Abstract

Objective

The overall objective of this study was to examine the differences in ultrasound availability in primary care across Europe.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Primary care.

Participants

Primary care physicians (PCPs).

Primary and secondary outcomes measures

The primary aim was to describe the variation in in-house primary care ultrasonography availability across Europe using descriptive statistics. The secondary aim was to explore associations between in-house ultrasonography availability and the characteristics of PCPs and their clinics using a mixed-effects logistic regression model.

Results

We collected data from 20 European countries. A total of 2086 PCPs participated, varying from 59 to 446 PCPs per country. The median response rate per country was 24.8%. The median (minimum–maximum) percentage of PCPs across Europe with access to in-house abdominal ultrasonography was 15.3% (0.0%–98.1%) and 12.1% (0.0%–30.8%) had access to in-house pelvic ultrasonography with large variations between countries. We found associations between in-house abdominal ultrasonography availability and larger clinics (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.2 to 4.9) and clinics with medical doctors specialised in areas, which traditionally use ultrasonography (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.1 to 3.8). Corresponding associations were found between in-house pelvic ultrasonography availability and larger clinics (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.3 to 2.7) and clinics with medical doctors specialised in areas, which traditionally use ultrasonography (OR 3.0, 95% CI 1.8 to 5.1). Additionally, we found a negative association between urban clinics and in-house pelvic ultrasound availability (OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.9).

Conclusions

Across Europe, there is a large variation in PCPs’ access to in-house ultrasonography and organisational aspects of primary care seem to determine this variation. If evidence continues to support ultrasonography as a front-line point-of-care test, implementation strategies for increasing its availability in primary care are needed. Future research should focus on facilitators and barriers that may affect the implementation process.

Keywords: organisation of health services, primary care, diagnostic radiology, ultrasound

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Primary care physicians were recruited from 20 European countries.

A convenience sample chosen by national leads was used, which may not be representative of their nations as a whole.

This study examines secondary data; the survey questions were not specifically designed for this analysis.

Introduction

Traditionally, ultrasound examinations were performed primarily by trained radiologists using high-end devices. However, the development in technology has made ultrasound devices smaller, better and cheaper, and thereby more accessible to clinicians.1 2 Today, diagnostic ultrasonography is performed either by an imaging specialist for a full comprehensive description of organ anatomy and pathology, or as a bedside point-of-care test where the clinician uses it in relation to the physical examination to rule in or rule out specific conditions.1 3 Indeed, ultrasound examinations are increasingly used in both primary and secondary care to improve diagnosis and facilitate patient pathways.4–6

Whereas the use of ultrasonography in secondary care is well described,1 4 7 literature on its use in primary care is sparse.5 6 8 Studies have suggested that point-of-care ultrasonography performed by primary care physicians (PCPs) may lead to improved diagnostic accuracy.5 9 However, ultrasonography is an operator-dependent examination and sufficient training of PCPs performing ultrasonography is paramount, especially if the frequency of performed ultrasound examinations is low. Today, ultrasound examinations in primary care may be performed by both specialists10 and general practitioners (GPs),11 depending on how the healthcare systems across Europe are organised.12 13 GPs with access to diagnostic tests have been found to diagnose, treat and refer patients more appropriately.14 Hence, in-house availability of ultrasonography in primary care may improve patient care.

The availability and use of ultrasound examinations in primary care differs between countries: experts have previously estimated that the proportion of primary care users across Europe varies from less than 1% to 67%,15 and in-house availability of ultrasonography varies from 4% to 58% in the Nordic countries alone.16 We do not know what determines this variation or the extent to which PCP and clinic characteristics are associated with the likelihood of in-house availability of ultrasonography.

The aims of this study were to describe the variation in in-house primary care ultrasonography availability across Europe, and the association between this availability and the characteristics of PCPs and their clinics.

Materials and methods

Our study was a secondary analysis of data from the Örenäs survey.17 The Örenäs survey investigated the influence of health system factors on the way that European PCPs manage their patients. As well as collection of demographic data, there was collection of data on PCPs’ in-house access to diagnostic abdominal and pelvic ultrasonography. In the present study, this access is compared with the demographic data. A predefined protocol was developed prior to accessing the data (see online supplementary file 1).

bmjopen-2019-030958supp001.pdf (403.6KB, pdf)

The questionnaire was piloted twice by PCPs in 16 Örenäs Research Group centres. Translations of the questionnaire into local languages were made where these languages were not English. Translation was validated by back-translation to assess semantic and conceptual equivalence and is described elsewhere.18 The questionnaires were put online using SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey, California, USA).

