Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO)-releasing polymers have proven useful for improving the biocompatibility of in vivo glucose biosensors. Unfortunately, leaching of the NO donor from the polymer matrix remains a critical design flaw of NO-releasing membranes. Herein, a toolbox of NO-releasing silica nanoparticles (SNPs) was utilized to systematically evaluate SNP leaching from a diverse selection of biomedical-grade polyurethane sensor membranes. Glucose sensor analytical performance and NO-release kinetics from the sensor membranes were also evaluated as a function of particle and polyurethane chemistries. Particles modified with N-diazeniumdiolate NO donors were prone to leaching from PU membranes due to the zwitterionic nature of the NO donor modification. Leaching was minimized (<5% of the entrapped silica over 1 mo) in low water uptake PUs. However, SNP modification with neutral S-nitrosothiol (RSNO) NO donors lead to biphasic leaching behavior. Particles with low alkanethiol content (<3.0 wt% sulfur) leached excessively from a hydrogel PU formulation (HP-93A-100 PU), while particles with greater degrees of thiol modification did not leach from any of the PUs tested. A functional glucose sensor was developed using an optimized HP-93A-100 PU membrane doped with RSNO-modified SNPs as the outer, glucose diffusion-limiting layer. The realized sensor design responded linearly to physiological concentrations of glucose (min. 1–21 mM) over 2 wk incubation in PBS and released NO at >0.8 pmol cm−2 s−1 for up to 6 d with no detectable (<0.6%) particle leaching.

Keywords: Glucose biosensor, nitric oxide, silica nanoparticle, foreign body response, continuous glucose monitor, biocompatibility, in vivo sensor

Graphical Abstract

Effective diabetes management relies on accurate blood glucose (BG) measurement to maintain target levels of glycemia.1–3 Self-monitoring of BG levels has traditionally been carried out using portable glucometers. Although glucometers are generally accurate and reliable, poor patient compliance and infrequent sampling lead to inconsistent BG control.4 Severe hyperglycemia or brief and potentially life-threatening hypoglycemic events frequently go undetected as a result. Implantable electrochemical continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) that measure glucose in interstitial fluid have received significant focus with the goal of alleviating the sampling issues associated with discrete BG measurement.5–6 Such devices facilitate identification of temporal BG fluctuations and, based on these trends, may be used to predict glycemia in the immediate future (i.e., as a hypoglycemic alarm).

Despite the availability of implantable glucose biosensors for human use, CGM devices have not been widely adopted due to performance issues and difficulty of use (e.g., frequent calibration, false hypoglycemic alarms).4 Poor sensor accuracy is due in large part to the foreign body response (FBR), a cascade of intense inflammatory/wound healing reactions that transpire at the surface of the implanted CGM.4,7–10 Initial blood protein adhesion reduces sensor sensitivity by 40–80% and this protein layer mediates later inflammatory cell attachment.11 Influx of inflammatory cells occurs after tissue injury and has been identified as contributing factor to erratic sensor response during the first several days of implantation.8 Eventually, the sensor is sequestered from native tissue by fibroblast construction of a collagenous foreign body capsule that obstructs glucose transport to the sensor, resulting in sensor failure.

The performance of implanted devices is inherently linked with FBR severity.12 A general belief is that in vivo glucose sensors may benefit from reduced inflammation and increased neovascularization. A widely investigated approach for mitigating the FBR is the use of hydrophilic coatings (e.g., hydrogels,13 zwitterionic polymers14–16) to reduce protein adsorption and concomitant cell adhesion. The release of bioactive molecules (e.g., Dexamethasone17–19 and vascular endothelial growth factor19) from sensors have also been studied as methods for more directly influencing key inflammatory and wound healing events. Our laboratory has focused on the release of nitric oxide (NO), an endogenous radical gas with integral roles in angiogenesis and the wound healing.20–22 Indeed, NO-releasing polymers have been shown to reduce FBR-related inflammation and collagen encapsulation.23–26 In concert with tissue response studies, in vivo glucose biosensors coated with similar NO-releasing polymers have improved short-term (1–3 d) sensor accuracy.27–28

Due to NO’s reactive nature, a significant body of research has focused on suitable NO storage and release strategies. The most successful work to date (based on total NO storage and NO-release durations) has relied on incorporating NO-releasing molecules (NO donors) into polymeric sensor coatings (e.g., polyurethanes).29–33 The NO-release properties (i.e., storage and kinetics) are straightforwardly controlled by altering the identity/type of both the NO donor and polymer matrix. For example, NO-releasing silica nanoparticles (SNPs) have been used to prepare NO-releasing polyurethane (PU) sensor membranes because of their large NO storage and controllable NO-release kinetics.29,34–37 However, a key design challenge associated with many NO-releasing polymers is undesirable leaching of the entrapped NO donors.28–31,38 Although silica is considered inert,39 NO donor modifications to SNPs may alter their association with mammalian cells, thereby increasing cytotoxicity.34 Leaching of constituent silica may also exacerbate local foreign body reactions, as the SNPs may be phagocytosed by macrophages and increase the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor α, interleukin 1β).40–41

Herein, we report on the design of functional glucose biosensor membranes with favorable partitioning of NO-releasing silica particles into the polymer matrix. The physicochemical properties of both the dopant SNPs (e.g., NO donor identity, extent of modification) and the PU matrix (e.g., water uptake) were examined for potential influence to particle leaching and NO-release properties of the membranes. The most promising membranes were employed to fabricate glucose biosensors with appropriate analytical performance and NO-release durations of up to 7 d.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

Tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS), tetramethylorthosilicate (TMOS), 3-mercaptopropyltrimethoxysilane (MPTMS), N-methylaminopropyltrimethoxysilane (MAP), N-(6-aminohexyl)-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane (AHAP), and 3-(trimethoxysilylpropyl)diethylenetriamine (DET) were purchased from Gelest (Morrisville, PA). Sodium methoxide (NaOMe; 5.4 M in methanol), anhydrous N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), anhydrous methanol (MeOH), anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF), 200 proof ethanol (EtOH), aqueous ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH; 29.42 wt% ammonia), concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl), toluene, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) and all salts were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). The toluene was dried/stored over molecular sieves prior to use. Methyltrimethoxysilane (MTMOS), Glucose oxidase (Type VII lyophilized powder, ≥100,000 U g−1) from Aspergillus niger, and diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Nitrogen (N2), argon (Ar), and nitric oxide calibration (25.87 ppm in N2) gases were purchased from Airgas National Welders (Raleigh, NC). Pure NO gas was purchased from Praxair (Danbury, CT). Silver wire (127 µm dia.) and PFA-coated 90:10 platinum:iridium (Pt:Ir) wire (127 µm bare dia.) were purchased from A-M Systems (Sequim, WA). Soft stainless steel wire (356 µm dia.) was purchased from McMaster-Carr (Atlanta, GA). Polyurethanes HP-93A-100, PC-3585A, SG-85A, and TT-2072D-B20 were received from Lubrizol (Cleveland, OH). Hydrothane polyurethane AL-25–80A was obtained from AdvanSource Biomaterials (Wilmington, MA). Water was purified using a Millipore Reference water purification system to a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ cm and a total organic content of <6 ppb.

Synthesis of N-diazeniumdiolate-modified silica nanoparticles

Secondary amine-modified nanoparticles were first synthesized by variants of the Stöber method. Ultimately, secondary amines introduced to the SNPs were converted to N-diazeniumdiolate NO donors by reaction with NO gas. Detailed synthesis procedures are provided in the Supporting Information.

Synthesis of S-nitrosothiol-modified silica nanoparticles

Thiol-modified SNPs were synthesized by co-condensation of MPTMS with either TEOS or TMOS (tetraalkoxy backbone silanes) and functionalized to release NO in a subsequent nitrosation step.42 Detailed synthesis procedures are provided in the Supporting Information.

Preparation and evaluation of NO-releasing mock sensors

Polyurethane (PU) solutions were prepared by adding 240 mg of the appropriate PU to 2.25 mL THF and dissolved by sonicating at 60 °C. In a separate solution, NO-releasing SNPs were dispersed in THF via sonication and added to the PU solution (after cooling to room temperature). Unless otherwise indicated, the PU concentration was 80 mg mL−1 and SNPs were incorporated at 20 wt% (20 mg mL−1) relative to the polymer for all experiments.

