Abstract

Objective

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the leading non-AIDS-defining causes of death among HIV-positive (HIV+) individuals. However, the evidence surrounding specific components of CVD risk remains inconclusive. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to synthesise the available evidence and establish the risk of myocardial infarction (MI) among HIV+ compared with uninfected individuals. We also examined MI risk within subgroups of HIV+ individuals according to exposure to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART), ART class/regimen, CD4 cell count and plasma viral load (pVL) levels.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews until 18 July 2018. Furthermore, we scanned recent HIV conference abstracts (CROI, IAS/AIDS) and bibliographies of relevant articles.

Eligibility criteria

Original studies published after December 1999 and reporting comparative data relating to the rate of MI among HIV+ individuals were included.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two reviewers working in duplicate, independently extracted data. Data were pooled using random-effects meta-analysis and reported as relative risk (RR) with 95% CI.

Results

Thirty-two of the 8130 identified records were included in the review. The pooled RR suggests that HIV+ individuals have a greater risk of MI compared with uninfected individuals (RR: 1.73; 95% CI 1.44 to 2.08). Depending on risk stratification, there was moderate variation according to ART uptake (RR, ART-treated=1.80; 95% CI 1.17 to 2.77; ART-untreated HIV+ individuals: 1.25; 95% CI 0.93 to 1.67, both relative to uninfected individuals). We found low CD4 count, high pVL and certain ART characteristics including cumulative ART exposure, any/cumulative use of protease inhibitors as a class, and exposure to specific ART drugs (eg, abacavir) to be importantly associated with a greater MI risk.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that HIV infection, low CD4, high pVL, cumulative ART use in general including certain exposure to specific ART class/regimen are associated with increased risk of MI. The association with cumulative ART may be an index of the duration of HIV infection with its attendant inflammation, and not entirely the effect of cumulative exposure to ART per se.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42014012977.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction, Cardiovascular disease, HIV, Combination antiretroviral therapy (ART), Relative risk, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We used explicit eligibility criteria and a comprehensive search strategy for this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Adjudication of studies for eligibility and the data extraction were performed by two independent reviewers working in duplicate.

This systematic review and meta-analysis analysed several additional drug exposure comparisons and clinical measures (eg, CD4 cell count, plasma viral load) that had not been previously examined in relation to myocardial infarction risk among HIV-positive individuals.

Some of the meta-analyses were based on a small number of studies which is a limitation.

Variability in the quality of the included studies may have influenced the results and thus the conclusions drawn.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the leading non-AIDS causes of death and disability among people living with HIV in the combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) era.1 2 Although HIV-positive (HIV+) individuals are believed to be at higher risk of CVD compared with uninfected individuals,3 4 the results and conclusions from the studies that have examined the nature of the risk of CVD, in particular myocardial infarction (MI) among HIV+ individuals have been conflicting. While some cohort studies have suggested a positive association between ART including specific drug (eg, abacavir) or drug class (eg, protease inhibitors (PIs)) use and MI, or CVD risk,5–9 others have not.10–12 Furthermore, there has been a lack of agreement between observational studies,8 11 13 and randomised controlled trials (RCTs).14 15 Clearly, the evidence regarding the nature of, and extent of the risk of MI and other CVD events among HIV+ individuals is far from uniform.

Five meta-analyses have been conducted in an attempt to synthesise the data on CVD risk among HIV+ individuals.16–20 These have either been limited in scope by assessing only the association between ART use and risk of CVD16; included trials that lacked MI event adjudication17; included trials where CVD events were not among the pre-specified outcomes of interest18; provided incomplete results on MI risk19; or amalgamated all CVD events (eg, MI, stroke) as a single outcome.20 In addition, this latter meta-analysis was fraught with a number of methodological ambiguities.21

Given these limitations, coupled with the publication of several new and updated study reports on the topic, we sought to undertake an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of studies assessing the risk of CVD among persons living with HIV. Considering the scope, diversity and differences in the definition,22–25 aetiology and clinical picture of different CVD events,26 coupled with the strong body of literature related to HIV and MI and the ongoing debate around potential MI risk associated with use of specific ART medications such as abacavir, we have elected to focus primarily on MI as the outcome of interest for this meta-analysis, as it is the most widely researched CVD outcome among HIV+ individuals. The objective of our study was to estimate the risk of MI among HIV+ individuals relative to uninfected individuals. Additionally, we examined MI risk within subgroups of HIV+ individuals according to exposure to ART, ART class, specific ART regimen, CD4 cell count and plasma viral load (pVL) levels.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

The systematic review and meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the PRISMA statement.27 A protocol describing the inclusion criteria and analysis methods for this systematic review was specified in advance, registered and published at the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO).28

The search strategy (see online supplementary appendix table 1) was developed in consultation with a medical librarian at Simon Fraser University, BC, Canada. The search terms were based on a combination of indexed and free-text terms reflecting clinical outcomes of interest to the review, and included the following keywords: ‘HIV, human immunodeficiency virus, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, HIV/AIDS, stroke, myocardial infarction, cardiac death, cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, cardiovascular disease and CVD’. These terms were used in combination to execute the searches, which were up to 18 July 2018. Using the Ovid platform, we searched the following electronic databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. In addition, we screened the abstracts of the International AIDS Society conferences (AIDS 2012, 2014, 2016; IAS 2013) and the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2014, 2015 and 2016). We also searched the reference lists of relevant articles and previous systematic reviews for additional eligible publications. Finally, we set up automatic PubMed literature alerts to identify any new relevant article published while the manuscript was under development.

bmjopen-2018-025874supp001.pdf (8.4MB, pdf)

We included original research published in English where at least one of the participant groups were individuals living with HIV, and presenting comparative data on the incidence of MI. We included studies in which results were stratified according to HIV status; CD4 cell count; pVL levels; ART use; or exposure to particular ART class or regimen. Studies involving non-human populations; children; as well as those reporting only unadjusted estimates, intermediate, surrogate or CVD biomarker outcomes were excluded (for additional information, see Study selection section in the online supplementary appendix, p1). To reflect the current context of HIV treatment and disease management, we selected studies published from the year 2000 onwards. Although both observational studies and RCTs were eligible for inclusion, we did not include RCTs that were not designed to assess CVD events as a prespecified outcome to avoid bias.

