Abstract

Periodontal disease (PD) is a common dental disease associated with the interaction between a dysbiotic oral microbiota and host immunity. It is a prevalent disease resulting in loss of gingival tissue, periodontal ligament, cementum, and alveolar bone. PD is a major form of tooth loss in the adult population. Experimental animal models have enabled the study of PD pathogenesis and are used to test new therapeutic approaches for treating disease. The ligature-induced periodontitis model has several advantages compared to other models, including rapid disease induction, predictable bone loss, and the capacity to study periodontal tissue and alveolar bone regeneration due to the model being established within the periodontal apparatus. Although mice are the most convenient and versatile animal models used in research, ligature-induced periodontitis has been more frequently used in large animals. This is mostly due to the technical challenges required to consistently place ligatures around murine teeth. To reduce the technical challenge associated with the traditional ligature model, we previously developed a simplified method to easily install the bacterial retentive ligature between 2 molars for inducing periodontitis. In this protocol we provide detailed instructions for placement of the ligature and demonstrate how the model can be used to evaluate gingival tissue inflammation and alveolar bone loss over an 18 day period following ligature placement. This model can also be used on germ free mice to investigate the role of human oral bacteria in periodontitis in vivo. In conclusion, this protocol enables the mechanistic study of the pathogenesis of periodontitis in vivo.

Keywords: Periodontitis; ligature model; Alveolar bone loss; Osteoclast; Inflammation; Host Response, mouse, periodontal disease, gingival tissue, mouse, mice, Germ free; Human bacteria

EDITORIAL SUMMARY

In this protocol a ligature is placed between mouse teeth. This induces gingival tissue inflammation and alveolar bone loss resulting in a mouse model of periodontitis.

TWEET

Mouse model of periodontitis established by placing ligature between mouse teeth.

COVER TEASER

Mouse model of periodontitis.

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal disease (PD) is a biofilm-induced inflammatory disease that affects the integrity of the tissues that surround and support the teeth1,2. Severe periodontitis is the 6th most prevalent disease worldwide, with an overall prevalence of 11.2% and 734 million people affected3. In the U.S. PD affects 47% of the adult population4,5. Periodontitis is a major cause of tooth loss in adults, having subsequent impact on the person’s masticatory dysfunction, quality of life and self-esteem6. In addition, periodontitis is associated with systemic diseases such as atherosclerosis, diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis7–9. While treatment of PD is successful in the majority of cases, up to 30% of patients with moderate chronic periodontitis respond poorly to treatment (such as refractory periodontitis)10,11. Further understanding of the pathogenesis of PD might enable improvements in treatment for patients.

The development of periodontitis can be broken down into discrete phases including the development of a pathogenic biofilm, stimulation/invasion by oral microorganisms and/or their derived products, induction of a destructive host response in gingival tissue, and breakdown of the supporting tissue and alveolar bone. Various animal models have been used to separately mimic the different phases of the pathogenesis and investigate the mechanisms of periodontitis in vivo12, 13, 14,15. Here we describe how to implement one of these models, the simplified ligature model, in mice.

Development of our ligature model

In the ligature model, a bacterial plaque retentive ligature is placed round the teeth to facilitate development of a dysbiotic oral microbiota and damage to gingival tissue. The ligature model is one of the widely used models to initiate experimental periodontal disease in different animals, including mice, rats, dogs and non-human primates16, 17, 18, 19. Application of the ligature model in mice has several advantages including the wide range of genetically engineered strains, the availability of high-quality immunochemical and cellular reagents, the low costs of small animals compared to larger animals and the wide availability of germ-free (GF) mice20–22, 23.

Ligatures do not induce significant inflammation and alveolar bone loss in germ-free rats and mice, demonstrating that the inflammation and bone loss sustained during the ligature model are dependent on ligature accumulation of bacteria24,25. Thus the ligature model is a suitable model to investigate the interaction between oral microorganism and host responses during the development of periodontitis. Despite this, the ligature induced periodontitis model has not been used frequently in mice. One of the potential reasons for this is the technical difficulty in placing the ligature around the teeth of the mice due to the small size of the murine oral cavity and teeth. Murine WT molars (M3-M1) have a size range of 0.4–1.2mm2, 26. The traditional ligature model requires placing a bacterial plaque retentive ligature around the maxillary second molar teeth (M2)16. This technique requires that the ligature be passed through 2 separate interdental spaces: the interproximal between the second and third molars (M2-M3) and the interproximal between the first and second molar (M1-M2)27,28. In our experience, the operating procedure for the traditional ligature placement in mice requires a very high level of technical skill and this is a potential challenge for many researchers.

We previously established a simpler ligature-induced periodontitis model to decrease the technical challenge of the ligature placement in the gingival tissue of mice28. In our simplified ligature model, a dual knotted 2.5mm silk ligature is placed between 2 murine molars to allow an endogenous microbiota accumulation that will initiate gingival tissue inflammation and periodontal bone loss. The ligature model described here dramatically decreases the technical challenge of placing a ligature between murine teeth because it utilizes a mouse dental bed and ligature holder to position and open the mouth of the mouse under isoflurane anesthesia and allow placement of the ligature correctly. The mouse dental bed and ligature holder are created by 3-D printing. The ligature can be installed in a short period of time without trauma to the murine periodontal tissues. Subsequent bone loss occurs only between the first (M1) and second (M2) molars. In a previous study we demonstrated that, similarly to the traditional ligature model, the simplified ligature model does not cause significant inflammation and alveolar bone loss in germ-free mice28 indicating that the inflammation as well as bone loss is mainly induced by the bacteria located in the ligature placement site rather than as a consequence of a ligature-associated trauma to the periodontal tissues. This method is technically simple and allows the exploration of multiple unaddressed questions in the field of periodontology that includes host responses, microorganism pathogenesis, periodontal repair and regeneration. In this protocol we describe how to set up this model.

Applications of the protocol

Insertion of the ligature initiates a host response that includes osteoclast activation, alveolar bone loss and gingival tissue inflammation. Obvious alveolar bone loss appears around day 6, and progressive bone absorption occurs from day 6 to day 12. This dynamic bone loss is consistent with that seen using the ligature model in which ligatures are placed around the molars16, 29.

Although application of the model in SPF mice can be used to evaluate the host response and change in expression of genes associated with periodontitis, because mice carry their endogenous bacteria and these are different from human oral microbiota it does not allow the exploration of human oral bacterial colonization, human oral bacteria-bacteria interactions and human oral bacteria-host interactions in vivo30. This limitation can be addressed by inserting ligature into GF mice and inoculating these mice with human oral bacteria. This enables this model to be used to study human bacteria colonization and induction of host responses in vivo, facilitating the in vivo study of interactions between human oral bacteria and host immunity.

This model may provide a useful tool for future studies to understand periodontitis mechanisms. Furthermore, by combining the model with GF mice and human bacteria inoculation, our model also provided a new avenue to investigate the complex human oral bacteria-bacteria, and bacteria-host interactions in periodontitis in vivo. This in vivo model might also be used as a preclinical model to test the potentiality of novel therapeutic compounds to treat periodontitis and evaluate potential regenerative therapies after experimental periodontitis is induced31.

Limitations of our Protocol

Our model can be used in SPF mice to test the roles of particular host responses and genes associated with periodontitis. Our model can be used in GF mice to study the underlying mechanisms of human oral bacteria colonization, human oral bacteria-bacteria interactions and human oral bacteria-host interplay in vivo. However, there are also several limitations, which should be considered when deciding whether to use the simplified ligature model:

As for the traditional ligature model, insertion of the ligature can potentially initiate minimal trauma of the murine gingival tissue during the installation of the ligature. Moreover, the ligature by itself allows rapid bacterial accumulation leading to microbiota dysbiosis. This step therefore does not mimic the majority of natural etiological factors responsible for microbiota dysbiosis during the development of human periodontitis. Thus, this model may not be suitable for the investigation of the pathophysiological factors that induce oral microorganism dysbiosis associated with periodontitis in humans.

Our simplified ligature model affects a smaller area of the periodontium than the traditional ligature model, which affects the entire surrounding of the tooth. Therefore, this simplified model may require a number of murine gingival tissues to be pooled if analysis that uses flow cytometry (FACS) to evaluate different immune cell populations is used. Related to this, development of bone loss using our model is not as rapid as that seen following when ligatures are installed using the traditional model (observed significantly at 6 days rather than after 3 days).

Active inflammation occurs mostly between the 1st and 2nd molars. We do not restrict collection of gingival tissue to the area of active inflammation because the area of active inflammation is very small. The amount of gingival tissue we harvest was chosen to be a set amount to increase the standardization and improve reproducibility of results obtained. The amount of gingival tissue to be collected can be adapted based on the question being asked and the technical skills of the operator.

Our data show that there is infiltration of Th1, Th2, Treg and Th17 cells by 9 and 18 days following establishment of our model. This allows exploration of the acquired immune responses. However these resuIts suggest that this model appears to provide an accelerated development of periodontal disease pathogenesis including both the early innate and late adaptive immune elements that characterize chronic periodontitis. However, it is possible that this model may not completely mimic the chronic properties of human chronic periodontitis.