Stainless steel wire (357 µm dia.) was selected as a coating substrate to mimic the size and geometry of functional, needle-type glucose sensors. Wires were first cleaned by sonication in EtOH, and then coated with the NO-releasing membranes by dip-coating into the PU/SNP solution. Each deposited layer was allowed to dry for ~20 s before additional coating. The number of coats was varied for each PU solution to provide uniform ~40–50 µm thick coatings, as determined by measurement with calipers and from the electron micrographs. Leaching of the SNPs was monitored over time via inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) using a Prodigy high-dispersion ICP (Teledyne-Leeman Laboratiories; Hudson, NH). Coated substrates were immersed in PBS and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h–28 d. At pre-determined time points, the substrates were removed from solution and analyzed for silicon content. The instrument was initially calibrated using sodium silicate standards (0.1–25 ppm in PBS; 251.611 nm Si emission line) to verify linear response over anticipated particle concentrations. Individual standards for each particle system were prepared and used to determine particle leaching from corresponding membranes. Of importance, all buffers/solutions that were used for leaching measurements were prepared in polypropylene tubes because silicic acid was found to leach from glass storage vials. It was verified that neither the wire substrates nor the polypropylene incubation vessels contributed to detectable Si signal.

Nitric oxide release measurements

Nitric oxide release was evaluated in real-time (1 Hz sampling frequency) using a Sievers 280i chemiluminescent NO analyzer (NOA; Boulder, CO). The NOA was calibrated via a two-point linear calibration, with 25.87 ppm NO (in N2) serving as the first calibration standard and air passed through an NO zero filter as the blank value. The NO-releasing material (either 1 mg of particles or a coated mock sensor) was added to deoxygenated phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 10 mM, pH 7.4) at 37 °C. In the case of RSNO-based materials, NO release was restricted to thermal mechanisms by addition of 500 µM DTPA to the PBS and by shielding the entire sample flask from light using aluminum foil. A stream of N2 gas was bubbled into solution at 80 mL min−1 to carry the liberated NO to the NOA reaction cell. Supplemental N2 gas was provided to the reaction flask in order to match the instrument collection rate of 200 mL min−1. Nitric oxide was detected indirectly by reaction with ozone, which yields a chemiluminescent excited-state nitrogen dioxide species. Measurements were terminated when NO release from the silica particles decreased below 10 ppb mg−1. For mock sensors coated with NO-releasing PU materials, NO release measurements were terminated when NO fluxes were below 0.8 pmol cm−2 s−1 (instrument LOD at S/N ratio 6–10). Of note, NO-release properties for the NO donor-modified SNPs are provided in the Supporting Information (Table S3).

In cases where NO release from the PU membranes was below the NOA limit of detection, the Griess Assay was used to measure NO indirectly via its oxidative conversion to nitrite, as previously described.36 Briefly, samples for NO measurement in PBS (50 µL) were mixed with 50 µL each of 0.1% w/v aqueous N-(1-napthyl)ethylene diamine and 1% w/v sulfanilamide in 5% v/v aqueous phosphoric acid and incubated for 10 min to form an azo dye. Sample absorbance measurements were collected at 540 nm on a Labsystem MultiskanRC microplate spectrophotometer (Helsinki, Finland) and compared to a calibration curve generated from nitrite standards (2–100 µM) for quantitative NO determination.

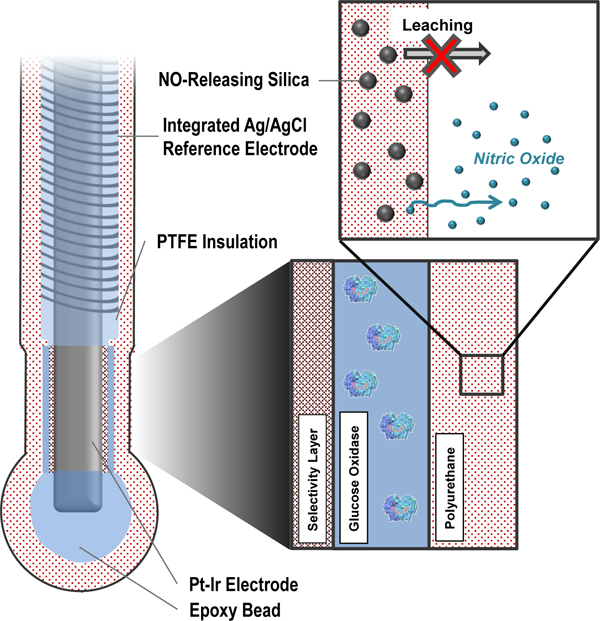

Design and analytical performance of miniaturized NO-releasing glucose biosensors

First generation (i.e., peroxide-detecting) needle-type electrochemical glucose biosensors were fabricated and used for evaluation of the NO-releasing membranes.43–44 The bare sensors were constructed by winding a 127 µm silver/silver chloride (Ag|AgCl) reference electrode around a PFA-insulated 90:10 Pt:Ir wire (127 µm bare dia.). A ~2 mm length of Pt:Ir wire was exposed by removal of the PFA coating and served as the working electrode. Of note, all potentials defined hereafter are with respect to the integrated Ag|AgCl pseudo-reference electrode.

The bare sensors were initially cleaned via cyclic voltammetry in 0.5 M sulfuric acid (−0.25–+1.20 V, 30 cycles, 0.1 V s−1) and then functionalized for glucose detection and NO release via a multilayer deposition approach. A polymerized m-phenylenediamine (m-PD) membrane was first electrodeposited on the bare electrode surface as a size exclusion membrane to improve selectivity for H2O2 oxidation.45 The electropolymerization process was carried out via cyclic voltammetry (0–+1.0 V, 20 cycles, 0.1 V s−1) in a 100 mM m-PD solution prepared in deoxygenated PBS (pH 7.41). Next, GOx was immobilized on the working electrode by entrapment in a silica solution-gel (sol-gel).46 The GOx sol-gel precursor solution was prepared by mixing a solution of GOx in water (50 µL; 120 mg mL−1) with a mixture of EtOH (100 µL) and MTMOS (25 µL). The resulting solution was aged on a shaker for 10 min. The sensors were coated with the GOx/silica gel by dipcoating 15 times (5 s still time, 10 s intermittent dry periods) into the gel precursor solution. Last, the sensors were coated with either bare PU or the NO-releasing PU/SNP composites via a loop-casting protocol, providing uniform PU deposition over the sensor electrodes. A 6.5 µL droplet of the PU solution was deposited on a stainless steel wire loop (2 mm dia.) and the loop was passed over the working and reference electrodes. In the case of the NO-releasing membranes, subsequent layers were coated onto electrodes after brief (~5 min) dry times for a total of 7 PU/SNP depositions. The PU concentration used for the loop-casting procedure was varied for the unmodified PUs (20–80 mg mL−1) and was 50 mg mL−1 (in 3:1 THF:DMF) for the NO-releasing membranes. The particle concentration was varied in the PU solution at 6.3–50.0 mg mL−1. Where indicated, a PC-3585A outer layer (“topcoat”) was applied to the sensors via loopcasting using a 30 mg mL−1 PU solution prepared in 3:1 THF:DMF and allowed to dry for >1 h.

