Abstract

The CaMKIIα mRNA extends into distal hippocampal dendrites, and the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) is sufficient to mediate this localization. We labeled the 3′UTR of the CaMKIIα mRNA in hippocampal cultures by using a green fluorescent protein (GFP)/MS2 bacteriophage tagging system. The CaMKIIα 3′UTR formed discrete granules throughout the dendrites of transfected cells. The identity of the fluorescent granules was verified by in situ hybridization. Over 30 min time periods these granules redistributed without a net increase in granule number; with depolarization there is a tendency toward increased numbers of granules in the dendrites. These observations suggest that finer time resolution of granule motility might reveal changes in the motility characteristics of granules after depolarization. So that motile granules could be tracked, shorter periods of observation were required. The movements of motile granules can be categorized as oscillatory, unidirectional anterograde, or unidirectional retrograde. Colocalization of CaMKIIα 3′UTR granules and synapses suggested that oscillatory movements allowed the granules to sample several local synapses. Neuronal depolarization increased the number of granules in the anterograde motile pool. Based on the time frame over which the granule number increased, the translocation of granules may serve to prepare the dendrite for mounting an adequate local translation response to future stimuli. Although the resident pool of granules can respond to signals that induce local translation, the number of granules in a dendrite might reflect its activation history.

Keywords: RNA localization, RNA translocation, CaMKIIα, 3′UTR, RNA granules, synaptic plasticity

Local protein synthesis within dendrites is an attractive mechanism potentially capable of explaining many phenomena related to neuronal plasticity. In dendrites, polyribosomes are positioned beneath the postsynaptic density and therefore are situated ideally to perform protein synthesis in response to neuronal activity (Steward and Levy, 1982; Steward and Fass, 1983). Most mRNAs that reside in dendrites appear to be located there constitutively (Miyashiro et al., 1994; Crino and Eberwine, 1996;Steward, 1997; Kiebler and DesGroseillers, 2000), whereas others, such as the Arc mRNA (Link et al., 1995; Lyford et al., 1995;Steward et al., 1998; Guzowski et al., 1999), appear in dendrites only after neuronal stimulation. In both cases the mechanisms that underlie RNA motility, the signals that activate translocation and target mRNAs to specific sites, and the nature of mRNA docking are understood only poorly.

mRNAs are present in dendrites along microtubules (Bassell et al., 1994) in the form of granules that appear to be the active transport unit and contain translational machinery (Ainger et al., 1993;Ferrandon et al., 1994; Wang and Hazelrigg, 1994; Knowles et al., 1996). Direct visualization in living cells demonstrates that granules translocate along microtubules within dendrites (Knowles et al., 1996) and oligodendrocytes (Ainger et al., 1993) and duringDrosophila oogenesis (Theurkauf and Hazelrigg, 1998) or along actin filaments in the yeast bud (Bertrand et al., 1998). A few proteins within these complexes, such as Staufen (Kiebler et al., 1999), hnRNP A2 (Hoek et al., 1998), and the zipcode-binding protein (Ross et al., 1997; Deshler et al., 1998), have been identified and represent candidate regulators and effectors of RNA trafficking

Recently, green fluorescent protein (GFP) was linked to the ASH1 mRNA in yeast, and translocation into the yeast bud was observed directly (Bertrand et al., 1998; Beach et al., 1999). We have applied a similar system to visualize the motility of the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase IIα (CaMKIIα) in primary hippocampal cultures. The mRNA for CaMKIIα is localized dendritically (Steward, 1997), and its 3′UTR can mediate this localization (Mayford et al., 1996). The function of CaMKIIα in the induction and maintenance of long-term potentiation (Malenka and Nicoll, 1999) fits well with many of the expected properties of a dendritic mRNA. After induction of LTP the levels of CaMKIIα mRNA are increased in both the cell body and the dendrites (Thomas et al., 1994; Roberts et al., 1998), and strong tetanic stimulation of the Schaffer collateral pathway leads to increased levels of CaMKIIα in dendrites earlier than can be accounted for by transport from the cell bodies (Ouyang et al., 1999). Thus the signals that activate CaMKII and initiate local CaMKIIα translation may localize CaMKIIα mRNA-containing granules at activated synapses also. Our dynamic observations demonstrate that labeled CaMKIIα 3′UTR can assume the motility characteristics of RNA granules and that neuronal depolarization increases labeled CaMKIIα 3′UTR granules in dendrites by driving oscillatory granules into an anterograde motile pool.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction. To make the RNA expression vector RSV-lacZ-MS2bs-CaMKIIα3′UTR, we amplified the 3′UTR of CaMKIIα from pBluescript containing the mouse CaMKIIα coding sequence and 3′UTR (a gift from Dr. Mark Mayford, University of California San Diego School of Medicine) with a 5′ primer containing two copies of the MS2-binding site and aBglII site directly 3′ of the MS2-binding site sequence, 5′-gcgatccaacatgaggatcacccatgtcagctggtcgactctagaaaacatgaggatcacccatg-tagatctggggcgccctccgtc-3′, and a 3′ primer complementary to the 3′ end of CaMKIIα, 5′-ggattctttaaatttgtactatttat-3′. The resulting PCR fragment was ligated into the PCRblunt vector (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). The resultant vector was cleaved with BamHI and ligated intoBamHI-cleaved RSV-β-gal vector (a gift from Dr. Robert Singer, Albert Einstein College of Medicine). To facilitate subsequent subcloning, we deleted the 3′ BamHI site by amplifying the CaMKIIα 3′UTR with the same 5′ primer and a 3′ primer replacing the 3′ BamHI site with a NotI site, 5′-ataagaatgcggcccgctttaaatttgtagctatttattcc-3′. The resulting PCR product was cleaved with BglII and NotI and ligated into BglII/NotI-cleaved RSV-β-gal-MS2bs- CaMKIIα3′UTR. To generate plasmids with four copies of the MS2-binding site, we cleaved the RSV-β-gal-MS2bs-CaMKIIα3′UTR vector with BamHI andNotI, generating a 3400 bp fragment containing two MS2-binding sites and the 3′UTR. This fragment was ligated to the RSV-β-gal-MS2bs-CaMKIIα3′UTR vector cleaved with BglII and NotI; this process was repeated to generate plasmids with eight copies of the MS2-binding site.

The GFP-MS2-nls vector was generated from a pEGFP–C1–MS2 coat protein fusion (a gift from Dr. Jamie Williamson). The W83R mutation, which makes the protein capsid assembly-deficient, was generated by using the Stratagene Quick Change kit (La Jolla, CA). A nuclear localization sequence was added to the mutant coat protein/GFP fusion by amplifying the MS2 protein sequence with a 3′ primer containing three copies of a nuclear localization consensus sequence.

Hippocampal cell culture and transient transfection.Pregnant embryonic day 18 (E18) Sprague Dawley rats were killed by inhalation of CO2, and the embryos were removed immediately by cesarean section. Hippocampi were removed and digested in 0.25% trypsin in HEPES-buffered HBSS without calcium or magnesium at 37°C for 15 min. The hippocampi were washed three times with HBSS and manually dissociated with a fire-bored Pasteur pipette. Cells were plated at a concentration of 25,000/cm2 on poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips in plating medium containing DMEM and 10% fetal bovine serum. After incubation overnight the medium was changed to Neurobasal medium containing B27 supplement and 0.5 mm glutamine.

Primary hippocampal neurons were transiently transfected by using a modified Ca2+-phosphate precipitation method. The media of cultures varying from 7 to 11 d in vitro (DIV) was changed to DMEM containing 1 mm sodium kynurenate and 10 mm MgCl2(DMEM/Ky-Mg2+) and was incubated for 30 min at 37°C/5% CO2. During this incubation Ca2+-phosphate/DNA solution was prepared, 60 μl containing 4 μg of DNA (3 μg of the RNA vector; 1 μg of GFP vector if two plasmids were transfected); 250 mm CaCl2 was added drop-wise to 60 μl of 2× HBS [containing (in mm) 274 NaCl, 10 KCl, 1.4 Na2HPO4, 5d-glucose, and 42 HEPES, pH 7.07]. Precipitate was allowed to form for 20 min, and 60 μl was added drop-wise to 25 mm coverslips or 20 μl was added drop-wise to 12 mm coverslips. Cells were incubated at 37°C/5% CO2 for from 30 to 90 min, washed once with DMEM/Ky-Mg2+, once with Neurobasal containing B27 and glutamine, and returned to conditioned Neurobasal medium. Coverslips were used for microscopy in 24–48 hr.

