Abstract

Objectives

The study aimed to compare candidate performance between traditional best-of-five single-best-answer (SBA) questions and very-short-answer (VSA) questions, in which candidates must generate their own answers of between one and five words. The primary objective was to determine if the mean positive cue rate for SBAs exceeded the null hypothesis guessing rate of 20%.

Design

This was a cross-sectional study undertaken in 2018.

Setting

20 medical schools in the UK.

Participants

1417 volunteer medical students preparing for their final undergraduate medicine examinations (total eligible population across all UK medical schools approximately 7500).

Interventions

Students completed a 50-question VSA test, followed immediately by the same test in SBA format, using a novel digital exam delivery platform which also facilitated rapid marking of VSAs.

Main outcome measures

The main outcome measure was the mean positive cue rate across SBAs: the percentage of students getting the SBA format of the question correct after getting the VSA format incorrect. Internal consistency, item discrimination and the pass rate using Cohen standard setting for VSAs and SBAs were also evaluated, and a cost analysis in terms of marking the VSA was performed.

Results

The study was completed by 1417 students. Mean student scores were 21 percentage points higher for SBAs. The mean positive cue rate was 42.7% (95% CI 36.8% to 48.6%), one-sample t-test against ≤20%: t=7.53, p<0.001. Internal consistency was higher for VSAs than SBAs and the median item discrimination equivalent. The estimated marking cost was £2655 ($3500), with 24.5 hours of clinician time required (1.25 s per student per question).

Conclusions

SBA questions can give a false impression of students’ competence. VSAs appear to have greater authenticity and can provide useful information regarding students’ cognitive errors, helping to improve learning as well as assessment. Electronic delivery and marking of VSAs is feasible and cost-effective.

Keywords: MEDICAL EDUCATION & TRAINING, Assessment, applied medical knowledge

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the largest and only multicentre study to date of the use of very-short-answer questions (VSAs) for the assessment of applied medical knowledge of medical students.

A robust marking process for VSAs was used involving multiple markers and independent checking.

Students volunteered to participate and the assessment was formative, so some responder bias is likely.

Students did not spend long on the single-best-answer format as they had just read the questions in VSA format; this was to avoid cueing in the VSA but may have biased positive cue rates upwards.

Introduction

For many years single-best-answer (SBA) questions have been the cornerstone of written assessments testing applied medical knowledge,1 2 including in high-stakes licensing assessments such as the US Medical Licensing Examination, the membership examinations of many UK Royal Colleges and graduation-level examinations of most UK medical schools. These questions consist of a clinical vignette, a lead-in question and (usually) five potential answers, one of which is the best answer (example in Box 1). Well-written SBAs can assess more than simple recall3 and have a number of advantages: they are easy to mark electronically making scoring quick and accurate, they produce internally consistent measures of ability, and they are acceptable to candidates because there is no intermarker variability.4 5 However, the provision of five possible answers means that a candidate may identify the correct answer by using cues provided in the option list or test-taking behaviours such as word association.2 6 Candidates may focus on practising exam technique rather than understanding the principles of the subject matter and honing their cognitive reasoning skills, thus adversely impacting learning behaviours.6 7

Box 1. Example of a question in very-short-answer (VSA) and single-best-answer (SBA) format.

A 60-year-old man has 2 days of a swollen, painful right leg. He has a history of hypertension and takes ramipril. He is otherwise well.

He has a swollen right leg. The remainder of the examination is normal.

Investigations:

Haemoglobin: 140 g/L (130–175).

White cell count: 8.0×109/L (3.8–10.0).

Platelets: 340×109/L (150–400).

Creatinine: 94 µmol/L (60–120).

Total calcium: 2.5 mmol/L (2.2–2.6).

Alanine aminotransferase: 30 IU/L (10–50).

Alkaline phosphatase: 99 IU/L (25–115).

Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT): 30 s (22–41).

Prothrombin time: 12 s (10–12).

Urinalysis: normal.

Chest X-ray: normal.

Venous duplex ultrasound scan: thrombus in superficial femoral vein.

VSA answers marked as correct (total number of students answering correctly: n=33, 2.3%).

Variants of CT chest/abdomen/pelvis were accepted.