In vitro sensor analytical performance was assessed in PBS (pH 7.4) or porcine serum under stirred conditions using a CH Instruments model 1030C multi-channel potentiostat (Austin, TX). Sensors were pre-conditioned by polarizing sensors in PBS (37 °C; +0.600 V vs. Ag/AgCl) until a stable background current was measured. Glucose was detected indirectly by amperometric oxidation of H2O2 at +0.600 V. Sensors were calibrated by incrementally increasing the buffer glucose concentration to 30 mM. The sensor linear dynamic range (LDR) was determined as the maximum glucose concentration achieved with no saturation in glucose response. A threshold of R2>0.99 was used for the linear correlation coefficient. Glucose sensitivities are reported as the slope of the linear trend line correlating the measured anodic current to glucose concentration over the linear response range. Amperometric selectivity coefficients for glucose over common electroactive interfering species were calculated according to published methods.36,44

Membrane and particle characterization

Morphology of the nanoparticles was evaluated using a FEI Helios 600 Nanolab scanning electron microscope (SEM; Hillsboro, OR). Scanning electron micrographs of the N-diazeniumdiolate- and S-nitrosothiol-modified particles are provided in the Supporting Information (Figures S2 and S3, respectively). Sensor membranes were imaged using a FEI Quanta 200 environmental scanning electron microscope (Hillsboro, OR). Nitrogen sorption isotherms were used to evaluate SNP porosity and were collected on a Micromeritics Tristar II 3020 surface area and porosity analyzer (Norcross, GA). Samples were dried at 110 °C under N2 gas for 18 h and degassed for 2 h prior to analysis. Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis of the monolayer adsorption isotherm region (0.05<p/p°<0.20) was used for determination of specific surface area.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Polyurethane (PU) materials have been utilized as glucose sensor membranes because they generally elicit only a mild FBR and, depending on their composition, have appropriate glucose/oxygen permeabilities necessary for fabricating glucose sensors.47–48 Unfortunately, the literature is not clear as to how glucose sensor analytical performance depends on PU composition and water uptake, important parameters that may also impact NO release and NO donor leaching. Initial experiments thus focused on identifying PUs that could be used to fabricate functional electrochemical glucose sensors prior to modification with the NO-releasing scaffolds.

Glucose biosensors were systematically modified with glucose diffusion-limiting PU coatings via a loopcasting method.43,45 The analytical performance of the sensors was evaluated as a function of PU water uptake and the concentration of the PU loop-casting solution using four commercially-available PUs: HP-93A-100, AL-25–80A, SG-85A, and PC-3585A. Regardless of PU type, sensors that were prepared using low concentration PU solutions (20 and 35 mg mL−1) did not yield stable glucose response (data not shown), whereas 50 mg mL−1 PU solutions lead to more predictable sensor performance. Both the glucose sensitivity and linear range of the sensors were dependent on the PU water uptake (Table 1). For instance, sensors prepared with the high-water uptake PU HP-93A-100 had large glucose sensitivity (38.2 nA mM−1 mm−2) but insufficient linear dynamic range (1–3 mM), indicating that the membrane did not serve as a substantial barrier to glucose diffusion. In contrast, more hydrophobic SG-85A and PC-3585A PUs (water uptake <0.2 mg per mgPU) improved the linear glucose range of the sensors (1–15 mM).

Table 1.

| PU Type | PU Water uptake (mg mg−1)d |

Linear Dynamic Rangee |

Sensitivity (nA mM−1 mm−2)f |

Sensitivity Retention (%)g |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 d | 5 d | 7 d | 14 d | ||||

| HP-93A-100 | 2.6±0.3c | 1–3 mM | 38.2±15.0 | 54.3±29.6 | 57.2±7.3 | 44.3±8.9 | 42.3±7.3 |

| AL-25–80A | 0.6±0.3c | 1–6 mM | 44.7±15.2 | 80.2±10.7 | 82.9±28.8 | 58.5±10.2 | 58.3±11.0 |

| SG-85A | 0.2±0.2c | 1–15 mM | 29.5±15.3 | 86.1±10.1 | 85.5±18.3 | 64.9±6.1 | 67.2±8.1 |

| PC-3585A | 0.0±0.0 | 1–15 mM | 20.1±4.2 | 80.5±13.6 | 77.0±7.2 | 55.2±2.5 | 56.2±2.4 |

Error bars represent standard deviation for n≥3 separate experiments.

PU concentration in the loop-casting solution was 50 mg mL−1.

Water uptake measurements described in Koh et al., Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2011, 28, 17–24.

Water uptake expressed as mgwater per mgPU.

Linear dynamic range determined from glucose sensor calibration curves as the concentration range over which the associated linear trendline had an R2 value >0.99.

Determined as the slope of the trendline fit to the sensor current-glucose response over the linear dynamic range on the first day of testing.

Glucose sensitivity after soaking sensors in PBS at 37 °C (relative to the sensitivity on the first day of testing).

Regardless of PU type, sensor sensitivity to glucose steadily decreased during incubation in PBS. This feature was consistent with sensors prepared using 80 mg mL−1 PU solutions (Table S4). The magnitude of the initial decrease (i.e., during the first 5 d) varied between sensors coated with different polyurethanes, eventually stabilizing after ~7 d. Although undesirable, slowly changing glucose sensitivity is a common occurrence noted by others for sensors prepared using PU43,45 or poly(vinyl alcohol).49 Electrochemical glucose sensors generally require a 5–7 d pre-conditioning period for response stabilization as the polymer membranes undergo hydration and swelling.43,45 The four PU types that were utilized in this study were thus deemed satisfactory for further development of NO-releasing membranes.

Polyurethane membranes incorporating N-diazeniumdiolate functionalized silica particles

Mesoporous SNPs were selected for developing NO-releasing PU membranes due to their favorable NO storage properties. The SNPs were synthesized using an approach that also allowed for the chemical structure of the amine modification and the size of the particles to be tuned independent of one another.37 In a subsequent chemical step, the secondary amines were easily reacted with NO gas to form N-diazeniumdiolate NO donors. Particles ~800 nm in diameter (modified with DET/NO) were selected for initial evaluation in PU films because a preliminary study suggested larger (~1 µm) SNPs might be less prone to leaching than similarly prepared smaller (<300 nm) scaffolds.29

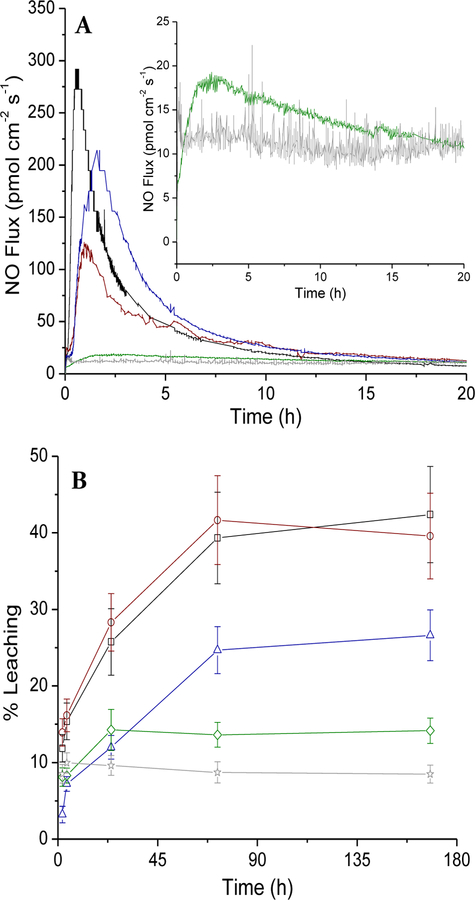

Nitric oxide release from the DET particle-doped PU membranes was measured in physiological buffer (pH 7.4 PBS at 37 °C) as a function of PU composition. Expectedly, PU membranes with moderate-to-high water uptake properties (HP-93A-100, AL-25–80A, and 1:1 mixture of AL-25–80A :SG-85A) released large initial NO fluxes (124.0–311.5 pmol cm−2 s−1) due to more rapid N-diazeniumdiolate decomposition relative to membranes consisting of either SG-85A or PC-3585A (<20 pmol cm−2 s−1; Figure 1A). For example, DET/NO embedded in HP-93A-100 PU (a hydrogel PU formulation with water uptake at ~150 wt% PU mass) released the largest initial NO levels (312 pmol cm−2 s−1, tmax=37.0 min), maintaining NO release above 0.8 pmol cm−2 s−1 (the detection limit of the NOA for this experiment) for only ~60 h. In contrast, composites that were prepared using the more hydrophobic PC-3585A PU (<2 wt% water uptake) released low, detectable NO fluxes (1–14 pmol cm−2 s−1) for 7 d.

Figure 1.

(A) Initial (20 h) NO release and (B) 1 wk particle leaching measurements for HP-93A-100 (black, square), AL-25–80A (red, circle), SG-85A (green, diamond), and PC-3585A (gray, star) polyurethane materials. The blue (triangle) trace in both figures is a 1:1 mixture of AL-25–80A:SG-85A. Inset in (A) shows the NO fluxes released from SG-85A and PC-3585A composites over 20 h. All materials are doped with 20 wt% 800 nm DET/NO SNPs.