Riboprobe preparation. To determine the localization pattern of transfected mRNA, we performed in situ hybridization against the lacZ reporter RNA. Riboprobes were transcribed from pBluescript containing the lacZ coding sequence. The plasmid was linearized and transcribed in the presence of digoxygenin (DIG)-UTP (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) with either T7 RNA polymerase or T3 RNA polymerase to generate sense or antisense DIG-labeled riboprobe, respectively. To purify probes, we added 2.5 μl of 4m LiCl and ethanol-precipitated the RNA. Probes were resuspended in 50 μl of distilled deionized water and hydrolyzed by the addition of 50 μl of carbonate buffer (40 mm NaHCO3 and 60 mmNa2CO3); incubation occurred at 60°C for 5 min. The solution was neutralized by the addition of 100 μl of 0.2 m sodium acetate/1% glacial acetic acid; 5 μl of 10 mg/ml glycogen was added as carrier, and probes were ethanol-precipitated and resuspended in 50 μl of distilled deionized water. Probes were checked for DIG incorporation by dot blot.

Hybridization and immunocytochemistry. Cells were washed three times with 1× PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/5 mm MgCl2/PBS for 15 min at room temperature, washed three more times in PBS, and incubated in 1× SSC for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were permeabilized by incubation in 1% Triton X-100/1× SSC for 30 min at room temperature, washed two times with PBS for 5 min at room temperature, and incubated in 0.1m glycine and 0.2 m Tris-Cl, pH 8, for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were prehybridized in hybridization mix (50% formamide, 2× SSC, 1% Denhardt's solution, 20% dextran sulfate, 0.5 mg/ml of tRNA, and 0.25 mg/ml of sonicated salmon sperm DNA) for 1 hr at 55°C; then the coverslips were placed cell-side down on Parafilm containing 20 μl of hybridization mix plus 1 μl of probe and hybridized in a humid chamber overnight at 55°C. After hybridization the coverslips were washed three times with 50% formamide/1× SSC for 20 min at 55°C, two times with 1× SSC for 20 min at room temperature, and two times with Tris-buffered saline, pH 8. Cells were blocked with blocking reagent from the Boehringer Mannheim DIG detection kit for 30 min at room temperature.

Probes were detected with affinity-purified rhodamine-conjugated anti-digoxygenin (Boehringer Mannheim). The anti-DIG antibody was diluted 1:50 in blocking solution; at the same time the cells were incubated with a 1:300 dilution of monoclonal anti-β-gal (Promega, Madison, WI). The cells were incubated at room temperature for 1 hr and washed in 3× PBS for 10 min. β-Gal staining was detected with Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at a 1:500 dilution in 1% neural goat serum, 0.1% BSA, and PBS for 15 min at room temperature, washed three times in PBS for 10 min, and mounted on microscope slides with Antifade mounting medium. For colocalization experiments elongation factor 1α (EF1α) was detected with mouse anti-EF1α (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY). Coverslips were washed three times with PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS, washed three more times with PBS, and blocked for 30 min at room temperature with 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% goat serum, and PBS. Cells were incubated in anti-EF1α antibody diluted to 10 μg/ml in blocking solution for 1 hr at room temperature and washed three times with PBS. Anti-EF1α was detected with Alexa 594 goat anti-mouse (Molecular Probes) secondary antibody. Synaptophysin staining was detected with monoclonal anti-synaptophysin (Boehringer Mannheim) and Alexa 594 goat anti-mouse (Molecular Probes) secondary antibody.

Fluorescence video microscopy. High-resolution fluorescence video microscopy was performed on a Nikon microscope (Diaphot 300) equipped with both a 40× oil immersion (1.0 numerical aperture) and a 100× oil immersion lens (1.4 numerical aperture). A specific GFP filter set (Chroma Technology, Brattleboro, VT) was used for detecting the fluorescence from the EGFP fusion protein, and a rhodamine filter set was used for detecting anti-digoxygenin, anti-synaptophysin, and anti-EF1α. To monitor RNA granule motility, we transferred transfected cells to a closed chamber maintained at 37°C on a heated stage; the cells either were maintained in Neurobasal medium or were changed into physiology buffer [containing (in mm) 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 25 HEPES, pH 7.5, and 30 glucose] or physiology buffer with 10 mm KCl. Then fluorescence images were captured with a highly sensitive back-thinned cooled CCD camera (Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ) and processed with MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging, Media, PA). To minimize photobleaching and phototoxicity, especially for living cells, we used a computer-driven automatic shutter to achieve the minimum illumination. For time-lapse recordings 500–1000 msec exposures every 20 sec over a 5–10 min period were used to capture images. Some exposures were taken every 10 sec for a shorter time period or every 30 sec over a longer time period.

Image analysis. For in situ hybridization experiments MetaMorph software was used for all analyses. The length of a particular dendrite was measured by tracing the distance from the cell body to the end of the process highlighted by β-gal staining. The same region was overlaid onto the image containing the in situ hybridization staining and divided into 20-μm-long segments. Then the number of granules visualized in each segment was counted. To calculate the percentage of length of dendrite-containing RNA granules, we divided the distance to the most distal RNA granule by the total length of the dendrite and multiplied it by 100. Granule density of GFP-labeled RNA granules was calculated by counting the number of granules in dendrites ∼20 μm long and 1 μm wide. In all, 35 processes from 29 different control cells and 40 processes from 24 different treated cells were analyzed.

For colocalization experiments, images of the same region of a coverslip were taken by using either the GFP or rhodamine filter set, and a coordinate system was applied to the image by the MetaMorph software. To determine whether a particle labeled both by GFP and an antibody colocalized, we compared the coordinates of the particle in one image with those in the other; if the coordinates were the same, the particles were considered to show colocalization.

To calculate the total distance a granule traveled, we called the initial location of a granule “zero.” The distances traveled (in μm) in each 20 sec interval were summed with anterograde movements to the previous value, and the retrograde movements were subtracted. For histogram plots of distance from origin, the distance each granule translocated was taken as the distance from the granule starting point to the last position of the granule in a time-lapse series.

To measure rates, we measured the distance a particle traveled between two adjacent time-lapse images and divided it by the time between exposures. To calculate average rates and rate distributions for untreated cells, we compared 10 oscillatory granules with 48 velocities and 10 unidirectionally moving granules with 36 velocities. For KCl-treated cells, four oscillatory granules with 30 velocities and 15 unidirectionally moving granules with 73 velocities were compared. A granule was considered oscillatory if it reversed direction at least once.

RESULTS

The CaMKIIα 3′UTR is sufficient for RNA granule formation and transport

The CaMKIIα mRNA is localized constitutively in high abundance to the dendrites of hippocampal neurons (Burgin et al., 1990; Martone et al., 1996; Steward, 1997; Malenka and Nicoll, 1999), and the 3′UTR is sufficient to localize a reporter construct in the hippocampal neurons of a transgenic mouse (Mayford et al., 1996). Therefore, this mRNA is an excellent candidate for direct visualization of its transport. To accomplish this goal, we designed two constructs that would link GFP to a specific RNA. A construct (GFP–MS2–nls) was assembled that included enhanced GFP, an RNA-binding protein, and a nuclear localization signal under control of the CMV promotor (Fig.1a). The RNA-binding protein that was used was a capsid assembly-deficient MS2 coat protein, which normally forms the capsid of the MS2 bacteriophage. Although deficient in capsid assembly, it binds tightly and specifically to a small RNA hairpin. The second construct consisted of the 3248 bp mouse CaMKIIα 3′UTR fused to eight copies of the small RNA hairpin-binding element and the lacZ mRNA as a reporter under control of the RSV promotor.