Murine dental structures are not identical to human. While murine molars have cementoenamel junctions that enable attachment loss measurements, the structure of the mice periodontal apparatus is not completely the same as that of humans. Although the ligature aids in facilitating the bacterial adherence and colonization, some human oral microorganisms may not be able to colonize the murine oral cavity in GF mice.

Comparison with Other Mouse models of periodontitis

Several models are currently being utilized in the field to study periodontal disease pathogenesis, including oral gavage, airpouch/chamber, calvarial and ligature models. In the oral gavage model a human periodontal bacterium is inoculated orally. This model is often used to study murine experimental periodontitis. It has been reported that wild-type C57BL/6J mice are less susceptible to alveolar bone loss when subjected to the oral gavage model32,33. This reduces the possible applications of this model because wild-type C57BL/6J mice are one of the most common murine backgrounds for genetically engineered mice. An additional advantage of the ligature induced periodontitis model compared to the oral gavage model is that disease can be predictably initiated at a known time and significant host inflammatory responses and alveolar bone loss occurs in a defined location within a short period16. In addition, when compared to the oral gavage model, this simplified ligature model allows easy detection of gingival tissue inflammation and alveolar bone loss in histological sections. The amount of linear bone loss induced by the gavage model is minimal (0–0.03mm) when compared to the ligature model (0.1–0.2mm bone loss), which induces approximately 10 times more bone loss than the gavage model32,33.

The small differences observed between baseline measurements and following periodontitis induction in the gavage model can make it difficult to identify changes when testing different experimental conditions. Other mouse models to study periodontitis do not use the oral cavity to model periodontitis. These models include the airpouch/chamber model and calvarial14,34. In the airpouch/chamber models, bacteria are injected into an epithelium-lined pouch or coiled stainless steel wire34,35. The model is utilized to study periodontal pathogen virulence and inflammatory responses. It can also be utilized to study potential pharmacological agents. However, it does not allow analysis of gingival and periodontal host responses. In the calvarial model36 a stimulus is injected directly into the connective tissue overlying the calvarial bone in a small volume of carrier. The calvarial model has also been used for studying bone resorption and regeneration. It does not allow, however, analysis of oral microflora dysbiosis nor does it allow analysis of periodontal tissue inflammatory responses. The ligature model allows analysis of most aspects of periodontal disease, including bacterial interactions and dysbiosis, periodontal inflammatory responses and bone biology. Although all of these models have provided important information regarding the pathogenesis of periodontal disease, no model available thus far is suitable for studying all aspects of human periodontal disease.

Experimental Design

The main procedure describes how to establish our simplified ligature model in SPF mice, and also gives some examples of assays that can be carried out to assess gingival tissue inflammation, alveolar bone loss and ligature associated microbiota. These assays can be used to assess the effects of ligature placement in mice for different amounts of time. We also provide a modified version of the procedure that describes how to inoculate GF mice with specific human bacteria in Box 1.

Box 1: Procedure to be used on Germ free (GF) mice (Timing: 10–15 days).

Specific materials required for GF mice

GF Mice aged 8–12 weeks.

Here we describe results from the use of 10–11 week old Germ-free (GF) female C57BL/6 mice (obtained from GF mice centers in University of Michigan and University of North Carolina Germ-Free & Gnotobiotic Mouse Facilities) CAUTION: All GF mouse experiments should conform to the institutional and national guidelines. Our GF mouse procedure was approved by University of Michigan and University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee.

BBL Trypticase Soy Agar (TSA) 10% plates supplemented with with 5 μg/ml Hemin and 0.5 μg/ml Vitamin K.

Add liquid Hemin (25μg) and Vitamin K (2.5μg) onto commercial plates purchased from BD (221239), and spread evenly using a sterile glass spreader. Place plates inside an anaerobic chamber to drive off the dissolved oxygen for 24 hours (anaerobic pre-reduction). The commercial plates (BD, 221239) could be stored in 2–8°C for over 3 months according to manufacture guideline. Hemin and Vitamin K should be freshly added on the plate before human bacteria culturing.

Trypticase soy Broth (TSB) supplemented with 5 μg/ml hemin and 0.5 μg/ml Vitamin K.

Suspend Trypticase soy in demineralized water as described in the guidelines from the manufacturer and warm slightly to dissolve completely. Dispense the medium into appropriate containers and autoclave to sterilize at 121 °C for 15minutes. Allow sterilized TSB to cool down and could store at 4°C over 3 months before using. Freshly add Hemin and Vitamin K to reach the appropriate concentration (5 μg/ml and 0.5 μg/ml of Hemin and Vitamin K respectively) before human bacteria culturing.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE):

Surgical Cap, Mask, Sterile Surgical Gown and Gloves. CRITICAL this must be put on before approaching the biological cabinet and worn at all times by GF staff.

Class II biological cabinet CRITICAL

This cabinet must be maintained as the working station throughout the experiment with all of the procedures performed in the cabinet.

Bacterial Cultivation for Human Bacterial Infection-Ligature Model (Timing: 3–4 days)

CRITICAL This section only needs to be carried out if GF mice are going to be inoculated with exogenous human bacteria.

-

1

Separately inoculate Streptococcus gordonii (ATCC 10558), Fusobacterium nucleatum sp. nucleatum (ATCC 25586), and Veillonella parvula (ATCC10790) on different TSA blood agar plates for culturing at 37°C in anaerobic chamber. Visible colonies of Streptococcus gordonii (ATCC 10558) could be observed on the plate after overnight culturing. Fusobacterium nucleatum sp. nucleatum (ATCC 25586), and Veillonella parvula (ATCC10790) needs 3–7 days culturing to obtain visible colonies.

-

2

Pick one bacterial colony from the plate of each type of bacteria and separately inoculate into the Trypticase soy Broth (TSB) supplemented with 5 μg/ml hemin and 0.5 μg/ml Vitamin K to obtain a liquid culture of individual bacteria.

-

3

Measure optical density (OD) on day of inoculation using a Spectrophotometer (optical density at 600 nm [OD600]).

-

4

Culture the liquid cultures of bacteria for 24–48 hours at 37°C in anaerobic conditions. Whilst you are growing up sufficient bacteria, proceed with collection of feces samples and placement of ligature as described in steps 8–11 below. The experiment should be timed such that sufficient bacteria is available for inoculation in step 10. Check the bacterial density daily. Sufficient bacteria is present for infection once the OD reach 0.5 for these three bacteria. CAUTION: Different bacteria might have distinct growth curves, the optimal OD may need to be varied depending on the bacteria used and the infection procedure.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Day 0 TIMING (2–3 hours)

-

5

Transfer WT C57BL/6 GF mice from plastic mice isolator into class II biological cabinet. CRITICAL This must be done by GF staff Critical: Mice must be kept in the cabinet to isolate them from the environment and to avoid contamination throughout the experiment.

-

6

Collect feces samples from the GF mice and suspend the feces in 500μl sterile PBS by vigorously vortexing. Spread 50μl feces sample suspended in PBS on TSA-blood agar plates using a sterilized glass spreader. Culture plates in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions at 37°C for 24h to confirm the GF condition of these mice. We strongly suggest that the researchers do not wait for the results of the culture; proceed in parallel with the next step as this could save 1 day for the GF mice procedure. If the mice are still GF, no bacteria will grow up on the plates in both aerobic and anaerobic condition overnight. If microorganisms grow up on the plates, it indicates the GF mice are contaminated; and the experiment should be terminated in Step 9 below.

-

7

Anesthetize GF mice using isoflurane under sterile condition (isoflurane vaporizer + oxygen are filtered by 0.2um air filter) as described in steps 3–6 of the main procedure but following the additional precautions described here to ensure sterile conditions. All of the tools for ligature placement must have been sterilized by gas sterilization and should be delivered into the cabinet with the assistance of a laboratory colleague following surgical techniques. Critical: Air filter must be used for anesthesia to protect the mice from air associated microbiota contamination. All of the tools need to be sterilized before transferring into the biological cabinet. Alternatively, mice can be anesthetized by injection with sterile Ketamine/Xylazine however if this method is used the mice take longer (~30min) to recover from anesthesia.

-

8

Place the ligature between the molars as described in steps 7–12 of the main procedure, but with the mice in a biological cabinet and using sterile technique.

Keep mice in biological cabinet under working condition for one day.

Day 1 TIMING (3–4 hours)

-

9

Collect feces samples again from GF mice after the ligature placement (as described in step 9) to confirm that the mice are still germ free by culturing the feces in both aerobic and anaerobic condition. Critical: It is necessary to confirm the GF condition of the mice before and after ligature placement because the mice should be absolutely GF before starting human bacterial infection. These two confirmations monitor whether there is contamination occurring during the GF mice transfer and ligature placement steps. The downstream experiment should be terminated if contamination occurs during GF mice transferring and ligature placement.

