Abstract

Introduction

The detection rate of somatic symptom disorder (SSD) in general hospitals is unsatisfactory. Self-report questionnaires that assess both somatic symptoms and psychological characteristics will improve the process of screening for SSD. The Somatic Symptom Scale-China (SSS-CN) questionnaire has been developed to meet this urgent clinical demand. The aim of this research is to validate the self-reported SSS-CN as a timely and practical instrument that can be used to identify SSD and to assess the severity of this disorder.

Methods and analysis

At least 852 patients without organic disease but presenting physical discomfort will be recruited at a general hospital. Each patient will undergo a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5)-guided physician diagnosis, including disease identification and severity assessment, as the reference standard. This research will compare the diagnostic performance of the SSS-CN for SSD, the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) and other SSD-related questionnaires. Statistical tests to measure the area under the curve (AUC) and volume under the surface of the receiver operating curve will be used to assess the accuracy of the SSD identification and the severity assessment, respectively. In addition to this standard diagnostic study, we will conduct follow-up investigations to explore the effectiveness of the SSS-CN in monitoring treatment effects.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was obtained from the Renji Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee, approval number 2 015 016. The findings of this study will be disseminated via peer-reviewed journals and presented at international conferences.

Trial registration number

Keywords: somatic symptom scale-china, somatic symptom disorder, mental disorders management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The Somatic Symptom Scale-China (SSS-CN) questionnaire is developed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, and its clinical utility is evaluated herein for the first time.

The SSS-CN will benefit patients by improving their awareness of SSD and their ability to self-monitor their symptoms.

The SSS-CN will provide clinicians with an easy-to-use tool that can be completed quickly and assess both somatic and psychological components.

Referral bias may be present in this study, as only patients without organic disease will be referred to our special clinic.

Treatment effect monitoring will be affected by the bias due to non-random loss to follow-up.

Introduction

Somatic symptom disorder (SSD)1 2 is a common medical condition observed in general hospitals. SSD is characterised by symptoms that are often difficult to explain after adequate evaluation3; even when a significant medical disease is present, the patients’ symptoms may nonetheless be unrelated to their disease.2 The diagnosis of SSD emphasises the existence of symptoms and signs (one or multiple somatic symptoms, and abnormal thoughts, feelings and behaviours in response to these symptoms).2 The current prevalence of this disorder is estimated to be 5%–7%2 in the general population, and it may be even higher in Asian individuals.4

In general hospitals, the detection rate of SSD is unsatisfactory due to the diagnostic complexity of the disease and the lack of adequate training for physicians to evaluate patients with suspected SSD. Therefore, patients may sustain somatic symptoms without appropriate treatment due to the unawareness of SSD. The yearly cost of medical care among patients with somatisation is nearly twice as high as the yearly cost among patients without somatisation. An estimated $256 billion in annual medical care costs is attributable to the incremental effects of somatisation alone.1 Hence, it is highly important that physicians are trained to identify SSD, assess the symptom severity and treat it in a timely manner; failure to do so can result in high morbidity, lost productivity and overutilisation of medical resources.5 6 However, compared with widely researched disorders such as depression and anxiety, SSD has been far less studied. Follow-up or treatment studies of this disorder are even scarcer.

It is more favourable to have a tool for screening patients suspected of having SSD via accurate and brief diagnostic questionnaires and to facilitate daily clinical work. One of the aims of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) is to identify patients with SSD and to assess the severity of the disorder.2 The DSM-5 states that SSD comorbid with anxiety and depressive disorder (a combination present in approximately 57.7% of patients with SSD)1 adds severity and complexity to the somatic components. The DSM-5 emphasises that it is important to evaluate patients in terms of their psychological situation, behaviour and physical condition altogether and then treat the patients according to the severity of the disorder. Furthermore, the DSM-5 emphasises the evaluation of subjects who have excessive concerns about health issues. However, the DSM-5 is clinically difficult to follow because it requires qualified and experienced physicians to conduct an interview,7 which makes clinicians in general hospitals feel less confident when treating patients who are suspected to have SSD. In particular, individuals in China and other Asian countries tend to refuse psychological counselling 4 8; thus, many patients with psychological symptoms have been treated by non-psychiatric physicians in general medical hospitals. A series of studies has focused on this issue; the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) and the Somatic Symptom Scale-8 are screening tools for SSD9 10; however, these self-report questionnaires do not assess psychological features. The Whiteley Index-7 focuses on health anxiety11; the Scale for the Assessment of Illness Behavior questionnaires focuses on excessive illness behaviour; and the Somatic Symptom Scale-12 assesses psychological features.12 13 The latter three questionnaires focus less on physical features. Recent studies, including one by Laferton et al,14 have indicated that self-report measures that focus on different aspects could increase diagnostic quality in clinical practice.