Participants and recruitment

The study was conducted in 25 Örenäs Research Group centres in 20 countries across Europe. In some countries, more than one Örenäs Research Group was keen to collect data for this study. In those countries, each group recruited participants on a regional basis, so there was no risk of geographical overlap.

Subjects were eligible for the survey if they were GPs or had specialist training, but worked in the community and could be accessed directly by patients without referral.

Each Örenäs Research Group local lead emailed a survey invitation to the PCPs in their local health district, with the aim of recruiting at least 50 participants. The Örenäs Research Group local leads were asked to recruit a varied sample with regards to gender, years since graduation, site of practice (urban, rural, remote) and size of practice. Consent was implied by agreeing to take part in the survey.

Data collection

Access to ultrasonography

Participants were asked if abdominal or pelvic diagnostic ultrasonography was available to them in (1) their own practice, (2) at their request outside their practice, or (3) not directly available to them, or only available via a specialist. We divided this into Access to in-house abdominal ultrasonography (AbdUS) and No access to in-house AbdUS (including access at their request outside their practices, not directly available to them or only available via a specialist) and correspondingly: Access to in-house pelvic ultrasonography (PelUS) and No access to in-house PelUS. Hence, the variables In-house access to AbdUS and In-house access to PelUS included direct access to diagnostic ultrasonography in respondents’ own practices.

Countries included

The survey was circulated in 20 countries across Europe: Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, England, Finland, France, Germany (Essen and Munich), Greece, Israel, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Poland (Bydgoszcz and Białystok), Portugal, Romania, Scotland, Slovenia, Spain (Barcelona, Galicia and Mallorca), Sweden and Switzerland.

Characteristics of the PCPs

PCPs were characterised by Gender, male/female; Level of seniority, <10 years of experience as a medical doctor and ≥10 years (including 10–19, 20–29, 30–39, 40 years or over); and Specialty of the PCP, GP/not GP (including specialists in ear, nose and throat, internal/general medicine, obstetrics/gynaecology, oncology, orthopaedics, paediatrics, other).

Characteristics of the clinics

PCPs’ clinics were characterised by location (self-defined by participants): urban or non-urban (including rural, island, mixed), and clinic size (number of PCPs in the clinic: solo (1 PCP), small (2–5 PCPs), medium (6–9 PCPs) and large (10 or more PCPs)).

In the survey, participants were asked if they had colleagues qualified in different specialties (ear, nose and throat, internal/general medicine, obstetrics/gynaecology, oncology, orthopaedics, paediatrics or other). We assessed the proportion of PCPs with colleagues in their clinic who were qualified in a specialty in which ultrasonography is traditionally used (where clinical guidelines for use and educational programmes exist for the specialty). We estimated this as the Proportion of PCPs having specialist in internal medicine in their clinic and the Proportion of PCPs with an obstetrician/gynaecologist colleague in their own clinic. Finally, we noted any free-text comments that the PCPs had a Sonographer/radiologist colleague in the clinic, elaborated under the reply ‘other’. Free text comments were translated using Google Translate.

Ethics

Other countries’ study leads either achieved local ethical approval or gave statements that formal ethical approval was not needed in their jurisdictions (see online supplementary file 2).

bmjopen-2019-030958supp002.pdf (104.2KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in this study.

Statistics

We calculated the proportions of PCPs with in-house access to AbdUS or PelUS for each of the characteristics. A mixed-effects logistic regression model was used to test associations between access to in-house ultrasonography and the characteristics of the PCP and clinic. To avoid estimating a large number of parameters, the mixed-effects logistic regression model included fixed effects for all variables and random effects for variables dependent on country. This model allowed us to look across countries and captured the country effect without losing too many degrees of freedom. To identify variables dependent on country, we used multiple logistic regression including main effects and interactions with country between each of the other main-effects variables. Backwards model selection was used to eliminate insignificant terms from the model. Missing data were considered completely random and ignored in the analysis. The model was estimated in STATA V.15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). Statistical significance was defined as a p value ≤0.05.

Results

A total of 2086 PCPs participated, varying from 59 to 446 PCPs per country. The median response rate per country was 24.8% (range, 7.1%–65.6%). There was a large between-country variation in the variables: 61.7% (range, 17.2%–88.0%) were female and 38.3% (range, 12.0%–82.8%) male; 96.9% (range, 81.6%–100%) were specialised as GPs, and 16.0% (range, 1.6%–55.9%) had less than 10 years’ experience as a medical doctor. The clinics were mainly urban: 59.7% (range, 28.6%–93.1%); 13.8% (range, 0.0%–55.2%) were solo practices, 39.0% (range, 7.9%–67.9%) small, 20.9% (range, 3.2%–55.5%) medium and 26.2% (range, 0.0%–70.1%) large. Between-country variations are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Description of participating PCPs and their practices

| Country | n (%) |

PCP characteristics n (%) | Clinic characteristics n (%) | Access AbdUS | Access PelUS | ||||||||||

| Gender | Seniority | Specialisation | Location | Clinic size | |||||||||||

| Female | Male | <10 years | ≥10 years | GP | Not GP | Urban | Not urban | Solo | Small | Medium | Large | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Bulgaria | 59 (65.6) |