Working independently and in duplicate, two reviewers (OE and GB) scanned the titles and abstracts of the retrieved records for eligibility. The full-text articles of potentially eligible studies were obtained and reviewed in greater details. Disagreements in study selection were resolved through discussion, and where necessary, a third investigator (RSH) was invited to facilitate consensus.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The same two reviewers (OE and GB) conducted data extraction independently using a predesigned data abstraction sheet. We extracted data on study descriptors, sample characteristics, outcome assessment, risk estimate for relevant comparisons and study quality features. Where necessary, we sought clarification directly from study authors through email contact. In cases where data from the same study described the same event risk in multiple publications, we extracted data from the most comprehensive report while supplementing missing study-level information from the others. In keeping with characterisations in the included studies, exposure to ART was categorised as any (or prior/some compared with none), recent (or within the preceding 6 months compared with not recent) and cumulative ART exposure per year of exposure.

The quality of the included studies was assessed according to risk of bias criteria based on the type of study design. As only observational studies were eventually included in the meta-analysis since eligible RCTs were not identified, we made this assessment by evaluating study design features of the eligible observational studies. Following guidelines in the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for assessing the quality of observational studies in meta-analyses29 and with slight modification of the scoring system to simplify reporting, the risk of bias assessment was performed based on the adequacy of three key domains of the study design features namely: the group/participant selection; comparability of groups; and the exposure and outcome assessments in the individual studies. For each of these key features, we assigned a ‘+’ (plus) sign when this was clearly and adequately described in the study, and a ‘–’ (minus) sign when it was not clearly described or was missing. A detailed description of the results of the quality assessment is available in the online supplementary appendix.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in this study. We used data from published materials only.

Data analysis

We calculated the kappa statistic as a measure of the inter-reviewer agreement for the selection of articles meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria. For interpretation, we defined a priori the interval for the kappa result using Landis and Koch criteria.30 For effect measure, we assumed the incidence rate ratio (IRR), OR and HR with corresponding sampling variance to be numerical approximate measures of the relative risk (RR) for a given association of interest with the underlying assumption of a generally low event risk (<20%),31–36 and thus combined them as previously described.19 37–40 We tested this assumption in sensitivity analyses by performing separate meta-analyses where studies presenting results reported using a similar effect measure type were pooled. Given the expected variability among eligible studies, we pooled studies using the DerSimonian-Laird random-effects model.41 To minimise bias in our pooled estimates, adjusted risk estimates were not combined with unadjusted estimates. The final set of studies that adjusted for confounders did not consistently adjust for the same set of confounders but were deemed to have sufficient internal validity to permit pooling. For the analysis that quantified the overall RR of MI associated with HIV infection, we performed a sensitivity analysis where we examined the appropriateness of the comparison group by repeating the meta-analysis and including two additional studies that involved a general population comparison group,42 43 as opposed to an HIV-uninfected comparison group. Given the limitations of the I 2 statistics with observational studies and Cochran Q test when the number of studies is small,44 45 we assessed heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plots for overlap in the confidence intervals of the individual studies, although the I 2 as a measure of the degree of heterogeneity across studies is reported in the forest plots for completeness. We were unable to perform meta-regression analyses to assess the potential effect of study-level covariates on the pooled estimate due to insufficient studies (<10),46 in each of the meta-analyses. Although we assessed publication bias by visually inspecting and testing for funnel plot asymmetry,47 its interpretation was limited by a lack of sufficient number of studies per meta-analysis.48 49 A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The meta-analysis was conducted using the metafor package of the R statistical programme V.3.3.1.50

Results

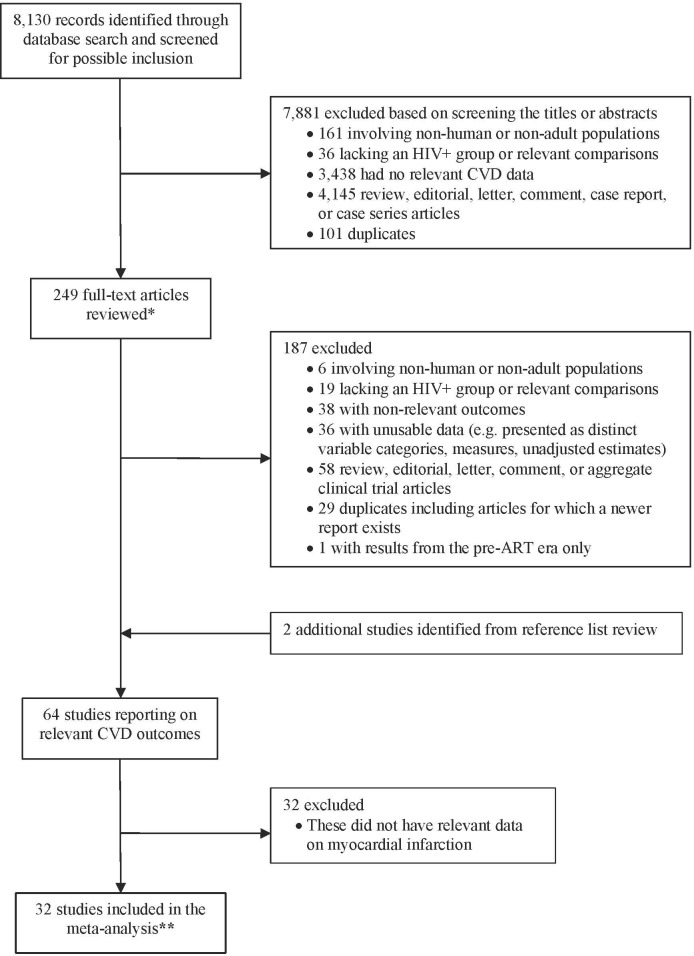

Of 8130 records identified through the database search, the final screening process yielded 64 potentially eligible publications on CVD outcomes, 32 of which had relevant data on MI and were included in this meta-analysis (figure 1). Overall, there was near perfect agreement between reviewers on the inclusion of studies (kappa statistic=0.94; 95% CI 0.89 to 0.99). The included studies, most of which were conducted in the USA and Europe, were published between 2000 and 2017 and involved ~383,471 HIV+ and > 798, 424 HIV- individuals (online supplementary appendix table 2: characteristics of the included studies; note: the number of individuals in cohorts with multiple publications was accessed only from one of the publications). The mean duration of follow-up varied across studies from ~1 to 20 years. All 32 publications were non-randomised studies and included two nested case–control studies,11 51 one cohort/nested case–control study,52 and 29 cohort studies; 15 of which were prospective studies, by design.3 7 8 13 42 53–62 Twenty-nine studies were published as full-text journal articles, while three were available as conference abstracts.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection. *, includes several conference abstract records captured through the database search; **, includes two studies involving a ‘general population’ comparison group. ART, combination antiretroviral therapy. CVD, cardiovascular disease.