Based on published studies, we aim to develop a comprehensive questionnaire to assess somatic symptoms of SSD comorbid with anxiety and depression symptoms. The Somatic Symptom Scale-China (SSS-CN) questionnaire was developed based on the DSM-5. The questionnaire assesses a combination of psychological, behavioural and somatic symptoms. The questionnaire was designed for use in general medical facilities and to provide clinicians with an easy-to-use questionnaire for detecting both somatic and psychological features in a timely manner.

Study objectives and research questions

Primary objective

The primary objective of this study is to test two aspects of the diagnostic accuracy of the SSS-CN compared with the PHQ-15, with a DSM-5-guided physician diagnosis as the reference standard: (1) the accuracy for identifying SSD and (2) the accuracy for assessing SSD severity.

Secondary objective

The secondary objective is to explore the potential utility of the SSS-CN in monitoring the treatment effect. We aim to examine how the scores of the SSS-CN and other questionnaires change over time after treatment.

Methods

Study overview

This study will use a prospective diagnostic design and will be conducted at a tertiary general hospital in Shanghai, China. Written informed consent will be obtained from all study participants. The clinical trial registration can be found at https://register.clinicaltrials.gov/.

Particular attention will be paid to the appropriate storage of the data. Patient confidentiality will be maintained, and no identifying characteristics of the patients will be published. The protocol development will adhere to the European Medicines Agency guidelines for diagnosis study.15