Most common incorrect VSA answers (n, % of all students):

CT pulmonary angiogram (487, 34%).

D-dimer (386, 27%).

ECG (107, 7.6%).

Ankle brachial pressure index (58, 4.1%).

SBA answer options (n, % of all students choosing each):

CT of abdomen and pelvis (957, 68%).

Serum carcinoembryonic antigen (57, 4.0%).

Serum prostate-specific antigen (100, 7.1%).

Serum protein electrophoresis (143, 10%).

Ultrasonography of abdomen (157, 11%).

Because patients do not present with a list of five possible diagnoses, investigations or treatment options,8 SBA questions do not simulate the ‘situations they [the candidates] will face when they undertake patient-related clinical tasks’ (p66).9 Any alternative method of assessing applied medical knowledge must therefore provide increased content and response process validity, without resulting in significant reductions in other types of validity, reliability, acceptability, educational impact or an unacceptable increase in cost.10 Very-short-answer (VSA) questions are a potential solution.11 12 Like SBAs, VSAs have a clinical vignette followed by a lead-in question and can also be delivered electronically. Instead of having an answer list with the candidate being required to select one option, the candidate must provide their own answer. Questions are constructed so that the answer required is one to five words in length (example in Box 1). Preprogrammed correct and incorrect answers allow the VSA responses of most candidates to be marked automatically. Any responses not fitting the preprogrammed answers are then reviewed by a team of clinicians who determine which should be accepted as correct. The software stores the additional correct and incorrect responses, making each question much quicker and easier to mark if it is used in subsequent assessments.

Preliminary evidence suggests that VSAs have at least the same level of internal consistency as SBAs; they are practical, can be marked relatively quickly and may encourage positive changes in learning behaviours.11 12 An electronic VSA exam platform has been developed by the UK Medical Schools Council Assessment Alliance to complement their existing SBA platform, which is already widely used by medical schools throughout the UK. We used this VSA platform to undertake a large, multicentre, cross-sectional study to evaluate VSAs in comparison with SBAs. In particular, our objective was to determine if validity is compromised by the provision of five-answer options in SBAs by calculating the ‘positive cue’ rate for each question. A ‘positive cue’ occurs when a student gives an incorrect answer in the VSA format but correctly answers the question in SBA format.13 We also sought to determine if using VSAs had an impact on other aspects of assessment utility (reliability, potential educational impact and cost), as well as the ability of individual VSA and SBA questions to discriminate according to student performance on other questions.

Methods

Study population

All UK medical schools with graduation-level assessments (n=32) were invited to participate in this cross-sectional study. Assessment leads at schools agreeing to participate invited all of their final-year students to participate and organised the delivery of the assessment within a 10-week window between September and November 2018. Participation in the study by both schools and students was voluntary; students were provided with information about the study prior to taking part. Completion of both assessments was taken as evidence of informed consent.

Materials

We developed a 50-question formative assessment using the same questions in both VSA and SBA formats (online supplementary appendix 1). Participants were first given 2 hours to complete the VSA format and a further hour to complete the SBA format. Those entitled to extra time in summative assessments (eg, those with dyslexia) were given an additional 30/15 min (25%). The assessments were completed under examination conditions in computer rooms at each medical school.

bmjopen-2019-032550supp001.pdf (187.8KB, pdf)

Marking and feedback

SBAs were marked electronically using a predetermined answer key. VSA marking is semiautomated; the electronic platform checks the student’s response against a list of predetermined answers. Those responses that match this list are automatically marked as correct. Two clinicians (AS and RWe) reviewed all the remaining answers for each VSA and coded each response as correct (scoring 1 mark) or incorrect (0 mark; any blank responses were also scored 0). A third clinician (KM) was available to arbitrate any queries. A fourth clinician (RWi) subsequently reviewed all answers to check for any errors in marking. The time taken to mark each question was recorded.

Once all schools had completed the assessment, the SBA paper with answers and explanations was made available to all UK medical schools. Schools were informed of any questions in which <50% participating students answered the SBA question correctly for generic feedback but were not provided with individual student data. Students were able to review their individual performance in each assessment by logging into the exam platform.

