Abstract

The intercalated cell masses of the amygdala are clusters of GABAergic neurons located strategically to influence behavioral responsiveness. Indeed, they receive glutamatergic sensory inputs from the basolateral amygdaloid complex and generate feedforward inhibition in neurons of the central amygdala that mediate important components of fear responses. In the present study, using whole-cell recording methods in coronal slices of the guinea pig amygdala, we show that the activity of intercalated neurons is a function of their recent firing history because they express an unusual voltage-dependent K+ conductance (termedISD for slowly deinactivating). This conductance activates in the subthreshold regime, inactivates in response to suprathreshold depolarizations, and deinactivates very slowly upon return to rest. As a result, after bouts of suprathreshold activity, these cells enter a self-sustaining state of heightened excitability associated with an increased input resistance and a membrane depolarization. In turn, these changes increase the likelihood that ongoing synaptic activity will trigger orthodromic action potentials. However, because each orthodromic spike “renews” the inactivation of ISD, intercalated cells can remain hyperexcitable for a long time and, via the central amygdaloid nucleus, exert a lasting influence on behavior.

Keywords: amygdala, intercalated cell masses, inhibition, potassium current, afterdepolarization, whole-cell recording, guinea pig

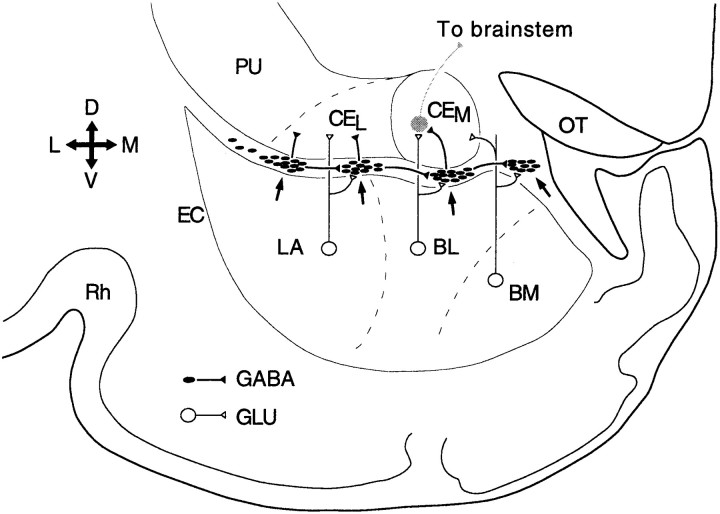

Two key elements in the amygdala circuitry underlying fear (Kapp et al., 1992; Davis et al., 1994;LeDoux, 1995) are the basolateral amygdaloid complex and central nucleus of the amygdala (Fig. 1). Indeed, most sensory inputs from the thalamus and cortex end in the basolateral complex (Turner and Herkenham, 1991; McDonald, 1998), whereas the central nucleus is the main source of brainstem projections mediating fear responses (Hopkins and Holstege, 1978; Kapp et al., 1979; Veening et al., 1984; Gentile et al., 1986; Iwata et al., 1986; Zhang et al., 1986; Hitchcock et al., 1989).

Fig. 1.

Connectivity of the intercalated cell masses. Scheme of a coronal section through the amygdaloid complex of the guinea pig. ITC cell masses (arrows) receive glutamatergic inputs from components of the basolateral complex [namely, the lateral (LA), the basolateral (BL), and the basomedial (BM) nuclei] and contribute a GABAergic projection to the lateral and medial sectors of the central nucleus (CEL andCEM, respectively). ITC cell masses are interconnected by lateromedial connections. EC, External capsule; OT, optic tract; PU, putamen; Rh, rhinal sulcus; D, dorsal;M, medial; V, ventral; L, lateral.

However, interposed between the basolateral complex and central nucleus are clusters of GABAergic neurons (Fig. 1, arrows), termed intercalated (ITC) cell masses (Millhouse, 1986; Nitecka and Ben-Ari, 1987; McDonald and Augustine, 1993; Paré and Smith, 1993a). ITC neurons receive excitatory afferents from the basolateral amygdaloid complex (Royer et al., 1999, 2000) and project to the central nucleus of the amygdala (Paré and Smith, 1993b). ITC neurons thus occupy a strategic position to influence behavioral responsiveness.

In agreement with this, we have shown recently that ITC cells generate feedforward inhibition in the central nucleus (Royer et al., 1999). Moreover, because laterally located ITC cell masses inhibit more medial ones (Royer et al., 2000), ITC neurons can gate impulse traffic between the basolateral complex and central nucleus in a spatiotemporally differentiated manner (Royer et al., 1999) (Fig. 1). In the course of these experiments, we have noticed that many ITC cells are endowed with an unusual property, namely the ability to generate prolonged depolarizing plateaus after transient depolarizations. The present study analyzes the underlying mechanisms and considers their implications for the expression of fear responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of amygdala slices. Coronal slices of the amygdala were obtained from Hartley guinea pigs (∼250 gm). Before decapitation, the animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital (40 mg/kg, i.p.) and ketamine (100 mg/kg, i.p.), in agreement with the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care, as approved by the local ethics committee of University Laval. The brain was removed and placed in an oxygenated solution (4°C) containing (in mm): 126 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 glucose. Coronal sections (400 μm) were prepared with a vibrating microtome. The slices were stored for 1 hr in an oxygenated chamber at room temperature. One slice was then transferred to a recording chamber perfused with an oxygenated physiological solution at a rate of 2 ml/min. The temperature of the chamber was gradually increased to 32°C before the recordings began.