Description of the SSS-CN and assessment of severity

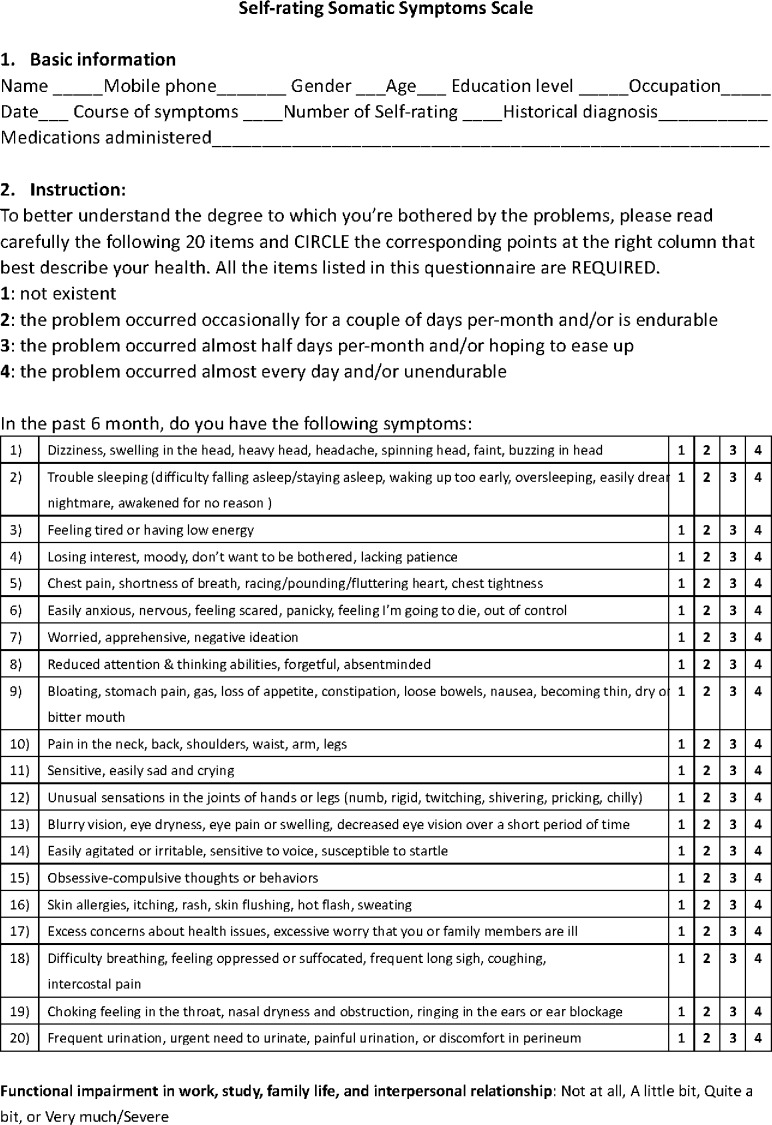

The SSS-CN is a somatic and psychological symptom scale (figure 1) derived from the DSM-5. It is designed to assess the presence and severity of the symptoms. We validated its reliability and validity in a previous study.16 The test–retest reliability was 0.9. The correlation coefficients between each dimension and the total ranged from 0.76 to 0.88, and the correlation coefficients within dimensions ranged from 0.56 to 0.70.

Figure 1.

The Somatic Symptom Scale-China.

The questionnaire is self-administered with an abbreviated 20-item measure. Briefly, in the previous study, the SSS-CN was composed of four dimensions: physical disorder, anxiety disorder, depression disorder and anxiety and depression disorder. Half of the items ask about physical complaints (one item per body system, items 1, 5, 9, 10, 12, 13, 16 and 18–20). The remaining items ask about anxiety and depression (anxiety items 6, 14, 15 and 17; depression items 3, 4, 7 and 11; and anxiety and depression items 2 and 8). Subjects answer the following question: ‘Since you have felt unwell, how often have you been bothered in the previous 6 months by any of the following problems?’. For scoring, the subjects rate the frequency of each symptom using the following response options: 1 (‘does not exist’), 2 (‘the problem occurred occasionally for a couple of days per month and/or is endurable’), 3 (‘the problem occurred almost half of the days per month and/or I hope it will ease up’) or 4 (‘the problem occurred almost every day and/or is unendurable’). Thus, in determining the SSS-CN score, each question has a score ranging from 1 to 4, corresponding to the frequency of the problem occurrence, and the total score ranges from 20 to 80. The severity of SSD is determined based on the sum of the scores. SSS-CN scores ranging from 20 to 29, 30–39, 40–59 and ≥60 correspond to normal, mild, moderate and severe SSD, respectively. The selection of the cut-off value of 30 is based on the results of our previous study (it was obtained from the receiver operating curve (ROC), reaching a sensitivity of 0.97 and a specificity of 0.96).16 Other cut-offs (40,60) are chosen based on clinical experience rather than previous research.

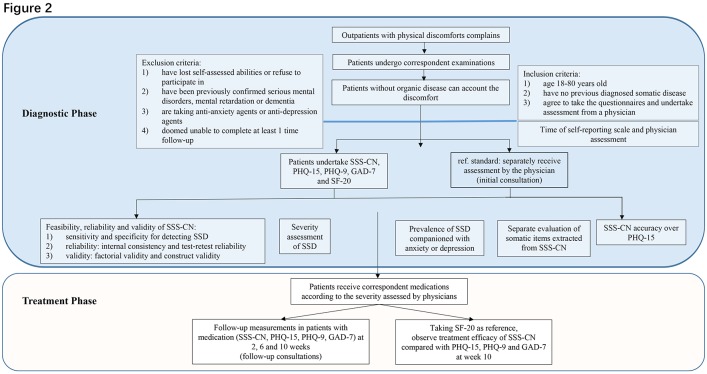

Study design

The study is composed of two stages (figure 2) corresponding to the primary and secondary research objectives. The first stage is a prospective diagnostic stage to assess the diagnostic performance of the SSS-CN questionnaire. The second stage is an exploratory follow-up stage that uses the SSS-CN questionnaire as a tool to monitor treatment effects.

Figure 2.

Study flow. GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale-7; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PHQ-15, Patient Health Questionnaire-15; SF-20, 20-item Short Form Health Survey; SSD, somatic symptom disorder; SSS-CN, somatic symptom scale-China.