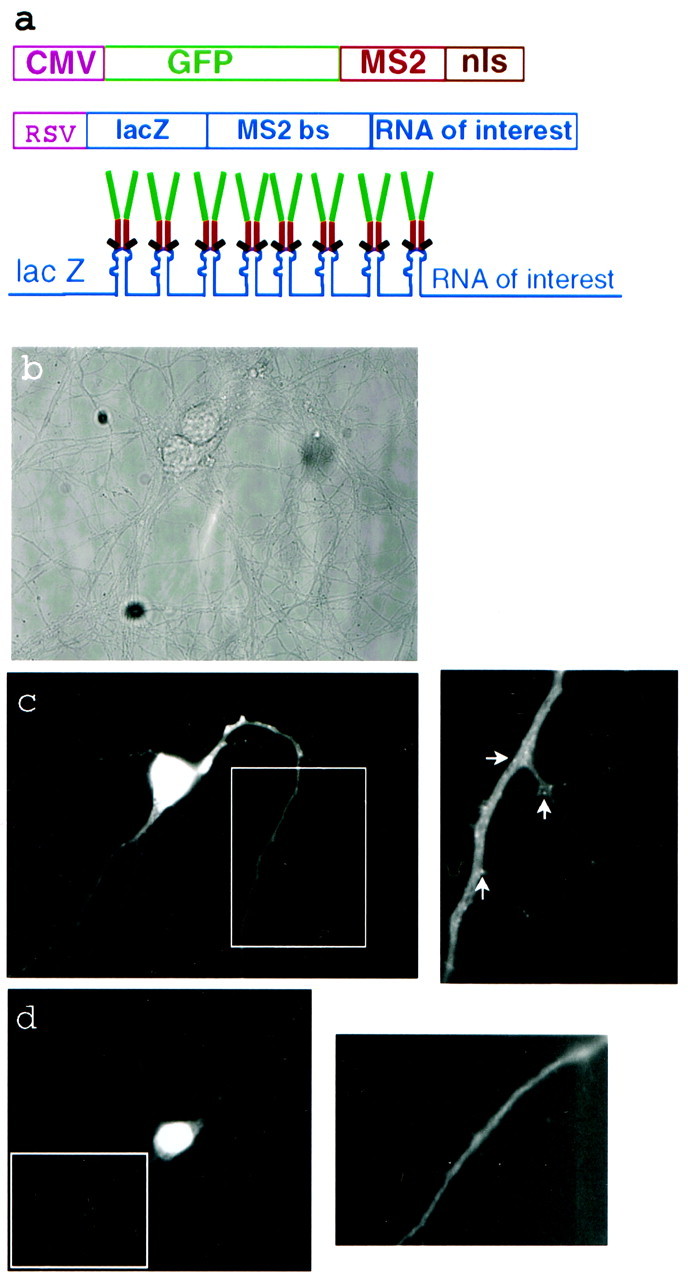

Fig. 1.

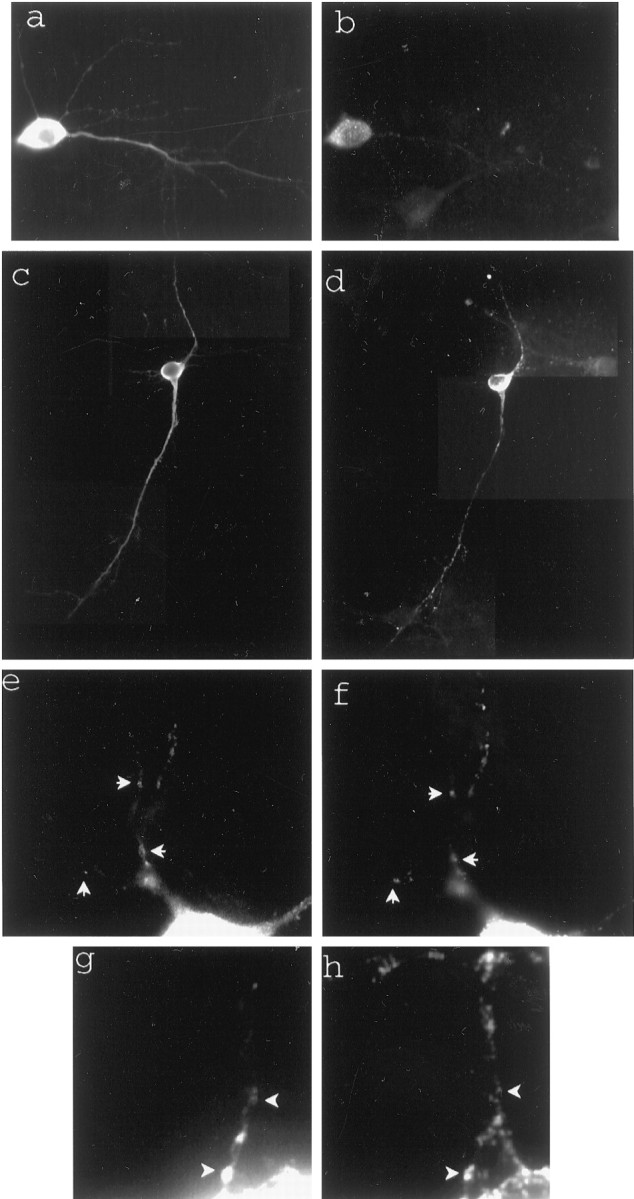

Dual constructs for GFP labeling of specific RNAs in living cells. a, The GFP fusion expression is driven by the strong CMV promotor. The MS2W82R capsid assembly-deficient RNA-binding protein is expressed as a C-terminal fusion with GFP and three copies of a consensus nuclear localization sequence. The RNA construct is expressed by the strong RSV promotor and generates a translationally competent RNA encoding the lacZ reporter gene, eight copies of the 18 bp MS2-binding site RNA hairpin, and the RNA of interest. After expression of both constructs the GFP fusion should bind as a dimer to each MS2-binding site, leading to an amplified GFP signal. b, Phase-contrast image of a transfected cell.c, A live cell expressing both constructs with the CaMKIIα 3′UTR mRNA as the RNA of interest. A higher-magnification image of the boxed region shows many small GFP-labeled granules in the dendrites. Arrows denote RNA-containing granules. d, A live cell expressing the GFP construct alone shows diffuse staining. A higher-magnification image of theboxed region also shows smooth staining.

To image the RNA fluorescently, we cotransfected the two plasmids encoding the GFP construct and the CaMKIIα 3′UTR RNA construct into rat primary hippocampal cultures. When the constructs are expressed, the GFP–MS2–nls fusion protein should dimerize and bind to an RNA hairpin labeling the RNA of interest (Fig. 1a). The presence of eight hairpin-binding elements should increase the number of bound GFP molecules and increase the signal-to-noise. The majority of the unbound GFP fusion protein remains in the nucleus because of the nuclear localization sequence. When the RNA construct was cotransfected with the GFP–MS2–nls construct into hippocampal neurons, small bright granules were seen in the dendrites, but not in the axons of GFP-labeled neurons (Fig. 1c). Individual granules could not be distinguished from background fluorescence in the cell body because of the high nuclear GFP signal. When the GFP–MS2–nls construct was transfected into hippocampal cultures alone, diffuse staining was seen and no granules were detected in the processes (Fig.1d).

Dendritically localized RNA-containing granules colocalized with the GFP-labeled granules (Fig.2e,f). The number of granules detected by the GFP signal from the GFP-labeled CaMKIIα 3′UTR RNA-containing granules was only slightly lower than the number of RNA granules measured by in situ hybridization for lacZ mRNA. This small difference is most likely attributable to the higher sensitivity of in situ hybridization. RNA-containing granules in neurons generally are associated with ribosomes and translational machinery. To determine whether the GFP-labeled granules also were associated with the translational apparatus, we stained the cultures with an antibody against the translation elongation factor EF1α. The immunostaining for EF1α colocalized with the GFP-labeled RNA-containing granules (Fig. 2g,h). RNA translation may be important for the regulation of RNA transport. To show that the transfected CaMKIIα 3′UTR could be translationally competent in the presence of a coding sequence, we used the lacZ element included in the construct for the detection of β-galactosidase. The cultures stained intensely with an antibody against β-galactosidase in a diffuse (Fig.2a,c), rather than a granular, pattern because β-galactosidase tends to diffuse throughout neuronal processes. These findings suggest that the CaMKIIα 3′UTR can induce translationally competent granules.