44 (77.2) |

13 (22.8) |

8 (13.8) |

50 (86.2) |

52 (96.3) |

2 (3.7) |

44 (75.9) |

14 (24.1) |

32 (55.2) |

17 (29.3) |

2 (3.5) |

7 (12.1) |

8 (13.6) |

2 (3.4) |

| Croatia | 67 (22.9) |

54 (81.8) |

12 (18.2) |

11 (16.9) |

54 (83.1) |

52 (96.3) |

2 (3.7) |

31 (46.3) |

36 (53.7) |

33 (49.3) |

21 (31.3) |

11 (16.4) |

2 (3.0) |

1 (1.5) |

1 (1.5) |

| Denmark | 107 (26.8) |

59 (57.8) |

43 (42.2) |

6 (5.9) |

96 (94.1) |

85 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

68 (66.7) |

34 (33.3) |

18 (17.6) |

62 (60.8) |

19 (18.6) |

3 (2.9) |

2 (1.9) |

4 (3.4) |

| England | 65 (21.7) |

46 (70.8) |

19 (29.2) |

12 (18.8) |

52 (81.3) |

65 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

28 (43.1) |

37 (56.9) |

0 (0.0) |

19 (29.2) |

35 (53.9) |

11 (16.9) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

| Finland | 65 (36.5) |

45 (69.2) |

20 (30.8) |

29 (44.6) |

36 (55.4) |

51 (98.1) |

1 (1.9) |

56 (86.2) |

9 (13.9) |

2 (3.2) |

5 (7.9) |

21 (33.3) |

35 (55.6) |

23 (35.38) |

20 (30.77) |

| France | 59 (10.7) |

32 (54.2) |

27 (45.8) |

33 (55.9) |

26 (44.1) |

59 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

54 (93.1) |

4 (6.9) |

6 (10.2) |

36 (61.0) |

8 (13.6) |

9 (15.3) |

9 (15.25) |

12 (20.34) |

| Germany | 103 (42.6) |

30 (29.1) |

73 (70.9) |

3 (2.9) |

99 (97.1) |

84 (81.6) |

19 (18.5) |

61 (59.2) |

42 (40.8) |

26 (25.2) |

74 (71.8) |

3 (2.9) |

0 (0.0) |

101 (98.06) |

4 (3.88) |

| Greece | 68 (21.4) |

34 (50.0) |

34 (50.0) |

0 (0.0) |

68 (100) |

67 (98.5) |

1 (1.5) |

20 (29.4) |

48 (706) |

24 (36.4) |

22 (33.3) |

7 (10.6) |

13 (19.7) |

11 (16.18) |

9 (13.24) |

| Israel | 75 (22.1) |

38 (50.7) |

37 (49.3) |

17 (23.0) |

57 (77.0) |

71 (97.3) |

2 (2.7) |

66 (88.0) |

9 (12.0) |

7 (9.3) |

43 (57.3) |

18 (24.0) |

7 (9.3) |

6 (8.0) |

9 (12.0) |

| Italy | 63 (31.5) |

20 (33.3) |

40 (66.7) |

4 (6.5) |

58 (93.5) |

36 (83.7) |

7 (16.3) |

31 (49.2) |

32 (50.8) |

22 (34.9) |

22 (34.9) |

10 (15.8) |

9 (14.3) |

12 (19.05) |

8 (12.7) |

| Netherlands | 113 (7.1) |

51 (46.4) |

59 (53.6) |

17 (15.3) |

94 (84.7) |

32 (91.4) |

3 (8.6) |

55 (49.1) |

57 (50.9) |

5 (4.5) |

76 (67.9) |

29 (25.9) |

2 (1.8) |

13 (11.5) |

10 (8.85) |

| Norway | 90 (18.0) |

40 (44.4) |

50 (55.6) |

20 (22.2) |

70 (77.8) |

73 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

50 (55.6) |

40 (44.4) |

3 (3.3) |

58 (64.4) |

26 (28.9) |

3 (3.3) |

12 (13.33) |

11 (12.22) |

| Poland | 152 (36.0) |

110 (73.3) |

40 (26.7) |

52 (34.4) |

99 (65.6) |

145 (96.0) |

6 (4.0) |

108 (71.1) |

44 (29.0) |

9 (5.9) |

84 (55.3) |

41 (27.0) |

18 (11.8) |

50 (32.89) |

27 (17.76) |

| Portugal | 65 (28.6) |

48 (73.9) |

17 (26.2) |

39 (60) |

26 (40) |

65 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

44 (67.7) |

21 (32.3) |

2 (3.1) |

14 (21.5) |

36 (55.4) |

13 (20.0) |

2 (3.08) |

2 (3.08) |

| Romania | 177 (–) |

154 (88.0) |

21 (12.0) |

8 (4.6) |

167 (95.4) |

174 (98.9) |

2 (1.1) |

108 (61.7) |

67 (38.3) |

