the nervous system, growing axons are appropriately guided to their correct targets to form the precise wiring of intricate circuits. The molecular mechanisms of axon guidance are being deciphered by the identification of several gene families encoding cues for guiding axonal growth cone and cell migrations. These genes include members of the immunoglobulin superfamily, ephrins, semaphorins, slits, and netrins (Tessier-Lavigne and Goodman, 1996; Chisholm and Tessier-Lavigne, 1999). Some of these proteins clearly function as contact-mediated short-range attractive or repulsive guidance cues, whereas others are diffusible and act over long distances to guide axons toward or away from the sites of their synthesis.

Netrin-1 and -2 are chemoattractive factors first identified by biochemical purification of molecules that have commissural axon outgrowth-promoting activity (Kennedy et al., 1994; Serafini et al., 1994). UNC-6 is the ortholog of netrins in Caenorhabditis elegans. In vertebrates, netrins play a role in both attracting alar plate axons along the entire rostrocaudal axis toward the ventral midline or floor plate (Kennedy et al., 1994; Shirasaki et al., 1996) and repelling trochlear motor axons away from the midline (Colamarino and Tessier-Lavigne, 1995). Genetic analysis in C. elegansand single cell analysis in Xenopus spinal neurons reached the conclusion that these dual (attractive and repulsive) effects are transduced by a single ligand via two distinct receptor subfamilies that belong to the immunoglobulin superfamily (de la Torre et al., 1997; Hong et al., 1999). Attractive effects are transduced via receptors of the DCC (Deleted in colorectal cancer) subfamily to which UNC-40 of C. elegans, the Frazzled protein ofDrosophila, and DCC and neogenin of vertebrates belong (Chan et al., 1996; Keino-Masu et al., 1996; Kolodziej et al., 1996; de la Torre et al., 1997). In contrast, some of the repulsive effects of netrins require a member of the UNC-5 family in addition to a member of the UNC-40/DCC family (Hedgecock et al., 1990; Hong et al., 1999). In mammals, three UNC-5 receptor family members, UNC5H1, UNC5H2, and UNC5H3/RCM (rostral cerebellar malformation), have been isolated (Ackerman et al., 1997; Leonardo et al., 1997a). All members of both receptor subfamilies bind to netrins.

It has been thought that netrins and UNC-6 constitute a phylogenetically conserved small protein family (Chisholm and Tessier-Lavigne, 1999). Unlike other axon guidance molecules, i.e., semaphorins (Dodd and Schuchardt, 1995) and ephrins (Flanagan and Vanderhaeghen, 1998), at most two closely related members of UNC-6/netrin family have been isolated in each species examined to date. The high degree of divergence among semaphorins and ephrins might reflect their contributions to the formation of the complex and highly organized neuronal networks in vertebrates. Thus, it would be interesting to determine how extensively the UNC-6/netrin family has diverged during evolution.

Here we describe the identification and characterization of a novel member of the UNC-6/netrin family in mice, namely netrin-G1. Unlike classical netrins, netrin-G1 is predominantly linked to the plasma membrane by a glycosyl phospatidylinositol (GPI) lipid anchor and has a large number of isoforms probably generated by alternative splicing. Moreover, netrin-G1 neither binds receptors for classical netrins nor shows functional redundancy with netrin-1 in in vitro assays for axon guidance. The data suggest that netrin-G1 was elaborated in vertebrates. Its unique expression pattern and its predicted ability to act locally suggest that netrin-G1 plays a role in nervous system development that differs in detail from the classical netrins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Signal sequence trap and full-length cDNA cloning.The day of birth was considered as postnatal day 0 (P0). Total RNA from P21 mouse cerebellum was extracted by the guanidinium thiocyanate method (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 1987). Poly(A+) RNA was selected with the QuickPrep mRNA Purification kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). The cDNA library was synthesized from 3 μg of poly(A+) RNA according to Yabe et al. (1997). In brief, first-strand cDNA was primed with 40 pmol ofXhoI unidirectional primer: 5′-GAGACGGTAATACGATCGACAG-TAGCTCGAGNNNNNNNNN-3′. After deoxy-adenosine tailing, second-strand cDNA was synthesized with 10 pmol of EcoRI-linker primer: 5′-CCGC-GAATTCTGACTAACTGATTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTNN-3′. The double-stranded cDNA was size-fractionated (300–800 bp) by agarose gel electrophoresis and amplified by PCR with external primers: 5′-GACGGT-AATACGATCGACAGTAGC-3′ and 5′-CCGCGAATTCTGACTAAC- TGATT-3′. PCR products were digested with EcoRI andXhoI, size-fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis again, and ligated unidirectionally to EcoRI andXhoI sites of pSuc2t7F1ori vector (Yabe et al., 1997). In this vector, cDNA was inserted upstream of the invertase gene lacking its signal sequence and downstream of the yeast ADH1 promoter for efficient expression.

For screening of cDNA containing the signal sequence, this library was introduced into the invertase-deficient yeast strain YT455 (Suc2D9, ade2–101, ura3–52) (Jacobs et al., 1997), which does not normally grow on raffinose. Transformants capable of secreting invertase, because of its fusion with the signal encoding sequences derived from the netrin-G1 cDNA, could grow on these plates. Inserted cDNAs were amplified with a set of primers, 5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCCAAGCATACAAT- CAACTCCAAGCTC-3′ and 5′-TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTACTCC- TCTGAAATTAATACGACTCAC-3′, and the amplified DNAs were spotted to nylon membranes in duplicate. These membranes were hybridized with 32P-labeled cDNA directly synthesized from mRNA samples of either P0 or P21 mouse cerebellum. The sequences of clones that showed differential hybridization signals were determined by automated sequencer (ABI Prism 377; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the BigDye Primer Cycle Sequencing method (Applied Biosystems).

To obtain full-length cDNA clones, 2.5 × 106 phage plaques of P0 and adult mouse brain cDNA libraries (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) were screened with the32P-labeled 7D5 cDNA fragment that was isolated by the signal sequence trap method. Inserts of phages were excised in vivo following the instructions of the manufacturer.

Northern blot hybridization. An adult mouse tissue Northern blot was purchased from Clontech (Cambridge, UK). Poly(A+) RNA of P0 and P21 mouse cerebellum was extracted as mentioned above. Two micrograms of poly(A+) RNA was electrophoresed through 1% agarose gel and transferred to Hybond N filters. These filters were hybridized with 32P-labeled cDNA probes of the clone 7D5. The filters were washed for 30 min at 65°C twice with 2× SSC and 0.1% SDS and then twice with 0.2× SSC and 0.1% SDS. Membranes were analyzed using an image analyzer (BAS 5000; Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan).

Reverse transcription-PCR analysis. Total RNA from various mouse brain regions was extracted as above. For reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, 5 μg of DNase I-treated total RNA was reverse-transcribed with Superscript II (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), and 1:50 volume (100 ng of total RNA) of reaction mixture was subjected to PCR amplification. To confirm isoform varieties, a primer set of 5′-CCTGTATCCCCAGCATTTCC-3′ and 5′-AGCAGCAGTGCTGGGGAGCC-3′ was used. These primers corresponded to nucleotide sequences of LE1 (+1058 to +1077 nt of netrin-G1a) and domain C′ (+1558 to +1577 nt ofnetrin-G1a), respectively, resulting in amplification of isoforms netrin-G1a to netrin-G1e. Reaction conditions were 96°C for 3 min, then 33 cycles of 96°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, and finally 72°C for 7 min. The isoform specificity of amplified fragments was confirmed by Southern hybridization using isoform-specific probes. Fornetrin-G1a and netrin-G1b, the nucleotide sequence corresponding to LE2 and 3 (+1087 to +1389 nt ofnetrin-G1a) was used as a probe. For netrin-G1dand netrin-G1e, the fragment containing coding sequence for the 42 amino acid (aa) insert of netrin-G1d (+1087 to +1212 nt of netrin-G1d) was used. For netrin-G1c, the internal sequence corresponding to domain C′ (+1390 to +1531 nt ofnetrin-G1a) was used.

Construction of mammalian expression vectors. Entire coding sequences of netrin-G1a and netrin-G1dwere ligated into pcDNA4Myc/HisA (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) atEcoRI and PmeI sites, resulting in synthesis of intact proteins. The resulting constructs were used for the experiments of phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC) treatment.