Fig. 2.

The CaMKIIα 3′UTR is necessary and sufficient to localize RNA granules to distal dendrites. GFP-labeled granules contain CaMKIIα 3′UTR RNA and components of translation. a, b, A cell transfected with the lacZ-MS2-binding site empty vector.a, β-Gal staining shows that the RNA is translationally competent and that β-gal diffuses throughout the processes. b,In situ hybridization with probes for lacZ labels punctate RNA granules only in the cell body.c, d, A cell transfected with the lacZ-MS2-binding site–CaMKIIα 3′UTR fusion construct. Figures are a composite from three separate images of the same cell. c, β-Gal staining is seen throughout the processes. d, In situ hybridization labels punctate RNA granules in the cell body and throughout the dendrites. e, f, CaMKIIα 3′UTR containing GFP-labeled granules in dendrites colocalize with lacZ-CaMKIIα 3′UTR RNA detected by in situhybridization. Arrows show colocalized granules. Images were analyzed with MetaMorph software, coordinates were mapped onto images that were taken by using GFP or a rhodamine filter set, and granules were considered to colocalize when the coordinates of two objects were the same. e, GFP-labeled RNA granules.f, lacZ-CaMKIIα 3′UTR RNA detected by in situ hybridization. g, h, GFP-labeled granules colocalize with granules stained with anti-EF1α.Arrows show colocalized staining. g, GFP-labeled granules. h, EF1α staining.

To ensure that the CaMKIIα 3′UTR was sufficient and necessary to direct localization of the reporter RNA to distal dendrites, we performed fluorescence in situ hybridization against the lacZ reporter RNA in cells that had been transfected with constructs either containing or lacking the CaMKIIα 3′UTR. LacZ was chosen as a reporter to avoid background from endogenous CaMKIIα. β-Gal immunostaining was used to determine the total length of processes, because β-gal diffuses throughout the neuron. RNA containing lacZ mRNA and the MS2-binding sites was highly expressed in the cell body and most proximal portion of the dendrite. RNA containing the CaMKIIα 3′UTR was detected at an average distance of 60 ± 23 μm from the cell body and in some cases as far as 120 μm from the cell body (Fig. 2c,d, Tables1,2). RNA containing only the lacZ mRNA and MS2-binding sites was detected at an average distance of 23 ± 13 μm from the cell body (Fig. 2a,b).

Table 1.

The effect of the CaMKIIα 3′UTR on the localization of RNA-containing granules

| Construct | Number of dendrites analyzed | Farthest distance granules found from cell body | Number of dendrites used in β-gal comparison | Dendrite length-containing granules (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS2 binding site empty vector | 101 | 26 ± 18 μm | 13 | 30 ± 23 |

| MS2 binding site + 3′UTR | 93 | 60 ± 33 μm | 48 | 88 ± 23 |

Table 2.

The effect of the CaMKIIα 3′UTR on RNA granule density in dendrites

| Construct | Number of granules in length of dendrite (number of dendrites containing granules) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–20 μm | 20–40 μm | 40–60 μm | 60–80 μm | 80–100 μm | 100–120 μm | |

| MS2 binding site | 7 ± 6 (101) | 6 ± 3 (32) | 7 ± 4 (8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Empty vector | ||||||

| MS2 binding site | 12 ± 6 (93) | 10 ± 7 (81) | 9 ± 5 (49) | 10 ± 8 (25) | 9 ± 5 (9) | 10 ± 11 (5) |

| 3′UTR | ||||||

Effect of KCl depolarization on granule density

Granule density was assessed both by in situhybridization and by GFP granule counts, both of which gave similar results. The average granule density measured by in situhybridization was 10 ± 6 granules per 20 μm length of dendrite, whereas the average granule density of GFP-labeled granules was 8 ± 3. Proximal dendrites tend to be thicker and have larger volumes; therefore, this portion of the dendrite did have a greater granule density. In these dendrites the granule density tended to decrease as the dendrite tapered. However, when granule density in all of the processes was averaged, granule density was fairly uniform throughout the length of the dendrite (Table 2). The reason for this effect was the large number of short thin processes (≤20 μm) with a low granule density that masked the higher densities in the thicker proximal segments of longer processes. This granule density was higher than that observed when the total cellular RNA was labeled with the RNA-binding dye SYTO 14 (Knowles et al., 1996); however, the RNA construct monitored in our assay was overexpressed, and the cultures that were used were older and had more complex dendritic arbors than those used in the SYTO 14 experiments. Both methodologies—SYTO 14 and GFP—revealed increased numbers of granules at dendritic branch points (Fig. 3a).

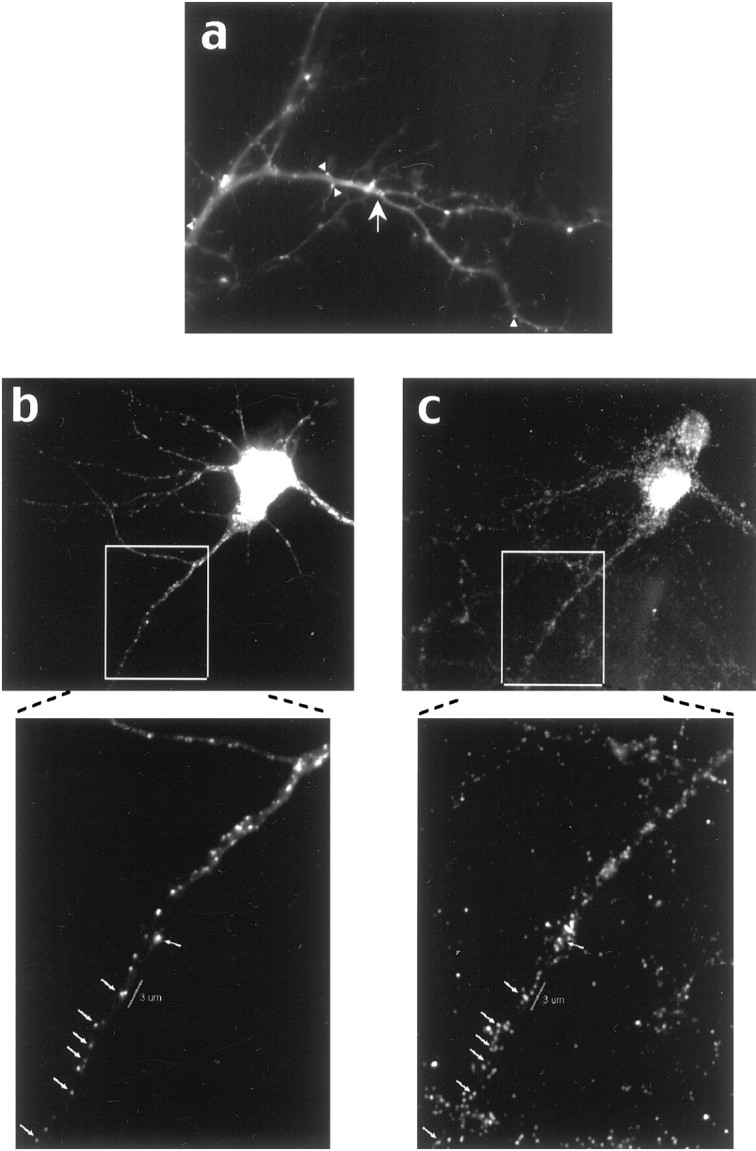

Fig. 3.