64 (37.7) |

70 (41.2) |

14 (8.2) |

22 (12.9) |

56 (31.64) |

38 (21.47) |

| Scotland | 65 (18.6) |

31 (47.7) |

34 (52.3) |

5 (7.8) |

59 (92.2) |

63 (98.4) |

1 (1.6) |

21 (32.3) |

44 (67.7) |

0 (0.0) |

18 (27.7) |

18 (27.7) |

29 (44.6) |

10 (15.38) |

10 (15.38) |

| Slovenia | 104 (29.5) |

78 (75.7) |

25 (24.3) |

17 (16.4) |

87 (83.7) |

102 (99.0) |

1 (1.0) |

44 (42.3) |

60 (57.7) |

7 (6.7) |

34 (32.7) |

27 (26.0) |

36 (34.6) |

43 (41.35) |

31 (29.81) |

| Spain | 446 (–) |

312 (70.4) |

131 (29.6) |

29 (6.5) |

417 (93.5) |

438 (98.9) |

5 (1.1) |

302 (67.9) |

143 (32.1) |

5 (1.1) |

59 (13.3) |

69 (55.5) |

312 (70.1) |

133 (29.82) |

81 (18.16) |

| Sweden | 79 (19.8) |

37 (46.8) |

42 (53.2) |

20 (25.3) |

59 (74.7) |

66 (95.7) |

3 (4.4) |

29 (36.7) |

50 (63.3) |

0 (0.0) |

34 (43.6) |

35 (44.9) |

9 (11.5) |

3 (3.8) |

5 (6.33) |

| Switzerland | 64 (64.0) |

11 (17.2) |

53 (82.8) |

1 (1.6) |

63 (98.4) |

61 (95.3) |

3 (4.7) |

18 (28.6) |

45 (71.4) |

21 (33.3) |

38 (60.3) |

2 (3.2) |

2 (3.2) |

26 (40.63) |

7 (10.94) |

| Totals* | 2086 | 1274 | 790 | 331 | 1737 | 1841 | 58 | 1238 | 836 | 286 | 806 | 431 | 542 | 521 | 291 |

| Median percentages (IQR) | 56.0 (46.7– 73.5) |

44.0 (26.5– 53.3) |

15.9 (6.4– 23.6) |

84.2 (76.4– 93.7) |

98.2 (95.9– 99.3) |

1.8 (0.8– 4.1) |

57.4 (42.9– 68.7) |

42.6 (31.3– 57.1) |

8.0 (3.2– 33.7) |

38.0 (29.3– 60.4) |

25.0 (12.9– 30.0) |

12.5 (3.3– 19.8) |

15.3 (7.0– 32.0) |

12.1 (3.8– 17.9) |

|

*Absolute numbers given in each variable (n) do not add up to the total number of participants in each country (N) due to missing values.

AbdUS, abdominal ultrasonography; GP, general practitioner; N (%), number of participants in each county (response rate); n, absolute value in each variable; PCP, primary care physician; PelUS, pelvic ultrasonography.

Using multiple logistic regression, we identified interactions between country and variables describing the characteristics of the clinics (Location, Clinic size, In-house colleague qualified in a medical specialty which traditionally uses ultrasonography). There were no interactions between country and variables describing the characteristics of the PCP (Gender, Level of seniority, Specialty of the PCP). As a result, we applied a mixed-effects logistic regression model that included fixed effects for all variables and random effects for variables describing the characteristics of the clinics. Visual inspection of the country-specific random effects showed concordance between AbdUS and PelUS, indicating comparable parameter estimates and that the country effects were modelled appropriately. Hence, we applied the same model structure to both AbdUS and PelUS.

Twenty-one observations from nine different countries were excluded due to an unreported number of PCPs working in the clinic. We chose to consider these missing data random, as we believed that the likelihood of the PCP answering the question about the number of PCPs working in the clinic was independent from the PCP’s access to in-house AbdUS or PelUS.