Briefly, consecutive outpatients with physical discomfort presenting to internal medicine departments in a tertiary hospital in China will first undergo the corresponding examination to exclude organic disease. For example, a patient with chest pain will be recommended by a physician to receive an electrocardiography, echocardiography, a treadmill test or coronary angiography to exclude cardiovascular disease. Patients with no organic disease that can account for their discomfort will be considered to have a probable psychosomatic disorder. These patients will then be transferred to a specialist clinic for the diagnosis and treatment of suspected SSD (the initial consultation). They will fill out the SSS-CN questionnaire; they will also complete other self-reported instruments, including the PHQ15, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7) and the 20-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-20), to verify the structural validity of SSS-CN. Non-clinical research assistants will collect the questionnaires and calculate the scores. A physician or a psychologist who is blind to the results of the SSS-CN will separately interview the patient to diagnose SSD using the standard interview criteria put forth in the DSM-5. Prescriptions will be given if the patient is diagnosed with SSD. For patients receiving medications, follow-up visits will be scheduled at 2, 6 and 10 weeks to repeat the questionnaires (the follow-up consultation). Because health-related quality of life is often impaired in patients with SSD, the SF-20 will be administered as an indicator of therapeutic effects during follow-up.

Participants and procedure

Inclusion criteria

(1) Patients aged 18–80 years old; (2) patients who have no previous diagnosis of somatic disease; (3) patients without systemic disease that can account for their physical discomfort; and (4) patients enrolled as outpatients after they agree to complete the questionnaires and undergo assessment by a physician.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Patients who have lost their self-assessment ability or refuse to participate; (2) patients who have been confirmed to have mental disorders, mental retardation or dementia; (3) patients who currently take antianxiety agents or antidepression agents; and (4) patients who are unable to complete face-to-face follow-up visits after at least 1 month.

Reference standard

Patients will be interviewed using the standard procedure. The physician will conduct a structured clinical interview (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5-Clinician Version) in accordance with the corresponding DSM-5 criterion. The interview questions include modules from somatic symptom and related disorder to depression disorder, anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive-related disorder and sleep–wake disorders. The interview will last approximately 30–45 min. The physician will assess the severity based on the number of symptoms, that is, excessive thoughts, feelings or behaviours related to the somatic symptoms or associated health concerns (mild: one symptom; moderate: two or more of the symptoms; and severe: two or more of the symptoms plus multiple somatic complaints). The physician assessment will be used as the reference standard. The physician team will be composed of both general hospital ‘specified physicians’ (ie, physicians qualified as national psychological counsellors) and psychologists. When there is diagnostic uncertainty, the patient will be referred to the senior physician to obtain a diagnosis.

Obtaining informed consent

A trained researcher will obtain informed consent and provide all necessary information about this study to the potential participants. It will be made clear to participants that they are under no obligation to take part, their usual care will not be affected by their decision and they can withdraw consent without giving a reason. Participants will be given a sheet with contact details for the research team and instructions on what to do if they wish to withdraw or require further information.

Blinding

After a patient with suspected SSD is transferred to the specialist clinic, the patient will first complete the questionnaires in a separate room, and the research assistant will help the patient understand the questions. Then, an initial consultation will be conducted by a physician who has been qualified as a national psychological counsellor and who has been blinded to the patient’s responses to the SSS-CN. An independent diagnosis and severity assessment will be made by the physician. The durations of the self-reported scale and the physician assessment will be recorded separately.

Medication

The patients will be informed of the results immediately after the physician consultation and the questionnaire. During the follow-up consultations, the patients will be allowed to communicate with the doctor throughout the diagnosis and treatment. Because patients in China usually refuse to accept psychotherapy,4 8 medications will be prescribed according to the physician’s evaluation. Antianxiety treatment or antidepression treatment will be selectively administered according to the severity of the somatic symptoms. Generally, drugs that are classified as thioxanthenes, such as Deanxit, are prescribed for mild symptoms; selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are prescribed for moderate symptoms; and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are prescribed for severe symptoms. Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors are prescribed for sleeping problems.

Follow-up

A face-to-face interview will be scheduled at 2, 6 and 10 weeks for patients taking medication. The patient will complete five questionnaires (SSS-CN, PHQ15, PHQ-9, GAD-7 and SF-20) both at the initial consultation and at the week 10 follow-up. The SF-20 aims to evaluate the respondent’s quality of life. At week 2 and week 6, the patient will complete four questionnaires (SSS-CN, PHQ15, PHQ-9 and GAD-7).

Outcome measures

Reliability and validity

Reliability will be measured by Cronbach’s α. A randomised sample of approximately 100 participants will be asked to complete the questionnaires 1 week after the initial completion to analyse the test–retest reliability.

The criterion validity will be determined by comparing the presence and severity of SSD between the reference standard (physician assessment based on structure interview) and the SSS-CN questionnaire.