Proximity of GFP-labeled CaMKIIα 3′UTR RNA granules to synapses. a, GFP-labeled CaMKIIα 3′UTR mRNA-containing granules are localized at high density in junctions (arrows) and often are seen at the surface of dendrites and at the base of spines (arrowheads). b, c, Some RNA-containing granules colocalize with synaptophysin antibody. GFP-labeled RNA granules from a KCl-treated cell are shown in b; the synaptophysin-labeled cell is shown in c. The boxed regions are shown at higher magnification below, and arrowsshow colocalized granules. A region of dendrite 3 μm long is labeled with the white bar and shows a GFP-labeled granule near five synapses labeled with synaptophysin.

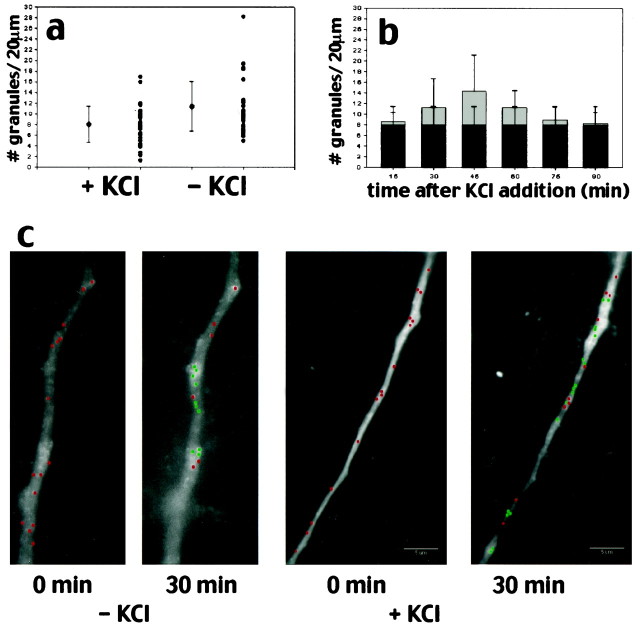

In cells monitored over a 30 min period the position of many of the granules changed, but there was no increase in their density (see Fig.5c). In cells monitored over a 30 min period after KCl depolarization, there was both a change in the distribution of granules and an increase in the total number of granules in the area of dendrite that was imaged (see Fig. 5c); however, this difference did not reach statistical significance. Given the large number of granules present in the control cells and the variability of granule density from cell to cell, a small increase might be masked. These observations prompted a more detailed analysis of granule motility with finer time resolution.

Fig. 5.

Effects of KCl on RNA granule density.a, KCl depolarization only slightly increases the granule density in dendrites. The average granule density was calculated from 35 processes from 29 different control cells and 40 processes from 24 different KCl-treated cells. b, KCl depolarization increases granule density slightly over time, but this difference does not reach statistical significance. Graybars represent the average granule density for KCl-treated cells; black bars show the granule density for control cells. c, Time-lapse images looking at an individual process over long time periods show changes in granule distribution. Under basal conditions the images taken at 0 min and after 30 min show a redistribution of granules but no increase in granule number, whereas cells treated with KCl show both a redistribution of granules and an increase in the number of granules present. Red dots represent stationary granules that have not changed position in the 30 min recording interval, whereasgreen dots represent new granules that have entered the region of dendrite being imaged or granules that have changed position in the dendrite during the 30 min recording interval. Granules were assigned on the basis of having a well defined circular shape and a pixel intensity above background levels in the process.

RNA granules show two types of movement: Oscillatory or unidirectional

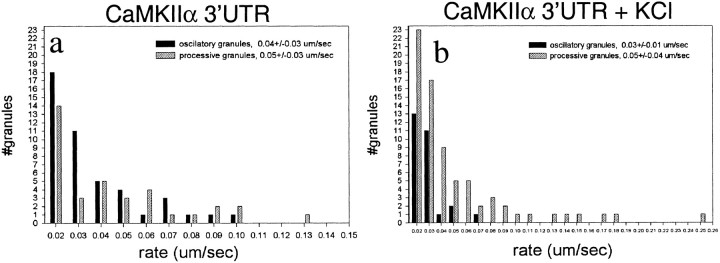

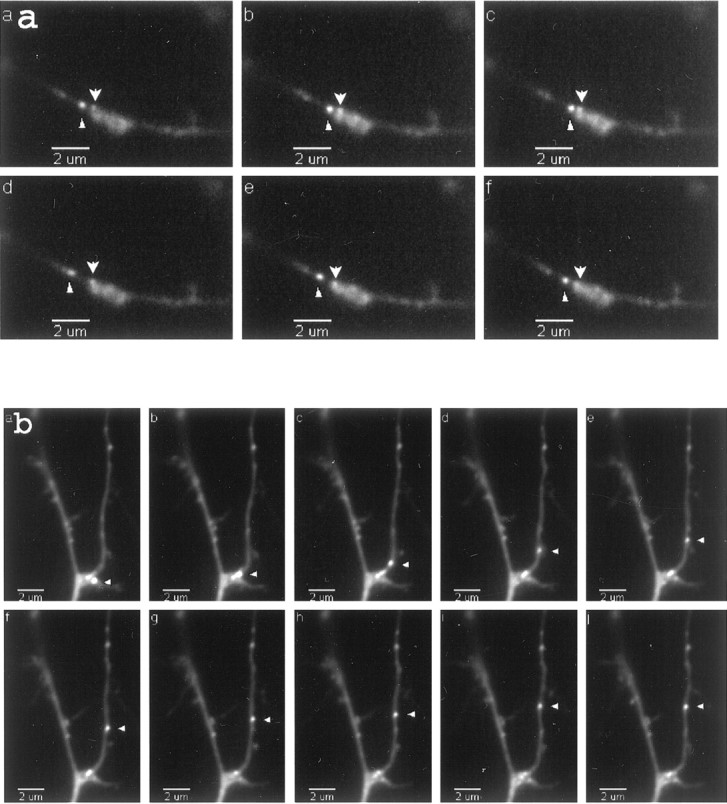

To monitor RNA granule motility, we transferred transfected cells to a chamber maintained at 37°C on a heated stage, and time-lapse images were taken of GFP-labeled neurons. Images generally were recorded every 20 sec over a 5–10 min time period; occasional exposures were taken every 10 or every 30 sec. Within this time interval the majority of granules was stationary during the imaging period; ∼2–4% of the granules were motile. Motile granules displayed two types of movement: oscillatory or unidirectional. Oscillatory granules were bidirectional over short distances, often traversing the same region of a dendrite multiple times. The distance traveled was ∼1 μm but occasionally was as large as 4 μm (Fig.4a). Unidirectionally moving granules traversed larger distances (2–8 μm) and moved consistently in either the anterograde or retrograde direction. Of the 23 motile granules that were analyzed, 52% were oscillatory, 22% were anterograde unidirectional, and 26% were retrograde unidirectional (see Fig. 7a). The movement of both oscillatory and unidirectionally moving granules was discontinuous; often granules would stop for one or two images and then resume movement. This characteristic of the motility led to the appearance of variable translocation rates, especially for oscillatory granules. Rates were measured by measuring the distance a particular granule moved in two consecutive frames of a time-lapse series and dividing by the time interval of 20 sec. Hidden stops may occur during the time-lapse recording. Therefore, the rates measured in this manner are only the lower limit for translocation rates and show a broad distribution (Fig. 6a). The average rate for oscillatory granules was 0.04 ± 0.03 μm/sec (which in general stop more frequently) and for unidirectionally moving granules was 0.05 ± 0.03 μm/sec. The maximum rate was 0.1 μm/sec for oscillatory and 0.2 μm/sec for unidirectionally moving granules.

Fig. 4.

CaMKIIα 3′UTR RNA granules show both oscillatory and unidirectional motility properties.a, Time-lapse images of an oscillatory granule. Frames are sequential images taken every 20 sec. Thearrowhead labels an oscillatory granule, whereas anarrow labels a stationary granule. b, Time-lapse of an anterograde-moving granule (arrowhead). Total distance translocated was 5.85 μm. Average velocity over 160 sec was 0.04 ± 0.01 μm/sec. The granule was docked originally at a junction, but after depolarization it moved in an anterograde direction. QuickTime movies are available for these images.