-

10Inoculate mice with 1X108 CFU of the bacteria of choice in sterile PBS using a sterile syringe in the biological cabinet. An example of the types and combinations of bacteria that can be used is given below:

Group Day1 Day2 Single Infection S. gordonii F. nucleatum V. parvula Double Infection S. gordonii F. nucleatum (F. nucleatum to be introduced 1-day after S. gordonii colonization) S. gordonii V. parvula (V. parvula to be introduced 1-day after S. gordonii colonization) Triple Infection S. gordonii F. nucleatum + V. parvula(F. nucleatum and V. parvula to be introduced 1-day after S. gordonii colonization) Keep mice in biological cabinet under working condition for one more day.

Day 2 TIMING (30min-1 hour)

-

11

If required, inoculate mice with a second bacteria 24h later. Leave ligature in place for an additional 9 days after inoculation with the first bacterium (8 days following final inoculation if two bacteria are used)

Continuously keep mice in biological cabinet under working condition before ending the experiment at day 10.

Day 10 TIMING (3–4 hours)

-

12

Anesthetize gnotobiotic mice using isoflurane under sterile conditions.

-

13

Collect Ligatures with sterile forceps as describe step 10 of the main procedure and immediately put in 200μl reduced sterile PBS (reduced sterile PBS is sterile PBS that has been stored inside the anaerobic chamber overnight to drive off the dissolved oxygen).

-

14

Vortex to disperse the bacteria associated with the ligature into the PBS evenly.

-

15

Serially dilute 20μl of the ligature-PBS solution (10, 102, 103 and 104 times) using sterile PBS and spread 100 μl on TSA-blood agar plates.

-

16

Culture the bacterial plates in an anaerobic chamber for 3–5 days.

-

17

Count the bacteria grown on the plates according to the colony morphology for S. gordonii, F. nucleatum and V. parvula (an example of a typical plate showing the morphologies of these colonies is shown in Supplementary Figure1). Besides morphology, bacteria colonies can also be confirmed by 16s rDNA (16srRNA gene) sequencing using bacteria consensus primers as described in our previous work28.

-

18

Anesthetized mice are euthanized by CO2; and collect maxilla for MicroCT Scan and histology as described in steps 14–19 of the main procedure.

Mice age and strain selection.

We have found that the teeth of mice aged 8–12 weeks provide ideal conditions for both SPF and GF procedures. If the mice are younger than 8 weeks there is an increased rate of ligature loss during the experiment. In contrast, if the mice are older than 12 weeks, it can be difficult to push the ligature between the interproximal molars. Although the illustrative data we provide here is from female mice, used as cohousing of female mice is feasible, we have previously demonstrated that both genders of mice are able to be used in our model. Mouse stains should be selected based on the goal of the experiment. C57BL/6 mice are used in the example applications demonstrated for our protocol here as there are a large number of gene knockout strains based on this mouse background.

Establishment of appropriate sample sizes for experimental groups.

When designing an experiment using our simplified model, statistical Power Calculation should be performed based on the data presented here and in our previous study28 to decide on group sizes. For example, in our GF mice study, we estimate the mouse number by power calculation for alveolar bone loss in 10 days ligature placement. According to our data, the mean bone loss is 0.258mm in control group and 0.49mm in ligature group. The standard deviation in the ligature group is 0.08. Power (1-β) =0.80 and Type I error rate=5%. The sample size (n) was calculated to be 3. Notably, this is based on there being no loss of the ligature during the experiment. We suggest that a researcher new to this model should consider allowing for a 20% ligature loss rate during experiment. The sample size for the experiment should thus increase 20% building on the rough estimation from the power calculation.

Control experiments in GF mice.

Although previous studies have shown that ligature alone does not induce significant inflammation and alveolar bone loss in GF mice25,28, we recommend users include this control group when establishing experimental groups. This control provides an indicator of the baseline of gingival tissue inflammation and alveolar bone loss in the researcher’s GF facility. The ligature collected from this control group should also be cultured on the plate to confirm that there are no bacteria growing at the endpoint of the experiment. Box 1 describes how to adapt the procedure for use with GF mice.

Monitoring and circumvention of environmental microorganism contamination in GF mice.

To avoid the contamination of environmental microorganisms during the GF mouse experiment, surgical sterile techniques must be used while performing the experiment. All of the tools used in the GF experiment must be sterilized and delivered into the biological cabinet without exposure to the environment. It is important to note that the isoflurane gas used for GF mice anesthesia must be filtered using a 0.2μl filter to exclude microorganisms from the air. The mice must be kept in the cabinet throughout the experiment. In addition, we suggest collection of faeces samples before and after ligature installation to monitor that the mice are germ free. By following our precautions, the faeces should show no bacterial growth on the plates after culturing in both aerobic and anaerobic condition.

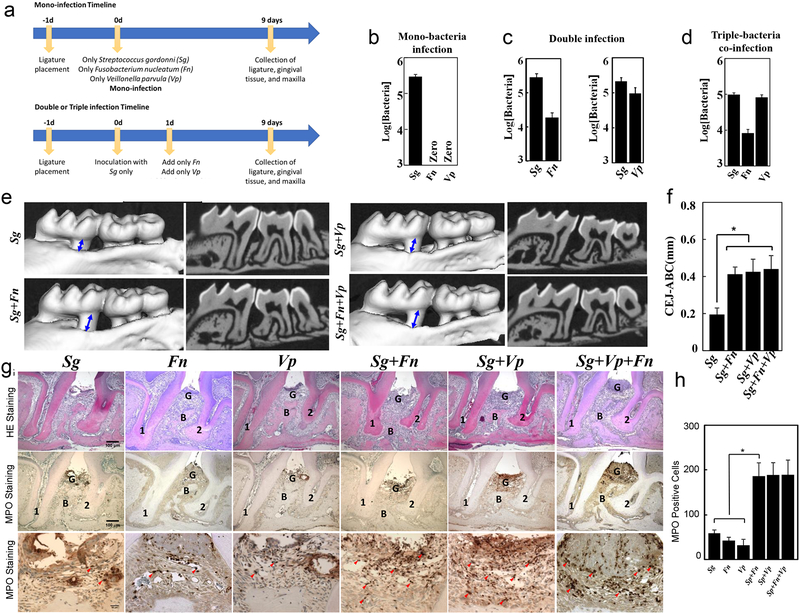

Human Bacterial Co-infection model.

Streptococcus gordonii (S. gordonii, Sg) is the pioneer colonizer of the surface of the teeth37. Veillonella parvula (V.parvula, Vp) is an early colonizer and Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum, Fn) is considered as a bridge bacteria of dental plaque38. Both F. nucleatum and V.parvula have been reported to be tightly associated with periodontal diseases39,40. Although the interspecies communication in S. gordonii - F. nucleatum, S.gordonii-V.parvula have been extensively studied in vitro41,42,43, their co-aggregation in vivo has not been explored. Therefore, we have utilized the above three human bacteria in our model by co-infecting human bacteria into GF mice to obtain a proof of concept that our model is practical to study human bacteria colonization and interaction in vivo. We expect more complicated human polymicrobial infection could be established using our model. Notably, GF mice rather than SFP mice have to be used in human bacterial co-infection because the endogenous microbiota of SFP impacts the long term human bacterial colonization in the oral cavity of mice.

MATERIALS

Reagents

Mice aged 8–12 weeks. Here we describe results from the use of 10–11 weeks old; WT specific pathogen-free (SPF) female C57BL/6 mice (purchased from Taconic Farms) CAUTION: All SPF mouse experiments should conform to institutional and national guidelines. Our SPF mice procedure was approved by the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee

- Human Bacterial Culture

- BBL Trypticase soy agar (TSA) 10% sheep blood plates (Becton, Dickinson, and Company, BD 221239,)

- BBL Trypticase soy Broth (TSB) (Becton, Dickinson, and Company, BD 211768)

- Anaerobic gas mix (80% N2; 10% H2; 10% CO2)

- Hemin (Sigma-Aldrich, 51280)

- Vitamin K (menadione, Sigma-Aldrich, 58-27-5) CAUTION: Personal Protective Equipment: Gloves, Dust mask and eyeshield. Acute toxicity through oral, dermal and inhalation.

- Streptococcus gordonii (ATCC 10558)

- Fusobacterium nucleatum sp. nucleatum (ATCC 25586)

- Veillonella parvula (ATCC 10790)

- Disinfectant

- Vimoba 128 (Quip Labs, VM128)

- For Use During Procedure

- Isoflurane and oxygen (inhalational anesthetic through isoflurane vaporizer); CAUTION: Perform procedure in a well-ventilated hood to avoid isoflurane exposure which can cause dizziness and headaches

- Puralube vet ointment (Butler Schein Animal Health, NC0138063)

- For Sample Collection

- RNALater (Ambion, AM7021)

- Formalin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, SF100–4) CAUTION: Use personal protective equipment and only perform under a chemical fume hood. Harmful (Irritating to eyes, respiratory system and skin, cancer hazard) if absorbed through skin or if inhaled through respiratory system.