In general, the reporting and quality of the methodological aspects of the included studies were variable. Three studies did not provide sufficient information necessary to assess the study quality, as they were reported and available as conference abstract/poster.55 57 63 The eligibility criteria were clearly defined in the majority of studies (94%), description of study participants/ groups was sufficient (100%); however, the exposure or outcome was not adequately ascertained in 15 studies (47%)8 12 24 52 54 56 60 63–70; 1 (7%) of which was published as an abstract63 (see online supplementary appendix table 3: risk of bias in the included studies).

Meta-analysis of the risk of MI

Below, we summarise the results of the meta-analyses of MI risk according to the various risk stratifications assessed. To avoid duplication of reporting, only statistically important RR are stated in text; although both statistically significant and insignificant results are presented in the figures (forest plots).

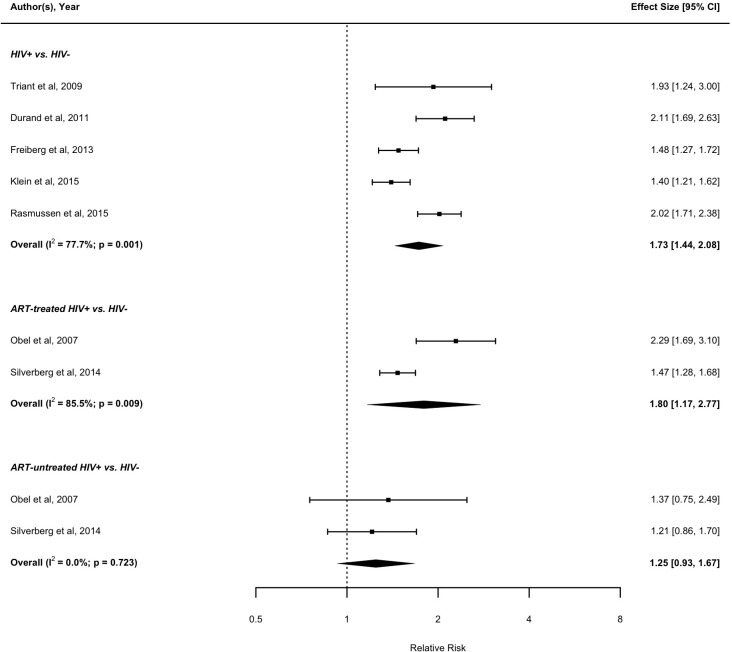

Risk of MI associated with HIV infection

The pooled RR from the five studies that met eligibility for this assessment of MI risk according to HIV serostatus suggests that HIV+ individuals are more likely to have an MI event compared with uninfected individuals (RR: 1.73; 95% CI 1.44 to 2.08).3 52 56 69 71 In sensitivity analysis (online supplementary appendix figure S1) where we repeated the meta-analysis and included two additional studies that involved a general population comparison group,42 43 the overall pooled RR was 1.60; 95% CI 1.38 to 1.85. Figure 2 shows the forest plots for the association between HIV infection and MI risk. Two studies assessed the risk of MI by HIV serostatus according to whether ART treatment was received.60 72 Compared with uninfected individuals, the pooled RR of MI was significantly higher among HIV+ individuals on ART (RR: 1.80; 95% CI 1.17 to 2.77), but not the ART-untreated HIV+ individuals (RR: 1.25; 95% CI 0.93 to 1.67).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of the risk of MI associated with HIV infection. ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Risk of MI associated with CD4 cell count and pVL levels

The pooled RR based on combining data from three studies suggests that low CD4 cell count (<200 cells/mm3) is associated with higher MI risk compared with CD4 ≥200 (RR: 1.60; 95% CI 1.25 to 2.04).3 57 68 Conversely, a high pVL (≥100 000 copies/mL) was found to be associated with increased MI risk compared with pVL <100 000 (RR: 1.45; 95% CI 1.11 to 1.90), based on the pooled results from two studies (figure 3).54 68

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of the risk of MI associated with CD4 cell count and plasma viral load levels.