Data recording and analysis. Recordings were obtained with borosilicate pipettes filled with a solution containing (in mm): 130 K-gluconate, 10 HEPES, 10 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 ATP-Mg, and 0.2 GTP-Tris. pH was adjusted to 7.2, and osmolarity was adjusted to 280–290 mOsm. With this solution, the liquid junction potential was measured (10 mV), and the membrane potential was corrected accordingly. The pipettes had resistances of 4–8 MΩ when filled with the above solution. Recordings with series resistance higher than 15 MΩ were discarded. To this end, bridge balance was monitored regularly during the recordings.

Current-clamp recordings were obtained with an Axoclamp 2B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) under visual control using differential interference contrast and infrared video microscopy. SeeRoyer et al. (1999, 2000) for the criteria used to distinguish intercalated neurons from cells in neighboring nuclei. All the neurons described in this study had a Vm equal or negative to −60 mV (average of −75.6 ± 0.94 mV;n = 110) and overshooting action potentials.

Drugs were applied in the perfusate. Electrical stimuli consisted of 50–300 μsec current pulses (0.1–1 mA) passed through pairs of tungsten electrodes placed in the basolateral amygdala.

Analyses were performed off-line with the software IGOR (WaveMetrics Inc., Lake Oswego, OR) and homemade software running on Macintosh microcomputers (Apple Computers, Cupertino, CA). Statistical significance of the results was determined with paired ttests (two-tailed). All values are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

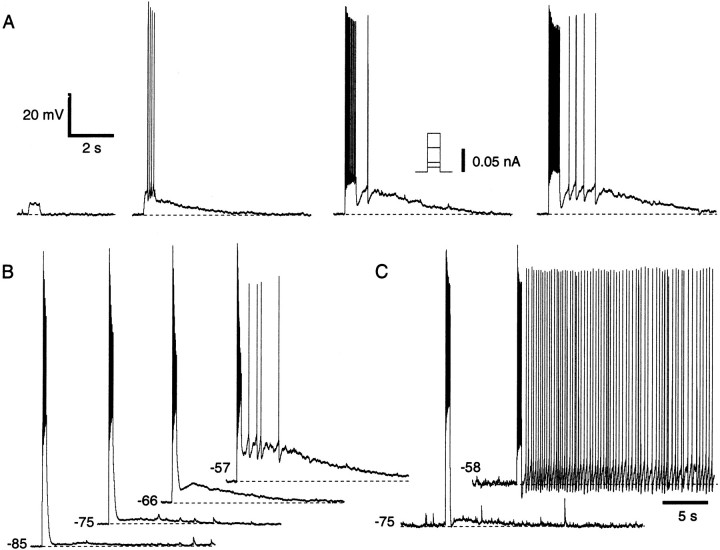

Intercalated neurons generate prolonged afterdepolarizations

In many ITC neurons (52%; n = 110), suprathreshold current pulses evoked a slow afterdepolarization (ADP) (Fig. 2) whose amplitude (up to 19 mV) increased with the number of evoked spikes (Fig. 2A) and with depolarization of the prepulse membrane potential (Vm) (Fig. 2B). When the prepulse Vm was depolarized beyond −65 mV, these ADPs often reached spike threshold (37%). In such cases, the ADP duration increased, and, in 9% of the cells, it continued indefinitely until the neuron was repolarized (Fig.2C). There was no systematic relationship between the position of intercalated neurons and the likelihood that they would display the ADP. However, when one intercalated neuron displayed the ADP, the probability that intercalated cells located in the same cluster would display ADPs seemed higher.

Fig. 2.

Suprathreshold depolarizations elicit ADPs in ITC cells. A, Depolarizing current pulses of gradually increasing amplitude (left to right), applied at −60 mV. B, Depolarizing current pulses adjusted to elicit approximately the same number of spikes were delivered from different Vm values.C, Spike trains elicited from depolarizedVm values lead to tonic firing. Voltage scale is the same for A–C. Time scale is the same forA and B.

The ADPs were not dependent on GABA release because they were unaffected when GABA receptor antagonists (bicuculline, 10 μm; saclofen, 200 μm) were added to the perfusate, alone or in combination with glutamate receptor blockers (6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, 20 μm; D(−)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid, 50 μm;n = 10).