- 80% Ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, E7023)

- Sterile PBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 14190144)

- For Sample Processing/Analysis

- 10% EDTA+1%Formalin (pH 8.0) Critical: The prepared EDTA + Formalin solution can be stored at 4 °C for up to 1 week for decalcification.

- Paraffin (Leica Microsystems™ 39601006. Catalog No.23-021-750)

- H/E staining: Hematoxylin (ThermoFisher Scientific. Catalog No. 6765001) and Eosin (ThermoFisher Scientific. Catalog No. 6766007)

- MPO antibody (R&D, AF3667) and Anti-Goat HRP-DAB Cell & Tissue staining kit (R&D, CTS008)

- Fisher Chemical™ Permount™ Mounting Medium (Fisher Scientific SP15–500)

- TRAP staining kit (Sigma-Aldrich, 387A-1KT)

- Liquid nitrogen CAUTION: Wear gloves and safety glasses when transferring liquid nitrogen. Liquid nitrogen is extremely cold to cause severe frost bite. Use only approved unsealed containers and never seal it in any container to avoid explode.

- All Prep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, 80204)

- QIAShredder (Qiagen, 79654)

- SuperScript VILO Mastermix (ThermoFisher, 11755050)

- RT2 ROX SYBR Green qPCR Mastermix (Qiagen, 330520)

- RT2 Profiler PCR Array (Qiagen, PAMM-052ZC)

Equipment

- Sterilization

- Steam Sterilizer (Getinge, 400/500LS-E Series)

- Preparation/Processing of Mouse Dental Bed and Ligature Holder

- Lulzbot mini v1.0 3D printer (Aleph Objects)

- 3.0 mm polylactic acid (PLA) filament (Prototype Supply)

- Wire cutters (Xcelite, 41-4-12200)

- Needle-nose pliers (Xcelite, 2411P-12200)

- Scalpel handle #3 with 15C blade (Bard-Parker, 371030; Integra, 4–315C)

- Thin rubber bands

- 1-inch screw (Home Depot, 803041)

- For Bacteria Cultivation

- Culture tubes (Pyrex, CLS9944518)

- Bacterial loop (Evergreen, 333–5010-Y10)

- Bunsen burner (Hanau, Touch-O-Matic)

- Anaerobic chamber (ThermoFisher Scientific, Forma Anaerobic System)

- Spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, SpectraMax M2)

- For Use During installation of ligature

- Isoflurane vaporizer with connecting hose and sealed container (Eagle Eye Anesthesia, Inc., Model 150)

- Flexible-arm dissection light (Schott-Fostec, LLC.)

- Forceps (Fisher, 16-100-113)

- Mouse Dental Bed

- Ligature Holder

- Dental Explorer (Hu-Friedy, EXD11/12A6)

- Sterilized silk sutures (Roboz Surgical Instrument, SUT-15–1, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) Critical: We have only used this type of suture for the ligature model as it is able to accumulate bacteria. Additional pilot experiments might be necessary if other commercial sutures are used.

- Scissors (Sklar, 23–1102)

- Heat lamp (UNC Animal Facility)

- Sterile cage for recovery (UNC Animal Facility)

- For Use During Sample Collection

- CO2 chamber (UNC Animal Facility)

- Mouse Dental Bed

- Fine point forceps (Fisher, 16-100-113)

- Scalpel handle #3 (Bard-Parker, 371030)

- 15C scalpel blades (Integra, 4–315C)

- 1.7 mL microcentrifuge tubes (VWR, 87003–294)

- Dry ice

- Ice

- For Sample Processing/Analysis

- Slides and coverslips (Fisher Scientific, 12-544-2; Fisher Scientific, 12-545-87)

- Upright wide-field microscope (Olympus, BX61)

- StepOnePlus qPCR machine (Applied Biosystems, StepOnePlus)

- SCANCO μCT 40 scanner (SCANCO)

- NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, ND-1000)

- Software

- MicroView Standard software (Parallax Innovations, 2.5.0–3139)

- GraphPad Prism software version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA)

- RT2 profiler web-based analysis program (SABiosciences, http://pcrdataanalysis.sabiosciences.com/pcr/arrayanalysis.php)

Equipment Setup

- Printing and Assembly of the Murine Dental Bed and Ligature Holder by 3D Printing Technique (Timing: 1–2 days)

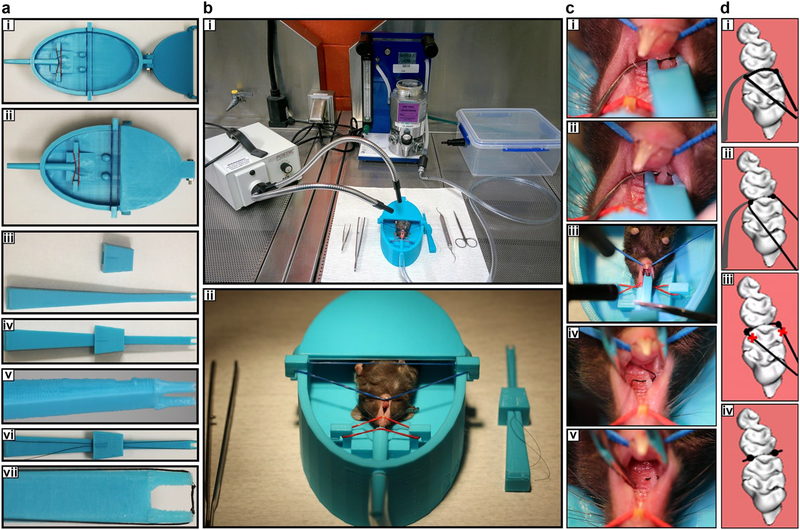

- Print Mouse Dental Bed (Figure 1a–b) and Ligature Holder (Figure 1c–g) using standard print quality on a Lulzbot mini v1.0 3D printer (Aleph Objects) using 3.0 mm polylactic acid (PLA) filament (Prototype Supply). A detailed blue print with specific information of the mouse dental bed and ligature holder is included in Supplementary Figure 2. These materials can also be obtained at a nonprofit cost by contacting the authors.

- After printing is complete, cut off supporting material using wire cutters/needle-nose pliers/etc. and if necessary, use a scalpel blade to deepen the groove on Ligature Holder to ensure the suture thread will be held in place

- Connect the Dental Bed top to the Mouse Dental Bed with a 1-inch screw (Home Depot model# 803041)

- Place rubber bands around hooks on the Mouse Dental Bed (adjust tension as necessary during procedure) (Figure a-b)

Figure 1. Tools and technical procedures required to set up the simplified ligature model in mice.

(a-h) The tools required. (a,b) Mouse dental bed. b represents high magnification of a. (c-e): U-tipped Ligature holder (U shape for holding silk). e represents high magnification of c and d. (f,g) The U-tipped holder with 5–0 silk suture containing two knots in the inside of the forceps tips (about 2.5 mm distance between knots). g represents high magnification of f (h) Experimental set up immediately prior to anesthetizing the mouse with isoflurane. The stages required to insert the ligature are shown as photos (I,k,m,o) and diagrammatically (j, l, n, p). The left hand is used to hold the dental explorer whilst the tip of the dental explorer and the 2.5 mm silk between knobs are carefully located in the gap between the 1st and 2nd molar using the U-tipped Ligature holder held in the right hand (I,j). The suture is then pushed through the interdentium between first molar and second molar (k-l). The silk is cut and the U-tipped forceps removed (m,n). Finally the silk is cut at the end of the knot (o,p). Appropriate institutional regulatory board permission was obtained to carry out the experimental procedure on the mouse shown here.

PROCEDURE

Acclimatization of Animals (Timing: Variable)

-

1

If mice are new to the animal facility, acclimatize them in pathogen-free conditions with a controlled room environment for at least 7 days, and during this time continue with step 2.

-

2

Randomly allocate mice to the groups required for the experiment. For example for a time course of 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15 and 18-day ligature placement, divide into 7 groups with 5 mice/group.

Preparation for the ligature placement (Timing: 2–10 minutes/mouse)

-

3

Connect isoflurane vaporizer + oxygen to a sealed container to enable easy transfer of the anesthetic mice from container to the Mouse Dental Bed.

Place flexible-arm dissection light appropriately near the front of the Mouse Dental Bed (Figure 1h). Ensure work bench is sterile. CRITICAL: The work-bench should be cleaned in a well-ventilated area (such as a fume hood) using Vimoba 128 (Quip Labs) and materials placed on a sterile surface

-

4

Weigh mouse and place into a sealed container with 4% isoflurane flow. Monitor the heart rate to determine the level of anesthesia (confirm that the mouse is properly anesthetized by pinching the toe; there should be no response). During this proceed with the next step.

-

5

Whilst the mouse is becoming fully anesthetized (3–5 minutes), prepare the sterile silk suture ligature by cutting a 7–10 inch length of silk thread and tying 2 knots in the center (~2.5 mm apart from each other). Thread silk ligature over the grooves on the Ligature Holder (hold thread in place by using slide lock piece of the Ligature Holder), ensuring that both knots are positioned inside the tips of the ligature holder (Figure 1d–g).