To maximize extracellular secretion of netrin-G1a, netrin-G1b, netrin-G1d, and netrin-G1e on mammalian cell lines, coding sequences of these isoforms, except for their C-terminal sequences, were also subcloned into pcDNA4Myc/HisA (Invitrogen). In brief, the sequences for the C-terminal 26 hydrophobic amino acids of netrin-G1 was replaced with a spacer sequence containing an ApaI site and ligated into EcoRI/ApaI sites, resulting in C-terminal fusion to Myc/His-tag sequences.

cDNAs of netrin receptors were kind gifts from Dr. Marc Tessier-Lavigne (University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA) (Unc5h1, Unc5h2, and DCC; pCEP4-DCC) and Dr. Susan Ackermann (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) (Unc5h3/rcm). cDNA of chicken netrin-1(pGNet1myc) was also a gift from Dr. Marc Tessier-Lavigne. Coding sequences for cytoplasmic domains of UNC5H1, UNC5H2, and UNC5H3/RCM were replaced with enhanced cyan fluorescent variant of the Aeguorea victoria green fluorescent protein (ECFP) coding sequences in frame, resulting in fusion proteins that were composed of extracellular and transmembrane domains from receptors and cytoplasmic ECFP. To construct expression vectors, 1.7 kbNaeI fragment of Unc5h1 cDNA, 1.7 kbEco47III/SmaI fragment of Unc5h2, and 2.2 kb EcoRI/BalI fragment ofUnc5h3/rcm were subcloned into the SmaI site of pECFP (Clontech).

PI-PLC treatment and Western blot analysis. HEK293T cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 2 mml-glutamine and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). The cells were seeded at the concentration of ∼4 × 106 cells per 10 cm tissue culture dish. After 24 hr, cells at 80% confluence were transfected with 20 μg of the expression vectors (without epitope fusion) using the CellPhect transfection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). After 40 hr, transfected cells were incubated in 8 ml of OptiMEM I (Life Technologies) for 2 hr at 37°C with or without 100 mU/ml PI-PLC (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The culture media (1.5 ml) from PI-PLC-treated and nontreated cultures were clarified by centrifugation at 2000 × g for 10 min and then at 60,000 × g for 100 min. These supernatants were TCA-precipitated, and pellets were dissolved with SDS sample buffer. Cells cultured without PI-PLC were lysed with 750 μl of modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% cholate, 0.1% SDS, and 20 mm EDTA). These samples were fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to polyvinyl difluoride membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Recombinant netrin-G1 was detected with the affinity-purified rabbit anti-netrin-G1 antibody and HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Zymed, San Francisco, CA) as a secondary antibody and visualized using the ECL system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Antibody preparation. The sequences corresponding to the domain VI of netrin-G1a (aa 44–259) was cloned into the pGEX-2T (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and fused to glutathioneS-transferase gene. The fusion protein was expressed in Escherichia coli by the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside induction and purified with a glutathione column. Rabbits were immunized several times with the purified antigens together with Freund's complete and incomplete adjuvants. Antisera were affinity-purified against the (His)6-tagged domain VI proteins (aa 66–116). To synthesize the (His)6-tagged domain VI proteins, the corresponding sequences were cloned into pET-32a (Novagen, Madison, WI). The fusion protein expressed in E. coli was purified with an Ni-NTA column (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and coupled to HiTrap NHS-activated affinity columns (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

In situ hybridization. To make netrin-G1 probes, signal sequence-trapped cDNA sequences of the 7D5 clone were transferred intoEcoRI and XhoI sites of pSP72 (Promega). Antisense and sense riboprobes were labeled with digoxigenin-dUTP from linearized templates using SP6 and T7 RNA polymerases (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), respectively. In situhybridization of whole-mount and frozen sections of mouse brain was performed according to the procedures described previously (Wilkinson et al., 1987; Conlon and Rossant, 1992; Suzuki et al., 1997). Vibratomeslices (300-μm-thick) were stained as whole-mount samples. Frozen sections were made at 20 μm thickness. Hybridization signals were detected with anti-digoxigenin Fab fragment (Boehringer Mannheim) and BM purple.

Receptor binding experiments. The recombinant proteins of myc-tagged netrin-1 and myc-tagged soluble form of netrin-G1a, netrin-G1c, netrin-G1d, and netrin-G1e were recovered as conditioned media from stable transformants cultured for several days. Quality and quantity of fusion proteins in the conditioned media were determined by Western blot analysis using anti-myc antibody (9E10) and HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Relative concentrations of fusion proteins were measured by an image analyzer (LAS100; Fuji). The minimum concentration of netrin-1 to bind to receptors in the experimental conditions was determined by serial dilution of the conditioned media. For concentrating soluble forms of netrin-G1a, netrin-G1c, netrin-G1d, and netrin-G1e, Centriprep-30 concentrator (Amicon, Beverly, MA) was used. This treatment did not cause aggregation of secreted netrin-G1.

Expression vectors for the UNC5 family were transfected into COS7 cells, and pCEP4-DCC was transfected into HEK293EBNA cells (Invitrogen). At 48 hr after transfection, myc-tagged recombinant proteins were added to culture medium supplemented with 10% FCS and 20 μg/ml heparin (Sigma) and incubated for 90 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS one or four times, cells were fixed with MeOH for 5 min, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min. In the case of the UNC5 family, binding of the recombinant proteins was detected using monoclonal anti-myc antibody (9E10) and Alexa 546-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Cell surface expression of receptors on transfected cells were visualized by ECFP fluorescence. In the case of DCC, double staining was performed using monoclonal anti-DCC antibody (Oncogene Science, Uniondale, NY) and affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal anti-myc antibody. The binding of these primary antibodies was visualized by Alexa 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes) and Alexa 546-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes), respectively. Fluorescence images were acquired by a CCD camera (Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ) with MetaMorph software (Roper Scientific).

Explant culture. Procedures for explant culture in collagen gel followed those of Shirasaki et al. (1995). Mouse embryos at embryonic day 12 (E12) were dissected in DMEM–F12 medium (Sigma) supplemented with glucose. Cerebellar plate explants were obtained from open-book preparations of the hindbrain region. Aggregates of stable cell lines (HEK293T cells) expressing netrin-1, the secreted form of netrin-G1a, or netrin-G1d were prepared as described previously (Kennedy et al., 1994). The explants and the aggregates were embedded in collagen matrix, which were prepared from rat tail tendon. The culture medium used was DMEM–F12 supplemented with 3.85 mg/ml glucose, 10 mg/ml streptomycin, 100 μg/ml transferrin, 5 μg/ml insulin, 5.29 ng/ml sodium selenite, 16.4 μg/ml putrescine dihydrochloride, 6.29 ng/ml progesterone, 7.40 ng/ml hydrocortisone, and 10% FCS.

RESULTS

Isolation of a novel member of the UNC-6/netrin family: netrin-G1 (clone 7D5)

To systematically analyze molecules responsible for intercellular communication in cerebellar development, we constructed signal sequence trap cDNA libraries from P21 mouse cerebellum. The signal sequence trap method, which was aided by the invertase-deficient yeast strain (Jacobs et al., 1997), allowed us to selectively isolate cDNAs encoding both secreted and membrane proteins (Tashiro et al., 1993). We further predicted that the expression of genes involved in development might show differential expression during different developmental stages. Thus, we amplified cDNA inserts from individual clones by PCR, spotted them onto nylon membranes in duplicate, and then hybridized them with32P-labeled cDNA probes from either P21 or P0 mouse cerebellum. Then, we determined the nucleotide sequences of cDNA clones displaying differential expression. Among these, clone 7D5 showed similarity to UNC-6/netrins.

Figure 1 represents the expression profile of the clone 7D5. A single band of ∼4.5 kb in size was detected by Northern blot analysis using the trapped fragment as a probe. The 7D5 transcript was strongly expressed in P0 cerebellum and downregulated by P21 (Fig. 1A). Northern blot analysis of adult tissues detected hybridization signals only with brain (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Expression of 7D5 in the brain. A, Expression profile of 7D5 during cerebellar development. Poly(A+) RNAs from P0 and P21 mouse cerebellum were electrophoresed (2 μg/lane), transferred onto a nylon membrane, and hybridized with a 32P-labeled cDNA (7D5). The expression of 7D5 was characterized by downregulation in postnatal development. G3PDH was used as a control for loading of RNA. B, Tissue distribution of 7D5 in adult mice. An adult mouse multiple tissue Northern blot (Clontech) was hybridized with the probe mentioned above. 7D5 was specifically expressed in the brain. β-actin was used as a control for loading of RNA. Arrowheads inA and B indicate 7D5 signals.