Leaching of the DET/NO particles from the PU composites was assessed by monitoring the silicon emission intensity via ICP-OES from membrane soak solutions (PBS at 37 °C) over 7 d. All DET/NO-based membrane compositions exhibited detectable levels of leaching (8–42% total mass of incorporated particles) over 1–3 d incubation in PBS, with no additional leaching beyond 3 d (Figure 1B). The degree of leaching correlated strongly with PU water uptake. The more hydrophobic polyurethanes PC-3585A and SG-85A (water uptake <0.2 mg/mg for both PUs) leached 14.2 and 8.5% the total encapsulated DET/NO SNPs (321 and 181 µg cm−2, respectively) over the 7 d soak period. Significantly greater particle leaching (39.6 and 42.4%) was measured for high water uptake HP-93A-100 and AL-25–80A PUs, respectively, corresponding to ~900 µg SNPs cm−2.

Membranes prepared using similarly-sized (800 nm) particles with either MAP/NO or AHAP/NO N-diazeniumdiolate modifications (monoamine- and diamine-based NO donors, respectively) were used to elucidate the influence of aminosilane structure on particle leaching. Comparable 7 d leaching values were measured for AHAP/NO and DET/NO particles (43.8 and 42.4 %, respectively), whereas MAP/NO particles leached from the membranes completely (100.7 %; Figure S5). Although the chemical structure of the aminosilane surface modifications likely impacted interactions between the particle surface and the encompassing PU matrix, it was noted that a greater degree of N-diazeniumdiolate modification (2.22 vs 1.30–1.61 µmol NO mg−1) was a hallmark of the particle system with the greatest leaching propensity (MAP/NO).

To further understand the particle leaching process, we evaluated DET/NO particle leaching over a range of particle sizes (150, 450, and 800 nm). Experiments were carried out using a moderately hydrophobic PU mixture (1:1) of AL-25–80A:SG-85A, as more hydrophilic PUs (e.g., HP-93A-100) yielded elevated levels of leaching for most of the particle types tested. In contrast with previous suggestions that larger particles are less prone to leaching,29 no clear relationship between particle size and the extent leaching was observed (Figure S6). Similar leaching values were measured after 7 d immersion in PBS for 150 nm (26.4%) and 800 nm (23.7%) DET/NO SNPs. The 450 nm particles were associated with the greatest particle leaching (40.0%) despite having the same DET/NO modification as the other two SNP systems. Of note, the 450 nm particles had larger NO storage (2.41 µmol NO mg−1) relative to the 150 nm and 800 nm particle sizes (1.87 and 1.61 µmol mg−1, respectively), again implicating the N-diazeniumdiolate modification as a potential factor in the leaching process.

The relationship between N-diazeniumdiolate modification and particle leaching was more directly interrogated in two additional experiments using the same PU compositions (1:1 AL-25–80A:SG-85A). First, non-NO-releasing 800 nm DET particles (i.e., DET particles that did not undergo the NO donor formation reaction) were doped into PU membranes and compared with analogous NO-releasing systems. Leaching of the total incorporated silica was reduced to 13.4 % at 1 wk compared with 26.6 % for the NO-releasing membrane. Second, the role of N-diazeniumdiolate density (i.e., total NO storage) on particle/membrane stability was examined using two similarly sized DET-modified SNPs with different NO storage capacity. Two separate bare SiO2 particle types were synthesized with a nominal size of ~150 nm but distinct porosity (i.e., mesoporous or nonporous). After NO donor modification, the mesoporous and nonporous DET/NO particles stored 1.33 and 0.22 µmol NO mg−1, with comparable specific surface areas (21 and 19 m2 g−1, respectively). As anticipated, increased levels of particle leaching (17.6±0.2%) were measured for the NO-releasing SNPs that stored more NO versus 6.4±1.1% for the nonporous particles.

Greater particle NO storage consistently correlated with increased leaching regardless of particle size, the chemical structure of the aminosilane precursor, or the water uptake of the polyurethane matrix. These leaching data pointed to the high surface charge density of the particles being a key contributing factor to particle stability in the membranes. We rationalized that greater leaching may be due to favorable interactions of the SNPs with water. This assertion was confirmed by the obvious correlation between leaching and PU water uptake. However, N-diazeniumdiolate modification was not the sole factor for particle leaching, as even amine-modified (non-NO-releasing) particles leached from the PU membranes. In total, it was concluded that ionic silanoates, ammonium groups, and N-diazeniumdiolates all contributed to the overall particle surface charge and associated leaching.

In preliminary experiments, additional hydrophobic PU layers (i.e., without NO-releasing particles) were deposited on top of the NO-releasing coating to serve as a barrier to particle leaching. Although the PU topcoats reduced the magnitude of particle leaching, this approach did not prevent leaching completely. For example, leaching of DET/NO particles (800 nm) from PC-3585A membranes was reduced from 14.2 to 6.6% with the addition of a SG-85A topcoat (60 mg mL−1 in THF). Leaching of N-diazeniumdiolate-based SNPs was minimized by using low-water uptake polyurethanes. When embedded in hydrophobic TT-2072D-B20 PU membranes, only ~4.7 % of the incorporated 800 nm DET/NO particles were detected after one month soak periods. Unfortunately, these formulations were incompatible with functional sensor designs due to poor glucose permeability. Even sensors with thin (<5 µm) coatings did not respond to physiological glucose concentrations (data not shown).

Polyurethane membranes incorporating S-nitrosothiol functionalized silica particles

S-nitrosothiols (RSNOs) are neutral NO donors formed on thiols and, in this manner, are structurally distinct from zwitterionic N-diazeniumdiolates. We hypothesized that the neutral RSNO modification might reduce the tendency of the SNPs to leach from PU membranes by eliminating charge contributions characteristic of cationic amines and zwitterionic N-diazeniumdolates. Thiol-functionalized silica-based particles were prepared using a variant of the Stöber method by co-condensation of MPTMS (a mercaptosilane) with a backbone tetraalkoxysilane.42 S-nitrosothiol NO donors were subsequently formed on the primary thiols by reaction of the SNPs with acidified nitrite. Leaching measurements were initially carried out for a single SNP composition (75 mol% MPTMS balance TEOS) as a function of PU type, analogous to the study of the N-diazeniumdiolate-modified particles. The measured Si emission intensity after a 7 d membrane soak period (PBS at 37 °C) was below the ICP-OES limit of detection (16.5 µg SNPs cm−2) for all PU compositions tested, corresponding to <0.6% of the total mass of SNPs incorporated in the membranes.

To assess the role of MPTMS modification on particle leaching, SNPs of varying alkanethiol content (25, 40, 75, and 85% MPTMS; SEMs provided in Figure S3) were incorporated into HP-93A-100 films and immersed in physiological buffer for 7 d (Table 2). Unexpectedly, the data revealed a clear dichotomy in leaching measurements for RSNO-modified SNPs. Particles with lower alkanethiol content (i.e., 25 and 40% MPTMS, with reported thiol content <3.0 % sulfur by mass42) leached entirely from the HP-93A-100 membranes over 7 d (2.90 and 2.89 mg cm2, respectively), while reduced leaching (<0.024 mg cm−2, below ICP-OES LOD) was observed for membranes containing SNPs with greater MPTMS-content (75 and 85% MPTMS; 15.2–20.6 wt% sulfur).42 The RSNO-modified particles retain moderate, anionic zeta-potentials (due to acidic silanol groups) that did not vary appreciably with MPTMS concentration (−29.9, −30.8, and −31.2 mV for the 25, 40, and 75% MPTMS particles). Despite similar surface charges, only SNPs with >75% MPTMS content did not leach appreciably from the HP-93A-100 membranes, reinforcing the concept that the large degree of hydrophobic alkanethiol modification counteracts particle leaching.

Table 2.

Particle leaching from membranes doped with RSNO-modified silica particles of varying MPTMS content.a,b

| mol% MPTMS |

Backbone Silane |

Sizec (nm) |

Leachingd |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg cm−2 | % | |||

| 25 | TMOS | 234±37 | 2.90±0.35 | 99.7±6.6 |

| 40 | TMOS | 248±41 | 2.89±0.19 | 100.3±12.0 |

| 75 | TEOS | 622±53 | <0.016 | <0.6 |

| 85 | TMOS | 660±86 | <0.024 | <0.8 |

| 85 | TEOS | 864±94 | <0.024 | <0.8 |

Error bars represent standard deviation for n≥3 separate samples.

