Abstract

Introduction

Evidence from low-income and middle-income countries suggests that migration status has an impact on health. However, little is known about the effect that migration status has on morbidity in sub-Saharan Africa. The aim of this study is to investigate the association between migration status and hypertension and diabetes and to assess whether the association was modified by demographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

Methods

A Quality ofLife survey conducted in 2015 collected data on migration status and morbidity from a sample of 28 007 adults in 508 administrative wards in Gauteng province (GP). Migration status was divided into three groups: non-migrant if born in Gauteng province, internal migrant if born in other South African provinces, and external migrant if born outside of South Africa. Diabetes and hypertension were defined based on self-reported clinical diagnosis. We applied a recently developed original, stepwise-multilevel logistic regression of discriminatory accuracy to investigate the association between migration status and hypertension and diabetes. Potential effect modification by age, sex, race, socioeconomic status (SES) and ward-level deprivation on the association between migration status and morbidities was tested.

Results

Migrants have lower prevalence of diabetes and hypertension. In multilevel models, migrants had lower odds of reporting hypertension than internal migrants (OR=0.86; 95% CI 0.78 to 0.95) and external migrant (OR=0.60; 95% CI 0.49 to 0.75). Being a migrant was also associated with lower diabetes prevalence than being an internal migrant (OR=0.84; 95% CI 0.75 to 0.94) and external migrant (OR=0.53; 95% CI 0.41 to 0.68). Age, race and SES were significant effect modifiers of the association between migration status and morbidities. There was also substantial residual between-ward variance in hypertension and diabetes with median OR of 1.61 and 1.24, respectively.

Conclusions

Migration status is associated with prevalence of two non-communicable conditions. The association was modified by age, race and SES. Ward-level effects also explain differences in association.

Keywords: migration status, prevalence, diabetes, hypertension and Gauteng province

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study population is part of a provincial representative sample on quality of life of adult residents in Gauteng province (GP).

The association between migration and health was analysed by applying, stepwise-multilevel logistic regression of discriminatory accuracy.

Migrants (both internal and external) had lower odds of both hypertension and diabetes than people born in Gauteng province.

Effect of migration status on health differed by age, race and socioeconomic status (SES).

However, residual confounding is possible due to data availability.

Introduction

Migration status is one of the important socioeconomic determinants of health.1 Migration is also associated with profound social, economic and cultural changes, which may affect the migrant’s health.2 Post the year 2005, more than 62% of the South African population were living in urban areas, with the rapid urbanisation being attributed to migration.3 4 The rapid urbanisation and increase in the urban poor in metropolitan areas of Gauteng province (GP), South Africa has become a major public health concern due to its linkage with increased disease burden.5 6

Migrants are heterogeneous both in their origin status and migration histories. Gauteng province attracts both internal and external migrants.3 4 Several studies on migration and morbidities have been done worldwide.1 2 7 Morbidities often present with low functioning level, poorer quality of life, increased healthcare utilisation and mortality rates.7 The age standardised global prevalence of diabetes has nearly doubled since 1980, from 4.7% to 8.5% in the adult population in 2014.8 In 2010, 31% of the global adult population had hypertension.9

The first South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES) reported the prevalence of 19.4% and 25.7% for diabetes and hypertension respectively in Gauteng province.10 However, information on the prevalence of these morbidities among different migrant status in South Africa is scanty. The prevalence of diabetes and hypertension in Gauteng province is high. Gauteng provides is home to many migrants. Therefore, a better understanding of the differences in morbidities according to different migration status is needed to target high risk groups in provision of services and to arrest the growing burden of certain diseases.

Study objectives

The study aims to:

Investigate the association between diabetes, hypertension and migration status in Gauteng province, South Africa.

To assess whether the association was modified by demographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

Methods

Study setting

Gauteng is the province with the largest population, estimated to be 12 272 263, despite having the smallest area; thus, it has the highest population density in South Africa of 675 people per km2.11 According to data from12 Gauteng province accounted for the highest concentration of international and internal migrants in South Africa, approximately 7.4% and 44%, respectively.12 The study population consists of all people residing permanently in Gauteng province who were aged 18 or older in 2015.

