Abstract

Introduction

Canadians report persistent problems accessing primary care despite an increasing per-capita supply of primary care physicians (PCPs). There is speculation that PCPs, especially those early in their careers, may now be working less and/or choosing to practice in focused clinical areas rather than comprehensive family medicine, but little evidence to support or refute this. The goal of this study is to inform primary care planning by: (1) identifying values and preferences shaping the practice intentions and choices of family medicine residents and early career PCPs, (2) comparing practice patterns of early-career and established PCPs to determine if changes over time reflect cohort effects (attributes unique to the most recent cohort of PCPs) or period effects (changes over time across all PCPs) and (3) integrating findings to understand the dynamics among practice intentions, practice choices and practice patterns and to identify policy implications.

Methods and analysis

We plan a mixed-methods study in the Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Ontario and Nova Scotia. We will conduct semi-structured in-depth interviews with family medicine residents and early-career PCPs and analyse survey data collected by the College of Family Physicians of Canada. We will also analyse linked administrative health data within each province. Mixed methods integration both within the study and as an end-of-study step will inform how practice intentions, choices and patterns are interrelated and inform policy recommendations.

Ethics and dissemination

This study was approved by the Simon Fraser University Research Ethics Board with harmonised approval from partner institutions. This study will produce a framework to understand practice choices, new measures for comparing practice patterns across jurisdictions and information necessary for planners to ensure adequate provider supply and patient access to primary care.

Keywords: primary health care; health workforce; graduate medical education; mixed methods, family medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will generate new information about changes within the physician workforce, and will inform what policy options might alter practice choices, and by extension, service supply.

This study combines the richness of qualitative data with longitudinal, population-based, quantitative data from multiple provinces to address a clear knowledge gap.

We anticipate our results will inform future research, particularly as there are very few studies examining practice intentions and choices of primary care physicians.

This study focuses on changes in services delivered by physicians but does not examine alignment with patient or populations needs, an important topic for future inquiry.

This study focuses only on family physicians, but may inform specification of more optimal roles for nurse practitioners or other primary care providers to strengthen primary care.

Introduction

Paradox of primary care ‘shortage’ in Canada

The proportion of Canadians without a regular healthcare provider has grown over time1 and Canadians struggle to access primary care when they need it,2 despite historically high ratios of primary care providers to population.3 As physician supply has grown, so has the age of Canada’s population and the complexity of care it is receiving, but not at rates that explain the gap between physician supply and patient access.4 Understanding the gap between growing per-capita physician supply and apparent unmet patient need is an urgent priority.

The majority of Canadian primary care physicians (PCPs) are private providers paid fee-for-service by provincial health insurers.5 PCPs have considerable autonomy and a wide array of practice options available. There is speculation that practice patterns among early-career PCPs are different now compared with earlier cohorts.6–8 Here, practice patterns refer to both volume and type of services provided. Early-career PCPs physicians may now be working fewer hours, providing less direct patient care and/or providing different services, as they choose options other than more traditional, comprehensive family medicine (eg, practice with a specialised clinical focus, walk-in practice and hospitalist care). Previous research has examined factors shaping choice of primary care as a speciality, but not choice of practice within primary care. Existing models used in health workforce planning focus on the type of services each provider is competent to provide, but not what they choose to provide, and implicitly assume that practice patterns are homogenous across cohorts and static over time.9–12

Growth in walk-in style practice may explain patients’ reported inability to find a ‘regular’ family physician. In most Canadian provinces there is no formal rostering of patients, so physicians may provide urgent, episodic care without maintaining a defined patient panel. In effect, walk-in practice may provide access, but not continuity of care or coordination. Cross-sectional analysis shows that younger doctors are more likely to have practice patterns suggesting walk-in style practice than older doctors during the same time period13 and there appear to be shifts in practice style over time among all physicians,14 but whether change has been more rapid among recent cohorts is unknown.

Physicians may also be choosing to further specialise within family medicine, focusing their practices on clinical areas such as sports medicine, addictions, palliative care or obstetrics, as well as practicing in emergency departments or as hospitalists.15 A 2015 survey of final-year family medicine residents found a third planned to focus only on a specific clinical area, and two-thirds planned to include a special interest as part of more comprehensive primary care.16 How these plans will translate into practice is not known, though one US study found more even more limited scope once in practice than was intended during residency.17 Existing Canadian data track family medicine residents who switch speciality, but not those who practice within family medicine with a focused clinical interest.18

In short, there are suggestions that PCP practice patterns are changing, but observations of changing practice patterns may conflate the influence of period effects (changes over time across all PCPs) and cohort effects (changes unique to early-career PCPs). There is evidence that service volume is falling across all physicians,19–21 and that the types of services provided differs between early-career and established physicians13 14 17 22 but whether differences are growing wider over time (ie, whether there are both cohort and period effect) is unknown.