MPTMS-modified particles were doped into polyurethanes at concentrations of 20 wt%.

Geometric size estimated from scanning electron micrographs of particles (n>100 individual particles).

Determined by ICP-OES measurement of [Si] from membrane soak solutions after 7 d incubation in PBS.

The above RSNO particle experiments were carried out using membranes in which the total particle composition was 20 wt%. For N-diazeniumdiolate-doped materials, increasing the SNP mass contribution to >20 wt% generally resulted in a larger degree of particle leaching. For example, 800 nm DET/NO particles doped into SG-85A PU at 33.3 and 50.0 wt% leached 38.7 and 76.8%, of the encapsulated silica, respectively, over a 1 wk period. In contrast, membranes prepared using 75% MPTMS/TEOS particles at the same concentrations (33.3 and 50.0 wt%) leached minimal amounts of silica when immersed in aqueous buffer. Even at the highest concentration tested (50.0 wt%), particle leaching was measured just above the instrument limit of detection at 28.1 µg cm−2, corresponding to <1 % of the silica doped into the PU membrane.

Nitric oxide release from S-nitrosothiol-based polyurethane/silica composite membranes

S-nitrosothiols decompose to yield NO through multiple mechanisms. Both light (330–350 and 550–600 nm for primary RSNOs) and thermal irradiation cause homolytic scission of the S-N bond to yield NO and thiyl radicals. Subsequent reaction of the thiyl radical with a second RSNO can also trigger release, generating a disulfide and an additional mole of NO. RSNO donors may also undergo irreversible catalytic redox reactions with several transition metal ions (Cu2+, Ag+, and Hg2+) to liberate NO.50 Although these RSNO decomposition pathways are well known, in vivo NO release is triggered thermally or through thiyl-mediated mechanisms only, due to the absence of light and presence of only trace amounts of transition metal ions in physiologic fluids. As such, all NO release evaluations were carried out in a light-shielded sample flask and in PBS supplemented with DTPA (a metal chelator) to most accurately recapitulate physiologic conditions.

The NO release from 75% MPTMS-doped membranes varied considerably between the different PU compositions (Table 3). Membranes prepared using either AL-25–80A or PC-3585A released large initial NO fluxes (432 and 301 pmol cm−2 s−1, respectively) and exhausted their NO supply rapidly (half-life of NO release <0.5 h). The release of NO from both films was limited to 24 h. In contrast, 75% MPTMS-doped HP-93A-100 membranes released NO more slowly (t1/2 3.13 h) for 38 h. The differences in NO-release kinetics was attributed to a cage effect that the polymer matrix imposes on immobilized RSNOs.51 This microenvironment surrounding the RSNO species dictates the rates of reversible RSNO decomposition (homolytic cleavage of the S-N bond) and recombination between the resulting thiyl radicals and NO.51–52 In aqueous solutions, NO readily escapes the surrounding solvent cage upon RSNO decomposition, thus mitigating recombination between the thiyl radicals and NO. Slower RSNO decomposition rates have been previously reported in polymer matrices (e.g., polyethylene glycol, Pluronic F127) that are capable of facilitating enhanced geminate recombination (related to a more viscous polymer microenvironment) relative to analogous recombination rates in solution.53–54

Table 3.

Particle leaching and nitric oxide release measurements for PU membranes doped with 75 mol% MPTMS/TEOS particles.a,b

| PU Type | [NO]maxc (pmol cm−2 s−1) | [NO]td (µmol cm−2) | t1/2e (h) | tdf (h) | Leachingg (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP-93A-100 | 277±21 | 0.70±0.04 | 3.13±0.17 | 38.0±4.5 | <0.6 |

| AL-25–80A | 432±12 | 0.43±0.02 | 0.38±0.02 | 21.2±1.2 | <0.6 |

| PC-3585A | 301±16 | 0.48±0.09 | 0.30±0.03 | 8.3±1.1 | <0.6 |

Error bars represent standard deviation for n≥3 separate samples.

75% MPTMS/TEOS particles were doped into polyurethanes at concentrations of 20 wt%.

Maximum initial NO surface flux.

Total NO storage determined by integration of the NO-release profile measured via chemiluminescence.

Half-life of NO release.

Duration of NO release above 1 pmol cm−2 s−1.

Determined by ICP-OES measurement of [Si] from membrane soak solutions after 7 d incubation in PBS.

Following this rationale, NO was detected for extended periods of time for the most hydrophilic (i.e., greatest water uptake) HP-93A-100 membrane, with successive decreases in NO-release half-lives/durations in PUs with lower water uptake (AL-25–80A and PC-3585A). The total NO storage (0.43–0.70 µmol NO cm−2) was roughly an order of magnitude lower than expected, indicating that the majority of the NO is either not released from the films or is being released at fluxes below the detection limit of the NO analyzer (0.8 pmol cm−2 s−). Indeed, the membranes retained a characteristic pink hue upon removal from the NO analysis flask, confirming unreacted primary RSNOs.

Analytical performance of nitric oxide-releasing electrochemical glucose biosensors

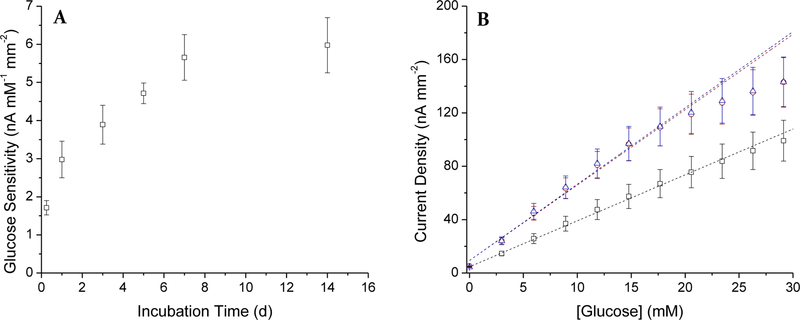

Of the polyurethanes tested, HP-93A-100 was unique in that the RSNO particle-doped membranes had the longest NO-release durations and adequate water uptake (2.6 mg H2O per mg PU) to facilitate glucose partitioning into the PU. Functional glucose sensors were fabricated using HP-93A-100 doped with 75% MPTMS particles. The analytical performance of the sensors was not appreciably altered by the mass percentage of particles in the final coating (11.1–50.0 wt% SNPs). Indeed, the sensitivity to glucose was in the range of 53–71 nA mM−1 mm−2 regardless of the MPTMS content in the membrane. Particles were thus doped in the HP-93A membranes at 33.3 wt% for subsequent experiments to facilitate adequate NO storage (2.85 µmol NO cm−2).