The SSS-CN consists of 10 items assessing somatic symptoms, 4 items assessing depression, 4 items assessing anxiety and 2 items assessing depression and anxiety. The construct validity will be tested by confirmatory factor analysis, comparing the corresponding factors with the PHQ-15, PHQ-9 and GAD-7.

Diagnostic performance

The diagnostic accuracy of a questionnaire for SSD identification is measured by the area under the curve (AUC) of an ROC, the sensitivity/specificity under a prespecified cut-off value and the positive/negative predictive values in the study population, using the physician diagnosis as the reference standard. The accuracy of the severity assessment of a questionnaire is measured by the volume under the surface (VUS), which is a multiclass generalisation of AUC of a ROC between the questionnaire score and the physician’s severity assessment.17

Other clinical utilities

Convenience in clinical practice is measured by the average time taken to complete each questionnaire or receive a diagnosis from a physician.

Clinical utility in monitoring treatment efficacy in patients is measured by assessing the correlation with the SF-20 during follow-up visits.

Sample size calculation

The sample size calculation considers the comparison of diagnostic accuracy for both SSD identification and severity assessment, whichever is larger. In the pilot study, the prevalence of SSD was 76.9% among patients who were referred to the special clinics (where physicians qualified as national psychological counsellors and psychologists practice medicine); the AUC of the ROC for the PHQ-15 was 0.88; and the VUS of the multiclass ROC for the PHQ-15 with respect to the severity assessment was 0.7. The correlation between the SSS-CN and PHQ-15 scores was 0.6. With a non-inferiority margin of 0.05, α=0.025 and β=0.8, the sample size for SSD diagnosis was 852. With a non-inferiority margin of 0.1, α=0.025 and β=0.8, the sample size for severity assessment was 517. Therefore, as the overall sample size of this study was n=852 with SSD-positive n+=655 and SSD-negative N−=197, both the positive and negative sample size requirements were met.

Statistical analysis

We will report our results according to Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. We will compute the median (P25, P75) scores for each questionnaire and the number and percentage of patients (%) in each diagnostic category as descriptive statistics.

Reliability will be measured using Cronbach’s α. The criterion validity will be measured by the kappa coefficient between the questionnaire score and the physician assessment. Construct validity will be tested using confirmatory factor analyses.

The primary analysis of the diagnostic performance will consist of two comparisons using Bonferroni’s correction: (1) the non-inferior comparison of the SSS-CN with the PHQ-15 with respect to SSD diagnostic accuracy, as measured by the AUC of the ROC with △=0.05, α=0.025 in the whole study population using Delong’s method18; and (2) severity of PHQ-15 based on scores (normal: 0–4; low: 5–9; medium: 10–14; high: 15–30). SSS-CN scores ranging from 20 to 29, 30–39, 40–59 and ≥60 correspond to normal, mild, moderate and severe SSD, respectively. The non-inferior comparison will also be conducted between the SSS-CN and the PHQ-15 with respect to SSD severity, as measured by the VUS with △=0.1, α=0.025 in the population with a confirmed SSD diagnosis using a Z-test.17 Both comparisons will use the physician’s diagnosis as the reference standard. If neither non-inferiority criterion is met, the corresponding superiority will be tested.

As a secondary analysis, the sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predictive values will also be determined. Prespecified cut-off values will be validated. In the follow-up data, questionnaire scores by time will be demonstrated in a line chart with error bars.

Missing values will be imputed with multiple imputation under the assumption of missing at random.17 Subgroup analysis according to gender and age will also be conducted. All statistical analyses will be performed with R (version 3.5.1)

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients were involved at the design stage of the trial, including ensuring that the content of the SSS-CN questionnaire can be understood and that the length of the consultation time, the manner of notification of the disease condition, the follow-up method and the dissemination of the results are acceptable. Before the formal recruitment started, we received feedback from patients who had SSD during a pretest of the case report form (CRF), and this feedback was used to improve the final design of the CRF. We carefully assessed the burden of the trial interventions on patients. We intend to disseminate the main results to the trial participants via email. The study outcomes will be disseminated in conference reports and academic publications.

Ethics and dissemination

The findings of this study will be disseminated via peer-reviewed journals and presented at international conferences.

Current status

The first study participant was enrolled in November 2017. As of June 2019, patient recruitment has not been completed.