Data sources

We used data from the fourth Quality of Life (QoL) Survey conducted by Gauteng City Region Observatory (GCRO) in Gauteng province in 2015. The QoL survey has been conducted every 2 years since 2009 with the intention of providing up-to-date information on ‘a fast growing and dynamic urban region’ to support ‘better planning and management, and improved co-operative government relations’.13The QoL survey measured a wide range of variables including sociodemographic variables, migration status and self-reported health status from a sample of 28 007 adults in 508 administrative wards in Gauteng province. The data on ward-level migrant African population, African population, migrant Southern African Development Community (SADC) population, employed population, no income population, deprivation index (sampi) and average household size was obtained from Statistics South Africa (StatsSA).

Survey design

Simple random sampling was employed to select the respondents. Gauteng province consists of 10 municipalities and it is subdivided into 508 wards. Within these wards, there are small area levels (SALs) which were derived from the Population Census Enumerator Area polygons. SAL codes and geography were derived from the StatsSA Census 2011 report. The simple random sampling method was used to select the SALs from each ward, and then the minimum numbers of interviews for each ward were 30 and 60 interviews for those falling in district municipalities and metropolitan municipalities, respectively. The end result was that across the 508 wards, 28 456 successful interviews were completed, and these interviews were distributed across 16 400 SALs out of a total of 17 840 SALs. The ‘NEXT’ birthday method was used to select the respondents from the selected households. Data were collected via a digital data collection instrument using an open source system called Formhub and administered on a tablet device. Questionnaires were administered in the field and uploaded using internet connectivity to a cloud server from where they could be accessed and downloaded online.

Patient and public involvement

The development of the research questions and outcome measures were not informed by patients’ priority experiences and preferences. Patients were not involved in the design of this study. Patients were not involved in the recruitment and conduct of the study.

Outcome and independent variables

The main outcomes were hypertension and diabetes. The information on disease status, such as diabetes, hypertension, HIV, tuberculosis, influenza, and others, was collected in the QoL survey by asking question: “In the past 12 months, have you been told by health provider that you have one or more of the following conditions”. The morbidities were binary variables measuring the presence of the different morbidities, coded as 1 (or ‘Yes’) if the respondents self-reported the morbidity and as 0 (or ‘No’) if the respondent did not report the presence of a given morbidity.

Migration status was derived from the following QoL survey questions: (i) Were you born in Gauteng province or did you move into Gauteng province from another province or country?; (ii) When (year) did you move into Gauteng province?; (iii) Did you move to Gauteng province from a province in South Africa or from another country?; (iv) From which province did you move from into Gauteng province?; and (v) Which country did you move into Gauteng province from? Migration status then was divided into three groups: non-migrant, internal migrant and external migrant. The explanatory variables included sex, age, race, education, employment status, dwelling, total household income, grow own vegetables, medical aid, physical activity, household size, household food security and socioeconomic status quintile. Information collected included demographic and socioeconomic variables: sex (female, male); age (18 years and above); race (African, Coloured, Indian/Asian, White and Other); education was categorised into ‘no formal education’, grades R-7 ‘primary only’, grades 8–11 ‘secondary incomplete’, ‘matric’ grade 12 ‘more’ tertiary and above and ‘unspecified’ for those who didn’t specify; employment status (employed, unemployed and other).

Dwelling (formal, informal and other); total household income was categorised into ‘lower class income’ (<6400 Rand (ZAR) per month), ‘middle class income’ (R6400–R51 200 per month) and ‘upper class income’ (>R51 200 per month); grow own vegetables (do not grow own vegetables and grow their own vegetables); medical insurance was categorised into ‘medical insurance’ for respondents with either medical aid or a hospital plan and ‘no medical insurance’ for respondents without any of these; physical activity (never, hardly ever, few times a month, few times a week and everyday); household size (1–3, 4–6 and 7+); household food security (never, seldom, sometimes, often and always) and socioeconomic status quintile (richest, second, third, fourth and poorest). The ward level variables included migrant African population, African population, migrant SADC population, employed population, no income population, sampi and household of less than three.

Analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed to describe the migration status of the community by sociodemographic characteristics of study respondents using proportions. The prevalence of morbidities in Gauteng province, South Africa was estimated using proportions and presented as percentages with 95% CIs. Prevalence of morbidities was stratified by age, sex and migration status.