Statistical analysis

The study administration team produced an Excel file containing answers and scores for each student for each question. Each student was allocated a numerical code and each school an alphabetical code before the data were sent to the research team to ensure anonymity. The data were transferred into Stata V.1514 for analysis.

For each participant/question combination, we identified whether providing answer options gave a positive cue. A positive cue occurred when a participant gave an incorrect answer to the VSA format of a question but the correct answer to the SBA.13 We calculated the positive cue rate (as a percentage) for each question as follows:

If all students answering the VSA incorrectly simply guessed at the SBA, the expected positive cue rate would be 20%. We therefore undertook a one-sided one-sample t-test against the null hypothesis that the rate would be ≤20%, using a critical p value of 0.025.

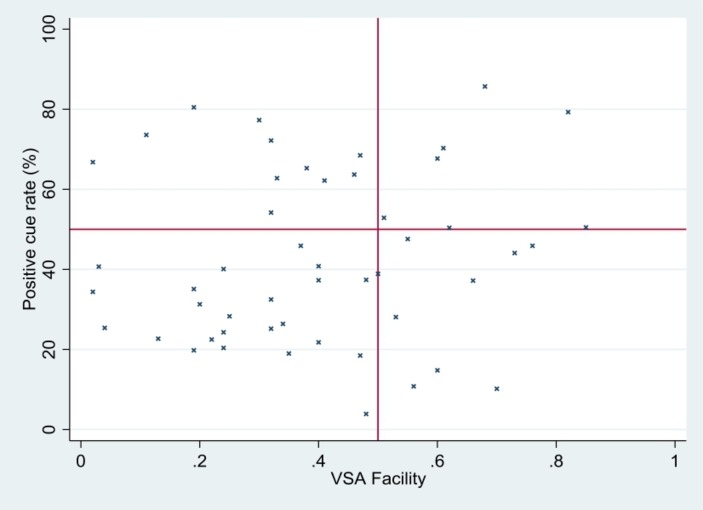

We also plotted the positive cue rate against VSA facility for each question to show how these statistics interact to enable identification of questions where poor knowledge (as assessed by the VSA) would be masked by the use of the equivalent SBA (questions with low VSA facility and a high positive cue rate).

Methods of analysis of additional outcomes are summarised in table 1. Where statistical significance testing was undertaken in these additional analyses, a critical p value of <0.01 was used.

Table 1.

Additional data analyses

| Component of assessment utility being evaluated | Method of analysis |

| Reliability: internal consistency | Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for each type of question compared using the method of Feldt17; the Spearman-Brown formula was then used to estimate the number of questions of each type required for an alpha of 0.8.18 |

| Cost: time taken to mark VSAs | The total minutes of consultant time required to mark the VSA, costed at the 2016/2017 hourly rate for a hospital consultant (including on-costs and overheads) of £10819 ($143). |

| Potential educational impact: effect on pass/fail rates | Cohen standard setting20 applied to both VSA and SBA total scores; pass/fail decisions for the two assessments were then compared using Cohen’s kappa. |

| Question discrimination | Pearson correlation coefficient (point-biserial) between students’ scores on each question and those on all other questions combined (item–rest correlation) for each type of question; the difference between question types was compared using a Wilcoxon signed-rank sum test (for paired, skewed data). |

SBA, single-best-answer; VSA, very-short-answer.

Sample size

A sample size calculation was undertaken in Stata V.15. Forty-seven questions would be required to detect a mean positive cue rate of ≥30% (SD 20%), in a one-sided one-sample t-test with alpha=0.02 and power=90%, against the null hypothesis value of ≤20%.

Patient and public involvement

There were no funds or time allocated for patient and public involvement so we were unable to involve patients.

Results

The study was completed by 1417 students from 20 UK medical schools (approximately 20% of all final-year students); data from all participants were included in the analysis, so there were no missing data (and we assumed any blank responses had been left intentionally blank and were scored 0). The range in student numbers between schools was 3–256 (median 45, IQR 21–103), which was due to differences in cohort size as well as differences in participation rates. Data on participant characteristics and reasons for non-participation of schools and individual students were not collected. The mean time spent on each format of the assessment for students without extra time was 82/120 min (SD 19 min) for the VSA and 24/60 min (SD 10 min) for the SBA, although students were reading the questions for the second time in SBA format. The mean score for the SBA items was 30.5/50 (SD 5.6) and that for the VSA items was 19.9 (SD 5.88).