To isolate full-length cDNA clones encoding the 7D5 gene, we screened oligo-dT-primed cDNA libraries prepared from adult and P0 mouse brains with the trapped cDNA fragment as a probe. Thirty-nine overlapping clones were isolated and sequenced. The longest cDNA fragment was 4090 nucleotides in length. A putative open reading frame of this clone included 539 amino acids (Fig. 2). As expected, the sequences of trapped cDNA fragment (7D5) corresponded to sequences of the N-terminal 180 aa (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

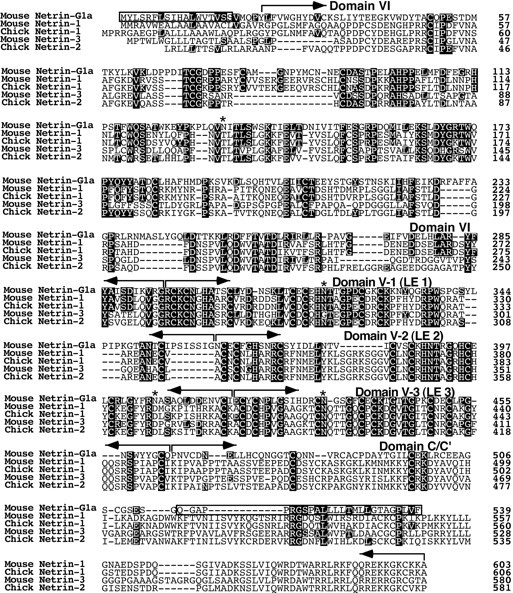

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of netrin-G1a (7D5) with vertebrate netrins. Amino acid residues identical between netrin-G1a and other netrins are in black. Hydrophobic stretches (boxed) of netrin-G1a appear to be signals for secretion and for GPI linkage predicted by the ω and ω + 2 rules (Gerber et al., 1992; von Heijne, 1996), respectively. Thebrackets above the sequences indicate domain structures (domains VI, V-1, V-2, V-3, and C′) of netrin-G1a defined by homology with other netrins. Asterisks indicate the putative N-glycosylation sites of netrin-G1a. The nucleotide sequences of netrin-G1a and other isoforms have been submitted to the GenBank (accession numbers AB038662, AB038663, AB038664, AB038665, AB038666, and AB038667).

The deduced amino acid sequence showed a weak similarity to chick netrin-1, netrin-2, and mouse netrin-1 and netrin-3 (31, 30, 29 and 29% identity, respectively) (Figs. 2,3A). The predicted domain structure of this protein resembled that of the UNC-6/netrin family, i.e., laminin globular domain (domain VI) followed by three laminin epidermal growth factor-like (LE) repeats (domain V-1 to V-3) (Hutter et al., 2000) (Figs. 2, 3A). The Cys-residues phylogenetically conserved among the UNC-6/netrin family are also conserved in these domains of the 7D5 gene, further supporting structural similarity of 7D5 to UNC-6/netrins. Originally, UNC-6 was identified as a laminin-related protein, because the N-terminal two-thirds of UNC-6 were homologous to the N-terminal domains (domain VI and domain V) of laminin β and γ chains, components of large heterotrimeric extracellular matrix molecules (Ishii et al., 1992). The 7D5 gene encodes a protein with these same characteristics. Similar to UNC-6 and classical vertebrate netrins, 7D5 is more related to the γ chain than the β chain in these domains (32% identical with mouse γ chain vs 27% with β chain) but has hallmarks of both. Based on these findings, we concluded that 7D5 is a novel member of the UNC-6/netrin family and named it netrin-G1. However, it should be noted that netrin-G1 is the most distant member among this family of proteins (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Structural comparison of netrin-G1 and other UNC-6/netrins. A, Domain structures of members of the UNC-6/netrin family are schematically represented. The percent identity in amino acid sequence between homologous domains is shown. Netrin-G1a is anchored on cell membrane by a GPI linkage, whereas netrin-1 and netrin-3 are secreted. The C domains of classical netrins are highly charged (indicated by ++). The C-terminal sequence of netrin-G1a, named C′, is distinctly different from the C domain of classical netrins.B, Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity plot of deduced netrin-G1a and mouse netrin-1 amino acid sequences. Two hydrophobic stretches were observed at both N and C termini in netrin-G1a. The latter stretch is unique to netrin-G1 among members of the UNC-6/netrin family. C, A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the amino acid sequences of C. elegans UNC-6 (P34710), chick netrin-1 (Q90922), chick netrin-2 (Q90923), mouse netrin-1 (AAC52971), mouse netrin-3 (AAD40063), human netrin-1 (NP004813), human NTN2L (NP006172), zebrafish netrin-1 (AAB70266), zebrafish netrin-1a (AAC60252), Drosophila netrin-A (Q24567),Drosophila netrin-B (Q24568), and netrin-G1a (AB038667) using CLUSTAL X program (ftp://ftp-igbmc.u-strasbg.fr/pub/ClustalX/). Netrin-G1 is evolutionarily distant from other members of the family, implying that the netrin-G1 may serve as a prototype of a novel subfamily.

The characteristic difference between netrin-G1 and other members was observed in its C-terminal sequences. Whereas C-terminal sequences (domain C) of chick netrin-1 and netrin-2 are rich in basic amino acids, such as lysine residues, the corresponding domain of netrin-G1 is not rich in these amino acids. Furthermore, the C-terminal end sequences of netrin-G1 are hydrophobic, unlike other members (Fig.3B). Thus, we termed this domain C′. We predicted that this C-terminal hydrophobic stretch might play a role as a signal for GPI linkage to the membrane and expected that netrin-G1 might localize on cell membranes. The “G” in the name emphasizes the GPI linkage of this protein.

Isoforms of netrin-G1

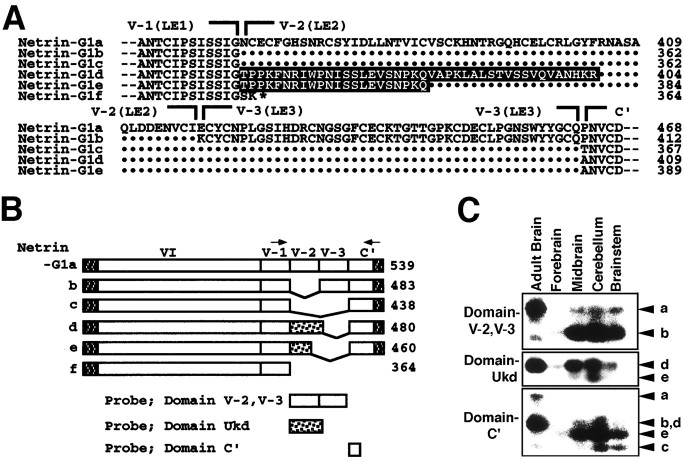

Sequence comparison of 39 independent cDNA clones revealed the existence of six variants presumably generated by alternative splicing. These variants are schematically represented in Figure4B. The isoform having the longest amino acid sequence (netrin-G1a) most resembled the UNC-6/netrin family in terms of domain structure. Netrin-G1b and netrin-G1c had a deletion of one or two units of LE repeats (LE2 or LE2 and LE 3), respectively (Fig.4A,B). Netrin-G1d and netrin-G1e had either a 42 or 22 aa insertion between domains of LE1 and C′, respectively (Fig. 4A,B). The insertions in netrin-G1d and netrin-G1e were identical at their N-terminal halves, but that of netrin-G1d was 20 aa longer than that of netrin-G1e. GenBank database search did not reveal homology of the inserted domains to any known proteins. The shortest isoform, netrin-G1f, was found in only one case and lacked domains LE2, LE3, and C′ (Fig. 4A,B). The human cDNA clone KIAA0976, with 96% identity throughout the coding region, is likely the human ortholog of netrin-G1f (Nagase et al., 1999). The cDNA clones encoding netrin-G1a, netrin-G1b, netrin-G1c, netrin-G1d, netrin-G1e, and netrin-G1f were obtained in 7, 1, 3, 8, 5, and 1 of 25 clones, respectively. The remaining 14 clones had partial coding sequences, and their isoform could not be determined. In conclusion, isoforms of netrin-G1 have diversified C-terminal structures, whereas their N-terminal VI and LE1 domains are more conserved.