Variation in access to in-house ultrasonography between countries and between regions within a country

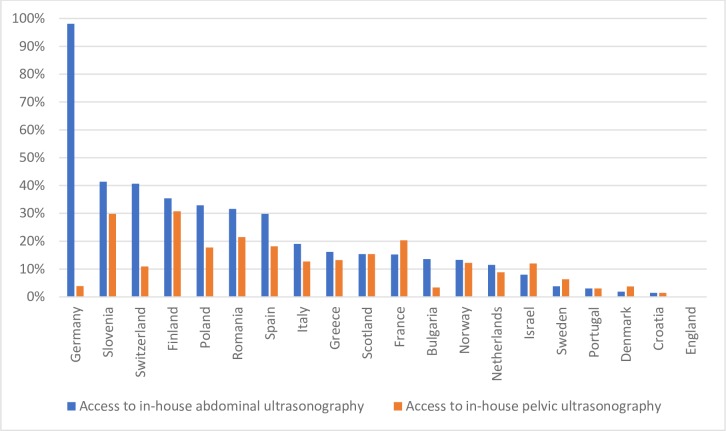

The median percentage of PCPs across Europe with access to in-house AbdUS was 15.3% (range, 0.0%–98.1%) and 12.1% (range, 0.0%–30.8%) had access to in-house PelUS. However, there was large variation between countries (table 1 and figure 1).

Figure 1.

Between-country differences in access to in-house diagnostic ultrasonography.

In-house access to AbdUS was very common in Germany (98.0%), followed by Slovenia (41.4%) and Switzerland (40.6%). In-house access to AbdUS was least available in England (0%), Croatia (1.5%) and Denmark (1.9%). Compared with AbdUS, in-house access to PelUS was less common, with the highest proportions found in Finland (30.8%), Slovenia (21.5%) and France (20.3%). In contrast, it was uncommon in England (0%), Croatia (1.5%) and Bulgaria (3.4%).

In addition, there were large differences in access to in-house AbdUS between the two Polish regions (Bialystok 17.9 and Bydgoszcz 57.9%) and the three Spanish regions (Mallorca 3.8%, Galicia 9.6% and Barcelona 43.7%), whereas there was little difference between the two German regions (Munich 96.3% and Essen 98.7%). There was also a large variation in the proportions of clinics with access to in-house PelUS in Germany (Essen 1.3% and Munich 11.1%), Poland (Bialystok 8.4% and Bydgoszcz 33.3%) and Spain (Galicia 4.8%, Mallorca 6.0% and Barcelona 25.8%).

PCP characteristics and in-house access to ultrasonography

We found no statistically significant associations between the PCP characteristics and in-house access to AbdUS or PelUS (table 2).

Table 2.

Associations between in-house access to ultrasonography and characteristics of PCPs and clinics

| AbdUS n (%) |

OR (95% CI)* |

P value† | PelUS n (%) |

OR (95% CI)* |

P value† | |

| Characteristics of the PCP | ||||||

| Male | 233 (29.5) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) | 0.101 | 116 (14.7) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 0.888 |

| Female | 285 (22.4) | – | – | 175 (13.7) | – | – |

| <10 years of experience | 65 (19.6) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 0.944 | 46 (13.9) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 0.798 |

| ≥10 years of experience | 453 (26.1) | – | – | 244 (14.1) | – | – |

| General practitioner | 468 (25.4) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.5) | 0.657 | 271 (14.7) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.4) | 0.304 |

| Not general practitioner | 53 (21.6) | – | – | 20 (8.2) | – | – |

| Characteristics of the clinic | ||||||

| Urban location | 350 (28.3) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.2) | 0.247 | 195 (15.8) | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.9) | 0.028 |

| Not urban location | 170 (20.3) | – | – | 96 (11.5) | – | – |

| Large practice | 212 (39.1) | 2.5 (1.2 to 4.9) | 0.008 | 144 (26.6) | 1.9 (1.3 to 2.7) | <0.001 |

| Medium practice | 78 (18.1) | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.5) | 0.765 | 57 (13.2) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.3) | 0.324 |

| Small practice | 182 (22.6) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.2) | 0.130 | 78 (9.7) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.9) | 0.011 |

| Solo practice | 47 (16.4) | – | – | 12 (4.2) | – | – |

| In-house colleague qualified in medical a specialty which traditionally uses ultrasonography†‡ | 90 (36.1) | 2.1 (1.1 to 3.8) | 0.016 | 99 (29.7) | 3.0 (1.8 to 5.1) | <0.001 |

n (%)=absolute number and percentage of dependent variable for each independent variable.

*ORs with 95% CI calculated using a mixed-effects logistic regression model including fixed effects for all variables and random-effects variables interacting with country.