Factors that may shape practice intentions, choices and patterns

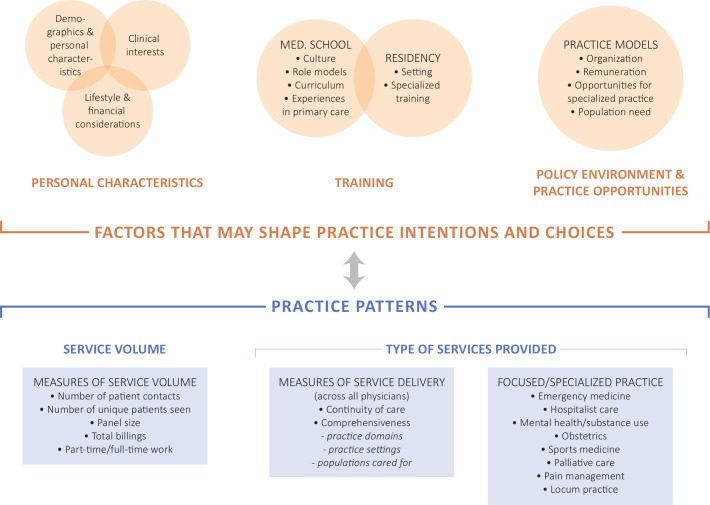

To make sense of changing practice patterns we need to understand what factors shape practice intentions and choices among family residents and early career physicians. This information can also inform what options and supports might alter practice choices in ways that increase the accessibility of services for patients. A substantial body of literature examines factors related to choice of family medicine as a speciality among medical students,23–35 however no research exists on factors shaping choice of practice style within primary care among residents and early-career physicians. Here we describe the literature on factors shaping choice of primary care speciality, and consider how these may also apply to choice of practice style within primary care. Figure 1 summarises these potential factors.

Figure 1.

Factors that may shape practice intentions, choices and patterns.

Personal characteristics

Physician demographics and personal characteristics (eg, gender, age, relationship status, nature of partner’s employment, parenthood), stated interests and values related to clinical practice (eg, interests in varied scope of practice, diversity of patients, value of relationships, holism, continuity, social orientation), as well as preferences for lifestyle and financial attributes of practice (eg, flexibility, job security, work-life balance, income expectation) predict whether students choose family medicine.23 24 28–31 The transitions from medical student into residency and from residency into practice present very different challenges.36 37 The degree to which personal characteristics influencing choice of speciality also shape practice intentions in residency and ultimate choice of practice remains unknown.

Training

Academic culture, availability of role models and curricular elements have been said to contribute to a ‘hidden curriculum’ that discourages choice of family medicine, and could plausibly shape a desire to specialise within primary care among those who choose family medicine.23 32–35 Mentorship and exposure to a range of practice settings within primary care may be important for choosing family medicine,23 32–35 and also subsequent practice style.

Within residency there are a growing number of opportunities to obtain specialised training and in some cases credentials in a focused clinical area.25 26 For example, residents who train in family medicine may be planning to pursue emergency medicine, with no intention of general practice.27 There are numerous enhanced skills programme such as addiction medicine, chronic pain and hospital medicine, and in some cases it is possible for residents and practising physicians to obtain certificates of added competence.38

Policy environment and practice models available

Though not a focus within the literature on choice of speciality, practice patterns are also fundamentally determined by the policy environment and practice models available to early-career physicians where and when they enter practice. For example, in Ontario the majority of PCPs practice within a model that delivers comprehensive primary care with some form of blended payment, while in British Columbia (BC) and Nova Scotia (NS) most physicians are in independent fee-for-service practice, and there are more limited mechanisms in place to support team-based care, formal patient enrolment and involvement of non-physician primary care providers.39–41

In conjunction with available practice models, attributes of clinical work (eg, patient population, degree of collaboration with other providers, type of Electronic Medical Record) as well as practical considerations (eg, degree of administrative responsibility, volume and flexibility of hours, level of compensation, predictability of compensation and attributes of geographical location) may shape practice choices. Surveys in Canada and internationally have found new graduates favour group physician or team-based practice42 43 as well as non-fee-for service practice models.43 44 A recent qualitative study examined generational change in rural general practice and identified the need to provide flexible working arrangements with varying support and financial models.45 However, much more information is needed to understand how practice opportunities shape decision-making, and how available models align with the values and preferences of early-career physicians. Existing survey data do not allow in-depth exploration of preferences and values underlying stated practice intentions.