CRITICAL It is important the silk ligature is placed in the ligature holder correctly to facilitate the later placement of the ligature around the teeth.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

6

Once the mouse is fully anesthetized, remove from sealed container and apply Puralube vet ointment to the eyes. Quickly transfer mouse to the Mouse Dental Bed (with the back of the mouse resting on the bed), and transfer isoflurane flow to nozzle attached to the bed using 1.5–2.5% flow to maintain the level of anesthesia.

Placement of the simplified ligature (Timing: 1–2 minutes/mouse)

-

7

Prop open the mouth of the mouse using rubber bands, adjusting tension as necessary to prevent one arch from pulling more than the other arch. Hold dental explorer in your left hand and position the tip of the explorer in the interdental contact between the 1st and 2nd right maxillary molars (M1 and M2), aligning the explorer horizontally and placing gentle force between teeth (Figure 1i). Placing the explorer in this horizontal position pressing against the palate with the fulcrum in the interdental space also stabilizes the head of the mouse for easier ligature placement.

-

8

Hold Ligature Holder in right hand and place silk suture ligature on the coronal surface of the 1st and 2nd molar (M1-M2) interdental contact (Figure 1i).

-

9

Apply a gentle force in the interdental region using dental explorer by the left hand to create a temporary space for the ligature placement. Whilst doing this use slight force and a wiggling motion of the ligature holder by the right hand to place the ligature between the molars (Figure 1k); CRITICAL: do not use too much force as this may cause palatal tissue damage.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

10

Once ligature is in place (Figure 1m), cut the thread in a place away from the knots to free the ligature holder first. Then, use fine-point forceps to grasp the silk thread and cut the thread as close as possible to the knots (Figure 1o). CRITICAL The thread should be cut as near the knots as possible to prevent ligature loss.

-

11

Remove mouse from bed and tag as desired.

-

12

Place mouse into sterile cage with heat lamp and monitor until fully recovered from anesthesia.

-

13

After recovering from anesthesia, move the mice from the surgical room into the housing room and house under SPF conditions for the desired amount of time to induce a periodontitis phenotype.

Downstream assays on live mice following ligature placement (Timing: variable, as dependent on the hypothesis being tested. Typically 0–18 days)

Euthanasia and Sample Collection (Timing: 10–20 minutes)

-

14

Euthanize each animal according to your approved method. We euthanize each mouse individually in a carbon dioxide chamber (5–7 minutes) and ensure animals are dead using a secondary method such as cervical dislocation.

-

15

Place mouse in the Mouse Dental Bed as described in step 7, and use fine-point forceps to remove the ligature by grasping the end of the knot; some force may be needed to pull the ligature out, but try to prevent breakage. Place the collected ligatures in an Eppendorf tube and store at −80°C for potential microbiota analysis. CRITICAL: Based on our experience, the suture is very stable between molars even at 18 days after installation. If our guidelines are followed, more than 80% of the sutures can be collected at the endpoint of the experiment. Mice should be excluded from alveolar bone loss and histology analysis if the ligature fell off before the endpoint of the experiment.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

16

Use a 15C scalpel blade to make a shallow incision around all three molars for gingival tissue collection; CRITICAL: do not cut too deep as this may cause maxilla to break.

-

17

Use fine-point forceps to remove the gingival tissue and place in RNALater at 4°C.

-

18

Collect maxilla and place in formalin for fixation (avoiding breakage of sample).

-

19

Leave the maxilla in formalin for 24 hours at 4°C; then remove formalin and store in 80% ethanol at 4°C prior to further alveolar bone loss assessment and histological processing? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

20

Leave the gingival tissue from step 17 in the RNALater at 4°C for 24 hours; then centrifuge at 5000g in 4°C for 5 min, remove RNALater, and store at −80°C for further analysis.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

PAUSEPOINT The ligatures can be stored at −80°C for long term over 1 year. The gingival tissue can also be stored at −80°C for long term over 1 year. The maxilla can be stored at 4°C in formalin for 24 hours (over 24 hours fixation in formalin may impact the histological staining procedure) and stored in 80% ethanol at 4°C for long term (1–2 years). Although these samples could be stored at proper condition for long term, we recommend that the samples should be processed to next step once they are ready.

Sample Analyses (Timing: Variable)

CRITICAL Samples should be blinded so that researchers analyzing the data do not know which experimental group the samples came from. We use a double blinded design during MicroCT and histology analysis to exclude potential subjective variation.

-

21Proceed to further analysis of samples as required by your experiment. Examples of methods that can be used to analyze samples include assessment of alveolar bone-loss (option a), histological analysis (option b) and gene expression analysis of gingivial tissue (option c).

- Alveolar Bone-Loss assessment by micro CT analysis (linear or volumetric analysis).

- Scan formalin-fixed maxillae with a SCANCO μCT 40 scanner with 18 μm resolution in all 3 spatial planes.

- Import scanned files into MicroView Standard software (Parallax Innovations, 2.5.0–3139).

- Measure the distance between the cementoenamel junction and alveolar bone crest (CEJ-ABC) for the distalbuccal root of first molars in three-dimensional images viewed from the buccal sides as described previously28.

-

Repeat measurements twice per site, and obtain mean distances in millimeters.? TROUBLESHOOTING

- Histological Analysis

- Decalcify fixed maxillae in a solution of 10% EDTA (pH 8.0) for 1 week at 4°C (changing the EDTA solution twice during this time).

- Embed tissue in paraffin with the buccal side of the tooth facing towards the bottom of the micro mold, and the long axis of the teeth paralleling the short side of the cassette. CRITICAL: embedding the samples consistently in our recommended orientation is crucial to obtain similar structures for histological section.

- Slice 5mm thick serial sections in the sagittal direction along the long axis of the teeth, and mount them on slides.

- Myeloperoxidase (MPO) staining. Deparaffinize sections in Xylene and hydrate by moving through a gradient of ethanol concentrations (100%, 95%, 80%, 70% and 50% ethanol and distilled water) in 2 changes for 5 minutes each.

- Retrieve antigens by digesting with proteinase K (working concentration: 20μg/ml) at 37°C for 10minutes followed by cooling at room temperature for 10minutes.

- Rinse the sections in PBS for 5minutes twice.

- Block the sections using Peroxidase, Serum, Avidin and Biotin blocking reagents provided by the manufactory Anti-Goat HRP-DAB Cell & Tissue staining kit (CTS008, R&D). In brief, cover sample with 1–3 drops of the Peroxidase Blocking Reagent for 5 minutes and rinse slides with PBS for 5 minutes. Incubate sample with 1 – 3 drops of Serum Blocking Reagent D for 15 minutes, drain slides and carefully wipe off excess Serum Blocking Reagent (do not rinse with PBS). Then, incubate sample with 1 – 3 drops of Avidin Blocking Reagent for 15 minutes and rinse slides with PBS for 5 minutes. Incubate sample with 1–3 drops of Biotin Blocking Reagent for 15 minutes and rinse with PBS for 5 minutes before the next step.

- Incubate the sections with anti-MPO primary antibody (AF3667, R&D; 10μg/ml in 5%BSA) at 4 °C overnight.

- Rinse the sections with PBST (PBS+0.5‰Tween-20) for 15 minutes, 3 times.

- Incubate with Biotinylated Secondary Antibody, HSS-HRP and DAB chromogen provided by the manufactory staining kit (CTS008, R&D). Incubate sample with 1 – 3 drops of Biotinylated Secondary Antibody for 30 – 60 minutes and Rinse the sections with PBST (PBS+0.5‰Tween-20) for 15 minutes, 3 times. Incubate sample with 1 – 3 drops of HSS-HRP for 30 minutes and rinse three times with PBS for 2 minutes/wash. Add 1 – 3 drops of freshly prepared DAB Chromogen solution to cover the entire sample and incubate for 1 – 10 minutes. Monitor intensity of staining under a microscope to ensure proper intensity of tissue staining. Rinse with distilled water for 5 minutes.

- Counterstain sections with hematoxylin for 30sec and rinse slides 5 minutes with running tap.

- Dehydrate samples by reversible gradient ethanol and xylene (distilled water, 50%, 70%, 80%, 95%, 100% ethanol and xylene) in 2 changes for 5 minutes each.

- Mount the sections using Permount Mounting Medium and dry overnight in the hood.

- Image the sections. We use an Olympus BX61 upright wide-field microscope.

- Count MPO positive cells in the gingival tissues coronally to the alveolar bone crest in the interproximal region of the distal root of the first molar (M1) and the mesial root of the second molar (M2) in each slide.

- Take spare slides from step iii and stain with the TRAP staining kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) using the manufacturer’s instructions, and counter-stain with hematoxylin

- Count TRAP-positive cells as osteoclasts in an area located on the buccal alveolar bone of the maxillary first molar in each section.

- Gene expression analysis of Gingival Tissue using the RT2 ROX SYBR Green qPCR Mastermix and RT2 Profiler PCR Array (PAMM-052ZC, Qiagen)

- To isolate RNA, first crush gingival tissue samples using liquid nitrogen

- Homogenize sample using QIAShredder (79654, Qiagen)

- Use an All Prep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (80204, Qiagen) to isolate RNA following the manufacturer’s instructions.