†P values for adjusted OR

‡An in-house colleague who had specialised in internal medicine (for AbdUS) or gynaecology or obstetrics (for PelUS) was considered to have qualified in a medical specialty that traditionally uses ultrasonography.

AbdUS, access to in-house abdominal ultrasonography; PCP, primary care physician; PelUS, access to in-house pelvic ultrasonography.

Clinic characteristics and in-house access to ultrasonography

Larger practices were significantly associated with higher levels of both in-house access to AbdUS (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.2 to 4.9) and PelUS (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.3 to 2.7), while we found a negative association between a small practice size and PelUS (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.4 to 0.9) compared with solo practices. We also found a negative association between urban location and with higher levels of PelUS (OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.9). Having an in-house colleague specialised in a medical field which traditionally uses ultrasonography was found to be positively associated with having access to in-house AbdUS (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.1 to 3.8) and PelUS (OR 3.0, 95% CI 1.8 to 5.1); 36.1% of PCPs with in-house AbdUS had an internal medicine colleague in their clinics, and 29.7% of PCPs having in-house access to PelUS had a specialist in obstetrics/gynaecology in their clinics. Nine PCPs (Croatia, 1; Finland, 1; Greece, 2; Romania, 1; Scotland, 1; Slovenia, 3) stated that they had a radiologist or a sonographer in their practices.

Discussion

Principal findings

We found large variations across Europe in primary care access to in-house ultrasonography. The majority of PCPs do not have diagnostic ultrasonography available in their own clinics. We found some associations between characteristics of the clinic and the likelihood of having in-house ultrasonography, including a significant association between increased likelihood and clinics with more than 10 PCPs, and with clinics with colleagues specialised in internal medicine or gynaecology/obstetrics. We also found an association between increased likelihood of having in-house access to PelUS and non-urban clinics. Solo clinics were more likely to have in-house PelUS than other small clinics.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the large number of participating countries, with a response rate higher than previous studies.19 20 Moreover, the survey recruitment strategy was not biased by access to in-house ultrasonography since the overall aim of the survey was to explore PCPs’ decision-making with regard to referring patients who may have cancer for further investigation.

However, selection bias may have been introduced by both the recruitment methods and the survey distribution, and the participants may not be representative of the whole population of PCPs in each country. In most of the countries involved, the survey was only circulated in one specific region, and in those countries where regional data was available, we found inter-regional variation in ultrasonography access. This means that regional differences may have influenced our results.

Using secondary data may introduce information bias. In our study, we explored whether having access to in-house ultrasonography was associated with having a colleague specialised in a medical field that traditionally uses ultrasonography. We did not explore whether this colleague was actually performing ultrasound examinations in respondents’ clinics. Furthermore, a statement that the respondent had a sonographer or radiologist colleague in the clinic depended on the participant’s free-text answers, and the frequency of this may therefore be underestimated.

We collected data on the GPs (gender, level of seniority and specialty) and the clinics (location and size); other background characteristics may influence the PCP’s access to ultrasonography. Thus, residual confounding may exist.

This study used an exploratory approach for the secondary outcomes and the statistical model included all possible associations between the measured variables. However, the nature of our sample may have caused limitations as some associations may have been missed due to lack of power, and some variables may have been eliminated during the fitting of the model due to lack of power. However, the aim of this study was a preliminary assessment and more research is needed to determine the importance of different factors in relation to in-house ultrasonography access.

Comparison with existing literature

In a survey from 2016,15 ultrasound experts estimated the proportion of GPs using ultrasonography to vary from less than 1% in Austria, Catalonia, Denmark and Sweden to 45% in Germany. Our study confirmed significant variation, although our proportions were higher (figure 1). This may be caused by selection bias or by the difference between estimations by experts and measured proportions. Furthermore, the previous study estimated PCPs’ use of ultrasonography, while our study measured PCPs’ actual access to in-house ultrasonography. Access to ultrasonography in the Scandinavian countries was explored using QUALICOPC data from 2012.16 This found higher levels of access than our study (Denmark 11.3%, Finland 57.7%, Norway 16.7%, Sweden 4.1%). This may be because the QUALICOPC study asked about access to any type of ultrasound, not specifically diagnostic abdominal or pelvic ultrasonography; hence, therapeutic ultrasound used for musculoskeletal conditions and A-mode ultrasound may have been included in those data.

European between-country variations have also been described for other diagnostic tests in primary care13; thus, variations in access to in-house ultrasound may be caused by national differences in the organisation of primary care. For example, the high proportion in Finland may be explained by larger healthcare centres with more advanced equipment,16 whereas in Germany PCPs are taught how to use ultrasonography for abdominal examinations.21 Whether the gate-keeper function that PCPs have in some countries,12 the specialty training system for PCPs, the PCP’s ultrasound training or the waiting time to see a specialist is important is unclear since we did not collect data on these issues.