In the present analysis the data used was in multilevel structure as the respondents were within administrative wards.14 We applied a recently developed original, stepwise-multilevel logistic regression of discriminatory accuracy to investigate the effect of migration status. We fitted separate models for effect of migration status on diabetes and hypertension, respectively. Four progressively adjusted multilevel models were carried out: model 0 with no covariates; model 1 including only sociodemographic characteristics at the individual level; model 2 additionally analysing municipal deprivation as contextual variable and model 3 is the full adjusted model. The models were adjusted for years in GP, age, sex, race, dwelling, education level, household size, household head, physical activity, medical aid, grow own vegetables, household food security, sampi, year moved to GP and socioeconomic status quintile. Potential effect modification by age, sex, race, socioeconomic status (SES) and sampi was tested.

These variables were selected because they are strongly linked to migration status. There is evidence that migration is associated with age.12 The hypothesis is that effect of migration will be modified by age where young age will have protective effect hypertension and diabetes. There are also differential migration patterns by race and SES. In South Africa, race and SES are also strongly correlated.3 4 12 The other variables were treated as potential confounders.

To take account of the hierarchical data structure (level 1: individuals; level 2: administrative wards), an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and ward-level variances were reported for every model and for reasons of better interpretability, ward-level variances were converted into median ORs by applying the formula of Merlo et al.14 15 Multilevel logistic regression analyses with administrative wards as random intercepts were performed calculating ORs with their 95% CIs. ORs were plotted using the user-written coefplot Stata command.16 All analysis was performed using Stata V.13.

Results

Most respondents were non-migrants 18 027 (64%) and the external migrants constituted only 8% of the total respondents. Of the total study population of 28 007 respondents 14 966 (53%) were female (table 1). The majority of the respondents were aged between 18 and 27 years and were African 22 560 (81%). Most respondents 9152 (33%) had matric level of education and only 443 (1.6%) had no formal education. Close to half of the respondents were employed 13 582 (49%). The majority of the respondents stayed in formal dwellings 24 043 (86%). A large proportion of the respondents fall under the lower income bracket based on their total house hold income 13 015 (71%) lower class was defined in this study as families with a total household income of less than R6400 per month while 2.3% fall under the upper class (upper class is a family with an income more than R51 200). Few respondents reported growing their own vegetables 3480 (12%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study respondents by migration status

| Variable | Level | Non-migrants | Internal migrants | External migrants | Total |

| Sex | Female | 9746 (54.06) | 4226 (54.05) | 994 (46.00) | 14 966 (53.44) |

| Male | 8281 (45.94) | 3593 (45.95) | 1167 (54.00) | 13 041 (46.56) | |

| Age group | 18–27 | 5288 (29.33) | 2205 (28.20) | 701 (32.44) | 8194 (29.26) |

| 28–37 | 4400 (24.41) | 2197 (28.10) | 781 (36.14) | 7378 (26.34) | |

| 38–47 | 3362 (18.65) | 1507 (19.27) | 347 (16.06) | 5216 (18.62) | |

| 48–57 | 2456 (13.62) | 938 (12.00) | 159 (7.36) | 3553 (12.69) | |

| 58–67 | 1493 (8.28) | 503 (6.43) | 84 (3.89) | 2080 (7.43) | |

| 68+ | 1028 (5.70) | 469 (6.00) | 89 (4.12) | 1586 (5.66) | |

| Race | African | 13 819 (76.66) | 6901 (88.26) | 1 840 (85.15) | 22 560 (80.55) |

| Coloured | 940 (5.21) | 180 (2.30) | 9 (0.42) | 1129 (4.03) | |

| Indian/Asian | 389 (2.16) | 154 (1.97) | 75 (3.47) | 618 (2.21) | |

| White | 2848 (15.80) | 575 (7.35) | 157 (7.27) | 3580 (12.78) | |

| Other | 31 (0.17) | 9 (0.12) | 80 (3.70) | 120 (0.43) | |

| Education | No education | 223 (1.25) | 162 (2.10) | 58 (2.72) | 443 (1.60) |

| Primary only | 1621 (9.09) | 1029 (13.32) | 368 (17.23) | 3018 (10.90) | |

| Secondary incomplete | 5007 (28.08) | 2451 (31.73) | 712 (33.33) | 8170 (29.50) | |