Discussion

In this study protocol, we describe a diagnostic study design that evaluates the efficacy of a newly developed somatic and psychological symptom scale adapted to China for patients with suspected somatic diseases. This scale might be applied as a first-line instrument for screening and monitoring treatment efficacy in individual outpatient consultations. We expect that physicians will benefit from the SSS-CN on a clinically significant level in the form of improved self-confidence and timeliness; participants will benefit from this scale in the form of improved awareness of the disease and improved ability to self-monitor their symptoms. Moreover, we will compare the characteristics of the SSS-CN with another somatic symptom questionnaire, namely, the PHQ15.

The SSS-CN is designed as a ‘one-stop shop’ tool that combines somatic items with mental disorder items. This design is consistent with the suggestion in the DSM-5 that somatic symptoms are likely accompanied by depression and anxiety.1 Somatic and mental symptoms may interact, and mental symptoms may be triggered differently from conventional mental diseases among patients with SSD. Clinically, it is not easy to clearly separate the body from mental status, and the significance of each item is unknown. We caution that 50% of mental items may increase the incidence of SSD, and a subgroup score with only somatic symptom items is used for this appraisal.

In our study, there is no plan to supplement medication treatment of psychotherapy. This is because there are societal and cultural culture differences in response to psychotherapy between Asian and non-Asian patients. The Chinese World Mental Health Survey (2001–2002) conducted in Beijing and Shanghai found that only 3.4% of respondents with a psychiatric disorder sought professional help during the previous 12 months.19 Similarly, in a large epidemiological study conducted in four provinces of China (63 004 participants aged 18 years or older in 96 urban neighbourhoods and 267 rural villages), only 8% of individuals with mental disorders sought professional help within the general healthcare setting, and only 5% sought help from mental health professionals (mainly hospital-based psychiatrists).20 Second, Chinese and Asian Americans are likely to drop out and prematurely terminate psychotherapy services.8 Third, there is a shortage of psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses and counselling and clinical psychologists to provide psychotherapy.21 In particular, China had only 1.49 psychiatrists per 100 000 people while, on average, middle-income and high-income countries worldwide have 2.03 psychiatrists per 100 000. Finally, insurance currently pays for treatment with medication but typically does not support psychotherapy, community recovery services or preventive care.

The study has several strengths. First, we introduce a tool to facilitate daily clinical work. The tool provides clinicians with an easy-to-use questionnaire for screening suspected SSD patients and referring the patients to specific doctors. Second, our previous study showed the reliability and factorial validity of the SSS-CN by using an early version of it.16 The current study further modifies the SSS-CN based on the DSM-5 and, for the first time, evaluates its clinical utility. Third, patients will benefit from the SSS-CN in the form of improved awareness of the disease and improved ability to self-monitor their symptoms.

This trial has some limitations. First, SSD can be accompanied by diagnosed medical disorders. The current study, however, represents the efficacy of the SSS-CN only in patients without organic diseases. Therefore, further research on the application of SSS-CN in patients with both SSD and diagnosed medical disorders is required. Moreover, the epidemiology of primary healthcare facilities is different from the epidemiology of general hospitals; therefore, the diagnostic accuracy in a healthcare sample requires additional investigation. Second, the study was designed as a midterm investigation with four measurement time points; thus, missing data must be considered. Because only 16% of patients in the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders study were involved in the follow-up,22 we estimate that there will be a high rate of missing data in our study. Because of the difficulty with compliance, only a small fraction (approximately 16%) of patients in study would be involved in the follow-up, and the result of monitoring the treatment effect may be affected by loss to follow-up.

This study will help to clarify whether the SSS-CN is an effective tool for rapidly screening and assessing the severity of symptoms in patients with suspected SSD in a general hospital clinic and during follow-up. If the SSS-CN is found to be effective, it can be implemented as a first-line screening and follow-up option. Additionally, we expect that the SSS-CN could provide personalised information to consulting physicians in a timely manner. The study results will contribute to better outpatient care for patients with SSD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the patients who participated and advised us throughout the study design and implementation for their contributions.

Footnotes

MJ and WZ contributed equally.