- Pool together isolated RNA samples for all specimens in one group and measure RNA optical density (OD) using NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies)

- Prepare 200 μL cDNA using SuperScript VILO Mastermix (11755050, ThermoFisher) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

- Perform qRT-PCR using an RT2 Profiler PCR Array (PAMM-052ZC, Qiagen) on StepOnePlus qPCR maching (Applied Biosystems) to determine gene expression

- Use RT2 profiler web-based analysis program (SABiosciences, http://saweb2.sabiosciences.com/pcr/arrayanalysis.php) for gene expression analysis

Data Analysis (Timing: Variable)

-

22

Carry out appropropriate statistical tests. For example, for the multiple comparisons of alveolar bone loss, neutrophil numbers and bacterial numbers, ANOVA (parametric) can be used followed by the Bonferroni test as a post hoc test. We perform statistical analyses using GraphPad Prism software version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Adjustment for multiple comparisons can be done, for example by Bonferroni, with p<0.05 considered statistically significant. For mRNA expression analysis, statistical analysis can be performed using signed-rank test (SAS software). A 1.5 fold difference can be used when evaluating PRRs, Chemokine and Adaptive Immunity-Associated Genes, as recommended previously44. However, due to the high fold changes between control and ligature groups observed for Innate Immunity-Associated Genes, we increase the threshold and utilize a 4-fold difference to define more dramatic differences. Consider p<0.05 for significance.

TIMING

All timings listed below associated with handling animals are for 1 animal.

Main procedure - Application of the protocol in Specific Pathogen Free (SPF) mice (total timing 10–25 days)

Steps 1–2, animals and acclimation: Dependent on the age of animals and whether acclimation is required due to transfer of animals from another facility

Steps 3, setup of surgical procedure area: 5 minutes

Step 4, anesthetizing the animal: 3–5 minutes (closely monitor heart rate to determine level of anesthesia)

Step 5, preparation of sterile silk ligature: 2 minutes

Step 6, transfer of mouse to dental bed: 30 seconds

Steps 7–9, placement of ligature: 1–2 minutes

Steps 10, removal of extra thread: 30 seconds

Steps 11–12, tagging of mouse and recovery: 3–5 minutes

Step 13, for a time course of the effects of of the ligature model: 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, or 18 days depending on desired timepoints

Step 14, euthanasia: 5–7 minutes

Step 15, collection of ligature: 1 minute

Steps 16–17, collection of gingival tissue: 2 minutes collecting + 24 hours in RNALater before removing

Step 18–19, collection of maxilla: 3–5 minutes collecting + 24 hours in formalin fixation before switching to ethanol

Step 21 a i-ii, microCT scan: 2–4 hours

Step 21 a iii-iv, bone loss linear measurements: 10–20 minutes

Step 21 b i, decalcification of sample: 1 week

Step 21 b ii-xvii, preparation of slides and staining: 3–5 days

Step 21 c i-iv, isolation of RNA: 1 hour

Step 21 c v, reverse transcription: 2 hours

Step 21 c vi, qRT-PCR: 2.5–3 hours

Step 21 c vii, qRT-PCR analysis: variable depending on depth of analysis and number of experimental groups

GF mice Specific Procedure (Box 1)

Reagent setup: preparation of TSA broth and blood agar plates: 4–6 hours plus 24 hours pre-reduction of plates in anaerobic conditions

Steps 1–4, anaerobic culture of bacteria: 24–72 hours

Step 3, measurement of OD: 1–2 minutes

Step 5, transfer GF mice and PPE 10–20min

Step 6, collect feces samples to confirm the GF condition of the mice after transferring 1min/mouse

Steps 7–8, GF mice anesthesia and ligature installation 3–5min/mouse

Step 9, collect feces samples to confirm the GF condition of the mice after ligature placement 1min/mouse

Step 10, human bacteria inoculation 1min/mouse

Step 10–11, human bacterial infection ligature model: 10 days

Steps 12–13, gnotobiotic mice anesthesia and ligature collection 2–3min/mouse

Steps 14–17, ligature associated bacteria plating and quantification 10min/ligature

Step 18, bacterial colony counting: 24–72 hours depending on rate of growth of bacteria

TROUBLESHOOTING

See Table 1 for troubleshooting guidance.

Table 1:

Troubleshooting

| Step | Problem | Possible Reason | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Knots on thread are too far apart | Movement of knot while tightening it | Use the dental explorer to move knots to the correct location 2.5 mm apart |

| 7–9 | Difficulty inserting ligature between molars. Damage to palate. | Silk thread is not taut and is, therefore, bending with pressure rather than being pushed into place; this causes the ligature holder to press against the palate and cause damage. | Utilize gentle pressure with explorer to fixate the head of the mouse and separate teeth at the same time. Redo locking mechanism on the Ligature holder to ensure silk ligature is as taut as it can be; may also require tying new knots if the flexion is due to the distance between the knots; should not need much force to place ligature, as this can cause palatal damage |

| 15 | Breakage of ligature during removal | Depending on time point, there may not be much bone loss which can make it more difficult to remove a tightly placed ligature | Grasp knot on ligature and pull up rather than from the side to remove ligature |

| 16–17 | Gingival tissue rips during removal | Incisions do not meet on all sides | Create the lingual incision first, then the two horizontal incisions above the third molar and below the first molar, and finally create the buccal incision around the molars; this will help extract the gingival tissue as one intact piece |

| 18 | Maxilla breaks during collection | There may already be a score in the bone from collection of gingival tissue, creating a weak point where it is more prone to break | Try to keep incisions for gingival tissue as shallow as possible while still being deep enough to remove the tissue in one piece; maxilla can be sectioned in half intentionally to prevent breakage elsewhere,. |

| 21c vii | No data detected in RT2 Profile | Reverse transcription may have been unsuccessful | Run a PCR (for GAPDH or other housekeeping gene) using cDNA synthesis reaction to confirm proper reverse transcription before proceeding to RT2 Profiler PCR Array |

| Box 1 steps 1–4 | Contamination of bacterial culture | Contaminated medium or improper technique | Ensure proper sterilization of medium as recommended by manufacturer, and work near flame hood to prevent contamination |

ANTICIPATED RESULTS

Time course characterization of alveolar bone loss and osteoclast activation in the simplified ligature model

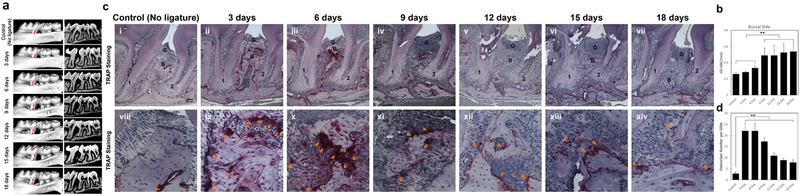

A time dependent effect on alveolar bone loss and osteoclast activation should occur when ligature ss installed between the first and second molar. Representative sagittal three-dimensional and bi-dimensional views of the mice maxillary molars from each time point group using MicroCT scanning are shown in Figure 2a. We assess bone loss by measuring the CEJ-ABC distances on the distal side of the first molar and mesial side of the second molar on each of the buccal surfaces. As shown in Figure 2b, typically the buccal sides show an acceleration of bone loss from day 3 to day 9 but further significant alveolar bone loss is not observed between 9 to 18 days (Figure 2b). Whilst a previous study has reported that significant alveolar bone loss was observed as early as day 3 in the traditional ligature model16, obvious alveolar bone loss is only seen in our model from day 6 onward. The differences in time course between the different variations of the ligature model are to be expected as ligature placement around the entire 2nd molar provides a larger platform for bacterial accumulation than ligature placement between the 1st and 2nd molars. Typical results seen following TRAP staining at different timepoints are shown in Figure 2c. TRAP staining demonstrates that osteoclast numbers increase at all timepoints compared to control. A dramatic increase in osteoclast activation in the alveolar bone in the interproximal region between the 1st and 2nd molars is seen between 3and 9 days. In contrast osteoclast numbers decrease between 12and 18 days compared with 3–9 days (Figure 2d). Overall, the osteoclast activation and alveolar bone loss mainly takes place in the early phase (3–9 days) followed by a decrease in the later phase (9–18 days). The representative data shown here confirm that osteoclast numbers and alveolar bone loss display similar trends during the development of periodontitis and that, if performed successfully, the simplified ligature-induced periodontitis model will result in bone resorption and a periodontitis phenotype as described above.

Figure 2. Time course of alveolar bone loss and osteoclast activation following insertion of ligature.

