Abstract

Objectives

Systematically review the qualitative literature on living with knee osteoarthritis from patient and carer perspectives.

Design

Systematic review of qualitative studies. Five electronic databases (CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, SPORTDiscus) were searched from inception until October 2018. Data were synthesised using thematic and content analysis.

Participants

Studies exploring the experiences of people living with knee osteoarthritis, and their carers were included. Studies exploring experiences of patients having participated in specific interventions, including surgery, or their attitudes about the decision to proceed to knee replacement were excluded.

Results

Twenty-six articles reporting data from 21 studies about the patient (n=665) and carer (n=28) experience of living with knee osteoarthritis were included. Seven themes emerged: (i) Perceived causes of knee osteoarthritis are multifactorial and lead to structural damage to the knee and deterioration over time (n=13 studies), (ii) Pain and how to manage it predominates the lived experience (n=19 studies), (iii) Knee osteoarthritis impacts activity and participation (n=16 studies), (iv) Knee osteoarthritis has a social impact (n=10 studies), (v) Knee osteoarthritis has an emotional impact (n=13 studies), (vi) Interactions with health professionals can be positive or negative (n=11 studies), (vii) Knee osteoarthritis leads to life adjustments (n=14 studies). A single study reporting the perspectives of carers reported similar themes. Psychosocial impact of knee osteoarthritis emerged as a key factor in the lived experience of people with knee osteoarthritis.

Conclusions

This review highlights the value of considering patient attitudes and experiences including psychosocial factors when planning and implementing management options for people with knee osteoarthritis.

Trial registration number

CRD42018108962

Keywords: lived experience, qualitative, systematic review, osteoarthritis, knee

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The systematic review was reported consistent with the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research and registered prospectively with PROSPERO.

A comprehensive search strategy of qualitative studies about patient and carer perceptions about their lived experience with knee osteoarthritis was conducted.

Comprehensive data synthesis was applied using thematic and content analysis leading to results that went beyond the summary of the selected studies.

The findings of this review are limited to the experience of living with knee osteoarthritis, and not the experience of receiving specific interventions, including surgery.

Exclusion of non-English language articles limits the generalisability as other cultures with other languages might have different perceptions of knee osteoarthritis.

Introduction

The experience of living with chronic pain associated with knee osteoarthritis is multidimensional comprising biological dimensions such as subchondral bone pathology and inflammation,1 and psychological and social dimensions such as pain catastrophising, depression, avoidance of activities and social support.2–4 The current management of knee osteoarthritis is focussed on pain management to address biological dimensions (joint pathology), through joint-specific exercises, pharmacology and in advanced stages, joint replacement surgery.5 6 However, levels of pain and disability reported by people with osteoarthritis are poorly correlated with radiographic severity of joint pathology, suggesting other factors apart from biological dimensions can affect the experience of living with knee osteoarthritis.7 Further, knee replacement surgery to address joint pathology, does not always have a successful outcome. Only about 40% of patients report being pain-free 2 years after surgery,8 and about 20% were not satisfied with surgical outcome 1 year after surgery.9

The role of psychological and social dimensions in the management of knee osteoarthritis has received relatively little attention in comparison with management of joint pathology.2 In other chronic musculoskeletal conditions, the role of psychological and social dimensions has been studied extensively.10 For example, in chronic low back pain, psychological and social factors have been shown to play a role in the persistence of pain, and interventions designed to target these factors can improve pain, disability and quality of life in this population.11 12 Targeting the psychological and social dimensions of knee osteoarthritis in addition to the biological dimensions, consistent with a biopsychosocial approach, may optimise outcomes. There is preliminary evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 randomised controlled trials showing psychological interventions, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, are associated with short-term reductions in pain for people with knee osteoarthritis.13 Further, there is preliminary evidence from a randomised controlled trial that combining physiotherapist-delivered pain coping skills training with exercise therapy, can lead to greater improvements in function compared with either treatment alone.14 In order to design targeted interventions consistent with a biopsychosocial approach, we must first understand the psychological and social dimensions of knee osteoarthritis from the perspectives of people living with the condition.

Qualitative research provides insight into the lived experience of health and how individuals’ make sense of their health symptoms. Rather than relying on the a priori assumptions of researchers or clinicians, qualitative research prioritises the voice of the ‘expert’ participant, thus shedding light on aspects of the lived experience that cannot be reached by quantitative approaches.15 Two recent systematic reviews have synthesised qualitative research related to knee pain, including people living with osteoarthritis.16 17 Wride17 explored the feelings and experiences of people living with knee pain from nine studies, three of which included people with non-osteoarthritic related knee pain. This review found many people with knee pain struggle to adapt to normal living, and that their negative experiences were exacerbated by a lack of knowledge and available information to help them plan for the future. In another review, Smith et al 16 explored the perceptions of people diagnosed with hip and/or knee osteoarthritis from 32 studies (18 of which sampled people with knee osteoarthritis only) to determine their attitudes and perceptions towards living with their musculoskeletal condition. Participants in these studies reported a number of factors that contributed to their negative attitude and perception about their hip and/or knee osteoarthritis, such as their understanding of the pathology of osteoarthritis, the activity limitations they experienced and their perceptions of other people’s beliefs towards their condition.

The two previous systematic reviews synthesising qualitative data have limitations as they did not consider the experience of knee osteoarthritis separately to the experience of non-osteoarthritic related conditions (eg, Wride17), and to the experience of hip osteoarthritis (eg, Smith et al 16). Empirical evidence suggests hip and knee osteoarthritis are distinct conditions that impact people in different ways.18 In addition, neither review16 17 looked at the perspectives of carers. Those in the immediate social environment may exert an influence on how an individual copes with their condition. In the case of knee osteoarthritis, family members and significant others often adopt the role of carer. By investigating the perceptions and experiences of both patients and carers, health professionals can gain a greater understanding of how living with knee osteoarthritis effects their lives, which may lead to improved management of people with knee osteoarthritis.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to systematically review the qualitative literature on the experience of living with knee osteoarthritis from the perspectives of patients and carers.