Fig. 4.

Structure and expression of G1 isoforms.A, Six isoforms are named netrin-G1a to netrin-G1f. Sequences around and including variable regions of the isoforms are aligned. Netrin-G1a most resembles mouse netrin-1 and netrin-3 in terms of modular structure and predicted sequences of LE modules. Netrin-G1b and netrin-G1c lack domain V-2 (LE2) and domains V-2 and V-3 (LE3), respectively. Netrin-G1d has an insert of 42 aa, tentatively named Ukd for “Unknown domain.” Sequences are in black, between domains V-1 (LE1) and C′. Netrin-G1e has a shorter Ukd. All five of these isoforms (netrin-G1a to netrin-G1e) contain domains VI, V-1, and C′. Netrin-G1f lacks domains V-2, V-3, and C′. This isoform is exceptional in that it does not contain the C-terminal hydrophobic stretch. Dots indicate missing residues.Hyphens at both ends represent extending sequences.B, Schematic representation of netrin-G1 isoforms. N- and C-terminal hydrophobic stretches are indicated as shaded boxes, and domain Ukd of netrin-G1d and netrin-G1e is indicated as dotted boxes. C, RT-PCR analysis of five isoforms in adult whole brain and various regions of P0 brain. RT-PCR was performed using a set of primers, indicated byarrows in B, corresponding to nucleotides of LE1 and domain C′, respectively. This set of primers amplified the fragments of all netrin-G1s, ex-ceptnetrin-G1f, with the expected sizes of 520, 352, 217, 343, and 283 bp for netrin-G1a,netrin-G1b, netrin-G1c,netrin-G1d, and netrin-G1e, respectively. To discriminate between these bands, isoform-specific probes indicated to the left in C were used for Southern blot hybridization. Isoforms are indicated witharrowheads at the right.

Southern blot hybridization of genomic DNA and partial sequencing of genomic clones suggested that these isoforms were derived from a single gene and were presumably generated by alternative splicing (data not shown). To examine their regional and temporal distribution, we performed RT-PCR using a set of primers corresponding to nucleotides of LE1 (353–359 aa of netrin-G1a) and domain C′ (520–526 aa of netrin-G1a) (Fig. 4B). This set of primers would produce amplified bands of 520, 352, 217, 343, and 283 bp from netrin-G1a, netrin-G1b, netrin-G1c, netrin-G1d, and netrin-G1e, respectively. To discriminate these products, we performed Southern blot hybridization using variant-specific internal probes (Fig.4B,C). The probe corresponding to LE2 and LE3 (363–463 aa of netrin-G1a) confirmed the existence of netrin-G1a and netrin-G1b. A probe that included coding sequences for the 42 aa insert of netrin-G1d detected netrin-G1d and netrin-G1e. The shortest fragment revealed by the C′ probe (464–511 aa of netrin-G1a) was identified as the product of netrin-G1c. Because amplification efficacy of these isoforms may differ, we were not able to accurately estimate relative amounts of isoforms. However, the results suggested that all isoforms were generated at perinatal stages and that netrin-G1a and netrin-G1d were likely to be the major isoforms in adult brains (Fig. 4C), consistent with the results of cDNA cloning.

Netrin-G1 is linked to the cell membrane by GPI lipid anchors

Hydrophobicity plots of netrin-G1a revealed two hydrophobic sequences at both ends, unlike netrin-1 (Fig. 3B). The predicted N-terminal signal sequence (von Heijne, 1986) supported secretion of invertase in yeast, although this activity remains to be confirmed in mammalian cells. The signal sequence is consistently observed in members of the UNC-6/netrin family. However, the C-terminal hydrophobic sequence was unique to netrin-G1 and was likely to be a GPI lipid anchor.

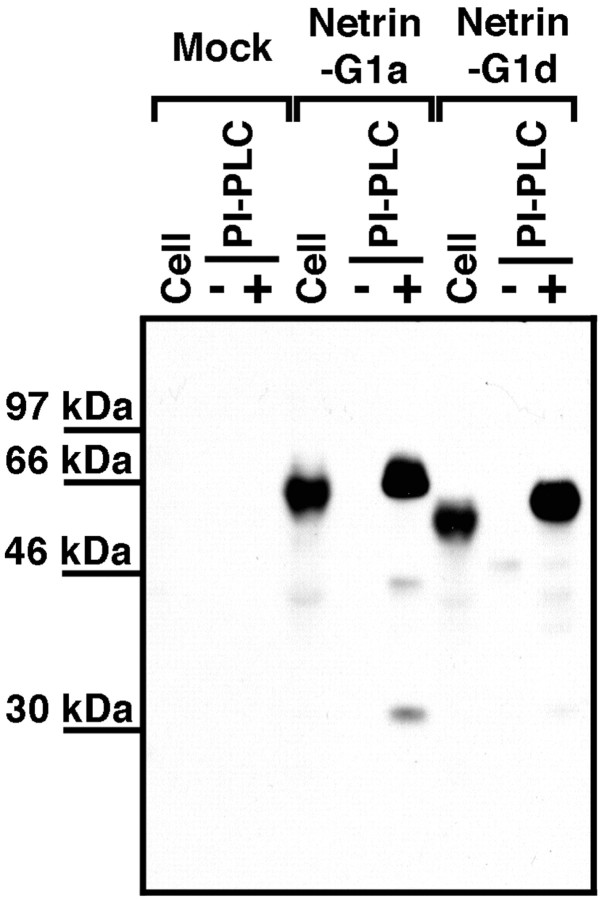

To confirm these possibilities, we expressed recombinant netrin-G1a and netrin-G1d in HEK293 cells. Immunoblotting analysis with affinity-purified antibodies against the common domain (domain VI) of netrin-G1 detected both isoforms in cell lysates (Fig.5), indicating successful synthesis of recombinant proteins. Two hour exposures of transfected cells to PI-PLC, which specifically cleaves GPI-anchored proteins from the membrane surface, released the recombinant proteins into the supernatants (Fig. 5). On the other hand, the same treatment without PI-PLC did not release substantial amounts of recombinant protein (Fig.5). These results indicate that at least these isoforms, and perhaps all but one (netrin-G1f), were predominantly anchored to the cell membrane via GPI anchors.

Fig. 5.

PI-PLC sensitivity of recombinant netrin-G1a and netrin-G1d. Netrin-G1a and netrin-G1d were transiently expressed in HEK293T cells. At 60 hr after transfection, transfected HEK293T cells were incubated with or without 200 mU/ml PI-PLC in OptiMEM at 37°C for 2 hr. The supernatants were clarified by ultracentrifugation and TCA-precipitated. The cell lysates were obtained from cells not treated with PI-PLC. These samples were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and probed with affinity-purified anti-netrin-G1 polyclonal antibodies against domain VI. Note that these isoforms were released from transfected cells by PI-PLC treatment.

The calculated molecular weights of nascent netrin-G1a and netrin-G1d were 60.5 and 53.9 kDa, respectively. The cleavage site for GPI anchoring was predicted from the ω and ω + 2 rule (Fig. 2) (Gerber, 1992). The calculated molecular weights of these processed proteins were 55.9 and 49.3 kDa, respectively. The sizes estimated from immunoblotting analysis were slightly larger than these calculated sizes (Fig. 5), suggesting that these proteins might be subject to post-translational modification. Putative N-linked glycosylation sites are depicted in Figure 2. This modification was confirmed by N-glycosidase F treatment (data not shown). In Figure 5, recombinant proteins released by PI-PLC treatment migrated slower than those from cell lysates. Perhaps, lipid moieties associated with recombinant proteins might have affected the migration rates of these proteins.