| Matric | 6210 (34.83) | 2468 (31.95) | 474 (22.19) | 9152 (33.05) | |

| More | 4399 (24.67) | 1526 (19.76) | 419 (19.62) | 6344 (22.91) | |

| Unspecified | 371 (2.08) | 88 (1.14) | 105 (4.92) | 564 (2.04) | |

| Employment status | Employed | 8426 (47.08) | 3838 (49.48) | 1318 (61.47) | 13 582 (48.86) |

| Unemployed | 4808 (26.86) | 2282 (29.42) | 444 (20.71) | 7534 (27.10) | |

| Other | 4664 (26.06) | 1636 (21.09) | 382 (17.82) | 6682 (24.04) | |

| Dwelling | Formal | 16 478 (91.41) | 5954 (76.15) | 1611 (74.55) | 24 043 (85.85) |

| Informal | 1442 (8.00) | 1659 (21.22) | 482 (22.30) | 3583 (12.79) | |

| Other | 107 (0.59) | 206 (2.63) | 68 (3.15) | 381 (1.36) | |

| Total HH income | Lower class | 7991 (68.85) | 4000 (75.03) | 1024 (72.21) | 13 015 (70.90) |

| Middle class | 3325 (28.65) | 1246 (23.37) | 356 (25.11) | 4927 (26.84) | |

| Upper class | 291 (2.51) | 85 (1.59) | 38 (2.68) | 414 (2.26) | |

| Grow own vegetables | Do not grow vegetables | 15 850 (87.92) | 6772 (86.61) | 1905 (88.15) | 24 527 (87.57) |

| Grow vegetables | 2177 (12.08) | 1047 (13.39) | 256 (11.85) | 3480 (12.43) | |

| Medical aid | No medical insurance | 12 219 (71.26) | 5883 (78.44) | 1707 (82.66) | 19 809 (74.16) |

| Medical insurance | 4927 (28.74) | 1617 (21.56) | 358 (17.34) | 6902 (25.84) | |

| Physical activity | Never | 4478 (25.11) | 2481 (32.12) | 684 (32.02) | 7643 (27.60) |

| Hardly ever | 2357 (13.22) | 934 (12.09) | 271 (12.69) | 3562 (12.86) | |

| Few times a month | 2447 (13.72) | 851 (11.02) | 202 (9.46) | 3500 (12.64) | |

| Few times a week | 4356 (24.43) | 1687 (21.84) | 445 (20.83) | 6488 (23.43) | |

| Everyday | 4193 (23.52) | 1771 (22.93) | 534 (25.00) | 6498 (23.47) | |

| HH size | 1–3 | 9167 (51.41) | 4451 (57.63) | 1491 (69.80) | 15 109 (54.56) |

| 4–6 | 6736 (37.78) | 2631 (34.06) | 562 (26.31) | 9929 (35.86) | |

| 7+ | 1928 (10.81) | 642 (8.31) | 83 (3.89) | 2653 (9.58) | |

| HH food security | Never | 14 372 (79.72) | 6095 (77.95) | 1813 (83.90) | 22 280 (79.55) |

| Seldom | 1138 (6.31) | 496 (6.34) | 110 (5.09) | 1744 (6.23) | |

| Sometimes | 2008 (11.14) | 993 (12.70) | 199 (9.21) | 3200 (11.43) | |

| Often | 345 (1.91) | 147 (1.88) | 23 (1.06) | 515 (1.84) | |

| Always | 164 (0.91) | 88 (1.13) | 16 (0.74) | 268 (0.96) | |

| SES quintiles | Richest | 2716 (15.15) | 2136 (27.81) | 661 (31.12) | 5513 (19.88) |

| Second quintile | 3549 (19.79) | 1608 (20.93) | 398 (18.74) | 5555 (20.03) | |

| Third quintile | 3627 (20.23) | 1498 (19.50) | 368 (17.33) | 5493 (19.81) | |

| Fourth quintile | 3972 (22.15) | 1293 (16.83) | 346 (16.29) | 5611 (20.23) | |

| Poorest | 4066 (22.68) | 1146 (14.92) | 351 (16.53) | 5563 (20.06) | |

| Year moved to Gauteng | After 2009 | 1543 (19.74) | 673 (31.14) | 2216 (22.21) | |

| 2005–2009 | 1242 (15.89) | 589 (27.26) | 1831 (18.35) | ||

| 1995–2004 | 2524 (32.28) | 519 (24.02) | 3043 (30.49) | ||

| 1985–1994 | 1290 (16.50) | 217 (10.04) | 1507 (15.10) | ||

| Before 1985 | 1219 (15.59) | 163 (7.54) | 1382 (13.85) |

HH, Household.