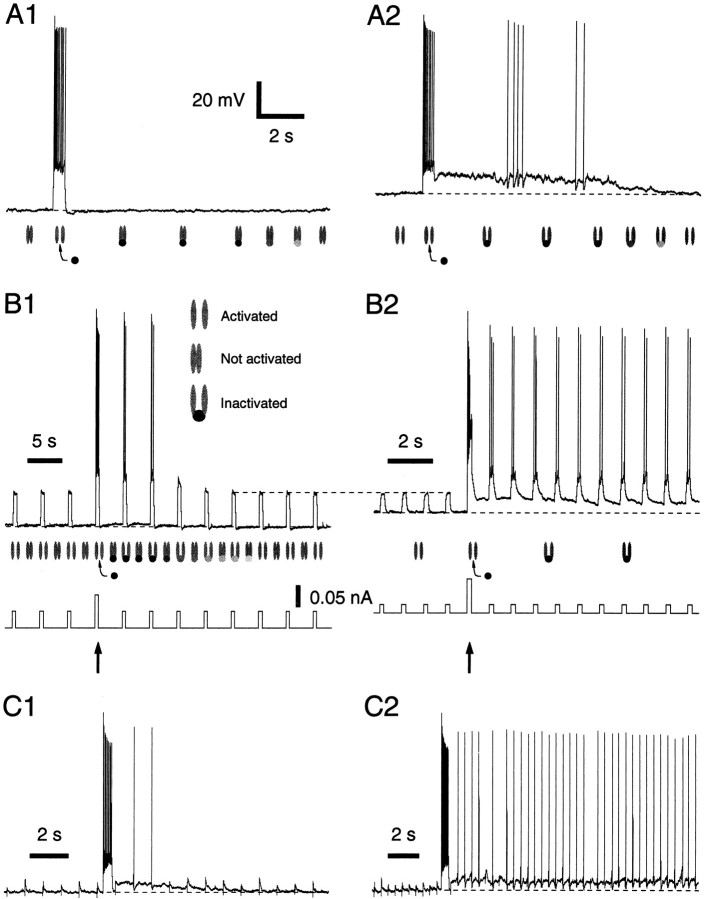

Moreover, Na+ entry through voltage-gated channels was not required, because the ADPs persisted in the presence of tetrodotoxin [(TTX) 0.5 μm; amplitude change, −10.6 ± 6.10%; t test; p > 0.05;n = 12] (Fig.3A2). Thus, in Figure2A, the ADP amplitude increased with the number of spikes because the Na+ influx produced a depolarization, not because the Na+concentration changed.

Fig. 3.

ADP does not depend on Na+ or Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated channels but is associated to an Rin increase.A, ADP response in control conditions (A1), in the presence of 0.5 μm TTX (A2), and after substitution of Ca2+with Mg2+ and the addition of BAPTA-AM (50 μm) to the Ringer's solution for 30 min (A3). Same cell in all conditions.Vm, −60 mV. Rest, −81 mV.B, Effect of Cd2+ (100 μm), La3+ (100 μm), and replacement of Ca2+ with Co2+ on the ADP. We returned to control Ringer's solution between each treatment. Cd2+ and La3+increased the amplitude of the ADP, presumably because they reduced Ca2+-dependent K+ conductances, thus increasing the input resistance. C, Voltage response to current pulses (−0.01 nA) before and after ADP induction. During the ADP, current (bottom trace) was manually injected into the cells to maintain the Vmat a constant value.

Similarly, the ADPs did not depend on Ca2+influx through voltage-gated channels because they persisted after substitution of Ca2+ with Mg2+ coupled to the addition of a membrane-permeant Ca2+ chelator (amplitude change, −3.0 ± 4.36%; t test; p > 0.05; n = 5) (Fig. 3A3). Here, it should be noted that, when the latter treatment was performed in the absence of TTX (n = 3), electrically evoked synaptic responses were abolished and spontaneous synaptic activity was greatly reduced (data not shown).

In support of the above, the ADP also resisted application of the Ca2+ channel blockers La3+ (100 μm;n = 3) or Cd2+ (100 μm; n = 3). In fact, these ions produced a small increase in ADP amplitudes (Fig.3B1,B2, average increase of 7.4 ± 7.0 and 16.5 ± 14.5%, respectively; see figure legend). Surprisingly, substitution of Ca2+ with Co2+ (Fig. 3B3) abolished the ADP (n = 3; average reduction of −87.7 ± 8.2%). However, the resistance of the ADP to the above treatments raises the possibility that Co2+ ions do not block the ADP by inhibiting Ca2+ influx but via another mechanism, such as by blocking a K+ conductance (Mathie et al., 1998). Evidence in support of this contention is provided below.

The ADPs are mediated by the closing of a K+ conductance

When the depolarization occurring during the ADP was prevented by current injection (manual clamp), the ADP was found to be associated with an increased input resistance (Rin), as evidenced by significantly augmented voltage responses to hyperpolarizing current pulses (Fig.3C) (t test; p < 0.05;n = 4; peak Rinincreases of 46 ± 3.3%).

This result led us to suspect that the ADP was generated by the inactivation of a K+ conductance, which recovered very slowly from inactivation. Below, when referring to this putative current, we will use the designationISD (slowly deinactivating) for simplicity.