Financial aspects may also be important. In countries where PCPs are largely self-employed,22 they need to pay for ultrasound equipment themselves. In addition, ultrasonography is a time-consuming examination, and differences in remuneration for performing ultrasonography may be of particular importance.12 15 23 Workload for the PCP may also be an important factor since research has shown considerable variation in the number of consultations per day23 and the consultation length.24

Distance from the secondary care provider has previously been found to be of importance for in-house PelUS,25–27 and our study also found an association between in-house PelUS availability and non-urban practices. Associations between technology and larger clinics have previously been described.23 However, the association between larger clinics and access to ultrasonography may also be explained by the multidisciplinary nature of some larger clinics. Some countries, for example, Finland, Spain, Sweden and England, have multidisciplinary teams working in primary care, while others, for example, Switzerland, Romania, Norway, Germany, Denmark and Bulgaria, tend to have less staff.28 29 In our study, we found an association between in-house ultrasonography availability and having a colleague in the clinic who was qualified in a medical specialty which traditionally uses ultrasonography. However, we do not know if these colleagues were performing ultrasonography examinations, and most PCPs did not have such colleagues. As AbdUS and PelUS can be performed by PCPs with different educational backgrounds and correspondingly different levels of ultrasound training, quality assurance of ultrasound examinations performed in primary care is important.

Implications

Several factors may influence the availability of ultrasonography in primary care across Europe, including who performs the examinations and the organisation of healthcare systems. This study may generate hypotheses for future studies that further explore national factors. As ultrasonography is disseminating into primary care, knowledge about the influence that these factors have are important to guide the implementation process and to secure appropriate use of the technology.

Conclusions

PCPs’ access to in-house ultrasonography in primary care across Europe varied from 0% to 98% for AbdUS, and 0% to 31% for PelUS. While in-house ultrasonography might be an important tool to ensure faster and more correct diagnosis in primary care, in every country except Germany it was available to less than half of our PCP respondents. As evidence continues to support point-of-care ultrasonography as a front-line test, implementation strategies for the increased availability of the technology in primary care are needed. Several factors might influence PCPs’ access to in-house diagnostic ultrasonography, and future research should focus on exploring these factors further.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Associate Professor, PhD Torben Tvedebrink for statistical assistance, the Örenäs Research Group collaborators who collected the survey data and all the PCPs who completed the survey.