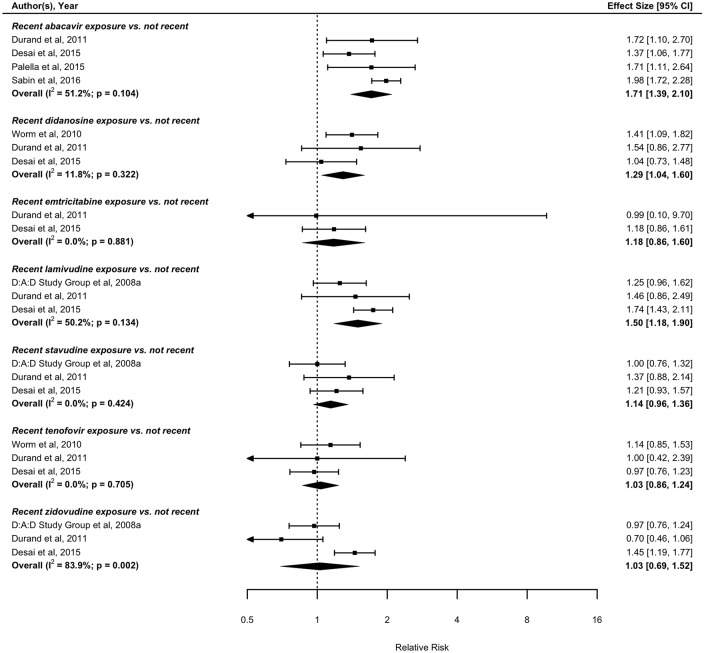

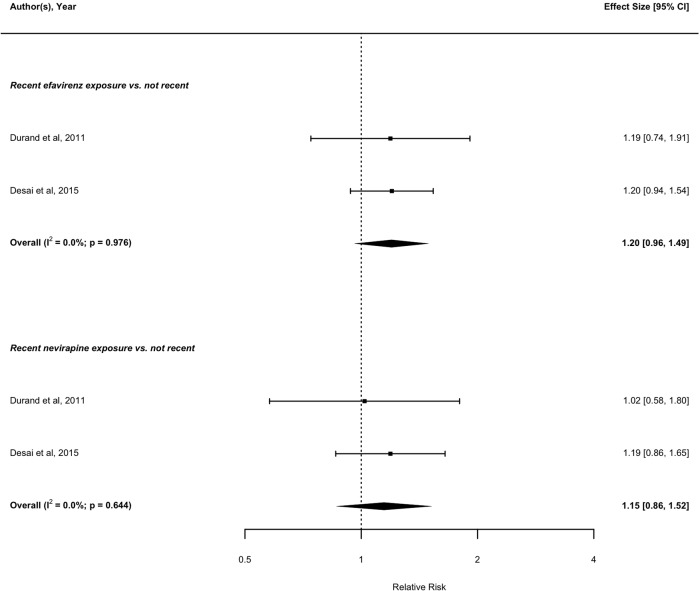

Risk of MI associated with recent ART exposure

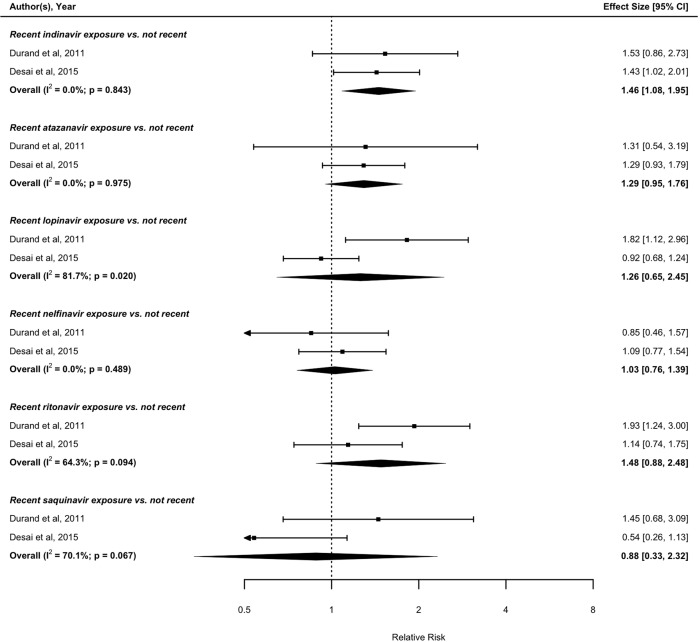

With regards to recent treatment exposure (i.e., within the preceding 6 months), four eligible studies with data on nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) exposure assessed the risk of MI associated with recent compared with not recent abacavir exposure.52 53 55 67 The pooled result from these four studies suggests that recent abacavir exposure is associated with increased risk of MI compared with not recent exposure (RR: 1.71; 95% CI 1.39 to 2.10). Similarly, recent didanosine (RR: 1.29; 95% CI 1.04 to 1.60),52 58 67 and lamivudine (RR: 1.50; 95% CI 1.18 to 1.90),13 52 67 exposure is associated with increased risk of MI compared with not recent exposures. In contrast, there was no detectable association between recent tenofovir,52 58 67 zidovudine,13 52 67 stavudine,13 52 67 emtricitabine52 67 and MI risk compared with not recent exposure (figure 4). Based on pooling data from two studies with data on non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) exposure,52 67 no association was found between recent efavirenz or nevirapine exposure and MI risk compared with not recent exposure (figure 5). Based on pooled results from the studies assessing the MI risk of individual PIs, recent indinavir was associated with increased MI risk compared with not recent exposure (RR: 1.46; 95% CI 1.08 to 1.95).52 67 Recent exposure to other PI regimens including atazanavir,52 67 lopinavir,52 67 ritonavir,52 67 nelfinavir52 67 and saquinavir,52 67 were not found to be significantly associated with MI risk compared with not recent exposure (figure 6).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of the risk of MI associated with recent exposure to drugs of the NRTI class. NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of the risk of MI associated with recent exposure to drugs of the NNRTI class. NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of the risk of MI associated with recent exposure to drugs of the protease inhibitor class.

Risk of MI associated with any ART exposure

In terms of any treatment exposure, our meta-analysis did not find an association between exposure to ART and risk of MI compared with no exposure (online supplementary appendix figure A1).62 72 Based on the pooled results from six studies with data on NRTI exposure,8 11 13 52 63 68 individuals receiving abacavir were more likely to have an MI compared with those who did not (RR: 1.58; 95% CI 1.25 to 2.00). We found a similar association between didanosine exposure and MI risk (RR: 1.48; 95% CI 1.16 to 1.90).13 52 68 No detectable association was found between exposure to tenofovir,52 68 zidovudine,13 52 stavudine,13 52 68 emtricitabine52 68 and MI risk, based on our pooled results (online supplementary appendix figure A2). The meta-analysis of studies with data on NNRTI exposure did not find any evidence of an association between either efavirenz52 65 or nevirapine exposure,52 68 and MI risk compared with no exposure (online supplementary appendix figure A3). The pooled RR from four studies demonstrates that PI exposure is associated with an increase in the risk of MI events compared with no exposure to PI (RR: 1.49; 95% CI 1.16 to 1.91).3 6 61 63 When the analysis was limited to two studies comparing recent PI exposure to no exposure,3 63 similar results were found (RR: 1.40; 95% CI 1.16 to 1.69 (data not shown)). For the individual PIs, there was no association between either atazanavir,52 64 66 68 saquinavir,52 68 or nelfinavir exposure,52 68 and MI risk, compared with no exposure (online supplementary appendix figure A4).

Risk of MI associated with cumulative ART exposure

With regards to cumulative treatment exposure, three eligible studies provided relevant data regarding the risk of MI and cumulative ART exposure.12 68 70 We found that cumulative exposure to ART was associated with an increase in the risk of MI per year of exposure (RR: 1.12; 95% CI 1.06 to 1.18) (online supplementary appendix figure A5). For exposure to NRTI regimens, we estimated an increase in MI risk per year of exposure to abacavir (RR: 1.08; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.15) based on pooling data from two eligible studies.12 58 Similar to abacavir, cumulative zidovudine exposure was associated with an increase in MI risk per year of exposure (RR: 1.05; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.10).11 13 We found no association between cumulative exposure to either didanosine,11 13 tenofovir,11 58 lamivudine11 13 or stavudine,11 13 and MI risk per year of exposure (online supplementary appendix figure A6). The overall RR suggests that cumulative NNRTI exposure as a class (RR: 1.02; 95% CI 0.97 to 1.08),59 70 72 or as individual drugs (nevirapine and efavirenz),11 58 is not significantly associated with increased risk of MI events per year of exposure (online supplementary appendix figure A7). Three eligible studies reported data assessing the risk of MI associated with cumulative exposure to PIs as a class.59 70 72 There was an increase in risk of MI per year of exposure to PIs (RR: 1.14; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.26). For individual drugs, cumulative exposure to lopinavir with ritonavir (RR: 1.19; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.39),11 58 but not nelfinavir,11 58 was found to be associated with increase in the risk of MI events per year of exposure (online supplementary appendix figure A8).