Prevalent morbidities in Gauteng province

The overall prevalence of hypertension and diabetes was 15.5% (95% CI 15.1 to 15.9), 11.2% (95% CI 10.8 to 11.6), respectively (table 2). The prevalence of hypertension and diabetes was higher among non-migrants.

Table 2.

Prevalence of hypertension and diabetes

| Characteristics | Hypertension % (95% CI) | Diabetes % (95% CI) |

| Overall | 15.5 (15.1 to 15.9) | 11.2 (10.8 to 11.6) |

| Age group years | ||

| 18–27 | 11.3 (10.5 to 12.1) | 8.4 (7.7 to 9.1) |

| 28–37 | 8.7 (8.1 to 9.4) | 6.3 (5.7 to 6.8) |

| 38–47 | 11.8 (11.0 to 12.6) | 9.0 (8.3 to 9.7) |

| 48–57 | 21.1 (19.9 to 22.5) | 14.6 (13.5 to 15.8) |

| 58–67 | 32.2 (30.3 to 34.1) | 21.4 (19.7 to 23.1) |

| 68+ | 39.8 (37.5 to 42.2) | 30.5 (28.3 to 32.7) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 12.1 (11.5 to 12.7) | 10.1 (9.6 to 10.6) |

| Female | 18.5 (17.9 to 19.1) | 12.1 (11.7 to 12.7) |

| Migration status | ||

| Non-migrant | 16.8 (16.3 to 17.4) | 12.6 (12.1 to 13.1) |

| Internal migrant | 14.4 (13.7 to 15.2) | 9.7 (9.1 to 10.4) |

| External migrant | 8.1 (7.1 to 9.4) | 5.1 (4.3 to 6.2) |

Effect of migration status on hypertension and diabetes

The effect of migration status on hypertension and diabetes based on analysis of multilevel logistic regression models is presented in table 3. Three models were fitted, the first model only included the individual or household factors, the second model included ward factors and the final model included all factors. Compared with non-migrants, internal migrants and external migrants in the final model had reduced odds of self-reporting hypertension with the OR of 0.86 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.95) and 0.60 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.75), respectively. Being a migrant was also associated with lower risk of diabetes with OR of 0.84 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.94) and 0.53 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.68). While there was a reduction in the variance between the null and full models and ICC vary for both outcomes. There was substantial residual between-ward variance in hypertension and diabetes with median OR of 1.31 and 1.14, respectively as presented in the final model.

Table 3.

The effect of migration status on the most prevalent morbidities

| Characteristics | Null model | Model 1* OR (95% CI) |

Model 2† OR (95% CI) |

Model 3‡ OR (95% CI) |

| Hypertension | ||||

| Migration status | ||||

| Non-migrant | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Internal migrant | 0.85 (0.77 to 0.95) | 0.90 (0.83 to 0.97) | 0.86 (0.78 to 0.95) | |

| External migrant | 0.59 (0.48 to 0.74) | 0.52 (0.44 to 0.61) | 0.60 (0.49 to 0.75) | |

| Random effects | ||||

| Between-ward variance (SE) | 0.25 (0.050) | 0.15 (0.035) | 0.10 (0.023) | 0.08 (0.021) |

| ICC | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| MOR | 1.61 (1.46 to 1.76) | 1.45 (1.33 to 1.57) | 1.35 (1.26 to 1.44) | 1.31 (1.22 to 1.40) |

| Diabetes | ||||

| Migration status | ||||

| Non-migrant | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Internal migrant | 0.84 (0.75 to 0.94) | 0.77 (0.70 to 0.84) | 0.84 (0.75 to 0.94) | |

| External migrant | 0.51 (0.40 to 0.66) | 0.41 (0.37 to 0.50) | 0.53 (0.41 to 0.68) | |

| Random effects | ||||

| Between-ward variance (SE) | 0.05 (0.014) | 0.04 (0.015) | 0.02 (0.007) | 0.02 (0.011) |

| ICC | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| MOR | 1.24 (1.17 to 1.31) | 1.22 (1.13 to 1.30) | 1.13 (1.07 to 1.19) | 1.14 (1.06 to 1.22) |

*The individual/HH level factors.