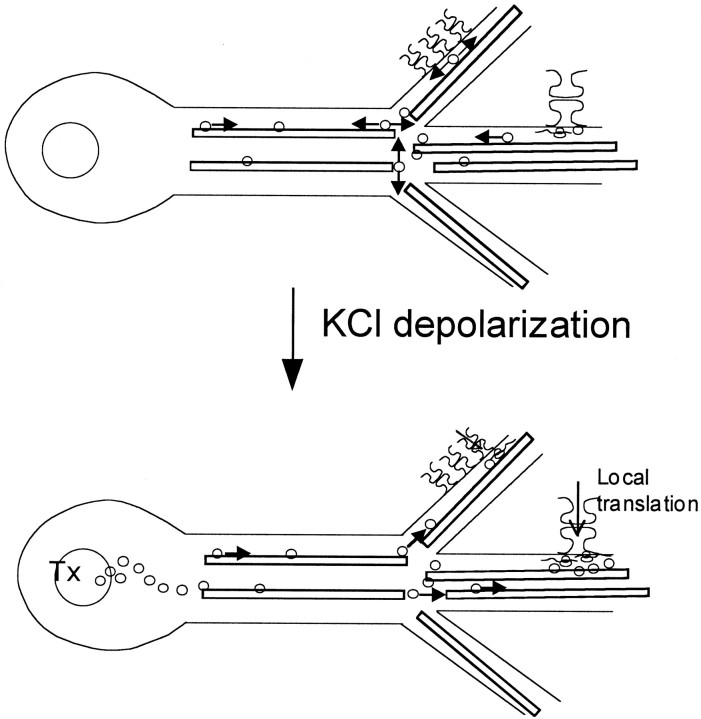

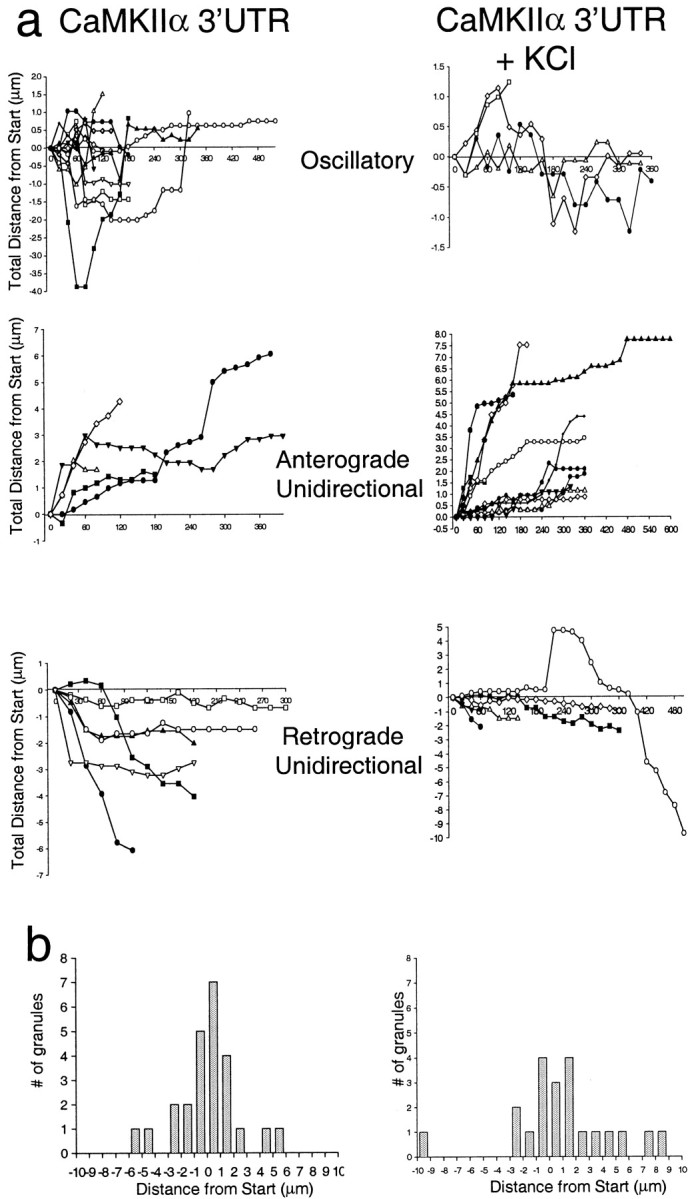

Fig. 7.

KCl depolarization shifts the motility characteristics of granules from oscillatory to anterograde unidirectional. a, Motile granules fall into three directional categories: oscillatory, anterograde, and retrograde. The plots show the distance each granule traveled during a time-lapse recording at 20 sec intervals. Movements in the anterograde direction are scored as positive, and movements in the retrograde direction are scored as negative. Plots are shown for both control cells and cells treated with 10 mm KCl. The addition of KCl shifts the population of granules from oscillatory to anterograde.b, The distance traveled by control granules displays a gaussian histogram, whereas the histogram of the distance traveled by granules in KCl-depolarized cells is shifted toward anterograde movement.

Fig. 6.

Effect of KCl depolarization on motility rates.a, The distribution of rates for CaMKIIα 3′UTR RNA-containing granules under basal conditions. Oscillatory granule rates are shown in black; unidirectional granule rates are shown in gray. Rates were calculated by measuring the change in position of a granule between two consecutive time-lapse images and dividing this distance by the time between images. b, The effect of KCl depolarization on the distribution of motility rates for CaMKIIα 3′UTR RNA-containing granules. After depolarization with KCl more granules moved unidirectionally, and more granules exhibited rates higher than 0.1 μm/sec.

Under basal conditions the distribution of granule displacements did not indicate any tendency for net movement either toward or away from the cell body. A histogram plot of the total distance traveled by 23 granules has a normal gaussian distribution (Fig.7b). Most granules do not move a significant distance from their starting points, and those that do are divided equally between retrograde and anterograde movements consistent with a steady-state RNA population.

We questioned whether oscillatory movements could center on synapses. First, to determine whether the granules were located in proximity to synapses, we fixed and stained GFP/CaMKIIα 3′UTR-labeled cells with anti-synaptophysin (see Fig. 3b,c). Although not all granules colocalized with synaptophysin antibody, many did, indicating that a subset of RNA-containing granules resides precisely at the synapse. As the distance from the cell body increased, the RNA granules were more likely to be found at the edge of the process, perhaps at the base of spines (see Fig. 3a). As indicated in Figure 3, some granules were present within a cluster of synapses that fall within the range of oscillatory movements.

KCl depolarization of neurons leads to an increase in the percentage of anterograde-moving granules

We sought to determine whether depolarization of the neurons altered the steady-state distribution of the granules and perturbed their motility characteristics. KCl depolarization causes BDNF and TrkB mRNAs to become localized to dendrites in hippocampal cultures and slices (Tongiorgi et al., 1997), and induced seizures causeArc mRNA to become localized to dendrites in hippocampal slices (Roberts et al., 1998; Steward et al., 1998). To determine whether depolarization changes the motility characteristics of CaMKIIα 3′UTR mRNA-containing granules, we raised the KCl concentration from 5 to 10 mm in cells that had been transfected with the dual constructs. Living cells expressing the GFP and CaMKIIα 3′UTR constructs were imaged from 10 to 90 min after the KCl addition. The percentage of motile granules was not increased significantly, but there was a shift in the population from oscillatory to anterograde motile granules. Of 22 granules that were analyzed after KCl, 18% were oscillatory, 55% moved in an anterograde direction, and 27% moved in a retrograde direction (Fig. 7a). The shift from oscillatory to unidirectionally moving granules (compare the baseline distribution of granules given above) raises the possibility that KCl depolarization recruited granules from the oscillatory pool. Although depolarization did not change the average rate of granule movement (see Fig. 6b; oscillatory granules, 0.03 ± 0.01 μm/sec; unidirectional motile granules, 0.05 ± 0.04 μm/sec), a shift toward faster translocation rates (maximum rate, 0.25 μm/sec) did occur with depolarization. This shift probably indicates that the granules experienced fewer pauses. A representative time-lapse series of an anterograde-moving granule from KCl-treated cells is shown in Figure 4b. Increased unidirectional anterograde movements support the tendency toward increased numbers of granules as observed above in the 30 min interval and suggest that even longer intervals would show larger increases. In fact, even within the 5 min interval a subpopulation of cells appeared to have an increased granule density in the presence of KCl.