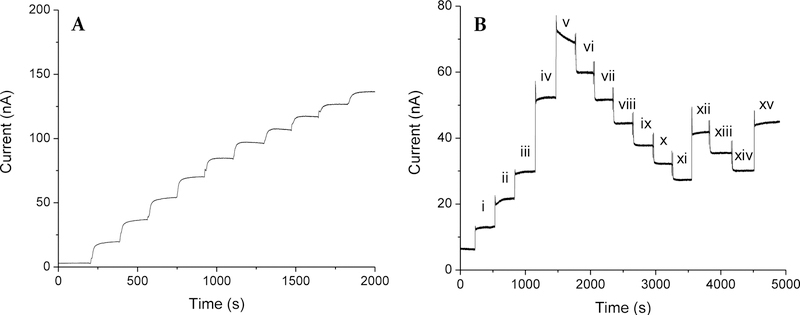

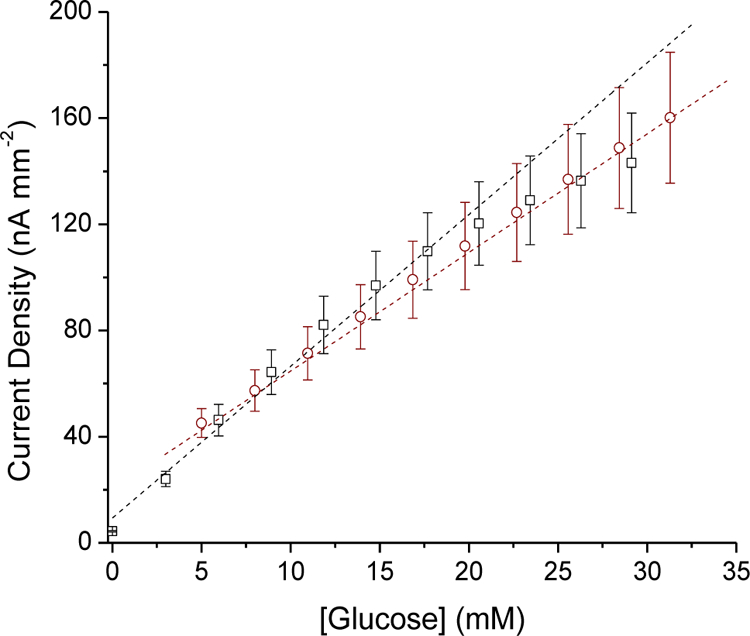

The linear glucose response range of the sensors (HP-93A-100 with 33.3 wt% MPTMS) proved inadequate (6 mM upper limit; Figure S7), and similar to sensors coated solely with HP-93A-100 (i.e., without particles, Table 1). An inverse relationship between sensitivity and dynamic range is often noted upon enzyme saturation by glucose and insufficient oxygen (co-substrate) concentrations. In order to extend the dynamic range of the sensors to capture physiological concentrations (1–15 mM),43 an additional external PC-3585A coating was applied to the sensor electrodes. This PC-3585A “topcoat” served to obstruct glucose diffusion to the immobilized enzyme, balancing the effective glucose and oxygen concentrations in the enzyme layer and extending the glucose linear dynamic range to 30 mM (Figure 2A). The sensors also proved capable of accurately tracking both increasing and decreasing glucose concentrations (Figure 2B), necessary for proper in vivo function. Although the PC-3585A topcoat reduced the glucose sensitivity relative to sensors prepared with solely the NO-releasing HP-93A-100 layer (2.89±1.65 versus ~57 nA mM−1 mm−2), the measured sensitivity was comparable to other in vivo glucose sensors (2.5–7.5 nA mM−1 mm−2).27–28

Figure 2.

(A) Amperometric glucose response for sensors coated with 75 mol% MPTMS/TEOS-doped HP-93A-100 (33.3 wt% SNP) and an additional PC-3585A topcoat in PBS at 37 °C. Glucose concentrations were increased in 3 mM increments to cover physiological concentrations (3–30 mM). (B) Sensor response to increasing and decreasing glucose concentrations of (i) 1.00, (ii) 2.00, (iii) 2.99, (iv) 5.96, (v) 8.62, (vi) 7.40, (vii) 6.18, (viii) 5.16, (ix) 4.31, (x) 3.60, (xi) 3.00, (xii) 4.98, (xiii) 4.16, (xiv) 3.47, and (xv) 5.45 mM glucose.

A pre-conditioning period in the sensing medium (e.g., PBS) was necessary for all sensors to initiate sensor membrane hydration and stabilize the electrical double-layer charging current. For control sensors (i.e., sensors coated with non-NO-releasing particles), a minimum electrode polarization period of 4–5 h in PBS (37 °C) was sufficient, as evidenced by the low baseline current drift (<0.5 nA h−1; Figure 3A). For the NO-releasing sensors, an anodic peak current was observed in the background sensor response due to NO oxidation, a feature that was absent for the control sensors. The slight response of the sensor to NO was mitigated at the working potential of +0.600 V as NO oxidation occurs more readily at higher electrode potentials (~+0.9 V versus +0.7 V for H2O2 on platinum surfaces).36,55 Indeed, stable current backgrounds (<0.4 nA h−1 I0) were achieved for the NO-releasing sensors after 6–8 h (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) Amperometric response for sensors coated with the 75 mol% MPTMS/TEOS-doped HP-93A-100 (33.3 wt% SNP) layer and PC-3585A topcoat upon immersion in PBS at 37 °C. A peak in the anodic current profile was observed for NO-releasing (solid line) but not control (dashed line) sensors. A stable background current was achieved after 8 h polarization at +0.600 V vs Ag|AgCl (B).

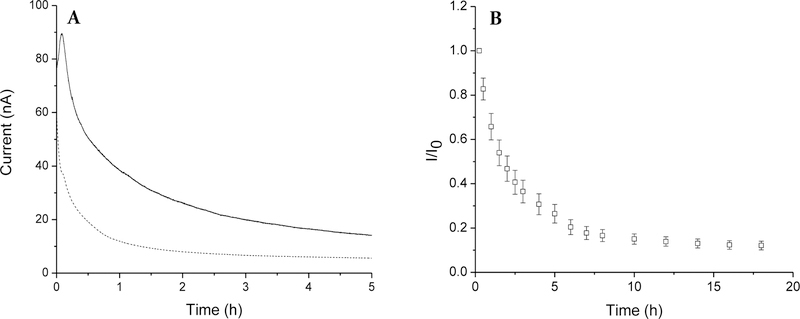

Although the glucose sensitivity of the biosensors coated solely with PU (i.e., without SNPs) gradually decreased during 7 d incubation in PBS (Table 1), the sensitivity of the particle-modified sensors (both NO-releasing and control) increased over the same period, remaining constant thereafter (Figure 4A). The selectivity coefficients of the NO-releasing sensor against acetaminophen, ascorbate, and nitrite on the first day of testing were 1.64±0.19, −0.29±0.23, and 0.56±0.18, respectively. This performance did not vary discernably throughout the incubation period (data not shown), indicating that the relative permeabilities of both glucose and the interfering species remained constant. The gradual change in amperometric glucose response was accompanied by enzyme saturation and reduced linear dynamic range (1–21 mM; Figure 4B), yet the glucose response range still covered relevant physiological glucose concentrations. Electron microscopy revealed that the particles sequestered into aggregates after 2 wk incubation in buffer, even though the particles were homogeneously dispersed in the PU originally (Figure S8). The induced particle aggregation may be responsible for the increasing rather than decreasing glucose sensitivity.

Figure 4.

Amperometric glucose response of sensors coated with the 75% MPTMS/TEOS-doped HP-93A-100 (33.3 wt% SNP) NO-releasing layer and PC-3585A topcoat over 2 wk incubation in PBS at 37 °C. (A) glucose sensitivity after incubation in PBS and (B) calibrated glucose response for NO-releasing sensors after 1 (black, square), 7 (red, circle), and 14 d (blue, triangle) immersion in PBS. The glucose response was linear over 1–30 mM initially (1 d), with decreased upper limit (21 mM) after 1 wk.

The glucose biosensors experienced a perceptible decrease in glucose sensitivity (~68%) upon testing in porcine serum (3.82±2.22 nA mM−1mm−2) relative to PBS (5.62±2.73 nA mM−1 mm−2), with no further change in response through 6 h continuous operation in serum (3.78±2.49 nA mM−1 mm−2; Figure 5). Reduced glucose permeability is a well-known consequence of protein adhesion to the sensor surface in complex biological media (e.g., serum, blood).11 The lower sensitivity was accompanied by an extended upper limit of glucose quantification (>32 mM) due to the additional diffusion barrier posed by the adhered proteins. Following exposure to serum, the glucose sensitivity in PBS returned to ~88.7% of the original value (i.e., 5.62 nA mM−1mm−2), indicating the loss in analytical response was partially reversible.

Figure 5.

Calibrated glucose response of sensors coated with both the 75% MPTMS/TEOS-doped HP-93A-100 (33.3 wt% SNP) NO-releasing layer and the PC-3585A topcoat in PBS (black, square) and serum (red, circle) at 37 °C.