Goal and objectives

The overarching goal of this study is to inform primary care workforce planning and policy by generating new information about the physician workforce with a focus on early-career PCPs.

Specific objectives are to:

Identify the values and preferences, including attributes of clinical, lifestyle and financial considerations that shape the intentions and choices of family medicine residents and early career PCPs (<10 years in practice).

Compare the practice patterns of early-career and established (10+ years) PCPs to determine if changes over time reflect cohort effects (attributes unique to the most recent cohort of PCPs), or period effects (changes over time across all PCPs).

Understand the dynamics between practice intentions, practice choices and practice patterns of early career physicians to inform workforce planning and identify other promising targets for policy intervention.

Patient and public involvement

This project adheres to the definition of patient-oriented research articulated under Canada’s Strategy for Patient Oriented Research (SPOR) as a continuum of research that focuses on patient-identified priorities, engages patients as partners and improves patient outcomes. In a SPOR-funded project patients and physicians identified a lack of regular primary care providers as the top research priority in British Columbia. This project will inform this topic directly by helping to understand the gap between growing per-capita supply of primary care providers and patient experiences of limited access. Members of the BC Primary Healthcare Research Network Patient Advisory are consulting at all stages of project development. Advisors have reviewed data analysis plans, will assist in interpretation of findings as they emerge and provide input on directions for future research. We have chosen an advisory model that will incorporate the perspectives of patients with a range of healthcare needs, living in different geographical settings and with a diverse mix of socio-demographic backgrounds, to reflect the diversity of patients who use primary care. This study is about health workforce planning and patient outcomes will not be measured directly. However, the information it will produce will inform policies that will ultimately support strengthened primary care and improved access for patients.

Methods and analysis

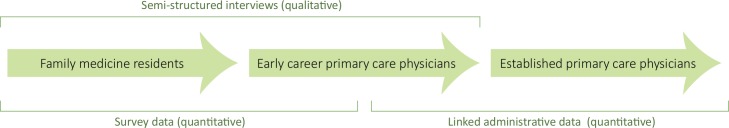

We employ a fully integrated mixed methods design.46 47 We will investigate Objective 1 using qualitative and quantitative methods; data for this objective consist of semi-structured, in-depth interviews with family medicine residents and early-career physicians and surveys of family medicine residents in each province during, immediately after and 3 years after residency (figure 2). We will investigate Objective 2 using quantitative methods; data for this objective consists of linked administrative health data to compare practice patterns across physicians within each province. Objective 3 will consist of meta-inferences46 47 integrating the results and inferences from Objectives 1 and 2. Our study design treats qualitative and quantitative methods with equal status. This is operationalised through two dominant arms (qualitative methods for Objective 1 and quantitative methods for Objective 2) and a third arm (quantitative methods for Objective 1) playing a supportive role. We operate from a transdisciplinary perspective through attention to collaboration within and across the study arms and being open to creating new concepts and approaches for our study.48–50

Figure 2.

Overlap of qualitative and quantitative data sources.

Objective 1: understand practice intentions and choices of family medicine residents and early-career PCPs

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews with individual family medicine residents and early-career physicians will be used to understand and explore factors shaping practice intentions and choices, including those identified in existing literature exploring choice of family medicine. Factors to be explored in interviews include preferences for specific aspects of clinical work (eg, patient population including demographic characteristics and complexity, types of services provided, interest in particular topics, degree of collaboration with other providers), values shaping practice more generally (eg, relationships, holism, continuity, social orientation), as well as practical considerations (eg, degree of administrative responsibility, volume and flexibility of hours, level and predictability of compensation, employment of partner/spouse). Interviews with physicians who have entered practice will also explore any changes in intentions throughout medical school and residency, and what factors shaped choice of practice on completion of residency. For both residents and early-career physicians, we will also explore plans moving forward, and the degree to which participants anticipate practice patterns will evolve over time.