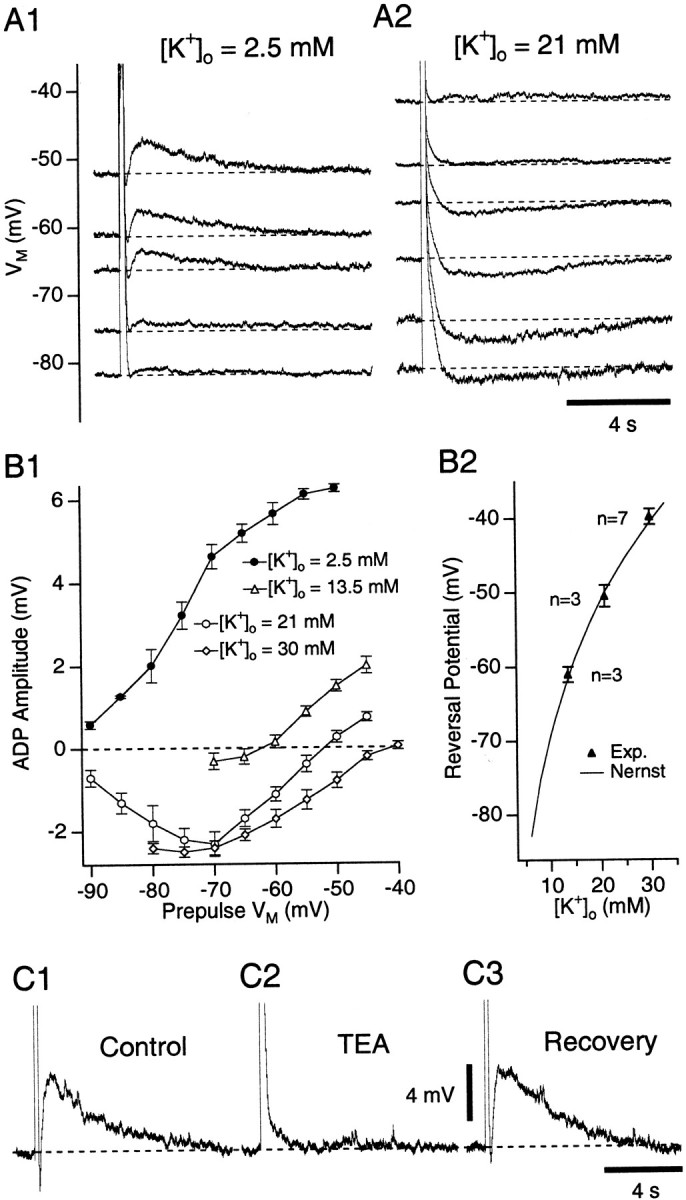

Consistent with our hypothesis, the amplitude of the ADPs varied in a Nernstian manner with the extracellular K+concentration ([K+]o) (Fig.4). ADPs elicited by current pulses to 0 mV were examined in the presence of TTX with [K+]o of 2.5, 13.5, 21, or 30 mm. With physiological [K+]o (2.5 mm), the ADPs increased in amplitude with depolarization of the prepulse Vm (Fig.4A1,B1, filled circles). In contrast, with 21 mm[K+]o (Fig.4A2), the same stimuli elicited afterhyperpolarizations (AHPs), which first increased in amplitude from prepulse Vm values of −90 to −70 mV (Fig. 4B1, open circles) and then decreased as the prepulse Vmapproached the K+ equilibrium potential. In fact, with all of the high [K+]o tested, a close correspondence was found between the predicted K+ equilibrium potential (Fig.4B2, continuous line) and the prepulseVm at which no afterpotential was evoked (Fig. 4B2, filled triangles).

Fig. 4.

ADP varies in a Nernstian manner with [K+]o and is reduced by TEA.A, ADP induction by depolarizing pulses to ∼0 mV from different Vm values with [K+]o of 2.5 (A1) and 21 (A2) mm. TTX (0.5 μm) was present. B1, Relationship between ADP amplitude and prepulse potential for [K+]o of 2.5 (filled circles), 13.5 (open triangles), 21 (open circles), and 30 (open diamonds) mm.B2, ADP reversal potential as a function of [K+]o (filled triangles). Continuous line, Nernst prediction.C, Response to depolarizing pulses to 0 mV in Ringer's solution (C1), with 40 mm TEA (C2), and after 30 min in control Ringer's solution (C3). TTX (0.5 μm) was present throughout. Prepulse Vm was −60 mV.

In 21 mm[K+]o (Fig.4B1, open circles), note that the AHP amplitude gradually increased from prepulseVm values of −90 to −70 mV despite the progressively diminishing driving force acting on K+. This suggests that the activation ofISD increases with depolarization in this range of Vm values.