Methods and analysis

Design

A systematic review of qualitative studies was conducted. The review was reported consistent with the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research.19

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the development of the research question, outcome measures or research design.

Search strategy

Five electronic databases (CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, SPORTDiscus) were searched from inception until October 2018. The search strategy comprised two key concepts: knee osteoarthritis and qualitative research. For each concept, key words and Medical Subject Headings terms were combined using the ‘OR’ operator and the results were combined using the ‘AND’ operator (Appendix). The search results were downloaded into bibliographic software (Endnote V.18). Two reviewers independently reviewed the titles and abstracts according to the selection criteria (table 1). If eligibility was uncertain based on title and abstract, the full-text of the study was obtained. Reference lists of included articles were manually searched for additional relevant articles, and citation tracking of included articles was completed using Google Scholar.

Table 1.

Selection criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

| Design and report |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions |

|

|

Eligibility criteria

Studies reporting the experiences of people living with knee osteoarthritis, and their carers were included. Studies that explored experiences of participation in specific interventions for knee osteoarthritis, including perioperative management and attitudes about the decision to proceed to total knee replacement were excluded as the focus of the review was on the lived experience of knee osteoarthritis, and not about the response to treatment from receiving a specific intervention (table 1). Since the aim of our review was to explore the experience of living with knee osteoarthritis, with a focus on the psychological and social dimensions, it was decided not to include studies that explored perceptions about biological interventions including surgery.

Methodological quality of the included studies

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist was used to assess methodological quality of the included studies.20 The CASP checklist includes 10 questions in three sections about the validity of the results (questions 1 to 6), ethical considerations, trustworthiness and clarity of results (questions 7 to 9) and the value of the results (question 10). Two reviewers (JW, SB) independently answered each question as ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘can’t tell’, by reading the decision rules and instructions on how to interpret checklist criteria. Discrepancies between reviewers were discussed with a third reviewer (NT) until consensus was reached with the overall judgement scored as yes or no. The CASP checklist has been used in other qualitative systematic reviews in musculoskeletal research.21 22

Data collection process

Data were extracted from each study on participant age, sex, disease severity and body mass index, where available. Data were also extracted on the study design including sample size, data collection method (eg, interview or focus group) and qualitative framework informing the analysis. From the results section of each included paper, we extracted the main themes and subthemes as outlined below.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using a three-stage approach adapted from Sandelowski and Barroso.23 In stage one, the results sections of each paper including direct quotations were read and re-read so the authors familiarised themselves with the content, prior to extracting main themes and subthemes. Themes and subthemes were then extracted and assigned descriptive codes using an inductive process. In stage two, the identified codes were then reviewed and codes were grouped together according to their topical similarity. In stage three, these groupings of codes were subsequently organised into themes and subthemes in a process of thematic analysis. To help understand the relative importance of the emergent themes and subthemes relative to each other, and consistent with content analysis methods, the number of studies that identified each theme was counted. The process of data extraction, initial coding, grouping of codes and identification of emergent themes and subthemes was completed by one researcher (NS). The data analysis process was subsequently checked independently by two other researchers (JW, NT) before the final themes and subthemes were confirmed by the research team.

Results

Study selection

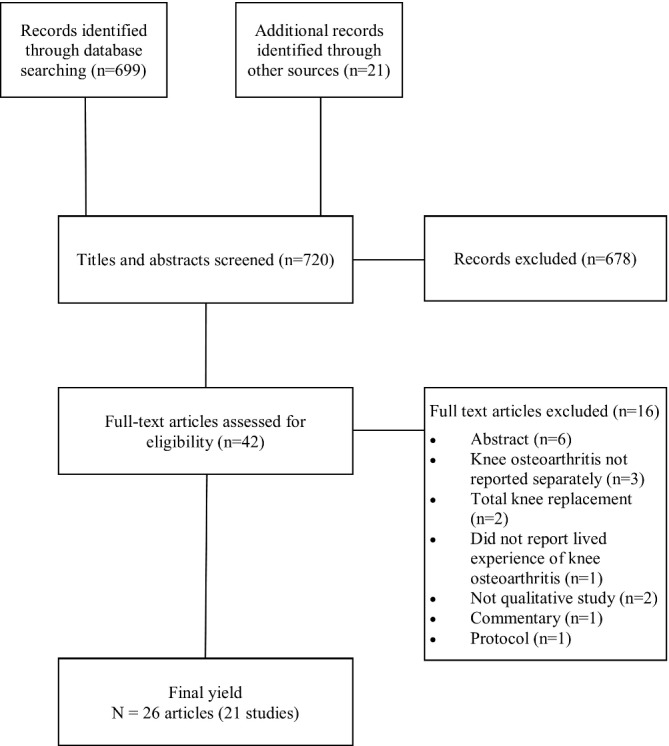

The search strategy yielded 720 articles. After screening the titles and abstracts of these articles, 42 underwent full text review. Sixteen articles were excluded after full text review resulting in a final library of 26 articles (figure 1). The most common reasons for exclusion were that articles were abstracts, and the results of knee osteoarthritis were not reported separately from osteoarthritis at other joints. The 26 included articles reported data from 21 studies (table 2) on the experience of living with knee osteoarthritis from the perspectives of people themselves (n=20) or their carers (n=1).

Figure 1.