†The Ward level factors.

‡All factors.

ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; MOR, median OR.

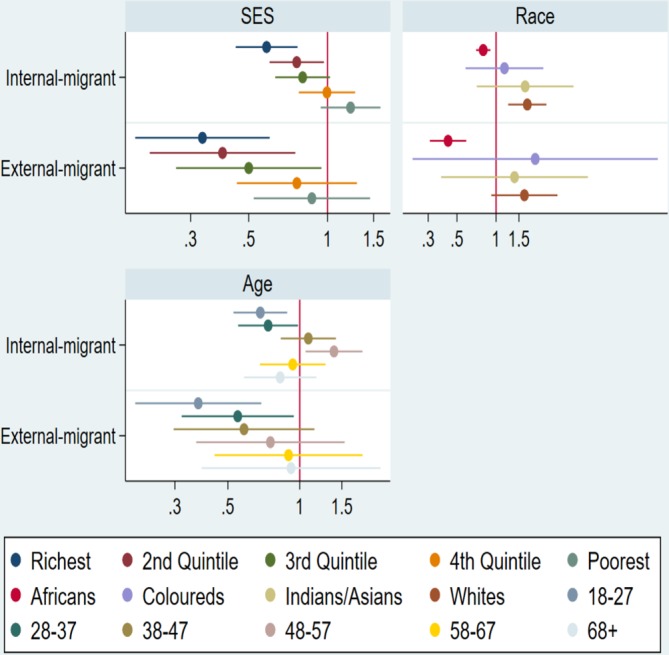

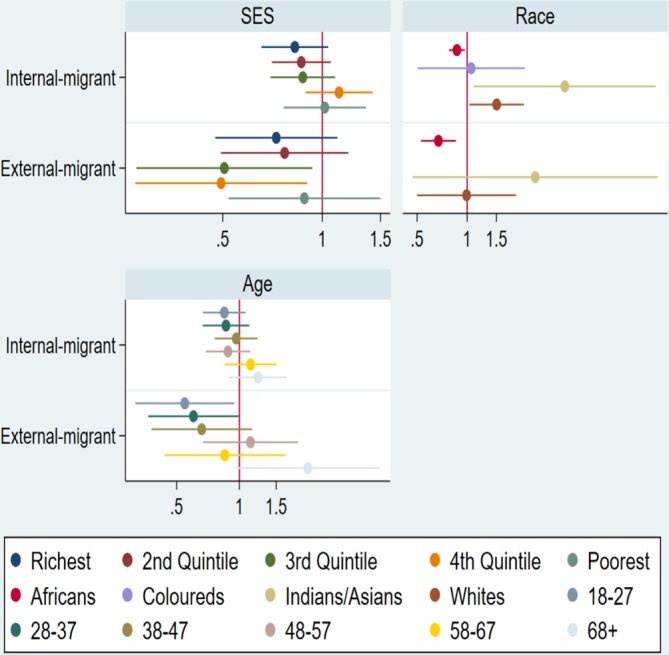

To further assess effect modification of age, race and SES, we ran grade-stratified analysis. The association between migration status and hypertension is significantly modified by race. For Africans, migration status (both internal and external) was associated with lower odds of hypertension, while internal and external Asian migrants have higher odds of hypertension. From the interaction assessment between migration status and race, age group and socioeconomic status, respectively were found to be effect modifiers for hypertension (figure 1) and diabetes (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Association between migration status and hypertension, by SES, race and age group. Figure shows SES-stratified, race-stratified and age group-stratified, fully adjusted ORs in hypertension and associated 95% CIs.

Figure 2.

Association between migration status and diabetes, by SES, race and age group. Figure shows SES-stratified, race-stratified and age group-stratified, fully adjusted ORs in diabetes and associated 95% CIs.

Discussion

The findings from this study provide important information on migration status and the prevalence of morbidities among residents of 508 administrative wards in Gauteng province from a population-based survey. The study indicates that migration status is associated with prevalence of hypertension and diabetes. Internal and external migrants had lower odds of both hypertension and diabetes than people born in Gauteng province. Age, race and SES of the respondents were significant effect modifiers of the association between migration status and morbidities. The major strength of this study is that it assesses prevalence of morbidities and predictors of the most prevalent morbidities from a large population-based survey. The potential of the study was maximised and included the vulnerable population like migrants. The migrants made up 36% of the total respondents.