Finally, addition of the K+ channel blockers tetraethylammonium (TEA) or 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) to the perfusate reduced the ADP in a dose-dependent manner. TEA concentrations of 40 mm reduced ADP amplitudes by 78 ± 7.1% (Fig. 4C) (n = 7). Only partial blockade (41 ± 13.5%; n = 5) was seen with 4-AP concentrations of 40 mm. Importantly, the ADP was unaffected by 5 mm 4-AP (average amplitude change of 6 ± 5.4%; n = 3), concentrations sufficient to block IA andID in most neurons (Rudy, 1988). Moreover, the class III antiarrhythmicsd-sotalol (100 μm) produced a minor reduction in ADP amplitude (n = 3; 22 ± 20.3%), whereas bretylium (100 μm;n = 3) and amiodarone (10 μm;n = 3) had no effect.

Time and voltage dependence of the K+ current underlying the ADP

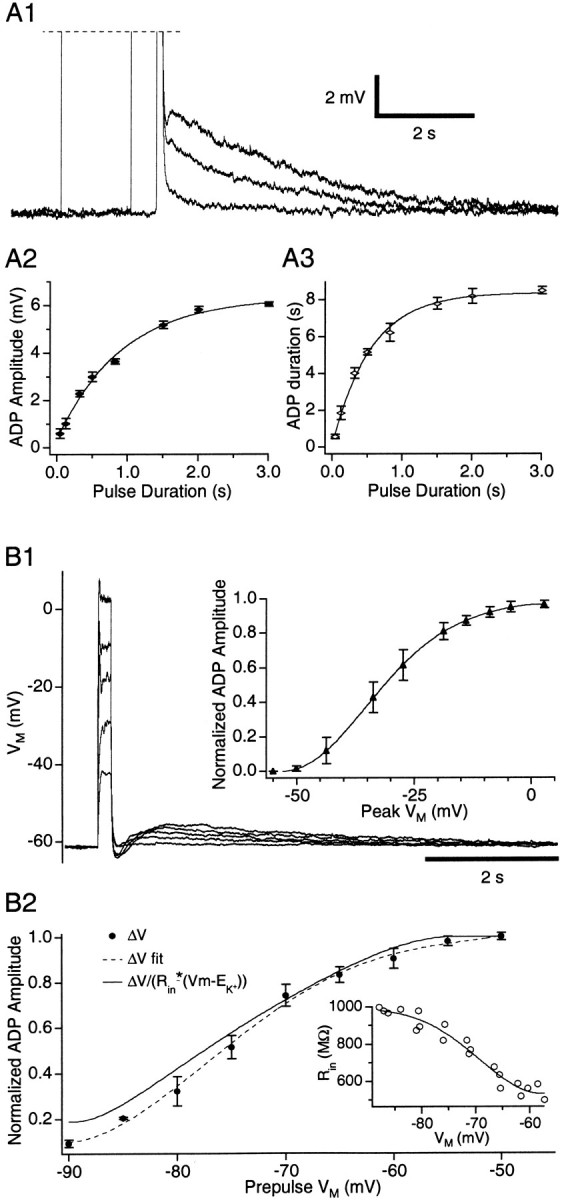

In the presence of TTX, the ADP amplitude and duration increased gradually to a plateau when depolarizing current pulses of gradually increasing duration (but of constant amplitude) were applied. Such tests are shown in Figure 5A. In these cases (n = 3), the current amplitude was adjusted to bring the Vm to ∼0 mV (Fig. 5A1). Note the parallel increase in ADP amplitude (Fig. 5A2) and duration (Fig. 5A3) produced by augmenting the length of the current injection (time constant of 0.91 and 0.55 sec, respectively).

Fig. 5.

Time and voltage dependence of the ADP.A, Effect of changes in pulse duration (A1) on ADP amplitude (A2) and duration (A3). B1, Depolarizing pulses of increasing amplitudes from −60 mV. Insets, Normalized ADP amplitude (filled triangles) versus the peakVm reached during the current pulses (n = 7). B2, Normalized ADP amplitude (filled circles) caused by depolarizing current pulses to 0 mV as a function of the prepulseVm (n = 7).Dashed line is a polynomial fit of the data.Continuous line fits the data after correction for changes in K+ driving force andRin. Inset, Changes inRin (open circles) estimated by measuring voltage responses to current pulses of ±0.01 nA in the same cells.

Judging from maximal ADP amplitudes (<20 mV) and the highRin of ITC cells at −60 mV (∼600 MΩ), ISD should be ≤30 pA. Because such low-current amplitudes would greatly complicate voltage-clamp analyses, we used current-clamp methods to estimate the voltage dependence of effective ISD inactivation and activation (to be distinguished from Hodgkin–Huxley parameters). In other words, we inferred the properties of the window current generated by ISD on the basis of our current-clamp recordings.

First, we examined the amplitude of ADPs generated by depolarizing current pulses of increasing intensity applied at constant prepulseVm values, in the presence of TTX (Fig. 5B1). For a prepulseVm of −60 mV, a sigmoid relationship was found between the normalized ADP amplitude and the peakVm evoked by the current pulse (Fig.5B1). The ADP reached half-amplitude at −30 mV and saturated at 0 mV (Fig. 5B1, inset) (n = 7). Importantly, a similar relationship was observed with prepulse potentials between −90 and −60 mV. Because the ADPs are caused by the inactivation ofISD, these results imply thatISD effectively inactivates in the suprathreshold range of Vm.