Yield of studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies of experiences of living with knee osteoarthritis

| Study | Country | Population | Demographics (N, age, sex, BMI) |

Method: framework/analysis | Sampling | Data collection | Research questions |

| Alami et al 44 | France | Knee osteoarthritis | n=81 71% women, |

Descriptive -Inductive |

Purposive | Individual interviews -semi-structured |

Explore views of patients about management of knee osteoarthritis |

| Ahmad et al 26 | Malaysia | Knee osteoarthritis | n=12 Mean age 67 years 67% women |

Thematic analysis | Purposive | Individual interviews -in-depth |

Explore perspectives of patients with knee OA mainly about pain experiences, its impact, effects of physiotherapy and their personal expectation |

| Al-Taiar et al 38 | Kuwait | Severe knee osteoarthritis -Kuwaiti women waitlisted for total knee replacement |

n=39 Mean age 62 years 100% women |

Thematic analysis | Convenience | Focus groups | Explore the pain experience and mobility limitation as well as the patient’ s decision-making process to undertake total knee replacement among women with knee pain in the waiting list for surgery |

| Carmona-Terés et al 31 | Spain | Knee osteoarthritis -symptomatic |

n=10 Mean age 70 years, 70% women |

Content thematic analysis based on Lazarus stress model categories | Theoretical | Individual interviews -semi-structured |

Understand experiences, perceptions, cognitive evaluation, values, emotions, beliefs and coping strategies of people with knee osteoarthritis |

| Chan and Chan27 | Hong Kong | Knee osteoarthritis -mild to very severe |

n=20 Mean age 57 years, 65% women |

Grounded theory | Convenience | Individual interviews -semi-structured |

Evaluate influence of different pain patterns on quality of life Investigate coping strategies |

| Clarke et al

62

Pouli et al 32 |

UK | Knee osteoarthritis -symptomatic |

n=24 Mean age 62 years, 71% women |

Descriptive thematic analysis | Purposive | Individual interviews -semi-structured |

Explore participant’s experience of living with knee osteoarthritis and their beliefs about knee osteoarthritis and its treatment |

| Darlow et al 28 | NZ | Knee osteoarthritis | n=13 Age range 50–84 54% women |

Interpretative description | Purposive | Individual interviews -semi-structured |

Explore the beliefs of people with knee osteoarthritis about the disease, how these beliefs had formed and what impact these beliefs had on activity participation, health behaviour and self-management |

| Figaro et al 43 | USA | Knee osteoarthritis -not actively seeking total knee replacement |

n=94 Mean age 71 years 84% women |

Content analysis Constant comparative methods |

Purposive Network, convenience and snowball sampling to extend the sample |

Structured field interviews | Explore older urban Blacks with knee osteoarthritis to determine their preferences and expectations of total knee replacement |

| Hall et al 29 | Canada | Unilateral knee osteoarthritis -scheduled for total knee replacement |

n=15 Mean age 67 years 40% women |

Grounded theory | Purposive | Individual interviews -semi-structured |

Explore views of total knee replacement and the role of physiotherapy |

| Hendry et al 33 | UK | Knee osteoarthritis -mild-to-severe symptoms |

n=22 Age range 52–86 years 73% women |

Conceptual Framework | Convenience | Individual interviews Focus Groups (n=6) |

Explore the views of primary care patients with knee osteoarthritis towards exercise, and explore factors that determine acceptability and motivation to exercise, and barriers that limit its use |

| Hsu et al 42 | Taiwan | Family carers of people with knee osteoarthritis | n=28 Mean age 48 years, 46% women |

Descriptive content analysis | Convenience | Individual interviews -semi-structured |

Explore primary caregivers’ perceptions of their older relatives’ knee osteoarthritis pain and management |

| Keysor et al 41 | USA | Knee osteoarthritis -presence of functional limitations |

n=4 Age range 25–43 years, 75% women |

Van Kaam method of phenomenological data analysis | Purposive | Individual interviews -semi structured (each participant interviewed twice) |

Understand the experience of living with osteoarthritis as young and middle-aged adults |

| Kao and Tsai37 46 | Taiwan | Knee osteoarthritis -symptomatic |

n=17 Mean age 50 years, 82% women |

Constant comparison | Purposive | Individual interviews -semi structured |

Understand the living and illness experiences of middle-aged adults with early knee osteoarthritis |

| MacKay et al 35 63 64 | Canada | Knee osteoarthritis -moderately symptomatic |

n=51 Median age 49 years, 61% women |

Constructivist grounded Theory/ constant comparative method |

Purposive | Focus groups Individual interviews -semi-structured |

Explore the meaning and perceived consequences of knee symptoms |

| Maly and Krupa45 | Canada | Knee osteoarthritis | n=3 Age range 62–87 years, 67% women |

Descriptive phenomenology | Convenience | Individual interviews -semi structured |

Understand the experience of living with knee osteoarthritis in older adults |

| Man et al 39 | USA | Knee osteoarthritis -waitlisted for total knee replacement |

n=8 Age range 46–80 years 50% women |

Thematic analysis | Purposive | Individual interviews -semi-structured |

Explore the meaning and importance of occupational changes experienced by individuals during the pre- total knee replacement period |

| Morden et al, 34

Ong et al 65 |

UK | Knee osteoarthritis -moderate to severe |

n=22 Age range 50–75+yrs, 59% women |

Constant comparison | Purposive | Individual interviews -in-depth Diaries |

Explore the meaning and enactment of self-management in everyday life |

| Nyvang et al 40 | Sweden | Knee osteoarthritis -scheduled for total knee replacement |

n=12 Mean age 66 years 58% women |

Thematic analysis | Purposive | Individual interviews -semi-structured |

Explore patients’ experiences of living with knee osteoarthritis when scheduled for total knee replacement and further their expectations for future life after surgery. |

| Tallon et al 25 | UK | Knee osteoarthritis -mild to moderate |

n=7 | Content analysis | Convenience | Focus group | Explore perception of treatment preferences |

| Victor et al 24 | UK | Knee osteoarthritis | n=170 Mean age 63 years, 73% women |

Content analysis | Convenience | Individual interviews Group discussion Diaries |

Explore meaning of osteoarthritis for those receiving health promotion |

| Xie et al 36 | Singapore | Knee osteoarthritis -symptomatic |

n=41 Mean age 64 years, 66% women |

Grounded theory/ content analysis |

Purposive | Focus groups | Determine health-related quality of life domains affected by knee osteoarthritis. and identify ethnic variations in the importance of these domains |

BMI, body mass index; OA, osteoarthritis; Yrs, Years.