Footnotes

Contributors: CAA, MH, BST, PV and MBBJ all participated in designing the study. CAA performed the analysis and wrote the first draft of the article in collaboration with MH and MBBJ. All authors participated in the review process and made significant contributions to the final version of the article. The following Örenäs Research Group members participated in designing and/or piloting the study, and are non-author collaborators: Isabelle Aubin-Auger, Université Paris Diderot, France; Joseph Azuri, Tel Aviv University, Israel; Matte Brekke, University of Oslo, Norway; Krzysztof Buczkowski, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Poland; Nicola Buono, National Society of Medical Education in General Practice (SNaMID), Italy; Emiliana Costiug, Iuliu Hatieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Romania; Geert-Jan Dinant, Maastricht University, Netherlands; Magdalena Esteva, Majorca Primary Health Care Department, Palma Mallorca, Spain; Gergana Foreva, Medical Center BROD, Bulgaria; Svjetlana Gašparović Babić, The Teaching Institute of Public Health of Primorsko-goranska County, Croatia; Robert Hoffman, Tel Aviv University, Israel; Eva Jakob, Centro de Saúde Sarria, Spain; Tuomas Koskela, University of Tampere, Finland; Mercè Marzo-Castillejo, Institut Català de la Salut, Barcelona, Spain; Peter Murchie, University of Aberdeen, Scotland; Ana Luísa Neves, Imperial College, UK and University of Porto, Portugal; Davorina Petek and Marija Petek Ster, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia; Jolanta Sawicka-Powierza, Medical University of Bialystok, Poland; Antonius Schneider, Technische Universität München, Germany; Emmanouil Smyrnakis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece; Sven Streit, University of Bern, Switzerland; Hans Thulesius, Lund University, Sweden; Birgitta Weltermann, University of Bonn, Germany.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the original study was given by the University of Bath Research Ethics Approval Committee for Health (approval date: 24 Nov 2014; REACH reference no. EP 14/15 66).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Moore CL, Copel JA. Point-of-care ultrasonography. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2011;364:749–57. 10.1056/NEJMra0909487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Szwamel K, Polański P, Kurpas D. Experiences of family physicians after a CME ultrasound course. Fmpcr 2017;1:62–9. 10.5114/fmpcr.2017.66666 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Diprose W, Verster F, Schauer C. Re-examining physical findings with point-of-care ultrasound: a narrative review. N Z Med J 2017;130:46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dietrich CF, Goudie A, Chiorean L, et al. Point of care ultrasound: a WFUMB position paper. Ultrasound Med Biol 2017;43:49–58. 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Steinmetz P, Oleskevich S. The benefits of doing ultrasound exams in your office. J Fam Pract 2016;65:517–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Genc A, Ryk M, Suwała M, et al. Ultrasound imaging in the general practitioner’s office—a literature review. J Ultrason 2016;16:78–86. 10.15557/JoU.2016.0008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laursen CB, Sloth E, Lassen AT, et al. Point-of-care ultrasonography in patients admitted with respiratory symptoms: a single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:638–46. 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70135-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reports from the Spanish Agency for Health Technology Assessment (AETS). Ultrasonography in primary health care. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1999;15:773–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Andersen CA, Holden S, Vela J, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound in general practice: a systematic review. Ann Fam Med 2019;17:61–9. 10.1370/afm.2330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Filipas D, Spix C, Schulz-Lampel D, et al. Screening for renal cell carcinoma using ultrasonography: a feasibility study. BJU Int 2003;91:595–9. 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2003.04175.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Glasø M, Mediås IB, Straand J. [Diagnostic ultrasound in general practice]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2007;127:1924–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. OECD/EU Health at a glance: Europe 2016: state of health in the EU cycle. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schäfer WLA, Boerma WGW, Spreeuwenberg P, et al. Two decades of change in European general practice service profiles: conditions associated with the developments in 28 countries between 1993 and 2012. Scand J Prim Health Care 2016;34:97–110. 10.3109/02813432.2015.1132887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wenghofer E, Williams A, Klass D. Factors affecting physician performance: implications for performance improvement and governance. Hcpol 2009;5:e141–60. 10.12927/hcpol.2013.21178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mengel-Jørgensen T, Jensen MB. Variation in the use of point-of-care ultrasound in general practice in various European countries. Results of a survey among experts. Eur J Gen Pract 2016;22:274–7. 10.1080/13814788.2016.1211105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eide TB, Straand J, Björkelund C, et al. Differences in medical services in Nordic general practice: a comparative survey from the QUALICOPC study. Scand J Prim Health Care 2017;35:153–61. 10.1080/02813432.2017.1333323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harris M, Taylor G. How health system factors affect primary care practitioners’ decisions to refer patients for further investigation: protocol for a pan-European ecological study. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18 10.1186/s12913-018-3170-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harris M, Vedsted P, Esteva M, et al. Identifying important health system factors that influence primary care practitioners’ referrals for cancer suspicion: a European cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022904 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pit SW, Vo T, Pyakurel S. The effectiveness of recruitment strategies on general practitioner’s survey response rates—a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:76 10.1186/1471-2288-14-76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rose PW, Rubin G, Perera-Salazar R, et al. Explaining variation in cancer survival between 11 jurisdictions in the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership: a primary care vignette survey. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007212 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heidemann F, Meier U, Kölbel T, et al. How can an AAA screening program be implemented in Germany? Gefässchirurgie 2015;20:28–31. 10.1007/s00772-014-1392-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boerma WG, van der Zee J, Fleming DM. Service profiles of general practitioners in Europe. European GP task profile study. Br J Gen Pract 1997;47:481–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. De Rosis S, Seghieri C. Basic ICT adoption and use by general practitioners: an analysis of primary care systems in 31 European countries. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2015;15:70 70-015-0185-z. 10.1186/s12911-015-0185-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Irving G, Neves AL, Dambha-Miller H, et al. International variations in primary care physician consultation time: a systematic review of 67 countries. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017902-2017-017902 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eggebø TM, Dalaker K. [Ultrasonic diagnosis of pregnant women performed in general practice]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 1989;109:2979–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johansen I, Grimsmo A, Nakling J. [Ultrasonography in primary health care—experiences within obstetrics 1983–99]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2002;122:1995–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wordsworth S, Scott A. Ultrasound scanning by general practitioners: is it worthwhile? J Public Health 2002;24:88–94. 10.1093/pubmed/24.2.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schäfer WLA. Primary care in 34 countries: perspectives of general practitioners and their patients [dissertation]. Utrecht University Repository, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Groenewegen P, Heinemann S, Greß S, et al. Primary care practice composition in 34 countries. Health Policy 2015;119:1576–83. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030958supp001.pdf (403.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030958supp002.pdf (104.2KB, pdf)