Table 2 presents summary statistics comparing the SBA and VSA formats of the assessment (question-level data are shown in online supplementary appendix 2). The mean difference in question facility was 20 percentage points in favour of SBAs. The mean positive cue rate of 42.7% (95% CI 36.8% to 48.6%) was just over double the expected rate had all students answering the VSA format incorrectly taken a random guess at the SBA.

Table 2.

Comparison of SBA and VSA questions and scores

| SBA | VSA | SBA–VSA difference and statistical significance | |

| Question facility* Mean (SD), range |

0.61 (0.20), 0.16–0.95 |

0.40 (0.21), 0.02–0.85 |

0.21 (0.19), −0.32 to 0.65 Paired t-test, t=7.89, p<0.001 |

| Positive cue rate (question level) Mean (SD), range (%) |

42.7 (21.3), 3.9–85.7 |

One-sample t-test (Null hypothesis≤20%) t=7.53, p<0.001 | |

| Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) | 0.693 | 0.731 | −0.038 F 1416,1416=1.262, p<0.001 |

| Questions required for an alpha of 0.8 | 89 | 74 | 15 |

| Cohen pass mark† | 28/50 | 18/50 | N/A |

| Pass rate using Cohen pass mark (%) | 71.2 | 66.3 | Kappa=0.59 z=22.2, p<0.001 |

| Question discrimination Median (IQR), range |

0.184 (0.135–0.220), 0.003–0.287 |

0.192 (0.121–0.259), −0.006 to 0.395 |

−0.004 (−0.083 to 0.034), −0.296 to 0.225 Wilcoxon test, z=−1.36, p=0.175 |

*Facility: proportion of students answering correctly.

†Calculated as 60% of the score of the 95th percentile student and assuming scores due to guessing of 20% for the SBA and 0% for the VSA.

N/A, not applicable; SBA, single-best-answer; VSA, very-short-answer.

Figure 1 shows a scatter diagram of the positive cue rate against VSA facility. The diagram is split into four quadrants. The ‘concerning’ top-left quadrant identifies questions where poor knowledge as assessed by the VSA (facility <0.5 or 50%) is masked by the use of the SBA: a high positive cue rate (>50%) leads to SBA facilities at least 25 percentage points above the VSA facility. There were 11 items in this quadrant (22%), as summarised in table 3.

Figure 1.

Scatter diagram of VSA facility and the positive cue rate. Top-left: n=11 questions with low VSA facility (<0.5 or 50%) and a high positive cue rate (>50%). Top-right: n=7 questions with high VSA facility (>0.5) and a high positive cue rate (>50%). Bottom-left: n=24 questions with low VSA facility (<0.5) and a low positive cue rate (<50%). Bottom-right: n=8 questions with high VSA facility (>0.5) and a low positive cue rate (<50%). VSA, very-short-answer.

Table 3.

Question statistics and themes of questions with VSA facility <0.5 and positive cue rate >50%

| Question | SBA facility | VSA facility | Difference | Positive cue rate (%) | Theme |

| 9 | 0.84 | 0.19 | 0.65 | 80.5 | Investigations of diabetes insipidus |

| 41 | 0.82 | 0.30 | 0.52 | 77.3 | Diagnosis of cerebellar stroke |

| 3 | 0.76 | 0.11 | 0.65 | 73.6 | Assessment of patient following house fire |

| 25 | 0.80 | 0.32 | 0.48 | 72.2 | Treatment of delirium |

| 16 | 0.80 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 68.5 | Investigations of a neck lump |

| 4 | 0.68 | 0.02 | 0.65 | 66.8 | Further investigation of unprovoked DVT |

| 43 | 0.78 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 65.3 | Determining Glasgow Coma Scale score |

| 13 | 0.79 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 63.7 | Diagnosis of headache |

| 21 | 0.74 | 0.33 | 0.41 | 62.8 | Causative organism of malaria |

| 8 | 0.76 | 0.41 | 0.35 | 62.2 | Diagnosis of (o)esophageal rupture |

| 31 | 0.66 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 54.2 | Management of gout |

DVT, deep vein thrombosis; SBA, single-best-answer; VSA, very-short-answer.