Contributors: MJ: substantial contributions to the conception, design and interpretation of data, drafting and critical revisions for important intellectual content. WZ: analysis, statistics and interpretation of data and drafting the manuscript. XS: design and implementation of study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting the manuscript. CG: analysis, statistics and interpretation of data. BC and ZF: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting the manuscript. JM: substantial contributions to the conception, design and interpretation of data and critical revisions for important intellectual content. JP: substantial contributions to the conception and design and interpretation of data.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC1312800);National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (81625002); National Natural Science Foundation of China (81971570, 81470391 and 81470389); Shanghai ShenKang Hospital Development Center (16CR3020A and 16CR3034A); Shanghai Municipal Education Commission Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant Support (20172014 and 20152209); Shanghai Outstanding Academic Leaders Program (18XD1402400); Shanghai Sailing Program (17YF1410500); Shanghai Pudong Health Development Center (PW2018D-03); and Shanghai Jiao Tong University (YG2016QN78, YG2016MS45 and YG2015ZD04).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was provided by the Renji Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee, approval number 2015016.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Barsky AJ, Orav EJ, Bates DW. Somatization increases medical utilization and costs independent of psychiatric and medical comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:903–10. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.8.903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5. 5th edn Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barsky AJ. Assessing somatic symptoms in clinical practice. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:407–8. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liang D, Mays VM, Hwang W-C. Integrated mental health services in China: challenges and planning for the future. Health Policy Plan 2018;33:107–22. 10.1093/heapol/czx137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith GR. The course of somatization and its effects on utilization of health care resources. Psychosomatics 1994;35:263–7. 10.1016/S0033-3182(94)71774-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hahn SR, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, et al. The difficult patient: prevalence, psychopathology, and functional impairment. J Gen Intern Med 1996;11:1 10.1007/bf02603477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Axelsson E, Andersson E, Ljótsson B, et al. The health preoccupation diagnostic interview: inter-rater reliability of a structured interview for diagnostic assessment of DSM-5 somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Ther 2016;45:259–69. 10.1080/16506073.2016.1161663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leong FT, Lau AS. Barriers to providing effective mental health services to Asian Americans. Ment Health Serv Res 2001;3:201–14. 10.1023/A:1013177014788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gierk B, Kohlmann S, Kroenke K, et al. The somatic symptom scale-8 (SSS-8): a brief measure of somatic symptom burden. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:399–407. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gierk B, Kohlmann S, Toussaint A, et al. Assessing somatic symptom burden: a psychometric comparison of the patient health questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) and the somatic symptom scale-8 (SSS-8). J Psychosom Res 2015;78:352–5. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tu C-Y, Liao S-C, Liu C-Y, et al. Application of the Chinese version of the Whiteley Index-7 for detecting DSM-5 somatic symptom and related disorders. Psychosomatics 2016;57:283–91. 10.1016/j.psym.2015.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Toussaint A, Murray AM, Voigt K, et al. Development and validation of the somatic symptom Disorder-B criteria scale (SSD-12). Psychosom Med 2016;78:5–12. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Toussaint A, Löwe B, Brähler E, et al. The Somatic Symptom Disorder - B Criteria Scale (SSD-12): Factorial structure, validity and population-based norms. J Psychosom Res 2017;97:9–17. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Laferton JAC, Stenzel NM, Rief W, et al. Screening for DSM-5 somatic symptom disorder: diagnostic accuracy of self-report measures within a population sample. Psychosom Med 2017;79:974–81. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. European Medicines Agency, Pre-authorisation evaluation of medicines for human use . Guideline on clinical evaluation of diagnostic agents. Available: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003584.pdf

- 16. Qi Z, Jialiang M, Chunbo L, et al. Developing of somatic self-rating scale and its reliability and validity. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medicine and Brain Science 2010;19:847–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakas CT, Yiannoutsos CT. Ordered multiple-class ROC analysis with continuous measurements. Stat Med 2004;23:3437–49. 10.1002/sim.1917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988;44:837–45. 10.2307/2531595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shen Y-C, Zhang M-Y, Huang Y-Q, et al. Twelve-month prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in metropolitan China. Psychol Med 2006;36:257–67. 10.1017/S0033291705006367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Phillips MR, Zhang J, Shi Q, et al. Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001-05: an epidemiological survey. Lancet 2009;373:2041–53. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60660-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu C, Chen L, Xie B, et al. Number and characteristics of medical professionals working in Chinese mental health facilities. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry 2013;25:277–85. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2013.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. primary care evaluation of mental disorders. patient health questionnaire. JAMA 1999;282:1737–44. 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.