Sensitivity analyses

The strength and direction of the overall RR from the various meta-analyses remained robust in sensitivity analyses where estimates reported using similar effect measures were pooled. For example, HIV+ individuals continued to have higher risk of MI events compared with uninfected individuals when pooled using either IRRs (overall effect: 1.68; 95% CI 1.17 to 2.40) or HRs (overall effect: 1.75; 95% CI 1.24 to 2.48) effect measures, compared with a RR of 1.73; 95% CI 1.44 to 2.08, obtained from pooling results reported using multiple relative effect measures (online supplementary appendix figure S2).

Discussion

This updated systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the risk of MI among people living with HIV reflects contemporary ART era and found the following: (1) HIV+ individuals have a greater risk of MI compared with uninfected individuals; and among HIV+ individuals, (2) low CD4 cell count (<200 cells/mm3) and high pVL (>100 000 copies/mL) are associated with increases in MI risk compared with higher CD4 or lower pVL, respectively; (3) cumulative ART exposure is associated with a greater risk of MI per year of exposure; (4) among NRTIs, any type of exposure to abacavir; cumulative exposure to zidovudine; and recent exposure to either didanosine or lamivudine are significantly associated with higher risk of MI; (5) compared with no exposure, any or cumulative exposure to PIs as a class; cumulative exposure to lopinavir with ritonavir; and recent indinavir exposure were associated with higher risk of MI; (6) NNRTIs assessed either as a class or individually were not associated with increased MI risk.

Previous meta-analyses comparing CVD risk among HIV+ and uninfected individuals reported estimates for the association between HIV-seropositivity and MI (RR: 1.79; 95% CI 1.54 to 2.08)19 or CVD (RR: 1.61; 95% CI 1.43 to 1.81)20; risk that are similar to our findings for MI (RR: 1.73; 95% CI 1.44 to 2.08). As has been previously hypothesised,3 23 73–75 the probable mechanistic pathway through which HIV infection can induce MI may include a cascade of events involving chronic inflammation, immunodeficiency/CD4 cell depletion, endothelial dysfunction, increased thrombosis and accelerated atherosclerosis that typically accompany both controlled and uncontrolled HIV disease. Relative to uninfected individuals and similar to what we found (RR: 1.80; 95% CI 1.17 to 2.77), one of the previous meta-analysis also reported a higher risk of CVD among ART-treated individuals (RR: 2.00; 95% CI 1.70 to 2.37).20 We suspect that the higher MI risk among ART-treated HIV+ individuals may not necessarily be attributable to ART alone but rather to the combined effect from a host of factors including HIV itself, ART, and other comorbid risk factors which have been individually shown to contribute to MI risk.3 5 76 77 Furthermore, the risk associated with cumulative ART exposure may be an index of the duration of HIV infection with its attendant inflammation, and not entirely the effect of cumulative exposure to ART per se.

Specific to abacavir and MI risk, our findings were similar to reports from a previous meta-analysis of observational studies of MI,16 but different from those of the meta-analysis of RCTs,17 18 or reports from aggregate clinical trial studies,14 15 that suggested no risk associated with abacavir exposure. Although observational studies and RCT results regarding MI and CVD risk due to abacavir exposure among people living with HIV are largely at odds, the Simplification with Tenofovir-Emtricitabine or Abacavir-Lamivudine trial is the first RCT to support observational studies finding of increased risk of CVD with exposure to abacavir.78 Based on the available evidence to date, the controversy regarding the potential association between abacavir use and risk of MI will likely continue to plague the field of HIV therapeutics until such a time when definitive evidence describing the underlying mechanism can be produced.79 80 A sufficiently powered RCT with long follow-up and including real-world populations reflective of those typically seen clinically may be needed to fully resolve this clinical controversy.

Unlike our results where a class-level effect was evident for PIs, pooled aggregate clinical trial data after 1 year of treatment with four different PI-based regimens did not find evidence of an increased risk associated with PI compared with NRTI regimen (RR: 1.69; 95% CI 0.54 to 7.48).81 When we pooled data of individual PIs separately, we did not observe the same ‘class-level’ results. In our analysis, different PI regimens carried different risks. For example, while recent indinavir and cumulative lopinavir-ritonavir exposure were associated with increased MI risk, nelfinavir or atazanavir did not appear to contribute to MI risk irrespective of the type of exposure data that were pooled.

In terms of the scope and design, our study differs from previous meta-analyses on this topic in several ways. First, we used an expanded search strategy that included more data sources and search of conference archives compared with prior meta-analyses.16–20 Second, as the association of HIV and ART may affect the risk of MI and other CVD events differently, we did not assess the risk of CVD in general, as was done in previous meta-analysis.20 Third, we have used more recent risk estimates from studies with longer follow-up such as the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study. Fourth, we have included studies published between 2000 and 2017 with reported data from the post-ART era. The historical nature of some of the studies included in previous meta-analysis may have limited their relevance in contemporary times. Finally, this systematic review analysed several additional drug exposure comparisons and clinical measures (eg, CD4 cell count, pVL) in relation to MI risk that had not been previously examined.