Questions in the top-right quadrant of figure 1 (n=7/50, 14%) have a high positive cue rate (>50%), but the SBA format does not conceal a major cohort-level deficit in knowledge because the VSA facility was also fairly high (>0.5). Those in the bottom-left quadrant (n=24, 48%) have a low VSA facility (<0.5), but a lack of knowledge among the cohort is also revealed with the SBA format as the positive cue rate is low (<50%). Finally, questions in the bottom-right quadrant (n=8, 16%) have high VSA facility (>0.5) and a low positive cue rate (<50%).

The internal consistency of the VSA format of the assessment (Cronbach’s alpha 0.731) was higher than for the SBA format (0.693); this difference was statistically significant: F 1416,1416=1.262, p<0.001. The median question discrimination was 0.184 for SBAs and 0.192 for VSAs; this difference was not statistically significant (z=−1.36, p=0.175).

In terms of potential educational impact, the Kappa statistic of 0.59 (p<0.01) suggests ‘moderate’ agreement between pass/fail decisions on the two assessments using the Cohen method of standard setting, although with a much lower pass mark for the VSA paper. Despite a strong positive correlation between participants’ scores on the two formats (r=0.822, p<0.001), 161 students (11.4%) would have passed the SBA but failed the VSA, whereas 92 students (6.5%) would have passed the VSA but failed the SBA.

The two primary question markers worked together, each spending a total of 8 hours and 34 min marking the 50 VSAs. The median time per question per marker was 9.43 min, with an IQR of 5.00–13.09 and an overall range of 1.55–25.39, and the distribution was highly positively skewed. The third clinician on-hand to arbitrate spent a total of 30 min doing so. To mitigate marker bias, all markings were subsequently checked by a fourth marker, who spent a total of 6 hours and 57 min doing so. Assuming all markers were at consultant level, the total marking time cost for this 50-question paper for 1417 students was £2655 ($3500).

Discussion

Our findings highlight the advantages of using VSAs rather than SBAs to assess applied clinical knowledge in high-stakes summative medical exams. VSA scores are a better representation of students’ unprompted level of knowledge, with the average student scoring 21 percentage points lower on the VSA version of the assessment. If the questions used in our study are representative of undergraduate medical curricula and average question difficulty, then cues provided in SBAs could impact on the validity of around a quarter of the examination. These items are assessing the candidate’s ability to use cues or engage in test-taking behaviours such as using the answer options to make deductions about the correct answer rather than using clinical reasoning, arriving at the correct answer by eliminating wrong SBA answer options8 and/or ‘best-guessing’ from the answers available. We have shown that VSAs mitigate this risk by removing the option menu and compelling candidates to determine the correct answer themselves based on the clinical information provided, which is more akin to clinical practice. Linked to this, an added benefit of the VSA format is its ability to help identify deficits in students’ knowledge and/or cognitive reasoning. The themes of the questions with high positive cue rates and low VSA facility highlight areas of the curriculum where students lack understanding and where using the SBA format can therefore provide a false measure of students’ competence. Importantly, several VSA questions highlighted significant cognitive errors, which were not apparent in their SBA counterparts, or indeed even considered as possible student responses by the person authoring the question. The question in Box 1 is a good example (although it is an extreme example in terms of VSA facility): a venous thromboembolism has been confirmed, therefore rendering a D-dimer irrelevant, yet just over a quarter of students chose this option in the VSA. More concerning, just over one-third of students would have ordered a CT pulmonary angiogram in a patient with no respiratory symptoms or signs, thereby exposing the patient to a significant dose of unnecessary radiation without any likely therapeutic benefit. It is also possible that further investigation to exclude an occult malignancy would not have been instituted.