Methodological quality of included studies

All studies had a clear rationale for using qualitative methods, used appropriate qualitative designs and included explicit statements of findings that were considered high value. Two studies did not report approval from an ethics committee24 25 and four studies reported insufficient details about data analysis reducing the trustworthiness of the results.24–27 Only 2 of the 21 studies adequately reported the relationship between the researcher and the participant.28 29 A pre-existing relationship between the participant and researcher increases the risk of social desirability,30 whereby there is the tendency of the participants to answer questions in a manner that will be viewed favourably by the researchers (table 3).

Table 3.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme assessment

| Study name | 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 6. Has the relationship between researcher and participant been adequately considered? | 7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 9. Is there a clear statement of findings? | 10. How valuable is the research? |

| Alami et al 44 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Ahmad et al 26 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Al-Taiar et al 38 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Carmona-Terés et a31 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Chan and Chan27 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Clarke et al

62

Pouli et al 32 |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Darlow et al 28 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Figaro et al 43 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hall et al 29 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hendry et al 33 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hsu et al 42 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Kao et al 37 46 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Keysor et al 41 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Mackay et al 35 63 64 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Maly and Krupa45 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Man et al 39 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Morden et al, 34

Ong et al 65 |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Nyvang et al 40 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Tallon et al 25 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y |

| Victor et al 24 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y |

| Xie et al 36 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

N, No; Y, Yes.

Study participant characteristics

The 21 studies included 665 people with knee osteoarthritis (71% women; mean age 65 years, age range 25 to 87) and 28 carers of people with knee osteoarthritis (46% women; mean age 48 years) (table 2). The studies were conducted in Asia (n=6), North America (n=6), Europe (n=8) and New Zealand (n=1) and 15 of the 21 studies were published since 2011. Participants’ comorbidities as described in six studies included diabetes, depression/anxiety, polyarthritis, hypertension, heart disease, haemophilia, silicosis, vascular problems, cancer, gout, osteoarthritis in other joints and multiple knee surgeries. Participants in nine studies self-assessed their pain severity at the time of their participation as mild-to-severe,25 27 31–37 and participants in four studies had severe osteoarthritis and were awaiting total knee replacement.29 38–40 Thirteen studies provided details on participant employment status; the majority of participants were retired or not working, except for three studies28 35 41 in which the majority of participants were employed at the time of the study.

Major themes reported by included studies

Seven major themes emerged from the data: (i) The perceived causes of knee osteoarthritis are multifactorial and lead to structural damage to the knee and deterioration over time, (ii) Pain and how to manage it predominates the lived experience, (iii) Knee osteoarthritis impacts activity and participation, (iv) Knee osteoarthritis has a social impact5, (v) Knee osteoarthritis has an emotional impact, (vi) Interactions with health professionals can be positive or negative and (vii) Knee osteoarthritis leads to life adjustments. Themes were consistent between studies that included people with severe osteoarthritis and mild-to-moderate osteoarthritis. The study including cares (family members of the participants from one trial), captured six of the seven major themes, with no new themes identified by cares.

The perceived causes of knee osteoarthritis are multifactorial and lead to structural damage to the knee and deterioration over time

Thirteen studies reported what participants perceived the causes of knee osteoarthritis were.24–28 32–35 37 38 42 43 Perceived cause of knee osteoarthritis included internal factors (eg, being overweight, family history of osteoarthritis, ageing, working in occupations requiring heavy manual work such as extensive kneeling or lifting, past sporting activities and menopause) and external factors (eg, trauma and the weather). Participants perceived knee osteoarthritis as preventable or partially attributable to actions or incidents that were modifiable (eg, pushing too far or knee injury) had they changed their behaviour earlier in life. Participants in four studies expressed strong beliefs and concerns about their knee osteoarthritis being caused by structural deterioration25 28 33 34 using language such as ‘bone on bone’ with the joint worn away by movement. Carers of people with knee osteoarthritis attributed the cause of their relative’s knee osteoarthritis to ageing, working too hard or to unknown causes.42

The prognosis of knee osteoarthritis was discussed by participants in six studies.26 28 32–35 Participants believed their symptoms would get worse over time as knee osteoarthritis was ‘a progressive degenerative disease’ and could not be ‘cured’. However, participants in one study35 also felt they could halt or slow the progression of their symptoms through diet and exercise.

Pain and how to manage it predominates the lived experience

The participants’ experience of pain and its management emerged as a theme in 19 studies.25–29 31–33 35–45 Pain was described by participants as the predominant ‘omnipresent’ feature of knee osteoarthritis. Pain was perceived to interrupt and deter daily activities such as walking, to make people less confident in their bodies and to slow people down. Participants in one study described two distinct patterns of pain: ‘mechanical’ pain described as ‘sharp’ pain related to discrete movements or activities, and ‘inflammatory’ pain described as a ‘burning’ pain which was more unpredictable and associated with the weather or prolonged activity.27 Pain was perceived as insurmountable when there was no foreseeable end to it and made some participants feel ‘old’. Carers reported their relatives with knee osteoarthritis rarely mentioned pain until they needed help.42 Participants reported managing their pain with medication but that this was not always a satisfactory strategy due to feelings of dependence, undesirable side-effects and only partial relief from symptoms. Other pain management strategies described were activity-related (including exercise, avoidance of certain activities, brief rest, pacing and physiotherapy), psychological-related (having a positive life philosophy, humour, continuing to engage in pleasurable activities), passive treatment modalities (including ice, heat, massage, Chinese traditional medicine) and weight loss. Some believed joint replacement was inevitable and the only real solution for their pain.25 28 Similarly, carers of relatives with knee osteoarthritis believed the most promising method to reduce pain was a knee replacement, and often persuaded their relatives to see a doctor about having surgery.42 In contrast, participants from one study preferred a natural solution only as they had a negative perception of surgery and saw it as a last resort.43