There are several important considerations that should be taken into account in the interpretation of the results of this study. Accurate characterisation of the risk of MI and CVD outcomes in general may be confounded by a number of factors that may have affected our conclusions. The first concern has to do with the differences in the risk factors, drug exposure, HIV-related variables, or population considered in the included studies. Indeed, no two studies of HIV+ individuals from different underlying populations can have participants with the same exact demographic, clinical and drug exposure profile—all of which play a role in overall health outcomes. Given that studies typically included in a global meta-analysis such as ours do not come from the same underlying source population, we acknowledge that there may be some differences in the population distribution in the included studies (eg, in the distribution by age, sex, disease stage, medication profile/history) that we were unable to account for. A second concern relates to the variability in the quality and design features of the included studies, which may have influenced the results of the meta-analyses and thus the conclusions drawn. Although the majority of included studies were cohort-based (90%), almost one half (47%) were retrospective in nature and did not adequately report how the exposure or outcome was ascertained including whether an adjudication protocol was applied in the ascertainment of MIs. It has been shown that the application of an adjudication protocol in the study of MI and other CVD events is important to ensuring accurate identification of events as relying only on administrative diagnostic codes could result in misclassification.82 While some studies retrospectively assessed MI and relied on International Classification of Diseases codes alone—something that is quite common in large epidemiological studies of MI,76 others followed participants over time and prospectively assessed and validated the MI events. It is unclear how differences in MI definition across studies may have affected our results although in two studies from the same underlying population (Veterans Ageing Cohort Study) that used similar but not the same definitions for MI,3 83 the RR differed slightly: 1.48 (95% CI 1.27 to 1.72)3 versus 1.76 (95% CI 1.49 to 2.07).83 Regarding studies that quantified the risk of MI associated with HIV infection, the available evidence based on the included studies all point in the same direction suggesting an increase in MI risk. However, we noted some variability in the design and quality of the studies, something that may have contributed in part to the observed heterogeneity. For example, three studies did not provide sufficient information on the exposure or outcome ascertainment in the studies.52 56 69 Furthermore, the appropriateness of the HIV-uninfected group used for comparison purposes is critical in the assessment of MI risk associated with HIV infection; an issue that has been extensively reviewed elsewhere.84 While some studies made this comparison using an HIV-uninfected group, other studies used the general population group for comparison. In sensitivity analysis, the overall RR of MI associated with HIV infection was reduced when we included in the meta-analysis two additional studies involving a ‘general population’ comparison group,42 43 therefore highlighting the importance of using an appropriate control group.

Another potential concern relates to differences in the extent to which key confounding factors were adjusted for in the individual analysis contributing to the meta-analysis. For example, some studies lacked data on smoking—an important risk factor for CVD in general, and therefore did not account for it in the analyses.52 60 65 In this regard, we noted that the included studies did not consistently control for the exact same set of confounders which may have undermined their internal validity and explained some of the differences in the effect measures from the individual studies. There is also the potential for residual, unmeasured confounding given the observational nature of the included studies. Therefore, heterogeneity arising from differences in study design or other quality features may have influenced the results and thus the overall conclusions drawn. Although we observed heterogeneity across results of studies included in some of the meta-analyses, this is a common limitation in meta-analysis especially those involving observational studies.44 Our a priori choice of employing the random-effects modelling strategy was driven in part by this expected variability among studies.85 Furthermore, our study combined results presented using several different relative effect measures with the assumption that these represent approximately the same numerical value.31–36 In sensitivity analyses, we did not find any evidence of bias in our pooled estimates, as these did not differ importantly from the pooled estimates we obtained when we combined studies reporting results using the same effect measure. Moreover, we reached comparable conclusions with previous meta-analyses that combined,19 or did not combine HR estimates with OR, and RR.16

Also, some of the meta-analyses in our study such as those examining the risk of MI in relation to CD4, pVL or use of specific ARV regimens were based on a small number of studies (only 2–3 studies), which is a serious limitation. It is important to also consider this point in the interpretation of these specific findings. We acknowledge that the results from such meta-analyses could have been strengthened with the inclusion of additional eligible studies. Nevertheless, in the absence of sufficient number of studies examining these relationships, our results could be viewed as the best available evidence summarising the risk of MI associated with CD4, pVL or use of specific ARV regimens among people living with HIV.

Given the foregoing discussion in relation to the design and quality aspects of the included studies as well as issues of sufficiency of available studies examining several potential associations with MI risk, additional rigorously conducted studies with extensive confounding factor stratification/adjustment are needed to further confirm our findings. Furthermore, considering that the majority of the studies on this topic are carried out in North America and Europe, our study highlights the need for more research to be conducted in resource limited settings where most people living with HIV reside.

Conclusions

In summary, this updated systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that HIV infection, ART use in general including exposure to specific ART class (eg, PIs) and regimen (eg, abacavir) are associated with increased risk of MI. These findings should be interpreted in light of the key considerations that we have highlighted in this review. We found the totality of the evidence for an association between HIV infection and MI to be compelling. With respect to ART and MI risk, HIV treatment strategies should certainly consider cardiovascular risk factors including exposure to particular ART drugs as part of patient-tailored care. However, given what we currently know about ART’s effectiveness, the benefits of ART for the treatment of HIV infection in terms of viral suppression and immune reconstitution should be balanced against its potential unfavourable impact on MI. Specific to abacavir and MI risk where there is conflicting evidence between observational studies and RCTs, additional rigorously conducted studies in real-world populations are needed to definitively substantiate our findings and strengthen the existing evidence on this topic. Given the multiple potential contributory and mechanistic pathways to developing MI among HIV+ individuals and the complexity/feasibility of designing a large enough study to completely tease apart the potential contributions of each of the factors believed to increase the risk of MI, managing known modifiable risk factors for CVD outcomes (eg, smoking) through behavioural/lifestyle interventions, would be an excellent first step in reducing the incidence and risk of MI among people living with HIV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Simon Fraser University library staff for the assistance provided during the search strategy development.

Footnotes

Contributors: OE, MWH, SAL, JSGM and RSH conceived and designed the study. OE, GB and RSH acquired the data. OE performed the statistical analysis with input from CHG, CF-V and EJM. OE, GB, CHG, MWH, SAL, MB, SG, CF-V, AA, EJM, JSGM and RSH contributed to the interpretation of the data. OE drafted the manuscript. OE, GB, CHG, MWH, SAL, MB, SG, CF-V, AA, EJM, JSGM and RSH reviewed the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data and materials used in this research are available in Medline/PubMed. References have been provided.