We will conduct all interviews by telephone at a time that is convenient and acceptable for study participants. Telephone interviews have been shown to produce similar data richness for a lower cost when compared with in-person interviews51 52 and will allow us to reach a more geographically diverse set of participants in each of BC, Ontario (ON) and NS. Resident and early-career team research members have advised that telephone interviews will likely also work best for early career physicians’ and residents’ schedules. We expect each interview to last up to 60 min. An honorarium will be offered to compensate for time and lost income. Interviews will be conducted by Master’s or PhD trained qualitative research staff. They will be digitally recorded and transcribed.

As is usual in qualitative research, our sampling strategy is designed to generalise to concepts and theories rather than to populations.53 54 Accordingly, we will purposefully recruit residents and early career PCPs based on key characteristics identified in prior research, including personal characteristics (gender, relationship status, parenthood) and characteristics of residency training/practice setting (urban, rural or remote location; organisational model; focused/special interest practice). We will add to, and modify, our purposeful sampling strategy as we collect data and learn more about the factors that shape decision-making.53 55 56

We will recruit via email lists through all family medicine residency programme in the three study provinces as well as through newsletters sent by provincial medical associations. We will also post in the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) First Five Years Facebook group and use our contacts with training institutions and the College of Family Physicians of Canada to support recruitment efforts. Potential study participants will be asked to contact the study team by email or telephone and then to complete a screening questionnaire to ensure they meet the study inclusion criteria. The questionnaire will inform our purposeful sampling decisions (eg, demographics, practice/training location, practice type), and document the success of our various recruitment methods. We will draw on the details collected in the questionnaire during semi-structured interviews.

We plan sample sizes of 20 early-career physicians and 10 residents in each province for a total sample size of 90 across the three provinces. We expect that this sample size will allow us to reach saturation in each province as well as provide us with enough data to investigate potential differences by subgroups and by province.55 This sample size is also consistent with recommendations for a minimum of 30 to 50 interviews for similar study designs and recommendations for study-specific increases over minimum sample sizes to reflect multiple variations within the study, such as our three provinces.55–57

Interview data will be analysed using thematic analysis and framework analysis.58–60 Thematic analysis will occur concurrently with qualitative data collection. Analysis will consist of a line-by-line examination of interview transcripts to identify key themes.58 Constant comparison will also be used to compare and contrast themes from our data with concepts already in the literature.61 The thematic analysis will be used for detailed description of practice choice62 and as the initial stage of our framework analysis.59 60 Patterns within and between cases and themes will be used to develop a framework, or a typology of factors shaping practice choice. The typology will then be used to classify each interviewee and look for further patterns among early-career physicians and residents.59 60 We will explore variations by province and other subgroups as appropriate based on the data. NVivo software will be used. Multiple researchers from all three study provinces will be involved with coding and will participate in regular group analytical discussions to help ensure that the final analysis meets trustworthiness, validity and reliability criteria for qualitative research.63 64

Quantitative analysis of the national survey of resident physicians, administered by the College of Family Physicians of Canada

To enhance our understanding of practice intentions and choices, and triangulate findings using national data, this study will access survey data already being collected by the CFPC.65 The CFPC’s Family Medicine Longitudinal Survey is administered to all family medicine residents on paper or online, at three career points, starting in 2014:

T1: Residency entry survey: administered by university residency programme to all incoming family medicine residents within 3 months of starting the programme.

T2: Residency exit survey: administered to graduating residents within 3 months of exit.

T3: In practice survey: administered to family medicine physicians who graduated 3 years prior and who are registered in the CFPC membership database. The in-practice survey will be piloted in 2019.

Each wave of the survey captures the following personal characteristics as categorical variables: marital status, parenthood, sex, location of medical training and province of residency. The surveys ask about a range of practice models, including solo practice, group physician practice, interprofessional team-based practice, comprehensive care that includes a special interest and practice that focuses on specific clinical areas. The surveys also ask about practice in specific settings (eg, rural practice, emergency medicine, in-hospital care, long-term care), and clinical domains (eg, intrapartum care, mental healthcare, palliative care).