Knee osteoarthritis impacts activity and participation

Participants in 16 studies reported functional limitations due to their knee osteoarthritis particularly mobility restrictions.25–29 31 32 35–42 45 Participants predominantly reported limitations in movements involving weight-bearing such as standing, stair climbing, squatting, carrying, lifting, kneeling, bending; limitations in self-care activities such as dressing, toileting, sleeping, cooking; limitations in leisure pursuits such as walking, gardening, sport and other forms of exercise, and a fear of falling. Living with knee osteoarthritis was reported by participants to reduce their physical activity and exercise, and to become sedentary. Participants described the impact on physical activities and associated this with the severity of their knee osteoarthritis. The combined consequences of pain and functional limitations was an inability for some participants to participate in paid employment, or a reduction in work hours affecting household income, or other impacts on work such as requiring modifications, tiring easily or being less efficient. For others, living with knee osteoarthritis meant a loss of independence, and a loss of sleep.28

Knee osteoarthritis has a social impact

Participants in 10 studies felt their knee osteoarthritis had a substantial social impact.27 29 34–36 38–41 45 It limited their ability to stay socially connected because of reduced participation in leisure activities and because of difficulties with taking public transport. For some participants, the inability to take part in socially-based physical activity, such as walking with friends or playing sport was the most difficult aspect of this condition. Participants described social isolation marked by doing fewer activities outside of home. Participants felt mobility limitations made it conspicuous to others that they had poor health. Living with knee osteoarthritis reduced their enjoyment of activities, particularly when travelling. Others described a change in their social relationships conveying that they related more to older individuals with health problems. Participants also described the repercussions of knee osteoarthritis on family life, reporting difficulties taking care of the family including looking after grandchildren and playing with their children.

Knee osteoarthritis has an emotional impact

Thirteen studies reported data on the emotional impact participants said they experienced as a result of having knee osteoarthritis.25–29 31 32 35 36 40–42 45 Living with knee osteoarthritis was described as being ‘difficult’ and often described as having a negative impact on the participant’s mood, resulting in feelings of loss, anxiety, inadequacy, frustration, irritability, emotional distress, depression, embarrassment, fear for the future and uncertainty of the outcomes of knee pain. Carers reported their relatives with knee osteoarthritis could lose their temper easily when experiencing severe pain.42 Some participants reported their mobility limitations in particular devalued their sense of self-worth because mobility was integral to their identity. Living with knee osteoarthritis made them feel like ‘a partial person’, ‘less valuable’ and losing their identity, since they had to give up something that was part of their normal life. Other participants talked of a reduced sense of control or of being ‘lost’ after being ‘told’ to eliminate athletic activities and change their lifestyles. Other participants reported grieving for activities they could no longer take part in, or their vision of ageing. Participants in one study27 felt the unpredictability and uncertainty of living with knee osteoarthritis caused the most stress. While participants in another study40 said they dreamed of regaining their previous level of physical activity, their knee was a major barrier to achieving their dreams.

Interactions with health professionals can be positive or negative

Eleven studies explored the interactions people with knee osteoarthritis described having with health professionals.24 25 31–33 35 41 43–46 Participants said the impact of their diagnosis was a positive step towards successful management; although for people with low expectations of treatment, the impact of their diagnosis resulted in limited contact with health professionals. Participants who had positive interactions with health professionals described being listened to, being offered hope for the future and being provided with recommendations for managing knee osteoarthritis including weight loss and exercise. Participants who had negative experiences interacting with health professionals described their dissatisfaction with receiving limited information about their condition and the management options available including ways to avoid aggravating their condition, a sense of not being listened to, not being given sufficient attention or not understanding the information provided to them. For example, in one study35 participants recounted how their symptoms were viewed by health professionals as something that could not be changed, which they ‘just had to live with’ or were dismissed as an inevitable part of ageing.

Knee osteoarthritis leads to life adjustments

Fourteen studies25 27–29 31 32 34 35 37 39–42 45 reported participants’ descriptions of adjusting to having knee osteoarthritis in terms of role changes or modifications, ownership of their health management, awareness of their condition and developing coping strategies. Participants described taking measures to alleviate their symptoms and protect their knee joint including lifestyle adjustments by keeping active and controlling their weight, adapting their work, modifying activities or postures to manage everyday routines (eg, climbing stair less frequently and looking for escalators, not carrying heavy things, planning ahead, looking for places to sit, avoiding situations whereby pain would be intolerable and avoiding public transport) and seeking out health-related information. In one study,28 participants described living with knee osteoarthritis as a balancing act recognising the health benefits from being physically active as well as beliefs about further joint deterioration and pain. Two studies29 39 described a ‘tipping point’ whereby participants arrived at the point where they were giving up all their enjoyable activities with an extensive feeling of loss, and felt their best option was a knee replacement.

Discussion

This systematic review provides insights into the experience of living with knee osteoarthritis as described by the seven emergent themes. While the experience of persistent pain and disability were the main features of everyday living with knee osteoarthritis, psychological and social factors such as emotional distress, loss of social contact and fear for the future were commonly expressed concerns of the participants. Other common views were the perceptions of knee osteoarthritis as an inevitable part of ageing, attributing their osteoarthritic knee to ‘wear and tear’ and finding ways to adjust their lives until they reach the ‘tipping point’ characterised by a perceived need for a knee replacement. A theme highlighted was unsatisfying relationships between people with knee osteoarthritis and healthcare professionals if there was limited information about the knee osteoarthritis and effective management options. Importantly, patient and health professional interactions were also perceived to provide a positive step towards effective management, particularly when health professionals listened to their patients, conveyed hope for the future and provided recommendations for managing knee osteoarthritis.