DISCUSSION

Distribution of CaMKIIα 3′UTR mRNA granules

This distribution is similar to the distribution of the total endogenous population of RNA granules as visualized with the RNA-binding fluorescent dye SYTO 14 (Knowles et al., 1996) and to fluorescently labeled myelin basic protein (MBP) mRNA in microinjected oligodendrocytes (Ainger et al., 1993). Interestingly, the density of the CaMKIIα 3′UTR-containing granules was higher than the density of SYTO 14-labeled granules. In untreated cells a 40-μm-long segment of dendrite contained 16 ± 6 GFP-labeled CaMKIIα 3′UTR granules, whereas in SYTO 14-labeled cells there were 5.5 ± 0.5 RNA granules in an identical segment. The SYTO 14-labeled granules presumably represent the total population of RNA granules, and those granules containing endogenous CaMKIIα mRNA should reside in a subset of them. It is likely that the introduction of CaMKIIα 3′UTR RNA induces the formation of granules. Indeed, in oligodendrocytes more granules are induced when a larger amount of MBP mRNA is microinjected (Ainger et al., 1993). Certainly, dendrites are densely packed with ribosomes, but only a subset of these ribosomes assembles into cohesively motile units termed RNA granules. One trigger for the recruitment of ribosomes and the assembly of RNA granules is likely to be the mRNA, and specifically signals in the 3′UTR. RNA transport often is mediated by RNA-binding proteins such as Staufen (Ferrandon et al., 1994), which associates with bicoid, oskar, and prospero mRNA inDrosophila; the zipcode-binding protein that binds to localization elements in β-actin mRNA (Ross et al., 1997); and the zipcode-binding protein homolog Vera, which binds to Vg1 inXenopus oocytes (Deshler et al., 1998). Currently, it is unknown which signals in the 3′UTR direct granule formation and interactions with RNA-binding proteins and whether the signals in the RNA are also important for association with motor proteins and docking to the cytoskeleton. The RNA labeling system that has been used here will be ideal for determining which elements in the 3′UTR are responsible for each of these functions.

Many of CaMKIIα 3′UTR RNA granules colocalize with synapses, as detected with a synaptophysin marker. In the shaft of a representative dendrite we often observed a cluster of synapses within 3 μm of a granule, thereby allowing granules to sample all of these sites (see below). The CaMKIIα RNA granules are well positioned to contribute to the synthesis of the CaMKIIα kinase, which concentrates in postsynaptic densities opposite glutamatergic terminals (Kennedy, 1998).

Basal motility and KCl depolarization-induced changes in RNA granule motility

Assigning a motility rate to the CaMKIIα 3′UTR RNA granules was complicated by the stop and go nature of granule translocation and the time-lapse imaging techniques used in this study. Cessation of granule movement for highly variable time intervals was frequent. Therefore, the true rate of transport is greater than or equal to the fastest rates measured. The fastest rate measured was 0.13 μm/sec and is consistent with the rates measured for MBP RNA-containing granules in oligodendrocytes (Ainger et al., 1993), SYTO 14-labeled granules (Knowles et al., 1996), and RNA granules associated with GFP–Staufen fusion proteins in hippocampal neurons (Kohrmann et al., 1999). GFP–Staufen-containing granules also have discontinuous movements.

KCl depolarization leads to an increase in CaMKII activity (Bading et al., 1993), and stimulation of hippocampal neurons increases the transcription and localization of a number of RNAs (Mackler et al., 1992; Miyashiro et al., 1994; Tongiorgi et al., 1997; Steward et al., 1998; Schuman, 1999). If the translocation of RNAs in dendrites also has physiological significance, particularly with regard to synaptic plasticity, one might expect their motility properties to respond to synaptic activity. According to the observations here, depolarization of cultured neurons indeed does alter the motility properties of RNA granules that transport the CaMKIIα 3′UTR. Under basal conditions most of the labeled CaMKIIα 3′UTR granules were stationary. The complete absence even of Brownian motion in these granules suggested that they were docked. Triton X-100 extraction of the doubly transfected cells indicated that the granules were resistant to detergent (data not shown) and, therefore, were likely to be attached to the cytoskeleton.

Within a brief observation time interval a small pool of the labeled granules was motile, and one-half of the motile granules were oscillatory. Granules that moved unidirectionally were equally likely to move in the anterograde or retrograde directions. Depolarization induced anterograde granule movements, reduced the oscillatory movements, and reduced the distance that retrograde granules traveled (see Fig. 7). Presumably, depolarization sends a signal that causes CaMKIIα mRNA translocation to activated dendritic regions. Unidirectionally moving granules may derive from an undocked oscillatory pool via a depolarization signal, because the increase in unidirectional anterograde granule movements is concomitant with the decrease in oscillatory movements. Oscillatory granules may be diffusing freely until they engage a motor and become unidirectional. Unidirectionally moving granules also may form de novo, emerge from the cell body, or dislodge from a stationary pool. When the total movement of all granules was summed, their net displacements peaked at zero (Fig. 7b), confirming that these movements generally do not result in significant changes in granule localization but, rather, may represent local adjustments in position. An intriguing possibility is that oscillatory movements represent positional adjustments in relation to a cluster of synapses that all are being sampled by a single granule. The colocalization of many RNA granules with synapses (see Fig. 3b) indirectly supports this idea.

A model for the function of RNA granule motility

It is well established that depolarization can activate multiple “immediate-early” genes (Mackler et al., 1992; Roberts et al., 1998; Steward et al., 1998; Schuman, 1999). The time scales over which transcriptionally based mechanisms can deliver cargo to the dendrites and the rates of RNA translocation we have observed are within similar ranges. One confounder of previous studies was that the presence of new endogenous RNA granules in dendrites after a stimulus could derive from newly transcribed RNA. In the work that has been presented here, an artificial mRNA is added exogenously; therefore, these experiments definitively demonstrate that depolarization-induced translocation does not represent newly transcribed mRNAs exiting from the nucleus. Furthermore, these experiments suggest that CaMKIIα mRNA granules can shift motility characteristics on the basis of signals in the 3′UTR alone, because our constructs are under the control of a constitutive promoter that is not affected by depolarization.

Figure 8 shows a model for the role that the translocation of RNA granules to the dendrites plays in response to synaptic activity. Under basal conditions the CaMKIIα 3′UTR is sufficient to signal the formation of RNA granules containing translation machinery and the localization of these granules to the dendrites. Once in the dendrites these granules spend the majority of their time docked to the cytoskeleton, but occasionally they are released and show oscillatory movement, perhaps sampling a local population of synapses. These oscillatory granules usually become stationary again within a few minutes of undocking. When neurons are stimulated, CaMKIIα transcription is activated and RNA transport occurs. At the same time oscillatory granules already in the dendrites move unidirectionally anterograde, perhaps traveling to specific synapses or simply moving from local RNA reservoirs at junctions into more distal dendrites. Although it has been established that local translation can occur in dendrites (Crino and Eberwine, 1996; Kang and Schumann, 1996; Ouyang et al., 1999; Huber et al., 2000), what is the function of an activity-related mechanism for delivering additional mRNAs and translational machinery to dendritic sites? The rapidity of local translational response to activity and the ability to exert local control over translation offer functional advantages. However, these rationales do not apply to the delivery of new mRNAs that arrive at more distant synaptic sites within time frames comparable to the arrival of proteins. Therefore, delivery of RNA granules probably does not meet the immediate needs of an activated synapse. These needs are supplied by translation of the RNAs already present at the site. One possibility is that granule motility may provide fine local adjustments in the number of granules within specific dendritic branches. The shift from oscillatory to unidirectional granule motility suggests that depolarization may affect the localization of subsets of RNA granules already in the dendrites. More interestingly, the delivery of additional mRNAs allows a neurite to reflect its experience—increased activity will draw in more RNA granules that will be available for translation with persistent stimulation.

Fig. 8.