For depolarizing pulses that completely inactivatedISD (Fig. 5B1, saturation), the ADP amplitude depended on the prepulseVm for several reasons: it affects the driving force acting on K+ ions, theRin (Fig. 5B2,inset), and ISD presumably activates in a voltage-dependent manner (Fig. 4B1,open circles). Thus, to estimate the voltage dependence of effective activation, we used: gv = ΔVv/(Rinv* (V − Ek)), where ΔVv is the amplitude of the ADP elicited from a particular prepulse potential,Rinv is theRin at this potential (see figure legend), and Ek is the K+ equilibrium potential (−105 mV). The normalized amplitude of the ADP varied as a function of the prepulse potential (Fig. 5B2, filled circles with dashed line). The continuous line (gv) was obtained after correction of the data for the K+ driving force and Rin. Assuming that the depolarizing pulses caused a complete inactivation ofISD,gv should reflect the effective activation of ISD at each prepulseVm value.

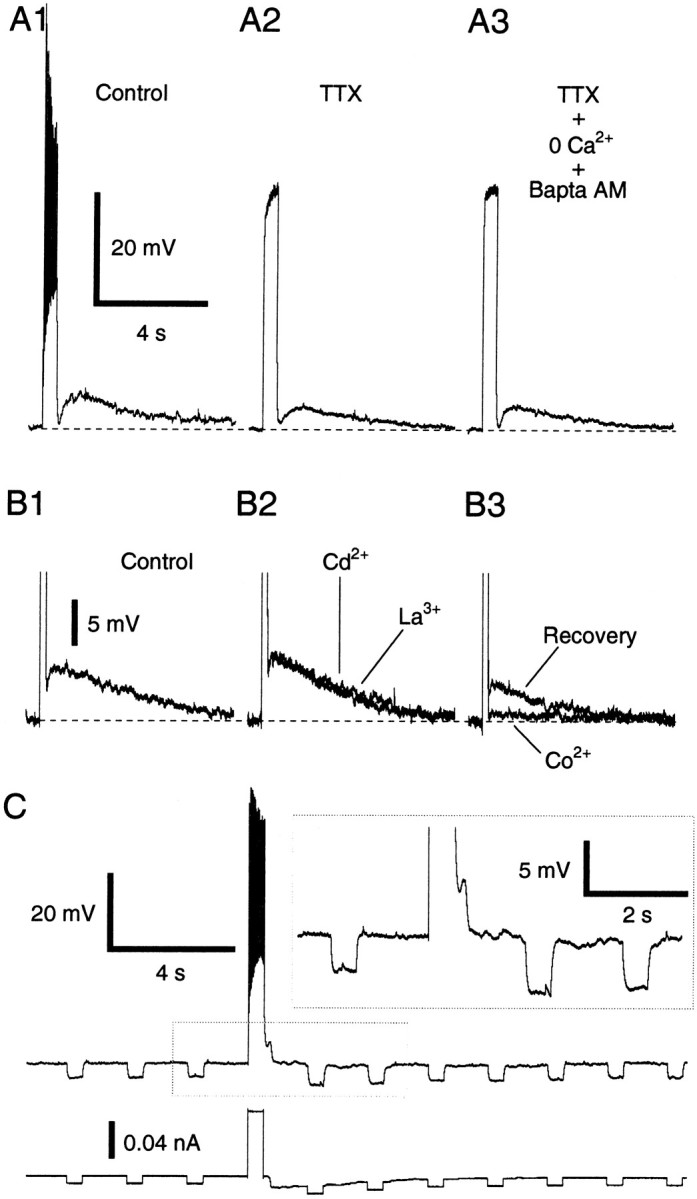

The above analysis suggests the following explanation for the genesis of ADPs. At hyperpolarized Vm values (Fig. 6A1), the inactivation of ISD caused by suprathreshold depolarizations elicits little or no ADPs becauseISD was weakly activated before the current pulse (Fig. 6A1, symbols) and the driving force acting on K+ is small. In contrast, at more depolarized Vmvalues (Fig. 6A2), the activation ofISD is more important, and the inactivation caused by suprathreshold depolarizations results in an ADP that subsides slowly as ISDprogressively deinactivates (Fig. 6A2,symbols).

Fig. 6.

Impact of ISD on ITC responsiveness. A, Changes in the degree of activation of ISD when suprathreshold current pulses are applied from −75 (A1) or −62 (A2) mV. Symbols below traces indicate the hypothesized state of the channels. B, Voltage response (top trace) to repetitive current pulses (bottom trace) applied from a Vm of −74 (B1) or −66 (B2) mV. C, Response to repetitive electrical stimuli in the basolateral complex delivered at two different frequencies before versus after a suprathreshold current pulse from −60 mV. Voltage scale is the same for A–C.