This review, comprising data from 21 studies involving 665 people with knee osteoarthritis and 28 carers, adds to the literature by highlighting the magnitude of the psychosocial impact of living with knee osteoarthritis that permeates all aspects of life. A previous systematic review of the experience of hip and knee osteoarthritis focussed on the functional impacts of osteoarthritis, as well as people’s lack of understanding and the stigma of their disease.16 One small previous review of nine studies focussed on the lived experience of knee pain, but did not limit this to osteoarthritis.17 While the assessment of the lived experience of a health condition should be disease-specific,47 the finding by Wride that ‘knee pain affects every aspect of life, redefining what people are able to do, who they do it with and how they do it’ complements our findings among people with knee osteoarthritis.

The anxiety, depression and feeling of hopelessness that we identified in our review only recently received attention in published clinical practice guidelines. For example, clinical practice guidelines for management of knee and hip osteoarthritis48 49 emphasise the importance of a holistic assessment to ascertain the impact of osteoarthritis on the whole person. This includes specific recommendations for a psychosocial evaluation to identify unique factors that may affect a person’s quality of life and participation in usual activities, and to embed patient-centred care principles in the management of patients with knee osteoarthritis. Patient-centred care encourages patient participation in decision-making and communication with patients about their management options. Hence, offering a psychological intervention such as cognitive behavioural therapy13 may be important to improve the lived experience and self-management of osteoarthritis. Recent Australian clinical practice guidelines conditionally recommend offering cognitive behavioural interventions (eg, pain coping skills training) delivered by trained health professionals to people with knee osteoarthritis presenting with psychological impairments.48 Combined with exercise, the guidelines suggest these interventions may improve pain, self-efficacy, pain coping, depression and anxiety.48

Psychological and social factors such as emotional distress, concerns about disability and learning to live with pain have been identified among people living with other chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions.50 51 Some of the experiences of living with knee osteoarthritis we identified, such as the perception among the participants in the included studies that their condition was an inevitable part of ageing, the perceived poor prognosis due to the ‘progressive degenerative disease’ and the pre-occupation with the existing damage to their joint and their perceived need for surgery have also been recognised in people with low back pain.52 53 An explanation for the perception of ‘damage’ for people with knee osteoarthritis is likely to have been influenced by the results of imaging as well as the messages people receive from their health professionals.54 This highlights the importance that health professionals not only focus on reducing joint-related pain and improving function, but to also include strategies to dispel patient misconceptions about knee osteoarthritis.55 Strategies may include providing education that osteoarthritis is not a ‘wear and tear’ disease, that it does not necessarily worsen with ageing and that people can remain healthy and active with osteoarthritis.33 56 One strategy could be to apply audit and feedback which has been used to change clinician behaviour in the management of other clinical groups.57 Audit and feedback to health professionals could be applied to improve the education and language used to describe osteoarthritis, to overcome and dispel patient misconceptions as well as help patients participate in decisions about their management.58 It may also be important that carers are invited to be involved in conversations and education sessions with health professionals. This approach could potentially dispel carer misconceptions about the causes of osteoarthritis and its management, may be empowering for family members59 and may lead to improved patient adherence to treatment and better outcomes.

The overall findings highlight the importance of equipping patients and carers with information and self-management strategies to reduce the impact of knee osteoarthritis on their lives, beyond simply providing information about osteoarthritis. In particular to improve their psychosocial well-being, by reducing pain, maintaining function, increasing social and physical activity participation, helping patients to remain in employment and achieve optimal mental health. For example, one option to address patients’ harmful beliefs and attitudes towards pain and damage is to address the negative or mistaken language and beliefs about their knee through education. Emphasising facts such as ‘hurt does not equal harm’ and ‘exercise is safe’60 and dismissing myths such as ‘exercise is damaging’55 may be fundamental to alter people’s negative attitudes and may be best combined with interventions such as exercise programmes to potentially improve patients’ overall perception of their knee. Beliefs about a health condition are formed not only from personal experiences, but also from observing others and external sources of information such as the media. Thus, negative beliefs about knee osteoarthritis can predate the onset of the condition.61 Therefore, there may be a role for public health campaigns to dispel myths about knee osteoarthritis across society more broadly.

The main limitation of this systematic review was the exclusion of studies exploring patients’ perceptions of interventions they received such as exercise or perioperative management for knee osteoarthritis. These were excluded because experiences in response to biological interventions would be expected to be different from the daily experience of living with knee osteoarthritis (the focus of this review), and should be the subject of further study. Only one study reported carer perceptions about living with knee osteoarthritis. Although the themes identified in this single study converged with six of the seven themes, further enquiry may be required to confirm their perceptions. Further, given the pattern of recurring themes we identified, it is unlikely that the inclusion of subsequent studies would have substantially added to the themes we described in this review. Finally, exclusion of non-English language articles limits the generalisability as other cultures with other languages might have different perceptions of knee osteoarthritis.