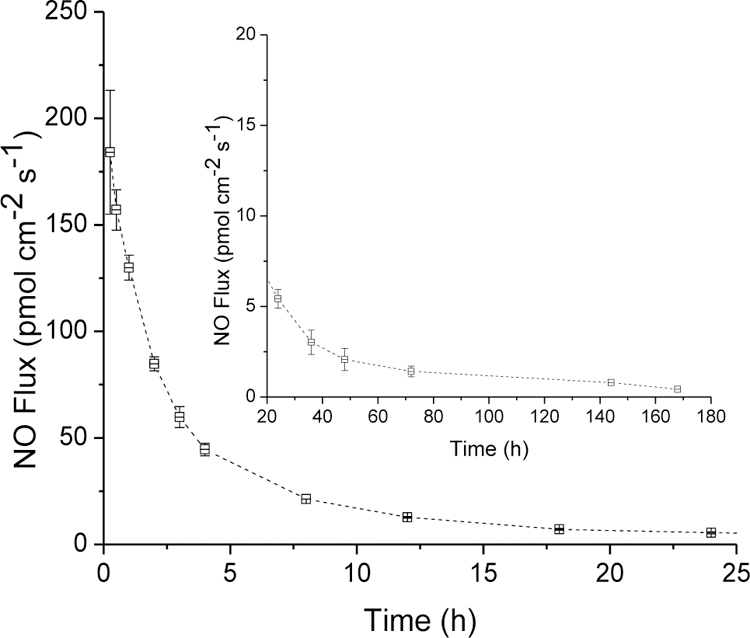

The NO-releasing glucose sensors with a PC-3585A topcoat released NO for at least 7 d as measured by chemiluminescence (Figure 6) and the Griess assay, a technique that facilitates the quantification of lower NO fluxes (0.8 pmol cm−2 s−1) indirectly via oxidative scavenging and accumulation as nitrite.56 This NO-release duration represents a three-fold increase over that used for a recent study investigating the in vivo analytical performance benefits of NO-releasing glucose sensors (NO fluxes ≥0.8 pmol cm−2 s−1 for <48 h).27–28 As such, the NO-release properties (fluxes) of the sensors described herein are in line with levels expected to improve long-term in vivo sensor function.26

Figure 6.

Nitric oxide release from HP-93A-100 membranes doped with 75 mol% MPTMS/TEOS particles (33.3 wt%) with an additional PC-3585A topcoat. Inset shows the low NO fluxes released from sensor membranes at durations beyond 24 h.

CONCLUSIONS

Nitric oxide release from polymeric membranes is a demonstrated strategy to improve both the biocompatibility and in vivo performance of glucose biosensors.24,26–28 Despite the promising preclinical data, NO donor leaching and limited NO-release capacities may hinder implementation. The results presented herein indicate that the leaching of entrapped NO donors must be evaluated with due caution. Silica particles functionalized with N-diazeniumdiolate NO donors leach indiscriminately from many biomedical-grade polyurethanes barring the most hydrophobic composites, but unfortunately such membranes are not compatible with electrochemical glucose biosensors due to insufficient glucose permeability. The underpinnings of the leaching process involve the total particle electrical charge and surface hydrophobicity. Silica particles modified with neutral RSNO donors are more stable (i.e., minimal or no leaching) in a wide selection of polyurethanes, provided that the degree of organic modification of the particles is substantial (>75% MPTMS). Polyurethane membranes doped with MPTMS particles yielded glucose biosensors with attractive analytical performance merits and NO-release durations. The extended NO-releasing sensors developed here hold promise for mitigating the FBR and improving in vivo sensor functional lifetimes. Studies evaluating in vivo sensor performance using these sensors are currently underway.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr. Wallace Ambrose and Dr. Amar Kumbhar for technical assistance with electron microscopy. This work was performed in part at the Chapel Hill Analytical and Nanofabrication Laboratory (CHANL), a member of the North Carolina Research Triangle Nanotechnology Network (RTNN), which is supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant ECCS-1542015) as part of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NNCI). RJS gratefully acknowledges a John Motley Morehead dissertation fellowship from the UNC Royster Society of Fellows.

Funding Sources

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (DK108318) and the National Science Foundation (DMR 1104892).