VSAs were non-inferior to SBAs on other indices of assessment utility. In terms of feasibility, the electronic delivery platform functioned well and participating medical schools did not report any problems associated with delivering the assessment. The platform also facilitated remote marking. VSAs are more time-consuming to mark than SBAs, but not prohibitively so. The marking time for an individual VSA (and therefore costs) will fall significantly with repeated use as pre-existing marking schemes are reapplied. Furthermore, as students gain experience in the type of answer required, it is possible there will be fewer incorrect answers to review, which would reduce marking time and costs further. VSAs also had slightly higher internal consistency (a measure of reliability) and comparable question discrimination, as seen in previous small-scale pilot studies.11

This study involved 20 medical schools across the UK, which were representative of all UK schools in terms of size and location. The large number of medical schools that took part in the study and the overall high number of participants make this the largest study comparing VSAs with SBAs, and suggest that the findings of this study are generalisable across the UK and potentially internationally. Non-completion of the assessments was rare: 1411 (99.6%) students completed all 50 SBA questions, and while more students left blank VSA responses, in terms of evidence of non-completion, only 11 (0.8%) did so for the last question and the maximum number of blank responses for any question (question 42) was 24 (1.7%). Previous studies have highlighted the benefits and shortcomings of SBA questions,2 4–7 13 but our work provides large-scale empirical data to test some of these claims using an alternative and feasible question format as the comparator.

Our study has several limitations. Medical schools agreed to participate, and then within each medical school a variable number of students volunteered to participate; therefore, some responder bias is likely. Data on participant characteristics were not collected, so while we are unable to comment on how representative our sample is in relation to the total final-year population of UK medical students, the high number of medical schools and students participating increases the likelihood that our study population is representative. This assessment was formative and was sat at variable timeframes ahead of students’ medical school summative assessments (depending on the individual dates for summative assessments, which varied for each participating medical school). Students are therefore likely to have prepared and participated in a different way than for a summative assessment, especially as for some schools, final exams were several months after the study date. Students all sat the SBA questions after the VSA questions to ensure there was no cueing in the VSA. This means that positive cue rates may have been biased upwards because participants had a second look at the questions during the SBA paper, which may have contributed to them arriving at the correct answer along with having the answer options. We did not focus on the negative cue rate (where students answered the VSA correctly and then the SBA incorrectly) in this study. The mean negative cue rate was 3.9%, lower than the 6.1% in a previous study,13 although our mean was skewed upwards by five questions with negative cue rates in excess of 10% (the median negative cue rate was 2.0%). The negative cue rate was highest on question 27, which asked students to identify the most appropriate test for monitoring respiratory function based on a scenario that described a patient in myasthenic crisis. Forty-eight per cent of students answered correctly in the VSA (choosing forced vital capacity), but 34% of these students then answered the SBA incorrectly, with most being negatively cued by the answer option arterial blood gas.

We have not yet undertaken a criterion-based approach to standard setting using expert judgement, so we were unable to determine whether the full cueing effect of SBAs is accounted for in common standard setting processes such as Angoff15 or Ebel.16 Furthermore, this study was also not designed to evaluate all components of assessment utility including acceptability to stakeholders. Previous smaller-scale pilots of VSAs reported that students found VSAs more challenging, but appreciated the additional validity they offered.11 12

Key extensions to this work should include the study of how SBA and VSA questions are standard set relative to performance and a comparison of the predictive validity of SBA and VSA scores, particularly using measures of performance in clinical settings.

Conclusion

VSAs appear to provide a more accurate measure of a candidate’s knowledge than SBAs. They also offer greater insight into cognitive errors, thereby offering opportunities to hone teaching, feedback and learning, as well as creating summative assessments with greater validity. Unlike short-answer questions, modified essay formats or clinical reasoning problems,9 VSAs are straightforward to deliver in an electronic format and efficient to mark. We need to know that medical students and trainees have the required applied medical knowledge to practise safely without test scores being confounded by the ability to use the cues of SBA answer options. Our results suggest that VSAs could provide a more authentic method of assessing medical knowledge while maintaining most of the cost-efficiency of SBAs.

Dissemination

The results of this study have been reported to the participating medical schools. Participating medical students have received feedback on their performance in the assessment. They will have access to the study results on publication of this article.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Medical Schools Council Assessment Alliance (MSCAA) management and administration team who supported this study. The MSCAA Board provided support and helpful comments on the study protocol and study design but had no role in data analysis, interpretation and did not input into the writing of this paper, although they did see the draft prior to submission. The MSCAA supported this study through the provision of staff time and travel costs, but no financial payments were made. MSCAA staff assisted with data collection. This study required the support of assessment leads at participating schools, invigilators and students, who all volunteered their time.