Physiological consequences of the persistent inactivation ofISD

To test the impact of ISD on the behavior of ITC cells, subthreshold current pulses of constant amplitude were injected repeatedly before and after eliciting a spike train with a suprathreshold pulse (Fig. 6B,arrows) (n = 10). When the trials were performed at Vm values negative to approximately −80 mV (Fig. 6B1), little or no ADP was observed after the spike train, but the next few pulses, which were previously subthreshold, became suprathreshold (see figure legend). Similar results were obtained when the trials were performed at more depolarized Vm values (Fig.6B2), with two exceptions: an ADP was evoked and the increased responsiveness persisted longer. In fact, when the interpulse interval was adjusted correctly (≤1 sec), it persisted indefinitely, presumably because the spikes evoked by the successive pulses maintained the inactivation of ISD. Importantly, the above results could be reproduced using synaptic inputs instead of current pulses (Fig. 6C), in six of eight tested cells.

DISCUSSION

In most cell types, ADPs are mediated by a Ca2+-activated nonspecific cationic current (mostly Na+) and often require the application of cholinergic agonists (Schwindt et al., 1988; Andrade, 1991; Bal and McCormick, 1993; Caeser et al., 1993; Fraser and MacVicar, 1996; Haj-Dahmane and Andrade, 1998). Several results suggest that the ADPs displayed by ITC cells are generated otherwise. Indeed, they survive manipulations preventing rises in intracellular Ca2+ concentration or synaptic transmission, they are associated to an augmentedRin, they fluctuate in a Nernstian manner with [K+]o, and they are reduced by K-channel blockers. Such properties would not be expected with a nonspecific cationic current.

In light of these findings, we suggest that the ADPs displayed by ITC neurons result from the closing of a K+conductance (tentatively termed ISD). Although its precise voltage dependence was not determined in the present study, it could be estimated by analyzing fluctuations in ADP amplitude produced by graded depolarizations from a constantVm or depolarizations to a constant value from different prepulse potentials. These analyses revealed thatISD begins to activate with depolarization in the subthreshold regime and that it effectively inactivates during suprathreshold depolarizations. After repolarization, ISD deinactivates very slowly, giving rise to ADPs lasting seconds.

These are unusual features for a K+conductance (Rudy, 1988; Hille, 1992; Coetzee et al., 1999). In fact,ISD does not seem to match previously described K+ channels, with the possible exception of those belonging to the ERG group, which have a similar voltage dependence (Ganetzky et al., 1999). Yet, even in this case, the correspondence is imperfect because the deinactivation of ERG channels is faster by one order of magnitude (Ganetzky et al., 1999).

The fact that ISD effectively activates and inactivates in partially nonoverlapping ranges of potentials, coupled to its slow deinactivation, confer unusual electroresponsive properties on cells expressing this current. Consider the example of a neuron maintained at approximately −60 mV by ongoing network activity. At this Vm,ISD will reach near maximal effective activation. As a result, the responsiveness of this cell to excitatory synaptic inputs will depend on its recent firing history. Indeed, repetitive spiking will switch the cell to a more excitable state because it will inactivate ISD, thereby increasing the Rin and moving the Vm closer to spike threshold. Thus, the cell will have a higher probability of responding to excitatory inputs. Moreover, because each orthodromic spike will tend to “renew” the inactivation ofISD, the cell might remain in this state for a prolonged period of time.

These findings take on a particular significance in ITC cells. Indeed, there is a lateromedial correspondence between the position of ITC cells, their projection site in the central nucleus, and the source of their afferents in the basolateral complex (Royer et al., 1999) (Fig.1). Furthermore, ITC neurons inhibit each other, with intra-ITC connections preferentially running in a lateromedial direction (Royer et al., 2000) (Fig. 1). Because of these intrinsic connections, the feedforward inhibition generated by ITC neurons and, indirectly, the amplitude of the responses of central neurons depend on which combination of basolateral nuclei are activated and in what sequence. Thus, increases in the responsiveness of particular ITC clusters (via the inactivation of ISD) can bias this network to dampen excitatory inputs to specific population of central neurons and enhance the responses of others via lateromedial inhibitory ITC connections. Such modal shifts in the excitability of ITC cells could profoundly alter emotional reactivity because neurons of the central nucleus, via their projections to the brainstem and hypothalamus, play a critical role in the expression of fear (Kapp et al., 1992; Davis et al., 1994; LeDoux, 1995).

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Canadian Medical Research Council.