Analysis of the survey data will allow us to describe practice intentions and choices across all Canadian provinces, explore personal characteristics associated with practice intentions and triangulate findings from other data sources. We will use X2 tests and multivariate logistic regression to examine associations between personal characteristics and dichotomous measures of practice model, setting and clinical domains. Analysis of T1 and T2 data will begin in the first year of the study. Analysis of T3 will be added in 2019/2020 when these data are available.

Response rates for the CFPC resident surveys are relatively high (50% to 60%), but may decline for the in-practice survey. Though we will not be able to link survey data to administrative health data, we will be able to compare the characteristics of survey respondents and physicians in practice, and determine the degree to which self-reported practice patterns correspond, in aggregate, with observed practice patterns in administrative data. The likely bias among survey participants is that they are eager to share their experiences and they may not be representative of residents and early-career physicians. It is also possible that perceived social value or desirability of specific forms of practice (eg, comprehensive practice, home visits) may have biassed respondents and led to over-reporting of intentions. Administrative data covering all physicians will not be biassed in this way.

Objective 2: describe and compare observed practice patterns

We will use linked databases developed and housed separately in each province: Population Data BC (PopDataBC); Institute for Clinical Evaluative Science (ICES) in Ontario and Health Data Nova Scotia (HDNS). Within each province, de-identified data will be provided with unique patient and physician IDs that will enable us to connect individual-level records across administrative data sets and over time. It is neither possible nor necessary to combine record-level data across provinces, but parallel analysis using comparable definitions of variables and identical analytical procedures will permit us to compare across the three provinces. The following types of databases will be accessed in each province:

College of physicians and surgeons registry files

These are the registering and licensing body for physicians in each province. Data available from the Colleges will provide us with information on physician characteristics including age, gender, year of graduation, province or country of training, practice location and residency training to be used in descriptive analyses.

Physician payment information

This includes data on all fee-for-service claims and shadow-billed records documenting services delivered within salaried or capitated payment models, with anonymous identifiers for both patients and physicians. It describes services used, and includes a patient diagnosis code for each encounter. As primary care remains almost entirely fee-for-service in BC and NS, and shadow-billing is collected in ON, this provides rich information that can be used to classify the types of services provided.

Patient registration file for provincial insurer

This includes a record for all provincial residents who receive or are eligible to receive publicly-funded healthcare services, including descriptive information about individuals’ age, sex and regional health authority of residence.

Hospital separations files

This includes records of all inpatient and surgical day care discharges and deaths in hospital for provincial residents. Each record contains information on level of care, dates of admission and separation, codes for diagnoses and procedures and most responsible physician. This information will be used to capture the complexity of patient populations as well as to identify physicians acting as the most responsible provider to patients in hospital.

We will request data covering two decades of healthcare delivery, starting in 1996/1997 through to 2017/2018.

Develop comparable measures of practice patterns across provinces

Creating physician-level measures practice patterns (including practice volume, continuity and comprehensiveness) requires data fields from the provincial administrative databases as inputs and we will build on measures already used within individual provinces.13 14 22 66 Fields capturing service dates, dollars billed or using identical coding systems (eg, International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision and Tenth Revision diagnosis codes) are directly comparable across provinces. Other fields capture similar, but not directly comparable, information (eg, specific fee codes and service location codes). In cases where measures must rely on non-comparable fields, we will focus on differences between physicians or over time within as opposed to across provinces. This is a limitation of analysis using varying administrative data sources that does not undermine our primary objective of describing differences over time and among physicians.

Describe trajectories over the first 10 years of practice

As a first step, we will plot each individual measure of practice patterns over 10-year periods for physicians entering practice between 1997/1998 and 2007/2008. We have not defined a-priori what constitutes early-career. We are initially examining the first 10 years as we have no expectation of how measures may change year-to-year or how long it might take physicians to establish themselves in practice, observing when measures of service volume and other practice patterns stabilise over time. Once we have empirical evidence of a reasonable ‘entry to practice’ period we will use this to categorise years in practice. We will assign physicians to cohorts based on the year they entered practice and describe measures of practice patterns by assigned cohort and over time. We will also examine patterns stratified by physician characteristics, including sex and by place of graduation (Canada vs other countries), as in some provinces International Medical Graduates (IMGs – doctors who obtained their medical degrees outside of Canada) are subject to return for service agreements that require them to serve a defined patient group for a minimum period as well as by urban/rural practice location based on Statistics Canada’s Statistical Area Classification system.67

Analyse practice among primary care physicians by period and cohort

We will construct regression models for each measure of practice patterns (linear, logistical and Poisson/negative binomial, depending on the distribution of each measure). We will have annual data for each physician in each year they were in practice, and will include physician-level random effects. Models will include variables for number of years in practice, period (calendar year) and cohort (grouped by year of graduation). We expect physician age will be largely collinear with years in practice, but we will conduct sensitivity analysis adjusting for physician age. We will also include physician sex, urban/rural practice based on Statistics Canada’s Statistical Area Classification system67 and location of training (Canadian vs IMG) as covariates.