(a) Representative sagittal three-dimensional and bi-dimensional views of the maxillary molars 0, 3, 6, 9, 12 and 18 days following insertion of ligature. (b) Measurement of the distances from the cementoenamel junction to the alveolar bone crest (CEJ–ABC) on the buccal side of the ligature site at each time point following insertion of ligature. Results are the mean ± standard deviation (n=5 mice per group). **p<0.01 (One-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post hoc tests). (c) Representative TRAP stained sections of gingival tissues harvested from at each time point following ligature placement at low (top panels, 100X magnification used, scale bar is 100μm) and high (bottom panels, 400X magnification used, scale bar is 50μm) magnifications. 1, the root of the first molar; 2, the root of the second molar; B=alveolar bone; G=gingival epithelium; Arrowheads mark Osteoclasts. (d) Total osteoclast numbers between the 1st and 2sec molars at the ligature site at all time points. Results are the mean ± standard deviation (n=5 mice per group). **p<0.01 (One-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post hoc tests). Appropriate institutional regulatory board permission was obtained for these experiments. Ligatures were retained in all mice used in the experiment so there was no need to exclude any mice from further analysis. Researchers were blind to the groups mice were assigned to when measuring the distances between CEJ to ABC.

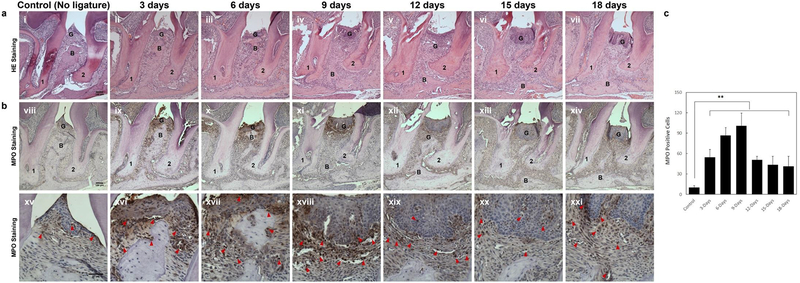

Identification of gingival tissue inflammation phenotype of different timepoints in the simplified ligature model

With the approach demonstrated in our protocol, dynamic gingival tissue inflammation can be observed across different timepoints. Figures 3a–b shows typical histology seen at various times points following ligature placement. H&E staining can be used to show the infiltration of inflammatory cells, loss of connective tissue attachment, and alveolar bone resorption in gingival tissues between the distal root of the first molar and the mesial root of the second molar (Figure 3a). The infiltrated inflammatory cells show a polynuclear structure and a morphological criteria characteristic of neutrophils. Infiltration of MPO positive cells into gingival tissue can be seen by immunohistochemistry as early as day 3 after ligature placement, and obvious acceleration of MPO-positive cell infiltration from day 6 to day 9. By days 12–18 the infiltration of MPO-positive cells is decreased compared to days 3–9 (Figure 3b and c). Thus a pattern of infiltration of inflammation, predominated by neutrophils with a peak at day 9, can be expected by using our ligature model.

Figure 3. Time course of of gingival tissue inflammation following insertion of ligature.

(a) Representative H/E stained sections of gingival tissues harvested 0, 3, 6, 9, 12 and 18 days following insertion of ligature at low magnification (i - vii; 100X magnification used, representative scale bar in panel i is 100μm). (b) Representative MPO immunohistochemistry stained sections of gingival tissues harvested from all time points after ligature placement are shown at low (viii–xiv; 100X magnification used, representative scale bar in panel viii is 100μm) and high (xv-xxi; 400X magnification used, representative scale bar in panel xv is 50μm) magnifications. 1, the root of the first molar; 2, the root of the second molar; B=alveolar bone; G=gingival epithelium; Arrowheads mark MPO-positive cells. (c) Numbers of MPO-positive infiltrating cells (Neutrophils and Macrophage) at the ligature site between the 1st and 2sec molars at all time points. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n=5 mice per group). **p<0.01 (One-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post hoc tests). Appropriate institutional regulatory board permission was obtained for these experiments. Researchers were blind to the groups mice were assigned to when counting the MPO positive cells.

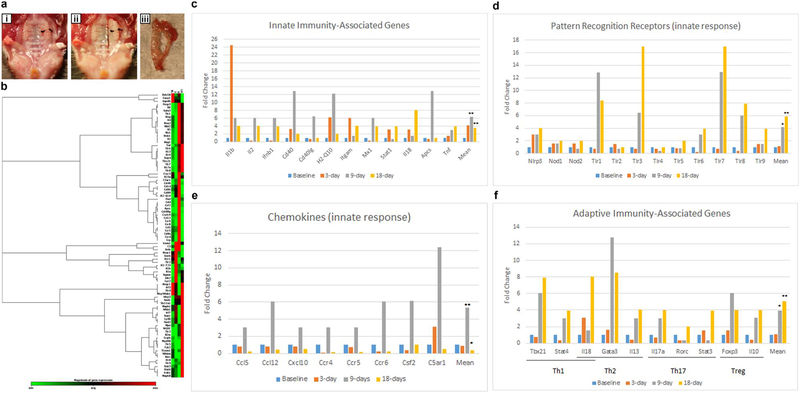

Differential expression of genes associated with innate and adaptive immune responses among different time points in the simplified ligature model

Changes in gene expression for genes associated with the innate and adaptive immune responses are seen in molar region gingivial tissues following establishment of our model (the morphology of this tissue is shown in Figure 4a–c). Typical results seen when using the RT2 Profiler PCR array composed of 84 genes at different timepoints (baseline 0 day, 3 days, 9 days and 18 days) are shown in Figure 4d, using a 1.5-fold change as indicative of a change in expression. Innate immunity-associated genes (Figure 4e) and chemokines (Figure 4g) demonstrate a significant peak of expression at 9 days that then decreases by 18 days. Notably, IL-1β shows a >20-fold increase at 3 days (Figure 4e). IL-1β is well-recognized as an important inflammatory marker in periodontal disease and known to be among the first cytokines to appear in the periodontal disease pathogenesis pathways45–47. The chemokine peak of expression observed at 9 days is also in accordance to the histological data showing a peak of immune cells at 9 days (Figure 3b), which then significantly decreases at 18 days compared to baseline. Interestingly, we found TLR3 and TLR7 demonstrate the greatest fold-change (>16-fold) (Figure 4f). This data indicates that classical PRR such as TLR2 and TLR4 do not change in expression as dramatically as virus-related PRRs including TLR3 and TLR7 (Figure 4f). In addition to being a consequence of the presence of microbial pathogens, this increase might be attributable to the damage-associated molecular signals released from injured or dying cells that are known to promote progression of inflammatory diseases48,49. Consistent with the concept that the adaptive immune responses follow the innate responses, adaptive immune-associated genes peak at 9 days and 18 days (Figure 4h). Expression of markers related to Th1, Th2, Th17 and Treg are all observed. This data illustrates that this model can be used to study host response during the development of periodontitis. Our data indicates that there is a prominent spike in IL-1 by day 3 in this model. Although our model does not provide a clear distinction between pathologies caused by gingivitis versus periodontitis, one important characteristic of human gingivitis seen in both naturally-occurring and experimentally-induced gingivitis is the increase in IL-1β compared to that seen in healthly tissue. The early time course from 0 day to 3 days following insertion of ligature could potentially be suitable to study the pathogenesis of human gingivitis in the mouse. Overall, the results we have obtained demonstrate that we have established a simplified ligature-induced periodontitis model in mice, and this model shows a representative host response following induction of periodontitis in short-term experiments.

Figure 4: The expression of innate and adaptive immune genes at different timepoints following insertion of ligature.

(a-c) Images show the procedure of gingival tissue collection. (a) Picture of mouse palatine with ligature placement between 1st and 2sec molars on the left side of teeth. (b) Picture of mouse palatine after removing of gingival tissue of the ligature side (c) Picture of collected gingival tissue surrounding the molars of ligature side. (d-h) Gene expression as assessed using the RT2 profiler PCR array. (d) Heat map analysis of mRNA expression profiles of innate and adaptive immune responses genes. As shown on the color bar, red represents up-regulated genes and green represents down regulated genes. The relative expression scale changed from 1 to 17 fold. The specific results seen for individual genes are shown in panels e-h, functionally categorized into Innate immunity associated genes (e), Pattern Recognition Receptors (f), Chemokines (g), and Adaptive immunity associated genes (h). The data are presented as the fold change of expression at the 3, 9 and 18 day time points compared to baseline. * p<0.05, **p<0.01 compared to baseline. Appropriate institutional regulatory board permission was obtained for these experiments.