The most prevalent morbidities in Gauteng province were hypertension and diabetes at 15,5% and 11.2%, respectively. The prevalence of diabetes in South Africa is increasing rapidly.17 18 It was approximately 9% among those aged 30 years and older.18 Based on the population census the prevalence of diabetes was around 9% according to the International Diabetes Federation.19 20 Hypertension was found to be around 14.0% for those aged 25 and older.21 SANHANES reported slightly higher prevalence of diabetes (19.4%) and hypertension (25.7%).10 Hypertension and diabetes were higher among non-migrants. The migrant population is believed to keep increasing in different countries; their heterogeneity becomes apparent with respect to the differences in the prevalence of diseases.7 Prevalence is likely to increase therefore, these findings can be used to inform future policy, planning and funding allocation to assist in controlling as well as managing different conditions.22

Migration status was associated with prevalence of hypertension and diabetes in Gauteng province. Non-communicable diseases are the most common health problem and are the primary cause of death in many countries.23 Research revealed that compared with native-born respondents, migrants reported better health.24 This could be attributed to healthy migration effect, healthier individuals are more likely to migrate. This is consistent with our findings, migrants reported lower prevalence of diabetes and hypertension. Reasons for migration were not included in the questionnaire administered in the primary study; these might have a bearing on the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes among migrants in Gauteng province. Effect of migration status on health differed by age group, race and socioeconomic status. Migrants might find themselves in a worse socioeconomic status, with less access to healthcare services, and experiencing greater linguistic and cultural barriers related to accessing health information, despite the conditions they tend to have better health profiles compared with the natives.25 A number of studies have shown that this health advantage deteriorates over time and with successive generations.24 26 27 There is a lack of studies on morbidity among migrants compared with natives.7 This study clearly demonstrates a need for more research on migration and different morbidities.

Strengths and limitations

This study contributes to the knowledge on migration status and morbidities in Gauteng province, South Africa. Assessment of predicts for the most prevalent morbidities was done from a very large population based representative sample survey. Therefore, the power of the study to detect significant associations was maximised. The respondents were selected by random sampling thus both internal and external validity of the study were improved. The study included the migrant population and little research has been done on the morbidities affecting this subpopulation. A wide variety of sociodemographic factors were employed to assess their association with the two most prevalent morbidities.

The morbidities were self-reported thus prevalence might be underestimated. Self-reported data can be biassed by differential access to healthcare services between groups of different socioeconomic status.28 When self-reported information was compared with medical records or clinical measurements from health examination surveys in Colorado, Netherlands and 12 countries in Europe, self-reported information underestimated the prevalence of hypertension.29 30 It is worth noting that the results from these studies may not be valid for the South African context. This calls for more research on migration status and morbidities, as well as validity studies of self-reported morbidities in the South African setting.

Missing data of some important health-related information, might have resulted in residual confounding because of unmeasured potential confounders.

Conclusion

Migration status is associated with the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes in Gauteng province. From the public health perspective, it is important to evaluate the prevalence of morbidities because the information can inform the development of prevention programme on a community level.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Gauteng City-Region Observatory (GCRO) for providing us with the data to conduct the research.