Expression of netrin-G1 in the CNS

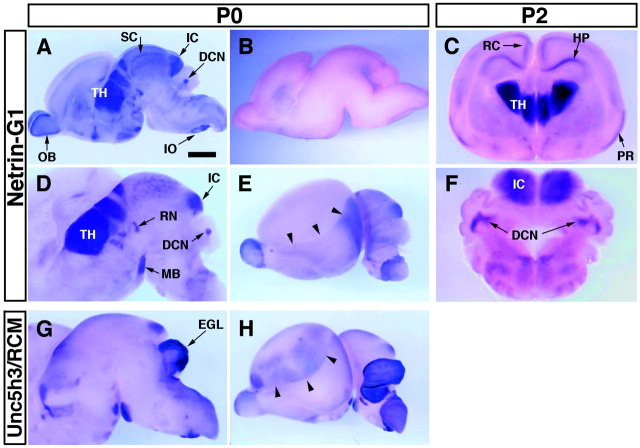

To determine the regional distribution of netrin-G1 in detail, we performed in situ hybridization analysis in mouse brains using the N-terminal coding sequence as a common probe for all isoforms. In situ hybridization of parasagittal sections of P0 brain indicated that netrin-G1 was expressed in a regionally restricted manner (Fig.6A–F). The strongest expression was detected in the thalamus (Fig.6A,D). Moderate expression was detected in the olfactory bulb, inferior and superior colliculi, red nucleus, mammillary body, deep cerebellar nuclei, and inferior olive nuclei (Fig. 6A,D). In vibratome coronal slices of P2 brain, strong expression was detected in each of the thalamic nuclei (Fig. 6C), and moderate expression was seen in the inferior colliculus and deep nuclei of the cerebellum (Fig.6F). Weak but appreciable expression was further detected in piriform cortex, retrosplenial granular cortex, and CA1–CA3 of the hippocampal formation (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Regional distribution ofnetrin-G1 transcripts in mouse brain revealed byin situ hybridization. Parasagittal cuts of the P0 mouse brain (A, B, D,E, G, H) and P2 coronal vibratome slices of the P2 mouse brain (C,F) were hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled antisense cRNA probes specific for netrin-G1(A–F, except for B) orUnc5h3/rcm (G, H). Sense probe for netrin-G1 showed no signal under the conditions used (B). In the lateral views of cerebral hemisphere, distributions of netrin-G1(E) and Unc5h3/rcm(H) were complementary and delineated the boundary (arrowhead) between neocortex and allocortex. Scale bar: A, B, E,H, 1 mm ; C, 0.85 mm; F, 0.65 mm; D, G, 0.8 mm.DCN, Deep cerebellar nuclei; EGL, external germinal layer; HP, hippocampal formation;IC, inferior colliculus; IO, inferior olive; MB, mammillary body; OB, olfactory bulb; PR, piriform cortex; RN, red nucleus; RC, retrosplenial cortex; SC, superior colliculus; TH, thalamus.

The expression of netrin-G1 showed marked contrast with that of Unc5h3 in some brain areas (Fig.6G,H). For instance, Unc5h3 was strongly expressed in the external germinal cell layer and Purkinje cell layer of the cerebellum (Fig. 6G) (Ackerman et al., 1997), whereas netrin-G1 was found in the deep cerebellar nuclei (Fig. 6D). Similar to Unc5h3, all other netrin receptors have been reported to be expressed in the external germinal cell and internal granule cell layers (Leonardo et al., 1997b). Only DCC among the netrin receptors is known to be expressed in the deep cerebellar nuclei (Livesey and Hunt, 1997). Curiously, in the cerebral cortex, netrin-G1 andUnc5h3 were expressed in allocortical and neocortical areas (Fig. 6E,H), respectively, and delineated the boundary between allocortex and neocortex.

Ontogenic expression of netrin-G1 in representative regions was examined by in situ hybridization (Fig.7). The expression ofnetrin-G1 was detected in the midbrain and hindbrain regions as early as E12, whereas whole-mount hybridization showed no signals in any region at E10 (data not shown). In the deep nucleus of the cerebellum, expression of netrin-G1 was detected at E14 (Fig. 7C), persisted to P0 (Fig. 7F), and was downregulated by P21 (Fig. 7I), being in good agreement with the results of the Northern analysis (Fig.1A). The inferior colliculus followed a similar time course of netrin-G1 expression at postnatal periods (Fig.7F,I).

Fig. 7.

Ontogenic expression of netrin-G1. Ontogenic expression of netrin-G1 was examined byin situ hybridization using frozen parasagittal sections, except for B. The digoxigenin-labeled antisense cRNA for netrin-G1 was used as a probe. At E14, expression of netrin-G1 was initially detected in accessory olfactory bulb (OB), restricted in mitral cell layers (ML) and tufted cells (TF) at P0, and persisted to P21. In thalamus, expression was segmental in dorsal thalamus (DT) and pretectum (PT) at E14, peaked at perinatal stages and downregulated in postnatal development. In cerebellum, expression of netrin-G1 was also detected at E14, restricted in deep nucleus (DCN) and downregulated postnatally by P21 in contrast to olfactory bulb. IC, Inferior colliculus;TH, thalamus. Scale bar: A, 0.42 mm; B, E, H, 1 mm;C, 0.5 mm; D, 0.38 mm; F, 0.6 mm; G, 0.27 mm; I, 1.2 mm.

At E14, expression of netrin-G1 was segmented in dorsal thalamus and pretectum in the midbrain (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, its expression was regulated in a layer-specific manner in the superior colliculus (Figs. 6A, 7E). The netrin-G1 expression in thalamic regions seemed to take a time course similar to that in the cerebellum (Fig.7E,H). In the olfactory bulb, expression of netrin-G1 was detected at E14 (Fig.7A), increased by P0 (Fig. 7D), and was maintained at a high level through P21 (Fig. 7G) and into adulthood (data not shown).

Netrin-G1 does not bind to netrin receptors

All previously identified members of the UNC-6/netrin family bind to known netrin receptors, i.e., the UNC5 family (UNC5H1, UNC5H2, and UNC5H3/RCM in mammals) (Leonardo et al., 1997a) and the UNC40 family (DCC and neogenin in mammals) (Keino-Masu et al., 1996). To examine whether netrin-G1 has functional redundancy with UNC-6/netrins, we tested the binding activities of netrin-G1 to netrin receptors.

The extracellular and transmembrane domains of UNC5H3/RCM, UNC5H1, and UNC5H2 were C-terminally fused with ECFP, a variant of green fluorescence protein, and transiently expressed in COS7 cells. Membrane fluorescence allowed us to monitor successful expression of the receptor molecules. These cells were incubated with myc-tagged netrin-G1 and myc-tagged chick netrin-1 proteins that were recovered from the supernatants of stably expressing cells. The hydrophobic C-terminal tails of netrin-G1 isoforms were deleted to maximize secretion.

In cultures incubated with chick netrin-1, UNC5H3/RCM-expressing cells reported by ECFP fluorescence were colabeled with anti-myc antibodies on their cell surfaces (Fig.8A,B), consistent with previously reported results (Leonardo et al., 1997a). In contrast, no signals were detected in cultures treated with a series of test ligands (myc-tagged netrin-G1a, netrin-G1b, netrin-G1d, and netrin-G1e) (Fig. 8D,F; and data not shown). The relative amounts of proteins used for these binding assays were estimated by immunoblotting with anti-myc antibodies. A representative result is shown in Figure 8K. These test ligands at over 100 times higher concentration relative to chick netrin-1 failed to show binding to UNC5H3/RCM. Thus, netrin-G1 is not likely to be a ligand for UNC5H3/RCM. Similarly, netrin-G1 did not show binding to UNC5H1 and UNC5H2 (data not shown).

Fig. 8.

Lack of affinity of netrin-G1 to netrin receptors. UNC5H3/RCM, with its cytoplasmic domain replaced with ECFP, was transiently expressed in COS7 cells. The receptor protein expression was detected with ECFP fluorescence (blue;A, C, E). DCC was expressed in HEK293EBNA cells and detected using mouse monoclonal anti-DCC antibody and Alexa 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (green; G,I). In the same field, binding of myc-tagged chick netrin-1 (Netrin-1/Myc) on the cells was detected by immunocytochemistry using a monoclonal anti-myc antibody (9E10) and Alexa 546-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (B) in the case of UNC5H3/RCM, and rabbit polyclonal anti-myc antibody and Alexa 546-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (H) in the case of DCC (red). However, secreted forms of myc-tagged netrin-G1a (sNetrin-G1a/Myc) and Netrin-G1d (sNetrin-G1d/Myc) did not show binding to the cells expressing both receptors, even at the higher concentrations (D, F, J). Similar results were obtained with cells expressing UNC5H1 or UNC5H2 receptors. sNetrin-G1c and sNetrin-G1e also did not show binding to cells expressing any type of receptor examined (data not shown).K represents relative concentrations of test ligands used in binding experiments, revealed by anti-myc immunoblotting. Shown are representative results from one of three independent experiments. Scale bar, 10 μm.