Application of simplified ligature model to study the role of human oral bacterial in periodontitis pathogenesis

By using the ligature model on GF mice, human oral bacterial colonization, bacteria-bacteria interaction and bacteria-host interaction can be evaluated in vivo. The endogenous rodent microflora limits the ability to study the human bacterial colonization process, human bacteria-bacteria, and bacteria-host interactions in SPF rodents. As an alternative, our ligature model can be applied to GF mice infected with human bacteria. As an example we show results following infection with Streptococcus gordonii (S. gordonii, Sg), Veillonella parvula (V.parvula, Vp) and Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum, Fn). Although interspecies communication between S. gordonii - F. nucleatum and S.gordonii - V.parvula have been extensively studied in vitro41,42,43, their co-aggregation in vivo has not been explored. Our protocol can be used to study these interactions (for example, see the experimental workflow shown in Figure 5a). The model can be used to demonstrate that S.gordonii, but not F.nucleatum or V.parvula, can mono-colonize the oral cavity (Figure 5b). The model can also be used to assess co-infection, for example both F.nucleatum and V.parvula successfully co-colonized the ligature sites when co-infected with S.gordonii (Figures 5c–d). The protocol can also be used to evaluate the effects of infection on alveolar bone loss and gingival tissue inflammation. For example, mono-infection of S.gordonii did not result in periodontitis at the ligature site, but co-infection (double and triple infection) induced significant alveolar bone loss (Figures 5e and f) and gingival tissue inflammation (Figure 5g and h). There should be no bacterial contamination, significant alveolar bone loss and gingival tissue inflammation in control mice (Figure 5b, f and h). The in vivo data obtained using this protocol is consistent with the previously reported in vitro data that supports that S.gordonii can facilitate F.nucleatum or V.parvula colonization50,51. Because human bacteria can induce inflammation and alveolar bone loss during periodontitis development in our mouse model, this model can thus potentially be used to further study the role of human oral microbiota associated with periodontitis in vivo.

Figure 5: Human bacteria induced alveolar bone loss and gingival tissue inflammation when using the ligature model in germ free mice.

(a) Diagram of Mono- and Co-infection experimental procedure. Ligature were placed into GF mice on day 0, and infected sequentially on day1 and 2. Ligature and maxilla were collected on day 10. (n=3 per group) (b-d), Number of Sg, Fn and Vp colonies on TSA-agar plates. Ligatures were removed 10 days following insertion into mice and after exposure to mono (b), double (c) or triple (d) infection (e) Representative 3-D MicroCT pictures from each group. The blue lines with double arrowheads indicate the distance between ABC-CEJ. (f) Distances from the cement enamel junction and alveolar bone crest (CEJ-ABC) 10 days following insertion of the ligature in control, mono and co-infection groups. (g) Representative HE and MPO Immunohistostaining sections of gingival tissues harvested from ligature side of control and each infection group (representative scale bars are shown in the left hand panel and are 100μm for the top and middle images and 20μm for the lower images). 1, the root of the first molar; 2, the root of the second molar; B=alveolar bone; G=gingival epithelium; Red Arrowheads mark MPO-positive cells in the gingival tissues. (h) Number of MPO positive cells 10 days following ligature placement for each group. N=3 in panels b, c, d, f and h. *p<0.05 (One-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post hoc tests). Appropriate institutional regulatory board permission was obtained for these experiments.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Typical colony morphology for S. gordonii, F. nucleatum and V. parvula on TSA plate.

Alternative Supplementary Figure 2: Detailed blueprints required for manufacture of the Murine Dental Bed.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by T90DE021986 and F32DE026688 (YZJ), IBM Junior Faculty Development Award from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and K01DE027087 (JTM), and 5R01DE023836 (SO) 5R01DE025207 (MHS). The authors thank Dr. William V. Giannobile in University of Michigan School of Dentistry for constructive suggestion and helpful discussion. The authors thank Baocheng Huang and Jennifer Ashley from the Histology Research Core Facility at UNC for histological embedding and section. The authors thank the Microscope Core facility for the images. The authors thank UNC Biomedical Research Imaging Center for MicroCT scanning. The authors thank the Germ Free & Gnotobiotic Mice core facility in University of Michigan and University of North Carolina for the assistance of human bacterial infection experiment. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References:

- 1.Hajishengallis G Immunomicrobial pathogenesis of periodontitis: keystones, pathobionts, and host response. Trends Immunol 35, 3–11, doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.09.001 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hajishengallis G, Darveau RP & Curtis MA The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 10, 717–725, doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2873 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richards D Review finds that severe periodontitis affects 11% of the world population. Evid Based Dent 15, 70–71, doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6401037 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kassebaum NJ et al. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990–2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. Journal of dental research 93, 1045–1053, doi: 10.1177/0022034514552491 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Thornton-Evans GO & Genco RJ Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. Journal of dental research 91, 914–920, doi: 10.1177/0022034512457373 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tonetti MS, Jepsen S, Jin L & Otomo-Corgel J Impact of the global burden of periodontal diseases on health, nutrition and wellbeing of mankind: A call for global action. Journal of clinical periodontology 44, 456–462, doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12732 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Pablo P, Chapple IL, Buckley CD & Dietrich T Periodontitis in systemic rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 5, 218–224, doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.28 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinho MM, Faria-Almeida R, Azevedo E, Manso MC & Martins L Periodontitis and atherosclerosis: an observational study. J Periodontal Res 48, 452–457, doi: 10.1111/jre.12026 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoon AJ, Cheng B, Philipone E, Turner R & Lamster IB Inflammatory biomarkers in saliva: assessing the strength of association of diabetes mellitus and periodontal status with the oral inflammatory burden. J Clin Periodontol 39, 434–440, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01866.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colombo AP et al. Clinical and microbiological features of refractory periodontitis subjects. Journal of clinical periodontology 25, 169–180 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine M, Lohinai Z & Teles RP Low Biofilm Lysine Content in Refractory Chronic Periodontitis. Journal of periodontology 88, 181–189, doi: 10.1902/jop.2016.160302 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oz HS & Puleo DA Animal models for periodontal disease. J Biomed Biotechnol 2011, 754857, doi: 10.1155/2011/754857 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graves DT, Kang J, Andriankaja O, Wada K & Rossa C Jr. Animal models to study host-bacteria interactions involved in periodontitis. Front Oral Biol 15, 117–132, doi: 10.1159/000329675 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graves DT, Fine D, Teng YT, Van Dyke TE & Hajishengallis G The use of rodent models to investigate host-bacteria interactions related to periodontal diseases. Journal of clinical periodontology 35, 89–105, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01172.x (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Padial-Molina M, Rodriguez JC, Volk SL & Rios HF Standardized in vivo model for studying novel regenerative approaches for multitissue bone-ligament interfaces. Nat Protoc 10, 1038–1049, doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.063 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abe T & Hajishengallis G Optimization of the ligature-induced periodontitis model in mice. J Immunol Methods 394, 49–54, doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2013.05.002 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiner GS, DeMarco TJ & Bissada NF Long term effect of systemic tetracycline administration on the severity of induced periodontitis in the rat. Journal of periodontology 50, 619–623, doi: 10.1902/jop.1979.50.12.619 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glowacki AJ et al. Prevention of inflammation-mediated bone loss in murine and canine periodontal disease via recruitment of regulatory lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 18525–18530, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302829110 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kajikawa T et al. Milk fat globule epidermal growth factor 8 inhibits periodontitis in non-human primates and its gingival crevicular fluid levels can differentiate periodontal health from disease in humans. Journal of clinical periodontology 44, 472–483, doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12707 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin R, Bermudez-Humaran LG & Langella P Gnotobiotic Rodents: An In Vivo Model for the Study of Microbe-Microbe Interactions. Front Microbiol 7, 409, doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00409 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajishengallis G et al. Low-abundance biofilm species orchestrates inflammatory periodontal disease through the commensal microbiota and complement. Cell host & microbe 10, 497–506, doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.006 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zenobia C et al. Commensal bacteria-dependent select expression of CXCL2 contributes to periodontal tissue homeostasis. Cell Microbiol 15, 1419–1426, doi: 10.1111/cmi.12127 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grover M & Kashyap PC Germ-free mice as a model to study effect of gut microbiota on host physiology. Neurogastroenterol Motil 26, 745–748, doi: 10.1111/nmo.12366 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rovin S, Costich ER & Gordon HA The influence of bacteria and irritation in the initiation of periodontal disease in germfree and conventional rats. J Periodontal Res 1, 193–204 (1966). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao E et al. Diabetes Enhances IL-17 Expression and Alters the Oral Microbiome to Increase Its Pathogenicity. Cell Host Microbe 22, 120–128.e124, doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.06.014 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haara O et al. Ectodysplasin regulates activator-inhibitor balance in murine tooth development through Fgf20 signaling. Development 139, 3189–3199, doi: 10.1242/dev.079558 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martins MD et al. Epigenetic Modifications of Histones in Periodontal Disease. J Dent Res 95, 215–222, doi: 10.1177/0022034515611876 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiao Y et al. Induction of bone loss by pathobiont-mediated Nod1 signaling in the oral cavity. Cell Host Microbe 13, 595–601, doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.04.005 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu Y et al. IL-21/anti-Tim1/CD40 ligand promotes B10 activity in vitro and alleviates bone loss in experimental periodontitis in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta 1863, 2149–2157, doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.06.001 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chun J, Kim KY, Lee JH & Choi Y The analysis of oral microbial communities of wild-type and toll-like receptor 2-deficient mice using a 454 GS FLX Titanium pyrosequencer. BMC Microbiol 10, 101, doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-101 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abe T et al. Local complement-targeted intervention in periodontitis: proof-of-concept using a C5a receptor (CD88) antagonist. J Immunol 189, 5442–5448, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202339 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]