Population ageing and changing complexity of care are shaping practice patterns, but these effects are increasing needs gradually over time with no significant change in trend,4 and would therefore be captured by adjusting for period (annual) changes. Since the age and complexity of each individual physician’s patients is to some degree shaped by their practice choices (including where they practice), we will describe patient age and complexity at practice level but we will not adjust for these variables in analysis of other physician-level measures.

Objective 3: end-of-study meta-inferences about practice intentions, choices and patterns

Under Objective 3 we aim to understand the dynamics between practice intentions, practice choices and practice patterns of early career physicians. Current practice experiences and changing policy environments and practice opportunities may shape future practice choices and understanding practice dynamics can inform workforce planning and other promising targets for policy intervention. We will develop initial ‘meta-inferences’ (overall conclusions or understanding) by identifying where the results and inferences from qualitative and quantitative analysis complement and diverge from one another.47 Where possible, we will also explore linking qualitative and quantitative findings through cross-cutting themes and concepts and the use of visual joint displays of quantitative and qualitative data.68 We will then work to combine our integrative analyses across the entire study into a larger understanding of physician practice patterns.

Ethics and dissemination

We are taking an integrated knowledge translation approach.69 We have assembled a team that includes both early-career and established practitioners, medical educators, researchers and policymakers in both primary care and workforce planning. Stakeholder team members affirm the overarching need to understand the apparent gap between growing per-capita physician supply and unmet patient needs, and helped refine specific research objectives. We will present findings and seek feedback from stakeholders as findings emerge.

This study will also yield traditional academic outputs crossing multiple disciplines and disseminated to a range of audiences. This study will provide new information about changes within the physician workforce, and will inform what options and supports might alter practice choices, and by extension, physician supply. It will also help identify areas where new models of care or expanded roles for non-physician primary care providers may be needed. Many jurisdictions in Canada and internationally face similar challenges of ensuring access to primary care, coupled with changing physician demographics and ageing patient populations.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: RL wrote the first draft of the Introduction and Objective 2 methods. LG wrote the first draft of Objective 1 and 3 methods. AG, DR and EGM substantially revised the introduction, methods and analysis, and contributed to drafting Ethics and Dissemination. MA, DB, FB, RG, RG, SH, LH, JH-L, KH, MJ, TK, AM, MM, RM, KM, MM, CM, GM, TS, IS, DS, GT and SW provided feedback and revisions on the draft protocol and approved the final version for submission.

Funding: This study was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (R-PJT-155965).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study has received ethical approval from the Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics with harmonised approval from the University of British Columbia, the University of Ottawa, the University of Western Ontario, the University of Ontario Institute of Technology and the Nova Scotia Health Authority.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Statistics Canada Table 105-0508 - Canadian health characteristics, annual estimates, by age group and sex, Canada (excluding territories) and provinces, occasional. CANSIM (database) 2016.

- 2. CIHI How Canada Compares: Results From the Commonwealth Fund’s 2016 International Health Policy Survey of Adults in 11 Countries. Ottawa, ON: CIHI, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Supply C. Distribution and migration of Canadian physicians. Ottawa, ON: CIHI, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Evans RG. The sorcerer's Apprentices. Healthc Policy 2011;7:14–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Physicians in Canada, 2016: summary report. Ottawa: CIHI, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Glauser W, Tepper J. Can family medicine meet the expectations of millennial doctors ? Healthy Debate 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rowland K. The voice of the new generation of family physicians. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:6–7. 10.1370/afm.1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buddeberg-Fischer B, Stamm M, Buddeberg C, et al. . The new generation of family physicians--career motivation, life goals and work-life balance. Swiss Med Wkly 2008;138:305–12. doi:2008/21/smw-12103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Birch S, Kephart G, Murphy GT, et al. . Health human resources planning and the production of health: development of an extended analytical framework for needs-based health human resources planning. J Public Health Manag Pract 2009;15(6 Suppl):56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fereral/Provincial/Territorial Advisory Committee on Health Delivery and Human Resources (ACHDHR) A framework health human resources planning 2007.