Conclusion

This review highlighted the value of taking patient attitudes and experiences into account, consistent with patient-centred care, when planning and implementing management options for people with knee osteoarthritis. These findings could inform clinical practice guidelines, to help clinicians better understand the lived experience of knee osteoarthritis, optimise the patient-clinician interaction and provide insights into how patient education may be conducted. These findings could also lead to new research questions to address patients lived experience with knee osteoarthritis and interventions to target modifiable psychological and social factors.

bmjopen-2019-030060supp001.pdf (11.2KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JAW, NFT, SB, NS: contributed to the conception and design of the review, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, contributed to the writing of the paper by revising it critically for important intellectual content and read and approved the manuscript. Patients and public were not involved in this review.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Glyn-Jones S, Palmer AJR, Agricola R, et al. . Osteoarthritis. The Lancet 2015;386:376–87. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60802-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rayahin JE, Chmiel JS, Hayes KW, et al. . Factors associated with pain experience outcome in knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:1828–35. 10.1002/acr.22402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holla JFM, Sanchez-Ramirez DC, van der Leeden M, et al. . The avoidance model in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review of the evidence. J Behav Med 2014;37:1226–41. 10.1007/s10865-014-9571-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arendt-Nielsen L, Nie H, Laursen MB, et al. . Sensitization in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis. Pain 2010;149:573–81. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. . OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2014;22:363–88. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Briggs A, Page C, Shaw B, et al. . A model of care for osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: development of a system-wide plan for the health sector in Victoria, Australia. Hcpol 2018;14:47–58. 10.12927/hcpol.2018.25686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cubukcu D, Sarsan A, Alkan H. Relationships between pain, function and radiographic findings in osteoarthritis of the knee: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis 2012;2012:1–5. 10.1155/2012/984060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mannion AF, Kämpfen S, Munzinger U, et al. . The role of patient expectations in predicting outcome after total knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11 10.1186/ar2811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, et al. . Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:57–63. 10.1007/s11999-009-1119-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, et al. . What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. The Lancet 2018;391:2356–67. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30480-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O’Sullivan PB, Caneiro JP, O’Keeffe M, et al. . Cognitive functional therapy: an integrated behavioral approach for the targeted management of disabling low back pain. Phys Ther 2018;98:408–23. 10.1093/ptj/pzy022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Henschke N, Ostelo RWJG, van Tulder MW, et al. . Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane DB Syst Rev 2010;49 7 10.1002/14651858.CD002014.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang L, Fu T, Zhang Q, et al. . Effects of psychological interventions for patients with osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Health Med 2018;23:1–17. 10.1080/13548506.2017.1282160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bennell KL, Ahamed Y, Jull G, et al. . Physical therapist-delivered pain coping skills training and exercise for knee osteoarthritis: randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res 2016;68:590–602. 10.1002/acr.22744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thorne S. Toward methodological emancipation in applied health research. Qual Health Res 2011;21:443–53. 10.1177/1049732310392595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith TO, Purdy R, Lister S, et al. . Living with osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. Scand J Rheumatol 2014;43:441–52. 10.3109/03009742.2014.894569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wride JM, Bannigan K. ‘If you can’t help me, so help me God I will cut it off myself…’ The experience of living with knee pain: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Physiotherapy 2018;104:299–310. 10.1016/j.physio.2018.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hubertsson J, Turkiewicz A, Petersson IF, et al. . Understanding occupation, sick leave, and disability pension due to knee and hip osteoarthritis from a sex perspective. Arthritis Care Res 2017;69:226–33. 10.1002/acr.22909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. . Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:181 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. CASP (systematic review) , 2018. Available: http://www.casp-uk.net/ [Accessed Nov 7, 2018].