Footnotes

Contributors: The study was designed and implemented by AS, RWe, CB and MG. AS and RWe wrote the question paper. AS, RWe and KM undertook the initial marking, which was verified by RWi. CB undertook the data analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper, supported by RWe for the literature review. AS, RWe, MG, KM and RWi provided critical comments on the paper during each round of drafting.

Funding: MG is supported by the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre. CB is supported by the NIHR CLAHRC West Midlands initiative. This paper presents independent research and the views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: CB, AS, MG and RWe are elected members of the MSCAA Board. MG and AS are advisors for the GMC UK Medical Licensing Assessment.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Imperial College of Medicine Medical Education Ethics Committee (reference MEEC1718-100).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: The individual item-level data for each student participant are not available.

References

- 1. Coderre SP, Harasym P, Mandin H, et al. The impact of two multiple-choice question formats on the problem-solving strategies used by novices and experts. BMC Med Educ 2004;4:23 10.1186/1472-6920-4-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heist BS, Gonzalo JD, Durning S, et al. Exploring clinical reasoning strategies and test-taking behaviors during clinical vignette style multiple-choice examinations: a mixed methods study. J Grad Med Educ 2014;6:709–14. 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00176.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bibler Zaidi NL, Grob KL, Monrad SM, et al. Pushing critical thinking skills with multiple-choice questions: does bloom’s taxonomy work? Acad Med 2018;93:856–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wass V, Van der Vleuten C, Shatzer J, et al. Assessment of clinical competence. The Lancet 2001;357:945–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04221-5 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04221-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pugh D, De Champlain A, Touchie C, et al. Plus ça change, plus c’est pareil: making a continued case for the use of MCQs in medical education. Med Teach 2019;41:569–77. 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1505035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Raduta C. Consequences the extensive use of multiple-choice questions might have on student's reasoning structure. Rom Journ Phys 2013;58:1363–80. [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCoubrie P. Improving the Fairness of multiple-choice questions: a literature review. Med Teach 2004;26:709–12. 10.1080/01421590400013495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Surry LT, Torre D, Durning SJ. Exploring examinee behaviours as validity evidence for multiple-choice question examinations. Med Educ 2017;51:1075–85. 10.1111/medu.13367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. ten Cate O, Durning SJ. Approaches to assessing the clinical reasoning of preclinical students : ten Cate O, Custers E, Durning S, Principles and practice of case-based clinical reasoning education. Cham: Springer, 2018: 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Van Der Vleuten CPM. The assessment of professional competence: developments, research and practical implications. Adv Health Sci Educ 1996;1:41–67. 10.1007/BF00596229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sam AH, Field SM, Collares CF, et al. Very-short-answer questions: reliability, discrimination and acceptability. Med Educ 2018;52:447–55. 10.1111/medu.13504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sam AH, Hameed S, Harris J, et al. Validity of very short answer versus single best answer questions for undergraduate assessment. BMC Med Educ 2016;16:266 10.1186/s12909-016-0793-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schuwirth LWT, Vleuten CPM, Donkers HHLM. A closer look at cueing effects in multiple-choice questions. Med Educ 1996;30:44–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1996.tb00716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. StataCorp Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 College Station, Texas: LP S; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Angoff W. Scales, norms and equivalent scores : Thorndike R, Educational Measurement. Washington, DC: American Council on Education, 1971: 508–600. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ebel RL. Procedures for the analysis of classroom tests. Educ Psychol Meas 1954;14:352–64. 10.1177/001316445401400215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feldt LS. A test of the hypothesis that Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient is the same for two tests administered to the same sample. Psychometrika 1980;45:99–105. 10.1007/BF02293600 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holsgrove G. Reliability issues in the assessment of small cohorts. London: General Medical Council, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Curtis L, Burns A. Unit costs of health and social care 2018. Canterbury: Kent Uo, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cohen-Schotanus J, van der Vleuten CPM. A standard setting method with the best performing students as point of reference: practical and affordable. Med Teach 2010;32:154–60. 10.3109/01421590903196979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-032550supp001.pdf (187.8KB, pdf)