References

- 1. Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration Causes of death in HIV-1-infected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy, 1996-2006: collaborative analysis of 13 HIV cohort studies. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:1387–96. 10.1086/652283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. The Lancet 2014;384:241–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60604-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Freiberg MS, Chang C-CH, Kuller LH, et al. Hiv infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:614–22. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marcus JL, Leyden WA, Chao CR, et al. Hiv infection and incidence of ischemic stroke. AIDS 2014;28:1911–9. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Friis-Møller N, Sabin CA, Weber R, et al. Combination antiretroviral therapy and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1993–2003. 10.1056/NEJMoa030218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mary-Krause M, Cotte L, Simon A, et al. Increased risk of myocardial infarction with duration of protease inhibitor therapy in HIV-infected men. AIDS 2003;17:2479–86. 10.1097/00002030-200311210-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Friis-Møller N, Reiss P, Sabin CA, et al. Class of antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1723–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa062744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Obel N, Farkas DK, Kronborg G, et al. Abacavir and risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy: a population-based nationwide cohort study. HIV Med 2010;11:130–6. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00751.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Strategies for Management of Anti-Retroviral Therapy/INSIGHT, DAD Study Groups . Use of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients. AIDS 2008;22:F17–F24. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830fe35e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bozzette SA, Ake CF, Tam HK, et al. Long-Term survival and serious cardiovascular events in HIV-infected patients treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;47:338–41. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815e7251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lang S, Mary-Krause M, Cotte L, et al. Impact of individual antiretroviral drugs on the risk of myocardial infarction in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: a case-control study nested within the French Hospital database on HIV ANRS cohort CO4. Arch Intern Med 2010a;170:1228–38. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bedimo RJ, Westfall AO, Drechsler H, et al. Abacavir use and risk of acute myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular events in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53:84–91. 10.1093/cid/cir269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sabin CA, Worm SW, Weber R, et al. Use of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients enrolled in the D:A:D study: a multi-cohort collaboration. Lancet 2008a;371:1417–26. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60423-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brothers CH, Hernandez JE, Cutrell AG, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction and abacavir therapy: no increased risk across 52 GlaxoSmithKline-sponsored clinical trials in adult subjects. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;51:20–8. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819ff0e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ribaudo HJ, Benson CA, Zheng Y, et al. No risk of myocardial infarction associated with initial antiretroviral treatment containing abacavir: short and long-term results from ACTG A5001/ALLRT. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:929–40. 10.1093/cid/ciq244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bavinger C, Bendavid E, Niehaus K, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease from antiretroviral therapy for HIV: a systematic review. PLoS One 2013;8:e59551 10.1371/journal.pone.0059551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ding X, Andraca-Carrera E, Cooper C, et al. No association of abacavir use with myocardial infarction: findings of an FDA meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;61:441–7. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826f993c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cruciani M, Zanichelli V, Serpelloni G, et al. Abacavir use and cardiovascular disease events: a meta-analysis of published and unpublished data. AIDS 2011;25:1993–2004. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328349c6ee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shah ASV, Stelzle D, Lee KK, et al. Global burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in people living with the human immunodeficiency virus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Islam FM, Wu J, Jansson J, et al. Relative risk of cardiovascular disease among people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HIV Med 2012;13:n/a–68. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2012.00996.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Neaton JD. HIV and cardiovascular disease: comment on Islam et al. HIV Med 2013;14:517–8. 10.1111/hiv.12043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iloeje UH, Yuan Y, L'Italien G, et al. Protease inhibitor exposure and increased risk of cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected patients. HIV Med 2005;6:37–44. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00265.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lichtenstein KA, Armon C, Buchacz K, et al. Low CD4 + T Cell Count Is a Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Disease Events in the HIV Outpatient Study. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:435–47. 10.1086/655144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Choi AI, Vittinghoff E, Deeks SG, et al. Cardiovascular risks associated with abacavir and tenofovir exposure in HIV-infected persons. AIDS 2011;25:1289–98. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328347fa16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klein MB, Xiao Y, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Re-assessing the cardiovascular risk of abacavir in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS) using a flexible marginal structural model [ICPE Abstract 396]. In: Abstracts of the 29th International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22:193–4. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Widimsky P, Coram R, Abou-Chebl A. Reperfusion therapy of acute ischaemic stroke and acute myocardial infarction: similarities and differences. Eur Heart J 2014;35:147–55. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eyawo O, Brockman G, Lear S, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease events among HIV-positive individuals compared to HIV-negative individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis (number: CRD42014012977). Inte Prospect Regist Syst Rev 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses, 2018. Available: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp [Accessed 17 January 2019].

- 30. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Symons MJ, Moore DT. Hazard rate ratio and prospective epidemiological studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:893–9. 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00443-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sedgwick P. Hazards and hazard ratios. BMJ 2012;345:e5980 10.1136/bmj.e5980 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hernán MA. The hazards of hazard ratios. Epidemiology 2010;21:13–15. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c1ea43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Chapter 13: models for survival data : McCullagh P, Nelder JA, Generalized linear models. 2nd ed London, New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 1989: 419–31. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Laird N, Olivier D. Covariance analysis of censored survival data using log-linear analysis techniques. J Am Stat Assoc 1981;76:231–40. 10.1080/01621459.1981.10477634 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Symons MJ, Taulbee JD. Practical considerations for approximating relative risk by the standardized mortality ratio. J Occup Environ Med 1981;23:413–6. 10.1097/00043764-198106000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fernández MDM, Saulyte J, Inskip HM, et al. Premenstrual syndrome and alcohol consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019490 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Byrne AL, Marais BJ, Mitnick CD, et al. Tuberculosis and chronic respiratory disease: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis 2015;32:138–46. 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Beckett MW, Ardern CI, Rotondi MA. A meta-analysis of prospective studies on the role of physical activity and the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease in older adults. BMC Geriatr 2015;15:9 10.1186/s12877-015-0007-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bateson D, Butcher BE, Donovan C, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in women taking the combined oral contraceptive: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust Fam Physician 2016;45:59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-Analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Drozd DR, Kitahata MM, Althoff KN, et al. Increased risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected individuals in North America compared with the general population. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;75:568–76. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lang S, Mary-Krause M, Cotte L, et al. Increased risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients in France, relative to the general population. AIDS 2010b;24:1228–30. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328339192f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mills EJ, Jansen JP, Kanters S. Heterogeneity in meta-analysis of FDG-PET studies to diagnose lung cancer. JAMA 2015;313 10.1001/jama.2014.16482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Higgins JPT, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available: http://www.cochrane.org/handbook [Accessed 27 July 2017].