Footnotes

Contributors: Concept and design of the study: JRN. Acquisition of data: JRN. Analysis and interpretation of data: JRN, MM. Drafting the manuscript: JRN, MM. Revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: JRN, MM and approval of the manuscript to be published: JRN and MM.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: For the primary study ethics approval was obtained from the local ethics committee and the Human Research Ethics Committee of University of the Witwatersrand. All respondents provided informed consent before data collection. The study was granted ethics clearance by the Human Research Ethics Committee of University of the Witwatersrand.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Patra S, Bhise MD. Gender differentials in prevalence of self-reported non-communicable diseases (NCDS) in India: evidence from recent NSSO survey. J Public Health 2016;24:375–85. 10.1007/s10389-016-0732-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Westman J, Martelin T, Härkänen T, et al. . Migration and self-rated health: a comparison between Finns living in Sweden and Finns living in Finland. Scand J Public Health 2008;36:698–705. 10.1177/1403494808089649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kok P, Collinson M. Migration and urbanization in South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: Statistics South Africa, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Turok I. Urbanisation and development in South Africa: economic imperatives, spatial distortions and strategic responses. Pretoria: South Africa Environment Development United Nations Population Fund, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Greif MJ, Dodoo FN-A, Jayaraman A, et al. . Urbanisation, poverty and sexual behaviour: the tale of five African cities. Urban Stud 2011;48:947–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thomas F, Haour-Knipe M, Aggleton P. Mobility, sexuality and AIDS. New York, USA: Routledge, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Diaz E, Poblador-Pou B, Gimeno-Feliu L-A, et al. . Multimorbidity and its patterns according to immigrant origin. A nationwide register-based study in Norway. PLoS One 2015;10:e0145233 10.1371/journal.pone.0145233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization Global status report on non-communicable diseases 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, et al. . Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation 2016;134:441–50. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shisana O, Labadarios D, Rehle T, et al. . South African National health and nutrition examination survey (SANHANES-1). Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gauteng City Region Observatory GCRO Data Brief Key: Findings from Statistics South Africa’s 2011 National Census for Gauteng. South Africa: Gauteng City RegionObservatory, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Statistics South Africa Statistical release: census 2011 South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: Statistics South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gauteng City Region Observatory Quality of life survey technical report. Johannesburg, South Africa: Gauteng City Regional Observatory, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Merlo J, Wagner P, Ghith N, et al. . An original stepwise multilevel logistic regression analysis of discriminatory accuracy: the case of neighbourhoods and health. PLoS One 2016;11:e0153778 10.1371/journal.pone.0153778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Adjaye-Gbewonyo K, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, et al. . Income inequality and cardiovascular disease risk factors in a highly unequal country: a fixed-effects analysis from South Africa. Int J Equity Health 2018;17:1–13. 10.1186/s12939-018-0741-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jann B. Plotting regression coefficients and other estimates. Stata J 2014;14:708–37. 10.1177/1536867X1401400402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pheiffer C, Pillay-van Wyk V, Joubert JD, et al. . The prevalence of type 2 diabetes in South Africa: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021029 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bertram MY, Jaswal AVS, Van Wyk VP, et al. . The non-fatal disease burden caused by type 2 diabetes in South Africa, 2009. Glob Health Action 2013;6:19244 10.3402/gha.v6i0.19244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Diabetes atlas. 7th edn Brussels: IDF, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Statistics South Africa (StatsSA) Mid-year population estimates 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Statistics South Africa Use of health facilities and levels of selected health conditions in South Africa: findings from the general household survey, Pretoria. South Africa: Statistics South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Keel S, Foreman J, Xie J, et al. . The prevalence of self-reported diabetes in the Australian National eye health survey. PLoS One 2017;12:e0169211 10.1371/journal.pone.0169211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Teh JKL, Tey NP, Ng ST. Ethnic and gender differentials in non-communicable diseases and self-rated health in Malaysia. PLoS One 2014;9:e91328 10.1371/journal.pone.0091328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee S, O'Neill AH, Ihara ES, et al. . Change in self-reported health status among immigrants in the United States: associations with measures of acculturation. PLoS One 2013;8:e76494 10.1371/journal.pone.0076494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Frisbie WP, Cho Y, Hummer RA. Immigration and the health of Asian and Pacific Islander adults in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153:372–80. 10.1093/aje/153.4.372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Antecol H, Bedard K. Unhealthy assimilation: why do immigrants converge to American health status levels? Demography 2006;43:337–60. 10.1353/dem.2006.0011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Singh GK, Miller BA. Health, life expectancy, and mortality patterns among immigrant populations in the United States. Can J Public Health 2004;95:I14–I21. 10.1007/BF03403660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vellakkal S, Subramanian SV, Millett C, et al. . Socioeconomic inequalities in non-communicable diseases prevalence in India: disparities between self-reported diagnoses and standardized measures. PLoS One 2013;8:e68219 10.1371/journal.pone.0068219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tolonen H, Koponen P, Mindell JS, et al. . Under-estimation of obesity, hypertension and high cholesterol by self-reported data: comparison of self-reported information and objective measures from health examination surveys. The European Journal of Public Health 2014;24:941–8. 10.1093/eurpub/cku074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Molenaar EA, Ameijden EJCV, Grobbee DE, et al. . Comparison of routine care self-reported and biometrical data on hypertension and diabetes: results of the Utrecht health project. The European Journal of Public Health 2007;17:199–205. 10.1093/eurpub/ckl113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.