DCC belonging to another receptor family was also transiently expressed in HEK293 cells and tested for binding to netrin-G1. In this case, the expression of DCC was detected by immunocytochemistry using a DCC-specific monoclonal antibody (Fig.8G,I). Again, cells expressing DCC showed binding to chick netrin-1 but not to netrin-G1, even at more than 100 times higher concentrations (Fig.8H,J).

The detection of bound molecules, as well as determination of their relative concentrations, were done using anti-myc antibodies, raising the possibility of pseudonegative results by contamination of excess amounts of degraded products lacking the myc epitope tag. Thus, we assessed the quality of the test ligands by Western blot analysis using polyclonal antibodies against netrin-G1 domain VI and ruled out this possibility.

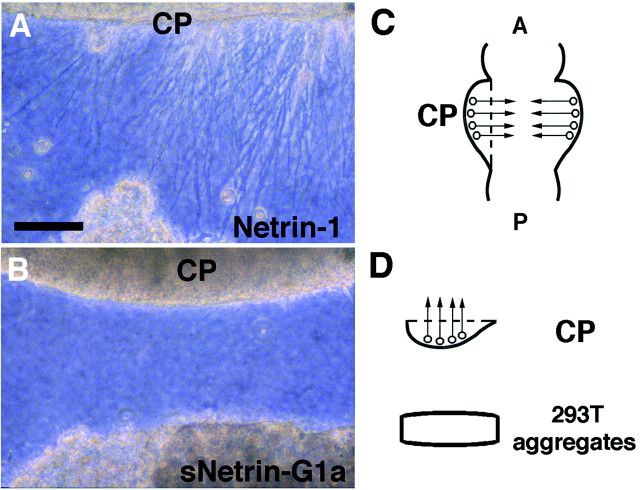

The results described above demonstrate a possible difference between netrin-G1 and classical netrins in receptor usage. To further rule out a functional redundancy between netrin-G1 and netrin-1, we performed three-dimensional collagen explant coculture experiments using the dorsal side of spinal cord and cerebellar plate. Netrin-1 secreted from transformed cells showed outgrowth-promoting and attractive activities to commissural and cerebellofugal axons (Fig.9A), as reported previously (Kennedy et al., 1994; Serafini et al., 1994; Shirasaki et al., 1995). However, secreted soluble forms of netrin-G1 did not elicit outgrowth of these axons (Fig. 9B), consistent with the results of the binding assays. From these experiments, we cannot conclude that netrin-G1 is a ligand for the known netrin receptors.

Fig. 9.

Netrin-G1 cannot compensate for netrin-1 activity in collagen gel cerebellar plate explant culture. Cerebellar plates (CP) from E12 mice were cocultured with aggregates of HEK293T cells expressing either netrin-1 (A) or secreted forms of netrin-G1a (sNetrin-G1a;B) in collagen gels. Whereas netrin-1-expressing cells attracted axons from cerebellar plates (A), sNetrin-G1a did not elicit neurite outgrowth of cerebellar plate axons (B) (n = 8). Scale bar:A, B, 100 μm. C, Diagram showing a flat whole-mount preparation of embryonic mouse brain and the area used for explant coculture experiments. CP, Cerebellar plate. Arrows indicate the axon orientation in the cerebellar plate. D, The lateral surface of the cerebellar plate explant was faced with the HEK293T aggregates.

DISCUSSION

We have screened cDNA fragments of putative secreted and membrane proteins by a signal sequence trap method and identified a novel member of the UNC-6/netrin family. The new member, netrin-G1, has many characteristic features different from other members, the so-called classical netrins, in terms of their isoform diversity, expression, and relationship to known netrin receptors.

Divergence of the UNC-6/netrin family

Members of the UNC-6/netrin family are laminin-related small proteins. Laminins are heterotrimeric extracellular matrix proteins of α, β, and γ chains, and the N-terminal portion of each chain consists of one globular domain (domain VI) followed by several LE repeats (domain V) (Sasaki et al., 1988; Beck et al., 1990; Timpl and Brown, 1994; Hutter et al., 2000). Members of the UNC-6/netrin family are characterized by their conserved domain structures from domain VI to the third LE repeat of domain V of laminins (Ishii et al., 1992;Serafini et al., 1994; Engvall and Wewer, 1996). Although the level of overall homology of netrin-G1 to any known member of UNC-6/netrin family is low, its domain organization is essentially identical to the classical members, providing a molecular basis to include this novel gene in the UNC-6/netrin family. This conclusion is further supported by the finding that, like other UNC-6/netrins (Ishii et al., 1992;Serafini et al., 1994), the netrin-G1 LE repeats have hallmarks of both γ and β chains of laminin, but they are more related to the γ chain than the β chain (32% identical with mouse γ chain vs 27% with β chain). It has been thought that the UNC-6/netrin family is a small one, because at most only two genes have been isolated in every species examined so far, such as the chick (Serafini et al., 1994), fly (Harris et al., 1996; Mitchell et al., 1996), mouse (Püschel 1999; Wang et al., 1999), and human (Van Raay et al., 1997). Netrin-G1 appears to be a third member in mouse as well as humans. On the other hand, the BLAST search for the complete genome sequences of C. elegance and D. melanogaster failed to show orthologs of netrin-G1 in these species. Netrin-G1 was likely elaborated within the vertebrate lineage. Phylogenetic analysis of the gene family (Fig. 3C) suggested thatnetrin-G1 has evolved independently from classical netrins, implying that netrin-G1 may be considered as a prototype of the subfamily. Indeed, we have evidence that a netrin-G2 candidate might exist in mouse.

The new netrin family member, netrin-G1, has several characteristics that differ from other netrins, the so-called classical netrins. One of these is found in its C-terminal sequences. Domain C of netrin-1 is rich in basic residues, such as lysine, and serves as a heparin binding site (Serafini et al., 1994). The basic C domain can bind cell surfaces via negatively charged molecules, such as proteoglycans. Therefore, it is thought that the range of diffusion of netrins is determined by the level of expression of netrins relative to the concentration of binding sites in the environment. The C-terminal sequence (named domain C′) of netrin-G1 is not rich in basic residues but does provide a signal for GPI linkage (Fig. 3). Transient expression in HEK293T cells and PI-PLC treatment clearly revealed that netrin-G1a and netrin-G1d are predominantly on the cell surface via GPI linkages. Thus, netrin-G1 is likely to be more specialized as a cue that acts close to the site of its synthesis. However, we do not rule out the possibility that netrin-G1 may diffuse far from the source under certain conditions. It has been suggested that GPI-anchored molecules, such as axonin-1/Tag-1, can be released from the membrane by an endogenously expressed glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase D and that the enzyme activity is detected in dorsal root ganglion neurons and brain (Lierheimer et al., 1997). In any case, a GPI anchor might characterize the netrin-G subfamily. The association of netrins with cell surface is a conserved feature of nervous system development but may have been dealt with differently in invertebrates and vertebrates.

Extensive cDNA analysis revealed that netrin-G1 has at least six isoforms (Fig. 4). The longest isoform, most resembling classical netrins in terms of domain structure, is named netrin-G1a. Netrin-G1b and netrin-G1c lack one and two of the three LE repeats, respectively. The LE motif is believed to be important for protein–protein interactions. Thus, these isoforms might have different binding properties to associated molecule(s). Indeed, a nematode C. elegans mutant strain lacking domain V-2 of UNC-6 shows a selective loss of UNC-5-mediated repulsive functions. Null mutants of the UNC-6 exhibit deficits in both dorsal and ventral guidance for circumferential axons (Hedgecock et al., 1990), but the V-2 deletion mutants show deficits only in dorsal guidance (Wadsworth et al., 1996), suggesting the existence of a critical domain for certain phenotypes. The insertions in netrin-G1d and netrin-G1e might further modulate their binding to associated molecule(s). Interestingly, semiquantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 4C) suggests that the alternative splicing might be regulated in a region- and developmental stage-specific manner. Alternative splicing may be a strategy for creating netrins with divergent functions.