- 47. Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ioannidis JPA, Trikalinos TA. The appropriateness of asymmetry tests for publication bias in meta-analyses: a large survey. Can Med Assoc J 2007;176:1091–6. 10.1503/cmaj.060410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lau J, Ioannidis JPA, Terrin N, et al. The case of the misleading funnel plot. BMJ 2006;333:597–600. 10.1136/bmj.333.7568.597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw 2010;36:1–48. 10.18637/jss.v036.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lang S, Mary-Krause M, Simon A, et al. Hiv replication and immune status are independent predictors of the risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected individuals. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55:600–7. 10.1093/cid/cis489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Durand M, Sheehy O, Baril J-G, et al. Association between HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy, and risk of acute myocardial infarction: a cohort and nested case-control study using Québec's public health insurance database. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011;57:245–53. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821d33a5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sabin CA, Reiss P, Ryom L, et al. Is there continued evidence for an association between abacavir usage and myocardial infarction risk in individuals with HIV? a cohort collaboration. BMC Med 2016;14:61 10.1186/s12916-016-0588-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Salinas JL, Rentsch C, Marconi VC, et al. Baseline, Time-Updated, and cumulative HIV care metrics for predicting acute myocardial infarction and all-cause mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:1423–30. 10.1093/cid/ciw564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Palella FJ, Althoff KN, Moore R, et al. Abacavir use and risk for myocardial infarction in the NA-ACCORD [CROI Abstract 749LB]. In Special Issue: Abstracts From the 2015 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Top Antivir Med 2015;23:335–6. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rasmussen LD, May MT, Kronborg G, et al. Time trends for risk of severe age-related diseases in individuals with and without HIV infection in Denmark: a nationwide population-based cohort study. The Lancet HIV 2015;2:e288–98. 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00077-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Drozd DR, Nance RM, Delaney JAC, et al. Lower CD4 count and higher viral load are associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction [CROI abstract 739]. In Special Issue: Abstracts From the 2014 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Top Antivir Med 2014;22:377. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Worm SW, Sabin C, Weber R, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with HIV infection exposed to specific individual antiretroviral drugs from the 3 major drug classes: the data collection on adverse events of anti-HIV drugs (D:A:D) study. J Infect Dis 2010;201:318–30. 10.1086/649897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sabin CA, d'Arminio Monforte A, Friis-Moller N, et al. Changes over time in risk factors for cardiovascular disease and use of lipid-lowering drugs in HIV-infected individuals and impact on myocardial infarction. Clin Infect Dis 2008b;46:1101–10. 10.1086/528862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Obel N, Thomsen HF, Kronborg G, et al. Ischemic heart disease in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals: a population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:1625–31. 10.1086/518285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Holmberg SD, Moorman AC, Williamson JM, et al. Protease inhibitors and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with HIV-1. The Lancet 2002;360:1747–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11672-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rickerts V, Brodt H, Staszewski S, et al. Incidence of myocardial infarctions in HIV-infected patients between 1983 and 1998: the Frankfurt HIV-cohort study. Eur J Med Res 2000;5:329–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Carman WJ, Bowlin S, McAfee AT. Human immunodeficiency (HIV) therapy and cardiovascular (CV) events [ICPE Abstract 323]. In: Abstracts from the 27th International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20. [Google Scholar]

- 64. LaFleur J, Bress AP, Rosenblatt L, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes among HIV-infected veterans receiving atazanavir. AIDS 2017;31:2095–106. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rosenblatt L, Farr AM, Johnston SS, et al. Risk of cardiovascular events among patients initiating efavirenz-containing versus Efavirenz-Free antiretroviral regimens. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016a;3:ofw061 10.1093/ofid/ofw061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Rosenblatt L, Farr AM, Nkhoma ET, et al. Risk of cardiovascular events among patients with HIV treated with atazanavir-containing regimens: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2016b;16:492 10.1186/s12879-016-1827-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Desai M, Joyce V, Bendavid E, et al. Risk of cardiovascular events associated with current exposure to HIV antiretroviral therapies in a US veteran population. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:445–52. 10.1093/cid/civ316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Triant VA, Regan S, Lee H, et al. Association of immunologic and virologic factors with myocardial infarction rates in a US healthcare system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;55:615–9. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f4b752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Triant VA, Meigs JB, Grinspoon SK. Association of C-reactive protein and HIV infection with acute myocardial infarction. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;51:268–73. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a9992c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kwong GPS, Ghani AC, Rode RA, et al. Comparison of the risks of atherosclerotic events versus death from other causes associated with antiretroviral use. AIDS 2006;20:1941–50. 10.1097/01.aids.0000247115.81832.a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Klein DB, Leyden WA, Xu L, et al. Declining relative risk for myocardial infarction among HIV-positive compared with HIV-negative individuals with access to care. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:1278–80. 10.1093/cid/civ014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Silverberg MJ, Leyden WA, Xu L, et al. Immunodeficiency and risk of myocardial infarction among HIV-positive individuals with access to care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;65:160–6. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hansson GK, Inflammation HGK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1685–95. 10.1056/NEJMra043430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lo J, Plutzky J. The biology of atherosclerosis: general paradigms and distinct pathogenic mechanisms among HIV-infected patients. J Infect Dis 2012;205(Suppl_3):S368–S374. 10.1093/infdis/jis201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Cerrato E, Calcagno A, D'Ascenzo F, et al. Cardiovascular disease in HIV patients: from bench to bedside and backwards. Open Heart 2015;2:e000174 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, et al. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:2506–12. 10.1210/jc.2006-2190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Calza L, Manfredi R, Verucchi G. Myocardial infarction risk in HIV-infected patients: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical management. AIDS 2010;24:789–802. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328337afdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Martin A, Bloch M, Amin J, et al. Simplification of antiretroviral therapy with Tenofovir‐Emtricitabine or Abacavir‐Lamivudine: a randomized, 96‐Week trial. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:1591–601. 10.1086/644769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Alvarez A, Orden S, Andujar I, et al. Cardiovascular toxicity of abacavir: a clinical controversy in need of a pharmacological explanation. AIDS 2017;31:1781–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Llibre JM, Hill A. Abacavir and cardiovascular disease: a critical look at the data. Antiviral Res 2016;132:116–21. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Coplan PM, Nikas A, Japour A, et al. Incidence of myocardial infarction in randomized clinical trials of protease inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy: an analysis of four different protease inhibitors. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2003;19:449–55. 10.1089/088922203766774487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Crane HM, Heckbert SR, Drozd DR, et al. Lessons learned from the design and implementation of myocardial infarction adjudication tailored for HIV clinical cohorts. Am J Epidemiol 2014;179:996–1005. 10.1093/aje/kwu010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Althoff KN, McGinnis KA, Wyatt CM, et al. Comparison of risk and age at diagnosis of myocardial infarction, end-stage renal disease, and non-AIDS-defining cancer in HIV-infected versus uninfected adults. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:627–38. 10.1093/cid/ciu869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Althoff KN, Gange SJ. A critical epidemiological review of cardiovascular disease risk in HIV-infected adults: the importance of the HIV-uninfected comparison group, confounding, and competing risks. HIV Med 2013;14:191–2. 10.1111/hiv.12007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hedges LV, Vevea JL. Fixed- and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods 1998;3:486–504. 10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025874supp001.pdf (8.4MB, pdf)