- 11. Sing D, Lalani H, Kralj B, et al. . Ontario population needs-based physician simulation model. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Metrics SS, Intelligence H. Physician resource planning: a recommended model and implementation framework. Halifax: Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13. McGrail K, Lavergne R, Lewis SJ, et al. . Classifying physician practice style: a new approach using administrative data in British Columbia. Med Care 2015;53:276–82. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lavergne MR, Peterson S, McKendry R, et al. . Full-service family practice in British Columbia: policy interventions and trends in practice, 1991-2010. Healthc Policy 2014;9:32–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Glazer J. Specialization in family medicine education: abandoning our generalist roots. Fam Pract Manag 2007;14:13–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. The College of family physicians of Canada (CFPC) Family medicine longitudinal survey T2 (exit) results: aggregate findings across 15 family medicine residency programs. CFPC 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coutinho AJ, Cochrane A, Stelter K, et al. . Comparison of intended scope of practice for family medicine residents with reported scope of practice among practicing family physicians. JAMA 2015;314 10.1001/jama.2015.13734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Post-M.D PRW. Training in family medicine in Canada: continuity and change over a 15 year period. Canadian Post-M.D. Education Registry 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crossley TF, Hurley J, Jeon S-H. Physician labour supply in Canada: a cohort analysis. Health Econ 2009;18:437–56. 10.1002/hec.1378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hedden L, Barer ML, Cardiff K, et al. . The implications of the feminization of the primary care physician workforce on service supply: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health 2014;12:32 10.1186/1478-4491-12-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sarma S, Thind A, Chu M-K. Do new cohorts of family physicians work less compared to their older predecessors? the evidence from Canada. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:2049–58. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hedden L. Beyond full-time equivalents: gender differences in activity and practice patterns for BC’s primary care physicians. University of British Columbia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bennett KL, Phillips JP, Finding PJP. Finding, recruiting, and sustaining the future primary care physician workforce: a new theoretical model of specialty choice process. Acad Med 2010;85(10 Suppl):S81–S88. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4bae [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Scott I, Wright B, Brenneis F, et al. . Why would I choose a career in family medicine?: reflections of medical students at 3 universities. Can Fam Physician 2007;53:1956–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. The College of family physicians of Canada Section of family physicians with special interests or focused practices (SIFP): project status update. CFPC 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dhillon P. Shifting into third GEAR: current options and controversies in third-year postgraduate family medicine programs in Canada. Can Fam Physician 2013;59:e406–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shepherd LG, Burden JK. A survey of one CCFP-EM program's graduates: their background, intended type of practice and actual practice. CJEM 2005;7:315-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Connelly MT, Sullivan AM, Peters AS, et al. . Variation in predictors of primary care career choice by year and stage of training. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:159–69. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.01208.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kiolbassa K, Miksch A, Hermann K, et al. . Becoming a general practitioner--which factors have most impact on career choice of medical students? BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:25 10.1186/1471-2296-12-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Scott I, Gowans M, Wright B, et al. . Determinants of choosing a career in family medicine. Can Med Assoc J 2011;183:E1–E8. 10.1503/cmaj.091805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wright B. Career choice of new medical students at three Canadian universities: family medicine versus specialty medicine. Can Med Assoc J 2004;170:1920–4. 10.1503/cmaj.1031111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Block SD, Clark-Chiarelli N, Peters AS, et al. . Academia's chilly climate for primary care. JAMA 1996;276 10.1001/jama.1996.03540090023006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Parker JE, Hudson B, Wilkinson TJ. Influences on final year medical students' attitudes to general practice as a career. J Prim Health Care 2014;6:56–63. 10.1071/HC14056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Erikson CE, Danish S, Jones KC, et al. . The role of medical school culture in primary care career choice. Acad Med 2013;88:1919–26. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Beaulieu M-D, Rioux M, Rocher G, et al. . Family practice: professional identity in transition. A case study of family medicine in Canada. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:1153–63. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Westerman M, Teunissen PW, van der Vleuten CPM, et al. . Understanding the transition from resident to attending physician: a transdisciplinary, qualitative study. Acad Med 2010;85:1914–9. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181fa2913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Teunissen PW, Westerman M. Opportunity or threat: the ambiguity of the consequences of transitions in medical education. Med Educ 2011;45:51–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03755.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. The College of Family Physicians of Canada Certificates of Added Competence in Family Medicine [Internet]. Available: https://www.cfpc.ca/cac/ [Accessed 15 Mar 2019].