Lack of affinity of netrin-G1 to netrin receptors

UNC5H1, UNC5H2, UNC5H3/RCM, DCC, and neogenin are receptors for the classical netrins in vertebrates (Keino-Masu et al., 1996; Ackerman et al., 1997; Leonardo et al., 1997a). Classical netrins can bind to all of these receptors. To explore possible functional redundancy, we examined the binding ability of netrin-G1a-myc, netrin-G1b-myc, netrin-G1d-myc, and netrin-G1e-myc to UNC5H3/RCM, as well as other netrin receptors transiently expressed on the surface of COS7 and HEK293 cells. Although netrin-1-myc used as a positive control bound to these receptors, indicating functional expression of receptor molecules, none of the test ligands showed detectable affinities to these receptors, even at 100 times higher concentrations relative to netrin-1-myc. We did not examine netrin-G1c and netrin-G1f. However, it is unlikely that these isoforms, resembling classical netrins to a lesser degree, show affinities to these receptors.

To further assess the potential interaction of netrin-G1 to naturally expressed netrin receptors, we performed in vitro explant coculture experiments using collagen gel matrices. It has been well established that commissural and cerebellofugal axons express receptors for netrin-1 and that netrin-1 promotes outgrowth of these axons and attracts them (Serafini et al., 1994; Shirasaki et al., 1995). Again, soluble forms of netrin-G1a did not show any detectable effect on these axons, unlike netrin-1. Results from the explant coculture experiments, together with those from receptor binding assays, suggested that netrin-G1 might have nonredundant functions with classical netrins. We suggest that netrin-G1 is specialized for receptor(s) different from known netrin receptors. However, we do not rule out the possibility that netrin-G1 may interact with known netrin receptors in the presence of a co-factor(s).

Expression and possible function of netrin-G1

As a putative function of netrin-G1, two possibilities should be considered. Based on its predicted structural similarity to classical netrins, it is expected that netrin-G1 may act as a chemoattractive and/or chemorepulsive cue for axonal growth and migration of cells expressing putative receptors for netrin-G1. Conversely, GPI-anchored netrin-G1 may transduce signals from the extracellular milieu, as shown for the CNTFα receptor (Davis et al., 1991), and play an autonomous role. It has been well documented that the engagement of GPI-anchored molecules triggers cascades involving tyrosine kinases of the src family in immune cells (Brown, 1993). Bidirectional signaling has been proposed for the ephrin/Eph receptor system, another axon guidance molecule (Bruckner et al., 1997; Araujo et al., 1998; Holder and Klein 1999, Davy et al., 1999).

The expression of netrin-G1 was detected in the midbrain and hindbrain regions by E12 (data not shown). Thereafter,netrin-G1 was expressed in many discrete regions of the CNS. The expression of netrin-G1 is most prominent in the thalamus. Thalamic neurons relay afferents to cerebral cortex from various regions of the nervous system, including the mammillary body, which also expresses netrin-G1. Conversely, neocortical neurons in layer V project axons to thalamic nuclei through corticothalamic pathways. It is thought that the latter projection is initially influenced by netrin-1, which is released from an intermediate target, ganglionic eminence (Métin et al., 1997;Richards et al., 1997). Netrin-G1 may influence this projection beyond the ganglionic eminence toward the thalamic nuclei as an attractive and/or target selective cue.

The expression of netrin-G1 reached highest levels at perinatal stages in most brain regions, implying its roles in late developmental stages of the CNS. However, a high level of expression persists exceptionally in the olfactory bulb mitral cells into adulthood. Olfactory receptor neurons start to project to mitral cells at approximately E14 and are able to regenerate for life. Furthermore, granule cells are continuously recruited from the subventricular zone, even in adults. Thus, the olfactory bulb needs to continuously renew structural connections between cells. Continuous expression of netrin-G1 may support the maintenance of circuitry in olfactory systems.

In the cerebellum, netrin-G1 expression is limited to the deep nuclei. The deep cerebellar nuclei receive three afferents, i.e., mossy fibers, climbing fibers, and Purkinje cell axons, and extend efferents to the red nucleus and other brain regions (Altman and Bayer, 1997). Interestingly, the inferior olive nuclei, origin of climbing fibers, and the red nuclei, target of deep cerebellar efferents, also express netrin-G1. Netrin-G1 may play a role in forming functional circuits for controlling motor activities. It is also possible that the deep cerebellar nuclei regulate migration or development of granule cells and Purkinje cells. Thus, the deep cerebellar nuclei may be one of the ideal sites to assess the functional importance of netrin-G1 in future work.

Concluding remarks

Although the UNC-6/netrin family has been highly conserved in evolution, the members of this family in mammals have likely diverged more than expected. Molecules, such as netrin-G1, that have diverged to a higher degree from the ancestral UNC-6 might have particularly important roles for highly organized cytoarchitectures unique to vertebrates. Mice carrying gain-of-function or loss-of-function mutations would help to test the hypothetical roles of netrin-G1 and would provide insight into candidate receptors.