Correspondence should be addressed to Denis Paré, Département de Physiologie, Faculté de Médecine, Université Laval, Québec, Canada G1K 7P4. E-mail:denis.pare@phs.ulaval.ca.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrade R. Cell excitation enhances muscarinic cholinergic responses in rat association cortex. Brain Res. 1991;548:81–93. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91109-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bal T, McCormick DA. Mechanisms of oscillatory activity in guinea-pig nucleus reticularis thalami in vitro: a mammalian pacemaker. J Physiol (Lond) 1993;468:669–691. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caeser M, Brown DA, Gähwiler BH, Knöpfel T. Characterization of a calcium-dependent current generating a slow afterdepolarization of CA3 pyramidal cells in rat hippocampal slice cultures. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:560–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coetzee WA, Amarillo Y, Chiu J, Chow A, Lau D, McCormack T, Moreno H, Nadal MS, Ozaita A, Poutney D, Saganich M, Vega-Saenz De Miera E, Rudy B. Molecular diversity of K+ channels. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;868:233–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis M, Rainnie D, Cassel M. Neurotransmission in the rat amygdala related to fear and anxiety. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:208–214. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraser DD, MacVicar BA. Cholinergic-dependent plateau potential in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4113–4128. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04113.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganetzky B, Robertson GA, Wilson GF, Trudeau MC, Titus SA. The Eag family of K+ channels in Drosophila and mammals. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;868:356–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gentile CG, Jarrell TW, Teich AH, McCabe PM, Schneiderman N. The role of amygdaloid central nucleus in differential Pavlovian conditioning of bradycardia in rabbits. Behav Brain Res. 1986;20:263–276. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(86)90226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haj-Dahmane S, Andrade R. Ionic mechanisms of the slow afterdepolarization induced by muscarinic receptor activation in rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1197–1210. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.3.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hille B. Ionic channels of excitable membranes, Ed 2. Sinauer; Sunderland, MA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hitchcock JM, Sananes CB, Davis M. Sensitization of the startle reflex by footshock: blockade by lesions of the central nucleus of the amygdala or its efferent pathway to the brainstem. Behav Neurosci. 1989;103:509–518. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.103.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopkins DA, Holstege G. Amygdaloid projections to the mesencephalon, pons and medulla oblongata in the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1978;32:529–547. doi: 10.1007/BF00239551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwata J, LeDoux JE, Meeley MP, Arneric S, Reis DJ. Intrinsic neurons in the amygdaloid field projected to by the medial geniculate body mediate emotional responses conditioned to acoustic stimuli. Brain Res. 1986;383:195–214. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapp BS, Frysinger RC, Gallagher M, Haselton JR. Amygdala central nucleus lesions: effects on heart rate conditioning in the rabbit. Physiol Behav. 1979;23:1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(79)90304-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapp BS, Whalen PJ, Supple WF, Pascoe JP. Amygdaloid contributions to conditioned arousal and sensory information processing. In: Aggleton JP, editor. The amygdala: neurobiological aspects of emotion, memory, and mental dysfunction. Wiley; New York: 1992. pp. 229–254. [Google Scholar]

- 16.LeDoux JE. Emotion: clues from the brain. Annu Rev Psychol. 1995;46:209–235. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.46.020195.001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathie A, Wooltorton JRA, Watkins CS. Voltage-activated potassium channels in mammalian neurons and their block by novel pharmacological agents. Gen Pharmacol. 1998;30:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(97)00034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonald AJ. Cortical pathways to the mammalian amygdala. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;55:257–332. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonald AJ, Augustine JR. Localization of GABA-like immunoreactivity in the monkey amygdala. Neuroscience. 1993;52:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90156-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Millhouse OE. The intercalated cells of the amygdala. J Comp Neurol. 1986;247:246–271. doi: 10.1002/cne.902470209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nitecka L, Ben-Ari Y. Distribution of GABA-like immunoreactivity in the rat amygdaloid complex. J Comp Neurol. 1987;266:45–55. doi: 10.1002/cne.902660105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paré D, Smith Y. Distribution of GABA immunoreactivity in the amygdaloid complex of the cat. Neuroscience. 1993a;57:1061–1076. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90049-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paré D, Smith Y. The intercalated cell masses project to the central and medial nuclei of the amygdala in cats. Neuroscience. 1993b;57:1077–1090. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90050-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Royer S, Martina M, Paré D. An inhibitory interface gates impulse traffic between the input and output stations of the amygdala. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10575–10583. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10575.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Royer S, Martina M, Paré D. Polarized synaptic interactions between intercalated neurons of the amygdala. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:3509–3518. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.6.3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudy B. Diversity and ubiquity of K channels. Neuroscience. 1988;25:729–749. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwindt PC, Spain WJ, Foehring RC, Chubb MC, Crill WE. Slow conductances in neurons from cat sensorimotor cortex in vitro and their role in slow excitability changes. J Neurophysiol. 1988;59:450–467. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.2.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner BH, Herkenham M. Thalamoamygdaloid projections in the rat: a test of the amygdala's role in sensory processing. J Comp Neurol. 1991;313:295–325. doi: 10.1002/cne.903130208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veening JG, Swanson LW, Sawchenko PE. The organization of projections from the central nucleus of the amygdala to brainstem sites involved in central autonomic regulation: a combined retrograde transport immunohistochemical study. Brain Res. 1984;303:337–357. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)91220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang JX, Harper RM, Ni H. Cryogenic blockade of the central nucleus of the amygdala attenuates aversively conditioned blood pressure and respiratory responses. Brain Res. 1986;386:136–145. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]