ABBREVIATIONS

- AHAP

N-(6-aminohexyl)-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane

- CTAB

cetyltrimethylammonium bromide

- FBR

foreign body response

- DET

3-(trimethoxysilylpropyl)diethylenetriamine

- GOx

glucose oxidase

- ICP-OES

inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry

- MPTMS

3-mercaptopropyltrimethoxysilane

- m-PD

meta-phenylenediamine

- MAP

N-methylaminopropyltrimethoxysilane

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOA

nitric oxide analyzer

- PBS

phosphate buffered Saline

- PU

polyurethane

- RSNO

S-nitrosothiol

- SNP

silica nanoparticle

- TEOS

tetraethylorthosilicate

- TMOS

tetramethylorthosilicate

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Synthesis protocols for nitric oxide-releasing nanoparticles, nitric oxide donor-modified organosilane structures, scanning electron micrographs of SNPs and coating surfaces, particle leaching measurements, photographs of aqueous particle solutions, SNP reaction parameters. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The corresponding author declares the following competing financial interest(s): Mark Schoenfisch maintains financial interest in Clinical Sensors, Inc and Novan, Inc. Clinical Sensors is developing NO-releasing sensor membranes for continuous glucose monitoring devices. Novan is commercializing NO-releasing macromolecular vehicles for dermatological indications.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Diabetes Statistics Report. Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Diabetes Data Group. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus and Other Categories of Glucose Intolerance. Diabetes 1979, 28, 1039–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Group; the Effect of Intensive Treatment of Diabetes on the Development and Progression of Long-Term Complications in Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993; 329, 977–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nichols SP.; Koh A.; Storm WL.; Shin JH.; Schoenfisch MH. Biocompatible Materials for Continuous Glucose Monitoring Devices. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 2528–2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benhamou PY.; Catargi B.; Delenne B.; Guerci B.; Hanaire H.; Jeandidier N.; Leroy R.; Meyer L.; Penfornis A.; Radermecker RP.; Renard E.; Baillot-Rudoni S.; Riveline JP.; Schaepelynck P.; Sola-Gazagnes A.; Sulmont V.; Tubiana-Rufi N.; Durain D.; Mantovani I.; Sola-Gazagnes A.; Riveline JP. Real-Time Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) Integrated into the Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes: Consensus of Experts from SFD, EVADIAC and SFE. Diabetes Metab. 2012, 38, Supplement 4, S67–S83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radermecker RP.; Saint Remy A.; Scheen AJ.; Bringer J.; Renard E. Continuous Glucose Monitoring Reduces Both Hypoglycaemia and Hba1c in Hypoglycaemia-Prone Type 1 Diabetic Patients Treated with a Portable Pump. Diabetes Metab. 2010, 36, 409–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson JM. Biological Responses to Materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2001, 31, 81–110. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson JM.; Rodriguez A.; Chang DT. Foreign Body Reaction to Biomaterials. Sem. Immunol. 2008, 20, 86–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenneth Ward W. A Review of the Foreign-Body Response to Subcutaneously-Implanted Devices: The Role of Macrophages and Cytokines in Biofouling and Fibrosis. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2008, 2, 768–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koh A.; Nichols SP.; Schoenfisch MH. Glucose Sensor Membranes for Mitigating the Foreign Body Response. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2011, 5, 1052–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomé-Duret V.; Gangnerau MN.; Zhang Y.; Wilson GS.; Reach G. Modification of the Sensitivity of Glucose Sensor Implanted into Subcutaneous Tissue. Diabetes Metab. 1996, 22, 174–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams DF. On the Mechanisms of Biocompatibility. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2941–2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sussman EM.; Halpin MC.; Muster J.; Moon RT.; Ratner BD. Porous Implants Modulate Healing and Induce Shifts in Local Macrophage Polarization in the Foreign Body Reaction. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2014, 42, 1508–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang S.; Cao Z. Ultralow-Fouling, Functionalizable, and Hydrolyzable Zwitterionic Materials and Their Derivatives for Biological Applications. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 920–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang W.; Xue H.; Carr LR.; Wang J.; Jiang S. Zwitterionic Poly(Carboxybetaine) Hydrogels for Glucose Biosensors in Complex Media. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 26, 2454–2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L.; Cao Z.; Bai T.; Carr L.; Ella-Menye JR.; Irvin C.; Ratner BD.; Jiang S. Zwitterionic Hydrogels Implanted in Mice Resist the Foreign Body Reaction Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 553–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vallejo-Heligon SG.; Brown NL.; Reichert WM.; Klitzman B. Porous, Dexamethasone-Loaded Polyurethane Coatings Extend Performance Window of Implantable Glucose Sensors in Vivo Acta Biomater. 2016, 30, 106–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vacanti NM.; Cheng H.; Hill PS.; Guerreiro JDT.; Dang TT.; Ma M.; Watson S.; Hwang NS.; Langer R.; Anderson DG. Localized Delivery of Dexamethasone from Electrospun Fibers Reduces the Foreign Body Response. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 3031–3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norton LW.; Koschwanez HE.; Wisniewski NA.; Klitzman B.; Reichert WM. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Dexamethasone Release from Nonfouling Sensor Coatings Affect the Foreign Body Response. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2007, 81, 858–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacMicking J.; Xie QW.; Nathan C. Nitric Oxide and Macrophage Function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997, 15, 323–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witte MB.; Barbul A. Role of Nitric Oxide in Wound Repair. Am. J. Surg. 2002, 183, 406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooke JP.; Losordo DW. Nitric Oxide and Angiogenesis. Circulation 2002, 105, 2133–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carpenter AW.; Schoenfisch MH. Nitric Oxide Release: Part II. Therapeutic Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3742–3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hetrick EM.; Prichard HL.; Klitzman B.; Schoenfisch MH. Reduced Foreign Body Response at Nitric Oxide-Releasing Subcutaneous Implants. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 4571–4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nichols SP.; Le NN.; Klitzman B.; Schoenfisch MH. Increased in Vivo Glucose Recovery Via Nitric Oxide Release Anal Chem 2011, 83, 1180–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nichols SP.; Koh A.; Brown NL.; Rose MB.; Sun B.; Slomberg DL.; Riccio DA.; Klitzman B.; Schoenfisch MH. The Effect of Nitric Oxide Surface Flux on the Foreign Body Response to Subcutaneous Implants. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 6305–6312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gifford R.; Batchelor MM.; Lee Y.; Gokulrangan G.; Meyerhoff ME.; Wilson GS. Mediation Of In Vivo Glucose Sensor Inflammatory Response Via Nitric Oxide Release. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2005, 75A, 755–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soto RJ.; Privett BJ.; Schoenfisch MH. In Vivo Analytical Performance of Nitric Oxide-Releasing Glucose Biosensors. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 7141–7149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koh A.; Carpenter AW.; Slomberg DL.; Schoenfisch MH. Nitric Oxide-Releasing Silica Nanoparticle-Doped Polyurethane Electrospun Fibers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 7956–7964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wo Y.; Li Z.; Brisbois EJ.; Colletta A.; Wu J.; Major TC.; Xi C.; Bartlett RH.; Matzger AJ.; Meyerhoff ME. Origin of Long-Term Storage Stability and Nitric Oxide Release Behavior of Carbosil Polymer Doped with S-Nitroso-N-Acetyl-D-Penicillamine. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 22218–22227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Worley BV.; Soto RJ.; Kinsley PC.; Schoenfisch MH. Active Release of Nitric Oxide-Releasing Dendrimers from Electrospun Polyurethane Fibers. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 426–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jun HW.; Taite LJ.; West JL. Nitric Oxide-Producing Polyurethanes. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 838–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taite LJ.; Yang P.; Jun HW.; West JL. Nitric Oxide-Releasing Polyurethane-PEG Copolymer Containing the YIGSR Peptide Promotes Endothelialization with Decreased Platelet Adhesion. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B 2008, 84, 108–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Backlund CJ.; Worley BV.; Sergesketter AR.; Schoenfisch MH. Kinetic-Dependent Killing of Oral Pathogens with Nitric Oxide. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 1092–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carpenter AW.; Johnson JA.; Schoenfisch MH. Nitric Oxide-Releasing Silica Nanoparticles with Varied Surface Hydrophobicity. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 454, 144–151. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koh A.; Riccio DA.; Sun B.; Carpenter AW.; Nichols SP.; Schoenfisch MH. Fabrication of Nitric Oxide-Releasing Polyurethane Glucose Sensor Membranes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 28, 17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soto RJ.; Yang L.; Schoenfisch MH. Functionalized Mesoporous Silica Via an Aminosilane Surfactant Ion Exchange Reaction: Controlled Scaffold Design and Nitric Oxide Release. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 2220–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frost MC.; Reynolds MM.; Meyerhoff ME. Polymers Incorporating Nitric Oxide Releasing/Generating Substances for Improved Biocompatibility of Blood-Contacting Medical Devices. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 1685–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen G.; Roy I.; Yang C.; Prasad PN. Nanochemistry and Nanomedicine for Nanoparticle-Based Diagnostics and Therapy. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2826–2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kusaka T.; Nakayama M.; Nakamura K.; Ishimiya M.; Furusawa E.; Ogasawara K. Effect of Silica Particle Size on Macrophage Inflammatory Responses. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waters KM.; Masiello LM.; Zangar RC.; Tarasevich BJ.; Karin NJ.; Quesenberry RD.; Bandyopadhyay S.; Teeguarden JG.; Pounds JG.; Thrall BD. Macrophage Responses to Silica Nanoparticles Are Highly Conserved across Particle Sizes. Toxicol. Sci. 2009, 107, 553–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riccio DA.; Nugent JL.; Schoenfisch MH. Stöber Synthesis of Nitric Oxide-Releasing S-Nitrosothiol-Modified Silica Particles. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 1727–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bindra DS.; Zhang Y.; Wilson GS.; Sternberg R.; Thevenot DR.; Moatti D.; Reach G. Design and In Vitro Studies of a Needle-Type Glucose Sensor for Subcutaneous Monitoring. Anal. Chem. 1991, 63, 1692–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koh A.; Lu Y.; Schoenfisch MH. Fabrication of Nitric Oxide-Releasing Porous Polyurethane Membranes-Coated Needle-Type Implantable Glucose Biosensors. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 10488–10494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen X.; Matsumoto N.; Hu Y.; Wilson GS. Electrochemically Mediated Electrodeposition/Electropolymerization to Yield a Glucose Microbiosensor with Improved Characteristics. Anal. Chem. 2002, 74, 368–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shin JH.; Marxer SM.; Schoenfisch MH. Nitric Oxide-Releasing Sol-Gel Particle/Polyurethane Glucose Biosensors. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 4543–4549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ward WK.; Jansen LB.; Anderson E.; Reach G.; Klein JC.; Wilson GS. A New Amperometric Glucose Microsensor: In Vitro and Short-Term In Vivo Evaluation. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2002, 17, 181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zdrahala RJ.; Zdrahala IJ. Biomedical Applications of Polyurethanes: A Review of Past Promises, Present Realities, and a Vibrant Future. J. Biomater. Appl. 1999, 14, 67–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaddiraju S.; Wang Y.; Qiang L.; Burgess DJ.; Papadimitrakopoulos F. Microsphere Erosion in Outer Hydrogel Membranes Creating Macroscopic Porosity to Counter Biofouling-Induced Sensor Degradation. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 8837–8845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCarthy CW.; Guillory RJ II.; Goldman J.; Frost MC. Transition Metal Mediated Release of Nitric Oxide (NO) from S-Nitroso-N-Acetylpenicillamine: Potential Applications for Endogenous Release of NO on the Surface of Stents Via Corrosion Products. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 10128–10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Oliveira MG.; Shishido SM.; Seabra AB.; Morgon NH. Thermal Stability of Primary S-Nitrosothiols: Roles of Autocatalysis and Structural Effects on the Rate of Nitric Oxide. Release J. Phys. Chem. A 2002, 106, 8963–8970. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adachi H.; Sonoki H.; Hoshino M.; Wakasa M.; Hayashi H.; Miyazaki Y. Photodissociation of Nitric Oxide from Nitrosyl Metalloporphyrins in Micellar Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 392–398. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shishido SM.; de Oliveira MG. Polyethylene Glycol Matrix Reduces the Rates of Photochemical and Thermal Release of Nitric Oxide from S-Nitroso-N-Acetylcysteine. Photochem. Photobiol. 2000, 71, 273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shishido SM.; Seabra AB.; Loh W.; Ganzarolli de Oliveira M. Thermal and Photochemical Nitric Oxide Release from S-Nitrosothiols Incorporated in Pluronic F127 Gel: Potential Uses for Local and Controlled Nitric Oxide Release. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 3543–3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Privett BJ.; Shin JH.; Schoenfisch MH. Electrochemical Nitric Oxide Sensors for Physiological Measurements. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1925–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hetrick EM.; Schoenfisch MH. Analytical Chemistry of Nitric Oxide. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2009, 2, 409–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.