Footnotes

This work was partly supported by a Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology project grant, Japan Science and Technology Corporation. We thank Dr. Marc Tessier-Lavigne for providing cDNAs ofUnc5h1, Unc5h2, DCC, andnetrin-1; Dr. Susan Ackerman for cDNA ofUnc5h3/rcm; Drs. Takao Hensch and Alcino Silva for reading this manuscript and helpful comments; Dr. Fujio Murakami for his valuable discussions; Sachihiro Suzuki for his advice on in situ hybridization; Reiko Ando for her excellent technical assistance; and all members of S.I.'s laboratory for their stimulating discussions and encouragement. T.N. and S.N. express special thanks to Dr. Koreaki Ito for his continuous encouragement.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Shigeyoshi Itohara, Laboratory for Behavioral Genetics, Brain Science Institute, RIKEN, 2-1 Hirosawa, Wako, Saitama 351-0198, Japan. E-mail:sitohara@brain.riken.go.jp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackerman SL, Kozak LP, Przyborski SA, Rund LA, Boyer BB, Knowles BB. The mouse rostral cerebellar malformation gene encodes an UNC-5-like protein. Nature. 1997;386:838–842. doi: 10.1038/386838a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman J, Bayer SA. Afferent and efferent connections of the cerebellar deep nuclei. In: Altman J, Bayer SA, editors. Development of the cerebellar system. CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 1997. pp. 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araujo M, Piedra ME, Herrera MT, Ros MA, Nieto MA. The expression and regulation of chick EphA7 suggests roles in limb patterning and innervation. Development. 1998;125:4195–4204. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.21.4195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck K, Hunter I, Engel J. Structure and function of laminin: anatomy of a multidomain glycoprotein. FASEB J. 1990;4:148–160. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.2.2404817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown D. The tyrosine kinase connection: how GPI-anchored proteins activate T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:349–354. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90052-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruckner K, Pasquale EB, Klein R. Tyrosine phosphorylation of transmembrane ligands for Eph receptors. Science. 1997;275:1640–1643. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan SS-Y, Zheng H, Su M-W, Wilk R, Killeen MT, Hedgecock EM, Culotti JG. UNC-40, a C. elegans homolog of DCC (Deleted in Colorectal Cancer), is required in motile cells responding to UNC-6 netrin cues. Cell. 1996;87:187–195. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chisholm A, Tessier-Lavigne M. Conservation and divergence of axon guidance mechanisms. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:603–615. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(99)00021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colamarino SA, Tessier-Lavigne M. The axonal chemoattractant netrin-1 is also a chemorepellent for trochlear motor axons. Cell. 1995;81:621–629. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conlon RA, Rossant J. Exogeneous retinoic acid rapidly induces anterior ectopic expression of murine Hox-2 genes in vivo. Development. 1992;116:357–368. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis S, Aldrich TH, Valenzuela DM, Wong VV, Furth ME, Squinto SP, Yancopoulos GD. The receptor for ciliary neurotrophic factor. Science. 1991;253:59–63. doi: 10.1126/science.1648265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davy A, Gale NW, Murray EW, Klinghoffer RA, Soriano P, Feuerstein C, Robbins SM. Compartmentalized signaling by GPI-anchored ephrin-A5 requires the Fyn tyrosine kinase to regulate cellular adhesion. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3125–3135. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.23.3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de la Torre JR, Höpker VH, Ming G-L, Poo M-M, Tessier-Lavigne M, Hemmati-Brivanlou A, Holt CE. Turning of retinal growth cones in a netrin-1 gradient mediated by the netrin receptor DCC. Neuron. 1997;19:1211–1224. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodd J, Schuchardt A. Axon guidance: a compelling case for repelling growth cones. Cell. 1995;81:471–474. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engvall E, Wewer UM. Domains of laminin. J Cell Biochem. 1996;61:493–501. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19960616)61:4%3C493::AID-JCB2%3E3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flanagan JG, Vanderhaeghen P. The ephrins and Eph receptors in neural development. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1998;21:309–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerber LD, Kodukula K, Udenfriend S. Phosphatidylinositol glycan (PI-G) anchored membrane proteins. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12168–12173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris R, Sabatelli LM, Seeger MA. Guidance cues at the Drosophila CNS midline: identification and characterization of two Drosophila netrin/UNC-6 homologs. Neuron. 1996;17:217–228. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedgecock EM, Culotti JG, Hall DH. The unc-5, unc-6, and unc-40 genes guide circumferential migrations of pioneer axons and mesodermal cells on the epidermis in C. elegans. Neuron. 1990;2:61–85. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90444-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holder N, Klein R. Eph receptors and ephrins: effectors of morphogenesis. Development. 1999;126:2033–2044. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.10.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong K, Hinck L, Nishiyama M, Poo M-M, Tessier-Lavigne M, Stein E. A ligand-gated association between cytoplasmic domains of UNC5 and DCC family receptors converts netrin-induced growth cone attraction to repulsion. Cell. 1999;97:927–941. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80804-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hutter H, Vogel BE, Plenefisch JD, Norris CR, Proenca RB, Spieth J, Guo C, Mastwal S, Zhu X, Scheel J, Hedgecock EM. Conservation and novelty in the evolution of cell adhesion and extracellular matrix genes. Science. 2000;287:989–994. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishii N, Wadsworth WG, Stern BD, Culotti JG, Hedgecock EM. UNC-6, a laminin-related protein, guides cell and pioneer axon migrations in C. elegans. Neuron. 1992;9:873–881. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90240-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs KA, Collins-Racie LA, Colbert M, Duckett M, Golden-Fleet M, Kelleher K, Kriz R, LaVallie ER, Merberg D, Spaulding V, Stover J, Williamson MJ, McCoy JM. A genetic selection for isolating cDNAs encoding secreted proteins. Gene. 1997;198:289–296. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00330-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keino-Masu K, Masu M, Hinck L, Leonardo ED, Chan S, Culotti JG, Tessier-Lavigne M. Deleted in Colorectal Cancer (DCC) encodes a netrin receptor. Cell. 1996;87:175–185. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kennedy TE, Serafini T, de la Torre JR, Tessier-Lavigne M. Netrins are diffusible chemotropic factors for commissural axons in the embryonic spinal cord. Cell. 1994;78:425–435. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kolodziej PA, Timpe LC, Mitchell KJ, Fried SR, Goodman CS, Jan LY, Jan YN. frazzled encodes a Drosophila member of the DCC immunoglobulin subfamily and is required for CNS and motor axon guidance. Cell. 1996;87:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leonardo ED, Hinck L, Masu M, Keino-Masu K, Ackerman SL, Tessier-Lavigne M. Vertebrate homologues of C. elegans UNC-5 are candidate netrin receptors. Nature. 1997a;386:833–838. doi: 10.1038/386833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonardo ED, Hinck L, Masu M, Keino-Masu K, Fazeli A, Stoeckli ET, Ackerman SL, Weinberg RA, Tessier-Lavigne M. Guidance of developing axons by netrin-1 and its receptors. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1997b;62:467–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lierheimer R, Kunz B, Vogt L, Savoca R, Brodbeck U, Sonderegger P. The neuronal cell-adhesion molecule axonin-1 is specifically released by an endogenous glycosylphosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase. Eur J Biochem. 1997;243:502–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.0502a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livesey FJ, Hunt SP. Netrin and netrin receptor expression in the embryonic mammalian nervous system suggests roles in retinal, striatal, nigral, and cerebellar development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1997;8:417–429. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Métin C, Deléglise D, Serafini T, Kennedy TE, Tessier-Lavigne M. A role for netrin-1 in the guidance of cortical efferents. Development. 1997;124:5063–5074. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.24.5063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitchell KJ, Doyle JL, Serafini T, Kennedy TE, Tessier-Lavigne M, Goodman CS, Dickson BJ. Genetic analysis of netrin genes in Drosophila: netrins guide CNS commissural axons and peripheral motor axons. Neuron. 1996;17:203–215. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagase T, Ishikawa K-I, Suyama M, Kikuno R, Hirosawa M, Miyajima N, Tanaka A, Nomura N, Ohara O. Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. XIII. The complete sequences of 100 new cDNA clones from brain which code for large proteins in vitro. DNA Res. 1999;6:63–70. doi: 10.1093/dnares/6.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Püschel AW. Divergent properties of mouse netrins. Mech Dev. 1999;83:65–75. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richards LJ, Koester SE, Tuttle R, O'Leary DDM. Directed growth of early cortical axons is influenced by a chemoattractant released from an intermediate target. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2445–2458. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02445.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sasaki M, Kleinman HK, Huber H, Deutzmann R, Yamada Y. Laminin, a multidomain protein. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:16536–16544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serafini T, Kennedy TE, Galko MJ, Mirzayan C, Jessell TM, Tessier-Lavigne M. The netrins define a family of axon outgrowth-promoting proteins homologous to C. elegans UNC-6. Cell. 1994;78:409–424. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90420-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shirasaki R, Tamada A, Katsumata R, Murakami F. Guidance of cerebellofugal axons in the rat embryo: directed growth toward the floor plate and subsequent elongation along the longitudinal axis. Neuron. 1995;14:961–972. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shirasaki R, Mirzayan C, Tessier-Lavigne M, Murakami F. Guidance of circumferentially growing axons by netrin-dependent and -independent floor plate chemotropism in the vertebrate brain. Neuron. 1996;17:1079–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki SC, Inoue T, Kimura Y, Tanaka T, Takeichi M. Neuronal circuits are subdivided by differential expression of type-II classic cadherins in postnatal mouse brains. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1997;9:433–447. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tashiro K, Tada H, Heilker R, Shirozu M, Nakano T, Honjo T. Signal sequence trap: a cloning strategy for secreted proteins and type I membrane proteins. Science. 1993;261:600–603. doi: 10.1126/science.8342023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tessier-Lavigne M, Goodman CS. The molecular biology of axon guidance. Science. 1996;274:1123–1133. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Timpl R, Brown JC. The laminins. Matrix Biol. 1994;14:275–281. doi: 10.1016/0945-053x(94)90192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Raay TJ, Foskett SM, Connors TD, Klinger KW, Landes GM, Burn TC. The NTN2L gene encoding a novel human netrin maps to the autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease region on chromosome 16p13.3. Genomics. 1997;41:279–282. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Heijne G. A new method for predicting signal sequence cleavage sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:4683–4690. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.11.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wadsworth WG, Bhatt H, Hedgecock EM. Neuroglia and pioneer neurons express UNC-6 to provide global and local netrin cues for guiding migrations in C. elegans. Neuron. 1996;16:35–46. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang H, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Tessier-Lavigne M. Netrin-3, a mouse homolog of human NTN2L, is highly expressed in sensory ganglia and shows differential binding to netrin receptors. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4938–4947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-04938.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilkinson DG, Bailes JA, McMahon AP. Expression of the proto-oncogene int-1 is restricted to specific neural cells in the developing mouse embryo. Cell. 1987;50:79–88. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90664-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yabe D, Nakamura T, Kanazawa N, Tashiro K, Honjo T. Calumenin, a Ca2+-binding protein retained in the endoplasmic reticulum with a novel carboxy-terminal sequence, HDEF. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18232–18239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]