A model for the function of RNA granule motility. Under basal conditions RNA is transcribed and directed by the 3′UTR to dendrites. Within the recording interval many granules appear stationary and cluster at junctions. Some granules are motile and move in an oscillatory manner, perhaps to sample a small number of synapses. KCl depolarization activates transcription of endogenous (but not GFP-labeled) CaMKIIα mRNA and initiates CaMKIIα translation at synapses within localized RNA granules. RNA granules drawn from the oscillatory pool translocate to activated synapses where they cluster and the local translation occurs. GFP-labeled CaMKIIα 3′UTR mRNA-containing granules are shown as circles.Arrows denote moving granules; granules withtwo-directional arrows are oscillatory. Microtubules are shown as black bars. Arrows at synapses represent activation. Tx, Transcription.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AG06601 and NASA Grant NAG2-964 to K.S.K. and a Lefler fellowship and National Institutes of Health training grant to M.S.R. We thank Mark Mayford for the CaMKIIα DNA, Robert Singer for the RSVβ-gal vector, James Williamson and Regina Burris for the GFP-MS2 plasmid, and all for their helpful discussions.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Kenneth S. Kosik, Center for Neurological Diseases, Brigham and Women's Hospital, HIM 760, 77 Avenue Louis Pasteur, Boston, MA 02115. E-mail:kosik@cnd.bwh.harvard.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ainger K, Avossa D, Morgan F, Hill SJ, Barry C, Barbarese E, Carson JH. Transport and localization of exogenous myelin basic protein mRNA microinjected into oligodendrocytes. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:431–441. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.2.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bading H, Ginty DD, Greenberg ME. Regulation of gene expression in hippocampal neurons by distinct calcium signaling pathways. Science. 1993;260:181–186. doi: 10.1126/science.8097060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassell GJ, Singer RH, Kosik KS. Association of poly(A) mRNA with microtubules in cultured neurons. Neuron. 1994;12:571–582. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beach D, Salmon E, Bloom K. Localization and anchoring of mRNA in budding yeast. Curr Biol. 1999;9:569–578. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertrand E, Chartrand P, Schaefer M, Shenoy SM, Singer RH, Long RM. Localization of ASH1 mRNA particles in living yeast. Mol Cell. 1998;2:437–445. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgin KE, Waxham MN, Rickling S, Westgate SA, Mobley WC, Kelly PT. In situ hybridization histochemistry of Ca2+ calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in developing rat brain. J Neurosci. 1990;10:1788–1798. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-06-01788.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crino PB, Eberwine J. Molecular characterization of the dendritic growth cone: regulated mRNA transport and local protein synthesis. Neuron. 1996;17:1173–1187. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80248-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deshler J, Highett M, Abramson T, Schnapp B. A highly conserved RNA-binding protein for cytoplasmic mRNA localization in vertebrates. Curr Biol. 1998;8:489–496. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrandon D, Elphick L, Nusslein-Volhard C, Johnston DS. Staufen protein associates with the 3′UTR of bicoid mRNA to form particles that move in a microtubule-dependent manner. Cell. 1994;79:1221–1232. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guzowski JF, McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, Worley PF. Environment-specific expression of the immediate-early gene Arc in hippocampal neuronal ensembles. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:1120–1124. doi: 10.1038/16046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoek K, Kidd G, Carson J, Smith R. hnRNP A2 selectively binds the cytoplasmic transport sequence of myelin basic protein mRNA. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7021–7029. doi: 10.1021/bi9800247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huber KM, Kayser MS, Bear MF. Role for rapid dendritic protein synthesis in hippocampal mGluR-dependent long-term depression. Science. 2000;288:1254–1256. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang H, Schumann E. A requirement for local protein synthesis in neurotrophin-induced hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Science. 1996;273:1402–1406. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy MB. Signal transduction molecules at the glutamatergic postsynaptic membrane. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;26:243–257. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiebler MA, DesGroseillers L. Molecular insights into mRNA transport and local translation in the mammalian nervous system. Neuron. 2000;25:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80868-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiebler MA, Hemraj I, Verkade P, Kohrmann M, Forbes P, Marion R, Ortin J, Dotti C. The mammalian Staufen protein localizes to the somatodendritic domain of cultured hippocampal neurons: implications for its involvement in mRNA transport. J Neurosci. 1999;19:288–297. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00288.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knowles RB, Sabry JH, Martone ME, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Bassell GJ, Kosik KS. Translocation of RNA granules in living neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7812–7820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-24-07812.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohrmann M, Luo M, Kaether C, DesGroseillers L, Dotti CG, Keibler MA. Microtubule-dependent recruitment of Staufen–green fluorescent protein into large RNA-containing granules and subsequent dendritic transport in living hippocampal neurons. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:2945–2953. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.9.2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Link W, Konietzko U, Kauselmann G, Krug M, Schwanke B, Frey U, Kuhl D. Somatodendritic expression of an immediate early gene is regulated by synaptic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5734–5738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyford GL, Yamagata K, Kaufmann WE, Barnes CA, Sanders LK, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Lanahan AA, Worley PF. Arc, a growth factor and activity-regulated gene, encodes a novel cytoskeleton-associated protein that is enriched in neuronal dendrites. Neuron. 1995;14:433–445. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90299-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackler SA, Brooks BP, Eberwine JH. Stimulus-induced coordinate changes in mRNA abundance in single postsynaptic hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1992;9:539–551. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90191-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Long-term potentiation—a decade of progress? Science. 1999;285:1870–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martone ME, Pollock JA, Jones YZ, Ellisman MH. Ultrastructural localization of dendritic messenger RNA in adult rat hippocampus. Mol Neurobiol. 1996;16:7437–7446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07437.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayford M, Baranes D, Podsypanina K, Kandel E. The 3′-untranslated region of CaMKIIα is a cis-acting signal for the localization and translation of mRNA in dendrites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13250–13255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyashiro K, Dichter M, Eberwine J. On the nature and differential distribution of mRNAs in hippocampal neurites: implications for neuronal functioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10800–10804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ouyang Y, Rosenstein A, Kreiman G, Schuman EM, Kennedy MB. Tetanic stimulation leads to increased accumulation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II via dendritic protein synthesis in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7823–7833. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-07823.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts LA, Large CH, Higgins MJ, Stone TW, O'Shaughnessy CT, Morris JB. Increased expression of dendritic mRNA following the induction of long-term potentiation. Mol Brain Res. 1998;56:38–44. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross A, Oleynikov Y, Kislauskis E, Taneja K, Singer R. Characterization of a β-actin mRNA zipcode-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2158–2165. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuman EM. mRNA trafficking and local protein synthesis at the synapse. Neuron. 1999;23:645–648. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steward O. mRNA localization in neurons: a multipurpose method? Neuron. 1997;18:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steward O, Fass B. Polyribosomes associated with dendritic spines in the denervated dentate gyrus: evidence for local regulation of protein synthesis during reinnervation. Prog Brain Res. 1983;58:131–136. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steward O, Levy W. Preferential localization of polyribosomes under the base of dendritic spines in granule cells of the dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 1982;2:284–291. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-03-00284.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steward O, Wallace C, Lyford G, Worley P. Synaptic activation causes the mRNA for the IEG Arc to localize selectively near activated postsynaptic sites on dendrites. Neuron. 1998;21:741–751. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Theurkauf W, Hazelrigg T. In vivo analyses of cytoplasmic transport and cytoskeletal organization during Drosophila oogenesis: characterization of a multi-step anterior localization pathway. Development. 1998;125:3655–3666. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.18.3655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas KL, Laroche S, Errington ML, Bliss TVP, Hunt SP. Spatial and temporal changes in signal transduction pathways during LTP. Neuron. 1994;13:737–745. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tongiorgi E, Righi M, Cattaneo A. Activity-dependent dendritic targeting of BDNF and TrkB mRNAs in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9492–9505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-24-09492.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang S, Hazelrigg T. Implications for bcd mRNA localization from spatial distribution of Exu protein in Drosophila oogenesis. Nature. 1994;369:400–403. doi: 10.1038/369400a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]