- 39. Hutchison B, Levesque J-F, Strumpf E, et al. . Primary health care in Canada: systems in motion. Milbank Q 2011;89:256–88. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00628.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Strumpf E, Levesque J-F, Coyle N, et al. . Innovative and diverse strategies toward primary health care reform: lessons learned from the Canadian experience. J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S27–S33. 10.3122/jabfm.2012.02.110215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Glazier RH, Klein-Geltink J, Kopp A, et al. . Capitation and enhanced fee-for-service models for primary care reform: a population-based evaluation. Can Med Assoc J 2009;180:E72–E81. 10.1503/cmaj.081316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lavergne MR, Scott I, Mitra G, et al. . Regional differences in where and how family medicine residents intend to practise: a cross-sectional survey analysis. CMAJ Open 2019;7:E124–E130. 10.9778/cmajo.20180152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gisler LB, Bachofner M, Moser-Bucher CN, et al. . From practice employee to (co-)owner: young GPs predict their future careers: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Fam Pract 2017;18:1–9. 10.1186/s12875-017-0591-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brcic V, McGregor M, Kaczorowski J. Practice and payment preferences of newly practising family physicians in British Columbia. Canadian Family Physician 2012;58:e2752–e281. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Snadden D, Kunzli MA. Working hard but working differently: a qualitative study of the impact of generational change on rural health care. CMAJ Open 2017;5:E710–E716. 10.9778/cmajo.20170075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Creamer EG. An introduction to fully integrated mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Teddlie C, Tashakkori A. Foundations of mixed methods research: integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in social and behavioral sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Archibald MM. Investigator triangulation: a collaborative strategy with potential for mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 2016;10:228–50. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Archibald MM, Lawless M, Harvey G, et al. . Transdisciplinary research for impact: protocol for a realist evaluation of the relationship between transdisciplinary research collaboration and knowledge translation. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021775 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hesse-Biber S. Doing interdisciplinary mixed methods health care research: working the boundaries, tensions, and synergistic potential of team-based research. Qual Health Res 2016;26:649–58. 10.1177/1049732316634304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Burke LA, Miller MK. Phone interviewing as a means of data collection: lessons learned and practical recommendations. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research 2001;2. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Drabble L, Trocki KF, Salcedo B, et al. . Conducting qualitative interviews by telephone: lessons learned from a study of alcohol use among sexual minority and heterosexual women. Qualitative Social Work: Research and Practice 2016;15:118–33. 10.1177/1473325015585613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods 4 edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. 3 edn Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2013: 360 p. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health 1995;18:179–83. 10.1002/nur.4770180211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Morse J. Designing funded qualitative research : Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 1994: 220–35. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Morse JM, Strategies A, Size S. Analytic strategies and sample size. Qual Health Res 2015;25:1317–8. 10.1177/1049732315602867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Aronson J. A pragmatic view of thematic analysis. The Qualitative Report 1995;2:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. . Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research : Bryman A, Burgess R, Analyzing qualitative data. London, UK: Routledge, 1994: 305–29. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2 edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000;23:334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lincoln YS, Guba EG, Pilotta JJ. Naturalistic inquiry. 9 Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications, 1985: 438–9. 10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mays N, Pope C. Rigour and qualitative research. BMJ 1995;311:109–12. 10.1136/bmj.311.6997.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Oandasan I. On behalf of the triple C competency based curriculum Task force. A national program evaluation approach to study the impact of triple C authors. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Marshall EG, Gibson RJ, Lawson B, et al. . Protocol for determining primary healthcare practice characteristics, models of practice and patient accessibility using an exploratory census survey with linkage to administrative data in nova Scotia, Canada. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014631 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Statistics Canada Statistical area classification (sac) 2015.

- 68. Guetterman TC, Fetters MD, Creswell JW. Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in health science mixed methods research through joint displays. Ann Fam Med 2015;13:554–61. 10.1370/afm.1865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bowen S, Graham ID. Integrated knowledge translation. knowledge translation in health care. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd 2013:14–23. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.