- 21. Synnott A, O’Keeffe M, Bunzli S, et al. . Physiotherapists may stigmatise or feel unprepared to treat people with low back pain and psychosocial factors that influence recovery: a systematic review. J Physiother 2015;61:68–76. 10.1016/j.jphys.2015.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Egerton T, Diamond LE, Buchbinder R, et al. . A systematic review and evidence synthesis of qualitative studies to identify primary care clinicians' barriers and enablers to the management of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2017;25:625–38. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York.: Springer Publishing Company Inc, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Victor CR, Ross F, Axford J. Capturing lay perspectives in a randomized control trial of a health promotion intervention for people with osteoarthritis of the knee. J Eval Clin Pract 2004;10:63–70. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2003.00395.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tallon D, Chard J, Dieppe P. Exploring the priorities of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2000;13:312–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ahmad MA, Singh DKA, Qing CW, et al. . Knee osteoarthritis and its related issues: patients’ perspective. Malays J Health Sci 2018;16:171–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chan KKW, Chan LWY. A qualitative study on patients with knee osteoarthritis to evaluate the influence of different pain patterns on patients’ quality of life and to find out patients’ interpretation and coping strategies for the disease. Rheumatol Rep 2011;3:3–15. 10.4081/rr.2011.e3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Darlow B, Brown M, Thompson B, et al. . Living with osteoarthritis is a balancing act: an exploration of patients’ beliefs about knee pain. BMC Rheumatol 2018;2 10.1186/s41927-018-0023-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hall M, Migay A-M, Persad T, et al. . Individuals’ experience of living with osteoarthritis of the knee and perceptions of total knee arthroplasty. Physiother Theory Pract 2008;24:167–81. 10.1080/09593980701588326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sitzia J, Wood N. Patient satisfaction: a review of issues and concepts. Soc Sci Med 1997;45:1829–43. 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00128-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carmona-Terés V, Moix-Queraltó J, Pujol-Ribera E, et al. . Understanding knee osteoarthritis from the patients’ perspective: a qualitative study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2017;18:225 10.1186/s12891-017-1584-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pouli N, Das Nair R, Lincoln NB, et al. . The experience of living with knee osteoarthritis: exploring illness and treatment beliefs through thematic analysis. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36:600–7. 10.3109/09638288.2013.805257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hendry M, Williams NH, Markland D. Why should we exercise when our knees hurt? A qualitative study of primary care patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Fam Pract 2006;23:558–67. 10.1093/fampra/cml022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Morden A, Jinks C, Ong BN. Lay models of self-management: how do people manage knee osteoarthritis in context? Chronic Illn 2011;7:185–200. 10.1177/1742395310391491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. MacKay C, Sale J, Badley EM, et al. . Qualitative study exploring the meaning of knee symptoms to adults ages 35-65 years. Arthritis Care Res 2016;68:341–7. 10.1002/acr.22664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Xie F, Li S-C, Fong K-Y, et al. . What health domains and items are important to patients with knee osteoarthritis? A focus group study in a multiethnic urban Asian population. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2006;14:224–30. 10.1016/j.joca.2005.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kao M-H, Tsai Y-F. Illness experiences in middle-aged adults with early-stage knee osteoarthritis: findings from a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 2014;70:1564–72. 10.1111/jan.12313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Al-Taiar A, Al-Sabah R, Elsalawy E, et al. . Attitudes to knee osteoarthritis and total knee replacement in Arab women: a qualitative study. BMC Res Notes 2013;6:406 10.1186/1756-0500-6-406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Man A, Davis A, Webster F, et al. . Awaiting knee joint replacement surgery: an occupational perspective on the experience of osteoarthritis. Journal of Occupational Science 2017;24:216–24. 10.1080/14427591.2017.1315832 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nyvang J, Hedström M, Gleissman SA. It's not just a knee, but a whole life: A qualitative descriptive study on patients’ experiences of living with knee osteoarthritis and their expectations for knee arthroplasty. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2016;11:30193 10.3402/qhw.v11.30193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Keysor JJ, Sparling JW, Riegger-Krugh C. The experience of knee arthritis in athletic young and middle-aged adults: an heuristic study. Arthritis Care Res 1998;11:261–70. 10.1002/art.1790110407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hsu KY YFT, Lin YP, Liu HT. Primary family caregivers' observations and perceptions of their older relatives' knee osteoarthritis pain and pain management: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:2119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Figaro MK, Russo PW, Allegrante JP. Preferences for Arthritis Care Among Urban African Americans: "I Don't Want to Be Cut". Health Psychology 2004;23:324–9. 10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Alami S, Boutron I, Desjeux D, et al. . Patients' and practitioners' views of knee osteoarthritis and its management: a qualitative interview study. PLoS One 2011;6:e19634 10.1371/journal.pone.0019634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Maly MR, Krupa T. Personal experience of living with knee osteoarthritis among older adults. Disabil Rehabil 2007;29:1423–33. 10.1080/09638280601029985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kao M-H, Tsai Y-F. Living experiences of middle-aged adults with early knee osteoarthritis in prediagnostic phase. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:1827–34. 10.3109/09638288.2012.665127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bakas T, McLennon SM, Carpenter JS, et al. . Systematic review of health-related quality of life models. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:134 10.1186/1477-7525-10-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Guideline for the management of knee and hip osteoarthritis , 2018. Available: https://www.racgp.org.au/download/Documents/Guidelines/Musculoskeletal/guideline-for-the-management-of-knee-and-hip-oa-2nd-edition.pdf [Accessed Dec 19 2018].

- 49. Osteoarthritis: Care and management. UK , 2014. Available: https://nice.org.uk/guidance/cg177; [Accessed Accesed Nov 7 2018].

- 50. Maher C, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Non-Specific low back pain. The Lancet 2017;389:736–47. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30970-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bunzli S, Watkins R, Smith A, et al. . Lives on hold: a qualitative synthesis exploring the experience of chronic low-back pain. Clin J Pain 2013;29:907–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Darlow B, Fullen BM, Dean S, et al. . The association between health care professional attitudes and beliefs and the attitudes and beliefs, clinical management, and outcomes of patients with low back pain: a systematic review. EJP 2012;16:3–17. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Darlow B, Forster BB, O'Sullivan K, et al. . It is time to stop causing harm with inappropriate imaging for low back pain. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:414–5. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Barker KL, Reid M, Minns Lowe CJ. What does the language we use about arthritis mean to people who have osteoarthritis? A qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36:367–72. 10.3109/09638288.2013.793409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bunzli S, O'Brien P, Ayton D, et al. . Misconceptions and the acceptance of evidence-based nonsurgical interventions for knee osteoarthritis. A qualitative study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2019:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gay C, Eschalier B, Levyckyj C, et al. . Motivators for and barriers to physical activity in people with knee osteoarthritis: a qualitative study. Joint Bone Spine 2018;85:481–6. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vratsistas-Curto A, McCluskey A, Schurr K. Use of audit, feedback and education increased guideline implementation in a multidisciplinary stroke unit. BMJ Open Qual 2017;6:e000212 10.1136/bmjoq-2017-000212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, et al. . Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane DB Syst Rev 2012;154 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lawler K, Taylor NF, Shields N. Family-assisted therapy empowered families of older people transitioning from hospital to the community: a qualitative study. J Physiother 2019;65:166–71. 10.1016/j.jphys.2019.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Quicke JG, Foster NE, Thomas MJ, et al. . Is long-term physical activity safe for older adults with knee pain?: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2015;23:1445–56. 10.1016/j.joca.2015.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Leventhal H, Phillips LA, Burns E. The Common-Sense model of self-regulation (CSM): a dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. J Behav Med 2016;39:935–46. 10.1007/s10865-016-9782-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Clarke SP, Moreton BJ, das Nair R, et al. . Personal experience of osteoarthritis and pain questionnaires: mapping items to themes. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36:163–9. 10.3109/09638288.2013.782364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. MacKay C, Jaglal SB, Sale J, et al. . A qualitative study of the consequences of knee symptoms: 'It's like you're an athlete and you go to a couch potato'. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006006 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. MacKay C, Badley EM, Jaglal SB, et al. . “We're All looking for solutions”: a qualitative study of the management of knee symptoms. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:1033–40. 10.1002/acr.22278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nio Ong B, Jinks C, Morden A. The hard work of self-management: living with chronic knee pain. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2011;6:7035 10.3402/qhw.v6i3.7035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030060supp001.pdf (11.2KB, pdf)